Abstract

Transcription factor ATF2 regulates gene expression in response to environmental changes. Upon exposure to cellular stresses, the mitogen-activated proteinkinase (MAPK) cascades including SAPK/JNK and p38 can enhance ATF2’s transactivating function through phosphorylation of Thr69 and Thr71. How ever, the mechanism of ATF2 activation by growth factors that are poor activators of JNK and p38 is still elusive. Here, we show that in fibroblasts, insulin, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and serum activate ATF2 via a so far unknown two-step mechanism involving two distinct Ras effector pathways: the Raf–MEK–ERK pathway induces phosphorylation of ATF2 Thr71, whereas subsequent ATF2 Thr69 phosphorylation requires the Ral–RalGDS–Src–p38 pathway. Cooperation between ERK and p38 was found to be essential for ATF2 activation by these mitogens; the activity of p38 and JNK/SAPK in growth factor-stimulated fibroblasts is insufficient to phosphorylate ATF2 Thr71 or Thr69 + 71 significantly by themselves, while ERK cannot dual phosphorylate ATF2 Thr69 + 71 efficiently. These results reveal a so far unknown mechanism by which distinct MAPK pathways and Ras effector pathways cooperate to activate a transcription factor.

Keywords: ATF2/ERK/mitogens/p38/Ras

Introduction

ATF2 is a ubiquitously expressed member of the basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor family that can regulate gene expression in response to changes in the cellular environment. ATF2 plays an important role in placenta formation and skeletal and central nervous system development (Reimold et al., 1996; Maekawa et al., 1999) and is involved in oncogenic transformation and in adaptive responses of the cell to viral infections and (geno)toxic stresses (Liu and Green, 1990; Reimold et al., 1996; Ronai et al., 1998; Maekawa et al., 1999; Falvo et al., 2000; van Dam and Castellazzi, 2001). ATF2 binds its target promoter/enhancers as a homodimer or as a heterodimer with a restricted group of other bZip proteins, the most well known of which is the c-jun oncogene product.

Heterodimerization of ATF2 appears to be crucial for at least some of its functions; for instance, the oncogenic activity of ATF2 in chicken cells critically depends on its ability to dimerize with cJun (Huguier et al., 1998). ATF2 is also assumed to play a role in cJun-dependent cell cycle progression, cell survival and apoptosis, in addition to the Fos family members (Johnson et al., 1993; Ham et al., 1995; Verheij et al., 1996; Bossy-Wetzel et al., 1997; Le Niculescu et al., 1999; Schreiber et al., 1999; Wisdom et al., 1999; Kolbus et al., 2000). cJun–ATF2 and ATF2–ATF2 complexes recognize sequence motifs (8 bp) different from the 7 bp motifs bound by cJun–Fos AP-1 complexes (Benbrook and Jones, 1990; Ivashkiv et al., 1990; Hai and Curran, 1991; Chatton et al., 1994), and on minimal promoters cJun–ATF2 heterodimers are more potent transcriptional activators than ATF2–ATF2 homodimers (Benbrook and Jones, 1990; Huguier et al., 1998; van Dam et al., 1998). cJun–ATF2 target genes implicated in growth control include c-jun itself, ATF3, cyclin D1 and cyclin A (Liang et al., 1996; Shimizu et al., 1998; Beier et al., 1999, 2000; Bakiri et al., 2000).

A large number of stimuli, including cytokines, peptide growth factors, oncogenes, viruses and cellular stresses such as heat shock and DNA-damaging agents, induce cJun–ATF2 activity (Shaulian and Karin, 2001; van Dam and Castellazzi, 2001). One mechanism to establish this is by increasing the (limiting) levels of cJun, as ATF2 appears to be in excess in most cell types (van Dam and Castellazzi, 2001). Secondly, the transactivation capacities of the N-terminal domains of ATF2 and cJun can be enhanced through phosphorylation by the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) members p38 and JNK/SAPK (Davis, 2000; Chang and Karin, 2001; Kyriakis and Avruch, 2001). In the case of ATF2, this phosphorylation occurs at Thr69 and Thr71, which appears to enhance the intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity of ATF2 and to regulate its degradation by the ubiquitin pathway (Davis, 2000; Fuchs et al., 2000; Kawasaki et al., 2000). In addition, ATF2’s transactivating potential can be enhanced through direct or indirect binding to viral and cellular proteins, including adenovirus E1A (Liu and Green, 1990), the co-activator/acetyltransferase p300 (Kawasaki et al., 1998; Duyndam et al., 1999), the pX protein of hepatitis B virus, bZIP enhancer factor (bEF) and Tax, which stimulate DNA binding by increasing dimer formation and stability (Perini et al., 1999; Virbasius et al., 1999).

Activation of c-jun and other cJun–ATF2 target genes can be established via Ras and/or the related Ral- and Rho-GTPases (Minden and Karin, 1997; Wolthuis and Bos, 1999; Bar-Sagi and Hall, 2000). Ras-dependent phosphorylation of cJun is established via the RalGDS pathway (de Ruiter et al., 2000). Whether ATF2 is a bona fide downstream target of Ras is as yet unclear. Other signaling enzymes involved in cJun–ATF2 activation are the Src(-related) tyrosine kinases, which are downstream targets of mitogen-induced Ral activity (de Ruiter et al., 2000; Goi et al., 2000) and also seem to play a role in JNK-dependent activation of cJun by UV and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) (Devary et al., 1992; Liu et al., 1996).

The observation that various growth factors activate cJun–ATF2-inducible genes in cells lacking functional cJun protein (M.Hamdi, D.M.Ouwens and H.van Dam, unpublished results) suggested that ATF2 is activated efficiently by mitogens. In this study, we have investigated this as yet unknown mechanism of ATF2 activation. We show that insulin, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and serum can increase the transactivation potential of ATF2 by enhancing the phosphorylation state of ATF2 Thr69 and Thr71 in a JNK-independent manner. The phosphorylation of ATF2 by growth factors was established via an as yet unknown two-step mechanism, requiring two distinct Ras effector pathways. The Raf–MEK–ERK pathway was found to induce only phosphorylation of ATF2 Thr71, whereas the Ral–RalGDS–Src-p38–pathway was found to be essential for the subsequent phosphorylation of ATF2 Thr69.

Results

Insulin activates ATF2 through phosphorylation of Thr69 and Thr71

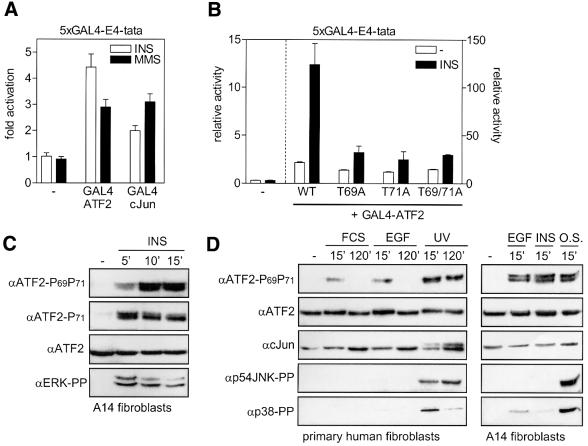

Cellular stresses and certain cytokines induce ATF2-dependent transcription through JNK/SAPK- and p38-dependent phosphorylation of the N-terminal ATF2 transactivation domain. However, growth factors that activate JNK/SAPK and p38 only very weakly can still induce ATF2-dependent promoters efficiently. This observation prompted us to examine the mechanism of mitogen-induced cJun–ATF2 activation. As shown for A14 fibroblasts in Figure 1A, we found that insulin efficiently activated hybrid proteins containing the transactivation domain of ATF2 fused to the DNA-binding domain of the yeast transcription factor GAL4. Insulin activated the transactivation domain of ATF2 much more efficiently than the corresponding domain of cJun, while the alkylating agent MMS, a potent inducer of JNK and p38, activated ATF2 and cJun to the same extent. Insulin- and EGF-induced activation of GAL4-ATF2 was found to require Thr69 and Thr71, but not Ser90, a third MAPK site present in the ATF2 transactivation domain (Figure 1B; data not shown). We subsequently analyzed the phosphorylation state of endogenous ATF2 by western blot analysis, using anti-phospho-Thr71-ATF2, an antibody that recognizes Thr71-mono-phosphorylated ATF2, and anti-phospho-Thr69 + 71-ATF2, an antibody that recognizes Thr69 + 71-dual-phosphorylated ATF2 but not mono-phosphorylated ATF2 (see Materials and methods). In A14 cells and 3T3L1 adipocytes, insulin was found to induce the phosphorylation of Thr69 and Thr71 strongly within 5 min after addition (Figure 1C; data not shown). Also, other mitogens such as EGF and serum strongly enhanced endogenous ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation, as depicted for A14 and primary human fibroblasts in Figure 1D. The levels of growth factor-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation were more or less comparable with those induced by cellular stresses, such as MMS, UVC and osmotic shock, although the mitogens had only weak stimulatory effects on the phosphorylation and activation of JNK/SAPK and p38 family members (Figure 1D, see below).

Fig. 1. Insulin activates ATF2 through phosphorylation of Thr69 and Thr71. (A) Insulin efficiently enhances the transactivating capacity of ATF2. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 2 µg of 5×GAL4-E4-luciferase reporter in the presence or absence of 2 µg of pRSV-GAL4-cJun-N, pRSV-GAL4-ATF2-N or an empty expression vector. At 20 h after transfection, the cells were incubated for 16 h with 10 nM insulin or 1 mM MMS. Transactivation by GAL4-cJun and GAL4-ATF2 in the absence of insulin and MMS was 2.4- and 46-fold, respectively. For comparison, only the fold activation (mean ± SD) by insulin and MMS is depicted, which represents the ratio between relative luciferase activity in the presence and absence of insulin or MMS. (B) Insulin-induced transactivation by ATF2 requires Thr69 and Thr71. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 µg of 5×GAL4-E4-luciferase reporter plasmid in the presence or absence of 2 µg of the indicated pC2-GAL4-ATF2 expression vectors, encoding either the wild-type (wt) ATF2 transactivation domain, or the corresponding domain in which Thr69 (T69A), Thr71 (T71A) or both (T69/71A) are replaced by alanine. At 6 h after transfection, the cells were stimulated for 16 h with 10 nM insulin. The relative activity is the enhancement of promoter activity by the various GAL4-ATF2 fusion proteins in the absence and presence of insulin, and is presented as the mean ± SD of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Note the different scaling of the left and right y-axis. (C) Insulin-induced ATF2 Thr71 and Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation. Serum-starved A14 cells were stimulated with 10 nM insulin for the indicated times. Total cell extracts (30 µg of protein) were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. Ponceau S staining confirmed that the filters contained equal amounts of protein extracts. The faster migrating bands seen by the phospho-specific ATF2 antibodies seem to represent shorter, alternatively spliced, ATF2 products (Georgopoulus et al., 1992). (D) Mitogen-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation does not correlate with JNK Thr183/Tyr185 and p38 Thr180/Tyr182 phosphorylation in A14 and primary human VH10 fibroblasts. Serum-starved cells were stimulated for the indicated times with 10 nM EGF, 10 nM insulin, 500 mM NaCl (O.S.), 10% FCS or 30 J/m2 UVC. Total cell extracts (30 µg of protein) were analyzed for the levels of the indicated proteins by SDS–PAGE and subsequent immunoblotting.

Differential phosphorylation of ATF2 Thr71 and Thr69 by the Raf–MEK and RalGDS–Ral effector pathways of Ras

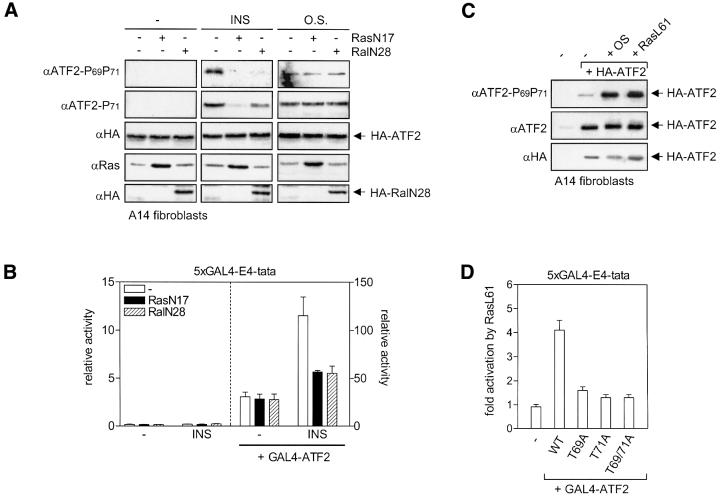

As insulin and EGF, but not MMS and osmotic stress, rapidly activate the Ras proteins (Burgering et al., 1991; D.M.Ouwens and H.van Dam, data not shown), we examined whether insulin- and EGF-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation is established via a Ras-dependent signaling cascade. The dominant-negative Ras mutant RasN17 efficiently inhibited insulin and EGF-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation as well as insulin- and EGF-induced activation of GAL4-ATF2, while having no inhibitory effect on ATF2 activation by osmotic stress and MMS (Figure 2A and B; data not shown). In line with this, a constitutively active mutant of Ras, RasL61, induced phosphorylation of ATF2 Thr69 + 71 to the same extent as osmotic stress (Figure 2C) and activated GAL4-ATF2 in a Thr69- and Thr71-dependent manner (Figure 2D). This indicates that an increase in Ras-GTP levels is sufficient to trigger ATF2 activation.

Fig. 2. Ras-dependent growth factor-induced activation of ATF2. (A) Inhibition of insulin-induced ATF2 phosphorylation by dominant-negative Ras and Ral. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 µg of pMT2-HA-ATF2 in the presence or absence of 2 µg of pRSV-RasN17, pMT2-HA-RalN28 or an empty expression vector. Fugene reagent was used in order to obtain high levels of transfection efficiency (>40%). At 24 h after transfection, the cells were stimulated with either 10 nM insulin (15 min) or 500 mM NaCl (O.S.) (15 min). A 30 µg aliquot of total cell extract was analyzed by SDS–PAGE/immunoblotting. Ectopically expressed RasN17, HA-ATF2 and HA-RalN28 were detected using monoclonal Y13-259 Ras and HA antibodies, respectively. Comparison of the extracts of mock-transfected cells with those of HA-ATF2 transfected cells verified that only exogenous HA-ATF-2 is detected on the exposures shown [data not shown; compare with (C) and Figure 5F]. (B) Insulin-induced GAL4-ATF2-dependent transactivation is inhibited by RasN17 and RalN28. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 µg of 5×GAL4-E4-luciferase reporter together with 2 µg of expression vectors for RasN17 and RalN28, or an empty control vector, in the presence or absence of either 1 µg of pRSV-GAL4-ATF2-N or an empty expression vector. Cells were serum starved for 24 h, followed by stimulation with 10 nM insulin for 14 h. Depicted is the enhancement of promoter activity by GAL4-ATF2 in the absence and presence of insulin and/or the inhibitors (mean ± SD). Note the different scaling of the left and right y-axis. (C) Active RasL61 induces ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation. A14 cells were kept untreated (–), or transfected with 0.5 µg of pMT2-HA-ATF2 in the presence or absence of 2 µg of RasL61 expression vector, or an empty vector (–). Fugene reagent was used in order to obtain high levels of transfection efficiency (>40%). At 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with NaCl (O.S.), as described for Figure 1D, when indicated, and total cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. (D) Active RasL61 enhances transactivation by ATF2 via ATF2 Thr69 and Thr71. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 2 µg of 5×GAL4-E4-luciferase reporter plasmid together with 2 µg of pRSV-GAL4-ATF2 expression vectors containing full-length (wt) ATF2, or the corresponding domain in which Thr69 (T69A), Thr71 (T71A) or both (T69/71A) are replaced by alanine. In addition to these GAL4 fusion constructs, 3 µg of pRSV-RasL61, or an empty expression vector, was co-transfected. At 40 h after transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed for luciferase activity. The fold activation depicted represents the ratio between luciferase activity (mean ± SD) in the presence and absence of RasL61.

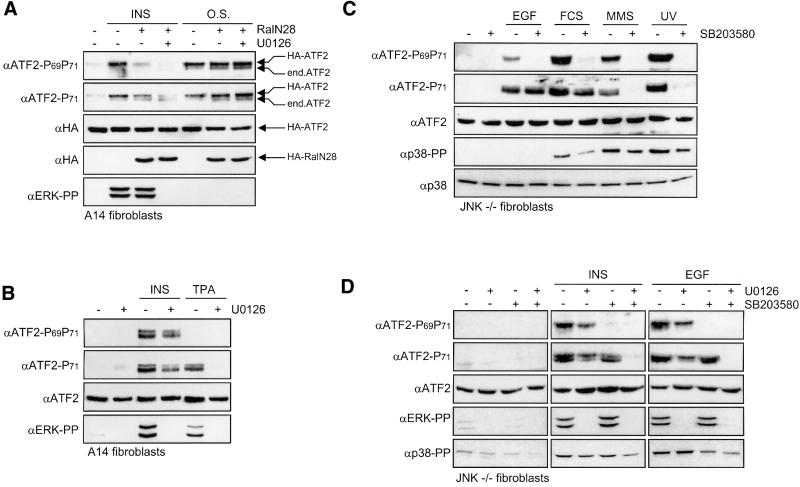

Since Ras can induce gene expression via three different effector pathways, Raf–MEK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)–PKB and RalGDS–Ral (Bos, 1998), we next analyzed the involvement of these pathways in ATF2 activation. Inhibition of the PI3-K–PKB pathway by wortmannin and/or LY294002 had no effect on the induction of ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation by mitogens (data not shown). In contrast, the dominant-negative Ral mutant RalN28 efficiently blocked insulin-induced activation of GAL4-ATF2 and the insulin-induced phospho-Thr69 + 71 signal (Figure 2A and B). However, in contrast to RasN17, RalN28 appears to inhibit insulin-induced ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation only partially (Figure 2A). Efficient inhibition of the phospho-Thr71 signal was only observed when the cells were, in addition to RalN28, also pre-treated with the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Figures 2A and 3A). Like dominant-negative Ras, the combination of RalN28 and U0126 had no effect on osmotic stress-induced ATF2 phosphorylation (Figure 3A).

Fig. 3. Differential phosphorylation of ATF2 Thr71 and Thr69 by the Raf–MEK and RalGDS–Ral effector pathways of Ras. (A) Inhibition of insulin-induced ATF2 phosphorylation by RalN28 and the MEK inhibitor U0126. A14 cells were transfected and stimulated with either insulin or NaCl (O.S.) as described for Figure 2A. Where indicated, the cells were pre-treated for 30 min with 10 µM U0126. A 30 µg aliquot of total cell extract was analyzed by SDS–PAGE/immunoblotting. The positions of the exogenously expressed HA-ATF2 and the faster migrating endogenous (end.) ATF2 are indicated on the right. (B) Activation of the Raf–MEK pathway induces ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation. Serum-starved A14 cells were incubated for 30 min in the absence or presence of 10 µM U0126 prior to treatment with 10 nM insulin or 100 nM TPA. Total cell extracts (30 µg of protein) were prepared after 15 min, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE/immunoblotting. (C) Differential effects of SB203580 on ATF2 Thr71 phosphorylation induced by growth factors and stresses. Serum-starved JNK1+2–/– fibroblasts were incubated for 30 min in the absence or presence of 5 µM SB203580 prior to treatment with 10 nM EGF, 20% FCS, 30 J/m2 UVC or 1 mM MMS as indicated. Total cell extracts (30 µg of protein) were prepared after 15 min (except for MMS: 2 h), and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and subsequent immunoblotting. (D) Differential effects of SB203580 and U0126 on ATF2 Thr71 and Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation. Serum-starved JNK1+2–/– fibroblasts were treated for 30 min with 5 µM SB203580 and/or 10 µM U0126 prior to stimulation for 15 min with 10 nM insulin or 10 nM EGF as indicated. Total cell extracts (30 µg of protein) were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting.

In the absence of RalN28, insulin-induced ATF2 Thr71 and Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation was only partially (∼55%) inhibited by U0126, despite the fact that MEK-dependent ERK phosphorylation was completely abrogated (Figure 3B). As this residual ATF2 phosphorylation seems to be due to the slight potentiating effect of U0126 on insulin-induced JNK and p38 activity (data not shown), we used the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) to examine further the role of the Raf–MEK pathway in ATF2 activation. TPA is a potent inducer of Raf and MEK in A14 cells, but does not activate RalGDS (Wolthuis et al., 1998a) and JNK/p38 (data not shown). Importantly, in contrast to insulin or EGF treatment, TPA treatment did not induce detectable ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation, but did induce a strong phospho-Thr71 signal, which was completely prevented upon pre-treatment with U0126 (Figure 3B). These results indicate that activation of the Raf–MEK pathway is only sufficient for ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation and that ATF2 Thr69 + 71 dual phosphorylation requires additional activation of the RalGDS–Ral pathway.

We next examined the effect of the p38 inhibitor SB203580 on insulin- and EGF-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation. Since SB203580 was found to enhance the activation of JNK by these mitogens strongly in fibroblasts (data not shown), we used JNK1+2–/– fibroblasts (K.Sabapathy, K.Hochedlinger, A.Bauer, L.Chang, M.Karin and E.Wagner, submitted). Interestingly, also in the presence of SB203580, differential regulation of ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation and ATF2 Thr69 + 71 dual phosphorylation by growth factors was observed: SB203580 completely blocked the insulin-, EGF- and serum-induced phospho-ATF2 Thr69 + 71 signal, but only very weakly suppressed insulin-induced ATF2 Thr71 phosphorylation and did not inhibit EGF-induced ATF2 Thr71 phosphorylation at all (Figure 3C and D). In contrast, MMS- and UV-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 and ATF2 Thr71 phosphorylation were both completely inhibited by SB203580 (Figure 3C). As previously found for A14 cells (Figure 3B), inhibition of MEK with U0126 also only partially (50–70%) prevented insulin-induced ATF2 Thr71 phosphorylation in JNK–/– cells (Figure 3D). Since the residual insulin-induced Thr71 phosphorylation could be inhibited by SB203580, both MEK and p38 appear to be required for ATF2 Thr71 phosphorylation by insulin (Figure 3D). However, in the case of EGF, the residual Thr71 phosphorylation in the presence of U1026 seems to be due mainly to the potentiating effect of U0126 on the activation of p38 (Figure 3D; data not shown): U0126 and SB203580 completely blocked ATF2 Thr71 phosphorylation by EGF when added together, but SB203580 only inhibited Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation, and not Thr71 phosphorylation, when added alone (Figure 3D). These data strongly suggest that the induction of ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation by EGF occurs mainly via a MEK-dependent process, and that p38 only plays a role when the MEK pathway is inhibited.

In summary, the results presented above indicate that growth factors can activate ATF2 via an as yet unknown two-step mechanism: Thr71 mono-phosphorylation executed predominantly by the Ras–Raf–MEK pathway and (subsequent) Thr69 + 71 dual phosphorylation via RalN28- and SB203580-inhibitable factors.

Insulin- and EGF-induced ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation is mediated by ERK

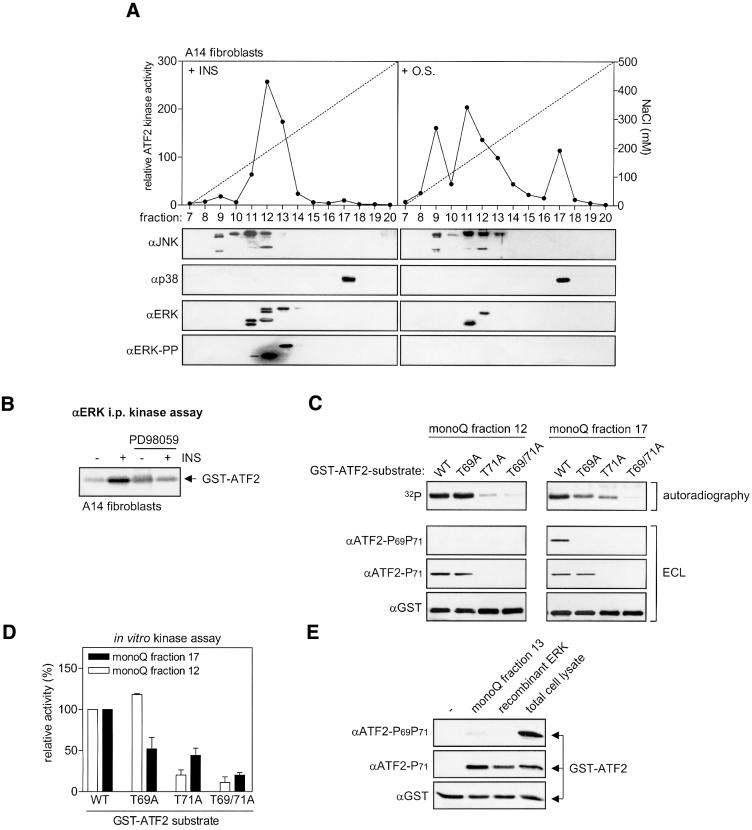

To identify the Ras–MEK-induced ATF2 Thr71 kinase, we performed anion-exchange chromatography of A14 cell extracts on MonoQ columns. As depicted in Figure 4A, the bulk of the insulin-induced ATF2 kinase activity (fractions 12 and 13) contained high levels of active (mobility-shifted and phosphorylated) ERK1 and ERK2, no p38 and only low amounts of (non-mobility-shifted) JNK (compare fractions 9 and 11 with fractions 12 and 13 in Figure 4A). The induction of the kinase activity in fraction 12 + 13 by insulin was inhibited specifically by pre-treatment with the MEK inhibitors U0126 or PD98059 (data not shown; compare Figure 4B). In contrast to the insulin-induced ATF2 kinase, the osmotic stress-induced ATF2 kinase activity co-purified with JNK/SAPK [fractions 9 and 11–13; predominantly containing (mobility-shifted active) JNK] and p38 (fraction 17; Figure 4A). Also, in EGF-treated JNK–/– cells, nearly all of the ATF2 kinase activity co-purified with phosphorylated ERK1/2 (90%) rather than with p38 (5%). Co-purification of ERK1/2 and this ATF2 kinase activity was still observed after subsequent monoQ chromatography of fraction 12 at pH 7.8 instead of pH 7.5, which led to a further separation of ERK1 and ERK2, and after refractionation on a MonoS column (data not shown). We subsequently analyzed immunopurified ERK for mitogen-inducible MEK-dependent ATF2 kinase activity. Insulin, but not osmotic stress, enhanced ERK-associated N-terminal ATF2 kinase activity ∼4.8-fold, which was inhibited by pre-treatment with the MEK inhibitors PD98059 and U0126 (Figure 4B; data not shown). Thus, in A14 and JNK–/– cells, the major mitogen-inducible ATF2 kinase appears to be ERK1/2 rather than JNK/SAPK and p38 (family members).

Fig. 4. Insulin- and EGF-induced ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation is mediated by ERK. (A) The main insulin-induced ATF2 N-terminal kinase activity co-purifies with ERK1/2 after MonoQ anion-exchange chromatography. Total cell lysates from A14 cells treated for 15 min with either 10 nM insulin or 500 mM NaCl (O.S.) were separated on a MonoQ column using a linear gradient of NaCl (dotted line). Fractions were analyzed for in vitro ATF2 kinase activity (filled circles) as described in Materials and methods, and for the presence of JNK, ERK1/2 and p38 by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. (B) Insulin induces ERK-associated ATF2 N-terminal kinase activity. Serum-starved A14 cells were either untreated or treated for 15 min with 10 nM insulin, with or without 15 min pre-treatment with 20 µM PD98059, as indicated. Total cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies that recognize both ERK1 and ERK2, and subsequently assayed for ATF2-kinase activity. (C) Insulin-induced ERK and p38 activities differ in their ATF2 Thr69 and Thr71 kinase activities. Partially purified ERK and p38 preparations from insulin-stimulated A14 cell extracts (MonoQ fractions 12 and 17, respectively) were analyzed for in vitro kinase activity, using either wild-type (wt) or mutant GST–ATF2 fusion proteins in which Thr69 (T69A), Thr71 (T71A) or Thr69 + 71 (T69/71A) were replaced by alanine. The phosphorylation state subsequently was monitored by SDS–PAGE followed by autoradiography and immunoblotting using phospho-specific antibodies followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL). (D) Quantification of 32P incorporation into GST–ATF2 by MonoQ fractions 12 and 17 in in vitro kinase assays as described in (C). The relative activity (mean ± SD) shown represents the 32P incorporation in the various mutant GST–ATF2 substrates relative to that in the wild-type GST–ATF2 protein (set at 100% for both fractions 12 and 17). (E) Recombinant active ERK only phosphorylates ATF2 Thr71 efficiently. Recombinant ERK (10 U; Calbiochem) was compared with MonoQ fraction 13 and total cell lysate from insulin-treated A14 cells for its ATF2 kinase potential using GST–ATF2 as a substrate. The phosphorylation state of GST–ATF2 Thr69 + 71 and GST–ATF2 Thr71 subsequently was monitored by SDS–PAGE/immunoblotting using phospho-specific antibodies. Equal loading of the GST–ATF2 substrate was verified by reprobing the filters with GST antibodies.

We next examined the ERK-containing MonoQ fractions 12 and 13 of insulin-stimulated A14 and EGF-treated JNK–/– cells for their ability to phosphorylate ATF2 Thr71, Thr69 and Thr69 + 71. In these assays, we included ATF2 substrates in which Thr69 and/or Thr71 were replaced by alanines and analyzed both the incorporation of radioactive phosphate and the anti-phospho-Thr71 and anti-phospho-Thr69 + 71 immunoreactivity. As shown in Figure 4C–E, A14 fractions 12 and 13 could only phosphorylate ATF2 Thr71 of the GST–ATF2 substrate efficiently, whereas partially purified p38 (fraction 17) and the input total cell lysate efficiently phosphorylated both Thr69 and Thr71. Similar Thr71-only phosphorylation was observed in the case of fractions 12 and 13 of EGF-treated JNK–/– cells (data not shown). To exclude the possibility that the Thr71-specific kinase in these fractions is not ERK itself, but an ERK-associated kinase, we also examined recombinant active ERK for its specificity for Thr71 and Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation. Like the ERK-containing MonoQ fractions, recombinant ERK only phosphorylated ATF2 Thr71 efficiently (Figure 4E).

In summary, these data identify ERK1/2 as the main Ras–Raf–MEK-inducible ATF2 Thr71 kinase activity in insulin- and EGF-treated fibroblasts. In line with this, in vivo insulin-induced ERK phosphorylation and ATF2 Thr71 phosphorylation occurred nearly simultaneously in A14 cells, whereas the onset of ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation was somewhat delayed (Figure 1C).

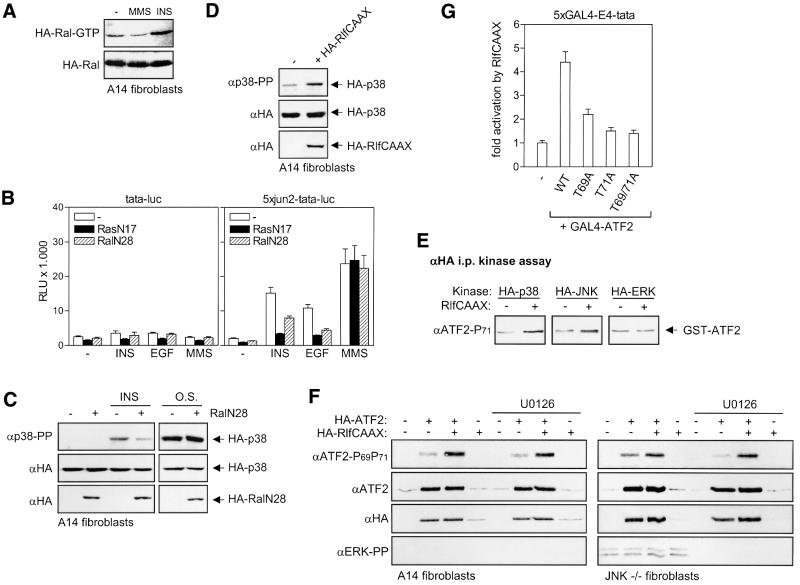

The RalGDS–Ral pathway mediates p38 activation and ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation by growth factors but not by stresses

We next examined the role of Ral activation in the phosphorylation and transcriptional activation of ATF2 in further detail. Enhanced levels of Ral-GTP could only be induced by mitogens in A14 cells, as depicted for insulin and MMS in Figure 5A (see also Wolthuis et al., 1998a). In line with this, RalN28, like dominant-negative RasN17, inhibited the activation of ATF2 by insulin and EGF, but did not inhibit MMS- and osmotic stress-induced ATF2 phosphorylation (Figure 2A; data not shown). Moreover, both RasN17 and RalN28 inhibited the activation of the minimal ATF2-dependent promoter 5×jun2-tata by insulin and EGF, but not the activation by MMS (Figure 5B). Thus, Ral mediates the activation of ATF2 by insulin and EGF rather than by stress stimuli.

Fig. 5. The RalGDS–Ral pathway mediates insulin- and EGF-induced activation of ATF2-dependent gene expression. (A) The effects of insulin and MMS on Ral activity. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 3 µg of pMT2-HA-Ral. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were serum-starved overnight followed by stimulation with either 10 nM insulin (15 min) or 1 mM MMS (2 h). Total cell extracts (750 µg of protein) were incubated with 15 µg of GST–RalBD pre-coupled to glutathione beads to recover GTP-bound Ral. Beads were washed extensively, and collected Ral was detected by immunoblotting with HA antibody. (B) Insulin- and EGF-induced activation of ATF2-dependent transcription is inhibited by RasN17 and RalN28. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 2 µg of either the cJun–ATF2-dependent luciferase reporter 5×jun2-tata or the tata-luciferase control, in the presence or absence of 2 µg of expression vectors for RasN17 and RalN28, or an empty control vector. At 20 h after transfection, the cells were stimulated for 6 h with 10 nM insulin or 1 mM MMS. Depicted is the relative luciferase activity (RLU) ± SD. (C) Dominant-negative Ral inhibits insulin-induced p38 phosphorylation. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 0.5 µg of pMT2-HA-p38 in the presence or absence of 1.5 µg of pMT2-HA-RalN28, or an empty expression vector as described in Figure 2A. Subsequently, the cells were serum-starved and treated with either 10 nM insulin or 500 mM NaCl (O.S.). Total cell extracts were prepared after 15 min, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE/immunoblotting. For better comparison, a relatively short exposure of osmotic shock-induced HA-phospho-p38 is shown. (D) Activation of Ral by RlfCAAX induces p38 phosphorylation. A14 cells were transfected with 0.5 µg pMT2-HA-p38 in the presence or absence of 0.125 µg of HA-RlfCAAX, or an empty vector (–) as described above. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were serum-starved and, after an additional 24 h, total cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. (E) Activation of Ral by RlfCAAX induces p38 and JNK kinase activity. A14 cells were transfected with 0.5 µg of expression vectors encoding HA-tagged p38, JNK or ERK, respectively, in the presence or absence of 0.125 µg of HA-RlfCAAX expression vector, or an empty vector (–) as described above. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were serum-starved and, after an additional 24 h, total cell lysates were prepared. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an HA antibody, after which HA-associated ATF2 Thr71 kinase activity was measured using GST–ATF2 as substrate (see Materials and methods). (F) Activation of Ral by RlfCAAX induces ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation. A14 and JNK–/– cells were left untreated (–) or transfected with 0.5 µg of pMT2-HA-ATF2 in the presence or absence of 0.125 µg of RlfCAAX expression vector. Fugene reagent was used in order to obtain high levels of transfection efficiency (>40%). At 24 h after transfection, cells were serum-starved overnight, and incubated for a further 24 h in the presence or absence of 10 µM U0126 prior to preparation of cell lysates and analysis by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. Note that HA-ATF2 and HA-RlfCAAX (detected by the HA antibody) have nearly the same molecular weight. (G) RlfCAAX enhances transactivation by ATF2 via ATF2 Thr69 and Thr71. A14 cells were transiently transfected with 2 µg of 5×GAL4-E4-luciferase reporter plasmid together with 2 µg of pRSV-GAL4-ATF2 expression vectors containing full-length (wt) ATF2, or the corresponding domain in which Thr69 (T69A), Thr71 (T71A) or both (T69/71A) are replaced by alanine. In addition to these GAL4 fusion constructs, 3 µg of pMT2-RlfCAAX, or an empty expression vector was co-transfected. At 40 h after transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed for luciferase activity. The fold activation depicted represents the ratio between luciferase activity in the presence and absence of RlfCAAX. Values represent the mean ± SD.

As both p38 and Ral were found to be essential for ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation by growth factors, we next examined the role of the RalGDS pathway in the activation of p38. Dominant-negative RalN28 inhibited the weak activation of p38 induced by insulin and EGF, but had no effect on the strong induction of p38 phosphorylation by osmotic stress (Figure 5C; data not shown). To activate Ral in the absence of growth factors, we made use of RlfCAAX, a constitutively active, membrane-targeted, mutant of the Ral exchange factor Rlf (Wolthuis et al., 1997). In line with the role of Ral in growth factor-induced activation of p38, chronic activation of Ral by RlfCAAX enhanced both the phosphorylation of p38 and the p38-associated ATF2 kinase activity, in both A14 and JNK–/– fibroblasts (Figure 5D and E; data not shown). As reported previously (de Ruiter et al., 2000), RlfCAAX was also found to activate JNK (Figure 5E). However, RlfCAAX did not activate ERK (Figure 5E), which is in agreement with the fact that ERK activation by insulin or EGF is completely dependent on the Ras– Raf–MEK pathway in A14 cells (Figure 3B), and not mediated by RalGDS–Ral (de Ruiter et al., 2000). Also, in JNK–/– fibroblasts, the activation of ERK was found to be completely dependent on the MEK pathway (Figure 3D).

We next examined the effect of Ral activation by RlfCAAX on ATF2 Thr69 and Thr71 phosphorylation. In line with the fact that RlfCAAX activates p38 rather than MEK–ERK, we found that RlfCAAX induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation and that this phosphorylation could not be inhibited by U0126, in both A14 cells and JNK–/– cells (Figure 5F). RlfCAAX also stimulated transactivation by GAL4-ATF2, dependent on the presence of both Thr69 and Thr71 (Figure 5G). Moreover, RlfCAAX and active Ras induced the activity of the minimal ATF2-dependent 5×jun2-tata promoter in A14 cells, and this effect could be blocked by co-expression of RalN28 (data not shown). This indicates that activation of Ral in fibroblasts triggers both ATF2 Thr69 + 71 dual phosphorylation and ATF2 transcriptional activation.

In summary, these results show that activation of Ral leads to activation of p38 which, unlike ERK, can phosphorylate ATF2 on both Thr69 and Thr71. In addition, the results show that Ral activation mediates the activation of p38 and ATF2 by insulin and EGF rather than by stresses.

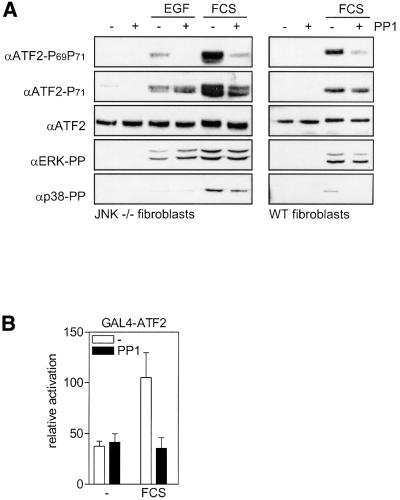

In addition to Ral, Src-like proteins are required for growth factor-induced ATF2 Thr69 phosphorylation

To elucidate further the signaling cascade that mediates Ral-dependent p38 activation and ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation, we examined the role of the Src-like tyrosine kinases, which have been identified as downstream targets of mitogen-induced Ral activity (de Ruiter et al., 2000; Goi et al., 2000). The Src inhibitor PP1 prevented EGF- and serum-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 dual phosphorylation, but only partially suppressed serum-induced ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation and did not inhibit EGF-induced ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation at all (Figure 6A). Serum-induced transactivation by GAL4-ATF2 was also inhibited efficiently by PP1 (Figure 6B). These data indicate that like Ral, Src(-like) tyrosine kinases are required for mitogen-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 dual phosphorylation rather than for ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation.

Fig. 6. Src-like proteins are required for growth factor-induced ATF2 Thr69 phosphorylation. (A) Serum-starved JNK1+2–/– and wild-type 3T3 fibroblasts were incubated for 30 min in the absence or presence of 10 µM PP1 prior to stimulation with 10 nM EGF, or 20% FCS as indicated. Total cell extracts (30 µg of protein) were prepared after 15 min, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE/immunoblotting. (B) Serum- induced transactivation by GAL4-ATF2 is inhibited by PP1. 3T3 fibroblasts were transiently transfected with 0.5 µg of 5×GAL4-E4- luciferase reporter plasmid in the presence or absence of 2 µg of pC2-GAL4-ATF2 expression vector. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were serum-starved overnight prior to treatment for 14 h with 20% FCS in the presence or absence of 10 µM PP1. The relative activation is the enhancement of promoter activity by the GAL4-ATF2 fusion protein in the absence and presence of serum, and is presented as the mean ± SD of two independent experiments performed in triplicate.

As the Src inhibitor PP1 had the same selective effects on ATF2 Thr69 + 71 dual phosphorylation as the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (Figure 3C and D), we next examined the effect of PP1 on the activation of p38 by mitogens. As shown in Figure 6A, the (relatively weak) phosphorylation of p38 by EGF and serum was reduced by the Src inhibitor, whereas the activation of ERK was not inhibited significantly.

In summary, these results show that insulin, EGF and serum activate ATF2-dependent gene expression via two distinct Ras effector pathways, Raf–MEK–ERK and RalGDS–Ral–Src–p38, that control independent phosphorylation events.

Discussion

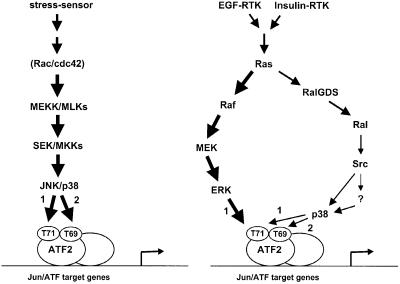

We have shown that ATF2’s transactivating capacity is enhanced efficiently via Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation by mitogens that do not significantly activate the stress-activated MAPK pathways and only weakly enhance the transactivation function of cJun. This strong enhancement in ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation explains the activation by growth factors of cJun–ATF2-dependent genes in cells lacking functional cJun protein, as in c-jun–/– fibroblasts. The regulation of ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation by growth factors was found to be complex, as it is not performed by a single kinase. At least two distinct MAPKs, ERK and p38, are required, and, importantly, were found to exhibit distinct ATF2 Thr69 and Thr71 substrate specificities. Unlike active p38 and JNK, active ERK was only able to mono-phosphorylate ATF2 Thr71 efficiently both in vivo and in vitro. In contrast to ERK, the activities of p38 and SAPK/JNK are very low in insulin- or EGF-stimulated fibroblasts and, therefore, insufficient to phosphorylate ATF2 Thr71 and/or Thr69 efficiently by themselves (Figures 1D and 4A). However, these low levels of active p38 are essential and appear to be sufficient to phosphorylate Thr69 when ATF2 Thr71 is already mono-phosphorylated by ERK (see the model in Figure 7). To our knowledge, this is the first example of complementary phosphorylation of a single substrate by ERK and p38. Therefore, it appears to reveal a novel level of complexity and recombination potential in the cross-talk of the cellular signaling networks.

Fig. 7. Proposed model for the order of events leading to ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation by growth factors and stresses. For details, see Discussion.

Interestingly, recent in vitro kinetic studies using recombinant active p38α expressed in Escherichia coli showed that p38 phosphorylates GST–ATF2 (amino acids 1–115) via a two-step (double collision) mechanism, involving the dissociation of mono-phosphorylated ATF2 Thr71 or Thr69 from the enzyme after the first phosphorylation step (Waas et al., 2001). Moreover, these authors found that mono-phosphorylation of ATF2 Thr69 strongly reduces the phosphorylation rate of Thr71, whereas, in contrast, mono-phosphorylation of Thr71 does not reduce the rate of Thr69 phosphorylation. Thus, efficient phosphorylation of ATF2 by recombinant E.coli-expressed active p38 only occurs in the order Thr71→ Thr69 + 71 (Figure 7). This order of events also seems to occur in mitogen-treated cells, as ERK, in contrast to p38, does not seem to mono-phosphorylate Thr69 significantly (Figure 4C).

The fact that ERK does not double-phosphorylate ATF2 Thr69 + 71 efficiently raises the question as to whether Thr71 mono-phosphorylated ATF2 can still bind to the ATF2 (DEJL) docking site of ERK (Jacobs et al., 1999). A related question is whether Thr71 mono-phosphorylated ATF2 binds more efficiently to (weakly active) p38 than non-phosphorylated ATF2. These questions are of particular interest with respect to the recent identification of the docking grooves in ERK and p38 that regulate the specificities of the ERK and p38 docking interactions (Tanoue et al., 2001). Other matters arising are whether ERK1 and 2 are the only ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylating kinases, or whether other MAPK family members (in cell types other than fibroblasts) have the same ATF2 substrate specificity.

The role of the JNK/SAPK family members in the activation of ATF2 by mitogens has not yet been completely resolved. In the presence of ERK and p38, JNK is not essential for ATF2 phosphorylation, as shown in JNK–/– fibroblasts. Moreover, JNK1/2 are only weakly activated by insulin, EGF and serum in many cell types, and are, under those conditions, like p38, unable to phosphorylate ATF2 efficiently by themselves. Furthermore, SEK1, one of the upstream activators of JNK, was found to be required for the phosphorylation of ATF2 Thr71 by MMS, but not by insulin and EGF in A14 cells (our unpublished results). However, our preliminary data suggest that, like p38, JNK might be able to phosphorylate Thr69 on ATF2 substrates that are already phosphorylated on Thr71 by ERK.

This study also reveals an as yet unknown role for Ras and the Ras effector pathways in the control of ATF2 phosphorylation. We found Ras to be essential for the phosphorylation and activation of ATF2 by EGF and insulin, but not by MMS or osmotic stress. Intriguingly, two different Ras effector pathways are required for this growth factor-specific mechanism of ATF2 activation. The Raf–MEK–ERK pathway was found only to trigger ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation, providing an explanation for the fact that the phorbol ester TPA, a strong activator of the Raf–MEK–ERK pathway, does not activate ATF2-dependent reporter genes significantly in various cell types (van Dam et al., 1995). In contrast to the Raf–MEK pathway, the Ras–RalGDS–Ral–Src pathway was found to be required for insulin- and EGF-induced ATF2 Thr69 + 71 dual phosphorylation rather than for ATF2 Thr71 mono-phosphorylation. The RalGDS–Ral pathway is not activated by MMS in fibroblasts, and dominant-negative Ral did not inhibit ATF2 Thr69 + 71 phosphorylation and activation by MMS. Thus, the Ras–Raf–MEK–ERK and Ras–RalGDS–Ral–Src–p38 pathways seem specifically to cooperate in the activation of ATF2 by Ral-activating growth factors (see model in Figure 7).

The involvement of the Ras–RalGDS–Ral pathway in the activation of cJun–ATF2-dependent gene expression suggests an important contribution of cJun–ATF2 target genes in Ras-, Rlf- and/or Ral-dependent cell cycle progression, differentiation and oncogenic transformation (Verheijen et al., 1999; Wolthuis and Bos, 1999; Reuther and Der, 2000). In addition to the c-jun gene itself, cJun–ATF2 target genes implicated in transformation appear to comprise, amongst others, ATF3, cyclin D, cyclin A and the urokinase receptor (Liang et al., 1996; Shimizu et al., 1998; Beier et al., 1999, 2000; Bakiri et al., 2000; Okan et al., 2001). Interestingly, cJun–ATF2 heterodimers have been found to induce the same partial transformation program as the gain-of-function Rlf mutant Rlf-CAAX, which enables fibroblasts to proliferate in very low concentrations of serum but not in soft agar (Wolthuis et al., 1997; Huguier et al., 1998; van Dam et al., 1998). Therefore, Ras, Rlf and Ral might also activate genes coding for growth factors and/or growth factor receptors via cJun–ATF2.

In summary, the finding that activation of ATF2 by growth factors and Ras proteins requires the cooperative action of two different Ras effector pathways, each mediating specific and sequential phosphorylation steps, identifies an as yet unknown mechanism by which Ras proteins and MAPK pathways can control gene expression and cell proliferation. This mechanism also explains why mitogenic stimuli and Ras proteins can induce transcription of ATF2 target genes efficiently while only very weakly activating the stress-inducible MAPKs.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs

The following expression vectors have been described: pRSV-Gal4- cJun-N (Radler-Pohl et al., 1993); pRSV-GAL4-ATF2-N (amino acids 19–112), pRSV-GAL4-ATF2 (amino acids 19–505) wt, -T69A, -T71A, -T69/71A (Duyndam et al., 1996); pC2-GAL4-ATF2-TAD wt, -T69A, -T71A, -T69/71A (Livingstone et al., 1995); pMT2-HA-Ral, pMT2-HA-RalN28, pMT2-HA-RlfCAAX (Wolthuis et al., 1997); pRSV-RasL61, pRSV-RasN17 (Medema et al., 1991); and pGEX-ATF2-N (van Dam et al., 1995). pGEX-ATF2-N-T69A, -T71A and T69/71A were constructed by ligating the SalI–XbaI fragment of the corresponding pC2-GAL4-ATF2-TAD vector (Livingstone et al., 1995) into SalI–XbaI-digested pGEX-ATF2-N. pET16B-p54JNK (amino acids 31–333) was generated by PCR using as primers 5′-cctggatccgatcggctctgggg and 5′-ggcggatccgcctccacttcagc, and as template rat HA-p54JNK (Sanchez et al., 1994; kindly provided by J.R.Woodgett). The BamHI-restricted PCR product subsequently was inserted into BamHI-digested pET16B (Novagen). pMT2-HA-p38 was generated by PCR using as primers 5′-aagtcgacaatgtctcaggagaggccc and 5′-agcggctcaggactccatctcttct, and as template pGEX4T3-p38/SAPK2a (kindly provided by Dr P.Cohen). The PCR product was ligated into pGEMT (Promega) to obtain pGEMT-p38, and the SalI–NotI fragment from pGEMT-p38 subsequently was inserted into SalI–NotI-restricted pMT2-HA (Wolthuis et al., 1997). pMT2-HA-ATF2 was constructed by fusing amino acids 19–505 of human ATF2 C-terminal to the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope of pMT2. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

The luciferase reporter constructs tata-luc and 5×jun2-tata-luc have been described (van Dam et al., 1998). For 5×Gal4-E4-tata-luciferase, the PvuII–BamHI fragment of 5×Gal4-E4-pGl2 (C.Livingstone and N.C.Jones, unpublished) was inserted into SmaI–BglII-restricted pGL3-basic.

Chemicals

Insulin from bovine pancreas, TPA and MMS were obtained from Sigma; recombinant human EGF from Peprotech, Inc. Rocky Hill, NJ; PD98059 and SB203580 from Calbiochem; U0126 from Promega; and PP1 from Alexis Biochemicals.

Cell culture, transient transfection and luciferase assays

Primary human VH10 fibroblasts, A14 cells (NIH 3T3 cells overexpressing the human insulin receptor; Burgering et al., 1991) and JNK–/– fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 9% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. Immortalized JNK–/– fibroblasts were derived from mouse JNK 1+2 double knockout embryos using the 3T3 protocol (K.Sabapathy, K.Hochedlinger, A.Bauer, L.Chang, M.Karin and E.Wagner, submitted); kindly provided by Kanaga Sabapathy and Erwin Wagner, IMP Vienna). For luciferase assays, A14 cells were transfected on 6 cm dishes by the DEAE–dextran method as described elsewhere (Angel et al., 1988). Cells were lysed in 200 µl of 25 mM Tris–PO4 pH 7.8, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2 mM 1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 10% glycerol and 1% Triton X-100, after which luciferase activity was determined according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). For protein phosphorylation analysis, 6 cm dishes of A14 or JNK–/– fibroblasts were transfected with Fugene (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blot analysis and antibodies

Cell lysates were prepared from 6 cm dishes that were rinsed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed in 200 µl of ice-cold Fos-RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (van Dam et al., 1993). Extracts were cleared by centrifugation (4°C, 14 000 g, 30 min), and the protein content was determined using the BCA kit (Pierce). Proteins were separated on 10% polyacrylamide slab gels and transferred to Immobilon (Millipore). Blots were stained with Ponceau S before blocking to verify equal loading and appropriate protein transfer. Filters were incubated with antibodies as described previously (Ouwens et al., 1994). Filters were stripped by a 30 min incubation in 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8 at 50°C.

Anti-JNK antibody was obtained by immunizing rabbits with a recombinant His-tagged JNK fusion protein produced from pET16B-p54JNK (amino acids 31–333) as described previously (Ouwens et al., 1994). Monoclonal anti-Ras antibody Y13-259 was kindly provided by Dr A.Zantema. The other antibodies used were: phospho-specific ATF2 Thr69 + 71, ATF2 Thr71, p38 Thr180/Tyr182, ERK hr202/Tyr204 (Cell Signaling Technology), p38 (N-20), ATF-2 (C-19), cJun (H-79), ERK (K-23), donkey anti-goat IgG–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), monoclonal anti-HA antibody 16B12 (BabCO), anti-GST (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), phospho-specific JNK Thr183/Tyr185, goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse IgG–HRP conjugate (Promega).

The specificity of the phospho-Thr71 and phospho-Thr69 + 71 ATF2 antibodies (www.cellsignal.com) was verified by comparing the immunoreactivity and [32P]phosphate incorporation of the wild-type, T69A, T71A and T69A + 71A GST–ATF2 substrates upon phosphorylation by ERK and p38. The phospho-Thr69 + 71 antibody efficiently recognizes Thr69 + 71 dual-phosphorylated ATF2, but not Thr71-mono-phosphorylated ATF2, and also not the Thr69-mono-phosphorylated T69A71 substrate. The phospho-Thr71 antibody recognizes Thr71-mono-phosphorylated ATF2 very efficiently, but not the Thr69-mono-phosphorylated T69A71 substrate (Figure 4C).

MonoQ/anion-exchange chromatography

Anion-exchange chromatography was performed essentially as described by Rouse et al. (1994). Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and scraped in MonoQ lysis buffer [20 mM Tris–acetate pH 7.0, 0.27 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM sodium β-glycerolphosphate, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol and protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche Biochemicals)]. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation for 15 min at 14 000 g. Supernatants were removed and immediately stored at –80°C until further processing. The lysates of six 9 cm dishes (8000 mg of protein) were diluted to a final volume of 12 ml with MonoQ buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.03% (w/v) Brij-35, 1 mM benzamidine, 0.3 mM sodium orthovanadate and 0.1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol], and applied to a MonoQ HR 5/5 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated in MonoQ buffer. After washing with 15 ml of MonoQ buffer, the column was developed with a 20 ml linear salt gradient to 700 mM NaCl in MonoQ buffer. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, and fractions of 1 ml were collected. Aliquots of 10 µl from each fraction were assayed for in vitro ATF2 kinase activity and western blot analysis.

ATF2 kinase assays

For ATF2 kinase assays, 10 µg of total cell extract prepared in MonoQ lysis buffer as described above, 10 µl of MonoQ fraction or 10 U of recombinant active ERK2 (Calbiochem) were incubated for 30 min at 30°C with 2 µg of purified GST–ATF2-N substrate (van Dam et al., 1995) and 50 µM ATP in a total volume of 60 µl of kinase buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 25 mM MgCl2, 25 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 µM sodium orthovanadate). In all kinase reactions, the NaCl concentration was adjusted to 400 mM. For radioactive quantification, 2 µCi of [γ-32P]ATP was added to the incubation buffer and the reactions were terminated by the addition of 0.5 ml of ice-cold 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 50 mM NaF and 100 µM sodium orthovanadate, after which the GST fusion protein was collected on 20 µl of glutathione–Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). After 1 h tumbling at 4°C, beads were washed twice with lysis buffer. Phosphorylation of GST–ATF2 was analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. 32P incorporation was quantitated using a PhosphorImager and ImageQuant analysis. For analysis of site-specific phosphorylation of the GST–ATF2 substrate, the reactions were terminated by the addition of 20 µl of 4× Laemmli buffer, subsequently analyzed by SDS–PAGE/immunoblotting with phospho-specific ATF2 Thr69 + 71 and ATF2 Thr71 antibody, and quantitated on a LumiImager (Roche).

For immunoprecipitation kinase assays, 9 cm dishes were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS, lysed in 1 ml of RIPA buffer [30 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium fluoride and protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche)], whereafter lysates were cleared by centrifugation (15 min, 14 000 g, 4°C). Cell lysates (750 µg) were incubated overnight with p38, JNK, or ERK antibody coupled to protein A–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia). Collected beads were washed four times with RIPA buffer, and twice with kinase buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 25 mM MgCl2, 25 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 µM sodium orthovanadate). Subsequently, ATF2 N-terminal kinase activity was determined and quantitated using [γ-32P]ATP as described above.

Determination of Ral-GTP

Ral-GTP levels were determined using a Gst-RalBD pull-down assay as described previously (Wolthuis et al., 1998b). Briefly, 9 cm dishes of A14 cells were transiently transfected with 3 µg of HA-Ral. After stimulation, cells were lysed in Ral buffer, and cleared lysates were incubated with 15 µg of GST–RalBD pre-coupled to glutathione beads in order to collect GTP-bound Ral. An aliquot of the total lysate was retained for analysis of protein expression. Samples were resolved on 12.5% polyacrylamide slab gels, transferred to Immobilon (Millipore) and blotted with monoclonal anti-HA antibody.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kanaga Sabapathy and Erwin Wagner for JNK1+2–/– fibroblasts, Boudewijn Burgering and Rob Wolthuis for helpful discussions, Jan Kriek for excellent technical assistance, and Peter van den Broek for carefully reading the manuscript. H.v.D. would like to thank Drs P.Herrlich (Karlsruhe) and A.J.van der Eb (Leiden), in whose laboratories part of this research was initiated. This work was supported by a fellowship of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW to H.v.D.), by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF to J.S.), and by the Radiation Protection, Biomed and TMR Programs of the European Community.

References

- Angel P., Hattori,K., Smeal,T. and Karin,M. (1988) The jun proto-oncogene is positively autoregulated by its product, Jun/AP-1. Cell, 55, 875–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakiri L., Lallemand,D., Bossy-Wetzel,E. and Yaniv,M. (2000) Cell cycle-dependent variations in c-Jun and JunB phosphorylation: a role in the control of cyclin D1 expression. EMBO J., 19, 2056–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Sagi D. and Hall,A. (2000) Ras and Rho GTPases: a family reunion. Cell, 103, 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier F., Lee,R.J., Taylor,A.C., Pestell,R.G. and LuValle,P. (1999) Identification of the cyclin D1 gene as a target of activating transcription factor 2 in chondrocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 1433–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier F., Taylor,A.C. and LuValle,P. (2000) Activating transcription factor 2 is necessary for maximal activity and serum induction of the cyclin A promoter in chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 12948–12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbrook D.M. and Jones,N.C. (1990) Heterodimer formation between CREB and JUN proteins. Oncogene, 5, 295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos J.L. (1998) All in the family? New insights and questions regarding interconnectivity of Ras, Rap1 and Ral. EMBO J., 17, 6776–6782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossy-Wetzel E., Bakiri,L. and Yaniv,M. (1997) Induction of apoptosis by the transcription factor c-Jun. EMBO J., 16, 1695–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgering B.M., Medema,R.H., Maassen,J.A., van de Wetering,M.L., van der Eb,A.J., McCormick,F. and Bos,J.L. (1991) Insulin stimulation of gene expression mediated by p21ras activation. EMBO J., 10, 1103–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L. and Karin,M. (2001) Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature, 410, 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatton B., Bocco,J.L., Goetz,J., Gaire,M., Lutz,Y. and Kedinger,C. (1994) Jun and Fos heterodimerize with ATFa, a member of the ATF/CREB family, and modulate its transcriptional activity. Oncogene, 9, 375–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R.J. (2000) Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell, 103, 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruiter N.D., Wolthuis,R.M., van Dam,H., Burgering,B.M. and Bos,J.L. (2000) Ras-dependent regulation of c-Jun phosphorylation is mediated by the Ral guanine nucleotide exchange factor–Ral pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 8480–8488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devary Y., Gottlieb,R.A., Smeal,T. and Karin,M. (1992) The mammalian ultraviolet response is triggered by activation of Src tyrosine kinases. Cell, 71, 1081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyndam M.C., van Dam,H., van der Eb,A.J. and Zantema,A. (1996) The CR1 and CR3 domains of the adenovirus type 5 E1A proteins can independently mediate activation of ATF-2. J. Virol., 70, 5852–5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyndam M.C., van Dam,H., Smits,P.H., Verlaan,M., van der Eb,A.J. and Zantema,A. (1999) The N-terminal transactivation domain of ATF2 is a target for the co-operative activation of the c-jun promoter by p300 and 12S E1A. Oncogene, 18, 2311–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falvo J.V., Parekh,B.S., Lin,C.H., Fraenkel,E. and Maniatis,T. (2000) Assembly of a functional β interferon enhanceosome is dependent on ATF-2–c-jun heterodimer orientation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 4814–4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs S.Y., Tappin,I. and Ronai,Z. (2000) Stability of the ATF2 transcription factor is regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 12560–12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos K., Morgan,B.A. and Moore,D.D. (1992) Functionally distinct isoforms of the CRE-BP DNA binding protein mediate activity of a T-cell specific enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 747–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goi T., Shipitsin,M., Lu,Z., Foster,D.A., Klinz,S.G. and Feig,L.A. (2000) An EGF receptor/Ral-GTPase signaling cascade regulates c-Src activity and substrate specificity. EMBO J., 19, 623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai T. and Curran,T. (1991) Cross-family dimerization of transcription factors Fos/Jun and ATF/CREB alters DNA binding specificity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 3720–3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham J., Babij,C., Whitfield,J., Pfarr,C.M., Lallemand,D., Yaniv,M. and Rubin,L.L. (1995) A c-Jun dominant negative mutant protects sympathetic neurons against programmed cell death. Neuron, 14, 927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguier S., Baguet,J., Perez,S., van Dam,H. and Castellazzi,M. (1998) Transcription factor ATF2 cooperates with v-Jun to promote growth factor-independent proliferation in vitro and tumor formation in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 7020–7029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivashkiv L.B., Liou,H.C., Kara,C.J., Lamph,W.W., Verma,I.M. and Glimcher,L.H. (1990) mXBP/CRE-BP2 and c-Jun form a complex which binds to the cyclic AMP, but not to the 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate, response element. Mol. Cell. Biol., 10, 1609–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs D., Glossip,D., Xing,H., Muslin,A.J. and Kornfeld,K. (1999) Multiple docking sites on substrate proteins form a modular system that mediates recognition by ERK MAP kinase. Genes Dev., 13, 163–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.S., van Lingen,B., Papaioannou,V.E. and Spiegelman,B.M. (1993) A null mutation at the c-jun locus causes embryonic lethality and retarded cell growth in culture. Genes Dev., 7, 1309–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., Song,J., Eckner,R., Ugai,H., Chiu,R., Taira,K., Shi,Y., Jones,N. and Yokoyama,K.K. (1998) p300 and ATF-2 are components of the DRF complex, which regulates retinoic acid- and E1A-mediated transcription of the c-jun gene in F9 cells. Genes Dev., 12, 233–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., Schiltz,L., Chiu,R., Itakura,K., Taira,K., Nakatani,Y. and Yokoyama,K.K. (2000) ATF-2 has intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity which is modulated by phosphorylation. Nature, 405, 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbus A., Herr,I., Schreiber,M., Debatin,K.M., Wagner,E.F. and Angel,P. (2000) c-Jun-dependent CD95-L expression is a rate-limiting step in the induction of apoptosis by alkylating agents. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis J.M. and Avruch,J. (2001) Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev., 81, 807–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Niculescu H., Bonfoco,E., Kasuya,Y., Claret,F.X., Green,D.R. and Karin,M. (1999) Withdrawal of survival factors results in activation of the JNK pathway in neuronal cells leading to Fas ligand induction and cell death. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 751–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G., Wolfgang,C.D., Chen,B.P., Chen,T.H. and Hai,T. (1996) ATF3 gene. Genomic organization, promoter and regulation. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 1695–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. and Green,M.R. (1990) A specific member of the ATF transcription factor family can mediate transcription activation by the adenovirus E1a protein. Cell, 61, 1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.G., Baskaran,R., Lea-Chou,E.T., Wood,L.D., Chen,Y., Karin,M. and Wang,J.Y. (1996) Three distinct signalling responses by murine fibroblasts to genotoxic stress. Nature, 384, 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone C., Patel,G. and Jones,N. (1995) ATF-2 contains a phosphorylation-dependent transcriptional activation domain. EMBO J., 14, 1785–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa T. et al. (1999) Mouse ATF-2 null mutants display features of a severe type of meconium aspiration syndrome. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 17813–17819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema R.H., Wubbolts,R. and Bos,J.L. (1991) Two dominant inhibitory mutants of p21ras interfere with insulin-induced gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol., 11, 5963–5967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minden A. and Karin,M. (1997) Regulation and function of the JNK subgroup of MAP kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1333, F85–F104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okan E., Drewett,V., Shaw,P.E. and Jones,P. (2001) The small-GTPase RalA activates transcription of the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) gene via an AP1-dependent mechanism. Oncogene, 20, 1816–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouwens D.M., Van der Zon,G.C., Pronk,G.J., Bos,J.L., Moller,W., Cheatham,B., Kahn,C.R. and Maassen,J.A. (1994) A mutant insulin receptor induces formation of a Shc-growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (Grb2) complex and p21ras-GTP without detectable interaction of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) with Grb2. Evidence for IRS1-independent p21ras-GTP formation. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 33116–33122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perini G., Oetjen,E. and Green,M.R. (1999) The hepatitis B pX protein promotes dimerization and DNA binding of cellular basic region/leucine zipper proteins by targeting the conserved basic region. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 13970–13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radler-Pohl A., Sachsenmaier,C., Gebel,S., Auer,H.P., Bruder,J.T., Rapp,U., Angel,P., Rahmsdorf,H.J. and Herrlich,P. (1993) UV-induced activation of AP-1 involves obligatory extranuclear steps including Raf-1 kinase. EMBO J., 12, 1005–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimold A.M. et al. (1996) Chondrodysplasia and neurological abnormalities in ATF-2-deficient mice. Nature, 379, 262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuther G.W. and Der,C.J. (2000) The Ras branch of small GTPases: Ras family members don’t fall far from the tree. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronai Z., Yang,Y.M., Fuchs,S.Y., Adler,V., Sardana,M. and Herlyn,M. (1998) ATF2 confers radiation resistance to human melanoma cells. Oncogene, 16, 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse J., Cohen,P., Trigon,S., Morange,M., Alonso-Llamazares,A., Zamanillo,D., Hunt,T. and Nebreda,A.R. (1994) A novel kinase cascade triggered by stress and heat shock that stimulates MAPKAP kinase-2 and phosphorylation of the small heat shock proteins. Cell, 78, 1027–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez I., Hughes,R.T., Mayer,B.J., Yee,K., Woodgett,J.R., Avruch,J., Kyriakis,J.M. and Zon,L.I. (1994) Role of SAPK/ERK kinase-1 in the stress-activated pathway regulating transcription factor c-Jun. Nature, 372, 794–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber M., Kolbus,A., Piu,F., Szabowski,A., Mohle-Steinlein,U., Tian,J., Karin,M., Angel,P. and Wagner,E.F. (1999) Control of cell cycle progression by c-Jun is p53 dependent. Genes Dev., 13, 607–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulian E. and Karin,M. (2001) AP-1 in cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene, 20, 2390–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M., Nomura,Y., Suzuki,H., Ichikawa,E., Takeuchi,A., Suzuki,M., Nakamura,T., Nakajima,T. and Oda,K. (1998) Activation of the rat cyclin A promoter by ATF2 and Jun family members and its suppression by ATF4. Exp. Cell Res., 239, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanoue T., Maeda,R., Adachi,M. and Nishida,E. (2001) Identification of a docking groove on ERK and p38 MAP kinases that regulates the specificity of docking interactions. EMBO J., 20, 466–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam H. and Castellazzi,M. (2001) Distinct roles of Jun:Fos and Jun:ATF dimers in oncogenesis. Oncogene, 20, 2453–2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam H., Duyndam,M., Rottier,R., Bosch,A., Vries-Smits,L., Herrlich,P., Zantema,A., Angel,P. and van der Eb,A.J. (1993) Heterodimer formation of cJun and ATF-2 is responsible for induction of c-jun by the 243 amino acid adenovirus E1A protein. EMBO J., 12, 479–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam H., Wilhelm,D., Herr,I., Steffen,A., Herrlich,P. and Angel,P. (1995) ATF-2 is preferentially activated by stress-activated protein kinases to mediate c-jun induction in response to genotoxic agents. EMBO J., 14, 1798–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam H., Huguier,S., Kooistra,K., Baguet,J., Vial,E., van der Eb,A.J., Herrlich,P., Angel,P. and Castellazzi,M. (1998) Autocrine growth and anchorage independence: two complementing Jun-controlled genetic programs of cellular transformation. Genes Dev., 12, 1227–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheij M. et al. (1996) Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature, 380, 75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheijen M.H., Wolthuis,R.M., Defize,L.H., den Hertog,J. and Bos,J.L. (1999) Interdependent action of RalGEF and Erk in Ras-induced primitive endoderm differentiation of F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. Oncogene, 18, 4435–4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virbasius C.M., Wagner,S. and Green,M.R. (1999) A human nuclear-localized chaperone that regulates dimerization, DNA binding and transcriptional activity of bZIP proteins. Mol. Cell, 4, 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waas W.F., Lo,H.H. and Dalby,K.N. (2001) The kinetic mechanism of the dual phosphorylation of the ATF2 transcription factor by p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase α. Implications for signal/response profiles of MAP kinase pathways. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 5676–5684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom R., Johnson,R.S. and Moore,C. (1999) c-Jun regulates cell cycle progression and apoptosis by distinct mechanisms. EMBO J., 18, 188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolthuis R.M. and Bos,J.L. (1999) Ras caught in another affair: the exchange factors for Ral. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 9, 112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolthuis R.M., de Ruiter,N.D., Cool,R.H. and Bos,J.L. (1997) Stimulation of gene induction and cell growth by the Ras effector Rlf. EMBO J., 16, 6748–6761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolthuis R.M., Zwartkruis,F., Moen,T.C. and Bos,J.L. (1998a) Ras-dependent activation of the small GTPase Ral. Curr. Biol., 8, 471–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolthuis R.M., Franke,B., van Triest,M., Bauer,B., Cool,R.H., Camonis,J.H., Akkerman,J.W. and Bos,J.L. (1998b) Activation of the small GTPase Ral in platelets. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 2486–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]