Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory condition characterized by neurodegeneration and lost myelin, or demyelination. This lost myelin may be regenerated in people with MS through a process called remyelination, that is prone to failure and is impaired with age. Remyelination is facilitated by microglia but our understanding of the microglial response during remyelination is incomplete. Here, we profile the microglial response during remyelination in the lysolecithin mouse model using single-cell RNA sequencing and find several distinct microglial states during the early stages of remyelination that coalesce into a resolved state defined by the presence of myelin transcripts, a state also present in MS brains. We also observe a delay in the appearance of several microglial states with age, in concordance with delayed remyelination. This multi-faceted microglial response during efficient remyelination provides the basis of multi-faceted microglia-specific targets for future MS therapies.

Subject terms: Microglia, Multiple sclerosis, Neuroimmunology

Microglial states throughout remyelination are incompletely understood. Here, the authors show that microglia form several states during the early stages of remyelination that coalesce into a partially resolved state that is dysregulated with age.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a debilitating neurodegenerative condition characterized by multiple demyelinating lesions1, leading to cognitive, motor, and sensory impairments2. Remyelination is a spontaneously occurring regenerative process with the potential to rescue functional deficits, reduce disability, and protect against neurodegeneration due to demyelination3–7. However, remyelination is highly variable—ranging from 20–80%—in people with MS3,6–8 and declines with age9–12. There are currently several remyelination-based therapies in clinical trials, yet none have been approved to treat MS13,14.

Remyelination is intricately regulated by the innate immune system11,15–17, which performs the rate-limiting step of clearing inhibitory myelin debris18–20. Following acute demyelination, monocytes are recruited to the injury site along with the resident microglia16,21. Here, the microglia and monocyte-derived macrophages begin to clear the myelin debris resulting from the demyelinating injury16,21. Additionally, microglia facilitate remyelination through other, non-redundant, mechanisms16 that remain incompletely understood.

Microglia alter their transcriptional states while performing these diverse functions22,23. Microglia form several transcriptionally distinct states during development, which converge into a homogeneous state of homeostasis during adulthood24–26 and further diverge into reactive states during aging and disease25,27,28. While the complexities of these distinct states are being investigated, less is known about the states specific to remyelination and the impacts of aging on remyelination-specific states.

By understanding the microglial response during efficient remyelination in young mice and inefficient remyelination in middle-aged mice9,12, we aim to identify mechanisms of age-related remyelination delay. In this study, we sequenced microglial RNA at the single-cell level throughout remyelination using the lysolecithin (LPC) model in young and middle-aged mice. Microglia adopted a diverse, or multi-faceted, response in the early stages of remyelination characterized by transcriptionally distinct states, which later coalesced into a partially resolved state characterized by myelin transcripts—myelin transcript-enriched microglia (MTEM)—at the late stages of remyelination. MTEM were present during myelin pruning, which could be the source of their myelin transcripts. We also found MTEM in human MS brains, enriched within remyelinating shadow plaques. With age, slow remyelination was associated with delayed emergence of certain microglial states.

Results

A multifaceted microglial response is present during early oligodendrogenesis and resolves with remyelination in young mice

Microglia shift their transcriptomic signature into several distinct states during degenerative conditions such as MS and Alzheimer’s disease22,29–31 but it is unclear how these microglial states arise or resolve. In the murine system, remyelination is a robust regenerative response that protects axons13,32–34. However, the microglial states that arise and change during remyelination are incompletely understood. We first coupled scRNAseq with lineage tracing tools to validate that bioinformatics could be used to accurately distinguish microglia from monocyte-derived macrophages. This was a critical initial step because microglia downregulate the expression of canonical homeostatic genes during injury and adopt a reactive transcriptional profile similar to monocyte-derived macrophages21,35. We conducted single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) on fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-isolated F4/80+ myeloid cells from 2-month-old, sham-lesioned Cx3cr1creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato spinal cords. Here, microglia and border-associated macrophages (BAM), but not monocyte-derived macrophages, are permanently labeled with tdTomato16,21,36 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Hexb, P2ry12 and Tmem119 overlapped considerably (up to 98.4%) with tdTomato-labeled microglia and lacked expression of genes used to identify other cell types (Supplementary Fig. 1b–d). Therefore, Hexb, P2ry12 and Tmem119 sufficiently defined microglia in place of lineage tracing. In this validation, we isolated cells through warm, enzymatic tissue digestion and similar to Marsh and colleagues, we found this method yielded an ex vivo artifact including early response genes like Fos and Junb37 (Supplementary Fig. 1c). All subsequent isolations of microglia were conducted using cold, mechanical dissociation to prevent this ex vivo artifact37, ensuring that microglial signatures recapitulate gene expression found in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 1e, g).

To define microglial states present during remyelination, we used the lysolecithin (LPC) mouse model wherein LPC injection into the spinal cord results in a demyelinating lesion that remyelinates over three weeks38. We isolated F4/80+ myeloid cells via FACS and conducted scRNAseq throughout remyelination at 7 days post LPC injection (DPI), when oligodendrogenesis begins, 14 DPI21,39, when oligodendrogenesis peaks and 21 DPI16, when remyelination is largely complete, along with sham-lesioned and naïve control groups (Fig. 1a–d). Following quality control, we clustered all cells and re-clustered 26,424 microglia (Hexb+, P2ry12+, Fcrls+, Tmem119+) (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Microglia adopt Igf1 ReAM, Ccl3 ReAM, proliferative microglia, or IRM signatures at 7 DPI and an MTEM signature at 21 DPI in young mice.

a scRNAseq experimental workflow. Created in BioRender. Ho, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/sm1j9hf. b UMAP showing 26,424 microglia collected from (c) naïve (nM = 5 pooled per control sample) and (d) sham (nM = 5) controls and at (e) 7 (nM = 10 pooled per LPC-injected sample), (f) 14 (nM = 10) and (g) 21 DPI (nM = 12) from young, 2-month-old mice. h Proportion and (i) total counts of each sample present in each microglial cluster identified in (b). j Differentially expressed genes used to define microglial states. Representative and 3D rendered images (scale bar = 10 μm) of spinal cord lesions from Tmem119creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato mice with tdTomato (magenta) labeling microglia, k mRNA probes for Igf1 (green) and Irf7 (gray) and m Plp1 (gray) l Quantification of Igf1, Irf7 (3 DPI, nF = 0, nM = 5; 7 DPI, nF = 5, nM = 0; 21 DPI, nF = 3, nM = 2) positivity in tdTomato+ microglia at 3, 7 and 21 DPI. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. n Quantification of Plp1 (3 DPI, nF = 0, nM = 4; 7 DPI, nF = 4, nM = 0; 21 DPI, nF = 2, nM = 2) positivity in tdTomato+ microglia at 3, 7 and 21 DPI. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. Each point represents one animal, and all data are presented as mean ± SEM. All library cell numbers are normalized to the library with the lowest cell count. Source data are provided as a source data file. nF = nFemale Mice and nM = nMale Mice.

We identified 14 microglial states across all stages of remyelination and found the greatest diversity present at 7 DPI, a stage that coincides with early stages of oligodendrogenesis (Fig. 1h, i). Homeostatic microglia (HM; P2ry12+, Cx3cr1+) were enriched in cells isolated from naïve and sham-lesioned mice. States common to both injured and uninjured conditions were classified as transitioning microglia (TM) and states enriched in translation-related genes, but not other markers of microglial reactivity, were classified as primed microglia (PM). PM were specific to naïve and sham groups (PM1) or 7 and 21 DPI (PM2 and PM3). Given that there was a transition from high to low homeostatic gene expression between PM1 and PM2, the primed microglial state may represent an early response to damage or dysfunction. The majority (80.6%) of the proliferative microglia (Mki67 + and Top2a+)40 were present at 7 DPI, coinciding with the late stages of microglial proliferation in this model21. Interferon-responsive microglia (IRM; Irf7 +, Ifitm3 +) were present at 7 DPI and sustained until 21 DPI at very low levels (Fig. 1h, i). Interestingly, we found similar levels of microglial states across three independent replicates (Supplementary Fig. 2).

We identified three states specific to remyelination that we refer to as remyelination-associated microglia (ReAM) (Fig. 1). Igf1 ReAM and Ccl3 ReAM, characterized by Igf1 and Ccl3, respectively, were specific to 7 and 14 DPI. Myelin transcript-enriched microglia (MTEM) (1 and 2), specific to 21 DPI, were characterized by myelin transcripts, including Mobp, Plp1 and Mbp, but surprisingly not OPC or oligodendrocyte cell body restricted transcripts (Supplementary Fig. 3a). MTEM 2 also contained higher levels of myelin transcripts compared to MTEM 1, suggesting variability with this microglial state. Interestingly, MTEM (1 and 2) contained higher levels of HM markers and lower levels of Igf1 and Ccl3 ReAM markers, suggesting a partial resolution of inflammatory processes (Fig. 1j).

To confirm the presence of Igf1 ReAM, IRM and MTEM in vivo, we performed RNAscope with Igf1, Irf7 and Plp1 mRNA probes, respectively at 3, 7, and 21 DPI in Tmem119creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato mice. Here, tdTomato expression is restricted to microglia, excluding both BAM and monocyte-derived macrophages41–43. Igf1 and Irf7 expression—indicative of Igf1 ReAM and IRM respectively—peaked at 7 DPI (Fig. 1k, l, Supplementary Fig. 1h, i) and Plp1 expression—indicative of MTEM—was largely restricted to 21 DPI (Fig. 1m, n, Supplementary Fig. 1j). Plp1 expression in microglia was not due to autofluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Interestingly, Plp1 mRNA was minimally present inside microglia at 3 and 7 DPI, when there is ongoing debris clearance16.

Overall, microglial transcriptional states changed during remyelination with early stages characterized by a multi-faceted microglial response that included Igf1 ReAM, Ccl3 ReAM, IRM and proliferative microglia and late stages characterized by a partially resolved, more homogeneous, state containing myelin transcripts (MTEM).

Microglial states in early stages of remyelination are associated with lipid processing and cytokine production while states in the later stages of remyelination prune newly laid myelin

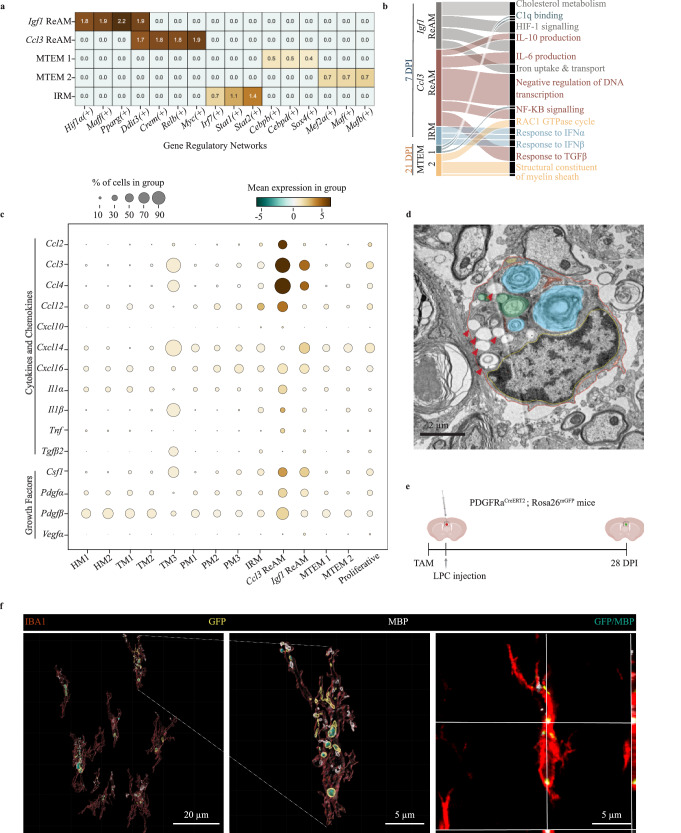

Gene regulatory networks (GRN) comprising transcription factors, factors that regulate and are regulated by these transcription factors, and downstream target genes are critical in defining cell states. We used the Single Cell Regulatory Network Interference and Clustering (SCENIC)44 tool to determine active GRN in microglial states as a further indicator of distinctiveness. Indeed, the Igf1 and Ccl3 ReAM, IRM and MTEM have minimal GRN overlap, suggesting these are distinct states (Fig. 2a). Igf1 ReAM activate Pparg(+) and Maff(+) GRN which are associated with lipid sensing and cholesterol metabolism respectively45.

Fig. 2. MTEM prune newly laid myelin while Igf1 ReAM are associated with lipid processing and Ccl3 ReAM with cytokine release.

a Heatmap showing gene regulatory networks active in Igf1 ReAM, Ccl3 ReAM, MTEM (1 and 2), and IRM where each network contains the active transcription factors, regulators, and the downstream target genes. The networks are denoted by ‘(+)’ following the transcription factor’s name. b Functional terms associated with the differentially expressed genes in Igf1 ReAM, Ccl3 ReAM, MTEM (1 and 2), and IRM as determined by the KEGG, REACTOME and Gene Ontology databases. c Dot plot describing the mean expression level of the cytokine, chemokine and growth factor genes expressed by microglial states. d Electron microscopy image of a microglia at 21 DPI from a Cx3Cr1CreERT2+/−; ROSA26iDTR- mouse showing the cell membrane (red outline), nuclear membrane (yellow outline), lysosomes (green), autophagolysosomes (yellow), endoplasmic reticulum (red), dilated endoplasmic reticulum (white asterisk), empty phagosome (black asterisk), myelin containing phagosome (blue) and lipid droplets (red arrows). Individual image taken. e Schematic describing tamoxifen injection followed by LPC injection into the corpus callosum of PDGFRαCreERT2; Rosa26mGFP mice, and tissue isolation at 28 DPI. Created in BioRender. Ho, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/1yvoyb1. f 3D rendering of IBA1+ microglia (red), MBP (blue), GFP (yellow) and colocalization of MBP with GFP (teal) from the corpus callosum of PDGFRαCreERT2; Rosa26mGFP mice at 28 DPI.

The Igf1 and Ccl3 ReAM both express the Ddit3(+) GRN. Ddit3, also known as Chop, is expressed during apoptosis through endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. In microglia, ER stress occurs after myelin debris uptake, likely due to cholesterol esterification in the ER46. Ccl3 ReAM are also characterized by the Relb(+), Myc(+), and Crem(+) GRN. The Relb(+) network forms a complex to regulate the activities of NFΚB signaling, a critical regulator of cytokine and chemokine production. The Myc(+) network is broadly important in growth response, and is sufficient to immortalize microglia in culture47. Crem(+), or cyclic AMP (cAMP) response element modulator, is critical in cAMP signaling, with an unknown role in microglia.

In line with interferon response genes, IRM expressed Irf7(+), Stat1(+), and Stat2(+) networks that are active in response to interferons. Finally, MTEM upregulated Cebpb (+), Cebpd (+), Mef2a (+), Mafb(+) and Maf(+) networks that define homeostatic microglia48,49, further suggesting that MTEM shift towards a homeostatic microglial state.

To understand potential functional differences between microglial states, we examined functions associated with genes that were differentially expressed by Igf1 ReAM, Ccl3 ReAM, IRM and MTEM (Fig. 2b). Confirming the active GRNs, Igf1 ReAM were associated with cholesterol metabolism along with iron uptake and transport. As oligodendrocytes are rich in both iron and cholesterol50,51, Igf1 ReAM may phagocytose and process oligodendrocyte and myelin debris.

Ccl3 ReAM were associated with IL-10 and IL-6 production, NFΚB signaling, and response to TGFβ, suggesting an involvement in cytokine regulation (Fig. 2b). We systematically evaluated cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor gene expression by microglia throughout remyelination. We found that Ccl3 ReAM expressed chemokines (Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl4, Ccl12, and Cxcl16) as well as canonical pro-inflammatory cytokines (Il1α, Il1β, and Tnf) suggesting this state is a hub for chemokine and cytokine regulation (Fig. 2c), many of which are known to impact OPC proliferation, migration, and differentiation52. Igf1 ReAM expressed these pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines to a lesser extent, demonstrating that there are multiple pro-inflammatory microglial states during remyelination.

IRM were associated with type I and type II interferon responses (α, β and γ), and expressed the classical interferon-dependent chemokine, Cxcl10 (Fig. 2b, c). Consistent with their name, MTEM were enriched in genes associated with constituents of the myelin sheath and RAC1 GTPases, but expressed limited cytokine, chemokine, or growth factor genes (Fig. 2b, c). Taken together, the diverse microglial states likely take on different functions through ligand production and other means.

We were intrigued by the presence of Plp1, which encodes a myelin protein53, in MTEM. The presence of myelin protein transcripts was not an artifact of aberrant isoforms or ambient RNA capture (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c) and Plp1 was also present in tdTomato+ microglia (Fig. 1m, n). Additionally, MTEM expressed other oligodendrocyte-defining (Mbp, Mog, Mobp) genes but not neuron-defining (Rbfox3, Tubb3), astrocyte-defining (Gfap, Aldh1l1), or pericyte-defining genes (Pdgfrβ, Abcc9) (Supplementary Fig. 3d). While Mbp is enriched in oligodendrocytes, a transcript variant of Mbp—called Golli Mbp—is expressed by other immune cells, like T lymphocytes54. We found two variants of Golli Mbp comprising 0.01% of the Mbp transcripts identified within microglia (Supplementary Fig. 3a), suggesting that microglia minimally express Golli Mbp, and instead obtain myelin transcripts from oligodendrocytes.

The presence of MTEM at 21 DPI is well after the clearance of myelin debris from the initial demyelinating injury16. Microglia engulf and prune over-produced myelin under homeostatic conditions in development55,56, which is thought to explain developmental microglia expressing myelin transcripts24. Late stages of remyelination (21 DPI) may similarly involve ongoing myelin pruning. Myelin contains mRNA transcripts57–59 and we reasoned that myelin pruning may be a mechanism by which these transcripts enter microglia. Indeed, microglial ultrastructure within electron micrographs confirmed the presence of myelin inside microglial phagosomes at 21 DPI (Fig. 2d). To delineate engulfment of myelin debris from newly-laid myelin, we labeled OPC and the resulting newly-laid myelin following demyelination using PDGFRαCreERT2; Rosa26mGFP mice. These mice were injected with LPC into the corpus callosum and given tamoxifen for 5 days to activate the expression of membrane-tethered GFP in OPC (Fig. 2e). Using 3D rendering of microglia in these mice, we confirmed the presence of GFP+MBP+ newly-laid myelin inside IBA1+ microglia at 28 DPI (Fig. 2f). Myelin pruning is a likely source of the presence of myelin transcript, although the possibility of myelin transcript transfer by extracellular vesicles60 or ribosomal transfer by oligodendrocytes and OPC61 remains.

We recently showed that microglia facilitate remyelination independent of myelin debris clearance16. Here, through active GRN and functional associations, Igf1 ReAM likely engage in lipid processing, Ccl3 ReAM likely secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines, IRM respond to interferon and MTEM likely return to homeostasis and prune remyelinated axons.

Igf1 ReAM, MTEM, and TM3 are terminal states of microglial trajectories while IRM is a transitional state leading to MTEM

The appropriate initiation and resolution of the microglial response, while critical for remyelination11,15,16,62–65, remains incompletely understood. We identified several microglial states during remyelination and used scVelo to determine how microglial states change over time and whether they co-exist independently or are direct derivatives of preceding states66,67. The trajectory followed by any given state was determined by the ratio of spliced to unspliced mRNA transcripts for all measured genes compared to those of the neighboring cells.

The microglial response during remyelination did not follow a single linear trajectory from 7 to 21 DPI (Fig. 3a). Using scVelo, we found that the microglial response originated from PM and proliferating microglial states. We identified Igf1 ReAM, MTEM 2 and TM3 (Fig. 3b) as the three terminal states of microglial transition based on stability (Supplementary Fig. 4a), or states with mostly incoming cells and few outgoing cells (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Consistent with their definition of being terminal states, the Igf1 ReAM, MTEM 2 and TM3 have high confidence in the velocity measurement (Supplementary Fig. 4b) and low velocity length suggesting lower rates of transcription (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Fig. 3. Microglial transitions result in three terminal states: Igf1 ReAM, MTEM 2 and TM3.

a Microglial trajectories mapped using RNA velocity. Microglial trajectories terminate in (b) Igf1 ReAM, MTEM 2 and TM3 states as identified by a stability index > = 0.96. c Circular projection plot of cell fates towards the terminal states (vertices), where the cells closer to the terminal states are committed to the trajectory while the cells present in the centre of the triangle have multi-lineage potential. Random walk analyses, where the orange circles represent the supervised origin point and the yellow circles represent the unsupervised termination point, showing that (d) proliferative microglia terminate in Igf1 ReAM, e IRM terminate in MTEM 2 and f schematic describing microglial transitions. Pseudotime-determined trajectory showing the driver genes of the Igf1 ReAM state, g Igf1 and h Gpnmb increase towards the termination of the Igf1 ReAM trajectory, but not the MTEM 2 or TM3 trajectories. i Density of IRM lineage (YFP+IBA1+) microglia from Mx1cre; Rosa26YFP mice at 3 DPI (nF = 1, nM = 4), 7 DPI (nF = 3, nM = 2) and 21 DPI (nF = 2, nM = 2). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. j, l Representative images (scale bar = 10 μm) of spinal cord lesions from Mx1cre; Rosa26YFP mice with YFP (green) labeling Interferon responsive lineage cells, IBA1 (magenta) labeling microglia and probes for (j) Irf7 (top gray) and Igf1 (bottom gray) showing interferon lineage derived IRM and Igf1 ReAM respectively at 7 DPI or (l) Plp1 probe (gray) showing IRM lineage derived MTEM at 21 DPI. k Quantification of Igf1, Irf7 positivity in YFP+IBA1+ microglia shown in (j). Two-tailed unpaired t-test. m Quantification of Plp1 positivity in YFP+Iba1+ microglia shown in (l) at 3 DPI (nF = 1, nM = 40), 7 DPI (nF = 3, nM = 2) and 21 DPI (nF = 2, nM = 2). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. Each point represents one animal, and all data are presented as mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a source data file. nF = nFemale Mice and nM = nMale Mice.

Surprisingly, we found Igf1 ReAM to be a terminal state despite being predominantly present during early stages of remyelination, at 7 DPI. Visualizing the transitions in a circular projection plot, where cells are placed closest to their terminal state, we found PM transitioned into Igf1 ReAM and MTEM (Fig. 3c). As Igf1 ReAM were a terminal state of microglial transition peaking during the initiation of oligodendrogenesis, we further explored the predicted functions of Igf1 ReAM and microglial states present at 7 DPI on oligodendrogenesis, specifically through OPC differentiation. Using predictive modeling, we determined that microglia may secrete PDGFA, TGFβ, CSF1, JAM2, SEMA4D and GAS6 onto OPCs (Supplementary Fig. 5a), however, these factors did not promote OPC differentiation into oligodendrocytes in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 5b–d). Igf1 ReAM may interact with OPCs to promote proliferation or differentiation through other means.

To assess the trajectory of specific states, we used random walk assessment and found that proliferative microglia terminate in Igf1 ReAM (Fig. 3d) and IRM terminate in MTEM (Fig. 3e). As IRM arise from PM, this suggests that IRM are an intermediate state of microglial transition to MTEM. We further assessed the differentiation potential of each cell along the three terminal trajectories using CytoTrace and report Spp1, Gpnmb, Igf1, Lilrb4a genes, specific to the Igf1 ReAM state, increase in expression towards the end of the Igf1 ReAM trajectory but not the MTEM or TM3 trajectories (Fig. 3g, h, Supplementary Fig. 4e, f). We supplemented the predictive lineage tracing with in vivo lineage tracing using the Mx1cre; Rosa26YFP mice, where interferon lineage cells are labeled with YFP. We found IRM lineage microglia peaked at 7 DPI (Fig. 3i) and 60% of which were IRM expressing Irf7 (Fig. 3j, k). In contrast to the predicted trajectory, we found 20% of IRM lineage microglia expressing Igf1, suggesting the Igf1 ReAM state may partially originate from IRM (Fig. 3j, k). Interestingly, 40% of IRM lineage microglia transitioned to MTEM at 21 DPI, as predicted (Fig. 3l, m).

Together, microglial state trajectories terminate 1) early during remyelination in Igf1 ReAM, having transitioned from PM, Ccl3 ReAM, proliferative microglia and partially through IRM, 2) later during remyelination in MTEM, having transitioned from PM with IRM acting as a transient intermediate state or 3) within TM3 (Fig. 3f).

Absence of IRM negatively affects remyelination

To determine how early microglial states impact later microglial states and remyelination we induced focal demyelination in mice lacking responsivity to type I interferons (IFNAR1KO mice). Type I interferons are critical factors initiating the IRM state68 during neurodegeneration. At 7 DPI, IFNAR1KO mice showed increased numbers of IBA1+ cells, indicative of greater microglia and macrophage recruitment. Consistent with type I interferons inducing IRM, IFNAR1KO mice were almost completely deficient in IRM inside the lesion, based on Irf7 + IBA1+ cells (Fig. 4a). As the vast majority of myeloid cells inside the lesion are microglia16, the drop in Irf7 + IBA1+ cells is likely due to impaired induction of IRM. IFNAR1KO mice did not show differences in lesion volume, suggesting no heightened demyelination (Fig. 4b). To assess different ReAM populations we quantified MAC2+ (enriched in Igf1 ReAM) or IL1β+ (enriched in Ccl3-ReAM) microglia. IFNAR1KO had no differences in density of MAC2+ or IL1β+ microglia, suggesting IRM do not impact ReAM subpopulations (Fig. 4c, d). Interestingly, the lack of IRM had a profound impact on the oligodendrocyte lineage, reducing the density of proliferative OPCs at 7 DPI (Fig. 4e) and myelinating oligodendrocytes at 21 DPI (Fig. 4h), without changing the density of newly differentiated oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4f, g). IFNAR1KO also had a roughly 60% reduction in remyelination at 21 DPI (Fig. 4i). Notably, the reduction of myelinating oligodendrocytes and remyelination was concomitant with 30% reduction (p = 0.787) in Plp1+ IBA1+MTEM (Fig. 4j). Overall, type I interferon is critical for remyelination, inducing IRM, which transition into MTEM.

Fig. 4. Absence of IRM in IFNAR1KO mice reduces OPC proliferation, late stages of oligodendrocyte differentiation and remyelination.

Representative images and quantification of (a) IBA1 (green), Irf7 (gray) density at 7 DPI from WT (nF = 3, nM = 3) and IFNAR1KO (nF = 3, nM = 2) mice. Arrowheads highlight Irf7+IBA1+ cells. Representative microglia for each group (gray square) are shown in the inset. b IBA1 (green), MAC2 (red) density at 7 (WT, nF = 4, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 4) and 21 DPI (WT, nF = 3, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 2). Inset shows MAC2 in greyscale. c IBA1 (green), IL1β (gray) density at 7 (WT, nF = 4, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 4) and 21 DPI (WT, nF = 3, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 2). Inset shows IL1β in greyscale. d OLIG2 (gray), PDGFRα (red), KI67 (green) density at 7 DPI (WT, nF = 4, nM = 2; IFNAR1KO, nF = 3, nM = 2). Arrowheads highlight OLIG2+PDGFRα+KI67+ cells. e MYRF (gray) density at 7 (WT, nF = 4, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 2) and 21 DPI (WT, nF = 3, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 2). f CNP (green), OLIG2 (red) density at 21 DPI (WT, nF = 3, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 2). g CAII (gray) density at 21 DPI (WT, nF = 3, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 2). Arrowheads highlight CAII+ cells. h MBP (gray) density at 21 DPI (WT, nF = 3, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 2). i IBA1 (green), Plp1 (gray) density at 21 DPI (WT, nF = 3, nM = 3; IFNAR1KO, nF = 4, nM = 2). a, d, h, f, i: two-tailed Student’s t-test; a: Irf7+IBA1+ density: Mann–Whitney test; b, c, e: two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc. Dotted lines outline lesions. Each point represents one animal, and data are presented as mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a source data file. nF = nFemale Mice and nM = nMale Mice.

ReAM appearance is delayed and more heterogeneous in middle-aged mice

Remyelination is delayed with age for people with MS and is recapitulated in middle-aged mouse models9,10,13,32. Remyelination declines largely due to impaired engulfment and trafficking of remyelination-inhibiting myelin debris9,69–71, however, it remains unknown whether this delay is due to impaired functioning of microglial states that carry out these functions. We used scRNAseq to compare microglial states present in middle-aged (10-month-old) mice with young (2-month-old) mice in the LPC model. We isolated F4/80+ myeloid cells from 2-month-old and 10-month-old C57BL/6 mice using FACS and sequenced samples at 7 and 21 DPI along with age-matched naïve controls (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5. The appearance of Ccl3 and Igf1 ReAM is delayed in middle-aged mice, but that of IRM and proliferative microglia is not.

a UMAP showing 38,592 microglia collected from young mice from naïve (nM = 10, pooled per sample), 7 DPI (nM = 20) and 21 DPI (nM = 22) and middle-aged mice from naïve (nM = 5), 7 DPI (nM = 10) and 21 DPI (nM = 10) conditions, resulting in (b) 13 clusters. c Proportion of each condition present in each microglial cluster identified in (b). d Differentially expressed genes used to define microglial states. e Representative images (scale bar = 10 μm) of lesions from Tmem119creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato mice with tdTomato (magenta) labeling microglia, mRNA probes for Igf1 (green) and Irf7 (gray). Quantification of (f) Igf1 positivity in tdTomato+ microglia and (g) Irf7 positivity in tdTomato+ microglia in young (3 DPI, nF = 0, nM = 5; 7 DPI, nF = 5, nM = 0; 21 DPI, nF = 3, nM = 2) and middle-aged (3 DPI, nF = 2, nM = 3; 7 DPI, nF = 2, nM = 3; 21 DPI, nF = 2, nM = 3) mice. h Quantification of Plp1 positivity in tdTomato+ microglia in young (3 DPI, nF = 0, nM = 4; 7 DPI, nF = 4, nM = 0; 21 DPI, nF = 2, nM = 2) and middle-aged (3 DPI, nF = 2, nM = 3; 7 DPI, nF = 2, nM = 3; 21 DPI, nF = 1, nM = 4) mice. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). i Representative images (scale bar = 100 μm) of lesions from middle-aged, C57BL/6 mice with MBP (gray) labeling myelin. j Rank order of MBP inside lesions in middle-aged (21 DPI, nM = 5; 45 DPI, nM = 5; 60 DPI, nM = 5) mice. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). k Quantification of Plp1 positivity in IBA1+ microglia present in middle-aged (21 DPI, nM = 5; 45 DPI, nM = 5; 60 DPI, nM = 5) mice. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All ANOVA were performed with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. Each point represents one animal, and data are presented as mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a source data file. nF = nFemale Mice and nM = nMale Mice.

Middle age did not result in additional age-specific microglial states, but rather increased the heterogeneity of states compared to young animals (Fig. 5b, c), as identified through the same gene expression pattern (Figs. 1j, 5d). Although Igf1 ReAM were more heterogeneous in middle-age and formed four clusters, in middle-aged mice, we found Igf1 and Ccl3 ReAM expanded from 7 to 21 DPI (proportion of microglia in these clusters went from 30.7% to 60.6%), unlike microglia from young mice which decreased from 19.2% to 7% from 7 to 21 DPI (Fig. 5c). Similar to young mice (Supplementary Fig. 2), the states found in middle-aged mice were also recapitulated in independent replicates (Supplementary Fig. 6). Tissue assessment of Igf1+ lesional microglia confirmed fewer Igf1 ReAM at 3 and 7 DPI, yet more at 21 DPI in middle-aged mice, suggesting a delayed maturation of this state with age (Fig. 5e, f). In contrast to these delays, we found IRM and proliferative microglia were enriched at 7 DPI in middle-aged compared to young mice (Fig. 5c, e, g). In agreement with the age-dependent delay in remyelination, the late remyelination-specific MTEM found in young mice were greatly reduced in middle-aged mice at 21 DPI (Fig. 5c, h). We next explored whether the maturation of MTEM coincided with delayed remyelination by investigating lesions of middle-aged mice at 21, 45 and 60 DPI. Remyelination increased from 21 to 45 DPI (Fig. 5i, j), accompanied by a delayed increase in MTEM at 45 DPI (Fig. 5k).

To confirm microglial heterogeneity at the protein level, we used high-dimensional flow cytometry with spinal cord tissue from naïve or LPC-injured C57BL/6 mice at 7 DPI and 21 DPI, from young and middle-aged mice. We clustered Cd45+Cd11b+Mrc1-Ly6c-Ly6g- microglia (Fig. 6a) after removing dead cells and doublets (Supplementary Fig. 7a). We used two or more proteins for each state to detect distinct subsets of microglia (Fig. 6b–i, Supplementary Fig. 7b–k). Using high-dimensional flow cytometry, we found we were not able to demarcate microglial states as clearly as with single-cell RNA sequencing. However, we could identify two Igf1 ReAM and homeostatic states as well as an IRM and an antigen-presenting (MHC-II) state. We found that Igf1 ReAM and IRM were predominantly present at 7 DPI in young mice and at both 7 DPI and 21 DPI in middle-aged mice (Fig. 6c), similar to the transcriptional states (Fig. 5). We also found that microglia isolated from naïve middle-aged mice were enriched within the MHC-II state compared to the HM state, consistent with a more reactive microglial state for middle-aged microglia (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6. Protein-level validation of microglial states during remyelination using high-dimensional flow cytometry.

a Representative scatterplot showing Ly6g+ neutrophils, Ly6c+ monocytes and Ly6c-Ly6g- microglia from Cd45+Mrc1-Cd11b+ cells. b Unsupervised clustering of 47,871 microglia and the (c) proportional contribution of each cluster isolated from d–f young, 2-month-old and g–i middle-aged, 10-month-old male mice from naïve (nyoung = 10, nmiddle-aged = 10), 7 DPI (nyoung = 8, nmiddle-aged = 12) and 21 DPI (nyoung = 10, nmiddle-aged = 12) conditions, respectively. j UMAP depicting the expression of Idh2—a protein involved in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. k Proportions of each sample (naïve (nyoung = 10, nmiddle-aged = 10), 7 DPI (nyoung = 8, nmiddle-aged = 12) and 21 DPI (nyoung = 10, nmiddle-aged = 12)) present in neutrophil and monocyte populations. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s post-hoc test. Each point represents two animals combined, and all data are presented as mean ± SEM. Metabolic pathway activity across (l) microglial states identified in (Fig. 1), throughout remyelination in (m) young mice and (n) young combined with middle-aged mice as a function of the genes found in the KEGG metabolic pathways. Source data are provided as a source data file.

Other phagocytic myeloid cells were also present during remyelination. With flow cytometry, we also identified monocytes (Cd45+Cd11b+Mrc1-Ly6g-Ly6c+) and neutrophils (Cd45+Cd11b+Mrc1-Ly6c-Ly6g+), which both increased by 21 DPI compared to naïve mice, more prominently in young mice (Fig. 6k). We then examined the scRNAseq data of these myeloid populations by isolating monocytes (based on Ly6c2, Chil3, Plac8, Ace, Ifit3 gene expression) and neutrophils (based on Camp, S100a8, Ly6g gene expression) and re-clustering these populations separately. We found both neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 8a–d) and monocytes (Supplementary Fig. 8e–h) were heterogeneous, with 11 neutrophil clusters (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b) and 7 monocyte clusters (Supplementary Fig. 8e, f). In middle-aged—but not young—mice, we found that monocytes shifted towards states enriched in proliferative genes (Mki67) and Ccr2 by 21 DPI (Supplementary Fig. 8g). Most neutrophils varied between Ly6g highCxcr2 low and Ly6g lowCxcr2 high populations, with pseudotime analysis suggesting that neutrophils Ly6g highCxcr2 low are more mature. Neutrophils from all clusters were found at higher levels by 21 DPI, compared to neutrophils isolated from naïve and 7 DPI mice (Supplementary Fig. 8c, d), suggesting that neutrophils continued to accumulate over time during remyelination for unknown reasons.

Overall, we found that aging results in a temporal dysregulation of microglial states, which is associated with delayed remyelination. The Igf1 ReAM, Ccl3 ReAM and MTEM states, but not IRM or proliferative microglia, were delayed and associated with the age-related delay in remyelination in middle-aged mice.

Changes in metabolic pathway activity and reactive oxygen species are largely restricted to proliferative microglia and Igf1 ReAM

Metabolic features can guide the transition of immune cells into distinct states72. To determine whether this was the case with young and middle-aged microglia, we used Landscape73—a metabolic pathway tool—to evaluate metabolic changes in ReAM. We found that Igf1 ReAM and proliferative microglia were the most metabolically active states, characterized by pathways related to phenylalanine metabolism, glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, glucosaminoglycan biosynthesis and alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism (Fig. 6l). Using high-dimensional flow cytometry, we confirmed that oxidative phosphorylation (Idh2) was elevated in both Igf1 ReAM and proliferative microglia (Fig. 6j). Correspondingly, overall metabolic activity decreased in young mice by 21 DPI when these states were no longer present (Fig. 6m) and remained sustained at 21 DPI in middle-aged mice as these states also persisted (Fig. 6n).

Aging and inflammation are also associated with greater production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and DNA damage74,75. We broadly assessed ROS production indirectly through malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation, in young and middle-aged mice. We found that MDA deposition was increased in middle-aged mice compared to young mice at 21 DPI but not at 3 or 7 DPI, in contrast to the metabolic changes (Fig. 6n). We further assessed ROS production using flow cytometry through CellROX (cellular ROS) and MitoSOX (mitochondrial ROS) intensity in microglia, Igf1 ReAM, OPC, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, endothelial cells, neutrophils and monocytes. Interestingly, not microglia, but young OPC, oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells, neutrophils and astrocytes increased mitochondrial ROS and young OPCs increased cellular ROS production at 21 DPI compared to middle-aged cells (Fig. 7c–k, Supplementary Fig. 7n–u).

Fig. 7. Lipid peroxidation is discordant with ROS production in middle-aged mice.

a Representative images (scale bar = 50 μm) of spinal cord lesions from Cx3cr1creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato mice with MDA (gray) showing lipid peroxidation in young (top) and middle-aged (bottom) mice at 21 DPI. b Quantification of the MDA present in lesions from Cx3cr1creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato (3 DPI, nM = 4; 7 DPI, nF = 1, nM = 4; 21 DPI, nF = 3, nM = 2) mice. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. c Representative flow cytometry plots of Cd11b+ microglia and CellROX intensity. Cells from 7 DPI (nyoung = 5, nmiddle-aged = 5) and 21 DPI (nyoung = 6, nmiddle-aged = 5) conditions were previously gated to include single cells based on forward scatter area and height then live cells based on live dead blue staining. Geometric mean intensity of CellROX in (d) microglia (Ly6c−Ly6g−Cd11b+), e Igf1 ReAM (Ly6c-Ly6g-Cd11b+Cd11c+), f OPC (Cd140a+), g astrocytes (Aqp4+) and MitoSOX in (h) microglia (Ly6c-Ly6g-Cd11b+), i Igf1 ReAM (Ly6c-Ly6g-Cd11b+Cd11c+), j OPC (Cd140a+), k astrocytes (Aqp4+) in young mice at 7 DPI (Dark blue) and 21 DPI (Dark Orange) and middle-aged mice at 7 DPI (Light blue) and 21 DPI (Light Orange). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. l Split violin plots showing the differences between the Naïve, 7 DPI and 21 DPI conditions isolated from young and middle-aged mice in the ROS producer score and ROS scavenger score. m UMAPs depicting the gene-weighted density estimation of ROS producer score and ROS scavenger score showing increased expression in Igf1 ReAM 1 and 2. n Heatmap of genes for ROS producer enzymes and ROS scavenger enzymes across HM, IRM, Ccl3 ReAM, Igf1 ReAM (1–4), MTEM and proliferative microglia shown in (o) describing increased expression in Igf1 ReAM 1 and 2. o UMAP describing microglia from young and middle-aged mice across naïve, 7 and 21 DPI as shown in Fig. 5a. Each point represents one animal, and all data are presented as mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a source data file. nF = nFemale Mice and nM = nMale Mice.

To understand whether microglia sequestered ROS in response to increased ROS production, we used previously classified ROS producing and scavenging enzyme genes76 to evaluate changes in ROS across microglia during remyelination in young and middle-aged mice. We found that microglia from middle-aged mice expressed greater levels of ROS producing enzyme genes, and also ROS scavenging enzyme genes, at 7 and 21 DPI compared to young mice (Fig. 7l). We then used gene-weighted density estimation of gene expression to determine which specific states contributed to changes in ROS in middle-aged mice (Fig. 7o). Igf1 ReAM (1 and 2) and proliferative microglia expressed the highest levels of ROS producing and ROS scavenging enzyme genes (Fig. 7l–n, Supplementary Fig. 7l, m).

Taken together, the delayed appearance of specific microglial states in middle-aged mice is reflected in unresolved metabolic activity. Lipid peroxidation increased at 21 DPI in middle-aged mice; however, cell-specific production of cellular and mitochondrial ROS is higher in cells from young mice. The discrepancy in ROS production and accumulation may be explained by heightened levels of both ROS producing and scavenging enzyme genes, which have a net impact of balancing global ROS output.

Igf1 ReAM are transcriptionally similar to microglia found in aged mouse brains and MTEM are present in MS shadow plaques

In recent years, several microglial states specific to aging and neurodegeneration have been identified21–24,28,31,35,76,77. We used hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes to compare microglial states specific to remyelination in young and middle-aged environments to the previously identified states in aged, 24-month-old mice28 and disease-associated microglia (DAM) present in APPNL-G-F mice, a model of Alzheimer’s disease78.

We identified four gene sets that distinguished microglial states during remyelination in young mice (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Gene sets one and two were characterized by homeostatic genes and gene sets three and four by reactive microglial genes. Igf1 ReAM formed the most distinct signature with limited expression of sets one and two, high expression of set three and modest expression of set four (Supplementary Fig. 9a, Supplementary Data. 1). Comparing microglia across conditions, young Igf1 ReAM were transcriptionally similar to the middle-aged Igf1 ReAM 1 (Supplementary Fig. 9b) and aged reactive white matter-associated microglia (RWAM)28 (Supplementary Fig. 9c), but not DAM or cuprizone-associated microglia (CAM) (Supplementary Fig. 9d,e). Interestingly, middle-aged Igf1 ReAM clusters were less comparable than young Igf1 ReAM were with aged RWAM and DAM clusters (Supplementary Fig. 9d).

To determine whether microglia in the LPC mouse model were similar to microglia in MS lesions, we trained a machine learning classifier to accurately identify Igf1 and Ccl3 ReAM, IRM, HM, and MTEM (Supplementary Fig. 10) in previously published single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNAseq) datasets of MS lesions79,80. We first applied the classifier to a dataset with 1815 microglia from chronic active and inactive MS lesions, and healthy controls79 (Fig. 8a). Here, we identified 149 and 24 Igf1 ReAM within chronic active and inactive MS lesions, respectively (Fig. 8b–d). We found lower proportions of IRM (0.44%) and Ccl3 ReAM (0.055%), potentially due to the transient nature of these states. Interestingly, the greatest proportion of microglia was identified as MTEM (73.2%) (Fig. 8b, d). Of note, not all cells classified as MTEM expressed the PLP1 myelin transcript (Fig. 8c), suggesting that the unbiased classification included genes in addition to those found inside myelin as this is likely a resolved microglial state.

Fig. 8. MTEM is present in shadow plaques and NAWM of MS brains.

a Unsupervised clustering of 1815 microglia isolated from chronic active and chronic inactive MS lesions along with healthy controls in a published dataset. b Unsupervised classification of HM, IRM, MTEM, Igf1 ReAM and Ccl3 ReAM identified from young mice during remyelination. A classifier was trained using SVMradial and avNNet machine learning models on the principal components used to cluster the mouse dataset and identified the HM, IRM, MTEM, Igf1 ReAM and Ccl3 ReAM states in the human MS dataset. c UMAP showing the expression level of PLP1 restricted to a portion of cells classified as MTEM in (b). d Proportion of classified microglial states present in each lesion type in (a). e Unsupervised clustering of 4137 microglia isolated from chronic active and chronic inactive MS lesion edges, lesion core, periplaque white matter, and control white matter in a published dataset. f Unsupervised classification of HM, IRM, MTEM, Igf1 ReAM and Ccl3 ReAM states as described in (b). g UMAP showing the expression level of PLP1 restricted to a portion of cells classified as MTEM in (f). h Proportion of classified microglial states present in each lesion type in (e). Representative images showing identification of MS lesions using (i) Luxol fast blue and PLP1 staining, where intense staining indicates NAWM (n = 5), lack of staining indicates a lesion and intermediate staining indicates a shadow plaque (n = 3). Further classification of shadow plaque as regions of intermediate, but distinct, BCAS1 staining (arrowheads) and classification of the identified lesion in (i) and (j) as inactive (n = 4) by lack of LN3 expression, or mixed (n = 1) by LN3 expression at the peripheries of the lesion. Lesions were collectively isolated from six brain regions isolated from five patients. Representative images of MS shadow plaque with PLP1 mRNA (white) and IBA1 (red) to identify IBA1+ microglia expressing PLP1 mRNA. j Quantification of PLP1 positivity in IBA1+ microglia. Each point represents one lesion, and all data are presented as mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a source data file.

We similarly assessed microglial states present in another MS snRNAseq dataset with 4137 microglia from the lesion core, periplaque white matter, chronic active and inactive lesion edge, and control white matter (Fig. 8e)80. Here, we found Igf1 ReAM mostly present in the chronic active lesion edge (Fig. 8f–h) while the majority of microglia (80.1%) were classified as MTEM, with low expression of the PLP1 myelin transcript (Fig. 8g). The PLP1 expression was high in microglia from the lesion edge, where remyelination is more common81.

As MTEM were the predominant state in both MS snRNAseq datasets, we examined the spatial distribution of PLP1-expressing MTEM in post-mortem MS brains. We classified lesions as mixed, inactive, or as a shadow plaque, a biomarker of remyelination. These lesions were compared to normal appearing white matter (NAWM) (Fig. 8i). We differentiated between mixed and inactive lesions based on LN3 and PLP1 immunoreactivity and defined shadow plaques based on intermediate luxol fast blue staining with BCAS1 positivity (Fig. 8i). We identified MTEM as IBA1+ microglia and macrophages containing PLP1 mRNA. We found that PLP1+ IBA1+ cells were largely present in shadow plaques and NAWM (10% of microglia) and were negligible within mixed and inactive lesions (Fig. 8j). The presence of PLP1 in a population of microglia and macrophages is consistent with the idea that microglia may prune myelin in people with MS.

Discussion

Here, we used scRNAseq to track the microglial response during remyelination. Using trajectory mapping, we found that primed microglia transitioned into one of four major states during the early stages of remyelination: IRM, Ccl3 ReAM, proliferative microglia and Igf1 ReAM. The microglial response coalesced into MTEM during late remyelination, which is a likely resolved microglial state associated with myelin pruning. Notably, certain microglial states (Ccl3 ReAM, Igf1 ReAM, MTEM) were delayed with age, which coincided with delayed remyelination in aging animals9,10,69,71,82. Interestingly, MTEM was a common microglial state in snRNAseq of human MS autopsy tissue and was found predominantly in shadow plaques, consistent with being a state defining remyelination in mice.

In recent work, we and others have begun to dissect what may promote microglial transitions. We find that cultured primary murine microglia express a marker of cuprizone-associated microglial state—reminiscent of DAM—by exposure to both myelin debris and necrotic oligodendrocyte carcasses76. Similarly, exposure of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) human microglia to myelin debris, amyloid beta, apoptotic neurons, or synaptosomes induces a transition to DAM and is dependent upon transcription factor MITF83. It may be that the state changes we observed in early remyelination reflect similar pathways—primed microglia contact myelin or oligodendrocyte debris, and the ensuing response prompts a change in transcriptional state. Future work will need to define how such demyelination signals prompt such multi-faceted microglial responses. The Igf1 ReAM also upregulate Trem2, a mediator of transition to the protective DAM state in several models of neurodegeneration77,84–86. In culture, Trem2 increases phagocytosis of myelin by binding lipids present in myelin, galactosylceramide and sulfatide85,87, which may be a mechanism employed by Igf1 ReAM to induce the uptake of myelin debris. Consistent with a role for ReAM clearing myelin debris, we found that these states upregulated various metabolic pathways. Microglia broadly increase metabolic pathways as a result of phagocytosis88. Indeed, where myelin clearance is delayed in middle-aged mice9,69–71, so too do we find a delay in Ccl3 ReAM and Igf1 ReAM states. Future work will need to define how neurodegenerative signals like myelin debris cause this multifaceted microglial response and how to accelerate the maturation into Ccl3 ReAM and Igf1 ReAM states.

Here we found IRM during remyelination to complement our previous finding that IRM are present following demyelination21. Here, we also found that IRM were present one week after demyelination in young and middle-aged mice. During remyelination, we found IRM are induced by type I interferons, which are required for remyelination. IRM also appear in development89, a tau model90 and amyloid producing mouse models of neurodegeneration78, post-mortem samples from patients with Alzheimer’s disease68,90, and during aging91. Interestingly, the mechanisms that lead to IRM may be context dependent. Both RIG1-MAVS sensing of double stranded RNA in engulfed neurons89 and STING activation by mitochondrial DNA leakage90 can induce IRM in development and a tau model, respectively. However, it remains unclear what triggers IRM after demyelination. Considering the conserved IRM response, this state may govern microglial responses to pronounced environmental changes. In the context of our work, IRM facilitate OPC recruitment and oligodendrocyte maturation, potentially by bolstering microglial recruitment via Cxcl10, an identified microglial chemoattractant, following demyelination92.

During late remyelination, MTEM upregulated gene expression patterns similar to homeostatic microglia, suggesting a partial resolution of the microglial response. Though initially surprising that microglia contained myelin transcripts in late remyelination (MTEM), but not in earlier stages characterized by myelin debris phagocytosis, a few potential explanations may exist for such a phenomenon. As LPC induces lytic cell death within the lesion site38, myelin RNA could be rapidly degraded upon release from the degrading myelin93, resulting in a lack of myelin RNA in consumed debris during early remyelination. In contrast, the pruning of newly laid myelin could lead to the presence of myelin transcripts within microglia—as occurs in development24,55,56—and may be analogous to the presence of neuronal transcripts within microglia following developmental neuronal engulfment89. Whether the presence of these myelin transcripts alters microglial function remains unclear. Additionally, while MTEM are present in MS brains, the transcriptional similarity between MTEM and HM leads to limitations when utilizing unbiased tools to differentiate between these populations. Further supervised identification through manual gene comparisons or partially supervised identification through algorithms using a defined gene list may mitigate misclassifications.

How does age impact the initial damage following LPC and, thus, the subsequent microglial response? LPC is a lipid-disrupting agent that kills cells rapidly and is cleared quickly38. Following this initial damage and clearance, middle-aged mice—but not young mice—have lesion expansion in the first 72 h after LPC injection94. Age-related lesion expansion was associated with more microglial NADPH oxidase and was reversed with a ROS-lowering medication, indapamide94, suggesting that the microglial response in middle-aged mice is not different due to more primary damage, but instead, the initial microglial response is more damaging. Is the disrupted microglial response in middle-aged mice due to intrinsic or environmental differences? While the microglial response to LPC in middle-aged mice is “primed” and more damaging94,95, a recent explanation for this “primed” response is that microglia lose the ability to mount a precisely adjusted immune response96. In this regard, microglia become more rigid as a result of aging. Microglia have epigenetic changes that cause them to respond more ineffectively during remyelination, which can be reversed with innate training96. However, environmental cues likely also impact these microglial epigenetic age-related microglial changes. The contribution of how the aging CNS environment impacts microglial rigidity is an exciting question for future research. Overall, the pronounced damage and debris of the lesion environment promote microglial transitions into several states throughout remyelination. The restriction of microglial states to early (Igf1 ReAM, Ccl3 ReAM, IRM) and late (MTEM) remyelination suggests specialized functions that govern the entirety of the remyelination promoting microglial response.

Through scRNAseq of microglia during remyelination in the LPC mouse model, we determined that early stages of remyelination were characterized by a multi-faceted response associated with increased metabolic activity, cytokine production and lipid processing. This response coalesced into MTEM—a resolved and bioinformatically identified terminal state of microglial transition that pruned newly-laid myelin in vivo. Interestingly, middle-aged microglia did not display age-specific states but rather an increase in heterogeneity and delay in appearance of existing states. We also identified HM, Igf1 and Ccl3 ReAM, IRM and MTEM in human MS snRNAseq datasets but, surprisingly, MTEM predominated. Furthermore, we found MTEM enriched in shadow plaques in human MS brain. These findings may be expanded on to develop therapies for MS through specific targeting of microglial states.

Methods

Mouse models of MS and MS patients

Mice

All work was reviewed and approved by animal use subcommittees at the University of Alberta under the animal use protocol 2605 and all animal experiments were conducted in accordance with procedures that were reviewed and approved by animal subcommittees at the University of Alberta and University of British Columbia (for PDGFRαCreERT2; Rosa26mGFP mice39). Young, 2-month-old (Charles River Canada, Cat. No. 027) and middle-aged, 10-month-old (Charles River Canada, Cat. No. 701) male C57BL/6 mice were used for the flow cytometry (single-cell RNA sequencing validation - nyoung = 26, nmiddle-aged = 34; metabolic activity assay - nyoung = 24 and nmiddle-aged = 24) and single-cell RNA sequencing experiments (replicate 1 - nyoung = 42; replicate 2 - nyoung = 25 and nmiddle-aged = 25, replicate 3 - nyoung = 24 and nmiddle-aged = 24). Here, nF is the number of female mice and nM is the number of male mice. Mice were housed in the University of Alberta animal facility and habituated for one week prior to lysolecithin (LPC) injections. Tmem119creERT2 (The Jackson Laboratory, Cat. No. 031820), Cx3cr1creERT2 (The Jackson Laboratory, Cat. No. 021160) and Rosa26tdTomato (The Jackson Laboratory, Cat. No. 007909) mice were also used for the single cell RNA sequencing experiments and RNAscope assays. Tmem119creERT2 and Cx3cr1creERT2 mice were crossed with Rosa26tdTomato and were bred in the University of Alberta animal facility. The genotype of all mice was confirmed by Transnetyx® via real-time PCR. Young, 2-month-old Cx3cr1creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato mice (nF = 3, nM = 2) were used for the single-cell RNA sequencing experiments and Tmem119creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato mice (nyoung (F) = 14, nyoung (M) = 13, nmiddle-aged (F) = 11, nmiddle-aged (M) = 19), Cx3cr1creERT2; Rosa26tdTomato mice (nyoung (F) = 4, nyoung (M) = 10, nmiddle-aged (F) = 9, nmiddle-aged (M) = 6) were used for lipid peroxidation assay, Mx1cre; Rosa26YFP mice (nyoung (F) = 6, nyoung (M) = 8) and C57BL/6 mice (nmiddle-aged (M) = 15) were used for the RNAscope assays. Cx3cr1creERT2 mice were crossed with Rosa26iDTR mice and the resulting Cx3cr1CreERT2+/−; ROSA26iDTR- mice (nF = 1) were used for the electron microscopy experiment. Young, 2-3-month-old C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Canada, Cat. No. 027) (nF = 7, nM = 6) and B6(Cg)-Ifnar1tm1.2Ees/J (The Jackson Laboratory, Cat. No. 028288, RRID:IMSR_JAX:028288) (nF = 8, nM = 6) were used for RNAscope assays and immunohistochemistry. For cell culture experiments, CD-1® IGS mice (Charles River Canada, Cat. No. 022) were used. All mice were housed in the University of Alberta animal facility under 12 h light-dark cycles, 20–24 °C and 40–70% humidity.

Injections

Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. T5648) was dissolved in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. C8267) to achieve a concentration of 20 mg/mL. All transgenic pups were injected with 0.05 mL tamoxifen intraperitoneally for three consecutive days beginning at postnatal day (P) 13. Cx3Cr1CreERT2+/−; ROSA26iDTR- mice were injected daily intraperitoneally with a solution of diphtheria toxin (Cedarlane, Cat. No. 150(LB)) in 0.01 M PBS at a dose of 11.12–16.67 ng/g, from 8–20 days after injection.

Lysolecithin (LPC) model of MS

Two-month and 10-month-old mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal cocktail injection of ketamine (Western drug distribution centre, Cat. No. 109585, 100 mg/kg) and xylazine (Rompun, Cat. No. 02169592, 5 mg/kg) dissolved in 0.9% saline. Once the mouse reached the surgical plane of anesthesia, the fur was trimmed, the skin was disinfected with 10% chlorhexidine digluconate (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. C9394) and the eyes were sealed with lubricant (Western Drug Distribution Centre, Cat. No. 135726). The mouse was then placed on a stereotaxic frame where the long spinous process of T2 was used as a landmark and an incision was made in the dura mater between the thoracic vertebrae, T3 to T4. 0.5 μL (Sigma-Aldrich, L1381, 1% in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS)) or 0.7 µL (Sigma-Aldrich, L4129, 1% in 0.1 M PBS) LPC was injected at an angle of 10° and a depth of 1.3 mm from the midline between the dorsal columns, into the ventral funiculus of the spinal cord at the rate of 0.25 μL/min. Sham controls were injected with an equivalent volume of PBS. Following injection, the skin and underlying connective tissue were sutured (Vycril type IV curved, tapered, Ethicon, Cat. No. J304H). Post-operatively, the mice were subcutaneously given slow-release buprenorphine (0.5 mg/kg) for pain, 0.9% saline for hydration and atipamezole (1.67 mg/kg, Revertor, Cat. No. 02337207) to arouse the mice from sedation while they recovered on heating pads. The mice were monitored for one week following recovery or the experimental endpoint, whichever came first.

Brain tissue from human MS patients

For all experiments with human tissue, we adhered to the Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity and the Declaration of Helsinki, with consent obtained prior to death and protocol approval by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Amsterdam UMC. We received formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded brain sections from the Netherlands Brain Bank through collaboration with Dr. Geert Schenk. A total of 12 brain tissue blocks containing white matter from one relapsing remitting and nine progressive MS cases (Supplementary Table 1) were collected in collaboration with the Netherlands Brain Bank (https://www.brainbank.nl/). The average MS disease duration was 27.5 years (ranging from 16 to 43 years) and the average post-mortem delay was 279 min (ranging from 150 to 365 min). The tissue selection and dissection were guided by post-mortem MRI as described previously97. Before death, the subjects, or their next of kin, provided written, informed consent for the use of their tissue and clinical information for research purposes to the Netherlands Brain Bank. For each case, the selected tissue blocks were paraffin-embedded, sliced into 10 µm sections and mounted on glass slides.

Flow cytometry

Spinal cord isolation

LPC-lesioned and naïve mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.4 mL 1% Neutral Red98 (Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. N129-25) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, (sodium phosphate dibasic anhydrous; Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 374-1 and sodium dihydrogen phosphate monohydrate; Anachemia, Cat. No. 10049-21-5 in water) 2 h prior to euthanasia. Mice were euthanized with an intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 mL Dorminal (Rafter Products, DIN 02333708) and transcardially perfused with 20 mL ice-cold Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; Gibco, Cat. No. 14175-079). The spinal cords were dissected, and the lesions were isolated based on visual identification through neutral red staining. Comparable segments of whole spinal cords were isolated as control tissue from naïve mice. Tissue from two mice was pooled per sample, finely micro-dissected on ice in ice-cold HBSS and then transferred to a tube with 1.5 mL Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Cat. No. 11960-044) for mechanical dissociation via five oscillations of a loose-fitting dounce. The cells were sequentially filtered through 70 μm and 40 μm filters and washed with 7.5 mL DMEM after each filtration step.

Debris removal

The cells were pelleted (300 G, 10 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in 6.2 mL HBSS and 1.8 mL Debris Removal Solution (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat. No. 130-109-398). The suspension was mixed by inverting the tube five times, and 4 mL of HBSS was carefully overlaid. The suspension was centrifuged (3000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C), the top two layers were aspirated and topped up to 15 mL with HBSS. The suspension was mixed by inverting the tube 5 times and pelleted (1000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C).

Extracellular staining

The pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of CD16/32 antibody (1:100, eBiosciences, Cat. No. 14-0161-82) and HBSS solution for 20 min on ice and centrifuged (300 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). The pellet was resuspended for 20 min in 200 μL of extracellular stain cocktail containing HBSS, 10 μL BD Brilliant Stain Buffer Plus (BD Biosciences, Cat. No. 566385) and the following antibodies in a 1:100 dilution: Brilliant Violet 421 CD11b Antibody (Clone M1/70, BioLegend, Cat. No. 101236), PE/Cyanine5 CD45 Antibody (Clone 30-F11, BioLegend, Cat. No. 103110), Brilliant Violet 510 Ly-6C Antibody (Clone HK1.4, BioLegend, Cat. No. 128033), Brilliant Violet 785 Ly-6G Antibody (Clone 1A8, BioLegend, Cat. No. 127645), Brilliant Violet 650 I-A/I-E Antibody (Clone M5/114.15.2, BioLegend, Cat. No. 107641), Brilliant Violet 605 CD11c Antibody (Clone N418, BioLegend, Cat. No. 117334), PE AQP4 Antibody (Clone B-5, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Cat. No. sc-390488), PE/Cyanine7 CD140a Antibody (Clone APA5, BioLegend, Cat. No. 135912), Alexa Fluor 700 O1 Antibody (Clone O1, R&D Systems, Cat. No. FAB1327N), PE/Dazzle 594 Anti-mouse CD31 Antibody (Clone MEC13.3, Biolegend, Cat. No. 102526). Isotype controls were resuspended for 20 min in 200 μL of single isotype controls at 1:100 dilution in HBSS: Brilliant Violet 421 Rat IgG2b, κ Isotype Control Antibody (Clone RTK4530, BioLegend, Cat. No. 400640), PE/Cyanine5 Rat IgG2b, κ Isotype Control Antibody (Clone RTK4530, BioLegend, Cat. No.400610), Brilliant Violet 785 Rat IgG2a, κ Isotype Control Antibody (Clone RTK2758, Biolegend, Cat. No. 400545), Brilliant Violet 650 Rat IgG2b, κ Isotype Control Antibody (Clone RTK4530, BioLegend, Cat. No. 400651), Brilliant Violet 605 Armenian Hamster IgG Isotype Control Antibody (Clone HTK888, BioLegend, Cat. No. 400943), PE/Cyanine7 Rat IgG2a, κ Isotype Ctrl Antibody (Clone RTK2758, Biolegend, Cat. No. 400522). The bead reference controls were prepared by combining 1 drop of positive beads (AbC Total Antibody Compensation Bead Kit; Invitrogen, Cat. No. A10497) and 1 μL of each antibody listed in the extracellular stain cocktail. The reference controls were also incubated for 20 min. All pellets were washed with 2 mL HBSS and centrifuged (300 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). Following extracellular staining, cells were either stained with CellROX Deep Red and MitoSOX Green or stained with intracellular markers.

CellROX and MitoSOX staining

CellROX Deep Red (500 nM; Invitrogen Cat. No. C10491) and MitoSOX Green (1 μM; Invitrogen, Cat. No. M36006) were added to the cell suspension for 25 min and the samples were analyzed on the Cytek Aurora analyzer at the University of Alberta Flow Cytometry Core without washing.

Intracellular staining

The pellets were resuspended in 200 μL of 1% paraformaldehyde (Millipore Sigma, Cat. No. 441244-3KG) in 0.1 M PB for 10 min at room temperature and centrifuged (500 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). The pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of True Nuclear 1x Perm Buffer (BioLegend, Cat. No. 424401) and immediately centrifuged (600 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). This permeabilization step was performed twice. The pellet was resuspended for 40 min in 200 μL of intracellular stain cocktail containing HBSS, 10 μL of BD Brilliant Stain Buffer (BD Biosciences, Cat. No. 566385) and the following antibodies at a 1:100 dilution: Alexa Fluor 647 GAPDH Antibody (#3907, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. No. 3907S), Alexa Fluor 700 Ki-67 Antibody (Clone 16A8, BioLegend, Cat. No. 652420), Alexa Fluor 488 IRF7 Antibody (Bioss, Cat. No. BS-3196R-A488), APC-eFluor 780 CD68 Antibody, (FA-11, eBioscience, Cat. No. 47-0681-82), DyLight 350 IGF-I/IGF-1 Antibody (Novus Biologicals, Cat. No. NBP2-48001UV), DyLight 594 IDH2 Antibody (Novus Biologicals, Cat. No. NBP2-22166DL594), Brilliant Violet 711™ CD206 Antibody (Clone C068C2, BioLegend, Cat. No. 141727), PE Osteopontin Antibody (R&D Systems, Cat. No. IC808P), PE/Cyanine7 Phospho STAT1 Antibody (Clone A15158B, BioLegend, Cat. No. 686408), PerCP-eFluor™ 710 Ccl3 Antibody (eBioscience, Cat. No. 46-7532-82) and centrifuged (600 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). The pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of True Nuclear 1x Perm Buffer, immediately centrifuged (600 × g, 5 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in 200 μL of HBSS. The bead reference controls were prepared by combining 1 drop of positive beads (AbC Total Antibody Compensation Bead Kit; Invitrogen, Cat. No. A10497). Isotype controls were resuspended for 40 min in 200 μL of single isotype controls at 1:100 dilution in HBSS: Alexa Fluor 647 Rabbit IgG Isotype Control Antibody (#3452, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. No. 3452S), Alexa Fluor 700 Rat IgG2a, κ Isotype Control Antibody (Clone RTK2758, BioLegend, Cat. No. 400528), Alexa Fluor 488 Rabbit IgG Isotype Control Antibody (Bioss, Cat. No. BS-0295P-A488), APC-eFluor 780 Rat IgG2a kappa Isotype Control Antibody (eBioscience, Cat. No. 47-4321-82), DyLight 350 Mouse IgG1 Kappa Isotype Control Antibody (Novus Biologicals, Cat. No. NBP1- 43319UV-0.5 ml), DyLight 594 Rabbit IgG Isotype Control Antibody (Novus Biologicals, Cat. No. NBP2-24891DL594), Brilliant Violet 711 Rat IgG2a, κ Isotype Control Antibody (Clone RTK2758, BioLegend, Cat. No. 400551), PE Goat IgG Antibody (R&D Systems, Cat. No. IC808P), PE/Cyanine7 Mouse IgG1, κ Isotype Control Antibody (Clone MOPC-21, BioLegend, Cat. No. 400126), PerCP-eFluor 710 Rat IgG2a kappa Isotype Control Antibody (eBioscience, Cat. No. 46-4321-82). The bead reference controls were prepared by combining 1 drop of positive beads (AbC Total Antibody Compensation Bead Kit; Invitrogen, Cat. No. A10497). All pellets were washed with 2 mL of HBSS, centrifuged (300 × g, 5 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in 200 μL of HBSS. The samples were analyzed on the Cytek Aurora at the University of Alberta Flow Cytometry Core.

Gating and clustering

All flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo (v.10.9.0). Doublets were excluded through the forward scatter and side scatter exclusion. For the ROS assessment: live (Live Dead blue-) cells were gated for microglia (Ly6g-Ly6g-CD11b+), Igf1 ReAM (Ly6g-Ly6g-CD11b+CD11c+), OPC (CD140a+), neutrophils (Ly6g+), monocytes (Ly6c+), oligodendrocytes (O1+) and endothelial cells (CD31+) and the geometric median fluorescence of CellROX and MitoSOX was calculated in FlowJo (v.10.9.0). For the scRNAseq validation: All CD206-CD11b+ cells were classified as either microglia, monocytes, or neutrophils. Specifically, CD206-CD11b+Ly6g-Ly6c+ cells were identified as monocytes, CD206-CD11b+Ly6g+Ly6c- cells were identified as neutrophils and CD206-CD11b+Ly6g-Ly6c- cells as microglia. The microglia were concatenated using the DownSample PlugIn (v.3.3.1), including all microglia per sample if the cell counts were under 2000 or down-sampled to 2000 if the cell counts were greater than 2000. The concatenated sample was clustered using the XShift plugin (v1.4.1) and the geometric median fluorescence values were plotted on a heatmap in FlowJo (v.10.9.0).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

The spinal cord tissue was processed as described above (see Flow cytometry—Spinal cord isolation, Debris removal, and Extracellular staining) with 10 LPC-injected spinal cord lesions pooled per sample. The spinal cords were labeled with Zombie AquaTM Fixable Viability Kit (BioLegend, Cat. No. 423102), DRAQ5TM Fluorescent probe solution (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat. No. 62254) and FITC anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (Clone BM8; BioLegend, Cat. No. 123107) and sorted on the flow cytometry cell sorter (BD FACSAria III) at the University of Alberta Flow Cytometry Core. The Zombie Aqua-DRAQ5+F4/80+ cells were isolated and cell counts were manually confirmed using a hemocytometer.

Single-cell RNA sequencing

Interactive web applications of the dataset shown in Fig. 1 (downsampled to 3000 cells/time point) can be found at: https://sameerazia.shinyapps.io/shinyapp_v2/_w_730c72065ad64e898c6f7a91c005cebe/ and the dataset shown in Fig. 5 (downsampled to 2500 cells/time point) can be found at: https://sameerazia.shinyapps.io/shinyapp/_w_c5cf2dbd78bb4130bd816f0c4f92d80b/.

Library preparation

The FACS-isolated cells (see Flow cytometry—Fluorescence-activated cell sorting) were processed on the 10x chromium controller following the 10x Genomics Next GEM Single Cell 3′ GEM, library, and Gel Bead kit v3.1 (10x Genomics; Cat. No. 1000121). Samples were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq P150 sequencer at Novogene Corporation Inc. The samples were paired-end, single-index sequenced at an average read depth of 50,000 reads per cell. The resulting BCL files were demultiplexed into FASTQ files and aligned to a custom Mus Musculus 10 (MM10) reference genome adjusted to include Clec7a, a polymorphic pseudogene. The Clec7a annotation was added to the 10x Genomics pre-built MM10 genome (2020-A) GTF file from the 10x Genomics parent GTF file (gencode.vM23.primary_assembly.annotation.gtf.gz). The custom genome was created by combining the MM10 genome (2020-A) FASTA file with the Clec7a modified GTF file using the cellranger mkref function in the 10x cell ranger pipeline (v3.0.0). Finally, the samples were aligned to a custom genome using the cellranger count function to generate barcoded and sparse matrices, both raw and filtered, along with BAM files for downstream analyses.

Quality control, dimensionality reduction and clustering

Quality control, dimensionality reduction and initial clustering were performed in the R statistical environment (v4.1.2) using Seurat99,100 (v5.0; https://github.com/satijalab/seurat). One Seurat object was created per dataset to include genes expressed in a minimum of three cells and cells expressing a minimum of 200 genes using the CreateSeuratObject() function. The object was further refined to exclude doublets and multiplets by removing cells with high gene counts (>3000 genes) and dead cells by removing cells with high percentages of mitochondrial genes (>10%). All datasets were merged using the merge() function and normalized using the SCTransform() function according to the binomial regression model101 (Highly variable features = 3000, nCount and mitochondrial genes regressed).

Dimensionality reduction was performed using RunPCA(), FindNeighbors() (Dimensions = 15) and FindClusters() functions. Twenty-five principal components were used for downstream analyses as determined by the PCA elbow plot. The FindClusters() function was run at multiple resolutions, ranging from 0 to 1, separated by 0.1. All clustering resolutions (0 to 1) were plotted on a tree generated by the Clustree package102 using the clustree() function. The 0.5 resolution was chosen for clustering based on the most stable level as identified by clustree().

The final clustering of the dataset was performed in a Jupyter notebook (v6.0.3) running a python environment (Python 3.8.3) and using the Single Cell Clustering Assessment Framework (SCCAF) package103 (v0.0.10, https://github.com/SCCAF/sccaf). The SeuratObject was converted to an h5ad file using SeuratDisk by first converting the RDS file to an h5Seurat file using the Saveh5Seurat() and converting the h5Seurat file to an h5ad file using the convert() function (Destination = h5ad). The h5ad file was read into the python environment using Scanpy (v1.6.0)104. The clustering was refined using the SCCAF_optimize_all() function (minimum accuracy = 95%, iterations = 150). The machine learning algorithm iteratively clustered the dataset until a 95% self-projection accuracy was reached. The final clustering iteration was projected onto a UMAP using the sc.pl.umap() function. To avoid overclustering, we used Clustree and SCCAF to establish our resolution. However, these tools still favored overclustering with our set resolution. To account for overclustering we used expert opinion to label distinct microglia states with names and then stratified subsequent microglial clusters for a given microglia state by number. For example, homeostatic cluster with several homeostatic clusters (HM) they would be HM1, HM2, etc. States common to both injured and uninjured conditions were classified as transitioning microglia (TM), as described by others105. States enriched in translation-related genes but not other markers of microglial reactivity, as identified by others28, were classified as primed microglia (PM). For single-cell bar graphs, each library was downsampled to the cell numbers of the library with the lowest cell counts by multiplying the cell numbers in each cluster for any given library with the proportion of library with the lowest cell counts. The percentage of each library was calculated by dividing the new downsampled cluster value for each library by the total number of cells in the library.

Gene set comparisons

Gene sets were calculated in Seurat by comparing the datasets where mice were given LPC to those that were not, i.e., datasets collected from young mice at 7, 14 and 21 days post LPC injection (DPI) to naïve and sham controls28,76. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the LPC and non-LPC groups were calculated using the FindAllMarkers() function (only.pos = FALSE, min.pct = 0.25, min.threshold = 0.25) on the SCTransformed assay. One-hundred twenty-five DEGs (p < 0.05) were retained and were clustered using the R stats package (v4.1.2). The Euclidean distance between the DEGs was calculated using the dist() function and the DEGs were clustered using the Ward’s method in the hclust() function (method = ward.D2). The clustered branches were divided into four gene sets using the cutree() function and the average gene expression values were plotted in Seurat using the DoHeatmap() function.

Functional Gene Ontology pathway analysis

The gProfiler106 web server (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/gost) was used to identify functional Gene Ontology pathways based on overlap of cluster-specific DEGs, as identified using FindAllMarkers() function (only.pos = FALSE, min.pct = 0.25, min.threshold = 0.25), with the gene ontology (molecular function, cellular component and biological processes), KEGG and REACTOME databases. Pathways with a p-value < 0.05 were plotted on an alluvial plot using the ggalluvial package (v0.12.3) based on the number of genes intersecting with the total genes present in the pathways. The genes associated with each pathway were averaged and the kernel density was plotted using the plot_density function of the Nebulosa package107 (v1.4.0).

Gene regulatory network analysis