Abstract

H+-ATPase is a P-type ATPase that transports protons across membranes using the energy from ATP hydrolysis. This hydrolysis is coupled to a conformational change between states of the protein, in which the proton-binding site is alternately accessible to the two sides of the membrane with an altered affinity. When isolated from Neurospora crassa, H+-ATPase is a 600 kDa hexamer of identical 100 kDa polypeptides. We have obtained the three-dimensional structures of both ligand-free and Mg2+/ADP-bound states of this complex using single-particle electron cryo- microscopy. Structural comparisons, together with the difference map, indicate that there is a rearrangement of the cytoplasmic domain on Mg2+/ADP binding, which consists of a movement of mass towards the 6-fold axis causing the structure to become more compact, accompanied by a modest conformational change in the transmembrane domain.

Keywords: ATPase/conformational change/cryo-EM/electron microscopy/proton pump

Introduction

Cells have evolved a mechanism for the generation of membrane potential by ion translocation using the free energy released by ATP hydrolysis. This membrane potential can then be used by the cell for secondary ion and nutrient transport. The enzymes involved in the primary active transport are ATPases and are embedded in the cell plasma membranes. Of particular interest in this process is how the ATPases cyclically translocate ions through the membrane against the concentration gradient. Jardetzky proposed a very simple model, which is still useful, in which a binding site for the ions alternates between high and low affinity at the same time as it changes its connectivity to the two sides of the membrane. The binding or hydrolysis of ATP triggers a structural change between the two states (Jardetzky, 1966). The term E1 has often been used to identify the conformational state of the enzyme in which the ion-binding site faces the cytoplasm with high affinity, and the E2 form for that in which the site faces outside the cell with low affinity.

The Neurospora plasma membrane H+-ATPase belongs to the family of P-type ATPases. The P-type ATPases share the characteristic feature of having an aspartyl-phosphate intermediate state (Bastide et al., 1973; Dame and Scarborough, 1980). P-type ATPases can be active as monomers (Goormaghtigh et al., 1986) and are made up of several functional domains (MacLennan et al., 1985; Toyoshima et al., 2000). From the conservation of the amino acid sequences responsible for the nucleotide binding and autophosphorylation (Shull et al., 1985; Addison, 1986), it is thought that the basic mechanism for coupling of ion transport to ATP hydrolysis may be common throughout the family. Three of the most studied members are referred to as H+-ATPase, Na+,K+-ATPase, or Ca2+-ATPase, according to the selectivity for the ions to be pumped.

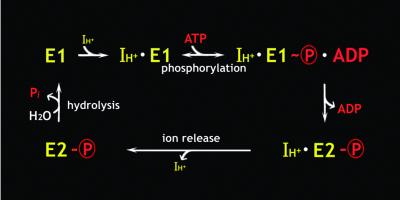

On the basis of the kinetic data obtained, mostly for the Na+,K+-ATPase or Ca2+-ATPase, it has been proposed that the ion translocation takes place as a consequence of the transition of the E1∼P to the E2-P state (Figure 1). E1∼P is a phosphoenzyme intermediate that has a high affinity ion-binding site and readily phosphorylates ADP, whereas E2-P has low affinity ion-binding sites, accessible on the other side of the membrane, and more readily reacts with water. Whether the molecular mechanism of the E1∼P to E2-P transition involves communication of a large conformational change over a long distance between the phosphorylation and ion-binding sites (i.e. an allosteric change), as has been widely hypothesized, is not yet proven. In support of this notion, a recent crystal structure has shown that the phosphorylation site is located in the bulky cytoplasmic region with a rather distant separation from both the nucleotide-binding domain and the transmembrane helix region in which the ion-binding sites are located (Toyoshima et al., 2000). However, little is known about the precise overall mechanism of communication between the membrane and cytoplasmic domains.

Fig. 1. Simplified diagram for the enzymatic cycle of the proton pump coupled to ATP-hydrolysis. H+-ATPases are thought to have two ion (IH+) access conformations (E1 and E2) regardless of the ligand binding, of which E1 takes up the ion in the cytoplasm while E2 releases it to the other side of the membrane, as marked in yellow. Substrate (red) induces the acyl-phosphate intermediate state E1∼P, which releases ADP before becoming E2-P, which is subsequently hydrolyzed.

Circular dichroism estimation of the secondary structure of the H+-ATPase shows negligible change (Hennessey and Scarborough, 1988), while hydrogen/deuterium exchange experiments show significant tertiary structural changes of the H+-ATPase on binding of substrate analogues such as Mg2+/ADP, supporting the idea that structural changes might occur at a domain level (Goormaghtigh et al., 1994). In general, one might expect two types of structural change. The first might occur as a direct result of binding of nucleotide, and the second after phosphorylation and nucleotide release associated with the change in ion-binding affinity and accessibility. Hypotheses based on the crystal structure of the SERCA (Ca2+ pumps from sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticula) Ca2+-ATPase in the Ca2+-bound state have suggested that an enormous structural change involving the actuator domain (90° rotation), the nucleotide-binding domain (25–50 Å translation) and the phosphorylation domain (53° rotation) is needed during the E1 to E2 transition (Toyoshima et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2002). However, a direct determination of the sequence of conformational changes of a P-type ATPase during the catalytic cycle, and the mechanism used to convert free energy into a conformational change in the phosphoenzyme to alternate its ion access site, remains to be established.

We have used single-particle electron cryo-microscopy to reconstruct the solution structures of the H+-ATPase hexamer in two conformational states, one of which is close to E1 (ligand free) and the other close to E1∼P·ADP (Figure 1). Earlier work had indicated that the structures we have examined have the largest difference in structure (Goormaghtigh et al., 1994). The comparison of their three-dimensional (3D) structures, together with the difference map, provides unequivocal evidence that upon binding of Mg2+/ADP the cytoplasmic domain undergoes a significant conformational change accompanied by a modest outward movement of the membrane domain with respect to the 6-fold axis. Overall, the structural rearrangement on nucleotide binding leads the enzyme to be more tightly packed. Since the structural change we have observed may be the largest in the H+-ATPase catalytic cycle, the key structural changes between E1 and E2, which underlie the change in ion-binding affinity and accessibility, may not be as large as the work on Ca2+-ATPase suggests.

Results and discussion

Electron cryo-microscopy of H+-ATPase hexamer in two states

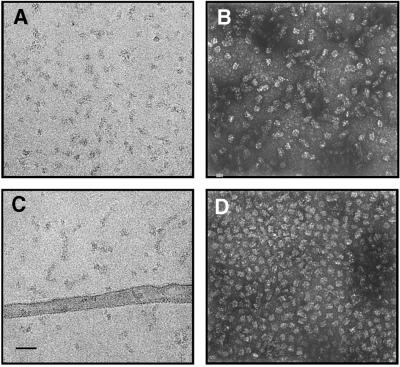

Micrographs of fully active H+-ATPase prepared in 0.5 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.8 show homogeneous particles (Figure 2A and B). When 2 mM ADP was added to this sample in the presence of Mg2+ and incubated on ice for >30 min, the particles maintained a similar overall shape, which can be seen in ice-embedded or negatively stained preparations (Figure 2C and D).

Fig. 2. Electron micrographs of the H+-ATPase from N.crassa in the ligand-free (A and B) and the Mg2+/ADP-bound (C and D) states. The overall appearance of the particles prepared either in ice (A and C) or with negative staining (B and D) is very similar and not distinguishable without image processing. Scale bar = 500 Å. (A) Electron micrograph showing the particles embedded in a thin layer of vitreous ice. The samples are unstained so that protein density appears in black. (B) Negative staining of the H+-ATPase shown in (A). Protein densities that exclude the dense stain are visible in white. (C) Electron micrograph showing the H+-ATPase (in the presence of Mg2+/ADP) embedded in a thin layer of vitreous ice. (D) Negative staining of the H+-ATPase (in the presence of Mg2+/ADP) showing homogeneous particles.

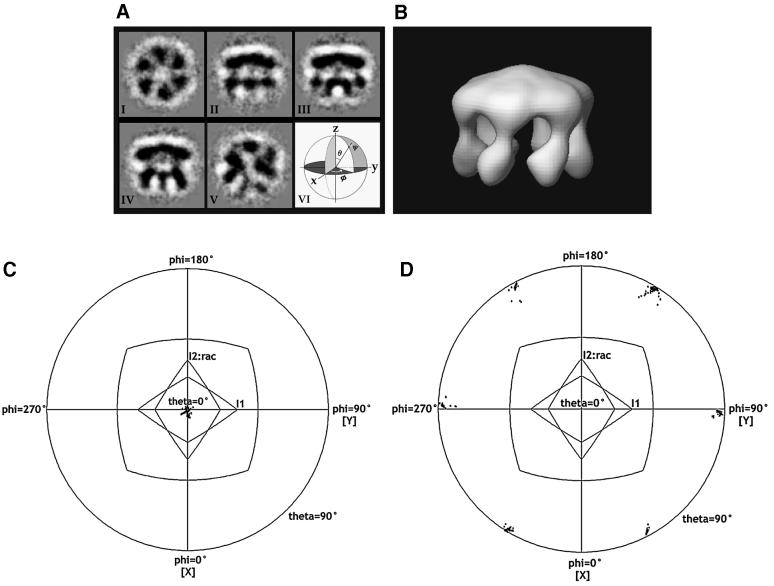

Figure 3A(I–V) presents five typical class-sums of the aligned and classified images out of 50 obtained by multivariate statistical analysis using IMAGIC (van Heel et al., 1996). Multivariate statistical analysis makes no assumptions about symmetry, but simply looks for, and categorizes, images into classes. It is apparent that the view shown in Figure 3A(I) is a projection along a 6-fold rotational axis, in which the Eulerian angle θ [Figure 3A(VI)] of the particle should be zero. The side views (θ = 90°) vary depending on the angle of φ [Figure 3A(VI)], while the width of the particle should match the diameter of the particle that is recognizable in the 6-fold view. Among such possible ‘side’ views, three are represented in Figure 3A(II–IV). These side views have a characteristic oblong shape with height smaller than width and a sharply contrasted line at the upper edge of the particle with a more structured bottom. These observations let us conclude that the symmetry of the particles is consistent with a 6-fold point-group symmetry, as expected from biochemistry (Chadwick et al., 1987) and earlier electron crystallography (Cyrklaff et al., 1995).

Fig. 3. The H+-ATPase in the ligand-free state and its 6-fold internal symmetry. (A) Five characteristic projection views out of 50 class-sum images obtained by multivariate statistical analysis (I–V). Eulerian angles, ψ, θ and φ (VI). In terms of the 3D map which follows, (I) corresponds to the top view, (II–IV) to side views and (V) to an intermediate view. (B) The 3D angular reconstitution map displayed as a shaded surface. Slightly tilted side view with the membrane surface below. The volume of the molecule is 510 000 Å3 at this contour level, which is ∼68% of the full molecular volume, but shows the underlying structure more clearly. (C) The 2D angular plot of the orientation angles, θ and φ, resulting from FREALIGN for the class-sum shown in Figure 3A(I). The orientation was searched and refined by randomization for 20 000 cycles. The radial axis defines θ from 0° (centre) to 90° (outer shell) in projection. The angle, φ, is represented by a counterclockwise rotation from 0° to 360°. The orientations in which the particle gives rise to the phase residuals within 5° of the best value are shown by crosses in the plot (θ = 0°). (D) The 2D angular plot examined for the class-sum shown in Figure 3A(II). The minima for the phase residual were found at θ = 90° and φ = 30°, 90°, 150°, 210°, 270° or 330°.

The orientation parameters that were roughly determined by the angular reconstitution method (Figure 3B) were subsequently examined by using the program FREALIGN (Materials and methods). Two output results showing the angular plots of the orientation parameters for the class-sums shown in Figure 3A(I) and (II) are displayed in Figure 3C and D, respectively. In these plots, each dot represents one orientation angle of θ and φ of the particle, where a local minimum of the phase residual of the particle image was found against the 3D map shown in Figure 3B. By repeating this search many times, the best orientation parameters were selected. Only those minima within 5° of the best value are shown, with the lowest minimum being marked by a cross in the plot. Figure 3C indicates that the class-sum shown in Figure 3A(I) is the view oriented with the angle of θ = 0°. This is the angle that is expected from a top view. Similarly, Figure 3D shows the local minima of the phase residual with the orientation angles of θ = 90° and φ = 30° + 60°·n, where n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The expected 6-fold redundancy in the orientation parameters for a single side view is also clear.

Using the defocus contrast transfer function (CTF) correction and the refinement procedure described in Materials and methods, the 3D maps in two states were each obtained from 2000 particles with the 6-fold symmetry being imposed. The point at which the Fourier shell correlation curve of the final maps falls to 0.5 indicates a resolution of 17 Å (for the ligand-free structure) and 17.5 Å (for the Mg2+/ADP-bound structure) using the Fourier shell correlation coefficient between the two halves of each set of data (Harauz and van Heel, 1986).

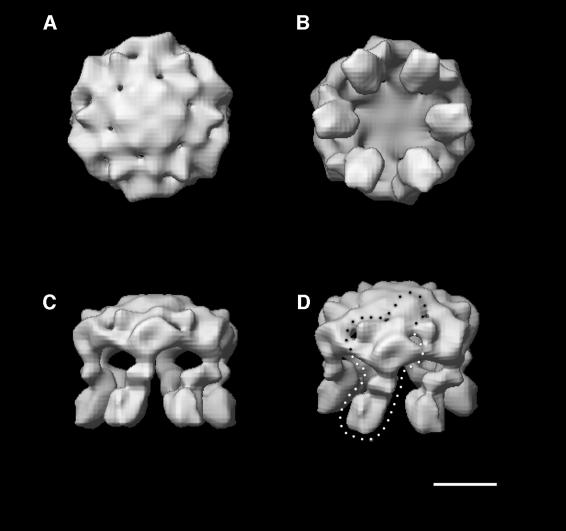

Structure of the H+-ATPase hexamer in the ligand-free state

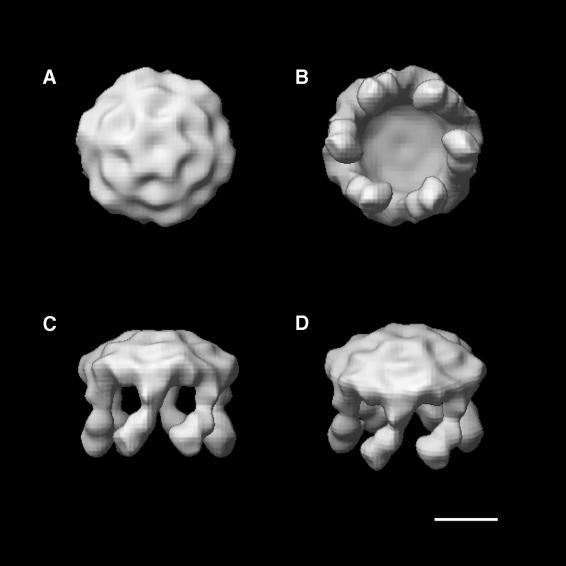

The 3D map of the H+-ATPase in the ligand-free state shows the 6-fold relation between asymmetric monomers with an overall diameter of ∼130 Å (Figure 4). The views parallel to the 6-fold axis from the top and bottom of the model are shown in Figure 4A and B, respectively. The bulky top domain (Figure 4A) shows an undulating hollow dome with six blades radiating from the central 6-fold axis. In contrast, the bottom view (Figure 4B) shows six prominent protrusions, which stand out from the bulky disc-shaped top domain behind. The protrusions have a centre-to-centre distance of 88 Å across the diameter and individual cross-sections of 36–40 Å. The side view (Figure 4C) shows that these protrusions are 70 Å long with distinguishable substructure. The lower regions (feet) have a more uniform cross-section and are ∼40 Å tall. By comparing the structure of the lower domains with the electron crystallographic map published previously (Auer et al., 1998), it is probable that these densities correspond to the transmembrane domain. The upper part (∼30 Å tall) connects the membrane domain to the bulky cytoplasmic head. The cytoplasmic head region has six closely packed density peaks located around the 6-fold axis, as shown in Figure 4A and D. Further from the 6-fold axis, the densities of the hollow dome are loosely packed with gaps or openings in the structure. The dotted line in Figure 4D tries to outline the most connected density, which might represent a monomeric unit.

Fig. 4. The 3D map of the unliganded H+-ATPase hexamers calculated by FREALIGN. Surface-shaded map presentation. Scale bar = 50 Å. (A) A view from the top along the 6-fold symmetry axis. The cytoplasmic domain is nearest to the viewer. (B) The bottom view rotated by 180° from that shown in (A). The protrusions (membrane domain) are arranged around the 6-fold axis with a centre-to-centre distance of ∼88 Å across the diameter. The membrane domains are nearest to the viewer. (C) A side view rotated by 90° from that shown in (B). The cytoplasmic domain is at the top. (D) A view rotated by a further 20° from that shown in (C). The density that belongs to the tentative monomer is indicated by a dotted line.

Structure of the H+-ATPase hexamer in the substrate-bound state

The 3D map of the H+-ATPase in the Mg2+/ADP-bound state (Figure 5A and B) has a similar overall character to that of the unliganded state. The complex still shows six protrusions that end with membrane domains (feet) to which the cytoplasmic head is linked (Figure 5C). It is thus likely that the basic architecture of the hexameric organization is largely unaffected by substrate binding. The structural resemblance of the uppermost part of the head in the two maps, where six large density peaks are closely packed around the 6-fold axis, supports this notion (Figures 4D and 5D).

Fig. 5. The 3D map of the H+-ATPase in the Mg2+/ADP-bound state determined by FREALIGN. Shaded-surface presentation. Scale bar = 50 Å. (A) A view from the top along the 6-fold axis. The cytoplasmic domain is nearest to the viewer. (B) The bottom view rotated by 180° from that shown in (A). The membrane domains are nearest to the viewer. The centre-to-centre distance between membrane domains is ∼96 Å across the diameter. (C) A side view rotated by 90° from that shown in (B). The cytoplasmic domain is at the top. (D) A view rotated by a further 20° from that shown in (C).

However, in contrast to the structure of the unliganded state, the structure of the Mg2+/ADP-bound state (Figure 5) has a smoother surface texture, without the bulges or holes seen in the unliganded structure (Figure 4). For the comparison, both maps are contoured to represent the same overall molecular volume. It is thus reasonable to conclude that the cytoplasmic domain becomes more closely packed on substrate binding. Accordingly, the total surface area of the enzyme in this intermediate state may be expected to be reduced compared with the unliganded H+-ATPase.

Previous studies have shown that the Neurospora plasma membrane H+-ATPase has a characteristic pattern of protease sensitivity during the reaction cycle (Addison and Scarborough, 1982; Brooker and Slayman, 1983). In the absence of substrate, the H+-ATPase is rapidly degraded by trypsin into small pieces, whereas in the presence of Mg2+/ADP, after removal of a small region at the N-terminus, the rest of the enzyme is resistant to further digestion. Our present 3D models provide a structural rationalization for this observation. It is likely that in the more disordered, open-enzyme conformation, the trypsin cleavage sites are readily accessible to the protease, while in the more ordered, closely packed conformation after substrate binding, the H+-ATPase becomes insensitive to trypsin degradation. The decreased H+/D+ exchange after substrate binding is also consistent with the nature of the observed structural changes (Goormaghtigh et al., 1994).

Domain movement induced by Mg2+/ADP binding during the catalytic cycle of ATP-dependent proton transport

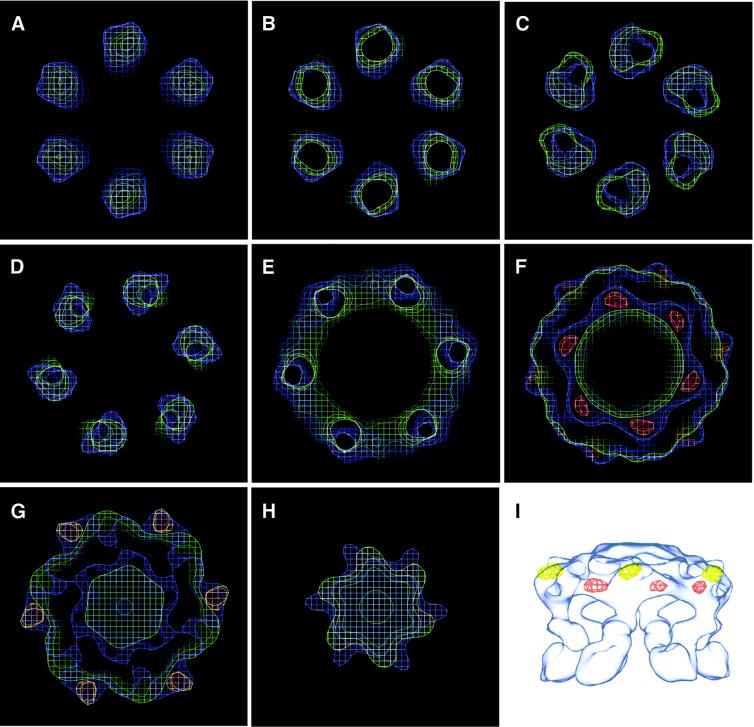

To examine in more detail the conformational change of the H+-ATPase induced by ADP in the presence of Mg2+, the map of the unliganded form was subtracted from the map of the substrate-bound form. The resulting difference map thus comprises positive and negative densities, of which the positive density corresponds to the mass that has newly emerged in the Mg2+/ADP form, and the negative density represents the mass that has moved from the unliganded form. These positive and negative density peaks are illustrated in Figure 6 by superimposing the 3D structures in two states. The positive density peaks (red contours) are found inside the hexamer in the cytoplasmic domain, ∼42 Å from the 6-fold axis (Figure 6F). Six negative peaks (yellow contours) are located in the outermost part belonging to the cytoplasmic head of the unliganded H+-ATPase (blue contours). These peaks are 62 Å from the symmetry axis and 15 Å above the centre of the positive peaks parallel to the 6-fold axis (Figure 6F). The location of the peaks is also shown in Figure 6(I). The surface contour moves towards the 6-fold axis by a distance of ∼15 Å. There is, therefore, a net transfer of mass to make the H+-ATPase head region more closely packed on ligand binding.

Fig. 6. The difference map obtained by subtracting the structure of the H+-ATPase in the unliganded state from that of the Mg2+/ADP-bound state, showing the positive (red) and the negative (yellow) density peaks. The structures in both ligand-free (blue) and the Mg2+/ADP-bound (green) states are superimposed on the difference map. The sections are ordered (A–H) from the membrane domain to the cytoplasmic head, with each slice being ∼15 Å thick. (I) Superposition of the highest difference peaks on a surface-rendered map.

The cytoplasmic head region of the unliganded hexamer (blue contours) appears as six nearly separated monomers in Figure 6F and G. The sections of the map of the substrate-bound form (green contours) show a more continuous ring-like structure. Such continuous density shows that the interactions between the surfaces of the neighboring monomers in the substrate-bound state are more complementary than that in the ligand-free state.

A close inspection of the two structures shows that a conformational change also occurs in the membrane domain. In Figure 6C, the movement of the membrane domain is recognizable by a lateral shift of the centre of mass between the two structures. The centre-to-centre distance across the diameter differs from one conformation to the other by ∼8 Å. The more distant association is found in the substrate-bound state. The shift is accompanied by a small clockwise rotation of ∼2° around the 6-fold axis. Above the centre of the structure, a modest inward movement of mass towards the 6-fold axis is observed (Figure 6E), suggesting that the six protrusions tilt outwards, pivoting about a point near the centre of the structure. Taken together, our structural data provide evidence that the substrate-induced structural change in the cytoplasmic domain modulates the structure of the membrane domain. Since the hexameric detergent-solubilized enzyme is fully functional (Hennessey and Scarborough, 1988), it is likely that the structure and structural changes we have observed in detergent solution are the same as those that occur in vivo. The resolution of the current work is insufficient to say whether or not there are helix rearrangements within the membrane domain associated with the substrate-induced conformational change, although the change in shape in the membrane region would tend to suggest that this is the case. If so, it would mean that there are transmembrane helix movements in the catalytic cycle before phosphorylation and the subsequent conformational change that is thought to lead to the decrease in affinity of the ion-binding site.

Conclusion

In earlier work on the structure and structural changes in the Ca2+-ATPase, large domain structural changes have been observed either directly or by deduction or comparison of the results using different techniques. For example, in the X-ray crystal structure of the Ca2+-ATPase in the presence of a high (10 mM) Ca2+ concentration by Toyoshima et al. (2000), the phosphorylation and nucleotide domains were 25 Å apart, and at some point in the enzymatic cycle the two sites must be closely juxtaposed. A comparison of this high Ca2+ structure with the structure of Ca2+-ATPase in tubular crystals, in the absence of calcium and presence of decavanadate (Xu et al., 2002), also showed large changes in the relative domain arrangement. By comparison, the biggest structural changes found in this work, while clear and observable, are smaller (<15 Å). Since the H+-ATPase is still fully functional in its hexameric state (Hennessey and Scarborough, 1988), and the tertiary structural change we have observed may be the largest throughout the full reaction cycle (Goormaghtigh et al., 1994), we conclude that large changes in structure are not essential for the ion-pumping function. Instead, significant (15 Å) structural changes in the nucleotide, phosphorylation and/or actuator domains in the head may cause more modest structural changes in the membrane domains. We hope to carry this single-particle analysis to higher resolution to be able to examine in more detail the nature of the conformational changes in the cytoplasmic domain and those in the membrane domain, which must be closely linked to the ion-pumping process.

Materials and methods

Protein preparation and electron microscopy

The N.crassa plasma membrane H+-ATPase (9.5 mg/ml) in the presence of the dodecylmaltoside (3.7 mg/ml) was purified as described previously (Cyrklaff et al., 1995) and stored at –20°C. Samples (50 µl) at 0°C (on ice) were mixed with 1 µl of 5 mg/ml lyso-phosphatidyl-glycerol (LPG), followed by incubation for 10 min. The samples were then dialysed to remove glycerol against 0.5 mM Tris–phosphate buffer pH 6.8 containing 50 µg/ml LPG for 5–8 h at 4°C. The protein concentration of the preparation that was applied to the electron microscope grids was ∼5.3 mg/ml. To convert the H+-ATPase to the Mg2+/ADP-bound state, an equimolar solution (200 mM) of MgSO4 and the sodium salt of ADP (from Sigma), adjusted to pH 6.8, was added to the protein preparation to a final concentration of 2 mM. This mixture was incubated at 0°C for at least 30 min. Since the Ki for Mg2+/ADP is 0.2 mM, this means that >90% of hexamers have either six or five of their binding sites occupied.

For electron cryo-microscopy, 3 µl samples were applied to copper/rhodium grids (Bradley, 1965) coated with holey carbon films and mounted on a plunger at 4°C in a rapid freezing apparatus (Bellare et al., 1988). Specimens were then blotted with a single layer of filter paper (Whatman No. 1) for 7 s, followed by rapid plunging into liquid ethane. Since the ATPase molecules are suspended in thin films, which are in contact with the carbon support only at the perimeter of each hole, the pH should not be perturbed from that of the buffer pH 6.8. The frozen specimens were stored in liquid nitrogen until transfer to a Gatan cold stage. Micrographs were taken under low-dose conditions using a Philips F30 FEG microscope operated with an acceleration voltage of 300 kV at a specimen temperature of –182°C. Images were recorded on Kodak SO 163 film with 1 s exposure time (7–10 e– per Å2) at a magnification of 39 000× with a defocus range of 4.1–6.1 µm. Films were developed for 12 min in full-strength Kodak D-19 developer.

For electron microscopy with negative stain, similar samples were applied to grids coated with continuous carbon films, blotted without drying and treated twice with a small drop of 1% uranyl acetate followed by brief blotting and then air dried.

Image processing, structure determination and refinement

The micrographs were digitized as optical densities with a Zeiss SCAI scanner at a step size of 7 µm per pixel, then 2 × 2 adjacent pixels were averaged to produce 14 µm pixels, corresponding to 3.59 Å per pixel on the specimen. A total of 2000 particles from the ligand-free state and 2000 particles from the Mg2+/ADP-bound state were selected from the micrographs, and boxes of 64 × 64 pixels extracted to form a stack of particle images using the program Ximdisp (Crowther et al., 1996). The two sets of particle images were floated and normalized in their grey scale, so that each data set has a unit variance and zero mean. The first 3D map was produced using the angular reconstitution method within IMAGIC (van Heel et al., 1996). Briefly, the particle images were aligned with their centres of mass in the middle of each box and then classified into 50 characteristic views by multivariate statistical analysis. After several cycles of the iterative classification and alignment of all particles against all the characteristic views, 12 class-sums were selected for the reconstruction of the initial 3D map. This map was then projected into 33 equally spaced oriented views (the anchor set) to which the original images were realigned. The classification and angular reconstitution procedure was further repeated until the 3D map that is referred to as the reference 3D map, as shown in Figure 3B, was obtained from 29 characteristic views.

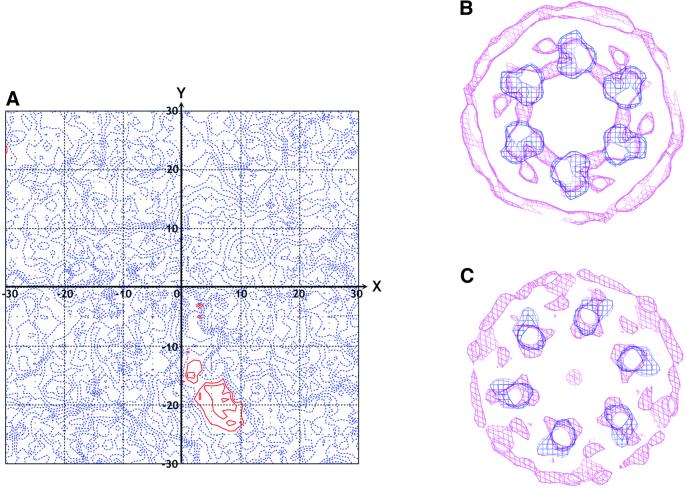

The defocus CTF of each image was then corrected using the program FREALIGN (Grigorieff, 1998). First, the defocus and astigmatism of each micrograph, determined roughly by optical diffractometer, were refined using the program CTFFIND2 applied to the whole micrograph in the resolution range of 140–14 Å (for the unliganded state) or 160–14 Å (for the Mg2+/ADP state). These values were then used as input to FREALIGN to redetermine the orientation and positional parameters of each particle by comparison to the initial reference 3D map from IMAGIC. The resolution range of 80–35 Å was chosen to keep the analysis within the first zero of the CTF. The global parameters used for the systematic randomized search and refinement of particle orientation parameters (IFLAG = –4) are as follows: radius of object (RI) = 103 Å; proportion of amplitude contrast (WGH) = 0.07; fraction set aside for calculation free phase residual in percent (PFRAC) = 0.02; number of standard deviations above mean (XSTD) = –0.25; phase residual/pseudo-B-factor conversion constant (PBC) = 100; average phase residual (BOFF) = 45; angular step size for the angular search (DANG) = 200; and number of cycles (ITMAX) = 200. The resolution of successive reconstructions followed by redetermination of position and orientation parameters was then extended out to 15 Å with symmetry C6 applied throughout. The magnification refinement was carried out for each micrograph in a mode of IFLAG = 1 with the previously CTF-corrected parameter file, in which the high-resolution cut-off (RMAX2) was set to 18 Å. The refinement for both defocus and astigmatism was then carried on with the new reference 3D map and the input parameter file resulting from the magnification refinement. By iteration of these refinement steps 4–5 times, 17–17.5 Å resolution maps were obtained by averaging each of 2000 particles in both states, as judged by the Fourier shell correlation curve with 0.5 cut-off. Using a pair of low-dose images of the same area of the specimen with tilt angle differing by 20°, the absolute hand of the 3D reconstruction was determined (Figure 7A) as described (P.B.Rosenthal and R.Henderson, in preparation). The resulting structure is shown in Figure 4. The handedness was further confirmed by comparing the transmembrane region of the single-particle structure with that determined by electron crystallography of 2D crystals (Auer et al., 1998) (Figure 7B and C).

Fig. 7. Determination of absolute hand of the H+-ATPase hexamer deduced by single-particle analysis (A), and by comparison to the electron crystallographic map (B and C). (A) Phase residuals plotted out as a function of the relative tilt around the X- and Y-axis between particles from a pair of micrographs are contoured in red for lower phase residuals and in blue for higher phase residuals. A clear minimum was found in the phase residual at (7, –19) degrees, which agrees with the 20° tilt angle and the direction of the tilt axis between the pair of micrographs, as recorded on the microscope goniometer. Thus, the absolute hand of the structure reconstructed by single-particle analysis was correctly determined as shown in Figure 4. (B and C) The blue contours represent the same sections of the transmembrane domain as shown in Figure 6C and D. These structures, viewed with the cytoplasmic side behind, were superimposed on the corresponding regions of the 3D map (Auer et al., 1998) of the 2D crystals (magenta) truncated to a resolution of 14 Å. In (B), six arrowhead-shaped features within the membrane domains of both maps point clockwise tangentially, indicating that both structures have the same hand.

Structure comparison and visualization of 3D maps

The difference map was calculated by subtracting the 3D map of the unliganded H+-ATPase from that of the Mg2+/ADP form of the H+-ATPase using the program TWOFILE. The 3D maps in Figures 4 and 5 are visualized by shaded-surface view using the programs SURF and LIGHT (Vigers, 1986) at the threshold level corresponding to the volume of ∼385 000 Å3 in both states. This is only about half the volume that would be expected for the van der Waals surface of the molecule, which would give an expected volume of 750 000 Å3. However, this lower contour level allows the features and shape of the structures to be seen more clearly. The electron density maps in Figures 6 and 7 are displayed by the program O (Jones et al., 1991) at the same threshold level shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

K.-H.R. was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization long-term fellowship.

References

- Addison R. (1986) Primary structure of the Neurospora plasma membrane H+-ATPase deduced from the gene sequence. Homology to Na+/K+-, Ca2+- and K+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem., 261, 14896–14901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addison R. and Scarborough,G.A. (1982) Conformational changes of the Neurospora plasma membrane H+-ATPase during its catalytic cycle. J. Biol. Chem., 257, 10421–10426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer M., Scarborough,G.A. and Kuhlbrandt,W. (1998) Three-dimensional map of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in the open conformation. Nature, 392, 840–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastide F., Meissner,G., Fleischer,S. and Post,R.L. (1973) Similarity of the active site of phosphorylation of the adenosine triphosphatase from transport of sodium and potassium ions in kidney to that for transport of calcium ions in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of muscle. J. Biol. Chem., 248, 8385–8391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellare J.R., Davis,H.T., Scriven,L.E. and Talmon,Y. (1988) Controlled environment vitrification system: an improved sample preparation technique. J. Electron Microsc. Tech., 10, 87–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D.H. (1965) The preparation of specimen support films. In Kay,D.H. (ed.), Techniques of Electron Microscopy. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford, UK, pp. 58–74.

- Brooker R.J. and Slayman,C.W. (1983) Effects of Mg2+ ions on the plasma membrane [H+]-ATPase of Neurospora crassa. I. Inhibition by N-ethylmaleimide and trypsin. J. Biol. Chem., 258, 8827–8832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick C.C., Goormaghtigh,E. and Scarborough,G.A. (1987) A hexameric form of the Neurospora crassa plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 252, 348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther R.A., Henderson,R. and Smith,J.M. (1996) MRC image processing programs. J. Struct. Biol., 116, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyrklaff M., Auer,M., Kuhlbrandt,W. and Scarborough,G.A. (1995) 2D structure of the Neurospora crassa plasma membrane ATPase as determined by electron cryomicroscopy. EMBO J., 14, 1854–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dame J.B. and Scarborough,G.A. (1980) Identification of the hydrolytic moiety of the Neurospora plasma membrane H+-ATPase and demonstration of a phosphoryl-enzyme intermediate in its catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry, 19, 2931–2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormaghtigh E., Chadwick,C. and Scarborough,G.A. (1986) Mono mers of the Neurospora plasma membrane H+-ATPase catalyze efficient proton translocation. J. Biol. Chem., 261, 7466–7471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormaghtigh E., Vigneron,L., Scarborough,G.A. and Ruysschaert,J.M. (1994) Tertiary conformational changes of the Neurospora crassa plasma membrane H+-ATPase monitored by hydrogen/deuterium exchange kinetics. A Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy approach. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 27409–27413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorieff N. (1998) Three-dimensional structure of bovine NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) at 22 Å in ice. J. Mol. Biol., 277, 1033–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harauz G. and van Heel,M. (1986) Exact filters for general geometry three dimensional reconstruction. Optik, 73, 146–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessey J.P. Jr, and Scarborough,G.A. (1988) Secondary structure of the Neurospora crassa plasma membrane H+-ATPase as estimated by circular dichroism. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 3123–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardetzky O. (1966) Simple allosteric model for membrane pumps. Nature, 211, 969–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou,J.Y., Cowan,S.W. and Kjeldgaard,M. (1991) Improved methods for binding protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A, 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan D.H., Brandl,C.J., Korczak,B. and Green,N.M. (1985) Amino-acid sequence of a Ca2+ + Mg2+-dependent ATPase from rabbit muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum, deduced from its complementary DNA sequence. Nature, 316, 696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull G.E., Schwartz,A. and Lingrel,J.B. (1985) Amino-acid sequence of the catalytic subunit of the (Na+ + K+)ATPase deduced from a complementary DNA. Nature, 316, 691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima C., Nakasako,M., Nomura,H. and Ogawa,H. (2000) Crystal structure of the calcium pump of sarcoplasmic reticulum at 2.6 Å resolution. Nature, 405, 647–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heel M., Harauz,G. and Orlova,E.V. (1996) A new generation of the IMAGIC image processing system. J. Struct. Biol., 116, 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigers G.P.A. Ph.D. thesis (1986) Clathrin Assemblies in Vitreous Ice. Cambridge University, UK.

- Xu C., Rice,W.J., He,W. and Stokes,D.L. (2002) A structural model for the catalytic cycle of Ca2+-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol., 316, 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]