Abstract

Metalloenzymes serve as inspiration for novel molecular catalysts and model systems. While chemists have designed complexes that mimic these biological catalysts, synthetic complexes often do not recapitulate the reactivity of the native enzymes. We hypothesise that the secondary coordination sphere surrounding the metal centre, which is indispensable for enzymatic activity, is the crucial component missing in biomimetic catalysts. To address this issue, we have designed and synthesised hangman dipyrrin complexes that emulate both the primary and secondary coordination sphere of the fungal enzyme polysaccharide monooxygenase by including a pendant phenol above the metal centre. Here, we report the synthesis of Zn(ii), Pd(ii), Co(iii), Ga(iii), Fe(iii), and Mn(iii) complexes, which are characterised by NMR spectroscopy, UV-vis absorption, X-ray crystallography, and cyclic voltammetry. Complementary density functional theory calculations were performed to support spin state assignments. The square planar and octahedral complexes exhibit atropisomerism, which arises from the 2-substituent on the meso aryl ring. This attribute ensures a precise, rigid position of the pendant phenol, akin to a protein active site, which can be controlled by leveraging differences in atropisomer solubility in the case of the Pd(ii) phenol complex. We envision that this hangman ligand architecture will overcome the limitations of previous biomimetic catalysts.

We have developed hangman dipyrrin complexes with secondary sphere residues that perform proton transfer and bind small molecules. Atropisomerism confers rigidity, mimicking the stable positioning of amino acid side chains in protein active sites.

Introduction

The development of biomimetic metal complexes that serve as structural and functional mimics of metalloenzyme active sites is a long-standing subfield of bioinorganic chemistry.1–4 The primary focus of this research has been to synthesise molecules that emulate the primary coordination sphere of the metallocofactor. One aspect of these model systems that is often overlooked is the secondary coordination sphere surrounding the protein active site, which plays a crucial role in reactivity.5 Metallocofactors often have peripheral amino acid residues that provide hydrogen bonding contacts to stabilise metal-bound ligands. One example is myoglobin, where a conserved histidine above the haem cofactor enables O2 binding at the Fe(ii) centre.6 Similar O2 stabilisation is observed in haem nitric oxide/oxygen binding proteins (H-NOX) that selectively bind O2 rather than NO.7 In these oxygen-sensing proteins, a distal hydrogen bonding network is present above the haem cofactor, where a tyrosine residue is necessary and sufficient to form the Fe(ii)–O2 adduct.8 The role of the secondary coordination sphere in proteins extends beyond hydrogen bonding stabilisation of metal-bound ligands. These functions range from dictating substrate specificity and regioselectivity to regulating electron transfer and allostery.9–11

One example that highlights the role of the secondary coordination sphere in protein function is the blue copper site in azurin and plastocyanin.12,13 A methionine residue above the copper distorts the geometry of the metal so the copper centre can adopt a geometry that is intermediate to square planar Cu(ii) and tetrahedral Cu(i), reducing the reorganisation energy associated with electron transfer.14 Synthetic inorganic chemists have designed biomimetic complexes to model the copper site of these proteins.15,16 Recently, Olshansky and co-workers have synthesised copper complexes that undergo dynamic conformational changes,17 which give rise to very rapid electron transfer rates as a consequence of the low reorganisation energy.18

The inclusion of secondary sphere residues in small molecule complexes leverages the hangman effect,19–22 which tunes the pKa of the metal-bound oxygen intermediate and increases the effective proton concentration. “Hangman” complexes evolved from extensive studies of cofacial or “pacman” porphyrins by Collman, Chang, and Nocera.21,22 Mechanistic studies of electrocatalytic O2 reduction revealed that two redox-active metal centres were not necessary to reduce O2 to H2O. Instead, the second metal tuned the pKa of the metal-bound O2 intermediate. Consequently, the second porphyrin could be replaced with an acid/base group above the metal to stabilise the M–O2 species and tune its pKa, while also serving as a proton relay to facilitate proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET). The hangman architecture was pioneered by Chang23 and later popularised by Nocera and co-workers,24 who have reported numerous studies on hangman porphyrins and corroles for electrochemical O2 reduction, H2O oxidation, H+ reduction, and CO2 reduction.19,25,26

Recently, there has been a surge in the development of transition metal complexes that include peripheral, secondary-sphere residues to enable or enhance reactivity.27–30 Motivated by these examples, we have developed a hangman dipyrrin ligand platform that incorporates a pendant phenol moiety (Fig. 1). This bioinspired architecture emulates the active site of polysaccharide monooxygenase (PMO): a mononuclear copper enzyme that oxidises the glycosidic bond in recalcitrant polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose, chitin).31 Fungal PMOs have a conserved tyrosine residue in the secondary coordination sphere, which is proposed to stabilise an O2 adduct at the copper centre, tune the electronic structure of the metal, and facilitate O2 reduction.32 We have selected dipyrrin as the ligand platform to model the PMO active site (Fig. 1). Dipyrrins, or half-porphyrins, can bind main group elements, d-block metals, and f-block metals.33–36 The synthesis of dipyrrins is more facile than analogous porphyrins, requiring fewer synthetic steps and less chromatography with higher product yields. Dipyrrins offer more versatility than porphyrins, enabling substrates to bind at either an equatorial or axial position, whereas porphyrins are restricted to axial substrate binding. The dipyrrin ligand can be substituted at the α, β, and meso positions to tune the steric and electronic properties of the ligand. Since dipyrrins are not macrocyclic, the primary coordination sphere is readily diversified, enabling the isolation of both homoleptic and heteroleptic complexes. Together, these properties make dipyrrin a versatile ligand for catalyst development.34,35

Fig. 1. The active site of fungal PMOs has a conserved axial tyrosine residue that is predicted to stabilise an O2 adduct (PDB ID: 5UFV). The primary coordination sphere is highlighted in cyan, and the secondary coordination sphere is highlighted in yellow. The hangman dipyrrin platform emulates the PMO active site by incorporating phenol moieties above and below the metal centre, mimicking the tyrosine and threonine residues in the secondary coordination sphere.

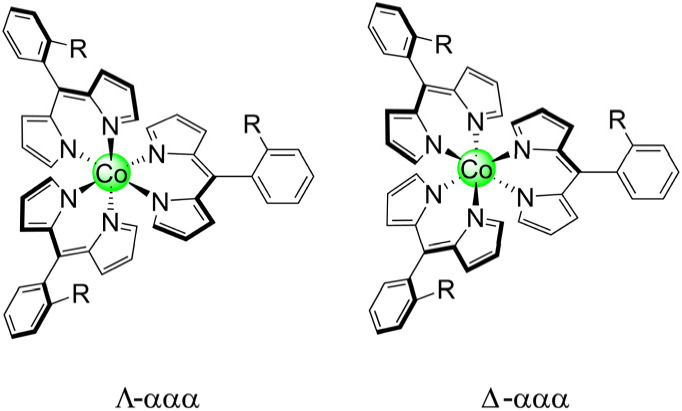

Here, we report the first examples of hangman dipyrrin complexes. While cofacial or “pacman” dipyrrins have been reported,37,38 the hangman approach has not yet been integrated with the dipyrrin ligand platform. We emulate the active site of fungal PMOs by incorporating a pendant phenol above the metal centre as a model for the axial tyrosine residue (Chart 1). Ligands with a variety of hanging groups and their corresponding diamagnetic Zn(ii), Pd(ii), Co(iii), and Ga(iii) complexes have been synthesised and characterised by NMR spectroscopy, UV-vis absorption, X-ray crystallography, and cyclic voltammetry. We have extended these methods to prepare paramagnetic Mn(iii) and Fe(iii) derivatives, where only two published examples of Mn(iii) dipyrrins exist.39,40 Both the square planar and octahedral complexes exhibit atropisomerism, which arises from the 2-substituent on the meso aryl ring. While this phenomenon is well-known for porphyrins and corroles,41–43 atropisomerism in dipyrrins has rarely been studied, with only one reported example.44 The restricted rotation of the phenol enables precise positioning of the hanging group, akin to the rigidity and preorganisation of a protein active site. The Pd-22 complex serves as a faithful structural mimic of the PMO active site (Fig. 1). Moreover, the presence of a hanging group, while non-coordinating and remote from the metal centre, has an impact on the chemistry and properties of the complex. We envision that this hangman dipyrrin architecture will overcome the limitations of previous biomimetic catalysts, conferring reactivity that is comparable to native enzymes.

Chart 1. The hangman dipyrrin ligands (1–3) and corresponding homoleptic and heteroleptic metal complexes reported in this study (R = –OMe, –OH, and –H).

Results and discussion

Ligand synthesis

The synthesis of the hangman dipyrrin ligands is outlined in Scheme 1. First, the TFA-catalysed condensation of 2-nitrobenzaldehyde and pyrrole furnished dipyrromethane 4, as previously reported.45 DDQ oxidation46 provided dipyrrin 5, which serves as a control ligand that bears a 2-substituent, but lacks an aryl hanging moiety. The nitro group in 4 was reduced using H2 with Pd/C as the catalyst,47 producing the amino derivative 6. Amide bond formation between 6 and m-anisic acid was first attempted using 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) and dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC),48 but the hangman dipyrromethane (7) was obtained in only 22% yield. The yield of 7 was significantly increased to 92% when HATU was used as the peptide coupling agent with triethylamine (TEA) as the base.49 Using this method, the phenyl derivative 8 was obtained from benzoic acid in 88% yield. DDQ oxidation46 of 7 and 8 resulted in dipyrrin ligands 1 and 3, respectively, in moderate yield (∼62%). In contrast to most meso-unsubstituted dipyrrins,33 the isolation of these hangman dipyrrins is quite facile due to the presence of the meso-aryl substituent. Deprotection of the methyl ether in 1 was first attempted using aluminium trichloride (AlCl3) as the Lewis acid,50 but only starting material was recovered. Since peripheral functionalisation reactions are generally more successful on metal complexes than the ligand itself,51 the AlCl3 deprotection reaction was repeated with a metal complex, but the methoxy group was still unreactive. Demethylation was achieved using boron tribromide (BBr3) as the Lewis acid52 to afford 2 in 78% yield.

Scheme 1. Synthetic route to the hangman dipyrrin ligands 1–3 and the 2-nitrophenyl derivative (5).

Ligands 1, 2, 3, and 5 are bright yellow in solution due to a characteristic absorption peak at ∼430 nm (Fig. S1). This feature reflects a π → π* transition centred on the conjugated dipyrrin core.53 Ligands 1, 2, and 3 also have a band at 268 nm, which is ∼2/3 the intensity of the main transition. This secondary peak is due to a π → π* transition centred on the aryl 2′ substituent (i.e., the aryl amide). This assignment is substantiated by the absence of a similar feature for 5. We note that 5 has weak bands at 310 and 258 nm that are ∼25% the intensity of the main transition. Interestingly, both 1 and 2 have a distinct shoulder at ∼300 nm that is likely due to the presence of the hanging group, which lowers the symmetry of the aryl amide. Indeed, the symmetric phenyl derivative 3 lacks this shoulder.

Tetrahedral Zn(ii) complexes

The zinc complexes Zn-12, Zn-22, and Zn-32 were synthesised by adapting literature methods that used zinc acetate as the metal source with either (1) chloroform and methanol as the solvent and TEA as the base,54 or (2) pyridine as the solvent and base.55 Purification on silica, Florisil, or basic alumina resulted in degradation of the complex, leading only to the isolation of the free-base ligand. Initially, a small, pipette-scale Florisil column of Zn-32 appeared promising, resulting in the isolation of pure product. However, a preparative scale purification of Zn-32 resulted in multiple fractions that contained the free-base ligand, indicative of degradation on the stationary phase (Fig. S2). Similar behaviour has been observed with zinc corroles, where an acidic stationary phase resulted in demetallation.56 Since these Zn(ii) dipyrrin complexes could not be chromatographed, they were purified by recrystallisation or selective precipitation. First, crude Zn-12 was rinsed with methanol to remove zinc salts, and the remaining solid was then washed with hexanes. Recrystallisation by slow evaporation from CH2Cl2/hexanes gave Zn-12 as red/green dichroic block crystals in 44% isolated yield. Methanol and hexanes were used to precipitate Zn-32, furnishing the product in 87% yield. Crude Zn-22 was first recrystallised via vapour diffusion, using ethanol as the solvent and cyclohexane as the anti-solvent, to give Zn-22 as orange prisms that were coated in yellow/orange deposits, which were washed away with hexanes and chloroform to give the product in 11% isolated yield. Analysis of these complexes by GC-MS and MALDI mass spectrometry only showed peaks corresponding to the ligand. Consequently, liquid injection field desorption ionisation (LIFDI) mass spectrometry was utilised to characterise these compounds. This soft ionisation technique enabled detection of the intact metal complexes.

The recrystallisation methods outlined above yielded diffraction-quality crystals for Zn-12 and Zn-22 (Table S1). Both complexes exhibit a distorted tetrahedral geometry (Fig. 2), which is quantified using τ4 (derived from the N–Zn–N bond angles). This parameter describes the geometric range of four-coordinate complexes from square planar (τ4 = 0) to tetrahedral (τ4 = 1). Zn-12 and Zn-22 exhibit τ4 values of 0.85 and 0.86, respectively, which is consistent with other zinc dipyrrins.57 The angle between the two mean 11-atom dipyrrin planes is 89.89° and 89.38° for Zn-12 and Zn-22, respectively. For Zn-12, the Zn–N bonds range from 1.987 Å to 1.995 Å, with an average length of 1.991 Å and standard deviation of 0.005 Å. Similarly, these bond lengths vary from 1.967 Å to 1.980 Å with an average length of 1.974 Å and standard deviation of 0.008 Å for Zn-22. While these results are consistent with previous reports,57 it is interesting to note that the Zn–N bonds are shorter in Zn-22, which bears the hanging phenol group.

Fig. 2. Solid-state structures of (a) Zn-12 and (b) Zn-22. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

The main transition in the UV-vis absorption spectra of Zn-12, Zn-22, and Zn-32 is observed at 488 nm (ε = 105 M−1 cm−1) with a prominent shoulder at 469 nm (Fig. S3a). Additional, weaker features are observed at 355 nm and ∼270 nm. Given their closed-shell nature, these complexes are emissive, exhibiting weak green fluorescence (Fig. S3b). All three compounds exhibit an emission maximum around 508 nm (807 cm−1 Stokes shift). The fluorescence quantum yields (ϕf) in toluene are 1.9%, 1.0%, and 1.7% for Zn-12, Zn-22, and Zn-32, respectively, which are similar to other zinc dipyrrin complexes.54

Since Zn(ii) is not redox active, analysis of Zn-12, Zn-22, and Zn-32 by cyclic voltammetry (CV) provides a benchmark for the electrochemical properties of the dipyrrin ligands (Fig. 3). This data will help assign the redox properties (i.e., ligand-based vs. metal-based) of hangman dipyrrin complexes with other metals (vide infra). Both Zn-12 and Zn-32 exhibit sequential one-electron reductions of the dipyrrin ligands that are separated by ∼225 mV and are fully reversible. This observation is consistent with other reports of homoleptic zinc dipyrrins, where the separation between reduction peaks ranges from ∼170 mV to ∼380 mV.58,59 In the case of the phenol analogue Zn-22, this separation is reduced to 166 mV and the reductions become irreversible. This illustrates that the hanging group, while remote from the metal centre (Fig. 3), has a significant effect on the redox properties of the complex. All three complexes exhibit a single, irreversible oxidation at +0.74 V (vs. Fc+/Fc). We note that the current for the oxidation process is approximately twice that of the individual reduction waves. Based on this data, we conclude that the two dipyrrin ligands are reduced sequentially, whereas both dipyrrin units are oxidised simultaneously. Overall, these CVs are consistent with other zinc dipyrrin complexes.58,59

Fig. 3. Cyclic voltammograms of Zn-12 ( ), Zn-22 (

), Zn-22 ( ), and Zn-32 (

), and Zn-32 ( ) in THF with 0.1 M [TBA][PF6] recorded at 100 mV s−1 under an argon atmosphere. Additional features (*) are observed due to incomplete reversibility of some electrochemical processes.

) in THF with 0.1 M [TBA][PF6] recorded at 100 mV s−1 under an argon atmosphere. Additional features (*) are observed due to incomplete reversibility of some electrochemical processes.

Square planar Pd(ii) complexes

The initial synthesis of Pd-12 and Pd-32 utilised a procedure analogous to that of the Zn(ii) complexes (Method 1, see SI). However, this resulted in low yields: 42% for Pd-12 and 5% for Pd-32. In an effort to increase the yield, microwave irradiation was utilised, which has been successful for the preparation of Pd porphyrin and chlorin complexes in nearly quantitative yield.60 When 3 was treated with Pd(acac)2 in pyridine under microwave irradiation at 180 °C, only a trace of the complex was observed. A significant increase in product formation was achieved when treating the ligand with 1 equivalent of Pd(OAc)2 and 25 equivalents of TEA at room temperature (Method 2, see SI): 85% yield for Pd-12, 69% yield for Pd-22, and 54% yield for Pd-32. Unlike the Zn analogues, the Pd complexes could be purified by silica chromatography.

The 1H NMR spectra of Pd-12, Pd-22, and Pd-32 are more complicated than expected, displaying two sets of signals for each chemically distinct proton. A comparison of the amide and methoxy regions of the 1H NMR spectra for 1 and Pd-12 is shown in Fig. 4. We attribute this complex pattern to the presence of atropisomers in the sample, where the hanging group could reside above (α) or below (β) the equatorial plane. The presence of the aryl amide at the 2-position of the meso substituent imposes a barrier to ring rotation, resulting in the formation of distinct atropisomers. This phenomenon has been observed for porphyrins41,42 and corroles43 with ortho-substituted meso-aryl substituents. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of atropisomerism for square planar dipyrrin complexes. This feature is intrinsic when an ortho substituent is present on a meso aryl ring. The presence of the two atropisomers (αα and αβ) is confirmed by analytical HPLC (Fig. S4). While the two atropisomers are expected to be formed in a 1 : 1 statistical mixture, we note the peak intensity in the NMR spectrum and HPLC chromatogram does not reflect an equal amount of the αα and αβ atropisomers. We attribute this deviation to the greater polarity of αα-Pd-12 and the observed streakiness on the silica column, which leads to incomplete isolation of this species.

Fig. 4. Illustration of the double peak pattern observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of Pd-12 ( ) compared to 1 (

) compared to 1 ( ), depicting the (a) amide and (b) methoxy regions of the spectra. (c) The double peaks are due to the presence of both the αα and αβ atropisomers in the sample, where α and β indicate that the aryl amide is above or below the tetrapyrrole plane, respectively. The intensity of the αβ peaks are uniformly higher, reflecting the slight enrichment of this species as a result of incomplete isolation of the αα atropisomer due to its higher polarity and streakiness on the column. The peak integrations and assignments are consistent with HPLC analysis (Fig. S4).

), depicting the (a) amide and (b) methoxy regions of the spectra. (c) The double peaks are due to the presence of both the αα and αβ atropisomers in the sample, where α and β indicate that the aryl amide is above or below the tetrapyrrole plane, respectively. The intensity of the αβ peaks are uniformly higher, reflecting the slight enrichment of this species as a result of incomplete isolation of the αα atropisomer due to its higher polarity and streakiness on the column. The peak integrations and assignments are consistent with HPLC analysis (Fig. S4).

In the case of Pd-22, the atropisomers were enriched by exploiting differences in solubility. As isolated, the atropisomer ratio was 66 : 34 (αα : αβ), as determined by 1H NMR peak integrations (Fig. 5a) and confirmed by analytical HPLC (66 : 34 ratio, Fig. 5b). The addition of diethyl ether resulted in significant separation of the two atropisomers. The soluble material is primarily αβ and the insoluble solid is mostly αα. After repeating this washing process multiple times, the isomers are substantially enriched, where the αα : αβ ratio is 27 : 73 for the ether-soluble material (Fig. 5c) and 82 : 18 for the ether-insoluble material (Fig. 5d). Interestingly, isomerisation was observed for both of the enriched samples (in d6-DMSO solution), converging to a 68 : 32 mixture for the sample in Fig. 5c and 67 : 33 for the sample in Fig. 5d after 2 months (Fig. S5). This ratio is nearly identical to the as-isolated ratio of 66 : 34. A freshly prepared sample of the αβ enriched complex reached a similar ratio (66 : 34) after only 5 hours (Fig. S6).

Fig. 5. Illustration of the aromatic region of the 1H NMR spectrum of Pd-22 in d6-DMSO. As isolated, the αα to αβ ratio is 66 : 34, as measured by both (a) 1H NMR peak integrations and (b) analytical HPLC. The ether-soluble fraction (c) is significantly enriched in the αβ atropisomer, while the insoluble material (d) is primarily the αα atropisomer.

The atropisomers of Pd-12 could not be separated in an analogous manner as Pd-22. This disparity is a consequence of the pendant hanging group, where the polar phenol enables greater differentiation in the solubility of the two atropisomers. The hydrogen bonding ability of Pd-22 is readily visualised by diffusion ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) NMR, which reflects the difference in the hydrodynamic diameter (as measured by the diffusion coefficients) of the two atropisomers. In the case of Pd-12, the diffusion coefficients of the two atropisomers are nearly identical: 2.65 × 10−10 and 2.94 × 10−10 m2 s−1 for αα and αβ, respectively (Fig. S7). Conversely, Pd-22 exhibits a more significant difference in the diffusion coefficients: 1.38 × 10−10vs. 3.24 × 10−10 m2 s−1 for αα and αβ, respectively (Fig. S8). When the dipole moments of the polar phenol hanging group are oriented on the same face of the complex, the effect is additive, resulting in greater polarity of the αα atropisomer relative to the αβ derivative. We hypothesise that this attribute, in conjunction with differences in hydrogen bonding ability, enables substantial enrichment of the Pd-22 atropisomers on the basis of solubility alone. While the atropisomers of Pd-12 could not be separated by differential solubility, slow elution and careful fractionation during chromatography resulted in atropisomer enrichment. Early eluting fractions were enriched in the αβ isomer (αα to αβ ratio of 31 : 69), whereas later eluting fractions were enriched in the αα isomer (66 : 34) (Fig. S9). Interestingly, a sample with an αα : αβ ratio of 76 : 24 in d6-DMSO isomerised after 5 hours, forming an equilibrium mixture of 67 : 33, which is identical to that of Pd-22 (Fig. S10).

The formation of a convergent 65 : 35 equilibrium mixture of atropisomers for both Pd-12 and Pd-22 (in a solution of d6-DMSO) is unexpected. For porphyrins and corroles, ambient temperatures do not provide the requisite thermal energy to overcome the rotational barrier imposed by the 2-substituent on the meso aryl ring, resulting in the formation of atropisomers.41–43 Our results with the Pd(ii) dipyrrin complexes are consistent with these observations. Indeed, if the two species were rapidly interconverting on the NMR timescale, we would expect to see one set of signals. Consequently, another mechanism must be operative to cause a redistribution of the atropisomer ratio. Since DMSO is a coordinating solvent, we hypothesised that nucleophilic attack of a solvent molecule at the Pd(ii) centre would result in the dissociation of one pyrrole unit of the dipyrrin ligand. The monodentate dipyrrin can then rotate, thereby scrambling the orientation of the hanging group relative to the other dipyrrin ligand. Upon rebinding of the dipyrrin as a bidentate ligand, which is driven by the chelate effect, the atropisomer distribution is modified. To test this, we performed a control experiment in a non-coordinating solvent. Surprisingly, samples of Pd-12 enriched in either the αβ (31 : 69) or αα atropisomer (66 : 34) undergo isomerisation in CDCl3 over 24 hours (Fig. S11 and S12), resulting in equilibrium mixtures of 50 : 50 and 52 : 48, respectively. Consequently, we conclude that this isomerisation reflects the inherent lability of the dipyrrin ligand in these Pd(ii) complexes. While the ligand substitution/dissociation process is kinetically slow (i.e., hours), it is accelerated in d6-DMSO, suggestive of a solvent-mediated mechanism. The different equilibrium ratios in CDCl3 (1 : 1) versus d6-DMSO (2 : 1 αα to αβ) is not unexpected, as changes in the experimental conditions will modulate the thermodynamics of the system.

Diffraction quality crystals of Pd-22 were obtained by slow evaporation of DMSO over ∼4 months (Fig. 6). The αβ atropisomer preferentially crystallised, exhibiting square planar geometry (τ4 = 0.00). The two dipyrrin ligands are not coplanar, sitting above and below the N4 plane to avoid steric repulsion between the α-dipyrrin hydrogen atoms. The angle between the two pyrrole units (defined by the mean 5-atom planes) of the dipyrrin ligand is 30.7°. This value is comparable to other homoleptic Pd(ii) dipyrrins, which exhibit an angle of 34.1° between the pyrrole units.61 For Pd-22, the Pd–N bonds range from 2.007 Å to 2.015 Å, with an average length of 2.011 Å and standard deviation of 0.005 Å. Interestingly, a DMSO solvent molecule forms a hydrogen bond with the phenol oxygen, resulting in an O⋯O distance of 2.654 Å. This observation illustrates that the hanging group can participate in hydrogen bonding, similar to secondary sphere residues in a metalloprotein active site.

Fig. 6. Solid-state structure of Pd-22. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms bound to the carbon and nitrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

To explore additional hydrogen bonding interactions and the acid/base properties of the hanging group, Pd-12 and Pd-22 were treated with tetrabutylammonium acetate ([TBA][OAc]). Upon the addition of excess [TBA][OAc] (12.9 equivalents) to Pd-22, the phenol protons at 9.64 ppm disappeared with concomitant formation of acetic acid (Fig. S13), indicative of deprotonation. Indeed, the acetic acid peak at 1.73 ppm has been observed for the deprotonation of aryl tetrazolones with [TBA][OAc].62 Additionally, the signals of the amide protons (9.88 and 9.37 ppm) broadened, where the average full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the two amide peaks increased from 4.0 Hz to 7.8 Hz. Interestingly, treatment of Pd-12 with excess [TBA][OAc] (9.5 equivalents) resulted in a substantial broadening of the amide proton signals, increasing the FWHM from 4.0 Hz to 32 Hz (Fig. S14). Such peak broadening has been previously observed upon the addition of anions to aryl amides.63 These experiments demonstrate that the phenol moiety, but not the amide, is deprotonated by acetate. The broadening of the amide proton signals suggests hydrogen bonding interactions with the acetate anion. We hypothesise that the smaller effect observed for Pd-22 may be due to the bulky [TBA]+ cation or the negative charge of the phenolate. The significant broadening of the amide proton signals in Pd-12 illustrates that the amide group can also participate in non-covalent, supramolecular interactions. Together, these experiments suggest that the entire meso-aryl amide moiety, not just the hanging group, contributes to the secondary sphere of the metal centre.

Our synthetic method can be adapted to the synthesis of heteroleptic complexes. Pd-1-acac was prepared by treating a solution of 1 in MeOH/CHCl3 and TEA with excess Pd(acac)2 under refluxing conditions. It was found that the purification of Pd-1-acac by column chromatography resulted in the co-elution of residual Pd(acac)2, despite varying the mobile phase composition. The complex was fully purified by recrystallisation via slow evaporation from CH2Cl2/hexanes and isolated in 41% yield. These diffraction-quality crystals yielded X-ray structures of Pd-1-acac, and two polymorphs were observed (Fig. 7a and S15). The primary difference is the position of the methoxy group above the Pd(ii) centre. As expected, both polymorphs exhibit square planar geometry (τ4 = 0.03). The Pd–N bonds range from 1.988 Å to 1.996 Å, with an average length of 1.992 Å (standard deviation of 0.003 Å), which are remarkably similar to the Zn–N bonds of Zn-12. The Pd–O bonds are slightly longer, ranging from 1.997 Å to 2.003 Å, with an average length of 2.000 Å (standard deviation of 0.002 Å). The dipyrrin and acac ligands are not quite coplanar, exhibiting angles of 13.18° and 17.24° between the mean 11-atom dipyrrin plane and the mean 7-atom acac plane for the two polymorphs.

Fig. 7. (a) Solid-state structure of Pd-1-acac (polymorph 2, Table S1). Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity. (b) Cyclic voltammograms of Pd-12 ( ), and Pd-1-acac (

), and Pd-1-acac ( ) in THF with 0.1 M [TBA][PF6] recorded at 100 mV s−1 under an argon atmosphere. Additional features (*) are observed due to incomplete reversibility of some electrochemical processes.

) in THF with 0.1 M [TBA][PF6] recorded at 100 mV s−1 under an argon atmosphere. Additional features (*) are observed due to incomplete reversibility of some electrochemical processes.

The main transition in the UV-vis absorption spectra of Pd-12, Pd-22, and Pd-32 is observed at 484 nm (ε = 104 M−1 cm−1), which is blue shifted relative to the Zn analogues (488 nm). Additional, weaker features are observed at ∼385 nm and ∼265 nm (Fig. S16). These spectra are similar to those of previously reported palladium dipyrrins.61,64 The heteroleptic complex Pd-1-acac exhibits an absorption maximum at 505 nm, which is red-shifted by 846 cm−1 relative to Pd-12 (Fig. S16). While some Pd dipyrrins exhibit phosphorescence,61 none of the hangman complexes were emissive under aerobic or anaerobic conditions at room temperature.

Similar to the Zn derivatives, the CVs of Pd-12, Pd-22 and Pd-32 (Fig. 7b and S17) exhibit two sequential one-electron reductions of the dipyrrin ligands at −1.65 V and −1.86 V (vs. Fc+/Fc), and this separation is identical to that of the Zn complexes. Unlike the Zn complexes, the second reduction for the Pd analogues is quasi-reversible. Pd-12, Pd-22, and Pd-32 undergo an irreversible oxidation at +0.65 V, which exhibits a current that is approximately twice that of the reduction waves, suggestive of a two-electron process. This ligand oxidation represents a ∼90 mV cathodic shift relative to the Zn derivatives. Pd-1-acac exhibits a single dipyrrin reduction at −1.76 V, which is comparable to the midpoint potential of the two sequential reductions in the homoleptic complexes (Fig. S17). An additional reduction is observed at −2.43 V. Given the similarity of this feature to that of Pd(acac)2 at −2.26 V (Fig. S18), we attribute this process to reduction of the acac ligand. An irreversible oxidation is observed at +0.87 V for Pd-1-acac. Similar to the homoleptic complexes, the current of this oxidation is nearly twice the reduction current. This result suggests that both the dipyrrin and acac ligands are oxidised simultaneously. This assignment is consistent with the CV of Pd(acac)2, which exhibits ligand oxidation at +1.11 V with an onset potential of +0.86 V. While there are two publications on the electrochemical characterisation of homoleptic palladium dipyrrin complexes, neither study reports features in the negative potential window.65,66 For a Pd(ii) dipyrrin complex with a meso triphenylamine substituent, the authors only report an irreversible oxidation at +1.70 V vs. SCE (1.30 V vs. Fc+/Fc) in DCM.65 The other study on Pd(ii) dipyrrins with meso ferrocenyl substituents simply characterised the Fe(iii)/Fe(ii) couple of the ligand.66 As a result, our study represents the first comprehensive electrochemical characterisation of Pd(ii) dipyrrin complexes.

Octahedral Co(iii) complexes

Initial attempts to synthesise Co-13 utilised 5 equivalents of Co(OAc)2 relative to 1 in pyridine. After purification by silica chromatography, a complicated 1H spectrum was obtained, suggestive of multiple products. Indeed, it has previously been reported than an excess of the metal source can result in the formation of mixed-ligand heteroleptic complexes.67 The reaction conditions were refined, using 3.3 equivalents of 1 relative to Co(OAc)2 to afford Co-13 in 74% yield.

After purification by silica chromatography, the 1H NMR spectrum still exhibited a complex pattern of four signals for each chemically distinct proton: three equal intensity peaks and a fourth peak with about half the intensity of the other three (Fig. 8). DOSY NMR was utilised to determine that all of the observed signals were due to a molecule with the same diffusion constant, and by extension, molecular weight (Fig. S19). This indicates that the complex pattern results from isomerism rather than the presence of an impurity. Initially, we hypothesised that this isomerism arose from the positioning of the methoxy group, which could reside at either the 3 or 5 position of the aryl amide if ring rotation were hindered. Indeed, porphyrins with substituents at the 3-position of the meso-aryl groups exhibit restricted ring rotation, albeit with a lower barrier to rotation compared to substitution at the 2-position.68 To test this hypothesis, Co-33 without the hanging group was synthesised following the same procedure for Co-13 and the product was isolated in 84% yield. Surprisingly, Co-33 also exhibited the same four-signal pattern in the 1H NMR spectrum (Fig. S20). DOSY NMR confirmed that the signals arose from a species with a singular molecular weight (Fig. S21). Next, we hypothesised that this isomerism was due to different orientations of the aryl amide, which could, in principle, be oriented toward or away from the Co centre. To test this, Co-53 was synthesised analogous to Co-13 and was obtained in 79% yield. This control molecule reduces the aryl amide to a nitro group. However, the same four-line pattern in the 1H NMR spectrum was observed for Co-53 (Fig. S22), indicating that this isomerism is an inherent consequence of the 2-substituent on the meso-aryl ring (Chart 2a). Restricted ring rotation has been invoked for ortho-substituted meso-aryl boron dipyrrin (BODIPY) complexes to rationalise the complexity of the 19F NMR spectra.69,70 The first observation of atropisomerism in tris homoleptic dipyrrin complexes was recently reported for aluminium derivatives.44 However, this isomerism was not fully characterised and the species were not assigned by 1H NMR. To the best of our knowledge, these cobalt complexes represent the second example of atropisomerism in tris homoleptic dipyrrin complexes.

Fig. 8. Illustration of the peak pattern observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of Co-13, depicting the (a) methoxy and (b) amide regions of the spectrum. For each chemically distinct proton, there are three equal intensity peaks, with a fourth signal that has half the intensity of the other three. (c) Analytical HPLC analysis illustrating the presence of two atropisomers in the sample. The 1H NMR peak integrations are consistent with the HPLC analysis, indicating a roughly 75 : 25 mixture of the two species.

Chart 2. Representation of the ααα and ααβ atropisomers for (a) Co-53 and (b) Co-13.

To describe this isomerism, the aryl amide could be oriented up (α) or down (β) relative to the pseudo C3 axis of the complex, resulting in 23 or 8 possible configurations. Six of these options are equivalent representations (i.e., rotations) that correspond to the ααβ atropisomer, while the remaining two options reflect the ααα atropisomer. Consequently, the predicted statistical product distribution is 75% ααβ and 25% ααα. For the ααβ atropisomer, each dipyrrin ligand is chemically distinct (Chart 2), resulting in a set of three, equal intensity peaks for each dipyrrin proton. For the ααα atropisomer, all three dipyrrin units are equivalent, resulting in a single signal for each unique dipyrrin proton. Based on the integration of the 1H NMR signals, the ααβ and ααα atropisomers are observed in an 85 to 15 ratio (ααβ to ααα), consistent with the statistical expectation. As in the case of the Pd complexes, the slight deviation from the idealised ratio is due to the greater polarity of ααα-Co-13, which streaks on the silica column and leads to incomplete isolation of this species. The product distribution is confirmed by analytical HPLC (Fig. 8c), which indicates a 76 to 24 ratio of the atropisomers (ααβ to ααα) based on peak integrations.

Complex Co-13 was crystallised by vapour diffusion from THF and hexanes to produce iridescent, dichroic green/red crystals. Alternatively, crystals can be obtained via vapour diffusion from isopropanol/benzene and cyclohexane as the antisolvent. The crystallisation process modulates the atropisomer distribution. Analysis of the Co-33 crystals and mother liquor by 1H NMR indicates that the peak intensity of the set of three signals (ααβ) uniformly changes relative to the fourth signal (ααα), providing further confirmation that these signals arise from the same species (Fig. S23). This result indicates that the ratio of ααα-Co-33 and ααβ-Co-33 atropisomers can be modulated under different experimental conditions, akin to Pd-22.

In another attempt to modify the atropisomer distribution, a sample of Co-13 was heated. Greater thermal energy would increase the rotation of the meso aryl rings, overcoming the barrier imposed by the 2-aryl amide. This interconversion process was measured by variable temperature (VT) 1H NMR spectroscopy. Upon heating, it is expected that rotation of the meso-aryl substituents will increase, resulting in a single signal for each chemically distinct proton (in contrast to the four signals observed at room temperature). Over the 23–100 °C range, coalescence of the methoxy signals was observed for Co-13 (Fig. S24). Moderate shifts were also observed in the aromatic region, indicating convergence of some signals due to meso-ring rotation (Fig. S25). Complete coalescence of the signals was not observed at 100 °C, likely due to the bulkiness of the aryl amide. We hypothesised that clearer shifts and signal coalescence would be observed for Co-53 due to the smaller nitro group. However, only nominal convergence of the β-proton signals was observed up to 70 °C (Fig. S26).

It should be noted that these homoleptic Co(iii) complexes are chiral, akin to tris bipyridine (bpy) and ethylenediamine (en) complexes. This is in addition to the inherent atropisomerism of these complexes. Thus, each atropisomer represents a mixture of Δ and Λ stereoisomers (Chart 3). To measure the distribution of enantiomers, Co-13 was examined by polarimetry, and the sample exhibited a 0.00° rotation of the incident light, indicating that the sample is a racemic mixture.

Chart 3. Stereoisomers of tris homoleptic ortho-substituted meso-aryl dipyrrins.

Diffraction-quality crystals of Co-13 yielded a solid-state structure (Fig. 9). The cubic lattice of the crystal results in substantial voids spaces (∼17% of the unit cell volume), which contain disordered solvent molecules that could not be adequately modelled. Solvent masking resulted in the removal of 744 electrons per unit cell. Initial refinement of the structure as a single atropisomer yielded poor quality statistics (e.g., wR2 = 0.2182 for all data). The inclusion of a disorder model to account for the up (α) and down (β) orientation of the aryl amide significantly improved the model, decreasing wR2 = 0.1376 for all data. In this way, we were able to model both ααα-Co-13 and ααβ-Co-13. The disorder model was refined as a free variable, resulting in an approximate ratio ααα to ααβ ratio of 85 to 15. This deviation from the experimental product distribution is attributed to the removal of a considerable amount electron density from the lattice, which likely includes the disordered aryl amide. The Co–N bonds range from 1.938 Å to 1.941 Å, with an average length of 1.940 Å (standard deviation of 0.002 Å). This is consistent with other meso-aryl cobalt dipyrrins, which exhibit an average Co–N bond length of 1.945 Å.67 The angle between each of the mean 11-atom dipyrrin planes is 82.78°, which is somewhat smaller than the 89.89° separation between the dipyrrin planes of Zn-12.

Fig. 9. Solid-state structure of Co-13, illustrating the (a) ααα and (b) ααβ atropisomers obtained from the disorder model. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 30% probability level. Hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

The UV-vis absorption spectra of Co-13, Co-33, and Co-53 (Fig. S27) exhibit well-resolved peaks at 511 and 472 nm (1617 cm−1 separation), which is distinct from the Zn and Pd analogues. A broad feature is also observed at 402 nm that has about a third the intensity of the main transitions. This feature is significantly red-shifted relative to the corresponding bands for the Pd (388 nm) and Zn (355 nm) complexes. Both Co-13 and Co-33 exhibit a prominent band at 269 nm, which we attribute to the aryl amide. This assignment is corroborated by the absence of this feature in Co-53. The meta-methoxy group in Co-13 reduces the symmetry of the aryl amide, resulting in a weak shoulder at 305 nm, similar to the other metal complexes of ligands 1 and 2. We note that the band at 269 nm has a higher extinction coefficient for the Co complexes than the Pd and Zn analogues, reflecting an increase in the number of dipyrrin ligands.

Octahedral M(III) complexes (M = Mn, Fe, Ga)

After refining the synthesis of Co-13, we extended this method to the preparation of additional octahedral complexes for period 4 M(III) ions. These complexes were synthesised under refluxing conditions in either pyridine or MeOH/CHCl3 and the products were isolated in moderate yield: Ga-13 (65%), Fe-13 (57%), and Mn-13 (75%). These complexes were purified by silica chromatography and subsequently recrystallised via vapour diffusion from THF and cyclohexane. Unsurprisingly, Ga-13 exhibited a similar 1H NMR splitting pattern to Co-13, which reflects ααβ and ααα atropisomers. Similar to Pd-12, silica chromatography was utilised to enrich the Ga-13 atropisomers. Early eluting fractions were enriched in the ααβ atropisomer (ααβ to ααα ratio of 79 : 21), while the later eluting fractions were enriched in the ααα atropisomer (30 : 70, Fig. S28).

Surprisingly, Fe-13 exhibited rather sharp peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum in the 14 to −14 ppm range with a clear four-line pattern indicative of atropisomerism (Fig. S29). Additional broad peaks were observed in the −20 to −43 ppm region, which are presumably due to protons adjacent to the paramagnetic metal centre. These signals (which integrate to 6 protons) may arise from the α dipyrrin protons. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only 1H NMR characterisation of tris homoleptic Fe(iii) dipyrrin complexes. The first study on these molecules (published in 1974) indicated that these complexes could be either be high- or low-spin, depending on the substituents of the ligand.71 Analysis of Fe-13 by the Evans method revealed a magnetic moment of 1.92 μB (Bohr Magneton). This value is similar to the expected spin-only magnetic moment for an S = 1/2 species (1.73 μB), indicating that Fe-13 is a low-spin d5 complex. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to gauge the relative energies of the high- and low-spin states of Fe-13, using meso-phenyl dipyrrin as a simplified model system for ligand 1. We denote this model complex as Fe(Ph)3 (see SI for computational details). The low-spin state (S = 1/2, Table S2) for Fe(Ph)3 is 0.26 eV (6.03 kcal mol−1) lower in energy than the high-spin state (S = 5/2, Table S3), consistent with experimental observations for Fe-13.

The Evans method revealed that Mn-13 has a magnetic moment of 4.72 μB, which is consistent with a high-spin d4 complex (expected spin-only moment of 4.90 μB for an S = 2 species). Given the strong-field nature of the dipyrrin ligand (both σ donor and π acceptor), this observation was rather unexpected, especially since the Fe(iii) analogue is low-spin. However, this result is consistent with the first reported example of a tris homoleptic Mn(iii) dipyrrin complex, which exhibited a magnetic moment of 4.82 μB.39 Consequently, the 1H NMR spectrum of Mn-13 displays poorly-resolved signals (Fig. S30). DFT calculations revealed the high-spin state (S = 2) of Mn(Ph)3 is only 3.39 × 10−3 eV (7.9 × 10−2 kcal mol−1) lower in energy than the low-spin state (S = 1, Tables S4 and S5). Since Mn(iii) porphyrins are also high-spin complexes,72 this result may not be that unexpected. We note that the recent report of Mn(iii) tris dipyrrins did not characterise the spin state of the complexes.40

The UV-vis absorption spectra of Mn-13, Fe-13, and Ga-13 (Fig. S31) exhibit a doublet feature in the 447 to 504 nm region, analogous the Co(iii) complexes. While Ga-13 has a well-resolved doublet, the transitions are broader for Fe-13 and Mn-13. Additionally, Mn-13 and Ga-13 display a broad feature at 364 nm and 355 nm, respectively. The π → π* transition centred on the aryl amide moiety is observed at 268 nm for these three complexes. Similar to other Ga(iii) tris dipyrrin complexes, Ga-13 is fluorescent. However, the emission intensity is significantly weaker than Zn-12, which has a quantum yield of only 1.9%. The low signal prevented a reliable, direct measurement of the quantum yield of Ga-13. However, we were able to estimate this value by comparing the integrated emission intensity for absorption-matched samples of Ga-13 and Zn-12 (Fig. S32). This analysis provided an estimated value of ϕf = 0.16% for Ga-13, which is significantly lower than typical Ga(iii) dipyrrin complexes (ϕf = 2.4%).73 Unlike other examples of homoleptic Ga(iii) dipyrrins that exhibit a single emission band (e.g., 530 nm for meso-mesityl dipyrrin),73Ga-13 displays two features at 550 nm and 610 nm (Fig. S33). Excitation spectra confirm that both of these bands arise from Ga-13 rather than a fluorescent impurity (Fig. S33). The small Stokes shift of the 550 nm band (1699 cm−1) is consistent with a fluorescent transition. Indeed, the emission intensity of both bands is unaffected by oxygen. This result suggests that the 610 nm band is not a phosphorescent transition, as might be expected given the large Stokes shift (3487 cm−1). While the exact origin of this second band is unknown, one possibility could be excimer formation. Two molecules of Ga-13 could associate in the excited state though π-stacking interactions between the aryl amide, giving rise to a broad, low-energy transition.

Redox chemistry of octahedral period 4 M(III) complexes

To date, there has not been a comprehensive study on the electrochemistry and redox properties of tris homoleptic dipyrrin complexes. Indeed, there are no such reports on Ga(iii) dipyrrins. Only a few studies have been published on the electrochemistry of Mn(iii),40 Fe(iii),74,75 and Co(iii)76 derivatives. To support the electrochemical assignments, we utilised DFT calculations on simplified M(Ph)3 complexes to gauge if the redox processes were ligand- or metal-centred. Moreover, the relative energies of the high- and low-spin states were determined. Since Ga(iii) is not redox active, Ga-13 was first analysed to obtain a benchmark for ligand-based processes in octahedral complexes. Ga-13 exhibits a reversible reduction at −1.71 V vs. Fc+/Fc (Fig. 10a), which is comparable to the first reduction of Zn-12 and Pd-12 at −1.73 V and −1.67 V, respectively (Table 1). To characterise this process, Ga-13 was treated with decamethylcobaltocene (Cp*2Co), which has a reduction potential of −1.91 V (vs. Fc+/Fc) in MeCN.77 The reduced complex [Ga-13]− has a magnetic moment of 2.03 μB, as measured by the Evans method. This value is similar to the expected spin-only moment (1.73 μB for an S = 1/2 species). The reduction reaction was monitored by UV-vis absorption spectroscopy (Fig. S34). Isosbestic points were maintained throughout the reaction, indicating clean reduction of Ga-13 to [Ga-13]−. The spin density plot of doublet [Ga(Ph)3]− (Table S6), obtained from the optimised geometry of Ga(Ph)3 (Table S7), exhibits delocalised electron density over a dipyrrin ligand with some density on the meso-phenyl ring (Fig. 10b). Together, these results indicate that the first reduction of Ga-13 is ligand-based. The CV of Ga-13 exhibits additional irreversible reductions at −2.09 V and −2.20 V (Fig. 10c), which we tentatively attribute to the second and third ligand reductions. The 110 mV separation between reduction events is smaller than that for Zn-12 (230 mV) and Pd-12 (220 mV). Additional irreversible reductions occur in the −2.4 V to −3.0 V range (Fig. 10c). Oxidation processes are observed at +0.89 V and +1.34 V for Ga-13. Unlike the Zn and Pd analogues, the oxidations occur in a stepwise manner. We note that the separation of the oxidation events is more pronounced when the CV is acquired in the oxidative direction (Fig. S35). This separation suggests that one dipyrrin is first oxidised, then the other two ligands are oxidised simultaneously. Indeed, the total oxidation current is nearly three times greater than that of the first one-electron reduction, as might be expected for a complex with three dipyrrin ligands.

Fig. 10. (a) and (c) Cyclic voltammograms of Ga-13 ( ), Fe-13 (

), Fe-13 ( ), and Mn-13 (

), and Mn-13 ( ), and Co-13 (

), and Co-13 ( ) in THF with 0.1 M [TBA][PF6] recorded at 100 mV s−1 under an argon atmosphere. Additional features (*) are observed due to incomplete reversibility of some electrochemical processes. The potential of the first reduction shifts to more negative potentials with increasing d-electron counts of the complex. (b) Calculated spin density plots for [Ga(Ph)3]−, [Mn(Ph)3]+, high-spin [Mn(Ph)3]−, and high-spin [Co(Ph)3]−.

) in THF with 0.1 M [TBA][PF6] recorded at 100 mV s−1 under an argon atmosphere. Additional features (*) are observed due to incomplete reversibility of some electrochemical processes. The potential of the first reduction shifts to more negative potentials with increasing d-electron counts of the complex. (b) Calculated spin density plots for [Ga(Ph)3]−, [Mn(Ph)3]+, high-spin [Mn(Ph)3]−, and high-spin [Co(Ph)3]−.

Table 1. Summary of ligand-based redox processes for complexes of ligand 1.

| Complex | 2nd Ligand reduction | 1st Ligand reduction | 1st Ligand oxidation | 2nd Ligand oxidation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn-13 | −2.92 | −2.45 | — | +1.27 |

| Fe-13 | −2.74 | −2.48 | +0.71 | +1.08 |

| Co-13 | −2.52 | −2.22 | +0.64 | +0.82 |

| Ga-13 | −2.09 | −1.71 | +0.89 | +1.34 |

| Pd-12 | −1.89 | −1.67 | +0.67 | — |

| Zn-12 | −1.95 | −1.73 | +0.73 | — |

There are two electrochemical studies that examined the electrochemistry of Fe(iii) tris dipyrrins, and both publications only reported a single reversible reduction around −1.15 V vs. Fc+/Fc.74,75 Similarly, Fe-13 exhibits a reversible, one-electron reduction at −0.92 V (vs. Fc+/Fc) (Fig. 10a). The complex was reduced with cobaltocene (Cp2Co), which has a reduction potential of −1.33 V (vs. Fc+/Fc) in CH2Cl2,77 to characterise [Fe-13]−. Upon reduction, the magnetic moment of the complex decreased from 1.92 μB to 0.77 μB. This non-zero value is likely due to incomplete reduction and/or excess Cp2Co present in the sample. The 1H NMR spectrum of [Fe-13]−, which is isoelectronic with Co-13, exhibited a loss of the paramagnetic signals in the 0 to −43 ppm region (Fig. S36). Indeed, sharp features are observed in the aromatic region and distinct methoxy signals (i.e., the characteristic four-line pattern) is indicative of the atropisomerism (Fig. S37). The UV-vis absorption spectrum of [Fe-13]− displays a sharp peak at 454 nm (Fig. S38), which resembles the spectrum of Co-13, although this feature is blue-shifted by 795 cm−1 relative to Co-13. Based on these observations, we assign the reduction at −0.92 V as the Fe(iii)/Fe(ii) couple, forming a low-spin Fe(ii) complex. We note that this reduction is shifted by 790 mV to more positive potentials compared to the first, ligand-based reduction in Ga-13 (−1.71 V), providing further evidence that this is a metal-based reduction. Additionally, there are two irreversible reductions at −2.48 V and −2.74 V, which are similar to those of Ga-13, that we tentatively assign as ligand-based reductions. Like Ga-13, irreversible ligand oxidation peaks are observed at +0.71 V and +1.08 V, and these peaks are more pronounced when scanning the CV in the oxidative direction (Fig. S35).

The recent study on Mn(iii) dipyrrin complexes reported a partial CV, yet no attempts were made to assign the origin of these redox events.40 The CV of Mn-13 exhibits more electrochemical processes at moderate potentials relative to Ga-13 and Fe-13 (Fig. 10a). A reversible, one-electron oxidation is observed at +0.25 V, which exhibits a peak-to-peak separation of 193 mV. Additionally, a reversible, one-electron reduction occurs at −0.74 V. The large 269 mV peak-to-peak separation for this feature may be suggestive of slow electron transfer. To characterise the products of these redox processes, Mn-13 was chemically oxidised with silver triflate (+0.65 V vs. Fc+/Fc in CH2Cl2).77 The magnetic moment of [Mn-13]+ is 4.05 μB, as measured by the Evans method. This value is consistent with the expected spin-only magnetic moment for an S = 3/2 species (3.87 μB). The UV-vis absorption spectrum of [Mn-13]+ displays a broader peak than the parent compound and exhibits a slight blue-shift of 651 cm−1 (Fig. S39). DFT calculations reveal that the spin density plot of quartet [Mn(Ph)3]+ (Table S8) has electron density almost exclusively located on the Mn centre (Fig. 10b). Together, the experimental and computational results support the assignment of the oxidation at +0.25 V as the Mn(iii)/Mn(iv) couple. Chemical reduction of Mn-13 with Cp2Co yields a complex with a magnetic moment of 5.47 μB (as measured by the Evans method), which is comparable to the expected value of 5.92 μB for a high-spin d5 complex (S = 5/2). Indeed, the 1H NMR spectrum of [Mn-13]− does not resemble that of the isoelectronic, low-spin complex Fe-13 (Fig. S40), further supporting the high-spin nature of [Mn-13]−. However, the UV-vis absorption spectrum of [Mn-13]− closely matches that of Fe-13 (Fig. S41). The calculated spin density plot for sextet [Mn(Ph)3]− (Table S9) illustrates that the electron density exclusively resides on the Mn(ii) metal centre (Fig. 10b). While low-spin, doublet [Mn(Ph)3]− (Table S10) exhibits a similar spin density plot (Fig. S42), this state is 0.93 eV (21.3 kcal mol−1) higher in energy than the high-spin sextet state (S = 5/2). Together, the experimental and computational data supports the assignment of the reduction at −0.74 V for Mn-13 as the Mn(iii)/Mn(ii) couple. The CV of Mn-13 also exhibits two irreversible reductions at −2.45 V and −2.92 V. Given the similarity of these features to those of Ga-13 and Fe-13, we tentatively assign these processes to ligand-based reductions.

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one study that reported the electrochemistry of Co(iii) tris dipyrrin complexes. The meso-ferrocenyl Co(iii) dipyrrins exhibited an irreversible reduction at −1.48 V vs. Fc+/Fc, which the authors presumed to be the Co(iii)/Co(ii) couple.76 Similarly, the CV of Co-13 exhibits a reversible, one-electron reduction at −1.48 V vs. Fc+/Fc (Fig. 10a). This feature is shifted by 230 mV to more positive potentials relative to the first, ligand-based reduction of Ga-13. To characterise this reduction process, Co-13 was reduced with Cp*2Co and the product was analysed by UV-vis absorption spectroscopy and 1H NMR. As expected, [Co-13]− is paramagnetic, exhibiting chemical shifts as far downfield as 72 ppm (Fig. S43). The magnetic moment of [Co-13]− is 3.62 μB (as measured by the Evans method), which is similar to the expected spin-only moment of 3.87 μB for an S = 3/2 complex. The optimised geometry of [Co(Ph)3] (Table S11) was utilised as the starting point for [Co(Ph)3]− (Table S12). The calculated spin density plot for low-spin, doublet [Co(Ph)3]− is nearly identical to that of [Ga(Ph)3]−, exhibiting ligand-centred electron density (Fig. S44). Conversely, the spin density plot of high-spin, quartet [Co(Ph)3]− (S = 3/2, Table S13) illustrates that the electron density resides predominantly on the Co centre (Fig. 10b), similar to [Mn(Ph)3]+. Moreover, the high-spin state (S = 3/2) of [Co(Ph)3]− is 0.58 eV (13.3 kcal mol−1) lower in energy than the low-spin state (S = 1/2). Both the experimental and computational results support the assignment of the reduction at −1.48 V as the Co(iii)/Co(ii) couple. The UV-vis absorption spectrum of [Co-13]− exhibits a blue-shift (1033 cm−1) relative to Co-13 (Fig. S45). Upon treatment with ambient air, [Co-13]− was immediately oxidised to Co-13, as observed by absorption spectroscopy. Since the complex is coordinatively saturated, we hypothesised that this reaction is an outer-sphere, one-electron transfer process where O2 is reduced to superoxide (O2˙−). The presence of O2˙− in the reaction mixture was determined spectrophotometrically. In this coupled assay,78 hydroquinone reacts with O2˙− to produce H2O2, which in turn reacts with I− and HCl to form I3−, which is identified by the characteristic absorption feature at 370 nm.27 However, the precise quantification was not possible due to the background reaction from excess reductant in the reaction mixture.

Additionally, the CV of Co-13 exhibits two quasi-reversible reductions at −2.22 V and −2.53 V. The total current of these processes is approximately three times higher than that of the reversible reduction, suggesting that these features correspond to the reduction of the three dipyrrin ligands. These features are significantly shifted to more negative potentials than the second ligand reduction of Zn-12 (−1.89 V). As observed for Ga-13, additional irreversible reductions are observed in the −2.7 V to −2.9 V range (Fig. 10c). Two oxidation processes are observed for Co-13 at +0.64 V and +0.82 V, which is consistent with Ga-13 and Fe-13. This separation suggests that one dipyrrin is first oxidised, followed by the other two ligands, which are oxidised simultaneously. Indeed, the total current of these oxidation waves is approximately three times higher than the one-electron reduction processes.

Conclusions

We have reported the synthesis of a novel hangman dipyrrin ligand platform with an ortho-aryl amide moiety at the meso position. This 2-substituent imposes an energetic barrier to ring rotation, resulting in the formation of atropisomers for both square planar and octahedral complexes. This study represents the first fully characterised examples of atropisomerism in square planar and octahedral dipyrrin complexes. Differences in solubility and polarity can be leveraged to significantly enrich the atropisomers. The hanging group (–OMe, –OH, –H), which is 11 atoms away from the metal centre, has a noticeable effect on the properties of the metal centre. This includes changes in bond lengths (shorter Zn–N bonds in Zn-22 than Zn-12) and electrochemical properties (loss of reversibility in ligand reduction of Zn-22, Fig. 3).

Unlike the homoleptic tris dipyrrin complexes that are coordinatively saturated, the palladium complex Pd-22, represents a faithful structural mimic of the PMO active site (Fig. 1). The atropisomerism confers rigidity to the secondary coordination sphere, thereby mimicking the “fixed”, stable positioning of amino acid side chains in the protein active site. Indeed, the αβ atropisomer (Fig. 6) positions a –OH group above and below the metal centre, analogous to the tyrosine and threonine residues in fungal PMOs. Importantly, we have demonstrated that these atropisomers can be significantly enriched, providing the control necessary to dictate the position of the hanging group for future catalytic applications. Our results demonstrate that complex Pd-22 exhibits several key hallmarks that emulate the secondary coordination spheres of metalloproteins. The phenol hanging group serves as a proton relay, which is crucial for future reaction chemistry involving PCET. Both the phenol and amide can engage in hydrogen-bonding interactions with small, substrate-like molecules (e.g., DMSO, acetate), as demonstrated by X-ray crystallography and 1H NMR spectroscopy. Consequently, the entire meso-aryl amide, not just the hanging group, contributes to the secondary coordination sphere. These non-covalent, supramolecular interactions could be exploited to precisely position a substrate for regioselective functionalisation, akin to a protein active site.

This study provides the first comprehensive, holistic electrochemical characterisation of period 4 tris dipyrrin complexes. The metal-based redox events for the Mn(iii), Fe(iii), and Co(iii) derivatives have been unambiguously identified through the preparation and analysis of [Mn-13]+, [Mn-13]−, [Fe-13]−, and [Co-13]− in conjunction with complementary DFT calculations. It is noteworthy that the dipyrrin ligand platform enables easy access to Mn(iv) at very mild potentials (+0.25 V vs. Fc+/Fc). This electrochemical analysis will guide future synthetic and catalytic endeavours with these first-row transition metal dipyrrin complexes.

This study demonstrates that the hangman dipyrrin approach confers secondary sphere effects, including proton transfer and small-molecule binding, that emulate the active site of metalloproteins. Since the complexes presented in this study are coordinatively saturated, their reaction chemistry is limited. To address this, we are currently synthesising heteroleptic complexes of our hangman dipyrrin ligands with open coordination sites or weakly bound ligands. These new complexes will combine a versatile primary coordination sphere that is amenable to substrate binding with a functional secondary coordination sphere. We will also vary the transition metal to access the necessary redox potentials and electronic structure (e.g., oxidation and spin states) to activate O2 and perform subsequent oxygen atom transfer (OAT) to organic substrates. Since these dipyrrins are unsubstituted at the α and β positions, the redox properties of the ligand could be readily modulated by introducing peripheral substituents to access the desired reactivity. Finally, the pKa of the hanging group could be modified to activate the M–O2 adduct and achieve OAT reactivity. This modular hangman dipyrrin ligand platform provides a foundation to design faithful structural and functional mimics of metalloenzyme active sites.

Author contributions

I. S. S. and C. M. L. conceptualised the project. M. A. M. and C. M. L. supervised the work. I. S. S. and M. E. S. performed the experimental synthesis and characterisation of the complexes. W. C. R. performed the DFT calculations. I. S. S., W. C. R., M. A. M., and C. M. L. contributed to experimental design. I. S. S. and C. M. L. performed analysis of the experimental data. W. C. R. and M. A. M. performed analysis of the computational data. I. S. S. and C. M. L. wrote the original manuscript draft. All authors contributed to discussions on the data and to the development of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C. M. L. acknowledges the College of Letters & Science and the Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development at Montana State University for startup funds. We thank Dr Daniel Decato for acquiring the X-ray diffraction data, as well as performing the data analysis and structure refinement at the University of Montana Small Molecule X-ray Diffraction Core, which is principally supported by an NSF MRI grant (CHE-1337908). This core facility is operated through the Centre for Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics (CBSD) CoBRE, which is funded by the NIH NIGMS grant P30GM140963. ESI-MS data were acquired at the Proteomics, Metabolomics, and Mass Spectrometry Facility (RRID:SCR_012482) at Montana State University (MSU). Funding for this core facility was made possible in part by the MJ Murdock Charitable Trust, the NIH (under Awards P20GM103474 and S10OD028650), and the MSU Office of Research, Economic Development, and Graduate Education. We thank Dr Bernard Linden and Dr Mathias Linden for acquiring the LIFDI mass spectrometry data, and Prof. Joan Broderick for allowing us to utilise the Shimadzu HPLC. The authors thank Prof. David Fialho for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Dr Brian Tripet for assistance and guidance in acquiring NMR data. The MSU Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Facility (RRID:SCR_026334) is a user-supported facility operating under the Office of the Vice President of Research and Economic Development. Additional funding for the NMR Centre was made possible in part by the MJ Murdock Charitable Trust (under award 2015066:MNL), the National Science Foundation (under award NSF-MRI:DBI-1532078 and NSF-MRI:CHE-2018388), and the Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development at MSU. Computational work was performed on the Tempest High Performance Computing System, operated and supported by University Information Technology Research Cyberinfrastructure (RRID:SCR_026229) at MSU.

Data availability

CCDC 2483117 (Pd-1-acac, polymorph 2), 2483118 (Zn-22), 2483119 (Zn-12), 2483120 (Pd-1-acac, polymorph 1), 2483121 (Co-13), and 2497161 (Pd-22) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper.79a–f

Supplementary information: full experimental details, synthetic methods, computational details, characterisation data, and additional experimental results. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d5sc06893b.

References

- Holm R. H. Solomon E. I. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:347–348. doi: 10.1021/cr0206364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groysman S. Holm R. H. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2310–2320. doi: 10.1021/bi900044e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. C. Lo W. Holm R. H. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:3579–3600. doi: 10.1021/cr4004067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taut J. Chambron J.-C. Kersting B. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2023;26:e202200739. doi: 10.1002/ejic.202200739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stripp S. T. Duffus B. R. Fourmond V. Léger C. Leimkühler S. Hirota S. Hu Y. Jasniewski A. Ogata H. Ribbe M. W. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:11900–11973. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collman J. P. Boulatov R. Sunderland C. J. Fu L. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:561–588. doi: 10.1021/cr0206059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. Marletta M. A. ChemBioChem. 2019;20:7–19. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201800478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon E. M. Huang S. H. Marletta M. A. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nchembio704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale S. W. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3317–3337. doi: 10.1021/cr0503153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. S. Tyler E. M. Akyumani N. Kurtis C. R. Spooner R. K. Deacon S. E. Tamber S. Firbank S. J. Mahmoud K. Knowles P. F. Phillips S. E. V. McPherson M. J. Dooley D. M. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4606–4618. doi: 10.1021/bi062139d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez R. L. Juntunen N. D. Brunold T. C. Acc. Chem. Rev. 2022;55:2480–2490. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon E. I. Szilagyi R. K. George S. D. Basumallick L. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:419–458. doi: 10.1021/cr0206317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon E. I. Hadt R. G. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011;255:774–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray H. B. Malmström B. G. Williams R. J. P. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000;5:551–559. doi: 10.1007/s007750000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi U. Addison A. W. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1979:600–608. doi: 10.1039/DT9790000600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P. L. Tolman W. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:6331–6332. doi: 10.1021/ja001328v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P. J. Dake M. J. Remolina A. D. Olshansky L. Dalton Trans. 2023;52:8376–8383. doi: 10.1039/d3dt01213a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P. J. Olshansky L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023;145:20158–20162. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c05935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon C. M., Dogutan D. K. and Nocera D. G., in Handbook of Porphyrin Science, ed. K. M. Kadish, K. M. Smith and R. Guilard, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, 2012, vol. 21, pp. 1–143 [Google Scholar]

- Bediako D. K. Solis B. H. Dogutan D. K. Roubelakis M. M. Maher A. G. Lee C. H. Chambers M. B. Hammes-Schiffer S. Nocera D. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:15001–15006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414908111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal J. Nocera D. G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:543–553. doi: 10.1021/ar7000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal J. Nocera D. G. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 2007;55:483–544. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. K. Kondylis M. P. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986:316–318. doi: 10.1039/C39860000316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C.-Y. Chang C. J. Nocera D. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1513–1514. doi: 10.1021/ja003245k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogutan D. K. Bediako D. K. Graham D. J. Lemon C. M. Nocera D. G. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2015;19:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Margarit C. G. Schnedermann C. Asimow N. G. Nocera D. G. Organometallics. 2018;38:1219–1223. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beagan D. M. Rivera C. Szymczak N. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:12375–12385. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c12399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt K. H. S. Fiorentini F. Lindeboom W. Williams C. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:10451–10464. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c13959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Hernandez J. L. Zhang X. Cui K. Deziel A. P. Hammes-Schiffer S. Hazari N. Piekut N. Zhong M. Chem. Sci. 2024;15:6800–6815. doi: 10.1039/d3sc06177a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi J. Saha A. Barman S. K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2025;64:e202501338. [Google Scholar]

- Beeson W. T. Vu V. V. Span E. A. Phillips C. M. Marletta M. A. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015;84:923–946. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangasky J. A., Detomasi T. C., Lemon C. M. and Marletta M. A., in Comprehensive Natural Products III: Chemistry and Biology, ed. H.-W. Liu and T. P. Begley, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2020, vol. 5, pp. 298–331 [Google Scholar]

- Wood T. E. Thompson A. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:1831–1861. doi: 10.1021/cr050052c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudron S. A. Dalton Trans. 2020;49:6161–6175. doi: 10.1039/D0DT00884B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. S. Paitandi R. P. Gupta R. K. Pandey D. S. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020;414:213269. [Google Scholar]

- Schomberg-Sanchez I. S. Janusz W. A. Lemon C. M. J. Coord. Chem. 2025;78 doi: 10.1080/00958972.2025.2539945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps J. Chang Y. Langlois A. Desbois N. Gros C. P. Harvey P. D. New J. Chem. 2016;40:5835–5845. [Google Scholar]

- Carsch K. M. Lukens J. T. DiMucci I. M. Iovan D. A. Zheng S.-L. Lancaster K. M. Betley T. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:2264–2276. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y. Sakata K. Harada K. Matsuda Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1974;47:3021–3024. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.47.3021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rawool H. Saini A. Dey S. Das C. Dutta A. Ghosh P. Chem.–Asian J. 2025;20:e00325. doi: 10.1002/asia.202500325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collman J. P. Gagne R. R. Reed C. A. Halbert T. R. Lang G. Robinson W. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:1427–1439. doi: 10.1021/ja00839a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley M. J. Field L. D. Forster A. J. Harding M. M. Sternhell S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:341–348. doi: 10.1021/ja00236a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collman J. P. Decréau R. A. Org. Lett. 2005;7:975–978. doi: 10.1021/ol048185s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melissari Z. Twamley B. Gomes-da-Silva L. C. O'Brien J. E. Schaberle F. A. Kingsbury C. J. Williams R. M. Senge M. O. Chem.–Eur. J. 2025;31:e202404777. doi: 10.1002/chem.202404777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. Mack J. Xiao X. Li Z. Lu H. Chem.–Asian J. 2017;12:2216–2220. doi: 10.1002/asia.201700584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.-Z. Zheng H.-R. Niu L.-Y. Chen Y.-Z. Wu L.-Z. Tung C.-H. Yang Q.-Z. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2015;26:631–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2015.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuckowree I. Syed M. A. Getti G. Patel A. P. Garner H. Tizzard G. J. Coles S. J. Spencer J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:3607–3611. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown University, US. Pat., WO2014014814A1, 2014

- Chen Y. He H. Jiang H. Li L. Hu Z. Huang H. Xu Q. Zhou R. Deng X. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;30:127021. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ChangZhou Kangpu Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, CN. Pat., CN112457275A, 2021

- Hiroto S. Miyake Y. Shinokubo H. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:2910–3043. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waibel M. Angelis M. D. Stossi F. Kieser K. J. Carlson K. E. Katzenellenbogen B. S. Katzenellenbogen J. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:3412–3424. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brückner C. Karunaratne V. Rettig S. J. Dolphin D. Can. J. Chem. 1996;74:2182–2193. [Google Scholar]

- Berezin M. B. Antina E. V. Guseva G. B. Kritskaya A. Y. Semeikin A. S. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020;111:107611. [Google Scholar]

- Marchon J.-C. Ramasseul R. Ulrich J. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1987;24:1037–1039. doi: 10.1002/jhet.5570240425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naitana M. L. Osterloh W. R. Zazzo L. D. Nardis S. Caroleo F. Stipa P. Truong K.-N. Rissanen K. Fang Y. Kadish K. M. Paolesse R. Inorg. Chem. 2022;61:17790–17803. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c03099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avan İ. Kani İ. Çalıkuşu L. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023;150:110518. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh C. Kirlikovali K. Das S. Ener M. E. Gray H. B. Djurovich P. Bradforth S. E. Thompson M. E. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:21834–21845. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto R. Iwashima T. Kögel J. F. Kusaka S. Tsuchiya M. Kitagawa Y. Nishira H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5666–5677. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M. L. Schmink J. R. Leadbeater N. E. Brückner C. Dalton Trans. 2008:1341–1345. doi: 10.1039/B716181F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese S. Holzapfel M. Schmiedel A. Gert I. Schmidt D. Würthner F. Lambert C. Inorg. Chem. 2018;57:12480–12488. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord E. Zhou H. Rayat S. New J. Chem. 2021;45:14184–14192. [Google Scholar]

- Makuc D. Hiscock J. R. Light M. E. Gale P. A. Plavec J. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011;7:1205–1214. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner C. Baudron S. A. Hosseini M. W. Strassert C. A. Guenet A. De Cola L. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Das S. Gupta I. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2015;60:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. K. Pandey R. Sharma S. Pandey D. S. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:8556–8566. doi: 10.1039/C2DT30212H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brückner C. Zhang Y. Rettig S. J. Dolphin D. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1997;263:279–286. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(97)05700-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shroyer A. L. W. Lorberau C. Eaton S. S. Eaton G. R. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:4296–4302. [Google Scholar]

- Farfán-Paredes M. González-Antonio O. Tahuilan-Anguiano D. E. Peón J. Ariza A. Lacroix P. G. Santillan R. Farfán N. New J. Chem. 2020;44:19459–19471. doi: 10.1039/D0NJ02576C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. H. Kim K. Jeon J. Meka B. Bucella D. Pang K. Khatua S. Lee J. Churchill D. G. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:11071–11083. doi: 10.1021/ic801354y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y. Matsuda Y. Sakata K. Harada K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1974;47:458–462. [Google Scholar]

- Krzystek J. Telser J. Pardi L. A. Goldberg D. P. Hoffman B. M. Brunel L.-C. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:6121–6129. doi: 10.1021/ic9901970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoi V. S. Stork J. R. Magde D. Cohen S. M. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:10688–10697. doi: 10.1021/ic061581h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. M. Halper S. R. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2002;341:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Halper S. R. Cohen S. M. Chem.–Eur. J. 2003;9:4661–4669. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. K. Pandey R. Sharma S. Pandey D. S. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:8556–8566. doi: 10.1039/C2DT30212H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly N. G. Geiger W. E. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:877–910. doi: 10.1021/cr940053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayyan M. Hashim M. A. AlNashef I. M. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:3029–3085. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) CCDC 2483117 (Pd-1-acac, polymorph 2): Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2025, 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2pbwkh [DOI]; (b) CCDC 2483118 (Zn-22): Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2025, 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2pbwlj [DOI]; (c) CCDC 2483119 (Zn-12): Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2025, 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2pbwmk [DOI]; (d) CCDC 2483120 (Pd-1-acac, polymorph 1): Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2025, 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2pbwnl [DOI]; (e) CCDC 2483121 (Co-13): Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2025, 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2pbwpm [DOI]; (f) CCDC 2497161 (Pd-22): Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2025, 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2pthlm [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations