Abstract

The gene cyaB1 from the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 codes for a protein consisting of two N-terminal GAF domains (GAF-A and GAF-B), a PAS domain and a class III adenylyl cyclase catalytic domain. The catalytic domain is active as a homodimer, as demonstrated by reconstitution from complementary inactive point mutants. The specific activity of the holoenyzme increased exponentially with time because the product cAMP activated dose dependently and nucleotide specifically (half-maximally at 1 µM), identifying cAMP as a novel GAF domain ligand. Using point mutants of either the GAF-A or GAF-B domain revealed that cAMP activated via the GAF-B domain. We replaced the cyanobacterial GAF domain ensemble in cyaB1 with the tandem GAF-A/GAF-B assemblage from the rat cGMP-stimulated phosphodiesterase type 2, and converted cyaB1 to a cGMP-stimulated adenylyl cyclase. This demonstrated the functional conservation of the GAF domain ensemble since the divergence of bacterial and eukaryotic lineages >2 billion years ago. In cyanobacteria, cyaB1 may act as a cAMP switch to stabilize committed developmental decisions.

Keywords: adenylyl cyclases/Anabaena/evolution/GAF domain/PAS domain

Introduction

Essentially all cells generate cAMP in response to extracellular stimuli by intracellular adenylyl cyclases (ACs). As far as mammalian ACs (all class III ACs) are concerned, our state of knowledge is considerable (for reviews, see Sunahara et al., 1996; Hanoune et al., 1997; Smit and Iyengar, 1998). In bacteria, on the other hand, few biochemical details are known, although the cAMP-controlled catabolite repression in Escherichia coli (harbouring a class I AC) has been studied extensively for decades (Peterkofsky et al., 1993; Amin and Peterkofsky, 1995). Many bacteria contain class III ACs, which possess catalytic domains with pronounced sequence similarities to their mammalian relatives (Barzu and Danchin, 1994; McCue et al., 2000). The catalytic domains of bacterial class III ACs are mostly combined with non-catalytic domains, whose likely physiological role is to exert regulatory, i.e. stimulatory or inhibitory, effects (Coudart-Cavalli et al., 1997; Katayama and Ohmori, 1997; Kasahara and Ohmori, 1999; McCue et al., 2000).

The cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 has six genes coding for differently modularized AC isozymes (Katayama and Ohmori, 1997; Kasahara et al., 2001). The gene for cyaB1 codes for an AC, which at its N-terminal end has two GAF domains in tandem and a single PAS domain followed by an AC catalyst (Katayama and Ohmori, 1997; Ho et al., 2000) (see scheme in Figure 1A). GAF domains [found in cGMP-phosphodiesterases, adenylyl cyclases and FhlA (formate hydrogen lyase transcriptional activator)] and PAS domains (found in period clock protein, aryl hydrocarbon receptor and single-minded protein) are ubiquitous small-molecule-binding domains present in signal transduction proteins in organisms from all phyla (Aravind and Ponting, 1997; Ho et al., 2000; Anantharaman et al., 2001). GAF domains, which have been identified in >1100 proteins, have been studied mostly in conjunction with the regulation of mammalian cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs; McAllister-Lucas et al., 1993, 1995; Soderling and Beavo, 2000). Five of the 11 mammalian PDE gene families contain GAF domains (PDE2, -5, -6, -10 and -11). PDE2, -5 and -6 possess two N-terminal GAF domains in tandem (termed GAF-A and GAF-B), which specifically bind cGMP, resulting in regulation of cAMP and cGMP hydrolysis (Soderling and Beavo, 2000). A number of mutational and recent structural and modelling studies attempted to pinpoint amino acids that are involved in nucleotide specification and cGMP binding (McAllister-Lucas et al., 1995; Turko et al., 1996; Granovsky et al., 1998; Ho et al., 2000; S.F.Martinez, A.Y.Wu, N.A.Glavas, X.B.Tang, S.Turley, W.G.J.Hol, J.A.Beavo, submitted for publication).

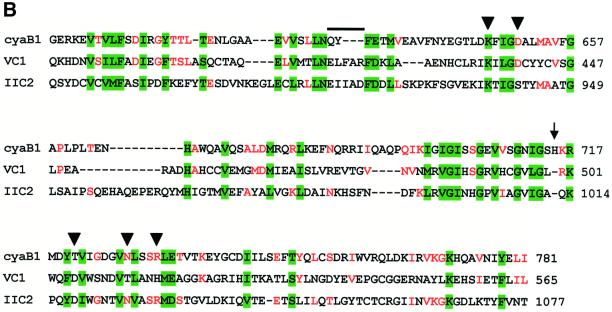

Fig. 1. (A) Scheme of the modular architecture of the cyanobacterial AC cyaB1. The domain abbreviations and approximate amino acid boundaries for each segment are indicated. (B) Sequence alignment of the catalytic domains of cyaB1 with C1a from canine type V (VC1) and C2 from rat type II (IIC2) ACs. The arrowheads mark the individually mutated amino acids (to alanine), which are involved in coordination of a divalent metal cation (D650), transition state stabilization (N728, R732) and substrate definition (K646 and T721); the latter replaces a canonical D in the catalytic fold of mammalian ACs. Residues conserved in all three sequences are shaded green. Residues conserved between cyaB1 and only one of the mammalian domains are red. The top line and the arrow mark a sequence gap and a single amino acid insertion, respectively, which are characteristic for this subfamily of class III ACs. The selection of the mammalian domains was based on the available X-ray structure of this heterodimer (Tesmer et al., 1997). (C) Sequence alignment of cyaB1 GAF-A and GAF-B domains with their congeners from rat phosphodiesterase 2 and the yeast YKG9 GAF protein. Yellow columns denote residues in the NKXnFX3DE motif, which is conserved in the cyanobacterial and mammalian sequences. The site of individual point mutations (D190A in GAF-A, D360A in GAF-B) is indicated by an arrow. Residues conserved in at least four out of five sequences are red. The arrowheads pinpoint the amino acids assumed to define purine specificity (S.F.Martinez, A.Y.Wu, N.A.Glavas, X.B.Tang, S.Turley, W.G.J.Hol, J.A.Beavo, submitted for publication).

In the cyanobacterial AC cyaB1, the GAF domains formally fulfil the sequence requirements for cGMP binding. In bacteria, however, the presence of guanylyl cyclases has never been shown beyond a reasonable doubt and, therefore, remains contentious. In the present study, we sought to clarify the function of the GAF domains present in cyaB1. Expressing the presumed catalytic centre, we established that cyaB1 AC activity was dependent on homodimerization. The GAF domains in the cyaB1 holoenzyme operate as a high-affinity cAMP sensor and convey to the cyaB1 AC the properties of a cAMP-specific, self-activating device, a cAMP switch. Finally, a replacement of the cyanobacterial GAF domain set with that from rat PDE2 generated a cGMP-activated AC and established a functional conservation of this small-molecule-binding domain over >2 billion years of evolution.

Results

Analysis and biochemical characterization of the Anabaena cyaB1 AC catalytic domain

The Anabaena cyaB1 gene codes for a protein with two tandem GAF, a single PAS domain and a predicted AC catalytic region (Figure 1A) (Katayama and Ohmori, 1997; Ho et al., 2000). An alignment of the catalytic domain with the corresponding canine AC type VC1a and rat AC type IIC2 domains showed considerable similarities, justifying a class III classification (Figure 1B; Katayama and Ohmori, 1997). However, the replacement of a canonical aspartate (D1018 in AC-IIC2) by a threonine (T721 in cyaB1) may constitute a decisive difference because this residue was shown to be essential for substrate definition, and its mutation rendered the protein inactive (Tang et al., 1995; Guo et al., 2001). Yet, a threonine at this position is also present in other bacterial ACs, e.g. in Stigmatella aurantiaca and in four of 15 mycobacterial ACs (Coudart-Cavalli et al., 1997; McCue et al., 2000). A refined sequence analysis revealed that all open reading frames for predicted bacterial ACs, which have a threonine at this position, display a conserved pattern of changes: they contain a three amino acid gap in a highly conserved (F/Y)X2(F/Y)D motif in C1a (marked by an overline in Figure 1B) and an insertion of a single variable amino acid in an otherwise invariant block in the mammalian C1a domains (arrow in Figure 1B). These critical length changes must be structurally compensated for in the folded protein to properly position the canonical amino acids in the dimeric catalytic cleft (Tesmer et al., 1999), either to enable the known catalytic mechanism or to allow the cyclization to proceed via a different mechanism. Therefore, we expressed the catalytic domain of cyaB1 (cyaB1595–781) starting 11 amino acids prior to D606, which, according to the structure of the catalytic fold of mammalian ACs (Tesmer et al., 1997, 1999; Zhang et al., 1997), is essential for coordination of the metal cofactor. The recombinant cyaB1595–781 protein was invariably obtained in inclusion bodies, therefore we attempted to express cyaB1595–859, i.e. including the C-terminus which was identified to have some similarity to a tetratricopeptide unit (TPR; amino acids 795–828) (analysed by the Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool, SMART; Schultz et al., 1998). This construct was expressed as a partly soluble protein (∼50%) and purified to homogeneity by Ni-NTA chromatography (Figure 2).

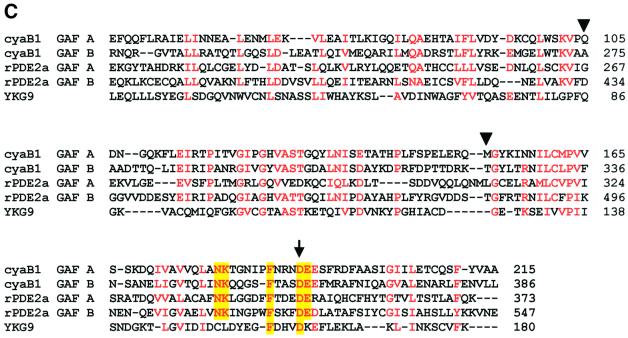

Fig. 2. Purification and activity of recombinant cyanobacterial AC proteins (SDS–PAGE analysis, Coomassie Blue staining). Two micrograms of each protein were applied, and molecular mass standards (in kDa) are indicated on the left. The specific AC activities indicated underneath were determined with 132 nM cyaB1595–859, 265 nM K646A, 132 nM T721A, 3.3 µM D650A, 0.66 µM N728A and 248 nM R732A, and Mn-ATP as a substrate. The holoenzyme (right lane) was assayed at 5.2 nM protein, with Mg-ATP as a substrate in the presence of 100 µM cAMP as an activator.

The kinetic properties of cyaB1595–859 were assayed with Mn2+ or Mg2+ as divalent metal ions. The KM values for ATP, determined at 45°C and pH 8.5, were 11 ± 2 and 334 ± 18 µM, and the Vmax values were 309 ± 18 and 655 ± 38 nmol cAMP/mg/min for Mn2+ and Mg2+, respectively. The preference for Mg2+ with respect to Vmax was unusual because, in most class III ACs, Mg2+-supported activity is rather low (Kasahara et al., 1997; Hurley, 1999). The pH optimum was 8.5 (tested pH range 5.0–10), the temperature optimum an unusual 47°C and the activation energy derived from the linear arm of an Arrhenius plot was 96 kJ/mol (tested range 0–66°C). The Hill coefficient of 1.0 indicated no cooperativity of the two potential catalytic sites, which are probably formed by the symmetric homodimeric AC (Tang and Hurley, 1998; Guo et al., 2001).

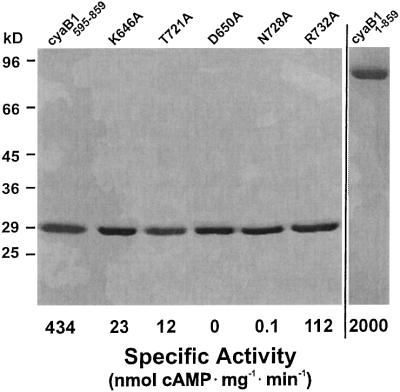

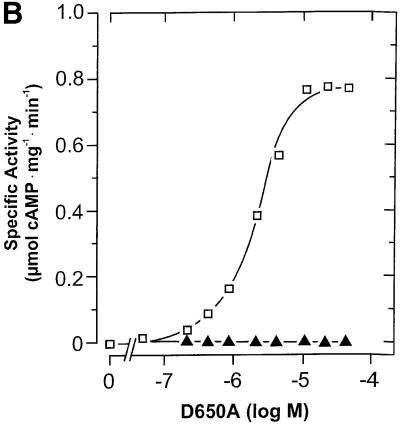

The time dependence of cyaB1595–859 was linear, yet the protein dependence was not. From 17 to 661 nM protein, the specific activity increased 8-fold, suggesting that a protein–protein interaction was involved in the formation of the catalytic site (Figure 3A). To prove the necessity for dimerization, we constructed two mutant proteins (cyaB1595–859D650A and cyaB1595–859N728A), which should be enzymatically inactive, yet complementary (Guo et al., 2001). According to the known structure of the mammalian AC catalytic fold, D650 is involved in metal coordination and ATP positioning, and N728 in stabilizing a transition state (Tesmer et al., 1997; Yan et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1997). Both mutants were expressed and purified (Figure 2). Incubated individually, they were essentially inactive (<1% of wild type). Next we titrated 47 nM cyaB1595–859N728A, functionally equivalent to a mammalian C2a AC domain, with cyaB1595–859D650A, equivalent to a C1a domain (Figure 3B). AC activity was restored to a large extent, demonstrating that dimerization is required and sufficient for cyaB1595–859 activity, thus explaining the non-linear protein dependency (Figure 3A). In cyaB1 AC, a threonine is at a position of a critical aspartate, which is involved in substrate definition by making a hydrogen bond to the N6 of the ATP (Tesmer et al., 1999). We asked whether T721 could functionally replace this aspartate and generated a T721A mutant (Figure 2). cyaB1595–859T721A had only 3% of wild-type AC activity, demonstrating that T721 participated in catalysis. Furthermore, T721 did not relax the substrate specificity for ATP because GTP was not accepted as a substrate.

Fig. 3. (A) Protein dependence of the specific activities of the cyanobacterial AC595–859 catalyst (triangles; assayed at pH 8.5 and 45°C) and the holoenzyme (assayed at pH 7.5 and 37°C) with and without the addition of 100 µM cAMP (open and filled squares, respectively). cAMP addition did not affect the activity of AC595–859. (B) Reconstitution of AC activity from the inactive AC595–859D650A and AC595–859N728A mutants. N728A (47 nM) was reconstituted with increasing amounts of AC595–859D650A (open squares) and AC595–859D650A alone (triangles).

To ascertain that the catalytic centre of cyaB1 was otherwise in agreement with a canonical class III catalytic cleft, we generated the cyaB1595–859K646A (substrate definition) and cyaB1595–859R732A (transition state stabilization) mutant proteins (Figure 2). cyaB1595–859K646A had 5% and cyaB1595–859R732A had ∼25% residual AC activity relative to the wild-type enzyme. The latter result was in agreement with the observation that mutation of this critical arginine residue did not result in a full ablation of enzyme acitivity (Tang et al., 1995; Yan et al., 1997; Guo et al., 2001). Because of the residual activity of these equivalents of a mammalian AC C2 domain, they could not be used for titration and complementation (see above).

cAMP activates cyaB1 AC via its GAF domains

The catalytic domain of cyaB1 AC carries two tandem GAF domains (GAF-A and GAF-B; Figure 1A) at its N-terminal end. An alignment with those from rat PDE2 shows prominent sequence conservation (Figure 1C). The cyanobacterial and rat GAF-A domains are 27% identical and 35% similar, and the GAF-B domains show 40% identity and 48% similarity, respectively. A noteworthy feature is the conservation of an NKXnFX 3DE motif in the rat and cyanobacterial GAF-A and -B domains (Figure 1C; Turko et al., 1996). It was suggested that this motif is involved in cGMP binding because point mutations of the aspartate abolish cGMP binding to the respective GAF domains in PDE5 (McAllister-Lucas et al., 1995). It is interesting that a recently crystallized putative yeast GAF domain, YKG9, lacks this conserved motif and does not bind cGMP (Ho et al., 2000).

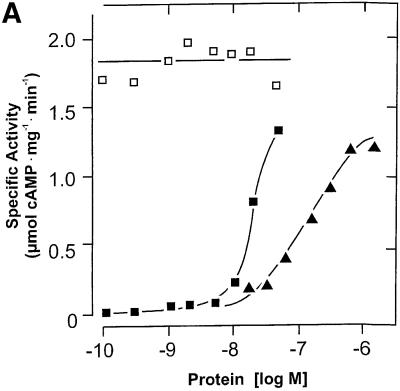

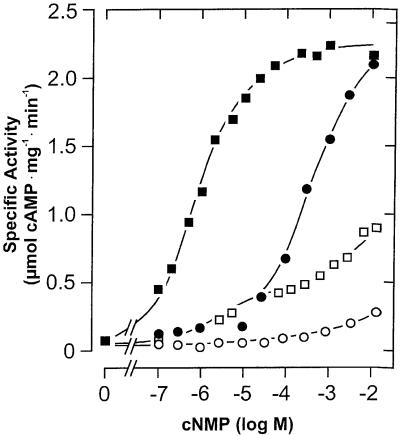

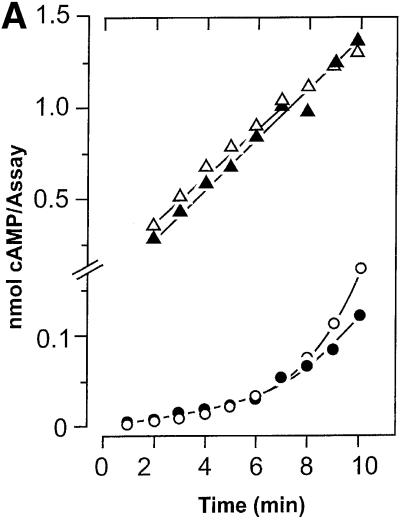

We expressed the cyaB1 AC holoenzyme (cyaB11–859) in E.coli. Although >80% of the recombinant protein was in inclusion bodies, enough was soluble for purification and characterization (Figure 2). The pH optimum was 7.5 (tested range 5.0–9.5), the temperature optimum was 40°C (tested range 0–66°C) and the activation energy derived from an Arrhenius plot was 65 kJ/mol. As observed with cyaB1595–859, Hill constants with a value of 1 indicated no cooperativity, and Mg2+ supported AC activity of the holoenzyme better than did Mn2+ (Table I). The values of the Vmax/Michaelis constant were almost identical for Mg2+- and Mn2+-supported activity, indicating concerted changes in both constants (Table I). The protein dependence of cyaB1 was non-linear and the specific activity increased with the protein concentration, reminiscent of the observations with cyaB1595–859 (Figure 3A). However, the protein dependence of the holoenzyme may also be explained via a stimulation by cAMP formed during the assay. The cAMP concentrations at the end of the assays were 6.4 and 26.3 µM at 20 and 50 nM cyaB1 (see below; Figure 5). When we examined the linearity of the enzymatic reaction over time, we observed an enhancement of cAMP biosynthesis irrespective of whether Mg2+ or Mn2+ was used as a divalent cation (Figure 4A). Calculating the specific AC activity at 1 min intervals, we noticed that, strikingly, it increased exponentially (Figure 4B). Because we were handling a recombinant, purified AC protein, we excluded the presence of activating protein factors and reasoned that the enzyme may be activated directly by the increasing cAMP product concentration, e.g. with Mg2+ as a cation the cAMP concentration in the assay increased from 0 to 1.2 µM over 10 min (Figure 4A). The addition of 100 µM cAMP to the assay linearized the time course and, surprisingly, the protein dependency over the concentration range, which was testable experimentally (Figure 3A). The determination of the Hill coefficients demonstrated no cooperativity (Hill constants were close to 1) and the KM values with Mg2+ and Mn2+ in the presence of 100 µM cAMP remained essentially unchanged, yet Vmax increased ∼25-fold (Table I). Next, we examined the potency and nucleotide specificity of the activation (Figure 5). With Mg2+ as a cation, the dose–response curves for cAMP and cGMP yielded EC50 values of 1 and 300 µM, respectively. Using Mn2+ as a divalent cation, the cAMP dose–response curve had a hump at ∼100 µM cAMP and thus appeared biphasic, whereas with cGMP almost no stimulation of AC activity was observed (Figure 5). The stimulation by cAMP was highly specific, because adenosine, inosine, hypoxanthine, AMP, 2′-deoxy-3′-AMP, ADP, GMP, 2′-GMP, 2′,3′-cGMP and GMPPNP (tested range 100 µM–1 mM) did not enhance cyaB1 AC activity. A look at the dose– response curve for cAMP confirmed that the increase in the rate of cAMP biosynthesis over time was in full agreement with the concomitant increase in cAMP (0–1.2 µM). This corroborated the conclusion that the reaction product cAMP was an autoactivator.

Table I. Kinetic characterization of cyaB11–859 AC.

| KM(ATP) (µM) | Vmax (nmol/mg/min) | Vmax/KM | Hill coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mM Mg2+ | 38 ± 1 | 84 ± 8 | 2.2 | 1.0 |

| 2 mM Mn2+ | 11 ± 0.3 | 24 ± 1 | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| 10 mM Mg2+ + 100 µM cAMP | 24 ± 1 | 2244 ± 201 | 94 | 1.1 |

| 2 mM Mn2+ + 100 µM cAMP | 4 ± 0.2 | 479 ± 5 | 120 | 1.0 |

With Mg2+ as a cation, the protein concentration used was 5.2 nM, and with Mn2+ it was 15 and 5.2 nM in the absence and presence of cAMP, respectively. Assays were carried out at 37°C and pH 7.5.

Fig. 5. Dose–response curve of cAMP- and cGMP-stimulated cyaB1. Closed symbols indicate measurements with Mg2+ and open symbols measurements with Mn2+ as a divalent metal cation. cAMP, squares; cGMP, circles.

Fig. 4. (A) Time dependence of the cyaB1 AC activity (cyaB11–859 holoenzyme) assayed with Mg2+ (filled symbols) or Mn2+ (open symbols) as divalent metal cations. Note the time-dependent increase in cAMP formation in the absence of externally added cAMP (circles) and the linear time dependence in the presence of 100 µM cAMP (triangles). The protein concentrations in the assays with Mg2+ and Mn2+ were 7.6 and 102 nM, respectively, to account for different activities and to attain comparable conversion rates. (B) Changes in the specific activity of cyaB1 over time. The specific activity at each time point in (A) was calculated for 1 min intervals. Note the exponential increase in specific AC activities without the addition of cAMP and the constant specific activity in the presence of 100 µM cAMP [symbols are as in (A)].

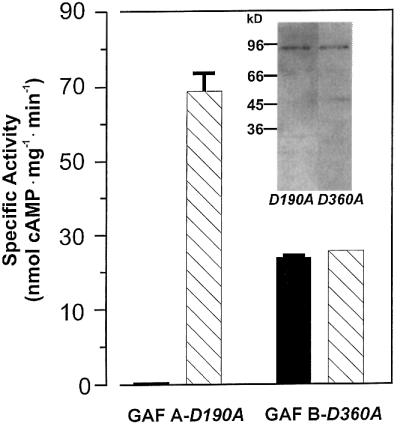

We attributed the activating effect of cAMP to an interaction with the GAF domains and investigated whether cAMP activated via the GAF-A or GAF-B domain. Mutational and modelling studies suggested that the aspartate residue in the NKXnFX3DE motif may be involved in cGMP binding (McAllister-Lucas et al., 1995; Turko et al., 1996; Ho et al., 2000). This motif is conserved in both cyanobacterial GAF domains (Figure 1C). Considering the cAMP preference, this suggestion may not be sustainable as far as cyclic nucleotide specificity is concerned. One may, however, infer that the aspartate of this motif is either involved in cyclic nucleotide binding in an as yet unknown manner or that its mutation may result in a local conformational deterioration, which affects ligand binding of the affected GAF domain (McAllister-Lucas et al., 1995; Turko et al., 1996). Therefore, we took those data as an experimental opportunity and mutated the corresponding aspartate residues in the cyanobacterial GAF-A and GAF-B domains to alanine, generating cyaB1D190A and cyaB1D360A (marked by the arrow in Figure 1C). Both constructs were poorly expressed, with most of the protein ending up in inclusion bodies. The soluble portion of the recombinant proteins was purified by Ni-NTA chromatography. We could not stain a protein on an SDS– polyacrylamide gel, yet a western blot confirmed expression and purification (Figure 6). In cyaB1D190A (GAF-A mutation), basal activity was almost undetectable, whereas 100 µM cAMP activation was comparable to the unmutated cyaB1. The low basal activity in this instance may be the result of the low enzyme concentration available to us because of poor expression. In contrast, cyaB1D360A (GAF-B mutation) had a basal activity like cyaB1 wild type and cAMP addition was without effect. This indicated that the stimulatory effect of cAMP is exerted via the GAF-B domain.

Fig. 6. cAMP activation of cyaB1 is mediated through the GAF-B domain, as demonstrated by GAF-inactivating mutations of Asp190 and Asp360 (D190A and D360A) in GAF-A and GAF-B domains, respectively. The assays were carried out with 83 and 25 nM protein for GAF-AD190A and GAF-BD360A, respectively, and 75 µM Mg2+-ATP at pH 7.5, 37°C ± 100 µM cAMP as an activator. The insert shows a western blot of the purified proteins.

This was further substantiated with cAMP-binding studies using 0.5–10 µM cAMP in a binding assay employed earlier (McAllister-Lucas et al., 1995; Ho et al., 2000). cyaB1 bound cAMP in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas cyaB1D360A maximally bound 3% of cAMP when comparing all corresponding data points with the unmutated protein, i.e. cyaB1D360A had lost essentially all cAMP-binding capacity. These studies also unequivocally demonstrated that, in cyaB1, GAF-A did not bind cAMP because GAF-A was unaffected in the cyaB1D360A mutant. It cannot yet be decided whether the loss of cAMP binding was due to an inaccessibility or destruction of the cAMP-binding pocket or to changes in the kon or koff rates. Irrespective of this, both loss of cAMP stimulation and cAMP binding by the cyaB1D360A mutation exclusively implicated the GAF-B site as responsible for the cAMP effect.

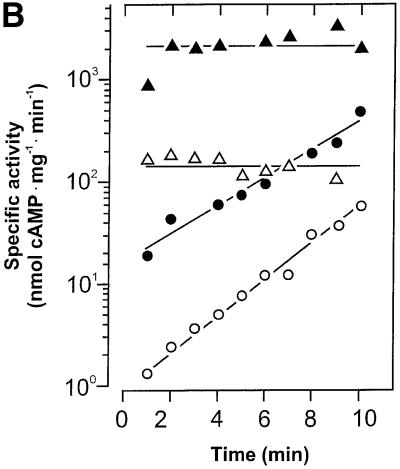

Conversion of cyaB1 to a cGMP-activated AC by GAF domain replacement

Although GAF domains occur in proteins from all phyla, a direct involvement in enzyme regulation has only been demonstrated for FhlA and several mammalian PDEs (Hopper and Böck, 1995; Turko et al., 1999; Ho et al., 2000). In the latter, cGMP specifically binds and regulates cAMP and cGMP PDEs. The tandem arrangement of the GAF domains in mammalian PDE2, -5, -6 and -10 is identical to that in cyaB1. Cyanobacteria and mammals are about as distant in evolutionary terms as possible, therefore it was particularly interesting whether the GAF domains are sufficiently conserved to be interchangeable. We replaced the GAF domain ensemble in cyaB1 with the tandem GAF arrangement present in the rat PDE2. We used the GAF domain region from rat PDE2 because it is the only isoform, which has been demonstrated unequivocally to be directly activated by cGMP binding to the GAF domains, and because the structure of the tandem GAF domains of the mouse PDE2 has been elucidated most recently (S.F.Martinez, A.Y.Wu, N.A.Glavas, X.B.Tang, S.Turley, W.G.J.Hol, J.A.Beavo, submitted for publication; mouse and rat PDE2 GAF domains are virtually identical). The chimeric rat–cyanobacterial protein cyaB1rat-GAF was expressed in E.coli and affinity purified on Ni-NTA (Figure 7). Basal AC activity of the recombinant rat–Anabaena protein chimera was 2.4 nmol cAMP/mg/min. Addition of cGMP dose dependently activated the cyaB1 AC (Figure 7). Thus, we generated a cGMP-activated cyaB1 AC and demonstrated that the GAF domains were truly exchangeable. The EC50 for cGMP of 3 µM corresponded precisely to that reported for cGMP stimulation of PDE2 activity (Sonnenburg et al., 1991). cAMP, on the other hand, did not stimulate the cyaB1 any longer. In view of the huge evolutionary distance between cyanobacteria and mammals, the observed decrease in specific activity of cyaB1rat-GAF compared with that of cyaB1 may be rationalized in terms of the fact that the substitution boundaries were not optimally placed and/or that the intramolecular signal transduction to the catalytic domain was relaxed.

Fig. 7. Dose–response curve of cGMP- and cAMP-stimulated cyanobacterial AC activity, which contains the tandem GAF assembly from rat PDE2. The insert shows a western blot of the purified protein (100 ng applied/lane). cAMP, squares; cGMP, circles.

Discussion

A new arrangement of the catalytic fold in the cyaB1 AC

The catalytic centre of class III ACs is usually formed by two similarly folded protein domains, which donate amino acids to a 2-fold symmetric catalytic cleft (Tang and Gilman, 1995; Yan et al., 1996, 1997). In agreement with mutational studies, the 2.8 Å AC structure identified the amino acids involved in catalysis (Tesmer et al., 1997, 1999; Zhang et al., 1997). In the cyaB1 AC, a threonine (T721) replaces a highly conserved aspartate, which in mammalian ACs serves as a hydrogen acceptor towards the N6 atom of the adenine moiety of ATP and is indispensible for activity, as shown by alanine replacement (Tang et al., 1995; Tesmer et al., 1997; Sunahara et al., 1998). Our data suggest that threonine functionally replaces aspartate, because in a cyaB1T721A mutant, AC activity was reduced by >95%. Most likely, T721 functions as a hydrogen acceptor as a result of subtle changes in the fine structure of the purin-binding pocket caused by peculiar cyaB1 sequence features, such as a single amino acid insertion (position 715) in an otherwise length-invariant segment. This interpretation is supported by the fact that cyaB1T721A was a Vmax mutant (KM was unchanged; data not shown). This indicates that the amino acid at position T721 is less important for substrate docking and probably more involved in the correct orientation of the substrate towards the transition state. Substrate specificity in cyaB1 would then mainly rely on lysine 646 (supported by the finding that K646A or K646E mutants were KM and Vmax mutants; data not shown). It is noteworthy that a guanylyl cyclase from Paramecium, with a mammalian AC topology, has a serine at the position corresponding to T721. In this instance, the serine most likely serves as a hydrogen donor toward the O6 of the guanine moiety, whereas GTP substrate specification is achieved by a glutamate located at the position of K646 in cyaB1 (Linder et al., 2000).

cAMP activates cyaB1 via its GAF domains

GAF domains were identified in a formate-activated transcription factor in E.coli and in mammalian PDEs (Hopper and Böck, 1995; Aravind and Ponting, 1997). In the latter, they are involved in regulation of PDE activity and serve as cGMP receptor domains (Sonnenburg et al., 1991; McAllister-Lucas et al., 1993; Soderling and Beavo, 2000). Using bioinformatics, GAF domains have now been detected in >1100 proteins from all kingdoms of life and are expected to serve as receptors for a variety of as yet unidentified small molecules (Aravind and Ponting, 1997; Anantharaman et al., 2001). Our data establish cAMP as a new ligand and define GAF domains as a novel cAMP receptor in the terminology used to describe cGMP receptors (Ho et al., 2000). The differences in the Vmax values of cyaB1 in the absence and presence of the activator cAMP, and the uniform increase in the quotient of Vmax/KM (Table I), would argue that cAMP binding to the GAF-B domain has a direct bearing on the catalytic site. The nature of this coupling is a pressing question that awaits investigation.

Based on mutational (GAF domains of PDE5) and structural efforts (YKG9), the cGMP binding to PDE GAF domains was modelled to involve the NKXnFX3DE motif (McAllister-Lucas et al., 1995; Turko et al., 1996; Granovsky et al., 1998; Ho et al., 2000). A most recent X-ray structure of the PDE2 GAF domains shows that none of the amino acids of this motif makes contact with cGMP (S.F.Martinez, A.Y.Wu, N.A.Glavas, X.B.Tang, S.Turley, W.G.J.Hol, J.A.Beavo, submitted for publication). In the novel structure, cGMP specificity is based on hydrogen bonds established by an aspartate not previously implicated in ligand binding (to the protonated N1 via the carboxyl and to O6 via the backbone amide) and a threonine (D434 and T483 in the rat GAF-B domain, marked by arrowheads in Figure 1C). In the cyanobacterial GAF-B domain, the threonine is conserved (T323), whereas an alanine (A275) takes the position of the aspartate (Figure 1C). An attempt to change the cyclic nucleotide specificity of the cyaB1 GAF-B domain from cAMP to cGMP in a cyaB1A275D mutant did not materialize (data not shown). This was not completely unexpected because the conserved threonine, which forms a hydrogen bond with the N2-amino group of cGMP in PDE2-GAF-B, cannot similarly connect to cAMP as it does not have an N2-amino group. Therefore, different binding modes for cyclic nucleotides are likely to exist in the rat and cyanobacterial GAF-B domains.

This is the second instance in this study where we cannot entirely reconcile excellent high resolution X-ray structures with our experimental data. We believe that the X-ray structures applicable to this work, the mammalian class III AC catalyst (Tesmer et al., 1997, 1999; Zhang et al., 1997) and the GAF domains of PDE2 (S.F.Martinez, A.Y.Wu, N.A.Glavas, X.B.Tang, S.Turley, W.G.J.Hol, J.A.Beavo, submitted for publication), describe the overall domain conformation of the cyaB1 catalyst and GAF domain ensemble adequately, albeit in a frozen state. Our observations underline the fact that rigid structures often cannot be extended unmodified to the flexible fine structure of a small-molecule-binding site, such as a substrate- or ligand-binding site, which actually may be akin to a fingerprint of a particular protein.

cyaB1 distinctly prefers Mg2+ over Mn2+ as a metal cofactor for catalysis, in contrast to most other ACs, yet the almost identical ratios of Vmax/KM for Mg2+- and Mn2+-supported activities indicate an equal catalytic efficiency. Interestingly, with Mn2+ as a divalent cation, the cAMP activation dose–response curve is biphasic. This suggests that with Mn2+, cAMP may bind at two different sites, a low- and a high-affinity site, whereas with Mg2+, only a single high-affinity site seems to be occupied. Conceivably, a divalent cation may enhance or even be required for cAMP binding to the GAF-B domain in addition to its function in the cyclization reaction. Mg2+ and Mn2+ may serve differently in these roles.

Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 has at least six genes coding for functional ACs (Katayama and Ohmori, 1997; Kasahara et al., 2001). For the maintenance of intracellular cAMP levels, the most relevant AC isoform seems to be cyaC, which consists of a response regulator, a histidine kinase, a second response regulator and a single catalytic domain (Katayama and Ohmori, 1997). What then are the possible physiological functions of the self-activating cyaB1 AC? Looking at the multiple differentiation potentials of Anabaena, there seems to be room for all AC isoforms, as they considerably expand the regulatory possibilities. As a filamentous bacterium, Anabaena assimilates carbon dioxide. Under light, yet without fixed nitrogen, it terminally differentiates about every tenth cell into a heterocyst, which provides an environment for oxygen-sensitive nitrogen assimilation (Adams and Duggan, 1999; Wolk, 2000). In addition, proheterocysts are formed, which, contrary to heterocysts, can dedifferentiate when necessary. Furthermore, akinetes (spore-like cells) are developed that survive dry periods, and hormogonia exist, which are short mobile filaments used for dispersal. These multiple possibilities for differentiation in response to environmental conditions certainly involve intra- and intercellular signalling processes at many levels. In such a scenario, a role for an autoactivating AC can easily be envisaged because such a behaviour would tend to stabilize committed developmental decisions. In this sense, cyaB1 may constitute a cAMP switch that senses and interprets signals of changing environmental conditions, and accordingly initiates and maintains lasting developmental programs. Obviously, it will be interesting to see how such a switch is turned off.

Generation of a cGMP-activated cyaB1 AC

GAF domains are not known to possess an intrinsic enyzme activity. They fit the classification as a regulatory small-molecule-binding domain (Aravind and Ponting, 1997; Anantharaman et al., 2001). The distribution of GAF domains among all phyla suggests that this module has been optimized early in evolution and been reused in differing regulatory contexts. So much can be deduced from bioinformatic studies. We now provide a striking experimental example of this conclusion. Replacing the cyanobacterial GAF tandem with that from rat PDE2, we generated a cGMP-activated AC. The cGMP concentration needed for half-maximal activation was 3 µM, i.e. identical to that for PDE2 activation, whereas cAMP had no effect (Sonnenburg et al., 1991). This raises the question of how the signal generated by binding of the ligand to the GAF domain is transmitted to the catalytic domain. This is particularly intriguing because the rat PDE2 GAF domains operate in a protein background of cyaB1, in which an intervening PAS domain and an extended linker region separate the catalyst from the GAF assemblage (Figure 1A). We propose that the mechanism of GAF-domain activation, as accomplished by the movement of structurally rigid protein domains by a fixed angle and distance, is largely context independent (S.F.Martinez, A.Y.Wu, N.A.Glavas, X.B.Tang, S.Turley, W.G.J.Hol, J.A.Beavo, submitted for publication). The principle of such a simple and successful regulatory switch seems to have been maintained for >2 billion years and spread to all phyla, to be used in conjunction with many different effector domains.

Materials and methods

Recombinant DNAs

The cyaB1 gene (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. D89623; gift of Professor M.Ohmori, University of Tokyo) was assembled into the BamHI–SmaI sites of pQE30 via subcloning steps involving pBluescriptII SK(–). With cyaB1 as a template, cyaB1595–781 and cyaB1595–859 were amplified by PCR using specific primers. All recombinant proteins were fitted with an N-terminal MRGSH6GS affinity tag. Single amino acid mutations (K646A, K646E, D650A, N728A, R732A and T721A in the catalytic domain, and D190A, D360A and A275D in the GAF domain) were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using respective PCR primers and the DNA coding for cyaB11–859 as a template. Restriction sites located nearby were used where appropriate or were inserted by silent mutations.

The GAF domain from rat PDE2 (E207–N546) was amplified from a rat intestine cDNA library using specific primers. SfuI and XhoI sites were added at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The PCR product was inserted into SfuI and XhoI sites of cyaB1, which were introduced by silent mutations, and replaced the cyanobacterial sequence from Q50 to L385 in cyaB1 (see Figure 1C). The fidelity of all constructs was verified by double-stranded sequencing. Primer sequences are available on request.

Expression and purification of bacterially expressed proteins

The constructs in the pQE30 expression plasmid were transformed into E.coli BL21(DE3)[pREP4]. Cultures were grown in Lennox L broth at 25°C containing 100 mg/l ampicillin and 25 mg/l kanamycin. For cyaB1595–859 and its mutants, cultures were induced with 300 µM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and incubated at 27°C for 3 h. For cyaB11–859, its mutants and the cyaB1–ratPDE2 GAF chimera (cyaB1rat-GAF), the cultures were induced with 7.5 or 15 µM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at an A600 of 0.6 and grown overnight at 20°C. Bacteria were harvested and washed once with 50 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.5 and stored at –80°C. For purification, frozen cells were suspended in 20 ml of cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM l-thioglycerol and 2 mM MgCl2) and sonicated (3 × 10 s). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (48 000 g for 30 min). Nickel-NTA slurry (200 µl; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was added to the supernatants. After gentle rocking for 60 min at 0°C, the resin was poured into a column and washed (2 ml/wash) (wash buffer A: 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 10 mM 1-thioglycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, 400 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole; wash buffer B: wash buffer A with 15 mM imidazole; wash buffer C: wash buffer A with 10 mM NaCl and 15 mM imidazole). Proteins were eluted with 0.5–1 ml of buffer C containing 150 mM imidazole. For cyaB11–859, its mutants and the cyaB1rat-GAF chimera, all buffers contained 20% glycerol. Because of the poor stability of cyaB1595–859 and cyaB11–859 in the presence of 150 mM imidazole, the eluates were immediately dialysed overnight against 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 (for cyaB1595–859 with 2 mM 1-thioglycerol) and 20% glycerol. The purified proteins could be stored in dialysis buffer at –20°C.

AC assay

The AC activity of cyaB1595–859 and its mutants was measured for 4 min at 45°C in a final volume of 100 µl (Salomon et al., 1974). The reactions usually contained 22% glycerol, 50 mM MOPS–Na pH 8.5, either 2 mM MnCl2 or 10 mM MgCl2, and 75 µM [α-32P]ATP (25 kBq) and 2 mM [2,8-3H]cAMP (150 Bq) to determine yield during product isolation. Creatine phosphate (3 mM) and 1 U of creatine kinase were used as an ATP-regenerating system when assaying crude extracts. To determine kinetic constants, the concentration of ATP was varied from 2 to 1600 µM, with a fixed concentration of 2 mM Mn2+ or 10 mM Mg2+. The protein concentration was adjusted to keep substrate conversion to <10%. The reaction was started by addition of substrate.

For cyaB11–859, its mutants and the cyaB1rat-GAF chimera, the samples were incubated for 4 min at 37°C in a buffer containing 22% glycerol, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, either 2 mM MnCl2 or 10 mM MgCl2, and 75 µM [α-32P]ATP (25 kBq). [2,8-3H]cAMP was added after stopping the reaction together with the stop buffer (Salomon et al., 1974). To determine kinetic constants, the concentration of ATP was varied from 2 to 240 µM with a fixed concentration of 2 mM Mn2+ or 10 mM Mg2+. Usually, <10% of the ATP was consumed at the lowest substrate concentrations. The data are means from several experiments. Unless indicated, the standard deviations (SD) were usually <5%.

cAMP binding assays

Binding of cAMP was assayed using a modification of previously described protocols (McAllister-Lucas et al., 1995; Ho et al. 2000). Briefly, 2 µg of affinity-purified cyaB1 or cyaB1D360A were incubated for 1 h at 0°C in the presence of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.8, 1 mM EDTA and various concentrations (0.5–10 µM) of cAMP (with trace [3H]cAMP). Samples were applied to pre-moistened HAWP filters (0.45 µm; Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) and rinsed with 10 ml of 10 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.8 containing 1 mM EDTA. Dry filters were counted for 3H using scintillation counting. Background levels of nucleotide binding to filters, as determined with 2 µg of BSA/incubation instead of enzyme, were subtracted.

Western blot analysis

Protein was mixed with sample buffer and subjected to SDS–PAGE (12.5%). Proteins were blotted onto PVDF membranes and sequentially probed with a commercial anti-RGS-His4 antibody (Qiagen) and with a 1:5000 dilution of a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). Peroxidase detection was carried out with the ECL-Plus kit (Amersham-Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Christian Beyer, Franziska Berndt, Maurizio Di Stasio and Miguel A.Pineda for help, and Dr J.Beavo (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) for information on the crystal structure of the PDE2 GAF domains prior to publication. This work was supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

References

- Adams D.G. and Duggan,P.S. (1999) Heterocyst and akinete differentiation in cyanobacteria. New Phytol., 144, 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Amin N. and Peterkofsky,A. (1995) A dual mechanism for regulating cAMP levels in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 11803–11805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaman V., Koonin,E.V. and Aravind,L. (2001) Regulatory potential, phyletic distribution and evolution of ancient, intracellular small-molecule-binding domains. J. Mol. Biol., 307, 1271–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L. and Ponting,C.P. (1997) The GAF domain: an evolutionary link between diverse phototransducing proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci., 22, 458–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzu O. and Danchin,A. (1994) Adenylyl cyclases: a heterogeneous class of ATP-utilizing enzymes. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 49, 241–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudart-Cavalli M.P., Sismeiro,O. and Danchin,A. (1997) Bifunctional structure of two adenylyl cyclases from the myxobacterium Stigmatella aurantiaca. Biochimie, 79, 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granovsky A.E., Natochin,M., McEntaffer,R.L., Haik,T.L., Francis,S.H., Corbin,J.D. and Artemyev,N.O. (1998) Probing domain functions of chimeric PDE6α′/PDE5 cGMP-phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 24485–24490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.L., Seebacher,T., Kurz,U., Linder,J.U. and Schultz,J.E. (2001) Adenylyl cyclase Rv1625c of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a pro genitor of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. EMBO J., 20, 3667–3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanoune J., Pouille,Y., Tzavara,E., Shen,T., Lipskaya,L., Miyamoto,N., Suzuki,Y. and Defer,N. (1997) Adenylyl cyclases: structure, regulation and function in an enzyme superfamily. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol., 128, 179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y.S., Burden,L.M. and Hurley,J.H. (2000) Structure of the GAF domain, a ubiquitous signaling motif and a new class of cyclic GMP receptor. EMBO J., 19, 5288–5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper S. and Böck,A. (1995) Effector-mediated stimulation of ATPase activity by the σ54-dependent transcriptional activator FHLA from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 177, 2798–2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J.H. (1999) Structure, mechanism and regulation of mammalian adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 7599–7602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M. and Ohmori,M. (1999) Activation of a cyanobacterial adenylate cyclase, CyaC, by autophosphorylation and a subsequent phosphotransfer reaction. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 15167–15172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M., Yashiro,K., Sakamoto,T. and Ohmori,M. (1997) The Spirulina platensis adenylate cyclase gene, cyaC, encodes a novel signal transduction protein. Plant Cell Physiol., 38, 828–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M., Unno,T., Yashiro,K. and Ohmori,M. (2001) CyaG, a novel cyanobacterial adenylyl cyclase and a possible ancestor of mammalian guanylyl cyclases. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 10564–10569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama M. and Ohmori,M. (1997) Isolation and characterization of multiple adenylate cyclase genes from the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol., 179, 3588–3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder J.U., Hoffmann,T., Kurz,U. and Schultz,J.E. (2000) A guanylyl cyclase from Paramecium with 22 transmembrane spans. Expression of the catalytic domains and formation of chimeras with the catalytic domains of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 11235–11240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister-Lucas L.M. et al. (1993) The structure of a bovine lung cGMP-binding, cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase deduced from a cDNA clone. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 22863–22873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister-Lucas L.M., Haik,T.L., Colbran,J.L., Sonnenburg,W.K., Seger,D., Turko,I.V., Beavo,J.A., Francis,S.H. and Corbin,J.D. (1995) An essential aspartic acid at each of two allosteric cGMP-binding sites of a cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 30671–30679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue L.A., McDonough,K.A. and Lawrence,C.E. (2000) Functional classification of cNMP-binding proteins and nucleotide cyclases with implications for novel regulatory pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res., 10, 204–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterkofsky A., Reizer,A., Reizer,J., Gollop,N., Zhu,P.P. and Amin,N. (1993) Bacterial adenylyl cyclases. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 44, 31–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon Y., Londos,C. and Rodbell,M. (1974) A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal. Biochem., 58, 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J., Milpetz,F., Bork,P. and Ponting,C.P. (1998) SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 5857–5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit M.J. and Iyengar,R. (1998) Mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res., 32, 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderling S.H. and Beavo,J.A. (2000) Regulation of cAMP and cGMP signaling: new phosphodiesterases and new functions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenburg W.K., Mullaney,P.J. and Beavo,J.A. (1991) Molecular cloning of a cyclic GMP-stimulated cyclic nucleotide phospho diesterase cDNA. Identification and distribution of isozyme variants. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 17655–17661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara R.K., Dessauer,C.W. and Gilman,A.G. (1996) Complexity and diversity of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 36, 461–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara R.K., Beuve,A., Tesmer,J.J., Sprang,S.R., Garbers,D.L. and Gilman,A.G. (1998) Exchange of substrate and inhibitor specificities between adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 16332–16338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W.J. and Gilman,A.G. (1995) Construction of a soluble adenylyl cyclase activated by Gsa and forskolin. Science, 268, 1769–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W.J. and Hurley,J.H. (1998) Catalytic mechanism and regulation of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Mol. Pharmacol., 54, 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W.J., Stanzel,M. and Gilman,A.G. (1995) Truncation and alanine-scanning mutants of type I adenylyl cyclase. Biochemistry, 34, 14563–14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer J.J., Sunahara,R.K., Gilman,A.G. and Sprang,S.R. (1997) Crystal structure of the catalytic domains of adenylyl cyclase in a complex with Gsa-GTPgS. Science, 278, 1907–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer J.J., Sunahara,R.K., Johnson,R.A., Gosselin,G., Gilman,A.G. and Sprang,S.R. (1999) Two-metal-ion catalysis in adenylyl cyclase. Science, 285, 756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turko I.V., Haik,T.L., McAllister-Lucas,L.M., Burns,F., Francis,S.H. and Corbin,J.D. (1996) Identification of key amino acids in a conserved cGMP-binding site of cGMP-binding phosphodiesterases. A putative NKXnD motif for cGMP binding. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 22240–22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turko I.V., Francis,S.H. and Corbin,J.D. (1999) Studies of the molecular mechanism of discrimination between cGMP and cAMP in the allosteric sites of the cGMP-binding cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase (PDE5). J. Biol. Chem., 274, 29038–29041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk C.P. (2000) Heterocyst formation in Anabaena. In Brun,Y.V. and Shimkets,L.J. (eds), Prokaryotic Development. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp. 83–104.

- Yan S.Z., Hahn,D., Huang,Z.H. and Tang,W.J. (1996) Two cytoplasmic domains of mammalian adenylyl cyclase form a Gsa- and forskolin-activated enzyme in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 10941–10945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.Z., Huang,Z.H., Shaw,R.S. and Tang,W.J. (1997) The conserved asparagine and arginine are essential for catalysis of mammalian adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 12342–12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Liu,Y., Ruoho,A.E. and Hurley,J.H. (1997) Structure of the adenylyl cyclase catalytic core. Nature, 386, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]