Abstract

Lewy body diseases, including Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies, often involve mild cognitive impairment at diagnosis (mild cognitive impairment with Lewy bodies (MCI-LB). Language dysfunction in MCI-LB patients is often unrecognized. This study aimed to assess syntactic comprehension deficits in MCI-LB patients and to explore their neural correlates. A total of 25 MCI-LB patients (mean ± sd: 72 ± 5.6 years old, 10 women) and 25 healthy controls (HC, mean ± sd: 66 ± 4.0 years old, 12 women) performed task functional MRI Test of Sentence Comprehension (ToSC). Functional connectivity was analysed using psychophysiological interaction (PPI) method, focusing on the striatum and language networks. MCI-LB patients had lower ToSC scores than HC (MCI-LB: 74.7 ± 15.7, HC: 88.5 ± 9.0, P < 0.001) and their PPI analysis revealed decreased connectivity from the striatum to the cuneus, precuneus, and left supramarginal gyrus, and reduced connectivity particularly in the dorsal pathway during noncanonical (syntactically more complex) sentence processing. Taken together, in this cross-sectional study MCI-LB patients showed impaired sentence comprehension related to decreased subcortical-cortical and dorsal language network connectivity. Specific changes in frontotemporal connectivity in MCI-LB might be a promising indicator of language related cognitive impairment in these a-synucleinopathies.

Keywords: language dysfunctions, mild cognitive impairment, Lewy body diseases, functional MRI, brain connectivity

Novakova et al. report that patients with mild cognitive impairment with Lewy bodies demonstrated impaired comprehension of syntactically complex sentences as compared to healthy controls. Task-related reduced functional connectivity in these patients within specific subcortical-cortical and language networks was identified and distinct alterations in the dorsal pathway were linked to processing of syntactically complex sentences.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

One of the most important human functions is the ability to communicate; the loss or limitation of this ability has devastating impacts on the individual and those around them. Language processing and the use of complex sentence structures are key features that distinguish human language from other forms of communication observed in non-human species. Syntactic comprehension is a hallmark of human communication, enabling the understanding and interpretation of how words are arranged in a sentence to express specific meanings.1 In English, grammatical relations between words are primarily determined by a fixed word order. Changing the order of the nouns in a sentence, such as from The mother is kissing the daughter to The daughter is kissing the mother alters the meaning entirely. Noncanonical sentences (The daughter is kissed by the mother, non-canonical order in English is accomplished mostly by using passive structures) include syntactically complex sentences in which the first noun is a receiver of action (not a doer), making them more difficult to understand. In contrast, Slavic languages like Czech rely on a more flexible word order, with grammatical relations indicated by case markings on nouns (e.g. nominative–NOM and accusative–ACC). For instance, a Czech sentence in a canonical word order might be Máma (NOM) líbá dceru (ACC), meaning The mother is kissing the daughter. A noncanonical equivalent, Dceru (ACC) líbá mámu (NOM), conveys the same meaning—The mother is kissing the daughter—despite the different word order.3 For an example of the test task see Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Test of sentence comprehension, sample picture. English translation: The daughter (accusative) is kissed by the mother (nominative) in the white dress (noncanonical word order in Czech, active). We have the permissions from the original authors of the images to include it in our manuscript (Nohová et al. 2022).2

Functional magnetic resonance imaging enables the study of the neural correlates of language function in living humans. The functional connectivity of the language network (domain-specific areas) consists of two basic pathways: dorsal (connecting the inferior frontal gyrus and the premotor area with the posterior superior temporal gyrus and inferior parietal lobe via the arcuate fasciculus), which is mainly involved in auditory-motor integration, speech production and repetition, and phonological processing; and ventral (connecting the superior and middle temporal gyrus, inferior parietal lobe, and occipital lobe with the inferior frontal gyrus via the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus), which is mainly involved in speech comprehension and semantic processing.4 In addition to domain-specific areas, a domain-general network related to language is also involved: the bilateral fronto-insular-parietal system, which reflects general cognitive efforts proportional to the difficulty of the task.5

Neuronal Lewy body diseases (LBDs) consist of two major clinical entities – Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (LB). The vast majority of patients with LBDs already have mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at the time of the diagnosis. Language dysfunctions in patients with LBDs with MCI (MCI-LB) are often unrecognized and negatively affect the patient’s quality of life. Behavioural and neuroimaging studies previously demonstrated that patients with LBDs exhibit deficits in sentence comprehension, particularly when processing complex syntactic structures.6-11 In healthy subjects, a meta-analysis of functional imaging studies has suggested the dorsal language pathway as critical for processing syntactically complex sentences.12 Complementary, evidence from patients with post-stroke aphasia and primary progressive aphasia further shows that damage to the dorsal pathway strongly predicts deficits in syntactic comprehension.13-16

We previously found that Slovak patients with PD without MCI already have problems with sentence reading comprehension with altered task-dependent functional connectivity.3 We aimed to continue our previous research3 and describe specific alterations in comprehending syntactically complex sentences in LBDs that already have MCI (MCI-LB patients) as compared to healthy controls (HC) and identify the neural underpinnings of these deficits using functional connectivity analysis from the striatum (the area involved in syntactic sentence processing and affected by the disease) and in language areas (divided into dorsal and ventral pathways4). We hypothesized that MCI-LB patients demonstrate greater behavioural impairments in comprehending syntactically complex sentences than HC. These deficits would be especially apparent for noncanonical sentences (our sentences of interest), and we would be able to identify neural correlates of behavioural deficits in MCI-LB as compared to HC in striato-cortical and language-related domain-specific networks. We further hypothesized that MCI-LB patients would show reduced functional connectivity of these large-scale brain networks compared to HC.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 25 MCI-LB (mean ± sd: 72 ± 5.6 years old) and 25 HC (mean ± sd: 66 ± 4.0 years old) participated in the fMRI study. Inclusion criteria were right-handedness, Czech as their first language, age (60–80 years), presence of PD-MCI17 or MCI-LB.18 We recruited participants from our study cohorts.19,20 All participants underwent a neuropsychological examination prior to fMRI scanning that consisted of a short neuropsychological battery21 (testing six cognitive domains: short-term memory, visuospatial functions, language functions, attention, executive functions, and long-term memory), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test (MoCA),22 the Boston Naming Test (BNT),23 the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)24 and the Czech version of the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQcz).(25) MCI subjects had subjective cognitive complaints and scored with at least two neuropsychological tests with a cutoff score under −1.5 standard deviation (SD) below the age-appropriate norms or with one test with a cutoff score under −1.5 SD below the age-appropriate norms plus a MoCA cutoff score of 26. PD-MCI patients had MCI and clinically established PD, were longitudinally followed by a neurologist, and were on a stable dopaminergic medication (mean Levodopa Equivalent Dose = 942 ± 399.6) at least 4 weeks prior to the baseline assessment and during the whole study and were tested in the ON medication state without dyskinesias. MCI-LB subjects were diagnosed with MCI and had at least two core clinical features of MCI-LB (fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, or REM sleep behaviour disorder, and one or more spontaneous cardinal features of parkinsonism). The exclusion criteria were a cardiac pacemaker or any MRI-incompatible metal in the body, epilepsy, any diagnosed psychiatric disorder, alcohol/drug abuse, and for the HC group additionally the presence of LBDs or other neurogenerative disorder or MCI/dementia. For more details see Table 1. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to calculate the differences between MCI-LB and HC. All subjects signed an informed consent form that had been approved by the local ethics committee.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample

| Factor | MCI-LBD/PD | HC | Test statistics of the between-group difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 25 | 25 | |

| Demographic variables | |||

| Sex | X 2 (1, N = 50) = 0.33 | ||

| Female (n) | 10 | 12 | |

| Male (n) | 15 | 13 | |

| Age (M ± SD) | 72 (± 5.54) | 66.2 (± 3.94) | U = 114.5, Z = −3.85a |

| Education Length (M ± SD) | 14.84 (± 3.81) | 16.2 (± 2.78) | U = 274.5, Z = −0.737 |

| Neuropsychological Tests (M ± SD) | |||

| MoCA score | 23.56 (± 2.45) | 27.28 (± 1.34) | U = 121.5, Z = −3.71a |

| Short-term memory z-score | −1.04 (± 0.76) | −0.08 (± 0.75) | U = 165, Z = −2.86 |

| Visuo-spatial functions z-score | −0.01 (± 0.5) | 0.65 (± 0.53) | U = 143, Z = −3.29a |

| Attention z-score | −0.77 (± 0.68) | −0.32 (± 0.76) | U = 291, Z = −0.42 |

| Executive functions z-score | −1.22 (± 0.65) | −0.12 (± 0.63) | U = 134, Z = −3.46a |

| Long-term memory z-score | −1.39 (± 0.64) | −0.49 (± 0.59) | U = 163, Z = −2.9 |

| Language functions z-score | −0.67 (± 0.55) | 1.12 (± 0.4) | U = 145, Z = −3.25a |

| Boston naming test score | 25.76 (± 2.95) | 28.56 (± 1.58) | U = 207, Z = −2.05 |

| GDS score | 3.12 (± 3.13) | 0.84 (± 1.14) | U = 226.5, Z = −1.67 |

| FAQcz score | 1.92 (± 2.97) | 0 (± 0) | U = 189.5, Z = −2.39 |

Note: Education Length is quantified as the total number of years of formal education completed. Due to the distribution of most variables not meeting the assumption of normality, non-parametric tests were performed. MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; FAQcz, Functional Activities Questionnaire, Czech version; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

aValues in bold indicate that the difference is significant at the P < 0.05 level after adjusting the variables for the effect of age and applying the Bonferroni correction.

MRI examination

The 3T Siemens Prisma MR scanner (Siemens Corp., Erlangen, Germany) was used for data acquisition at the Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC), Masaryk University in Brno, using the T1 MPRAGE sequence (TR 2.400 ms; TE 2.27 ms; voxel size 0.85 × 0.85 × 0.85 mm; FoV 218 × 218 mm; flip angle 8°; 192 sagittal slices) and multiecho BOLD fMRI sequence for two sessions of the task fMRI [TR 980 ms; TE (14.0, 34.6, 55.3) ms; voxel size 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm; FoV 200 mm; flip angle 50°; 60 axial slices; 500 scans per session; multiband factor 5].

fMRI task

We analysed the performance of the Czech version of the ToSC2 adjusted for fMRI. This was a slightly modified version of the fMRI task used in our previous research, in which the sentences were in Slovak.3 Subjects viewed pictures in conjunction with the sentences from the ToSC on the screen during fMRI and decided whether the sentences matched the pictures by pressing a YES or NO button. The fMRI task consisted of 96 trials, divided into 2 sessions (48 trials each); the duration of the whole fMRI task was 16 min. Canonical and noncanonical word order sentences were used (ratio of use: 1:1). The rate of correct and false statements was 1:1 (48 to 48). All participants were properly instructed and practiced the task before they were scanned. The percentage of correct answers, reflecting accuracy, was our outcome measure.

Data analysis

The fMRI data was preprocessed using the SPM 12 toolbox running under Matlab 2017b (MathWorks, Inc.); this included realignment, multiecho merging based on CNR,26 spatial normalization, and smoothing (5 mm FWHM Gaussian filter). Levels of excessive motion set to the framewise displacement metric exceeded 0.5 mm in more than 20% of the scans in each of the sessions. Two MCI-LB subjects were excluded from analysis due to excessive movements. We then controlled the data for spatial abnormalities (e.g. dropouts) with the Mask Explorer tool.27

We used a mask of the whole striatum based on the structural anatomical striatal atlas28 available within the FSL software package. We used five peak coordinates for the ventral and the dorsal language pathways, according to previously published work,4 see Fig. 2. Spheres with the centroid at the corresponding peak voxel (radius = 6 mm) were created and intersected with the fMRI group mask. The final masks then served as ventral and dorsal language network region of interests (ROIs) and were used in the subsequent analyses.

Figure 2.

Dorsal and ventral language pathways. Dorsal (A) and ventral (B) pathways for language with region of interests (ROIs) that were used for the psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analysis; T1a/p: anterior/posterior superior temporal gyrus; T2a/p: anterior/posterior middle temporal gyrus; FUS: fusiform gyrus; F3orb/tri/op: pars orbitalis/triangularis and opercularis of the inferior frontal gyrus; FOP: deep frontal operculum; PMd, dorsal premotor cortex. Figure was created using BrainNet Viewer, Xia et al. (2013), MNI coordinates for ROIs were adapted from Sauer et al. 2008.

Two task-dependent functional connectivity analyses (from the whole striatum to the rest of brain and in between the ROIs of language areas4) were studied using the psychophysiological interaction method (PPI)29 with age (which differed between both groups) used as a nuisance regressor. We used a general linear model with regressors for PPI interactions for canonical and noncanonical conditions, effects of seed, effects of task conditions (canonical, noncanonical), and nuisance regressors (24 regressors for movement, nuisance regressors for white matter signal and for signal from cerebrospinal fluid). T-tests were used to calculate the differences between MCI-LB and HC. For PPI analyses from the striatum to the whole brain, we reported results with a statistical significance threshold set to P < 0.05 with FWE correction at the cluster level with an initial cutoff of P = 0.001. For PPI analyses between ROIs separated into dorsal and ventral language networks, we reported results with statistical significance threshold set to P < 0.05 with FDR correction. ROIs were selected as spheres with a radius of 6 mm with the first eigenvariate as a representative signal.

Results

Behavioural results

On the behavioural level, the MCI-LB patients had significantly lower total ToSC scores (mean ± sd: 74.7 ± 15.7) in fMRI than HC (mean ± sd: 88.5 ± 9.0), P < 0.001, and the difference was significant for both canonical (MCI-LB-mean ± sd: 82.2 ± 15.6, HC-mean ± sd: 94.0 ± 7.6, P = 0.001) and noncanonical sentences (MCI-LB-mean ± sd: 67.5 ± 18.0, HC-mean ± sd: 82.9 ± 12.7, P < 0.001).

Connectivity results

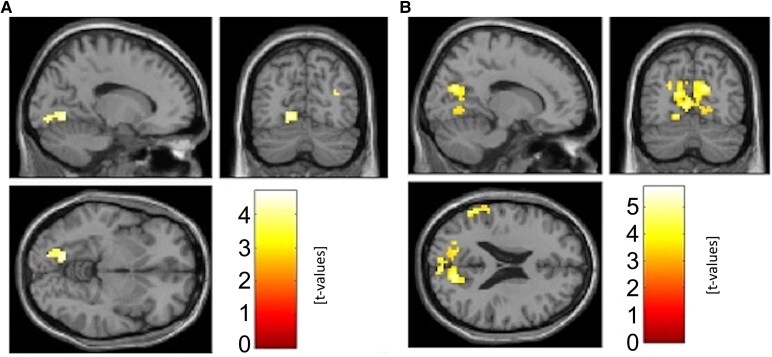

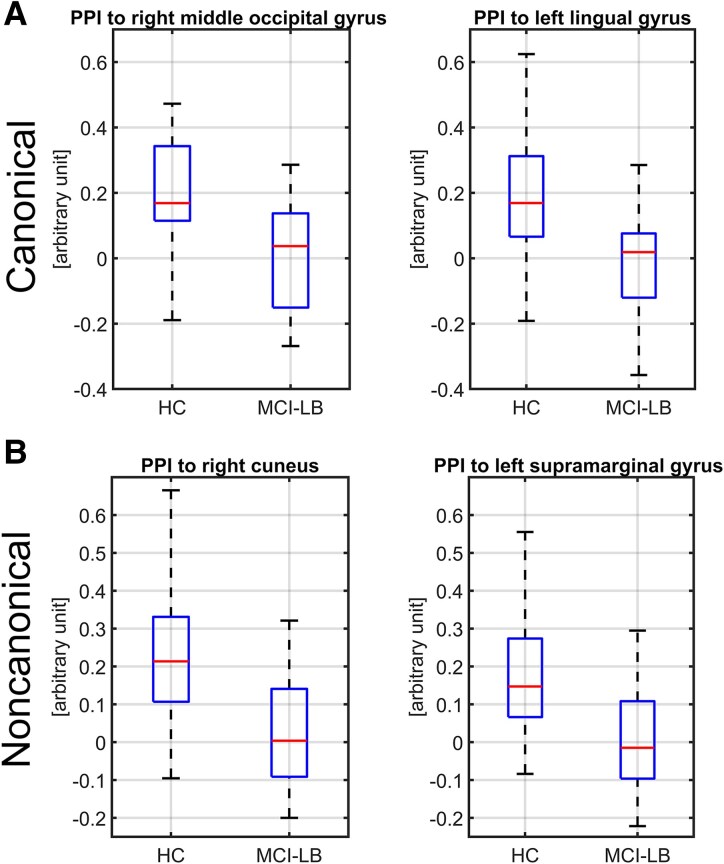

Using PPI from the striatum, we found that there was a statistically significant decrease in connectivity to the cuneus/precuneus/lingual gyrus for both canonical and noncanonical sentences in MCI-LB as compared to HC (the decrease in noncanonical sentences was more prominent) and to the left supramarginal gyrus for noncanonical sentences only, see Fig. 3 and Fig. 4. Second PPI of the language networks showed decreased connectivity in MCI-LB subjects as compared to HC during noncanonical condition between ROIs in the dorsal pathway, see Table 2. For all PPI scores, see Supplementary material.

Figure 3.

Connectivity differences, seed striatum, comparing patients versus healthy controls. Results of the psychophysiological interaction method (PPI) analysis using t-tests comparing patients with mild cognitive impairment with Lewy bodies (MCI-LB, N = 25) versus healthy controls (HC, N = 25), seed striatum, A: canonical B: noncanonical. In both cases were used two sample t-tests with t-values thresholded with P < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Boxplots of the psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analysis, seed striatum. (A) canonical—here difference between groups in connectivity to right middle occipital gyrus has on cluster level inference pFWE = 0.031, and to the left lingual gyrus pFWE = 0.019, (B) noncanonical—here difference in connectivity between groups connectivity to right cuneus has on cluster level inference pFWE < 0.001 and to the left supramarginal gyrus pFWE = 0.007. Difference is computed with two sample t-test on patients with mild cognitive impairment with Lewy bodies (MCI-LB, N = 25) versus healthy controls (HC, N = 25), significant clusters.

Table 2.

PPI significant differences in connectivity in non-canonical condition, the dorsal pathway, statistical significance thresholds of t-tests were set to P < 0.05, FDR corrected

| Sign. diff. in | Connection | HC mean ± std | MCI-LB mean ± std | original P value t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| noncanonical condition | T1p - T1a | 0.223 ± 0.179 | 0.077 ± 0.243 | 0.021 |

| T1a - PMd | 0.175 ± 0.182 | 0.031 ± 0.169 | 0.007 | |

| T1a - F3op | 0.165 ± 0.264 | −0.035 ± 0.179 | 0.004 | |

| FOP - F3op | 0.198 ± 0.202 | 0.016 ± 0.198 | 0.003 | |

| PMd - F3op | 0.264 ± 0.303 | 0.049 ± 0.275 | 0.013 |

T1a/p, anterior/posterior superior temporal gyrus; F3op, pars opercularis of the inferior frontal gyrus; FOP, deep frontal operculum; PMd, dorsal premotor cortex.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess syntactic comprehension deficits in MCI-LB patients and to explore the neural correlates using functional connectivity analysis of the striatum and language networks. Our behavioural results showed disturbed sentence comprehension in MCI-LB patients with altered task-dependent functional connectivity from the striatum to the cuneus/precuneus/lingual gyrus and to the left supramarginal gyrus. We also found decreased connectivity in dorsal language network in MCI-LB patients as compared to HC. Changes in noncanonical sentences were related specifically to the dorsal pathway disturbances.

The cuneus/precuneus/lingual gyrus are posterior cortical regions that seem to be heavily affected in DLB patients, with these regions showing cortical thinning compared to both HC and patients with Alzheimer’s disease.30 Posterior cortical hypometabolism involving the above-mentioned regions and in the supramarginal gyrus was also present in fully blown DLB patients on FDG PET.31,32 These areas showed hypometabolism even in the prodromal stages and this was associated with a higher phenoconversion rate to PD/DLB.33

A meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity in patients with a-synucleinopathy (PD, DLB, multiple system atrophy) showed hypoconnectivity between subcortical regions and the posterior default mode network (precuneus) as compared to HC.34 This is in line with our previous study, where we found decreased resting-state functional connectivity between middle striatum and precuneus in PD, which was negatively correlated with executive functions.35 Functionally posterior cortical regions are connected with visuospatial processing, executive functions, memory, word processing, and phonological processing.36-39 Specifically, the supramarginal gyrus plays an important role in visual word recognition and in phonological decoding, as was seen using transcranial magnetic stimulation.38,39

In our study, reduced connectivity between the striatum and dorsal language pathway regions in MCI-LB were not observed in the whole-brain connectivity analyses, apart from the supramarginal gyrus, which can indeed be considered a dorsal pathway component. One possible explanation is that the strong involvement of occipital and ventral visual association cortices in our visually presented sentence comprehension task may have dominated the connectivity patterns. Prior studies have shown that sentence comprehension tasks involving picture stimuli engage rapidly and extensively visual networks in addition to classical language regions.40,41 This may have made it more difficult to detect subtle decreases between the striatum and dorsal language areas.

Regarding the results of a PPI analysis reviewing task-related changes of specific seeds of the dorsal and ventral language pathways, we found decreased connectivity in our patient group as compared to HC, such that syntactically more complex sentences were connected to disruptions of dorsal pathway connections. This is in line with previous literature linking syntax specifically to this dorsal language pathway. The processing of complex syntax relies on the posterior superior temporal gyrus/sulcus and BA 44/45 via the dorsal pathway, but its engagement may partly reflect increased working memory demands from greater syntactic complexity.4 Other authors42 similarly associated higher working memory loads with the dorsal stream. Interestingly, there is also ontological differentiation: while the ventral pathway is present at birth, the dorsal pathway, critical for processing complex syntax, undergoes prolonged maturation and remains incomplete at age seven.43 In an awake language mapping study, direct subcortical stimulation showed that the dorsal pathways are critical for organizing words in a sequence necessary for sentence generation.44 In fact, these cortico-striatal language pathways are related to complex syntax45 and can dynamically adjust for syntactic complexity (canonical versus noncanonical sentences).46

Specifically, we have seen that connectivity between anterior part of the superior temporal gyrus and the language areas in the frontal lobule (F3op: pars opercularis of the inferior frontal gyrus; PMd: dorsal premotor cortex) was lower in MCI-LB patients than in HC during noncanonical condition. Specific changes in frontotemporal connectivity were described previously in LBDs and might be a promising indicator of cognitive impairment in these a-synucleinopathies.47-49

In our previous study,3 we found that patients with PD without MCI performed worse in sentence comprehension than HC and exhibited increased PPI functional connectivity between the right striatum and the supplementary motor area (SMA), which was related to reduced accuracy in noncanonical sentence comprehension. In comparison to our previous study,3 the current study with cognitively impaired patients reflects the disease stage when connectivity within specific language networks is decreased. Similar changes, from connectivity increases to decreased connectivity, were previously described in both AD50 and PD.51

The study limitations include a relatively small sample size, the lack of indicative biomarkers, the possible role of medications used by participants, and the age difference between the patient group and HC, although age was used as a covariate of no interest in our further data analyses.

In summary, MCI-LB patients demonstrated impaired comprehension of syntactically complex sentences as compared to HC. We identified task-related reduced functional connectivity in these patients within specific subcortical-cortical and language networks compared to HC. We identified distinct alterations in the dorsal pathway that were linked to processing of syntactically complex sentences in MCI-LB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the core facility MAFIL, supported by MEYS CR (LM2023050 Czech-BioImaging), part of the Euro-BioImaging (www.eurobioimaging.eu) ALM and Medical Imaging Node (Brno, CZ), for their support with obtaining scientific data presented in this paper. Graphical abstract was created in BioRender. Novakova, L. (2025): https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/68a84c23123807b3e495c6c4.

Contributor Information

Lubomira Novakova, Applied Neuroscience Research Group, Central European Institute of Technology – CEITEC, Masaryk University, Brno 62500, Czech Republic.

Martin Gajdoš, Applied Neuroscience Research Group, Central European Institute of Technology – CEITEC, Masaryk University, Brno 62500, Czech Republic.

Daniel Carbol, Applied Neuroscience Research Group, Central European Institute of Technology – CEITEC, Masaryk University, Brno 62500, Czech Republic; Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno 62500, Czech Republic.

Irena Rektorova, Applied Neuroscience Research Group, Central European Institute of Technology – CEITEC, Masaryk University, Brno 62500, Czech Republic; First Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine and St. Anne’s University Hospital, Brno 60200, Czech Republic.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain Communications online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (grant NU23J-04-00005) and by an EU Joint Program-Neurodegenerative Disease (JPND) project entitled ‘TACKLing the Challenges of PREsymptomatic Sporadic Dementia (TACKL-PRED),’ project number 8F22005 and by the project A lifetime with language: the nature and ontogeny of linguistic communication, project ID CZ.02.01.01/00/23_025/0008726, that is co-funded by the European Union. Supported by National Institute for Neurology Research (Programme EXCELES, ID Project No. LX22NPO5107, Funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU), and by Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MEYS), Czech National Node to the European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (CZECRIN, LM2023049).

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared with qualified researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. Code used for data analysis is available in the supplementary materials.

References

- 1. Kaan E, Swaab TY. The brain circuitry of syntactic comprehension. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6(8):350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nohová L, Vitásková K, Kršková M, Marková J, Cséfalvay Z. Test porozumění větám (TPVcz): Metodická příručka. Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Novakova L, Gajdos M, Markova J, et al. Language impairment in Parkinson’s disease: FMRI study of sentence Reading comprehension. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1117473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saur D, Kreher BW, Schnell S, et al. Ventral and dorsal pathways for language. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(46):18035–18040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartoň M, Rapcsak SZ, Zvončák V, Mareček R, Cvrček V, Rektorová I. Functional neuroanatomy of Reading in Czech: Evidence of a dual-route processing architecture in a shallow orthography. Front Psychol. 2023;13:1037365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Angwin AJ, Chenery HJ, Copland DA, Murdoch BE, Silburn PA. Summation of semantic priming and complex sentence comprehension in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2005;25(1):78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gross RG, Camp E, McMillan CT, et al. Impairment of script comprehension in Lewy body spectrum disorders. Brain Lang. 2013;125(3):330–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gross RG, McMillan CT, Chandrasekaran K, et al. Sentence processing in Lewy body spectrum disorder: The role of working memory. Brain Cogn. 2012;78(2):85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grossman M, Cooke A, DeVita C, et al. Grammatical and resource components of sentence processing in Parkinson’s disease: An fMRI study. Neurology. 2003;60(5):775–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grossman M, Gross RG, Moore P, et al. Difficulty processing temporary syntactic ambiguities in Lewy body spectrum disorder. Brain Lang. 2012;120(1):52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee C, Grossman M, Morris J, Stern MB, Hurtig HI. Attentional resource and processing speed limitations during sentence processing in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Lang. 2003;85(3):347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Walenski M, Europa E, Caplan D, Thompson CK. Neural networks for sentence comprehension and production: An ALE-based meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40(8):2275–2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilson SM, Dronkers NF, Ogar JM, et al. Neural correlates of syntactic processing in the nonfluent variant of primary progressive aphasia. J Neurosci. 2010;30(50):16845–16854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilson SM, Galantucci S, Tartaglia MC, et al. Syntactic processing Depends on dorsal language tracts. Neuron. 2011;72(2):397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson SM, DeMarco AT, Henry ML, et al. Variable disruption of a syntactic processing network in primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2016;139(11):2994–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheppard SM, Meier EL, Kim KT, et al. Neural correlates of syntactic comprehension: A longitudinal study. Brain Lang. 2022;225:105068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Litvan I, Aarsland D, Adler CH, et al. MDS task force on mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Critical review of PD-MCI. Mov Disord. 2011;26(10):1814–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKeith IG, Ferman TJ, Thomas AJ, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2020;94(17):743–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Novakova L, Gajdos M, Barton M, et al. Striato-cortical functional connectivity changes in mild cognitive impairment with Lewy bodies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2024:121:106031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brabenec L, Klobusiakova P, Simko P, Kostalova M, Mekyska J, Rektorova I. Non-invasive brain stimulation for speech in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Stimul. 2021;14(3):571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Straková E, Věchetová G, Dvořáková Z, Orlíková H, Preiss M. Krátká neuropsychologická baterie (KNB): Manuál. 1st ed. Národní ústav duševního zdraví; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zemanová N, Bezdíček O, Michalec J, et al. Validity study of the Boston naming test Czech version. Cesk Slov Neurol N. 2016;79/112(3):307–316.http://www.csnn.eu/en/czech-slovak-neurology-article/validity-study-of-the-boston-naming-test-czech-version-58260 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bezdíček O, Lukavský J, Preiss M. Functional activities questionnaire, Czech version – a validation study. Cesk Slov Neurol N. 2011;74/107(1):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Poser BA, Versluis MJ, Hoogduin JM, Norris DG. BOLD contrast sensitivity enhancement and artifact reduction with multiecho EPI: Parallel-acquired inhomogeneity-desensitized fMRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(6):1227–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gajdoš M, Mikl M, Mareček R. Mask_explorer: A tool for exploring brain masks in fMRI group analysis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;134:155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Tzimopoulou S, et al. Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: Dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. NeuroImage. 2011;54(1):264–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O’Reilly JX, Woolrich MW, Behrens TEJ, Smith SM, Johansen-Berg H. Tools of the trade: Psychophysiological interactions and functional connectivity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012;7(5):604–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Delli Pizzi S, Franciotti R, Tartaro A, et al. Structural alteration of the dorsal visual network in DLB patients with visual hallucinations: A cortical thickness MRI study. Chen K, ed. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Whitwell JL, Graff-Radford J, Singh TD, et al. 18 F-FDG PET in posterior cortical atrophy and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(4):632–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu J, Ge J, Chen K, et al. Consistent abnormalities in metabolic patterns of Lewy body dementias. Mov Disord. 2022;37(9):1861–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yoon EJ, Lee JY, Kim H, et al. Brain metabolism related to mild cognitive impairment and phenoconversion in patients with isolated REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2022;98(24):e2413–e2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tang S, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. Large-scale network dysfunction in α-synucleinopathy: A meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. eBioMedicine. 2022;77:103915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anderkova L, Barton M, Rektorova I. Striato-cortical connections in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases: Relation to cognition: Cortico-striatal connectivity in PD & AD-MCI. Mov Disord. 2017;32(6):917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kraft A, Grimsen C, Kehrer S, et al. Neurological and neuropsychological characteristics of occipital, occipito-temporal and occipito-parietal infarction. Cortex. 2014;56:38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Romero L, Walsh V, Papagno C. The neural correlates of phonological short-term memory: A repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18(7):1147–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hartwigsen G, Baumgaertner A, Price CJ, Koehnke M, Ulmer S, Siebner HR. Phonological decisions require both the left and right supramarginal gyri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(38):16494–16499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stoeckel C, Gough PM, Watkins KE, Devlin JT. Supramarginal gyrus involvement in visual word recognition. Cortex. 2009;45(9):1091–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Friederici AD. The brain basis of language processing: From structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(4):1357–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dikker S, Rabagliati H, Pylkkänen L. Sensitivity to syntax in visual cortex. Cognition. 2009;110(3):293–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matchin W, Mollasaraei ZK, Bonilha L, et al. Verbal working memory and syntactic comprehension segregate into the dorsal and ventral streams, respectively. Brain Commun. 2024;6(6):fcae449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Friederici AD. Language development and the ontogeny of the dorsal pathway. Front Evol Neurosci. 2012:4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ries SK, Piai V, Perry D, et al. Roles of ventral versus dorsal pathways in language production: An awake language mapping study. Brain Lang. 2019;191:17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Teichmann M, Rosso C, Martini J, et al. A cortical–subcortical syntax pathway linking Broca’s area and the striatum. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(6):2270–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Szalisznyó K, Silverstein D, Teichmann M, Duffau H, Smits A. Cortico-striatal language pathways dynamically adjust for syntactic complexity: A computational study. Brain Lang. 2017;164:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hassan M, Chaton L, Benquet P, et al. Functional connectivity disruptions correlate with cognitive phenotypes in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schumacher J, Peraza LR, Firbank M, et al. Functional connectivity in dementia with Lewy bodies: A within- and between-network analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(3):1118–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kajiyama Y, Hattori N, Nakano T, et al. Decreased frontotemporal connectivity in patients with Parkinson’s disease experiencing face pareidolia. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dickerson BC, Salat DH, Greve DN, et al. Increased hippocampal activation in mild cognitive impairment compared to normal aging and AD. Neurology. 2005;65(3):404–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kojovic M, Kassavetis P, Bologna M, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation follow-up study in early Parkinson’s disease: A decline in compensation with disease progression? Mov Disord. 2015;30(8):1098–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared with qualified researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. Code used for data analysis is available in the supplementary materials.