Abstract

Background

Fusarium crown rot (FCR), primarily caused by Fusarium pseudograminearum, has emerged as a globally significant disease severely threatening the stability of wheat production. Breeding FCR-resistant germplasms and clarifying the underlying resistance mechanisms are critical prerequisites for effective disease management.

Results

In this study, to generate genotypes with enhanced FCR resistance, an EMS-mutagenized population was developed from AK58, and a germplasm X413 with stably moderate resistance to FCR at both the seedling and adult stages was identified. Phenotypic analysis showed that X413 exhibited stronger ability to inhibit the expansion and mycelial growth of F. pseudograminearum. Transcriptome (RNA-seq) comparison with highly susceptible X73 revealed that X413 had fewer differentially expressed genes (DEGs) after pathogen infection, with its specific DEGs significantly enriched in resistance-related pathways such as “lignin metabolic process” and “phenylpropanoid biosynthesis”. In contrast, X73 had more DEGs, and genes related to growth and development including those for DNA replication and post-replication repair were significantly downregulated, consistent with its more obvious plant height reduction after pathogen infection. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) identified hub genes highly expressed in X413, including ubiquitin-related genes, kinase genes, and three germin-like protein genes (with SOD activity involved in hydrogen peroxide production). Physiological assays confirmed that X413 had significantly higher hydrogen peroxide content and SOD activity than X73.

Conclusions

Collectively, FCR resistance in X413 may be associated with efficient activation of disease resistance pathways and balanced growth-defense metabolism. This germplasm could serve as a valuable resistance source to support wheat breeding for FCR resistance, and the mechanistic insights obtained may also lay a solid theoretical foundation for the mining and utilization of resistance genes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-025-12237-x.

Keywords: Wheat, Fusarium crown rot, EMS-induced germplasm X413, Resistance, Transcriptome

Introduction

As one of the most widely cultivated cereal crops globally, wheat plays a critical role in food security and global economic development through its stable production. During its field growth cycle, wheat must continuously adapt to environmental changes and respond to biotic or abiotic stresses [1, 2]. In recent years, the frequent occurrence of extreme weather events and alterations in cropping systems have led to frequent infections of wheat by pathogenic fungi, causing regional or widespread diseases such as Fusarium head blight (FHB), powdery mildew, stripe rust, and Fusarium crown rot (FCR) [2]. Notably, FCR was first detected in Australia and subsequently first reported in China in 2012 [3]. Since then, the disease has spread rapidly, characterized by annual expansion of diseased areas and escalating damage severity [4]. Data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs show that the total affected area nationwide exceeded 30 million mu (2 million hectares) in 2023, representing a 200% increase from 2018. Therefore, the development of effective control strategies for this disease has become an urgent and critical priority. It is thus imperative to create disease-resistant germplasm through multiple approaches to mitigate the threat of FCR and its impact on wheat yield stability.

By utilizing conventional cultivated germplasm, distant hybrid germplasm, and other approaches, researchers have undertaken systematic efforts to identify wheat resources with significantly enhanced resistance to FCR. Benefiting from these investigations, the FCR resistance profiles of diverse germplasms have been systematically characterized. Notably, a series of elite resistant materials have been identified, including foreign germplasms such as 2–49 [5, 6], Sunco [6], EGA Wylie [7], and CSCR6 [8, 9]. Several resistant genotypes have also been reported in China. They included Jinmai 1 [4, 10], 04 Zhong 36 [11], Cunmai 633 [12], Zimai 12 [13], YB-1631 [14] and Heng 4332 [15]. QTL mapping for FCR resistance revealed that 2–49 harbored resistance loci on chromosome arms 1AS, 1BS, and 4BS, while Sunco possessed a major QTL on 2BS, both effective at seedling and adult plant stages [6, 16]. In EGA Wylie, through constructing multiple recombinant inbred line (RIL) populations, researchers mapped major resistance QTLs on chromosome arms 5DS and 2DL, with additional loci detected on 4BS [7, 17]. Furthermore, the FCR resistance locus Qcrs.cpi-3B in CSCR6 was mapped to the long arm of chromosome 3B [9, 17]. For those resistant genotypes identified in China, researchers have successively identified novel FCR resistance loci through multi-germplasm GWAS and biparental populations developed from elite materials [4, 10, 11, 13, 15, 18–23]. Statistical analysis showed that the identified QTLs for FCR resistance have covered all 21 chromosomes of wheat, with loci on 1BS, 2AL, and 3BL repeatedly detected across diverse genetic backgrounds [4, 6, 11, 17, 23]. Furthermore, resistance genes such as TaDIR-B1 [10], TaCWI-B1 [20] and TaCAT2 [4] have been cloned from these QTL regions. Notably, germplasms carrying the Fusarium head blight resistance gene Fhb7 can also enhance seedling-stage resistance to FCR in wheat [24].

Despite remarkable advances in identifying FCR-resistant germplasm and mapping quantitative trait loci, the majority of wheat germplasms evaluated for FCR resistance have been classified as susceptible to FCR, and no germplasm with consistently high resistance or immunity to FCR has been identified. For example, Yang et al. (2019) showed that among 234 wheat germplasms tested, only 7 had a disease index (DI) below 30, indicating their potential for FCR resistance breeding. By contrast, over 97% of germplasms exhibited susceptibility to FCR [10]. Similar results were also observed in Li et al.‘s study, where over 96% of germplasms had a DI greater than 40 [15]. Given the severe scarcity of FCR-resistant germplasm and the escalating environmental degradation, the urgency to develop more highly resistant germplasm is thereby intensified.

Ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) mutagenesis serves as a crucial approach for creating novel crop germplasms, which has been widely applied in major crops such as rice [25], maize [26], and wheat [22]. Germplasm innovation and functional gene mining based on mutant libraries have not only provided new materials for crop genetic improvement but also laid a scientific foundation for basic research. In wheat, the construction of EMS mutant libraries is ongoing, and the identification of EMS-mutagenized germplasms with FCR resistance is being carried out simultaneously. fcrZ22, an EMS mutant derived from the genetic background of Zhoumai 22, was found to exhibit superior FCR resistance [27]. This mutant was subsequently used to develop a biparental population with Zhoumai 22 for mapping resistance QTLs [27]. Additionally, Xu et al. (2024) identified C549, a stable FCR-resistant mutant at the seedling stage, from an EMS mutant library of CN16. Fine-mapping revealed that the resistance QTL in C549 is located on chromosome 2 A, explaining over 24.2% of phenotypic variation [22]. Thus, EMS mutagenesis is expected to provide critical support for the creation of FCR-resistant germplasms.

A better understanding of the defense mechanisms of FCR in wheat can provide new strategies for developing cultivars with enhanced resistance. With the gradual improvement of wheat genome information, technologies such as RNA-seq can be more rationally applied to assist in deciphering the mechanisms underlying wheat resistance to FCR. In fact, several transcriptome sequencing studies related to FCR have been progressively conducted. RNA-seq alone or combined with metabolomics using domestic and international FCR-resistant/susceptible wheat materials has shown that upon F. pseudograminearum infection, genes related to oxidative stress, primary and secondary metabolism, and hormones (e.g., brassinosteroids, BR) are significantly affected, implying that these pathways are inextricably linked to wheat FCR resistance [28–30]. In addition, transcriptomic analysis has also been used to study differential gene expression among wheat subgenomes (A/B/D) and explain why hexaploid wheat exhibits superior FCR resistance compared to its tetraploid progenitors [31, 32]. Intriguingly, wheat FCR resistance was found to be correlated with drought tolerance, and the underlying mechanisms were further deciphered via transcriptomic sequencing, while the differential responses between wheat and barley under drought stress and F. pseudograminearum infection were also analyzed [33, 34].

To generate genotypes with enhanced FCR resistance, an EMS-mutagenized population was developed from AK58, and a germplasm X413 with stably moderate resistance to FCR at both the seedling and adult stages was identified. A detailed phenotypic observation was conducted by comparing with AK58 and X73 (a highly susceptible EMS-induced germplasm). Further, transcriptome sequencing and WGCNA analysis were performed on X413 and X73. Combined with phenotypic and physiological indices, the potential mechanisms underlying FCR resistance in X413 were preliminarily revealed. This study provides new breeding materials and theoretical support for wheat FCR resistance improvement.

Materials and methods

Wheat materials and FCR disease assessment

In this study, a M8 EMS-mutagenized library of wheat cultivar AK58 (526 accessions) was used alongside wild-type AK58 for F. pseudograminearum inoculation and FCR disease assessment. The F. pseudograminearum strain HN-1 A collected from natural wheat fields in Henan Province, China was first used for inoculating wheat. Subsequently, another F. pseudograminearum strain HN-2 A, also collected from Henan Province, China, and strain WZ-8 A kindly provided by Professor Honglian Li of Henan Agricultural University, were used to further evaluate the FCR resistance of specific germplasms. Fungal culture and spore suspension preparation were modified from the method of Jin et al. (2020). Briefly, F. pseudograminearum strains were inoculated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates and incubated at 25 °C for 7 days. After purified mycelia covered the plates, 5-mm diameter mycelial plugs were taken from the plate edge and transferred to carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) liquid medium, shaken at 160 rpm for 3 days at 25 °C. Spores were collected, resuspended to 1 × 10⁶ spores/mL, and mixed with Tween-20 solution at a volume ratio of 1000:1 before use.

Wheat seeds of all accessions were surface-sterilized with alcohol and sodium hypochlorite for germinated. Ten germinated seedlings with uniform growth were selected, immersed in the adjusted spore suspension for 1 min, and transplanted into 7 cm×7 cm square pots filled with sterilized nutrient soil. Three biological replicates (pots) were set up for each germplasm material, which were then cultivated in a greenhouse at Henan Institute of Science and Technology under conditions of 24 °C, a 14 h light/10 h dark photoperiod, and 70% relative humidity.

Approximately 21 days post-inoculation (dpi), the disease symptoms of AK58 and its mutant lines were preliminarily evaluated. FCR severity was scored using a 0 (no obvious symptom) to 5 (whole plant severely to completely necrotic) rating scale as described by Li et al. (2008). The disease index (DI) for each line (pot) was calculated using the formula: DI = (∑nX/5 N) × 100, where X is the disease grade, n is the number of plants in that grade, and N is the total number of plants evaluated per pot. Resistance levels of the tested germplasms were classified into four categories based on DI values: resistant (R, DI < 25), moderately resistant (MR, 25 ≤ DI < 40), susceptible (S, 40 ≤ DI < 55), and highly susceptible (HS, DI ≥ 55). Each germplasm was subjected to three independent biological replicates (pots). After counting the disease index of each replicate, the average value was calculated as the final disease index of the germplasm.

Field evaluations for FCR severity grading were conducted in Huixian, Henan Province, China from 2020 to 2022. Each germplasm was arranged with three biological replicates, with each replicate planted in a single row of 1.2 m in length and 10 cm in row spacing. During the sowing and jointing stages, diseased wheat grains were evenly applied to the soil surface and around the stem bases of wheat plants, followed by covering with a layer of soil substrate. Field management was performed according to standard wheat cultivation practices. At the disease development stage, the number of whiteheads of each germplasm in individual rows was surveyed, and the whitehead rate was calculated to quantify the disease severity.

Phenotypic analysis

The assessment of resistance to F. pseudograminearum expansion in each line was modified based on the method described by Zhang et al. (2009) [35]. Briefly, wheat seeds were sterilized and germinated, and 7-day-old seedlings were used for the assay. A wound was artificially created at the stem base of seedlings, approximately 1.5 cm from the root, using a micro-syringe. Then, 3 µL of spore suspension (1 × 10⁶ spores/mL) was inoculated at the wound site, ensuring it just adhered to the seedling stem. After treatment in a moist, dark environment for 1 day, the seedlings were transferred to a growth chamber set at 25 ± 2℃ with 70% relative humidity and a 12-h light/dark cycle. The necrosis degree at the stem base wound of each plant was observed 5 days later. Meanwhile, the hyphal growth of F. pseudograminearum on different germplasm materials was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) at 3 dpi and 5 dpi.

RNA extraction and illumina sequencing

Stem base samples of X413 and X73 were collected at 0, 12, 24, 48, 72 h post-inoculation (hpi) with strain HN-1 A, with three biological replicates per time point. Total RNA was extracted using the TransZol Up Plus RNA Kit (Cat#ER501-01, TransGen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After assessing RNA integrity and concentration via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, USA), library construction was performed for a total of 30 samples, followed by sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform to generate paired-end reads. The reads files of this study are accessible from the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB) database under Accession Number PRJCA043402.

Raw reads were filtered using Seqtk to obtain clean reads. The specific filtering parameters and criteria are as follows:1. Remove adapter sequences contained in the sequencing reads; 2. Trim bases with Phred quality scores (Q scores) below 20 from the 3’ end (the relationship between Q score and base error rate is Q=−10log₁₀error_ratio, where Q ≥ 20 corresponds to a base error rate ≤ 0.01); 3. Discard reads shorter than 25 bp; 4. Remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA) reads of the species from the dataset. The resulting clean reads were then aligned to the complete IWGSC RefSeq v2.1 whole-genome sequence using HISAT2 (version: 2.0.4) to obtain uniquely mapped reads [36]. Then, StringTie (version: 1.3.0) was applied to calculate the fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) for estimating gene expression levels [37–39]. Only genes with an FPKM > 5 in at least one sample were included in subsequent analyses. Differential expression analysis of genes was performed using the DESeq R package, with genes meeting the criteria of P-value ≤ 0.05 and |log2Ratio| ≥ 1 being defined as differentially expressed.

Bioinformatics analysis

Venn diagrams were generated using the jvenn webtool (https://jvenn.toulouse.inrae.fr/app/example.html). GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed with TBtools-II software [40], and result visualization was conducted via the ImageGP 2 webserver and R [41]. Only the enriched terms with corrected p-value < 0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg method) were selected for presentation. A gene co-expression network was constructed using WGCNA based on DEGs, followed by the identification of highly co-expressed gene modules [42]. Co-expression network visualization of genes in the Turquoise and salmon modules, as well as the screening of hub genes, was implemented using Cytoscape 3.3.0 [43].

Determination of H₂O₂ content and SOD activity

The hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) content in stem bases was determined using the fluorescent probe localization method. Briefly, the inner epidermis of stem bases from different wheat lines was peeled manually (each piece with an area of approximately 1 cm²) and immersed in Mes-KCl loading buffer. Then, 1 µL of H₂DCFDA reaction solution dissolved in DMSO was added, followed by incubation in the dark for 15–20 min. After rinsing three times with Mes-KCl buffer, the samples were mounted on glass slides and observed and photographed under a conventional fluorescence microscope.

For superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity assay: 7-day-old wheat seedlings were inoculated with F. pseudograminearum spore suspension at a concentration of 1 × 10⁶ spores·mL⁻¹. A 0.1 g sample of stem base tissues was collected at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 dpi, with three replicates per treatment. SOD activity was measured using the microplate method, following the instructions provided with the Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity Assay Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

Validation of RNA-seq results based on qRT-PCR analysis

qRT-PCR was performed to validate whether the expression patterns of selected genes were consistent with the RNA-seq results. Specifically, stem base samples of X413 and X73 were collected at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hpi with strain HN-1 A for subsequent RNA extraction. Reverse transcription was conducted using StarScript III All-in-one RT Mix with gDNA Remover (Genstar, Beijing, China), and qRT-PCR amplification was performed with 2×RealStar Fast SYBR qPCR Mix (Low ROX) (Genstar, Beijing, China) following the manufacturers’ protocols. Gene-specific primers for each target gene (Table S5) were retrieved from the qPrimerDB database (https://qprimerdb.biodb.org/) [44], and the relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the ΔΔCt algorithm, with TaTubulin serving as the internal reference gene. Melt curves were run for all primer pairs. All qRT-PCR experiments included three biological replicates.

Statistical analysis

For multiple comparisons, statistical significance analysis was accomplished with SPSS Statistics 17.0 software. Specifically, when pairwise comparisons between specific groups were required, Student’s t-test was applied where suitable to assess group differences.

Results

Evaluation of mutant lines for resistance to FCR in seedling stages

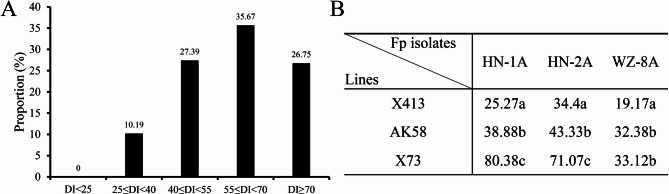

To identify wheat germplasm with superior resistance to FCR, this study inoculated AK58 and its EMS-induced mutants at the seedling stage with F. pseudograminearum strain HN-1A (isolated by our laboratory from diseased wheat fields in Henan, China) to evaluate the FCR resistance of each tested genotype. Their DIs and frequency distributions are presented in Table S1 and Fig. 1. The assessment defined AK58 as a moderately resistant cultivar with the average DI of 38.88, and showed a very broad range of DI from 25.27 to 80.38 among the mutant lines. After statistical analysis of the DI of all germplasm accessions, we found that the proportion of mutant lines with DI ranging from 50 to 70 had the highest proportion (35.67%), which were followed by those with DI in the range of 40 to 55 (27.39%) and those with DI above 70 (26.75%). Most of the tested lines exhibited a highly susceptible phenotype (62.64%: DI > 55) or a susceptible phenotype (27.39%: 40 ≤ DI < 55) to FCR. No resistant (R, DI < 25) lines were found, while only 10.19% lines were moderately resistant to FCR with an average DI less than 40 (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of FCR DI in mutant germplasms and DI under different F. pseudograminearum isolates. A Distribution of FCR DI in EMS mutant germplasms derived from AK58. B FCR DI of X413, AK58, and X73 under different F. pseudograminearum isolates. Fp, abbreviation for F. pseudograminearum

The assessment found that, among all the mutant lines, X413 (DI, 25.27), that showed the best resistance to FCR. Further, the resistance of this line to FCR was evaluated using two additional F. pseudograminearum isolates, HN-2 A and WZ-8 A. Compared to the control variety AK58, which yielded DI values of 43.33 and 32.38, X413 exhibited DIs of 34.40 and 19.17, respectively (Fig. 1B). These results were consistent with those obtained using HN-1 A, indicating its potential for wheat FCR resistance breeding. Additionally, we focused on high-susceptibility (HS) mutant lines and identified X73, which showed stably high DI to HN-1 A. Further evaluation confirmed that it was more susceptible than X413 to various F. pseudograminearum isolates (Fig. 1B). These varieties might be regarded as important sources that could aid in enhancing wheat breeding for FCR resistance and isolating resistance/susceptibility (R/S) loci.

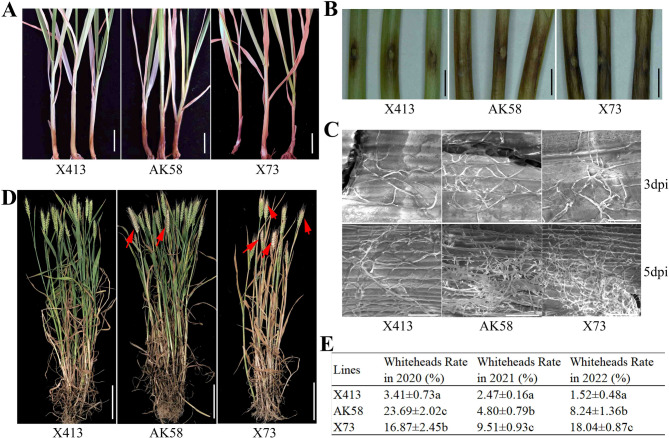

Phenotypic characteristics of X413 and X73

We then compared the phenotypic characteristics of X413 and X73 after F. pseudograminearum inoculation in detail for the further understanding of the difference in FCR resistance between them. After treatment with HN-1 A spore suspension, X413 showed a relatively stronger seedling phenotype, and the FCR symptoms of X413 plants were lighter than that of AK58. On the contrary, X73 seedlings were found to be accompanied by small and weaker plants and obviously blackened stem bases (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

FCR phenotypes of X413, AK58, and X73. A FCR phenotypes of X413, AK58, and X73 at the seedling stage after inoculation with F. pseudograminearum. Bar = 1 cm. B Disease progression in the stem of X413, AK58, and X73. Bar = 0.5 cm. C Mycelial distribution in the stem of X413, AK58, and X73 after F. pseudograminearum inoculation. Bar = 50 μm. D Whitehead incidence of X413, AK58, and X73 in a diseased wheat field. Bar = 10 cm. E Whitehead rate of X413, AK58, and X73 in the diseased wheat field from 2020 to 2022

By artificially creating wounds at the stem base and inoculating with HN-1 A spore suspension, we investigated the ability of X413, AK58, and X73 to resist the expansion of pathogenic fungi. It was found that there were significant differences in their resistance to fungal expansion (Fig. 2B). At 5 dpi, only a small area of dark brown plaques formed at the wound site of X413; the browning area at the wounds of AK58 and X73 was much larger and darker than that of X413, with X73 being the most prominent (Fig. 2B). Further SEM observations showed that X413, AK58, and X73 had similar hyphal distributions at 3 dpi with HN-1 A spore suspension; however, at 5 dpi, compared with AK58, fewer hyphae were attached to the infected stems of X413, while more hyphae were distributed in the stems of X73 (Fig. 2C).

To preliminarily assess the FCR resistance of X413 and X73 under diseased wheat field conditions, we quantified the whitehead rates of X413, X73, and AK58 following inoculation with F. pseudograminearum over three consecutive growing seasons (2020–2022) (Fig. 2D-E). Phenotypic observations and statistical analysis revealed that X413 consistently exhibited a significantly lower whitehead rate (3.41%, 2.47% and 1.52%) in the field compared to AK58 and X73. Additionally, X73 showed a whitehead rate (16.87%) intermediate between X413 (3.41%) and AK58 (23.69%) in 2020, whereas in 2021 and 2022, its whitehead rate (9.51% and 18.04%) was significantly higher than those of both X413 (2.47% and 1.52%) and AK58 (4.80% and 8.24%) (Fig. 2D-E). Collectively, these findings suggest that X413 may exhibit considerable potential for resistance to FCR at both the seedling and adult plant stages.

Transcriptomic responses of X413 and X73 to F. pseudograminearum

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms for the differential F. pseudograminearum responses between X413 and X73, comparative RNA-seq analysis was performed. Samples from the two genotypes were taken at 0, 12, 24, 48, 72 hpi for sequencing, thus generating a total of 33.1 to 40.2 million clean reads for of the samples (Table S1). The clean reads were mapped against the reference genome of common wheat. Over 79.3% of the reads from these samples were mapped, and up to 99% of them were uniquely matched (Table S1).

FPKM statistical analysis was performed to calculate the gene expression levels. Unigenes with the threshold of FPKM > 5 in at least one sample were selected for further research. Therefore, a total of 30,316 known high confidence (HC) genes were obtained. According to the criteria of P-value ≤ 0.05 and |log2Ratio| ≥ 1, 14,437 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were found.

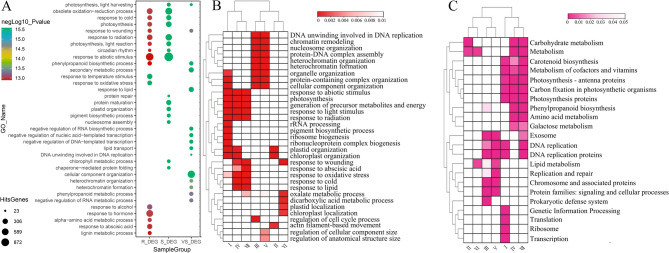

In total, 7519 DEGs for the resistance line X413 (R_DEGs) and 12,071 DEGs for the susceptible line X73 (S_DEGs) were identified. Among them, 1258 (16.7%) and 5810 (48.1%) genes were found to specifically differentially expressed in X413 and X73, respectively, suggested that most DEGs were shared by the two lines (Fig. 3A). To further investigate the differences between X413 and X73 in response to F. pseudograminearum, we compared their gene expression levels at each time point. The union of DEGs identified across all time points yielded a total of 5283 genes, which were designated as VS_DEGs (Fig. 3A). Venn diagram analysis of all DEGs (R_DEGs, S_DEGs and VS_DEGs) categorized them into seven distinct groups (I-VII) (Fig. 3A). Amond these, 1537 (group V) and 367 (group VI) VS_DEGs were found to also differentially expressed in X413 and X73, respectively, and 2271 genes in group VII were differentially expressed in both two lines (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Quantification and comparison of DEGs in X413, X73, and X413 vs. X73 comparative analysis. A Venn diagram depicting DEGs in X413, DEGs in X73, and DEGs identified from X413 vs. X73 comparison. B Number of DEGs in X413, X73, and X413 vs. X73 comparison across different stages. S_DEG, DEGs in X73; R_DEG, DEGs in X413; VS_DEG, DEGs in X413 vs. X73; UP, upregulated genes; DOWN, downregulated genes; I-VII, DEG groups classified by Venn diagram

Further, the total number of DEGs in X413 showed little difference (3576 ~ 3878 DEGs) in each time point (Fig. 3B). Additionally, except for a gap of about 400 between the number of up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs at 12 and 24 hpi, the number of different types of DEGs in X413 at each time point is close (Fig. 3B). In X73, the number of DEGs was much higher than that in X413, showing 4634 ~ 7172 DEGs in each time point (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the earlier the time point, the more differential genes were detected in X73 (Fig. 3B). In addition, most of the DEGs in X73 were down-regulated, especially at the point of 12, 24 and 48 hpi (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that X73 displayed a more sensitive responsion than X413 when infected with F. pseudograminearum. For VS_DEGs, X73 harbored more down-regulated genes at all 5 points. Additionally, small numbers of DEGs (~ 1000) were detected at 0, 24 and 72 hpi, whereas 2905 and 2510 DEGs appeared at 12 and 48 hpi, respectively, indicating the timelines 12 and 48 hpi might be critical for differences in resistance between X413 and X73 (Fig. 3B).

GO and KEGG analysis of DEGs

In order to get an overview for the gene functions in R_DEGs, S_DEGs and VS_DEGs, GO enrichment analysis was performed to classify the crucial biological processes. The top 15 significantly GO terms from each group were compared to detect the common and especial terms enriched during the infection by F. pseudograminearum. Seven terms were found to be shared by R_DEGs and S_DEGs enrichment, including “circadian rhythm”, “photosynthesis”, “response to abiotic stimulus” (Fig. 4A). The terms which especially identified in S_DEGs group were mainly related to the biogenesis of cellular components (like protein and pigment), including “pigment biosynthetic process”, “nucleosome assembly”, “protein maturation” (Fig. 4A). Whereas, we detected a significant enrichment for metabolic process and typical defense-related terms in R_DEGs group, including “alpha-amino acid metabolic process”, “lignin metabolic process”, “phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process”, “response to abscisic acid” (Fig. 4A). These especial GO terms in R_DEGs and S_DEGs groups might be associated with the resistance differences between the two lines. Additionally, the enrichment of VS_DEGs showed that the significantly GO terms were mainly related to negative regulation of transcription, DNA replication, lipid and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (Fig. 4A). GO terms like “secondary metabolic process”, “cellular component organization” and “response to wounding” were also enriched in this group (Fig. 4A). It is noteworthy that the GO terms “phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process” and “response to wounding” were not only significantly enriched in the VS_DEG group but also specifically enriched in the R_DEG group (Fig. 4A). This provides an important hypothesis that genes involved in these biological processes might be key components of the resistance mechanism in X413 to restrict pathogen colonization and spread.

Fig. 4.

Details of GO and KEGG enrichment analyses for DEGs. A Results of GO enrichment analysis for S_DEG, R_DEG, and VS_DEG, respectively. B GO enrichment analysis of DEG groups classified by Venn diagram. C KEGG enrichment analysis of DEG groups classified by Venn diagram. I-VII, DEG groups classified by Venn diagram in Fig. 3

Functional annotation of Venn-partitioned DEGs through GO enrichment analysis revealed group-specific biological processes (Figs. 3A and 4B). The X73-specific group I DEGs exhibited significant enrichment in photosynthesis-related processes, including “response to light stimulus”, “pigment biosynthetic process”, and “chloroplast organization” (Fig. 4B). Similarly, X413-specific DEGs (group II) shared the “chloroplast organization” term but uniquely featured “actin filament-based movement” (Fig. 4B). The shared DEGs between both materials (groups IV and VII) showed enrichment in similar biological processes, encompassing not only photosynthesis but also response pathways to various stimuli such as wounding and abscisic acid (ABA) (Fig. 4B). DEGs in group VI were significantly enriched in “oxalate metabolic process”, “chloroplast localization”, and “response to wounding” (Fig. 4B). Notably, the VS_DEGs shared as differentially expressed in X73 (groups III and V) were characterized by enrichment in nuclear regulatory processes, including “DNA unwinding involved in DNA replication,” “chromatin remodeling,” and “heterochromatin formation” (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the categorization of DEGs derived from KEGG analysis aligns congruently with the outcomes of the GO analysis (Fig. 4B-C). It is of particular significance that the DEGs in the VS_DEGs groups (groups III, V, and VII) are prominently enriched in pathways pertaining to DNA replication and post-replication repair (Fig. 4B-C). In summary, both X413 and X73 exhibit significant responses to F. pseudograminearum infection, with altered expression of stress-responsive genes. However, a key distinction is that fundamental growth-related processes in X73-including genomic maintenance (e.g., DNA replication, repair, and chromatin remodeling)-may be more significantly affected.

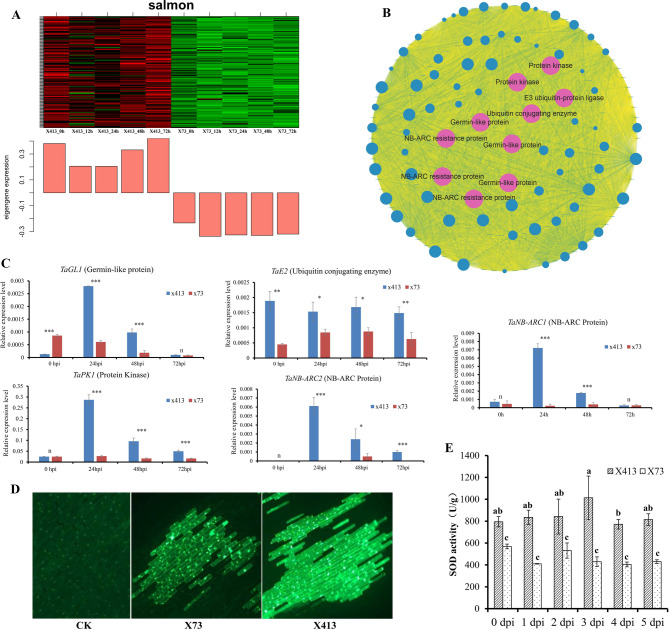

Gene expression network analysis using WGCNA

To more precisely compare the differences in the responses of two materials to F. pseudograminearum at the gene level, we conducted a WGCNA analysis on the differentially expressed genes (VS_DEGs) between them. A total of 5,283 DEGs were classified into 17 modules (excluding the MEgrey module) based on their expression patterns (Fig. 5A). The MEturquoise module contained the largest number of DEGs (940, approximately 17.8%). These genes exhibited higher expression levels in X413 than in X73 after F. pseudograminearum infection (Fig. 5A). Following that, the MEbrown (457) and MEyellow (455) modules had genes with higher expression levels in X73 (Fig. 5A). The MEgrey60 module had the fewest DEGs, with only 47 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, we classified these modules into two major categories according to the expression patterns of genes within them in X413 and X73 (Fig. 5A). The X413_up group comprised eight modules (e.g., MEblue, MEturquoise, and MEsalmon), whose DEGs showed higher or earlier expression in X413, while the X73_UP group consisted of modules with DEGs exhibiting higher or earlier expression in X73 (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

WGCNA of VS_DEGs and GO enrichment analysis of DEGs in X413_UP and X73_UP groups. A Co-expression modules generated by WGCNA. Numbers on the right indicate the number of genes in each module. X413_UP and X73_UP represent the classification of all modules into two major categories. B Detailed information of GO enrichment analysis for DEGs in X413_UP and X73_UP groups

Subsequently, we conducted GO and KEGG enrichment analyses on the DEGs of these two groups to preliminarily explore their functions. The results showed that the most significantly enriched biological processes of the DEGs in the X413_up group were basically related to the regulation at the chromatin level. This involved processes such as the “negative regulation of gene expression”, “DNA replication”, and “postreplication repair” (Fig. 5B). The most significantly enriched KEGG pathways were similar to the results of the GO enrichment analysis (Fig. S1). Additionally, there were some other pathways, such as “Lipid metabolism”, “Prokaryotic defense system”, and “Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis”, among others (Fig. S1). In contrast, the most significantly enriched biological processes of the DEGs in the X73_UP group were basically related to the responses to various stimuli (e.g., temperature, lipid and hormone) (Fig. 5B). The KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that the pathways these genes were involved in mainly related to the synthesis of defense-related secondary metabolites (such as flavonoids) (Fig. S1). Additionally, they covered the MAPK signaling pathway, energy metabolism, lipid metabolism, as well as various metabolic processes including carbon fixation, glutathione metabolism, and starch and sucrose metabolism (Fig. S1). This suggests that X413 maintains more stable growth and developmental capacity upon pathogen infection, whereas X73 appears to allocate more resources to the transcriptional regulation of a large number of stress-responsive genes.

Module analysis reveals potential mechanistic differences in FCR resistance between X413 and X73

Within the modules of the X413_up group, the MEturquoise and MEsalmon modules were selected for protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis and hub gene identification. The MEturquoise module harbored 940 genes, all of which were upregulated in X413 at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi (Figs. 5A and 6A). Based on the constructed PPI network, 47 hub genes, constituting 5% of the 940 genes, were pinpointed. Of these hub genes, 39 encoded histones, including 9 histone H2A, 13 histone H2B, 3 histone H3, and 14 histone H4 variants, which are fundamental for chromatin structure and gene regulation (Fig. 6B and Table S3). Five genes were involved in encoding proteins essential for DNA replication, while one gene functioned in DNA repair processes (Fig. 6B and Table S3). Additionally, one gene encoded a gibberellin-regulated protein, and another encoded a transcription factor (Fig. 6B and Table S3), both of which likely contribute to the complex regulatory mechanisms underlying the biological processes in X413. Subsequently, a subset of these genes was selected for qRT-PCR analysis. The results were consistent with the RNA-seq data, confirming the differences in their expression between X413 and X73 (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Hub genes in the MEturquoise module indicate that X413 maintains more stable growth and development after F. pseudograminearum inoculation. A Expression heatmap of genes in the MEturquoise module. B Expression network of hub genes in the MEturquoise module. C Expression levels of selected hub genes in X413 and X73 detected by qRT-PCR. Student’s t-test: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; N, not significant. D Three-leaf stage plants of X413 and X73 under inoculated and non-inoculated conditions. E Statistical analysis of plant height in X413 and X73 at the three-leaf stage under inoculated and non-inoculated conditions

The identification of numerous histone genes, replication-related genes, and post-replication DNA repair-related genes in this module suggests that X413 and X73 may differ in their cell division and growth capacities in response to F. pseudograminearum infection (Fig. 6B and Table S3). Therefore, we measured the plant heights of X413 and X73 with and without F. pseudograminearum inoculation. The results showed no significant difference in plant height between the two materials when not inoculated; however, after inoculation, X413 exhibited a significantly greater plant height (Fig. 6D-E). These results imply that X413 displays more stable growth characteristics than X73 under the stress of F. pseudograminearum infection.

The MEsalmon module contains a total of 145 DEGs (Fig. 5A). These genes exhibited higher expression levels in X413 at various time points following the inoculation with F. pseudograminearum compared to those in X73 (Figs. 5A and 7A). Among them, 30 genes demonstrated the highest connectivity (with a connectivity value of 143) and were identified as candidate members of hub genes. Further analysis of the 30 candidate hub genes showed a diverse gene composition. Specifically, there were three genes coding for NB-ARC domain resistance proteins (Fig. 7B and Table S4), which are important in plant defense responses. Another three code for Germin-like proteins involved in stress responses (Fig. 7B and Table S4). Two genes are responsible for protein kinases that play key roles in cellular signaling (Fig. 7B and Table S4). Moreover, two genes participate in ubiquitination: one encodes an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme for ubiquitin transfer, and the other an E3 ubiquitin ligase for target-protein recognition (Fig. 7B and Table S4). The expression levels of these genes in X413 and X73 following F. pseudograminearum infection were also validated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 7C). These genes are highly likely to play a pivotal role in the process of X413’s resistance to FCR and are significantly associated with the disease resistance characteristics of this material.

Fig. 7.

Hub genes in the MEsalmon module indicate that X413 exhibits a more prompt reactive ROS scavenging system. A Expression heatmap of genes within the MEsalmon module. B Co-expression network of hub genes in the MEsalmon module. C Validation of expression levels of selected hub genes in X413 and X73 via qRT-PCR. Student’s t-test: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; N, not significant. D Hydrogen peroxide accumulation assay in X413 and X73 at 5 dpi with F. pseudograminearum. E SOD activity in X413 and X73 at various time points following F. pseudograminearum inoculation

Germin-like proteins have been reported to possess SOD activity, which catalyzes the conversion of superoxide anion radicals to H₂O₂, thereby reducing free radical-induced damage to cells [45]. The presence of three Germin-like protein genes among the hub genes in this module prompted us to detect the H₂O₂ in X413 and X73 after F. pseudograminearum inoculation. The results showed that X413 exhibited a significantly stronger H₂O₂ fluorescent signal at 3 dpi with F. pseudograminearum (Fig. 7D). Further determination of SOD activity revealed that X413 had significantly higher SOD activity than X73 at all time points after inoculation (Fig. 7E). These results might indicate that X413 could possess a relatively timely and efficient reactive oxygen species (ROS) burst and scavenging system in comparison to X73.

Discussion

X413 and X73 May provide material basis for wheat breeding for FCR resistance

In recent years, FCR has emerged as a globally significant disease severely threatening the stability of wheat production [4, 23]. Due to the complexity of this disease and the polygenic control of resistance, screening for more germplasms with enhanced resistance could greatly facilitate the genetic improvement of FCR resistance. Worldwide, researchers have made substantial efforts to identify wheat germplasms exhibiting stable resistance to FCR [10–12, 15, 19, 46, 47]. However, the existing results are less than satisfactory: most germplasms evaluated for FCR resistance show susceptibility or high susceptibility, with only a small proportion displaying moderate resistance. For instance, Bhatta et al. (2019) assessed 125 synthetic hexaploid wheats (SHWs) for FCR resistance and initially identified 1 resistant and 12 moderately resistant germplasms [47]. Similarly, Yang et al. (2019) found that among 234 tested wheat cultivars, only 7 had a DI below 30, while over 97% were susceptible to FCR [10]. In Li et al. (2024), merely 7 out of 223 germplasms showed a DI less than 40 [15]. Therefore, acquiring FCR-resistant germplasms through diverse approaches has become a critical foundation for FCR-resistant breeding.

Mutagens such as EMS offer additional possibilities for generating new wheat germplasms with desirable traits [22]. Recent studies have demonstrated that wheat mutants can exhibit multiple improved agronomic traits, including FCR resistance [27, 48–50]. In this study, evaluation of FCR resistance in EMS-induced mutants of AK58 revealed that only a small percentage (10.19%) showed moderate resistance (Fig. 1A and Table S1). Nevertheless, we obtained a stably resistant germplasm X413 with a relatively low disease index. This germplasm can stably resist infection by multiple strains of F. pseudograminearum, and its resistance may be manifested in inhibiting the expansion and mycelial growth of the pathogen (Figs. 1 and 2). Notably, X413 exhibited a lower white head rate than the control in diseased wheat fields (Fig. 2D-E), suggesting it may also possess better adult-stage FCR resistance. In fact, FCR resistance in wheat differs between the seedling and adult stages. Previous studies have reported discrepancies in FCR resistance detected at these two stages [6, 16, 23]. For example, QTLs on 1AS, 1BS, and 4BS in 2–49, and on 2BS in Sunco, were detected at both the seedling stage and in field (adult stage) evaluations, whereas the QTL on 1DL in 2–49 and on 3BL in IRN 497 were only detected at the seedling stage [6].

Therefore, we hypothesize that the dual resistance of X413 to FCR at both seedling and adult stages may provide an excellent material foundation for wheat FCR-resistant breeding. Meanwhile, the highly susceptible germplasms identified in this study (e.g., X73) also offer a critical premise for exploring resistance/susceptibility-related genes to FCR, starting from the dissection of susceptibility mechanisms. However, whether these germplasms can stably maintain such FCR resistance/susceptibility across multiple environments requires further verification. Additionally, the dissection of their resistance/susceptibility mechanisms remains insufficiently in-depth, meaning the path for their future application in breeding practices still needs to be explored.

X413 and X73 exhibit significant differences in response to F. pseudograminearum

Transcriptomic analysis serves as a powerful tool for dissecting resistance/susceptibility mechanisms and unraveling resistance differences among germplasms [51, 52]. In this study, comparative transcriptome profiling of two EMS-induced mutants (moderately resistant X413 and highly susceptible X73) under F. pseudograminearum infection revealed dynamic molecular responses underlying their distinct FCR resistance phenotypes. Consistent with universal plant defense strategies, both X413 and X73 exhibited significant differential gene expression post-inoculation, with shared enrichment of DEGs in “abiotic stimulus response” and “wounding response” pathways (Figs. 3 and 4). This suggests conserved initial signaling cascades in perceiving pathogen invasion, which aligns with the fundamental premise of plant innate immunity [32, 34]. However, a striking contrast emerged in their transcriptional regulation patterns: X413 maintained fewer DEGs across all time points, whereas X73 displayed persistently higher DEG abundance (Fig. 3). This “low DEG-high resistance” pattern echoes findings in other pathosystems, such as Magnaporthe oryzae-rice and Erwinia amylovora-pear interactions, where resistant genotypes consistently show more constrained transcriptional reprogramming [53–55]. Such precision in X413 may reflect an optimized defense network that minimizes non-specific responses, whereas the excessive DEGs in X73 likely indicate dysregulated signaling-potentially due to loss of key regulatory nodes that normally constrain unnecessary stress responses [55].

Functional annotation further highlighted mechanistic divergence: X413’s DEGs were enriched in specialized resistance pathways, including “lignin metabolism” and “phenylpropanoid biosynthesis” (Fig. 4). The latter, critical for synthesizing cell wall reinforcements (lignin) and phytoalexins [30, 56, 57], likely contributes to X413’s ability to restrict pathogen spread (Fig. 2B-C). In contrast, X73’s DEGs were biased toward basal cellular biosynthesis, with downregulation of DNA replication/repair genes (Figs. 4 and 5). Coupled with its stunted growth following inoculation (Fig. 6D-E), this might suggest that X73 tends to prioritize stress responses at the expense of growth resources, potentially resulting in metabolic imbalance—a characteristic often observed in susceptible genotypes.

Collectively, our findings might lend support to a model where X413’s resistance could stem from the efficient activation of targeted defense pathways while maintaining growth-defense homeostasis, whereas X73’s susceptibility may arise from regulatory irregularities and a tendency toward over-allocation of resources to non-adaptive stress responses. However, it should be acknowledged that the above speculations require more comprehensive research in the future to provide substantial corroboration.

Regulation of ROS homeostasis may be one of the factors contributing to FCR resistance of X413

WGCNA, a robust tool for unraveling trait-associated gene modules and mining functional candidates in plant biology [42, 58], was leveraged to explore the molecular underpinnings of divergent FCR resistance between X413 and X73. A key finding from hub gene characterization in the MEsalmon module was the identification of three germin-like protein (GLP) genes (Fig. 7A-B), which emerged as potential drivers of resistance [45].

ROS dynamics-encompassing both rapid burst and subsequent homeostasis-are well-recognized as central to plant immune responses against pathogens [4]. While studies consistently report ROS level disparities between resistant and susceptible genotypes post-inoculation, resistance cannot be reduced to a simple correlation with ROS abundance alone. Instead, a critical hallmark of resistant germplasms lies in their enhanced capacity to regulate ROS via elevated scavenging enzyme activity, balancing defensive signaling with protection against oxidative damage [45, 59]. Germin-like proteins are functionally distinguished by their intrinsic SOD activity, catalyzing the conversion of superoxide anions to H₂O₂ and thus acting as pivotal regulators of ROS homeostasis during biotic stress [45, 60]. This role is supported by precedent: for example, the cotton GLP gene GhABP19 reinforces resistance to Verticillium and Fusarium wilt through positive modulation of defense pathways [60], while rice OsGLP3-7 bolsters immunity against multiple pathogens, with its overexpression conferring enhanced resistance to leaf blast, panicle blast, and bacterial blight [45].

In line with this mechanistic framework, our observations revealed that X413 accumulated higher H₂O₂ levels and maintained significantly elevated SOD activity relative to X73 across all post-inoculation time points (Fig. 7D-E). These findings might tentatively suggest that X413 appears to deploy a coordinated ROS-mediated defense strategy: a robust initial ROS burst to amplify immune signaling, coupled with a relatively rapid upregulation of ROS-scavenging machinery (which may be driven by the identified GLP genes) to help prevent unchecked oxidative stress. This balance between activation and regulation stands in contrast to the seemingly less efficient ROS management observed in X73, which could potentially contribute to its susceptibility. Beyond GLPs, other hub genes in the MEsalmon module hint at additional layers of resistance in X413, underscoring the complexity of FCR defense and opening avenues for further exploration into complementary resistance pathways.

Conclusion

In this study, an EMS-mutagenized population was developed from the wheat cultivar AK58. Through systematic evaluation of FCR resistance in these mutants, we identified X413 as a germplasm exhibiting stably moderate resistance at both the seedling and adult stages. Compared with the wild-type AK58 and highly susceptible X73, X413 exhibited stronger inhibitory capacity against the expansion and mycelial growth of F. pseudograminearum. RNA-seq analysis revealed that X413 displayed a more stable gene expression pattern under pathogen infection, with fewer DEGs. Its unique DEGs were significantly enriched in resistance-related biological processes such as “lignin metabolism” and “phenylpropanoid biosynthesis”. Physiological assays showed that X413 had higher hydrogen peroxide content and SOD activity than X73. In contrast, the highly susceptible X73 had more DEGs, with significantly downregulated expression of genes related to growth and development (e.g., DNA replication and post-replication repair), may leading to an imbalance between growth and defense metabolism and ultimately resulting in a susceptible phenotype. These findings provide valuable germplasm resources and theoretical basis for wheat breeding against FCR.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the colleagues in our laboratory who provided helpful advice and technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- CMC

Carboxymethyl cellulose

- DEG

Differentially expressed gene

- DI

Disease index

- dpi

Days post-inoculation

- FCR

Fusarium crown rot

- GLP

Germin-like protein

- hpi

Hours post-inoculation

- PDA

Potato dextrose agar

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- WGCNA

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

Authors’ contributions

HH and CL designed the research program. MZ, DL, LG and MH analyzed the data. MZ, GL, EC, LZ, XS, XW and HD revised the language and collected the data. MZ performed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171995), and the Key Scientific and Technological Research Projects in Henan Province (252102111123, 222102110441 and 222102110030).

Data availability

The reads files of this study are accessible from the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB) database under Accession Number PRJCA043402.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Meng Zhang and Dongmei Li have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Chunji Liu, Email: Chunjiliu1@gmail.com.

Haiyan Hu, Email: haiyanhuhhy@126.com.

References

- 1.Liu X, Wang D, Zhang Z, Lin X, Xiao J. Epigenetic perspectives on wheat speciation, adaptation, and development. Trends Genet. 2025;41(9):817-29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Xiao J, Liu B, Yao Y, Guo Z, Jia H, Kong L, et al. Wheat genomic study for genetic improvement of traits in China. Sci China Life Sci. 2022;65(9):1718–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li HL, Yuan HX, Fu B, Xing XP, Sun BJ, Tang WH. First report of Fusarium pseudograminearum causing crown rot of wheat in Henan, China. Plant Dis. 2012;96(7):1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X, Zhang L, Wei J, Liu L, Liu D, Yan X, Yuan M, Zhang L, Zhang N, Ren Y, et al. A TaSnRK1α-TaCAT2 model mediates resistance to Fusarium crown rot by scavenging ROS in common wheat. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bovill WD, Horne M, Herde D, Davis M, Wildermuth GB, Sutherland MW. Pyramiding QTL increases seedling resistance to crown rot (Fusarium pseudograminearum) of wheat (Triticum aestivum). Theor Appl Genet. 2010;121(1):127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin A, Bovill WD, Percy CD, Herde D, Fletcher S, Kelly A, et al. Markers for seedling and adult plant crown rot resistance in four partially resistant bread wheat sources. Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128(3):377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Z, Kilian A, Yan G, Liu C. QTL conferring Fusarium crown rot resistance in the elite bread wheat variety EGA Wylie. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e96011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J, Li HB, Zhang CY, Yang XM, Liu YX, Yan GJ, et al. Identification and validation of a major QTL conferring crown rot resistance in hexaploid wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2010;120(6):1119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Z, Ma J, Stiller J, Zhao Q, Feng Q, Choulet F, et al. Fine mapping of a large-effect QTL conferring Fusarium crown rot resistance on the long arm of chromosome 3B in hexaploid wheat. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X, Pan Y, Singh PK, He X, Ren Y, Zhao L, et al. Investigation and genome-wide association study for Fusarium crown rot resistance in Chinese common wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin J, Duan S, Qi Y, Yan S, Li W, Li B, et al. Identification of a novel genomic region associated with resistance to Fusarium crown rot in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133(7):2063–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi S, Zhao J, Pu L, Sun D, Han D, Li C, et al. Identification of new sources of resistance to crown rot and Fusarium head blight in wheat. Plant Dis. 2020;104(7):1979–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pu L, Goher F, Zeng M, Wu D, Zeng Q, Han D, et al. Source identification and genome-wide association analysis of crown rot resistance in wheat. Plants. 2022;11(15):1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Dong Q, Liu Q, Goodwin PH, Deng X, Xu W, Xia M, Zhang J, Sun R, Wu C, Wang Q et al. Isolation and genome-based characterization of biocontrol potential of Bacillus siamensis YB-1631 against wheat crown rot caused by Fusarium pseudograminearum. J Fungi (Basel). 2023;9(5):547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Li J, Zhai S, Xu X, Su Y, Yu J, Gao Y, et al. Dissecting the genetic basis of Fusarium crown rot resistance in wheat by genome wide association study. Theor Appl Genet. 2024;137(2):43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Poole GJ, Smiley RW, Paulitz TC, Walker CA, Carter AH, See DR, et al. Identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL) for resistance to Fusarium crown rot (Fusarium pseudograminearum) in multiple assay environments in the Pacific Northwestern US. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125(1):91–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C, Ogbonnaya FC, Bürstmayr H. Resistance to Fusarium crown rot in wheat and barley: a review. Plant Breed. 2015;134(4):365–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang X, Zhong S, Zhang Q, Ren Y, Sun C, Chen F. A loss-of-function of the dirigent gene TaDIR-B1 improves resistance to Fusarium crown rot in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(5):866–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou S, Lin Y, Yu S, Yan N, Chen H, Shi H, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of Fusarium crown rot resistance in Chinese wheat landraces. Theor Appl Genet. 2023;136(5):101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lv G, Zhang Y, Ma L, Yan X, Yuan M, Chen J, et al. A cell wall invertase modulates resistance to Fusarium crown rot and sharp eyespot in common wheat. J Integr Plant Biol. 2023;65(7):1814-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Wang C, Sun M, Zhang P, Ren X, Zhao S, Li M, et al. Genome-wide association studies on Chinese wheat cultivars reveal a novel Fusarium crown rot resistance quantitative trait locus on chromosome 3BL. Plants. 2024;13(6):856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Xu X, Su Y, Yang J, Li J, Gao Y, Li C, et al. A novel QTL conferring Fusarium crown rot resistance on chromosome 2A in a wheat EMS mutant. Theor Appl Genet. 2024;137(2):49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Su Y, Xu X, Wang Y, Wang T, Yu J, Yang J, et al. Identification of genetic loci and candidate genes underlying Fusarium crown rot resistance in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2025;138(1):23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Sun S, Ge W, Zhao L, Hou B, Wang K, et al. Horizontal gene transfer of Fhb7 from fungus underlies Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Science. 2020;368(6493):eaba5435. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Chen JD, Lin T, Wang W, Jin C, Zuo JR, Nian JQ. Identification and gene mapping of hry1 mutant in rice. Yi Chuan. 2025;47(7):797–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Li X, Lu X. ZmRLCK1 modulates secondary cell wall deposition in maize. Plant J. 2025;123(1):e70313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q, Hao X, Guo Z, Qu K, Gao M, Song G, et al. Screening and resistance locus identification of the mutant fcrZ22 resistant to crown rot caused by Fusarium pseudograminearum. Plant Dis. 2024;108(2):426–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desmond OJ, Manners JM, Schenk PM, Maclean DJ, Kazan K. Gene expression analysis of the wheat response to infection by Fusarium pseudograminearum. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2008;73(1–3):40–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell JJ, Carere J, Fitzgerald TL, Stiller J, Covarelli L, Xu Q, Gubler F, Colgrave ML, Gardiner DM, Manners JM, et al. The Fusarium crown rot pathogen Fusarium pseudograminearum triggers a suite of transcriptional and metabolic changes in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Ann Bot. 2017;119(5):853–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan S, Jin J, Gao Y, Jin C, Mu J, Zhen W, et al. Integrated transcriptome and metabolite profiling highlights the role of benzoxazinoids in wheat resistance against Fusarium crown rot. Crop J. 2022;10(2):407–17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powell JJ, Fitzgerald TL, Stiller J, Berkman PJ, Gardiner DM, Manners JM, et al. The defence-associated transcriptome of hexaploid wheat displays homoeolog expression and induction bias. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15(4):533–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Wang Y, Guan F, Long L, Wang Y, Li H, et al. Comparative analysis of Fusarium crown rot resistance in synthetic hexaploid wheats and their parental genotypes. BMC Genomics. 2023;24(1):178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su ZY, Powell JJ, Gao S, Zhou M, Liu C. Comparing transcriptional responses to Fusarium crown rot in wheat and barley identified an important relationship between disease resistance and drought tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su Z, Gao S, Zheng Z, Stiller J, Hu S, McNeil MD, et al. Transcriptomic insights into shared responses to Fusarium crown rot infection and drought stresses in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Theor Appl Genet. 2024;137(2):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang P, Huo Y, Zhou M, Yao J, Ma H. Identification and evaluation of wheat germplasm resistance to crown rot caused by Fusarium graminearum. J Plant Genetic Resour. 2009;10(3):431–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. Stringtie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(3):290–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, stringtie and ballgown. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(9):1650–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5(7):621–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen C, Wu Y, Li J, Wang X, Zeng Z, Xu J, et al. TBtools-II: a one for all, all for one bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol Plant. 2023;16(11):1733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen T, Liu YX, Chen T, Yang M, Fan S, Shi M, et al. ImageGP 2 for enhanced data visualization and reproducible analysis in biomedical research. Imeta. 2024;3(5):e239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Meng B, Zhang Z, Wei L, Chang W, Wang Y, Zhang K, Li T, Lu K. qPrimerDB 2.0: an updated comprehensive gene-specific qPCR primer database for 1172 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(D1):D205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun B, Li W, Ma Y, Yu T, Huang W, Ding J, et al. OsGLP3-7 positively regulates rice immune response by activating hydrogen peroxide, jasmonic acid, and phytoalexin metabolic pathways. Mol Plant Pathol. 2023;24(3):248–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malosetti M, Zwep LB, Forrest K, van Eeuwijk FA, Dieters M. Lessons from a GWAS study of a wheat pre-breeding program: pyramiding resistance alleles to Fusarium crown rot. Theor Appl Genet. 2021;134(3):897–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhatta M, Morgounov A, Belamkar V, Wegulo SN, Dababat AA, Erginbas-Orakci G, et al. Genome-wide association study for multiple biotic stress resistance in synthetic hexaploid wheat. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(15):3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Li J, Xu X, Ma Y, Sun Q, Xie C, Ma J. An improved inoculation method to detect wheat and barley genotypes for resistance to Fusarium crown rot. Plant Dis. 2022;106(4):1122–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhong S, Yang H, Chen C, Ren T, Li Z, Tan F, et al. Phenotypic characterization of the wheat temperature-sensitive leaf color mutant and physical mapping of mutant gene by reduced-representation sequencing. Plant Sci. 2023;330:111657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bian R, Liu N, Xu Y, Su Z, Chai L, Bernardo A, et al. Quantitative trait loci for rolled leaf in a wheat EMS mutant from Jagger. Theor Appl Genet. 2023;136(3):52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen Y, Wang J, Shaw RK, Sheng X, Yu H, Branca F, et al. Comparative transcriptome and targeted metabolome profiling unravel the key role of phenylpropanoid and glucosinolate pathways in defense against Alternaria brassicicola in broccoli. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(16):6499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang T. Comparative transcriptome analysis identifies a positive regulator of wheat rust susceptibility that modulates amino acid metabolism. Plant Cell. 2021;33(5):1409–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Ye Y, Huan W, Ji J, Ma J, Sheng Q, et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis and candidate gene mining for fire blight of Pear resistance in Korla fragrant Pear (Pyrus sinkiangensis Yu). Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):15073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iqbal O, Yang X, Wang Z, Li D, Wen J, Ding J, et al. Comparative transcriptome and genome analysis between susceptible Zhefang rice variety Diantun 502 and its resistance variety Diantun 506 upon Magnaporthe oryzae infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2025;25(1):341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang D, Li S, Xiao Y, Lu L, Zheng Z, Tang D, et al. Transcriptome analysis of rice response to blast fungus identified core genes involved in immunity. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44(9):3103–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu X, Zhao Y, Shi CM, Xu G, Wang N, Zuo S, Ning Y, Kang H, Liu W, Wang R, et al. Antagonistic control of rice immunity against distinct pathogens by the two transcription modules via salicylic acid and jasmonic acid pathways. Dev Cell. 2024;59(12):1609–22. e1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu L, Zhu L, Tu L, Liu L, Yuan D, Jin L, et al. Lignin metabolism has a central role in the resistance of cotton to the wilt fungus Verticillium dahliae as revealed by RNA-seq-dependent transcriptional analysis and histochemistry. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(15):5607–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheng C, Song S, Zhou W, Dossou SSK, Zhou R, Zhang Y, et al. Integrating transcriptome and phytohormones analysis provided insights into plant height development in sesame. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;198:107695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, Zhang X, Zhang W, Peng M, Tan G, Qaseem MF, et al. Physiological and transcriptomic responses to magnesium deficiency in Neolamarckia cadamba. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;197:107645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pei Y, Li X, Zhu Y, Ge X, Sun Y, Liu N, et al. GhABP19, a novel germin-like protein from Gossypium hirsutum, plays an important role in the regulation of resistance to Verticillium and Fusarium wilt pathogens. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The reads files of this study are accessible from the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB) database under Accession Number PRJCA043402.