Abstract

Background

Minimally invasive video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for tracheal cancer is gaining popularity. However, data are limited to single-center reports and short-term outcomes. In this context, we aim to compare short and long-term oncologic outcomes of VATS versus open tracheal cancer resection at the national level.

Methods

We used a national dataset to isolate primary tracheal cancers diagnosed between 2010–2021. Patients were stratified by operative approach into open and VATS resection groups. Cox analysis was used to estimate proportional effects of covariates in unmatched cohorts. We then used propensity score matching to minimize confounding bias from covariates. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were used to estimate 5-year survival.

Results

Of 331 patients undergoing tracheal cancer resection, 147 (44.4%) were started VATS with 5 (3.4%) converting to open. Patients undergoing VATS tracheal resection were similar in age (62.4±14.5 vs. 59.9±14.2 years; P=0.12), race (White =81.0% vs. 84.8%; P=0.32) and Charlson-Deyo comorbidity (index =0, 59.2% vs. 68.5%; P=0.19), but were more likely to be male (57.8% vs. 46.2%; P=0.04) and have positive margins (58.1% vs. 41.0%; P=0.006) compared to open resection. Post-operative length of stay was shorter with VATS (median 2.5 vs. 7.0 days; P<0.001), but this came at the expense of higher rates of positive margins [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) =2.15, P=0.02] and worse median survival (74 vs. 106 months; P<0.001), which persisted after matching (79 vs. 100 months; P=0.01).

Conclusions

In this national observational study, we found that the short-term benefits of thoracoscopic tracheal resection come at the expense of increased positive margins and worse survival. Adoption of this approach for tracheal cancer should be met with caution.

Keywords: Tracheal cancer, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), open surgery

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Analysis of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) versus open surgery for tracheal resection in a national hospital-based dataset revealed that VATS is associated with shorter hospital length of stay. However, this comes at the expense of higher rates of positive margins and worse long-term survival compared to open resection.

What is known and what is new?

• Complete resection with negative margins is known to significantly improve survival for patients with tracheal cancer.

• This comparative effectiveness study further revealed an association between surgical approach, open versus VATS, and these oncologic outcomes.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The VATS approach for tracheal cancer is safe in the short-term but may sacrifice long-term oncologic success. These results should caution against its rapid adoption for the treatment of tracheal cancer.

Introduction

Tracheal cancer is a rare and highly fatal disease with 0.1 new case per 100,000 individuals per year and 5-year survival ranging from 10–50% depending on resectability (1). Due to the rarity of disease, it is poorly studied, and no established staging system exists (2). This leads to minimal guidelines on optimal treatment strategies; however, as with most solid thoracic cancers, surgical resection portends a chance for cure (3,4). The largest series on primary tracheal cancers consisted of 1,379 patients, of which 338 (25%) underwent surgical resection (5). Approximately 80% of tracheal cancers are located within the thoracic cavity and the classical surgical approach is either a right thoracotomy or sternotomy (6-8). With the advent of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for lobectomy, attempts were made at minimally invasive tracheal resection as early as 2005 (9). Since that time, many surgeons have reported their experience with the VATS approach in single-center case reports, showcasing various techniques with or without extracorporeal support, demonstrating operative safety and good short-term outcomes (10,11).

However, the long-term oncologic outcomes of this approach have not been evaluated (11-15). There are examples of other cancers where the minimally invasive approach compromised survival (16). Therefore, given the rarity of tracheal cancer and the overall rapid adoption of minimally invasive approaches in thoracic surgery, it is crucial to explore whether this disease can be managed minimally invasively without jeopardizing long-term oncologic outcomes. Most surgeons have limited experience with tracheal cancer, which combined with limited literature, creates potential for poor outcomes, particularly at low volume centers (17). Due to low incidence of disease, a randomized trial evaluating this approach is unlikely to happen, thus reliance on real-world data is imperative.

In this context, we used a national hospital-based dataset to study the short- and long-term outcomes of minimally invasive tracheal cancer resection. We hypothesized that the minimally invasive approach would be associated with better short-term outcomes and equivalent long-term outcomes. The findings presented herein differ from our hypothesis and should raise caution in the adoption of the minimally invasive approach. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-1445/rc).

Methods

Data source

For this observational comparative effectiveness study, we used data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB; https://ncdbapp.facs.org/puf/). The study proposal was approved and a data-use agreement signed with the NCDB. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The NCDB is a prospective national cancer registry that collects data from more than 1,500 Commission on Cancer accredited centers across the United States, which capture approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed cases of cancer annually and contains more than 30 million patient records. The NCDB includes data regarding patient demographics, diagnosis, tumor characteristics, treatment strategy, and perioperative and long-term outcomes (18).

Patient population

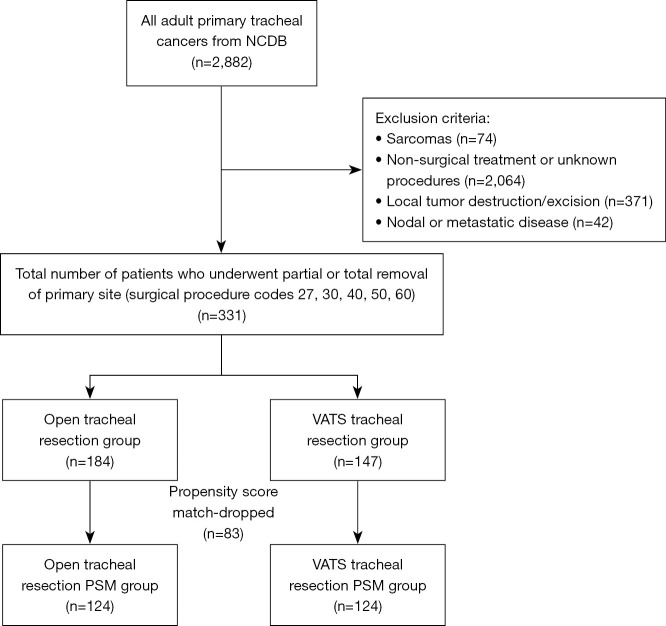

We identified adult patients with primary tracheal cancer using primary site code C339. Operative approach was not recorded prior to 2010, and survival data did not exist for patients diagnosed after 2021, so only patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2021 were included. The histology codes used in this analysis included squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [8052–8075, 8083], adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) [8200] and other [8010–8050, 8082, 8140, 8201–8720]. Patients with sarcoma were excluded as these frequently require more extensive resections (19,20). Only patients who underwent surgical resection with surgical codes 27 (excision), 30 (simple/partial surgical removal of primary site), 40 (total surgical removal of primary site), 50 (debulking surgery), and 60 (radical surgery/en bloc resection) were included in the study; endoscopic excisions and local tumor destruction were excluded. Patients with nodal or metastatic disease, no surgical treatment or unknown surgical treatment were excluded. Patients with incomplete follow-up data were included and censored at the appropriate time in the survival analysis. A consort-type algorithm is shown in Figure 1. This consort does not include bronchial sleeve resections as those patients are in the lung/bronchus participant user file.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram for creation of study cohort. NCDB, National Cancer Database; PSM, propensity score match; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Main exposure and independent variables

The main exposure variable was the surgical approach. Patients were stratified into a minimally invasive VATS group, which included robotic and video-assisted resections, and an open resection group which included transthoracic and transcervical resections. The data source does not provide further classification of open resections, so we could not stratify by type of open surgical incision. Due to a low number of observations in the robotic group, a separate analysis comparing robotic versus VATS was not feasible. Patients who were converted from VATS to open surgery were included using an intent-to-treat analysis.

The NCDB does not specify precise location within the trachea, but it does identify tumor size and invasion into surrounding structures (extension of disease), so these variables were used as proxies to account for location and complexity of the tumor. The extension of disease variable specifies whether the tumor was localized to the trachea (including intra-epithelial/noninvasive and invasive through epithelium but confined to the trachea), invading surrounding connective tissue (including connective tissue surrounding great vessels, phrenic nerves, pre-tracheal fascia, and vagus nerves), or invading surrounding organs (including esophagus, pleura, bronchi, sternum, thymus, or vertebral column). Other independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, facility type (academic vs. other), facility volume (by quintile), histology, and Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index. Any unknown demographic data was placed into either “unknown” or “other” categories and included in the analysis. There is no American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for tracheal cancer in the NCDB, so no stratification of patients by stage was possible. However, as previously mentioned, patients with nodal or metastatic disease were excluded, and tumor size was accounted for in multivariable analyses.

Outcome variables

Short-term outcome variables included 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, unplanned readmission within 30 days, length of stay, and resection margins. Resection margins were categorized as either negative (R0) or positive, which included both microscopically positive (R1) and macroscopically positive (R2) margins. Resection margins are abstracted from the final pathology reports, so no intra-operative frozen section data is available in the NCDB. Our main long-term outcome was overall survival, measured in months from initial diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics for patients who underwent minimally invasive versus open tracheal resection were analyzed using χ2 tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Short-term outcomes were compared between the two groups using χ2 test for 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, 30-day readmission, and R0 resection rates. Medians and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used for tumor size and length of stay as these were not evenly distributed.

Univariate analysis was used to assess overall survival between the two cohorts using Kaplan-Meier analyses with log-rank test. Patients were further stratified by histology, center volume, and year of diagnosis to assess the effect of histology and center experience over time.

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model on the unmatched cohort was used to identify independent associations with overall survival. The model included surgical approach, margin status, age, sex, race, Charlson-Deyo index, facility type, and histology. An interaction term between the approach and surgical margins was used to assess the combined effects of surgical approach and margins.

Another logistic regression specifically for R0 resection margins accounting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbidities, insurance status, facility type, center volume, tumor size, histology, and extension of disease was used to compare probability of achieving an R0 resection based on operative approach across the spectrum of tumor sizes.

Propensity score matching (PSM) was then used to minimize confounding bias. Age, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance status, facility type, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index, and histology were used in a multivariable logistic regression to calculate propensity scores for each patient. Patients in VATS and open surgery groups were matched 1:1 using the nearest neighbor method without replacement and a caliper of 0.02, which was just below 20% of the propensity score standard deviation (21,22). All standardized bias was reduced to |<10%|, indicating balance. The matched cohorts were again compared using the same statistical tests previously listed for short-term and long-term outcomes. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed with log-rank test on matched pairs to compare long-term survival after matching. Additionally, to consider the role of peri-operative deaths in long-term survival, we performed a landmark analysis with time zero set at 3 months and used the propensity matched cohorts to assess long-term survival.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 17.0SE (Stata Corp). All tests were 2-sided using a P value <0.05 for significance. Confidence intervals were reported to 95% confidence level.

Results

Unmatched analysis

Of the 2,882 adult patients diagnosed with tracheal cancer between 2010 and 2021, 2,495 had localized disease that fit histologic inclusion criteria. Of these 1,514 (60.7%) underwent medical management, 478 (19.2%) underwent endoscopic tumor destruction or excision, and 487 (19.5%) underwent surgical resection. However, 156 (6.3%) patients did not have available data on surgical approach, so after meeting all inclusion criteria, the final patient population consisted of 331 patients. Of the 331 patients, 147 (44.4%) were started VATS, with 5 (3.4%) converting to open. The most common histology was SCC in 141 (42.6%) patients. The baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of the VATS and open surgical groups are shown in Table 1. Patients undergoing VATS tracheal resection were similar in terms of age (62.4±14.5 vs. 59.9±14.2 years; P=0.12), race (White =81.0% vs. 84.8%; P=0.32) and Charlson-Deyo comorbidity (index =0 in 59.2% vs. 68.5%; P=0.19), but were more likely to be male (57.8% vs. 46.2%; P=0.04) and have SCC (52.4% vs. 34.8%; P=0.004).

Table 1. Baseline demographics of the overall and matched cohorts in those undergoing thoracoscopic and open tracheal cancer resection.

| Demographics | Overall | Matched | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open surgery (n=184) | VATS (n=147) | P value | Standardized mean difference (%) | Open surgery (n=124) | VATS (n=124) | P value | Standardized mean difference (%) | ||

| Male | 85 (46.2) | 85 (57.8) | 0.04 | 23.4 | 70 (56.5) | 70 (56.5) | >0.99 | 0.0 | |

| Age (years) | 59.9±14.2 | 62.4±14.5 | 0.12 | 17.3 | 61.3±13.8 | 61.4±14.3 | 0.96 | 0.7 | |

| Race | 0.32 | 20.2 | 0.72 | 5.3 | |||||

| White | 156 (84.8) | 119 (81.0) | 101 (81.5) | 107 (86.3) | |||||

| Black | 18 (9.8) | 19 (12.9) | 16 (12.9) | 13 (10.5) | |||||

| Asian | 3 (1.6) | 6 (4.1) | 3 (2.4) | 2 (1.6) | |||||

| Other | 7 (3.8) | 3 (2.0) | 4 (3.2) | 2 (1.6) | |||||

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 9 (4.9) | 7 (4.8) | 0.96 | 0.6 | 8 (6.5) | 6 (4.8) | 0.58 | 7.0 | |

| Charlson-Deyo score | 0.19 | 20.1 | 0.96 | 3.7 | |||||

| 0 | 126 (68.5) | 87 (59.2) | 79 (63.7) | 77 (62.1) | |||||

| 1 | 45 (24.5) | 44 (29.9) | 34 (27.4) | 35 (28.2) | |||||

| 2+ | 13 (7.1) | 16 (10.9) | 11 (8.9) | 12 (9.7) | |||||

| Insurance | 0.50 | 7.0 | 0.72 | 6.3 | |||||

| Private insurance | 78 (42.4) | 55 (37.4) | 49 (39.5) | 49 (39.5) | |||||

| Medicare | 82 (44.6) | 63 (42.9) | 58 (46.8) | 50 (40.3) | |||||

| Medicaid/government | 18 (9.8) | 21 (14.3) | 13 (10.4) | 17 (13.8) | |||||

| Not insured | 5 (2.7) | 7 (4.8) | 3 (2.4) | 7 (5.6) | |||||

| Insurance status unknown | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | |||||

| Income quartiles | 0.76 | – | 0.57 | – | |||||

| <$46,277 | 26 (16.4) | 26 (20.8) | 18 (17.5) | 23 (22.1) | |||||

| $46,277–$57,856 | 32 (20.1) | 26 (20.8) | 18 (17.5) | 21 (20.2) | |||||

| $57,857–$74,062 | 41 (25.8) | 28 (22.4) | 31 (30.1) | 23 (22.1) | |||||

| ≥$74,063 | 60 (37.7) | 45 (36.0) | 36 (35.0) | 37 (35.6) | |||||

| Histology | 0.004 | 27.5 | 0.11 | 3.2 | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 64 (34.8) | 77 (52.4) | 52 (41.9) | 58 (46.8) | |||||

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 77 (41.8) | 41 (27.9) | 52 (41.9) | 37 (29.8) | |||||

| Other | 43 (23.4) | 29 (19.7) | 20 (16.1) | 29 (23.4) | |||||

| Tumor size (mm) | 22 [16–30] | 23.5 [15–35] | 0.52 | 9.6 | 23 [16–32] | 23 [14.5–33.5] | 0.92 | 7.3 | |

| Extension of disease | 0.35 | – | 0.51 | – | |||||

| Localized to trachea | 64 (66.7) | 45 (71.4) | 41 (63.1) | 39 (70.9) | |||||

| Extends to connective tissue | 11 (11.5) | 3 (4.8) | 7 (10.8) | 3 (5.5) | |||||

| Extends to surrounding organs | 21 (21.9) | 15 (23.8) | 17 (26.2) | 13 (23.6) | |||||

| Facility type | 0.10 | 18.4 | 0.60 | 6.6 | |||||

| Academic | 124 (67.4) | 86 (58.5) | 74 (59.7) | 78 (62.9) | |||||

| Other | 60 (32.6) | 61 (41.5) | 50 (40.3) | 46 (37.1) | |||||

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± standard deviation or median [IQR]. IQR, interquartile range; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Short-term outcomes are shown in Table 2. Patients in the VATS group had a shorter median length of stay (2.5 vs. 7 days; P<0.001). There was no difference in 30-day mortality (5.4% vs. 4.3%, P=0.65), 90-day mortality (10.2% vs. 7.6%, P=0.41), or readmission rates (2.7% vs. 4.3%; P=0.43).

Table 2. Short-term outcomes before and after PSM in those undergoing thoracoscopic and open tracheal cancer resection.

| Outcome | Before PSM | After PSM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open surgery | VATS | P value | Open surgery | VATS | P value | ||

| 30-day mortality | 8 (4.3) | 8 (5.4) | 0.65 | 6 (4.8) | 6 (4.8) | >0.99 | |

| 90-day mortality | 14 (7.6) | 15 (10.2) | 0.41 | 10 (8.1) | 13 (10.5) | 0.51 | |

| Resection margins | 0.006 | 0.09 | |||||

| Positive | 68 (41.0) | 61 (58.1) | 49 (44.5) | 52 (56.5) | |||

| Negative | 98 (59.0) | 44 (41.9) | 61 (55.5) | 40 (43.5) | |||

| Length of stay (days) | 7 [4–10] | 2.5 [0–6] | <0.001 | 7 [4–10] | 2 [0–6] | <0.001 | |

| Readmission within 30 days | 8 (4.3) | 4 (2.7) | 0.43 | 4 (3.2) | 4 (3.2) | >0.99 | |

Data are presented as n (%) or median [IQR]. IQR, interquartile range; PSM, propensity score matching; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

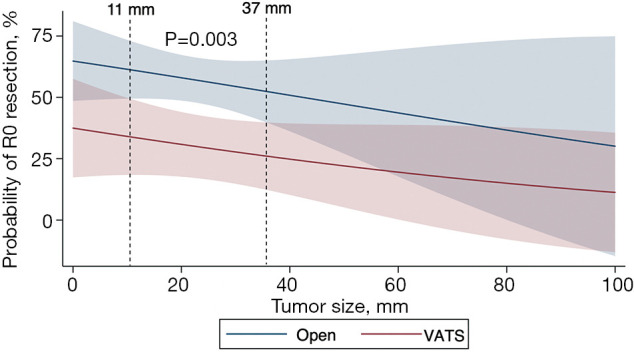

Resection margins were more likely to be positive in the VATS group (58.1% vs. 41.0%; P=0.006). After fitting a logistic regression model for R0 resection accounting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbidities, insurance status, operative approach, tumor size, tumor extension, histology, facility type, and facility volume, open tracheal resection had an adjusted odds ratio of 2.15 (P=0.02) for R0 resection. Using this logistic regression model, Figure 2 shows that the adjusted probability of an R0 resection is inversely proportional to tumor size for both approaches; however, the open approach is associated with higher probability of R0 resection across all tumor sizes particularly for cancers measuring 1.1–3.7 cm (P=0.003), which encompasses the majority of tumors (58.3%). Tumors smaller than 1.1 cm trended toward higher R0 resection with the open approach compared to the VATS approach, but this difference was not statistically significant likely due to low sample size (n=28) for this size range. The probability of an R0 resection was <50% for tumors larger than 4.0 cm regardless of approach.

Figure 2.

Adjusted probability of achieving negative resection margins stratified by approach across tracheal tumor size. This multivariable model adjusts for age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbidities, insurance status, facility type, center volume, tumor size, histology, and extension of disease. R0: negative resection margin. VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

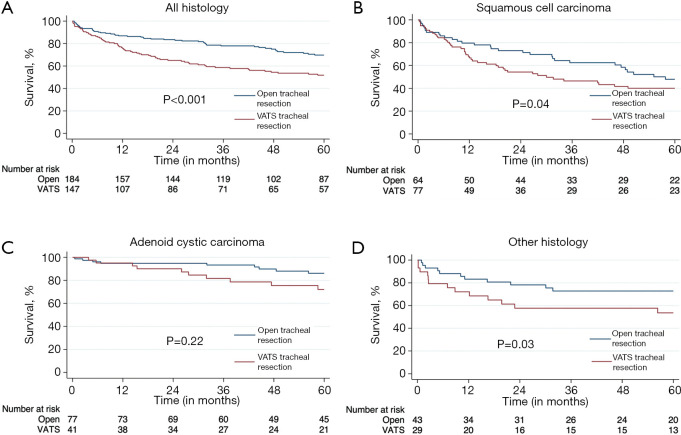

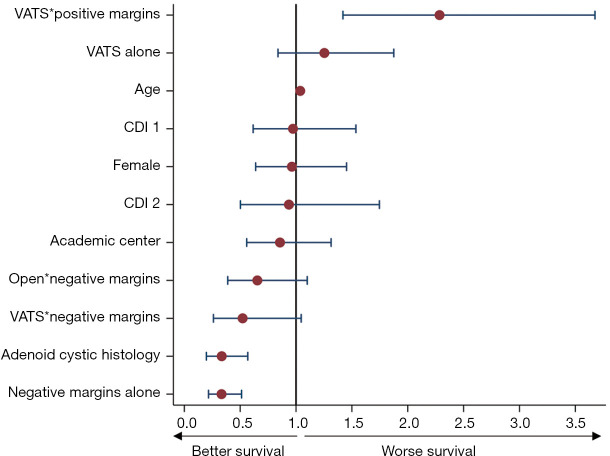

Five-year Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for the overall cohort and individual histologies is shown in Figure 3. The associated hazard function plot of the overall cohort is shown in Figure S1. The VATS group was associated with worse survival compared to open resection in the overall cohort (median survival 74 vs. 106 months; P<0.001) and in the SCC and other histology cohorts. ACC survival curves appear to separate after one year, with the open approach also doing better, but this did not reach statistical significance. In the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, R0 resection [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) =0.33; P<0.001] and adenoid cystic histology (aHR =0.33; P<0.001) were associated with improved survival. VATS resection with positive margins demonstrated worse survival (P=0.001), whereas both VATS and open resections with negative margins demonstrated better survival, but these were not statistically significant. A full comparison can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Open versus minimally invasive tracheal resection Kaplan-Meier survival curves. (A) All histology. (B) Squamous cell carcinoma. (C) Adenoid cystic carcinoma. (D) Other histology. VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Figure 4.

Cox proportional hazards model in the unmatched cohort. *, interaction term. CDI, Charlson-Deyo index; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

When comparing high- to low-volume centers by overall tracheal resection caseload, patients undergoing tracheal resection at a high-volume hospital generally do better, particularly if done with an open approach (Figure S2). Additionally, the proportion of cases performed VATS over time were similar year to year without a notable trend. There was no trend to indicate improved survival with increased experience over the study period.

Propensity score matched analysis

After PSM, 124 pairs were created. Figure S3 shows a bihistogram comparing propensity scores between groups before and after matching. Figure S4 shows standardized mean differences of all covariates before and after matching. Both groups were similar in all measured confounders as shown in Table 1. Short-term outcomes after PSM are included in Table 2 for easy comparison to unmatched data. Median length of stay was still shorter in the VATS group (2.5 vs. 7 days; P<0.001), but there was no difference in readmission, 30-day (4.8% vs. 4.8%, P>0.99) or 90-day mortality (8.1% vs. 10.5%; P=0.51).

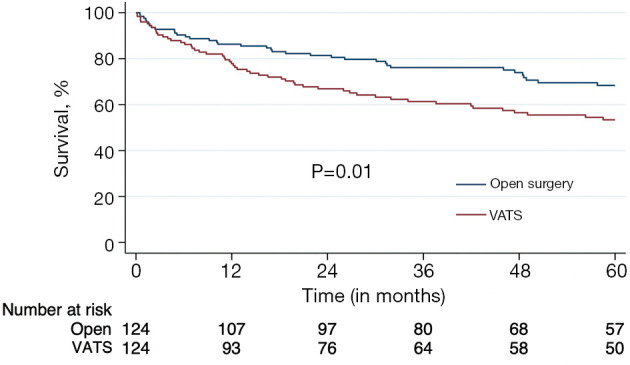

Long-term outcomes in the PSM groups were compared using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. After matching, the VATS approach continued to be associated with worse overall survival (median =79 vs. 100 months; P=0.01) compared to the matched open tracheal resection group as shown in Figure 5. Landmark analysis results to account for peri-operative deaths within 3 months were qualitatively similar. Five-year survival in the landmark analysis was 72.7% for open surgery and 59.1% for VATS (P=0.009).

Figure 5.

Propensity score matched Kaplan-Meier survival curve. VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Discussion

In this national observational study comparing minimally invasive thoracoscopic tracheal cancer resection to open resection we found that while the VATS approach was associated with shorter hospital length of stay and similar short-term morbidity and mortality, this came at the expense of higher rates of positive margins and worse overall survival. Minimally invasive surgery is gaining popularity within thoracic surgery, and tracheal cancer is no exception (23). Given the rarity of this disease, it is difficult to study and only a small proportion (~20%) of patients underwent surgery. Of those, over 40% underwent VATS tracheal resections, so it is vital that we ensure safe and effective surgery.

The VATS approach, as expected, is technically safe and had some short-term advantages. The most pronounced benefit was in length of stay (2.5 vs. 7 days). Short-term mortality and readmission were similar. However, the short-term benefits of the VATS approach came at the expense of worse oncologic outcomes, including a lower probability of R0 resection and worse long-term survival. This may be seen as a parallel to prior studies on minimally invasive resection of gynecologic cervical cancer, which revealed greater recurrence rates with minimally invasive surgery as compared to open surgery (16). In that prior study, the cause of increased recurrence was unclear, but it was postulated that this may be due to tumor spillage or spread via CO2 insufflation. Although tracheal cancer and cervical cancer are different diseases, they are both most commonly SCC. In our study, margins appear to be a significant driving factor.

On initial analysis, the median survival was longer in the open surgery group (106 vs. 74 months). Based on our Cox proportional hazards analysis, positive margins appear to be a driving factor, and we found that patients undergoing VATS are more likely to end up with positive margins (58.1% vs. 41.0%). The higher rate of positive margins and resulting worse survival may be attributed to several potential technical reasons.

In every tracheal resection, the cardinal rule of achieving a tension-free anastomosis is broken. The surgeon’s judgement in avoiding excessive tension is crucial to avoiding complications, such as anastomotic dehiscence (24). Intraoperatively, the surgeon judges tension by re-approximating the edges of the trachea and “feeling” how much force is required. This may be misleading when using VATS instruments. A small amount of tension on a long shaft to a fulcrum will falsely exaggerate the force transferred to a surgeon’s hand. While an experienced VATS surgeon may be able to appropriately assess tension, this may be difficult to judge due to the rarity of the disease and the feared complication of tracheal dehiscence. In the open approach there is no false exaggeration of this force, and it is easier to judge true tension. This false tension may prompt surgeons to resect less trachea or accept a positive margin to avoid “excessive” tension on the anastomosis. If excessive tension is perceived, a re-resection of a positive margin may not be advised. Adjuvant therapy is then used for those accepted margins where necessary, but the benefit of adding adjuvant therapy has been questioned and is unlikely to make up for a suboptimal resection (25,26). In the future, further evidence on the efficacy and safety of tracheal reconstruction could allow for the resection of longer segments of trachea and thus increase probability of obtaining negative margins regardless of surgical approach (27). Recently, cryopreserved aortic allografts have been used for tracheal replacement, mainly at experienced centers (28,29). However, these materials and techniques come with their own risks and are not frequently used at the current time.

Another potential reason for increased rates of positive margins could be the type of resection completed. For the purposes of this study, we included all patients undergoing surgical resection whether partial or complete, so it is possible that minimally invasive included a wedge-shaped or “partial” resection which would be more likely to have positive margins. Unfortunately, the NCDB does not provide some of these more granular operative details or reasons for operative choice. However, both groups had similar tumor sizes, no nodal or metastatic disease and similar extension of disease. Therefore, it is unlikely that surgeons attempting resection via a minimally invasive approach went in with the intention of incompletely resecting the tumor and leaving positive margins. Rather, it is more likely that they intended to resect the entire tumor but realized intra-operatively that they could not achieve a “tension-free” anastomosis and subsequently decided to accept a positive margin or perform a partial resection/debulking. Regardless, there is certainly room for further institutional studies where surgeons could indicate what operation they intended to perform, what operation they actually performed, and what the barriers to achieving this were.

Additionally, as previously alluded to, larger tumors have a lower probability of achieving an R0 resection with both approaches, but particularly with the VATS approach. We analyzed the continuum of tumor size and found that between 1.1 and 3.7 cm, the open approach had much higher adjusted rates of negative margins. Tumors greater than 4 cm are less likely to yield a negative margin regardless of approach, which is in line with the basic surgical principle of allowable tracheal resection length (24,25). A tracheal cancer that is smaller than 1 cm may be appropriate for VATS, but the open approach still trended toward a higher adjusted probability of R0 resection at this tumor size, so the data needed to come to this conclusion is limited. Therefore, the tracheal cancer patient should be offered the surgical resection that will ensure an R0 resection from the outset, which in this study and others, independently influences survival. A shorter hospital stay, although appealing, should not compromise the oncologic indication of the operation.

Another important aspect to note in this study is histology. We specifically removed any patients with sarcomas from the analysis as these are rare, rarely resectable, and when resectable, require complex en-bloc resections and carry a significant negative prognostic value, which we believed would have confounded our results (30). It is known that ACC is associated with better survival compared to SCC (31,32) and our initial cohort had a higher percentage of SCC patients in the VATS group so this was factored into our analysis. Before PSM, survival analyses were stratified by histology. A survival advantage was noted with open surgery for all histologies except ACC. Despite failing to reach statistical significance, the ACC Kaplan-Meier curve still trended toward improved survival with open surgery, so whether or not the two approaches are equivalent or if our sample size was too small, is unclear. After PSM, there was no difference in histology between groups and open surgery was still associated with improved survival.

Another possible cause of the higher mortality seen in the VATS group could be that there were more operative complications, such as dehiscence or leakage, that were not captured in this database. However, the short-term outcomes, such as readmission, 30-day, and 90-day mortality would have reflected this; yet these short-term outcomes were similar between the two groups. Prior studies have shown that most complications, such as dehiscence, occur within 8 days of surgery (33). If patients had a clinically significant complication within the first 8 days after surgery they would, at minimum, require readmission. Additionally, major dehiscences are associated with high short-term mortality. As shown in Figure S1, the hazard rate at different time points revealed a peak at about 1-year after diagnosis, which is more likely to represent deaths from disease rather than peri-operative complications and mortality. Finally, our landmark analysis accounted for deaths within 3 months and still showed that survival was greater in the open surgery cohort.

Another important point of discussion is location of these tumors within the trachea. Unfortunately, the NCDB does not provide specific tumor location within the trachea, so the open group in this study likely includes transcervical resections (i.e. cervical tracheal cancers) and open transthoracic resections (i.e. distal/thoracic tracheal cancers) while the VATS group likely only includes transthoracic resections. However, epidemiological data have shown that the vast majority of malignant tracheal tumors, regardless of histology, are located in the distal intra-thoracic portion (7). While tumor location may influence survival, prior studies have shown that resectability and survival are largely dependent on nodal involvement and metastatic spread (34-36). By design, our study excluded patients with nodal or metastatic disease from the analysis to rule out this potential influence. Additionally, tumor size and extension of disease are important prognostic factors for survival, so we incorporated these variables into our adjusted analyses as well. Theoretically, if a tumor was located in a more complex or difficult location within the trachea, we would assume that the surgeon would opt for the surgical approach that would allow for this more complex resection. In most instances, this would be an open approach. If open procedures were being done on more complex tumors or locations, that would likely increase the probability of positive margins, higher short-term mortality and worse long-term outcomes, which is the opposite of what we found. With that said, we believe our findings remain clinically meaningful but still concede that future institutional studies with more robust data on tumor location would be beneficial to confirm them.

This study has several other limitations. First, as an observational retrospective study, it is subject to confounding and selection bias. For example, some patients had a resection, but did not have data on surgical approach, so they did not meet inclusion criteria for the study. This further limited our sample size and could potentially introduce bias if these patients fell in one surgical approach group more often than the other. However, this is an uncommon cancer, and the VATS approach is becoming more common, so it is difficult to study in a prospective and timely manner outside of a large retrospective study such as this. Second, there were only 5 cases of robotic resection, so it was not possible to further compare surgical approaches within the VATS group. Whether the robotic approach is associated with better outcomes remains unknown. Newer robotic platforms support tactile feedback, and tension may be better judged, but there is no experience with this as of yet. Third, we do not have data on intra-operative frozen sections or length of resected trachea, so it is unclear if surgeons are electing to accept positive margins due to reaching maximum tracheal resection length or if there are other factors at play. We also do not have data on whether extracorporeal support was used for the VATS resections or not, which might alter outcomes. Finally, we did not assess the role of adjuvant radiation therapy for positive margins as prior studies have questioned its role, so we do not believe this would contribute meaningfully to our analysis (2,25,37). Notwithstanding these limitations, we believe our results are relevant and important for all thoracic surgeons to consider when choosing a surgical approach for tracheal cancer.

Conclusions

Tracheal cancer is a complex disease, and surgery is the cornerstone of therapy. Although the minimally invasive video-assisted thoracoscopic approach is described as safe with short-term benefits, we found that it was associated with higher rates of positive margins and worse 5-year survival even after stratified analyses, multivariable logistic regression, and PSM. Our study provides new data, revealing a significant survival advantage with open surgery. While acknowledging the limitations of this retrospective study, VATS for tracheal cancer resection should be approached with caution.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-1445/rc

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-1445/coif). Z.M.A. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease from December 2023 to November 2025. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Shah P, Kela K, Hegde UP. Tracheal cancer epidemiology and survival trends: A SEER database analysis. J Clin Oncol 2024;42:e20078. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piórek A, Płużański A, Teterycz P, et al. Do We Need TNM for Tracheal Cancers? Analysis of a Large Retrospective Series of Tracheal Tumors. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:1665. 10.3390/cancers14071665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilssen Y, Solberg S, Brustugun OT, et al. Tracheal cancer: a rare and deadly but potentially curable disease that also affects younger people. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2023;64:ezad244. 10.1093/ejcts/ezad244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazama K, Miyoshi S, Akashi A, et al. Clinicopathological investigation of 20 cases of primary tracheal cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003;23:1-5. 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00728-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benissan-Messan DZ, Merritt RE, Bazan JG, et al. National Utilization of Surgery and Outcomes for Primary Tracheal Cancer in the United States. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;110:1012-22. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.03.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He J, Yang C, Yang H, et al. Resection and reconstruction via median sternotomy incision for tracheal tumors. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2022;11:600-6. 10.21037/tlcr-22-177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Q, Xue K, Wu Y, et al. Primary malignant tumors of the trachea: a retrospective analysis of the clinical data of 79 patients treated in a single center. Front Oncol 2025;15:1568589. 10.3389/fonc.2025.1568589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rea F, Zuin A. Tracheal resection and reconstruction for malignant disease. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S148-52. 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.02.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakanishi K, Kuruma T. Video-assisted thoracic tracheoplasty for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the mediastinal trachea. Surgery 2005;137:250-2. 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Dai J, Li J, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic hilar and pericardial release for long-segment tracheal resections. J Thorac Dis 2022;14:3061-5. 10.21037/jtd-21-1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Ai Q, Liang H, et al. Nonintubated Robotic-assisted Thoracic Surgery for Tracheal/Airway Resection and Reconstruction: Technique Description and Preliminary Results. Ann Surg 2022;275:e534-6. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Liu J, He J, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery resection and reconstruction of thoracic trachea in the management of a tracheal neoplasm. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:600-7. 10.21037/jtd.2016.01.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Wang W, Jiang L, et al. Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery Resection and Reconstruction of Carina and Trachea for Malignant or Benign Disease in 12 Patients: Three Centers' Experience in China. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:295-303. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.01.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonie SJ, Ch'ng S, Alam NZ, et al. Minimally Invasive Tracheal Resection: Cervical Approach Plus Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:2336-9. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.02.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li ZH, Dong B, Wu CL, et al. Case Report: ECMO-Assisted Uniportal Thoracoscopic Tracheal Tumor Resection and Tracheoplasty: A New Breakthrough Method. Front Surg 2022;9:859432. 10.3389/fsurg.2022.859432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally Invasive versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1895-904. 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanifer BP, Andrei AC, Liu M, et al. Short-Term Outcomes of Tracheal Resection in The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:1612-8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The American College of Surgeons. National Cancer Database. 2021. Available online: https://ncdbapp.facs.org/puf/

- 19.Gaissert HA, Grillo HC, Shadmehr MB, et al. Uncommon primary tracheal tumors. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:268-72; discussion 272-3. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.01.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turbendian H, Seastedt KP, Shavladze N, et al. Extended resection of sarcomas involving the mediastinum: a 15-year experience†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:829-34. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat 2011;10:150-61. 10.1002/pst.433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lunt M. Selecting an appropriate caliper can be essential for achieving good balance with propensity score matching. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:226-35. 10.1093/aje/kwt212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong MKH, Sit AKY, Au TWK. Minimally invasive thoracic surgery: beyond surgical access. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:S1884-91. 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grillo HC. Surgery of the trachea and bronchi. Lewiston, NY, USA: BC Decker; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaissert HA, Honings J, Gokhale M. Treatment of tracheal tumors. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;21:290-5. 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webb BD, Walsh GL, Roberts DB, et al. Primary tracheal malignant neoplasms: the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center experience. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202:237-46. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shu C, Liu YJ, Zheng KF, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Tracheobronchial Tumors. Cancer Med 2025;14:e70893. 10.1002/cam4.70893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinod E, Radu DM, Onorati I, et al. Tracheobronchial Replacement: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg 2025;160:912-9. 10.1001/jamasurg.2025.1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinod E, Chouahnia K, Radu DM, et al. Feasibility of Bioengineered Tracheal and Bronchial Reconstruction Using Stented Aortic Matrices. JAMA 2018;319:2212-22. 10.1001/jama.2018.4653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butkus JM, Kramer M, Eichorn D, et al. Unresectable Primary Tracheal Synovial Sarcoma. Ear Nose Throat J 2025;104:93S-5S. 10.1177/01455613221113815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaissert HA, Grillo HC, Shadmehr MB, et al. Long-term survival after resection of primary adenoid cystic and squamous cell carcinoma of the trachea and carina. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:1889-96; discussion 1896-7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.05.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urdaneta AI, Yu JB, Wilson LD. Population based cancer registry analysis of primary tracheal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 2011;34:32-7. 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181cae8ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shuman EA, Kim YJ, Rodman J, et al. Timing of Complications in Open Airway Reconstruction. Laryngoscope 2024;134:3527-31. 10.1002/lary.31362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright CD, Grillo HC, Wain JC, et al. Anastomotic complications after tracheal resection: prognostic factors and management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;128:731-9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherani K, Vakil A, Dodhia C, et al. Malignant tracheal tumors: a review of current diagnostic and management strategies. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2015;21:322-6. 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Tan F, Wang Y, et al. Clinical characteristics, surgical treatments, prognosis, and prognostic factors of primary tracheal cancer patients: 20-year data of the National Cancer Center, China. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2022;11:735-43. 10.21037/tlcr-22-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang CJ, Shah SA, Ramakrishnan D, et al. Impact of Positive Margins and Radiation After Tracheal Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Resection on Survival. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;109:1026-32. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.08.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]