Abstract

In Xenopus oocytes, the c-mos proto-oncogene product has been proposed to act downstream of progesterone to control the entry into meiosis I, the transition from meiosis I to meiosis II, which is characterized by the absence of S phase, and the metaphase II arrest seen prior to fertilization. Here, we report that inhibition of Mos synthesis by morpholino antisense oligonucleotides does not prevent the progesterone-induced initiation of Xenopus oocyte meiotic maturation, as previously thought. Mos-depleted oocytes complete meiosis I but fail to arrest at metaphase II, entering a series of embryonic-like cell cycles accompanied by oscillations of Cdc2 activity and DNA replication. We propose that the unique and conserved role of Mos is to prevent mitotic cell cycles of the female gamete until the fertilization in Xenopus, starfish and mouse oocytes.

Keywords: cdc2/mos/oocyte/proto-oncogene/Xenopus

Introduction

In the ovaries of most animals, oocytes are arrested in prophase of the first meiotic division (prophase I) until a hormonal signal induces the transition from prophase I to an arrest point during the second meiotic division. This arrest is at metaphase II in Xenopus, mouse and most other vertebrates or at the pronucleus stage in starfish. The process that is initiated by hormonal stimulation, called meiotic maturation, is under the control of M-phase promoting factor (MPF), a ubiquitous complex between the Cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc2 and Cyclin B. In Xenopus prophase I arrested-oocytes, MPF is maintained in an inactive form by the phosphorylation of Cdc2 on Thr14 and Tyr15. In response to progesterone, Cdc2 is activated in a protein synthesis-dependent manner by the Cdc25 phosphatase, which removes the inhibitory phosphates of Cdc2. Active MPF induces germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), chromosome condensation and metaphase I spindle formation in oocytes. MPF activity falls after metaphase I, then rises again and remains high during metaphase II arrest until fertilization (Nebreda and Ferby, 2000). The second meiotic arrest is due to a cytostatic factor (CSF), which appears shortly after meiosis I and disappears after fertilization (Masui and Markert, 1971). Although a number of proteins have been implicated as components of CSF activity, its biochemical composition is still unknown.

The c-mos gene was one of the first proto-oncogenes to be cloned (Oskarsson et al., 1980). The synthesis of its product, the serine/threonine kinase Mos, is highly regulated and restricted in time and cell type. Mos is almost undetectable in somatic cells and is specifically expressed in germ cells, where it functions only during the short period of meiotic maturation before being proteolysed at fertilization. When ectopically expressed in somatic cells, Mos can induce either cell death or oncogenic transformation (Yew et al., 1993). Mos is absent from prophase oocytes and is synthesized from maternal mRNA in vertebrates and starfish oocytes during meiotic maturation (Oskarsson et al., 1980; Sagata et al., 1988; Tachibana et al., 2000). It activates a MAPK kinase (MEK), which in turn activates MAPK (Nebreda et al., 1993; Posada et al., 1993; Shibuya and Ruderman, 1993). Ribosomal S6 kinase, Rsk, is then activated by MAPK (Palmer et al., 1998). Xenopus Mos, as well as its downstream targets, are able to induce meiotic maturation in the absence of progesterone when microinjected into prophase oocytes (Yew et al., 1992; Haccard et al., 1995; Huang et al., 1995; Gross et al., 2001). Therefore, it has been proposed that Mos controls the entry into meiosis I. However, in mouse, starfish and goldfish, neither Mos synthesis nor MAPK activity are required for Cdc2 activation and progression through meiosis I (Colledge et al., 1994; Hashimoto et al., 1994; Verlhac et al., 1996; Sadler and Ruderman, 1998; Kajiura-Kobayashi et al., 2000; Tachibana et al., 2000). In contrast, in Xenopus oocytes, the destruction of Mos mRNA by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides was shown to prevent progesterone-induced GVBD (Sagata et al., 1988). In addition, Mos is able to induce meiotic maturation when microinjected into Xenopus prophase oocytes, although it is not yet clear whether protein synthesis is needed for this to occur (Sagata et al., 1989a; Yew et al., 1992). Together, these results have led to the conclusion that Mos synthesis is both sufficient and required to initiate meiotic maturation. Consistent with this conclusion are observations that recombinant Mos was not able to activate Cdc2 in the presence of the MEK inhibitor, U0126, arguing that MAPK is the direct link between Mos and Cdc2 activation in Xenopus oocytes (Fisher et al., 1999; Gross et al., 2000). On the other hand, the prevention of MAPK activation by this inhibitor was recently shown to delay, but not to prevent, the Cdc2 activation induced by progesterone without affecting the synthesis of Mos. Therefore, progesterone appears to be able to activate Cdc2 by a mechanism that is independent of MAPK, a conclusion that is difficult to reconcile with a requirement for Mos downstream of progesterone in Xenopus oocyte. Two hypotheses could explain why Cdc2 activation is suppressed when Mos synthesis is prevented by antisense oligonucleotides while it is not when MAPK activation is prevented by U0126 treatment. First, Mos could activate a MAPK-independent pathway. It has been recently proposed that Mos would downregulate Myt1, the inhibitory kinase of Cdc2, independently of MAPK (Peter et al., 2002). However, this cannot explain why Mos is unable to induce Cdc2 activation in the absence of MAPK (Gross et al., 2000). Secondly, the antisense oligonucleotides (Sagata et al., 1988) could have effects other than just preventing Mos synthesis.

Besides the initial activation of Cdc2 prior to GVBD, Mos has been shown to be required during the metaphase I to metaphase II transition for the suppression of S phase. In Xenopus oocytes, when the synthesis or the activity of Mos is specifically inhibited at the time of GVBD, or when MAPK activation is prevented by U0126, the activity of Cdc2 remains low after completion of meiosis I, and oocytes fail to enter meiosis II (Daar et al., 1991; Furuno et al., 1994; Gross et al., 2000). In these oocytes, Cyclin B does not re-accumulate, and both nuclear envelope reformation and DNA replication occur. However, in mouse oocytes, conflicting results have been obtained. Although the entry into meiosis II is not affected in oocytes from Mos–/– mice (Colledge et al., 1994; Hashimoto et al., 1994; Verlhac et al., 1996), the injection of antisense oligonucleotides either arrests oocytes before the emission of the first polar body (Paules et al., 1989) or induces nuclear reformation after meiosis I (O’Keefe et al., 1989). Cyclin B does not re-accumulate and the activity of Cdc2 does not re-increase after GVBD (O’Keefe et al., 1991), the same result seen following antisense oligonucleotide injections into Xenopus oocytes (Furuno et al., 1994). Therefore, Mos ablation has different effects on meiotic maturation, depending on the experimental strategy. The most specific deletion method, gene knock-out, has been performed in mice and suggests that the essential role of Mos is to prevent parthenogenesis, a function that was not revealed by the antisense experiments performed in Xenopus and mouse oocytes.

At the end of meiotic maturation, Mos is thought to participate in the control of the second meiotic arrest of unfertilized eggs. Mos, as well as its downstream targets, exhibit CSF activity (Sagata et al., 1989b; Haccard et al., 1993; Huang et al., 1995; Bhatt and Ferrell, 1999; Gross et al., 1999), as defined by the original assay, which involves the microinjection into one blastomere of a two-cell embryo. When CSF is present, the injected blastomere arrests in metaphase, whereas the uninjected blastomere continues cell division (Masui and Markert, 1971). Nevertheless, the in ovo consequences of the ablation of Mos in unfertilized eggs has only been analyzed in mouse oocytes (Colledge et al., 1994; Hashimoto et al., 1994).

In this study, we took advantage of a new experimental approach based on morpholino antisense oligonucleotides to gain new insights into the precise roles of Mos during Xenopus oocyte meiotic maturation. We were able to block Mos synthesis without inhibiting the entry into meiosis I and therefore were able to investigate the requirements for Mos during three key periods of meiotic maturation: the activation of Cdc2 before GVBD, the metaphase I to metaphase II transition characterized by the absence of DNA replication, and the metaphase II arrest. Here, we demonstrate that Mos synthesis is only required after meiosis I, where it functions to prevent DNA synthesis and the spontaneous initiation of mitotic cell cycles, and to arrest oocyte meiosis in metaphase II, until fertilization.

Results

Mos ablation does not prevent GVBD and Cdc2 activation induced by progesterone

To investigate the function of Mos synthesis in Xenopus oocytes, we have used a new approach based on morpholino antisense oligonucleotides. Morpholinos are oligonucleotides with a morpholine backbone. They have been shown to be very efficient gene-specific translational inhibitors in Xenopus, when designed as antisense oligonucleotides complementary to the sequence around the translation initiation codon (Heasman et al., 2000). They prevent translation through steric blockade, rather than by targeting RNA for degradation, as DNA antisense oligonucleotides do (Summerton and Weller, 1997).

We compared the effects of conventional antisense DNA oligonucleotides (A–) with morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (M) on GVBD induced by progesterone. For both types of oligos, we had exactly the same sequence as the 25mer A– oligonucleotide spanning the Mos mRNA start codon published in the pioneering paper by Sagata et al. (1988). For controls, we introduced six mispairs in the A– sequence of the DNA and morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (Ac and Mc respectively), while preserving the same overall base composition.

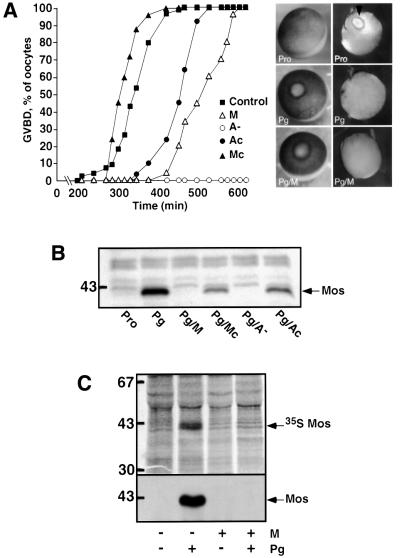

As reported previously (Sagata et al., 1988), the injection of antisense oligonucleotides completely inhibited progesterone-induced GVBD (Figure 1A). Surpris ingly, the injection of morpholino antisense did not prevent GVBD in response to progesterone, although it was delayed by 2 h compared with control progesterone-treated oocytes. The morphology of the white spot at the animal pole of the cell was characteristic of oocytes that have undergone GVBD, and was identical in all maturing oocytes regardless of whether or not they had been injected with morpholino antisense (Figure 1A and see Figure 6). We directly ascertained that GVBD had really occurred in morpholino antisense-injected oocytes by oocyte dissection (Figure 1A). Control morpholinos or traditional oligos did not block maturation, although GVBD was delayed with control DNA oligonucleotides, suggesting that they have a non-specific effect. The amount of A– oligonucleotide microinjected (130 ng) was chosen according to Sagata et al. (1988); a lower amount did not block GVBD in all oocytes, and higher amounts were known to be toxic. For morpholinos, we started from 130 ng per oocyte, and decreased the amount injected until we determined the lowest amount (84 ng per oocyte) that was able to completely block Mos accumulation in all experiments performed, using oocytes from 10 different frogs. The injections of morpholinos at amounts greater than 130 ng per oocyte were not toxic and did not inhibit GVBD in response to progesterone. The levels of Mos in injected oocytes were examined by western blotting, which confirmed that the protein was undetectable after injection with each type of antisense oligonucleotide (Figure 1B). The levels of Mos protein in both controls were always lower than in the uninjected progesterone-treated oocytes, perhaps indicating that mismatched pairs in a 25mer oligonucleotide might not be sufficient to completely abolish all of the antisense activity. The inhibition of Mos synthesis caused by morpholino antisense was further demonstrated by immunoprecipitation following [35S]methionine labeling (Figure 1C). Taken together, our results demonstrate that GVBD is still induced by progesterone, despite the inhibition of Mos translation by morpholino antisense.

Fig. 1. Morpholino antisense inhibits Mos synthesis but does not prevent GVBD. (A) Prophase oocytes were injected or not (solid squares) with either 130 ng of antisense oligonucleotides A– (open circles), 130 ng of control oligonucleotides Ac (solid circles), 84 ng of morpholino antisense M (open triangles) or 84 ng of control morpholino Mc (solid triangles). One hour after injection, oocytes were induced to mature by progesterone (Pg) and the percentage of GVBD was determined as a function of time by following the appearance of the typical white spot at the animal pole of the oocyte (left panel). Right panel: first row illustrates the external morphology of oocytes and second row illustrates sections of fixed oocytes (Pro, prophase oocyte; Pg, progesterone-matured oocyte at GVBD; Pg/M, morpholino antisense-injected oocyte treated by progesterone and fixed at GVBD). Arrowhead indicates the GV. (B) Western blots using Xenopus Mos antibody. One oocyte from the previous experiment was homogenized at GVBD and loaded in each lane. One prophase oocyte (Pro) was loaded on the first lane. The position of one molecular weight marker is indicated on the left. (C) Groups of 50 prophase oocytes were microinjected or not with morpholino antisense (M) and were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine at 200 µCi/ml. One hour later, progesterone (Pg) was added or not. Progesterone-treated oocytes were selected 4 h after GVBD. Mos immunoprecipitates were electrophoresed, transferred to nitrocellulose and first exposed to autoradiography (upper panel) and then probed with anti-Mos antibody (lower panel). The positions of molecular weight markers are indicated on the left.

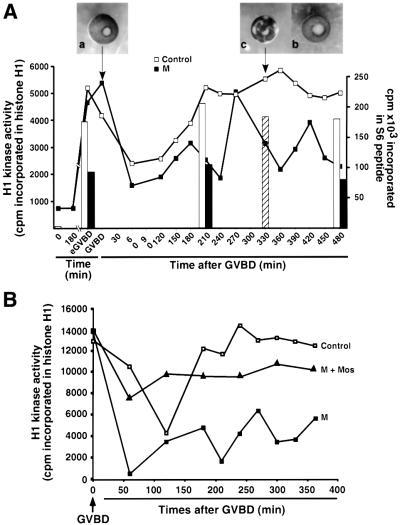

Fig. 6. Mos is required to stabilize Cdc2 activity after GVBD. (A) Oocytes were injected (solid squares, solid bars) or not (open squares, open bars) with morpholino antisense (M). One hour later (time 0), progesterone was added. GVBD started 4 h after progesterone addition in control oocytes, and with a 4 h delay in morpholino antisense-injected oocytes. At GVBD, some morpholino antisense-injected oocytes were injected with 50 ng of recombinant MBP–Mos protein (hatched bar). At indicated times, oocytes were homogenized and kinase activities of Cdc2 (H1 phosphorylation: lines) and Rsk (S6 peptide phosphorylation: bars) were assayed. Each point of Cdc2 and Rsk activities corresponds to four oocytes. The external morphology of injected oocytes is illustrated at the time of GVBD (a) and 5.5 h after GVBD with (b) or without (c) MBP–Mos injection at GVBD. (B) Oocytes were injected (solid squares) or not (open squares) with morpholino antisense (M). One hour later (time 0), progesterone was added. GVBD started 4 h after progesterone addition in control oocytes, and with 3 h delay in morpholino antisense-injected oocytes. At GVBD, some Mos-ablated oocytes were injected with 50 ng of recombinant MBP–Mos protein (triangles). At indicated times, oocytes were homogenized and Cdc2 kinase activity was assayed (three oocytes per point).

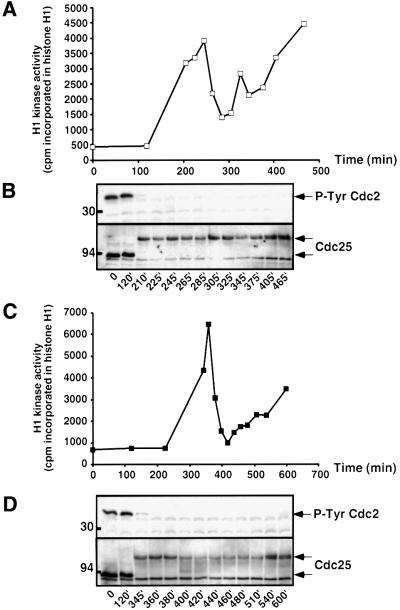

We next ascertained whether Cdc2 was normally activated by progesterone in the presence of morpholino antisense. The H1 kinase activity of Cdc2 in progesterone-treated oocytes peaked at the time of GVBD, regardless of whether or not oocytes had been injected with morpholinos (Figure 2A and C). In the absence of Mos, progesterone was therefore able to induce both Cdc2 activation and GVBD, although both events were delayed in comparison to control oocytes. Interestingly, this delay was never observed when maturation was induced by mRNA encoding the mouse Mos protein (data not shown). This suggests that although Mos is not required for maturation, it certainly contributes to the kinetics of GVBD and the rate of Cdc2 activation. As expected, the protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (CHX), was still able to prevent progesterone-induced maturation after morpholino injection (data not shown), indicating that the synthesis of proteins other than Mos is required to activate Cdc2. Since the initial activation of Cdc2 prior to GVBD depends on dephosphorylation of Cdc2 by the Cdc25 phosphatase, we monitored the phosphorylation state of both proteins by western blotting (Figure 2B and D). In control and morpholino-injected oocytes, Cdc2 was fully dephosphorylated on Tyr15 in the absence of Mos, and Cdc25 was normally activated as shown by its electrophoretic shift at the time of GVBD (Figure 2B and D).

Fig. 2. Progesterone-induced Cdc2 activation in Mos-ablated oocytes. Oocytes were injected (C and D) or not (A and B) with morpholino antisense. One hour later (time 0), progesterone was added and oocytes were collected and homogenized at indicated times. eGVBD, first pigment rearrangement detected at the animal pole (15 min before GVBD); GVBD, well-defined white spot observed at 225 min in control oocytes and at 360 min in morpholino antisense-injected oocytes. The equivalent of three oocytes was assayed for H1 kinase activity (A and C). At indicated times, one oocyte was immunoblotted with antibodies against Tyr15-phosphorylated Cdc2 or against Cdc25 phosphatase (B and D). The positions of the molecular weight markers are indicated on the left.

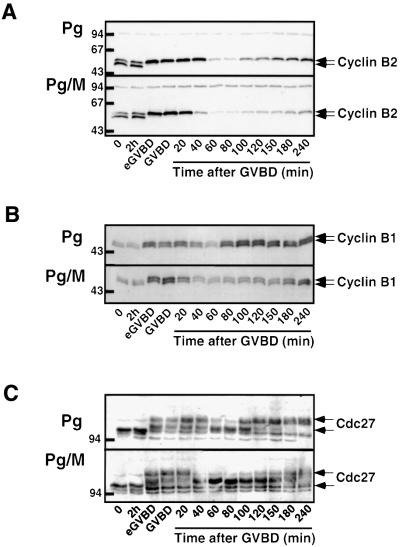

It has been reported previously that the absence of either Mos or MAPK activity prevents Cdc2 reactivation after metaphase I. In these conditions, Cyclins B1 and B2 fail to re-accumulate and the hyperphosphorylation of Cdc27, a component of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) necessary for Cyclin B degradation, does not occur (Furuno et al., 1994; Gross et al., 2000). These results suggest that Mos and MAPK activity are required after GVBD for the accumulation of Cyclin B, perhaps through the regulation of the APC. H1 kinase activity was followed for 4 h after GVBD (Figure 2A), when normally maturing oocytes would progress through the meiosis I to meiosis II transition and arrest in metaphase II. Upon the exit from meiosis I, Cdc2 activity fell to a low level, due to Cyclin B degradation, and was then gradually reactivated during the 4 h period following GVBD in both the presence and absence of morpholino antisense (Figure 2A and C). Cdc25 underwent a partial and transient dephosphorylation in morpholino-injected oocytes, at the time of Cdc2 inactivation (Figure 2D). This observation suggests that, in the absence of Mos, a discrete Tyr phosphorylation of Cdc2 (see Figure 7A) might contribute to its inactivation after GVBD, a regulatory mechanism absent from control oocytes. We further analyzed the reactivation of Cdc2 after GVBD by monitoring the accumulation of Cyclins B1 and B2. In both control and morpholino antisense-injected oocytes, Cyclin B2 was shifted to a slower migrating form, reflecting Cdc2 activation by early GVBD (Figure 3A). The amounts of Cyclins B2 and B1 decreased after GVBD and subsequently increased again, although with a slower time course in morpholino-injected oocytes (Figure 3A and B). In addition, we analyzed Cdc27 phosphorylation level, as a representation of APC regulation (Gross et al., 2000). At the time of GVBD, Cdc27 underwent a characteristic shift in its electrophoretic mobility (Figure 3C). This hyperphosphorylated form reappeared 2–3 h after GVBD, although with a delay in morpholino-injected oocytes (Figure 3C), in correlation with a slower Cyclin B accumulation (Figure 3A and B; Gross et al., 2000). These results suggest that the absence of Mos influences the rate of Cyclin B degradation and re-accumulation.

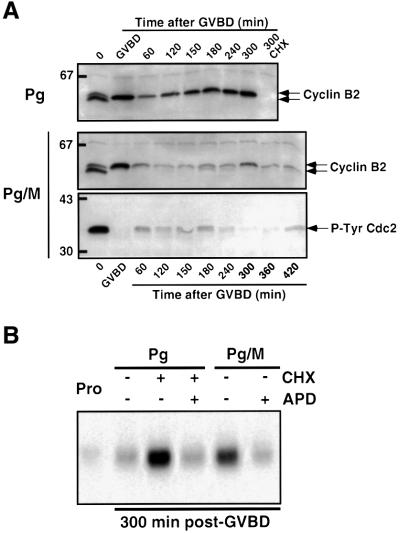

Fig. 7. Analysis of Cyclin B2 levels, Cdc2 phosphorylation and DNA replication in Mos-ablated oocytes after GVBD. (A) Oocytes were injected or not with morpholino antisense (M). Six hours later, progesterone (Pg) was added (time 0). Some of the progesterone-treated oocytes were incubated 45 min after GVBD in CHX. Oocytes were collected at indicated times and immunoblotted with antibodies against Xenopus Cyclin B2 and Tyr15-phosphorylated form of Cdc2. GVBD occurred 5 h after progesterone addition in control oocytes and 3 h later in morpholino antisense-injected oocytes. (B) In parallel, 1 h after progesterone addition, oocytes were injected with [α-32P]dCTP (50 nl, 3000 Ci/mmol). Aphidicolin (APD) was added at the time of GVBD and CHX 45 min after GVBD. Five hours after GVBD, DNA was extracted and incorporation of radioactive dCTP was visualized by autoradiography. Each lane corresponds to the equivalent of one oocyte. Prophase oocytes (Pro) were also injected with [α-32P]dCTP and collected 10 h after GVBD occurring in the control oocytes.

Fig. 3. Cyclin B degradation is not affected in the absence of Mos. Oocytes were injected or not with morpholino antisense (M). One hour later (time 0), progesterone (Pg) was added and oocytes were homogenized at the indicated times. One oocyte equivalent was loaded in each lane and immunoblots were performed with antibodies against (A) Xenopus Cyclin B2, (B) Xenopus Cyclin B1 and (C) Cdc27. Oocyte lysates were originated from the experiment already described in Figure 2. The positions of the molecular weight markers are indicated on the left.

Mos ablation prevents MAPK activation

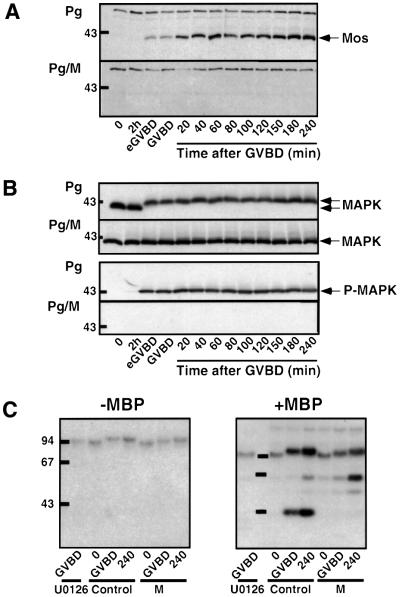

Since even trace amounts of Mos are sufficient to activate MAPK, which could in turn activate Cdc2, it was important to ascertain that Mos did not re-accumulate during the 4 h period following GVBD in morpholino-injected oocytes. In progesterone-treated oocytes, Mos started to accumulate by early GVBD (eGVBD), in correlation with MAPK phosphorylation, visualized either by its electrophoretic retardation using an anti-MAPK antibody or by an anti-phospho-MAPK (Figure 4A and B). In contrast, in morpholino-injected oocytes, Mos remained undetectable and MAPK remained unphosphorylated (Figure 4A and B), even though MAPK was present at a constant level (Figure 4B). The absence of any MAPK activity was confirmed directly by an in-gel MBP kinase assay. As expected, a 42 kDa radioactive band appeared in uninjected control oocytes at GVBD and increased in intensity by 4 h after progesterone treatment (Figure 4C). Injection of morpholino antisense or addition of the MEK inhibitor, U0126, totally prevented the appearance of this radioactive band, even 4 h after GVBD (Figure 4C).

Fig. 4. Mos ablation prevents MAPK activation induced by progesterone. Oocytes were injected or not with morpholino antisense (M) and incubated in the presence of progesterone (Pg) 1 h later (time 0). Oocytes were collected at indicated times and lysates originated from the experiment illustrated in Figure 2 were immunoblotted with the antibodies directed against (A) Xenopus Mos and (B) total MAPK or the active phosphorylated form of MAPK (P-MAPK). The positions of the molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. (C) In-gel assay of MBP kinase activities. Oocytes were injected or not with morpholino antisense (M) or incubated in the presence of 50 µM U0126. One hour after injection or 20 min after incubation in U0126, progesterone was added (time 0) and oocytes were collected either at time 0 or at GVBD or 4 h after GVBD (240). MBP kinase activity was measured by an in-gel assay after adding (+MBP) or not (–MBP) myelin basic protein in the gel. The equivalent of one oocyte was loaded per lane. The positions of the molecular weight markers are indicated on the left.

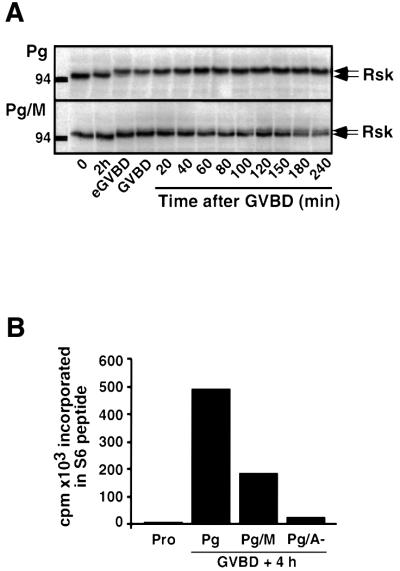

Rsk is partially activated in the absence of Mos and MAPK activity

In the absence of active MAPK, the injection of a constitutively active form of Rsk has been shown to restore Cyclin B accumulation after GVBD, leading to the reactivation of Cdc2 (Gross et al., 2000). In morpholino-injected oocytes, Cdc2 reactivation occurred after GVBD, although MAPK was inactive. Since Rsk can be activated in the absence of any MAPK activity in other cell types (Kalab et al., 1996; Jensen et al., 1999), we evaluated the possibility that Rsk could still have been activated under our conditions. First, we looked at the electrophoretic mobility of Rsk, which is known to correlate with its phosphorylation and activation state (Figure 5A). In progesterone-treated oocytes, Rsk underwent an electrophoretic retardation starting at eGVBD (Figure 5A), in parallel with MAPK activation (Figure 4B). In morpholino-injected oocytes, Rsk exhibited only a partial shift of its electrophoretic mobility starting at eGVBD (Figure 5A). We then directly assayed the activity of Rsk that had been immunoprecipitated 4 h after GVBD (Figure 5B). In morpholino-injected oocytes, Rsk activity was about half that of control oocytes, whereas it was completely inactive in oocytes injected with conventional A– antisense oligonucleotides (Figure 5B). To ascertain whether or not the partial activation of Rsk was responsible for the initial activation of Cdc2 in response to progesterone, morpholino-injected oocytes were incubated in the presence of U0126, which is known to suppress Rsk activation in the oocyte (Gross et al., 2000). Under these conditions, Cdc2 was still activated in response to progesterone, although Mos was not expressed and both MAPK and Rsk remained inactive (data not shown). Altogether, these results suggest that progesterone treatment leads to the activation of a U0126-sensitive pathway in Xenopus oocytes that is independent of Mos and active MAPK, but which can still lead to a partial activation of Rsk. It also indicates that the partially activated form of Rsk, if not necessary for the initial activation of Cdc2 induced by progesterone, could still be sufficient for Cdc2 re-activation after GVBD.

Fig. 5. Rsk is partially activated in the absence of Mos and MAPK activation. (A) Oocytes were injected or not with morpholino antisense (M). One hour later, progesterone (Pg) was added (time 0) and oocytes were homogenized at the indicated times. Oocyte extracts originated from the experiment illustrated in Figure 2 were immunoblotted with an antibody against Rsk2. (B) Oocytes were injected or not with either morpholino antisense (M) or traditional antisense (A–) oligonucleotides and were incubated in the presence of progesterone (Pg). Groups of 10 oocytes, either at prophase stage (Pro) or 4 h after GVBD (GVBD + 4 h) were homogenized and immunoprecipitated with the anti-Rsk2 antibody. Kinase activity was assayed using S6 peptide in immunoprecipitates.

Mos is required to stabilize Cdc2 and to prevent DNA replication after meiosis I

Since Xenopus oocytes were able to mature in the absence of Mos when injected with morpholino antisense oligonucleotides, we next asked whether, in the absence of Mos, oocytes would arrest meiosis at metaphase II. We measured Cdc2 kinase activity after meiosis I, at a time when control uninjected oocytes had already arrested at metaphase II, as a result of CSF activity. In such uninjected progesterone-treated oocytes, Cdc2 activity reappeared after GVBD and stabilized at a high level for at least 5 h (Figure 6A). In contrast, in Mos-ablated oocytes, Cdc2 activity started to fluctuate after its initial reappearance following GVBD, alternating between high and low activity during the following 5 h (Figure 6A). As described above, in these Mos-ablated oocytes, the activity of Rsk was half that of the control progesterone-treated oocytes (Figure 6A). The external morphology of Mos-depleted oocytes also started to change 3 h after GVBD by exhibiting a pigment rearrangement similar to those seen after the parthenogenetic activation of eggs (Figure 6A, panel c). During this post-GVBD period, Mos was absent and MAPK activity was undetectable (data not shown). In Mos-ablated oocytes, the injection of Xenopus MBP–Mos protein at GVBD was sufficient to restore a full level of Rsk activity (Figure 6A) and a full-sustained level of Cdc2 activity (Figure 6B). Moreover, it prevented the abnormalities of the oocyte external morphology (Figure 6A, panel b), demonstrating that our observations were a consequence of Mos ablation. An identical rescue of Mos-ablation defects was obtained by microinjection of mouse Mos mRNA, which lacks the 5′ UTR-specific target sequence for morpholino antisense (data not shown).

After meiosis I, Mos-ablated oocytes could either progress through meiotic-like cell cycles, consisting of consecutive M phases without intervening S phase, or start mitotic-like cell cycles characterized by an alternation of S and M phases. We therefore analyzed Cyclin B2 levels (Figure 7A) and DNA synthesis (Figure 7B) in control and Mos-ablated oocytes. In progesterone-treated control oocytes, Cyclin B2 re-accumulated rapidly after meiosis I and remained stable throughout the metaphase II arrest (Figure 7A). In the absence of Mos, levels of Cyclin B2 strongly decreased after GVBD, re-accumulated after a delay and to lower levels than in control oocytes, peaked at 300 min after GVBD, and then decreased again. A faster migrating form of Cyclin B2 was detected during the period between 180 and 240 min (in the experiment illustrated in Figure 7A), due to its association with a form of Cdc2 that was phosphorylated on Tyr15 (Figure 7A and see also the Cdc25 phosphorylation level in Figure 2D). We then investigated DNA replication by measuring the incorporation of radioactive deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP) into genomic DNA, 300 min after GVBD. As shown in Figure 7B, prophase oocytes and control metaphase II-arrested oocytes did not incorporate radioactive dCTP. Inhibition of protein synthesis shortly after GVBD induced Cyclin B2 degradation (Figure 7A), the entry into interphase and the formation of replicative nuclei in the oocytes (Huchon et al., 1993; Furuno et al., 1994). As expected, progesterone-treated oocytes underwent DNA replication when CHX was added shortly after GVBD, providing a positive control (Figure 7B). Morpholino-injected oocytes incorporated radioactive dCTP to the same extent as CHX-treated oocytes (Figure 7B). In both experiments, aphidicolin, a specific inhibitor of DNA polymerase α (Furuno et al., 1994), abolished dCTP incorporation (Figure 7B). Therefore, in the absence of Mos, oocytes do not complete meiosis and instead directly enter in mitotic cell cycles.

Discussion

One of the key regulators of meiosis is the product of the proto-oncogene c-mos, which is specifically expressed in germ cells and functions only during meiotic maturation. In this study, we used morpholino antisense oligonucleotides to inhibit Mos translation induced by progesterone without preventing the initiation of meiotic maturation. Because this new experimental approach does not block the initial activation of Cdc2 induced by progesterone, we were able to investigate the exact requirements for Mos during the three periods of Xenopus oocyte meiotic maturation: the entry into meiosis I, the metaphase I to metaphase II transition characterized by the absence of S phase, and the metaphase II arrest. Here, we provide evidence that progesterone is able to activate a pathway independent of Mos synthesis leading to Cdc2 activation and GVBD. After GVBD, Mos is also dispensable for the activation of Cdc2 and the accumulation of Cyclin B, providing that Rsk is active. However, in the absence of Mos, the activity of Cdc2 is not stabilized. Cyclin B levels oscillate, Cdc2 is partially rephosphorylated on tyrosine, and genomic DNA undergoes replication. This series of events mimic the mitotic cell cycles of the early embryos.

It has been shown, 14 years ago by microinjection of conventional antisense oligonucleotides, that Mos synthesis is required for Cdc2 activation in response to progesterone. On the other hand, two reports recently showed that MAPK, the target of Mos, is not necessary for Cdc2 activation after progesterone stimulation (Fisher et al., 1999; Gross et al., 2000). In the present work, we used morpholino antisense oligonucleotides to clarify these contradictory results by inhibiting both Mos synthesis and the downstream activation of MAPK, as well as other unknown targets of Mos. Our results show that Cdc2 can be activated in Xenopus oocytes by a pathway that does not require Mos synthesis or elevated MAPK activity. These results are consistent with results in starfish and mammals (Colledge et al., 1994; Hashimoto et al., 1994; Tachibana et al., 2000). Therefore, although exogenous Mos is able to induce GVBD, it is not necessary and the synthesis of new unidentified protein(s) is still required to control Cdc2 activation after progesterone treatment. An attractive candidate as a protein neosynthetized in response to progesterone and necessary for Cdc2 activation is the RINGO/Speedy protein, a non-conventional activatory partner of Cdc2 (Ferby et al., 1999; Lenormand et al., 1999; Karaiskou et al., 2001). The reproducible delay observed in Cdc2 activation was rescued in morpholino-injected oocytes by the injection of Mos mouse mRNA (data not shown), indicating that the Mos/MEK/MAPK/Rsk pathway contributes to the kinetics of MPF activation, as described previously (Fisher et al., 1999; Gross et al., 2000, 2001). This contribution is probably achieved through the inhibition of a negative regulator of Cdc2, the Myt1 kinase. Myt1 could be downregulated directly by Rsk (Palmer et al., 1998), by Akt as reported for starfish oocytes (Okumura et al., 2002) or by Mos as suggested by Peter et al. (2002). According to Peter et al. (2002), the absence of Mos leads to a delayed Myt1 inactivation, explaining why Cdc2 activation, hence GVBD, are delayed in morpholino-injected oocytes. Nevertheless, the Mos protein and the MAPK/Rsk activities remain dispensable since their suppression by morpholino antisense or by U0126, respectively, prevents neither Cdc2 activation nor GVBD induction in response to progesterone (Gross et al., 2000; our data).

Some hypotheses could be postulated to explain why the response is different when morpholino oligonucleotides are used for Mos ablation instead of conventional oligonucleotides. Morpholinos block translation by an RNase–H-independent mechanism leaving the target mRNA intact (Summerton and Weller, 1997), while conventional oligonucleotides induce RNase–H cleavage of the mRNA, generating 3′ and 5′ fragments (Ballantyne et al., 1997). The possibility that these fragments prevent the synthesis of protein(s) required for meiotic maturation non-specifically, through a general inhibition of translation, cannot be excluded. Another interesting possibility is that the mRNA encoding Mos could itself play a role in the meiotic maturation. The degradation of the mRNA induced by the injection of conventional oligonucleotides could, for example, lead to the release of some regulatory RNA-binding proteins such as OMA1 and OMA2, which have been reported to function upstream of Myt1 in Caenorhabditis elegans (Detwiler et al., 2001). Further more, the RNase–H action could generate new stable mRNA fragments encoding for N-terminal-truncated proteins, as has been recently described (Thoma et al., 2001). These proteins could interfere with meiotic maturation. Therefore, there are a variety of potential mechanisms by which conventional DNA antisense oligonucleotides targeted to different regions of the Mos mRNA could block progesterone-induced meiotic maturation in Xenopus. However, our results clearly show that Cdc2 activation and GVBD can take place in the absence of Mos synthesis. Hence, our results resolve the long-standing inconsistencies concerning the roles of Mos during oocyte maturation that were deduced from studies in different species. Moreover, our findings completely revise the view that Mos is an essential component of the progesterone signaling pathway leading to the initial activation of Cdc2 in Xenopus oocytes. The crucial function of the Mos/MAPK cascade now appears much more similar in animal species than thought previously, and seems to be a consequence of the Cdc2 activation rather than a Mos-dependent trigger of Cdc2 activation (Nebreda et al., 1995; Frank-Vaillant et al., 1999). Nevertheless, this pathway must play a role during metaphase I, most probably at the level of spindle assembly or dynamics (Zhou et al., 1991; Verlhac et al., 1994, 1996; Choi et al., 1996).

When MAPK and Rsk activation is prevented by U0126, the initial activation of Cdc2 occurs, and Mos accumulates in response to progesterone (Gross et al., 2000). However, after meiosis I, Cyclin B fails to re-accumulate, and both Cdc2 and Rsk remain inactive despite the presence of Mos. Oocytes then fail to reach meiosis II and instead enter an interphase-like stage. The injection of a constitutively active Rsk restores Cyclin B protein levels, the post-GVBD reactivation of Cdc2 and the metaphase II arrest (Gross et al., 2000). In contrast, in morpholino-injected oocytes, the accumulation of Cyclin B after GVBD is not impaired and Cdc2 reappears. This difference is probably due to the fact that Rsk is partially activated after the Mos ablation by morpholinos, while it is never activated after U0126 treatment. The high concentrations of U0126 (50 µM) required to inhibit MAPK activation in the amphibian oocyte (Gross et al., 2000) could explain the differences in Rsk activity seen under these experimental conditions. The U0126 concentrations used in these experiments would be expected to inhibit the desired targets, MEK1/2, but also other protein kinases such as p70S6K, PRAK, PKB or p38 (Davies et al., 2000). Consequently, other pathways, including a Mos-independent pathway that activates Rsk, would be blocked in addition to the MEK/MAPK pathway. This interpretation is supported by our observations that the addition of U0126 to morpholino-injected oocytes totally abolishes Rsk activity. Therefore, an alternative pathway, independent of the Mos/MAPK pathway but sensitive to 50 µM U0126, may be involved in the partial activation of Rsk. In mouse meiotic maturation, a partial phosphorylation and activation of Rsk has been reported in the absence of Mos and MAPK activity (Kalab et al., 1996). In this species, two sequentially activated pathways contribute to Rsk activation. The first level of phosphorylation and activation of Rsk is reached 1 h after GVBD, before any MAPK activation. The full activation of Rsk is then achieved 1 h later, at the time of MAPK activation (Kalab et al., 1996). In mammalian cells, it has been demonstrated that the level of Rsk activity depends on a balanced input from two kinases: PDK1 (3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1) and MAPK (Jensen et al., 1999). Rsk is composed of two kinase domains called N-terminal kinase (NTK) and C-terminal kinase (CTK), separated by a linker region. PDK1 phosphorylates and activates the NTK domain (Jensen et al., 1999; Richards et al., 1999), while MAPK phosphorylates the linker and the CTK domain, leading to its activation (Fisher and Blenis, 1996; Dalby et al., 1998). Although MAPK is required for the full activation of Rsk, the phosphorylation of full-length Rsk2 by ectopic PDK1 induces its partial activation, without the involvement of MAPK (Jensen et al., 1999). In addition, Rsk cannot be activated by MAPK in the absence of PDK1 activity, suggesting that PDK1 and MAPK should act hierarchically (Jensen et al., 1999). A PDK1-like activity in Xenopus oocytes is likely to be responsible for the partial activation of Rsk observed in Mos-depleted oocytes. In vitro, it has been demonstrated that a CTK-deleted Rsk, whose activity depends only on its phosphorylation by PDK1, was partially activated by human PDK1 (Gross et al., 1999). This construct was activated during incubation into Xenopus oocyte M phase extracts, but poorly in prophase extracts (Gross et al., 2001), suggesting that this PDK1-like activity is cell cycle regulated.

In Xenopus, the CSF activity of Mos was demonstrated by the injection of either mRNA or recombinant protein into a two-cell stage embryo resulting in a cell cycle arrest at metaphase in the injected blastomere (Sagata et al., 1989b). Here, for the first time, we were able to follow the whole maturation process in the absence of Mos and, thus, to study the behavior of a Mos-ablated Xenopus oocyte during the transition from meiosis I to meiosis II. Our results show that Cdc2 kinase activity cycles and cannot be stabilized after GVBD in the absence of Mos. Cdc2 is transiently rephosphorylated on tyrosine, Cyclin B levels oscillate and oocytes replicate DNA after meiosis I. We were unable to detect any meiotic spindle or polar body extrusion in Mos-ablated oocytes (data not shown). Therefore, in the absence of Mos and despite the presence of partially active Rsk, oocytes fail to undergo a CSF arrest at metaphase II, and instead enter a series of mitotic-like cell cycles. This behavior is similar to the one described in Mos-ablated starfish oocytes, which undergo 3–4 Cdc2 cycles after meiosis I (Tachibana et al., 2000). The primary effect of the Mos/MAPK pathway might be to regulate Cdc2 activity during the interkinesis between metaphase I and metaphase II. When present, this pathway could prevent the inactivation of Cdc2 by tyrosine phosphorylation or could decrease the efficiency of APC towards Cyclin B. It is highly possible that this link between the Mos/MAPK/Rsk pathway and the Cyclin B degradation machinery (APC) could involve the new Cdc20 binding protein, Emi1 (Reimann et al., 2001; Reimann and Jackson, 2002). It could also stimulate Cyclin B translation, leading to a precocious reactivation of Cdc2 required for the entry into metaphase II without interphase. How Mos and MAPK are molecularly coupled either to the control of the Cyclin mRNA translation, or to the regulators of Cdc2 phosphorylation, Myt1/Wee1 and Cdc25, then represents an important aim. Moreover, it has been clearly described that the Mos/MAPK pathway regulates the meiotic spindle organization in mouse oocytes (Choi et al., 1996; Verlhac et al., 1996). This pathway is also certainly implicated in Xenopus oocytes, since no spindle and no polar body extrusion were detected in the absence of Mos or active MAPK (Gross et al., 2000; our data). Because in Mos-ablated oocytes a normal phenotype was totally restored by the reinstatement of recombinant Mos or by the in vivo translation of morpholino-resistant Mos mRNA, this protein could be considered as necessary and sufficient to prevent premature mitotic cell cycles until fertilization. These observations are different from what has been described previously in mouse oocytes. Although Mos–/– mice oocytes do not arrest in metaphase II (Colledge et al., 1994; Hashimoto et al., 1994; Verlhac et al., 1996), Cdc2 activity does not oscillate, and 76% of oocytes arrest at a ‘metaphase III’ stage (Verlhac et al., 1996). In addition, Mos–/– oocytes do not replicate DNA between metaphase I and metaphase II, despite going through an interphase-like stage (Verlhac et al., 1996). This is probably because mouse oocytes do not acquire functional replicative machinery before metaphase II, in contrast to starfish and Xenopus oocytes that develop the ability to replicate DNA early after GVBD (Furuno et al., 1994; Tachibana et al., 1997). The spindle checkpoint, defective in starfish and Xenopus embryos (Hara et al., 1980; Gerhart et al., 1984; Vee et al., 2001), but active in both mouse oocytes and embryos (Kubiak et al., 1993; Winston et al., 1995), probably ensures the ‘metaphase III’ arrest in mouse oocytes and could also account for these inter-species differences.

In conclusion, the specific role that Mos plays in meiosis is the prevention of mitotic cell cycles after meiosis I and the generation of a cell cycle-arrested gamete awaiting fertilization. This role now appears to be universal, since it is found in oocytes from organisms as diverse as Xenopus, starfish, goldfish and mice.

Materials and methods

Materials

Xenopus laevis adult females (CNRS, Rennes, France) were bred and maintained under laboratory conditions. [γ-32P]ATP, [α-32P]dCTP and [35S]methionine were purchased from Dupont NEN (Boston, MA). Reagents, unless otherwise specified, were from Sigma (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). Morpholinos and conventional DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Gene Tools LLC and Eurogentec, respectively. The sequence of both antisense morpholinos and conventional DNA oligonucleotides used was AAGGCATTGCTGTGTGACTCGCTGA, as described previously (Sagata et al., 1988), and the sequence of both control morpholinos and ‘traditional’ DNA oligos used was TAGACAATGCTCTGTGGCTCGGTGA. Recombinant MBP–Mos protein was bacterially expressed and prepared as described previously (Roy et al., 1996).

Preparation and handling of oocytes

Fully grown Xenopus prophase oocytes were obtained as described by Jessus et al. (1987). The usual microinjected volume was 50 nl per oocyte. Progesterone and U0126 (Promega) were used in the external medium at final concentrations of 2 and 50 µM, respectively. Oocytes were referred as to eGVBD when the first pigment rearrangement was detected at the animal pole, and as GVBD when a well-defined white spot was formed. In all experiments, GVBD was ascertained by dissection of TCA-fixed oocytes. For extract preparations, oocytes were lysed in 10 vols of EB [80 mM β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM EGTA, 15 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) pH 7.3] supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma) and then centrifuged at 15 000 g for 10 min at 4°C.

Antibodies, western blotting and immunoprecipitations

Western blots were performed as described (Frank-Vaillant et al., 1999). The antibodies used were: rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the Xenopus Mos protein (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) for western blotting, monoclonal mouse anti-Mos antibodies (R38 and R97, a kind gift from Dr J.Gannon, ICRF, UK) for immunoprecipitation, sheep polyclonal antibodies raised against Xenopus Cyclin B2 or B1 and rabbit polyclonal antibody against Cdc25 (kind gifts from Dr J.Maller, HHMI, CO), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Tyr15-phosphorylated Cdc2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), mouse monoclonal antibody against Cdc27 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against total ERK (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), mouse monoclonal antibodies against the active phosphorylated form of MAPK, P-MAPK (New England Biolabs) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Rsk2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). The appropriate horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) were revealed by chemiluminescence (NEN). Immunoprecipitations of Mos and Rsk were performed according to Nebreda et al. (1995) and Gross et al. (1999), respectively.

Kinase assays

Cdc2 activity (equivalent to three or four oocytes) was assayed using histone H1 as a substrate after affinity purification on p13suc1 beads as described (Jessus et al., 1991). MBP kinase activity was measured by an in-gel assay after adding or not myelin basic protein (MBP from bovine brain, Sigma) in the electrophoresis gels, as described (Durocher and Chevalier, 1994). For the Rsk activity assay, lysates from 4–10 oocytes were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Rsk2 antibody, and the kinase assay was performed in immunoprecipitates in the presence of 250 µM S6 peptide (kind gift from Dr J.Goris, Belgium), as described previously (Gross et al., 1999).

Analysis of DNA synthesis

[α-32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol, 10 mCi/ml) was injected 1 h after progesterone addition. For analysis, 10 oocytes were lysed in homogenization buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) and treated with proteinase K (100 µg/ml) at 55°C overnight. After successive extractions by an equal volume of phenol, phenol/chloroform and chloroform, DNA was precipitated by 0.6 vols of isopropanol at –20°C and re-suspended in 100 µl of TE (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA). After treatment by RNase T1 (10 µg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature, samples were submitted to 0.9% agarose gel electrophoresis (one oocyte equivalent per lane). Incorporation of radioactive dCTP was revealed by autoradiography after migration. CHX (10 µg/ml) was added to the medium within 45 min after GVBD, and aphidicolin (20 µg/ml) at the time of GVBD, before detectable DNA synthesis occurred in CHX-treated controls.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr T.Hunt for anti-Mos antibodies and valuable advice, Dr J.Goris for S6 peptide, Dr E.Houliston, Dr A.Karaiskou, Dr M.-H.Verlhac and Dr M.Lohka for critical reading of the manuscript, Dr J.Maller for anti-Cdc25, Cyclins B1 and B2 antibodies, Dr M.-H.Verlhac for mouse RNA and all the members of the laboratory for their support. This work was supported by grants from INRA, CNRS, University Pierre and Marie Curie, ARC (No. 5899 to C.J.) and IFR–BI (to O.H.).

References

- Ballantyne S., Daniel,D.L. and Wickens,M. (1997) A dependent pathway of cytoplasmic polyadenylation reactions linked to cell cycle control by c-mos and CDK1 activation. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 1633–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt R.R. and Ferrell,J.E.,Jr (1999) The protein kinase p90rsk as an essential mediator of cytostatic factor activity. Science, 286, 1362–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi T., Rulong,S., Resau,J., Fukasawa,K., Matten,W., Kuriyama,R., Mansour,S., Ahn,N. and Van de Woude,G.F. (1996) Mos/mitogen-activated protein kinase can induce early meiotic phenotypes in the absence of maturation-promoting factor—a novel system for analyzing spindle formation during meiosis I. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 4730–4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge W.H., Carlton,M.B.L., Udy,G.B. and Evans,M.J. (1994) Disruption of c-mos causes parthenogenetic development of unfertilized mouse eggs. Nature, 370, 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar I., Paules,R.S. and Van de Woude,G.F. (1991) A characterization of cytostatic factor activity from Xenopus eggs and c-mos-transformed cells. J. Cell Biol., 114, 329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalby K.N., Morrice,N., Caudwell,F.B., Avruch,J. and Cohen,P. (1998) Identification of regulatory phosphorylation sites in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein kinase-1a/p90rsk that are inducible by MAPK. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 1496–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S.P., Reddy,H., Caivano,M. and Cohen,P. (2000) Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem. J., 351, 95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detwiler M.R., Reuben,M., Li,X., Rogers,E. and Lin,R. (2001) Two zinc finger proteins, OMA-1 and OMA-2, are redundantly required for oocyte maturation in C. elegans. Dev. Cell, 1, 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durocher Y. and Chevalier,S. (1994) Detection of phosphotyrosine in glutaraldehyde-crosslinked and alkali-treated phosphoproteins following their partial acid hydrolysis in gels. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods, 28, 101–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferby I., Blazquez,M., Palmer,A., Eritja,R. and Nebreda,A.R. (1999) A novel p34cdc2-binding and activating protein that is necessary and sufficient to trigger G2/M progression in Xenopus oocytes. Genes Dev., 13, 2177–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D.L., Brassac,T., Galas,S. and Doree,M. (1999) Dissociation of MAP kinase activation and MPF activation in hormone-stimulated maturation of Xenopus oocytes. Development, 126, 4537–4546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher T.L. and Blenis,J. (1996) Evidence for two catalytically active kinase domains in pp90rsk. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 1212–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank-Vaillant M., Jessus,C., Ozon,R., Maller,J.L. and Haccard,O. (1999) Two distinct mechanisms control the accumulation of cyclin B1 and mos in Xenopus oocytes in response to progesterone. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 3279–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuno N., Nishizawa,M., Okazaki,K., Tanaka,H., Iwashita,J., Nakajo,N., Ogawa,Y. and Sagata,N. (1994) Suppression of DNA replication via Mos function during meiotic divisions in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 13, 2399–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart J., Wu,M. and Kirschner,M. (1984) Cell cycle dynamics of an M-phase-specific cytoplasmic factor in Xenopus laevis oocytes and eggs. J. Cell Biol., 98, 1247–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S.D., Schwab,M.S., Lewellyn,A.L. and Maller,J.L. (1999) Induction of metaphase arrest in cleaving Xenopus embryos by the protein kinase p90Rsk. Science, 286, 1365–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S.D., Schwab,M.S., Taieb,F.E., Lewellyn,A.L., Qian,Y.W. and Maller,J.L. (2000) The critical role of the MAP kinase pathway in meiosis II in Xenopus oocytes is mediated by p90Rsk. Curr. Biol., 10, 430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S.D., Lewellyn,A.L. and Maller,J.L. (2001) A constitutively active form of the protein kinase p90Rsk1 is sufficient to trigger the G2/M transition in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 46099–46103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haccard O., Sarcevic,B., Lewellyn,A., Hartley,R., Roy,L., Izumi,T., Erikson,E. and Maller,J.L. (1993) Induction of metaphase arrest in cleaving Xenopus embryos by MAP kinase. Science, 262, 1262–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haccard O., Lewellyn,A., Hartley,R.S., Erikson,E. and Maller,J.L. (1995) Induction of Xenopus oocyte meiotic maturation by MAP kinase. Dev. Biol., 168, 677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K., Tydeman,P. and Kirschner,M. (1980) A cytoplasmic clock with the same period as the division cyle in Xenopus eggs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 462–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto N. et al. (1994) Parthenogenetic activation of oocytes in c-mos-deficient mice. Nature, 370, 68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman J., Kofron,M. and Wylie,C. (2000) β-catenin signaling activity dissected in the early Xenopus embryo: a novel antisense approach. Dev. Biol., 222, 124–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Kessler,D. and Erikson,R. (1995) Biochemical and biological analysis of Mek1 phosphorylation site mutants. Mol. Biol. Cell, 6, 237–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huchon D., Rime,H., Jessus,C. and Ozon,R. (1993) Control of metaphase-I formation in Xenopus oocyte: effects of an indestructible cyclin-B and of protein synthesis. Biol. Cell, 77, 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen C.J., Buch,M.B., Krag,T.O., Hemmings,B.A., Gammeltoft,S. and Frodin,M. (1999) 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase is phosphorylated and activated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 27168–27176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessus C., Thibier,C. and Ozon,R. (1987) Levels of microtubules during the meiotic maturation of the Xenopus oocyte. J. Cell Sci., 87, 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessus C., Rime,H., Haccard,O., Van Lint,J., Goris,J., Merlevede,W. and Ozon,R. (1991) Tyrosine phosphorylation of p34cdc2 and p42 during meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocyte. Antagonistic action of okadaic acid and 6-DMAP. Development, 111, 813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiura-Kobayashi H., Yoshida,N., Sagata,N., Yamashita,M. and Nagahama,Y. (2000) The Mos/MAPK pathway is involved in metaphase II arrest as a cytostatic factor but is neither necessary nor sufficient for initiating oocyte maturation in goldfish. Dev. Genes Evol., 210, 416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P., Kubiak,J.Z., Verlhac,M.H., Colledge,W.H. and Maro,B. (1996) Activation of P90rsk during meiotic maturation and first mitosis in mouse oocytes and eggs—map kinase-independent and -dependent activation. Development, 122, 1957–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaiskou A., Perez,L.H., Ferby,I., Ozon,R., Jessus,C. and Nebreda,A.R. (2001) Differential regulation of Cdc2 and Cdk2 by RINGO and cyclins. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 36028–36034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak J.Z., Weber,M., Depennart,H., Winston,N.J. and Maro,B. (1993) The metaphase-II arrest in mouse oocytes is controlled through microtubule-dependent destruction of Cyclin-B in the presence of CSF. EMBO J., 12, 3773–3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenormand J.L., Dellinger,R.W., Knudsen,K.E., Subramani,S. and Donoghue,D.J. (1999) Speedy: a novel cell cycle regulator of the G2/M transition. EMBO J., 18, 1869–1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui Y. and Markert,C.L. (1971) Cytoplasmic control of nuclear behavior during meiotic maturation of frog oocytes. J. Exp. Zool., 177, 129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebreda A.R. and Ferby,I. (2000) Regulation of the meiotic cell cycle in oocytes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebreda A.R., Hill,C., Gomez,N., Cohen,P. and Hunt,T. (1993) The protein kinase mos activates MAP kinase kinase in vitro and stimulates the MAP kinase pathway in mammalian somatic cells in vivo. FEBS Lett., 333, 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebreda A.R., Gannon,J. and Hunt,T. (1995) Newly synthesized protein(s) must associate with p34cdc2 to activate MAP kinase and MPF during progesterone-induced maturation of Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 14, 5597–5607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura E., Fukuhara,T., Yoshida,H., Hanada Si,S., Kozutsumi,R., Mori,M., Tachibana,K. and Kishimoto,T. (2002) Akt inhibits Myt1 in the signalling pathway that leads to meiotic G2/M-phase transition. Nat. Cell Biol., 4, 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe S.J., Wolfes,H., Kiessling,A.A. and Cooper,G.M. (1989) Microinjection of antisense c-mos oligonucleotides prevents meiosis II in the maturing mouse egg. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 7038–7042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe S.J., Kiessling,A.A. and Cooper,G.M. (1991) The c-mos gene product is required for cyclin B accumulation during meiosis of mouse eggs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 7869–7872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskarsson M., McClements,W.L., Blair,D.G., Maizel,J.V. and Van de Woude,G.F. (1980) Properties of a normal mouse cell DNA sequence (sarc) homologous to the src sequence of Moloney sarcoma virus. Science, 207, 1222–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A., Gavin,A.C. and Nebreda,A.R. (1998) A link between MAP kinase and p34cdc2/cyclin B during oocyte maturation: p90rsk phosphorylates and inactivates the p34cdc2 inhibitory kinase myt1. EMBO J., 17, 5037–5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paules R.S., Buccione,R., Moschel,R.C., Van de Woude,G.F. and Eppig,J.J. (1989) Mouse Mos protooncogene product is present and functions during oogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 5395–5399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter M., Labbe,J.C., Doree,M. and Mandart,E. (2002) A new role for Mos in Xenopus oocyte maturation: targeting Myt1 independently of MAPK. Development, 129, 2129–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada J., Yew,N., Ahn,N.G., Van de Woude,G.F. and Cooper,J.A. (1993) Mos stimulates MAP kinase in Xenopus oocytes and activates a MAP kinase kinase in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 2546–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann J.D. and Jackson,P.K. (2002) Emi1 is required for cytostatic factor arrest in vertebrate eggs. Nature, 416, 850–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann J.D., Freed,E., Hsu,J.Y., Kramer,E.R., Peters,J.M. and Jackson,P.K. (2001) Emi1 is a mitotic regulator that interacts with Cdc20 and inhibits the anaphase promoting complex. Cell, 105, 645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S.A., Fu,J., Romanelli,A., Shimamura,A. and Blenis,J. (1999) Ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (RSK1) activation requires signals dependent on and independent of the MAP kinase ERK. Curr. Biol., 9, 810–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy L.M., Haccard,O., Izumi,T., Lattes,B.G., Lewellyn,A.L. and Maller,J.L. (1996) Mos proto-oncogene function during oocyte maturation in Xenopus. Oncogene, 12, 2203–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler K.C. and Ruderman,J.V. (1998) Components of the signaling pathway linking the 1-methyladenine receptor to MPF activation and maturation in starfish oocytes. Dev. Biol., 197, 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N., Oskarsson,M., Copeland,T., Brumbaugh,J. and Van de Woude,G.F. (1988) Function of c-mos proto-oncogene product in meiotic maturation in Xenopus oocytes. Nature, 335, 519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N., Daar,I., Oskarsson,M., Showalter,S.D. and Van de Woude,G.F. (1989a) The product of the mos proto-oncogene as a candidate ‘initiator’ for oocyte maturation. Science, 245, 643–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N., Watanabe,N., Van de Woude,G.F. and Ikawa,Y. (1989b) The c-mos proto-oncogene product is a cytostatic factor responsible for meiotic arrest in vertebrate eggs. Nature, 342, 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya E. and Ruderman,J. (1993) Mos induces the in vitro activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in lysates of frog oocytes and mammalian somatic cells. Mol. Biol. Cell, 4, 781–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerton J. and Weller,D. (1997) Morpholino antisense oligomers: design, preparation and properties. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev., 7, 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana K., Machida,T., Nomura,Y. and Kishimoto,T. (1997) MAP kinase links the fertilization signal transduction pathway to the G1/S-phase transition in starfish eggs. EMBO J., 16, 4333–4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana K., Tanaka,D., Isobe,T. and Kishimoto,T. (2000) c-Mos forces the mitotic cell cycle to undergo meiosis II to produce haploid gametes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 14301–14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma C. et al. (2001) Generation of stable mRNA fragments and translation of N-truncated proteins induced by antisense oligodeoxy nucleotides. Mol. Cell, 8, 865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vee S., Lafanechere,L., Fisher,D., Wehland,J., Job,D. and Picard,A. (2001) Evidence for a role of the α-tubulin C terminus in the regulation of cyclin B synthesis in developing oocytes. J. Cell Sci., 114, 887–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlhac M.H., Kubiak,J.Z., Clarke,H.J. and Maro,B. (1994) Microtubule and chromatin behavior follow map kinase activity but not MPF activity during meiosis in mouse oocytes. Development, 120, 1017–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlhac M.H., Kubiak,J.Z., Weber,M., Geraud,G., Colledge,W.H., Evans,M.J. and Maro,B. (1996) Mos is required for map kinase activation and is involved in microtubule organization during meiotic maturation in the mouse. Development, 122, 815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston N.J., McGuinness,O., Johnson,M.H. and Maro,B. (1995) The exit of mouse oocytes from meiotic M-phase requires an intact spindle during intracellular calcium release. J. Cell Sci., 108 (Pt 1), 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yew N., Mellini,M.L. and Van de Woude,G.F. (1992) Meiotic initiation by the mos protein in Xenopus. Nature, 355, 649–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yew N., Strobel,M. and Van de Woude,G.F. (1993) Mos and the cell cycle: the molecular basis of the transformed phenotype. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 3, 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R.P., Oskarsson,M., Paules,R.S., Schulz,N., Cleveland,D. and Van de Woude,G.F. (1991) Ability of the c-mos product to associate with and phosphorylate tubulin. Science, 251, 671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]