Abstract

Telomerase, crucial for maintaining telomere integrity and genomic stability, is typically silenced in somatic cells with advancing age. In this study, we identify circHERC1 as a regulator of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) transcription. Specifically, circHERC1 binds to the TERT promoter, facilitating the recruitment of RNA polymerase II and c-Fos, thereby activating TERT expression. Notably, circHERC1 expression exhibits a decline with age, which correlates with reduced telomerase activity. Restoration of circHERC1 expression enhances telomerase activity, promotes telomere elongation, and reverses aging-associated phenotypes. Furthermore, delivery of circHERC1 using adeno-associated virus vectors or extracellular vesicles effectively restores telomerase activity, preserves telomere integrity, and mitigates senescence. This intervention leads to improvements in cognitive function, physical performance, and a reduction in inflammation. These findings highlight the important role of circHERC1 in telomerase regulation and the aging process, positioning it as a potential therapeutic target for antiaging interventions.

circHERC1 activates TERT transcription to counteract aging.

INTRODUCTION

Aging is a multifaceted process characterized by interconnected biological hallmarks, including telomere attrition (1–3), cellular senescence (4), genomic instability (5–7), chronic inflammation (8), epigenetic alterations (9), mitochondrial dysfunction (10), stem cell exhaustion (11), and altered intercellular communication (12), all of which collectively accelerate the aging process (13–15). Central to these processes is the progressive shortening of telomeres, the terminal regions of cellular chromosome, which are inherently limited in their replication through conventional mechanisms (2). Over the past two decades, substantial advancements have been made in identifying antiaging interventions that aim to reducing morbidity and extending the human life span (16–18). Among these interventions, telomerase has emerged as a particularly promising target due to its critical role in cellular aging and genomic stability (19, 20). The activation of telomerase can counteract telomere attrition, thereby delaying cellular senescence and promoting tissue regeneration (19, 21). Telomerase-based therapies have shown potential in mitigating diseases associated with premature telomere shortening, such as dyskeratosis congenital (22) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (23). The core catalytic unit of telomerase consists of two main components: telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and telomerase RNA (24). In normal somatic cells, TERT transcription is epigenetically silenced; however, it is highly activated in tumor and stem cells (11, 24). Activation of TERT not only maintains telomere integrity but also influences various processes such as cell survival, aging (25), neurogenesis (25), and stress resistance (26) by regulating gene expression and cell signaling pathways (2).

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are covalently closed endogenous biomolecules in eukaryotes, known for their tissue- and cell-specific expression patterns (27). Their biogenesis is controlled by distinct cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors (28, 29). By interacting with specific RNA and proteins, circRNAs function as microRNA sponges, protein decoys, and protein scaffolds (30, 31). Certain circRNAs containing internal ribosome entry site (IRES) elements and AUG sites can be translated under specific conditions, resulting in the production of unique peptides (32). In addition, circRNAs can form RNA-DNA hybrids with their producing locus to affect transcription (33, 34). Although the mechanism by which circRNA directly binds to DNA to activate transcription remains underexplored, preliminary studies suggest that circRNA may act as a transcriptional regulator by forming RNA-DNA hybrids or interacting with transcription factors (28, 35), highlighting its potential role in gene expression modulation and necessitating further investigation into its molecular functions.

In this study, we identify circHERC1 as a regulator of TERT transcription and telomere maintenance. We demonstrate that circHERC1 interacts with the TERT promoter via R-loops, facilitating the recruitment of transcription factors and RNA polymerase II, thereby activating TERT expression. Furthermore, we show that circHERC1 expression declines with age, correlating with reduced telomerase activity and telomere shortening. Restoring the expression of circHERC1 mitigates aging-related phenotypes, underscoring its therapeutic potential. These findings provide a foundation for circHERC1 as both a biomarker and therapeutic target for aging and age-related disorders.

RESULTS

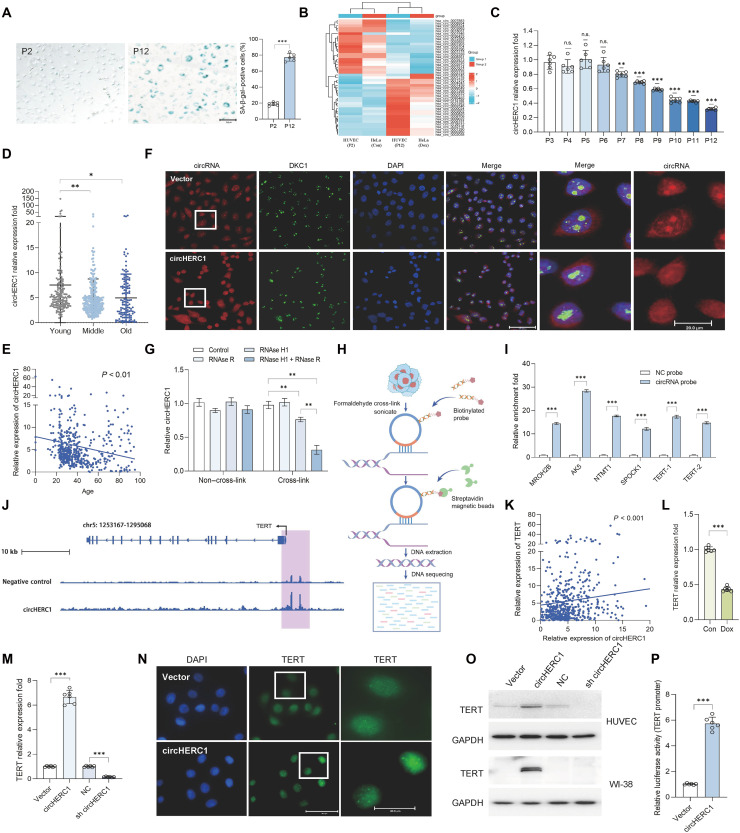

circHERC1 is associated with aging

To identify circRNAs essential for cellular senescence, we conducted circRNA sequencing analysis using a replicative senescence model of human umbilical cord endothelial cells (HUVECs) and a doxorubicin (Dox)-induced senescence model of HeLa cells. Senescence was assessed by evaluating senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal), p21, and p53 (Fig. 1A and fig. S1, A to C). Our analysis detected 45 distinct circRNAs associated with cell senescence, among which 24 circRNAs were up-regulated and 21 down-regulated in both senescent cells (Fig. 1B). To further explore the direct association of these circRNAs with cell senescence, we developed another two models: hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)–induced senescence model of HeLa cells and microdose lithium–treated HUVECs (fig. S1, D to G) (36–38). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis confirmed that circ_0035796, termed circHERC1 (39), was significantly down-regulated in senescent cells (Fig. 1C and fig. S1, H to K). To further investigate the relationship between circHERC1 down-regulation and aging, we examined circHERC1 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 524 healthy individuals aged from newborn to 95 years (data S1). The expression level of circHERC1 was highest in the young population, moderate in the middle-aged group, and lowest in the elderly population (Fig. 1D) (40), with a gradual decrease observed with age (Fig. 1E). These results imply that circHERC1 is closely linked to senescence.

Fig. 1. circHERC1 is associated with aging.

(A) Representative images of SA-β-gal staining of HUVECs at passage 2 (P2) and P12. (B) Heatmap of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data showing differential expression of circRNAs between HUVEC (P2 and P12) and HeLa (control and Dox treatment) cells. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of circHERC1 expression across cell passages in HUVECs (P3 to P12). n.s., not significant. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of circHERC1 expression in the PBMCs from healthy donors. Young (under 29 years of age), middle (from 30 to 49 years of age), and old (more than 50 years of age). (E) Correlation analysis between the expression of circHERC1 in the PBMCs from healthy donors and age. (F) Fluorescence images of circHERC1 [fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH); red], Dyskerin 1 (DKC1) [immunofluorescence (IF); green], and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) in circHERC1-overexpressing HeLa cells and Vector control cells. (G) qRT-PCR analysis of circHERC1 in HeLa cells after ribonuclease (RNase) R and RNase H1 digestion. (H) The diagram of circRNA-based chromatin isolation by RNA purification (CHIRP). (I) The enrichment of candidate genes by RNA pull-down with circHERC1-specific probe and negative control (NC) probe in HeLa cells. (J) CHIRP analysis indicating circHERC1 binding to genomic loci near the TERT promoter. (K) Correlation analysis between the expression of circHERC1 and TERT in the PBMCs from healthy donors. (L) qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of circHERC1 in HeLa cells treated with Dox. Con, control. (M) qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of TERT following circHERC1 overexpression or knockdown in HUVECs. (N) IF images of TERT in circHERC1-overexpressing HeLa cells and Vector control cells. (O) Western blot analysis of TERT following circHERC1 overexpression or knockdown in HUVEC (up) and WI-38 (down) cells. (P) TERT promoter luciferase assay after circHERC1 manipulation in 293FT cells. N values are shown within the panels. All values are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

To further explore the cellular localization and potential function of circHERC1, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for circHERC1 and immunofluorescence (IF) for Dyskerin 1 (DKC1), a known nucleolar marker (41), in circHERC1-overexpressing HeLa cells. The FISH and IF analyses revealed that circHERC1 is localized in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, mainly colocalizing with DKC1 in the nucleolus (Fig. 1F). However, in circHERC1-overexpressing HeLa cells, the nucleolar aggregation and the colocalization with DKC1 of circHERC1 in nucleus disappeared (Fig. 1F). We hypothesized that circHERC1 has the capacity to form specific structural domains, thereby facilitating interactions with homologous genomic DNA through sequence-based associations (42). To investigate this potential interaction, we evaluated circHERC1 stability following treatment with ribonuclease (RNase) H1, an endonuclease that specifically cleaves RNA within RNA-DNA hybrids. Notably, RNase H1 treatment resulted in circHERC1 degradation when HeLa cells were cross-linked before RNA extraction (Fig. 1G and fig. S2, A and B), indicating that circHERC1 may participate in nucleic acid interactions susceptible to RNase H1 cleavage.

Subsequent circRNA-based chromatin isolation by RNA purification (CHIRP) assays followed by DNA sequencing analysis (Fig. 1H) revealed that circHERC1 significantly enriched numerous DNA fragments, with an increase observed when circHERC1 was overexpressed (fig. S2C). A considerable portion of DNA fragments were located in the promoter region of genes (data S2). Given the enrichment of circRNA in the mammalian brain (43, 44), and circHERC1’s enrichment in the mouse brain and reproductive system (fig. S2D), we focused on the promoters of genes predominantly expressed in these tissues, including TERT, SPOCK1, NTMT1, MROH2B, and AK5 (fig. S2, E to I). The enrichment of these promoters was confirmed by RNA pull-down analysis (Fig. 1I), and their expression levels were up-regulated with circHERC1 overexpression (fig. S2J), suggesting that circHERC1 may activate their transcription. Notably, two regions of the TERT promoter were enriched (Fig. 1J). TERT down-regulation was also observed in senescent cells at both mRNA and protein levels (fig. S2, K and L), and a positive correlation between TERT and circHERC1 expression was identified in healthy donors (fig. S2, M to O). This suggests that circHERC1 regulates TERT expression at the transcriptional level. Correlation analysis in PBMCs confirmed a significant positive relationship between circHERC1 and TERT across all age groups, implicating circHERC1 in TERT regulation during aging (Fig. 1K).

TERT expression was significantly decreased in HeLa cells treated with Dox and H2O2 but up-regulated with LiCl treatment (Fig. 1L and fig. S2, P to R). qRT-PCR, Western blot, and IF analyses demonstrated that TERT expression at both mRNA and protein levels increased in HeLa and HUVECs transfected with circHERC1 while reduced markedly in those with circHERC1 knockdown (Fig. 1, M to O, and fig. S2S). circHERC1 reactivated TERT expression in WI-38 cells where TERT was silenced (Fig. 1O and fig. S2T). We constructed a luciferase reporter vector containing a 4853–base pair (bp) TERT promoter (−4841/+11), and luciferase reporter assays indicated that circHERC1 could activate the TERT promoter (Fig. 1P), supporting the notion that circHERC1 directly modulates TERT expression at the transcriptional level. Collectively, these data demonstrate that circHERC1 is crucial in regulating TERT expression.

circHERC1 binds the TERT promoter to regulate TERT transcription

To illustrate the mechanism by which circHERC1 activates TERT transcription, we first identified critical sequences in the TERT promoter associated with circHERC1 by analyzing their homology. Our analysis revealed seven homologous binding sites. We constructed a series of promoter constructs, each linked to a luciferase reporter gene, from the 4853-bp promoter sequence to investigate these sites (Fig. 2A). Transient transfection of 293FT cells demonstrated that deletion of circHERC1 binding sites 1 (CB1), CB3, and CB7 significantly reduced promoter activity in response to circHERC1, with a truncated construct lacking these sites showing nearly 80% loss of activity (Fig. 2A and fig. S3A). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and PCR analyses of pull-down products using a circHERC1-specific probe confirmed significant enrichment at CB1, CB3, and CB7 in both HeLa and HUVECs (Fig. 2B and fig. S3, B and C). However, digestion assays using site-specific restriction endonucleases Msp I and Ms II revealed that CB3 and CB7 fragments exhibited resistance to cleavage when HeLa cells were cross-linked before DNA extraction (Fig. 2, C and D). This resistance to digestion suggests a direct interaction between circHERC1 and the TERT promoter region, potentially occluding the restriction enzyme recognition sites.

Fig. 2. circHERC1 activates TERT transcription by binding TERT promoter.

(A) Schematic diagram of truncated TERT promoter constructs used to identify regulatory regions targeted by circHERC1. The promoter regions CB1, CB3, and CB7 were highlighted as key elements in TERT transcription regulation. hTERT, human TERT. (B) Enrichment of TERT at the CB1, CB3, and CB7 promoter regions measured by qPCR after using circRNA-specific probes. (C) Msp I hypersensitivity and cross-linking assays confirmed that CB3 was an accessible and active chromatin site. (D) Ms II hypersensitivity and cross-linking assays confirmed that CB7 was an accessible and active chromatin site. (E) Site-directed mutagenesis of the CB1, CB3, and CB7 regions abolishing circHERC1-mediated transcriptional activation in 293FT cells, demonstrating that these regions are indispensable for the effect of circHERC1 on TERT promoter activity. (F) Luciferase assay assessing TERT promoter activity in response to various circHERC1 constructs in 293FT cells. (G) qRT-PCR analysis of TERT in 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 and circHERC1 TERT binding site 1 (TB1), TB3, and TB7 mutant. (H) Western blot analysis of TERT in 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 and circHERC1 TB1, TB3, and TB7 mutant. (I) Immunoprecipitation assay confirming an interaction between circHERC1 and RNA polymerase II in HeLa cells. pol, polymerase. (J) RNA pull-down assay demonstrated that circHERC1 bound RNA polymerase II. (K) circHERC1 mutations in polymerase II binding site 1 (PB1) and PB2 regions reduce TERT transcription. (L) The enrichment of RNA polymerase II pulled down by circHERC1-specific probe in 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 PB mutations. (M) qRT-PCR analysis of TERT in 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 and circHERC1 PB mutant. (N) Western blot analysis of TERT in 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 and circHERC1 PB mutant. (O) Immunoprecipitation assay confirming an interaction between circHERC1 and c-Fos in HeLa cells. (P) RNA pull-down assay demonstrated that circHERC1 binds c-Fos in HeLa cells.

To confirm the necessity of the circHERC1-TERT promoter interaction for TERT activation, we mutated the circHERC1 binding sites in the TERT promoter and the corresponding sites in circHERC1 (fig. S3D). Mutations at CB1, CB3, and CB7 in the TERT promoter abolished its response to circHERC1 (Fig. 2E), while mutations at TERT binding site 1 (TB1), TB3, and TB7 in circHERC1 failed to activate the TERT promoter (Fig. 2F). In addition, the enrichment of circHERC1 binding sites in the TERT promoter, as pulled down by a circHERC1-specific probe, was reduced in 293FT cells transiently transfected with circHERC1 TB mutations (fig. S3E). Furthermore, circHERC1 with mutations at TB1, TB3, and TB7 could not efficiently activate TERT expression in 293FT cells (Fig. 2, G and H, and fig. S3H).

To further elucidate the molecular mechanism of circHERC1-mediated TERT activation, we performed an RNA pull-down assay, followed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis to identify circHERC1-binding proteins. Among the 565 proteins identified (data S3 and fig. S3F), RNA polymerase II and AP-1 transcription factors were of particular interest. RNA polymerase II and AP-1 play crucial roles in regulating gene expression and influencing cellular processes such as proliferation and differentiation (45). RNA polymerase II was enriched in circHERC1 pull-downs via RNA binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays (Fig. 2I), and circHERC1-specific probes could also pull down RNA polymerase II (Fig. 2J). We predicted that circHERC1 contains two RNA polymerase II binding sites (PB) (fig. S3, D and G); mutations in these sites abolished circHERC1’s response to the TERT promoter (Fig. 2K). The enrichment of RNA polymerase II pulled down by circHERC1-specific probes decreased when 293FT cells were transiently transfected with circHERC1 PB mutations (Fig. 2L). As expected, circHERC1 with PB1 and PB2 mutations failed to activate TERT expression in 293FT cells (Fig. 2, M and N, and fig. S3I). We further investigated whether AP-1 transcription factors were involved in the circHERC1-RNA polymerase II complex. Analysis revealed that c-Fos, but not c-JUN, was part of this complex (Fig. 2, O and P, and fig. S3, J and K). IF analysis showed that circHERC1 colocalized with polymerase II and c-Fos (fig. S2, L and M), providing additional evidence of their interaction and suggesting that circHERC1 recruits RNA polymerase II and c-Fos to the TERT promoter, leading to transcriptional activation.

Collectively, these findings demonstrated that circHERC1 directly interacted with the key regions of TERT promoter to induce its transcription. By binding to specific regions such as CB1, CB3, and CB7, circHERC1 recruited transcription factors such as c-Fos and polymerase II to the TERT promoter, resulting in TERT activation. These insights contribute significantly to our understanding of TERT transcriptional regulation, highlighting the critical role of circHERC1 in cellular processes such as aging and senescence.

circHERC1 effectively elongates the telomere to counteract cell senescence

We investigated telomerase activity using the telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay and observed a reduction in telomerase activity in aging cells (Fig. 3A). Telomerase serves to counteract replication-associated telomere shortening, with its activity primarily regulated by the expression of TERT (46, 47). Our observations indicated that the telomere length of HUVECs progressively shortens with increasing cell divisions, correlating with a gradual decrease in circHERC1 and TERT expression (Figs. 1C and 3B and fig. S2K). In healthy individuals, the telomere length in PBMCs was longest in the young population, moderate in the middle aged, and shortest in the elderly, showing a positive correlation with circHERC1 expression levels and age (Fig. 3C and fig. S4, A and B). Genetic variation analysis of CB1, CB3, and CB7 in the TERT promoter region among healthy donors revealed mutations in CB1 in a subset of individuals (data S1). Among this CB1 mutant population, the positive correlations between circHERC1 expression and age, TERT expression, and telomere length were absent (Fig. 3, D and E, and fig. S4, C and D).

Fig. 3. circHERC1 effectively elongates the telomere to counteract cell senescence.

(A) TRAP analysis of P3 and P12 HUVECs for telomerase activity (32 PCR circles). (B) Telomere length analysis of HUVECs at P3 to P12. (C) Telomere length–circHERC1 correlation in PBMCs of healthy donors. (D) Correlation of circHERC1 and TERT expression in PBMCs (healthy donors; CB1 site mutant). (E) Telomere length–circHERC1 correlation in PBMCs (healthy donors; CB1 site mutant). (F) TRAP analysis of HUVECs after circHERC1 overexpression and knockdown (32 PCR circles). (G) Telomere length in HUVECs after circHERC1 overexpression and knockdown. (H) Western blot of TERT in Dox-treated circHERC1-modified HeLa cells. (I) TRAP analysis of HeLa cells treated with Dox or not (28 PCR circles). (J) TRAP analysis of HeLa cells treated with H2O2 or not (28 PCR circles). (K)Telomere length of HeLa cells following circHERC1 overexpression and knockdown under conditions of DNA damage or oxidative stress. (L) TRAP analysis of 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 and TB mutant (27 PCR circles). (M) TRAP analysis of 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 and PB mutant (29 PCR circles). (N) Telomere length of 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 and TB mutant. (O) Telomere length of 293FT cells transfected with circHERC1 and PB mutant. (P) Replicative life span of HUVECs with or without circHERC1 transfection. (Q) SA-β-gal staining of HUVECs after circHERC1 overexpression and knockdown. (R) Western blot of p21 and p53 in HUVECs after circHERC1 overexpression and knockdown. (S) Western blot of phospho-H2A.X in HUVECs after circHERC1 overexpression and knockdown. (T) SA-β-gal staining of HeLa cells transfected with circHERC1 and its mutants (Dox-treated). (U) Western blot of p21 and p53 in HeLa cells transfected with circHERC1 and circHERC1 PB1 and PB2 mutant. (V) Western blot of p21 and p53 in HeLa cells transfected with circHERC1 and circHERC1 TB1, TB3, and TB7 mutant. N values are shown within the panels. All values are means ± SEM.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

In HUVECs, telomerase activity, as determined by TRAP, increased with circHERC1 overexpression and decreased significantly with circHERC1 knockdown (Fig. 3F). Alterations in telomere length were observed following interventions in circHERC1 expression, which corresponded with changes in telomerase activity (Fig. 3G). Similar results were noted in HeLa and WI-38 cells, where circHERC1 overexpression led to TERT up-regulation, increased telomerase activity, and extended telomere length, while circHERC1 knockdown had the opposite effect (Fig. 3, H to K, and fig. S4, E to H). To assess circHERC1’s role in counteracting telomere attrition in induced cell senescence models, we evaluated telomerase activity and telomere length. Dox exposure in HeLa cells resulted in reduced telomerase activity and substantial telomere shortening, while circHERC1 overexpression resisted (Fig. 3, I and K, and fig. S4, I to M). H2O2 induced oxidative stress and premature senescence in HeLa cells, reducing telomerase activity and shortening telomeres; these effects were reversed by circHERC1 overexpression (Fig. 3J and fig. S4, N to R). Lithium has been suggested to affect telomere length (48), and in vitro assessments indicated that low-dose lithium increased telomerase activity and prolonged telomere length in HUVECs, effects reversed by circHERC1 knockdown (Fig. 3K, and fig. S4, S to U). Mutations in circHERC1 at TB1, TB3, and TB7 or PB1 and PB2 hindered its ability to activate TERT expression, enhance telomerase activity, elongate telomere, and resist to Dox-induced telomere shortening (Fig. 3, L to O, and fig. S4, V to Y). These findings confirm that circHERC1 is critical for telomere protection under oxidative stress and chemotherapy-induced damage.

Normal somatic cells face a proliferative limit due to the end-replication problem, reaching the “Hayflick limit” (49), which can be overcome by telomerase activation (50). Overexpression of circHERC1 in primary HUVECs significantly enhanced proliferation, whereas circHERC1 knockdown reduced the proliferation rate (fig. S5, A to C). HUVECs with circHERC1 overexpression exhibited increased cell passage numbers compared to the controls (Fig. 3P). The number of SA-β-gal staining–positive cells decreased upon circHERC1 overexpression, whereas it increased following circHERC1 knockdown (Fig. 3Q). The senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) genes (51), such as p21 and p53, were also inhibited by circHERC1 (Fig. 3R). circHERC1 knockdown resulted in increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and DNA damage (Fig. 3S and fig. S5D). circHERC1 alleviated cellular senescence induced by Dox and H2O2 in HeLa cells, accompanied by SASP gene inhibition (fig. S5, E to G). Conversely, circHERC1 with TB1, TB3, and TB7 or PB1 and PB2 mutations lost this ability (Fig. 3, T to V). These results suggest that circHERC1 plays a critical role in maintaining telomere integrity, promoting telomerase activity, and delaying cellular senescence under both basal and stress conditions. By regulating telomerase activity and protecting against oxidative stress–induced damage, circHERC1 functions as an important modulator of cellular longevity.

circHERC1 activates TERT to preserve telomeres in vivo

To explore whether circHERC1 could activate TERT transcription in vivo, we inserted a construct containing a loxP-flanked stop cassette between the chicken-actin promoter and a sequence encoding circHERC1, which was then integrated into the ROSA26 locus in mice using CRISPR-Cas9–mediated homologous recombination (fig. S6, A and B). Transgenic mice (Rosa26LSL-circHERC1) were crossed with inducible Cre transgenic mice (Rosa26CreERT2). Tamoxifen-induced expression of circHERC1 in Rosa26LSL-circHERC1/CreERT2 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) was confirmed at both DNA and RNA levels (Fig. 4A and fig. S6C), showing a significant increase in circHERC1 levels after tamoxifen treatment. 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assays (fig. S6D) indicated that tamoxifen-induced circHERC1 expression significantly enhanced cell proliferation rates. The replicative capacity, assessed by the number of passages over time, was significantly greater in tamoxifen-treated circHERC1-expressing cells compared to the untreated controls (Fig. 4B). qPCR analysis revealed that TERT expression was significantly elevated in tamoxifen-treated MEF cells (Fig. 4C). TRAP analysis demonstrated a significant increase in telomerase activity in tamoxifen-treated MEF cells, especially in those treated with higher tamoxifen concentrations (Fig. 4D). These findings were furtherly supported by qPCR analysis of telomere length, which showed progressive elongation of telomeres in tamoxifen-treated cells (Fig. 4E). In addition, tamoxifen treatment led to a significant increase in telomerase activity in both younger and older MEF cells (fig. S6E). These results strongly suggest that circHERC1 overexpression promotes telomerase activity and enhances telomere maintenance, potentially contributing to the observed extension of replicative life span in circHERC1-overexpressing MEF cells.

Fig. 4. circHERC1 activates TERT to preserve telomere length in vivo.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of human circHERC1 and mouse circHERC1 in MEF cells derived from transgenic mice following tamoxifen (Tam) treatment. (B) Replicative life span of MEF cells from circHERC1 transgenic mice following Tam treatment. Tg, transgenic. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of TERT in MEF cells derived from transgenic mice following Tam treatment. (D) TRAP analysis of MEF cells derived from transgenic mice following Tam treatment (29 circles in PCR). (E) qPCR analysis of relative telomere length in MEF cells from circHERC1 transgenic mice treated with Tam. (F) Western blot analysis of TERT and p21 protein expression in young (P3) and old (P10) MEF cells derived from circHERC1 transgenic mice. (G) SA-β-gal staining in young and old MEF cells derived from circHERC1transgenic mice. (H) qRT-PCR analysis of circHERC1 expression in various tissues of circHERC1 transgenic mice. (I) Western blot analysis of TERT in various tissues of circHERC1 transgenic mice compared to controls. (J) Longitudinal analysis of telomere length in the tails of circHERC1 transgenic mice and controls. (K) qPCR analysis of relative telomere length in multiple tissues from male circHERC1 transgenic mice and controls. (L) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis of serum interleukin-11 (IL-11) levels in circHERC1 transgenic mice and controls. (M) ELISA analysis of serum IL-6 levels in the serum of circHERC1 transgenic mice and controls. (N) Results from the open field test (center distance) in circHERC1 transgenic mice and controls. (O) Tail suspension test (climbing time) assessing depressive-like behavior in circHERC1 transgenic mice and controls. (P) Elevated plus maze test (open arm entry times) assessing anxiety-like behavior in circHERC1 transgenic mice and controls. N values are shown within the panels. All values are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Next, we assessed the effects of circHERC1 overexpression on cellular senescence. MEF cells from circHERC1 transgenic mice treated with tamoxifen showed a significant reduction in p21 expression and ROS accumulation, while TERT levels were elevated in both young and old cells (Fig. 4F and fig. S6, F and G). SA-β-gal staining revealed that circHERC1 overexpression significantly reduced the number of SA-β-gal–positive cells in both young and old MEF cells (Fig. 4G and fig. S6H), suggesting that circHERC1 may play an important role in extending the life span of cells by preventing the onset of senescence. We then examined circHERC1 expression and its effects on telomere length across various tissues in circHERC1 transgenic mice. qPCR analysis revealed that circHERC1 was overexpressed in multiple tissues, including liver, spleen, kidney, and reproductive tissues (Fig. 4H), while the expression of mouse circHERC1 in the tissues of transgenic mice was similar to the controls (fig. S6, I and J). Western blot analysis further confirmed the up-regulation of TERT protein levels in several tissues, suggesting that circHERC1 expression influences TERT at the protein level as well (Fig. 4I). Long-term monitoring of telomere length in mouse tails revealed sustained telomere preservation in circHERC1 transgenic mice compared to controls (Fig. 4J). Longitudinal analysis of telomere length across multiple tissues revealed that circHERC1 overexpression led to significantly longer telomeres in both male and female mice (Fig. 4K and fig. S6K). This telomere elongation suggests that circHERC1 overexpression has systemic effects on telomere maintenance, enhancing telomere stability and delaying age-associated telomere attrition.

We also investigated the impact of circHERC1 overexpression on systemic inflammation by measuring cytokine levels in the serum of circHERC1 transgenic mice. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis revealed that interleukin-11 (IL-11) (8) and IL-6 (52) levels were significantly reduced in both male and female transgenic mice compared to the controls (Fig. 4, L and M). To assess the functional consequences of circHERC1 overexpression, we performed several behavioral assays. In the open field test, circHERC1 transgenic mice exhibited increased exploratory behaviors, evidenced by longer distances traveled and more time spent in the center of the arena (Fig. 4N). In the tail suspension test, circHERC1 transgenic mice showed reduced immobility times, indicating that circHERC1 overexpression alleviates depressive-like behavior (Fig. 4O). Similarly, in the elevated plus maze test, circHERC1 transgenic mice spent more time in the open arms of the maze (Fig. 4P and fig. S6L). In the forced swim test, circHERC1 transgenic mice exhibited reduced immobility times, reflecting an antidepressive effect (fig. S6, M and N). In the open field test, circHERC1 transgenic mice demonstrated improved physical performance (fig. S6O). Grip strength tests showed that circHERC1 transgenic mice exhibited significantly greater force compared to the controls (fig. S6P). Novel object recognition and Morris water maze testing demonstrated improved spatial learning and memory retention in circHERC1 transgenic mice. These mice showed shorter escape latencies and more frequent platform crossings during the probe test (fig. S6, Q to T). These behavioral assessments strongly support that circHERC1 can improve significant cognitive and physical performances in mice. In addition, circHERC1 transgenic mice also showed enhanced bone density and strength, as demonstrated by MicroCT analysis, along with reduced subcutaneous fat reduction, as shown by histological analysis in both male and female circHERC1 transgenic mice (fig. S6, U to W), further indicating the broad impact of circHERC1 on tissue health. These findings suggest that circHERC1 is crucial for activating TERT to maintain telomere length in vivo, thereby reducing cellular senescence and enhancing tissue integrity and overall systemic function.

To investigate the effects of circHERC1 induction in aged mice, we administered tamoxifen to aged mice to induce circHERC1 expression (fig. S7A). This induction led to a corresponding increase in TERT expression (fig. S7B) and resulted in significantly longer telomeres in multiple tissues in both male and female mice, as demonstrated by longitudinal telomere length analysis (fig. S7C). These findings were further corroborated in 20-month-old circHERC1 transgenic mice (fig. S7, D to F). Furthermore, these aged transgenic mice exhibited improved cognitive abilities, reduced levels of inflammatory factors, and increased bone density to varying degrees (fig. S7, G to M). Together, these results indicate that circHERC1 effectively up-regulates TERT expression, leading to improvements in several age-related physiological functions in aged mice, suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy for mitigating age-related decline.

Adeno-associated virus–mediated circHERC1 delivery ameliorates aging

To investigate the systemic effects of circHERC1, we administered adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors carrying circHERC1 (AAVcircHERC1) to aged mice (Fig. 5A). Tissue-specific expression analysis via qRT-PCR confirmed robust circHERC1 expression across various organs in both male and female mice (Fig. 5B). Notably, AAVcircHERC1-treated mice exhibited improvements in physical conditions, including healthier fur, overall appearance, and hair growth restoration (Fig. 5C). SA-β-gal staining indicated a reduction in senescent cells across tissues in circHERC1-treated animals, particularly in metabolically active organs such as the livers and kidneys, compared to the controls (Fig. 5, D and E, and fig. S8, A and B). Immunohistochemical analysis further demonstrated a significant reduction in senescence and DNA damage markers in multiple organs of circHERC1-treated animals, although not in the brain and testis (Fig. 5F, and fig. S8, C to H).

Fig. 5. Effects of AAV-mediated circHERC1 overexpression in aged mice.

(A) Schematic representation of the experimental design. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of circHERC1 expression levels in different tissues from male and female mice treated with AAVcircHERC1. (C) Representative images showing the improved physical condition of male and female AAVcircHERC1-treated mice compared to controls at age of 17 months. (D) SA-β-gal staining of various tissues from AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice compared to controls. (E) Representative of SA-β-gal staining images of lung, liver, and kidney tissues from AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice compared to controls. (F) Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for p16 and phospho-H2A.X in tissues of AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice and controls. (G) Metabolic cage experiment [respiratory exchange ratio (RER)] measuring activity levels and metabolic function in AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice and controls. (H) ELISA measurements of IL-11 in serum samples from AAVcircHERC1-treated mice and controls. (I) ELISA measurements of IL-6 in serum samples from AAVcircHERC1-treated mice and controls. (J) Open field test (velocity) between AAVcircHERC1-treated mice and controls. (K) Grip strength test (force weight) between AAVcircHERC1-treated mice and controls. (L) Western blot analysis of TERT and p21 in tissues from AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice and controls. (M) Telomere shortening rate measured in the tails of AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice and controls. (N) qRT-PCR analysis of TERT expression in various tissues from AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice and controls. (O) qPCR analysis of relative telomere length in multiple tissues from AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice and controls. N values are shown within the panels. All values are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

To evaluate the impacts of circHERC1 overexpression on metabolic functions, we conducted metabolic cage experiments. AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice showed improved overall metabolic performances, indicating enhanced physical activity and metabolic health (Fig. 5G and fig. S9, A to E). The influence of circHERC1 on inflammation was assessed by measuring cytokine levels in the serum of AAVcircHERC1-treated mice. Lowered levels of IL-11 and IL-6 were detected, suggesting that circHERC1 may modulate the inflammatory responses, potentially promoting tissue repair and reducing age-related tissue damage (Fig. 5, H and I). Behavioral and cognitive performances were evaluated through various tests. In the open field test, AAVcircHERC1-treated mice exhibited increased exploratory behavior, as indicated by greater distances traveled and more time spent in the center of the arena, consistent with enhanced exploratory behaviors linked to better physical and emotional well-being (Fig. 5J). The grip strength test revealed significantly higher muscle strength in AAVcircHERC1-treated mice, further indicating improved physical health and muscular functions associated with circHERC1 overexpression (Fig. 5K). Additional behavioral tests, including the elevated plus maze and tail suspension test, demonstrated reduced anxiety-like behavior and enhanced muscle functions in AAVcircHERC1-treated mice (fig. S9, F to K). The novel object recognition test indicated better memories in treated mice, and the Morris water maze test showed improved spatial learning and memories, as evidenced by faster escape latencies (fig. S9, L to Q). Behavioral testing in both sexes revealed that overexpressing circHERC1 reduced anxieties and improved physical functions.

Western blot analysis of TERT and p21 was performed to assess the molecular effects of circHERC1 overexpression on telomere maintenance and cellular senescence. AAVcircHERC1-treated male mice exhibited significantly up-regulated TERT levels and reduced p21 levels in liver, lung, and kidney tissues, suggesting enhanced telomerase activity and reduced cellular senescence (Fig. 5L and fig. S9R). Telomere shortening rates were also assessed, revealing that AAVcircHERC1-treated mice had a significantly slower rate of telomere shortening compared to the controls, indicating maintenance of telomere integrity and delayed telomere attrition (Fig. 5M and fig. S9S). Elevated TERT expression in the livers, lungs, and kidneys of treated mice supported the conclusion that circHERC1 enhances telomerase activity and promotes telomere stability (Fig. 5N and fig. S9T). qPCR analysis further confirmed significantly longer telomeres in multiple tissues of AAVcircHERC1-treated mice compared to the controls, including the hearts, livers, and kidneys (Fig. 5O and fig. S9U). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that circHERC1 enhances physical health, reduces cellular senescence, improves metabolic functions, and enhances cognitive performances, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic agent for aging-related diseases.

Extracellular vesicle–mediated circHERC1 delivery counters aging

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of circHERC1-overexpressing extracellular vesicles (EVs) (EVcirc), we engineered 293FT cells to overexpress circHERC1, and the resulting EVs were isolated. qRT-PCR confirmed successful overexpression of circHERC1 in the cells (fig. S10A), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) demonstrated that the isolated EVs exhibited typical exosomal morphology (fig. S10B). Further characterization using Western blot and nanoparticle tracking analysis revealed enrichment of exosomal markers (ALIX, TSG101, and CD9) and an appropriate size distribution (fig. S10, C and D). The presence of circHERC1 in the EVs was verified by qRT-PCR (fig. S10E).

The effects of EVcirc were first examined in HUVECs, and the expression of TERT mRNA expression was increased after EVcirc treatment (Fig. 6A). Western blot analysis showed a significant up-regulation of TERT and a reduction of p21 levels in EVcirc-treated cells compared to the controls treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or empty EVs (EV), suggesting that EVcirc enhanced telomerase activity and reduced cellular senescence (Fig. 6B). TRAP confirmed a marked increase in telomerase activity (Fig. 6C), while qPCR demonstrated significantly longer telomeres in EVcirc-treated cells compared to controls (Fig. 6D). In addition, SA-β-gal staining showed a reduction in senescent cells in the EVcirc-treated group, further supporting the antisenescence effects of EVcirc (Fig. 6E). Collectively, these findings indicate that EVcirc enhances telomerase activity, promotes telomere elongation, and reduces cellular senescence in vitro.

Fig. 6. Evaluation of EVcirc on aging in vitro and in vivo.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of TERT in HUVECs treated with PBS, empty EVs (EV), or EVcirc. (B) Western blot analysis of TERT and p21 expression in HUVECs treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (C) TRAP analysis of HUVECs treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc (32 circles in PCR). (D) qPCR analysis of telomere length in HUVECs treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (E) SA-β-gal staining of HUVECs treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (F) Western blot analysis of p21 and TERT in tissues from male mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (G) qPCR analysis of relative telomere length in various tissues from male mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (H) qPCR analysis of relative telomere length in various tissues from female mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (I) SA-β-gal staining of various tissues from male mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (J) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of testis from male mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (K) IHC staining of p16 and phospho-H2A.X in brains and testes of male mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (L) MicroCT analysis of bone density in female mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. BV, bone volume; TV, total volume. (M) ELISA measurements of IL-11 in serum from mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (N) Metabolic cage experiment (RER) in male mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. (O and P) Morris water maze test of male mice treated with PBS, EV, or EVcirc. N values are shown within the panels. All values are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

To investigate the in vivo effects of EVcirc, we treated mice with these EVs (fig. S11A). qRT-PCR analysis of various tissues revealed increased TERT expression alongside reduced p16 and p21 levels in EVcirc-treated mice, indicative of enhanced telomerase activity and diminished cellular senescence (fig. S11, B to G). Western blot analysis of tissues such as the livers, lungs, kidneys, and intestines corroborated these findings, showing up-regulation of TERT and down-regulation of p21 (Fig. 6F and fig. S10H). Telomere length analysis by qPCR demonstrated significantly longer telomeres in EVcirc-treated mice compared to PBS- and EV-treated controls, suggesting preserved telomere integrity (Fig. 6, G and H).

Phenotypically, EVcirc-treated mice exhibited improved physical conditions, including healthier fur and better overall appearance, compared to controls and even those treated with AAVcirc (fig. S12A and movies S1 to S4). Telomere shortening was significantly slowed in both male and female mice, as shown by telomere length analysis in tail tissues (fig. S12, B and C). SA-β-gal staining of tissues revealed reduced cellular senescence in EVcirc-treated mice, indicating a reduction in age-associated cellular damage (Fig. 6I and fig. S12, D to F). In male mice, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of testis tissues showed improved tissue integrity following EVcirc treatment, suggesting protection against aging-related reproductive tissue degeneration (Fig. 6J). Immunohistochemical analysis of p16 and phospho-H2A.X further supported these findings, showing reduced expression of these markers in various tissues from EVcirc-treated mice (fig. S13). Notably, EVcirc treatment demonstrated more pronounced antiaging effects compared to AAVcircHERC1, with particularly evident rejuvenation in the brain and testicular tissues (Fig. 6K and fig. S8, G and H).

MicroCT analysis revealed improved bone health in EVcirc-treated mice, with significantly higher bone mineral density and enhanced bone structure compared to PBS and EV controls (Fig. 6L and fig. S12, G and H). These findings suggest that EVcirc may prevent aging-associated bone loss, offering potential therapeutic applications for conditions such as osteoporosis. To assess inflammation, we measured serum levels of IL-11 and IL-6 using ELISA, revealing significantly lower levels in EVcirc-treated mice compared to the controls, indicative of reduced systemic inflammation and enhanced tissue repair (Fig. 6M and fig. S12I). Metabolic cage experiments further demonstrated improved metabolic function in EVcirc-treated mice, as evidenced by increased energy expenditure, higher oxygen consumption, and elevated carbon dioxide production (Fig. 6N and fig. S12, J to N). Behavioral tests provided additional evidence of the therapeutic benefits of EVcirc. In the Morris water maze test, EVcirc-treated male mice exhibited faster escape latencies compared to the controls, indicating enhanced cognitive function (Fig. 6, O and P, and fig. S14, A and B). Performance improvements were also observed in other behavioral tests, such as the open field test and elevated plus maze, suggesting enhanced physical activity, reduced anxiety, and improved overall behavioral outcomes (fig. S14, C to O).

In summary, EVcirc significantly enhances telomerase activity, reduces cellular senescence, preserves telomere integrity, and improves multiple health parameters in aging mice. Notably, these EVs exhibited tissue-specific rejuvenation effects, particularly in brain and testicular tissues, underscoring their potential as a therapeutic intervention for combating aging.

DISCUSSION

This study elucidates the role of circHERC1 as a key modulator of cellular senescence and aging, primarily achieved through its contribution to telomere maintenance and the attenuation of age-associated decline. Mechanistically, circHERC1 augments telomerase activity by promoting TERT transcription through direct interaction with the TERT promoter. This interaction facilitates the recruitment of essential transcription factors, including RNA polymerase II and c-Fos, ultimately delaying telomere attrition and alleviating cellular senescence (fig. S15). These findings provide a mechanistic framework for understanding the influence of circRNAs on aging at the molecular level, offering previously unidentified insights into the complex interactions between noncoding RNAs and aging-related pathways.

The age-dependent down-regulation of circHERC1 in senescent cells, coupled with its gradual decline observed in human PBMCs across different age groups, positions it as a potential biomarker for aging. This reduction in circHERC1 expression correlates with decreased TERT levels and telomere shortening, suggesting that the loss of circHERC1 may contribute to the progressive decline in cellular function observed during aging. Notably, restoring circHERC1 expression in aging models, both in vitro and in vivo, reverses these effects, highlighting its therapeutic potential (13, 53, 54). The ability of circHERC1 to activate TERT transcription and maintain telomere integrity provides a compelling explanation for its antiaging effects, as telomere maintenance is a well-established determinant of cellular life span and organismal aging (2, 19, 55).

The systemic delivery of circHERC1 via AVV vectors and EVs represents a significant advancement in antiaging therapeutics (56, 57). In aged mice, AAV-mediated circHERC1 overexpression not only preserved telomere length but also improved physical health, reduced senescence markers, and enhanced cognitive function (Fig. 5). These beneficial effects were accompanied by TERT up-regulation and the down-regulation of senescence-associated genes such as p21 and p16 (58, 59), demonstrating the broad impact of circHERC1 on cellular and tissue homeostasis. Similarly, EVs containing circHERC1 exhibited potent antiaging effects, including telomere elongation, reduced inflammation, and improved metabolic and cognitive performance (Fig. 6). The rejuvenation of tissues such as the brain and testis further emphasizes the therapeutic potential of circHERC1 for age-related diseases (60, 61).

EVs, naturally occurring nanovesicles, present a promising avenue for delivering therapeutic circRNAs due to their inherent ability to traverse biological barriers, including the blood-brain barrier, and target specific tissues, enabling access to traditionally hard-to-reach organs (62, 63). Further enhancing their therapeutic utility is their biocompatibility and low immunogenicity, which minimizes the risk of adverse effects. A particularly compelling aspect of this study is the observed ability of EV-mediated circHERC1 delivery to rejuvenate both the brain and testis, two tissues especially vulnerable to age-related decline (62, 64–66). In the brain, circHERC1 overexpression via EVs significantly improved cognitive function, as evidenced by enhanced performance in behavioral tests such as the Morris water maze and novel object recognition (Fig. 6, O and P, and fig. S13). Mechanistically, these improvements correlated with reduced senescence markers, decreased DNA damage, and increased TERT expression in brain tissues, suggesting that circHERC1 exerts a protective effect against age-related neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. Given the brain’s high metabolic demands and susceptibility to oxidative stress, the capacity of circHERC1 to enhance telomerase activity and mitigate oxidative damage may underlie its potent neuroprotective effects (67, 68). Similarly, in the testes, EV-mediated circHERC1 delivery demonstrated the capacity to restore tissue integrity and function, as evidenced by histological analysis and the reduction of senescence markers (Fig. 6, J and K). Age-related testicular decline is typically marked by diminished spermatogenesis and hormonal production, resulting in reduced fertility and systemic hormonal imbalances (69, 70). The observed rejuvenation of testicular tissues following circHERC1 treatment suggests a potential role for circHERC1 in maintaining reproductive health and delaying age-related gonadal decline. This finding carries particular significance considering the increasing awareness of the interconnectedness between reproductive and systemic aging and the potential for circHERC1-based therapeutics to address age-related infertility disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human cell culture

293FT cells were procured from Invitrogen. HeLa cells were procured from the American Type Culture Collection. HUVECs were obtained from Bena Cell Collection. WI-38 cells were acquired from the China Center for Type Culture Collection. HUVECs were cultured in extracellular matrix supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% endothelial cell growth supplement, streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and penicillin (100 U/ml). Meanwhile, 293FT cells, HeLa cells, and WI-38 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS. All cell cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and at least 95% relative humidity.

Mice

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Welfare Ethics Committee of the Beijing Institute of Biotechnology and in accordance with the Basel Declaration. Aged C57BL/6 mice, Dppa3-IRES-Cre mice (catalog no. NM-KI-00040), and Rosa26-CreERT2 mice (catalog no. NM-KI-200041) were purchased from Shanghai Model Organisms Center Inc. All animals were housed in pathogen-free, ambient temperature (20° to 25°C), 45 to 55% humidity, and 12-hour dark/light cycle conditions and cared for in accordance with the International Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care policies and certification.

MEF cell culture

To isolate MEFs from Rosa26LSL-circHERC1/CreERT2 mouse embryos at 12.5 to 14.5 days of gestation, a series of precise steps was followed under sterile conditions. Initially, the abdomen of the pregnant mouse was carefully dissected to excise the uterine horns, which were then rinsed thoroughly in a sterile 50-ml Falcon tube containing PBS to remove residual blood. Subsequently, the embryos were disinfected by immersion in a 75% ethanol solution for 15 min. Following disinfection, the yolk sac and placenta were meticulously removed from the embryos using sterile scalpels or scissors. The embryonic tissue was washed twice with PBS to eliminate any remaining blood and transferred to a fresh sterile petri dish. The embryos were further processed by discarding the tails, heads, and internal organs, including the heart and liver. The remaining fetal tissue was finely minced into small fragments, ~1 to 2 mm in diameter, using a sterile scalpel. These minced tissue fragments were collected into a 15-ml centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 2 min. The resulting tissue slurry was evenly distributed into two 50-ml conical tubes. For cell dissociation, the tissue fragments were incubated at 37°C for 15 min with 5 ml of 0.25% trypsin/EDTA per embryo. Following incubation, the enzymatic activity was neutralized by adding MEF culture medium, which consists of DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 10% glutamine, 10% nonessential amino acids, and 10% penicillin-streptomycin solution. The cell suspension was centrifuged again at 1000 rpm for 2 min, and the supernatant was carefully discarded. The cell pellet was resuspended in fresh MEF culture medium and transferred to a culture flask. Last, the cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 to 3 days to facilitate attachment and expansion.

PBMCs from healthy donors

Healthy donors for blood collection were required to fast for 8 to 12 hours before collection. Venous blood was drawn from the antecubital vein using a sterile, single-use vacuum blood collection system. Approximately 2 to 5 ml of whole blood was collected into EDTA-coated tubes to prevent coagulation. Immediately after collection, the tubes were gently inverted several times to ensure proper mixing with the anticoagulant. For the isolation of PBMCs, an equal volume of PBS was added to the blood and gently mixed. This blood-PBS mixture was then carefully layered onto an equivalent volume of lymphocyte separation medium in a new 15-ml centrifuge tube. The tube was centrifuged at 500g for 15 min at 4°C, resulting in the separation of the sample into three distinct layers. The whitish buffy coat, containing the PBMCs, was carefully aspirated from the interphase between the histopaque and the medium, ~1 ml in volume. The supernatant was discarded, and 1 ml of red blood cell lysis buffer was added to resuspend the cells, which were subsequently transferred to a 1.5-ml EP tube. To obtain purified PBMCs, the cells were washed twice by centrifugation at 100g for 10 min with 10 ml of sterile PBS.

Method details

Cell transfection and stable cell line

To establish stable cell lines overexpressing circHERC1, 293FT, HUVEC, WI-38, and HeLa cells were transduced with a lentivirus carrying either the circHERC1 overexpression construct or a control vector. Following transduction, stable transductions were selected by treating the cells with puromycin (2 μg/ml; Invitrogen, USA) for a minimum of 4 weeks. However, for HUVECs and WI-38, the selection period was limited to 5 days to mitigate the risk of cellular senescence. In parallel, to generate stable circHERC1 knockdown cell lines, the cells were infected with a lentivirus expressing either a control vector or sh-circHERC1. The selection of stable knockdown lines was similarly conducted using puromycin (2 μg/ml; Invitrogen, USA). These genetically modified cell lines were subsequently used for further experimental investigations and analyses.

EdU incorporation assay

Initially, cells were seeded onto Nunc Lab-Tek II Chamber Slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and cultured until they reached the desired confluence. Subsequently, EdU was added to the culture medium at a concentration of 10 μM for duration of 3 hours to facilitate its incorporation into replicating DNA. Postlabeling, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized, and incubated with Click Additive Solution containing Alexa Fluor 594 or 488 (EdU Cell Proliferation Kit, BeyoClick, China) for 30 min in the dark. After washing, cells could be counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize nuclei. The analysis of EdU incorporation was conducted using fluorescence microscopy to quantify the percentage of proliferating cells, with fluorescence intensity indicating the number of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle (71).

Cell viability assay

HUVECs were plated into 96-well plates at a density of 2000 cells per well. These cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for various time intervals, specifically at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. Following incubation, 10 μl of CCK-8 solution (Dojindo, Japan) were added to each well, and the plates were further incubated at 37°C for an additional 2 hours. Subsequently, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader, which allowed for the assessment of cell viability.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from both cultured cells and PBMCs using the Ambion PureLink Total RNA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and quantified with a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, USA). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Invitrogen, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and using either random or oligo(dT) primers. The cDNA was then amplified using the THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Japan) on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, USA). To verify the PCR products, they were subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and Sanger sequencing. RPL13 served as an internal control for normalizing mRNA expression levels. The relative RNA levels were determined using the standard 2–ΔΔCt method.

Western blot assay

Cells/tissues were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with protease inhibitors to extract the total protein. The protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, USA). Subsequently, the total protein was separated by 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto 0.22- or 0.4-μm polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were then blocked with 5% skim milk powder and incubated overnight at 4°C with specific primary antibodies. The primary antibodies used for the analysis included anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), anti-p21, anti–c-Fos, anti-TSG101, anti-Alix, anti-CD9, anti-p53, anti-TERT, and anti–RNA Polymerase II. Following the primary antibody incubation, the membranes were treated for 1 hour at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein bands were subsequently visualized using an ECL detection system (Bio-Rad, USA). GAPDH served as the internal control for the experiment.

RNA sequencing

For RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, RNA was isolated from the cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). To ensure the integrity and purity of the RNA, its quality was assessed following extraction. Subsequently, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was removed from the RNA sample using the Ribo-off rRNA depletion kit (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). The RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA, which was fragmented and adapted with specific barcodes and primers to prepare it for sequencing. The cDNA libraries thus prepared were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. The raw sequencing data obtained underwent processing and analysis, wherein the reads were aligned to a reference human genome (hg38/GRCh38) or transcriptome.

Dox-induced cell senescence

To induce cellular senescence with Dox (72), cells were initially cultured in an appropriate growth medium and then exposed to Dox at a final concentration of 75 nM for 72 hours. Following this treatment period, the medium was replaced with fresh, Dox-free medium, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 hours. Throughout the experiment, changes in cell morphology were regularly monitored using light microscopy. To evaluate the induction of senescence, the SA-β-gal activity assay was subsequently performed.

H2O2-induced cell senescence

HeLa cells were exposed to H2O2 at a final concentration of 600 μM for duration of 2 hours (73). After the treatment, the cells were transferred to a medium devoid of H2O2 and cultured for an additional 4 days. Throughout this period, daily observations of cell morphology were conducted using light microscopy to detect any morphological changes.

HUVECs treated with lithium

HUVECs were initially treated with 1 mM either LiCl or NaCl for duration of 4 days, with the culture medium being refreshed every 2 days. Following this treatment phase, the cells underwent a washing process and were subsequently transferred to a medium devoid of LiCl or NaCl, as applicable. The cells were then maintained in this new medium for an additional week. At the conclusion of this 1-week period, cellular senescence was evaluated using relevant senescence markers and assays.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

A CY3-labeled circHERC1 probe was synthesized by ReBio Technology Co. Ltd. HeLa cells were cultured until they reached 60 to 80% confluence, after which they were fixed with 4% PFA. FISH was then conducted using a FISH kit provided by ReBio Technology Co. Ltd, in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (74). The fixed cell slides were subsequently examined using a Nikon ECLIPSE confocal microscope to capture images for further analysis.

IF staining

Cells were initially cultured on Lab-Tek II Chamber Slides (Nunc, USA) under standard conditions. Upon reaching the desired confluence, the cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 to 20 min at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 to s10 min and incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin for 30 to 60 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were treated with primary antibodies, including anti–c-Fos, anti-TERT, anti-DKC1, and anti–RNA polymerase II for 1 to 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. After thorough washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Following additional washes, the cell nuclei were stained with DAPI for 5 to 10 min. Fluorescence images were captured with a fluorescence or confocal microscope equipped with appropriate filter sets.

FISH and IF staining in HeLa cells

HeLa cells were seeded into chamber slides and cultured until adherence (75, 76). Cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature, followed by three washes with PBS (5 min each). Permeabilization was performed using 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, and cells were washed three times with PBS. Chamber slides were then placed in a humidified chamber, and blocking was carried out with 20% serum at 37°C for 30 min. Primary antibodies (anti–RNA Polymerase II C-terminal repeat domain, anti–c-Fos, and anti-DKC1) diluted in antibody dilution buffer were added, and slides were incubated overnight at 4°C. After three PBS washes, a 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:300 dilution) was applied and incubated at room temperature for 60 min, followed by three PBS washes. Cells were treated with 75% ethanol for 15 min at room temperature and blocked again using blocking solution (RiboBio, China) at 37°C for 30 min. A 1 μM circHERC1 probe mixture was added, and hybridization was performed overnight at 37°C for 16 hours. Posthybridization, slides were washed sequentially with prewarmed hybridization wash buffers I (4× SSC and 0.1% Tween 20), II (2× SSC), and III (1× SSC) at 42°C in the dark, followed by a final wash with 1× PBS at room temperature. Slides were mounted with DAPI and imaged using fluorescence microscopy.

Cell cross-linking

Cells were cultured to an appropriate density and washed with PBS to remove the culture medium. The cells were then treated with trypsin, followed by centrifugation to collect the cell pellets. The pellets were washed three times with PBS to remove any residual culture medium and subsequently resuspended in 5 ml of 1% formaldehyde cross-linking solution. The cells were incubated at room temperature for 10 min to facilitate cross-linking. Following the incubation, 500 μl of 1.25 M glycine solution was added to terminate the cross-linking reaction. The cells were washed twice with PBS, collected using a cell scraper, and transferred to a six-well plate. The plates were left uncovered and placed on ice. The cells were then subjected to cross-linking treatment using the UVP Crosslinker (Analytik Jena; an Endress+Hauser Company), with 3 cycles of ultraviolet cross-linking, each lasting 10 min. After extracting the DNA following cross-linking, the DNA was digested separately with two restriction enzymes, Msp I and Ms II (New England Biolabs, USA). A 50-μl digestion reaction mixture was prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. The digestion efficiency was assessed by PCR analysis.

Rnase R or Rnase H1 digestion

RNase R and RNase H1 treatments were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Initially, total RNA (2 μg) was incubated with 3-U RNase R (Geneseed, China) at 37°C for 20 min. RNase R, an RNase known for its ability to enrich circRNAs by degrading linear RNAs in mixed RNA samples, was then inactivated by heating at 70°C for 5 min. In addition, RNase H1, an endonuclease that specifically degrades the RNA strand of RNA-DNA hybrids, was used. RNA was extracted from both cross-linked and non–cross-linked cells and subsequently divided into three experimental groups: one treated with RNase R, another with RNase H1, and a third with both RNase R and RNase H1. Following these treatments, the expression levels of linear mRNA and circRNA were assessed using qRT-PCR.

RNA pull-down

A biotin-labeled 30-nucleotide probe, designed to target the reverse splicing site of circHERC1 (sequence: GUCCUGGUUUUCUGAUAUCUGAUAGUG), was used to study RNA/RNA or RNA/protein interactions (77). As a negative control, a biotin-labeled probe containing a coding sequence (sequence: UGCUUUGCACGGUAACGCCUGUUUU) was used. Cells, either cross-linked or non–cross-linked, were harvested and lysed in an appropriate lysis buffer supplemented with RNase inhibitors to prevent RNA degradation. The clarified cell lysate was incubated with the biotinylated RNA probe at 4°C for 1 to 2 hours with gentle rotation or shaking, facilitating the binding of the probe to interacting proteins. Following incubation, Pierce streptavidin-conjugated beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were introduced to the mixture, allowing streptavidin to bind to the biotinylated RNA and enabling the pull-down of RNA-protein complexes. Subsequently, the beads were washed multiple times with a high salt and detergent buffer to eliminate nonspecifically bound proteins and contaminants. The RNA-protein complexes were then eluted by incubating the beads with an elution buffer, releasing them from the beads. Specific RNA binding proteins were identified using antibodies through Western blot, and the enrichment of specific RNA species following pull-down was verified by RT-PCR/qRT-PCR.

RIP assay

RIP assays (78) were conducted using a Magna RIP kit (Millipore, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 1 × 107 HeLa or 293FT cells were harvested and lysed in RIP lysis buffer and then incubated with Dynabeads protein G conjugated with anti–immunoglobulin G (IgG), anti–c-Fos, and anti–RNA polymerase II using a Magna RIP kit (Merck, USA). The immunoprecipitated RNAs were extracted for the detection of circRNA expression by qRT-PCR.

Luciferase activity assay

The luciferase activity was measured to compare cells transfected with wild-type TERT promoter constructs against those with truncated or mutated versions. 293FT cells were cotransfected with these vectors and a sea urchin expression plasmid in a 24-well plate using Lipofectamine 2000. After a 24-hour transfection period, cells were lysed with passive lysis buffer (Promega, USA), and the expression of the luciferase reporter gene was evaluated using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, USA).

circRNA-based CHIRP assay

The culture medium was aspirated from the dish, and 5 ml of 1% formaldehyde solution was added (79). The solution was gently mixed and incubated at room temperature for 10 min to allow cross-linking of the cells. Next, 500 μl of 1.25 M glycine solution was added, mixed gently, and incubated at room temperature for 5 min to quench the cross-linking reaction. The solution was aspirated from the dish, and 1 ml of prechilled 1× PBS was added. The cells were scraped into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube, and the tube was centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 3 min at 4°C to collect the cell pellet. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of prechilled 1× PBS by pipetting, and the cells were centrifuged again at 1200 rpm for 3 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was lysed in chromatin immunoprecipitation buffer, and the chromatin was sheared into 100- to 500-bp fragments using a sonicator. The mixture was incubated with a biotin-labeled circHERC1-specific probe for 2 hours at room temperature to capture the RNA-DNA complexes. The beads were washed extensively to remove nonspecific interactions, and the RNA-DNA complexes were eluted. Cross-links were reversed by heating at 65°C overnight, followed by proteinase K treatment to digest proteins. Last, the RNA and DNA were purified for downstream analysis.

SA-β-gal staining

Cells in a 12-well plate were initially washed with PBS and subsequently fixed by adding 1 ml of fixation solution for 15 min at room temperature. Following fixation, the cells underwent three washes with PBS, each lasting 3 min. β-galactosidase staining was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Beyotime, China). The staining solution was prepared and incubated at 37°C overnight, and the cellular aging status was evaluated using an optical microscope. For tissue staining, the mouse organs of interest were dissected and fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature. Postfixation, the tissues were washed three times with PBS to eliminate excess fixative. The pH of the β-galactosidase staining solution was adjusted to 5.0 using citric acid (80). Tissues were then immersed in the β-galactosidase staining solution and incubated at 37°C without agitation for 3 to 24 hours, depending on the tissue type. Specific staining durations were as follows: spleen (3 hours), stomach (4 hours), intestines (4 hours), kidney (5.5 hours), lung (8 hours), heart (16 hours), and muscles (24 hours). The reaction was terminated by rinsing the tissues in PBS to remove excess staining solution, after which photographs were taken. Subsequently, tissues were paraffin embedded and sectioned into 8-μm slices using a microtome. Nuclei were stained with 1% nuclear fast red solution for further analysis.

Detection of ROS using the DCFH-DA probe

The 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) working solution was prepared by diluting DCFH-DA in serum-free medium at a ratio of 1:1000, resulting in a final concentration of 10 μM. The procedure was initiated by removing the culture medium from the cells, followed by the addition of an appropriate volume of the diluted DCFH-DA solution to ensure the cells were fully covered (81). For example, at least 1 ml of the diluted solution was added per well in a six-well plate. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 min to allow for the uptake of DCFH-DA. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with serum-free medium to remove any uninternalized DCFH-DA. The resulting fluorescence images were obtained using a laser scanning confocal microscope.

Telomeric repeat amplification protocol assay

The TRAP assay was conducted utilizing the TRAPeze® Telomerase Detection Kit (Merck, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol (82). Briefly, cells were trypsinized, and the enzymatic activity of trypsin was quenched with culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were then washed with PBS and harvested by centrifugation. Lysis was achieved by resuspending the cell pellet in CHAPS lysis buffer, using a volume three to four times that of the pellet, and supplemented with RNase inhibitor (1:200 dilution) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100 dilution). This suspension was incubated on ice for 30 minutes to ensure complete lysis. Following lysis, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was then determined using a BCA protein assay kit. Based on anticipated telomerase activity, 100 ng of protein was used for the subsequent TRAP assay. The appropriate concentration of TRAP dilution buffer was determined, and the stock solution was diluted accordingly with CHAPS buffer. PCR amplification was then performed, with the number of cycles optimized for each cell type (27-30 cycles for HeLa and MEF cells; 32 cycles for HUVECs). Finally, 10 μL of the PCR product was subjected to gel electrophoresis for analysis.

Telomere length quantification

The Absolute Human (ScienCell, USA) and Mouse (ScienCell, USA) Telomere Length Quantification qPCR Assay Kit was used to accurately measure the average telomere length. Initially, genomic DNA was extracted from the samples using a standard DNA extraction method. The DNA concentration was then quantified, and the DNA was diluted to an appropriate concentration. Following this preparation, the qPCR Reaction Mix was prepared, and the qPCR was conducted under the following standard cycling conditions: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, annealing at 52°C for 20 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s. Upon completion of the amplification cycles, the qPCR results were analyzed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (83).

circHERC1 knockin transgenic mice

CRISPR-Cas9–mediated homologous recombination was used to insert the CAG-LoxP-Neo-STOP-Neo-STOP-LoxP-circRNA-pA expression cassette into the Rosa26 locus of C57BL/6J mice. First, Cas9 mRNA and target-specific guide RNA (gRNA) were synthesized via in vitro transcription. A donor vector was constructed using In-Fusion cloning, which included a 3.3-kb 5′ homologous arm, the CAG-LoxP-Neo-STOP-Neo-STOP-LoxP-circRNA-pA expression cassette, and a 3.3-kb 3′ homologous arm. Subsequently, Cas9 mRNA, gRNA, and the donor vector were coinjected into fertilized eggs of C57BL/6J mice via microinjection. The injected embryos were then transferred into pseudopregnant female mice to generate F0 offspring. Genotyping was performed to identify F0 mice with the correct insertion of the expression cassette. This approach enables the conditional expression of circRNA, which can be activated upon Cre-mediated removal of the Neo-STOP cassette.

Tamoxifen-induced circHERC1 expression in transgenic mice

For tamoxifen-induced Cre-mediated recombination, 19-month-old mice received intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen prepared in corn oil at a dose of 120 mg/kg of body weight every other day for a total of five injections, while control mice were administered an equivalent volume of corn oil vehicle alone following the same schedule; following the final injection, a washout period of 3 weeks was observed to allow for clearance of tamoxifen and its active metabolites before subsequent experimental procedures.

Mouse tail DNA extraction

A 0.5-cm segment of mouse tail tissue was initially placed into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and kept on ice. Subsequently, 400 μl of digestion buffer and 1 μl of a Proteinase K solution (25 mg/ml) were added to each tube. The samples were incubated overnight at 50°C, with occasional inversion to ensure thorough mixing. The following day, 200 μl of saturated NaCl solution were introduced into each tube. After vigorous shaking, the tubes were incubated on ice for 10 min. The samples underwent centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, after which the supernatant was carefully collected. To this supernatant, 1 ml of 100% ethanol was added, followed by thorough mixing. The samples were centrifuged again at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the resulting pellet was collected. The pellet was then resuspended in 100 μl of double-distilled water (ddH2O2) and incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 hours to allow for complete DNA resolution.

Isolation and characterization of EVs

The culture supernatant of 293FT cells and 293FT cells overexpressing circHERC1 was collected. Initial centrifugation at 300g for 10 min was performed to remove whole cells, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. A subsequent centrifugation at 2000g for 10 min was conducted to eliminate cellular debris. The clarified supernatant was then placed in a fresh sample bottle for EV isolation using a high-efficiency exosome isolation system (EXODUS H-600, Huixin Lifetech). EVs were retrieved from the chip by pipetting with 1 ml of PBS for further analyses. Nanoflow cytometry was used to assess the particle concentration, size distribution, and phenotypic characteristics of the isolated exosomes. In addition, TEM was used to examine their morphology. The expression of common EV markers, such as CD9, CD63, CD81, Alix, and TSG101, was analyzed via Western blotting, with calnexin serving as a negative control (84).

AAV delivery via tail vein injection in age mice

Fourteen-month-old C57BL/6 mice were administered a 100-μl solution containing 5.0 × 1011 particles of either AAVcon or AAVcirc via tail vein injection (85). The AAV particles were diluted in PBS to achieve the desired concentration. Before injection, the tail vein was dilated using a heat lamp to facilitate the procedure. The injection was performed slowly to ensure proper delivery and minimize leakage. The treated mice were sent for behavior analysis 3 months after AAV injection.

EV delivery via tail vein injection in aged mice