Abstract

In the icosahedral (T = 4) Semliki Forest virus, the envelope protomers, i.e. E1–E2 heterodimers, make one-to-one interactions with capsid proteins below the viral lipid bilayer, transverse the membrane and form an external glycoprotein shell with projections. The shell is organized by protomer domains interacting as hexamers and pentamers around shell openings at icosahedral 2- and 5-fold axes, respectively, and the projections by other domains associating as trimers at 3- and quasi 3-fold axes. We show here, using cryo- electron microscopy, that low pH, as occurs in the endosomes during virus uptake, results in the relaxation of protomer interactions around the 2- and the 5-fold axes in the shell, and movement of protomers towards 3- and quasi 3-fold axes in a way that reciprocally relocates their putative E1 and E2 domains. This seemed to be facilitated by a trimerization of transmembrane segments at the same axes. The alterations observed help to explain several key features of the spike-mediated membrane fusion reaction, including shell dissolution, heterodimer dissociation, fusion peptide exposure and E1 homotrimerization.

Keywords: alphavirus/cryo-EM/glycoprotein/image reconstruction/membrane fusion

Introduction

Enveloped viruses have evolved mechanisms of membrane budding and fusion in order to be released from, and penetrate into, host cells. Viral budding appears, in most cases, to be facilitated by the oligomerization of membrane proteins into an organized layer in the host membrane, which subsequently attracts other viral components (Garoff et al., 1998). Viral membrane fusion, on the other hand, is directed by viral protein determinants, which, after activation, project outward from the virus to interact with the lipid bilayer of a target cell and cause virus–cell membrane merging (Skehel and Wiley, 2000). The viral budding and fusion processes are likely to be highly interdependent because, for instance, membrane fusion requires an ordered dissolution of the membrane protein layer used for budding. However, viral control mechanisms for such sequential events are as yet unknown.

We have studied this problem using the alphavirus Semliki Forest virus (SFV) as a model. SFV buds at the surface of host cells and enters new ones through the endosomes by a low-pH-induced fusion process (Acheson and Tamm, 1967; Marsh and Helenius, 1980; White and Helenius, 1980). Analyses by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have shown that the virus is composed of an icosahedral (T = 4) nucleocapsid (NC), surrounded by a lipid bilayer with similarly arranged membrane glycoproteins (Vogel et al., 1986; Cheng et al., 1995; Mancini et al., 2000). The capsid (C) monomers are grouped into hexameric and pentameric capsomers at the 2- and 5-fold axes. The glycoprotein protomers, i.e. the E1–E2 membrane protein heterodimers, make one-to-one interactions with C monomers below the viral membrane, transverse the lipid bilayer and organize a glycoprotein shell with spikes or projections on the outside. The major interactions in the shell are formed between protomeric domains that are arranged into hexameric and pentameric rings around shell openings at 2- and 5-fold axes. From this region, portions of the protomers rise into trimeric projections at 3- and quasi (q) 3-fold axes. However, the two subunits do not seem to follow each other in the region of the projection (Lescar et al., 2001). While the E2 molecule conveys a vertical path to the spike tip, the E1 appears to take a rather oblique one. Consequently, the subunit of the original protomer will uncouple and establish a new heterodimeric interaction in the tip with the subunit of the neighboring protomer instead. The latter interaction seems to involve the membrane fusion peptide of SFV, which is located in the membrane-distal part of the E1 subunit.

This organization of the alphavirus glycoproteins has brought about a model for how glycoprotein interactions in the shell control both budding and entry reactions. Accordingly, glycoprotein interactions around the 2- and 5-fold axes in the shell promote budding at the surface of the infected cell, whereas their dissociation, induced by low pH in the endosomes, facilitates the shell dissolution and subunit reorganization in the spike region necessary for membrane fusion (Garoff and Cheng, 2001). Recently, we provided structural evidence that the glycoprotein interactions in the shell are, indeed, able to direct formation of the icosahedral envelope of an alphavirus (Forsell et al., 2000). In that study, an NC assembly-defective mutant was demonstrated to form particles with correct conformation. Earlier, it was thought that membrane assembly and budding were merely a consequence of glycoprotein binding to a preformed NC. In the present work, we have studied how a mild acidic condition affects the SFV glycoproteins. The acid condition induced a relaxation of glycoprotein protomer interactions around 2- and 5-fold axes in the shell, and movement of putative E1 and E2 domains towards 3- and q3-fold axes in a way that reciprocally switched their location within the protomer. Simultaneously, the spikes increased in height. These alterations can explain how the dissolution of the viral glycoprotein shell can be linked to conformational changes in the spikes needed for activation of the membrane fusion function.

Results

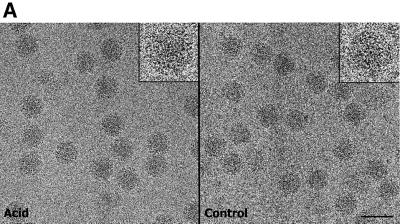

pH threshold for virus aggregation

Biochemical experiments have demonstrated that the low-pH-induced membrane fusion activity of the SFV spikes has a threshold of pH 6.2 and an optimum at pH 5.5 (White and Helenius, 1980). However, initial morphological analyses of virus treated with pH 5.5 buffer showed particle aggregations and hence was useless for image analyses. The pH threshold where the virus still appeared as well-defined single particles was therefore determined by EM. We found a clear threshold at a pH of ∼5.9. At this pH, the virus particles were still seen as separate entities (Figure 1A), whereas they were aggregated at pH 5.8 (data not shown). Particle size distribution was examined at pH 5.9 as well as at pH 6.2 (the fusion threshold) and 7.4 (the control). The results showed that the low-pH treatment resulted in increased particle diameter (Figure 1B). Thus, while the control virus had a mean diameter of 680 Å, the diameter for the pH 6.2- and 5.9-treated viruses had increased to 685 and 695 Å, respectively. The size variation was smaller at pH 5.9 than at pH 6.2, suggesting that the particles transformed into a more defined structure. Consequently, virus treated with pH 5.9 buffer was selected for further image analyses.

Fig. 1. Morphology and size distribution of SFV particles at pH 5.9 and 7.4. (A) Cryo-EM micrographs showing the SFV morphology after exposure to pH 5.9 and 7.4. The virus was subjected to the respective pH and incubated for 60 s before being vitrified by plunge freezing in liquid ethane. Both pH conditions show well-separated virus particles that could be analyzed further by 3D reconstruction procedures. Scale bar, 1000 Å. (B) Size distribution of the SFV particles at pH 5.9, 6.2 and 7.4, as calculated from the orientation-corrected virus particles in the cryo-EM micrographs. The averaged particle diameter at pH 7.4 was used as reference and set to 1. The curves represent Gaussian distribution fits to grouped diameter values (2.7 Å intervals). The total number of particles in each sample was >900. Student’s t-test confirmed the existence of three distinct populations of particle size.

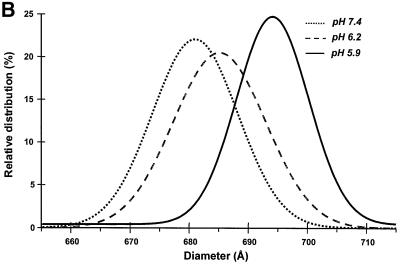

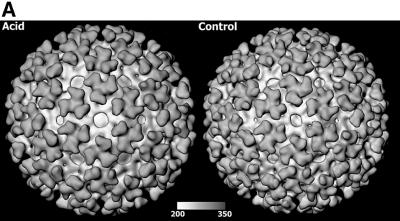

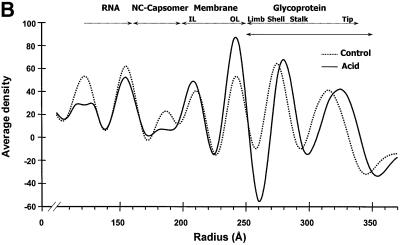

Elevation of the glycoprotein shell away from the lipid layer

While the overall organization of the SFV structure appeared preserved at the acid pH, as compared with the control (Figure 2A), there were some major differences. The most apparent one was an elevation of the entire shell-spike layer in relation to the viral lipid bilayer. This was evident by comparing the two SFV structures in one-dimensional (1D) radial density plots and in cross-section analyses of the equatorial planes (Figure 2B and C). These analyses showed that the lipid bilayer remained approximately at the same position as in the control, with phospholipid head groups at radii 242 and 208 Å, while the shell was lifted 4–6 Å further outwards away from the lipid bilayer. This was an obvious reason for the increase in particle diameter as observed in the size distribution plot of the whole-particle preparation (Figure 1B). Another prominent feature in the shell domain was a widening of the holes at the 2- and the 5-fold axes, and a sideways shrinkage of the occupied shell area. The diameter of the openings increased from 40 to 51 Å at the 2-fold axes, and from 15 to 31 Å at the 5-fold axes, while the distance between the edges of two 2-fold holes decreased from 124 to 116 Å, and between one 2-fold and one 5-fold hole from 125 to 110 Å. These general observations inspired us to carry out a more detailed analysis of the pH 5.9-treated virus.

Fig. 2. Cryo-EM reconstructions of SFV treated at pH 5.9 and 7.4. (A) SFV 3D rendering of cryo-EM reconstructions, viewed along the 2-fold axis, of virus treated at pH 5.9 (left) or 7.4 (right). Both structures contain 80 trimers in a T = 4 arrangement where the projecting spikes form stems with three bilobed petals at the tip. The spike bases are edged by a horizontal support, which connects the spikes into an almost continuous shell above the lipid bilayer. Holes are present at 2- and 5-fold axes. Note that the openings become larger with the acid treatment. (B) Radial density plot of the reconstructed SFV particles at pH 5.9 (solid line) and 7.4 (dotted line). The different radial domains of the virion are indicated at the top. IL and OL indicate the inner and outer layer of phospholipid headgroups, respectively. Limb indicates glycoprotein connections between the shell and the lipid bilayer. Note the elevation of the shell and projections of the acid-treated virus in relation to the lipid membrane, which remained approximately in the same position as in the control. (C) Equatorial cross-sections of the reconstructions of SFV from conditions of pH 5.9 (upper left) and pH 7.4 (upper right). The symmetry axes as well as a radial scale are marked in the latter section. At the bottom, a part of the reconstruction of the control is shown. This is overlayered with contour lines of the densities of the outer phospholipid headgroup layer and glycoproteins, from reconstructions of the control (green) as well as the acid-treated (red) virus. Note the acid-induced elevation of the shell with projections, whereas the outer phospholipid headgroup layer stays at the corresponding radial position in both maps.

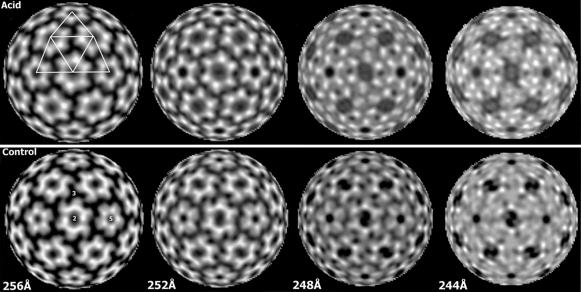

Alterations in shell organization

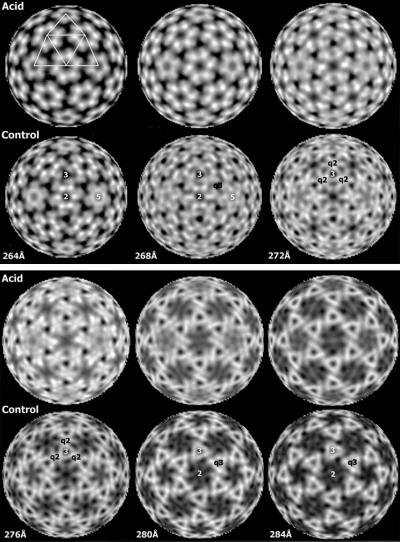

In the 1D radial density plot, the position of the shell region is indicated by the peak at 275 and 280 Å of the control and acid-treated virus, respectively (Figure 2B). Radial density profiles (Figure 3) at increasing radii through the shell region of the control revealed initially a hexameric and pentameric arrangement of very pronounced densities around 2- and 5-fold axes, in addition to weaker, trimeric ones appearing around 3- and q3-fold axes (Figure 3, sections at 264 and 268 Å of control virus). Following the shell models of Lescar et al. (2001) and Pletnev et al. (2001), one can tentatively assign the densities around the 2- and 5-fold axes to the immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains of the E1 subunit, and those around 3- and q3-fold axes to parts of the E2 subunit. Higher up in the shell region, two pairs of ‘E1’ and ‘E2’ densities appeared to merge at q2-fold axes, i.e. at a position between two neighboring spikes (Figure 3, sections at 272 and 276 Å of control). Eventually, densities around 3- and q3-fold axes became prevailing, most likely marking the beginning of the stalk region of the glycoprotein projection (Figure 3, sections at 280 and 284 Å of the control virus).

Fig. 3. Radially cued density of the glycoprotein shell. Densities are viewed along an icosahedral 2-fold axis with a 4 Å step size from 264 to 284 Å for acid-treated and control virus. High-to-low densities are indicated with a gray scale color scheme. Characteristic shell patterns are similarly seen to relieve each other at increasing radii in both preparations, but they appear ∼4 Å higher up in the acid-treated virus than in control because of the shell elevation in the former virus. In the acid-treated virus, note the spreading of glycoprotein domains in the lower part of the shell region (268 Å) away from the tight positions around the 2- and 5-fold axes seen in the control (264Å). At higher radius, in the upper part of the shell region, one starts to discern the formation of stems in the projections at 3- and q3-fold axes. The density at radius 264 Å of acid-treated virus is overlaid with a T = 4 lattice to illustrate the spike positions relative to the 5-, 3- and 2-fold symmetry axes, which are marked in the control. The centers of the facets represent positions of restricted and q3-fold axes in an icosahedral face.

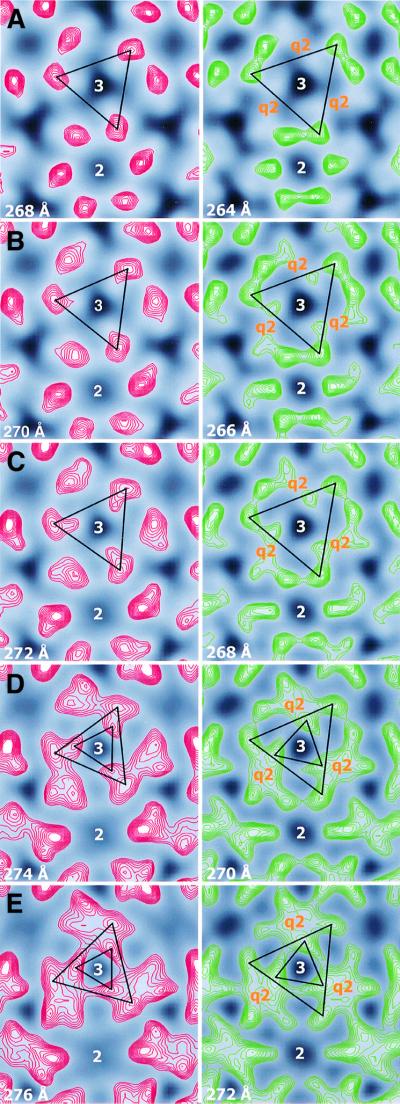

Corresponding density profiles were observed in the acid-treated virus when examining its shell region at increasing radii (Figure 3). However, because of the shell elevation, the corresponding profiles appeared at slightly higher radii (∼4–6 Å). Furthermore, in accordance with the widening of the shell openings, we found that the densities forming the rings around the 2- and 5-fold axes were not as tightly packed as in the control, but instead appeared more spread out (Figure 3, compare sections at 264 and 268 Å of control and acid-treated virus, respectively). This was very evident when comparing the positions of the peak densities around the 2-fold axes (the putative E1 domains), at several closely following radii (2 Å apart) in lower and middle parts of the shell region, between the two structures (Figure 4). Their mean distance to the 2-fold axis increased ∼10 Å in the acid-treated as compared with the control virus. As a consequence, the density peaks traceable to one trimeric projection (Lescar et al., 2001) approached each other at the 3-fold axes. This is illustrated in the panels by connecting the ‘E1’ density peaks corresponding to a 3-fold projection with a triangle. The peak-to-peak distance in this triangle decreased by ∼14 Å and the distances from triangle vertex to 3-fold axis by ∼8 Å upon acid treatment. The density peaks assumed to represent E1 domains were found to be merged with additional, possibly E2-related densities, forming characteristic four-peak densities at q2-fold axes in the middle part of the shell in control (sections at 270 and 272 Å) and acid-treated virus (sections at 274 and 276 Å). Connecting the ‘E2’ density peaks of one trimeric spike by a triangle, the peak-to-peak distance in this smaller triangle was also found to be shorter (∼8 Å) in the acid-treated than in the control virus.

Fig. 4. Density peaks of the glycoprotein shell at defined radii of acid-treated and control SFV. Peaks of densities around 2-, 3- and q3-fold axes are shown with red and green contour lines for five pairs of roughly equivalent, consecutive radial sections (2 Å apart) in the lower and middle shell regions of acid-treated and control virus, respectively. The sections of acid-treated virus in each pair are taken at 4 Å higher radius than those of control virus, due to the elevation of the shell layer. Density peaks around the 2-fold axis can tentatively be assigned to the Ig-like domain of the E1 subunit (Lescar et al., 2001). At both lower and higher radial cut, one can observe the latter density moving away from the 2-fold axis in approaching the 3- or the q3-fold axes upon acid treatment. Furthermore, at the higher radial cut, one discerns strong densities close to the 3- and q3-fold axes, which probably correspond to parts of E2. These densities also redistributed, in particular they withdraw from q2-fold axes, as a consequence of acid treatment. To better visualize the acid-induced protein relocations in the shell, the ‘E1’ and ‘E2’ density peaks of one 3-fold spike have been connected, forming a large and a small equilateral triangle, respectively. As can be seen, a size decrease as well as a counterclockwise turning of the larger triangle demonstrate the movement of the ‘E1’ peaks. Similarly, a size decrease, but a clockwise turning of the small triangle, show the movement of the ‘E2’ peaks. Note the reciprocal relocations of the putative E1 and E2 domains belonging to one protomer.

In addition, the acid treatment resulted in opposite rotations of the two triangles; the ‘E1’ triangle rotated counterclockwise, whereas the ‘E2’ triangle turned clockwise. In the bottom part of the shell, there was little (1°) difference in orientation of the two ‘E1’ triangles between the two reconstructions. Passing upwards through the shell to radius 276 Å in the acid-treated virus, the ‘E1’ triangle rotated counterclockwise 24°, whereas the corresponding rotation in the control was only 6°. Thus, there was a 19° rotation difference between the two ‘E1’ triangles in the middle shell layer. As the smaller ‘E2’ triangle of the acid-treated virus turned ∼23° clockwise, compared with that of the control, there was altogether a 42° reciprocal shift in location of putative E1 and E2 domains belonging to the same spike protomer in the shell region. Another consequence of the opposite rotations of the ‘E1’ and ‘E2’ triangles upon acid treatment was that putative E2 domains moved away and E1 domains approached q2-fold axes, thus reshaping the common four-peak densities seen around the same axis regions (Figure 4E). This corresponded to the decreased distance between shell openings described before (Figure 2A). Similar results were obtained by analyses of density peaks around 5- and q3-fold axes (data not shown). We conclude that the low pH caused a significant movement of glycoprotein subunits in the shell region.

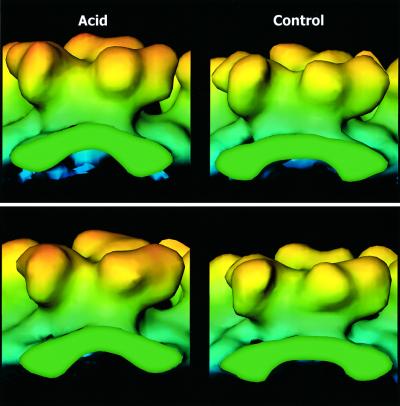

Spike extension

Analyses of density profiles at increasing radii above the shell revealed successively growing extensions to the vertices of the triangular stalk in the spike in both reconstructions. These transformed into three bilobed petals surrounding a narrow central cavity, such as that commonly observed in alphaviruses (e.g. Cheng et al., 1995). However, a closer comparison between the two reconstructions showed that the shapes of these spikes were different. This is shown in a side view of a q3-fold spike, viewed from the q2-fold axis, including a section view of the shell region at the base of the spike (Figure 5, top two panels). The comparison reveals how the above mentioned acid-induced compression of the ‘E1’ shell domains, symmetry related at the q2-fold axis, is linked to a reshaping of the whole spike: the stalk becomes longer, the lobes of the petals alter, the central valley between the petals at the tip becomes deeper and the whole spike gains ∼5 Å in height, measured from the upper shell region. A comparison of spikes at an icosahedral 3-fold axis showed similar differences (Figure 5, bottom two panels).

Fig. 5. Spike morphology in acid-treated and control virus. Panels show the radial colour-cued rendering of the spike densities at a q3-fold axis (upper panels) and a 3-fold axis (bottom panels) in acid-treated and control virus, respectively. The figures represent side views of spikes, observed from q2-fold axes. The underlying shell region is included. Note the acid-induced compression of the shell region and the concomitant extension of the spike.

In Figure 6 (top two panels), we have analyzed spike densities in a vertical plane parallel to the predicted orientation of one E1 subunit (rotated 23° off the 2-fold plane) in a spike at a q3-fold axis (Lescar et al., 2001) of acid-treated and control virus. In both cases, we observed a strong and continuous density that originated in the ‘E1’ shell around the 2-fold axis and projected obliquely upward toward the lower part of the spike tip on the opposite side. This density probably corresponded to E1 when forming the shell region at the q2-fold axis and one side of the spike stem. A comparison between the reconstructions showed that the ‘E1’ followed a straighter and somewhat steeper path in acid-treated virus than in that of the control. This is also evident when comparing the shell density profiles at the q2-fold axis in Figure 5. In this case, two symmetry-related E1 subunits form each side (half) of the density profile. These results suggest that most of the acid-induced shell elevation, spike extension and reshaping might actually be the result of the altered path taken by E1 after acid treatment. In the bottom two panels of Figure 6, we have analyzed the densities in a vertical plane parallel to that shown in Figure 5, but through the spike center. Here, the spike cavity is seen as a dome-like structure. The dome is much higher in the spike of the acid-treated virus than that of the control virus. This is consistent with the altered path taken by the E1 subunit in the spike stem.

Fig. 6. Internal features of spikes in acid-treated and control virus. Upper panels show a q3-fold spike in acid-treated and control virus, respectively, which has been cut in a vertical plane, parallel to the predicted orientation of the central and finger-like domains of the E1 subunit as described in Lescar et al. (2001). Note the continuous density that originates in the ‘E1’ domain in the shell and rises obliquely towards the lower part of the spike tip on the opposite side. Note also the apparent straightening and steepening of the path of the E1 subunit, when it rises from the lower shell region in the spike of the acid-treated virus as compared with the control. Lower panels show a vertical section through the middle of the spike in a plane parallel to that shown in Figure 5 (upper panels). Note the dome-like cavity in the spike center and its increased height in the case of the spike of the acid-treated virus.

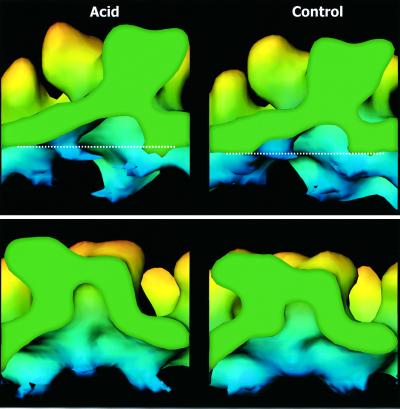

Relocations of glycoprotein limbs and transmembrane segments

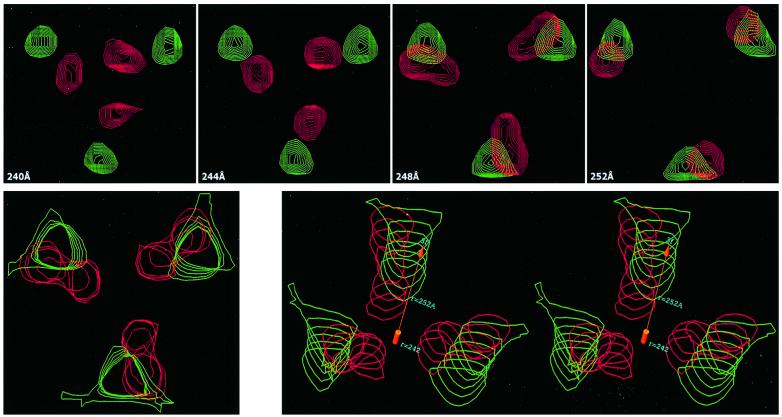

The glycoprotein limbs that separate the shell from the lipid bilayer appeared in the 1D density plot as a low-density notch with a minimum at 258 and 260 Å for the reconstructions of control and acid-treated virus, respectively (Figure 2B). Radial density profiles at decreasing radii from the shell towards the outer membrane surface (Figure 7) revealed the limb densities as hexameric/pentameric clusters around 2- and 5-fold axes extending downwards from the ‘E1’ shell domains in both reconstructions. However, the limb densities of the acid-treated virus reconstruction formed a larger ring structure than that of the control (Figure 7, compare sections at 256 and 252 Å of acid-treated virus with those of the control). Thus, acid treatment seemed to cause a movement of the limbs away from the 2- and 5-fold axes, which corresponded to that of the ‘E1’ domains in the shell above. Surprisingly, this hexameric/pentameric density distribution changed, in the case of the acid-treated virus, into a trimeric density pattern at 3- and q3-fold axes at the level of the outer surface of the viral lipid bilayer (radius ∼251 Å), whereas it remained hexameric/pentameric in the control (Figure 7, compare sections at 248 and 244 Å of acid-treated virus with those of the control). This suggests that the transmembrane segments of the spikes, which connect the shell region via the limbs to the monomers of the underlying NC capsomers, rearranged from hexamers/pentamers around 2- and 5-fold axes into trimers of one spike at 3- and q3-fold axes as a result of the acid treatment. These unique features of the two reconstructions were maintained in the outer membrane layers where the transmembrane segment densities were still traceable down to a radius of ∼240 Å. Figure 8 shows an enlargement of the transmembrane segment/limb densities of one spike at the 3-fold axis, as they emerge from the outer membrane surface. A detailed superimposition of the same densities is also presented as a top view (lower left) and stereo view (lower right). At the lower radius (242 Å), the densities measured a mean distance from the 3-fold axis of 20 and 42 Å in acid-treated and control virus, respectively. From this region, the glycoprotein segments of the control virus can be seen to follow a rather straight path to the higher radius (252 Å), whereas those of the acid-treated virus make an S-turn at 248 Å, moving the segments away from the 3-fold axis (Figure 8, lower right).

Fig. 7. Radially cued densities above and below the outer surface of the lipid bilayer. Densities are shown viewed along an icosahedral 2-fold axis at a radius of 256, 252, 248 and 244 Å for acid-treated and control virus. The outer membrane surface is located at a radius of ∼251 Å. Note the formation of trimeric structures of transmembrane segments, belonging to one spike, at 3- and q3-fold axes at the level of the outer membrane surface and just below in acid-treated virus, instead of the hexameric and pentameric ring-like structures that are seen around the 2- and 5-fold axes of the control (sections at 248 and 244 Å). Note also that the hexameric/pentameric ring-like limb structures observed in the acid-treated virus above the membrane surface appear larger than those of the control (sections at 252 and 256 Å). T = 4 lattice and symmetry axes are indicated.

Fig. 8. Densities of transmembrane and limb segments at the outer membrane surface. Top panels: top view at the 3-fold axis showing density peaks corresponding to the transmembrane/limb segments of one spike, parallel to the outer membrane surface of control (green) and acid (red) treated virus at radii of 240–252 Å with 4 Å step size. Bottom panels: a stack of overlayered radial sections (left) with 2 Å step size of the transmembrane/limb segments of one spike at the external membrane surface, shown in the same view and with the same color coding as above. Tilted view of the same density presented as a stereo pair (right) with the 3-fold axis marked as an orange arrow. Note the sideways relocation of the transmembrane segments towards the 3-fold axis at a radius of ∼248 Å, i.e. close to the membrane surface, in the acid-treated virus. The density contour is displayed at 1 SD above the mean value.

Density changes below the viral membrane

When we followed the pattern of radial density distribution at increasing radii within the NC of the control and the acid-treated SFV reconstruction, we could eventually discriminate hexameric and pentameric capsomers at a radius of ∼156 Å (data not shown). These became more distinct at ∼170 Å and disappeared at ∼200 Å, where the density of the lipid bilayer started. Notably, the acid-treated particles were lacking a clear density seen in the middle of the capsomer rings of the control, just below the membrane. In the 1D density plot, the C capsomer peak, with a maximum at ∼185 Å in the control, was correspondingly reduced in the acid-treated virus (Figure 2B).

Discussion

In order to elucidate the molecular mechanisms for the activation of the membrane fusion function of alphavirus, as it occurs in the acid endosomes of a cell, we have analyzed SFV, incubated in a low-pH buffer, for structural alterations by cryo-EM. Our analyses were performed at pH 5.9, which is suboptimal for virus fusion, because virus aggregation at pH 5.8 and below prohibited cryo-EM studies at the optimal pH 5.5. Nevertheless, the structural alterations observed in pH 5.9-treated virus are highly relevant to the activation process of the viral membrane fusion function. The fact is that earlier biochemical experiments have demonstrated that the membrane fusion activity of the SFV glycoproteins has an initiation threshold of pH 6.2, i.e. significantly above the pH 5.9 used in our experiments (White and Helenius, 1980; Kielian, 1995). In addition, time course analyses of SFV incubation with liposomes have shown that significant membrane fusion (∼60% of the fusion at optimal condition) could be achieved at pH 5.85, 20°C and 60 s, i.e. at conditions very similar to those used in the present study (pH 5.9, 20°C and 60 s) (Bron et al., 1993). This in vitro fusion reaction was shown to be preceded by alterations in glycoprotein oligomerization that are typical for fusion in vivo (Wahlberg and Garoff, 1992; Wahlberg et al., 1992; Duffus et al., 1995; Kielian, 1995). It was also demonstrated that virus incubated under these conditions, but in the absence of liposomes, was inactivated. This was probably the result of virus aggregation, as observed by us.

Our cryo-EM analyses revealed that the acid treatment caused major changes in the glycoprotein shell. Generally, this was observed as an elevation of the shell layer further away from the lipid bilayer. Detailed analyses showed that the protomers moved away from their tight ring-like structures around 2- and 5-fold axes in the shell towards the 3- and q3-fold axes. This change was accompanied by an intriguing rotation of putative E1 and E2 domains, respectively, in opposite directions. Within the same protomer, this was seen as a reciprocal relocation of putative E1 and E2 domains (see Figure 4). Furthermore, the E1 subunit followed a straighter and somewhat steeper path from the shell region into the projection, and the latter increased in length. Finally, we observed a rearrangement of the transmembrane segments from a hexamer/pentamer arrangement around the 2- and 5-fold axes to a trimeric arrangement at 3- and q3-fold axes. Our interpretation is that the low pH causes a relaxation of interactions between glycoprotein protomers around 2- and 5-fold axes, and induces a trimerization of their transmembrane domains at 3- and q3-fold axes. Together, these events allow the protomers, belonging to the same trimeric projection, to move tighter together in the shell region and the underlying subunits to take a reciprocal relocation. As a consequence, the E1 subunits, which are obliquely oriented between two E2 subunits in the projection, will be tilted into a steeper position, causing both shell elevation and spike extension. The trimerization of the transmembrane segments might also cause a reorganization of the capsid-binding internal glycoprotein tails, which could be reflected by the density changes that we observed in the outer region of the NC capsomers.

The acid-induced alterations observed here are likely to promote the membrane fusion process in several ways. First, the relaxation of the shell interaction around the 2- and 5-fold axes facilitates shell dissolution necessary for a successful membrane fusion reaction. Secondly, the reciprocal movement of the E1 and E2 domains in the shell would probably alter the E1–E2 interaction in the spike tip. Altogether this may lead to a general destabilization of the E1–E2 heterodimer and represent the basic mechanism in unmasking the membrane fusion-active peptide, which is located at the tip of the E1 subunit, by low pH. Further changes in the spike are then required to complete the membrane fusion reaction. These probably include the formation of a E1 homotrimer, as observed in biochemical analyses of SFV fusion (Wahlberg and Garoff, 1992; Wahlberg et al., 1992; Bron et al., 1993; Justman et al., 1993). The latter reaction appears difficult to explain using the membrane structure models of Lescar et al. (2001) and Pletnev et al. (2001) with peripheral E1 and central E2 subunits in the spike. However, our present results provide an attractive solution for this dilemma. If the reciprocal relocation process of E1 and E2 domains that we observe in pH 5.9-treated virus continues further, under conditions of optimal pH for fusion, E1 will move around the E2 subunit from the outside and eventually find free space between two E2 subunits to enter the spike center for trimerization.

Interestingly, a rapid spray technique was used earlier to expose SFV to pH 5.0 buffer before cryo-EM analyses (Fuller et al., 1995). Although no changes were detected in the shell region from that study, spike alterations were found that are consistent with E1 swiveling around E2. An earlier X-ray solution scattering (Stubbs et al., 1991) study of Sindbis virus at pH 5.0 suggested a more drastic increase in spike height (40 Å) than that we observed here at pH 5.9. This could mean that the E1 subunits obtain an almost vertical orientation relative to the membrane when joining as a homotrimer.

Our proposed mechanism for the activation of alphavirus fusion function is probably shared by other viruses, like the flaviviruses, with similar glycoprotein shells. This model differs significantly from those proposed for e.g. influenza and retroviruses (Skehel and Wiley, 2000). The latter models involve exposure of a hidden fusion peptide through the transformation of a helix–loop–helix structure into an extended helix in the context of a homotrimeric fusion protein. These dissimilar mechanisms for fusion activation have probably evolved to suit viral envelopes with distinct structures, i.e. the alphavirus envelope, with an icosahedral glycoprotein shell surrounding the membrane, and the more flexible influenza/retrovirus envelope. The latter envelope is also, unlike that of alphavirus, known to accommodate many host proteins in addition to the viral ones (Ott, 1997; Hammarstedt et al., 2000).

Although our model can help to explain how the alphavirus is able to extend its spikes and expose the hydrophobic fusion peptides at their tips to interact with a target membrane, the mechanism of how membranes merge remains an enigma. In the case of the influenza and retroviruses, membrane merging is thought to result from a jack-knife-like folding event of the fusion-active polypeptides (Skehel and Wiley, 2000). In the context of the trimeric fusion protein, this has been observed as a transition from a structure with a three-helix bundle into one with a six-helix bundle. However, preliminary data from the crystal structure of the SFV fusion protein E1 indicate that this polypeptide predominantly folds into β-sheets (Lescar et al., 2001). Whether this fusion protein is still able to undergo a jack-knife-like folding event or whether a different mechanism is used to achieve membrane merging remains to be determined. The fact that the membrane fusion-related E1 homotrimers show a marked resistance towards SDS and protease digestion is clearly consistent with E1 undergoing a major conformational change during the fusion reaction (Wahlberg et al., 1992; Gibbons and Kielian, 2002).

In conclusion, we have characterized acid-induced rearrangements of glycoprotein interactions in the shell region that are likely to mediate the membrane fusion reaction of an alphavirus. As these interactions may also control virus formation by budding at the cell surface (Forsell et al., 2000; Cheng et al., 2001), we suggest that the glycoprotein shell of these viruses functions as a common regulator of both virus assembly and cell entry processes.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All chemicals used were purchased from Sigma Laboratories (Steinheim, Germany) and Life Technologies (Paisley, UK) if not stated otherwise.

Virus purification

BHK-21 cells were grown in BHK medium (Glasgow MEM) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, 10% tryptose phosphate broth, 2 mM glutamine, 20 mM HEPES (Sigma) and 20 µg/ml cholesterol. Confluent monolayers of BHK-21 cells in 225 cm2 T-flasks were infected with SFV, clone pSFV4 (Liljeström and Garoff, 1991), using a multiplicity of infection of 10 in BHK medium supplemented with 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine and 0.2% albumin. The infected cells were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 and tilted every 15 min to secure optimal virus distribution. At 1 h post-infection, the inoculum was removed and the cells washed twice with PBS++ (Dulbecco composition with 20 mM Mg2+ and 20 mM Ca2+) before fresh infection medium was added.

The virus-containing cell culture supernatant was collected after 18 h incubation and cleared from cell debris by repeated centrifugation in a Beckamn JA-10 rotor at 4°C for 45 min at 17 000 g. The virus was collected as a pellet by an 18 h centrifugation at 17 000 g and 4°C using the same rotor. The virus pellet was resuspended for 18 h in TNM buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2 pH 7.4) before further purification by isopycnic centrifugation. This was carried out with a 10–30% (w/w) potassium tartrate gradient in 0.1 M 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid pH 7.4, run at 100 000 g for 5 h at 4°C in a Beckman SW-40 rotor. The gradient was eluted from the bottom of the tube and virus identified by UV absorbance measurement. Virus-containing fractions were pooled and diluted with TNM buffer, and recovered by centrifugation in a Beckman SW-40 rotor at 100 000 g for 5 h at 4°C. Finally, the virus pellet was soaked in TNM buffer for 18 h at 4°C and resuspended by gentle pipetting. Negative-stain EM and SDS–PAGE were routinely used to check the quality of purified virus. To avoid structural damage due to storage procedures such as freezing and thawing, all experiments were performed with freshly produced virus kept at 4°C.

Acid treatment of virus particles

Virus particles, in TNM buffer pH 7.4, were mixed at room temperature (20°C) in a 1:1 ratio with a pre-titrated 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid buffer supplemented with 50 mM NaCl and 10 mM MgCl2. To determine the pH of the buffer mixtures, larger volumes were mixed and pH measured using an ordinary pH electrode. The virus–buffer mixtures were sampled after 60 s incubation before being applied to the grid and analyzed by EM with negative contrasting using 2% uranyl acetate solution (Agar, Stansted, UK) and cryo-EM. The images of negatively stained particles were examined for major morphological changes such as particle aggregation and breakage.

Cryo-EM and image reconstruction

The virus samples were prepared for cryo-EM using an established vitrification procedure. Three microliters of the virus sample were applied on glow-discharged holey-carbon copper grids, blotted with filter paper (Whatman, Maidstone, UK), and vitrified by plunge freezing into liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen. Low-dose (<10 e–/Å2) images were recorded on Kodak SO163 films (Eastman, Kodak, Rochester, NY) at a nominal magnification of 28 000 using a Philips CM 120 microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) equipped with a Gatan 626DH cryo transfer system (Gatan, Oxford, UK) (Xing et al., 1999). Each area was exposed twice as focal pairs with 1 and 3 µm underfocus to facilitate image selection and orientation alignment from noisy data (Cheng et al., 1992). Micrographs were selected based on particle concentration, ice thickness, minimal astigmatism, specimen drift and defocus. Images fulfilling the above criteria were digitized on a Zeiss SCAI microdensitometer (Carl Zeiss, Englewood, Germany) using 14 µm step size, corresponding to 5 Å spacing per pixel at the specimen.

Data processing

Individual intact particles were manually boxed out to generate a stack of >900 particles for every pH condition. Data processing steps included particle orientation and size determination using the model-based EMPFT and EMIMGCMP program package (Cheng et al., 1994; Baker and Cheng, 1996). All steps were carried out on DEC alphastations, running the OSF system with an XP1000 processor (Compaq, Houston, TX). In an iterative process, intermediate 3D density maps were successively used as new models in refining the parameters of particle orientations similarly performed in previous work (Forsell et al., 2000). The particle size was assessed by comparing the raw images with back-projected images of the control virus reconstruction (Cheng et al., 1994, 1995). As the diameter of the control virus map was used as reference and set to 1, the best correlation coefficient between the data image and the calculated model was searched based on systematic grid interpolations of the 3D model in real space. The variation in particle diameter was determined with an accuracy of 0.1% and displayed by merging particles within 0.4% size variation, normalized to the total number of particles, and plotted using a normal distribution regression. The final reconstructions were calculated merging data to 24 Å resolution using 188 and 184 particles for the control and the acid-treated virion, respectively, with reliability assessed by Fourier-ring phase residues and R-factors (Cheng et al., 1992). The completeness of the data sampling was verified by eigenvalue spectra, giving all eigenvalues >1 or 10, where the numbers of the data images included in the reconstructions were better than the theoretical requirement (Fuller et al., 1996). No significant difference in density distribution was observed after the effect of contrast transfer function was systematically deconvoluted according to the defocus range of imaging (Cheng et al., 1994). Distinct features of the shell and the spike were resolution independent based on peak positions of the radial density profiles in a cut-off range between the spatial frequency of 25 and 35 Å–1. For the surface rendering, the 3D reconstruction was contoured at the value that represented the volume of the mass density (Xing et al., 1999). The 3D visualization was mainly carried out with the Iris explorer software (NAG, Inc., Downers Grove, IL) with custom-made modules (L.Bergman and R.H.Cheng, unpublished). The maps were displayed at the same threshold using a contour level of one standard deviation (SD) above the mean density of the map.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Ingrid Sigurdson for help in manuscript preparation, and Drs Mathilda Sjöberg and Ulrika Skoging-Nyberg for suggestions. We also acknowledge Dr Bomu Wu for helping in initial data processing. This work has been sponsored by grants from the Medical Research Council (MFR-12175), the Natural Science Research Council (NFR-11691 and B6150-19981061/2000) and the Swedish Structural Biology Network.

References

- Acheson N.H. and Tamm,I. (1967) Replication of Semliki Forest virus: an electron microscopic study. Virology, 32, 128–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T.S. and Cheng,R.H. (1996) A model-based approach for determining orientations of biological macromolecules imaged by cryoelectron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol., 116, 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bron R., Wahlberg,J.M., Garoff,H. and Wilschut,J. (1993) Membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus in a model system: correlation between fusion kinetics and structural changes in the envelope glycoprotein. EMBO J., 12, 693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R.H., Olson,N.H. and Baker,T.S. (1992) Cauliflower mosaic virus: a 420 subunit (T = 7) multilayer structure. Virology, 186, 655–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R.H., Reddy,V.S., Olson,N.H., Fisher,A.J., Baker,T.S. and Johnson,J.E. (1994) Functional implications of quasi-equivalence in a T = 3 icosahedral animal virus established by cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography. Structure, 2, 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R.H., Kuhn,R.J., Olson,N.H., Rossmann,M.G., Choi,H.-K., Smith,T.J. and Baker,T.S. (1995) Nucleocapsid and glycoprotein organization in an enveloped virus. Cell, 80, 621–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R.H., Hultenby,K., Haag,L., Forsell,K., Garoff,H., Hsieh,C.-E. and Marko,M. (2001) Bringing together high-and low-resolution data: electron tomography of budding enveloped alphavirus. Microsc. Microanal., 7, 104–105. [Google Scholar]

- Duffus W.A., Levy-Mintz,P., Klimjack,M.W. and Kielian,M. (1995) Mutations in the putative fusion peptide of Semliki Forest virus affect spike protein oligomerization and virus assembly. J. Virol., 69, 2471–2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsell K., Xing,L., Kozlovska,T., Cheng,R.H. and Garoff,H. (2000) Membrane proteins organize a symmetrical virus. EMBO J., 19, 5081–5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller S.D., Berriman,J.A., Butcher,S.J. and Gowen,B.E. (1995) Low pH induces swiveling of the glycoprotein heterodimers in the Semliki Forest virus spike complex. Cell, 81, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller S.D., Butcher,S.J., Cheng,R.H. and Baker,T.S. (1996) Three-dimensional reconstruction of icosahedral particles—the uncommon line. J. Struct. Biol., 116, 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garoff H. and Cheng,R.H. (2001) The missing link between envelope formation and fusion in alphaviruses. Trends Microbiol., 9, 408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garoff H., Hewson,R. and Opstelten,D.-J.E. (1998) Virus maturation by budding. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 62, 1171–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, D.L. and Kielian,M. (2002) Molecular dissection of the Semliki Forest virus homotrimer reveals two functionally distinct regions of the fusion protein. J. Virol., 76, 1194–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarstedt M., Wallengren,K., Pedersen,K.W., Roos,N. and Garoff,H. (2000) Minimal exclusion of plasma membrane proteins during retroviral envelope formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 7527–7532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justman J., Klimjack,M.R. and Kielian,M. (1993) Role of spike protein conformational changes in fusion of Semliki Forest virus. J. Virol., 67, 7597–7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielian M. (1995) Membrane fusion and the alphavirus life cycle. Adv. Virus Res., 45, 113–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescar J., Roussel,A., Wien,M.W., Navaza,J., Fuller,S.D., Wengler,G., Wengler,G. and Rey,F.A. (2001) The fusion glycoprotein shell of Semliki Forest virus: an icosahedral assembly primed for fusigenic activation at endosomal pH. Cell, 105, 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljeström P. and Garoff,H. (1991) A new generation of animal cell expression vectors based on the Semliki Forest virus replicon. Bio/Technology, 9, 1356–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini E.J., Clarke,M., Gowen,B.E., Rutten,T. and Fuller,S.D. (2000) Cryo-electron microscopy reveals the functional organization of an enveloped virus, Semliki Forest virus. Mol. Cell, 5, 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh M. and Helenius,A. (1980) Adsorptive endocytosis of Semliki Forest virus. J. Mol. Biol., 142, 439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott D.E. (1997) Cellular proteins in HIV virions. Rev. Med. Virol., 7, 167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnev S.V., Zhang,W., Mukhopadhyay,S., Fisher,B.R., Hernandez,R., Brown,D.T., Baker,T.S., Rossmann,M.G. and Kuhn,R.J. (2001) Locations of carbohydrate sites on alphavirus glycoproteins show that E1 forms an icosahedral scaffold. Cell, 105, 127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel J.J. and Wiley,D.C. (2000) Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 531–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs M.J., Miller,A., Sizer,P.J., Stephenson,J.R. and Crooks,A.J. (1991) X-ray solution scattering of Sindbis virus. Changes in conformation induced at low pH. J. Mol. Biol., 221, 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel R.H., Provencher,S.W., von Bonsdorff,C.-H., Adrian,M. and Dubochet,J. (1986) Envelope structure of Semliki Forest virus reconstructed from cryo-electron micrographs. Nature, 320, 533–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg J. and Garoff,H. (1992) Membrane fusion process of Semliki Forest virus I: low pH-induced rearrangement in spike protein quaternary structure precedes virus penetration into cells. J. Cell Biol., 116, 339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg J.M., Bron,R., Wilschut,J. and Garoff,H. (1992) Membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus involves homotrimers of the fusion protein. J. Virol., 66, 7309–7318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. and Helenius,A. (1980) pH-dependent fusion between the Semliki Forest virus membrane and liposomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 3273–3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L., Kato,K., Li,T., Takeda,N., Miyamura,T., Hammar,L. and Cheng,R.H. (1999) Recombinant hepatitis E capsid protein self-assembles into a dual-domain T = 1 particle presenting native virus epitopes. Virology, 265, 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]