Abstract

Eukaryotic genomes can usurp enzymatic functions encoded by mobile elements for their own use. A particularly interesting kind of acquisition involves the domestication of retroviral envelope genes, which confer infectious membrane-fusion ability to retroviruses. So far, these examples have been limited to vertebrate genomes, including primates where the domesticated envelope is under purifying selection to assist placental function. Here, we show that in Drosophila genomes, a previously unannotated gene (CG4715, renamed Iris) was domesticated from a novel, active Kanga lineage of insect retroviruses at least 25 million years ago, and has since been maintained as a host gene that is expressed in all adult tissues. Iris and the envelope genes from Kanga retroviruses are homologous to those found in insect baculoviruses and gypsy and roo insect retroviruses. Two separate envelope domestications from the Kanga and roo retroviruses have taken place, in fruit fly and mosquito genomes, respectively. Whereas retroviral envelopes are proteolytically cleaved into the ligand-interaction and membrane-fusion domains, Iris appears to lack this cleavage site. In the takahashii/suzukii species groups of Drosophila, we find that Iris has tandemly duplicated to give rise to two genes (Iris-A and Iris-B). Iris-B has significantly diverged from the Iris-A lineage, primarily because of the “invention” of an intron de novo in what was previously exonic sequence. Unlike domesticated retroviral envelope genes in mammals, we find that Iris has been subject to strong positive selection between Drosophila species. The rapid, adaptive evolution of Iris is sufficient to unambiguously distinguish the phylogenies of three closely related sibling species of Drosophila (D. simulans, D. sechellia, and D. mauritiana), a discriminative power previously described only for a putative “speciation gene.” Iris represents the first instance of a retroviral envelope–derived host gene outside vertebrates. It is also the first example of a retroviral envelope gene that has been found to be subject to positive selection following its domestication. The unusual selective pressures acting on Iris suggest that it is an active participant in an ongoing genetic conflict. We propose a model in which Iris has “switched sides,” having been recruited by host genomes to combat baculoviruses and retroviruses, which employ homologous envelope genes to mediate infection.

Synopsis

Mobile genetic elements have made homes within eukaryotic (host) genomes for hundreds of millions of years. These include retroviruses that integrate into host genomes as an essential step in their life cycle. While most such integration events are likely to be either deleterious or of little consequence to the host, on rare occasions host genomes can preserve and exploit capabilities of mobile elements for their own function. Especially intriguing are instances where host genomes have chosen to retain the envelope genes of retroviruses; the same envelope genes are responsible for conferring infectious ability to retroviruses. Primates and rodent genomes each have domesticated retroviral envelope genes (called “syncytin” genes) for important roles in placental function.

Now, Harmit Malik and colleagues show that a similar, ancient domestication event has taken place within the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. They identify a gene, Iris, which was acquired from an envelope gene of insect retroviruses, and has been maintained as a host gene for more than 25 million years. Unexpectedly, the authors find that Iris continues to evolve rapidly whereas previous studies have shown that mammalian syncytin genes do not. They suggest a model in which the Iris gene has “switched sides,” from its original role in causing infections to its current role in preventing them.

Introduction

Despite the fact that mobile elements are generally detrimental to host fitness, there are several instances where eukaryotic genomes have harnessed the enzymatic machinery of transposable elements to perform a myriad of important functions. For instance, the reverse transcriptase activity of the telomerase enzyme, which protects the ends of linear chromosomes [1], is believed to be the ancient descendant of prokaryotic mobile genetic elements [2]. In several species of Drosophila, active Het-A and TART retroposons still carry out this important function [3,4]. The core enzymatic machinery used to carry out V(D)J recombination in the generation of antigen recognition diversity is encoded by the RAG1/RAG2 proteins, believed to be descended from a previously autonomous transposon [5,6]. Many human genes are derived from the integrase machinery of transposable elements [7–9], and although their function is still unknown, many of them appear to have conserved their enzymatic ability [10]. Host genomes can also employ mobile elements' genes for genome defense. In murine genomes, a domesticated retroviral gag gene, Fv1, can defend mouse cells against infections by exogenous retroviruses [11]. These represent examples of how host genomes can acquire and eventually exploit the enzymatic capabilities of mobile elements for host functions.

“Domestication” of retroviral envelope (env) genes is especially intriguing in this context. While the env gene usually confers infectious ability to retroviruses, the human endogenous retrovirus-W env gene now appears to play a critical role in placental morphogenesis in higher primate genomes [12]. This gene, called syncytin, is still present in the context of a human endogenous retrovirus-W provirus that entered the primate lineage about 35 million years ago [13], indicating that it is still at the early stages of “evolutionary domestication” in its transition from a retroviral env to a host gene [14,15]. Indeed, selection pressures on the rest of the retroviral sequence show early signs of decay, but the syncytin gene itself is under strong selective constraints and is conserved among all hominoids and Old World monkeys [14]. Thus, while the endogenous retrovirus itself has lost the service of its env gene, host genomes now exploit this gene's membrane-fusion ability to carry out the important process of trophoblast differentiation [12,16]. Recently, three other retrovirus env-derived host genes have been described. Syncytin-2 is a 35-million-year-old host gene also found in primate genomes, which is derived from human endogenous retrovirus-FRD and appears to be predominantly expressed in placenta [17]. Two separate retrovirus-derived fusogenic env genes, syncytin-A and syncytin-B, have been shown to be expressed in murine placental tissues [18]. These genes represent a remarkable case of convergent evolution where rodent and primate genomes have each acquired retroviral env genes for important roles in placental differentiation.

Most retroviruses appear to be derived from ancestral non-viral retrotransposons that lacked infectious ability [19,20]. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that the acquisition of env genes drove the evolutionarily important transition from a non-viral retrotransposable element to an infectious retrovirus on at least nine occasions [20,21]. Two of these instances led to the gypsy and roo retroviruses in Drosophila, which have both separately acquired homologous env genes from baculoviruses, double-stranded DNA viruses with large genomes [20,22]. Many baculoviruses employ this env gene for mediating infection [23]. In both retroviruses and baculoviruses, infectious ability requires a proteolytic cleavage to separate the envelope protein into the SU (receptor-binding component) and TM (brings membranes into close apposition and causes fusion) proteins. Just downstream of furin cleavage site is a hydrophobic fusion peptide that is also required for membrane fusion [24,25].

The release of the D. melanogaster genome sequence [26] provided a unique resource to help address the chronology of env acquisition by retroviruses. For instance, it gave a sequence snapshot of all proviral insertions in the D. melanogaster genome [27,28]. Compared to mammalian genomes, Drosophila genomes have a higher rate of DNA loss [29], thus proviral sequences are more likely to reflect recent insertion events or insertions that have been selectively retained. In our survey, we unexpectedly found that the D. melanogaster genome contains a host gene, CG4715 (renamed Iris in this paper), which is homologous to the env genes from baculoviruses and insect retroviruses (also identified in [22] [30]). We have now investigated the evolution of Iris in insect genomes, and found it to be conserved in most Drosophila species of the Sophophora subgenus. We can trace the acquisition of this env gene to a sister lineage of the roo insect retroviruses (named Kanga in this paper). Investigation of the selective constraints on Iris reveals that it has been subject to positive selection throughout its evolution in Drosophila. This unusual finding of positive selection on a domesticated retroviral env gene suggests that it is an active participant in an extant genetic conflict in its host genomes, possibly to combat against insect viruses that bear homologous env genes.

Results

CG4715 is a Viral Envelope–Related Host Gene in Drosophila

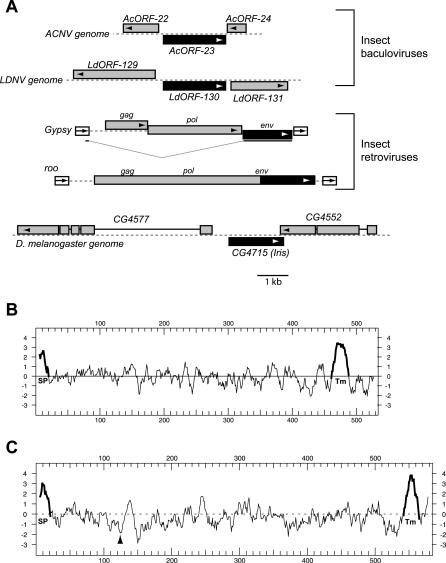

In order to investigate whether or not the D. melanogaster genome had domesticated any retroviral genes, we initiated searches of the databases by PSI-BLAST using the various encoded genes from the gypsy and roo insect retroviruses. We found a strong match to their env genes in a previously unannotated gene, CG4715, in the D. melanogaster genome [22]. The genomic regions surrounding CG4715 bear no discernible similarity to baculoviral or retroviral sequences, ruling out the possibility that CG4715 represents the evolutionary remnant of a recent retroviral-introduced provirus or a baculoviral insertion. Figure 1A schematizes the genomic contexts of the env homologs found in baculoviral, retroviral, and the D. melanogaster genomes. CG4715 bears many of the hallmarks of the gypsy and roo env genes, including the same architecture consisting of a signal peptide and a carboxyl-terminal hydrophobic peptide that is likely to be membrane-spanning (Figure 1B and 1C).

Figure 1. CG4715 Homologs.

(A) Baculoviral and insect retroviral env genes shown in their respective genomic context. Baculoviruses, represented by Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (ACNV) and Lymantria dispar nucleopolyhedrosis virus (LDNV) are double-stranded DNA viruses whose genome size is close to 150 kilobases [72], while retroviruses, represented by roo and Gypsy, are close to 7 kilobases in length [73]. CG4715 is an open reading frame found in the same genomic context in many species of Drosophila. CG4715/Iris and its env homologs are shown in black (open reading frame direction shown by arrows) while neighboring genes are shown in gray. Note that the gypsy env is expressed through a spliced message. Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy plots of encoded protein products from CG4715 (B) and the roo env gene (C) are shown. The putative signal peptide (SP) and C-terminal, transmembrane hydrophobic peptide (Tm) are highlighted in bold, while the furin cleavage site in the roo envelope protein is indicated by an arrowhead.

We obtained CG4715 sequence from ongoing genome sequencing projects in several species of Drosophila using synteny (gene order) and TBLASTN searches. We screened for the presence of CG4715 in closely related species of the Sophophora subgenus of Drosophila using PCR and primers designed to flanking sequences (see Materials and Methods), and were able to confirm the presence of CG4715 in several additional species of Drosophila (Figure 2A and 2C). During our sequencing efforts, we uncovered two CG4715-related genes in tandem orientation in all species of the takahashii/suzukii subgroups. Figure 2C represents the phylogenetic analysis of CG4715 genes in the Sophophora subgenus of Drosophila (based on a partial alignment of their coding sequences), whose phylogenetic relationship is in good agreement with the widely accepted phylogeny of this genus [31,32] (schematized in Figure 2B). This indicates that this gene has been inherited strictly by vertical inheritance rather than by horizontal transfer, a conclusion that is supported by the fact that CG4715 is found in the same syntenic location in different species (Figure 2A). Of the two CG4715 genes found in the takahashii/suzukii groups, the 5′ gene (referred to as CG4715-A) represents the true ortholog, while the second (CG4715-B) represents a gene duplication whose phylogenetic position (Figure 2C) is incongruent with the expected species phylogeny (schematized in Figure 2B). This phylogenetic placement could result from altered selective constraints (and different evolutionary rates) that could lead to a phylogenetic artifact known as “long-branch attraction” [33]. While we cannot rule out an ancient origin of the B lineage, this would lead to the unparsimonious implication that this gene was subsequently lost in all species except those from the takahashii/suzukii species groups.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic Analysis of CG4715 Homologs.

(A) CG4715 has been preserved in its syntenic location in Drosophila species. In species from the takahashii/suzukii species groups like D. lutescens, an additional paralog, CG4715-B (gray shading) is found in tandem orientation. D. ananassae has an additional transposon insertion in this syntenic location between CG4715 and CG4552, while the genomes of D. mojavensis and D. virilis lack CG4715 orthologs between CG4577 and CG4552. For D. ananassae and D. pseudoobscura, sequence was obtained from genome sequencing data (indicated with an asterisk) and confirmed by sequencing.

(B) An “expected” phylogeny of Drosophila species is shown, summarizing results from many genes [30,31].

(C) A neighbor-joining phylogeny of CG4715 orthologs based on C-terminal amino acid sequence is presented. (For some species, only the C-terminal sequence was obtained (indicated by a “p” for partial)). This phylogeny is largely in agreement with the accepted species phylogeny in (B), indicating that the gene has been inherited by strict vertical inheritance. Although there is a slight discordance in phylogenetic placement of the D. ananassae, D. eugracilis, and D. auraria, these branches have only a low bootstrap support. A second lineage of CG4715 paralogs, CG4715-B is evident (gray shading) in the takahashii/suzukii species groups.

In D. mojavensis and D. virilis, whose genome sequences are still incomplete, CG4715 is absent from its syntenic location, and we have not found true orthologs in other genomic locations. While it remains formally possible that the location of CG4715 is altered in these two species, it is more likely that CG4715 does not exist as a host gene in these species (BLAST searches did not reveal any orthologs). The latter possibility could be due to a subsequent loss event in D. mojavensis and D. virilis (both belong to the Drosophila subgenus, Figure 2B) or because CG4715 originated only after the separation of the Sophophora and Drosophila subgenera. Completion of ongoing sequencing projects in the D. willistoni, D. mojavensis, D. virilis, and D. grimshawi species will help distinguish among these possibilities.

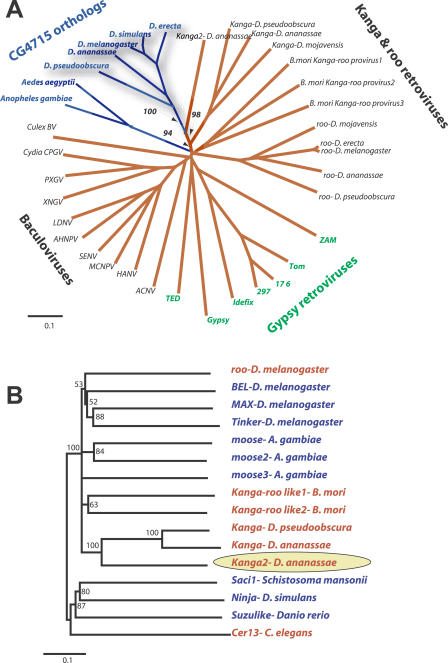

CG4715 is the Domesticated Envelope Gene of the Kanga Insect Retroviruses

Where did CG4715 come from? The closest homologs to CG4715 in the available sequences of all Drosophila genomes are the env genes of a novel lineage of retroviruses, which appear in several species of the Sophophora subgenus (ongoing sequencing projects, see Materials and Methods). This lineage of retroviruses is most closely related to the roo lineage of BEL-like retroviruses, and we refer to it as Kanga [34–36]. In a detailed phylogenetic analysis of all CG4715-env related genes (Figure 3A), the CG4715 orthologs unambiguously branch together with the env genes of Kanga. We also investigated genome sequences from other insects for CG4715 homologs. Remarkably, the Anopheles gambiae genome also contains a homolog of CG4715 with the same architecture. Like the Drosophila CG4715 gene, the A. gambiae gene is not flanked by regions homologous to either retroviral or baculoviral sequences. Using the A. gambiae gene as a query, we were able to successfully retrieve its Aedes aegyptii ortholog as well. We can detect Kanga-roo-like retroviruses in the lepidopteran Bombyx mori (silkmoth) genome, but not in the Apis mellifera (honeybee) genome. Intriguingly, while the A. gambiae genome has multiple retrotransposons related to the Kanga-roo retroviruses, none of these is predicted to encode an env gene. The primary reason that the Kanga retroviruses have not been described so far appears to be their absence in the earliest sequenced insect genomes, including D. melanogaster and A. gambiae.

Figure 3. CG4715/Iris Relationships to Viral Envelope Genes.

(A) The central domains of CG4715 and related viral env genes were aligned, and a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree constructed. The tree separates the CG4715-env superfamily into four groups: the baculoviruses, the BEL clade retroviruses roo and Kanga, the gypsy-like retroviruses, and host genome borne CG4715 orthologs in Drosophila and mosquito genomes. While the tree overall does not provide high resolution to discern the order of divergence of each of the clades, there is very strong phylogenetic resolution (bootstrap support of key nodes shown) to unambiguously group CG4715 orthologs with the Kanga retrovirus lineage, indicating that this lineage of retroviruses is the likely source of the CG4715 lineage.

(B) Neighbor-joining phylogeny of selected representatives from the BEL clade of retrotransposons indicates that the Kanga retroviruses from Drosophila genomes form a monophyletic clade (the presumed ancestor of CG4715 is indicated by a yellow oval). Most retrotransposons in the BEL lineage do not possess an env gene (blue lettering) while many elements that do (red) have acquired non-homologous env genes acquired from a different viral source [19,20].

On a phylogenetic tree of all CG4715-env related homologs (Figure 3A), the two mosquito genes represent a distinct lineage from that of the Drosophila CG4715 orthologs and Kanga retroviruses. Parsimony criteria based on the phylogeny in Figure 3A strongly argues that the retroviral borne env gene represents the ancestral form. We can say with high confidence that the Drosophila CG4715 genes have derived from within the Kanga retroviral lineage (bootstrap support on relevant nodes is highlighted in Figure 3A). Thus, we conclude that there have been two separate domestications of insect retroviral env genes in fruit fly and mosquito genomes, respectively. The domestication event in the Sophophora genus of Drosophila led to CG4715, which now has been preserved as a host gene. It is present in all species tested, and appears to have been inherited strictly by vertical inheritance for at least 25 million years (the estimated time of separation of D. melanogaster and D. pseudoobscura [31]).

To better gauge the evolutionary origins of the newly identified Kanga retroviruses, we compared the majority of the pol sequence (PR-RT-RNH domains) of Kanga to other known insect retrotransposon lineages. These showed that Kanga retroviruses belong unambiguously to the BEL clade, which also includes the roo but not the gypsy retroviruses (Figure 3B). Previous analyses have shown that only a few lineages of the BEL elements also possess env genes (red in Figure 3B) and that the Caenorhabditis elegans and D. melanogaster retroviruses of this lineage have non-homologous env genes[19,20], indicating that the non-infectious retrotransposons (blue lineages) are likely to be the ancestral form.

Etymology

Based on our phylogenetic analyses (Figure 3A), it is clear that CG4715 orthologs represent a sister lineage to the env genes from Kanga retroviruses. In Greek mythology, the Titan Thaumas and Electra had two sets of offspring. The first were the winged monsters, the Harpies (which we liken to the insect retroviral and baculoviral env genes). The second was Iris, the goddess of the rainbow and the messenger of the god Zeus and his wife, Hera. Since CG4715 is clearly maintained as a host gene, we use the analogy to the benevolent sibling of the mythological Harpies to propose the name Iris to represent the CG4715 orthologs, since they are related to viral env genes but are presumably beneficial to the host genome, based on their conservation.

Iris Expression

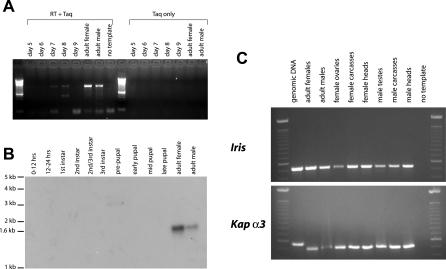

Its strong conservation suggested that Iris might perform some important function in insects. To investigate this, we examined Iris expression in D. melanogaster. Using RT-PCR and Northern blots on pools of polyA RNA representing all life-stages of D. melanogaster, we determined that Iris is expressed primarily in adults in both males and females, with weak expression at the third instar larval stages (Figure 4A and 4B). By RT-PCR analysis on individually dissected tissues, we found Iris is transcribed in most adult tissues, with expression only slightly lower in ovaries and testes (Figure 4C). Our RT-PCR results are consistent with what was observed in a recent large-scale survey of Drosophila gene expression patterns in ovaries, testes, and the soma [37]. The expression pattern appears to suggest that Iris may have been domesticated for some role in adult flies, either within germline or somatic tissues, or both.

Figure 4. Iris Expression in D. melanogaster .

Iris expression through various stages of development was assayed using (A) RT-PCR and (B) Northern blots. Both show that Iris is predominantly expressed in adult females and males. (C) RT-PCR analysis on individually dissected tissues from adult flies shows that Iris is expressed in somatic tissues but expression is slightly reduced in ovaries and testes. RT-PCR to Karyopherin alpha-3 (αKap3, a ubiquitous nuclear import factor- CG9423) is shown as a control for amounts of template RNA in the RT-PCR reaction, and to show that there is no detectable contamination from genomic DNA.

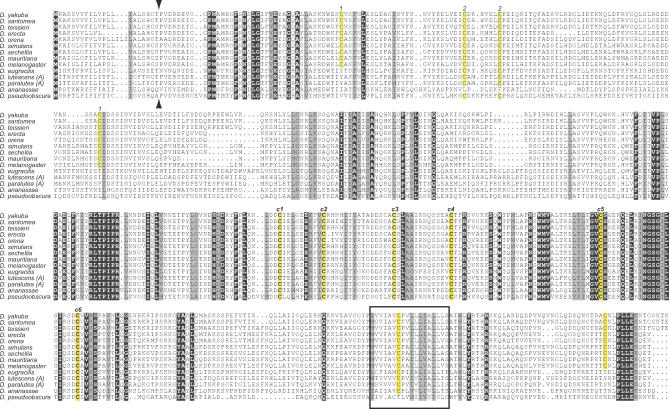

Conserved Features among Iris Orthologs and Paralogs

An amino acid alignment of all full-length Iris orthologs is shown in Figure 5. Several features are conserved, including a signal peptide (putative cleavage site shown by arrowheads) and a C-terminal hydrophobic peptide that presumably represents a membrane-spanning segment by analogy to the retroviral envelope proteins. In addition, several cysteine residues (highlighted in yellow) are variably conserved. Co-conservation of particular cysteine residues suggests that these cysteine residues participate in a disulfide bond either within the same molecule or across different molecules (“1–1” and “2–2”). Six cysteine residues (c1 through c6) are invariant; these are also highly conserved across all of the homologous retroviral env genes (Figure 3A). In general, the C-terminal domain of Iris is more conserved than the N-terminus among orthologs, and between Iris and retroviral envelope proteins. Some residues at the C-terminus, after the predicted membrane-spanning peptide, are also highly conserved (PLLEK amino acid residues). Based on bioinformatic predictions and by analogy to retroviral envelope proteins, this represents the cytoplasmic tail of Iris, and suggests that this may participate in either the physical anchoring of Iris at the cell membrane, or some downstream signal transduction.

Figure 5. Complete Alignment of Iris Proteins.

An alignment of full-length Iris proteins from various Drosophila species is shown. All invariant residues are shown against a black background (except cysteines that are highlighted in yellow), while similar residues are highlighted in gray background. We did not include the Iris-B lineage here for ease of presentation (these are presented in Figure 6). Several features are conserved, including the signal peptide (predicted cleavage site indicated by arrowheads), C-terminal transmembrane domain (shown as a box), and several invariant cysteine residues (c1 through c6, highlighted in yellow) that are a characteristic feature of Iris and related envelope proteins. Other cysteine residue pairs (1–1 and 2–2, also highlighted in yellow) show co-conservation, i.e., loss of one results in loss of the other.

One feature that is almost universally conserved among retroviral envelope proteins is a furin cleavage site followed by a hydrophobic peptide that represents the fusion peptide. Surprisingly, we found that the Iris protein in D. melanogaster lacks the central furin cleavage site and fusion peptide found in all env genes capable of mediating infection. We investigated when this cleavage site degenerated on the Iris-env phylogeny (Figure 3A). We employed a MAST search [38] using a position-specific scoring matrix constructed from a subset of retroviral homologs as previously described [20]. As a positive control, we used retroviral and baculoviral env genes where we knew that the furin cleavage site was conserved. For a negative control, we used homologous baculoviral genes where the furin cleavage site has been shown to have degenerated [39]. We queried three Iris proteins (from D. melanogaster, D. ananassae, and D. pseudoobscura), one domesticated mosquito gene (from A. gambiae), and the env gene from the Kanga retroviruses using this consensus. Using this strategy, we find that both Kanga retroviruses and the domesticated envelopes from mosquito genomes have a conserved furin cleavage and fusion peptide (E-value < 0.001), while this site is not conserved in any of the Iris proteins (E-value > 10). This suggests that the fruit fly and mosquito domestication events differ both chronologically and qualitatively, and that this cleavage site has been lost in the Iris lineage. This loss of cleavage is especially noteworthy since other architectural features, including several conserved pairs of cysteine residues (c1 through c6) presumed to be necessary for membrane fusion ability and post-cleavage interactions between the SU and TM domains, are still conserved [22] (Figure 5). This suggests that while these features are essential for membrane fusion, they may also serve another function.

A Second Iris Gene in the takahashii/suzukii Species Groups: A New Mode of Neofunctionalization?

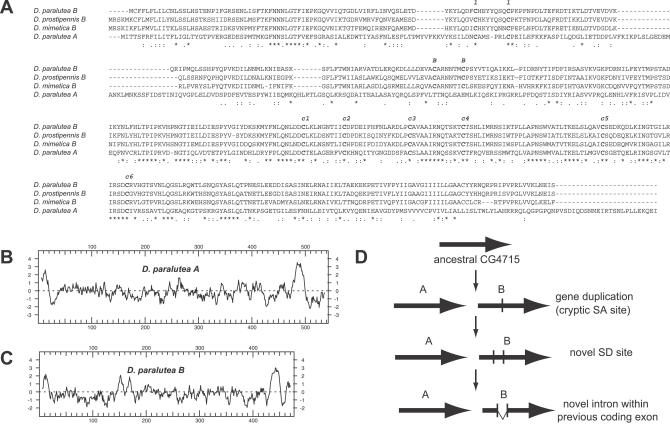

All Drosophila species that we have investigated in the Sophophora subgenus (Figure 2B) possess an Iris ortholog in a syntenic location. Surprisingly, the takahashii/suzukii species groups have two genes that are found in tandem orientation (Figure 2A). We have shown that the first of these (Iris-A) represents the true ortholog while the second (Iris-B) is paralogous (Figure 2C). At first glance, the second gene (Iris-B) appears to be a pseudogene. All other Iris orthologs are intron-less genes. Based on this expectation, Iris-B (which is the same length as Iris-A) has frameshifts and nonsense codons. However, when we did RT-PCR on this gene in D. lutescens and D. prostipennis, we found that these genes had spliced out an intron of ~70 nucleotides. Removing this intron now recapitulates an open reading frame that is highly homologous to that of Iris-A. We found that the splice acceptor (SA) and splice donor (SD) sequences are invariant, and we conclude that all Iris-B genes possess a single intron. An amino acid sequence comparison of representative Iris-A and Iris-B genes is presented in Figure 6A. Once again, the C-terminal half of the gene is well conserved (including c1 through c6, highlighted in Figure 5), with more variation in the N-terminus. Hydropathy plots (Figure 6B and 6C) illustrate that despite the loss of exonic sequence, the overall architecture of the Iris-B proteins is largely unaltered. Some differences are apparent, however. For instance, Iris-B lacks the conserved residues at the C-terminus of Iris-A (PLLEK amino acid residues). Additionally, Iris-B has some conserved pairs of cysteine residues that are not found in Iris-A, suggesting that Iris-B now operates under altered selective constraints. This may be partly responsible for the “early branching” of the B lineage in the Iris phylogeny (Figure 2C).

Figure 6. Iris Paralogs in the takashii/suzukii Species Groups.

(A) An alignment of representative Iris-A and Iris-B proteins from the takahashii/suzukii species groups is shown. Iris-A and Iris-B proteins are highly similar to each other. Notable differences include pairs of cysteine residues that are conserved in the B lineage (indicated with “B”), but not in A. The B lineage also has a shorter cytoplasmic tail and is missing several residues (PLLEK amino acid residues) that are invariant in the A lineage. In addition, an internal segment of the Iris-A protein is lost from the Iris-B protein, by virtue of this genomic sequence becoming an intron (confirmed by RT-PCR).

(B and C) Hydropathy plots of representative Iris-A and Iris-B proteins show that the overall architecture of the two proteins is largely unaffected by the differences between the two lineages.

(D) A hypothetical model for the origin of the divergent Iris-B gene starts with the tandem gene duplication. A cryptic SA site is encountered by mutation, but this can be neutrally maintained. However, the simultaneous occurrence of an SD site activates the SA site and leads to a portion of the coding exon being spliced out from the mature message. If this is deleterious, the SD-SA combination is culled out by selection. However, in rare cases, like the Iris-B gene, this could lead to a novel functional gene that is favored by selection. Subsequently, the SD and SA sites are maintained by purifying selection.

Their maintenance since the evolutionary origin of the takahashii/suzukii groups suggests that the Iris-B genes are evolving under selective constraints. Following gene duplication, a duplicate gene can suffer three fates: non-functionalization (degeneration of function), neofunctionalization (new function), or subfunctionalization (assortment of ancestral functions). We cannot distinguish between the latter two possibilities. Nonetheless, the striking differences in Iris-B compel a hypothetical parsimonious model (Figure 6D) as to how the differences arose. Cryptic SA sites likely occur and are lost neutrally, but the simultaneous gain of an SD site leads to a selective decision. If the spliced product is non-functional, the SD-SA combination is lost. However, if there is a sufficient selective advantage for the truncated protein, then the SD-SA combination will sweep through the population and be maintained by purifying selection. Previously, there has been at least one well-documented instance of a previously intronic or intergenic sequence becoming exonic and a previously exonic sequence becoming a promoter (the Sdic gene in D. melanogaster [40]), but the de novo “invention” of an intron in what previously was exclusively exonic sequence appears to be a novel finding. The scenario we have presented in Figure 6D is simple but likely to be quite rare. However, unlike the much more frequent event of intron transposition, it is conceivable that intron invention may have contributed extensively to the gain of new protein functions.

Molecular Evolution of Iris in Drosophila Species

Most retroviral insertions into the host genome are either detrimental or selectively neutral. Therefore, upon insertion into host genomes, these proviral genes start decaying due to mutation. However, retroviral genes that are beneficial to the host genome can be domesticated; these genes can evolve either under purifying or positive selection. In the first scenario, the newly domesticated gene now carries out a housekeeping function, and selective pressures cull out deleterious mutations, including the majority of those that change the amino acid sequence. The mammalian domesticated syncytin gene falls into this category [12,14,15]. On the other hand, the host could also recruit a retroviral gene to protect itself from future rounds of infections, as murine genomes appear to have done with the domestication of a gag gene, Fv1 [11,41], or an env gene, Fv4 [42]. In either scenario, i.e., housekeeping or defense, the domesticated gene is likely to be well conserved because it confers a selective advantage, but the selective pressures are quite distinct and likely to discriminate among possibilities of function. For instance, in the latter host defense scenario, the newly domesticated gene might evolve rapidly at the amino acid level due to selective pressures to keep pace with rapidly evolving infectious agents, as is the case for Fv1 [41].

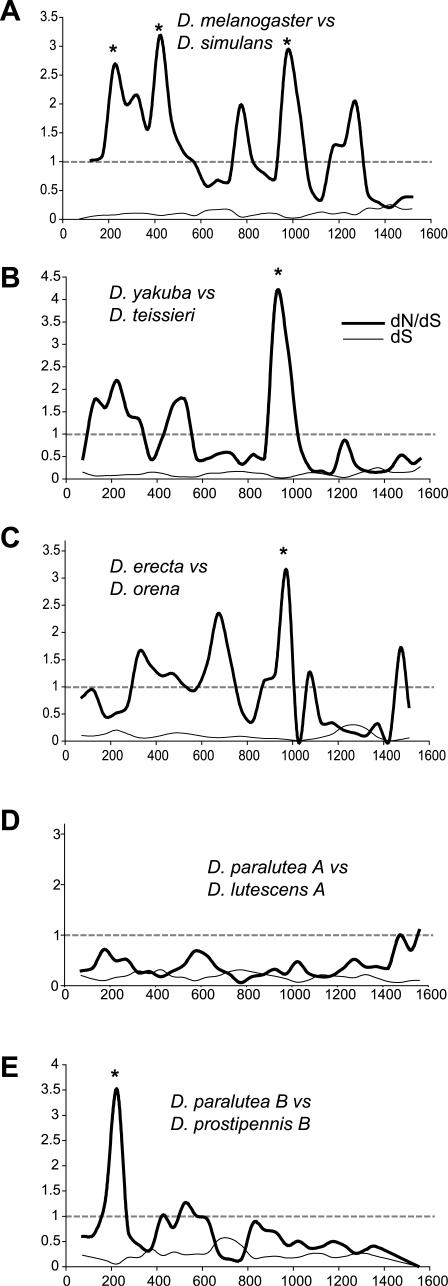

What selective constraints have shaped Iris evolution? Since Iris is a host gene related to retroviral env genes, we were interested in investigating the selective pressures under which it has evolved. We compared synonymous (dS) and non-synonymous (dN) nucleotide changes in five, non-overlapping pair-wise comparisons across the Drosophila phylogeny [43]. These results are presented in Figure 7 and highlight the variable nature of selective constraints, which have acted on Iris in the course of its evolution in Drosophila species. We find several windows where dN/dS significantly exceeds 1, but the location of these windows is variable from one pair-wise comparison to the next. In the case of the Iris paralogs in the takahashii species group, we find no evidence of positive selection in the Iris-A comparison (Figure 7D), but a significant window in the N-terminus of Iris-B (Figure 7E). This could simply reflect stochastic differences, but it is intriguing that the Iris-A comparison is the only one in our set that did not show any windows where dN/dS significantly exceeds 1.

Figure 7. Sliding Window dN/dS Analyses of Different Drosophila Iris Genes.

We have chosen non-overlapping sets of the Drosophila species to do a pair-wise analysis of dN compared to dS. We present a sliding window analysis (window size 150 base pairs, slide of 50 base pairs) of dS and the dN/dS ratio (y-axis) plotted against nucleotide position (x-axis). Under neutrality, a dN/dS ratio of 1 is expected (dashed lines). We present a comparison of (A) D. melanogaster versus D. simulans, (B) D. yakuba versus D. teissieri, (C) D. erecta versus D. orena, (D) D. paralutea A versus D. lutescens A, and (E) D. paralutea B versus D. prostipennis B. In all these comparisons except (D), at least one window where dN/dS significantly exceeds 1 is seen (indicated by asterisks; significance tested by simulations in the K-estimator program [43]).

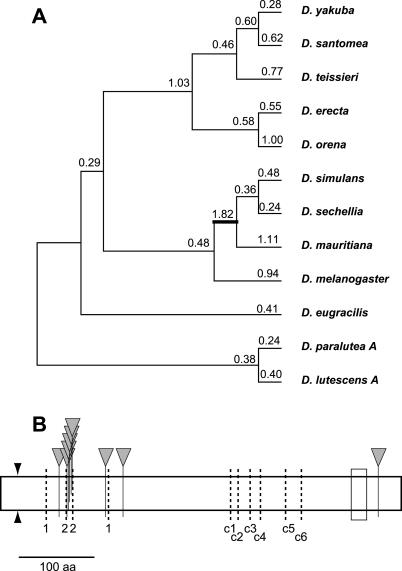

We also performed a maximum likelihood based analysis of selective pressures acting on Iris using the PAML and random effects likelihood (REL) and fixed effects likelihood (FEL) programs [44,45]. We chose only a closely related set of full-length Iris orthologs (12 total up to D. eugracilis) for this purpose, to minimize the number of gapped positions in the alignment. We excluded all positions with gaps to avoid any ambiguities in alignments. Notably, these gapped regions had the maximum variability in sequence. Results from these analyses are shown in Figure 8A and Table 1. A whole-gene assignment of dN/dS ratios to the different branches of the Iris phylogeny is shown in Figure 8A. Only three branches were shown to have a dN/dS greater than 1. This is not surprising because domains subject to purifying selection (where dN/dS is less than 1) can mask the signal of windows of positive selection such that the overall dN/dS in the gene does not exceed 1. In spite of this, we found that the lineage leading up to the sibling species D. mauritiana, D. simulans, and D. sechellia had a dN/dS ratio of 1.82. Using PAML comparisons in which this branch was fixed at dN/dS = 1 versus dN/dS = 1.82, we found weak evidence that positive selection occurred on this branch (highlighted in Figure 8A; 2ΔlnL = 3.1 and 1 degree of freedom, p < 0.08) despite the fact that the whole gene was being analyzed.

Figure 8. PAML Analyses of Iris Evolution.

(A) A free-ratio model for Iris evolution in Drosophila is presented with numbers above branches indicating (whole gene) dN/dS ratios estimated for each individual branch. Only the lineage leading to the sibling species D. mauritiana, D. sechellia, and D. simulans (thick line) has a dN/dS ratio that appears to be greater than 1. When this value of dN/dS = 1.82 was compared against the neutral expectation of 1, the higher value fit the data marginally better (p < 0.08).

(B) Individual residues highlighted by PAML analyses as having being subject to recurrent positive selection are shown by inverted triangles. Also schematized are the signal peptide cleavage site (arrowheads) and C-terminal hydrophobic peptide (box). Dark, dashed lines indicate the ten cysteine residues (1–1, 2–2, c1 through c6) highlighted in Figure 5. We note that most of the residues identified at high confidence appear to cluster around the 2–2 pair of cysteine residues, suggesting a functional interaction surface here [46].

Table 1.

PAML and REL Analyses of Iris in Drosophila [44]

A whole gene dN/dS ratio comparison can fail to identify specific domains or residues subject to positive selection. We investigated this latter possibility on the multiple alignment of Iris from 12 Drosophila species using a comparison of NSsites model M7 (a beta distribution with no positive selection) and model M8 (a beta distribution with positive selection permitted). We find that model M8, which allows one class of codons to have allowed under positive selection, fits the data significantly better (Table 1, p < 0.002). Thus, we conclude that Iris has been subject to positive selection through this period of Drosophila evolution. This analysis also highlights a few residues as being repeatedly subjected to positive selection (posterior probability > 0.95 in Table 1). There is remarkable congruence between these results and those obtained from a similar REL analysis and the more conservative FEL analysis (Table 1). Of the nine residues that were identified by the PAML analysis over the entire protein (~ 500 residues compared), six are clustered within 15 amino acids around the 2–2 pair of cysteine residues (Figures 5 and 8B). We have previously tested “patches” of positive selection similarly identified by PAML analyses in the retroviral defense gene TRIM5α and have shown that they represent interaction interfaces between host and viral proteins [46]. These analyses suggest that the 2–2 pair of cysteine residues may encode a similar interaction interface.

To investigate the effects of positive selection on standing genetic variation, we sequenced Iris from a variety of strains of D. melanogaster (14 strains) and D. simulans (17 strains) to carry out population genetic analyses. Using the McDonald-Kreitman test, we first compared fixed interspecies differences to intraspecific polymorphisms at replacement and synonymous sites [47]. Fixed Rf:Sf changes between the two species are 77:25, while the polymorphic Rp:Sp ratio is 90:36. These values are not significantly different from each other (p ~ 0.5). Polarizing changes to just the D. melanogaster lineage (40:17 versus 44:17) or just the D. simulans lineage (49:16 versus 46:21) also did not reject the null expectation. One potential source of discordance between the dN/dS and the McDonald-Kreitman test results could be strong selective pressures acting on the intraspecific polymorphisms, compared to interspecific divergence. This could suggest, for instance, that the bulk of the dN/dS signal observed in Figure 7A was in fact due to intraspecific polymorphisms. However, we confirmed that this was not the case by reconstructing the hypothetical ancestor of all D. melanogaster and all D. simulans strains and performing a pair-wise dN/dS comparison, which is practically identical to Figure 7A (unpublished data).

Iris and the Phylogeny of D. simulans Sibling Species

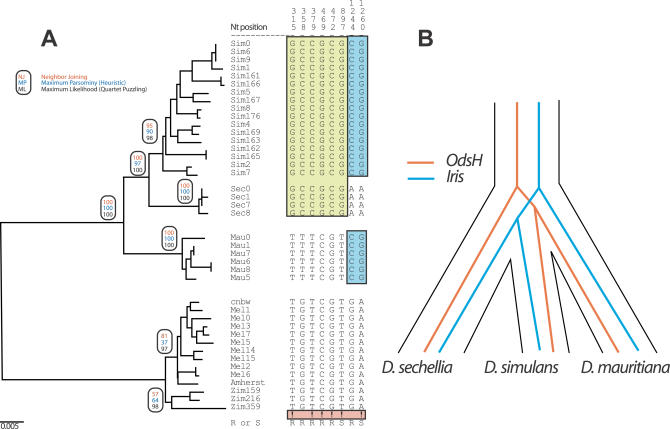

Positive selection may have had a strong impact on Iris evolution even in closely related species, due to species-specific infections by mobile elements. Horizontal transfers of DNA-mediated transposons and LTR-retrotransposons [28,48–50] can lead to species-specificity of transposon propagation. These selective pressures could be predicted to lead to the rapid fixation of Iris polymorphisms in a species-specific manner, which might subsequently resist introgression of alleles from other species because of constant selective pressures. We tested these possibilities by comparing Iris sequences from several strains of D. simulans, D. mauritiana, and D. sechellia since these species appear to have the most striking signature of positive selection (Figure 8A). These three species are believed to have separated less than 500,000 years ago [51]. In our phylogenetic analysis (Figure 9A), Iris sequences from each species form their own exclusive clade to a high degree of statistical support, in large part due to six nucleotide differences that are unambiguously diagnostic for branching order within these three sibling species.

Figure 9. Iris Phylogeny in Closely Related Species.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis of Iris coding regions from different strains of D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. sechellia, and D. mauritiana, the latter three species believed to have diverged less than half a million years ago [51]. Based on distance, parsimony or likelihood methods (bootstrap values indicated in ovals), the phylogeny clearly separates the three species. This is largely due to six sites that are “unambiguous” as far as phylogenetic information is concerned, indicated with “!.” An unambiguous site is defined as one in which the same derived nucleotide is found fixed in two of the three species (e.g., D. simulans and D. sechellia), whereas the third species (e.g., D. mauritiana) is fixed for the ancestral nucleotide, corresponding to the out-group, D. melanogaster.

(B) Iris is only the second known gene to inform about the phylogeny of the three sibling species D. simulans, D. sechellia, and D. mauritiana with statistical significance. In the Iris phylogeny, D. mauritiana branched earliest while previously, D. sechellia was found to branch earliest. This suggests that speciation events' chronology among these three species is more complicated than suggested previously [52].

The ability to phylogenetically separate these three species has only been seen previously for the Odysseus homeobox (OdsH) gene [52] that has been proposed to play a role in hybrid sterility [53]. The difficulty in resolving these relative recent speciation events is likely to result from the persistence and possibly introgression of ancestral alleles following speciation [51,52]. Indeed, since only speciation genes would be able to resist the effects of introgressed alleles from other species, it has been previously suggested that only these would have the required resolution to trace the exact chronology of reproductive isolation among recently diverged species. Based on the OdsH gene, the case has been made for allopatric speciation among the sibling species D. simulans, D. mauritiana, and D. sechellia, with D. sechellia branching first [52].

Our results call into question the generality of these previous conclusions. While Iris also resolves the phylogeny to almost the same degree of certainty, the chronology of events traced by Iris are different from those traced by OdsH. Thus, in the case of OdsH, six “unambiguous” sites indicated that D. sechellia was the out-group, while one site indicated that D. simulans was the out-group [52]. In the case of Iris, five sites (all in the N-terminus) indicate that D. mauritiana was the out-group species while one (the most C-terminal) indicates that D. sechellia was the out-group. We suggest that it is likely that all these phylogenetic reconstructions simply reflect the fact that a recent episode of positive selection affected only two out of three species, rather than the true chronology of reproductive isolation. Notably, OdsH is under strong positive selection between D. mauritiana and D. simulans, and its phylogeny groups these two species [52,53]. Similarly, there appears to be clear evidence that Iris is significantly diverged because of a species-specific selective pressure.

An important caveat is that both these genes reside on different chromosomes: OdsH on the X and Iris on 2L. Divergent selective regimes could have led to independent, species-specific chromosomal “speciation” events, although it is difficult to imagine how this could have been achieved in strict allopatry if they occurred simultaneously. Alternatively, the OdsH and Iris phylogenies could reflect temporal differences, with positive selection acting on OdsH at the speciation bottleneck that occurred in allopatry, while a different episode of positive selection acted on Iris subsequently. Interestingly, we find that Iris also separates the Zimbabwe strains from the cosmopolitan strains of D. melanogaster (Figure 9A phylogeny; unpublished data), consistent with known premating isolation between these populations [54].

Discussion

The evolutionary origin of viruses has long fascinated evolutionary biologists. Are they remnants of an ancestral lifestyle, or more recent escapees from traditional genomes [55]? The env genes of retroviruses are an important key to unlocking this conundrum; as first suggested by Howard Temin [56], their acquisition is the single event that allows previously genome-bound retrotransposons to adopt an infectious lifestyle. The genes that confer this ability appear to have been very desirable for eukaryotic genomes. In particular, the syncytin genes have been acquired in two mammalian lineages, while Iris-like genes have been acquired in two insect lineages. However, there are significant differences between the syncytin and Iris domestication events. First, the syncytin genes show a signature of purifying selection in primates, consistent with their domesticated role in placental function [15]. Iris, on the other hand, appears to be an active participant in an ongoing genetic conflict as evidenced by the signature of positive selection. Second, the syncytin gene has retained the same architecture of the ancestral retroviral env gene including the SU/TM furin cleavage site, since it still carries out the ancestral membrane fusion function [12,14]. Iris, on the other hand, has degenerated this cleavage site, suggesting that Iris's current function does not require membrane fusion. Third, while syncytin clearly derived from an endogenous retrovirus, the donor retroviruses appear to be extinct, especially in the human genome. However, the Kanga retroviruses appear to be active, which may greatly aid studies on this interesting domestication of a retroviral env in an organism with more facile genetics.

Are the selective pressures on Iris unique? We know of two other cases of proviral env genes domesticated for host defense: Fv4 and Rmcf. Neither has been investigated for selective constraint. However, in the case of both Fv4 and Rmcf [42,57], the mode of defense is by the domesticated env gene blocking the receptor required for retrovirus entry [58,59]. Under this scenario, unless the receptor is subject to positive selection, the domesticated gene does not have a “moving target” and is not expected to be subject to positive selection. Indeed, the defense function of Fv4 and Rmcf may involve the stable co-evolution of the receptor and the domesticated ligand. Iris, on the other hand, is subject to positive selection, suggesting that its mode of action is likely to be directly at a protein–protein interaction surface with its antagonist [46]. Thus, we predict that Iris action is likely to be distinct from the receptor blockade mechanism.

What genetic conflict could Iris be subject to? Previously, there has been one case of positive selection of a viral gene that was recruited as an inhibitor of subsequent infections. The Fv1 restriction factor that guards against murine retroviral infections is a “domesticated” gag gene from a lineage of retroviruses [11] that has been proposed to be subject to positive selection in murine genomes [41]. Based on our finding of positive selection, and the precedent of the Fv1 gene, we propose that Iris has been recruited as a host gene specifically to defend adults against recurrent invasions by retroviruses and baculoviruses, which share a homologous env. Two hypothetical scenarios by which this defense could be achieved are schematized in Figure 10.

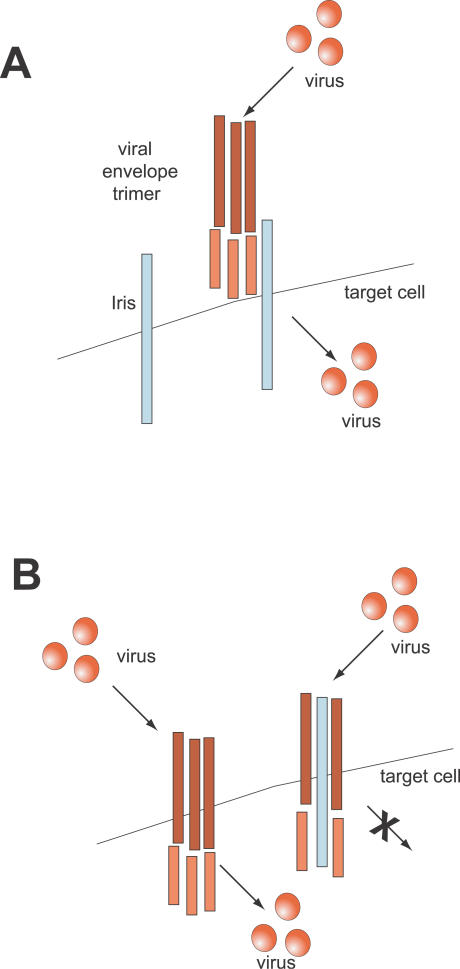

Figure 10. Two Hypothetical Models to Explain Positive Selection of Iris .

(A) Under the first model, Iris has been domesticated for a role other than host defense. As part of this housekeeping function, Iris proteins reside on the cell surface, where they can be recognized as receptors by viral envelope proteins. Variants of Iris that cannot be recognized by the viral envelopes have a selective advantage.

(B) A second model considers the possibility that Iris can act as a dominant negative agent that counteracts retroviral envelope trimers (red) from mediating infection. In this scenario, viruses encode for envelope trimers that can be cleaved into the SU ligand interaction and TM membrane fusion domains. In the absence of Iris, or if Iris lacks the specificity to bind the envelope trimers, the viral envelopes can mediate infection of the target cell. However, if the Iris protein (blue) can bind the viral envelopes and arrest the membrane fusion step, then the host defends against the viral infection. In this scenario, Iris directly acts as a host defense protein. Note that in both scenarios, Iris is predicted to be subject to positive selection (to decrease virus binding in the first model, and to increase virus binding in the second).

In the first model (Figure 10A), Iris is present on cell surfaces as part of a housekeeping function, as is the case for syncytin. But by virtue of its homology, it continues to act as a receptor for retroviruses. Under this scenario, the positive selection on Iris would cause it to avoid interacting with retroviral envelopes. Whether Iris has a housekeeping function can be directly tested with flies carrying mutations in the Iris gene. Under the second model (Figure 10B) Iris serves as a dominant negative inhibitor of retroviral trafficking. Since the Iris-encoded protein is expected to largely share the same architecture as the retroviral envelope proteins, it is expected to form multimers with the retroviral encoded envelope proteins. However, if the protein encoded by Iris is not cleaved, these may form multimers with retroviral envelopes that are incapable of mediating infection. In this scenario, the positive selection of Iris would act to improve recognition of retroviral envelope proteins to trap them in defective multimers (Figure 10B), while the latter would evolve away from this inhibitory interaction. We favor this second model because it provides a rational hypothesis for why the furin cleavage site has not been conserved. Under this model, we expect that Iris could defend against either horizontal transfers or germline transposition events. Germline tissues (ovaries and testes) are primarily where genome-bound retroelements need to transpose in order to increase their copy number within the genome. Gypsy-like retroviruses appear to infect the female oocyte [60], and recent studies indicate that this infection does not require the retroviral env genes [61–63]. However, these retroviruses have also been shown to be able to horizontally transfer to new hosts within the same species [64] and possibly to new species [65], and this activity depends on retroviral env activity.

Both models presented in Figure 10 are predicted to result in positive selection on Iris; genes subject to constantly antagonistic interactions (the “Red Queen” hypothesis [66]) are frequently subject to positive selection affecting the protein–protein interaction interface [46]. Our results raise the possibility that a number of retrovirus-derived “fossils” that can be found in many genomes, including our own [9], may represent new and old recruits in an ongoing battle for evolutionary supremacy. Such recruitments are easier to identify in genomes like Drosophila, where genes that are not under selection are quickly abraded [29], rather than in mammalian genomes, where pseudogenes can survive for tens of millions of years. In both cases, only detailed investigations of function or selective constraint can ascertain whether a retroviral remnant has been functionally retained, or is simply a paleontological relic of a past infection.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila strains.

Drosophila strains used in this study were obtained from the Drosophila Species Stock Center (Tucson, Arizona, United States), except for the Zimbabwe strains of D. melanogaster that were a gift from Y. Chen and W. Stephan.

PCR.

PCR was used to amplify the Iris coding region from Drosophila species using degenerate primers designed to Iris, CG4715degF: 5′- CTGGTGGACACCGAAACACCNTACYTNGG-3′, and to a conserved gene found downstream and in opposite orientation to Iris (CG4552)-primer CG4552degF: 5′- GCGACCTCATCACGTTYAARTAYGG-3′ (Figure 1A). This pair of primers enabled the amplification of the 3′ end of the Iris coding region and the design of species-specific primers. For all strains from D. melanogaster, and sibling species D. simulans, D. mauritiana, and D. sechellia, we employed specific primers CG4715eATG: 5′- AACGATCACCTCTACAAGCGAAAGATG-3′, and CG4715R2: 5′- GAAGACTGGTTCCGTATGGCCGC-3′ in forward and reverse orientations, respectively, to get the complete coding Iris sequence. In the case of the other Drosophila species, we employed a forward primer 500 base pairs upstream of CG715: 5′- CACTTCGACTGTTCTGAATGAACTGACG-3′ to obtain nearly the entire coding region, in conjunction with primers designed specifically to the 3′ end of the particular Iris gene from that species. Specific primers to D. pseudoobscura and D. ananassae were made based on the draft sequences of the genome from the two species. The A. gambiae sequence was directly obtained from the Anopheles genome sequence, while the A. aegypti sequence was reconstructed using synteny to Anopheles, from the database of trace sequences. Sequences of the Kanga and roo retroviruses were obtained from the ongoing genome sequencing efforts in 12 Drosophila species. Most products were directly sequenced using ABI Big-Dye sequencing. In cases where PCR products were too weak to be directly sequenced, they were cloned using TopoTA cloning kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, United States) and then sequenced using vector-specific primers: at least four separate clones were sequenced for each PCR product. All sequences obtained or annotated in this study have been deposited in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank).

RT-PCR.

RT-PCR analysis was carried out on pools of polyA D. melanogaster RNA that were a gift from S. Parkhurst (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) using primers CG4715eATG and CG4715R2 (described above) using the SuperScript One Step RT-PCR System from Invitrogen.

Northern analysis.

Northern analysis was also carried out using a blot containing the same pools of polyA RNA, using D. melanogaster Iris gene PCR fragment (CG4715eATG and CG4715R2 primers) as probe. For the tissue-specific RT-PCR analysis, individual flies were dissected for ovaries, testes, carcasses, and heads. RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy Kit (Valencia, California, United States) and treated with the DNase-Free kit from Ambion (Austin, Texas, United States) to remove trace amounts of DNA. RNA amounts were measured using a spectrophotometer. Roughly equal amounts of RNA were used as template in the individual RT-PCR reactions. As a loading control, and to rule out genomic DNA contamination, a separate RT-PCR was carried out to the Karyopherin α3 gene using primers 5′- CGTTGAGCTGAGGAAGAACAAGCG-3′ and 5′-GTGGCTGCACGACTCCGTGC-3′, which span an intron, allowing cDNA to be distinguished from genomic DNA. For the Iris-B genes from D. prostipennis and D. lutescens, RNA was isolated from pooled adult male and female flies. RT-PCR was used to validate the intron positions.

Bioinformatic analyses.

We used PSI-BLAST analyses to obtain all homologous sequences to Iris (CG4715) using Iris, gypsy env, and Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus orf23 genes as search seeds, allowing the search up to three iterations. The various homologous sequences obtained by PSI-BLAST and our PCR results were aligned using CLUSTALX [67], eliminating all domains that were not unambiguously aligned in order to get a conservative alignment. Alignments were presented using the MacBoxshade program (written by M. Baron). We then used this alignment to obtain phylogenetic trees using the PAUP* suite of programs [68], employing both neighbor-joining, maximum likelihood, and maximum parsimony (heuristic) searches, followed by bootstrap analyses. The Kanga retroviral sequences used in the analysis presented in Figure 3 represent best match hits (using Iris as a query) in the individual genomes. Each hit to a retroviral env gene was used to analyze the genomic region containing the retrovirus for additional open reading frames, including the gag- and pol-like genes (used in Figure 3B). We used the SignalP program (version 3.0) to identify putative signal peptide cleavage sites [69].

Population genetic analyses.

Population genetic analyses were carried out using the DNASP program [70]. We used the program to carry out various tests for positive selection, including the McDonald-Kreitman test [47]. dN/dS ratios were computed in a sliding window using the Kestimator package [43]. Given calculated transition: transversion ratios and G+C content at third positions of codons, 1,000 trials of simulating dN equal to dS were generated. Significant deviations from neutrality (dN/dS ~1) were evaluated by comparing the range of simulated dN values to actual dN [43].

Maximum likelihood analyses.

Maximum likelihood analyses were performed with Codeml in the PAML software package [44]. Global ω ratios for the tree (Figure 8A) were calculated by a free-ratio model, which allows ω to vary along different branches. To detect selection, multiple alignments were fitted to either the F3 ×4 or F61 models of codon frequencies. Log-likelihood ratios of the data were compared using different site-specific (NSsites) models: M7 (fit to a beta distribution, ω > 1 disallowed) to M8 (similar to model 7 but ω > 1 allowed). The likelihood ratio test is performed by taking the negative of twice the log-likelihood difference between the two models and comparing this to the χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of parameters between the models. In all cases, permitting sites to evolve under positive selection gave a much better fit to the data (Table 1). These analyses also identified certain amino acid residues with high posterior probabilities (greater than 0.95) of having evolved under positive selection under the naïve empirical Bayes (NEB) model (Table 1 and Figure 8B). A more conservative Bayes empirical Bayes (BEB) evaluation of whether codons had evolved under positive selection was also carried out. REL and FEL analyses were carried out using the online server at http://www.datamonkey.org [45,71].

Supporting Information

Accession Numbers

The GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank) accession numbers in this paper are: Iris-A sequences (DQ 177366–DQ177418) and Iris-B sequences (DQ 185599–DQ 185602).

The FlyBase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu) accession numbers in this paper are: CG4715 orthologs (FBgn0031305) and Anopheles gambiae homolog of CG4715 (XP_314732).

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Parkhurst and Miriam Rosenberg for the RNA pools and Northern blots, and Danielle Vermaak for help with the RNA isolation, RT-PCR analysis, helpful discussions, and constructive criticism. We also thank George Rohrmann for helpful comments, encouragement, and advice throughout this project. We thank Josh Bayes, Michael Emerman, Scott Goeke, Julie Kerns, Katie Peichel, Sara Sawyer, Danielle Vermaak and especially one anonymous reviewer for their helpful suggestions on the manuscript. This work was initially supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation to HSM and funds from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to SH. HSM is currently supported by startup funds from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and by a Searle Scholar Award from the Kinship Foundation. HSM is an Alfred P. Sloan Fellow in Computational and Evolutionary Molecular Biology.

Abbreviations

- BEB

Bayes empirical Bayes

- dN

number of replacement changes per site

- dS

number of synonymous changes per site

- env

envelope

- FEL

fixed effects likelihood

- NEB

naïve empirical Bayes

- REL

random effects likelihood

- SA

splice acceptor

- SD

splice donor

Footnotes

Competing interests. The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author contributions. HSM conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, and analyzed the data. HSM and SH wrote the paper.

References

- Nakamura TM, Morin GB, Chapman KB, Weinrich SL, Andrews WH, et al. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science. 1997;277:955–959. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickbush TH. Telomerase and retrotransposons: Which came first? Science. 1997;277:911–912. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardue ML, DeBaryshe PG. Retrotransposons provide an evolutionarily robust non-telomerase mechanism to maintain telomeres. Annu Rev Genet. 2003;37:485–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.093115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis RW, Ganesan R, Houtchens K, Tolar LA, Sheen FM. Transposons in place of telomeric repeats at a Drosophila telomere. Cell. 1993;75:1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90318-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Eastman QM, Schatz DG. Transposition mediated by RAG1 and RAG2 and its implications for the evolution of the immune system. Nature. 1998;394:744–751. doi: 10.1038/29457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melek M, Gellert M, van Gent DC. Rejoining of DNA by the RAG1 and RAG2 proteins. Science. 1998;280:301–303. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit AF, Riggs AD. Tiggers and DNA transposon fossils in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1443–1448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit AF. Interspersed repeats and other mementos of transposable elements in mammalian genomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:657–663. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff J, Korting C, Schartl M. Ty3/Gypsy retrotransposon fossils in mammalian genomes: Did they evolve into new cellular functions? Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:266–270. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best S, Le Tissier P, Towers G, Stoye JP. Positional cloning of the mouse retrovirus restriction gene Fv1 . Nature. 1996;382:826–829. doi: 10.1038/382826a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Lee X, Li X, Veldman GM, Finnerty H, et al. Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature. 2000;403:785–789. doi: 10.1038/35001608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Takenaka O, Crow TJ. Isolation and phylogeny of endogenous retrovirus sequences belonging to the HERV-W family in primates. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2613–2619. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-10-2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet F, Bouton O, Prudhomme S, Cheynet V, Oriol G, et al. The endogenous retroviral locus ERVWE1 is a bona fide gene involved in hominoid placental physiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1731–1736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305763101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnaud B, Bouton O, Oriol G, Cheynet V, Duret L, et al. Evidence of selection on the domesticated ERVWE1 env retroviral element involved in placentation. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1895–1901. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frendo JL, Olivier D, Cheynet V, Blond JL, Bouton O, et al. Direct involvement of HERV-W Env glycoprotein in human trophoblast cell fusion and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3566–3574. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3566-3574.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaise S, de Parseval N, Benit L, Heidmann T. Genomewide screening for fusogenic human endogenous retrovirus envelopes identifies syncytin 2, a gene conserved on primate evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13013–13018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132646100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A, Marceau G, Vernochet C, Benit L, Kanellopoulos C, et al. Syncytin-A and syncytin-B, two fusogenic placenta-specific murine envelope genes of retroviral origin conserved in Muridae . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:725–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406509102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame IG, Cutfield JF, Poulter RT. New BEL-like LTR-retrotransposons in Fugu rubripes, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster . Gene. 2001;263:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik HS, Henikoff S, Eickbush TH. Poised for contagion: Evolutionary origins of the infectious abilities of invertebrate retroviruses. Genome Res. 2000;10:1307–1318. doi: 10.1101/gr.145000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickbush TH, Malik HS. Origins and evolution of retrotransposons. In: Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz AM, editors. Mobile DNA II. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2002. pp. 1111–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann GF, Karplus PA. Relatedness of baculovirus and gypsy retrotransposon envelope proteins. BMC Evol Biol. 2001;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MN, Groten C, Rohrmann GF. Identification of the lymantria dispar nucleopolyhedrovirus envelope fusion protein provides evidence for a phylogenetic division of the Baculoviridae . J Virol. 2000;74:6126–6131. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6126-6131.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MN, Rohrmann GF. Conservation of a proteinase cleavage site between an insect retrovirus (gypsy) Env protein and a baculovirus envelope fusion protein. Virology. 2004;322:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MN, Russell RL, Rohrmann GF. Functional analysis of a conserved region of the baculovirus envelope fusion protein, LD130. Virology. 2002;304:81–88. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, Evans CA, Gocayne JD, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster . Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminker JS, Bergman CM, Kronmiller B, Carlson J, Svirskas R, et al. The transposable elements of the Drosophila melanogaster euchromatin: A genomics perspective. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0084. DOI: 10.1186/gb-2002–3–12-research0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen NJ, McDonald JF. Drosophila euchromatic LTR retrotransposons are much younger than the host species in which they reside. Genome Res. 2001;11:1527–1540. doi: 10.1101/gr.164201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov DA, Lozovskaya ER, Hartl DL. High intrinsic rate of DNA loss in Drosophila . Nature. 1996;384:346–349. doi: 10.1038/384346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung O, Blissard GW. A cellular Drosophila melanogaster protein with similarity to baculovirus F envelope fusion proteins. J Virol. 2005;79:7979–7989. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.7979-7989.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo CA, Takezaki N, Nei M. Molecular phylogeny and divergence times of Drosophilia species. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:391–404. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhang YP, Qian YH, Zeng QT. Phylogenetic relationships of Drosophila melanogaster species group deduced from spacer regions of histone gene H2A-H2B . Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;30:336–343. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Cases in which parsimony or compatibility methods will be positively misleading. Syst Zool. 1978;27:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Milne AA, Shepard EH. The complete tales and poems of Winnie-The-Pooh. New York: Dutton Books; 2001. 557. p. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz EM, Hogness DS. Molecular organization of a Drosophila puff site that responds to ecdysone. Cell. 1982;28:165–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer G, Tschudi C, Perera J, Delius H, Pirrotta V. B104, a new dispersed repeated gene family in Drosophila melanogaster and its analogies with retroviruses. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:435–451. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi M, Nuttall R, Edwards P, Minor J, Naiman D, et al. A survey of ovary-, testis-, and soma-biased gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster adults. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R40. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-6-r40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Gribskov M. Methods and statistics for combining motif match scores. J Comput Biol. 1998;5:211–221. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1998.5.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MN, Rohrmann GF. Transfer, incorporation, and substitution of envelope fusion proteins among members of the Baculoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, and Metaviridae (insect retrovirus) families. J Virol. 2002;76:5301–5304. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5301-5304.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurminsky DI, Nurminskaya MV, De Aguiar D, Hartl DL. Selective sweep of a newly evolved sperm-specific gene in Drosophila . Nature. 1998;396:572–575. doi: 10.1038/25126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi CF, Bonhomme F, Buckler-White A, Buckler C, Orth A, et al. Molecular phylogeny of Fv1 . Mamm Genome. 1998;9:1049–1055. doi: 10.1007/s003359900923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Laigret F, Martin MA, Repaske R. Characterization of a molecularly cloned retroviral sequence associated with Fv-4 resistance. J Virol. 1985;55:768–777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.3.768-777.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeron JM. K-Estimator: Calculation of the number of nucleotide substitutions per site and the confidence intervals. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:763–764. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.9.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wong WS, Nielsen R. Bayes empirical bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1107–1118. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond SL, Frost SD. Datamonkey: Rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2531–2533. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SL, Wu LI, Emerman M, Malik HS. Positive selection of primate TRIM5α identifies a critical species-specific retroviral restriction domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2832–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409853102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila . Nature. 1991;351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan IK, Matyunina LV, McDonald JF. Evidence for the recent horizontal transfer of long terminal repeat retrotransposon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12621–12625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels SB, Peterson KR, Strausbaugh LD, Kidwell MG, Chovnick A. Evidence for horizontal transmission of the P transposable element between Drosophila species. Genetics. 1990;124:339–355. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gracia A, Maside X, Charlesworth B. High rate of horizontal transfer of transposable elements in Drosophila . Trends Genet. 2005;21:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliman RM, Andolfatto P, Coyne JA, Depaulis F, Kreitman M, et al. The population genetics of the origin and divergence of the Drosophila simulans complex species. Genetics. 2000;156:1913–1931. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.4.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting CT, Tsaur SC, Wu CI. The phylogeny of closely related species as revealed by the genealogy of a speciation gene, Odysseus . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5313–5316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090541597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting CT, Tsaur SC, Wu ML, Wu CI. A rapidly evolving homeobox at the site of a hybrid sterility gene. Science. 1998;282:1501–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CI, Hollocher H, Begun DJ, Aquadro CF, Xu Y, et al. Sexual isolation in Drosophila melanogaster: A possible case of incipient speciation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2519–2523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. The origins and evolution of viruses. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:61. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01934-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temin HM. Origin of retroviruses from cellular moveable genetic elements. Cell. 1980;21:599–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YT, Lyu MS, Buckler-White A, Kozak CA. Characterization of a polytropic murine leukemia virus proviral sequence associated with the virus resistance gene Rmcf of DBA/2 mice. J Virol. 2002;76:8218–8224. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8218-8224.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Sugimura H. Fv-4 resistance gene: A truncated endogenous murine leukemia virus with ecotropic interference properties. J Virol. 1989;63:5405–5412. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5405-5412.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SP. Retrovirus restriction factors. Mol Cell. 2004;16:849–859. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SU, Kurkulos M, Boeke JD, Corces VG. Infection of the germ line by retroviral particles produced in the follicle cells: A possible mechanism for the mobilization of the gypsy retroelement of Drosophila. Development. 1997;124:2789–2798. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc P, Desset S, Giorgi F, Taddei AR, Fausto AM, et al. Life cycle of an endogenous retrovirus, ZAM, in Drosophila melanogaster . J Virol. 2000;74:10658–10669. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10658-10669.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalvet F, Teysset L, Terzian C, Prud''homme N, Santamaria P, et al. Proviral amplification of the Gypsy endogenous retrovirus of Drosophila melanogaster involves env-independent invasion of the female germline. Embo J. 1999;18:2659–2669. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelisson A, Mejlumian L, Robert V, Terzian C, Bucheton A. Drosophila germline invasion by the endogenous retrovirus gypsy: Involvement of the viral env gene. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1249–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SU, Gerasimova T, Kurkulos M, Boeke JD, Corces VG. An env-like protein encoded by a Drosophila retroelement: Evidence that gypsy is an infectious retrovirus. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2046–2057. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.17.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syomin BV, Fedorova LI, Surkov SA, Ilyin YV. The endogenous Drosophila melanogaster retrovirus gypsy can propagate in Drosophila hydei cells. Mol Gen Genet. 2001;264:588–594. doi: 10.1007/s004380000344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Valen L. A new evolutionary law. Evolutionary Theory. 1973;1:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), 4th edition [computer program] Sunderland (Massachusetts): Sinauer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SD. Not so different after all: A comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1208–1222. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzio J, Pearson MN, Harwood SH, Funk CJ, Evans JT, et al. Sequence and analysis of the genome of a baculovirus pathogenic for Lymantria dispar . Virology. 1999;253:17–34. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlor RL, Parkhurst SM, Corces VG. The Drosophila melanogaster gypsy transposable element encodes putative gene products homologous to retroviral proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:1129–1134. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.4.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]