Abstract

Microorganisms play a significant role in improving the flavor and quality of plant products. Analyzing how tobacco processing affects the microbial community structure is essential. Understanding the synergistic mechanisms of microorganisms during this process can help optimize the flavor and quality of plant products. In this study, samples were collected from four processing stages (T1: fresh leaves, T2: 42 °C, T3: 54 °C, T4: 68 °C), and metabolite and Phylloplane microbial data of tobacco leaves were generated. A comprehensive multi-omics analysis was conducted. The study shows that the increase in temperature and the decrease in humidity during the processing lead to the reorganization of the microbial community. Brevibacterium, Staphylococcus, Aspergillus, and Ganoderma were identified as core biomarkers. Bacteria dominate in the initial degradation of starch, while fungi promote the accumulation of soluble sugars through the transformation of intermediate products. This study deepens our understanding of the role of microorganisms and their carbohydrate metabolism in the tobacco leaf processing process and proposes a new strategy for constructing regulatory models by integrating multi-omics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00248-025-02644-8.

Keywords: Microbial community, Tobacco processing, Metabolomes, Metabolic pathways, Multi-omics analysis

Introduction

Starch-based natural organic compounds, as sustainable and renewable resources [1], play a critical role in the global carbon cycle and energy supply. These compounds constitute a significant portion of Earth’s biomass, primarily produced by plants [2]. In the field of plant processing, the role of microorganisms is particularly important, as they can secrete various enzymes [3], such as amylase [4] and cellulase [5], which can efficiently degrade the macromolecular substances in plant tissues into easily absorbed metabolic products [5], significantly affecting the nutritional and flavor quality of crops such as grains [6], vegetables [7, 8], fruits [9], and tea [10, 11]. For example, in the processing of tea and certain specific crops, microorganisms promote the formation and accumulation of aromatic compounds by secreting phenol oxidase and peroxidase enzymes [12, 13]. When considering the processing of plant leaves, especially plant-based products, special attention is paid to the role of microorganisms in degrading complex macromolecular substances such as starch, which are not only important nutrient sources for microorganisms but also profoundly affect the final characteristics of processed products [14].

Starch, a recalcitrant component in plant leaves, is significantly affected by processing environmental conditions [15]. Under specific environmental regimes, microbial communities facilitate the efficient hydrolysis of starch macromolecules through the secretion of specialized enzymes. For instance, Bacillus—a widely recognized functional microbial group—possesses α-amylase activity, enabling starch breakdown. This hydrolysis yields reducing sugars, total sugars, and various intermediate products [14, 16], which are subsequently converted into volatile aroma compounds such as alcohols, aldehydes, acids, and esters [17, 18]. This process not only enriches the flavor of the product but also promotes the complex interaction between plant-microbial micro-ecosystems.

In recent years, studies have revealed the dynamic changes in the microbial community during plant leaf processing, but most of them have focused on the description of community structure rather than functional analysis [19]. In particular, the specific role mechanisms of core microorganisms in degrading starch and other macromolecular substances are not yet clear [20]. Therefore, it is of great significance to explore the functions of these key microorganisms in depth and clarify their contributions to macromolecule degradation, which can optimize processing technology and improve product quality.

Plants actively construct complex Phylloplane microbial consorts during processing [21], these microorganisms closely interact with metabolites on the surface of plant leaves to jointly respond to the multiple challenges posed by the processing environment [22]. In this study, we analyzed the changes in microbial communities and metabolic functional pathways during the processing of tobacco leaves, revealed the metabolic potential of microbial communities, and explored the close relationship between microbial communities and metabolic processes during the processing, especially the potential cooperative mechanisms of microbial communities in starch degradation. The model research on exploring the interaction patterns between microbial communities and metabolites provided a new perspective for understanding the complex mechanism of microbial co-degradation of starch during the processing. In summary, this study aimed to reveal the synergistic degradation effect of tobacco processing microorganisms on starch, thereby better understanding the metabolic situation during the tobacco processing process and promoting the improvement of tobacco processing technology. This study aims to systematically elucidate the mechanisms underlying microbe-driven carbohydrate metabolism during tobacco processing, with a focus on the following scientific questions: (1) To analyze the dynamic reorganization patterns of the phyllosphere microbial community throughout the processing stages. (2) To identify core microbial biomarkers that play key roles during the processing. (3) To uncover critical metabolic pathways and compound changes involved in starch degradation and soluble sugar accumulation. (4) To investigate the synergistic mechanisms between microbial communities and metabolic processes.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Processing

In August 2022, tobacco leaves (Nicotiana tabacum L., variety ‘Yunyan 87’) were collected from Fuquan City, Guizhou Province (107°14′ E, 27°02′ N) as experimental materials. During the processing procedure, a total of 4 sampling points were set up, and the temperature and relative humidity data at each sampling point were recorded. (T1: 27 °C, 79%; Fresh leaves; 0 h. T2: 42 °C, 67%; Yellowing stage; 72 h. T3: 54 °C, 22%; Leaf-drying stage; 120 h. T4: 68 °C, 7%; Stem-drying stage; 168 h) (Table. S1). At each stage, we used temperature and humidity controllers to adjust the sampling points to match the processing conditions. These conditions were maintained for a set period to ensure environmental stability. Meanwhile, during sample collection, the temperature and humidity at each collection time were recorded. The untreated leaves (T1) were used as the control to evaluate the effects of different temperature and relative humidity conditions during the processing on the microbial community and metabolites. At each sampling point, three biological replicates were collected for each sample, totaling 12 biological replicates. The dry bulb temperature and wet bulb temperature were recorded at each sampling time.

Organic Compound Measurement

The collected samples were ground into powder. Approximately 0.1 g of sample was added to 1 mL of 80% ethanol for thorough homogenization. The samples were extracted at 80 °C in a water bath for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm at room temperature for 5 min. The starch content was determined using the Solarbio assay kit (Beijing, China). The contents of sucrose, maltose, D-glucose, and D-fructose were determined according to previous studies using GC-MS [23].

Leaf Surface Microbial Washing and Enrichment

Place approximately 20 g of fresh leaf samples or 5–10 g of dry leaf samples in a 500 mL conical flask, add 250 mL of 1% sterile PBS buffer solution, and collect microorganisms on the leaves by shaking the conical flask and centrifuging to wash off the liquid. After centrifugation, discard the supernatant and place the coarse precipitate in a −80 °C freezer for subsequent sequencing work to proceed normally [19].

DNA Extraction and Illumina Mi-Seq Sequencing

DNA was extracted using the SDS method, and then agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to check the purity and concentration of the genomic DNA. 30ng of high-quality genomic DNA samples and corresponding fusion primers were used to configure the PCR reaction system [19], and the V5-V7 variable region was amplified using specific primers. The bacterial 16 S rRNA gene was amplified using the 799 F-1193R (AACMGGATTAGATACCCKG-ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC) primers [24]. PCR was performed using Phusion® High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix and GC Buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) with high-fidelity and high-efficiency enzymes [19]. The Ribosomal Database Project library was constructed. The fragment range and concentration of the library were detected using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The qualified library was sequenced based on the size of the inserted fragment. The ITS1F and ITS2R primers were used to amplify the fungal ITS gene [25], except for the annealing temperature of 55 °C and 35 cycles, the PCR conditions were the same as those of the 16 S rRNA gene [26].

Leaf Surface Microbial Metabarcoding Sequencing Data Analysis

The target DNA fragments were extracted from the sequencing reads by removing the primer sequence and adapter using cutadapt v2.6 [27]. The data was filtered by setting the window length to 25 bp, and all low-quality windows were processed starting from the position where the average quality value was less than 20. Additionally, all reads with a final length reduced to 75% or less of the original read length were excluded, as well as readings containing unknown base N and low complexity readings (such as sequences with 10 consecutive identical bases). The reads were efficiently assembled into long sequences using FLASH v1.2.11 [28] based on the overlapping regions (the minimum matching length was set to 15 bp, and an error rate of 0.1 was allowed). Pairs of reads were assembled into a single long sequence to improve the sequence’s completeness and accuracy. Sequence clustering was performed using the UPARSE algorithm in USEARCH v7.0.1090_i86linux32 at a similarity threshold of 97%, which identified representative operational taxonomic units (OUTs) sequences [29]. Subsequently, UCHIME v4.2.40 was used to remove chimeric sequences that may have arisen from PCR amplification, and all processed tags were compared back to the OTU representative sequences using usearch_global, generating a comprehensive OTU abundance statistics Table [30]. The taxonomic affiliation of each OTU was clarified by setting the confidence threshold to 0.6, and the OTU representative sequences were compared to the corresponding databases (16 S used gold database v20110519 [31], ITS used UNITE v201407 03 [32]). After that, all OTUs that could not be successfully annotated were removed.

Metabolite Measurement

Weigh 50 µg of sample into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and soak them in 800 µL of precooled extraction solution (methanol: H2O = 7:3, v/v) and 20 µL of internal standard 1 (IS1). Homogenize the samples at 50 Hz for 10 min using a woven grinding machine, then sonicate them in a water bath at 4 °C for 30 min. Allow the extracts to stand at −20 °C for 1 h, then centrifuge them at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Filter 600 µL of the supernatant using a 0.22 μm membrane and mix 20 µL of the filtered solution from each sample with the quality control (QC) sample to evaluate the repeatability and stability of the LC/MS analysis. Transfer the filtered samples and the mixed QC samples to 1.5 mL sample vials for instrument operation. Use a Hypersil GOLD aQ Dim column (1.9 μm, 2.1*100 mm, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for metabolite determination. The mobile phase is a water solution containing 0.1% formic acid (A liquid) and an acetonitrile solution containing 0.1% formic acid (B liquid) that is eluted using the following gradient: 0–2 min, 5% B liquid; 2–22 min, 5%−95% B liquid; 22–27 min, 95% B liquid; 27–27.1 min, 95% B liquid-5% B liquid; 27.1–2.7 min, 5% B liquid. The flow rate is 0.3 mL/min, the column temperature is 40 °C, and the injection volume is 5 µL [33].

The downstream data from mass spectrometry is imported into Compound Discoverer 3.3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) software, combined with the BMDB (Huadai Metabolome Database, BGI Metabolome Database), mzCloud database, and ChemSpider online database for mass spectrometry data analysis, which will result in a data matrix containing information such as metabolite peak areas and identification results. After that, the table will be further processed for information analysis. The metaX software is used to preprocess the exported data, and detailed information annotation of metabolites is performed using authoritative databases such as KEGG and HMDB, including KEGG ID, HMDB ID, classification information, and participation in KEGG metabolic pathways [34].

Statistical Analysis

All calculations and statistical analyses were conducted in R Studio (v.4.4.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Utilize the ggplot2 package ggplot2 package (v3.5.1) to create bar plots and apply Tukey’s HSD test for significance analysis of differences between groups [35]. Microbial community diversity was assessed by calculating α-diversity indices. Similarity analysis was performed based on Bray-Curtis distance. Significant differences between groups were determined using Duncan’s new multiple range test (p < 0.05). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was conducted, and between-group differences were tested using PERMANOVA. Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was carried out using the “ropls” package (v1.38.0) [36], and the validity of the model was verified through 200 permutation tests. The Venn diagram was used with the “VennDiagram” package (v1.7.3) [37]. Normality of biomarker abundance data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the results indicated a non-normal distribution. Subsequently, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was applied to perform correlation analysis based on z-score normalized metabolite data. A heatmap visualizing the correlations between biomarkers and macromolecular compounds was generated using the R package pheatmap (v1.0.12) [38], with a p-value less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. Furthermore, PICRUSt2 (v2.5.1) was employed to predict the functional potential of the bacterial communities, yielding abundance data of relevant enzymes [39]. After z-score normalization of the enzyme abundance data, Spearman’s correlation analysis was similarly conducted alongside the pheatmap package (v1.0.12) to generate correlation heatmaps, with p-values less than 0.05 deemed statistically significant [38]. Random forest was used to establish prediction models and identify biomarkers. Differential metabolite analysis was conducted using the BGI Dr. Tom multi-omics analysis platform [https://biosys.bgi.com//report/login]. KEGG enrichment analysis was conducted using the Omicshare Genomics Bioinformatics Cloud Platform (https://www.omicshare.com).

Results

Generation of Processed Tobacco Microbiome and Metabolomics Resources

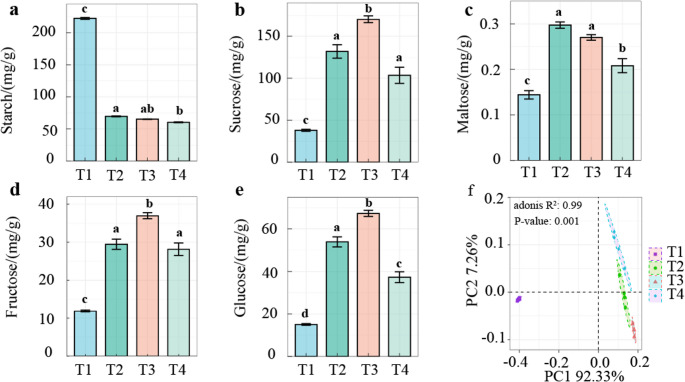

Both 16 S rRNA sequencing and ITS sequencing were conducted to analyze tobacco Phylloplane microorganisms. A comparative analysis of metabolites in tobacco leaves at various processing stages reveals the degradation of starch macromolecules alongside the accumulation of sucrose and glucose small molecules during leaf processing, which is crucial for determining the quality of processed tobacco products. GC-MS and starch measurements showed that starch content was highest at T1. There was no significant difference between T2 and T4 (Fig. 1a). Conversely, the concentrations of sucrose, maltose, fructose, and glucose at T1 were lower than those at T2, T3, and T4 (Fig. 1b, c, d, e). Notably, the concentrations of sucrose, fructose and glucose at the T3 stage were significantly higher than those at all other stages. The impact of processing stage on compound content variation is more pronounced than self-conversion among compounds (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

Compound contents and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) across different stages. (a) Bar plot of starch content at different stages. (b) Bar plot of sucrose content at different stages. (c) Bar plot of maltose content at different stages. (d) Bar plot of fructose content at different stages. (e) Bar plot of glucose content at different stages. (f) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of different compounds. Different letters above the bar plots indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level according to Tukey’s HSD test

We conducted qualitative and quantitative metabolomic analyses to determine if metabolic changes in tobacco showed consistent patterns across processing stages. Following normalization and data correction, compounds with relative peak areas exceeding 30% were excluded from all quality control (QC) samples, resulting in a total of 41,628 metabolites identified from 16 samples. Through 16 S rRNA sequencing, we obtained a total of 1,108,954 high-quality reads and identified 7,710 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) from the same set of tobacco leaf samples. Additionally, ITS sequencing yielded a total of 1,436,843 high-quality reads and identified 8,641 OTUs from these tobacco leaf samples.

Microbial Communities Are Affected by the Course of Working

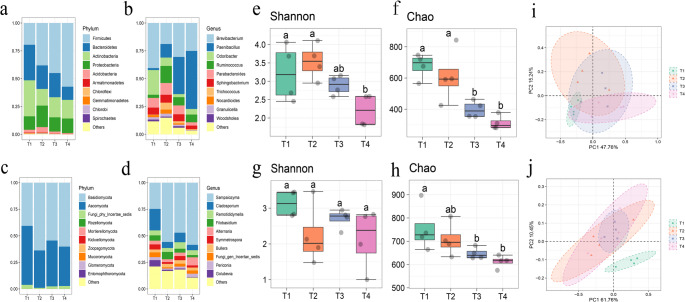

To gain a deeper understanding of how processing influences changes in microbial communities, we analyzed the relative abundance of bacteria and fungi at both phylum and genus levels. The bacterial community during processing was predominantly composed of Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. Notably, the abundance of Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes exhibited a gradual decline throughout the process, whereas that of Firmicutes showed an increasing trend (Fig. 2a). At the genus level, Brevibacterium emerged as the dominant genus, followed by Paenibacillus and Odoribacter. Specifically, Paenibacillus species were most prevalent at T4(Fig. 2b). In terms of fungal communities, Basidiomycota represented the dominant phylum, succeeded by Ascomycota (Fig. 2c). At the genus level within fungi, Sampaiozyma was identified as the predominant genus with Cladosporium following closely behind (Fig. 2d). Importantly, bacterial communities demonstrate greater responsiveness to processing compared to their fungal counterparts.

Fig. 2.

Microbial communities were affected by processing. phylum and genus level species accumulation histogram of (a), (b) 16 S rDNA and (c), (d) ITS sequenced samples. alpha diversity boxplot and wilcox test of (e), (f) 16 S rDNA and (g), (h) ITS sequenced samples. Principal coordinate analysis of (i) 16 S rDNA and (j) ITS sequencing samples (PCoA analysis). Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level according to Duncan’s new multiple range test

We further evaluated the effects of processing on microbial communities further; we assessed alterations in both structure and composition through alpha diversity metrics. The Shannon diversity index for bacteria peaked at T1 but significantly decreased by T4 (Fig. 2e and Fig. S1a and Table. S3, p < 0.05). In contrast, fungal community diversity experienced some reduction without significant change overall (Fig. 2g and Fig. S1b and Table. S2, p < 0.05). Both Chao1 and ACE richness indices for bacteria were highest at T1 but also showed significant declines by T4 (Fig. 2f and Fig. S1c and Table. S3, p < 0.05). Similarly, fungal community richness displayed a comparable trend with significant decreases noted (Fig. 2h and Fig. S1d and Table. S2, p < 0.05). Our findings indicate processing induced shifts in both structure and diversity within tobacco Phylloplane microbial communities that were induced by processing.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed that PCo1 and PCo2 axes accounted for 60.37% of variation in bacterial community composition (Fig. 2i) and 70.18% in fungal community composition respectively (Fig. 2j). In the four stages of bacteria, no significant separation was observed in the community composition; however, there was a significant difference between T1 and the other three stages (Table. S4, p < 0.05). The fungal community composition was significantly separated and different between T1 and the other three stages (Table. S5, p < 0.05). The community composition of bacteria and fungi in T2, T3, and T4 remained relatively similar throughout the treatment process (Table. S4 and S5).

Comparative Analysis of Key Microorganisms in Various Processing Stages

Different processing stages selectively recruited specific groups of bacterial and fungal microorganisms on the surfaces of tobacco leaves. Utilizing a machine learning approach based on the random forest algorithm, this study identified various bacterial species present at the leaf margins across different processing stages and quantified the influence of individual bacterial species on observed variations at each node within the classification tree. The findings revealed distinct genus signatures among the top 40 leaf-associated microorganisms, reflecting recruitment patterns of both bacterial and fungal communities during different processing stages. Notably, the bacterial community exhibited greater enrichment on T2 leaves, including genera such as Alcaligenes, Virgibacillus, Oceanobacillus, Nocardiopsis, Saccharopolyspora, Mycobacterium, Streptomyces, Pseudonocardia, Georgenia, and Brevundimonas (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the fungal community was more abundant in T1 leaves with notable genera including Eutypella, Hyphodontia, Dissoconium, Rhizoctonia, Cladosporium, Phomatospora, Alishanica, Ganoderma, Pseudopithomyces, Rachicladosporium, Acremonium, Wallemia, Aspergillus, Microascus, and Scopulariopsis (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Acquisition of biomarkers at different processing stages. calculate the biological identifiers for 16 S rDNA sequencing samples (a) based on the RF algorithm (Mean Decrease Gini). calculating the biological identifiers for ITS sequencing samples (b) based on the RF algorithm (Mean Decrease Gini)

Comparative Analysis of Differential Metabolites in Leaves across Different States

Employing partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), a statistical and machine learning approach, to investigate the metabolites across four groups revealed a distinct separation between fresh leaves and processed leaves, resulting in the formation of four clusters (Table. S6). Additionally, three clusters emerged within the processed leaves category. Notably, the processing state accounted for the largest proportion of the metabolic changes (32.47%; Fig. 4a), demonstrating that processing conditions dominantly reshape metabolite profiles.

Fig. 4.

Effect of different processing stages on differential metabolites. (a) Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) of metabolites during the processing period. (b) Differential metabolite analysis. (c) Venn diagram analysis of differential metabolites in T1 vs. T2, T1 vs. T3, and T1 vs. T4 groups. (d) Venn diagram analysis of differential metabolites in T2 vs. T3, T2 vs. T4, and T3 vs. T4 groups. (e) KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites in T1 vs. T2, T1 vs. T3, and T1 vs. T4 groups. (f) KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites in T2 vs. T3, T2 vs. T4, and T3 vs. T4 groups. (g) Expression patterns of differential metabolites associated with carbohydrate metabolism across different processing stages. KEGG pathway descriptions: map00010 (Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis), map00020 (Citrate cycle, TCA cycle), map00030 (Pentose phosphate pathway), map00040 (Pentose and glucuronate interconversions), map00051 (Fructose and mannose metabolism), map00052 (Galactose metabolism), map00053 (Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism), map00500 (Starch and sucrose metabolism), map00520 (Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism), map00620 (Pyruvate metabolism), map00630 (Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism), map00640 (Propanoate metabolism), map00650 (Butanoate metabolism), map00660 (C5-Branched dibasic acid metabolism)

Through the comparative analysis of differential metabolites across stages T1, T2, T3, and T4, a total of 4,985 significantly up-regulated or down-regulated metabolites were identified (Fig. 4b). To systematically evaluate the effects of processing on metabolites, we designed a multi-stage comparison strategy. On one hand, T1 was used as the baseline control and compared with T2, T3, and T4 respectively, revealing the metabolic differences between fresh leaves (T1) and different processing stages (T2-T4; Fig. 4c). On the other hand, the progressive stages were compared respectively, with T2 as the control to compare T3 and T4, and then with T3 as the control to compare T4, reflecting the metabolic differences among processed leaves (Fig. 4e). Specifically, compared to stage T1, there were 1,456; 1,741; and 1,736 metabolites that exhibited up-regulation in leaf tissues at stages T2, T3, and T4 respectively. Concurrently, down-regulation was observed for 1,670; 2,195; and 2,201 metabolites in the leaf tissues at these respective stages (Fig. 4b). Notably, however only 416 shared metabolites were detected within the processed leaf tissues from stages T2 to T4 (Fig. 4e). In summary, the differences in metabolite expression between fresh leaf tissues and processed leaf tissues are more pronounced than those observed among processed leaves alone (Fig. 4c and e). KEGG functional enrichment analysis of common differential metabolites revealed significantly enriched functions related to carbohydrate metabolism (Fig. 4b), including pathways such as Citrate cycle (TCA), galactose metabolism, amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism, and starch and sucrose metabolism. Furthermore, fresh leaves and processed leaves at various stages all encompassed the Citrate cycle (TCA cycle; Fig. 4f and Fig. S2a, b, c), but there was no common carbohydrate metabolism pathway among processed leaves (Fig. 4f and Fig. S2d, e, f).

To enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying carbohydrate metabolism, we investigated the specific expression patterns of metabolites potentially involved in this process. The research results show that the expression patterns of these 65 differential metabolites in fresh leaves are significantly different from those in processed leaves. Among them, succinic acid, fumaric acid, citric acid and cis-aconitic acid are involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and their expression levels gradually decrease with the increase in temperature. Lactose, d-raffinose, d-(+)-galactose, galactosylglycerol, d-galactosamine 6-phosphate and uridine 5’-diphosphogalactose are involved in galactose metabolism. Among them, the expression levels of lactose and d-raffinose increase with the increase in temperature, while the expression level of d-(+)-galactose is the highest in the yellowing stage. The expression levels of the other three gradually decrease with the increase in temperature. a, a-Trehalose, trehalose 6-phosphate, sucrose, d-fructose 6-phosphate, d-glucose 6-phosphate and d-(+)-glucose are involved in starch and sucrose metabolism. Among them, a,a-trehalose, sucrose and d-(+)-glucose show an increasing trend in expression levels with the increase in temperature, while the other three show the opposite trend. Furthermore, sixteen metabolites, including d-(+)-glucosamine, udp-n-acetylglucosamine, n-acetylneuraminic acid, udp-n-acetyl-d-mannosamine, udp-d-xylose, udp-4-amino-4,6-dideoxy-n-acetyl-beta-l-altrosamine, n-acetylmuramate, 2,4-bis(acetamido)−2,4,6-trideoxy-beta-l-altropyranose, 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-mannopyranose, 1-phospho-alpha-d-galacturonate, cmp-n, n’-diacetyllegionaminate, chitobiose, n,n’-diacetyllegionaminate, pseudaminic acid, d-(+)-xylose and d-glucuronate, are involved in the amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolic pathways. The expression levels of d-(+)-glucosamine and 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-mannopyranose both increase with the rise in temperature. Notably, the expression level of d-(+)-xylose does not always change according to the temperature. At 72 and 120 h, its expression level is higher than that at 0 h, while at 168 h, the expression level decreases. Notably, metabolites associated with carbohydrate metabolism demonstrate higher expression levels in fresh leaves than those found in processed leaves. Specifically, within pathway 6 (galactose metabolism) and pathway 8 (starch and sucrose metabolism), there are respectively 2 and 3 metabolites that display lower expression levels in fresh leaves but show increased levels upon processing (Fig. 4g).

To assess the influence of the microbiome on relevant metabolites in carbohydrates, mantel correlation analysis was used to look at the relationship between bacterial and fungal community pairs and differential metabolites. For example, Brevibacterium, Staphylococcus, Streptococeus, etc., in bacteria were significantly correlated with the expression patterns of metabolites related to metabolic pathways such as map00520, map00030, and map00500 in carbohydrates. In addition, Streptococcus was highly correlated with the expression patterns of map00020 and related metabolites in other Metabolic pathway (Fig. 5a). In the fungal community, Acremonium, Ganoderma and other fungi were significantly correlated with the expression patterns of related metabolites of metabolic pathways such as map00520, map00030, and map00500 in carbohydrates. In addition, fungi such as Cladosporium and Dissoconium were extremely significantly correlated with metabolic pathways such as map00520 and map00500 (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

The influence of microbial communities on carbohydrate-related metabolites. Mantel test correlation analysis of bacterial (a) and fungal (b) biomarkers with carbohydrate metabolic pathways. (c) Correlation analysis of key enzymes and related compounds involved in starch and sucrose metabolism. Correlation analysis was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation method. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.001

Considering the important role of starch in tobacco, PICRUSt2 was used to predict the metabolic functions of bacterial communities. Genes encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) can indicate the tobacco biomass degradation capacity of microbial communities. Key Enzyme Commission (EC) taxonomic numbers involved in starch and sucrose metabolism pathways are listed. The starch degradation process contains a-amylase and glucan phosphorylase. The sucrose degradation process contains invertase and sucrose synthase. The analysis showed that α-amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) and invertase (EC 3.2.1.26) were significantly positively correlated with sucrose accumulation and negatively correlated with glucose 6p conversion. In addition, α-amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) was positively correlated with glucose accumulation and realization. Sucrose phosphate synthase (EC 2.4.1.14) and EC 3.2.1.10 had a significant positive correlation with D-fructose − 6-phosphate accumulation, while sucrose synthase (EC 2.4.1.13) also had a high effect on glucose accumulation (Fig. 5c).

To elucidate the influence of key microorganisms on related compounds, a correlation heat map analysis was employed to investigate the relationships between specific metabolites in carbohydrate metabolism and their corresponding biomarkers. The results indicated that lactose exhibited significant positive correlations with six bacterial genera, including Streptomyces, Mycobacterium, and Saccharopolyspora. Sucrose showed similar positive associations with four genera such as Nocardiopsis and Oceanobacillus; while D-glucose was positively correlated with nine genera including Oceanobacillus and Virgibacillus (Fig. 6a). Additionally, important metabolites like lactose, sucrose, and D-glucose were significantly positively correlated with four fungal markers including Microascus and Aspergillus (Fig. 6b). Conversely, lactose and sucrose demonstrated negative correlations with nine genera including Rachicladosporium and Pseudopithomyces (Fig. 6b); furthermore, D-glucose displayed a negative correlation specifically with Pseudopithomyces (Fig. 6b). These significant correlations between keystone species and related compounds suggest their crucial roles in the enrichment or degradation processes of these compounds.

Fig. 6.

Correlation analysis between biomarkers and carbohydrates. (a) Correlation analysis between important biomarkers of 16 S rDNA sequencing samples and carbohydrates, (b) Correlation analysis between important biomarkers of ITS sequencing samples and carbohydrates. Correlation analysis was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation method. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.001

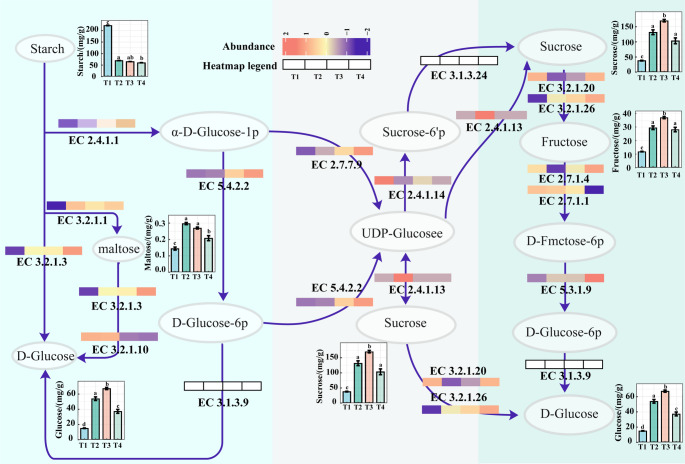

Reconstruction of Metabolic Pathways for Starch and Sucrose Degradation

To enhance the understanding of the synergistic effects of bacterial members on starch and sucrose metabolism, the metabolic pathways for these compounds were reconstructed. This reconstruction was based on the abundance levels of key enzymes predicted by PICRUSt2 for the bacterial communities, alongside the measured concentrations of related metabolites. The number of genes corresponding to relevant enzymes and the changes in compound concentrations are presented. The initial step in starch hydrolysis involves glycogen phosphorylase (EC 2.4.1.1) and amylase (EC 3.2.1.1). Analysis revealed that the expression of these enzymes in processed leaves was significantly higher than in fresh leaves, indicating substantial hydrolysis of starch during the processing of tobacco tissues. Glycosidase (EC 3.2.1.3) and oligo-1,6-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.10) continue to hydrolyze dextrin into D-glucose. Additionally, α-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.20) can convert maltose into D-glucose. Meanwhile, α-D-glucose 1-phosphate is hydrolyzed to D-glucose-6-phosphate by phosphoglucomutase (EC 5.4.2.2) and subsequently to D-glucose. Furthermore, α-D-glucose 1-phosphate can be used to yield sucrose through the action of UTP—glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (EC 2.7.7.9), sucrose-phosphate synthase (EC 2.4.1.14), sucrose synthase (EC 2.4.1.13), and sucrose-phosphate phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.24). Sucrose is then hydrolyzed into D-glucose and D-fructose by α-glucosidases (EC 3.2.1.20) and β-fructofuranosidases (EC 3.2.1.26), with fructose being further converted into D-glucose via sequential reactions (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram of starch and sucrose biosynthesis. Different letters above the bar charts indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s HSD test at p < 0.05 level. In the legend of the heatmap, T1 represents fresh leaves, T2 represents the yellowing stage, T3 represents the color-fixing stage, and T4 represents the stem-drying stage

Enzymes within this metabolic pathway contribute to the accumulation of glucose and sucrose through two main scenarios. Regarding glucose accumulation, enzymes associated with the metabolism of maltose, dextrin, and fructose function predominantly during the Fresh (T1) and Yellowing (T2) stages, facilitating both starch hydrolysis and the transformation of intermediate metabolites. In contrast, enzymes involved primarily in the direct degradation pathways of starch and sucrose play a more significant role during the Color-fixing (T3) and Stem-drying (T4) stages, promoting the overall increase in accumulated glucose. Sucrose biosynthesis is chiefly influenced by the content of UDP-glucose, which serves as a key intermediary product generated during starch breakdown. The abundance levels of enzymes directly responsible for producing UDP-glucose were elevated during the Color-fixing (T3) and Stem-drying (T4) stages compared to the earlier Fresh (T1) and Yellowing (T2) stages. The enhanced expression of these enzymes associated with starch hydrolysis, which ultimately produce UDP-glucose, results in its accelerated synthesis, thereby promoting the subsequent synthesis and accumulation of sucrose (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Dynamic Microbial Succession Drives the Temporal Changes in Starch and Sucrose Metabolism

Metabolomics analysis revealed that the TCA cycle (citric acid cycle), starch and sucrose metabolism pathways were significantly enriched in processed leaves (Fig. 4d). The expression differences of carbohydrate metabolites between fresh leaves and processed leaves were particularly prominent (Fig. 4g). Meanwhile, starch was continuously decomposed, resulting in dynamic accumulation of substances such as D-glucose, sucrose, and maltose during the T1-T4 stages (Fig. 1a, b and e), indicating that carbohydrate metabolism runs through the entire processing process.

The enrichment of these metabolic pathways indicates that starch and sucrose metabolism may be driven by specific microbial functional modules in a staged manner. High-throughput sequencing indicates that the Firmicutes phylum, Actinobacteria phylum, and Bacteroidetes phylum are dominant in the bacterial community during the processing, and the abundance of Firmicutes phylum significantly increases at the Yellowing stage (Fig. 2a). Previous studies have shown that an increase in temperature can promote the increase in the abundance of Firmicutes phylum [40] and reduce the abundance of Actinobacteria phylum [41], which is consistent with the results in Fig. 2 (Fig. 2a). The Firmicutes phylum can change the sugar metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and lipid metabolism of tobacco leaves, improving the quality of tobacco leaves [42, 43], and produce flavor precursor substances such as reducing sugars, amino acids, and various organic molecules [44]. Some genomic sequences of Actinobacteria show extraordinary potential for converting lignin-derived compounds [41]. Certain strains of Brevibacterium, which belong to the dominant Brevibacterium species in the Stem-drying stage of this study (Fig. 2b), can significantly increase the content of sucrose, glucose, fructose, and phenolic compounds when inoculated onto plants [45]. The Paenibacillus (Fig. 2b) expressing fructose diphosphate aldolase and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex components, etc., participate in the glycolysis pathway in Arabidopsis plants, providing the required carbon for the plants [46]. The dominant Ascomycota phylum and Basidiomycota phylum in this study play a role throughout the processing process (Fig. 2c). Previous studies have shown that two fungal phyla detect many enzymes that promote the degradation of plant polysaccharides, such as α-galactosidase, β-glucanase, and xyloglucanase, indicating that they have the ability to degrade various plant polysaccharides extensively [47]. This can reduce the negative impact of stubborn macromolecular compounds such as cellulose and lignin on tobacco leaves. Cladosporium (Fig. 2d), which belongs to the same genus as the Ascomycota, has also been used for the production of cellulase and protease [48]. In addition, the high abundance of Cladosporium (Fig. 2d) may also be the cause of mold contamination in the processed products [49].

Functional Correlations and Proposed Metabolic Roles of Core Microbial Biomarkers

To succinctly summarize the intricate relationships between core microbial taxa and metabolic processes, we propose a synthetic model of their putative roles based on correlation analysis and literature evidence (Table 1). The biomarkers identified in this study, including Brevibacterium (Fig. 3a), Staphylococcus (Fig. 3a), Aspergillus, Cladosporium (Fig. 3b), and Ganoderma (Fig. 3b), demonstrate core functions through their associations with key metabolites. These microorganisms have been confirmed to possess significant advantages in various types of fermentation processes, such as meat fermentation [50], douchi fermentation [51], and condiment fermentation [52].

Table 1.

Correlation between core microbial biomarkers, key metabolic traits, and their putative roles

| Core Microbial Biomarker | Associated Metabolic Trends (Based on Correlation Analysis) |

Putative Ecological Role (Based on Correlation and Literature Support) |

|---|---|---|

|

Brevibacterium (Actinobacteria) |

Positive: D-Glucose |

Degrader. Its abundance is significantly positively correlated with glucose accumulation, and it can produce amylase, suggesting it plays an important role in the process of starch degradation to glucose. Its function may involve sugar metabolism [40, 45]. |

|

Staphylococcus (Firmicutes) |

Positive: Citric acid, Succinic acid, Fumaric acid |

Transformers. Its abundance is positively correlated with various TCA cycle intermediates, suggesting it actively participates in energy metabolism and the transformation of organic acids, which may affect the formation of flavor precursors in the product [51, 68]. |

|

Aspergillus (Ascomycota) |

Positive: D-Glucose |

Degrader. Its abundance is positively correlated with glucose accumulation. Literature reports that this fungal genus has a strong ability to degrade complex polysaccharides (e.g., secreting amylase, cellulase) [49, 57], suggesting it is a core fungal taxon driving initial degradation. |

|

Cladosporium (Ascomycota) |

Positive: D-Glucose 6-phosphate Negative: Lactose, Sucrose |

Transformers. Its abundance is positively correlated with pentose phosphate pathway intermediate and negatively correlated with disaccharides, suggesting it shunts carbon flow into the pentose phosphate pathway for biosynthesis rather than simple sugar accumulation [46, 47]. |

|

Ganoderma (Basidiomycota) |

Positive: D-Glucose 6-phosphate D-Fructose 6-phosphate |

Transformers. Its abundance is positively correlated with sugar phosphate intermediates. Literature indicates that this genus encodes a rich array of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) [60], suggesting it participates in the transformation and modification of sugars, potentially affecting final product quality [61]. |

Notes: It is crucial to emphasize that the discussion of microbial functions in this study is based on correlation analysis with metabolites and supported by existing literature. Due to the limitations of amplicon sequencing technology, we cannot directly attribute specific enzymatic functions (such as EC) predicted at the community level to any bacterial genus. Therefore, the inferences regarding microbial ecological functions in the table aim to provide a clear framework and testable hypotheses for understanding the synergistic roles of microbial communities during the processing

Brevibacterium showed a significant positive correlation with D-glucose (Fig. 6a) and possesses the ability to produce amylase, which is directly related to starch degradation [53]. Members of this genus also contribute to fermentation by producing amino acids, aroma compounds, carotenoids, and antimicrobial substances, which play important roles in the formation of cheese flavor during fermentation [54, 55]. Cladosporium and Ganoderma were negatively correlated with lactose and sucrose; however, their connections with positively correlated metabolites such as D-glucose-6-phosphate and sedoheptulose-7-phosphate (Fig. 6b) suggest their potential to regulate carbon metabolic flux through the pentose phosphate pathway and gluconeogenesis pathway, thereby promoting the generation of intermediate products [56, 57]. Specifically, Cladosporium can secrete carbohydrate esterases (CE) and glycoside hydrolases (GH) that act on the deacetylation of plant polysaccharides [57] and has the capability to decompose lignin and carbohydrates during the fermentation and decomposition of forest litter [58]. Ganoderma, on the other hand, can encode various carbohydrate-active enzymes, including carbohydrate esterases (CE), glycoside hydrolases (GH), glycosyltransferases (GT), and polysaccharide lyases (PL), which are involved in metabolic pathways such as “starch and sucrose metabolism”, “glycolysis/gluconeogenesis”, and “pyruvate metabolism” [59]. Simultaneously, as a medicinal mushroom, Ganoderma is also used as a dietary supplement to improve the quality of steamed buns. It can degrade starch in the dough into glucose, maltose, soluble polysaccharides, etc., reducing the hardness and chewiness of the steamed buns while enhancing their flavor and aroma [60]. Furthermore, Staphylococcus and Ganoderma showed positive correlations with citric acid, succinic acid, fumaric acid, and cis-aconitic acid (Fig. 6a and b). This may resemble the strategy of overexpressing MDH in cyanobacteria, which involves modulating the activity of specific enzymes to enhance the oxidative or reductive branches of the TCA cycle, thereby balancing carbon metabolic pressure and accumulating C4 intermediates [61]. Staphylococcus can also efficiently decompose glucose via the EMP (glycolysis) and HMP (phosphogluconate) pathways, converting it into pyruvate and generating organic acids such as lactic acid and acetic acid. This lowers the pH, inhibits the growth of spoilage bacteria, dominates carbohydrate degradation in fermented meat, and establishes an acidic foundation [50]. This genus is also involved in the hydrolysis of proteins to produce peptides and amino acids (precursors of flavor compounds) during the fermentation of broad bean paste and sausages [52, 62]. Aspergillus exhibited a positive correlation with soluble sugars (e.g., D-glucose; Fig. 6b), indicating its role in initiating degradation through the secretion of amylase and cellulase [63]. Aspergillus is widely used in food fermentation and the large-scale production of enzymes, organic acids, and bioactive compounds [64]. It can produce cellulase, pectinase, amylase, and other enzymes that degrade complex polysaccharides [63]. In the fermentation of Pu-erh tea, it participates in the metabolism of glycosides and polysaccharides and the production of oligosaccharides, ensuring a rich taste profile [65]. This may form a metabolic relay with the phosphorylated intermediate products generated by Cladosporium.

Regarding some fungi in the study, such as Pseudopithomyces and Phoatospora (Fig. 3b), for which carbohydrate metabolic pathways have not been reported, although they were negatively correlated with glucose, lactose, and sucrose (Fig. 6b), they were highly correlated with map00500 (starch and sucrose metabolism) (Fig. 5b) and showed significant positive correlations with key intermediate metabolites such as D-glucose-6-phosphate, D-fructose-6-phosphate, succinic acid, and citric acid (Fig. 6b). This might be due to metabolic inhibition by Aspergillus (or Cladosporium). When Aspergillus dominates the degradation process, its antimicrobial metabolites (such as isofraxidin) may inhibit the growth of competing microbial communities like Pseudopithomyces by altering the microenvironmental pH or through direct toxicity [66]. Based on the correlation analysis between these biomarkers and the metabolites and metabolic pathways, coupled with their known functions in various fermentation processes, we propose Brevibacterium, Staphylococcus, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, and Ganoderma as key biomarkers. We speculate that Brevibacterium, Cladosporium, and Aspergillus form the main line of starch degradation, while Ganoderma and Staphylococcus promote the generation and transformation of intermediate metabolites through the TCA cycle and phosphorylative metabolism, further participating in starch and sucrose metabolism.

Metabolic Division of Labor among Core Microorganisms in Carbohydrate Degradation

During the processing of plant leaves, the dynamic metabolism of starch, sucrose, and glucose is driven by microorganisms in a coordinated manner, presenting distinct phased characteristics (Figure. 7). In the initial degradation stage, the Firmicutes phylum, Paenibacillus, highly expresses amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) to cleave amylopectin into maltose [67], while the Actinobacteria phylum, Streptomyces, secretes glucanase (EC 3.2.1.3) to target the α−1,6 glycosidic bonds of amylopectin and release free glucose [68]. This process is like the metabolic remodeling during the saccharification stage of big koji fermentation. Under the temperature conditions of 51–53 °C in the early fermentation stage, Bacillus rapidly converts the stored starch in wheat into soluble sugars through the action of amylase, providing substrates for subsequent fermentation [69]. It is noteworthy that the Brevibacterium genus has participated in primary degradation through the secretion of amylase [53] at this stage, laying the foundation for its subsequent metabolic dominance [45]. As the processing continues, Brevibacterium catalyzes the hydrolysis of maltose into glucose [70] through α-glucanase (EC 3.2.1.20) and catalyzes the hydrolysis of sucrose into D-glucose and D-fructose [71] through β-fructofuranosidase (EC 3.2.1.26). Meanwhile, the fungal community begins to take effect: Aspergillus, through amylase and cellulase [63], initiates the degradation of stubborn polysaccharides, and the D-glucose generated by Aspergillus combines with D-glucose 6-phosphate produced by Cladosporium to form a metabolic relay [72]. Additionally, Staphylococcus may convert intermediates such as citric acid and succinic acid into ATP through the TCA cycle [61, 73] and accumulate flavor precursors [74]; Ganoderma promotes the accumulation of soluble sugars through glycosyltransferase (GT) and polysaccharide lyase (PL), and its application in steamed buns has been proven to optimize the final quality [59, 60]. Notably, Cladosporium secretes isofraxidin-like antibacterial substances to inhibit the metabolic activity of competing bacterial populations (such as Pseudopithomyces), forming a chemical defense barrier to maintain its dominant position [66]. It must be emphasized that the interpretation of microbial functions in this study is primarily based on epiphytic community information obtained through surface elution. Although this method effectively reflects the compositional characteristics of leaf surface microorganisms, it may theoretically include residual DNA from inactive cells, suggesting the need for more cautious interpretation of the results. This limitation is particularly evident during the later stages of processing (T3: color-fixing stage and T4: stem-drying stage), when considering the potential important role of endophytic microbial communities within the leaf tissues. As plant tissues gradually senesce and lose structural integrity due to high temperature and low humidity, endophytes undergo niche transition and enter a saprophytic stage [75–77]. These microorganisms emerge from the degrading plant tissues, carrying abundant enzyme systems (such as cellulases, laccases, etc.) capable of effectively degrading recalcitrant internal plant compounds (such as lignocellulose) [76]. This degradation process originating from within the leaves likely synergizes with the external activities of epiphytic microorganisms on the leaf surface, forming a systematic internal-external collaborative degradation model. Notably, the dominant position of saprophytic-capable genera (such as Cladosporium and Alternaria) observed in the epiphytic communities during the later stages of processing may partially originate from this gradually exposed endophytic microbial reservoir. Therefore, the metabolic relay mechanism between bacteria and fungi proposed in this study may be further supported by the functional shift of endophytes toward active saprophytes, and this multi-source microbial synergy contributes significantly to starch decomposition and the accumulation of soluble sugars and flavor precursors.

Based on the above understanding, we can more comprehensively comprehend the synergistic role of microbial communities during processing: bacteria and fungi collectively influence starch and sucrose metabolic pathways through metabolic division of labor. Brevibacterium and other bacteria primarily rely on amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) and α-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.20) to efficiently degrade macromolecular polysaccharides, while Aspergillus and other fungi enhance the accumulation of intermediate metabolites such as D-glucose-6-phosphate. Ultimately, a metabolic relay division of labor model dominated by bacteria and assisted by fungi is formed, providing a favorable substrate foundation for subsequent tobacco leaf fermentation.

Implications for Tobacco Processing and Future Perspectives

This study not only elucidates the interaction mechanisms between microbial communities and metabolic processes during tobacco curing but, more importantly, identifies core functional microorganisms—including Brevibacterium, Staphylococcus, Aspergillus, Cladosporium, and Ganoderma—providing valuable candidate microbial resources for optimizing industrial tobacco processing. The remarkable functions of these microorganisms in various fermentation systems have been well-documented: Brevibacterium produces aromatic compounds and antimicrobial substances [53, 55]. Staphylococcus exhibits high efficiency in degrading carbohydrates and proteins [50, 52]. Aspergillus possesses a powerful enzyme system for breaking down complex polysaccharides [63, 64]. and Ganoderma encodes abundant CAZymes [59, 60]. Based on these findings, we propose that during the curing process, Brevibacterium, Cladosporium, and Aspergillus form the main pathway for starch degradation, while Ganoderma and Staphylococcus promote the generation and transformation of intermediate products through the TCA cycle and phosphorylative metabolism. The internal-external synergy model, driven by both epiphytic microbial activity and endophytic functional transformation, provides a critical microbiological and metabolic foundation for enhancing tobacco processing quality.

In conclusion, this study establishes a theoretical basis and application prospects for the directed regulation of tobacco processing using microbial strategies. Future research should focus on the following three directions: (1) applying viability discrimination techniques (e.g., PMA treatment) to more accurately identify active microbial communities truly functional during processing, avoiding interference from residual DNA; (2) concentrating on the targeted isolation, cultivation, and in vitro functional validation of the core functional microorganisms discovered in this study, particularly those endophytes with application potential; (3) ultimately exploring the development of compound microbial inoculants from these core functional microorganisms and applying them to industrial tobacco processing, offering novel solutions for achieving the goal of quality enhancement and efficiency improvement.

Conclusion

This study integrates metabolomics and microbial community analysis to systematically uncover the dynamics of carbohydrate metabolism during leaf processing and the underlying microbial mechanisms. The research shows that an increase in temperature and a decrease in humidity during the processing process lead to a reduction in the abundance and diversity of microbial communities. The study identified Brevibacterium, Staphylococcus, Aspergillus, and Ganoderma as core biomarkers, providing candidate strains for optimizing the regulation process of tobacco. It reveals that bacteria lead the initial starch degradation, while fungi promote soluble sugar accumulation by transforming intermediate products. This microbial cooperation establishes a synergy model encompassing initial degradation by bacteria, subsequent transformation of intermediates by fungi, and fine regulation of metabolic fluxes by the entire community. This degradation-transformation-regulation synergy model provides a new perspective for the effective utilization of complex carbon sources.

In summary, using multi-omics resources to analyze the influence of microorganisms on key carbohydrates during tobacco leaf processing and accurately understanding the interaction between microorganisms and tobacco is crucial for improving tobacco production efficiency.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Supercomputing Center of Shandong Agricultural University for the technical support provided. This study was supported by the Science and Technology Project of China Tobacco General Corporation [1102022202016/110202201019(LS-03)], the Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Science and Technology Department (QKHJC-ZK [2022] YB288), the Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Tobacco Industry Technology Center (2022XM17), and the Science and Technology Project of Shandong Tobacco Industry Technology Center (202111

Author Contributions

C.Z. and X.H.Z. were responsible for writing the main text of the paper, while F.W. was responsible for data organization, methods and article revision. L.G.H. was in charge of Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 and J.D. was responsible for Figs. 5, 6 and 7 and Y.C., H.C.W., S.J.W. and X.C.S. were responsible for organizing the article, K.S.W. and L.Y. were responsible for designing, verifying, revising the article and providing funds. All the authors reviewed this paper.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Cheng Zhang and Xiaohua Zhang are the joint first authors.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/13/2025

The original online version of this article was revised:Funding project numbers have been added to the Acknowledgment section.

Contributor Information

Kesu Wei, Email: weiks8816@163.com.

Long Yang, Email: lyang@sdau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Tao JM, Chen QS, Chen SY, Lu P, Chen YQ, Jin JJ, Li JJ, Xu YL, He W, Long T, Deng XH, Yin HQ, Li ZF, Fan JQ, Cao PJ (2022) Metagenomic insight into the microbial degradation of organic compounds in fermented plant leaves. Environ Res. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R (2018) The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:6506–6511. 10.1073/pnas.1711842115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebelstrup KH, Sagnelli D, Blennow A (2015) The future of starch bioengineering: GM microorganisms or GM plants? Front Plant Sci 6. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00247

- 4.Zhu Q, Chen LQ, Peng Z, Zhang QL, Huang WQ, Yang F, Du GC, Zhang J, Wang L (2023) The differences in carbohydrate utilization ability between six rounds of Sauce-flavor Daqu. Food Res Int. 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang XY, Peng Z, Zhu Q, Zheng TF, Liu XY, Yang JH, Zhang J, Li JH (2023) Exploration of seasonal fermentation differences and the possibility of flavor substances as regulatory factors in Daqu. Food Res Int. 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur R, Prasad K (2021) Technological, processing and nutritional aspects of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) - a review. Trends Food Sci Technol 109:448–463. 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.01.044 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shang Z, Ye Z, Li M, Ren H, Cai S, Hu X, Yi J (2022) Dynamics of microbial communities, flavor, and physicochemical properties of pickled chayote during an industrial-scale natural fermentation: correlation between microorganisms and metabolites. Food Chem 377:132004. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.132004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizo J, Guillén D, Farrés A, Díaz-Ruiz G, Sánchez S, Wacher C, Rodríguez-Sanoja R (2020) Omics in traditional vegetable fermented foods and beverages. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 60:791–809. 10.1080/10408398.2018.1551189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan XY, Wang T, Sun LP, Qiao Z, Pan HY, Zhong YJ, Zhuang YL (2024) Recent advances of fermented fruits: a review on strains, fermentation strategies, and functional activities. Food Chemistry: X. 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang YY, Peng J, Li QQ, Song QF, Cronk Q, Xiong B (2024) Optimization of pile-fermentation process, quality and microbial diversity analysis of dark hawk tea (Machilus rehderi). LWT. 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115707 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng X, Deng HC, Huang L, Teng JW, Wei BY, Xia N, Pang BW (2024) Degradation of cell wall polysaccharides during traditional and tank fermentation of Chinese Liupao tea. J Agric Food Chem 72:4195–4206. 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c07447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo X-Y, Lv Y-Q, Ye Y, Liu Z-Y, Zheng X-Q, Lu J-L, Liang Y-R, Ye J-H (2021) Polyphenol oxidase dominates the conversions of flavonol glycosides in tea leaves. Food Chem 339:128088. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang AL, Lei QQ, Zhang BB, Wu JH, Fu ZY, He JF, Wang YB, Wu XY (2024) Revealing novel insights into the enhancement of quality in black tea processing through microbial intervention. Food Chemistry: X. 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang LY, Mai J, Shi JF, Ai KB, He L, Zhu MJ, Hu ZBB (2024) Study on tobacco quality improvement and bacterial community succession during microbial co-fermentation. Ind Crop Prod. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117889 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren MJ, Qin YQ, Zhang LY, Zhao YY, Zhang RN, Shi HZ (2023) Effects of fermentation chamber temperature on microbes and quality of cigar wrapper tobacco leaves. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 107:6469–6485. 10.1007/s00253-023-12750-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wardman JF, Bains RK, Rahfeld P, Withers SG (2022) Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) in the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:542–556. 10.1038/s41579-022-00712-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weng SN, Deng MZ, Chen SY, Yang RQ, Li JJ, Zhao XB, Ji SH, Wu LX, Ni L, Zhang ER, Wang CC, Qi LF, Liao KQ, Chen YQ, Zhang W (2024) Application of pectin hydrolyzing bacteria in tobacco to improve flue-cured tobacco quality. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 10.3389/fbioe.2024.1340160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong YN, Li JJ, Deng XH, Chen YQ, Chen SY, Huang HM, Ni L, Long T, He W, Zhang JP, Jiang ZK, Fan JQ, Zhang W (2023) Application of starch degrading bacteria from tobacco leaves in improving the flavor of flue-cured tobacco. Front Microbiol. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1211936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding J, Wei K, Shang X, Sha Y, Qin L, Li H, Wang D, Zhang X, Wu S, Li D, Wang F, Yang L (2023) Bacterial dynamic of flue-cured tobacco leaf surface caused by change of environmental conditions. Front Microbiol. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1280500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.BB H, KY G, JSQ G, K Z, D C, X H, Y C, KX G, Y J, K H, YM Z, CM Z (2021) The effect of flue-curing procedure on the dynamic change of microbial diversity of tobaccos. Sci Rep 11. 10.1038/s41598-021-84875-6

- 21.Santoyo G (2022) How plants recruit their microbiome? New insights into beneficial interactions. J Adv Res 40:45–58. 10.1016/j.jare.2021.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qin Y, Druzhinina IS, Pan XY, Yuan ZL (2016) Microbially mediated plant salt tolerance and microbiome-based solutions for saline agriculture. Biotechnol Adv 34:1245–1259. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jing Y, Chen W, Qiu X, Qin S, Gao W, Li C, Quan W, Cai K (2024) Exploring metabolic characteristics in different geographical locations and yields of Nicotiana tabacum L. using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry pseudotargeted metabolomics combined with chemometrics. Metabolites. 10.3390/metabo14040176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anguita-Maeso M, Haro C, Navas-Cortés JA, Landa BB (2022) Primer choice and xylem-microbiome-extraction method are important determinants in assessing xylem bacterial community in Olive trees. Plants. 10.3390/plants11101320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams RI, Miletto M, Taylor JW, Bruns TD (2013) Dispersal in microbes: fungi in indoor air are dominated by outdoor air and show dispersal limitation at short distances. ISME J 7:1262–1273. 10.1038/ismej.2013.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun H, Wang T, Liu S, Tang X, Sun J, Liu X, Zhao Y, Shen P, Zhang Y (2024) Novel insights into the rhizosphere and seawater microbiome of Zostera marina in diverse mariculture zones. Microbiome 12:27. 10.1186/s40168-024-01759-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin M (2011) Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal (3):17. 10.14806/ej.17.1.200

- 28.Magoč T, Salzberg SL (2011) Flash: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27:2957–2963. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edgar RC (2013) UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods 10:996–998. 10.1038/nmeth.2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R (2011) Uchime improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27:2194–2200. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukherjee S, Stamatis D, Li CT, Ovchinnikova G, Kandimalla M, Handke V, Reddy A, Ivanova N, Woyke T, Eloe-Fardosh EA, Chen IA, Kyrpides NC, Reddy TBK (2025) Genomes online database (GOLD) v.10: new features and updates. Nucleic Acids Res 53:D989–d997. 10.1093/nar/gkae1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsson RH, Larsson KH, Taylor AFS, Bengtsson-Palme J, Jeppesen TS, Schigel D, Kennedy P, Picard K, Glöckner FO, Tedersoo L, Saar I, Koljalg U, Abarenkov K (2019) The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res 47(D1):D259–D264. 10.1093/nar/gky1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bian J, Sun J, Chang H, Wei Y, Cong H, Yao M, Xiao F, Wang H, Zhao Y, Liu J, Zhang X, Yin L (2023) Profile and potential role of novel metabolite biomarkers, especially indoleacrylic acid, in pathogenesis of neuromyelitis Optica spectrum disorders. Front Pharmacol. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1166085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang Z, Lu Y, Zhou G, Hui F, Xu L, Viau C, Spigelman AF, MacDonald PE, Wishart DS, Li S, Xia J (2024) Metaboanalyst 6.0: towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res 52:W398-w406. 10.1093/nar/gkae253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villanueva RAM, Chen ZJ (2019) Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis (2nd ed.). Meas Interdiscip Res Perspect 17:160–167. 10.1080/15366367.2019.1565254 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trygg J, Wold S (2002) Orthogonal projections to latent structures (O-PLS). J Chemometrics 16:119–128. 10.1002/cem.695 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Boutros PC (2011) Venndiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics 12:35. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolde R (2019) pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. R package version 1.0.12. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap

- 39.Douglas GM, Maffei VJ, Zaneveld J, Yurgel SN, Brown JR, Taylor CM, Huttenhower C, Langille MGI (2019) PICRUSt2: An improved and extensible approach for metagenome inference. bioRxiv: 672295. 10.1101/672295

- 40.Pérez Castro S, Cleland EE, Wagner R, Sawad RA, Lipson DA (2019) Soil microbial responses to drought and exotic plants shift carbon metabolism. ISME J 13:1776–1787. 10.1038/s41396-019-0389-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghai R, Mizuno CM, Picazo A, Camacho A, Rodriguez-Valera F (2014) Key roles for freshwater actinobacteria revealed by deep metagenomic sequencing. Mol Ecol 23:6073–6090. 10.1111/mec.12985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu Y, Ding Y, Ren C, Sun Z, Rodionov DA, Zhang W, Yang S, Yang C, Jiang W (2010) Reconstruction of xylose utilization pathway and regulons in firmicutes. BMC Genomics 11:255. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Q, Kong G, Zhao G, Liu J, Jin H, Li Z, Zhang G, Liu T (2023) Microbial and enzymatic changes in cigar tobacco leaves during air-curing and fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 107:5789–5801. 10.1007/s00253-023-12663-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xing L, Zhang M, Liu L, Hu X, Liu J, Zhou X, Chai Z, Yin H (2023) Multiomics provides insights into the succession of microbiota and metabolite during plant leaf fermentation. Environ Res 221:115304. 10.1016/j.envres.2023.115304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferreira MJ, Veríssimo ACS, Pinto D, Sierra-Garcia IN, Granada CE, Cremades J, Silva H, Cunha A (2024) Engineering the rhizosphere Microbiome with plant growth promoting bacteria for modulation of the plant metabolome. PLANTS-BASEL 13. 10.3390/plants13162309

- 46.Kwon YS, Lee DY, Rakwal R, Baek S-B, Lee JH, Kwak Y-S, Seo J-S, Chung WS, Bae D-W, Kim SG (2016) Proteomic analyses of the interaction between the plant-growth promoting rhizobacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 and Arabidopsis thaliana. Proteomics 16:122–135. 10.1002/pmic.201500196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manici LM, Caputo F, De Sabata D, Fornasier F (2024) The enzyme patterns of Ascomycota and basidiomycota fungi reveal their different functions in soil. Appl Soil Ecol 196:105323. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2024.105323 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu X, Wang Q, Yang L, Chen Z, Zhou Y, Feng H, Zhang P, Wang J (2024) Effects of exocellobiohydrolase CBHA on fermentation of tobacco leaves. J Microbiol Biotechnol 34:1727–1737. 10.4014/jmb.2404.04028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue DQ, Chen XL, Zhang H, Chai XF, Jiang JB, Xu XY, Li JF (2016) Transcriptome Analysis of the Cf-12-Mediated Resistance Response to Cladosporium fulvum in Tomato. Front Plant Sci 7: 2012. 10.3389/fpls.2016.02012

- 50.Fan Y, Badar IH, Liu Q, Xia X, Chen Q, Kong B, Sun F (2025) Insights into the flavor contribution, mechanisms of action, and future trends of coagulase-negative Staphylococci in fermented meat products: a review. Meat Sci 221:109732. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2024.109732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang L, Yang H-l, Tu Z-c, Wang X-l (2016) High-throughput sequencing of microbial community diversity and dynamics during Douchi fermentation. PLoS ONE 11:e0168166. 10.1371/journal.pone.0168166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jia Y, Niu C-T, Xu X, Zheng F-Y, Liu C-F, Wang J-J, Lu Z-M, Xu Z-H, Li Q (2021) Metabolic potential of microbial community and distribution mechanism of Staphylococcus species during broad bean paste fermentation. Food Res Int 148:110533. 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oliveira LCG, Ramos PL, Marem A, Kondo MY, Rocha RCS, Bertolini T, Silveira MAV, da Cruz JB, de Vasconcellos SP, Juliano L, Okamoto DN (2015) Halotolerant bacteria in the Sao Paulo zoo composting process and their hydrolases and bioproducts. BRAZILIAN J Microbiol 46:347–354. 10.1590/S1517-838246220130316 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rana B, Chandola R, Sanwal P, Joshi GK (2024) Unveiling the microbial communities and metabolic pathways of Keem, a traditional starter culture, through whole-genome sequencing. Sci Rep 14(1):4031. 10.1038/s41598-024-53350-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alexa EA, Cobo-Díaz JF, Renes E, O´Callaghan TF, Kilcawley K, Mannion D, Skibinska I, Ruiz L, Margolles A, Fernández-Gómez P, Alvarez-Molina A, Puente-Gómez P, Crispie F, López M, Prieto M, Cotter PD, Alvarez-Ordóñez A (2024) The detailed analysis of the microbiome and resistome of artisanal blue-veined cheeses provides evidence on sources and patterns of succession linked with quality and safety traits. Microbiome 12:78. 10.1186/s40168-024-01790-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clasquin Michelle F, Melamud E, Singer A, Gooding Jessica R, Xu X, Dong A, Cui H, Campagna Shawn R, Savchenko A, Yakunin Alexander F, Rabinowitz Joshua D, Caudy Amy A (2011) Riboneogenesis in yeast. Cell 145:969–980. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu W, Yu S-H, Zhang H-P, Fu Z-Y, An J-Q, Zhang J-Y, Yang P (2022) Two cladosporium fungi with opposite functions to the Chinese white wax scale insect have different genome characters. J Fungi, 8

- 58.Song FQ, Tian XJ, Fan XX, He XB (2010) Decomposing ability of filamentous fungi on litter is involved in a subtropical mixed forest. Mycologia 102:20–26. 10.3852/09-047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu G-J, Wang M, Huang J, Yin Y-L, Chen Y-J, Jiang S, Jin Y-X, Lan X-Q, Wong BHC, Liang Y, Sun H (2012) Deep insight into the ganoderma lucidum by comprehensive analysis of its transcriptome. PLoS ONE 7:e44031. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guowei Z, Lili W, Yufeng L, Hailei W (2019) Impact of the fermentation broth of ganoderma lucidum on the quality of Chinese steamed bread. AMB Express 9:133. 10.1186/s13568-019-0859-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iijima H, Watanabe A, Sukigara H, Iwazumi K, Shirai T, Kondo A, Osanai T (2021) Four-carbon dicarboxylic acid production through the reductive branch of the open cyanobacterial tricarboxylic acid cycle in synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Metab Eng 65:88–98. 10.1016/j.ymben.2021.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aro Aro JM, Nyam-Osor P, Tsuji K, Shimada K-i, Fukushima M, Sekikawa M (2010) The effect of starter cultures on proteolytic changes and amino acid content in fermented sausages. Food Chem 119:279–285. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.06.025 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mojsov KD (2016) Chap. 16 - Aspergillus enzymes for food industries. In: Gupta VK (ed) New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 215–222

- 64.Park H-S, Jun S-C, Han K-H, Hong S-B, Yu J-H (2017) Chapter Three - Diversity, Application, and synthetic biology of industrially important Aspergillus fungi. In: Sariaslani S, Gadd GM (eds) Adv appl microbiol. Academic, pp 161–202

- 65.Ma Y, Ling T-j, Su X-q, Jiang B, Nian B, Chen L-j, Liu M-l, Zhang Z-y, Wang D-p, Mu Y-y, Jiao W-w, Liu Q-t, Pan Y-h, Zhao M (2021) Integrated proteomics and metabolomics analysis of tea leaves fermented by Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus tamarii and Aspergillus fumigatus. Food Chem 334:127560. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Shi T, Wang B (2024) The genus cladosporium: a prospective producer of natural products. Int J Mol Sci. 10.3390/ijms25031652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Silano V, Baviera JMB, Bolognesi C, Brüschweiler BJ, Cocconcelli PS, Crebelli R, Gott DM, Grob K, Lampi E, Mortensen A, Rivière G, Steffensen IL, Tlustos C, Van Loveren H, Vernis L, Zorn H, Glandorf B, Herman L, Aguileria-Gómez M, Horn C, Kovalkovicová N, Liu Y, Maia JM, Chesson A, Enzyme EPFCM (2019) Safety evaluation of the food enzyme α-amylase and 1,4-α-glucan 6-α-glucosyltransferase from < i > Paenibacillus alginolyticus. EFSA J 17. 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5683

- 68.Wu QL, Dou X, Wang Q, Guan ZB, Cai YJ, Liao XR (2018) Isolation of β-1,3-Glucanase-Producing Microorganisms from < i > Poria cocos Cultivation Soil via Molecular Biology. MOLECULES 23. 10.3390/molecules23071555

- 69.Zhang YD, Kang JM, Han BZ, Chen XX (2024) Wheat-origin < i > Bacillus community drives the formation of characteristic metabolic profile in high-temperature i > Daqu. LWT-FOOD Sci Technol 191. 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115597

- 70.Enzymes MEPFC, Processing A, Lambré C, Barat Baviera JM, Bolognesi C, Cocconcelli PS, Crebelli R, Gott DM, Grob K, Lampi E, Mengelers M, Mortensen A, Rivière G, Steffensen I-L, Tlustos C, Van Loveren H, Vernis L, Zorn H, Roos Y, Liu Y, Marini E, di Piazza G, Chesson A (2024) Safety evaluation of an extension of use of the food enzyme α-glucosidase from the non-genetically modified Aspergillus Niger strain AE-TGU. EFSA J 22:e8697. 10.2903/j.efsa.2024.8697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lincoln L, More SS (2017) Bacterial invertases: occurrence, production, biochemical characterization, and significance of transfructosylation. J Basic Microbiol 57:803–813. 10.1002/jobm.201700269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Răut I, Călin M, Capră L, Gurban A-M, Doni M, Radu N, Jecu L (2021) Cladosporium sp. isolate as fungal plant growth promoting agent. Agronomy. 10.3390/agronomy11020392 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen FF, Zhao QM, Yang ZQ, Chen RR, Pan HW, Wang YH, Liu H, Cao Q, Gan JH, Liu X, Zhang NX, Yang CG, Liang HH, Lan LF (2024) Citrate serves as a signal molecule to modulate carbon metabolism and iron homeostasis in < i > Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog 20. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1012425

- 74.Jia Y, Liu Y, Hu W, Cai W, Zheng Z, Luo C, Li D (2023) Development of Candida autochthonous starter for cigar fermentation via dissecting the microbiome. Front Microbiol. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1138877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wolfe ER, Ballhorn DJ (2020) Do foliar endophytes matter in litter decomposition? Microorganisms. 10.3390/microorganisms8030446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nelson A, Vandegrift R, Carroll GC, Roy BA (2020) Double lives: transfer of fungal endophytes from leaves to woody substrates. PeerJ 8:e9341. 10.7717/peerj.9341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schädler M, Yuan Z, Chen L (2014) The role of endophytic fungal individuals and communities in the decomposition of Pinus massoniana needle litter. PLoS ONE 9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105911

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.