Abstract

Intramolecular epistasis is increasingly recognized as a key factor shaping patterns of evolutionary rate variation among protein sites and constraining adaptive evolution. While genome-wide analyses have revealed that intramolecular epistatic interactions can drive the spatial clustering of amino acid substitutions, direct empirical evidence for such interactions and their evolutionary consequences remains limited. Using a population genetic screen for spatially-clustered and lineage-specific adaptive amino acid substitutions in Drosophila proteins, we systematically identify experimentally tractable candidates for functional analysis. As proof of concept, we focus on the Trio protein, a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor that exhibits three spatially-clustered adaptive amino acid substitutions in the D. melanogaster lineage. By systematically reconstructing evolutionary intermediates in vivo using genome editing, we find that all possible intermediate states exhibit reduced viability and/or locomotor defects, providing strong evidence for epistatic constraints on evolutionary trajectories. Notably, these deleterious effects are recessive, suggesting that intermediate combinations of epistatically interacting amino acid substitutions can accumulate in heterozygotes prior to fixation, thereby circumventing apparent constraints imposed by maladaptive intermediate states. Together, these findings provide a rare empirical view of the fitness landscape shaped by intramolecular epistasis and establish a framework for investigating the constraints on adaptive protein evolution in diploid multicellular organisms.

Author Summary

Proteins fold into three-dimensional structures that are essential for their function. Because these structures depend on interactions among amino acids, the fitness effect of a mutation at one site can depend on the amino acid states at other sites. Such dependencies constrain the paths that protein evolution can take, whether evolution proceeds neutrally or adaptively. Although intramolecular epistasis has been demonstrated in microbial systems and in vitro, direct experimental evidence for such constraints in diploid multicellular organisms in vivo is rare. Here, we identify Drosophila proteins that exhibit clusters of closely-spaced adaptive amino acid substitutions and focus experimental analyses on one example, Trio, a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Using genome editing to reconstruct evolutionary intermediates in the D. melanogaster lineage, we find that all intermediate versions of Trio reduce viability or impair locomotor function. Importantly, these harmful effects are recessive, suggesting that they could be masked when paired with an ancestral version of the protein. This implies that individual amino acid changes may persist in heterozygotes within populations and later combine to contribute to adaptation. If the recessivity of deleterious intermediates along adaptive evolutionary paths proves to be widespread, it could have important implications for our mechanistic understanding of adaptive protein evolution.

Introduction

The rate of protein evolution varies substantially among species, among proteins and among sites within proteins. This rate variation has historically been interpreted in terms of “neutral”, or “nearly neutral” models of protein evolution, which depend on the proportion of newly arising amino acid altering mutations that are neutral with respect to protein function or effectively neutral due to genetic drift (1,2). While nearly neutral models can account for several important aspects of protein evolution (3), a debate raged for decades about the relative contribution of positive selection to protein evolution. The development and application of the McDonald-Kreitman test (4) and similar frameworks (5-7) suggested that protein divergence is well in excess of that predicted under neutral models of protein evolution in Drosophila and other species (5,8-13). While the McDonald-Kreitman and similar tests suffer from uncertainty of the population size over time (14,15), amino acid substitutions also exhibit genetic hitchhiking signatures at closely linked neutral sites, confirming an important role for positive selection in protein evolution (11,16-20).

Evolutionary rate variation within proteins is primarily believed to arise from differences in selective constraint, reflecting the need to maintain the integrity of specific protein domains and their functions (21-23). However, since positive selection also contributes substantially to protein divergence, this raises the possibility that clustered substitutions may sometimes result from repeated rounds of adaptive substitution in particular functional regions, or from the cofixation of nearly neutral variants through genetic hitchhiking. Indeed, several studies have reported that positively selected amino acid substitutions tend to occur in close proximity within protein structures (24-29).

Beyond selection acting independently on individual sites, interactions among amino acids — intramolecular epistasis — are also expected to play an important role in shaping protein evolution. Because protein structure and function depend on networks of residue interactions, the fitness effects of new amino acid altering mutations are expected to depend on the history of substitutions at interacting sites. This principle was first formalized in the covarion model, which proposed that only a subset of codons is free to vary at any given time and that this set shifts as substitutions occur (30-32). Since spatially proximate amino acids are more likely to directly interact, substitutions that compensate or permit one another are expected to co-occur closely in sequence space or atomic distance in folded proteins. Consistent with this prediction, recent studies have revealed that spatially clustered amino acid substitutions exhibit characteristic signatures of epistasis and compensatory evolution (33-38). Together, these findings suggest that intramolecular epistasis not only contributes to variation in evolutionary rate but also leaves a distinct spatial footprint in the form of clustered substitutions.

Experimental work has further confirmed the central role of intramolecular epistasis in protein evolution. A landmark study by Weinreich et al. (2006) showed that interactions among five mutations in β-lactamase dramatically constrained the number of traversable evolutionary paths to antibiotic resistance (39). Similarly, Ortlund et al. (2007) demonstrated that the glucocorticoid receptor evolved new hormone specificity in vertebrates via “stability-mediated” epistasis, in which nearly-neutral permissive mutations fixed stochastically and stabilized local structures, enabling subsequent adaptive substitutions to fix (40). Later studies using ancestral protein reconstruction, experimental evolution, and large-scale mutational scans have confirmed that epistatic interactions can strongly influence evolutionary trajectories (41-48). Furthermore, a few studies provide evidence of epistatic substitutions occurring in close spatial proximity, echoing the clustering patterns predicted from statistical analyses. For example, compensatory mutations have been observed near adaptive substitutions conferring toxin resistance in the poison frog nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (49), and similar patterns appear along the evolution of vertebrate proteins like p53, hemoglobin, lysozyme and Na+,K+-ATPase (50-54).

This experimental work has been instrumental in demonstrating the pervasiveness of epistasis and in revealing key principles of higher-order and global epistasis governing fitness landscapes. However, most of these studies have explored epistatic dynamics in the context of protein activity and stability in vitro (41-44,55,56), or microbial fitness in vivo (46-48). Consequently, a substantial gap still exists in our understanding of how interacting substitutions accumulate in diploid multicellular organisms where dominance, pleiotropy, and interactions across multiple phenotypic levels may also strongly influence evolutionary outcomes.

To our knowledge, Na+,K+-ATPase (NKA) resistance to cardiotonic steroids (CTS) in insects is the only case where epistasis in protein adaptation has been directly demonstrated in vivo in a multicellular organism (57-59). In CTS-adapted insects, adaptation frequently targets a highly conserved domain of the NKA alpha-subunit. The most common resistance-conferring substitutions—at positions 111 and 122—almost always occur after a permissive substitution at position 119 (A119S), which reduces the negative pleiotropic effects of these resistance mutations (57,58). Moreover, in vivo engineering of firefly CTS-resistance substitutions into Drosophila revealed similar deleterious pleiotropic effects, which were alleviated by additional background substitutions that occur within a span of 12 amino acid residues, but are not directly related to CTS resistance (59). Further, it was shown that the deleterious effects of CTS resistance-conferring substitutions appear to be recessive, potentially explaining how they might persist in populations long enough to allow secondary compensating substitutions to arise and enable their fixation. This work highlighted the use of in vivo models in revealing pleiotropic effects on higher order phenotypes that are more closely related to organismal fitness (e.g viability, fertility, and behavior) and would be missed in in vitro assays.

The case of CTS-resistant NKAs is a striking example of the role of epistasis in protein adaptation, but it remains unclear how broadly these findings apply to other proteins. To better understand how pleiotropy, epistasis, and dominance shape protein evolution during adaptation, new diploid in vivo models are needed. To this end, we systematically searched the Drosophila melanogaster genome for proteins that, like NKA, are highly conserved yet contain lineage-specific clusters of positively-selected amino acid substitutions. As a case study, we focus on one such cluster in the highly-conserved protein Trio, a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor involved in signalling pathways that regulate several important developmental processes. Using scarless CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, we engineered Drosophila strains carrying all possible intermediate combinations of substitutions in this cluster, enabling us to dissect the epistatic and dominance interactions involved.

Results

To identify candidate clusters under selection in D. melanogaster, we applied the Model-Averaged Site Selection with Poisson Random Field (MASS-PRF; (26)). MASS-PRF estimates a site-by-site scaled selection coefficient (γ = 2Ns) based on polymorphism and divergence clustering models. While the McDonald-Kreitman test is typically applied to whole proteins, MASS-PRF is designed to quantify variation in intensities of selection across a protein sequence, highlighting potentially localized targets of adaptive protein evolution. Applying this approach to 9137 proteins, we were able to identify 919 proteins containing at least one cluster of adaptive substitutions specific to the D. melanogaster lineage (Fig1, Fig S1, See Methods). The identification of spatially-clustered adaptive amino acid substitutions provides the opportunity to investigate potential epistatic interactions among individual substitutions within such clusters. We estimated that 679 proteins contain experimentally tractable clusters consisting of 2 or 3 substitutions located less than 20 amino acids away from each other.

Figure 1. Examples of Drosophila proteins exhibiting lineage-specific clusters of adaptive amino acid substitutions.

Plotted are profiles of selection intensity (γ = 2Ns) across four D. melanogaster proteins inferred with MASS-PRF (26). The black line corresponds to the model-averaged γ and the grey areas indicate 95% model uncertainty interval. Red lines indicate regions for which the 95% lower bound of γ > 4, which corresponds to a false positive rate of <0.1 (see Methods). Protein structure models are represented below each selection intensity plot. Functional domains are represented by colored boxes with their names in black. Lineage-specific amino acid substitutions are represented by dark gray dots and red for the cluster of interest (D. melanogaster above and D. simulans below, respectively). AlphaFold predictions of the 3D structure of the D. melanogaster proteins are represented below individual plots. The prediction has been superimposed with the crystallized structures of the homologous proteins (transparent) with ligands and in oligomerized form, when available. The positions of clustered adaptive amino acid substitutions are highlighted with red arrows. (A) Trio, a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor. The AlphaFold prediction of the first DH-PH domain of Trio is represented in green and is superimposed onto the human Trio DH-PH structure (transparent green) in complex with Rac1 (blue) (PDB 7SJ4, (67)). (B) Fragile X messenger ribonucleoprotein 1 (Fmr1). (C) CG3544, a xylulokinase. The AlphaFold prediction is represented in green and is superimposed on the xylulokinase structure of Chromobacterium violaceum (transparent orange and green) in complex with ADP (pink) (PDB 3KZB). (D) Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Pgd). The AlphaFold structure prediction is represented in green and is superimposed onto the dimerized structure of the human Pgd (transparent orange and green) in complex with NADP (pink) (PDB 2JKV).

As proof of concept, we decided to focus on the identified cluster of amino acid substitutions in the protein Trio (Fig 1A) as a tractable example. Trio is a Rho-guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that regulates several signaling pathways involved in functions such as neuronal migration, axonal outgrowth, axon guidance, and synaptogenesis in D. melanogaster (60,61), C. elegans (62) and in humans (63,64). Missense and nonsense mutations in trio can cause neurodevelopmental diseases such as intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders in humans (63). In D. melanogaster, trio mutants show specific neurodevelopmental disorders resulting in locomotion behavior, leg and wing formation defects but also more general phenotypes such as prepupal lethality and sterility (65,66).

The D. melanogaster and D. simulans Trio proteins differ by 11 amino acid substitutions, six of which occur along the D. melanogaster lineage (Fig 1A). One cluster of three amino acid substitutions (V1315A; N1318S; R1335K), exhibiting lineage-specific positive selection in D. melanogaster, is located in the first GTPase binding domain DH-PH of the protein and constitute the only amino acid changes observed across the D. melanogaster–D. yakuba species group in this domain (67,68) (Fig 1A; Fig S2). These three substitutions appear to be fixed since these sites are monomorphic among 960 wild-derived D. melanogaster genome sequences from 30 populations worldwide (69). The amino acid substitutions in this cluster appear to be relatively conservative, preserving both polarity and charge properties (Fig S2), though there is a trend towards incorporation of smaller functional groups. Prediction tools assessing the impact of single substitutions on protein stability did not identify any substitutions predicted to strongly destabilize the DH-PH domain, with all predicted ΔΔG values ranging between −1 and +1 kcal/mol (Table S1).

Using a scarless CRISPR-cas9/piggyBAC genome editing approach (see Methods), we created D. melanogaster strains representing all possible combinations of this cluster of adaptive substitutions in the Trio protein from the ancestral state “VNR” (1315 Val; 1318 Asn; 1335 Arg) to “ASK” (1315 Ala; 1318 Ser; 1335 Lys), corresponding to the current state in D. melanogaster (Fig 2C). To avoid effects due to variation in the genomic background,we homogenized genomic backgrounds of all the lines by crossing to well-characterized inbred strains (see Methods and Fig S3).

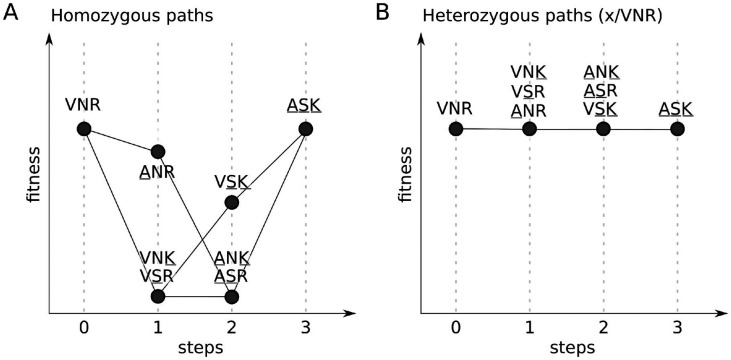

Figure 2. Evolutionary intermediates in the path from ancestral to extant D. melanogaster Trio sequences exhibit recessive deficits in fitness related phenotypes.

(A) Viability of homozygous and heterozygous first instar larvae, pupae and adults. Plotted is the ratio of the observed proportion of YFP-individuals relative to expected proportions (see Methods). Asterisks indicate adjusted p-values (*** p<0.001; ** p<0.01; * p<0.05) determined by Fisher’s Exact tests. (B) Locomotion defects in homozygous and heterozygous individuals. A locomotion index (y-axis) is measured using a negative geotaxis assay and normalized relative to the ASK/ASK genotype (see Methods). Each dot represents a group of 5-10 males. The red dot and whiskers represent the mean and standard error, respectively. Two strains that share a letter are not significantly different from each other (Kruskall-Wallis followed by Dunn test, p<0.05). (C) Diagram representing all available genetic paths from the ancestral haplotype VNR to the extant D. melanogaster haplotype ASK. Colors of the circle represent the fitness of each haplotype based on viability and locomotion results.

To identify potential epistatic interactions among the three substitutions of this cluster, we first investigated homozygous effects of substitutions at these three sites on two fitness-related traits (viability and locomotion). Interestingly, most of the intermediate haplotypes showed severe defects in larval and adult viability. In particular, VSR, VNK, ASR and ANK flies are homozygous lethal and most individuals do not reach pupal stage (Fig 2A). For VSR, the few homozygous individuals that do reach adulthood are sterile (6 males and 1 female out of 113 adults). Only ANR, VSK and the ancestral haplotype VNR showed viabilities similar to the current ASK haplotype of D. melanogaster. Additionally, while the intermediate haplotypes ANR and VSK did not show viability defects, they do exhibit defects in adult locomotion (Fig 2B). Thus, it appears that all three amino acid substitutions are involved in epistatic interactions, and it is apparent that all possible paths from ancestral to the current D. melanogaster state would involve transiting through a less fit intermediate state (Fig 2C).

Motivated by these findings, we next asked about the dominance of the deleterious effects associated with intermediate states. To examine dominance effects, we created heterozygotes (x/VNR) carrying one intermediate state (x) and one ancestral haplotype (VNR). We found that all intermediate states have viabilities that are not distinguishable from that of the homozygous VNR or ASK haplotypes (Fig 2A). Similarly, all the intermediate haplotypes lacked locomotion defects when heterozygous (Fig 2B). Together, these results suggest that all deleterious effects associated with intermediate states are recessive. The finding that the deleterious effects of substitutions are recessive has important implications for how we expect this cluster of adaptive substitutions to have become established in the D. melanogaster lineage. Notably, all paths involving sequential substitution of amino acid substitutions would be deleterious, however, each of these substitutions may have persisted as polymorphisms in the population for some time, assembled into a favorable haplotype and fixed concomitantly (Fig 3).

Figure 3. Adaptive paths are only accessible via heterozygous states.

Shown is a schematic representation of the fitness landscape for the adaptive amino acid substitutions in Trio. The x-axis represents the number of mutational steps from the ancestral haplotype (VNR) to the extant D. melanogaster haplotype (ASK). The y-axis represents fitness based on viability and locomotion phenotypes of each haplotype in (A) homozygous D. melanogaster flies or (B) heterozygous flies carrying one ancestral VNR haplotype.

As this cluster of substitutions is inferred to be positively selected (Fig 1A), we might expect the ASK haplotype to confer a fitness advantage relative to the ancestral haplotype VNR in D. melanogaster flies. However, the viability and locomotion phenotypes of homozygous VNR flies were not distinguishable from ASK flies. We also find that levels of fertility of the VNR and ASK strains are not distinguishable (Fig S4). This implies that either the ASK haplotype is neutral relative to the VNR haplotype, a fitness benefit occurs for a phenotype (or in an environment) that we have not investigated, or that ASK may have had a fitness advantage in the context of the ancestral D. melanogaster genomic background.

Discussion

Adaptive protein evolution is widespread in plant and animal genomes and has a major impact on levels of genome-wide variability. Most inferences about this process rest on the assumptions that amino acid substitutions act independently and that the intensity of selection on them remains constant. Increasing evidence, however, suggests that interactions among substitutions—especially those in close physical proximity—may be common. These interactions raise an unresolved question: are clusters of closely linked amino acid substitutions, whether adaptive or not, typically fixed sequentially or simultaneously within a species? Despite its importance, direct empirical evidence for such epistatic interactions among spatially-clustered substitutions remains scarce, particularly in multicellular eukaryotes, where most reports have been anecdotal.

To address this gap, we systematically searched for proteins with experimentally tractable clusters of adaptive amino acid substitutions and identified Trio, a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor, as a promising test case. Our analyses suggest that a cluster of three lineage-specific adaptive amino acid substitutions in Trio are unlikely to have fixed sequentially along the Drosophila melanogaster lineage. Instead, negative epistatic interactions among residues, together with the recessive deleterious effects of the derived variants, make it more likely that all three substitutions fixed together as a single haplotype. This work provides one of the few direct demonstrations that spatially-clustered adaptive substitutions in a multicellular eukaryote can interact epistatically and have measurable effects on whole-organism phenotypes relevant to fitness.

The utility of in vivo studies in Drosophila

Most experimental studies of epistasis have been performed in vitro. These approaches are powerful because they allow systematic exploration of epistatic interactions within a protein. Deep mutational scanning can be applied efficiently to map the interactions among different sites of a protein and reconstruct the full fitness landscape of that protein (44,55,56). Such studies have been invaluable for uncovering principles of protein structure–function relationships and for providing quantitative descriptions of higher-order epistasis. However, the phenotypes measured in vitro—such as enzymatic activity or ligand binding—are tied to the specific function of the protein being studied and may not accurately reflect the overall organismal fitness. Moreover, many proteins have functions that are not amenable to straightforward biochemical assays.

In contrast, in vivo studies – most of which have been carried out in microbial systems (46-48) – provide the opportunity to measure phenotypes more directly relatable to fitness (for example, growth rates). They also provide a way to investigate amino acid substitutions in proteins that are otherwise difficult to assay biochemically, thereby broadening the range of proteins for which epistatic interactions can be experimentally explored. While the use of microbial systems continues to be important, there are key differences between microbes and multicellular diploid organisms that have important implications for the mechanistic basis for constraints on adaptation. In particular, multicellular organisms display more complex, higher-order phenotypes—such as those related to development, survival, behavior and reproduction —that in turn increase the complexity of the potential epistatic, pleiotropic and dominance dependencies of adaptive protein evolution. Our study represents one of the few to test the in vivo effects of specific adaptive amino acid substitutions on viability, fertility, and locomotion in the context of a multicellular organism. As such, it provides a framework for more systematically exploring constraints on adaptive protein evolution in the context of diploid multicellular organisms.

Implications for the dynamics of adaptation

Although intramolecular epistasis is recognized as an important factor of protein evolution (52,70,71), how groups of interacting amino acid substitutions can reach fixation in functional regions of proteins without compromising fitness remains poorly understood. In principle, epistasis can allow sets of mutations that are individually deleterious or neutral to confer a benefit when combined, yet the evolutionary paths by which such groups of substitutions become established are often opaque. A number of previous studies that have directly investigated the timing and dynamics of epistatic mutation fixation generally support a sequential fixation model (43,45,61,72,73). In such models, mutations fix in a stepwise manner, with each substitution either being neutral or slightly deleterious until the beneficial combination is assembled. This question has largely been unexplored in the context of diploid organisms where dominance relationships of alleles may also play an important role.

Here, for the cluster of three adaptive amino acid substitutions in Trio, we show that individual substitutions, as well as pairs, are deleterious when present in the homozygous state. This implies that any evolutionary trajectory involving the stepwise, sequential substitution of these amino acids would need to traverse through strongly deleterious intermediate states (Fig 3), making such paths highly unlikely. These results therefore provide strong evidence that this cluster did not arise through a process of sequential fixation. Instead, since these deleterious effects are recessive, we propose that the cluster was likely to have assembled at the polymorphic phase, with all three substitutions eventually fixing concomitantly. This scenario contrasts with previous findings in microbial protein adaptation and highlights that dominance effects may fundamentally alter the dynamics of protein evolution—whether adaptive or compensatory—in diploid eukaryotes.

The recessivity of detrimental pleiotropic effects associated with otherwise adaptive substitutions may allow them to persist until epistatic combinations restore or enhance fitness. Consistent with this view, several recent examples of adaptive protein evolution have documented dominance reversals, where adaptive mutations exhibit dominant beneficial effects but recessive pleiotropic costs. Such a pattern has been observed in the evolution of Na+,K+-ATPase resistance to cardiotonic steroids (58), GABA receptor resistance to terpenoids (74), and acetylcholinesterase resistance to organophosphates (75). The dominance of the beneficial effects associated with adaptive substitutions at Trio is not known, but given the recessivity of deleterious intermediate states, it may represent a similar example of adaptive protein evolution.

Implications for the interpretation of population genetic inferences

Over the past several decades, population genetics has undergone a paradigm shift in how we understand the role of positive selection in protein evolution and its impact on genomic variation in plants and animals (8,12). In Drosophila, estimates suggest that 50–90% of amino acid divergence exceeds neutral–deleterious model predictions and is therefore attributed to positive selection, though the exact proportion varies depending on datasets and methods (20,25,76,77). Independent support for adaptive substitutions comes from hitchhiking signatures near individual amino acid substitutions (18), but these analyses tend to yield somewhat lower estimates of the proportion of divergence that is adaptive.

If, however, epistasis among amino acid substitutions—as observed for Trio—is common in protein evolution, then the McDonald–Kreitman framework may overestimate the proportion of adaptive divergence (78). This is because the framework assumes independence among sites and a constant direction and strength of selection over time, both of which are violated when substitutions interact epistatically. Although this issue has been raised conceptually, the consequences of pervasive epistasis for interpreting McDonald–Kreitman results remain largely unexplored.

More broadly, widespread non-independence among amino acid substitutions could alter how we interpret their effects on genome-wide diversity. For example, if several closely linked substitutions fix simultaneously rather than sequentially, the apparent average strength of selection per substitution inferred from local reductions in linked diversity would be underestimated, since its impact would be distributed across multiple fixed sites. How such non-independence—particularly in light of the dominance and epistasis uncovered in the case of Trio—affects inferences of population genetic parameters is an important open question for future research.

Conclusions

By studying a cluster of adaptive amino acid substitutions in the D. melanogaster protein Trio, we uncovered strong epistatic interactions among residues of this cluster. Because these substitutions exhibit recessive deleterious effects, they are more likely to have persisted at low frequencies in the population as polymorphisms before combining into a beneficial haplotype that eventually became fixed in the species. This phenomenon may be common in adaptive protein evolution and has important implications for how we interpret its associated population genetic signals. This case study lays the groundwork for more systematic in vivo studies of adaptive amino acid substitution, where the fitness effects of mutations can be measured at multiple levels, including at the whole-organism phenotypes related to fitness. Such studies will help clarify how epistasis, pleiotropy, and dominance interact to shape protein evolution, deepening our understanding of the evolutionary constraints that govern adaptive trajectories in multicellular diploid organisms.

Methods

Identification of adaptive clusters

We created alignments of orthologous proteins using D. melanogaster ISO1 (GCA_000001215.4), D. simulans w501 (GCA_016746395.2), D. yakuba NY73PB (GCA_016746365.2), D. santomea STO CAGO 1482 (GCA_016746245.2) and D. teissieri GT53w (GCA_016746235.2) One-to-one orthologs were identified using a reciprocal best-hit exonerate approach (35,79). Predicted D. melanogaster (strain ISO1) proteins were aligned to each genome sequence to extract candidate proteins, and each extracted protein was subsequently realigned to its corresponding D. melanogaster protein. The longest predicted transcript for each protein in D. melanogaster was used to represent each protein and multispecies alignment was created using PRANK (-codon parameter, v.170427; (80)). Ancestral sequences were inferred based on this alignment and the species tree using PAML’s baseml function (v 4.9; (81)) with the following parameters: model=7, kappa=1.6, RateAncestor=2. MACSE (- max_refine_iter 1 parameter, v. 2.07; (82)) was then used to align sequences from the D. melanogaster Zambia population (n = 82; (69)) with the reconstructed D. melanogaster–D. simulans ancestral sequence.

To infer selection on protein sequences, we applied Model Averaged Site Selection via Poisson Random Field (MASS-PRF), which relies on both polymorphism and divergence data (26). In this framework, sequences from the Zambia population served as polymorphism data, while the reconstructed D. melanogaster–D. simulans ancestral sequence was used as the outgroup to quantify lineage-specific divergence. To prepare the input files required for running MASS-PRF (26), we generated consensus sequences capturing polymorphism and divergence changes for each protein, as follows. To create the polymorphism consensus sequence, monomorphic codons were replaced by “*”, synonymous codons by “S” and non-synonymous changes were replaced by “R”. To create the divergence consensus sequence, outgroup codons that were present in the ingroup sequences were replaced by “*”, outgroup codons were replaced by “S” or “R” if the ingroup codon was fixed and the outgroup codon was synonymous or non-synonymous to it respectively. If the ingroup codon was polymorphic and the outgroup codon was different from both of these, the codon was replaced by “-”. For proteins longer than 900 amino acids, Consensus sequences were split into fragments of 900 codons or smaller.

MASS-PRF was run on each consensus sequence using parameters –ic 1 –sn 82 -o 1 -r 1 - ci_r 1 -ci_m 1 -s 1 -exact 0 -mn 30000 -t 2. Out of 10573 sequences (corresponding to 9137 unique proteins), MASS-PRF ran successfully 5743 sequences (4082: too little substitution information to run; 748: out of memory). Successful runs were screened for positive selection. A site was estimated to be under positive selection if the lower 95% confidence bound for gamma > 4, which corresponds to a false positive rate <0.1 (26). Out of the 5743 successful runs (corresponding to 5355 proteins), 1144 had at least one site under positive selection and 970 more than one, with 940 forming a cluster (at least two sites less than 20 codons apart). We found that 679 proteins contain at least one potential experimentally tractable cluster. We defined a cluster as experimentally tractable if exactly 2 or 3 sites that show divergence and positive selection are less than 20 codons apart from each other.

Predicted functional domains (Fig 1 and Fig S1) were found in FlyBase.org and AlphaFold predictions are taken from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (EMBL-EBI). Superimposition of the AlphaFold prediction and the crystal structure (when available) was performed using Mol* Viewer (83). For protein stability analyses (Table S1), structures of the D. melanogaster Trio DH-PH domain, as well as the ancestral and all the intermediate versions of the domain were predicted using ColabFold v1.5.5 (AlphaFold2 using MMseqs2) (84) using default parameters. The effects of each single mutation on stability (ΔΔG) were predicted using Dynamut2 (85), ThermoNet based on Rosetta modules (86-88) and ACDC-NN (istruct function) (89).

Plasmid assembly

Genomic DNA was isolated from ywISO8 flies using a “squish prep” protocol (90). Homology arms were amplified with PCR from this genomic DNA using Q5 polymerase from NEB (Table S2). The plasmid backbone and dsRed were amplified from plasmid: pScarlessHD-DsRed, a gift from Kate O’Connor-Giles (Addgene #64703) (Table S2). The four fragments were combined at an equimolar concentration (150 fmoles each) and assembled using NEBuilder HiFi DNA assembly kit. To verify that assembly was successful, PCR was performed using primers that spanned multiple fragments. The NEBuilder HiFi DNA assembly kit result was used to transform NEB 5-alpha competent E. coli. To verify that the transformation was successful, colony PCR was performed on individual bacteria colonies using pairs of primers that spanned multiple fragments using LongAMP or regular Taq. Final plasmid assembly was verified by a Tn5 tagmentation-based Illumina sequencing protocol (91) followed by de novo assembly. Plasmids were extracted using Qiagen’s QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Starting from a base plasmid sequence representing the current D. melanogaster haplotype (ASK), we used site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) to create all possible intermediates leading back to the ancestral A1315V/S1318N/K1335R (VNR) haplotype. To do this, we used the Agilent QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit in two reactions: one containing three primers: 1) A1315V, 2) S1318N, and 3) K1335R, and one containing two primers: 1) A1315V, S1318N and 2) K1335R. The standard Agilent kit protocol was followed. First, PCR was performed without the addition of QuikSolution, as it was not necessary. This was followed by DpnI digestion (provided) and transformation into the provided competent cells. Colony PCR using Taq polymerase was performed on 48 bacterial colonies from each reaction (Table S2). Amplicons from each sample were barcoded with a unique combination of Illumina-compatible i5 and i7 adapters and sequenced to assess the presence of the desired mutations. Plasmids were extracted using the Qiagen Plasmid Midi Kit for CRISPR injection. The design for mutation 3 (K1335R) is completely scarless. All the other combinations introduce a single synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism that is naturally present within D. melanogaster populations. Plasmids were obtained for the following combinations: A1315V (VSK), A1315V/S1318N/K1335R (VNR), A1315V/S1318N (VNK), S1318N (ANK), K1335R (ASR), S1318N/K1335R (ANR). One additional haplotype, A1315V/K1335R (VSR) was generated using a second SDM reaction starting from A1315V plasmid to introduce K1335R.

CRISPR injections and post-injection processing

gRNAs were created from the shared tracrRNA and a site-specific crRNA, ordered as two separate Alt-R® CRISPR-Cas9 RNA fragments from IDT (Table S2). For each gRNA, tracrRNA and crRNA were annealed by adding 2 μl of crRNA at 100 μM, 2 μl of tracrRNA at 100μM, and 2 μl of IDT nuclease-free duplex buffer and incubating at 95°C for 5 minutes, then allowing the mixture to come to room temperature on the benchtop. gRNA was loaded into the Alt-R® S.p. Cas9 Nuclease from IDT to make the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex: First, stock Cas9 solution was diluted into an equivalent volume of IDT nuclease-free duplex solution. Then 2.68 mL of both annealed gRNAs and 1.8 mL of the diluted Cas9 protein were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. Finally, 7.5 mg of donor plasmid was added, and the volume was increased to 30 mL with water. CRISPR-cas9 injections were done in line “ywISO8” to facilitate ease of fluorescent screening. Injected flies were crossed to a double balancer line (BL#2537: w[*]; TM3, Sb[1] Ser[1]/TM6B, Tb[1]). Progeny of the crosses were screened for red fluorescent eyes and mated with siblings with the same balancer chromosomes to establish a stable line. pBac excision was performed following (92): DsRed embryos were injected with 250ng/mL phsp-pBac plasmid (93), heat shocked 1 hour after injection for 1 hour at 37 C. Injected flies were then crossed with a balancer line (Bloomington #23232: w[*]; ry[506] Dr[1]/TM6B, P{Dfd-GMR-nvYFP}4, Sb[1] Tb[1] ca[1]). Progeny of the crosses were screened for non-fluorescent eyes and sib mated to establish mutant lines.

Background homogenization

In order to fully control for genomic background effects, two balancer lines with a fully homozygous genome were created using the inbred line RAL386 (BL#28192; (72) and the chromosome balancer of respectively BL#23232 (w[*]; ry[506] Dr[1]/TM6B, P{Dfd-GMR-nvYFP}4, Sb[1] Tb[1] ca[1]) and BL#35524 (w[1118]; DCTN1-p150[1]/TM3, P{w[+mC]=sChFP}3, Sb[1]). RAL386 males were crossed with virgin females of either balancer line BL#23232 or BL#35524. An F1 male was then backcrossed with a RAL386 virgin female. Resulting fluorescent male progeny were then backcrossed to RAL386 virgin females. Several days after the crosses, the father of each cross was collected and genotyped for chromosome 2 by PCR and Sanger sequencing of a region with a known diagnostic single nucleotide polymorphism. Crosses for which the father was homozygous for RAL386 haplotype for chromosome 2 were kept (Table S2). Fluorescent virgin female progeny from this cross were then backcrossed to a RAL386 male. The balancer chromosomes in the established lines were maintained by screening for fluorescence every 2-3 weeks. Trio mutant lines and yw-ISO8 line, used as the control ASK, were crossed alternatively with the two RAL386 balancer lines following the same crosses scheme as described below so the final lines could be balanced with TM6B, P{Dfd-GMR-nvYFP}4, Sb[1] Tb[1] ca[1].

To confirm the genomic background of engineered lines, 10 female individuals were collected from each line and frozen at −20°C. Whole DNA was extracted from each fly individually using Quick-DNA 96 Kit (Zymo research). DNA from each fly from the same line was then pooled. Tn5-tagmentation libraries (Picelli et al. 2014) were prepared and indexed with one specific index for each line and enriched by 12 PCR cycles (HS One Taq, NEB). Libraries were then pooled and size selected for fragments around 500nt using AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter) following manual. The pooled libraries were then sequenced with paired-end 150nt on NovaSeq X Plus 10B Illumina 2x150 (Admera Health). Illumina adapters were trimmed using trim-galore (-q 0, -e 0.1) (v 0.6.7) and reads were aligned to the D. melanogaster reference genome (GCA_000001215.4) using bwa mem (v 0.7.17-r1188, (94)). Duplicates were marked with picard (v 2.18.29, Broad Institute) and reads were re-aligned with gatk3 (v 3.8-1-0, Broad Institute). Variants were called and pseudo references generated using samtools (v 1.6) and bcftools (v 1.9) following pipeline available on github (https://github.com/YourePrettyGood/PseudoreferencePipeline). Average pairwise divergence (Dxy) between engineered strains and RAL386, yw iso8 and RAL59 was calculated on 1 Mbp non overlapping windows using scripts available on github (https://github.com/YourePrettyGood/RandomScripts#calculatepolymorphismcpp) (Fig S3).

Drosophila rearing

All fly strains were reared in bottles or vials at 21°C, 50% in day-night cycle of 12hr-12hr on fly food containing agar (0.56%), cornmeal (6.71%), inactivated yeast (1.59%), soy flour (0.92%), corn syrup (7.0%), propionic acid (0.44%), and Tegosept (0.15%) (LabExpress).

Viability assays

Viability of homozygous strains was measured as the relative survival of homozygous YFP-progeny relative to YFP+ progeny produced by parents balanced with TM6B, P{Dfd-GMR-nvYFP}4, Sb[1] Tb[1] ca[1]. For 1st instar larva, virgin males and females [YFP+, Sb+, Tb+] were crossed and allowed to lay eggs on grape-juice agar plates with yeast paste for 24hr. After 48hr, the yeast paste was washed out through a cell strainer to collect and count fluorescent and non-fluorescent 1st instar larvae. For pupal and adult stage, females were allowed to lay eggs on regular fly food vials for 7 days. [Tb+] and [Tb−] pupae were counted after about 10 days. [Sb+] and [Sb−] adults were counted after about 20 days. We measured the viability of heterozygous individuals the same way except that homozygous VNR virgin females were crossed to males balanced with TM6B, P{Dfd-GMR-nvYFP}4, Sb[1] Tb[1] ca[1]. 60 to 300 larvae, 100 to 200 pupae and 100 to 150 adults were counted for each engineered strain. For VSR, we obtained 6 adult homozygous males and 1 adult homozygous female. To estimate the fertility of those homozygous adult individuals, males were crossed individually with one homozygous VNR virgin female and the female was crossed with one heterozygous VSR male. No progeny was observed after 21 days.

Locomotion performance assay.

We quantified locomotor performance by quantifying startle-induced negative geotaxis, an innate behavior where flies tend to climb against gravity after being mechanically agitated (95). Ten 1-day-old males were grouped with ten females into vials for 7-10 days. Before the assay, the males were transferred into ethanol-cleaned assay tubes, consisting of two tubes attached with tapes with a line set at 4.5 cm from the bottom of the tube. Flies were let to recover for 40 to 60 min before the start of the experiment. The assay tube was tapped 5 times on a fly pad so that all flies fell to the bottom of the tube, and the flies that reached the line in the following 10 sec were counted. Each group of flies were assayed three times, with 5 min recovery between each time, the average of the three replicates was used. The same assay tubes were then assayed the same way after 10 min recovery but counting flies that reached the line in the following 5 sec instead of 10. Four to 14 replicates were performed for each haplotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks to N. Okami for help with fly stocks and K. O’Connor-Giles for sharing reagents. Thanks to the Andolfatto, Przeworski and Sella labs for useful comments. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health R01 GM115523 to P.A.

Data availability

Raw data for functional assays and MASS-PRF pipeline and results have been deposited to Dryad: DOI XXX.

References

- 1.Kimura M. Evolutionary Rate at the Molecular Level. Nature. 1968. Feb;217(5129):624–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohta T. Slightly Deleterious Mutant Substitutions in Evolution. Nature. 1973. Nov;246(5428):96–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright SI, Andolfatto P. The Impact of Natural Selection on the Genome: Emerging Patterns in Drosophila and Arabidopsis. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2008;39:193–213. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351(6328):652–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fay JC, Wyckoff GJ, Wu CI. Testing the neutral theory of molecular evolution with genomic data from Drosophila. Nature. 2002. Feb 28;415(6875):1024–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith NGC, Eyre-Walker A. Adaptive protein evolution in Drosophila. Nature. 2002. Feb;415(6875):1022–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawyer SA, Kulathinal RJ, Bustamante CD, Hartl DL. Bayesian analysis suggests that most amino acid replacements in Drosophila are driven by positive selection. J Mol Evol. 2003;57 Suppl 1:S154–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sella G, Petrov DA, Przeworski M, Andolfatto P. Pervasive Natural Selection in the Drosophila Genome? PLOS Genet. 2009. June 5;5(6):e1000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slotte T, Foxe JP, Hazzouri KM, Wright SI. Genome-wide evidence for efficient positive and purifying selection in Capsella grandiflora, a plant species with a large effective population size. Mol Biol Evol. 2010. Aug;27(8):1813–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlesworth J, Eyre-Walker A. The rate of adaptive evolution in enteric bacteria. Mol Biol Evol. 2006. July;23(7):1348–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booker T, Keightley P. Understanding the Factors That Shape Patterns of Nucleotide Diversity in the House Mouse Genome. Mol Biol Evol. 2018. Oct 8;35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booker TR, Jackson BC, Keightley PD. Detecting positive selection in the genome. BMC Biol. 2017. Oct 30;15(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galtier N. Adaptive Protein Evolution in Animals and the Effective Population Size Hypothesis. PLOS Genet. 2016. Jan 11;12(1):e1005774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eyre-Walker A. Changing Effective Population Size and the McDonald-Kreitman Test. Genetics. 2002. Dec 1;162(4):2017–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soni V, Moutinho AF, Eyre-Walker A. Changing Population Size in McDonald–Kreitman Style Analyses: Artifactual Correlations and Adaptive Evolution between Humans and Chimpanzees. Genome Biol Evol. 2022. Feb 10;14(2):evac022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andolfatto P. Hitchhiking effects of recurrent beneficial amino acid substitutions in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Res. 2007. Dec;17(12):1755–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macpherson JM, Sella G, Davis JC, Petrov DA. Genomewide Spatial Correspondence Between Nonsynonymous Divergence and Neutral Polymorphism Reveals Extensive Adaptation in Drosophila. Genetics. 2007. Dec 1;177(4):2083–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elyashiv E, Sattath S, Hu TT, Strutsovsky A, McVicker G, Andolfatto P, et al. A Genomic Map of the Effects of Linked Selection in Drosophila. PLOS Genet. 2016. Aug 18;12(8):e1006130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang YY, Shi Y, Yuan S, Zhou BF, Chen XY, An QQ, et al. Linked selection shapes the landscape of genomic variation in three oak species. New Phytol. 2022. Jan;233(1):555–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williamson R, Josephs E, Platts A, Hazzouri K, Haudry A, Blanchette M, et al. Evidence for Widespread Positive and Negative Selection in Coding and Conserved Noncoding Regions of Capsella grandiflora. PLoS Genet. 2014. Sept 1;10:e1004622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Echave J, Spielman SJ, Wilke CO. Causes of evolutionary rate variation among protein sites. Nat Rev Genet. 2016. Feb;17(2):109–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shih CH, Chang CM, Lin YS, Lo WC, Hwang JK. Evolutionary information hidden in a single protein structure. Proteins. 2012. June;80(6):1647–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nevin Gerek Z, Kumar S, Banu Ozkan S. Structural dynamics flexibility informs function and evolution at a proteome scale. Evol Appl. 2013;6(3):423–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridout KE, Dixon CJ, Filatov DA. Positive Selection Differs between Protein Secondary Structure Elements in Drosophila. Genome Biol Evol. 2010. Jan 1;2:166–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson DJ, Hernandez RD, Andolfatto P, Przeworski M. A Population Genetics-Phylogenetics Approach to Inferring Natural Selection in Coding Sequences. Nachman MW, editor. PLoS Genet. 2011. Dec 1;7(12):e1002395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao ZM, Campbell MC, Li N, Lee DSW, Zhang Z, Townsend JP. Detection of Regional Variation in Selection Intensity within Protein-Coding Genes Using DNA Sequence Polymorphism and Divergence. Mol Biol Evol. 2017. Nov 1;34(11):3006–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams J, Mansfield MJ, Richard DJ, Doxey AC. Lineage-specific mutational clustering in protein structures predicts evolutionary shifts in function. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2017. May 1;33(9):1338–45. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slodkowicz G, Goldman N. Integrated structural and evolutionary analysis reveals common mechanisms underlying adaptive evolution in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020. Mar 17;117(11):5977–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFerrin LG, Stone EA. The non-random clustering of non-synonymous substitutions and its relationship to evolutionary rate. BMC Genomics. 2011. Aug 16;12:415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitch WM. Rate of change of concomitantly variable codons. J Mol Evol. 1971. Mar 1;1(1):84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fitch WM, Markowitz E. An improved method for determining codon variability in a gene and its application to the rate of fixation of mutations in evolution. Biochem Genet. 1970. Oct;4(5):579–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyamoto MM, Fitch WM. Testing the covarion hypothesis of molecular evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1995. May 1;12(3):503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis BH, Poon AFY, Whitlock MC. Compensatory mutations are repeatable and clustered within proteins. Proc Biol Sci. 2009. May 1;276(1663):1823–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callahan B, Neher RA, Bachtrog D, Andolfatto P, Shraiman BI. Correlated Evolution of Nearby Residues in Drosophilid Proteins. PLOS Genet. 2011. Feb 24;7(2):e1001315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taverner AM, Blaine LJ, Andolfatto P. Epistasis and physico-chemical constraints contribute to spatial clustering of amino acid substitutions in protein evolution [Internet]. bioRxiv; 2020. [cited 2024 Nov 1]. p. 2020.08.05.237594. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.05.237594v1 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaurasia S, Dutheil JY. The Structural Determinants of Intra-Protein Compensatory Substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 2022. Apr 1;39(4):msac063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stolyarova AV, Neretina TV, Zvyagina EA, Fedotova AV, Kondrashov AS, Bazykin GA. eLife. eLife Sciences Publications Limited; 2022. [cited 2025 June 24]. Complex fitness landscape shapes variation in a hyperpolymorphic species. Available from: https://elifesciences.org/articles/76073 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ragsdale AP. Local fitness and epistatic effects lead to distinct patterns of linkage disequilibrium in protein-coding genes. Genetics. 2022. Aug 1;221(4):iyac097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinreich DM, Delaney NF, DePristo MA, Hartl DL. Darwinian Evolution Can Follow Only Very Few Mutational Paths to Fitter Proteins. Science. 2006. Apr 7;312(5770):111–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ortlund EA, Bridgham JT, Redinbo MR, Thornton JW. Crystal structure of an ancient protein: evolution by conformational epistasis. Science. 2007. Sept 14;317(5844):1544–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biswas A, Haldane A, Arnold E, Levy RM. Epistasis and entrenchment of drug resistance in HIV-1 subtype B. eLife. 2019;8:e50524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hochberg GK, Liu Y, Marklund EG, Metzger BPH, Laganowsky A, Thornton JW. A hydrophobic ratchet entrenches molecular complexes. Nature. 2020. Dec 9;588(7838):503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gong LI, Suchard MA, Bloom JD. Stability-mediated epistasis constrains the evolution of an influenza protein. Pascual M, editor. eLife. 2013. May 14;2:e00631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarkisyan KS, Bolotin DA, Meer MV, Usmanova DR, Mishin AS, Sharonov GV, et al. Local fitness landscape of the green fluorescent protein. Nature. 2016. May;533(7603):397–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harms MJ, Thornton JW. Historical contingency and its biophysical basis in glucocorticoid receptor evolution. Nature. 2014. Aug 14;512(7513):203–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papkou A, Garcia-Pastor L, Escudero JA, Wagner A. A rugged yet easily navigable fitness landscape. Science. 2023. Nov 24;382(6673):eadh3860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Good BH, McDonald MJ, Barrick JE, Lenski RE, Desai MM. The dynamics of molecular evolution over 60,000 generations. Nature. 2017. Nov;551(7678):45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson MS, Reddy G, Desai MM. Epistasis and evolution: recent advances and an outlook for prediction. BMC Biol. 2023. May 24;21(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarvin RD, Borghese CM, Sachs W, Santos JC, Lu Y, O’Connell LA, et al. Interacting amino acid replacements allow poison frogs to evolve epibatidine resistance. Science. 2017. Sept 22;357(6357):1261–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mateu MG, Fersht AR. Mutually compensatory mutations during evolution of the tetramerization domain of tumor suppressor p53 lead to impaired hetero-oligomerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999. Mar 30;96(7):3595–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber RE, Fago A, Malte H, Storz JF, Gorr TA. Lack of conventional oxygen-linked proton and anion binding sites does not impair allosteric regulation of oxygen binding in dwarf caiman hemoglobin. Am J Physiol-Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013. Aug;305(3):R300–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Storz JF. Compensatory mutations and epistasis for protein function. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2018. June 1;50:18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohammadi S, Yang L, Harpak A, Herrera-Álvarez S, Rodríguez-Ordoñez M del P, Peng J, et al. Concerted evolution reveals co-adapted amino acid substitutions in Na+K+-ATPase of frogs that prey on toxic toads. Curr Biol. 2021. June 21;31(12):2530–2538.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mohammadi S, Herrera-Álvarez S, Yang L, Rodríguez-Ordoñez MDP, Zhang K, Storz JF, et al. Constraints on the evolution of toxin-resistant Na,K-ATPases have limited dependence on sequence divergence. PLoS Genet. 2022;18(8):e1010323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Starr TN, Thornton JW. Epistasis in protein evolution. Protein Sci Publ Protein Soc. 2016. July;25(7):1204–18. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olson CA, Wu NC, Sun R. A comprehensive biophysical description of pairwise epistasis throughout an entire protein domain. Curr Biol CB. 2014. Nov 17;24(22):2643–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karageorgi M, Groen SC, Sumbul F, Pelaez JN, Verster KI, Aguilar JM, et al. Genome editing retraces the evolution of toxin resistance in the monarch butterfly. Nature. 2019. Oct;574(7778):409–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taverner AM, Yang L, Barile ZJ, Lin B, Peng J, Pinharanda AP, et al. eLife. eLife Sciences Publications Limited; 2019. [cited 2022 Sept 16]. Adaptive substitutions underlying cardiac glycoside insensitivity in insects exhibit epistasis in vivo. Available from: https://elifesciences.org/articles/48224/figures [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang L, Borne F, Betz A, Aardema ML, Zhen Y, Peng J, et al. Predatory fireflies and their toxic firefly prey have evolved distinct toxin resistance strategies. Curr Biol. 2023. Dec 4;33(23):5160–5168.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bateman J, Shu H, Van Vactor D. The Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor Trio Mediates Axonal Development in the Drosophila Embryo. Neuron. 2000. Apr 1;26(1):93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iyer SC, Wang D, Iyer EPR, Trunnell SA, Meduri R, Shinwari R, et al. The RhoGEF Trio Functions in Sculpting Class Specific Dendrite Morphogenesis in Drosophila Sensory Neurons. PLOS ONE. 2012. Mar 19;7(3):e33634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu YC, Cheng TW, Lee MC, Weng NY. Distinct rac activation pathways control Caenorhabditis elegans cell migration and axon outgrowth. Dev Biol. 2002. Oct 1;250(1):145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barbosa S, Greville-Heygate S, Bonnet M, Godwin A, Fagotto-Kaufmann C, Kajava AV, et al. Opposite Modulation of RAC1 by Mutations in TRIO Is Associated with Distinct, Domain-Specific Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2020. Mar 5;106(3):338–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Linseman DA, Loucks FA. Diverse roles of Rho family GTPases in neuronal development, survival, and death. Front Biosci J Virtual Libr. 2008. Jan 1;13:657–76. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Awasaki T, Saito M, Sone M, Suzuki E, Sakai R, Ito K, et al. The Drosophila trio plays an essential role in patterning of axons by regulating their directional extension. Neuron. 2000. Apr;26(1):119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liebl EC, Forsthoefel DJ, Franco LS, Sample SH, Hess JE, Cowger JA, et al. Dosage-sensitive, reciprocal genetic interactions between the Abl tyrosine kinase and the putative GEF trio reveal trio’s role in axon pathfinding. Neuron. 2000. Apr;26(1):107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bandekar SJ, Arang N, Tully ES, Tang BA, Barton BL, Li S, et al. Structure of the C-terminal guanine nucleotide exchange factor module of Trio in an autoinhibited conformation reveals its oncogenic potential. Sci Signal. 2019. Feb 19;12(569):eaav2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chhatriwala MK, Betts L, Worthylake DK, Sondek J. The DH and PH domains of Trio coordinately engage Rho GTPases for their efficient activation. J Mol Biol. 2007. May 18;368(5):1307–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lack JB, Cardeno CM, Crepeau MW, Taylor W, Corbett-Detig RB, Stevens KA, et al. The Drosophila genome nexus: a population genomic resource of 623 Drosophila melanogaster genomes, including 197 from a single ancestral range population. Genetics. 2015;199(4):1229–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lunzer M, Golding GB, Dean AM. Pervasive Cryptic Epistasis in Molecular Evolution. PLOS Genet. 2010. Oct 21;6(10):e1001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riffis M, Saclier N, Galtier N. Compensatory evolution following deleterious episodes of GC-biased gene conversion in rodents. Mol Biol Evol. 2025. July 9;msaf168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sideraki V, Huang W, Palzkill T, Gilbert HF. A secondary drug resistance mutation of TEM-1 β-lactamase that suppresses misfolding and aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001. Jan 2;98(1):283–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Levin BR, Perrot V, Walker N. Compensatory Mutations, Antibiotic Resistance and the Population Genetics of Adaptive Evolution in Bacteria. Genetics. 2000. Mar 1;154(3):985–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guo L, Qiao X, Haji D, Zhou T, Liu Z, Whiteman NK, et al. Convergent resistance to GABA receptor neurotoxins through plant–insect coevolution. Nat Ecol Evol. 2023. Sept;7(9):1444–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karageorgi M, Lyulina AS, Bitter MC, Lappo E, Greenblum SI, Mouza ZK, et al. Beneficial reversal of dominance maintains a large-effect resistance polymorphism under fluctuating insecticide selection. Nat Ecol Evol. 2025. Sept 15;1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD. Estimating the rate of adaptive molecular evolution in the presence of slightly deleterious mutations and population size change. Mol Biol Evol. 2009. Sept;26(9):2097–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Messer PW, Petrov DA. Frequent adaptation and the McDonald–Kreitman test. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013. May 21;110(21):8615–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fay JC. Weighing the evidence for adaptation at the molecular level. Trends Genet. 2011. Sept 1;27(9):343–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Slater GSC, Birney E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005. Feb 15;6(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Löytynoja A, Goldman N. A model of evolution and structure for multiple sequence alignment. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2008. Oct 7;363(1512):3913–9. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007. Aug 1;24(8):1586–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ranwez V, Harispe S, Delsuc F, Douzery EJP. MACSE: Multiple Alignment of Coding SEquences accounting for frameshifts and stop codons. PloS One. 2011;6(9):e22594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sehnal D, Bittrich S, Deshpande M, Svobodová R, Berka K, Bazgier V, et al. Mol* Viewer: modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021. July 2;49(W1):W431–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mirdita M, Schütze K, Moriwaki Y, Heo L, Ovchinnikov S, Steinegger M. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat Methods. 2022. June;19(6):679–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodrigues CHM, Pires DEV, Ascher DB. DynaMut2: Assessing changes in stability and flexibility upon single and multiple point missense mutations. Protein Sci. 2021;30(1):60–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li B, Yang YT, Capra JA, Gerstein MB. Predicting changes in protein thermodynamic stability upon point mutation with deep 3D convolutional neural networks. PLOS Comput Biol. 2020. Nov 30;16(11):e1008291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leaver-Fay A, Tyka M, Lewis SM, Lange OF, Thompson J, Jacak R, et al. Rosetta3. In: Johnson ML, Brand L, editors. Methods in Enzymology [Internet]. Academic Press; 2011. [cited 2025 Oct 7]. p. 545–74. (Computer Methods, Part C; vol. 487). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123812704000196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tyka MD, Keedy DA, André I, DiMaio F, Song Y, Richardson DC, et al. Alternate States of Proteins Revealed by Detailed Energy Landscape Mapping. J Mol Biol. 2011. Jan 14;405(2):607–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pancotti C, Benevenuta S, Repetto V, Birolo G, Capriotti E, Sanavia T, et al. A Deep-Learning Sequence-Based Method to Predict Protein Stability Changes Upon Genetic Variations. Genes. 2021. June;12(6):911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gloor GB, Preston CR, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Nassif NA, Phillis RW, Benz WK, et al. Type I repressors of P element mobility. Genetics. 1993. Sept 1;135(1):81–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Picelli S, Björklund ÅK, Reinius B, Sagasser S, Winberg G, Sandberg R. Tn5 transposase and tagmentation procedures for massively scaled sequencing projects. Genome Res. 2014. Jan 12;24(12):2033–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stern DL, Crocker J, Ding Y, Frankel N, Kappes G, Kim E, et al. Genetic and Transgenic Reagents for Drosophila simulans, D. mauritiana, D. yakuba, D. santomea, and D. virilis. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics. 2017. Apr 1;7(4):1339–47. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Handler AM, Harrell RA. Germline transformation of Drosophila melanogaster with the piggyBac transposon vector. Insect Mol Biol. 1999;8(4):449–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2009. July 15;25(14):1754–60. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ali YO, Escala W, Ruan K, Zhai RG. Assaying Locomotor, Learning, and Memory Deficits in Drosophila Models of Neurodegeneration. JoVE J Vis Exp. 2011. Mar 11;(49):e2504. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data for functional assays and MASS-PRF pipeline and results have been deposited to Dryad: DOI XXX.