Abstract

Ca2+ oscillations are required in various signal trans duction pathways, and contain information both in their amplitude and frequency. Remarkably, the Ca2+/calmodulin(CaM)-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) can decode such frequencies. A Ca2+/CaM-stimulated autophosphorylation leads to Ca2+/CaM-independent (autonomous) activity of the kinase that outlasts the initial stimulation. This autonomous activity increases exponentially with the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Here we show that three β-CaMKII splice variants (βM, β and βe′) have very similar specific activity and maximal autonomy. However, their autonomy generated by Ca2+ oscillations differs significantly. A mechanistic basis was found in alterations of the CaM activation constant and of the initial rate of autophosphorylation. Structurally, the splice variants differ only in a variable ‘linker’ region between the kinase and association domains. Therefore, we propose that differences in relative positioning of kinase domains within multimeric holoenzymes are responsible for the observed effects. Notably, the β-CaMKII splice variants are differ entially expressed, even among individual hippocampal neurons. Taken together, our results suggest that alternative splicing provides cells with a mechanism to modulate their sensitivity to Ca2+ oscillations.

Keywords: alternative splicing/calcium oscillation/CaMKII/frequency

Introduction

A variety of cellular stimuli such as action potentials, neurotransmitters, hormones and antigens lead to transient changes in cytosolic free Ca2+, in the form of Ca2+ spikes, sparks, puffs and waves, which give rise to localized Ca2+ oscillations (for a review, see Berridge et al., 2000; Bootman et al., 2001). Such Ca2+ signals can encode information in their kinetics, spike numbers and frequencies. Thus, cells must locally express appropriate molecu lar decoders capable of translating such Ca2+ signals into specific downstream signaling events.

Ca2+/calmodulin(CaM)-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is a major mediator of Ca2+-based signals and regulates a large variety of cellular functions, including carbohydrate metabolism, gene expression, cell cycle, neurotransmitter synthesis and release, membrane excitability, and different forms of synaptic plasticity that may underlie learning and memory (for a review, see Malenka and Nicoll, 1999; Schulman and Braun, 1999; Soderling et al., 2001; Hudmon and Schulman, 2002). CaMKII possesses key attributes to differentially decode localized Ca2+ oscillations. (i) It specifically targets to distinct cellular compartments, such as the nucleus (Srinivasan et al., 1994; Brocke et al., 1995), actin filaments (Ohta et al., 1986; Shen et al., 1998), post-synaptic densities (PSD) (Kennedy et al., 1983; Shen and Meyer, 1999; Bayer et al., 2001; Dosemeci et al., 2001) and intracellular membranes (Bayer et al., 1998). (ii) It can, remarkably, translate the number and frequencies of Ca2+ oscillations into different levels of activity (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998).

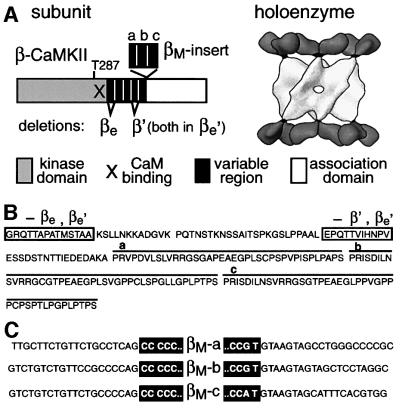

The ability of CaMKII to extract spatial and temporal information from Ca2+-mediated signals is largely based on its unique structural arrangement, with 12 kinase subunits symmetrically assembled into hub- and spoke-like holoenzymes (Kanaseki et al., 1991; Kolodziej et al., 2000) (see also Figure 1A). Each subunit contains a C-terminal association domain and an N-terminal kinase domain that includes the regulatory region with the Ca2+/CaM binding site. This topology is shared by the highly homologous α, β, γ and δ isoforms, which are encoded by four different genes. Additionally, each CaMKII gene gives rise to multiple splice variants that differ in a variable region, which is thought to comprise the linker between the kinase and association domains seen in the holoenzyme structure (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1. Structure of β-CaMKII splice variants. (A) Primary structure of the β-CaMKII splice variants in a schematic representation (left), and CaMKII holoenzyme structure (Kolodziej et al., 2000) (right). (B) The variable region of β-CaMKII. Amino acid sequences missing in βe′ are boxed. The lines above the sequence indicate the three βM-specific repeats. (C) Intron/exon borders of the three βM-specific exons (black boxes) as determined by further sequence analysis of the murine β-CaMKII locus (for complete βM exon sequences see Bayer et al., 1999; more intron sequences at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession Nos AF416336 and AF416337).

It is important to note that CaMKII can form both homo- and hetero-multimeric holoenzymes. Differential targeting of the large holoenzymes is actually controlled by specific insertion of subunits that contain unique targeting domains, such as in the CaMKII isoforms αB and δB (nucleus), α (dendritic spines), β (F-actin), and the non-kinase variant αKAP (intracellular membranes) (for a review, see Bayer and Schulman, 2001). Differential decoding of Ca2+ oscillation frequencies is based on a Ca2+/CaM-stimulated inter-subunit autophosphorylation within holoenzymes (at T286 for α and at T287 for the other isoforms). Such a regulated autophosphorylation leads to Ca2+/CaM-independent (autonomous) activity of the kinase that outlasts the initial stimulation (for a review, see Schulman and Braun, 1999; Soderling et al., 2001). This autophosphorylation requires simultaneous binding of at least two Ca2+/CaM molecules per holoenzyme: one for activation of a kinase subunit and another to expose T286 (α) or T287 (β, γ and δ) for phosphorylation on a neighboring subunit (Hanson et al., 1994; Rich and Schulman, 1998). This dual Ca2+/CaM requirement, both kinase and substrate directed, has led to the proposal that generation of autonomous CaMKII activity is sensitive to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations (Hanson et al., 1994; see also Dosemeci and Albers, 1996). To test this model, we recently developed an approach that allows the exposure of isolated CaMKII to brief (e.g. 200 ms) Ca2+ spikes under precisely controlled kinetics and frequencies (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). This highly sensitive approach indeed revealed that autonomous CaMKII activity increases exponentially with the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998).

While the immense diversity of possible CaMKII holoenzyme species, generated by the dodecameric co-assembly of four gene products with >20 splice variants, has been shown to differentially control targeting of the kinase (for a review, see Bayer and Schulman, 2001), we asked here whether this diversity can also provide for differential sensitivities to Ca2+ oscillations. We compared, under steady and pulsatile Ca2+ stimulation, the activation and generation of autonomy for three splice variants of the β-CaMKII isoform that contain identical kinase domains. We show here that these three splice variants, β, βe′ and βM, share very similar catalytic features under steady stimulation, yet can differentially decode Ca2+ oscillation frequencies. Furthermore, we describe differential expression of the splice variants, even among individual hippocampal neurons, suggesting that alternative splicing of CaMKII provides cells with a mechanism to regulate their frequency sensitivity to Ca2+-based signals. Our study demonstrates that very subtle functional differences between kinase subtypes can lead to significant changes in output signals of the distinct isoforms when exposed to specific oscillatory input signals.

Results

βM-CaMKII is a splice variant of the β isoform

βM-CaMKII is closely related to the β isoform, but contains a 12 kDa insert at the C-terminus of the variable region (Bayer et al., 1998). Further sequence analysis of the murine β-CaMKII gene (Karls et al., 1992) revealed that βM is, indeed, a splice variant of the β isoform (Figure 1). These sequence data have been submitted to the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession Nos AF416336 and AF416337. The βM-specific insert consists of three proline-rich repeats, which are homologous to each other (Bayer et al., 1998, 1999) (Figure 1A and B). Each repeat is encoded by a separate exon, and the conserved intron borders contain the consensus sequences for splice sites (Figure 1C; for a review, see Smith and Valcarcel, 2000). Three previously described β-CaMKII splice variants (β′, βe and βe′) lack one or two exons in the variable region 5′ proximal to the βM-specific insert (Karls et al., 1992; Brocke et al., 1995) (Figure 1A and B); β3-CaMKII resembles the βe′ variant, but additionally contains the two βM repeats b and c (Urquidi and Ashcroft, 1995). Therefore, all known β-CaMKII variants differ only in their variable region, which is thought to comprise the ‘linker’ between the N-terminal kinase domain and the C-terminal association domain (Figure 1A).

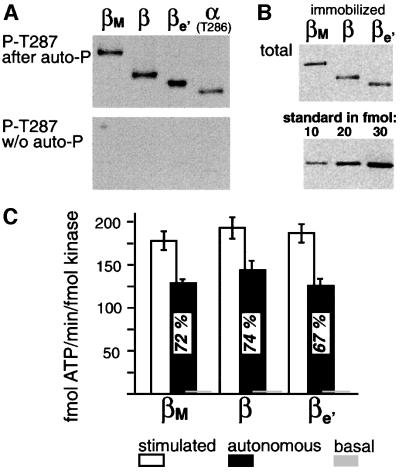

Specific activity and maximal autonomy of β-, βM- and βe′-CaMKII are similar

To compare the biochemical properties of β-CaMKII splice variants under steady-state and pulsatile Ca2+ stimulation, we tagged each of them with a hemag glutinin A epitope (HA) at the C-terminus, which allows their immobilization onto anti-HA antibody-coated PVC microtiter plates or tubing. Such tagging and immobilization do not interfere with normal activation by Ca2+/CaM, autophosphorylation and generation of autonomous activity, or oligomerization into holoenzymes (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). First, we assessed the autophosphorylation status of the kinase variants overexpressed in COS-7 cells (Figure 2A). Prolonged Ca2+/CaM stimulation induced essentially the same T287 autophosphorylation for all β variants (and similar to the autophosphorylation of the homologous T286 for the α isoform); no phospho-T287 (or T286) was detected without such stimulation (Figure 2A). We then adsorbed the tagged kinase variants onto microtiter plates, determined the amount of bound kinase by quantitative immunoblotting (Figure 2B), and tested the kinase activity of the splice variants towards the exogenous peptide substrate autocamtide-3 (AC-3) (Figure 2C). We found that the Ca2+/CaM-stimulated specific activities of the three β-CaMKII splice variants (β, βM and βe′) are very similar (Figure 2B and C). Furthermore, the variants are equally capable of becoming highly Ca2+ independent (autonomous) after T287 autophosphorylation induced by prolonged Ca2+/CaM stimulation (1.5 min) (Figure 2C). The basal activity without Ca2+/CaM stimulation or autophosphorylation was <1.5% for all variants (βM = 0.71 ± 0.42%, β = 0.99 ± 0.40% and βe′ = 0.80 ± 0.51%). In initial experiments, we used extracts of COS-7 cells overexpressing untagged βM-, β- or βe′-CaMKII and observed essentially the same results, with similar specific activities of the splice variants also when measured in solution (data not shown). These results suggest that alternative splicing within the linker region has little effect on the steady-state activity of the kinase.

Fig. 2. (A) Autophosphorylation at the autonomy site T287 can be induced by Ca2+/CaM for all three β variants, as detected by immunoblotting using a phospho-T287-specific antibody (top). Similar phos phorylation was observed for α (at the homologous T286). No T287 phosphorylation was detected before stimulation with Ca2+/CaM (bottom). (B) Immunodetection of total immobilized β-CaMKII splice variants with the same specific kinase activity (3000 fmol of ATP/min), using the CB-β1 antibody. Below: purified β-CaMKII as standard. (C) Specific activities of β splice variants (means ± SEM) in a peptide substrate phosphorylation assay. Stimulated activity was induced by 300 nM CaM; autonomous activity was measured in the absence of Ca2+/CaM, but after autophosphorylation. Autonomy is indicated relative to the stimulated activity. Basal activity (not stimulated and without autophosphorylation) for all variants was <1.5%, as indicated. The experiments were performed with HA-tagged kinase isoforms immobilized on anti-HA antibody-coated microtiter plates.

β-CaMKII splice variants with differential response to Ca2+ oscillations

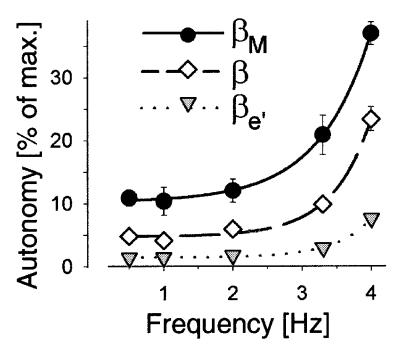

We reasoned that differences in the variable linker region could influence the relative positioning of the kinase domains within the holoenzyme structure (Figure 1A), which could lead to subtle differences in generation of autonomous activity among the splice variants. Auto phosphorylation at the autonomy site (T287 in β-CaMKII) requires interaction between two activated kinase subunits within a holoenzyme (Hanson et al., 1994; Rich and Schulman, 1998). Thus, under very brief stimulation or non-equilibrium conditions, such as during Ca2+ oscillations, any subtle difference in kinase-domain interaction may have more detectable functional effects. To test for this possibility, we exposed immobilized β-CaMKII splice variants to Ca2+ oscillations inside anti-HA antibody-coated PVC tubing connected to a computer-controlled pulse-flow device that allows rapid exchange of solutions by use of two pressurized chambers. Immobilized kinase variants were exposed to brief (200 ms) activating pulses (Ca2+ spikes) alternating with de-activating pulses of various duration (spike intervals, containing 1 mM EGTA). Each stimulation protocol exposed the kinase to 30 Ca2+ spikes delivered at various frequencies by adjusting the duration of spike intervals. Following each protocol, the evoked autonomous kinase activity was measured inside the tubing by AC-3 phosphorylation in the absence of Ca2+ (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). Figure 3 shows that the autonomous activity of β-CaMKII increases exponentially with the frequency of Ca2+ spikes. Each β splice variant shows such frequency sensitivity. However, they differ significantly from each other in the degree of autonomy evoked by any given stimulation frequency. While βM is consistently more autonomous than β, autonomy of βe′ is always lower than that of β. Furthermore, βM has the broadest frequency response with the lowest factor of exponential increase, followed by β and βe′. These results demonstrate that alternative splicing modulates the response of β-CaMKII to the frequencies of Ca2+ oscillations, but not to sustained maximal Ca2+ stimulation.

Fig. 3. Differential response of β-CaMKII splice variants to Ca2+ oscillations. Different frequencies of Ca2+ oscillations evoke different levels of autonomous activity for β, βM and βe′. Curves were fitted to the single-exponential function y = aebx + c. The factor of exponential increase, b, for βe′ is 10% greater than that for β, and 50% greater than that for βM. All data points are means ± SEM.

Two biochemical parameters that can influence frequency decoding by CaMKII

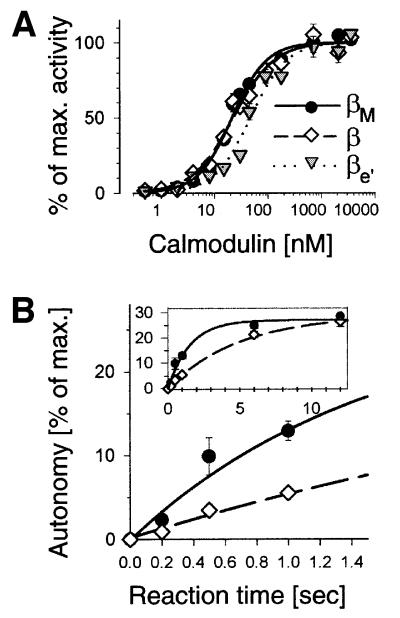

How can this alternative splicing of β-CaMKII lead to isoform-specific frequency responses without affecting the steady-state catalytic properties? Although β- and βe′-CaMKII have an identical CaM binding site within their regulatory regions, we found that βe′ has a higher activation constant for CaM than β (Figure 4A; Ka for CaM of β = 22.4 ± 2.5 nM, and of βe′ = 47.5 ± 6.9 nM). A higher activation constant (or lower affinity) for CaM should, in fact, result in reduced activation by submaximal stimuli, such as the brief Ca2+ spikes in the above stimulation protocol. For βe′, the CaM affinity might be reduced by the shorter length of the variable ‘linker’ between the kinase/regulatory domain and the association domain. In contrast, the Kas for CaM of β and βM are nearly identical (22.4 ± 2.5 and 21.4 ± 1.7 nM, respectively) and their CaM concentration–response curves are almost undistinguishable (Figure 4A). As shown above, the β and βM isoforms also have essentially the same specific activities towards a peptide substrate (Figure 2), as well as apparent rates of autophosphorylation when measured after 12 s or longer (Figures 2C and 4B).

Fig. 4. Calmodulin activation constant and initial rate of autophosphorylation as parameters that can modulate the response of CaMKII to Ca2+ oscillations. (A) Calmodulin concentration–response curves reveal a higher Ka for βe′ than for β and βM (47.5 ± 6.9, 22.4 ± 2.5 and 21.4 ± 1.7 nM, respectively). (B) The initial rate of autophosphorylation is higher for βM than for β, as measured by the resulting autonomous activity. All data points are means ± SEM.

How, then, can these two splice variants, β and βM, respond differently to Ca2+ oscillations? One possibility could be a difference in their initial rate of autophosphorylation, even though the phosphorylation rates are the same for an exogenous peptide substrate (Figure 2). Thus, we monitored T287 autophosphorylation evoked by a single brief Ca2+ stimulus (0.5 mM CaCl2, 300 nM CaM), using the controlled pulse-flow device for the stimulation and autonomous kinase activity as readout. Autonomous activity is dependent on T287 autophosphorylation, and autonomy actually provides a more sensitive and more accurate quantitative readout for T287 autophosphorylation than phosphate incorporation (Bradshaw et al., 2002). Indeed, the initial rate of autophosphorylation, as measured by generation of autonomy within 0.2–1 s of stimulation, is significantly higher for βM than for β-CaMKII (Figure 4B). Our results indicate that the probability of inter-subunit autophosphorylation during a brief Ca2+ spike is higher for βM than for β (Figure 4B). This should indeed lead to a higher degree of autonomy for βM during Ca2+ oscillations (Figure 3), even if the activation kinetics by Ca2+/CaM are the same for β and βM. We speculate that the longer linker in βM increases the spatial mobility of kinase domains, thereby facilitating interactions necessary for autophosphorylation. Our results show that βM- and βe′-CaMKII differ from the β isoform in their initial rate of autophosphorylation and CaM affinity, respectively, two parameters that can significantly modulate the response to Ca2+ oscillations.

β-CaMKII variants are differentially expressed in brain

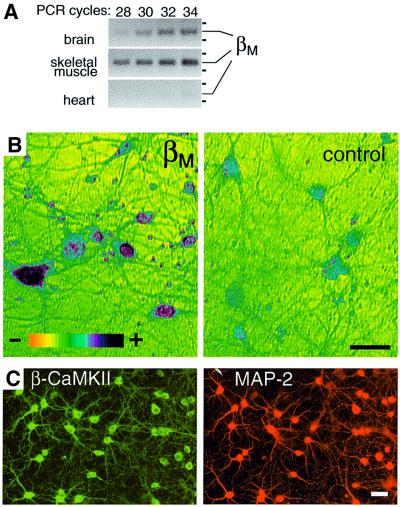

Alternative splicing may modulate the sensitivity of CaMKII-mediated signaling pathways to the various forms of Ca2+ transients and oscillations in cell type- and development-specific manners. Indeed, βe and βe′ are the predominant CaMKII isoforms expressed in the postnatally developing brain (Brocke et al., 1995), largely replaced in adult rats by β-CaMKII. Such a change likely increases the sensitivity of the neuronal CaMKII to low-frequency stimulation. Interestingly, the β-CaMKII splice variants are also differentially expressed among individual adult hippocampal–pyramidal neurons, as revealed by single-cell RT–PCR (Brocke et al., 1999). The βM variant was not known at the time of the latter study, but a band corresponding in length to βM was detected in the PCR reactions from 2 of 24 neurons (L.Chiang and H.Schulman, unpublished data). By RT–PCR with βM-specific primers, we found significant expression of βM-CaMKII in brain, although its expression level is likely to be 10- to 100-fold lower than in skeletal muscle (Figure 5A), the tissue with highest expression of βM (Bayer et al., 1998, 1999). In comparison, βM expression in heart was only barely detectable, even with the highly sensitive RT–PCR. To examine whether brain βM-CaMKII is expressed in neurons or other cell types, we performed in situ hybridization of dissociated rat hippocampal cultures, using a digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe derived from the βM-specific insert essentially as described previously (Bayer et al., 1999). βM-CaMKII transcripts were indeed detected in neurons, with significant expression restricted to a subset of them (Figure 5B). In contrast, essentially every cultured hippocampal neuron contains at least one β variant at the protein level, as shown by immunocytochemistry with a β-specific antibody that does not discriminate between the splice variants (Figure 5C). Neurons were distinguished from glia by co-staining for the neuronal marker MAP-2 (Figure 5C); the almost complete overlap of the β stain with the MAP-2 stain indicates that significant expression of β-CaMKII splice variants is restricted to neurons.

Fig. 5. βM-CaMKII is expressed in neurons. (A) RT–PCR with βM- specific primers at increasing cycle numbers from oligo-dT-primed cDNA prepared from mRNA from different rat tissues. The positions of 300 and 400 bp marker bands are indicated. (B) In situ hybridization of cultured hippocampal neurons with a digoxigenin-labeled βM- specific RNA probe (left) (nucleotides 133–354 in Bayer et al., 1999) and the corresponding sense probe control (right). Color coding represents different expression levels, as indicated. (C) Immuno cytochemistry for β-CaMKII and MAP-2 in the cultured neurons. Nearly all neurons (MAP-2-positive cells) are positively stained with an antibody specific for all splice variants of β-CaMKII. Scale bars = 40 µm.

Discussion

Transient rises in intracellular Ca2+ concentration contain information not only in their amplitude and duration, but also in their frequency; however, CaMKII is presently the only identified molecular decoder for such oscillation frequencies (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). We have demonstrated here that alternative splicing provides an array of β-CaMKII variants (Figure 1) with different sensitivities to Ca2+ oscillations despite their catalytic similarities observed under steady stimulation (Figures 2 and 3). Two biochemical parameters that can account for the differential frequency decoding by βM-, β- or βe′-CaMKII were identified, e.g. the initial rate of autophosphorylation (for βM) and CaM activation constant (for βe′) (Figure 4). Remarkably, the β-CaMKII variants are differentially expressed in different tissues, during development, and even among individual adult hippocampal neurons (Figure 5; Brocke et al., 1995, 1999; Bayer et al., 1998), suggesting that nature indeed utilizes alternative splicing of CaMKII as a mechanism to regulate cellular sensitivity to Ca2+ oscillation frequencies.

The β-CaMKII splice variants contain identical kinase domains, including the regulatory region with the binding site for Ca2+/CaM. Thus, our findings that βM-, β- and βe′-CaMKII have very similar specific activities and degrees of maximal autonomy were not too surprising. We argued that the most sensitive readout for any possible subtle difference would be the frequency-dependent response of the kinase to Ca2+ oscillations, as small effects during short pulses with submaximal, non-equilibrium stimulation would be enhanced by the multiple repetitions of an oscillation. To expose CaMKII to such short pulses (200 ms) and oscillations (0.5–4 Hz), we utilized a computer-controlled pulse-flow device developed recently (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). Indeed, significant differences of βM-, β- and βe′-CaMKII were revealed in their generation of Ca2+-independent (autonomous) activity during Ca2+ oscillations at different frequencies.

Generation of autonomous CaMKII activity depends on an inter-subunit autophosphorylation within a multimeric holoenzyme. Structurally, β-CaMKII splice variants differ only in a variable region, which is thought to comprise the linker connecting the foot-like kinase domains with the central hub formed by the association domains (Kolodziej et al., 2000; Figure 1A). We argued that the length of this linker could influence the kinetics of autophosphorylation by modulating the accessibility of the kinase subunits to each other or of CaM to an individual kinase subunit. Although alternative splicing does not directly affect the CaM binding site, the variable region is immediately adjacent. Indeed, compared with β- and βM-CaMKII, the CaM activation constant for the smallest variant, βe′-CaMKII, is higher, corresponding to a lower affinity. Similar effects of alternative splicing on CaMKII activation by CaM have been reported previously for CaMKII isoforms from Drosophila and mammals (GuptaRoy et al., 1996; Brocke et al., 1999). Compared with any β variant, α-CaMKII has both a shorter variable linker and a lower CaM affinity (Brocke et al., 1999), further suggesting a causal link. In contrast, the CaM activation curves of β and βM are indistinguishable, indicating that additional elongation of the β variable region, even by the 12 kDa βM insert, does not further increase CaM affinity. However, compared with β-CaMKII, the longer βM variant shows a marked increase in the initial rate of autophosphorylation, as measured by autonomous activity generated during brief (0.2–1 s) stimulation. The βM insert may achieve this accelerated autophosphorylation within a holoenzyme by facilitating the interaction between two kinase subunits, or by increasing the number of kinase subunits that can access each other. Alternatively, the autonomy site at T287 might be a better substrate sequence for βM-CaMKII than for β-CaMKII. In fact, alternative splicing was recently found to modulate the substrate preference of Drosophila CaMKII (GuptaRoy et al., 2000). However, the peptide substrate AC-3 that we used to determine the specific activities of the β splice variants is actually derived from the region surrounding T287, and the activity of βM-CaMKII is essentially the same as for the β isoform; if anything, the βM activity appeared slightly lower. Thus, the βM insert has most likely a steric effect that allows the kinase subunits to access each other more readily. In fact, the structure of CaMKII holoenzymes (Kolodziej et al., 2000) does suggest a significant steric restriction for the interaction between α-CaMKII subunits, which contain a shorter variable region.

Both CaM affinity and the initial rate of autophosphorylation should indeed affect the response to Ca2+ oscillations even in our most simple model for frequency detection by CaMKII. During Ca2+ spikes, CaM binds to the kinase, and dissociates during the spike intervals. When the spike intervals are long (low frequency), each Ca2+ pulse elicits the same kinase response. However, when the spike intervals are short (high frequencies) and within the range of the CaM dissociation constant (Meyer et al., 1992), CaM accumulates on the kinase with each pulse. A lower CaM affinity would reduce the activation of the kinase at low frequencies, shift the exponential rise to higher frequencies, and make this exponential function steeper, as was observed for βe′-CaMKII. A faster rate of autophosphorylation would increase the generation of autonomous activity with each pulse, even at low frequencies, as seen for βM-CaMKII. As autophosphorylation also increases the affinity of CaMKII to CaM (Meyer et al., 1992), a higher degree of autophosphorylation per Ca2+ spike would also shift the exponential rise to lower frequencies and make this rise appear less steep. As a consequence, significant autonomous activity of βM-CaMKII is generated even by low-frequency Ca2+ oscillations, whereas βe′-CaMKII requires high-frequency stimulation for appreciable autonomy.

It should be noted that the frequency response of CaMKII is considerably shaped by the pulse duration and amplitude: pulses of short duration and/or low amplitude activate autophosphorylation at a higher threshold frequency, whereas pulses of longer duration and/or higher amplitude can be sensed by the kinase over a broader range of frequencies (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). These effects are directly related to the probability of CaM binding during the pulses. The frequency range of Ca2+ oscillation that CaMKII can sense is thus expected to vary considerably depending on the properties of the Ca2+ spikes and the local factors that bind, chelate or release Ca2+ and CaM. The length and frequencies of Ca2+ spikes in cells vary tremendously, from a few milliseconds to several seconds and from 10–3 to at least 10 Hz, depending on the stimuli or the subcellular compartments (Koester and Sakmann, 2000; for a review, see Berridge et al., 2000; Bootman et al., 2001). Thus, alternative splicing of CaMKII should differentially impact the kinase output signal, depending on the cellular localization and the input stimulus.

What are the functional implications of the differential Ca2+ oscillation response detected for the different CaMKII isoforms? In skeletal muscle, βM-CaMKII is one of the most prominent CaMKII isoforms and the only β variant expressed (Bayer et al., 1998). There, βM is targeted by a CaMKII-related anchoring protein, αKAP, to the membrane of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Bayer et al., 1998), where CaMKII controls Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in a negative feedback loop by phosphorylating the ryanodine receptor (the Ca2+ release channel) (Witcher et al., 1991; Wang and Best, 1992; Hain et al., 1995), phospholamban (a regulator of the Ca2+ pump protein) (Wegener et al., 1989) and the Ca2+ pump protein itself (Xu et al., 1993; Hawkins et al., 1994). Thus, CaMKII can control Ca2+ oscillations, and its own sensitivity to such oscillations, modulated by kinase isoform and splice variant expression, would influence this feedback regulation. Expression of both β- and βe′-CaMKII is restricted to the central nervous system. However, α- and β-CaMKII are by far the most abundant isoforms in the mature brain. In contrast, βe- and βe′-CaMKII are the predominant β variants during early postnatal development, a time when there is virtually no α- or β-CaMKII present. Like βe′-CaMKII, the βe variant has reduced CaM affinity (Brocke et al., 1999). Thus, neonatal neurons mostly express CaMKII isoforms that can, in contrast to α-CaMKII, associate with the actin cytoskeleton (Shen et al., 1998), but have a high frequency threshold, more similar to the α isoform. A requirement for distinct frequencies of spontaneous Ca2+ spikes and waves in neural development has been demonstrated (Gu and Spitzer, 1995), and Ca2+ and CaMKII have actin-based morphological effects on dendritic arbors and spines (Wu and Cline, 1998; Fischer et al., 2000), probably with distinct functions in differentiating versus mature neurons. High frequencies of neuronal stimulation can trigger long-term potentiation of synaptic strength, whereas low-frequency stimulation leads to long-term depression. The autophosphorylation state of CaMKII is thought to be involved in setting the frequency threshold for the induction of long-term potentiation (for a review, see Deisseroth et al., 1995). Thus, this form of metaplasticity would be modulated by differential expression of CaMKII isoforms with distinct Ca2+ oscillation sensitivities for autophosphorylation. Indeed, such metaplasticity is known to change during development (Molloy and Kennedy, 1991; Deisseroth et al., 1995; Mayford et al., 1995).

Remarkably, βM-, β- and βe′-CaMKII are differentially expressed even among individual mature hippocampal neurons, as shown here for βM and previously for the other β variants (Brocke et al., 1999). Thus, regulated alternative splicing may tune the sensitivity to Ca2+ oscillations not only during development and for different tissues, but also for individual cells of the same type. Thereby, differential expression of CaMKII variants can provide a novel level of neuronal plasticity, and it will be interesting to elucidate the mechanisms and cellular stimuli that regulate the alternative splice events. The ubiquitous γ and δ isoforms of CaMKII show a high degree of structural homology to α- and β-CaMKII and are subject to even more extensive alternative splicing. Thus, alternative splicing and co-assembly into heteromeric holoenzymes with mixed properties (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998; Brocke et al., 1999) can give rise to finely tuned arrays of molecular decoders of Ca2+ oscillations in a large variety of different cell types.

Materials and methods

Molecular cloning and sequencing

Genomic clones of the murine β-CaMKII locus have been initially derived from a λ-library screen (Karls et al., 1992). Subclones in pBKS mapping the region 5′ of the first exon coding for the association domain and 3′ of the last exon coding for the conventional variable region (exons V and IV in Karls et al., 1992) were sequenced using the ABI system. The following sequencing primers were derived from both ends of each βM-CaMKII-specific repeat, allowing generation of sequence information in both directions, with coding sequences known from cDNA analysis preceding the unknown intron border sequences: bM-1.3, CAG GGAGAGTCGGAGAT; bM-2.3, TAGGAGACCCGGAGACAA; bM-3.3, CTAATGGGAACTGGAGAT; bM-4.5, TCCTCAACTCAGTGA GGC; bM-5.5, TCCTGAACTCAGTGAGAA; bM-6.5, TGAGCT TGGTGAGGA.

Mammalian expression vectors in SRα for β-, βe′- and βM-CaMKII have been described previously (Brocke et al., 1995; Bayer et al., 1998). A C-terminal HA-epitope tag was introduced in the βe′ and βM sequences essentially as carried out previously for the β isoform (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998).

Protein expression, immunodetection and activity assay

COS-7 cells were transfected with expression vectors by the CaPO4 method and harvested 68–76 h after transfection, as described previously (Srinivasan et al., 1994; Bayer et al., 1998). CaMKII was detected by western blotting and subsequent immunostaining with a β-CaMKII-specific antibody (CB-β1; Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or a phospho-T286/T287-CaMKII-specific antibody (Upstate Biotech, Charlottesville, VA) using the Western Lightning detection system (NEN/PerkinElmer, Boston, MA), essentially as described (Srinivasan et al., 1994; Bayer et al., 1998). For detection after immobilization (see below), the kinase was re-solubilized for 10 min in SDS loading buffer at 95°C. Stimulated kinase activity was tested by phosphorylation of the peptide substrate AC-3 during 1 min reactions at 30°C [50 mM PIPES pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% BSA, 25 µM AC-3, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 300 nM CaM or as indicated, and 250 µM [γ-32P]ATP (1 Ci/mmol)]. For assessing Ca2+-independent (autonomous) kinase activity, the reaction mix contained 1 mM EGTA and no Ca2+ or CaM. Reactions were stopped by precipitation with 10% TCA on ice, and the supernatants containing the peptide substrate were spotted onto Whatman P81 paper squares. ATP was removed by washing the filters for 45 min, first in 0.5% phosphoric acid and then in water, and 32P incorporation of the bound peptide was measured in a scintillation counter.

Immobilized kinase assay, autophosphorylation and oscillatory stimulation

HA-tagged CaMKII was immobilized on PVC microtiter plates or tubing coated with anti-HA antibody (BabCO/Covance, Princeton, NY) (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). Stimulated and autonomous activity of the immobilized kinase were assessed as described above, however without the TCA precipitation step. Maximal autonomy was generated by 1.5 min autophosphorylation on ice in activating solution (non-radioactive assay buffer with 30 nM CaM but without peptide substrate). For measuring autonomy after brief (0.2–12 s) Ca2+ stimulation, tubing with immobilized CaMKII was connected to a custom-made device with computer-controlled valves allowing alternate flow from two pressurized chambers containing either activating solution or de-activating solution (without CaCl2, CaM or ATP, but with 1 mM EGTA) at 30°C (De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). Autophosphorylation was induced by activating solution, and stopped after various times by a pulse of de-activating solution. To assess the response of CaMKII to Ca2+ oscillations, 30 brief activating pulses (0.2 s) were alternated with de-activating pulses. The oscillation frequency was controlled by the duration of the de-activating pulses.

RT–PCR, in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry

RT–PCR was performed essentially as described previously (Karls et al., 1992; Bayer et al., 1996). RNAs from different tissues (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) were used as templates for oligo-dT-primed cDNA synthesis with Superscript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The PCR primers are described above [bM-6.5 and bM-1.3; nucleotides 22–36 and complement of nucleotides 348–354 in Bayer et al. (1999)].

In situ hybridization of hippocampal neurons cultured for 3 weeks at high density (Bayer et al., 2001) with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes was performed as described previously (Bayer et al., 1999). The antisense probe corresponds to nucleotides 133–354 of the βM-specific insert (Bayer et al., 1999), and a sense-strand probe was used as control. For immunocytochemistry with antibodies against β-CaMKII (monoclonal CB-β1; Gibco; 1:200 dilution) and MAP-2 (polyclonal; Chemicon, Temecula, CA; 1:300 dilution), neurons were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 4% sucrose) for 10 min, permeabilized and pre-blocked for 60 min in PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, 5% normal goat serum. Primary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in blocking solution. Secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse–Alexa-488 and goat anti-rabbit–Alexa-594; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; 1:200 dilution) were incubated for 45 min at room temperature. Following multiple washes, coverslips were mounted on glass slides with Immuno-Floure mounting media (ICN, Costa Mesa, CA). Fluorescent images were acquired with a Coolsnap-HQ CCD camera (Roper Instruments, Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ), through a 10× achroplan water immersion objective (0.3 numerical aperture) on a Zeiss Axioskop FS-2 microscope.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Klaus Harbers (Heinrich-Pette-Institute), Lillian Chiang (Purdue Pharma), Mollie Meffert (Caltech), Dennis Baylor, Amir Naini and Andy Hudmon (Stanford) for helpful discussions, and K.H. additionally for providing λ-clones of the genomic β-CaMKII locus and L.C. for sharing unpublished information. The excellent technical assistance of Nora Sotelo-Kury (Stanford) and Francine Nault (Laval) is gratefully acknowledged. The research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (K.U.B.), the Natural Science and Engineering Council of Canada, a Career Award of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (P.D.K.) and NIH (H.S.).

References

- Bayer K.U. and Schulman,H. (2001) Regulation of signal transduction by protein targeting: the case for CaMKII. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 289, 917–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer K.U., Löhler,J. and Harbers,K. (1996) An alternative, nonkinase product of the brain-specifically expressed Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II α isoform gene in skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer K.U., Harbers,K. and Schulman,H. (1998) αKAP is an anchoring protein for a novel CaM kinase II isoform in skeletal muscle. EMBO J., 17, 5598–5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer K.U., Löhler,J., Schulman,H. and Harbers,K. (1999) Develop mental expression of the CaM kinase II isoforms: ubiquitous γ- and δ-CaM kinase II are the early isoforms and most abundant in the developing nervous system. Mol. Brain Res., 70, 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer K.U., De Koninck,P., Leonard,A.S., Hell,J.W. and Schulman,H. (2001) Interaction with the NMDA receptor locks CaMKII in an active conformation. Nature, 411, 801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J., Lipp,P. and Bootman,M.D. (2000) The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol., 1, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman M.D., Lipp,P. and Berridge,M.J. (2001) The organisation and function of local Ca2+ signals. J. Cell Sci., 114, 2213–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J.M., Hudmon,A. and Schulman,H. (2002) Chemical quench– flow kinetic studies indicate an intra-holoenzyme autophosphorylation mechanism for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 20991–20998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocke L., Srinivasan,M. and Schulman,H. (1995) Developmental and regional expression of multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase isoforms in rat brain. J. Neurosci., 15, 6797–6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocke L., Chiang,L.W., Wagner,P.D. and Schulman,H. (1999) Functional implications of the subunit composition of neuronal CaM kinase II. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 22713–22722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck P. and Schulman,H. (1998) Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science, 279, 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K., Bito,H., Schulman,H. and Tsien,R.W. (1995) A molecular mechanism for metaplasticity. Curr. Biol., 5, 1334–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosemeci A. and Albers,R.W. (1996) A mechanism for synaptic frequency detection through autophosphorylation of CaM kinase II. Biophys. J., 70, 2493–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosemeci A., Tao-Cheng,J.H., Vinade,L., Winters,C.A., Pozzo-Miller,L. and Reese,T.S. (2001) Glutamate-induced transient modification of the postsynaptic density. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 10428–10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M., Kaech,S., Wagner,U., Brinkhaus,H. and Matus,A. (2000) Glutamate receptors regulate actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Nat. Neurosci., 3, 887–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X. and Spitzer,N.C. (1995) Distinct aspects of neuronal differentiation encoded by frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Nature, 375, 784–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GuptaRoy B., Beckingham,K. and Griffith,L.C. (1996) Functional diversity of alternatively spliced isoforms of Drosophila Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. A role for the variable domain in activation. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 19846–19851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GuptaRoy B., Marwaha,N., Pla,M., Wang,Z., Nelson,H.B., Beckingham, K. and Griffith,L.C. (2000) Alternative splicing of Drosophila calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates substrate specificity and activation. Mol. Brain Res., 80, 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hain J., Onoue,H., Mayrleitner,M., Fleischer,S. and Schindler,H. (1995) Phosphorylation modulates the function of the calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum from cardiac muscle. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 2074–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson P.I., Meyer,T., Stryer,L. and Schulman,H. (1994) Dual role of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of multifunctional CaM kinase may underlie decoding of calcium signals. Neuron, 12, 943–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins C., Xu,A. and Narayanan,N. (1994) Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump in cardiac and slow twitch skeletal muscle but not fast twitch skeletal muscle undergoes phosphorylation by endogenous and exogenous Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Character ization of optimal conditions for calcium pump phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 31198–32206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon A. and Schulman,H. (2002) Neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II: the role of structure and autoregulation in cellular function. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 71, 473–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaseki T., Ikeuchi,Y., Sugiura,H. and Yamauchi,T. (1991) Structural features of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II revealed by electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol., 115, 1049–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karls U., Muller,U., Gilbert,D.J., Copeland,N.G., Jenkins,N.A. and Harbers,K. (1992) Structure, expression, and chromosome location of the gene for the β subunit of brain-specific Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II identified by transgene integration in an embryonic lethal mouse mutant. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 3644–3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M.B., Bennett,M.K. and Erondu,N.E. (1983) Biochemical and immunochemical evidence that the ‘major postsynaptic density protein’ is a subunit of a calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 7357–7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester H.J. and Sakmann,B. (2000) Calcium dynamics associated with action potentials in single nerve terminals of pyramidal cells in layer 2/3 of the young rat neocortex. J. Physiol., 529, 625–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej S.J., Hudmon,A., Waxham,M.N. and Stoops,J.K. (2000) Three-dimensional reconstructions of calcium/calmodulin-dependent (CaM) kinase II α and truncated CaM kinase II α reveal a unique organization for its structural core and functional domains. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 14354–14359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka R.C. and Nicoll,R.A. (1999) Long-term potentiation—a decade of progress? Science, 285, 1870–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayford M., Wang,J., Kandel,E.R. and O’Dell,T.J. (1995) CaMKII regulates the frequency response function of hippocampal synapses for the production of both LTD and LTP. Cell, 81, 891–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T., Hanson,P.I., Stryer,L. and Schulman,H. (1992) Calmodulin trapping by calcium–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Science, 256, 1199–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy S.S. and Kennedy,M.B. (1991) Autophosphorylation of type II Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in cultures of postnatal rat hippocampal slices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 4756–4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta Y., Nishida,E. and Sakai,H. (1986) Type II Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase binds to actin filaments in a calmodulin-sensitive manner. FEBS Lett., 208, 423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich R.C. and Schulman,H. (1998) Substrate-directed function of calmodulin in autophosphorylation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 28424–28429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman H. and Braun,A. (1999) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. In Carafoli,E. and Klee,C. (eds), Calcium as Cellular Regulator. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 311–343.

- Shen K. and Meyer,T. (1999) Dynamic control of CaMKII translocation and localization in hippocampal neurons by NMDA receptor stimulation. Science, 284, 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K., Teruel,M.N., Subramanian,K. and Meyer,T. (1998) CaMKIIβ functions as an F-actin targeting module that localizes CaMKIIα/β heterooligomers to dendritic spines. Neuron, 21, 593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.W. and Valcarcel,J. (2000) Alternative pre-mRNA splicing: the logic of combinatorial control. Trends Biochem. Sci., 25, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderling T.R., Chang,B. and Brickey,D. (2001) Cellular signaling through multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 3719–3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M., Edman,C.F. and Schulman,H. (1994) Alternative splicing introduces a nuclear localization signal that targets multifunctional CaM kinase to the nucleus. J. Cell Biol., 126, 839–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquidi V. and Ashcroft,S.J.H. (1995) A novel pancreatic β-cell isoform of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (b3 isoform) contains a proline-rich tandem repeat in the association domain. FEBS Lett., 358, 23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. and Best,P.M. (1992) Inactivation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium channel by protein kinase. Nature, 359, 739–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener A.D., Simmerman,H.K.B., Lindemann,J.P. and Jones,L.R. (1989) Phospholamban phosphorylation in intact ventricles. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 11468–11474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witcher D.R., Kovacs,R.J., Schulman,H., Cefali,D.C. and Jones,L.R. (1991) Unique phosphorylation site on the cardiac ryanodine receptor regulates calcium channel activity. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 11144–11152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.Y. and Cline,H.T. (1998) Stabilization of dendritic arbor structure in vivo by CaMKII. Science, 279, 222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu A., Hawkins,C. and Narayanan,N. (1993) Phosphorylation and activation of the Ca2+-pumping ATPase of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 8394–8397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]