Abstract

Skeletal muscles, which constitute 40–50% of body mass, regulate whole-body energy expenditure and glucose and lipid metabolism. Peroxisomes are dynamic organelles that play a crucial role in lipid metabolism and clearance of reactive oxygen species, however their role in skeletal muscle remains poorly understood. To clarify this issue, we generated a muscle-specific transgenic mouse line with peroxisome import deficiency through the deletion of peroxisomal biogenesis factor 5 (Pex5). Here, we show that Pex5 inhibition results in impaired lipid metabolism, reduced muscle force and exercise performance. Moreover, mitochondrial structure, content, and function are also altered, accelerating the onset of age-related structural defects, neuromuscular junction degeneration, and muscle atrophy. Consistent with these observations, we observe a decline in peroxisomal content in the muscles of control mice undergoing natural aging. Altogether, our findings show the importance of preserving peroxisomal function and their interplay with mitochondria to maintain muscle health during aging.

Subject terms: Mechanisms of disease, Peroxisomes

The role of peroxisomes in skeletal muscle remains largely unexplored. Here, the authors show that peroxisomal dysfunction and disrupted crosstalk with mitochondria drive age-related muscle decline, underscoring the need to preserve peroxisomes for muscle health.

Introduction

Skeletal muscle, the body’s largest tissue, plays a critical role in maintaining systemic metabolic balance through intricate interorgan communication. As a central hub for metabolic activities, it governs glucose and lipid balance and serves as the primary protein reservoir, supplying essential amino acids to fuel energy production in other organs during catabolic states. As such, precise adjustments in muscle mass and metabolic demands become indispensable for meeting overall metabolic needs and ensuring whole-body homeostasis1. However, excessive catabolism during illness can exceed muscle plasticity, resulting in atrophy, and depleted metabolic reserves, leading to harmful functional limitations that impact disease onset and progression1.

Muscle atrophy and weakness represent significant clinical challenges observed in conditions such as cancer, diabetes, obesity, and cardiac failure, as well as unhealthy aging and infections like COVID-19. Muscle loss serves as a negative prognostic factor, causing respiratory insufficiency, loss of independence, and metabolic disruptions, thereby compromising life quality and elevating morbidity and mortality rates1,2. On the other hand, maintaining a healthy skeletal muscle mass is associated with a reduced risk of mortality3,4, underscoring the critical role of muscle health in overall body homeostasis.

Our understanding of pathways regulating muscle mass has greatly improved in the last years. However, the lack of effective therapeutic approaches for muscle wasting highlights our limited comprehension of the mechanistic insights involved in muscle atrophy. Molecular dissection of these mechanisms is crucial for paving the way toward successful drug development and intervention strategies.

Peroxisomes are ubiquitous dynamic metabolic organelles, adjusting their number and protein content to cellular metabolic needs. In mammals, they harbor over 50 anabolic and catabolic matrix enzymes involved in essential metabolic pathways, such as fatty acid oxidation, biosynthesis of plasmalogen and bile acids, and reactive oxygen species detoxification (ROS)5. As non-autonomous organelles, peroxisomes closely interact with other organelles5, particularly mitochondria, through physical and functional connections like membrane contact sites (MCS), mitochondrial-derived vesicles, and biological messengers like ROS or lipids5–8. Thus, in light of the close interaction between the two organelles, it is not surprising that the functional impairment of either organelle is likely to induce dysfunction to the other9. Despite the clear interplay between peroxisomes and mitochondria, their specific contributions to pathology are not fully understood7. While the impact of mitochondrial metabolic activity on muscle function has been extensively explored10, peroxisomes in skeletal muscle have been poorly investigated. The regulation of peroxisomes and their potential contribution to muscle function remain unknown, representing a critical gap in our understanding, particularly considering the significant metabolic role of these organelles.

Peroxisome biogenesis relies on the coordinated activity of several peroxins (Pex) proteins to assemble and maintain functional peroxisomes. Mutations in at least 14 different Pex genes result in rare autosomal recessive Peroxisomal Biogenesis Disorders (PBD), also known as Zellweger Spectrum Disorders11. The inability to form functional peroxisomes in PBD leads to the loss of essential peroxisomal metabolic functions and subsequent multisystem tissue pathology. PBD are a heterogeneous group of disorders ranging from severe to relatively milder phenotypes, with severity inversely related to age of onset. The most severe presentation is lethal within the first year of life, characterized by craniofacial dysmorphism, neuronal dysfunction, hepatorenal failure, and profound muscular hypotonia11.

Biochemically, PBD are characterized by the accumulation of very-long-chain (VLCFA) and branched-chain fatty acids, bile acid intermediates, pipecolic acid, and severe depletion of plasmalogens and docosahexaenoic acid11.

In line with the intense metabolic activity of skeletal muscle, peroxisome absence or dysfunction severely impacts muscle tissue in PBD patients. Muscle biopsies from individuals with mutations in Pex12 and Pex16 reveal a secondary mitochondrial myopathy characterized by enlarged mitochondria, reduced mitochondrial respiratory chain activity, lipid accumulation, and muscle atrophy. These pathological features likely contribute to clinical manifestations such as generalized hypotonia, respiratory issues, and sucking difficulties12,13. Pex5, an essential receptor protein crucial for importing most peroxisomal enzymes into the peroxisomal lumen, holds particular significance. In humans, mutations in the Pex5 gene result in PBD11, and the total deletion of Pex5 in mice recapitulates PBD, resulting in early postnatal mortality14. Importantly, in these mice, the diaphragm is the most severely affected muscle, exhibiting several mitochondrial abnormalities, including disrupted mitochondrial ultrastructure and altered expression and activities of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes15. This observation suggests that respiratory failure may, at least in part, contribute to the mortality observed in some patients15. Similarly, liver-specific and pancreatic cells-specific deletion of Pex5 results in both structural and functional mitochondrial defects16,17, closely resembling the mitochondrial abnormalities reported in PBD patients13,18,19. In these Pex5 deletion models, the defects include twisted or irregular cristae, a dense matrix, and crystalline inclusions. Moreover, these structural changes are accompanied by reduced mitochondrial DNA content, decreased activities of the respiratory chain complexes, and increased oxidative stress16,17. Importantly, mitochondrial dysfunction is not limited to PBD but is also observed in patients with defects in peroxisomal fatty acid metabolism (e.g., X-ALD)20.

Additionally, peroxisomal dysfunction is associated with aging, and age-related diseases such as diabetes, obesity, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders21,22. Notably, these conditions share muscle atrophy and dysregulated muscle function as common features. However, the role of peroxisomes in muscle function remains largely unexplored, and the physiological significance of peroxisomal-mitochondrial cooperation in muscle health and disease remains unclear.

In this study, we show that muscle-specific deletion of the peroxisomal biogenesis factor Pex5 in mice triggers early changes in lipid and amino acid metabolism resulting in a detrimental effect on muscle force and exercise performance. These disruptions progressively contribute to a decline in mitochondrial structure, content and function, together with sarcomere and neuromuscular junction degeneration, accumulation of aggregates, which altogether lead to muscle atrophy and induce the premature onset of muscle aging. Consistent with these findings, we also observed a decline in peroxisomal content in the muscles of control mice undergoing natural aging.

Results

Muscle-specific ablation of Pex5 results in the impairment of peroxisome assembly, protein import, and pexophagy flux

The physiological role of peroxisomes in skeletal muscle remains significantly underexplored. To investigate their relevance in maintaining skeletal muscle metabolism and mass, we generated a mouse model to induce peroxisomal dysfunction specifically within the muscle tissue. We crossed Pex5 floxed mice23 with a transgenic line expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Myosin Light Chain 1 fast (MLC1f) promoter24, thereby generating mice lacking Pex5 in skeletal muscle from birth (MLC1f-Pex5−/−). The deletion of Pex5 in muscle tissue was validated through Real-Time PCR (Fig. 1A) and western blot analyses (Fig. 1B) in tibialis anterior (TA), demonstrating a significant reduction in both Pex5 transcript and protein levels. Muscle-specific Pex5−/− knockout animals (hereafter referred to as KO) were born at the expected Mendelian ratio and exhibited full viability, fertility, and physical appearance indistinguishable from their Pex5fl/fl littermates (hereafter referred to as “Control”). Accordingly, the postnatal changes in body weight gain, and the lean and fat mass body composition were similar in both control and KO groups (Supplementary Fig. 1A–C).

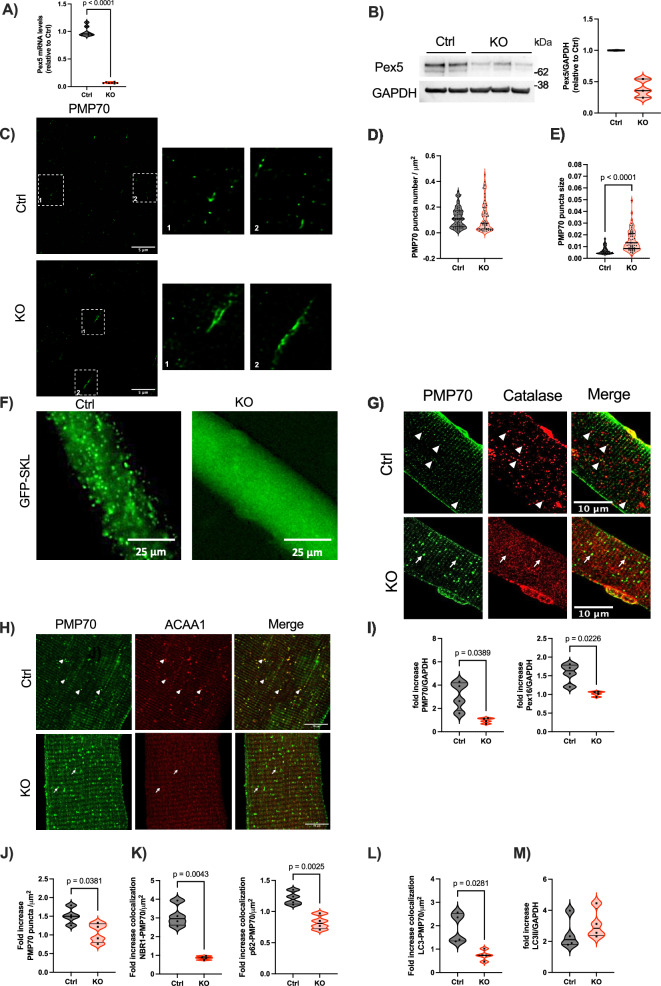

Fig. 1. Impaired peroxisome assembly, protein import and pexophagy flux in Pex5 KO skeletal muscle.

Pex5 mRNA (A) and protein levels (B) in tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of KO mice. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3 phosphatedehydrogenase. Each dot represents a single muscle (A: n = 7 Ctrl/KO; B: Ctrl n = 2; KO n = 3). C Representative STED images of longitudinal TA fibers showing endogenous peroxisomes, immunostained with anti-PMP70, from 3mo control and KO mice. The square corresponds to the magnification shown on the right. Quantification of PMP70-positive puncta number normalized to fiber area (D), and size (E). Each dot represents a single TA fiber analyzed (Ctrl n = 70; KO n = 57). F Representative images of GFP-SKL transfection into FDB fibers. Left: GFP-positive puncta in control fibers; right: GFP cytosolic distribution in KO fibers. G Representative images of PMP70 and catalase immunostaining in isolated FDB fibers. Arrowheads indicate PMP70-positive structures containing catalase in control fibers; arrows show PMP70-positive structures in KO muscle without catalase signaling. H Representative images showing PMP70 and ACAA1 immunostaining in FDB fibers. Arrowheads indicate PMP70-positive structures containing ACAA1 in control fibers; arrows show PMP70-positive structures with reduced ACAA1 in KO fibers. I Fold increase, expressed as the ratio between colchicine-treated and untreated samples, of PMP70 and Pex16 protein levels normalized to GAPDH. J Fold increase of PMP70-positive puncta following colchicine treatment. K Fold increase of PMP70-positive puncta colocalizing with NBR1 or p62 after colchicine treatment. L Fold increase of PMP70-positive puncta colocalizing with LC3 following colchicine treatment. J–L All data were normalized to muscle fiber area. M Fold increase of LC3 II protein levels normalized to GAPDH after colchicine treatment. I–M Each dot represents a single TA muscle (n = 4 Ctrl/KO; values calculated as the ratio of colchicine-treated to untreated samples from the same genotype). All data were obtained from the analysis of 3-month-old mice muscles. Data shown as violin plots (with individual data points). Data were analyzed with unpaired two-sided Welch’s t tests (A, D, E, I–M). Source data are provided as a source data file.

To visualize muscle peroxisomes, we performed an immunostaining against the peroxisomal membrane protein PMP70 (ABCD3), a well-established marker of peroxisomes, in longitudinal sections of TA fibers at 3 months of age (Fig. 1C). Because the peroxisomal size is near the diffraction limit, we used super-resolution STED microscopy, as its enhanced spatial resolution enables more precise morphological and quantitative assessments. Interestingly, we observed a slight increase in the number of PMP70-positive puncta in KO fibers compared to controls, although this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1D). Additionally, the overall quantification of the peroxisomal size indicated a significant increase in KO fibers, however not all peroxisomes in KO muscle exhibited enlarged dimensions revealing heterogeneity in peroxisomal size (Fig. 1E). SKL is the peroxisomal targeting signal 1 (PTS1) recognized by Pex5 to import the peroxisomal proteins from the cytosol to the peroxisomal matrix. To investigate the protein import capacity of PMP70-positive structures in the KO muscle, we conducted in vivo transfection of flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) fibers in 3-month-old mice with a sfGFP-Peroxisomes-2 plasmid encoding a GFP-SKL fusion protein, in which the SKL peroxisomal targeting sequence is fused to the C-terminus of GFP. The control fibers displayed a punctate distribution, while KO fibers exhibited a cytosolic distribution (Fig. 1F), reflecting an impairment in the peroxisomal protein matrix import. The import defect was further supported by the colocalization of PMP70 with catalase in control fibers, whereas KO fibers displayed cytosolic staining of catalase, highlighting the impairment in peroxisomal protein import (Fig. 1G). To further explore peroxisomal protein import in skeletal muscle, we used the PeroxoTag-IP method which enables the isolation of intact and functional peroxisomes through the expression of a tagged peroxisomal membrane protein25. We injected the gastrocnemius muscles of 3-month-old control and KO mice with adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) to deliver the PeroxoTag vector. PeroxoTag expression was driven by the human skeletal actin (HSA) promoter to restrict its tropism to mature muscle fibers; moreover, this construct encodes three HA epitopes fused to the N-terminus of monomeric EGFP, along with a C-terminal fragment of PEX26, which ensures correct targeting and integration into the peroxisomal membrane of myofiber-specific peroxisomes. Notably, this genetic approach has previously been shown not to alter the peroxisomal interactome in other cellular models25. Four weeks post-infection, peroxisomes were immunopurified from fresh skeletal muscle homogenates using anti-HA magnetic beads. Immunoblot analysis of the fractions confirmed enrichment of the peroxisomal membrane protein PMP70, with minimal contamination from cytosolic (GAPDH) and lysosomal (Cathepsin B, CTSB) markers. Moreover, Tom20 detection suggests that the workflow may also recover mitochondrial proteins interacting with peroxisomes (Supplementary Fig. 1D). To evaluate peroxisomal matrix protein import, we examined the localization and processing of three key peroxisomal enzymes: catalase, acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1 (ACAA1), and D-specific multifunctional protein 2 (MFP2), all of which are synthesized in the cytosol and must be imported into the peroxisomal matrix to perform their respective functions. ACAA1 and MFP2 are central to the β-oxidation of very-long-chain fatty acids and require processing within the peroxisome to become functionally active. Catalase was readily detected in immunopurified peroxisomes from control muscle but was nearly undetectable in KO samples. Similarly, ACAA1 processing was impaired in KO peroxisomes, with the mature 41 kDa form absent. The 45 kDa processed form of MFP2, which migrates at approximately 43 kDa on the polyacrylamide gel, was also undetectable in KO peroxisomes (Supplementary Fig. 1E). These findings strongly support a defect in peroxisomal matrix protein import in our muscle-specific Pex5 KO model. Due to potential variability in immunoprecipitation efficiency and the use of fixed sample volumes, these findings are qualitative. While catalase accumulation was clearly observed in whole-muscle lysates from KO animals, differences in ACAA1 and MFP2 processing were more difficult to detect under these conditions. To overcome this limitation, we performed Western blot analysis using equal amounts of total protein from whole-muscle lysates, which confirmed impaired processing of MFP2 in KO muscle (Supplementary Fig. 1F). In addition, immunohistochemistry revealed reduced co-localization of ACAA1 with PMP70 in KO muscle fibers, further supporting a defect in matrix protein import (Fig. 1H). Collectively, these observations confirm that the residual PMP70-positive peroxisomal structures in KO muscle are import deficient. As a result, PMP70-positive structures in KO fibers resemble peroxisomal ghosts, import-deficient residual peroxisomal membranes resulting from aberrant peroxisome assembly, with little or no matrix content. Importantly, such structures are well-documented hallmarks of PBD patients with Pex5 mutations26,27 as well as a distinctive feature of the total Pex5 KO animal model14.

Pex5 has been reported as a target for ubiquitination that promotes in mammals, the selective autophagic degradation of peroxisomes, known as pexophagy28–30. To further investigate the dynamics of PMP70-positive structures, we examined peroxisome turnover through pexophagy, conducting in vivo experiments by administering either vehicle or colchicine to 3-month-old mice. Colchicine blocks the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, thereby inhibiting autophagic flux and allowing the assessment of the protein levels of interest in the absence of degradation. We first performed Western blot analysis of TA muscle samples to assess the levels of the peroxisomal membrane proteins PMP70 and Pex16. To evaluate pexophagy flux, we quantified the fold increase in the abundance of these proteins following autophagy inhibition, calculated as the ratio of colchicine-treated samples to untreated samples. Notably, whereas control muscles showed a clear accumulation of PMP70 and Pex16 upon colchicine treatment, reflecting active degradation, KO muscles displayed a markedly reduced fold increase, suggesting diminished turnover of both proteins and, consequently, a reduced pexophagy flux (Fig. 1I and Supplementary Fig. 2A). Under basal conditions, KO muscle displayed only a modest, non-significant increase in peroxisome number (Fig. 1D); however, basal measurements provide only a static snapshot, highlighting the need for inhibitors to capture dynamic autophagic flux. To address this, we performed immunostaining for PMP70 in TA muscle sections from mice treated with either vehicle or colchicine to quantify changes in peroxisome number. Consistent with the results from western blot analysis (Fig. 1I and Supplementary Fig. 2A), the fold increase in peroxisome number following colchicine treatment was significantly lower in KO muscles (Fig. 1J). In the same samples, we then conducted double immunostaining for PMP70 together with either NBR1 or p62, two ubiquitin-binding autophagic receptors implicated in peroxisomal clearance31,32, to quantify the number of PMP70-positive peroxisome structures colocalizing with these autophagy receptors. Notably, colchicine treatment in control muscle led to greater peroxisome colocalization with NBR1 than with p62, suggesting preferential recruitment of NBR1 (Fig. 1K and Supplementary Fig. 2B–E). In contrast, in KO muscle, peroxisome association with NBR1, but not p62, was already significantly elevated under basal conditions, and colchicine treatment did not further affect PMP70 colocalization with either receptor (Supplementary Fig. 2B–E). Accordingly, the fold increase in peroxisomes colocalizing with both receptors was significantly reduced, with the reduction being more pronounced for NBR1 than for p62 (Fig. 1K).

Furthermore, we assessed the fold increase in structures positive for both PMP70 and LC3 using immunostaining, revealing a significant reduction in KO muscle (Fig. 1L and Supplementary Fig. 2F). Altogether, these findings indicate a clear impairment in pexophagy flux in the absence of Pex5. Finally, we quantified LC3 II by Western blot analysis to assess general autophagy (Fig. 1M and Supplementary Fig. 2A). Importantly, Pex5 deletion results in reduced peroxisome turnover without affecting the general autophagy flux, in line with previous observations28. Altogether, our data emphasize the muscle-specific Pex5 KO mouse as a suitable model for unraveling the consequences of peroxisomal dysfunction in skeletal muscle.

Pex5 deletion in skeletal muscle induces early alterations in lipid metabolism

Peroxisomes perform crucial roles in lipid metabolism, including fatty acid oxidation of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) and ether lipids biosynthesis such as plasmalogens. To gain deeper insights into peroxisomal function, we performed untargeted lipidomics on gastrocnemius muscle (GNM) from control and KO mice at an early (3 months) and late time points (18 months) (Supplementary Data 1, 2). This approach allowed us to track the dynamic changes in lipid metabolism over time. We identified more than 2000 lipids covering multiple lipid classes. Muscle tissue from Pex5-deleted mice exhibited significant alterations in their lipid profiles at both 3 and 18-month-old, as shown by principal component analysis (PCA) (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Consistent with the disruption of peroxisomal lipid metabolism, KO muscles showed a reduction in ether lipids and increased levels of VLCFA containing lipid species at all ages (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 3B). Specifically, the total levels of plasmalogen species, phosphatidylcholine (PC[P]) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE[P]), as well ether-linked phosphatidylcholine (PC[O]) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE[O]), were already diminished in KO muscle tissue at the 3-month time point (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. 3C). Furthermore, we observed increased levels of phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and triglycerides (TG) containing VLCFA with a tendency toward longer unsaturated fatty acid (FA) chains (Fig. 2C). More specifically, PC and PE species exhibited a shift towards longer acyl chain lengths, while species with acyl chains shorter than C40 were reduced (indicated by a dashed line in Fig. 2C). However, the total levels of PC, PE, diacylglycerol (DG), and TG remained unaltered in KO muscle compared to control muscle across all age groups, with exceptions noted for PE, cholesteryl ester (CE), and sphingomyelin (SM), which exhibited increases at 18 months (Supplementary Fig. 3D). Quantitative targeted lipidomic analyses on 9-month-old muscle confirmed no change in total phospholipids, DG and TG between genotypes also at this age (Supplementary Fig. 3E). While total ceramide levels (Cer d) showed no significant differences between control and KO at both timepoints (Supplementary Fig. 3D), specific species within the ceramide lipid class, such as Cer d31:0, Cer d41.0, Cer d43.2, exhibited significant increases in muscles from 18 months KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 3F). Additionally, Cer d38.1 was consistently induced in both KO muscles at 3 and 18 months (Supplementary Fig. 3F).

Fig. 2. Alterations in Pex5-null muscle lipidomic profile.

A Volcano plot based on untargeted lipidomics analysis performed in 3mo gastrocnemius muscles comparing Ctrl vs. KO. Significantly increased lipids (p < 0.01) are shown in red and significantly decreased lipids in blue. Labels were added automatically for lipids exceeding the significance threshold (p < 0.01), based on spatial constraints to avoid overlap. B Skeletal muscle concentration of total phosphatidylcholine (PC[P]), and phosphatidyletanolamine (PE[P]) plasmalogen species is reduced in KO muscle. Each dot represents a single muscle (3mo: Ctrl n = 4; KO n = 7). C Phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and triglycerides (TG) with longer unsaturated acyl chains increase in 3mo KO muscle. Heatmaps show log₂ fold changes (logFC) for PC, PE, and TG species, plotted by total acyl chain length (sum of all fatty acyl chains, y-axis) and total unsaturation (x-axis). Color indicates logFC, red: increases, blue: decreases. The dashed line indicates C40 acyl chains. D Total cardiolipin (CL) muscle concentration in skeletal muscle at 3 and 18mo. Each dot represents a single muscle (3mo: Ctrl n = 4; KO n = 7; 18mo: n = 7 Ctrl/KO). E CL chain length over C72 and unsaturation increases in KO muscle at both ages. Dashed line indicates C72. All lipidomics data were normalized to dry tissue weight. 3mo and 18mo refer to samples from 3- and 18-month-old mice. Data shown as violin plots (with individual data points). Unpaired two-sided Welch t test was used in (A, B, and D). Source data are provided as a source data file.

Fig. 3. Pex5 ablation in skeletal muscle results in progressive mitochondrial content decline.

A, B Transcriptomic RNA-seq Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis (GOEA) showing downregulation of metabolic pathways-related genes. A Biological processes (BP) significantly inhibited at 9 months. Enrichment Score of each BP term is plotted. B BP significantly inhibited at 18mo. Enrichment Score of each BP term is plotted. C Heatmap of 25 mitochondria-related genes inhibited in KO vs CTRL at 9mo. Heatmap showing the expression of these transcripts at 3, 9 and 18mo. DEGs: Differentially Expressed Genes. Mitochondrial DNA copy number (D) and citrate synthase activity quantification (E) in TA muscle at 3,9, and 18mo. D Each dot represents a single muscle analyzed (3mo: Ctrl n = 4; KO n = 7; 9mo and 18mo: n = 7 Ctrl/KO). Data are normalized to controls. E Each dot represents a single muscle analyzed (3mo: n = 4 Ctrl/KO; 9mo: n = 6 Ctrl/KO; 18mo: n = 7 Ctrl/KO). Data are normalized to controls. F Mitochondrial number quantified from muscle fibers obtained from 4 muscles per genotype at 3, 9, and 18mo. Each dot in the graph represents the quantification from a single muscle fiber (n = 30 per group for all ages). G Mitophagy flux analyzed by electroporation of mt-mKEIMA into flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles of 9mo Ctrl and KO mice. Changes in the fluorescent spectra were used to calculate the mitophagy/area index, normalized to the myofiber area. Each dot represents a single FDB fiber isolated from 4 mice for each genotype (9mo: Ctrl n = 41; KO n = 49). H Densitometric quantification of PGC1α/β by WB, normalized to GAPDH, in muscles at 9 and 18 months. Each dot represents a single muscle analyzed (9mo and 18mo: n = 7 Ctrl/KO). Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as violin plots (with individual data points). 3mo, 9mo and 18mo refer to samples from 3-, 9-, and 18-month-old mice. Unpaired two-sided Welch’s t tests (D, E (lower panel), F, and H) and Mann–Whitney test (upper and middle panels of E and G) were used for experiments comparing two groups. Source data are provided as a source data file.

Cardiolipin (CL) is a phospholipid synthesized in the inner mitochondrial membrane, crucial for maintaining proper cristae folding, respiratory chain integrity, and ATP synthase function33. We observed a significant reduction of total levels of cardiolipin (CL) at 3-month old. By 18 months, cardiolipin level remains stable in KO muscle, whereas it declines in control muscle, resulting in no significant difference at 18-month old (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the composition of CL species was altered across all age groups, showing a tendency toward very long unsaturated fatty acid (FA) chains, while acyl chains below C72 were reduced (indicated by a dashed line in Fig. 2E). This shift is consistent with the VLCFA accumulation resulting from peroxisomal dysfunction. A similar shift toward longer acyl chains, leading to an overall increase in the summed fatty acid chain length of lipids, was observed in the lipidomic profile of fibroblasts from PBD patients34.

Mitochondrial content undergoes age-dependent downregulation in Pex5-deficient muscle

To investigate the network of genes controlled by Pex5, we used an unbiased approach, performing bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on the gastrocnemius muscle of 3-, 9- and 18-month-old KO mice and their age-matched control littermates.

Despite substantial alterations in the lipidomic profile of KO muscle already at 3 months (Supplementary Fig. 3A), the most significant metabolic changes emerged in the muscle transcriptome at 9 and 18 months. We performed both Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis (GOEA) within the “biological process” and cellular components categories and Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) restricting the output to biological processes (BP) and cell components (CC) and KEGG pathway gene sets. Moreover, a custom GSEA was performed to verify the significant modulation of the mitochondrial respiration process. These analyses consistently associated Pex5 deletion with the downregulation of genes involved in mitochondrial respiration, mitochondrial ATP synthesis, fatty acid oxidation, and the generation of precursor metabolites and energy (Fig. 3A, B, Supplementary Fig. 4A, and Supplementary Data 3, 4). Accordingly, a cluster of 25 Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) closely associated with mitochondrial functions, particularly mitochondrial respiration, and fatty acid oxidation, exhibited downregulation exclusively at the 9- and 18- month timepoints (Fig. 3C, and Supplementary Data 5). Importantly, the age-dependent decline in mitochondrial transcripts in KO muscle is associated with progressive changes in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (Fig. 3D) and citrate synthase activity (Fig. 3E), two commonly used markers of mitochondrial content35,36. In line with this, quantitative analysis of mitochondrial number through electron microscopy reveals a progressive reduction in KO muscle from 9 to 18 months (Fig. 3F).

Mitochondrial content depends on the balance between mitochondrial degradation and mitochondrial biogenesis. To analyze if the reduction in mitochondrial content depends on the degradation of damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria through mitophagy, we employed mitochondrial-targeted Keima probe (mt-Keima) transfection to assess the mitophagy flux in FDB fibers. We observed an induction of mitophagy flux in KO muscle fibers at 9 months (Fig. 3G and Supplementary Fig. 4B) along with a progressive reduction in the protein levels of the master regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis PGC1α and PGC1β at both 9 and 18 months, thereby resulting in decreased mitochondrial content at this age (Fig. 3H, and Supplementary Fig. 4C).

Overall, these data indicate that Pex5 ablation in skeletal muscle results in a gradual decrease in mitochondrial content due to increased turnover of mitochondria by mitophagy, which is not counteracted by mitochondrial biogenesis. This likely exerts a substantial impact on metabolic signatures over time.

Progressive mitochondrial ultrastructural and functional alterations in Pex5-null skeletal muscle

To explore whether the alterations in mitochondrial signatures resulting from Pex5 loss in skeletal muscle affect mitochondrial integrity, we analyze mitochondrial ultrastructure in the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle using electron microscopy. This analysis reveals significant changes over time. At 3 months, the KO muscle closely resembles that of the control group, displaying a mitochondrial electron-dense matrix, parallel internal cristae, and mitochondria positioned at the I band near the Z lines (Fig. 4A). However, an early reduction in cristae number is already evident by 3 months and becomes more pronounced by 9 months (Fig. 4B). Moreover, by 9 months, some sporadic mitochondria in KO muscle exhibit swelling and disrupted cristae structures (Fig. 4A). In contrast, at 18 months, no evident defects are observed in the mitochondrial ultrastructure (Fig. 4A), and cristae number remains similar to 9 months in KO muscle but declines in control muscle, eliminating any significant difference between the groups at this stage (Fig. 4B). This is paralleled with a progressive increase in mitochondrial size in KO muscle from 3 to 18 months (Fig. 4B). Accordingly, the mitochondrial aspect ratio, defined as the length of the long axis relative to the short axis, progressively increases in KO muscle from 9 to 18 months (Fig. 4B). This suggests that peroxisomal dysfunction induces mitochondrial adaptations, leading to elongated mitochondria.

Fig. 4. Progressive mitochondrial ultrastructural and functional alterations in Pex5-null muscle.

A Representative EDL muscles electron micrographs of Ctrl and KO mice. B EDL muscle quantification of left: cristae number normalized to mitochondrial area; middle: mitochondrial area normalized to fiber area (m2); right: mitochondrial aspect ratio. Each dot represents a single mitochondrion analyzed, considering 10 mitochondria from 4 muscles per genotype at 3, 9 and 18mo. C Respiratory capacity in KO FDB myofibers compared to controls. Upper panel: representative traces, data shown as mean ± SEM. Lower panel: OCR quantification. Each dot represents a single FDB fiber analyzed (3mo: Ctrl n = 9, KO n = 8; 9mo: Ctrl n = 17, KO n = 16; 18mo: n = 12 Ctrl/KO). D Respiratory complex single enzyme activity normalized to citrate synthase activity. Each dot represents a single muscle analyzed (3mo: n = 4 Ctrl/KO; 9mo: n = 6 Ctrl/KO; 18mo: n = 7 Ctrl/KO). E Antioxidant enzymes mRNA levels in TA of 3, 9 and 18mo Ctrl and KO mice. PRX1 peroxiredoxin 1, GR1 glutathione reductase, CAT catalase, SOD1 and SOD2 superoxide dismutase 1 and 2. Each dot represents a single muscle analyzed (3mo: Ctrl n = 4; KO n = 7; 9mo and 18mo: n = 7 Ctrl/KO). F Left: Representative images of 3mo Ctrl and KO FDB fibers expressing SPLICSs-P2APO-MT probe. Co-localization of GFP fluorescent dots (SPLICS PO-MT) with anti-PMP70, labeling peroxisomes (PO), and anti-Tom20, labeling mitochondria (MT). Right: quantification of SPLICS PO-MT signal. Each dot represents a single FDB fiber analyzed (Ctrl n = 10; KO n = 15). G Number of PO-MT contacts in Ctrl and Pex5 KO HEK293 cells transfected with the SPLICS PO-MT probe. Each dot represents a single cell analyzed (Ctrl n = 48; KO n = 37). n = 3 replicates. H STED microscopy quantification of PMP70 and Tom20 colocalizing pixels per cell. Each point represents a single cell (Ctrl n = 55; KO n = 38). n = 3 replicates. Data are presented as violin plots (with individual data points). 3mo, 9mo and 18mo refer to samples from 3-, 9-, and 18-month-old mice. Two-sided Mann–Whitney test (B, F, G, and H), and multiple unpaired two-sided Welch’s t tests (C–E) were used when comparing two groups. Source data are provided as a source data file.

In line with these structural and morphological changes, the oxygen consumption rate (OCR), normalized by the fluorescence of total fiber calcein protein content, remained unchanged at 3 months but showed a gradual decline in KO muscles from 9 to 18 months. This decline affected the basal, ATP-linked, and maximal respiration (Fig. 4C). Additionally, measurement of the electron transport chain (ETC) mitochondrial respiratory complexes activity showed an age-dependent decrease. Normalization of the complex activities by citrate synthase activity, a marker of mitochondrial content, showed significant changes only at 18 months (Fig. 4D). This indicates that the reduction in mitochondrial content, already evident at 9 months, precedes the onset of mitochondrial dysfunction at 18 months. Consistent with the observed mitochondrial dysfunction, the expression of genes involved in antioxidant defense, critical for regulating ROS levels in skeletal muscle, is altered in KO muscle (Fig. 4E). Notably, catalase is already downregulated at 3 months and remains reduced up to 18 months, while SOD1 and SOD2 show reductions specifically at 9 months, coinciding with the decrease in mtDNA (Fig. 3D) prior to the onset of significative mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 4D). In addition, a set of DEGs related to fatty acid catabolism, displayed downregulation specifically at 9 and 18 months, with no such changes observed at 3 months (Supplementary Fig. 5A and Supplementary Data 6). Consistent with these findings, real-time PCR showed the downregulation of genes associated with mitochondrial β oxidation in KO muscles. Specifically, ACADM was downregulated at 9 and 18 months, while CPT1, CPT2, and ACADL were downregulated at 18 months, with no significant changes observed at 3 months. These results suggest potential alterations in mitochondrial lipid catabolism (Supplementary Fig. 5B).

Peroxisomes and mitochondria function synergistically, and their close association is thought to be essential for efficient metabolic cooperation. Although the mechanisms underlying their communication remain largely unclear, current evidence suggests that diffusion processes, vesicular transport, and physical connections at membrane contact sites (MCS) facilitate the transfer of metabolic intermediates necessary for key metabolic processes37–41. Our data regarding changes in Pex5-null muscles in peroxisomal function, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial content point to alterations in the peroxisome- mitochondria metabolic interaction. However, it remains unclear whether these changes are a cause or consequence of physical contact disruption between the two organelles. To explore whether peroxisome-mitochondria MCS can be remodeled under conditions of peroxisomal dysfunction, we employed the split-GFP-based contact site sensor (SPLICS PO-MT)42, which detects organelle interactions occurring within a range of 8–10 nm. This reporter is engineered to express equimolar amounts of the two organelle-targeted non-fluorescent GFP components β-strand 11 and GFP1-10 of the superfolded GFP protein variant within a single vector. These two GFP portions reconstitute fluorescence when their respective opposing targeted membranes come into close proximity43. Specifically, the peroxisome-mitochondria SPLICS (SPLICS PO-MT) reporter contains the C-terminal domain of the human ACBD5 protein as the peroxisomal targeting sequence in the β-strand 11, and the outer mitochondrial membrane Tom20 N33 targeting sequence in the GFP1–10 moiety43,44. By overexpressing the SPLICS PO-MT probe in vivo in FDB muscle fibers we observed a significant reduction in the number of peroxisome–mitochondria contact sites in KO muscle fibers at 3 months of age (Fig. 4F). Given that skeletal muscle is a unique tissue with densely packed contractile proteins and restricted cytoplasmic space, assessing organelle interactions can be constrained by these structural features. To address this, we validated our findings in a cellular model by employing the SPLICS PO-MT fluorescent reporter in both control and Pex5 KO HEK293 cells, where we similarly detected a marked decrease in peroxisome–mitochondria MCS in KO cells (Fig. 4G and Supplementary Fig. 4C). To overcome the spatial resolution limitations of conventional confocal microscopy and to examine organelle proximity in greater detail, we employed super-resolution stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy combined with immunostaining for the endogenous peroxisomal and mitochondrial markers PMP70 and Tom20, respectively. This high-resolution approach confirmed a significant reduction in peroxisomes–mitochondria proximity in Pex5 KO HEK293 cells (Fig. 4H and Supplementary Fig. 5D), further supporting the observations obtained with the SPLICS probe. Peroxisome–mitochondria MCS have been suggested to facilitate the exchange of metabolic intermediates between these organelles37–39. However, our observations in both Pex5 KO muscle tissue and HEK293 cells are insufficient to establish a causal relationship between disrupted physical contacts and the progressive metabolic alterations affecting mitochondrial ultrastructure and function. It should be noted that, the altered proximity between these two organelles may either be a consequence of their structural and functional changes or, conversely, a contributing factor driving organelle dysfunction. Further studies are required to elucidate the directionality and underlying mechanisms of these associations.

Pex5 deletion in muscle results in early muscle dysfunction

To explore the physiological role of Pex5 in controlling skeletal muscle mass, we focused on our mRNA sequencing data analysis, which revealed a clear association between Pex5 deletion, and the downregulation of transcripts associated with myofibril organization, muscle contraction, and muscle structure development at 3 months of age (Fig. 5A, and Supplementary Data 7). Notably, twelve genes involved in these processes exhibited significant downregulation (Fig. 5B, and Supplementary Data 8). Additionally, untargeted metabolomics analysis revealed significant differences in the intramuscular levels of amino acids in 3-month-old KO mice. Interestingly, KO muscle exhibited increased levels of glutamate, glutamine, asparagine, valine, aspartate, proline, phosphoserine, serine, histidine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine compared to controls (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. 6A). The accumulation of these amino acids has been associated with enhanced protein breakdown in conditions characterized by metabolic dysregulation, muscle weakness, and muscle loss45,46. To investigate if the transcriptomic and metabolic alterations correlate with functional defects, we assessed hindlimb muscle force in live 3-month-old animals subjected to contractions after electrical stimulation at increasing frequencies until tetanus was reached. The force–frequency curve (Fig. 5D) and maximal tetanic force (100 Hz) (Fig. 5E), normalized for gastrocnemius muscle mass (Supplementary Fig. 6B), revealed reductions at 3 months and 18 months. Notably, muscle weakness was not associated with muscle mass loss, as cross-sectional area measurements of TA fibers at 3 months indicated no differences in size distribution between control and KO fibers (Fig. 5F). However, by 9 months, there was a significant reduction in the number of fibers, with cross-sectional areas ranging from 2500 to 3000 μm² (Fig. 5G). By 18 months, KO muscle fibers showed an increased prevalence of smaller sizes, ranging from 1000 to 1500 μm², accompanied by a decrease in the number of fibers ranging from 3000 to 4000 μm² (Fig. 5H). The alterations in fiber size were unrelated to changes in fiber type distribution, which remained consistent across all ages in both control and KO muscles (Supplementary Fig. 6C).

Fig. 5. Pex5 deletion in skeletal muscle results in early-onset muscle weakness, preceding muscle atrophy.

A Biological Processes (BP) and Cellular Components (CC) inhibited at 3mo. The Enrichment Score of each term is plotted. B Heatmap of 12 muscle contraction-related genes significantly inhibited in KO vs Ctrl GNM muscles at 3mo. C Amino acids concentration in GNM muscles from 3mo mice. Each dot represents a single muscle analyzed (Ctrl n = 4; KO n = 7). D Normalized force–frequency curve of Ctrl and KO mice at 3 and 18mo. Data shown as mean ± SEM. E Normalized maximal tetanic force. D, E Each dot represents a single muscle analyzed (3mo: Ctrl n = 7; KO n = 13; 18mo: Ctrl n = 6; KO n = 8). Fiber size distribution of control and KO TA muscle at 3 (F), 9 (G), and 18mo (H). Data shown as mean ± SEM in columns. 3mo: n = 4 Ctrl, n = 3 KO (F); 9mo: n = 7 Ctrl, n = 7 KO mice (G); 18mo: n = 6 Ctrl/KO mice (H). G p-value a = 0.0058, b = 0.0044, c = 0.0028. H p-value a = 0.0085, b = 0.0013, c = 0.0329, d = 0.0279, e = 0.0288, f = 0.0118. I mRNA levels of atrophy-related genes in TA muscle of 9mo control and KO mice. Left: ubiquitin-proteasome-related genes; middle: autophagy-related genes; right: ER stress-related genes. Each dot represents a single muscle (Ctrl n = 6; KO n = 5). J Fbxl22 mRNA levels in TA muscles at 3, 9, and 18 months. Each dot represents a single muscle (3mo: Ctrl n = 4; KO n = 7; 9mo: Ctrl n = 6; KO n = 5; 18mo: Ctrl n = 6, KO n = 7). K Running distance until exhaustion of Ctrl and KO mice at 3 and 18 months. Each dot represents a single mouse (3mo: Ctrl n = 5; KO n = 3; 18mo: Ctrl n = 5; KO n = 7). 3mo, 9mo and 18mo refer to samples from 3-, 9-, and 18-month-old mice. Unpaired two-sided Welch’s t tests (C, E lower panel, J), Mann–Whitney test (E upper panel), or multiple unpaired two-sided Welch’s t test (F–I) used when comparing two groups. A two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test performed when comparing more than two groups (K). Source data are provided as a source data file.

To explore the signaling pathways that contribute to muscle atrophy, we analyzed the levels of atrogenes, which are genes commonly altered in catabolic conditions47. At 9 months, the ubiquitin ligase MUSA1 was significantly upregulated in the KO muscle, while the upregulation of Atrogin1, MuRF1, FoxO3, and FoxO4 in KO muscle was nearly significant (Fig. 5I). Additionally, the expression of the mitophagy-related gene Bnip3 increased in the KO muscle, consistent with the enhanced mitophagy flux observed at this age (Fig. 3G, and Supplementary Fig. 4B). Moreover, transcripts associated with the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), including GADD34 and XBP1, were induced in KO muscle (Fig.5I). However, by 18 months, mRNA levels of atrogenes related to ubiquitin-proteasome, autophagy, and UPR were similar to those in control muscle, except for FoxO1, which was upregulated in the KO muscle (Supplementary Fig. 6D). This shift from induction to normalization of atrogenes between 9 and 18 months suggests that the activation of these genes precedes the onset of muscle loss in the KO mice. In addition, our RNA-seq data highlighted the induction of the novel F-box E3 ubiquitin ligase Fbxl22 in KO muscle at 18-month-old (Supplementary Fig. 6E). Prior studies have demonstrated that Fbxl22 overexpression is sufficient to induce muscle atrophy48. Consistent with the gradual changes observed in the cross-sectional area of KO muscles (Fig. 5F–H), real-time PCR analysis showed the increase of Fbxl22 mRNA levels from 9 to 18 months in Pex5-deleted muscle (Fig. 5J).

To further evaluate the consequences of Pex5 ablation on muscle performance in vivo, we subjected mice to treadmill exercise until exhaustion. Interestingly, 3-month-old KO mice covered approximately 30% less distance before reaching exhaustion compared to controls (Fig. 5K). This suggests that peroxisomes play a crucial role in sustaining endurance during exercise, a role that becomes apparent even at this early stage, coinciding with initial changes in lipid metabolism. It’s noteworthy that the reduced exercise capacity observed in 3-month-old KO mice mirrors the age-related decline seen in both control and KO mice at 18 months (Fig. 5K).

Collectively, these findings indicate that the alterations in transcriptomic, lipidomic, and metabolic profiles triggered by peroxisomal dysfunction in the skeletal muscle of 3-month-old KO mice trigger premature muscle weakness, preceding the progressive muscle atrophy observed between 9 and 18 months. Moreover, the similarity in running capacity between young KO mice and 18-month-old control mice suggests an accelerated decline in exercise performance likely driven by peroxisomal deficiency and early mitochondrial cristae alterations observed at 3 months. These findings position young knockout mice at a performance level comparable to that of older control mice.

Age-associated myopathy and neuromuscular junction degeneration occurs earlier in Pex5 KO mice

To assess the impact of Pex5 deletion on muscle health, we performed a histological analysis of the TA muscle through H&E staining in both control and KO mice. At 3 months, the H&E staining revealed no signs of muscle degeneration, regeneration, or inflammation in KO muscle sections (Fig. 6A). However, at both 9 and 18 months, KO muscle exhibited a similar increase in the number of center-nucleated muscle fibers compared to age-matched controls (Fig. 6A). The mispositioning of myonuclei is a common hallmark of myofiber degeneration and regeneration observed in human myopathies and aging sarcopenia49.

Fig. 6. Pex5-null muscles exhibit an early development of sarcopenic features.

A Left: representative Hematoxylin & Eosin staining of TA. Arrowheads: center nuclei in 9- and 18mo KO mice. Right. Quantification of fibers with center nuclei over total fiber number in muscle section. Each dot represents one single muscle (9mo: n = 7 Ctrl/KO; 18mo: Ctrl n = 8, KO n = 10). B Electron micrographs representative images showing ultrastructural defects in 18mo KO EDL muscle. C Representative images of modified Gomori trichrome staining of TA muscle from 18mo control and KO mice. D Left: Quantification of fibers with tubular aggregates (stained in red in (C)) relative to the total fiber number in muscle section of 18mo mice. Right: Quantification of aggregate area normalized to fiber area. Each dot represents one single muscle (Ctrl n = 6; KO n = 5). E Upper panel: immunoblot of total protein extracts from TA muscles of 18mo mice. Lower panel: Densitometric analysis. Data normalized to GAPDH. Each dot represents one single muscle (n = 7 Ctrl/KO). F Left: Representative image showing NCAM positive fibers in TA KO muscles at 18mo. Right: Quantification of NCAM-positive fibers relative to the total fiber number in the muscle section. Each dot represents one single muscle (Ctrl n = 8; KO n = 11). G Indirect immunofluorescence on EDL muscles. Magenta: post-synaptic AChRs stained with α-BTx; cyan: pre-synaptic compartment identified with anti-VAMP1 antibody. Asterisks identify denervated NMJs, arrows partial denervated ones. Scale bar: 50 µm. Magnification of innervated, partial denervated and denervated NMJs shown in the right panel (10 µm). H Quantification of innervated, partial denervated, and denervated NMJs in EDL of 18mo mice. Each dot represents one muscle (n = 3 Ctrl/KO), 30 NMJs analyzed/muscle. Unless otherwise stated, all data in this figure were obtained from the analysis of 18mo mice muscles. Data presented as violin plots (with individual data points). 3mo, 9mo and 18mo refer to samples from 3-, 9-, and 18-month-old mice. Unpaired two-sided Welch’s t tests (A, E, F), Two-sided Mann–Whitney test (D), and multiple unpaired two-sided Welch’s t tests (H) were used when comparing two groups). Source data are provided as a source data file.

Therefore, to investigate myofiber integrity, we monitored the muscle ultrastructure of the EDL muscle by electron microscopy. We observed a consistent accumulation of ultrastructure defects over time. At 3 months, muscle ultrastructure in KO is like controls, exhibiting a regular sarcomeric structure (Supplementary Fig. 7A, upper panel). By 9 months, KO muscles presented sporadic disorganized sarcomere arrangements (Supplementary Fig. 7A, lower panel). However, at 18 months KO muscles exhibited a higher frequency of sarcomere alterations (Fig. 6Ba), including Z-line smearing (Fig. 6Bb), and the presence of tubular aggregates (Fig. 6Bc). Tubular aggregates, derive from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) expansion and are associated with several skeletal muscle disorders, as well as normal and accelerated aging50. In light of this, we use modified Gömöri trichrome staining to examine 18-month-old muscles (Fig. 6C). We quantified both the number of fibers presenting the tubular aggregates and the area occupied by these aggregates within each fiber, which appeared as bright red subsarcolemmal inclusions within the TA sections. KO muscles show a significant increase in the percentage of fibers displaying tubular aggregates, with a corresponding increase in the area occupied within the fibers (Fig. 6D).

To better understand why sarcomere integrity is affected by Pex5 deletion we focused on the novel F-box E3 ubiquitin ligase Fbxl22, which is upregulated in KO muscle at 18-month old (Fig. 5J and Supplementary Fig. 6E). Fbxl22 has been reported to promote sarcomeric turnover by targeting Z-line proteins, including filamin-C and α-actinin, for proteasomal degradation in cardiomyocytes51, while in skeletal muscle, only α-actinin has been demonstrated as an Fbxl22 target substrate for ubiquitination so far48. Immunoblot analysis of Z-line proteins revealed a reduction of ~40% in α-actinin and 35% in MyoZ protein levels within the KO muscle at 18 month (Fig. 6E), while filamin-C and CapZ protein levels remained unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 7B). Therefore, Fbxl22 induction likely leads to progressive disassembly of the sarcomere structure, potentially contributing to the observed muscle atrophy in the KO muscle (Fig. 5F–H). Moreover, Fbxl22 is early induced during muscle denervation, and its knockdown partially protects against denervation-induced muscle loss48. Because FoxO1 gene was upregulated in 18-month-old KO mice and FoxOs play a critical role in atrogenes regulation52, we hypothesized that also Fbxl22 is under FoxO regulation. Notably, several putative FoxO-binding elements in the promoter region of Fbxl22 have been identified by bioinformatic analysis. To investigate whether FoxOs control Fbxl22 expression, we used a 3-month-old muscle-specific mouse model lacking FoxO1, FoxO3, and FoxO4, which we have previously characterized47. Our findings further support this correlation by revealing a significantly upregulation of Fbxl22 in the muscles of control mice after 3 days of denervation. Conversely, Fbxl22 upregulation was blunted in denervated FoxOs-deficient mice, suggesting Fbxl22’s dependence on FoxO signaling (Supplementary Fig. 7C). Since Fbxl22 is upregulated during denervation, and we observed increased Fbxl22 transcripts levels in 18-month-old KO muscle (Fig. 5J and Supplementary Fig. 6E), we investigated whether loss of myofiber innervation could occur in Pex5 deficient muscle. Real time PCR analysis at 18 months showed the significant upregulation of established denervation markers such as muscle-associated receptor tyrosine kinase (MUSK) and runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX)53,54 (Supplementary Fig. 7D). The expression of the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), which is typically enriched in the postsynaptic endplates of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) and transiently redistributed on muscle fibers upon denervation, was significantly increased in the 18-month KO muscle (Fig. 6F). Next, we analyzed the NMJ morphology by immunostaining the presynaptic side for the synaptic vesicle protein VAMP1 and the post-synaptic NMJ component with fluorescently labeled α-bungarotoxin, which tightly binds to acetylcholine receptors (AChRs). Innervated fibers were identified by the complete overlap observed by confocal microscopy between the pre- and post-synaptic components. Partial and complete denervation were recognized by the partial or complete mismatch between the two signals. EDL muscle from control mice exhibited an almost complete colocalization of synaptic vesicle VAMP1 and postsynaptic AChRs signals. Conversely, 18-month-old KO mice exhibited a variable degree of mismatch between pre- and post-synaptic structures, with an increased proportion of partial and complete denervated NMJs and a reduction of the innervated NMJs compared to control EDL muscle (Fig. 6G, H).

In conclusion, peroxisome assembly deficiency in skeletal muscle triggers metabolic alterations in lipid and amino acid homeostasis, along with early alterations in mitochondrial cristae content, negatively affecting muscle force and exercise performance. Gradually, these changes first affect mitochondrial content, subsequently impairing mitochondrial function. Over time, the cumulative effects lead to muscle atrophy and the development of a myopathic phenotype, characterized by the accumulation of tubular aggregates, proteolytic breakdown of sarcomeres, and degeneration of the neuromuscular junction. Together, these processes contribute to the accelerated progression of aging-associated sarcopenia, as summarized in (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Schematic overview of the phenotypical alterations observed in the muscle-specific Pex5 KO mouse model.

Upper panel: In control mice, a reduction in peroxisomal content, early mitochondrial alterations such as decreased mitochondrial cristae number, and reduced exercise performance are already evident by 18 months of age. These precede the age-related defects typically observed after 24 months, including further peroxisome loss, progressive mitochondrial dysfunction, and consequential impairments in muscle structure, metabolism, strength, and mass. The decline in muscle force and mass is known as sarcopenia. Lower panel: Pex5 deletion in skeletal muscle leads to abnormal peroxisomal assembly with impaired peroxisomal protein import (peroxisomal ghosts). These changes result in pexophagy flux impairment, altered lipid and amino acid metabolism, reduced mitochondria cristae number, early decline in muscle force, and reduced exercise performance by 3 months of age. Moreover, at this stage, peroxisome (PO)-mitochondria (MT) proximity is reduced, however, the causal or consequential nature of this relationship remains unclear. By 9 months, mitochondrial content is affected, characterized by reduced mitochondrial biogenesis and increased mitophagy. At 18 months, KO muscles exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction and an accelerated onset of age-related muscle atrophy and impairment, marked by the accumulation of tubular aggregates, proteolytic sarcomere breakdown, and neuromuscular junction degeneration. The alterations occurring earlier in KO mice compared to control mice are highlighted in red. Created in BioRender. DAVIGO, I. (2025) https://BioRender.com/bp2gfbd.

Peroxisomal content declines progressively with age

To further investigate the role of functional peroxisomes in maintaining muscle mass and force during aging, we analyzed TA muscles from C57BL/6J (control) mice across different life stages, including both adult and sarcopenic phases. As expected, 26-month-old sarcopenic mice, exhibited significantly reduced muscle force and mass compared to 3-month-old mice (Fig. 8A). We first evaluated the transcriptional levels of genes involved in peroxisomal biogenesis (Pex1, Pex5, and Pex12), peroxisomal β-oxidation (ACOX1), ROS detoxification (catalase (CAT)). Among these, Pex5, Pex12, and catalase were significantly downregulated in sarcopenic muscle (Fig. 8B). To determine whether peroxisomal changes occurred progressively with age, we analyzed peroxisomal protein levels in TA muscles from control mice at 3, 9, 18 and 26 months of age. We observed an age-dependent reduction in the levels of Pex5, PMP70, and both the 79 kDa cytosolic full-length and the 45 kDa peroxisomal-processed forms of MFP2, with statistically significant reductions becoming evident at 18 months of age (Fig. 8C). Consistent with these findings, the number of peroxisomes, assessed by PMP70 immunostaining and visualized using super-resolution STED microscopy, declined significantly at 18 months and was further reduced by 26 months of age (Fig. 8D, E). Altogether, these findings in control muscle demonstrate progressive, age-dependent alterations in peroxisomal content, with significant changes emerging before the decline in muscle force and mass characteristic of sarcopenia (Fig. 7, upper panel).

Fig. 8. Progressive age-dependent alterations in peroxisomal content and size.

A Left: Muscle force assessed by grip test; right: TA fiber size assessed by CSA analysis. Each dot represents one mouse (left) or muscle (right) (n = 5 Ctrl/KO). B mRNA levels of peroxisomal genes involved in peroxisomal biogenesis (Pex1, Pex5, and Pex12), peroxisomal β-oxidation (ACOX1), and ROS detoxification (catalase (CAT)) in TA muscles from 3, and 26mo control mice. Each dot represents one muscle (3mo: n = 3 mice; 26mo: n = 4). C Upper panel: Immunoblot images of total TA muscle lysates from 3, 9, 18, and 26mo control mice, probed with anti-Pex5, PMP70, and MFP2, normalized to GAPDH levels. Lower panel: Densitometric quantification of Pex5, PMP70, and both the cytosolic 79 kDa and peroxisomal-processed 45 kDa (indicated at 43 kDa) forms of MFP2. Each dot represents one muscle (n = 4 per group). D Representative STED microscopy images of longitudinal sections of TA showing endogenous peroxisomes, immunostained with anti-PMP70, from 3, 18, and 26mo control mice. The 26 months panel shows two muscle fibers positioned side by side. E Quantification of the number of PMP70-positive structures normalized to muscle fiber area. Each dot represents a single TA muscle fiber analyzed (3mo: n = 69; 18mo: n = 73; 26mo: n = 54). Three muscles for each age were analyzed. Data are presented as violin plots (with individual data points). 3mo, 9mo,18mo, and 26mo refer to samples from 3-, 9-, 18-, and 26-month-old mice. Statistical tests: Unpaired two-sided Welch’s t tests (A); multiple unpaired two-sided Welch’s t tests (B); Brown–Forsythe and Welch ANOVA test (C); and non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test (E). Source data are provided as a source data file.

Discussion

Peroxisomal dysfunction has been implicated in the pathogenesis of age-related metabolic disorders, including diabetes, obesity, cancer, and aging sarcopenia, all characterized by muscle atrophy and impaired muscle function21,22. Here, we show that Pex5 is a novel player in the regulation of skeletal muscle homeostasis, playing a critical role in maintaining muscle health during aging. Using mice with muscle-specific deletion of Pex5, we demonstrate that the disruption of peroxisomal protein import results in abnormal peroxisome assembly, and decreased pexophagy flux within skeletal muscle, suggesting that Pex5 plays a crucial role in the quality control mechanisms that eliminate peroxisomes28–31. Moreover, under our experimental conditions, peroxisome turnover in control skeletal muscles is primarily mediated by the autophagy receptor NBR1, whereas p62 appears to play a secondary role. A report from the Kim lab demonstrated that NBR1 functions as a specific pexophagy receptor, whereas p62 enhances the efficiency of NBR1-mediated pexophagy31. Furthermore, Kim’s findings suggest that ubiquitylated Pex5 is required for the efficient recruitment of NBR1 to the peroxisomal surface. Consistent with this, they showed that blocking Pex5 recruitment to the peroxisomal membrane via Pex14 deletion was shown to decrease NBR1 binding to peroxisomes, significantly impairing pexophagy. In line with these observations, we found that in the absence of Pex5, the binding of both receptors to peroxisomes is reduced, indicating impaired pexophagy flux in KO muscle, with a more pronounced reduction in NBR1 binding compared to p62.

However, reports quantifying peroxisomal ghosts in Pex5-deficient contexts have been inconsistent. For example, cultured HEK and HeLa cells show no change55,56, whereas patient fibroblasts with Pex5 mutations27, Pex5 KO mouse models14,57, and adult zebrafish exhibit reduced peroxisomes, which in zebrafish occurs in an age-dependent manner58. Moreover, a study in a knock-in human lens epithelial cell line carrying a missense mutation in Pex5 reported no changes in peroxisome abundance or p62 levels under basal conditions. However, upon H2O2 treatment, both peroxisome number and p62 levels increased, indicating impaired pexophagy in response to oxidative stress59. These findings suggest that the abundance of peroxisomal ghosts could be context-dependent, influenced by cell type, age, and cellular stress, and that specific stressors may be required to unmask functional defects.

In parallel with changes in peroxisomal turnover, KO muscle exhibit alterations in lipid metabolism, characterized by a shift in the fatty acid composition of phospholipid species, such as phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and cardiolipins (CL), towards very long-chain unsaturated fatty acids, while simultaneously reducing phospholipid species with shorter fatty acid chains. Furthermore, there is a decrease in ether lipid species such as plasmalogens. Importantly, the overall lipidomic profile of Pex5-null muscles mirrors the observations made in PBD patient skin fibroblasts34.

Plasmalogens and phospholipids such as cardiolipin are important components of mitochondrial membranes60–62. Previous studies have highlighted their critical role in the maintenance of mitochondrial membrane structure, fluidity and integrity60,63,64. In fact, both plasmalogens and cardiolipin have a critical role in maintaining proper cristae folding and mitochondrial respiratory supercomplex assembly in the inner mitochondrial membrane33 contributing to mitochondrial respiration efficiency. Recent findings also highlight the role of peroxisomal-derived plasmalogens in maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis61. Peroxisomal dysfunction resulting from adipose-tissue specific Pex16 deletion or the inhibition of plasmalogen synthesis due to glyceronephosphate O-acyltransferase (GNPAT) knockdown leads to a reduction in mitochondrial content and the formation of elongated, dysfunctional mitochondria. Importantly, plasmalogen supplementation rescues these defects, underscoring their potential therapeutic significance61. In parallel with changes in plasmalogen and cardiolipin levels, we observed early mitochondrial alterations in KO muscle, such as a reduction in cristae number appearing as early as 3 months of age, followed by a gradual decline in mitochondrial content from 9 to 18 months. The mitochondrial content reduction is caused by the inhibition of PGC1-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis pathways at both 9 and 18 months of age, together with activation of mitophagy at 9 months. The activation of mitophagy likely serves as a beneficial mechanism. It helps to clear organelles affected by alterations in mitochondrial membrane lipid composition, thus maintaining a healthy mitochondrial population in KO muscle tissue at this age. Conversely, by the time KO mice reach 18 months of age, mitochondrial function and mitochondrial lipid metabolism are compromised. In line with these alterations, KO muscles display a reduction in antioxidant enzymes, paralleling the decrease in mtDNA content at 9 months, a critical point, as mtDNA is highly vulnerable to oxidative damage65, and occurs prior to the development of mitochondrial dysfunction. Moreover, between 9 and 18 months, there is a progressive and dynamic morphological adaptation in mitochondrial size characterized by elongation, likely serving as a tentative mechanism to enhance metabolic efficiency66–68. Importantly, several structural and functional mitochondrial alterations are common features observed in both PBD patients and in other Pex5-deficient models13,16–19.

Furthermore, lipid biosynthetic pathways are highly interconnected and rely on the coordinated activity of different organelles, including peroxisomes, ER and mitochondria63. Disruptions in lipid metabolisms can impair the communication between peroxisomes and mitochondria63. Although the mechanisms and functional significance of inter-organelle communication remain to be fully elucidated, current evidence suggests that diffusion, vesicular transport, and direct physical contacts at MCS sites facilitate the exchange of metabolic intermediates essential for key metabolic processes37–41. Our data, obtained using the SPLICS PO-MT probe and super-resolution STED microscopy, reveal a decrease proximity between peroxisomes and mitochondria in both skeletal muscle and HEK293 cells KO for Pex5. Although our observations of altered lipid metabolism and mitochondrial structure and function in Pex5 KO muscle suggest disruptions in the metabolic interactions between these organelles, we did not explore the physiological consequences of this altered tethering. Moreover, our work has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, while we observed decreased peroxisomes–mitochondria proximity in the absence of Pex5, these findings are insufficient to determine the metabolic impact of reduced tethering. Second, it remains unclear whether the disruption of contacts arise directly from Pex5 loss or indirectly from the resulting structural and functional defects on both organelles. Third, although our data suggest a correlation between Pex5 and organelle proximity, we did not evaluate whether Pex5 itself functions as a physical tether, whether it is enriched at peroxisomes–mitochondria contact sites, or whether it plays a mechanistic role in facilitating metabolite exchange, as suggested in ref. 69. Therefore, further studies are needed to define both the molecular mechanisms and physiological relevance of peroxisome–mitochondria contact sites in the context of Pex5 deficiency, both in vitro and in vivo.

Concomitant with alterations in lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism is also perturbed in KO muscle, suggesting a coordinated impairment of metabolic processes at this early stage. Increased levels of free amino acids such as glutamine, glutamate, asparagine, and aspartate have been linked to increased protein breakdown in conditions characterized by metabolic dysregulation, muscle weakness, and muscle loss45,46. Furthermore, the levels of arginine and lysine, whose reduction has been identified as a metabolic signature of unhealthy aging70, were decreased in the KO muscle. The changes on lipid and amino acid metabolism parallel the decline in muscle force and exercise performance, occurring simultaneously with a reduction in cristae number but preceding the decreases in mitochondrial content, mitochondrial function, as well as muscle atrophy. Notably, in conditions such as aging sarcopenia and cancer cachexia, muscle weakness precedes muscle atrophy4,71,72, indicating that age-related muscle dysfunction depends not only on muscle size but also on muscle quality73. Therefore, muscle weakness and exercise intolerance may result from impaired peroxisomal function and the consequent metabolic uncoupling from mitochondria, leading to disruptions in lipid and amino acid metabolism as well as a reduction in cristae number. Importantly, the progression of muscle loss reflects the cumulative, time-dependent deterioration of mitochondrial content, morphology, and function, underscoring the long-term consequences of the disrupted peroxisome–mitochondria synergy. Accordingly, we and others have consistently demonstrated that alterations in mitochondrial content, shape, or function have detrimental consequences for the maintenance of muscle mass and function10,68. Moreover, oxidative stress is a major contributor to muscle loss52; accordingly, the antioxidant response progressively declines with age in KO muscle, with a more pronounced reduction observed at 18 months. Additionally, several atrogenes are upregulated in KO muscle at 9 months. These cumulative defects, driven by peroxisomal dysfunction, ultimately result in muscle atrophy and the early onset of a sarcopenic phenotype by 18 months of age. This phenotype is characterized by increased center-nucleated fibers, myofiber damage due to tubular aggregate accumulation, Fbxl22-dependent proteolytic breakdown of sarcomeres impacting structural integrity and sarcomeric Z line function, and neuromuscular junction degeneration. The fact that specific inhibition of Pex5 in skeletal muscle can induce muscle denervation without directly impacting the motor neuron was unexpected. This finding contrasts with the traditional belief in the context of PBD, where muscle alterations are typically considered secondary to neurological defects. However, our findings, along with other reports12,13,74, indicate that peroxisomal metabolic activity is required for muscle innervation and function independently of neurological involvement.

NMJs are critical regions where muscle and nerve communicate, influencing each other. In fact, skeletal muscle has a critical role in determining neuron survival, nerve integrity and functional NMJ maintenance. Numerous observations suggest the significant role of retrograde muscle-to-nerve signaling in NMJ maintenance75. For example, mitochondrial dysfunction, specifically in skeletal muscle fibers, correlates with a marked increase in fiber denervation75–78. In addition, plasmalogen deficiency in mice leads to alterations in NMJ formation and decreased muscle force79. Notably, plasmalogens, enriched in healthy muscles80, are reduced in skeletal muscle from PBD patients81, which are characterized by mitochondrial myopathy, muscle weakness, and muscle atrophy12,13,82–84.

The close association between peroxisomal defects and muscle dysfunction is demonstrated also in a muscle-specific Pex3 knockdown in a Drosophila model where the disruption of peroxisome biogenesis results in the impairment of various processes reliant on muscle function, including eclosion, wing expansion, and climbing74.

Lipid profiling of 18-month-old Pex5 KO muscle provides further evidence for accelerated age-related skeletal muscle decline, as it mirrors alterations observed in sarcopenia including increased PE, SM, and long- and very long-chain ceramides85–88. Notably, in aged mice and humans, PE negatively correlates with muscle mass and function85 and, ceramide synthesis inhibition preserves age- and cancer-cachexia-dependent muscle decline88,89. Furthermore, the relevance of peroxisomal function in the regulation of skeletal muscle during aging is highlighted by our results in control mice undergoing natural aging. We observed a progressive, age-dependent decline in the levels of PMP70, Pex5 and MFP2 peroxisomal proteins. Consistent with these findings, peroxisomal content assessed by PMP70 immunostaining and super-resolution STED microscopy showed a reduction beginning at 18 months and progressing further with age. Notably, these alterations precede the decline in muscle force and mass characteristic of sarcopenia. In line with our findings, Pex5 transcript and protein levels are reduced in the cortical neurons of aged mice90. Consistently, studies in C. elegans have shown that Pex5, along with nearly other 30 peroxisomal proteins decline with age, thereby impairing protein import91. Comparable defects are also observed in accelerated aging models like Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome92,93. We did not directly investigate peroxisomal import efficiency during aging, however, the concomitant decrease in both the full-length and processed forms of MFP2 suggests a general decline in peroxisomal content, potentially complicating the interpretation of peroxisomal import capacity.

In summary, our muscle-specific peroxisomal deficient mouse model underscores the importance of preserving peroxisomal function and their interplay with mitochondria to maintain muscle force, integrity, and innervation during the aging process. These findings may constitute the basis for identifying novel mechanisms fundamental to developing drug therapies aimed at preserving muscle function and enhancing the quality of life for individuals affected by peroxisomal disorders and age-related metabolic conditions.

Methods

Ethical approval for experiments involving animals, generation of muscle-specific Pex5 knockout mice, and housing conditions

All procedures are specified in the projects approved by the Italian Ministero della Salute, Ufficio VI (authorization number 328/2021 PR and 572/2021 PR) and are in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Use and care of Laboratory Animals and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. To generate constitutive muscle-specific Pex5 knockout animals, mice bearing Pex5 floxed alleles23 (Pex5f/f) (provided by Myriam Baes) were crossed with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of a Myosin Light Chain 1 fast promoter (MLC1f-Cre)24. Mice were maintained on a 12-h light/12-h dark schedule and were fed standard rodent food chow and water ad libitum. Animals were handled by specialized personnel under the control of inspectors of the Veterinary Service of the Local Sanitary Service (ASL 16 - Padova), the local officers of the Ministry of Health. Denervation was performed by cutting the sciatic nerve of the left limb, while the right limb was used as control. Surgical procedures, including sciatic nerve cutting and muscle electroporation, were performed under inhalation of isoflurane in medical oxygen with post-operative analgesia administered using carprofen or meloxicam. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the different tissues were weighed and then frozen in liquid nitrogen, and utilized for histological experiments, immunohistochemistry or gene expression studies. A mixed pool of both males and females were used in all the experiments. Experiments were performed on 3, 9, 18 and 26-month-old adult mice. Cre-negative littermates were used as controls.

Body composition analyses

Quantitative magnetic resonance was utilized to measure lean and fat mass in live mice using the EchoMRITM-100 system (EchoMRI LLC).

Exercise studies

Mice aged 3 and 18-month old were acclimated to and trained on a treadmill with no inclination (Biological Instruments, LE 8710 Panlab Technology 2B) over a period of three days. During these 3 consecutive days preceding the test, mice ran for 5 min at 10 m/min. On the fourth day, mice underwent a single bout of running starting a speed of 10 m/min. Forty minutes later, the treadmill speed was increased by 1 m/min every 10 min for a total of 30 min, followed by an increase of 1 m/min every 5 min until mice were exhausted. Exhaustion was defined as the point at which mice spent more than 5 s on the electric shocker without attempting to resume running. Total running distance was calculated for each mouse.

Rapid PeroxoTag peroxisome purification

Gastrocnemius (GNM) muscles from control and KO mice were injected with AAV9 carrying the PeroxoTag vector27, which encodes an HA-tagged EGFP-PEX26 construct, at a dose of 5 × 10¹⁰ vector genomes. PeroxoTag expression was driven by the human skeletal actin (HSA) promoter to ensure its selective expression in mature muscle fibers. Four weeks post-infection, peroxisomes were immunopurified starting from freshly isolated mouse GNM muscles exploiting PeroxoTag overexpression25. For every PeroxoTag infected muscle, the empty vector infected contralateral muscle was used in mock purifications to establish nonspecific background.

Briefly, GNM was dissected, separated from soleus muscle and minced with scissors on an ice-cold metal block; subsequently, tissue disruption was performed in 1 ml ice-cold PBS additioned with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (cOmplete EDTA-free and PhosSTOP, Roche) using a 2 ml borosilicate glass tissue grinder with a ground-glass pestle (Kimble Kontes, 885500-0021). 25 stokes were used for optimal cellular homogenization.