Abstract

Antiviral susceptibility monitoring is integral to influenza surveillance conducted by CDC in collaboration with partners. Here, we outlined the algorithm and methods used for assessing antiviral susceptibility of viruses collected during 2023–2024 season. Virus specimens were provided by public health laboratories in the United States (US) and by laboratories in other countries that belong to the Pan American Health Organization. In the US, antiviral susceptibility surveillance conducted nationally is strengthened by sequence-only analysis of additional viruses collected at a state level. Viral genome sequence analysis was the primary approach to assess susceptibility to M2 blockers (n = 5123), neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors (n = 6874), and a polymerase acidic protein (PA) inhibitor (baloxavir, n = 6567). Over 99 % of type A viruses had M2-S31N that confers resistance to M2 blockers. Although oseltamivir-resistant viruses carrying NA-H275Y (N1 numbering) were rare (0.35 %), a cluster of four such viruses was identified in Haiti. Viruses with other NA mutations conferring reduced inhibition by NA inhibitor(s) were also detected sporadically. This includes a cluster of three influenza B viruses in Texas that shared a new mutation, NA-A245G conferring reduced inhibition by peramivir. Three viruses with reduced baloxavir susceptibility were identified, which had PA-I38T, PA-Y24C or PA-V122A; the latter two new mutations identified through augmented approach to sequence analysis. To monitor baseline susceptibility, supplementary in vitro testing was conducted on approximately 7 % of viruses using NA inhibition assay and cell culture-based assay IRINA. Implementation of Sequence First approach provided comprehensive and high throughput methodology for antiviral susceptibility assessment and reduced redundant phenotypic testing.

Keywords: Antiviral resistance, IRINA, Baloxavir, Neuraminidase inhibitor, Oseltamivir, Reduced susceptibility, Influenza, NGS, Peramivir

1. Introduction

Vaccines and antiviral medications are needed to prevent and treat human infections caused by seasonal and pandemic influenza viruses (Krammer et al., 2018; Paules and Subbarao, 2017). Antivirals from three classes, M2 blockers, neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir), and polymerase acidic cap dependent endonuclease (PA CEN) inhibitor (baloxavir) are approved in the US by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (https://www.cdc.gov/flu/treatment/antiviral-drugs.html). Notably, mutations occurring in circulating viruses can diminish the usefulness of antivirals. Since 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend the use of M2 blockers because most seasonal influenza A viruses acquired M2-S31N, an amino acid substitution that confers cross-resistance to amantadine and rimantadine (CDC, 2006). During 2007–2009, many A (H1N1) viruses in circulation carried NA-H275Y, a marker of resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir (Meijer et al., 2009). Those A (H1N1) viruses were replaced by 2009 pandemic viruses (A (H1N1)pdm09 hereafter) that lacked NA-H275Y but carried M2-S31N (Garten et al., 2009). Globally, oseltamivir-resistant A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses were periodically detected in several countries during the years after the pandemic, but their frequency remained low (CDC, 2009; Hurt et al., 2012; Takashita et al., 2024). Besides NA-H275Y, many other changes within or near the NA enzyme active site have been suspected to reduce susceptibility to oseltamivir and/or other NA inhibitors (Govorkova et al., 2022; Yen, 2016). The effect of these NA changes on enzyme-drug interactions are often type-, subtype-, and antiviral-specific. In 2018, PA inhibitor baloxavir was approved in Japan and US and then marketed in many countries worldwide (Beigel and Hayden, 2021; Mifsud et al., 2019). It is prescribed as a single oral dose, which makes it an attractive option. Baloxavir appears to have a relatively low barrier to resistance emergence, especially in children (Hayden et al., 2018; Hirotsu et al., 2020). In clinical settings, PA-I38T is the primary mutation that confers resistance to baloxavir, and viruses with this mutation have been reported to sporadically transmit from human-to-human (Omoto et al., 2018; Imai et al., 2020; Takashita et al., 2019). Other changes at this and other PA residues have also been associated with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir (Table S1). Taken together, these findings underscore the need to continuously monitor antiviral susceptibility of seasonal influenza viruses.

Influenza virologic surveillance is carried out by laboratories around the world with the aims to characterize influenza viruses causing infections in humans, select candidate vaccine viruses, and detect the emergence of antigenically novel and antiviral-resistant viruses. The landscape of US national influenza surveillance is complex but comprehensive and layered, where the Influenza Division/CDC, in collaboration with state and local jurisdiction public health partners, collects and analyzes data from multiple surveillance systems (https://www.cdc.gov/fluview/overview/index.html). The multiple elements of the US national virologic surveillance are categorized into five tiers, beginning at the point-of-care settings (tiers 1 and 2), state Public Health Laboratories (PHLs, tier 3), three state PHLs designated as National Influenza Reference Centers (NIRCs, tier 4), and ending with Influenza Division laboratories at CDC (tier 5) (Jester et al., 2018). A decade ago, the Right Size Roadmap was developed by the CDC in collaboration with the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) to provide a nationally representative standardized sampling strategy, which ensured data confidence (https://www.aphl.org/aboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID-Influenza-Right-Size-Roadmap-Edition2.pdf). Notably, antiviral susceptibility monitoring conducted as a part of Right Size virologic surveillance has been strengthened by supplemental in-state surveillance where detection of oseltamivir-resistant viruses has been carried out by either state PHLs or NIRCs using pyrosequencing (Okomo-Adhiambo et al., 2015; Storms et al., 2012). CDC has provided protocols, reference materials and other support (e.g., quality assurance). In subsequent years, the NIRC in New York State Department of Health (Wadsworth Center; NY NIRC) has served as the designated laboratory for supplemental antiviral surveillance.

To further improve the efficiency of virologic surveillance, implementation of the Sequence First Initiative began in 2014 first at CDC, then CDC in partnership with APHL established a next generation sequencing (NGS) pipeline at three NIRCs (https://www.aphl.org/programs/infectious_disease/influenza/Pages/default.aspx). Under this initiative, all submitted samples (clinical specimens or isolates) are subjected to NGS to generate virus genome sequences without a need for virus isolation or further passaging in cells or eggs (Jester et al., 2018). This major technological advancement facilitated changes to virologic surveillance including antiviral susceptibility monitoring. The previous strategy was to “propagate and test more viruses” at CDC and NIRCs. Viruses identified as outliers based on in vitro testing were then sequenced at CDC to identify mutations responsible for the altered phenotype. The Sanger method was principally used to sequence two or three virus genes of representative viruses and those identified as outliers. With the implementation of genomic NGS, the testing paradigm shifted to “sequence to guide phenotypic testing” (https://www.cdc.gov/flu/php/viruses/genetic-characterization.html). This testing algorithm reduced efforts and time associated with virus culturing and phenotypic analysis and reduced redundant phenotypic testing, while allowing simultaneous detection of all known molecular markers of drug resistance (https://www.cdc.gov/fluview/overview/index.html).

Approval of baloxavir brought up a need to develop and implement a phenotypic assay suitable for surveillance purposes. At first, CDC laboratory used a single-cycle, replication-based assay known as high content imaging-based neutralization test (HINT), which yielded desirable testing outcomes and facilitated establishment of a provisional cut-off for surveillance data reporting (Gubareva et al., 2019). To improve throughput and turnaround time and eliminate dependence on highly specialized equipment, a streamlined version of HINT, known as Influenza Replication Inhibition Neuraminidase-based Assay (IRINA), was developed and has been used to conduct baloxavir surveillance since the 2022–2023 season (Patel et al., 2022). It is noteworthy that the Sequence First approach was instrumental to detect PA mutants with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir as they rarely occur in nature (Gubareva et al., 2019). Those PA mutants were made available to other laboratories for reference purposes (https://www.internationalreagentresource.org/Catalog.aspx?q=Baloxavir%20Susceptibility%20Reference%20Virus%20Panel).

As outlined above, several major events have shaped the influenza virologic and antiviral susceptibility surveillance in the 21st century: emergence of drug-resistance, the 2009 influenza pandemic, approval of new antivirals, technological advances in sequencing, bioinformatics, and implementation of new technologies at CDC and other laboratories. In this study, we described the antiviral susceptibility surveillance conducted by Influenza Division/CDC and partners in 2023–2024 influenza season providing a detailed algorithm, methods, and findings.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Viruses

Influenza positive specimens used in this study were submitted to three NIRCs by US PHLs and to CDC’s Influenza Division by laboratories located in countries that are members of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). All A (H3N2) and most A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses were propagated in MDCK-SIAT1 cells, whereas type B and some A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses (from PAHO countries) were propagated in MDCK cells. Reference influenza viruses from the CDC NA inhibitors and baloxavir susceptibility panels (International Reagent Resource; FR-1678 and FR-1755) were used for quality control purposes.

2.2. NGS and sequence analysis

Viral RNA was extracted using QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen) and codon-complete influenza genome was amplified using Uni/Inf primer set and Super-Script III one-step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq High Fidelity enzyme (Invitrogen). Indexed paired end libraries were generated using Nextera XT sample preparation kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Illumina MiSeq was used to generate raw sequence reads that were assembled into consensus genomes by IRMA with the default FLU module (Shepard et al., 2016). In addition to the quality control set within IRMA, sequences were also required to meet the following criteria: i) negative controls on the run’s flowcell have <1000 reads matching influenza and <1 % of reads matching influenza, ii) fewer than 10 minor alleles ≥5 %, iii) ≥ 90 % of the reference segment covered, iv) no premature stop codons, and v) a median coverage depth ≥100x.

2.3. NA inhibition (NI) assay

Virus susceptibility to NA inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir, peramivir, and laninamivir) was tested using the CDC standardized fluorescence-based NI assay as previously described (Okomo-Adhiambo et al., 2013, 2016). NI assay is a surrogate phenotypic, functional assay that determines drug concentration required to inhibit NA enzyme activity by 50 % (IC50). The relative fluorescence unit (RFU) readouts were curve-fitted using nonlinear regression to determine IC50 (Okomo-Adhiambo et al., 2013). Fold change in IC50 of a sequence-flagged virus (i.e., virus identified as carrying a known or suspected molecular marker of reduced inhibition) was calculated relative to a subtype- or lineage-specific median generated by testing representative viruses that circulated during the 2023–2024 season. Fold changes were interpreted according to the arbitrary criteria adopted by surveillance laboratories: “normal inhibition” (type A <10-fold; type B < 5-fold), “reduced inhibition (RI)” (type A 10–100-fold; type B 5–50-fold), and “highly reduced inhibition (HRI)” (type A >100-fold; type B > 50-fold) (Govorkova et al., 2022; Meijer et al., 2014).

2.4. IRINA

To test virus susceptibility to baloxavir, cell culture-based IRINA was carried out as previously described (Patel et al., 2022). IRINA measures enzyme activity of nascent NA molecules expressed on the surface of virus-infected cells as an indicator of virus replication. Baloxavir effective concentration yielding 50 % reduction in NA activity (EC50) was determined by curve fitting RFU readouts. A set of viruses representing different geographic areas and collection dates were grouped by type and subtype and tested to determine the baseline baloxavir susceptibilities for the season (median EC50s). These median values were used to identify potential outliers and to characterize sequence-flagged viruses. For surveillance purposes, >3-fold increase in EC50 value of test virus over the median was used as the provisional cut-off to report reduced baloxavir susceptibility (Gubareva et al., 2019; Govorkova et al., 2022). When available, PA sequence-matched control virus was also tested to delineate the effect of a particular PA substitution on baloxavir susceptibility.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of influenza virologic surveillance and antiviral testing conducted by CDC

In this study, the influenza virologic surveillance conducted by CDC with partners included three parts: US national, US supplemental, and other PAHO countries (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the three parts of the virologic surveillance system coordinated by CDC Influenza Division, with a focus on antiviral susceptibility surveillance for the 2023–2024 season, which spanned from October 1, 2023 to September 30, 2024. The three parts of the virologic surveillance system are: US national, US supplemental in-state, and other PAHO countries. Two domestic surveillance systems, national and supplemental in-state are administered in collaboration with APHL. The virus transfer, NGS data transfer, and reporting of data are captured in this illustration. For US national surveillance, 50 state PHLs (*including District of Columbia (federal district) and Puerto Rico (territory)) submitted specimens to three NIRCs. NGS and virus isolation of these specimens were carried out by three NIRCs and NGS data and virus isolates were transferred to CDC.

US supplemental in-state surveillance is based on a sequence-only approach. For 2023–2024 season, nine PHLs submitted specimens for antiviral surveillance to designated NY NIRC laboratory, which reported cumulative pyrosequencing-based testing results to submitting PHLs and CDC. As per new implemented initiatives, three NIRCs and six ISCs began carrying out NGS on additional specimens collected in a respective state and shared sequence data with CDC. For surveillance in other PAHO countries, laboratories located in 25 countries submitted influenza positive specimens to CDC; NGS and virus isolation in cell culture were carried out by CDC laboratories.

On combined viruses submitted for US national and other PAHO countries surveillance, CDC laboratory performed the sequence-based screening for antiviral susceptibility assessment and in vitro testing of subset of viruses with antivirals. Antiviral data for US national surveillance were weekly posted on CDC FluView. Generated NGS data from all three parts of surveillance were deposited into influenza sequence databases (NCBI and GISAID).

The location of three state PHLs designated as NIRCs and six as ISCs are shown with two-letter US state postal abbreviations (CA, California; CO, Colorado; FL, Florida; HI, Hawaii; MA, Massachusetts; MN, Minnesota; NY, New York; TX, Texas; WI, Wisconsin). The names of three NIRCs are: California Department of Public Health Viral and Rickettsial Disease Laboratory, New York State Department of Health (Wadsworth Center), and Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene; and of six ISCs are: Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Florida Department of Public Health Laboratories, Hawaii State Department of Health, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Minnesota Department of Health, and Texas Department of State Health Services.

US national:

As per Right Size guidance, PHLs in 50 states and territories submitted up to 14 clinical specimens (4 A (H1N1)pdm09, 6 A (H3N2), and 4 B/Victoria) every two weeks to one of the three NIRCs (Fig. 1). NIRCs received a total of 5842 specimens (Table S2), successfully performed NGS analysis of 5736 (98 %), and shared sequence data with CDC. Notably, NIRCs promptly alerted CDC about the presence of oseltamivir-resistance conferring mutation, NA-H275Y in six A (H1N1) pdm09 viruses. NIRCs attempted to isolate virus from 65 % of received specimens and shipped 3505 successfully isolated viruses (92 % of attempted) to CDC for storage and further characterization, including antiviral testing. National data are posted weekly on FluView (https://www.cdc.gov/fluview/surveillance/past-reports.html) and included in the season summary as a web report (https://www.cdc.gov/flu/whats-new/flu-summary-2023-2024.html).

US supplemental:

For antiviral supplemental surveillance, PHLs have been asked to submit up to five additional specimens biweekly. During the 2023–2024 season, nine PHLs submitted a total of 328 specimens for testing to the designated laboratory at NY NIRC (Fig. 1). NY NIRC provided cumulative reports on testing outcomes to submitting state PHLs and CDC. Pyrosequencing was mainly used by NY NIRC in 2023–2024, but efforts have been made to transition to NGS as the future primary method.

Notably, during the 2023–2024 season, all three NIRCs and six recently established Influenza Sequencing Centers (ISCs) in Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Texas have been tasked to carry out NGS on additional specimens collected in their state and share sequence data with CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/flu/php/genomic-sequencing-infrastructure/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/genomic-sequencing-infrastructure.htm). This resulted in NGS data for over 1500 viruses. This part of surveillance is based on a sequence-only approach and have been used to obtain additional information on viruses circulating at a state level.

Other PAHO countries:

During this season, CDC received 1295 influenza positive specimens from laboratories located in 25 countries from the PAHO region (Fig. 1, Table S3). Among those, 1154 (89 %) were sequenced and 711 (55 %) were isolated for further characterization (Table S3).

3.2. Influenza antiviral susceptibility monitoring

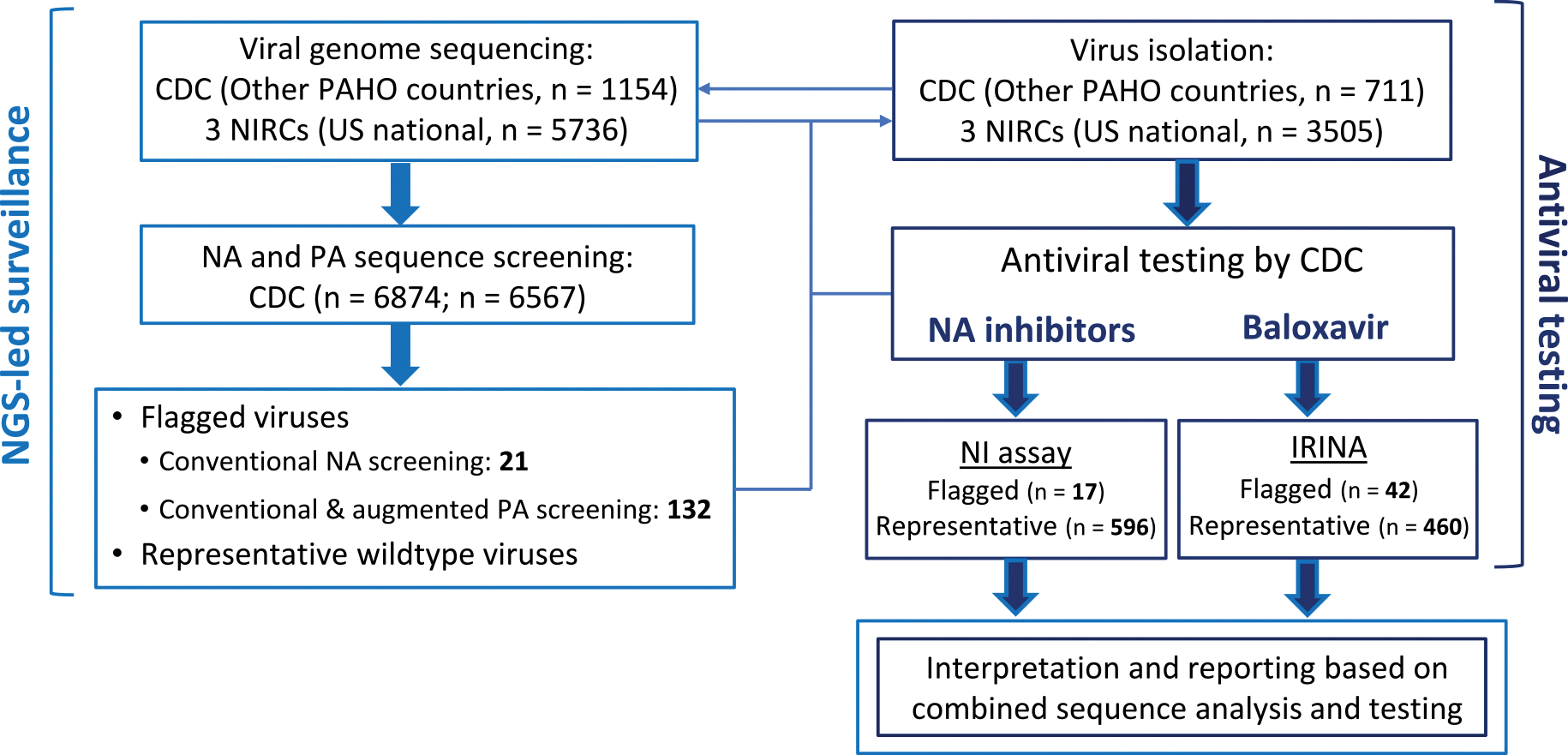

Since molecular markers that confer resistance to M2 blockers are well established, we used sequence-only analysis to detect viruses resistant to these medications (Deyde et al., 2007). The assessment of virus susceptibility to NA inhibitors and baloxavir was performed using the combination of sequence analysis and in vitro testing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Antiviral testing algorithm and testing volume in 2023–2024 influenza season. Of received specimens from other PAHO countries and for US national surveillance, 1154 and 5736 viruses were sequenced by CDC laboratory and three NIRCs, respectively.

CDC laboratory screened the generated NA sequences of 6874 viruses using conventional approach to flag viruses that had substitutions previously associated with reduced or highly reduced inhibition (RI/HRI) by NA inhibitors or a new substitution at a residue previously associated with RI/HRI. PA sequences of 6567 viruses were screened for substitutions previously associated with reduced baloxavir susceptibility. The conventional approach was augmented by identifying viruses with either new substitutions at previously reported residues or any substitution at 14 additional residues implicated in drug-binding (see result section for more information). This led to identifying a total of 153 viruses with known or suspected substitutions (21 with NA and 132 with PA changes).

For other PAHO countries and US national surveillance, 711 and 3505 viruses were isolated in cell culture by CDC laboratory and three NIRCs, respectively. Isolates of sequence-flagged viruses were subjected to NGS sequencing to confirm that no changes occurred during virus culturing. Viruses were tested for susceptibility by NA inhibitors using the NA inhibition assay (NI assay), while baloxavir susceptibility was tested using cell culture-based Influenza Replication Inhibition Neuraminidase-based assay (IRINA).

A subset of representative viruses from both influenza A subtypes and B/Victoria-lineage (~7–9 % of sequenced) were tested to determine median IC50/EC50 values. Available isolates of sequence-flagged viruses (17 with NA and 42 with PA changes) were tested. Median IC50/EC50 values were used: i) to identify potential outliers, and ii) to characterize sequence-flagged viruses. Fold change in IC50 to NA inhibitors or in EC50 to baloxavir were interpreted according to the provisional criteria adopted by surveillance laboratories. Data interpretation and reporting was done based on combined sequence analysis and testing.

M2 blockers:

M2 sequences of 5123 influenza A viruses (2574 A (H1N1)pdm09 and 2549 A (H3N2)) were analyzed. Except two A (H1N1)pdm09 from US (0.04 %), all viruses had either M2-S31N (99.8 %) or M2-S31D (0.1 %), markers of cross-resistance to M2 blockers. A small proportion of viruses with M2-S31N (0.8 %) carried an additional substitution at residues previously associated with M2-blocker resistance, L26, V27 or A30 (Data not shown).

NA inhibitors:

We analyzed NA sequences of 6874 viruses and 21 were sequence-flagged either with substitutions previously associated with RI/HRI by any NA inhibitor (n = 16) or new substitutions at residues previously associated with RI/HRI (n = 5) (Fig. 2, Table 1). Of these, 15 belonged to the A (H1N1)pdm09 subtype and six to B/Victoria lineage.

Table 1.

Assessment of NA inhibitor susceptibility of viruses collected in the PAHO region using sequence analysis and NA inhibition assay.a.

| Type/subtype or lineage | NA sequence analysis |

NA inhibition assay |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA substitutionb | US state (No. viruses) | Other country (No. viruses) | No. flagged viruses | No. tested viruses | IC50 nM (fold)c |

||||

| Oseltamivir | Zanamivir | Peramivir | Laninamivir | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| A (H1N1) pdm09 | H275Y | CT (1), CO (1), ME (1), MT (1), OR (1), WA (1) | Haiti (3) | 9 | 6 | 300.19 ± 44.42 (1429) | 0.21 ± 0.03 (1) | 24.81 ± 4.04 (354) | 0.42 ± 0.08 (2) |

| I223V + S247N | CT (1) | – | 1 | 1 | 2.80 (13) | 0.54 (3) | 0.30 (4) | 0.64 (3) | |

| Q136H | AK (1) | – | 1 | 1 | 0.21 (1) | 0.18 (1) | 0.09 (1) | 0.28 (1) | |

| D199V | – | Brazil (1) | 1 | 1 | 0.47 (2) | 0.23 (1) | 0.08 (1) | 0.23 (1) | |

| I223T | CA (1), NY (1) | Canada (1) | 3 | 2 | 0.72, 0.99 (3, 5) | 0.29, 0.31 (2, 2) | 0.09, 0.1 (1, 1) | 0.27, 0.26 (1, 1) | |

| B/Victoria | D197N | OH (1) | Canada (1) | 2 | 2 | 80.88, 123.86 (3, 5) | 8.02, 8.93 (9, 10) | 2.10, 3.07 (6, 9) | 2.95, 2.85 (4, 4) |

| H273Y | CA (1) | – | 1 | 1 | 58.30 (2) | 1.02 (1) | 73.69 (223) | 0.85 (1) | |

| A245G | TX (2) | – | 2 | 2 | 31.04, 37.18 (1, 1) | 0.80, 0.88 (1, 1) | 4.53, 4.51 (14, 14) | 0.43, 0.59 (1, 1) | |

| H273Q | – | Canada (1) | 1 | 1 | 0.63 (0.03) | 2.65 (3) | 0.08 (0.23) | 0.76 (1) | |

IC50, 50 % inhibitory concentration; NA, neuraminidase; PAHO, Pan American Health Organization; US, United States.

NA sequences of 6874 viruses (2569 A (H1N1)pdm09, 2542 A (H3N2), and 1763 B/Victoria; 5729 from US and 1145 from other countries) were screened for the presence of amino acid substitutions previously reported to reduce inhibition of enzyme activity by a respective antiviral (Govorkova et al., 2022). In addition, viruses containing a new substitution at a residue previously associated with reduced or highly reduced inhibition were also sequence-flagged. Available isolates of sequence-flagged viruses were tested with NA inhibitors using the fluorescence-based NA inhibition assay. US states are listed using two-letter US postal abbreviations.

Substitution is shown using type- or subtype-specific NA amino acid numbering system.

Virus isolates were tested against each antiviral in at least 2 independent tests. Mean ± standard deviation of IC50s is shown when three or more viruses with indicated NA substitution were tested. If a single or two NA mutants were tested, average of two IC50 values is shown. Fold change in IC50 was calculated versus subtype- or lineage-specific median IC50 generated by testing representative viruses that circulated during 2023–2024 season (see Table 2). For amino acid substitutions that conferred reduced or highly reduced inhibition by any of NA inhibitor, their respective folds are shown in bold. Fold change was also calculated versus IC50 of a respective NA sequence-matched control virus for few of the sequence-flagged viruses (A (H1N1)pdm09 with I223T and B/Victoria with D197N, H273Y, A245G, or H273Q), which remained similar as determined using the median IC50.

Among sequence-flagged A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses, nine had NA-H275Y, including one each detected in the US states, Connecticut, Colorado, Maine, Montana, Oregon, and Washington; and three in Haiti (Table 1, S4). In addition, one virus collected in the US had dual substitutions, NA-I223V + S247N, recently shown to confer RI by oseltamivir (Patel et al., 2024). Three viruses had NA-I223T, while two viruses had new substitutions, NA-Q136H or NA-D199V. Among B/Victoria viruses, three carried known substitutions, NA-D197N (n = 2) or NA-H273Y (n = 1). Three viruses had new substitutions, two from the US with NA-A245G and one from Canada with NA-H273Q (Table 1). No B/Yamagata lineage viruses were detected.

Following sequence analysis, we tested viruses using NI assay for two purposes: i) to establish baseline susceptibility (median IC50s) using representative viruses from different circulating groups (n = 596), and ii) to assess susceptibility of sequence-flagged viruses (n = 17). Viruses from both influenza A subtypes exhibited similar baseline susceptibilities (<2 times difference) for all NA inhibitors, with peramivir having the lowest median IC50s (Table 2). Compared to influenza A, median IC50s for B/Victoria viruses were elevated ~2–5-fold for all NA inhibitors, except for oseltamivir whose IC50s were elevated by ~119–178-fold. This confirmed previous reports that oseltamivir is less effective at inhibiting NA activity of type B viruses (Table 2) (Franco-May et al., 2024; Okomo-Adhiambo et al., 2013, 2016).

Table 2.

Baseline susceptibility of influenza viruses to NA inhibitors determined in NA inhibition assay.a.

| Test viruses | IC50 nM Oseltamivir | Zanamivir | Peramivir | Laninamivir | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | Mean ± SD | Range | Median | |

| A (H1N1)pdm09 n = 224 | 0.23 ± 0.14 | 0.10–1.16 | 0.21 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 0.11–0.75 | 0.17 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.03–0.28 | 0.07 | 0.21 ± 0.07 | 0.10–0.56 | 0.20 |

| A (H3N2) n = 204 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 0.08–0.90 | 0.14 | 0.33 ± 0.18 | 0.14–2.23 | 0.29 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.05–0.25 | 0.08 | 0.35 ± 0.09 | 0.22–0.98 | 0.34 |

| B/Victoria n = 168 | 24.80 ± 5.33 | 9.47–44.10 | 24.91 | 0.99 ± 0.35 | 0.49–2.96 | 0.90 | 0.35 ± 0.11 | 0.14–0.88 | 0.33 | 0.80 ± 0.13 | 0.50–1.29 | 0.80 |

| Reference virusesb | Mean ± SD | Range | Fold | Mean ± SD | Range | Fold | Mean ± SD | Range | Fold | Mean ± SD | Range | Fold |

| A/Illinois/45/2019 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.14–0.20 | – | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.12–0.21 | – | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.05–0.06 | – | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.16–0.23 | – |

| A/Alabama/03/2020 NA-H275Y | 225.31 ± 47.66 | 154.37–302.27 | 1408 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 0.16–0.31 | 1 | 16.13 ± 2.77 | 12.94–20.56 | 301 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.32–0.46 | 2 |

IC50, 50 % inhibitory concentration; NA, neuraminidase; SD, standard deviation.

Indicated numbers of influenza viruses were tested in presence of NA inhibitors using fluorescence-based NA inhibition assay to determine the subtype- or lineage-specific baseline susceptibility. The test viruses did not contain any known NA substitutions of concern.

NA-H275Y virus and its NA sequence-matched counterpart lacking this substitution are from the CDC NA inhibitor susceptibility reference virus panel. Mean ± SD of IC50s and fold change conferred by NA-H275Y were calculated based on results from 11 independent tests.

To interpret NI assay results for sequence-flagged viruses, we primarily used established median IC50s; for few viruses, the result was also confirmed using IC50s of NA sequence-matched viruses (Tables 1 and 2, S4). As expected, A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses with NA-H275Y displayed HRI by oseltamivir and peramivir, while the virus with NA-I223V + S247N showed RI by oseltamivir only. Conversely, viruses with NA-Q136H, NA-D199V, or NA-I223T displayed <10-fold increase in IC50s, interpreted as normal inhibition (Table 1).

Two B/Victoria viruses with NA-D197N exhibited RI by zanamivir and peramivir, and one of them also showed borderline RI (5-fold) by oseltamivir. NA-H273Y conferred HRI by peramivir, while a different substitution at the same residue, NA-H273Q had drastically opposite effects improving the ability of oseltamivir and peramivir to inhibit NA activity (Table 1). The new substitution NA-A245G conferred 14-fold RI by peramivir relative to both, lineage-specific median IC50 or a sequence-matched virus without this mutation.

Frequency of NA-H275Y and clusters of NA mutants:

Through US national surveillance, we identified six NA-H275Y viruses (6/2160; 0.28 %) (Table 1, S2). In addition, the designated laboratory (NY NIRC) detected four NA-H275Y among 196 A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses submitted by nine PHLs (4/196, 2.04 %). All four NA-H275Y viruses were from NY state, of which two samples were collected following treatment (Table S4). NGS data generated by six ISCs led to detection of three additional NA-H275Y viruses among 622 viruses analyzed (3/622; 0.48 %) (Table S4). Combined data showed that oseltamivir- and peramivir-resistant viruses circulated at a low frequency in the US (13/2978; 0.44 %).

In Haiti, three NA-H275Y viruses were detected during the reported period (Table 1). Among a total of 25 A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses that were submitted from Haiti during 2023–2024 season and successfully sequenced, an additional virus with NA-H275Y was identified that was collected outside of reporting period. Interestingly, all four NA-H275Y viruses were collected in the town of Jérémie and the submitting laboratory confirmed that only these viruses were available from this location (Table S5). The collection dates of these NA-H275Y viruses spanned from September 12 to November 3, 2023. They were collected from outpatients of different ages, who visited two relatively close sites (<1 mile); three visited Hôpital Saint Antoine de Jérémie and one from Klinik Pèp Bondye HHF (Table S5). NGS analysis revealed high nucleotide level similarity in all gene segments. Moreover, these viruses shared two rare substitutions in the PB2 protein, PB2-S334G and PB2-V480I. At the time of our analysis, this combination of mutations had not been found in other sequences of viruses collected in Haiti or in other A (H1N1)pdm09 sequences deposited in public databases. Available NGS and other information point to a local circulation of the oseltamivir-resistant A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses in Haiti in autumn of 2023.

Based on hemagglutinin phylogenetic analysis of 17 NA-H275Y viruses, seven from US belonged to clade 5a.2a.1, while remaining ten (from US and Haiti) belonged to clade 5a.2a.

Through US national surveillance, we identified NA-A245G in two B/Victoria viruses, a new substitution that conferred RI by peramivir (Table 1). An additional virus with this mutation was identified through ISC-based surveillance in Texas. Notably, all three viruses were collected on the same day (February 22, 2024) in Tarrant County, Texas from children aged 6–11 (Table S5). All three shared the same genomic sequences, indicating likely transmission among contacts. NA sequence analysis of available B/Victoria viruses from Texas (n = 58) found no additional viruses with NA-A245G.

Overall, detection of influenza viruses with substitutions conferring RI/HRI by NA inhibitors was low. None of the sequence-flagged viruses exhibited RI by laninamivir. None of A (H3N2) viruses analyzed had known or suspected NA substitutions that may confer RI/HRI by any NA inhibitor.

PA inhibitor baloxavir:

Of 6567 viruses subjected to PA sequence analysis, one A (H3N2) virus was identified with substitution PA-I38T, associated with reduced baloxavir susceptibility (Table S1). Interestingly, this virus was collected from a patient in Hawaii, US, who had not taken baloxavir but had recently traveled from Japan. Three B/Victoria viruses with PA-M34I were sequence-flagged for confirmatory phenotypic testing (Table S6). This PA change in type B virus was previously shown not to affect baloxavir susceptibility (Govorkova et al., 2022).

As baloxavir is a newer antiviral, molecular markers affecting susceptibility are not fully elucidated. Therefore, we performed augmented PA sequence analysis to identify: i) new substitutions at previously reported residues, or ii) substitutions at 14 additional residues implicated in PA inhibitor binding via crystal structure or mutational analysis (Table S1). This augmented analysis yielded 128 sequence-flagged viruses (61 A (H1N1)pdm09, 57 A (H3N2), and 10 B/Victoria) (Table S6), of which eight had new substitutions at previously reported residues: PA-L28M or PA-M34V. Among remaining sequence-flagged viruses, type A viruses most carried PA-A20T (86/120; ~72 %), or PA-A20V (8/120; ~6.6 %) (Taniguchi et al., 2024). There were also type A viruses with PA substitution at residue 24, 84, 106, 120, or 122, and B/Victoria viruses with change at PA residue 121, 123, or 134 (Table S6).

A subset of representative viruses (n = 460) was tested in the presence of baloxavir using IRINA to determine subtype- or lineage-specific median EC50 (Fig. 3). 42 available isolates of sequence-flagged viruses were also tested. A (H1N1)pdm09 and A (H3N2) subtypes had similar median EC50s, 0.80 and 0.58 nM, respectively. Median EC50 for B/Victoria viruses was ~5–7-fold higher (4.06 nM), consistent with results generated using different assays (Gubareva et al., 2019; Koszalka et al., 2019; Patel et al., 2022; Takashita et al., 2018). Only three sequence-flagged viruses that we tested had EC50s above the subtype-specific >3-fold cut-off (Fig. 3, Table S6). Expectedly, an A (H3N2) virus with PA-I38T showed 102-fold higher EC50 (Fig. 3). Two A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses with new substitutions, PA-Y24C or PA-V122A showed 4- or 11-fold higher EC50s relative to median, respectively (Fig. 3). Notably, both these viruses showed 4- or 9-fold increase when compared to the PA sequence-matched controls, respectively (Tables S4 and S6).

Fig. 3.

Assessment of baloxavir susceptibility using IRINA. Representative influenza viruses (n = 460) lacking PA substitutions of concern were tested to determine subtype- or lineage-specific median EC50. In a scatter dot plot, median with interquartile range is shown. All the representative viruses without PA substitutions had EC50 values below the subtype- or lineage-specific >3-fold cut-off (i.e., normal susceptibility). EC50s of two A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses with PA-Y24C or PA-V122A and an A(H3N2) virus with PA-I38T were also plotted, which showed 4-, 11- and 102-fold increase, respectively (i.e., reduced susceptibility).

Taken together, sequence analysis and phenotypic testing indicated a low frequency (0.05 %) of viruses with reduced baloxavir susceptibility during the 2023–2024 season.

3.3. Interim PA sequence analysis to assess susceptibility to baloxavir

There is consensus that PA-I38T is a primary pathway to baloxavir-resistance (Ince et al., 2020; Omoto et al., 2018), but there are no well-established laboratory correlates for clinically relevant baloxavir resistance. Numerous studies, including clinical, surveillance, mutational, and other studies have identified many PA substitutions, especially in influenza A viruses that elevate baloxavir EC50s in vitro (Table S1).

Sequence-only assessment of baloxavir susceptibility can be useful for laboratories without capabilities for in vitro testing or in situations when virus is not readily available. To aid in the sequence-based assessment of baloxavir susceptibility, we divided PA substitutions into three categories: i) primary (reduced susceptibility); ii) secondary (suspected reduced susceptibility); and iii) tertiary (normal susceptibility) (Table 3, S7). Notably, detection of PA substitution from the secondary group without phenotypic testing can only be interpreted as suspected reduced susceptibility.

Table 3.

The interim PA sequence-based analysis to assess baloxavir susceptibility of influenza A viruses.a.

| PA CEN substitution | Common characteristics | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Primaryb | I38T | • Primary treatment-emergent; associated with diminished virologic response in clinical settings • Rarely as natural polymorphism • Confers elevated baloxavir EC50 in cell culture (11–614-fold) |

• Reduced susceptibility • Phenotypic testing is not required, but helpful |

| I38 F, M, N, S | • Treatment-emergent • Rarely as natural polymorphisms • Confer elevated baloxavir EC50 (4–112-fold) |

||

| Secondary | E18G E23 G, K, R Y24C K34R A36V A37T I38L L106R E119D V122A E198K E199 D, G, K |

• Most are natural polymorphisms • Some emerged post baloxavir exposure or introduced for assessment • Confer variably elevated baloxavir EC50 (<3–19 fold) |

• Suspected reduced susceptibility • Phenotypic testing is required |

| Tertiary (this study only)c | A20 T, V Y24F L28M R84K L106I I120 L, V V122 I, L |

• Natural polymorphism • No or little change in EC50 (<3-fold) |

• Normal susceptibility • Phenotypic testing is not required, but helpful |

CEN, cap-dependent endonuclease; EC50, 50 % effective concentration; PA, polymerase acidic subunit.

PA CEN domain for type A viruses spans from amino acid residue 1 to 198 (Omoto et al., 2018); residue 199 is adjacent to CEN and belongs to the linker region. The consensus amino acid at residue 28 is proline (P) and leucine (L) for A (H1N1)pdm09 and A (H3N2) backgrounds, respectively. See Table S1 for additional information on the residues and substitutions shown.

In type B viruses, PA-I38T confers 5- to 15-fold elevated baloxavir EC50. PA-I38F and PA-I38M were shown to confer variably elevated EC50 (<3- to 8-fold) and phenotypic testing would be required to report reduced susceptibility in type B viruses.

Previously reported tertiary category PA amino acid substitutions for type A and B viruses are listed in Table S7.

4. Discussion

In this study, we described the antiviral surveillance conducted by Influenza Division/CDC and its domestic and international country partners from the PAHO region for the 2023–2024 season. In collaboration with APHL, CDC also participates in supplemental antiviral surveillance aimed at increasing the volume of data at an individual US state-level. This arm of surveillance has greatly expanded in recent years. One example of the advancements is the transition from pyrosequencing, which detects limited key substitutions, to NGS-based analysis allowing simultaneous detection of all previously reported resistance-conferring changes for all approved antivirals. Another example is the generation of NGS data on additional influenza viruses collected at a state-level by the recently designated six ISCs, further enhancing supplemental NGS-based surveillance (https://www.cdc.gov/flu/php/genomic-sequencing-infrastructure/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/genomic-sequencing-infrastructure.htm). Together, this improves granularity of antiviral susceptibility data and provides additional valuable information on properties of circulating and emerging viruses.

During the 2023–2024 season, over 8000 genome sequences of influenza viruses were generated by CDC, NIRCs, and ISCs. NGS analysis was the primary approach for comprehensive virologic surveillance including antiviral susceptibility assessment (Table S8). When a resistance-conferring molecular marker is well-established (e.g., NA-H275Y), the NGS-driven approach works effectively to detect, and monitor spread of resistant viruses. However, interpreting sequence-only data can be challenging.

Numerous changes in the antiviral-targeted proteins have been reported in literature or identified via surveillance (Govorkova et al., 2022; Table S1). Some NA substitutions are subtype-, lineage-, and even strain-specific, others emerge during virus propagation in cell culture, and some are neutral mutations with no or only marginal effects on IC50. Improvements are needed in terms of presentation of these inventories as well as developing bioinformatic tools to aid surveillance laboratories in sequence analysis. FluSurver (https://flusurver.bii.a-star.edu.sg) has begun to address some of these needs by providing a research tool, which is also accessible on the GISAID database, that identifies substitution at specific protein residues associated with reduced antiviral susceptibility compared to a reference sequence. However, interpretation of this data by the end-user remains critical for adequate assessment of identified changes and further refinement and continual updates are needed.

The present study describes our current antiviral testing algorithm and interpretation of combined sequence analysis and testing outcomes. We report that nearly all seasonal influenza A viruses in circulation remain resistant to M2 blockers. Conversely, viruses displaying reduced susceptibility to NA inhibitors and baloxavir were detected at a low frequency. Furthermore, none of the A (H3N2) viruses were detected with NA changes known to confer RI/HRI by any of four NA inhibitors. Additionally, none had substitutions that emerged during culturing in MDCK cells (e.g., NA-Q136K). This emphasizes the importance of using MDCK-SIAT1 cells for virus isolation as well as shorter propagation time, which together reduce the emergence of NA mutants during propagation and improves the quality of isolates for testing in NI assay (Mishin et al., 2014).

Although viruses displaying RI/HRI in NI assay were rarely detected, we identified two small clusters. The first was detected in Haiti where four oseltamivir-resistant A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses with NA-H275Y were collected at the same locality during September–November 2023. The second cluster included three B/Victoria viruses carrying NA-A245G, which conferred RI by peramivir. All three viruses were collected from the same county in Texas on the same day. Notably, the third virus of this cluster was identified from sequences generated by the Texas ISC, while the other two were detected via US national surveillance. These community clusters are a reminder of the ability for some resistance-conferring NA mutants to transmit and circulate locally. The NGS data is especially valuable when investigating a potential cluster of drug-resistant viruses because such viruses are expected to share a high level of homology in all gene segments. To this point, the viruses from the Haiti cluster not only displayed the high level of homology in all genes, but also shared two rare PB2 mutations not found in any other viruses collected globally. Genomic NGS data are known to provide insights into the genesis of antiviral-resistant viruses, such as the acquisition of resistance via gene reassortment. In general, resistance-conferring mutations are not expected to provide an evolutionary advantage when the usage of antivirals is relatively low. However, resistant viruses may successfully compete with wildtype viruses under certain conditions, such as NA mutations that improve the balance of HA and NA functions (Neverov et al., 2015). Antiviral-resistant viruses can also gain evolutionary advantage by acquiring a favorable gene constellation (hitch-hiking mechanism) or an antigenically advanced hemagglutinin (Hurt, 2014; Mohan et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2012). The later mechanism was apparent in a small cluster of NA-H275Y viruses detected by our laboratory among inhabitants of a border detention center in Texas, US in January 2020 (Mohan et al., 2021).

We also sequence-flagged viruses with new substitutions at previously reported residues (e.g., NA-H273Q in B/Victoria virus). Whereas NA-H273Y was shown to elevate IC50s for oseltamivir and peramivir in type B viruses (Gubareva et al., 2017), NA-H273Q produced an opposite effect, which highlights the challenges of predicting NI testing outcomes based on sequence-only data.

In the past, a CDC standardized fluorescence-based NI assay was used by NIRCs to test NA inhibitor susceptibility for thousands of influenza viruses each year (Okomo-Adhiambo et al., 2016). Following the Sequence First initiative, only the Influenza Division/CDC laboratory conducts this testing but at a much smaller scale. It is worth mentioning that NI assay data continue to indicate a low inhibitory activity of oseltamivir towards type B viruses. Our laboratory previously reported 47- to 80-fold lower activity of oseltamivir against type B versus type A viruses circulated during 2011 (Okomo-Adhiambo et al., 2013). Here, we observed an even greater difference, ~119- to 178-fold. Notably, clinical studies have shown reduced effects of oseltamivir against influenza B compared to influenza A virus infections (Heinonen et al., 2010; Kawai et al., 2006; Sugaya et al., 2007). A recent study also showed that baloxavir was more effective than oseltamivir when used to treat children with influenza B virus infections (Sun et al., 2024).

Compared to NA, the PA CEN domain has lesser sequence variability (Dias et al., 2009; DuBois et al., 2012). Thus, NGS-based assessment of baloxavir susceptibility is less challenging. However, information on markers of reduced susceptibility to baloxavir is incomplete. In addition, there are certain differences in residues involved in baloxavir binding between type A versus B viruses (Omoto et al., 2018). In this study, we also enhanced PA sequence analysis by flagging viruses with substitutions other than those previously reported (Table S1). Specifically, we identified over 100 additional influenza A viruses with substitutions at residues implicated in binding of PA CEN inhibitors (Tables S1 and S8). Except for two viruses with PA-Y24C or PA-V122A, the remaining sequence-flagged viruses displayed normal susceptibility (Table S6). Residue 24 is part of the PA active site; through crystal structure, it was shown that baloxavir makes van der Waals contact with tyrosine at this residue in type A viruses (Omoto et al., 2018). Previous reports have shown that Y24 is highly conserved (~98 %) in influenza A viruses and PA-Y24H was observed as natural polymorphism at low frequency (~2 %), while PA-Y24C was rare (Taniguchi et al., 2024; Stevaert et al., 2013). Y24H in swine-origin viruses did not affect baloxavir susceptibility (Taniguchi et al., 2024). Here, our results showed that PA-Y24F in A (H1N1)pdm09 virus mildly elevated baloxavir EC50 (1.9-fold), while PA-Y24C in this virus background conferred reduced susceptibility (4-fold) to baloxavir (Table S6).

Similarly, valine at residue 122 is highly conserved (99.9 %) (Yang et al., 2024; Stevaert et al., 2013). Crystal structures have predicted that it interacts with the 5’ phosphate of RNA substrate and is involved in the hydrogen bond network necessary for baloxavir binding (Kumar et al., 2021; Omoto et al., 2018). PA-V122T mildly reduced virus susceptibility to an early PA inhibitor, L-742,001 (Stevaert et al., 2013), while PA-V122L was shown to affect viral cRNA and mRNA synthesis by altering the RNA-binding ability and CEN activity (Yang et al., 2024). Our results showed that PA-V122L in A (H3N2) and PA-V122I in A (H1N1)pdm09 virus had no effect on baloxavir susceptibility (Table S6). PA sequence analysis of 219,234 influenza A viruses (accessed from GISAID on October 17, 2024) revealed that PA-V122A is a very rare natural polymorphism, which we found in only 18 viruses (data not shown). Overall, this enhanced screening led to identification of two new markers of reduced baloxavir susceptibility, PA-Y24C and PA-V122A.

As NGS-based analysis has become a cornerstone for surveillance, we wanted to assist PHLs by offering a streamlined PA mutation inventory. Therefore, we divided known PA substitutions into three categories with respect to baloxavir susceptibility: primary, secondary, or tertiary. When more clinical, virologic, and phenotypic data become available, this classification will need revision. Phenotypic testing is required to supplement NGS analysis and availability of a reliable phenotypic assay is indispensable, especially considering the tight threshold for reporting reduced baloxavir susceptibility (i.e., EC50 > 3-fold above median or sequence-matched control virus) (Gubareva et al., 2019; Govorkova et al., 2022). When both comparators are used to calculate the fold change, but testing outcomes show discordance (<3- vs. >−3-fold), the result obtained relative to the EC50 of sequence-matched control virus should be reported.

We have shown that both single-cycle replication-based assays (HINT and IRINA) generate consistent results and provided good correlation between changes to PA CEN sequence and EC50s and corresponding fold changes (Gubareva et al., 2019; Patel et al., 2022). To reduce testing turnaround time, our laboratory transitioned from using HINT to IRINA for baloxavir susceptibility monitoring during the 2022–2023 season (https://www.cdc.gov/fluview/overview/index.html). Reference viruses can be used for quality control purposes and can aid in harmonizing reporting across different laboratories using IRINA and other cell culture-based assays.

Overall, our data highlight that the frequency of seasonal influenza viruses displaying reduced susceptibility to NA inhibitors or baloxavir remained low during the 2023–2024 season. In conclusion, our study describes the current methods and testing algorithm, which can be used to monitor susceptibility of circulating and emerging influenza viruses to FDA-approved antivirals. It also emphasizes a need for improved and readily accessible tools for NGS analysis as well as bioinformatic support for surveillance laboratories to streamline and expedite reporting of generated data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the US public health laboratories and laboratories located in countries that are members of the Pan American Health Organization for submission of influenza viruses. We are appreciative of productive collaboration with US National Influenza Reference Centers, Influenza Sequencing Centers, and sequencing core of Wadsworth center. The authors are most grateful to two members of the Molecular Epidemiology Team of CDC Influenza Division, Anwar Abd Elal and Carter Sadowski, for data management and technical assistance, respectively. We would like to acknowledge valuable contributions of other colleagues from the CDC Influenza Division and Dr. Trent Bullock for scientific editing.

Funding source and disclaimer

This publication was supported by the Cooperative Agreement Number NU60OE000104, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Association of Public Health Laboratories. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2025.106299.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mira C. Patel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Ha T. Nguyen: Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Vasiliy P. Mishin: Validation, Methodology, Investigation. Philippe Noriel Q. Pascua: Investigation. Chloe Champion: Investigation. Mercedes Lopez-Esteva: Investigation. Angiezel Merced-Morales: Investigation. Alicia Budd: Resources, Investigation. Marie K. Kirby: Resources, Investigation. Benjamin Rambo-Martin: Software, Data curation. Jennifer Laplante: Investigation. Allen Bateman: Resources, Project administration. Kirsten St. George: Resources, Project administration. Maureen Sullivan: Project administration, Funding acquisition. John Steel: Resources, Investigation. Rebecca J. Kondor: Supervision, Project administration. Larisa V. Gubareva: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Beigel JH, Hayden FG, 2021. Influenza therapeutics in clinical practice—challenges and recent advances. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 11. [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2006. High levels of adamantane resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses and interim guidelines for use of antiviral agents–United States, 2005–06 influenza season. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55, 44–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2009. Oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two summer campers receiving prophylaxis–North Carolina, 2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58, 969–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyde VM, Xu X, Bright RA, Shaw M, Smith CB, Zhang Y, Shu Y, Gubareva LV, Cox NJ, Klimov AI, 2007. Surveillance of resistance to adamantanes among influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) viruses isolated worldwide. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias A, Bouvier D, Crepin T, McCarthy AA, Hart DJ, Baudin F, Cusack S, Ruigrok RW, 2009. The cap-snatching endonuclease of influenza virus polymerase resides in the PA subunit. Nature 458, 914–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois RM, Slavish PJ, Baughman BM, Yun MK, Bao J, Webby RJ, Webb TR, White SW, 2012. Structural and biochemical basis for development of influenza virus inhibitors targeting the PA endonuclease. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-May DA, Gómez-Carballo J, Barrera-Badillo G, Cruz-Ortíz MN, Núñez-García TE, Arellano-Suárez DS, Wong-Arámbuza C, López-Martínez I, Wong-Chew RM, Ayora-Talavera G, 2024. Low antiviral resistance in influenza A and B viruses isolated in Mexico from 2010 to 2023. Antivir. Res. 227, 105918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garten RJ, Davis CT, Russell CA, Shu B, Lindstrom S, Balish A, Sessions WM, Xu X, Skepner E, Deyde V, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Gubareva L, Barnes J, Smith CB, Emery SL, Hillman MJ, Rivailler P, Smagala J, de Graaf M, Burke DF, Fouchier RA, Pappas C, Alpuche-Aranda CM, Lopez-Gatell H, Olivera H, Lopez I, Myers CA, Faix D, Blair PJ, Yu C, Keene KM, Dotson PD Jr., Boxrud D, Sambol AR, Abid SH, St George K, Bannerman T, Moore AL, Stringer DJ, Blevins P, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Ginsberg M, Kriner P, Waterman S, Smole S, Guevara HF, Belongia EA, Clark PA, Beatrice ST, Donis R, Katz J, Finelli L, Bridges CB, Shaw M, Jernigan DB, Uyeki TM, Smith DJ, Klimov AI, Cox NJ, 2009. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science 325, 197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govorkova EA, Takashita E, Daniels RS, Fujisaki S, Presser LD, Patel MC, Huang W, Lackenby A, Nguyen HT, Pereyaslov D, Rattigan A, Brown SK, Samaan M, Subbarao K, Wong S, Wang D, Webby RJ, Yen HL, Zhang W, Meijer A, Gubareva LV, 2022. Global update on the susceptibilities of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors and the cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir, 2018–2020. Antivir. Res. 200, 105281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubareva LV, Mishin VP, Patel MC, Chesnokov A, Nguyen HT, De La Cruz J, Spencer S, Campbell AP, Sinner M, Reid H, Garten R, Katz JM, Fry AM, Barnes J, Wentworth DE, 2019. Assessing baloxavir susceptibility of influenza viruses circulating in the United States during the 2016/17 and 2017/18 seasons. Euro Surveill. 24, 1800666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubareva LV, Besselaar TG, Daniels RS, Fry A, Gregory V, Huang W, Hurt AC, Jorquera PA, Lackenby A, Leang SK, Lo J, Pereyaslov D, Rebelo-de-Andrade H, Siqueira MM, Takashita E, Odagiri T, Wang D, Zhang Q, Meijer A, 2017. Global update on the susceptibility of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors, 2015–2016. Antivir. Res. 146, 12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Hirotsu N, Lee N, de Jong MD, Hurt AC, Ishida T, Sekino H, Yamada K, Portsmouth S, Kawaguchi K, Shishido T, Arai M, Tsuchiya K, Uehara T, Watanabe A, Baloxavir Marboxil Investigators G, 2018. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 913–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen S, Silvennoinen H, Lehtinen P, Vainionpää R, Vahlberg T, Ziegler T, Ikonen N, Puhakka T, Heikkinen T, 2010. Early oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children 1–3 years of age: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51, 887–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsu N, Sakaguchi H, Sato C, Ishibashi T, Baba K, Omoto S, Shishido T, Tsuchiya K, Hayden FG, Uehara T, Watanabe A, 2020. Baloxavir marboxil in Japanese pediatric patients with influenza: safety and clinical and virologic outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 971–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt AC, 2014. The epidemiology and spread of drug resistant human influenza viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 8, 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt AC, Hardie K, Wilson NJ, Deng YM, Osbourn M, Leang SK, Lee RT, Iannello P, Gehrig N, Shaw R, Wark P, Caldwell N, Givney RC, Xue L, Maurer-Stroh S, Dwyer DE, Wang B, Smith DW, Levy A, Booy R, Dixit R, Merritt T, Kelso A, Dalton C, Durrheim D, Barr IG, 2012. Characteristics of a widespread community cluster of H275Y oseltamivir-resistant A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza in Australia. J. Infect. Dis. 206, 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai M, Yamashita M, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Kiso M, Murakami J, Yasuhara A, Takada K, Ito M, Nakajima N, Takahashi K, Lopes TJS, Dutta J, Khan Z, Kriti D, van Bakel H, Tokita A, Hagiwara H, Izumida N, Kuroki H, Nishino T, Wada N, Koga M, Adachi E, Jubishi D, Hasegawa H, Kawaoka Y, 2020. Influenza A variants with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir isolated from Japanese patients are fit and transmit through respiratory droplets. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ince WL, Smith FB, O’Rear JJ, Thomson M, 2020. Treatment-emergent influenza virus polymerase acidic substitutions independent of those at I38 associated with reduced baloxavir susceptibility and virus rebound in trials of baloxavir marboxil. J. Infect. Dis. 222, 957–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester B, Schwerzmann J, Mustaquim D, Aden T, Brammer L, Humes R, Shult P, Shahangian S, Gubareva L, Xu X, Miller J, Jernigan D, 2018. Mapping of the US domestic influenza virologic surveillance landscape. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 1300–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai N, Ikematsu H, Iwaki N, Maeda T, Satoh I, Hirotsu N, Kashiwagi S, 2006. A comparison of the effectiveness of oseltamivir for the treatment of influenza A and influenza B: a Japanese multicenter study of the 2003–2004 and 2004–2005 influenza seasons. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43, 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszalka P, Tilmanis D, Roe M, Vijaykrishna D, Hurt AC, 2019. Baloxavir marboxil susceptibility of influenza viruses from the asia-pacific, 2012–2018. Antivir. Res. 164, 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer F, Smith GJD, Fouchier RAM, Peiris M, Kedzierska K, Doherty PC, Palese P, Shaw ML, Treanor J, Webster RG, Garcia-Sastre A, 2018. Influenza. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G, Cuypers M, Webby RR, Webb TR, White SW, 2021. Structural insights into the substrate specificity of the endonuclease activity of the infleunza virus cap-snatching mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 1609–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer A, Rebelo-de-Andrade H, Correia V, Besselaar T, Drager-Dayal R, Fry A, Gregory V, Gubareva L, Kageyama T, Lackenby A, Lo J, Odagiri T, Pereyaslov D, Siqueira MM, Takashita E, Tashiro M, Wang D, Wong S, Zhang W, Daniels RS, Hurt AC, 2014. Global update on the susceptibility of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors, 2012–2013. Antivir. Res. 110, 31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer A, Lackenby A, Hungnes O, Lina B, van-der-Werf S, Schweiger B, Opp M, Paget J, van-de-Kassteele J, Hay A, Zambon M, 2009. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus A (H1N1), Europe, 2007–08 season. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 552–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mifsud EJ, Hayden FG, Hurt AC, 2019. Antivirals targeting the polymerase complex of influenza viruses. Antivir. Res. 169, 104545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishin VP, Sleeman K, Levine M, Carney PJ, Stevens J, Gubareva LV, 2014. The effect of the MDCK cell selected neuraminidase D151G mutation on the drug susceptibility assessment of influenza A(H3N2) viruses. Antivir. Res. 101, 93–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan T, Nguyen HT, Kniss K, Mishin VP, Merced-Morales AA, Laplante J, St George K, Blevins P, Chesnokov A, De La Cruz JA, Kondor R, Wentworth DE, Gubareva LV, 2021. Cluster of oseltamivir-resistant and hemagglutinin antigenically drifted influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, Texas, USA, January 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 1953–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neverov AD, Kryazhimskiy S, Plotkin JB, Bazykin GA, 2015. Coordinated evolution of influenza A surface proteins. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okomo-Adhiambo M, Fry AM, Su S, Nguyen HT, Elal AA, Negron E, Hand J, Garten RJ, Barnes J, Xiyan X, Villanueva JM, Gubareva LV, 2015. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, United States, 2013–14. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21, 136–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okomo-Adhiambo M, Mishin VP, Sleeman K, Saguar E, Guevara H, Reisdorf E, Griesser RH, Spackman KJ, Mendenhall M, Carlos MP, Healey B, St George K, Laplante J, Aden T, Chester S, Xu X, Gubareva LV, 2016. Standardizing the influenza neuraminidase inhibition assay among United States public health laboratories conducting virological surveillance. Antivir. Res. 128, 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okomo-Adhiambo M, Sleeman K, Lysen C, Nguyen HT, Xu X, Li Y, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV, 2013. Neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility surveillance of influenza viruses circulating worldwide during the 2011 southern hemisphere season. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 7, 645–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto S, Speranzini V, Hashimoto T, Noshi T, Yamaguchi H, Kawai M, Kawaguchi K, Uehara T, Shishido T, Naito A, Cusack S, 2018. Characterization of influenza virus variants induced by treatment with the endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Sci. Rep. 8, 9633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MC, Flanigan D, Feng C, Chesnokov A, Nguyen HT, Elal AA, Steel J, Kondor RJ, Wentworth DE, Gubareva LV, Mishin VP, 2022. An optimized cell-based assay to assess influenza virus replication by measuring neuraminidase activity and its applications for virological surveillance. Antivir. Res. 208, 105457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MC, Nguyen HT, Pascua PNQ, Gao R, Steel J, Kondor RJ, Gubareva LV, 2024. Multicountry spread of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses with reduced oseltamivir inhibition, May 2023-February 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 30, 1410–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paules C, Subbarao K, 2017. Influenza. Lancet 390, 697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard SS, Meno S, Bahl J, Wilson MM, Barnes J, Neuhaus E, 2016. Viral deep sequencing needs an adaptive approach: IRMA, the iterative refinement meta-assembler. BMC Genom. 17, 708. [Google Scholar]

- Stevaert A, Dallocchio R, Dessi A, Pala N, Rogolino D, Sechi M, Naesens L, 2013. Mutational analysis of the binding pockets of the diketo acid inhibitor L-742,001 in the influenza virus PA endonuclease. J. Virol. 87, 10524–10538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storms AD, Gubareva LV, Su S, Wheeling JT, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Pan CY, Reisdorf E, St George K, Myers R, Wotton JT, Robinson S, Leader B, Thompson M, Shannon M, Klimov A, Fry AM, Group USARSW, 2012. Oseltamivir-resistant pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infections, United States, 2010–11. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18, 308–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugaya N, Mitamura K, Yamazaki M, Tamura D, Ichikawa M, Kimura K, Kawakami C, Kiso M, Ito M, Hatakeyama S, Kawaoka Y, 2007. Lower clinical effectiveness of oseltamivir against influenza B contrasted with influenza A infection in children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44, 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Wagatsuma K, Saito R, Sato I, Kawashima T, Saito T, Shimada Y, Ono Y, Kakuya F, Minato M, Kodo N, Suzuki E, Kitano A, Chon I, Phyu WW, Li J, Watanabe H, 2024. Duration of fever in children infected with influenza A(H1N1) pdm09, A(H3N2) or B virus and treated with baloxavir marboxil, oseltamivir, laninamivir, or zanamivir in Japan during the 2012–2013 and 2019–2020 influenza seasons. Antivir. Res. 228, 105938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashita E, Shimizu K, Usuku S, Senda R, Okubo I, Morita H, Nagata S, Fujisaki S, Miura H, Kishida N, Nakamura K, Shirakura M, Ichikawa M, Matsuzaki Y, Watanabe S, Takahashi Y, Hasegawa H, 2024. An outbreak of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 antigenic variants exhibiting cross-resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir in an elementary school in Japan, September 2024. Euro Surveill. 29 (50), 2400786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashita E, Ichikawa M, Morita H, Ogawa R, Fujisaki S, Shirakura M, Miura H, Nakamura K, Kishida N, Kuwahara T, Sugawara H, Sato A, Akimoto M, Mitamura K, Abe T, Yamazaki M, Watanabe S, Hasegawa H, Odagiri T, 2019. Human-to-Human transmission of influenza A(H3N2) virus with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir, Japan, February 2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 25, 2108–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashita E, Morita H, Ogawa R, Nakamura K, Fujisaki S, Shirakura M, Kuwahara T, Kishida N, Watanabe S, Odagiri T, 2018. Susceptibility of influenza viruses to the novel cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Noshi T, Omoto S, Sato A, Shishido T, Matsuno K, Okamatsu M, Krauss S, Webby RJ, Sakoda Y, Kida H, 2024. The impact of PA/I38 substitutions and PA polymorphisms on the susceptibility of zoonotic influenza A viruses to baloxavir. Arch. Virol. 169, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WL, Lau SY, Chen Y, Wang G, Mok BW, Wen X, Wang P, Song W, Lin T, Chan KH, Yuen KY, Chen H, 2012. The 2008–2009 H1N1 influenza virus exhibits reduced susceptibility to antibody inhibition: implications for the prevalence of oseltamivir resistant variant viruses. Antivir. Res. 93, 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Xu C, Zhang N, Wan Y, Wu Y, Meng F, Chen Y, Yang H, Liu L, Qiao C, Chen H, 2024. Two amino acid residues in the N-terminal region of the polymerase acidic protein determine the virulence of Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza viruses in mice. J. Virol. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Yen HL, 2016. Current and novel antiviral strategies for influenza infection. Curr. Opin. Virol. 18, 126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.