Abstract

Perioperative insomnia is a common clinical phenomenon that is associated with increased pain sensitivity during the perioperative period. Understanding the mechanisms underlying acute sleep deprivation-induced hyperalgesia is crucial for improving pain management in these patients. The P2X4 receptor is a key modulator of pain, yet its role in hyperalgesia following acute sleep deprivation remains unclear. In this study, we established an acute sleep deprivation model in mice and found that sleep-deprived animals exhibited significant hyperalgesia along with marked microglial activation and elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the hippocampal CA1 region. Notably, intracerebroventricular administration of the selective P2X4 receptor antagonist 5-BDBD during sleep deprivation significantly ameliorated hyperalgesia, inhibited microglial activation, and reduced cytokine levels. These results suggest that acute sleep deprivation activates P2X4 receptors, which in turn trigger microglial activation and inflammatory cytokine release, ultimately leading to hyperalgesia.

Keywords: Insomnia, Sleep deprivation, P2X4, Inflammatory cytokine

Background

Sleep is a complex and essential physiological process that plays a critical role in the restoration and repair of bodily functions [1]. Adequate sleep regulates the secretion of growth hormone, cortisol, and appetite-related hormones, maintains metabolic homeostasis, and protects cardiovascular health by lowering blood pressure and reducing inflammation [1]. Moreover, sufficient sleep promotes the recovery of the central nervous system by enhancing synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation, as well as facilitating the clearance of metabolic waste via the glymphatic system, thereby mitigating neuroinflammation [2]. In addition, adequate sleep modulates immune function by enhancing T cell and natural killer (NK) cell activity, promoting antibody production, and balancing pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion [3].

Clinically, many patients experience acute sleep insufficiency or sleep disorders due to various factors, which can impair the restorative functions of sleep and increase susceptibility to disease, behavioral changes, and adverse health outcomes [4]. Previous studies have demonstrated that sleep deprivation or sleep disorders can lead to cognitive decline [5], emotional instability [6], immune dysfunction [7], endocrine imbalance [8], metabolic disturbances [9], cardiovascular damage [10], increased cancer risk [11], and enhanced pain sensitivity [12]. Furthermore, even healthy volunteers subjected to 24 h of total sleep deprivation display significantly increased sensitivity to cold and pressure pain [13]. Although sleep deprivation-induced hyperalgesia has been documented, its underlying mechanisms—potentially involving central inflammation—remain to be fully elucidated.

Our previous work has highlighted the pivotal role of the purinergic receptor P2X ligand-gated ion channel 4 (P2X4) receptor in peripheral neuropathic pain [14], where its activation by ATP promotes the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) from microglia, alters inhibitory synaptic plasticity in the spinal dorsal horn, and contributes to pain hypersensitivity [15]. In addition, P2X4 receptor activation can induce the release of proinflammatory cytokines, further amplifying peripheral neuroinflammation [16]. In the central nervous system, however, P2X4 receptors are predominantly expressed on microglia, and whether they contribute to hyperalgesia induced by acute sleep deprivation is not known. In the present study, we investigated the regulatory role of P2X4 receptors in acute sleep deprivation-induced hyperalgesia.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Experimental Animal Center, Nanchang University (#10,811). All procedures were performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and complied with the European Union Directive 2010/63/EU, the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, the US National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 8023, revised 1978), and the EU Directive 2010/62/EU.

Animals and experimental design

This study utilized adult male C57BL/6 mice aged 8–10 weeks. All animals were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups, with control mice receiving the same sham surgery and catheter implantation procedures as the experimental groups. Sleep deprivation was induced for 9 h, while control groups were housed in identical cages with the same environment. The experiment consisted of two parts: Part 1 and Part 2.

In Part 1, C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into two groups: a sleep deprivation group (n = 8) and a control group (n = 8). Upon completion of sleep deprivation (SD), both groups underwent the von Frey test. Thirty minutes later, the same cohort of mice underwent the hot-plate test. Upon completion of the behavioral tests, all mice were anesthetized and euthanized for subsequent biochemical analysis.

In Part 2, C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into five groups: Control group (n = 16), 5-BDBD group (n = 16), SD group (n = 16), SD + Vehicle group (n = 16), and SD + 5-BDBD group (n = 16); prior to sleep deprivation (SD) initiation, 8 mice were randomly selected from each group for baseline testing (T0) consisting of von Frey test and hot-plate test; upon SD completion, another 8 mice per group were randomly selected for von Frey test followed by hot-plate test 30 min later (0 h post-SD, T1); after this behavioral assessment, these T1-tested mice were anesthetized and humanely euthanized for subsequent biochemical analysis; the remaining 8 mice per group underwent behavioral tests (von Frey test and hot-plate test) at three post-SD timepoints: 3 h (T2), 12 h (T3), and 24 h (T4).

Animals were housed under standard conditions (12-h light/dark cycle, 22 ± 1 °C, with free access to food and water). All surgical procedures were performed aseptically under isoflurane anesthesia. Behavioral testing was conducted by researchers blinded to group assignments.

Intracerebroventricular cannulation and EEG/EMG electrode implantation

After a 7-day acclimatization period, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and secured in a stereotaxic frame for intracerebroventricular (ICV) cannulation and implantation of EEG and EMG electrodes. The scalp was shaved and disinfected with povidone-iodine, and the skull was exposed. Using the stereotaxic apparatus, the bregma was identified, and a small burr hole was drilled with a needle tip to allow the insertion of a cannula into the lateral ventricle. The cannula was connected to a microsyringe to confirm patency. Subsequently, EEG electrodes (screws with attached connectors) were implanted on the skull, and EMG electrodes were inserted into the trapezius muscle in the neck region and secured with sutures. All implants were fixed using dental cement, and the mice were allowed to recover for 7 days with careful monitoring for signs of infection.

Sleep deprivation model

An acute sleep deprivation (SD) model was established based on previous protocols [32]. From 08:30 to 17:30, mice were placed in a spacious cage equipped with food and water, and the head-mounted connector was attached to record EEG and EMG signals in real time. New sterilized objects were introduced into home cages exclusively upon EEG/EMG-confirmed NREM sleep onset (characterized by high-amplitude delta waves and low EMG activity), with gentle cage tapping applied only if arousal failed within 1 min; critically, mice were never directly touched to prevent handling stress, and all interventions ceased immediately upon spontaneous wakefulness. Immediately following the sleep deprivation period, behavioral assessments for mechanical and thermal nociception were conducted (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Acute sleep deprivation induces mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in mice. A Schematic timeline of the experimental procedure. Mice were operated head and neck electrode implantation a week ago, then mice were subjected to acute sleep deprivation (SD) from 8:30 to 17:30, followed by Von Frey and hot-plate tests to assess mechanical and thermal pain sensitivity, respectively. Subsequently, brain tissues were collected for immunofluorescence (IF), Western blot (WB), qPCR, and ELISA analyses. B Representative traces of EEG-EMG recording. C Mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) measured by the Von Frey test. D Withdrawal latency in the hot-plate test. SD: sleep deprivation; MWT: mechanical withdrawal threshold. All data are presented as the mean ± SD, **P < 0.01

Von Frey test

Mice were placed on a horizontal metal mesh inside a transparent cylindrical chamber. After a 30-min acclimation period (following 2 days of habituation), different graded von Frey filaments were applied to the right hind paw. Each filament was gently pressed against the skin until bending occurred, maintained for 2 s, and then removed. A positive response—defined as paw withdrawal, licking, shaking, or escape behavior—was recorded. Each stimulus was repeated five times, and the force eliciting at least three positive responses was recorded as the mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT).

Hot-plate test

For thermal nociception assessment, the hot plate was preheated to 50 °C. Each mouse was placed in a transparent cylindrical chamber atop the hot plate, and the latency until a nocifensive response (paw licking, lifting, or jumping) was recorded with a stopwatch. A cutoff time of 30 s was set to prevent injury. Each mouse underwent three trials at 15-min intervals, and the average latency was calculated.

Sample collection

After behavioral assessments, all mice were deeply anesthetized with 6% isoflurane. Some mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and fresh hippocampal tissue was collected and stored at −80 °C. The remaining mice were sequentially perfused with PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), after which whole brains were harvested and immersed in 4% PFA for fixation, then stored at 4 °C.

Western blot analysis

Hippocampal tissues were harvested and homogenized in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Following centrifugation, the supernatants were collected and protein concentrations determined via the BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-P2X4 (Cell Signaling Technology (CST), USA, 1:1000), rabbit anti-phospho-P2X4 (CST, 1:1000), and mouse anti-GAPDH (Proteintech, China, 1:5000). After incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG, Proteintech 1:5000; goat anti-mouse IgG, Proteintech, 1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were washed with TBST, developed using ECL, and band intensities quantified using ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence

Mice were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were post-fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h, then sectioned at 50 μM thickness using a vibratome in PBS. Sections were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 and blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-IBA-1 (CST, 1:500) and mouse anti-GFAP (CST, 1:1000). After washing with PBS, sections were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit, Invitrogen, Germany, 1:500; goat anti-mouse, Invitrogen, 1:500) at room temperature for 1 h in the dark, counterstained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, USA, 1:1000), and mounted for confocal microscopy.

Confocal imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM 880 microscope (20 × objective, NA 0.8) with standardized settings (laser power 5%, gain 700, offset 0%). For each mouse, 3–5 hippocampal CA1 sections were scanned as z-stacks (2 μm thickness). Positive cells were identified by: IBA-1 + microglia (≥ 3 processes, intensity ≥ 2 × background), GFAP + astrocytes (stellate morphology, intensity ≥ 3 × background), and DAPI + nuclei (intensity ≥ 5 × background). Blinded analysis was conducted by two independent researchers using coded samples. Cell density (cells/mm2) and fluorescence intensity (background-corrected) were quantified in ImageJ (v1.53), averaging 3–5 sections per mouse. Specificity was confirmed by negative (no primary antibody) and positive (brain injury model) controls, with > 90% inter-rater agreement from re-analysis of 10% images. All groups were processed simultaneously to avoid batch effects.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Immediately after anesthesia, hippocampal tissues were dissected on ice, rinsed in cold PBS to remove blood, and weighed. Tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer, incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used to measure cytokine levels. The concentrations of interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) were evaluated using IL-1β ELISA Kit and TNF-α ELISA Kit (Boster, China) respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, standards and samples were added to ELISA plates, incubated at 37 °C, washed, and then incubated sequentially with detection antibodies and substrate. The reaction was stopped, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Cytokine concentrations were determined from standard curves.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Following anesthesia, hippocampal tissues were rapidly extracted and homogenized in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) on ice. Total RNA extraction kit (TaKaRa, Japan) and cDNA reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa) and real-time PCR kit (TaKaRa) were all obtained from TaKaRa. GAPDH served as the internal control, and the relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences were as follows: P2X4: forward: 5′-TGATCGTCACCGTGAACCAG-3′; reverse: 5′-TCACAGACGCGTTGAATGGA-3′; GAPDH: forward: 5′-GCTCCTCCCTGTTCCAGAGAC-3′; reverse: 5′-CAATACGGCCAAATCCGTTCA-3′.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, USA) and expressed as mean ± SD. Sample sizes (n = 8–10/group) were determined by power analysis (α = 0.05, β = 0.8) based on pilot data (Cohen's d = 1.2). Normality was verified using Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (Tukey’s post-hoc; η2 reported) or repeated measures ANOVA (Geisser–Greenhouse correction), while non-normal data used Kruskal–Wallis test (Dunn's correction). All analyses were performed by investigators blinded to group allocation, with p < 0.05 considered significant (two-tailed). Effect sizes with 95% CIs are reported for key comparisons.

Results

Acute sleep deprivation induces hyperalgesia

Mice were subjected to a 9-h mild stress-induced acute sleep deprivation protocol (08:30–17:30), with EEG and EMG signals monitored continuously to ensure effective sleep interruption (Fig. 1A and B). Compared with control animals, sleep-deprived (SD) mice exhibited a significant reduction in mechanical withdrawal thresholds (MWT) as assessed by the von Frey test (Fig. 1C). Similarly, hot-plate testing revealed a markedly shortened response latency in the SD group (Fig. 1D). These findings confirm that acute sleep deprivation induces hyperalgesia.

Acute sleep deprivation activates microglia in the hippocampal CA1 region and elevates proinflammatory cytokines

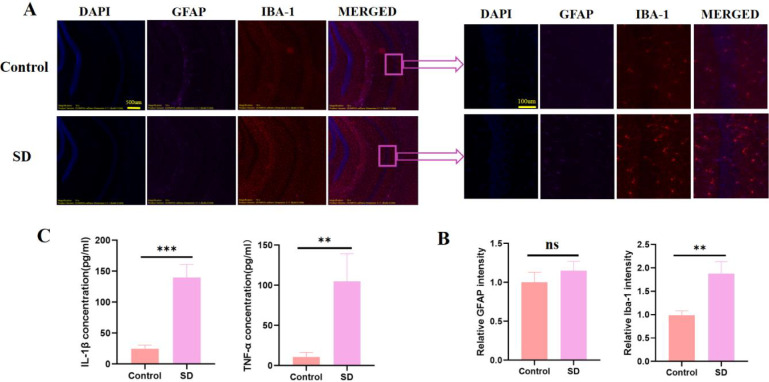

Given the role of central inflammation in sleep deprivation, we evaluated the activation of microglia and astrocytes in the hippocampal CA1 region. Immunofluorescence staining for IBA-1 (microglial marker) and GFAP (astrocytic marker) revealed that, relative to controls, SD mice displayed pronounced microglial activation, while astrocyte activation remained minimal (Fig. 2A and B). Correspondingly, ELISA assays demonstrated significantly elevated levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in the hippocampus of SD mice (Fig. 2C), suggesting that acute sleep deprivation selectively activates microglia and enhances proinflammatory cytokine production.

Fig. 2.

Acute sleep deprivation promotes microglial activation and elevates proinflammatory cytokines in the hippocampal CA1 region. A Representative immunofluorescence images of the hippocampal CA1 region from Control and SD mice. Sections were stained for DAPI (blue), GFAP (red), and IBA-1 (green). Merged images are shown in the right panels. B Quantification of the relative fluorescence intensities of GFAP and IBA-1 in the CA1 region. C ELISA measurements of IL-1β and TNF-α in hippocampal tissue. All data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns = not significant

Acute sleep deprivation activates P2X4 receptors in the hippocampus

Building on our previous work implicating the P2X4 receptor in pain modulation, we investigated its expression following acute sleep deprivation. Western blot analysis showed that while total P2X4 receptor levels remained unchanged, the phosphorylated (activated) form of P2X4 (p-P2X4) was significantly upregulated in the hippocampus of SD mice (Fig. 3A–C). In line with these findings, RT-qPCR analysis revealed no significant changes in P2X4 mRNA expression (Fig. 3D), underscoring that acute sleep deprivation primarily induces receptor activation rather than altering total receptor expression.

Fig. 3.

Acute sleep deprivation increases phosphorylated P2X4 receptor levels in the hippocampal CA1 region without altering total P2X4 expression. A Representative Western blot images of P2X4, p-P2X4, and GAPDH in hippocampal CA1 tissue from Control and SD mice. B Densitometric analysis showing a significant increase in the ratio of p-P2X4 to GAPDH in the SD group. C The ratio of total P2X4 to GAPDH was unchanged between the two groups. D mRNA expression of P2X4 (normalized to Control) also remained unaffected by SD. All data are presented as the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01, ns = not significant

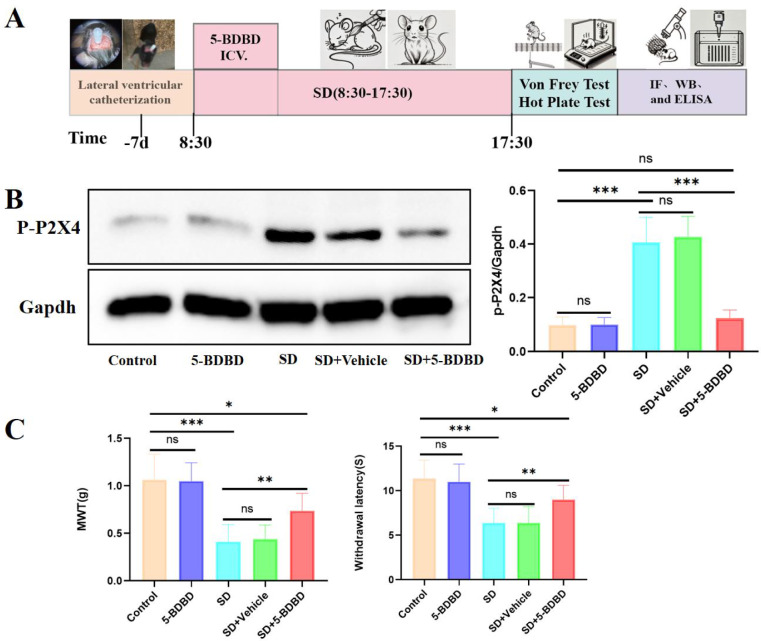

P2X4 receptor antagonism ameliorates sleep deprivation-induced hyperalgesia

To ascertain the role of P2X4 receptor activation in SD-induced hyperalgesia, mice received an intracerebroventricular injection of the selective P2X4 receptor antagonist 5-BDBD (10 µg in 2 µL PBS containing 0.5% DMSO) at the onset of sleep deprivation (Fig. 4A). In the SD + 5-BDBD group, hippocampal p-P2X4 levels were significantly reduced to near-control values (Fig. 4B). Behavioral assessments indicated that mice in SD + 5-BDBD group exhibited a significant increase in MWT and prolonged hot-plate response latencies compared with the SD group at T1–3 and exhibited a significant decrease in MWT and hot-plate response latencies compared with Control group (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that P2X4 receptor antagonism effectively mitigates SD-induced hyperalgesia, but cannot completely reverse it. The absence of statistically significant differences in behavioral outcomes across five mouse groups at 24-h post-sleep deprivation (SD) demonstrates that SD-induced hyperalgesia is transient.

Fig. 4.

P2X4 receptor antagonist alleviates acute sleep deprivation-induced mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in mice. A Schematic timeline of the experimental procedure. Mice underwent lateral ventricle catheterization 7 days prior to the onset of acute sleep deprivation (SD). The SD procedure was conducted from 8:30 to 17:30, at the onset of acute sleep deprivation, 5-BDBD was immediately administered via lateral ventricular injection. B Representative Western blot images of p-P2X4 and GAPDH in hippocampal CA1 tissue from Control, 5-BDBD, SD, SD + Vehicle and SD + 5-BDBD mice. Densitometric analysis showing the differences in the ratio of p-P2X4 to GAPDH between five groups. C Mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) in the Von Frey test and withdrawal latency in the hot-plate test were measured in the five groups at different time points. All data are presented as the mean ± SD, compare to Control group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; compare to SD + 5-BDBD group, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01

P2X4 receptor antagonism inhibits microglial activation

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying P2X4 receptor involvement in SD-induced hyperalgesia, we examined microglial activation and cytokine production. IBA-1 immunostaining in the hippocampal CA1 region revealed that administration of the P2X4 antagonist significantly reduced, but did not completely normalize, microglial activation compared to the SD group (Fig. 5A and B). In parallel, levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) were significantly lowered in the SD + 5-BDBD group relative to SD mice, though they remained above control levels (Fig. 5C and D). These results indicate that while P2X4 receptor antagonism partially attenuates microglial activation and cytokine release, additional pathways may also contribute to the hyperalgesic state induced by sleep deprivation.

Fig. 5.

P2X4 receptor antagonist ameliorated SD-induced microglial activation and inflammatory cytokine upregulation in the hippocampal CA1 region. A Representative immunofluorescence images of the hippocampal CA1 region from five groups. Sections were stained for DAPI (blue) and GFAP (red). Merged images are shown in the right panels. B Quantification of the relative fluorescence intensities of IBA-1 in the CA1 region. C and D ELISA measurements of IL-1β and TNF-α in hippocampal tissue. All data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that even a brief 9-h period of acute sleep deprivation is sufficient to induce significant hyperalgesia in mice, as evidenced by marked alterations in both mechanical and thermal nociceptive behaviors. Consistent with our previous work [17], we observed that sleep deprivation triggers the release of inflammatory cytokines; however, a key finding in this study is the selective activation of microglia in the hippocampal CA1 region without a concurrent activation of astrocytes.

The differential glial response is particularly noteworthy. While both microglia and astrocytes have been implicated in mediating central inflammatory responses [18], our data indicate that the stress imposed by 9 h of sleep deprivation is sufficient to activate microglia but does not reach the threshold necessary for astrocytic activation. Prior research suggests that astrocytes typically require a prolonged mild-to-moderate stress stimulus (exceeding 12 h) [19] or a more severe stressor to become activated [20], whereas microglia are more sensitive to even moderate disruptions in homeostasis [21]. This selective activation underscores the idea that distinct glial cell populations possess different activation thresholds in response to sleep-related stress.

A critical aspect of our findings is the activation of the P2X4 receptor. Although total P2X4 expression remained unchanged, the phosphorylated (activated) form of the receptor was significantly elevated in the hippocampus following sleep deprivation. The intracerebroventricular administration of the selective P2X4 antagonist 5-BDBD not only reduced p-P2X4 levels toward baseline but also partially attenuated microglial activation and the subsequent rise in proinflammatory cytokines, which in turn ameliorated hyperalgesia. These results strongly implicate P2X4 receptor-mediated microglial activation as a central mechanism by which acute sleep deprivation induces hyperalgesia.

It is important to acknowledge that the partial reversal of microglial activation and cytokine levels by 5-BDBD suggests that additional pathways contribute to the hyperalgesic state. Previous study had demonstrated that sleep deprivation can cause aberrant neuronal activity, leading to the release of danger signals such as ATP [22]. This extracellular ATP can activate microglia not only through P2X4 receptors but also via other purinergic receptors such as P2X7 [23]. Activation of P2X7 has been shown to initiate robust inflammatory responses [24]. Moreover, sleep deprivation has been reported to upregulate Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression, which promotes the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus, further enhancing the transcription and release of inflammatory cytokines [25]. In addition, a reduction in anti-inflammatory receptors on microglia—such as α7-nAChR—has been observed under sleep-deprived conditions, leading to a diminished capacity to restrain inflammatory responses [26, 27]. Thus, while P2X4 receptor activation appears to be a major driver of microglial-mediated hyperalgesia in this model, a confluence of receptor-mediated pathways likely underpins the full spectrum of sleep deprivation-induced neuroinflammation and pain sensitization.

Our study is among the first to demonstrate that P2X4 receptors, traditionally associated with peripheral neuropathic pain, play a critical role in central pain modulation in the context of acute sleep deprivation. The localization of P2X4 activation to the hippocampal CA1 region, a key area involved in pain processing, further supports its potential as a therapeutic target. However, it is essential to consider that other brain regions—such as the amygdala [28] and anterior cingulate cortex [29]—are also integral to the modulation of pain and may exhibit different responses to sleep deprivation. Future studies should extend these observations to include a broader analysis of central pain circuits.

In addition, our current model simulates the acute, anxiety-related insomnia often encountered in the perioperative period. In contrast, chronic sleep deprivation, which is common in other clinical scenarios, may lead to distinct physiological and cellular alterations [30, 31]. Future research should explore whether P2X4 receptors and their associated signaling pathways similarly contribute to hyperalgesia in chronic sleep loss models and how they interact with other inflammatory and neuromodulatory systems.

In summary, our findings reveal that acute sleep deprivation induces hyperalgesia through a mechanism that involves P2X4 receptor-mediated microglial activation and subsequent inflammatory cytokine release. This work not only provides new insights into the interplay between sleep disruption and pain modulation but also suggests that targeting P2X4 receptors—potentially in combination with other modulatory pathways—could represent a novel therapeutic strategy for managing perioperative pain and other conditions associated with sleep deprivation. While this study provides novel insights into P2X4-mediated hyperalgesia following sleep deprivation, several limitations should be acknowledged. Our exclusive use of male mice, while controlling for hormonal variability, precludes assessment of potential sex differences that may influence pain modulation—an important consideration given known sexual dimorphism in both sleep regulation and microglial function. The single 9-h timepoint analysis, though physiologically relevant for acute sleep deprivation, cannot reveal the temporal dynamics of P2X4 activation or recovery processes. Furthermore, while we focused on hippocampal CA1 mechanisms based on strong preliminary evidence, contributions from other pain-modulatory circuits remain unexplored. The current findings establish microglial P2X4 as a key mediator, yet downstream signaling pathways and potential interactions with astrocytic networks warrant further investigation. These limitations highlight important directions for future research while not diminishing the significance of our core findings regarding this novel sleep–pain interaction pathway.

Abbreviations

- P2X4

P2X4 subtype of purinergic receptor

- CA1

Hippocampal CA1 region

- 5-BDBD

5-(3-Bromophenyl)-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzofuro[3,2-e]-1,4-diazepin-2-one

- NK

Natural killer

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- ICV

Intracerebroventricular

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- EMG

Electromyography

- SD

Sleep deprivation

- NREM

Non-rapid eye movement

- MWT

Mechanical withdrawal threshold

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Xiaohong Du and Song Huang; methodology, Weiwen Cheng and Pengwei Lai; software, Shengliang Peng and Xinyuan Liu; validation, Song Huang and Xili Yang; formal analysis, Song Huang and Shengliang Peng; writing-original draft preparation, Song Huang and Weiwen Cheng; writing-review and editing, Xiaohong Du and Xili Yang; visualization, Song Huang and Xinyuan Liu; project administration, Xiaohong Du; funding acquisition, Song Huang and Xiaohong Du. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of the Jiangxi Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2025B0342).

Data availability

All data was uploaded as related files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was conducted in accordance with animal protocol procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Experimental Animal Center, Nanchang University.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Baranwal N, Yu PK, Siegel NS. Sleep physiology, pathophysiology, and sleep hygiene. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;77:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xin Q, Yuan RK, Zitting KM, Wang W, Purcell SM, Vujovic N, et al. Impact of chronic sleep restriction on sleep continuity, sleep structure, and neurobehavioral performance. Sleep. 2022. 10.1093/sleep/zsac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camberos-Barraza J, Camacho-Zamora A, Batiz-Beltran JC, Osuna-Ramos JF, Rabago-Monzon AR, Valdez-Flores MA, et al. Sleep, glial function, and the endocannabinoid system: implications for neuroinflammation and sleep disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jee HJ, Shin W, Jung HJ, Kim B, Lee BK, Jung YS. Impact of sleep disorder as a risk factor for dementia in men and women. Biomol Ther. 2020;28:58–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alam R, Quintero SL, Jahan N, Chodzko-Zajko W, Ogunjesa B, Selzer NA, et al. Relationships of low cognitive performance and sleep disorder with functional disabilities among older adults. J Aging Health. 2023;35:525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao X, Rui Y, Jin Y, Chen M. Relationship of sleep disorder with neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases: an updated review. Neurochem Res. 2024;49:568–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bin HM, Akhtar F, Sultana A, Tumrani S, Teelhawod BN, Abbasi R, et al. Role of oxidative stress and inflammation in insomnia sleep disorder and cardiovascular diseases: herbal antioxidants and anti-inflammatory coupled with insomnia detection using machine learning. Curr Pharm Des. 2022;28:3618–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cicek F, Ucar I, Seber T, Ulku DF, Ciftci AT. Investigation of the relationship of sleep disorder occurring in fibromyalgia with central nervous system and pineal gland volume. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2024. 10.1017/neu.2024.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doke M, McLaughlin JP, Baniasadi H, Samikkannu T. Sleep disorder and cocaine abuse impact purine and pyrimidine nucleotide metabolic signatures. Metabolites. 2022;12:869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato M, Yamamoto K. Sleep disorder and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Clin. 2021;17:369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu C, Wu Q, Li Y, Da M. Research trends and hotspots of sleep disorder and cancer: a bibliometric analysis via vosviewer and citespace. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32:223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo M, Wu Y, Zheng D, Chen L, Xiong B, Wu J, et al. Preoperative acute sleep deprivation causes postoperative pain hypersensitivity and abnormal cerebral function. Neurosci Bull. 2022;38:1491–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staffe AT, Bech MW, Clemmensen S, Nielsen HT, Larsen DB, Petersen KK. Total sleep deprivation increases pain sensitivity, impairs conditioned pain modulation and facilitates temporal summation of pain in healthy participants. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0225849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang WJ, Li X, Liao JX, Hu DX, Huang S. Schwann cells transplantation improves nerve injury and alleviates neuropathic pain in rats. Purinergic Signal. 2024. 10.1007/s11302-024-10046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu R, Li S, Li S, Gong X, Zhou G, Wang Y, et al. P2x4 receptor in the dorsal horn contributes to bdnf/trkb and ampa receptor activation in the pathogenesis of remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2021;750:135773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atta AA, Ibrahim WW, Mohamed AF, Abdelkader NF. Microglia polarization in nociplastic pain: mechanisms and perspectives. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31:1053–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang S, Wei G, Hua F. Fragmented sleep enhances postoperative neuroinflammation but not cognitive dysfunction: really? Anesth Analg. 2017;125:695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon HS, Koh SH. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl Neurodegener. 2020;9:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:7–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burda JE, Sofroniew MV. Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron. 2014;81:229–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucke-Wold BP, Smith KE, Nguyen L, Turner RC, Logsdon AF, Jackson GJ, et al. Sleep disruption and the sequelae associated with traumatic brain injury. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:68–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rifat A, Ossola B, Burli RW, Dawson LA, Brice NL, Rowland A, et al. Differential contribution of thik-1 k(+) channels and p2x7 receptors to atp-mediated neuroinflammation by human microglia. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santana PT, de Lima IS, Silva ESK, Barbosa P, de Souza H. Persistent activation of the p2x7 receptor underlies chronic inflammation and carcinogenic changes in the intestine. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:10874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin C, Zhang M, Cheng L, Ding L, Lv Q, Huang Z, et al. Melatonin modulates TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB signaling pathway to ameliorate cognitive impairment in sleep-deprived rats. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1430599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue R, Wan Y, Sun X, Zhang X, Gao W, Wu W. Nicotinic mitigation of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress after chronic sleep deprivation. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guvel MC, Aykan U, Paykal G, Uluoglu C. Chronic administration of caffeine, modafinil, AVL-3288 and CX516 induces time-dependent complex effects on cognition and mood in an animal model of sleep deprivation. Pharmacol Biochem. 2024;241:173793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hadeiy SK, Habtemariam S, Shankayi Z, Shahyad S, Sahraei H, Asghardoust RM, et al. Amelioration of pain and anxiety in sleep-deprived rats by intra-amygdala injection of cinnamaldehyde. Sleep Med X. 2023;5:100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sardi NF, Pescador AC, Azevedo EM, Pochapski JA, Kukolj C, Spercoski KM, et al. Sleep and pain: a role for the anterior cingulate cortex, nucleus accumbens, and dopamine in the increased pain sensitivity following sleep restriction. J Pain. 2024;25:331–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guillot P, Celle S, Barth N, Roche F, Perek N. “Selected” exosomes from sera of elderly severe obstructive sleep apnea patients and their impact on blood-brain barrier function: a preliminary report. Int J Mol Sci. 2024. 10.3390/ijms252011058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Runge N, Ahmed I, Saueressig T, Perea J, Labie C, Mairesse O, et al. The bidirectional relationship between sleep problems and chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pain. 2024;165:2455–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lou Q, Wei HR, Chen D, Zhang Y, Dong WY, Qun S, et al. A noradrenergic pathway for the induction of pain by sleep loss. Curr Biol. 2024;34:2644–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data was uploaded as related files.