Abstract

The crystal structure of the C-terminal domain III of Pseudomonas aeruginosa TolA has been determined at 1.9 Å resolution. The fold is similar to that of the corresponding domain of Escherichia coli TolA, despite the limited amino acid sequence identity of the two proteins (20%). A pattern was discerned that conserves the fold of domain III within the wider TolA family and, moreover, reveals a relationship between TolA domain III and the C-terminal domain of the TonB transporter proteins. We propose that the TolA and TonB C-terminal domains have a common evolutionary origin and are related by means of domain swapping, with interesting mechanistic implications. We have also determined the overall shape of the didomain, domains II + III, of P.aeruginosa TolA by solution X-ray scattering. The molecule is monomeric—its elongated, stalk shape can accommodate the crystal structure of domain III at one end, and an elongated helical bundle within the portion corresponding to domain II. Based on these data, a model for the periplasmic domains of P.aeruginosa TolA is presented that may explain the inferred allosteric properties of members of the TolA family. The mechanisms of TolA-mediated entry of bateriophages in P.aeruginosa and E.coli are likely to be similar.

Keywords: domain swapping/Pseudomonas aeruginosa/solution X-ray scattering/TolA/TonB

Introduction

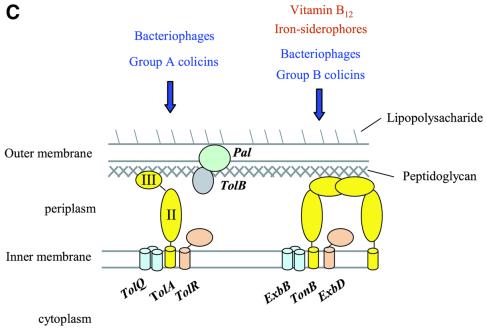

In Gram-negative bacteria, two membranes separate the cytoplasm from the outside environment. The outermost membrane contains pore-like proteins that permit access for small molecules (Nikaido, 1992). The inner membrane houses proteins that communicate across the periplasmic space to drive the energy-dependent uptake of nutrient molecules and the assembly of cellular surface structures, such as the pili that are used in conjugation. Inferences from molecular genetics suggest that the cellular envelope is maintained in part by the gene products of the tol–pal operons (Bernadac et al., 1998; Gaspar et al., 2000; Llamas et al., 2000; Sturgis, 2001). The proteins encoded by these adjacent operons include TolA, TolQ and TolR, which form an assembly in the inner membrane (Dérouiche et al., 1995; Lazzaroni et al., 1995; Dennis et al., 1996), the periplasmic TolB, and the Pal protein (peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein), which is embedded in the outer membrane (Cascales et al., 2000, 2001; Figure 1A and B).

Fig. 1. (A) Schematic representation of the periplasmic localization of the E.coli TolA protein and its putative and known partners. TolA forms an assembly with the TolQ and TolR inner membrane proteins, and interacts with the Pal protein in the outer membrane. TolA domain III has been shown to interact with the phage g3p protein that infects E.coli (Lubkowski et al., 1999), as suggested in (B). As represented in (A), the g3p protein binds to the tip of the F pilus and triggers depolymerization with the result that virus and bacteria move into contact. (C) Parallels between the TolA/Q/R and TonB/ExbB/ExbD systems, which are both conserved in Gram-negative bacteria. The Tol system is the conduit for bacteriophages and group A colicins (left). The Exb/Ton system is required for the energy-dependent uptake of vitamin B12 and iron chelates, and is the conduit for group B colicins and certain classes of bacteriophage. (D) Domain organization of E.coli and P.aeruginosa TolA proteins. Also shown are schematic representations of the three constructs studied here: domain II, domain III and domain II + III. H indicated in the boxes represents the His6 tag; M originates from the initiation codon. E.coli residue numbers relate to the Swiss-Prot file P19934. P.aeruginosa residue numbers relate to the Swiss-Prot file P50600. For example R in RALA is residue 226 and the second L in DLSL is residue 347.

The TolA proteins of the Gram-negative bacteria share a common, modular organization based on three discrete domains (Levengood et al., 1991). The N-terminal domain of TolA, known as domain I, encompasses a putative transmembrane helix, and domains II and III together extend into the periplasm (see Figure 1A). The sequence data available indicate that the TolA proteins share greatest similarity within their domains I and II; however, domain III is highly divergent, making it unclear whether this portion has the same fold among the TolA family members. From the physical location of the domains, it seems that interactions of TolA with Pal could involve domain III directly, while domains II and I communicate with TolQ and TolR.

The interaction of TolA and Pal may be driven by proton electrochemical potential, which either causes conformational changes in TolA, or affects its relationship with its TolQ and TolR partners (Germon et al., 2001). In Escherichia coli, the TolA/Q/R system has functional analogy with the TonB/ExbD/ExbB system, which is involved in nutrient import and is activated by proton motive force (Figure 1C). In keeping with this, the inner membrane proteins ExbB and ExbD are homologous to TolQ and TolR, respectively (Eick-Helmerich and Braun, 1989; Braun and Herrmann, 1993). TonB interacts with the vitamin B12 receptor and iron siderophore receptors and these associations, like the TolA–Pal interaction, are driven by proton motive force. It is not clear at present how the electrochemical gradient drives the protein–protein interactions in either of the TolA or TonB systems, or how the gradient triggers the transport processes.

Despite the protective dual-membrane layer, bacteriophages, virions and bacteriocidal toxins have evolved mechanisms to breach the double shell by targeting the Tol and Exb–Ton proteins. Indeed, the tol phenotype was originally identified by its ability to confer tolerance to class A bactericidal colicins (Hill and Holland, 1967; Nomura and Witten, 1967; Nagel de Zwaig and Luria, 1967; Sun and Webster, 1986, 1987). The TolA, TolQ, TolR and TolB proteins have each been demonstrated to play roles in the uptake of colicins and single-stranded DNA from Ff filamentous bacteriophages (Lazdunski, 1995; Click and Webster, 1997; Riechmann and Holliger, 1997; Lazdunski et al., 1998; Journet et al., 2001) (Figure 1C). In E.coli, the TolA protein binds directly to the colicins E1, A and N (Dérouiche et al., 1997; Schendel et al., 1997; Raggett et al., 1998; Gokce et al., 2000) and, along with the TolC protein, is the conduit for the uptake of colicin E1 (Griko et al., 2000). As part of the infection process, the g3p protein in the filamentous phage capsid forms a stable complex with TolA domain III in E.coli, the structure of which is known (Lubkowski et al., 1999). However, it is not clear whether TolA plays the same role during phage infection in other Gram-negative bacteria. Pseudomonas spp. have homologues of the tolAQR (Dennis et al., 1996) and pal (Lim et al., 1997) genes of E.coli, and these gene products could play similar roles. Based on structural and functional data, we will argue that the Pseudomonas TolA protein is likely to act as an entry device for filamentous bacteriophage during infection of this bacterium.

We describe here the crystal structure of domain III from the P.aeruginosa TolA protein (P.aeruginosa TolAIII) at 1.9 Å resolution. Although the amino acid sequences of domain III from P.aeruginosa and E.coli are highly divergent (only 20% identity), their structures are remarkably similar. The sequence diversity has been used here to generate a structure-based alignment of the TolA family, which has identified common elements that appear to define the fold. Surprisingly, the greatest extent of conservation is within the tight loops and at a few small side chains of the hydrophobic core. The same pattern is found in the TonB proteins, and close inspection reveals a subtle structural relationship of TolA and TonB through a domain-swapping rearrangement.

Data from solution X-ray scattering indicate that the didomain of TolA, comprising domains II and III, forms an extended, stalk-like shape. In the crystal structure of the isolated TolA domain III, the N-terminal region forms an elongated α-helix that extends from the compact core of the protein. We propose that this helical region forms a helix–helix interaction with domain II in the intact TolA to create the elongated stalk, and we postulate a fold for the didomain II + III as an asymmetrical helical bundle with a globular head. The high alanine content of domain II could permit the helices within the bundle to undergo relative axial displacement as part of an allosteric response to proton motive force.

Results

Identification and expression of TolA proteins

Different strains of P.aeruginosa are infected by specific filamentous bacteriophages. While strain O is infected by the Pf3 bacteriophage, strain K is the host for the Pf1 bacteriophage. A single-stranded DNA virus, bacteriophage Pf1 is much like the Ff bacteriophages (fd, M13, f1) of E.coli, which enter their target cells by interaction with E.coli TolA. We wanted to explore whether the P.aeruginosa TolA might play an analogous role during Pf1 cell-entry by testing for protein–protein interactions. The TolA protein from P.aeruginosa strain O has been recently identified (Dennis et al., 1996) and, using oligonucleotides from this tolA gene, we amplified the genomic DNA of strain K by PCR. The DNA sequence of the PCR fragment from strain K was almost identical to the tolA gene of strain O, except for a single substitution of R226Q that lies in the boundary between domains II and III. The strain K gene was subcloned in the expression vector pET-11c.

The purified, recombinant domain III of strain K P.aeruginosa TolA was found to bind to the minor coat protein, g3p, of its specific bacteriophage Pf1 (C.Sanz, M.Witty and R.Perham, manuscript in preparation). This observation demonstrates that the P.aeruginosa domain III studied here (Figure 1D) encompasses a functional domain of TolA, and suggests that the bacteriophage Pf1 could enter the host, P.aeruginosa strain K, by means of a mechanism similar to the entry of Ff filamentous phages into E.coli.

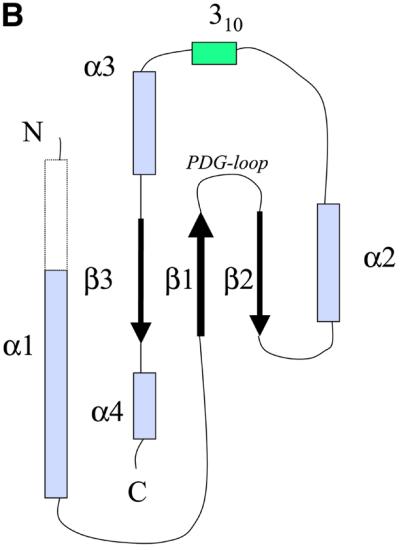

The crystal structure of domain III

Crystals were prepared from the active, recombinant P.aeruginosa TolA domain III, and the structure was solved using the anomalous scattering from selenium incorporated as seleno-methionine (the crystallographic data are summarized in Tables I and II). A Cα-trace of the protein is shown in Figure 2A, and a schematic representation of the secondary structural elements is depicted in Figure 2B. The hydrophobic core of the fold is made from residues on a surface of a highly twisted sheet that forms a scaffold for the association of three α-helices. A long α-helix at the N-terminal end projects from the body of the protein; as might be expected for such an exposed region, this extended portion is comparatively sensitive to the activity of trypsin and chymotrypsin, whereas the core of the protein is resistant (results not shown). In the crystal of the Se-methionine derivative, the helix starts at the second residue from the N-terminus and makes self-complementary contacts with neighbouring molecules related by crystallographic symmetry (Figure 3). However, in the crystal of the native TolA domain III, the electron density in this helical region only becomes well defined at residue 19, and it seems likely that this helix is meta-stable in the absence of domain II. The implications of the helical extension for the structure of domain II will be examined further below.

Table I. Diffraction data and phasinga.

| Dataset | Native + ZnCl2 | Se-Met + ZnCl2 | Se-Met + CoCl2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.54 | 0.9791 | 0.9611 | 0.9791 | 0.9611 |

| Source | Cu-Kα | ALSb | ALS | ALS | ALS |

| Symmetry: P6322 | |||||

| Cell dimensionsc | |||||

| a = b (Å) | 79.17 | 78.48 | 78.49 | 79.54 | 79.84 |

| c (Å) | 98.18 | 97.67 | 97.76 | 97.37 | 97.73 |

| Resolution (Å) | 69.0–1.90 | 20.0–1.94 | 20.0–1.92 | 20.0–1.95 | 20.0–2.50 |

| High res. bin | (1.97–1.90) | (2.01–1.94) | (2.20–1.92) | (2.01–1.95) | (2.59–2.50) |

| Total reflections | 1 218 326 | 263 045 | 253 156 | 524 794 | 293 468 |

| Unique | 14 857 | 13 441 | 14 098 | 13 395 | 6449 |

| Completeness | 99.6 (97.6) | 98.8 (94.3) | 96.7 (77.3) | 96.8 (94.7) | 95.9 (97.2) |

| <I/σ> | 39.8 (5.4) | 16.1 (2.7) | 24.0 (4.8) | 19.2 (3.1) | 23.5 (7.3) |

| Rmerge %d | 8.4 (46.3) | 8.3 (32.2) | 11.6 (39.4) | 10.7 (71.7) | 11.2 (44.4) |

| Phasing power (20–2.9 Å) | 1.2 | 1.1 | |||

| Figure of merite | 0.65 |

aThe values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution bin.

bALS: Advanced Light Source station 5.0.2.

cCell dimensions for the remote and peak Se-Met data sets were post-refined independently.

dRmerge = Σ |(Ihkl) – <I>|/Σ(Ihkl), where Ihkl is the integrated intensity of each Bragg peak.

eThe MLPHARE figure of merit for phases calculated using the data set of Se-Met + ZnCl2 in the resolution range 20–2.9 Å. Anomalous signal and isomorphous differences of Se-Met and native crystals were included in phase estimation.

Table II. Summary of crystallographic refinement.

| Crystal | Native + ZnCl2 | Se-Met + ZnCl2 |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å) | 69.0–1.90 | 19.8–1.91 |

| Unique reflections used | 13 946 | 12 777 |

| Rcrysta | 18.3 | 18.1 |

| Rfreeb | 20.2 | 23.3 |

| No. of amino acid residues | 108 | 127 |

| No. of solvent atoms | 131 | 131 |

| Heteroatoms | ||

| Zn | 2 | 2 |

| Tris | 1 | 1 |

| R.m.s. deviation from ideality | ||

| Bond distances (Å) | 0.028 | 0.024 |

| Planar groups (Å) | 0.015 | 0.017 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.67 | 2.06 |

| Chiral volume (Å3) | 0.109 | 0.128 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 22.7 | 24.1 |

| B-factor from the Wilson plot (Å2) | 21.9 | 19.0 |

aRcryst = Σ |Fobs – Fcalc|/ΣFobs, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factors. Refinement of the native structure started directly with the refined Se-methionine model, and a new set of reflections were chosen for the free group.

b5% of reflections were used to monitor the refinement.

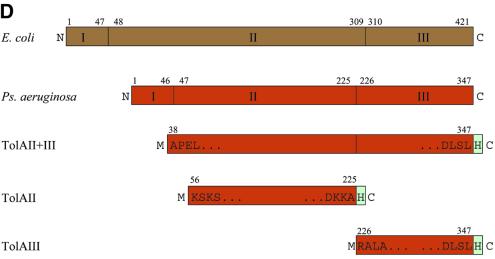

Fig. 2. (A) Two stereoscopic views of the ribbon trace of P.aeruginosa TolA domain III. (B) The convention used here to identify the secondary structural elements of P.aeruginosa TolA domain III. The N-terminal helix is longer in the crystal of the Se-methionine derivative compared with the native as demarcated by the broken lines. The helix begins at residue 2 in the Se-methionine form, but at residue 19 in the native form. The conserved PDG loop, which was used to align the TolA and TonB proteins (Figure 4), is indicated. (C) An overlay of the traces of the E.coli (blue) and P.aeruginosa (red) proteins. The E.coli protein (PDB code 1TOL) was solved as a fusion with the phage g3p protein, and the phage protein has been removed here. The perspective is the same as in the upper portion of (A). The figure was prepared using MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis, 1991) and Raster3D (Meritt and Murphy, 1994).

Fig. 3. The N-terminal helical extension of P.aeruginosa TolAIII. (A) Intermolecular contacts of the N-terminal helices of three neighbouring molecules in the crystal lattice of the Se-methionine derivative. The helices form a distinctive bundle. (B) Electron density in the vicinity of residue 20 in the N-terminal extension of the Se-methinone crystal. In the native crystal, the helical region is not as well defined and only begins at residue 19. The electron density map was calculated with minimal bias coefficients using REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 1997). The figure was generated using BOBSCRIPT (Esnouf, 1999) and Raster3D (Meritt and Murphy, 1994).

Structural relationship of the E.coli and P.aeruginosa TolA domain III proteins

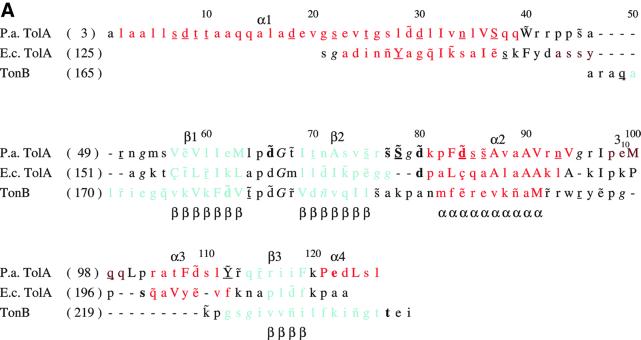

The P.aeruginosa TolAIII has remarkable structural similarity to the E.coli protein, which was solved as a fusion with the g3p protein of bacteriophage M13 (Lubkowski et al., 1999). The E.coli and P.aeruginosa molecules superimpose with a root mean square (r.m.s.) fit of 1.5 Å for the 69 equivalent Cα atoms (see Figure 2C). A close structural match was unexpected because of marginal sequence similarity between the two proteins (Figure 4A), which was only 20% after structure-based alignment.

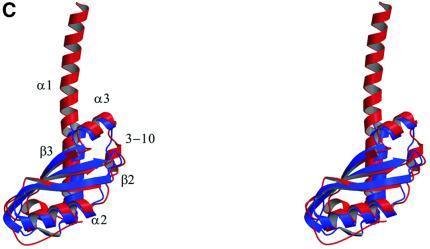

Fig. 4. Structural relationship of the TolA and TonB proteins. (A) A structure-based sequence alignment of TolA domain III from E.coli and P.aeruginosa, and the TonB protein. Residues in the loop between β1 and β2 are highly conserved amongst the available TolA and TonB homologues (not shown). The consensus secondary structure is shown below the alignment: α for α-helical positions; 3 for 310-helical positions; β for β-sheet positions. The formatting convention of JOY is as follows: red, α helices; blue, β strands; maroon, 310 helices; upper-case letters, solvent inaccessible; lower-case letters, solvent accessible; bold type, hydrogen bonds to main chain amides; underlining, hydrogen bonds to main chain carbonyls; tilde (∼), hydrogen bonds to other side chain/heteroatoms; italic, positive main chain torsion angles φ; cedilla (ç), disulfide-bonded cystine residues. (B) The TonB homodimer structure (PDB entry 1IHR). The individual protomers have been coloured purple and blue. The secondary structural elements have been labelled to correspond to the convention used for P.aeruginosa TolAIII (see Figure 22). (C) An overlay of the ribbon traces of a TonB pseudo- protomer (blue) with the P.aeruginosa TolA domain III protein (red). The TonB pseudo-promoter was generated by consolidating the elements of the dimer that are common with one TolA molecule and trimming back strands corresponding to β1 and β3. The perspective is similar to that used in the top portion of Figure 2A. The PDG loop is in the upper right.

A sequence alignment guided by the crystal structures is shown in Figure 4A, with annotated structural features. Few of the residues in the hydrophobic cores of the two proteins are identical. The E.coli protein contains a disulfide bridge between the strand and the helix, but this disulfide is not present in the P.aeruginosa protein, which instead has a clustered group of small non-polar side chains in the corresponding position.

The central core of TolA domain III contains a sizeable cavity with an estimated volume of 80 Å3. Generally, cavities of this size are expected to be destabilizing in protein structures (Hubbard et al., 1994). The elongated cavity in the P.aeruginosa TolAIII protein is ringed by three, inter-digitated valine residues at one end, and by four isoleucine side chains, similarly intermeshed, at the opposite end. In the core of the E.coli protein, there are fewer β-branched residues (three isoleucines as compared with the four isoleucines and three valines in the case of the Pseudomonas protein), and there is no corresponding internal cavity. This appears to be due to compensatory movements of the neighbouring secondary structural elements. The restricted rotational movement of the β-branched side chains and their close intermeshing in the Pseudomonas protein might prevent the fold from collapsing around this small interior pocket.

What appears to be common in the P.aeruginosa and E.coli structures is not the detailed interaction of side chains in the core, but the binary pattern of polar and non-polar residues in the amphipathic helices and strands. Also, details of the loop conformations appear to be maintained. In both structures, glycine residues occur in loops between strands β1 and β2, and again between β2 and helix α2. These glycines support a positive backbone φ angle (shown in italics in Figure 4A) that permits the juncture of the secondary structural elements. Supporting the turn between β1 and β2 is a conserved aspartate side chain that, in the P.aeruginosa protein, forms a hydrogen bond to the main chain amide. The Pro-Asp-Gly sequence in the tight turn between β1 and β2 occurs in other TolA homologues identified in the sequence database, and is one of very few conserved primary sequence elements among these proteins. The binary pattern of polar and non-polar residues is also maintained, although the detailed composition varies. These observations suggest that the domain fold is likely to be maintained in the wider TolA family, and that structural conservation originates from the combination of loop geometry and the binary polar/non-polar pattern.

Structural relationship of the TolA and TonB proteins

The structure-based sequence pattern noted above encouraged us to search the structural database for divergent homologues. We used a procedure that evaluates amino acids weighted in accordance with structural context (Shi et al., 2001). While the procedure was designed to identify structures that a given sequence is likely to adopt, it can also match structures with analogous internal contacts even though they may be distinct topologically. We were astonished to find a statistically significant match (Z = 6.5) between domain III of P.aeruginosa TolA and the C-terminal domain of E.coli TonB protein (hereafter, ‘TonB/CTD’), which had been proposed earlier to share functional similarity with TolA (Braun and Herrmann, 1993). However, no structural or sequence similarity had been established earlier (Chang et al., 2001).

Both TolA domain III and TonB/CTD have the secondary structure pattern β-β-α-β; however, they differ topologically, and their structural relationship is not at first apparent. TonB/CTD is a homodimer in which the two subunits are extensively intertwined, so that the β-sheets are made from strands of both subunits, and the central helix packs against strands that originate mostly from the partner subunit (Figure 4B). Our structure-based alignment, derived on the basis of the local environment, and thus independent of topology, revealed a match of the highly conserved loop elements, in particular the Pro-Asp-Gly motif at the first tight β-turn, and a correspondence of the secondary structural elements. We overlaid the two proteins on the conserved loops and found that the entire β-hairpins superimpose closely (Figure 4C). Whereas in TolAIII the helix following the second strand (α2 in Figure 2B) returns to become buried against the sheet, in TonB/CTD the corresponding helix extends from the end of the second strand to bury against the equivalent, symmetry-related sheet. The strand following the helix (β3) completes the sheet in TolAIII, but in TonB/CTD it completes the sheet of the neighbouring subunit. Thus, the principal secondary structural elements of TolAIII and TonB/CTD match, and they pack in nearly identical ways, with the difference that in the TonB/CTD dimer, the elements pack against symmetry-related partners. It is possible to inter-convert the TolAIII and TonB/CTD structures by modestly changing the trajectory of the loop connecting the second strand with the helix (β2 and α2) of the other subunit. The secondary structural elements of TonB shown in Figure 4B are labelled according to the corresponding elements of the TolA domain III shown in Figure 2.

The structural overlay in Figure 4C was prepared by isolating the equivalent portions of TolAIII and TonB/CTD. The r.m.s. deviation for the overlay of 40 common Cα atoms between P.aeruginosa TolAIII and the E.coli TonB/CTD rearranged protomer is 1.9 Å, and the sequence identity is 18% for the structure-based alignment of the two proteins, comparable to the 20% identity for the match of P.aeruginosa and E.coli TolAIII domains. Based on the structural congruence, the TonB and TolA proteins seem likely to share a common, ancestral fold. Recent studies have shown that intertwined dimers can be generated from ancestral protomers through the displacing exchange of secondary structural elements (Bennett et al., 1995).

The N-terminal helical segment of TolA domain III

The N-terminal helical extension mentioned earlier passes close to a crystallographic axis and as a result forms a self-complementary interaction (Figure 3). In the Se-methionine crystal form, the helix is apparent from residue 2, but in the native crystal form, the helix is not as well formed, as the density only becomes well defined at residue 19. This helix is thus likely to be meta-stable. The self-complementary interactions seen for the N-terminal domain closely resemble the grooves-into-ridges association observed in packed α-helices. Our solution data from solution X-ray scattering (discussed below) indicate that both domain II and domains II + III of P.aeruginosa TolA are monomeric, and it seems unlikely that the crystal contact persists in solution. However, the self-association of the N-terminal segment might be indicative of a propensity to form a buried intramolecular surface. This is precisely the type of interaction required to account for the molecular shape described in the next section.

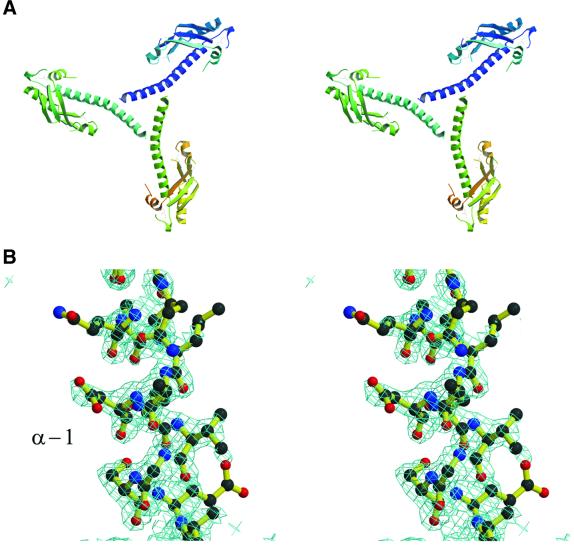

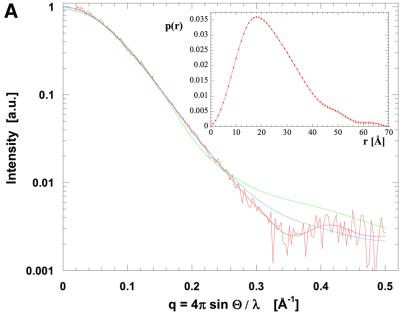

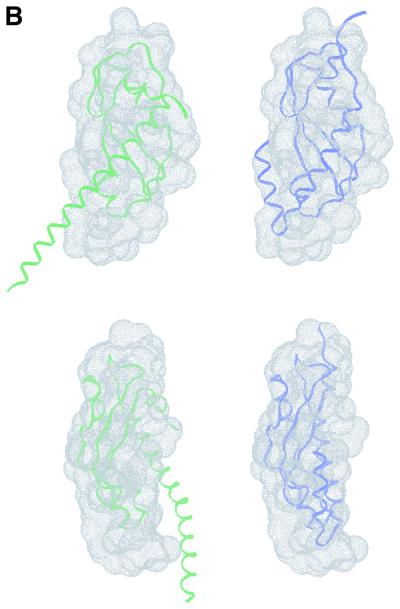

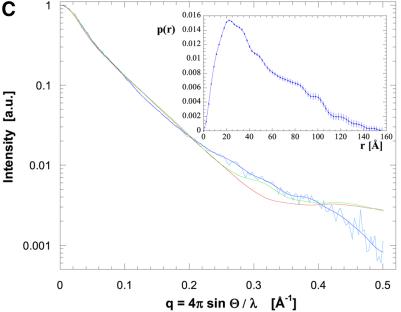

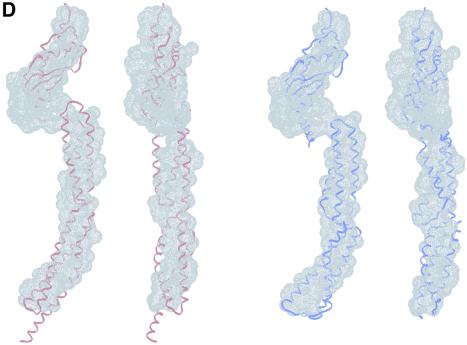

A molecular shape for domains II + III

Solution X-ray scattering data were collected from recombinant domains II and III of P.aeruginosa TolA in isolation, and from a larger polypeptide encompassing domains II + III (Figure 1D). The radially averaged scattering profiles are presented in Figure 5. These data were analysed to extract structural parameters such as radius of gyration, maximal molecular dimension and volume (summarized in Table III). These values, as well as the extrapolated forward scattering intensity, indicate that domains II, III and II + III are monomeric. Molecular shapes were reconstructed ab initio from the scattering profiles, and these are also shown in Figure 5 (including the fit to the experimental data). Although most parts of the shape of domain III match well with the crystal structure, in solution there exists a small, noticeable expansion. This extension to the core shape of domain III is likely due to disorder of the N-terminal helical extension, which may not retain its structure in solution, or may even change the orientation and conformation of the N-terminal helix. Figure 5A and B shows the effects of different helical orientations on the scattering profile. Whereas the atomic model as shown in Figure 2A fits the low angle data only reasonably well (resulting in a goodness-of-fit value of χ = 3.1), reorienting and changing the direction of the N-terminal helix improves the fit considerably (χ = 1.8). This suggests that the N-terminal helix does not show a unique conformation in solution for the isolated domain III.

Fig. 5. Molecular shape of the TolA periplasmic domains. (A) Solution X-ray scattering profile for P.aeruginosa TolAII domain. The smooth red curve through the experimental scattering data represents the profile from the restored shape shown in (B). Scattering profiles have been calculated based on the crystallographic structure of TolAIII (green curve, see Figure 2A) and a TolAIII model with changed N-terminal helical conformation (blue curve). (B) Shape of TolAIII as deduced from the experimental scattering profile alone with superimposed ribbons for the models introduced in (A). The top and bottom sets are different views of the two models. (C) Scattering profile and (D) shape reconstruction for the protein comprising both domains II and III. Two ribbon models have been superimposed: spectrin repeat of actinin (red) and two repeats of the alanine-rich helical bundles (blue) from the enzyme IIAlactose have been built into the molecular envelope. Two views are shown for each model. Their corresponding simulated scattering profiles have been given in (C).

Table III. Structural parameters from solution X-ray scattering analysis.

| Sample | Rg (Å) | Dmax (Å) | V (Å3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TolAII | 40.7 | 134.2 | 51 000a |

| TolAIII | 19.1 | 70.0 | 30 000 |

| TolAII + III | 42.0 | 156.0 | 69 000 |

aDue to the partially unfolded state of TolA domain II, the error for its volume is 25%. Errors in the experimental values for radius of gyration (Rg), maximal molecular dimension (Dmax) and hydrated volume (V) are of the order of 1, 4 and 5%, respectively.

The shape for domain II is more complex than that for didomain II + III, suggesting that the protein might be poorly folded in isolation (data not shown). The shape for the didomain II + III is elongated (Figure 5 and Table III). This is consistent with domain II of P.aeruginosa TolA having an extended helical structure, as proposed by Levengood et al. (1991) for the E.coli protein. TolA domain II from P.aeruginosa, E.coli and many other Gram-negative bacteria generates consistently high scores for the coiled-coil motif (Lupas, 1997; Wolf et al., 1997). Further, a circular dichroism study of E.coli TolA showed the domain maintains a predominantly α-helical character (Levengood et al., 1991). Our circular dichroism spectrum of the isolated P.aeruginosa TolA domain II also indicates that this protein is primarily α-helical (results not shown).

Because one end of TolA lies near the membrane and the other end protrudes into the periplasm, domain II is likely to contain an odd number of helices. It thus seems likely that domain II will contain three helices in a bundle, in which two are parallel and the third anti-parallel. This type of fold can be found in the spectrin motif, and also in the alanine-rich helical bundle of the enzyme IIAlactose (Sliz et al., 1997). We prepared models of TolAII + III using the molecular envelope for the linked domains II + III, the crystal structure of the spectrin domain of α-actinin, two repeats of the alanine-rich helical bundle of the enzyme IIAlactose and the crystal structure of P.aeruginosa TolAIII. The spectrin fold has an elongated central α-helix, with bundles of three helices as ends. To produce the overall length delineated by the molecular envelope, two alanine-rich, three-helical bundles were built.

The two models give satisfactory fits, although the scattering profile simulation yielded χ-values of only 5.0 for the spectrin-like helical bundle, and 4.5 for the alanine-rich assembly (see Figure 5C and D). Again, the arrangement of helices in domain II will affect the scattering profile significantly without improving the fit, as simulations using several different models demonstrated. It is therefore plausible that no unique, rigid conformation will be fully consistent with the experimental scattering profile. Both models would not only allow for conformational flexibility, but would also satisfy the requirements for forming coiled-coil interactions, for one end of the peptides to lie near the cell inner membrane, and for the other end to protrude into the periplasm together with domain III.

Discussion

The crystal structure of domain III of P.aeruginosa TolA has been determined and compared with the structure of the corresponding E.coli protein. The hydrophobic core in the TolA proteins from these and other bacteria are maintained in entirely different ways, but a sequence pattern can be discerned for the core, and for certain loops that conserve the fold within the TolA family. Searches guided in part by these features revealed an unexpected structural relationship between the TolA and TonB proteins. It appears that the fold of the dimeric TonB is related to TolAIII through domain swapping.

Sedimentation experiments suggest that the periplasmic domain of TonB is monomeric in solution (Moeck and Letellier, 2001). Whether the TonB dimer, as observed in the crystal structure, and the monomer, as inferred from solution studies, represent two states of a potential monomer/dimer equilibrium is not clear. If the equilibrium does occur, the TonB monomer could still assume the TolA fold, but portions of the elongated strands, β1 and β3, would be left as an exposed β-ribbon, and this would need to undergo extensive conformational changes in the isolated subunit; however, this seems to be unlikely. The TolA domain III could undergo a domain-swapped association to form a dimeric structure similar to TonB, but the solution scattering data presented here suggest that this is also not the case. Regardless of the oligomerization state, the observed structural relationship between TonB and TolA described here establishes a clear evolutionary link between the two proteins, hitherto inferred only in terms of their loose functional parallels.

One unresolved question regarding TonB’s role in active transport is how the protein interacts with the TonB box of the outer membrane target receptors, such as FepA and the vitamin B12 receptor. The TonB box is a short peptide with no apparent structural preference, but it has a clear and important role in mediating the uptake of substrate for transport (Cadieux et al., 2000; Moeck and Letellier, 2001; Ferguson et al., 2002). In the E.coli ferric receptor, the five-residue TonB box becomes disordered with the uptake of ligand (Ferguson et al., 2002). The structural relationship of TolA and TonB might provide an indirect clue as to how the recognition occurs. We note that in the E.coli g3p–TolAIII complex (Lubkowski et al., 1999), g3p is accommodated in a shallow surface concavity of TolA, and a strand of the g3p protein engages with the peripheral strand of the β-sheet within TolA to make a pseudo-continuous sheet. In an analogous fashion, the corresponding terminal strand in the TonB dimer could perhaps act as a surface for matching the TonB-box peptide via extended sheet formation.

In addition to their relatedness through the domain III fold, the TonB and TolA proteins may also share a common molecular shape and domain architecture. TonB has a proline-rich segment preceding the TolA-like C-terminal domain, which could form a type-II left-handed helix. Similarly, domain II of TolA is elongated, and forms an α-helical region. In both cases, the unusual inter-domain regions probably communicate signals from membrane-embedded neighbours to the TolA-like domain through allosteric structural changes.

In the crystal, the N-terminal end of P.aeruginosa TolAIII protrudes from the compact domain and makes a self-complementary interaction with a neighbouring molecule. This interaction most likely does not occur in solution, as data from solution X-ray scattering show that the protein is monomeric. We propose that this helical region forms an intramolecular contact with domain II. The geometrical requirements of the intact molecule dictate that the termini must be at opposite ends of domain II, so that domain I is in the membrane and domain III is in the periplasmic space. This requires the polypeptide chain within domain II to cross the periplasmic space three times if it were entirely coiled coil. Such packing would generate a distinctive geometry in which two helices of the coiled coil are parallel, yet the third is anti-parallel to both. An earlier study has modelled E.coli TolAII as a three-member coiled coil (Dérouiche et al., 1999). The solution shape of P.aeruginosa TolAII + III is consistent with an elongated shape that can accommodate a bundle of three helices. We propose that the structure may be similar to that of the spectrin motif or the alanine-rich three-helix bundle found in the crystal structure of a lactose transporter phosphotransfer enzyme (enzyme IIAlactose; Sliz et al., 1997).

The putative coiled-coil region in domain II is rich in alanine, and this feature is a hallmark of all the TolA homologues identified in the current sequence database (data not shown). In E.coli TolAII, alanine accounts for 45% of the residues, generally presented in stretches of three or four consecutive positions. In the enzyme IIAlactose (Sliz et al., 1997), which has a three-helix bundle, the alanine-rich segments allow the interacting residues at the a and d positions of the heptadic repeats to occupy different heights along the superhelical axis. The crystal structure of tropomyosin shows that alanine stretches are associated with axial translation of the coiled-coil helices (Brown et al., 2001). The helices form ‘knobs-into-holes’ interactions (Crick, 1953), but the small knobs fit loosely into the corresponding holes, permitting relative translation, and an instantaneous change in the super-helical path of the coiled coil. The mechanism seems likely to play a role in the structural transitions associated with muscle contraction. A similar allosteric effect in conventional coiled coils has been proposed (Calladine et al., 2001). The spectrin fold itself has also been noted to have potential for structural plasticity that could originate allosteric changes (Grum et al., 1998). In light of these observations, it seems likely that the alanine-enriched domain II of the TolA proteins could play a role in communicating signals through analogous allosteric effects. The structural details of this domain should provide insight into the potential of this region for structural transitions.

The origin of the signal between TolA and Pal, or TonB and its partners, is in the proton electrochemical potential. However, it is not clear at present how the proton motive force drives the protein–protein interactions, and how this might trigger the transport mechanisms. One common feature in the transmembrane domains of TolA and TonB that could play a role in the transport process is a conserved S-XXX-H-XXXXXX-L-XXX-S motif (Germon et al., 1998; Karlsson et al., 1993). The con served residues are likely to lie along a co-axial stripe along the transmembrane helix to form an intermolecular packing surface, and perhaps it is this packing that is affected by the proton motive force, which may in turn drive axial displacements in the inter-domain regions as part of the allosteric mechanism.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression and purification of TolA proteins

The DNA sequence encoding domains II + III of P.aeruginosa TolA was amplified by PCR from the genome of P.aeruginosa strain K (ATCC 25102) using primers with the sequence 5′-ATGCTGTTCGTCAG CTGGCATATGCTCCGGAGCTTCCTCCC-3 and 5′-TTTTTTGGA TCCTTAGTGATGGTGATGATGGTGCAGACTCAAATCCTCCGG TTT-3′. The PCR product was digested with NdeI and BamHI and then cloned in pET-11c to give the expression vector pET-TolAII + III.

Expression vectors for the separate domains II and III were prepared from the plasmid pET-TolAII + III using the primers 5′-GGC TGCCGAGGACAAGCATATGCGGGCATTGGCCGAGTTGC-3′ and 5′-TTTTTTGGATCCTTAGTGATGGTGATGATGGTGCAGACTCA AATCCTCCGGTTT-3′ for pET-tolA III and 5′-CGCTCTACCAT ATGAAGTCGAAGAGCCAGGCGACG-3′ and TTTTTTGGATCCT TAGTGATGGTGATGATGGTGCTGCGCCTTCTTGTCCTC for pET- tolA II. These constructs express the proteins with a C-terminal His6 tag (see Figure 1D).

For protein production, the expression vectors were used to transform E.coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells. Bacterial cultures were grown at 37°C to mid-log phase, and protein expression was induced with isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 1 mM. After 3 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed in buffer A (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl pH 8.0). All TolA domains were initially purified using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen). The crude lysate was applied to the column in buffer A and eluted with buffer A containing 250 mM imidazole. TolA domain III was further purified by application to a Q-Sepharose column (Pharmacia 17-0709-01) and elution in 10 mM Tris–HCl, 0.01% octyl-glucoside, 125 mM NaCl pH 8.0. TolAII and TolAII + III proteins were further purified using a Resource S column (Pharmacia) and a gradient of 0–1 M NaCl in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.0. The purity of proteins was evaluated at each stage by means of SDS–PAGE.

Proteins were desalted and concentrated to 10 mg/ml using a Millipore 5 KDa MWCO ultrafiltration device. The identity and integrity of purified proteins was confirmed by MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted, laser-desorption time-of-flight) mass spectrometry and N-terminal sequence analysis.

Selenomethionine-TolAIII was also expressed in E.coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells, using the metabolic inhibition method of van Duyne et al. (1993). The protein was purified as described for the native protein. Analysis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry indicated that three of the four Se-methionine residues were in the reduced state while a fourth was present in the reduced, singly oxidized (selenoxide) and doubly oxidized (selenone) forms. The observed mass of the reduced form was 14 596.2 Da (expected mass of 14 596.8 Da); for the single selenoxide, the observed mass was 14 616.8 Da (expected 14 612.8 Da) and for the single selenone form, the mass was 14 633.9 Da (expected 14 628.8 Da).

Crystallization and data collection

The His6 tag at the C-terminus of the protein was not removed for crystallizations. The crystals were prepared from hanging droplets by vapour diffusion and grew under a variety of conditions, and crystals were grown reproducibly when transition metals (Zn, Ni, Co, Cu) were included at concentrations ranging from 100 µM to 1 mM. The best crystals typically grew from droplets containing a 2:1 mixture of protein, at 10 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.05% w/v octyl-glucoside, to the reservoir containing 5% w/v PEG 6000, 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0 and 1 mM ZnSO4. The crystals grew after 3 days as single, hexagonal plates with typical dimensions of 300 × 300 × 50 µm3. The space group is P6322.

Isomorphous crystals of the selenomethionine version of the protein were prepared under conditions similar to those used for generating the native crystals. To create a reducing environment for the selenomethionine crystallization trials, 40 µl of 1 M FeSO4 was suspended between the droplet and the buffer reservoir in a concave bridge.

Data sets were collected from native crystals grown in the presence of zinc at 100 K using an R-axis II detector with monochromatic Cu radiation. Crystals were cryoprotected in crystallization solution diluted with PEG400 at 32% v/v. Data were processed with DENZO and merged with SCALEPACK (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997).

Anomalous dispersion data were collected at 100 K from cryoprotected Se-methionine crystals at station 5.0.2 of the Advanced Light Source (ALS) at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. One data set was collected from crystals grown in the presence of 0.1 mM ZnSO4. In agreement with the MALDI mass spectrometry results described above, the fluorescence spectra indicated that the Se sites were predominantly in the reduced state. Data were collected in inverse-beam mode at the peak of the Se anomalous signal and at a remote, high-energy wavelength. Peak and remote data were also collected from a second crystal grown in the presence of 1 mM CoCl2. These data were useful for confirming the position of the Se sites. The MAD datasets were processed and scaled with HKL2000. The data are summarized in Table I.

Phasing and refinement

Three internally consistent Se sites were found with the Patterson search routine in SHELX (Sheldrick, 1997) using modified anomalous difference amplitudes [prepared with the program REVISE (Collaborative Computational Project No. 4, 1994)]. The positions and occupancies were refined and the starting phases calculated using MLPHARE (Collaborative Computational Project No. 4, 1994). The map, calculated using the three principal sites, was improved and the resolution extended by density modification using DM (Cowtan, 1994). This map was readily interpretable. One molecule of TolA domain III occupies the asymmetric unit, with a Matthews coefficient of 2.97 Å3/Da, corresponding to a solvent content of 58.3%. The chain was traced using QUANTA and the model was refined against the Se-methionine peak dataset using REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997). The N-terminal methionine, which represents the fourth Se-methionine of the asymmetric unit, could not be visualized in the refined maps. The refined Se-methionine model was used as the starting point for the refinement of the native crystal form. The refined stereochemistry was evaluated using PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993). For the refined Se-methionine crystal form, 98.2% of the residues were in the core region of the Ramachandran plot, and the remaining 1.8% in the allowed region; for the crystal of the native proteins these values were 97.8% and 2.2%, respectively. The stereochemistry was also evaluated using MolProbity to guide choice of side chain rotamer (http://kinemage.biochem.duke.edu/molprobity). A summary of the refinement details is presented in Table II.

The electron density for the N-terminal helical region in the Se-methionine crystal form is notably less well defined than for the core of the protein, and the refined temperature factors in this portion of the structure are greater. Representative density for this region is shown in Figure 3B. To confirm that the poor density was not due to the possible effect of averaging distinct conformations by enforcing imperfect crystallographic symmetry, maps were calculated with the refined structure in lower symmetry space groups (P63 and trigonal P322), but the density was not improved.

The growth of the TolAIII crystals was strikingly induced by transition metals. In the crystals of both the native and Se-methionine proteins, metal ions, presumably Zn2+, were found to be tetrahedrally coordinated by water molecules and the Nε atoms from histidine imidazole groups of the His6 tag. The identity of these metals was corroborated by anomalous Fourier syntheses. The metals are shared by symmetry-related molecules, and this arrangement must reinforce the lattice.

X-ray scattering experiments and data analysis

Solution X-ray scattering data were collected with the low-angle scattering camera at station 2.1 (Towns-Andrews et al., 1989) at the SRS Daresbury Laboratory, UK, using a 2D multiwire proportional chamber with delay line readout (Lewis, 1994). Scattering data from protein as well as buffer samples were collected at two different sample-detector distances (1.5 m and 4.5 m) to cover the range of momentum transfer 0.02 Å–1 < q < 0.45 Å–1 (q = 4π sin Θ/λ; 2Θ is the scattering angle and λ = 1.54 Å is the wavelength). The q range was calibrated using an oriented specimen of wet rat tail collagen (based on a diffraction spacing of 670 Å).

For scattering data collection, TolA domains II, III and II + III were prepared in a buffer of 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0. Samples were analysed at 4°C with protein concentrations in the range 0.5–9 mg/ml. Data reduction included radial integration of the 2D images, normalization of subsequent 1D data to the intensity of the transmitted X-ray beam, correction for positional non-linearity of the detector and subtraction of background scattering from the buffer. Molecular masses of the proteins were checked by comparison with the forward scattering from a bovine serum albumin solution (66 kDa) as standard.

Distance distribution functions p(r) and the radii of gyration Rg were evaluated with the indirect Fourier transform program GNOM (Semenyuk and Svergun, 1991), which also allows a reliable estimate of the maximal particle dimension Dmax [i.e. the value of r at which p(r) drops to zero]. The calculation of molecular volumes was based upon Porod’s invariant (Porod, 1951), bearing in mind the limited experimental scattering interval (Feigin and Svergun, 1987). Particle shapes were restored from the experimental scattering profiles using the ab initio procedure based on the simulated annealing algorithm to a set of dummy spheres representing the amino acid chain of the protein (Svergun et al., 2001). Superimposition of low- and high-resolution protein models was performed with the program SUPCOMB (Kozin and Svergun, 2001).

Information from atomic models was exploited to define the nature of the observed scattering features in structural terms. Scattering curves were evaluated from these models using the program CRYSOL (Svergun et al., 1995). This method takes the solvent effect into account by surrounding the protein with a hydration shell of thickness 3 Å and of uniform density different from that of bulk solvent.

Circular dichroism analyses

Circular dichroism spectra of TolA domain II in 20 mM Na phosphate pH 7.0 were collected using an Aviv CD 215 spectrometer.

Sequence and structure analyses

Coiled-coils were analysed with COILS (Lupas, 1997) and MultiCoil (Wolf et al. 1997). A FUGUE (http://www-cryst.bioc.cam.ac.uk/fugue/; Shi et al., 2001) search against a database of known structures was carried out using the P.aeruginosa TolA domain III sequence as a query. The structure-based sequence alignments and superpositions were generated using STAMP (Russell and Barton, 1992) and COMPARER (Sali and Blundell, 1990), and formatted with JOY (Mizuguchi et al., 1998). Structure predictions for P.aeruginosa TolAII with the sequence-threading program SAUSAGE (Huber et al., 1999) provided coiled-coil structures as top-scoring candidates.

Protein Databank codes

Coordinates for the Pseudomonas TolAIII crystal structures (Se-methionine and native) and diffraction amplitudes have been deposited with the Protein Databank (code 1LR0).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The staff of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory kindly provided access to facilities and in particular we thank Keith Henderson, Sue Bailey, Gerry McDermitt and Thomas Ernest for their generous help and advice. We gratefully acknowledge the staff at the SRS Daresbury Laboratory, especially James Nicholson for his assistance during data collection. We thank Jane Richardson for introducing us to the program MolProbity. This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust and The Leverhulme Trust. A.S. is supported by a Herchel Smith Fellowship.

References

- Bennett M.J., Schlunegger,M.P. and Eisenberg,D. (1995) 3D domain swapping: a mechanism for oligomer assembly. Protein Sci., 4, 2455–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernadac A., Gavioli,M., Lazzaroni,J.C., Raina,S. and Lloubes,R. (1998) Escherichia coli tol–pal mutants form outer membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol., 180, 4872–4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulin C., Kempf,R., Koch,M.H.J. and McLaughlin,S.M. (1986) Data appraisal, evaluation and display for synchrotron radiation experiments: hardware and software. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A, 249, 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V. and Herrmann,C. (1993) Evolutionary relationship of uptake systems for biopolymers in Escherichia coli: cross-complementation between TonB-ExbB-ExbD and the TolA-TolQ-TolR proteins. Mol. Microbiol., 8, 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.H., Kim,K.H., Jun,G., Greenfield,N.J., Dominguez,R., Volkmann,N., Hitchcock-DeGregori,S.E. and Cohen,C. (2001) Deciphering the design of the tropomysin molecule. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 8496–8501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadieux N., Bradbeer,C. and Kadner,R.J. (2000) Seequence changes in the ton box region of BtuB affect its transport activities and interaction with TonB protein. J. Bacteriol., 182, 5954–5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calladine C.R., Sharff,A. and Luisi,B. (2001) How to untwist an α-helix: structural principles of an α-helical barrel. J. Mol. Biol., 305, 603–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E., Gavioli,M., Sturgis,J.N. and Lloubes,R. (2000) Proton motive force drives the interaction of the inner membrane TolA and outer membrane Pal proteins in Escherichia coli.Mol. Microbiol., 38, 904–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E., Lloubes,R. and Sturgis,J.N. (2001) The TolQ-TolR proteins energize TolA and share homologies with the flagellar motor proteins MotA-MotB. Mol. Microbiol., 42, 795–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Mooser,A., Plückthun,A. and Wlodawer,A. (2001) Crystal structure of the dimeric C-terminal domain of TonB reveals a novel fold. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 27535–27540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Click E.M. and Webster,R.E. (1997) Filamentous phage infection: required interactions with the TolA protein. J. Bacteriol., 179, 6464–6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project No. 4. (1994) The CCP4 suite: Programs for X-ray crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D, 50, 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K. (1994) DM: an automated procedure for phase improvement by density modifications. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography, No. 31, 34–38.

- Crick F.H.C. (1953) The packing of alpha-helices: simple coiled-coils. Acta Crystallogr., 6, 689–697. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis J.J., Lafontaine,E.R. and Sokol,P.A. (1996) Identification and characterization of the tolQRA genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol., 178, 7059–7068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dérouiche R., Bénédetti,H., Lazzaroni,J.C., Lazdunski,C. and Lloubes,R. (1995) Protein complex within Escherichia coli inner membrane. TolA N-terminal domain interacts with TolQ and TolR proteins. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 11078–11084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dérouiche R., Zeder-Lutz,G., Bénédetti,H., Gavioli,M., Rigal,A., Lazdunski,C. and Lloubes,R. (1997) Binding of colicins A and E1 to purified TolA domains. Microbiology, 143, 3185–3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dérouiche R., Lloubes,R., Sasso,S., Bouteille,H., Oughideni,R. Lazdunksi,C. and Loret,E. (1999) Circular dichroism and molecular modelling of the E.coli TolA periplasmic domains. Biospectroscopy, 5, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eick-Helmerich K. and Braun,V. (1989) Import of biopolymers into Escherichia coli: nucleotide sequences of the exbB and exbD genes are homologous to those of the tolQ and tolR genes, respectively. J. Bacteriol., 171, 5117–5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnouf R.M. (1999) Further additions to MolScript version 1.4, including reading and contouring of electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D, 55, 938–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigin L.A. and Svergun,D.I. (1987) Structure Analysis by Small-Angle X-ray and Neutron Scattering. Plenum Press, New York.

- Ferguson A.D., Chakraborty,R., Smith,B.S., Esser,L., van der Helm,D. and Deisenhofer,J. (2002) Structural basis of gating by the outer membrane transporter FecA. Science, 295, 1715–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar J.A., Thomas,J.A., Marolda,C.L. and Valvano,M.A. (2000) Surface expression of O-specific lipopolysaccharide in Escherichia coli requires the function of the TolA protein. Mol. Microbiol., 38, 262–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germon P., Clavel,T., Vianney,A., Portalier,R. and Lazzaroni,J.C. (1998) Mutational analysis of the Escherichia coli K-12 TolA N-terminal region and characterization of its TolQ-interacting domain by genetic suppression. J. Bacteriol., 180, 6433–6439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germon P., Ray,M.-C., Vianney,A. and Lazzaroni,J.C. (2001) Energy-dependent conformational change in the TolA protein of Escherichia coli involves its N-terminal domain, TolQ and TolR. J. Bacteriol., 183, 4110–4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokce I., Raggett,E.M., Hong,Q., Virden,R., Cooper,A. and Lakey,J.H. (2000) The TolA-recognition site of colicin N. ITC, SPR and stopped-flow fluorescence define a crucial 27-residue segment. J. Mol. Biol., 304, 621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griko Y.V., Zakharov,S.D. and Cramer,W.A. (2000) Structural stability and domain organization of colicin E1. J. Mol. Biol., 302, 941–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grum V.L., Li,D., MacDonald,R.I. and Mondragon,A. (1999) Structure of two repeats of spectrin suggests models of flexibility. Cell, 98, 523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. and Holland,J.B. (1967) Genetic basis of colicin E susceptibility in Escherichia coli. I. Isolation and properties of refractory mutants and the preliminary mapping of their mutations. J. Bacteriol., 94, 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard S., Gross,K.H. and Argos,P. (1994) Intramolecular cavities in globular proteins. Protein Eng., 7, 613–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber T., Russell,A.J., Ayers,D. and Torda,A.E. (1999) SAUSAGE: protein threading with flexible force fields. Bioinformatics, 15, 1064–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journet L. Bouveret,E., Rigal,A., Lloubes,R., Lazdunski,C. and Bénédetti,H. (2001) Import of colicins across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli involves multiple protein interactions in the periplasm. Mol. Microbiol., 42, 331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M., Hannavy,K. and Higgins,C.F. (1993) A sequence-specific function for the N-terminal signal-like sequence of the TonB protein. Mol. Microbiol., 8, 379–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozin M.B. and Svergun,D.I. (2001) Automated matching of high- and low-resolution structural models. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 34, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P.J. (1991) MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 24, 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., MacArthur,M.W., Moss,D.S. and Thorton,J.M. (1993) PROCHECK—a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lazdunski C. (1995) Colicin import and pore formation: a system for studying protein transport across membranes? Mol. Microbiol., 16, 1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazdunski C., Bouveret,E., Rigal,A., Journet,L., Lloubes,R. and Bénédetti,H. (1998) Colicin import into Escherichia coli cells. J. Bacteriol., 180, 4993–5002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaroni J.C., Vianney,A., Popot,J.L., Bénédetti,H., Samatey,F., Lazdunski,C., Portalier,R.C. and Géli,V. (1995) Transmembrane α-helix interactions are required for the functional assembly of the Escherichia coli Tol complex. J. Mol. Biol., 246, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levengood S.K., Beyer,W.F.,Jr and Webster,R.E. (1991) TolA: A membrane protein involved in colicin uptake contains an extended helical region. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 5939–5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. (1994) Multiwire gas proportional counters: Decrepit antiques or classic performers? J. Synchrotron Rad., 1, 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A. Jr, De Vos,D., Brauns,M., Mossialos,D., Gaballa,A., Qing,D. and Cornelis,P. (1997) Molecular and immunological characterization of OprL, the 18kDa outer-membrane peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (PAL) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology, 143, 1709–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas M.A., Ramos,J.L. and Rodriguez-Herva,J.J. (2000) Mutations in each of the tol genes of Pseudomonas putida reveal that they are critical for maintenance of outer membrane stability. J. Bacteriol., 182, 4764–4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubkowski J., Hennecke,F., Plückthun,A. and Wlodawer,A. (1999) Filamentous phage infection: crystal structure of g3p in complex with its coreceptor, the C-terminal domain of TolA. Structure Fold. Des., 7, 711–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A. (1997) Predicting coiled-coil regions in proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 7, 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meritt E.A. and Murphy,M.E.P. (1994) Raster3D Version 2.0. A program for photorealistic molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D, 50, 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi K., Deane,C.M., Blundell,T.L., Johnson,M.S. and Overington,J.P. (1998) JOY: protein sequence-structure representa tion and analysis. Bioinformatics, 14, 617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeck G.S. and Letellier,L. (2001) Characterization of in vitro interactions between a truncated TonB protein from Escherichia coli and the outer membrane receptors FhuA and FepA. J. Bacteriol., 183, 2755–2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin,A.A. and Dodson,E.J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D, 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel de Zwaig R. and Luria,S.E. (1967) Genetics and physiology of colicin-K tolerant mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 94, 1112–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H. (1992) Porins and specific channels of bacterial outer membranes. Mol. Microbiol., 6, 435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M. and Witten,C. (1967) Interaction of colicins with bacterial cells. III. Colicin tolerant mutations in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 94, 1093–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. and Minor,W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol., 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porod G. (1951) Die Röntgenkleinwinkelstreuung von dichtgepackten kolloiden Systemen. Kolloidzeitschrift, 124, 83–114. [Google Scholar]

- Raggett E.M., Bainbridge,G., Evans,L.J.A., Cooper,A. and Lakey,J.H. (1998) Discovery of critical tol A-binding residues in the bactericidal toxin colicin N: a biophysical approach. Mol. Microbiol., 28, 1335–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann L. and Holliger,P. (1997) The C-terminal domain of TolA is the coreceptor for filamentous phage infection of E.coli. Cell, 90, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R.B. and Barton,G.J. (1992) Multiple protein sequence alignment from tertiary structure comparison. Proteins: Structure Funct. Genet., 14, 309–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A. and Blundell,T.L. (1990) Definition of general topological equivalence in protein structures. A procedure involving comparison of properties and relationships through simulated annealing and dynamic programming. J. Mol. Biol., 212, 403–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schendel S.L., Click,E.M., Webster,R.E. and Cramer,W.A. (1997) The TolA protein interacts with colicin E1 differently than with other group A colicins. J. Bacteriol., 179, 3683–3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenyuk A.V. and Svergun,D.I. (1991) GNOM—a program package for small-angle scattering data processing. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 24, 537–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G.M. (1997) Patterson superposition and ab initio phasing. Methods Enzymol., 276, 628–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Blundell,T.L. and Mizuguchi,K. (2001) FUGUE: sequence–structure homology using environment-specific substitu tion tables and structure-dependent gap penalties. J. Mol. Biol., 310, 243–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliz P., Engelmann,R., Hengstenberg,W. and Pai,E.F. (1997) The structure of enzyme IIAlactose from Lactococcus lactis reveals a new fold and points to possible interactions of a multicomponent system. Structure, 5, 775–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgis J.N. (2001) Organization and evolution of the tol–pal gene cluster. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 3, 113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T.-P. and Webster,R.E. (1986) fii, a bacterial locus required for filamentous phage infection and its relation to colicin-tolerant tolA and tolB. J. Bacteriol., 165, 107–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T.-P. and Webster,R.E. (1987) Nucleotide sequence of a gene cluster involved in entry of E colicins and single-stranded DNA of infecting filamentous bacteriophages into Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 169, 2667–2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svergun D., Barberato,C. and Koch,M.H.J. (1995) CRYSOL—A program to evaluate X-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 28, 768–773. [Google Scholar]

- Svergun D.I., Petoukhov,M.V. and Koch,M.H.J. (2001) Determination of domain structure of proteins from X-ray solution scattering. Biophys. J., 80, 2946–2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towns-Andrews E., Berry,A., Bordas,J., Mant,P.K., Murray,K., Roberts,K., Sumner,I., Worgan.J.S. and Lewis,R. (1989) Time-resolved X-ray diffraction station: X-ray optics, detectors and data acquisition. Rev. Sci. Instrum., 60, 2346–2349. [Google Scholar]

- van Duyne G.D., Standaert,R.F., Karplus,P.A., Schreiber,S.L. and Clardy,J. (1993) Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J. Mol. Biol., 229, 105–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf E., Kim,P.S. and Berger,B (1997) MultiCoil: A program for predicting two and three-stranded coiled coils. Protein Sci., 6, 1179–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]