Abstract

Blood-accessible biomarkers offer promising insights into the pathogenesis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and other muscle diseases. Here, we quantified the relative abundance of 7,289 serum proteins using SomaScan proteomics in pre-treatment samples from 51 boys with DMD (aged 4 to <7) and 13 healthy controls from the VISION DMD (VBP15-004) trial. An independent validation cohort of untreated DMD boys (aged 4 to <8) from the FOR-DMD trial was also analyzed. Of the proteins screened, 26% and 15% were significantly elevated and decreased, respectively, in the serum of young DMD boys compared to controls (adjusted p-value < 0.05). A high correlation (Spearman r = 0.85) in fold changes was observed between the two datasets. Many proteins with altered levels overlapped with known markers of muscle injury, inflammation, regeneration, and extracellular matrix remodeling. Selected biomarkers were queried in two published muscle mRNA and a muscle snRNAseq dataset in DMD biopsies. Novel factors involved in muscle regeneration and ECM remodeling were identified. This larger-scale, multi-clinical trial-based cohort study in untreated DMD boys substantially expands the catalog of circulating biomarkers, highlighting early-stage pathological processes. These findings can help identify new therapeutic targets and develop clinically actionable biomarkers to assess disease progression and response to therapies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-23758-6.

Keywords: Duchenne muscular dystrophy; Proteomics, SomaScan; Biomarker discovery-validation; Serum-muscle omics integration

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Biomarkers, Diseases, Medical research

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked, rare, and progressive neuromuscular disorder causing fibrosis, loss of motor function, and early death. Blood accessible protein biomarkers are becoming increasingly important for tracking disease progression, evaluating treatment responses, and ultimately establishing new therapeutic targets for DMD. There have been multiple innovations and technological advances in high-throughput serum/plasma protein profiling based on aptamers1 and mass spectrometry2,3. Previously, several circulating protein biomarkers have been identified and confirmed in independent DMD cohorts and across different laboratories4–6.

In our previous study5, we used Somalogic aptamer-based assay (SomaScan®) to screen the serum levels of 1,310 proteins in corticosteroid naïve DMD subjects and age matched healthy volunteers and identified 108 significantly elevated and 70 significantly decreased proteins (after multiple testing correction) in the DMD group relative to the healthy, unaffected group. These candidate biomarkers were grouped under four main categories, namely, muscle-specific proteins, extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, pro-inflammatory, and cell development factors5. The predominant category consisted mainly of muscle-specific proteins, including muscle enzymes and sarcomere proteins. The muscle-specific proteins were frequently found to be elevated at a young age compared to unaffected controls, subsequently declining over time due to a combination of loss of muscle mass and physical inactivity5,7. Conversely, pro-inflammatory biomarkers, such as chemokines and interleukins, exhibited only marginal increases in DMD subjects compared to control subjects, with their levels remaining stable over time8. On the other hand, extracellular matrix proteins and cell development factors were typically found to be reduced in the blood of individuals with DMD relative to controls and tended to further decline over time5.

Several DMD biomarkers identified by SomaScan have been confirmed in additional studies using orthogonal methods such as mass spectrometry and antibody affinity bead arrays, further corroborating their signal6,9. Notably, recent studies have illustrated the clinical relevance of certain DMD-specific biomarkers in evaluating disease progression and therapeutic responses10–13. This highlights the importance of blood circulating biomarkers in the drug development programs for DMD.

Despite significant advances in serum biomarkers highlighted above, previous reports had important limitations and gaps remain. Existing findings in the literature relied on natural history or clinical care-sourced biosamples with multiple confounding variables such as age and corticosteroid use. The number of measured proteins in these previous studies covered only a small portion of the quantifiable serum proteome (e.g., 1310 proteins), allowing insights only into a small part of the pathophysiological pathway; recent Somascan panel targeting 7,289 proteins more extensively cover molecular functions like receptors, kinases, growth factors and hormones, and span secreted, intracellular and extracellular proteins. For example, two previous studies using the same Somascan assay4,5, but with differences in age ranges and corticosteroid exposures, had a Spearman correlation of 0.31 between the fold changes obtained from DMD vs healthy control protein levels. Previous papers often only had a small set of patient biosamples, and/or did not have an independent cohort for validation, resulting in many protein targets not being validated across studies.

This study addresses these gaps by utilizing larger sample sizes and two independent DMD cohorts. This time, we used corticosteroid naïve biosamples with no freeze-thaw cycles, obtained from large-scale, regulator-audited clinical trials involving boys with DMD within a narrow age range (4–8 years old). Protein quantification was performed using the SomaScan assay (v4.1), which measures up to 7,289 protein targets. This approach enabled us to validate previously reported biomarkers and, with increased statistical power, identify additional novel biomarkers linked to various aspects of muscle pathogenesis in DMD. Our goal is to identify a comprehensive set of circulating protein biomarkers associated with muscle pathology, integrate these findings with existing muscle mRNA expression profiles14–16, and make the data accessible to researchers and clinicians for diverse clinical and translational applications in the muscular dystrophy field.

Results

Comprehensive serum proteome signature for corticosteroid naïve DMD

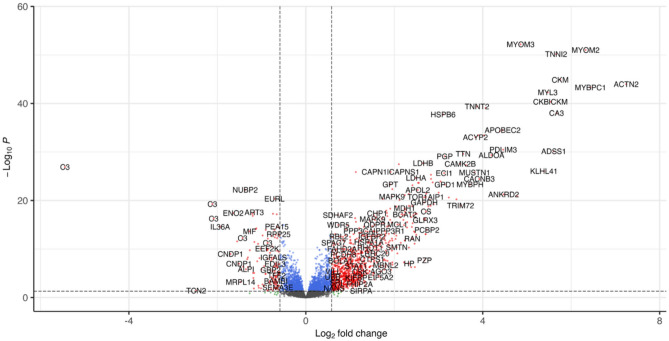

The relative levels of 7,289 protein targets were measured by SomaScan in serum samples from corticosteroid naïve DMD subjects (n= 51) enrolled through the VISION DMD cohort (VBP15-004 trial) (NCT03439670)17,18 and age matched healthy controls (n = 13). Figure 1A shows a volcano plot of significantly elevated and significantly decreased proteins in the DMD group vs. the control group. Among these 7,289 measured protein targets (6402 unique Uniprot IDs; 6596 unique Soma target names) and after adjusting for multiple testing, 1,881 showed significant increases, while 1,086 proteins demonstrated significant decreases in corticosteroid naïve DMD relative to control subjects (see Supplemental Table S1). Notably, 930 targets displayed a fold change of +1.5 or more, whereas 135 protein targets exhibited a fold change of −1.5 or less with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 .

Fig. 1.

Volcano plots showing elevated and decreased proteins measured by SomaScan assay in serum samples of DMD boys (n = 51) relative to age matched healthy controls (n = 13). Cut off was ± 1.5-fold change with adjusted p values < 0.05.

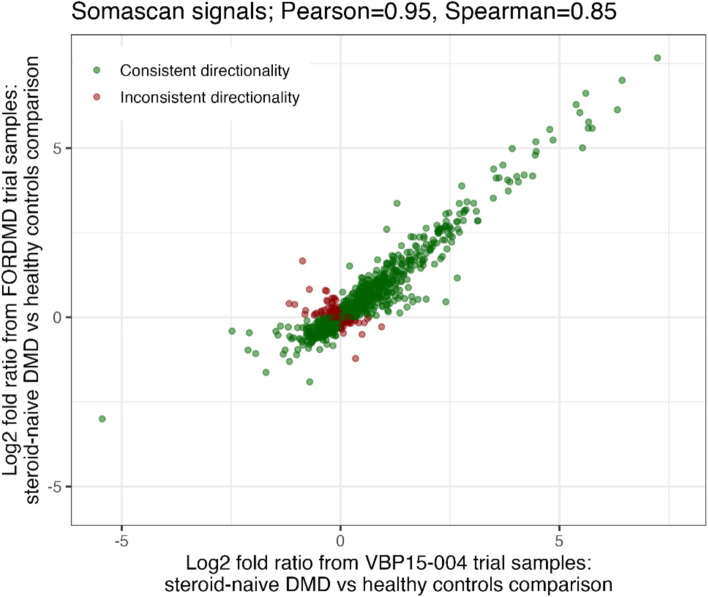

This SomaScan data was concordant with SomaScan data obtained using independent serum samples from a separate cohort of corticosteroid naïve DMD boys enrolled in the FOR-DMD trial (NCT01603407)19, alongside age-matched healthy controls from CINRG DNHS (NCT00468832) (12 samples). This analysis concentrated on a pre-selected set of 1,500 targets (1404 unique Uniprot IDs; 1475 Soma target names), out of which 720 were defined as statistically altered (FDR corrected p < 0.05). Of all 1,500 serum proteins analyzed, most showed consistent results between the VBP15-004 and FOR-DMD datasets with 81.6% with the same directionality, achieving a Pearson correlation and a Spearman correlation between the fold changes from the two datasets of 0.95 and 0.85, respectively (Figure 2). Out of the 771 targets defined as significantly altered (FDR corrected p < 0.05) between DMD and controls in the VBP15-004 dataset and present in the FOR-DMD dataset, 93% had the same directionality in the FOR-DMD validation dataset analysis.

Fig. 2.

Log2 fold changes from 1,500 overlapping serum proteins measured by SomaScan in serum samples from two independent DMD cohorts: VBP15-004 and FOR-DMD.

The fold changes of the shared biomarker candidates between the VBP15-004 and FOR-DMD cohorts were further compared to the fold changes obtained in earlier studies utilizing an older iteration of the Somascan assay5 (see Supplemental Table S1). Table 1. below shows an example of top 14 overlapping biomarkers that were confirmed across two independent cohorts studied herein.

Table 1.

Top 14 candidate biomarkers with positive and negative fold changes in untreated DMD patients compared to controls, as measured by SomaScan across two independent cohorts.

| Uniprot accession number | Protein name | VBP15-004 cohort (in this study) |

FOR-DMD cohort (in this study) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change | adj. P. val. | Fold change | adj. P. val. | ||

| Increased in DMD | |||||

| Q5VTT5 | Myomesin-3 | + 29.0 | 6.57E-53 | + 37.66 | 9.7E-48 |

| P54296 | Myomesin-2 | + 80.2 | 9.86E-52 | + 70.05 | 1.7E-33 |

| P48788 | Troponin I, fast skeletal muscle | + 50.5 | 6.8E-51 | + 48 | 1.55E-45 |

| P06732 | Creatine kinase M | + 53.9 | 1.33E-45 | + 47.96 | 1.3E-46 |

| P35609 | Alpha-actinin-2 | + 151.4 | 1.1E-44 | + 202.6 | 1.5E-45 |

| Q00872 | Myosin-binding protein C, slow-type | + 86.6 | 5.1E-44 | + 128 | 2.7E-46 |

| P08590 | Myosin light chain 3 | + 44.3 | 5.3E-43 | + 66.1 | 7.4E-46 |

| Decreased in DMD | |||||

| P01024 | Complement C3b | - 43.6 | 1.23E-27 | - 8.0 | 1.05E-10 |

| Q9Y5Y2 | Cytosolic Fe-S cluster assembly factor NUBP2 | - 2.6 | 6.24E-23 | - 1.2 | 1.51E-02 |

| P01024 | Complement C3b, inactivated | - 4.3 | 5.30E-20 | - 2.0 | 3.74E-08 |

| Q13508 | Ecto-ADP-ribosyltransferase 3 | - 2.2 | 2.75E-18 | - 2.5 | 4.97E-21 |

| Q99727 | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 4 | - 1.7 | 5.49E-18 | - 1.5 | 1.36E-11 |

| Q96EE4 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 126 | - 1.6 | 6.97E-18 | - 1.6 | 4.13E-14 |

| Q9UHA7 | Interleukin-36 alpha | - 3.8 | 2.60E-15 | - 2.1 | 5.62E-08 |

This new data not only confirmed previously identified biomarkers but also revealed additional novel circulating biomarker candidates reflecting muscle injury, ECM remodeling, muscle regeneration and immune and inflammation response. Novel data on these four types of biomarker signatures are presented below (please refer to Supplemental table S1 for all newly identified serum protein biomarkers in this study)

Muscle injury biomarkers

Over 35% of the elevated proteins identified in serum samples of young untreated DMD boys originated from muscle fiber damage and leakage into the bloodstream. The predominant category of these muscle injury biomarkers comprised sarcomere-associated proteins, such as newly identified alpha-actinin-2 (ACTN2), myosin binding protein C (MYBPC1), troponin I, fast skeletal muscle (TNNI2), myomesin-3 (MYOM3) and myomesin-2 (MYOM2), which exhibited significantly higher circulating levels-151, 86, 55, 29 and 80 times greater, respectively in young DMD boys compared to age-matched healthy controls. These were followed by well-known muscle enzymes, such as creatine kinase-M type (CKM) with a 54-fold increase, carbonic anhydrase-3 (CA3) with a 51-fold increase, and newly identified enzymes like adenylosuccinate synthetase isozyme 1 (ADSS1) with a 49-fold increase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase isozyme 2 (FBP2) with a 27-fold increase. Some of these markers were also strongly correlated, for example, CKM had a 0.81 and 0.79 correlation with ACTN2 in the VISION DMD dataset and in the FORDMD dataset respectively. In this extensive dataset, numerous newly identified mitochondrial enzymes, likely resulting from muscle damage, were also found to be significantly elevated in the serum of boys with DMD compared to healthy controls. These included succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid-coenzyme A transferase 1 (SCOT), which exhibited a 21-fold increase, enoyl-CoA delta isomerase 1 with an 8.7-fold increase, as well as dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase and acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, both showing a 7-fold increase. Additional newly identified muscle-specific proteins that were found elevated in the blood of DMD boys included Kelch-like protein 41 (KLHL41) with a 19-fold increase, ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 2 (ANKRD2) with a 22-fold increase, musculoskeletal embryonic nuclear protein 1 (MUSTN1) with a 14-fold increase, and tripartite motif-containing protein 72 (TRIM72) with an 11-fold increase. Figure 3 shows examples of new muscle injury biomarkers identified in this study and their fold changes in DMD versus controls across the two DMD cohorts. Please see Supplemental Table S1 for a detailed list of muscle injury biomarkers identified in this study.

Fig. 3.

Box plots of exemplar muscle injury biomarkers identified in serum of DMD subjects. Levels are shown in both VBP and FORDM cohorts compared to controls. ACTN2: Alpha-actinin-2; ADSS1: Adenylosuccinate synthetase isozyme 1; KLHL41: Kelch-like protein 41; TRIM72: Tripartite motif-containing protein 72; ANKRD2: Ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 2; MUSTN1: Musculoskeletal embryonic nuclear protein 1.

Extracellular matrix remodeling biomarkers

This is the second largest group of circulating proteins that were found significantly altered in their levels, with 45 elevated and 92 decreased extracellular matrix proteins in the untreated DMD group compared to the healthy control group (see sheet 4 under supplemental Table S1 for a detailed list of these extracellular matrix proteins).

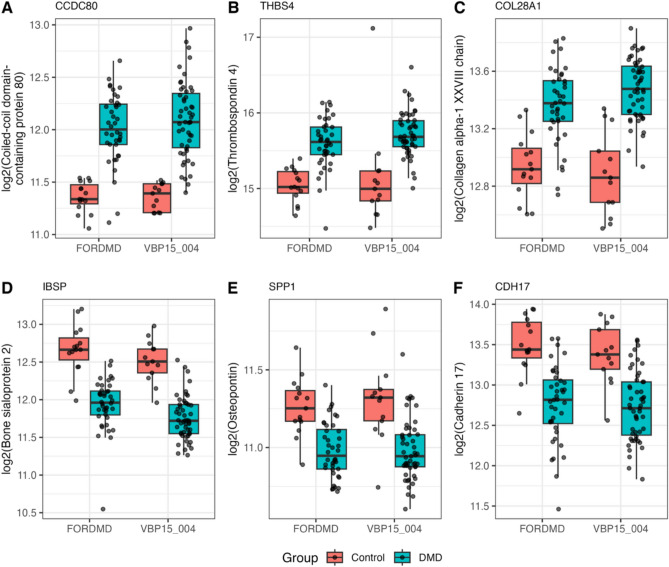

Figure 4 shows examples of increased and decreased extracellular matrix proteins in the serum of DMD subjects relative to controls.

Fig. 4.

Box plots of exemplar ECM protein biomarkers identified in serum of DMD subjects. Levels are shown in both VBP and FORDM cohorts compared to controls. CCDC80: Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 80; THBS4: Thrombospondin-4; COL28A1: Collagen alpha-1(XXVIII) chain; IBSP: Bone sialoprotein 2; SPP1: osteopontin; CDH17: Cadherin-17.

Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 80 (CCDC80), a cell adhesion protein, was found to be elevated by 1.67-fold (adjusted p = 4.06 × 10⁻9) and 1.57-fold (adjusted p = 4.43 × 10⁻9) in the serum of the VISION DMD and FOR DMD cohorts, respectively, compared to the control groups. ADAMTS-like protein 1 (ADAMTSL1) and thrombospondin-4 (THBS4) are two additional examples of ECM remodeling proteins that were found significantly elevated in the serum of DMD subjects compared to controls, with the fold change of + 2.3-fold (adj. p values = 5.1E−15) and + 1.5-fold (adj. p values = 2.09E−5), respectively. These two proteins were also found elevated by 2.15-fold (adj, p value = 6.51E−14) and 1.46-fold (adj p value = 8.6 E−7) respectively in the FOR-DMD cohort. Increased levels of circulating THBS4 were confirmed by both SomaScan and mass spectrometry analysis in previous studies of DMD subjects enrolled through the CINRG-DNHS5,6. Overall, most of the elevated circulating ECM proteins in DMD seem to be involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and signaling. The decreased circulating ECM, on the other hand, consisted mainly of cell-adhesion proteins and cadherins. Figure 4 shows and example for CDH17 that was decreased by 1.65-fold, adj. p value = 3.9E-05), bone sialoprotein 2 (−1.69-fold, adj. p value = 2.96E−11) and SPP1 both decreased by −1.3-fold (adj. p value = 0.001).

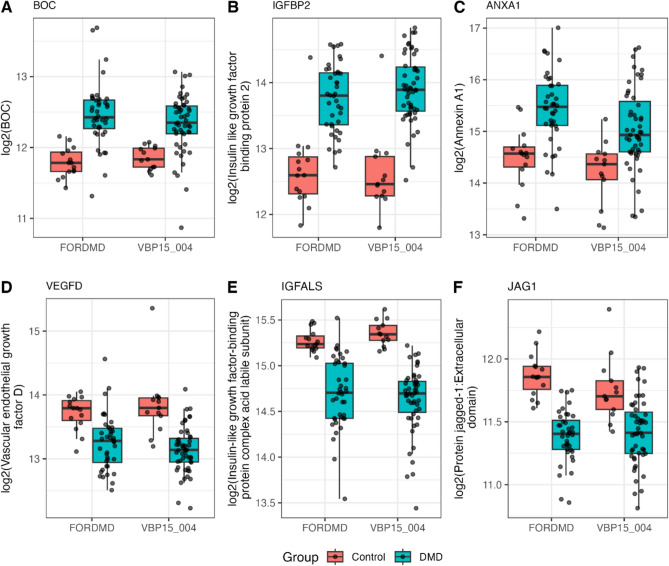

Muscle regeneration biomarkers

Due to the repeated cycles of muscle degeneration and regeneration in young individuals with DMD, several factors involved in myoblast differentiation and muscle development were found to be altered in their levels in the blood of DMD subjects. In total, 38 of such factors were significantly elevated and 29 significantly decreased in the serum of corticosteroid naïve DMD boys compared to age matched healthy controls (see sheet 5 under supplemental Table S1). Figure 5 below shows box plots of some key biomarkers belonging to this category. Insulin like growth factor binding protein 2 (IGFBP-2), annexin-1 (ANXA1) and brother of CDO protein also known as BOC, were found significantly elevated in individuals with DMD compared to controls by a factor of + 2.81-fold (adj. p-value = 2.63E-13), + 1.8-fold (adj. p value = 0.005) and + 1.4 (adj. P value = 0.0004), respectively. On the other hand, insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein complex acid labile subunit (IGFALS), and the extracellular domain of protein jagged-1 (JAG1-ECD) were found significantly decreased in the DMD group compared to the control group by a factor of – 1.8-fold (adj. p-value = 9.9387E-09), - 1.66-fold (adj. p-value = 5.5E-09), and – 1.26-fold (adj. p-value = 0.0003). These candidate circulating biomarkers for muscle regeneration were further confirmed by SomaScan analysis of serum samples of the FOR-DMD cohort.

Fig. 5.

Box plots of exemplar circulating growth factors identified in serum of DMD subjects. Levels are shown in both VBP and FORDM cohorts compared to controls.

Immune and pro-inflammatory associated biomarkers

This group of biomarkers accounted for only 5% of the total serum proteins whose levels were altered in DMD boys compared to controls. They included previously reported chemokines such as CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL13, and CCL18, that have been identified in the serum of young DMD patients compared to healthy controls5,8, as well as newly identified immune-modulating biomarkers. The latter consisted of several soluble receptors for interleukins/cytokines and complement system components.

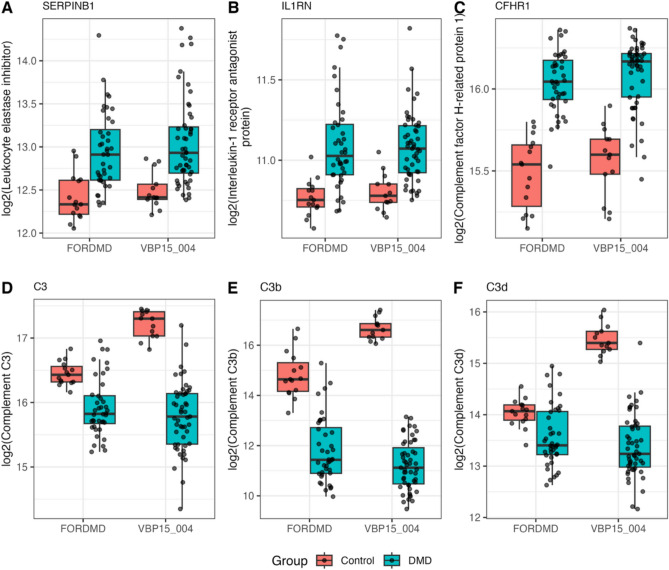

Figure 6 highlights examples such as leukocyte elastase inhibitor (SERPINB1), interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IL1RN), and complement factor H-related protein 1 (CFHR1), which were found to be increased in the DMD group compared to the control group by +1.5-fold (adjusted p-value = 0.0014), +1.2-fold (adjusted p-value = 0.0001), and +1.4-fold (adjusted p-value = 9.8 × 10⁻1⁰), respectively. These changes were consistent across both cohorts. In contrast, complement C3 and its by-products, C3b and C3d, were significantly decreased in the serum of DMD boys from the VISION DMD cohort, by –2.7-fold (adjusted p-value = 5.58 × 10⁻13), –43-fold (adjusted p-value = 1.27 × 10⁻2⁷), and –4.2-fold (adjusted p-value = 1.64 × 10⁻⁹), respectively. However, this dramatic decrease in complement factors was less pronounced in the FOR-DMD cohort (and was not significant for C3d) and was not fully consistent with previously reported data from the CINRG-DNHS cohort5. Nevertheless, a new study on LGMD biomarkers using the same 7k SomaScan platform showed a decrease of circulating C3 in patients compared to controls20.

Fig. 6.

Box plots of exemplar circulating immune and pro-inflammatory associated markers identified in serum of DMD subjects. Levels are shown in both VBP and FORDM cohorts compared to controls.

Although DMD is classified as a chronic inflammatory muscle disease, the circulating pro-inflammatory and immune-associated biomarkers identified here showed only moderate fold changes in DMD serum compared to controls except for complement C3 and its by-products, which were significantly reduced. Further analysis of these complement components using orthogonal methods is warranted to validate these findings.

Comparing circulating biomarker data with existing skeletal muscle mRNA transcriptome and single-cell RNA-seq datasets.

To explore the relationship between dynamic gene expression in skeletal muscle and circulating biomarkers, we compared our key circulating biomarker dataset for DMD to existing skeletal muscle transcriptomic data14,15 and snRNA seq data16. Several muscle injury proteins that were highly elevated, by more than 10-fold, in the blood circulation of young boys with DMD showed slight alterations to no change in their mRNA expression levels within skeletal muscle. For example, as shown in Table 2., muscle injury biomarkers such as TNNI2, ACTN2, MYOM2, CA3, and MYL3 exhibited significantly elevated circulating levels more than 40-fold higher in DMD patients compared to controls. However, the expression of the corresponding genes in skeletal muscle was only moderately decreased (no more than 1.5-fold) in young DMD patients. Notably, two additional skeletal muscle specific biomarkers, TNNT2 and myosin-binding protein H (MYBPH), showed both elevated circulating levels (over 10-fold) and increased mRNA expression in skeletal muscle (approximately 3 to 8-fold) in DMD individuals compared to controls. The increased expression of TNNT2 and MYBPH was mostly associated with regenerative fibers, as demonstrated by snRNAseq data16.

Table 2.

List of candidate serum protein biomarkers for DMD and their corresponding mRNA expression levels* in DMD muscle tissue compared to controls.

| Target | Protein fold-change in serum (DMD/Cnt) | mRNA fold-change in muscle (DMD/Cnt) | snRNAseq muscle tissue | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VBP15 | FORDMD | Bakay et al., 2006 | Pescatori et al., 2007 | Suárez-Calvet et al., 2023 | ||

| Muscle specific biomarkers | MYBPH | 13.1 | 22.6 | 8.0 | 4.1 | 5.02 (regenerative fiber) |

| TNNT2 | 14.6 | 16.0 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 8.95 (regenerative fiber) | |

| MYOM2 | 80.2 | 70.0 | −1.36 | −1.36 | 2.66 (fast and slow fibers) | |

| ACTN2 | 151.4 | 202.6 | −1.26 | −1.6 | 1.5 (fast and slow fibers) | |

| TNNI2 | 50.54 | 48 | −1.43 | −1.25 | 2.12 (fast fibers) | |

| CA3 | 50.88 | 54.59 | 1.38 | −1.03 | 2.31 (slow fibers) | |

| MYL3 | 44.28 | 66.09 | −1.2 | −1.4 | −0.91 (slow fibers) | |

| Extracellular matrix remodeling | LUM | 1.1 | 1.2 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 1.25 (FAP cells) |

| COL6A3 | 1.47 | 1.37 | 4.5 | 2.6 | 3.08 (FAP cells) | |

| THBS4 | 1.51 | 1.46 | 2.4 | 2.26 | 0.81 (FAP and SMC cells) | |

| ADAM12 | 1.24 | 1.21 | 1.22 | 1.06 | 6.85 (FAP cells) | |

| CCDC80 | 1.67 | 1.57 | Nd | nd | 4.97 (FAP cells) | |

| Growth factors and muscle regeneration factors | SPP1 | −1.3 | −1.2 | 15.1 | 3.5 | trace |

| IGF1 | −1.13 | −1.12 | 3.2 | 1.67 | 1.69 (slow fibers and FAP) | |

| IGF2 | −1.64 | −1.24 | 4.6 | 1.84 | 8.94 (FAPs cells) | |

| IGFBP3 | −1.41 | −1.26 | 5.6 | 1.46 | 3.59 (FAP cells) | |

| VEGFD | −1.63 | −1.38 | −1.8 | −1.23 | −1.79 (fast and slow fibers) | |

| ANXA1 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 1.2 (FAP cells) | |

| Immune modulators | CXCL10 | 1.52 | 1.29 | 1.3 | 1.20 | trace |

| CXCL11 | 1.65 | 1.7 | 1.16 | 1.09 | trace | |

| IL1RN | 1.21 | 1.26 | 1.22 | −1.00 | trace | |

| SERPINB1 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 1.5 | 1.45 | 1.1 (Slow and fast fibers) | |

| C3 | −2.7 | −1.4 | 7.5 | 3.7 | 14.1 (FAP cells) | |

| Others | ART3 | −2.2 | −2.5 | −4.6 | −2.3 | −0.9 (Slow and fast fibers) |

| GSN | −1.4 | −1.3 | 2.2 | 1.19 | 2.4 (FAP and SMC cells) | |

| NNMT | 3.88 | 6.2 | 11.8 | 3.65 | −0.5 (Slow fibers) | |

| PENK | 5.81 | 4.66 | 3.0 | 2.7 | trace | |

* Note that many targets had multiple probes; we focused on the same probes across datasets, prioritizing the “_at” probe.

nd: not determined.

Interestingly, several factors involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and muscle regeneration were significantly increased in skeletal muscle, although their levels in serum were only moderately altered in DMD compared to controls. For example, certain ECM remodeling proteins such as lumican (LUM), collagens (COL1A and COL6A3), ADAM12, CCDC80 as well as growth regulating factors such as SSP1, IGF1, IGF2, IGFBP3, ANXA1 while moderately altered in their circulating levels, their expression in skeletal muscle at the mRNA levels were significantly increased in DMD compared to controls. Interestingly, most of these ECM remodeling proteins and growth regulating factors were found expressed by fibro-adipogenic progenitor (FAP) cells according to a recent study16.

Pro-inflammatory and immune-modulatory markers such as CXCL10, CXCL11, SERPINB1, and C3 were moderately elevated in both the circulation and muscle tissue. However, C3 serum levels were significantly decreased in DMD compared to controls, despite a significant increase in its mRNA expression in skeletal muscle. This localized expression of C3 was primarily derived from FAP cells, suggesting a potential role for the FAP and complement pathway in DMD pathogenesis.

Another group of proteins of interest included those that were elevated and/or decreased in both the blood circulation and skeletal muscle of young DMD boys compared to controls. For example, nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT) and proenkephalin-A (PENK) were both found to be significantly elevated in the circulation at the protein levels and at the mRNA levels in the skeletal muscle of young boys with DMD compared to healthy controls14,15. Conversely, Ecto-ADP-ribosyltransferase 3 (ART3), also known as NAR3, was significantly decreased in the serum and skeletal muscle of young boys with DMD compared to healthy controls. This same protein was also found to be significantly decreased in the serum of subjects with LGMD compared to controls20.

Discussion

In this study, we conducted an in-depth aptamer-based assay study using a case-control design to measure levels of 7,289 circulating proteins in serum samples of glucocorticoid naïve subjects with DMD and age matched healthy volunteers. The use of serum samples from untreated DMD subjects enabled the identification of various biomarkers associated with the cascade of events triggered by the absence of dystrophin, leading to muscle damage, inflammation, regeneration, and fibrosis. This comprehensive catalogue of biomarkers offers a valuable resource for selecting candidates in future context-of-use studies. To minimize confounding variables such as corticosteroid use and age, we analyzed baseline serum samples from untreated subjects with DMD within a narrower age range (4–8 years). Overall, 1,881 proteins were significantly increased, while 1,086 were significantly decreased in the DMD group compared to healthy controls.

This large-scale analysis confirmed previously reported biomarkers and expanded the catalog of candidate biomarkers for DMD. As expected, the extensive muscle damage and regeneration occurring in young boys with DMD led to a marked elevation of muscle-specific proteins in their blood circulation. These muscle damage-associated biomarkers included sarcomere components, enzymes, and mitochondrial proteins. In addition to previously reported muscle injury proteins such as CK-M, CA3, MB, TNNI2, MYOM3, MYPC1, ALDOA, and FABP3, we identified additional muscle specific proteins that were found highly elevated in the blood of young DMD boys compared to controls. Just to name a few, these included ACTN2, MYOM2, titin fragment, OXCT1, CAPN3, Myosin regulatory light chain 2 (MYL11), KLHL41, TRIM72, and several mitochondria-associated proteins such as OXCT1, Enoyl-CoA delta isomerase 1, Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, and many others. The increase in these proteins ranged from a modest two-fold to over 150-fold, depending on their relative abundance in skeletal muscle. Interestingly, although these muscle-specific proteins were highly elevated in the serum of young boys with DMD, their corresponding mRNA expression levels in specific cells types in skeletal muscle based on published snRNAseq data were only moderately decreased or remained unchanged in comparison to healthy controls. An exception was the cardiac-specific TNNT2 and MYBPH, which were significantly elevated at both the protein level in circulation and the mRNA level in muscle tissue. This finding aligns with a previous study by du Fay de Lavallaz et al.21, demonstrating that circulating TNNT2 levels in individuals with skeletal muscle disorders originate from skeletal muscle rather than the heart per se. Furthermore, a recent study showed that TNNT2 mRNA expression was higher in DMD compared to BMD, suggesting a link to regenerating fibers22 and in agreement with snRNAseq data showing that TNNT2 is indeed expressed in regenerating fibers16. Similarly, MYBPH, which was found to be elevated in both serum and skeletal muscle, was reported to be involved in the fast-twitch skeletal muscle development23 and is also expressed in regenerating fibers16. Interestingly, these same muscle injury biomarkers including the two muscle regeneration biomarkers TNNT2 and MYBPH were also found highly elevated in the serum of subjects affected with Limb girdle muscular dystrophy compared to age/gender matched controls20.

The repeated cycles of muscle degeneration and regeneration that occur in young DMD boys are reflected not only in the levels of circulating muscle injury proteins but also in the altered circulating levels of various ECM remodeling proteins and proteases, resulting in both increases and decreases in specific circulating ECM proteins. Examples of elevated ECM circulating proteins included PCDH1, LUM, COL28A1, COL6A3, ADAM12, ADAMTSL1, and THBS4. Notably, transcriptomic analysis revealed that LUM and COL6A3 mRNA levels significantly increased in skeletal muscle of young DMD boys compared to controls14,15 with ADAM12 and ADAMTSL1 specifically expressed by FAPs cells according to recent RNAseq analysis of DMD muscle tissue16. Interestingly, some of the circulating ECM proteins, such as COL28A1 and PCDH1, that were found to be elevated in DMD patients compared to controls have also been reported to be elevated in the serum of LGMD subjects relative to age/gender matched healthy controls, further linking these two biomarkers to muscle pathogenesis20.

In contrast to the elevated levels of circulating matricellular proteins observed in DMD, several extracellular matrix (ECM)-associated proteins, such as cadherins (CADH3, CADH5, CADH11, and CADH17), bone sialoprotein 2 (BSP), and collagen alpha-1(X) chain (COL10A1), were found to be decreased in the serum of DMD subjects compared to healthy controls. Cadherins, like other cell adhesion proteins, play a critical role in maintaining the structural integrity of the ECM surrounding muscle fibers24. In DMD, the absence of dystrophin disrupts the connection between the sarcolemma and ECM, leading to ECM degradation that parallels muscle fiber breakdown. This may partly account for the reduced circulating levels of some adhesion molecules. Interestingly, the mRNA expression of certain cadherins, including CADH5 and CADH11, was found to be elevated in dystrophin-deficient muscle relative to healthy tissue14,15. CADH11 has been shown to promote muscle differentiation in vitro25, however, the role of CADH5 and CADH11 in muscle regeneration in vivo remains to be fully elucidated.

Effective muscle regeneration is crucial for maintaining muscle mass in young boys with DMD during the early stages of the disease when muscle tissue retains a relatively high regenerative capacity. Consequently, many circulating biomarkers involved in activation of satellite cells, myoblast differentiation, and muscle development are expected to show altered circulating levels, as well as changes in their expression within skeletal muscle tissue. Indeed, several growth factor ligands (IGF-I, IGF-II), their IGF-binding proteins, known to regulate muscle growth26, showed altered circulating levels and expression levels in muscle. IGF-I and IGF-II were both found to be decreased in serum samples of DMD relative to controls, but their mRNA expression levels, at least for IGF-I were reported to be increased by 1.6 to 3.2-fold in the muscle of young DMD boys compared to controls14,15. Similarly, IGFBP-3, a known positive regulator of IGF-1 activity27, was found to follow the same trend as IGF-I. It decreased in serum, but its mRNA expression level was reported to be significantly elevated in the muscle of DMD boys relative to controls14,15. Overall, the IGFs and their IGFBP regulators are believed to play a central role in muscle regeneration and development28,29. Similarly, myostatin (GDF8) and activin-A, well-known negative regulators of muscle growth30–32, were found to be decreased by 20% and 40%, respectively, in the serum of boys with DMD compared to controls. Both myostatin and activin-A are secreted by brown adipose tissue and play key roles in regulating muscle mass. Their reduced levels in the circulation of DMD boys may represent a compensatory mechanism to support the muscle regeneration observed in younger patients. Interestingly, an earlier study demonstrated that activin-A is a more potent regulator of muscle mass in primates than myostatin33.

Additional newly identified potential muscle regulatory factors with altered serum levels in boys with DMD compared to healthy controls include Sonic Hedgehog protein (SHH)34, ADAM1235, galectin-1 and galectin-related protein36, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)37, and several fibroblast growth factors and their soluble receptors38. Interestingly, VEGF-D was decreased in DMD compared to controls at the protein levels in serum as well as at the mRNA levels in muscle tissue14–16. VEGF-D, a vascular growth promoting factor, has been shown to promote angiogenesis and improve regeneration of skeletal muscle in the mdx mouse model39. Although previously published reports linked some of these factors to muscle regeneration, further studies clarifying which cells express these factors in muscle tissue and their precise role in muscle regeneration may prove valuable to better understand the muscle pathogenesis in DMD and develop better therapeutic strategies. Longitudinal studies tracking these muscle regenerative factors in both DMD and healthy individuals are another way to elucidate their roles in muscle development and disease monitoring.

It is well known that the regenerative capacity of the muscle is decreased over time in DMD for multiple, not yet confirmed in some cases, reasons such as exhaustion of the satellite cell pool, progressive decrease in the number of muscle fibers, persistence of an inflammatory and profibrotic muscle niche, and progressive expansion of the fibro-adipogenous tissue. All these factors influence muscle regeneration negatively and could explain the pathophysiology of DMD disease progression.

Similarly, inflammatory factors are commonly seen in early to moderate stages of the disease, when prominent inflammatory molecules drive the pro-regenerative response observed in muscles. Presence of inflammatory cells in the skeletal muscle of DMD subjects is a constant, explaining the presence of some of these molecules in the blood circulation; however, these molecules are not always released by inflammatory cells and reflect an inflammatory status present in the muscle degenerative niche. In this large-scale biomarker discovery study, we have confirmed previously identified pro-inflammatory markers such chemokines (e.g., CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL13, CCL18), soluble advanced glycosylation end product-specific receptor also known as sRAGE and plasminogen5 but also identified a decrease in the circulating levels of MIF, IL36A, IL31, complement C3 and its byproducts, C4b, C3b, C3d and an increase in some soluble interleukin receptors (IL17RB, IL1RL1, IL12RB2), soluble cytokine receptor common subunit gamma, CRP, fibrinogen-like protein 1 and leukocyte elastase inhibitor. While the exact role of these immune modulating factors in muscle degeneration and regeneration factors is not well established, recent reports are pointing to the role of interleukin pathways, especially the IL-17 pathway, in muscle regeneration in dystrophinopathies22,40. The increase and decrease in circulating levels of these immune modulating factors remain complex. Perhaps, undergoing single cell or single nuclei RNAseq analyses of DMD muscle tissue compared to control will help identify what type of cells are contributing to the expression of these factors detected in the blood circulation of DMD at an early stage of the disease.

Recent studies using single cell or single nuclei RNAseq analyses on muscle tissues from DMD and healthy control subjects16,41 showed that many of the circulating biomarkers identified in this study originated by other cells beside muscle fibers. These include immune cells, FAPs cells but also endothelial cells and adipocytes. Further studies linking circulating DMD biomarkers to snRNAseq data from the same subjects might provide further insights into DMD pathogenesis and eventually help develop better combination therapeutic targets to preserve skeletal muscle health in boys with DMD and other muscle diseases.

Our study has several key strengths: large sample sizes across two independent cohorts and the first use of high-quality, pre-treatment biosamples (without multiple freeze-thaw cycles) from large-scale, regulator-audited clinical trials. The trials enrolled patients within a narrow age range (4 to <8 years) and we employed the high-throughput SomaScan assay (v4.1), which can quantify up to 7,289 protein targets.

Although our study presents a comprehensive serum protein biomarker discovery using the highly multiplexed SomaScan assay, which measures up to 7,289 proteins in serum samples from untreated DMD subjects across two well-controlled cohorts, several limitations should be acknowledged, along with future directions. Limitations of our approach include the smaller number of proteins currently validated by orthogonal methods, and the lack of longitudinal follow-up in treatment-naïve patients. A limitation is also the imbalance in sample sizes between the DMD and control cohorts, as well as a slight age difference between the groups. This reflects the inherent challenges in recruiting unaffected participants for DMD and other pediatric studies. To address these issues, we employed linear models fitted via an empirical Bayes–based moderated test approach, which enhances the reproducibility of differential expression analysis, particularly in studies with small sample sizes. Although imbalance in comparison groups can be problematic in small datasets, especially when outliers are present, the empirical Bayes approach mitigates this by using moderated variances rather than standard t-tests or Mann–Whitney tests. Additionally, our discovery/validation cohort design allows comparison of signal directionality and associations across cohorts. While subtle confounding from age and cohort sourcing cannot be entirely excluded, the consistency of findings across both discovery and validation datasets supports the robustness of our data (Figure 2 shows Pearson and Spearman correlations of biomarker data between the two independent cohorts). Only a few biomarkers showed inconsistent directionality between cohorts.

The majority of significantly altered biomarkers (93%) showed concordant directionality across cohorts. However, some biomarkers, particularly complement components, showed discrepancies in fold change between cohorts. The decrease in complement C3 and its by-products (C3b, C3d) in DMD relative to healthy controls was more pronounced in the VISION DMD cohort than in the FOR-DMD cohort and did not align with previously reported data from the CINRG-DNHS cohort42. Several factors may contribute to these inconsistencies. Complement components are inherently challenging to measure due to their ex vivo self-activation. Long- versus short-term serum storage can also influence complement activation, even at –80°C43,44. The VISION-DMD cohort samples were stored for between 2 and 5 years, whereas the FOR-DMD and CINRG cohort samples were stored in aliquots at –80°C between 5 and 10 years (FOR-DMD) or longer (CINRG). However, we are encouraged by the fact that the C3, iC3b, C3d, C3b, and C3adesArg aptamers all showed significant, negative fold directionality in both the VISION DMD cohort and the FORDMD cohort. The much smaller sample size and non-clinical trial CINRG-DNHS cohort-based finding was likely false. Nevertheless, additional measurements using orthogonal methods and independent cohorts are needed to confirm the decrease of C3 and its by-products in DMD relative to controls. In this context, a decrease in circulating C3 and its by-product was also observed in Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy compared with controls, using the same aptamer ID on the SomaScan platform, suggesting a link to muscle pathogenesis. Finally, this study does not correlate circulating protein biomarkers with clinical data. A follow-up study using longitudinal samples is in progress to assess the relationship between biomarker trajectories and clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

By eliminating confounding factors such as glucocorticoid treatment and age, using highly multiplexing serum proteome profiling technique, in combination with a discovery-validation approach, we identified a comprehensive list of serum protein biomarkers associated with early-stage muscle pathogenesis in DMD. These included biomarkers associated with muscle injury, inflammation, muscle regeneration and extracellular matrix remodeling. One of our goals is to identify biomarkers beyond the muscle-specific ones typically associated with muscle fibers leakage, a hallmark pathogenesis of DMD. In this study, we uncovered a broad spectrum of ECM proteins and growth factors, highlighting their potential contribution to the pathological remodeling processes that underlie DMD pathogenesis. These biomarkers could be further evaluated for clinical utility in longitudinal studies and assessed in clinical trials, with a fit-for-purpose approach aimed at improving trial design and supporting the discovery of novel therapeutic targets.

Materials and methods

Study participants and serum collection

Pre-treatment baseline serum samples used in this biomarker study were obtained de-identified from two previously approved clinical trials: the Phase 2b vamorolone trial (VBP15-004, VISION-DMD cohort)17,18 involving participants aged 4 to <7 years (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03439670; registration date: February 20, 2018), and the FOR-DMD trial (Finding the Optimum Regimen of Corticosteroids for DMD), which included participants aged 4 to <8 years (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01603407; registration date: May 23, 2012)19. De-identified serum samples from healthy volunteers were obtained through the Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group–Duchenne Natural History Study (CINRG-DNHS) (ClinicalTrails.gov: NCT00468832, registration date: May 03, 2007)45.

This biomarker study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Binghamton University (Protocol Number: class=“convertEndash” ID=“EN2”> class=“convertEndash” ID=“EN3”>4049-16). Informed written consent for participation in biomarker research was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of participants at the time of enrollment in each clinical study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations to protect human subjects and to ensure that participants remained de-identified during sample analysis and data reporting. Serum samples were processed from collected blood using standardized procedures and stored in aliquots in polypropylene cryogenic vials (Thermo Scientific) at −80 °C for subsequent biomarker analysis.

The discovery cohort consisted of a subset of 51 pre-treatment (baseline) serum samples obtained from the VBP15-004 trial (VISION DMD cohort) along with age-matched 13 healthy controls from CINRG DNHS. The validation cohort consisted of baseline serum samples from the FOR-DMD consisting of 40 pre-treatment samples matched along with 15 healthy controls from CINRG DNHS.

Serum proteome profiling using SomaScan technology

Aliquots of 130 µL from each serum sample were shipped frozen on dry ice for global proteome profiling using the Somascan aptamer assay (Somalogic Inc., Boulder, CO). For the assay, 65 µL were used from each aliquot and the remaining were stored as backup. This technology was first introduced by Gold et al.46, then further developed to measure levels of thousands of proteins in 65 µL of serum/plasma samples. In this study, we used the 7 K v4.1 SomaScan® platform, which targets 7,289 distinct protein targets/analytes, as the current 11 K version was unavailable at that time. The assay uses SOMAmer (Slow Off-rate Modified Aptamer) reagents to bind with high specificity to unique proteins in serum. Each aptamer is tagged with a unique short DNA sequence that is subsequently used to determine the relative amount of target protein using DNA microarrays. The level of each protein is recorded as relative fluorescence units (RFU) from microarrays. All arrays were done using a dilution series of each serum sample so that the signal/noise ratio of each aptamer/protein pair was optimized.

The raw data was processed by Somalogic according to a standardized pipeline involving the following steps: use of hybridization controls, median signal normalized across pooled calibrator replicates, plate scale adjustments, and a calibration scale to ensure that the data is standardized and comparable across different experiments The data was then made accessible to us for further statistical analysis as described below.

The serum protein data from the discovery cohort (vamorolone VISION DMD trial) were obtained in two stages: the first stage focused on a custom panel of 1,500 biomarkers, selected based on an extensive literature review and DMD expert opinion. This targeted approach allowed us to concentrate our resources on proteins with the highest relevance and potential impact on our study. Upon successful data generation and analysis of the first stage with identification of previously undefined DMD-specific proteins, we proceeded to the second stage, where we extended our analysis to the remaining 5,788 biomarkers on the 7 K platform. While we obtained and analyzed the data in two stages (given costs and different rounds of funding), data generation on all 7,289 human protein targets was done together. A data mask was used by Somalogic to provide us with data in two stages. Herein, we report our analyses on all 7,289 targets. For validation using FOR-DMD samples, only a 1,500-panel dataset was obtained.

Muscle biopsy data comparison

Raw datasets were downloaded for previously published data on DMD boys in a young age range (0 to 2 years old14,15, and 5 to 9 years old14,15) with limma used to compare between DMD and unaffected biopsies, with normalization and pre-filtering (removing low intensity and low variance probes) as needed and a focus on non-experimental probes.

Statistical methods

Samples with flagged values by Somalogic were excluded. Data were log2-transformed to address skewness and obtain distributions better suited for analyses assumptions. Linear models were fitted using the empirical Bayes based moderated test approach from the limma47 package in R statistical software to compare mean biomarker levels between DMD patients and healthy controls. Differentially expressed biomarkers were defined based on false discovery rate adjusted p-values (alpha*=0.05 in each of the two stages of analysis). A correlation-based cluster analysis was used to study biomarker-biomarker associations48. Pathway analysis description (g:profiler using Gene Ontology) was also carried out.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and their families for participating in the research studies, as well as the study coordinators of VBP15-004, FOR-DMD, and CINRG DNHS studies, clinical evaluators, and TRiNDS.

Author contributions

F.A. performed the statistical analysis, generated figures, and outlined the first draft. R.T., C.D., and A.N. organized the biomarker data and provided input on data interpretation. M.G. collected FOR-DMD subject demographics and serum samples for biomarker analysis and also contributed to data interpretation. A.J.-R. and S. de-V. contributed to data interpretation and discussion. R.T. assisted with statistical analysis. C.A., P.S., Y.V., and J.D. contributed to the experimental design and data interpretation. E.H., P.C., and the CINRG DNHS investigators contributed to serum sample collection, data interpretation, and manuscript revision. FOR-DMD investigators of the Muscle Study Group contributed to serum collection and manuscript revisions. U.J.D. contributed to statistical analysis, methods section writing, data organization, and figure production. Y.H. organized the overall study, performed the literature search, and wrote the first draft of the article.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Foundation to Eradicate Duchenne (Dang) as well as the NIH NINDS (R61NS119639; Hathout, Dang) and Department of Defense (Hoffman) and ReveraGen Biopharma (Hoffman).

Data availability

All biomarker data related to this article are provided in Supplementary Table SI. Raw data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

UJD has served as an ad-hoc consultant for ReveraGen Biopharma in the past.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

List of authors and their affiliations appear at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Yetrib Hathout, Email: yhathout@binghamton.edu.

VBP15-004 investigators, CINRG DNHS investigators:

Michela Guglieri, Jesse M. Damsker, Seth J. Perlman, Edward C. Smith, Iain Horrocks, Richard S. Finkel, Jean K. Mah, Nicolas Deconinck, Nathalie M. Goemans, Jana Haberlová, Volker Straub, Laurel Mengle-Gaw, Benjamin D. Schwartz, Amy Harper, Perry B. Shieh, Liesbeth De Waele, Diana Castro, Michele L. Yang, Monique M. Ryan, Craig M. McDonald, Erik K. Henricson, Erica Goude, Mar Tulinius, Richard I. Webster, Hugh J. Mcmillan, Nancy Kuntz, Vamshi K. Rao, Giovanni Baranello, Stefan Spinty, Anne-Marie Childs, Annie M. Sbrocchi, Kathryn A. Selby, Migvis Monduy, Yoram Nevo, Juan J. Vilchez, Andres Nascimento-Osorio, Erik H. Niks, Imelda JM De Groot, Marina Katsalouli, John N. Van DenAnker, Leanne M. Ward, Mika Leinonen, Tina Duong, Carolina Tesi Rocha, Mathula Thangarajh, MD Andrea L. D’Alessandro, Lauren P. Morgenroth, Paula R. Clemens, and Eric P. Hoffman

References

- 1.Topol, E. J. The revolution in high-throughput proteomics and AI. Science (1979)385, eads5749 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutsch, E. W. et al. Advances and utility of the human plasma proteome. J. Proteom. Res.20, 5241–5263 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bader, J. M., Albrecht, V. & Mann, M. MS-based proteomics of body fluids: The end of the beginning. Mol. Cell. Proteom.22, 100577 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spitali, P. et al. Tracking disease progression non-invasively in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. J. Cachex. Sarcopenia Muscle9, 715–726 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hathout, Y. et al. Large-scale serum protein biomarker discovery in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci.112, 7153–7158 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alayi, T. D. et al. Tandem mass tag-based serum proteome profiling for biomarker discovery in young duchenne muscular dystrophy boys. ACS Omega5, 26504–26517 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikelaar, N. A. et al. Large scale serum proteomics identifies proteins associated with performance decline and clinical milestones in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Preprint at 10.1101/2024.08.05.24311516 (2024).

- 8.Ogundele, M. et al. Validation of chemokine biomarkers in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Life11, 827 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson, C. et al. Orthogonal proteomics methods warrant the development of Duchenne muscular dystrophy biomarkers. Clin. Proteom.20, 23 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strandberg, K. et al. Blood-derived biomarkers correlate with clinical progression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Neuromuscul. Dis.7, 231–246 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Signorelli, M. et al. Longitudinal serum biomarker screening identifies malate dehydrogenase 2 as candidate prognostic biomarker for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Cachex. Sarcopenia Muscle11, 505–517 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehler, J. F., Brown, K. J., Ricotti, V. & Morris, C. A. N-terminal titin fragment: A non-invasive, pharmacodynamic biomarker for microdystrophin efficacy. Skelet. Muscle14, 2 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komaki, H. et al. Phase 1/2 trial of brogidirsen: Dual-targeting antisense oligonucleotides for exon 44 skipping in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Rep. Med.6, 101901 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakay, M. et al. Nuclear envelope dystrophies show a transcriptional fingerprint suggesting disruption of Rb–MyoD pathways in muscle regeneration. Brain129, 996–1013 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pescatori, M. et al. Gene expression profiling in the early phases of DMD: A constant molecular signature characterizes DMD muscle from early postnatal life throughout disease progression. FASEB J.21, 1210–1226 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suárez-Calvet, X. et al. Decoding the transcriptome of Duchenne muscular dystrophy to the single nuclei level reveals clinical-genetic correlations. Cell Death Dis.14, 596 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guglieri, M. et al. Efficacy and safety of vamorolone vs placebo and prednisone among boys with Duchenne muscular Dystrophy. JAMA Neurol.79, 1005 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dang, U. J. et al. Efficacy and safety of vamorolone over 48 weeks in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology102, e208112 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guglieri, M. et al. Effect of different corticosteroid dosing regimens on clinical outcomes in boys with Duchenne muscular Dystrophy. JAMA327, 1456 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis, A. B. et al. Serum protein and imaging biomarkers after intermittent steroid treatment in muscular dystrophy. Sci. Rep.14, 28745 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de du Fay Lavallaz, J. et al. Skeletal muscle disorders: A noncardiac source of cardiac troponin T. Circulation145(1764), 1779 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, C. et al. Interleukin-17B is a new biomarker of human muscle regeneration in dystrophinopathies. Brain10.1093/brain/awaf058 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mead, A. F. et al. Functional role of myosin-binding protein H in thick filaments of developing vertebrate fast-twitch skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol.156, e20241360 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purslow, P. P. The structure and functional significance of variations in the connective tissue within muscle. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol.133, 947–966 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redfield, A., Nieman, M. T. & Knudsen, K. A. Cadherins promote skeletal muscle differentiation in three-dimensional cultures. J. Cell Biol.138, 1323–1331 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duan, C., Ren, H. & Gao, S. Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), IGF receptors, and IGF-binding proteins: Roles in skeletal muscle growth and differentiation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.167, 344–351 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranke, M. B. Insulin-like growth factor binding-protein-3 (IGFBP–3). Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.29, 701–711 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton, E. R., Morris, L., Musaro, A., Rosenthal, N. & Sweeney, H. L. Muscle-specific expression of insulin-like growth factor I counters muscle decline in mdx mice. J. Cell Biol.157, 137–148 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bella, P. et al. Blockade of IGF2R improves muscle regeneration and ameliorates Duchenne muscular dystrophy. EMBO Mol. Med.12, e11019 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langley, B. et al. Myostatin inhibits myoblast differentiation by down-regulating MyoD expression. J. Biol. Chem.277, 49831–49840 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baig, M. H. et al. Myostatin and its regulation: A comprehensive review of myostatin inhibiting strategies. Front. Physiol.13, 876078 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez Trotter, D. et al. GDF8 and activin A are the key negative regulators of muscle mass in postmenopausal females: A randomized phase I trial. Nat. Commun.16, 4376 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Latres, E. et al. Activin a more prominently regulates muscle mass in primates than does GDF8. Nat. Commun.8, 15153 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madhala-Levy, D., Williams, V. C., Hughes, S. M., Reshef, R. & Halevy, O. Cooperation between Shh and IGF-I in promoting myogenic proliferation and differentiation via the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways requires smo activity. J. Cell Physiol.227, 1455–1464 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galliano, M.-F. et al. Binding of ADAM12, a marker of skeletal muscle regeneration, to the muscle-specific actin-binding protein, α-actinin-2, is required for myoblast fusion. J. Biol. Chem.275, 13933–13939 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Georgiadis, V. et al. Lack of galectin-1 results in defects in myoblast fusion and muscle regeneration. Develop. Dyn.236, 1014–1024 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller, K. J., Thaloor, D., Matteson, S. & Pavlath, G. K. Hepatocyte growth factor affects satellite cell activation and differentiation in regenerating skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol.278, C174–C181 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Templeton, T. J. & Hauschka, S. D. FGF-mediated aspects of skeletal muscle growth and differentiation are controlled by a high affinity receptor, FGFR1. Dev. Biol.154, 169–181 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Messina, S. et al. VEGF overexpression via adeno-associated virus gene transfer promotes skeletal muscle regeneration and enhances muscle function in mdx mice. FASEB J.21, 3737–3746 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mann, A. O. et al. IL-17A–producing γδT cells promote muscle regeneration in a microbiota-dependent manner. J. Exp. Med.219, e 20211504 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernández-Simón, E. et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of human FAPs reveals different functional stages in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.12, 1399319 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hathout, Y. et al. Disease-specific and glucocorticoid-responsive serum biomarkers for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Sci. Rep.9, 12167 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan, A. R., O’Hagan, C., Touchard, S., Lovestone, S. & Morgan, B. P. Effects of freezer storage time on levels of complement biomarkers. BMC Res. Note.10, 559 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frazer-Abel, A., Kirschfink, M. & Prohászka, Z. Expanding horizons in complement analysis and quality control. Front. Immunol.12, 697313 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonald, C. M. et al. The cooperative international neuromuscular research group Duchenne natural history study-a longitudinal investigation in the era of glucocorticoid therapy: Design of protocol and the methods used. Muscle Nerve48, 32–54 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gold, L. et al. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS ONE5, e15004 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucl. Acid. Res.43, e47–e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform.9, 559 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All biomarker data related to this article are provided in Supplementary Table SI. Raw data is available upon request from the corresponding author.