Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy is an effective treatment for relapsed-refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL). However, toxicities, particularly cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), remain significant concerns. Analyze temporal trends, risk factors, and associations between these toxicities and their severity. In this registry study by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, we studied CRS and ICANS in 1916 LBCL patients treated with commercial CAR-T therapies (axicabtagene ciloleucel 74.9%, tisagenlecleucel 25.1%) between 2018 and 2020. Outcomes include development of CRS/ICANS, timing and severity according to ASTC grading, overall survival (OS). Risk factors were assessed using Cox proportional hazards model. Among patients developing CRS (75.2%), 11.3% had grade ≥3 CRS. Among patients developing ICANS (43.5%), 47.7% had grade ≥3 ICANS. Among patients developing CRS, severe CRS rates decreased from 14.0% in 2018 to 9.2% in 2020 (P < .01). However, the proportion of severe ICANS in patients who developed ICANS remained statistically unchanged (41.5% in 2018 to 53.7% in 2020, P = .10). CRS and ICANS were correlated: 57.1% of patients with CRS also experienced ICANS, and CRS was reported in 97.5% of ICANS cases, suggesting a potential continuum between toxicities. Axicabtagene ciloleucel was associated with higher risk of any grade CRS (OR, 4.6; 95% CI, 3.65 to 5.81) and ICANS (OR, 5.85; 95% CI, 4.48 to 7.64) as well as early and severe forms of both complications. Older age, lower performance status, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels prior to infusion also variably predicted these toxicities. In a landmark analysis starting 30 days postinfusion, patients with severe CRS or severe ICANS had shorter OS compared to those without these toxicities. High grades of CRS improved over time likely related to earlier intervention, development of ICANS is intrinsically related with CRS. These findings underscore the need for effective strategies to mitigate these toxicities and improve CAR-T safety.

Keywords: CAR T Cell toxicities, Large B-cell lymphoma, Cytokine release syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Background

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy has ushered in a new era in the management of patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL), demonstrating unprecedented efficacy [1]. Despite these transformative outcomes, the clinical landscape of CAR-T therapy is not without challenges, and the occurrence of treatment-related toxicities remains a significant concern.

The primary toxicities associated with CAR-T therapy, namely cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), constitute important aspects of patient care. CRS is a systemic inflammatory response triggered by the activation and proliferation of CAR-T cells, often presenting with fever, hypotension, and respiratory distress. Similarly, ICANS involves neurologic symptoms, ranging from mild confusion to severe encephalopathy [2,3]. The American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy developed consensus grading for CRS and ICANS. These allow uniform definitions across products and varied study settings [3].

Various factors, including patients’ characteristics and disease- and treatment-related features [2,4–11], have been implicated in the increased risk of CAR-T therapy toxicity. However, previous studies have often been limited by small cohort sizes and potentially underpowered analyses, which hindered the identification of additional risk factors. Existing models frequently lack comprehensiveness, overlooking the interplay of multiple factors that collectively contribute to toxicity risk. Additionally, clinical practice may have changed over time, since there is growing evidence that tocilizumab and steroids are safe for managing CAR-T toxicities [4,12–14]. As physicians become more comfortable using these treatments, there could be a shift in toxicity profiles that was not captured in previous reports.

Objectives

To address these gaps, our study leverages a large and diverse population in the real-world setting to comprehensively evaluate the patterns, risk factors, and implications of CRS and ICANS following CD19 CAR-T therapy in LBCL.

METHODS

Participants

Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) is a research collaboration between the Medical College of Wisconsin and NMDP. More than 350 medical centers worldwide submit clinical data to CIBMTR about hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) and cellular therapies, including CAR-Ts [15–19]. CIBMTR’s Research Database includes long-term clinical data from more than 22,000 patients worldwide who received CAR-Ts and other adoptive cellular therapies. Data are submitted before infusion and then during follow-up visits at 3 months, 6 months, and yearly; CIBMTR has automated and manual checks to ensure data quality.

Using the CIBMTR registry, we identified adult patients with relapsed or refractory LBCL who received commercially available CAR-T cell therapy following US Food and Drug Administration approval, with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel, approved in 2017) and tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel, approved in 2018), until December 2020.

Outcomes and Definitions

The frequencies of CRS and ICANS were evaluated based American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy criteria [3]. Both conditions were assessed as binary outcomes (presence or absence) and further categorized by severity, with grades above 3 classified as severe. Additionally, they were grouped by time to onset, defined as early or late, based on the median time to onset for each condition. Bridging therapy was defined as any therapy that started or ended in the period between leukapheresis and CAR-T infusion. Progression-free survival was defined as the time from CAR-T to relapse, progression, or death from any cause. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from treatment to death from any cause. Treatment-related mortality (TRM) encompassed deaths occurring in patients without lymphoma relapse or progression. TRM and disease relapse or progression were considered as competing events and were reported using cumulative incidence estimates.

DATA SOURCE AND QUALITY

CIBMTR performs automated and manual data quality checks and on-site audits. These validations and verifications produce high-quality data. If a center fails to meet data quality standards, its data are removed from research studies.

Ethics

The NMDP Institutional Review Board reviews CIBMTR’s research. Patients or guardians give informed consent for research.

Statistical Methods

Patient, disease, and CAR-T factors were compared between groups, using chi-square test for categorical variables and Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. Frequencies and proportions were reported for overall CRS, severe CRS, early CRS, overall ICANS, severe ICANS, and early ICANS. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were summarized for time from infusion to CRS onset, time from CRS onset to resolution, time from infusion to ICANS onset, and time from ICANS onset to resolution. To investigate the relationship between CRS and ICANS, alluvial plots were generated, and a cross-table was shown. The Kaplan–Meier estimates were calculated for OS to compare CRS groups and ICANS groups.

Logistic regression models were used to assess the effects of risk factors on overall CRS, severe CRS, rapid onset of CRS, overall ICANS, severe ICANS, and rapid onset of ICANS. For the rapid onset, the median time for development of CRS and ICANS was used to discriminate these cases. Patients with time to onset of CRS and ICANS shorter than the median time were classified as having rapid onset. A stepwise selection method was used to identify the significant factors associated with overall CRS and overall ICANS at a significance level of 0.01. Since CRS and ICANS typically occur within the first 30 days after CAR-T infusion, a landmark analysis at day 30 to assess the development and severity of each event associated with OS. This approach accounts for the time-dependent nature of these events by including only patients who survived beyond day 30, reducing immortal time bias.

The landmark analysis used Cox proportional hazards model with day 30 as the set start time. The proportional hazard assumption for each factor was tested. If not valid, time-dependent variables were used. A stepwise variable selection method was used to identify significant risk factors for OS at a significance level of 0.01. Variables tested in the multivariable analysis included age, sex, body mass index, performance score, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) prior to infusion, prior lines of therapy, prior HCT and HCT timing, disease status prior to CAR-T infusion, disease burden prior to CAR-T infusion, primary indication being a doubleor triplehit lymphoma, and CAR-T product. For the landmark analysis, development and severity of CRS and ICANS post CAR T Cell infusion was tested as additional variables. Additionally, center effects and pairwise interactions between significant factors were tested. All analyses were performed using SAS and R statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, version 4.2.0).

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 1916 patients were included in the study (Table 1), with a median age of 63.6 years (IQR 55.1 to 69.9). The Karnofsky Performance Status was 90 to 100 and 80 in 38.8% and 28.6% of patients, respectively. Most patients had de novo LBCL, without evidence of lymphoma transformation (65.9%). Prelymphodepletion elevated LDH was reported in 43.6% of patients. Most patients did not receive bridging therapy (66.6%), and axicel was the predominant CAR-T product (74.9%).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1916 |

| No. of centers | 97 |

| Baseline characteristics | |

| Age at infusion, years | |

| Median (interquartile range) | 63.6 (55.1–69.9) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |

| Male | 1225 (63.9) |

| Female | 691 (36.1) |

| Recipient race, no. (%) | |

| White | 1538 (80.3) |

| Black or African American | 96 (5.0) |

| Asian | 84 (4.4) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 5 (0.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 6 (0.3) |

| More than one race | 8 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 85 (4.4) |

| Not reported | 94 (4.9) |

| Karnofsky Performance score prior to CAR-T therapy, no. (%) | |

| 90–100 | 744 (38.8) |

| 80 | 548 (28.6) |

| <80 | 373 (19.5) |

| Not reported | 251 (13.1) |

| Disease-related variables | |

| Double- or triple-hit lymphoma at initial diagnosis, no. (%) | |

| Neither | 767 (40.0) |

| Double- or triple-hit | 265 (13.8) |

| Not reported | 884 (46.1) |

| Transformed lymphoma, no. (%) | |

| No | 1262 (65.9) |

| Yes | 461 (24.1) |

| Presence of CNS disease at any time prior to infusion, no. (%) | |

| No | 1751 (91.4) |

| Yes | 72 (3.8) |

| Not reported | 93 (4.9) |

| Elevated LDH prior to CAR-T therapy, no. (%) | |

| No | 724 (37.8) |

| Yes | 836 (43.6) |

| Not reported | 356 (18.6) |

| Types of prior HCTs, no. (%) | |

| No prior HCT | 1382 (72.1) |

| Prior autoHCT | 496 (25.9) |

| Prior alloHCT | 27 (1.4) |

| Prior auto and alloHCT | 5 (0.3) |

| Not reported | 6 (0.3) |

| Disease status at infusion, no. (%) | |

| CR | 73 (3.8) |

| PR | 192 (10.0) |

| Resistant | 1648 (86.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.2) |

| CAR-T-related variables | |

| Year of CAR-T therapy, no. (%) | |

| 2018 | 380 (19.8) |

| 2019 | 900 (47.0) |

| 2020 | 636 (33.2) |

| Product, no. (%) | |

| Tisa-cel | 481 (25.1) |

| Axi-cel | 1435 (74.9) |

| Bridging therapy type, no. (%) | |

| None | 1276 (66.6) |

| Systemic ± radiation | 339 (17.7) |

| Radiation | 91 (4.7) |

| Other therapy | 5 (0.3) |

| Not reported | 205 (10.7) |

| Lymphodepleting chemotherapy, no. (%) | |

| Bendamustine | 96 (5.0) |

| Cyclophosphamide/fludarabine | 1816 (94.8) |

alloHCT indicates hematopoietic cell transplantation; autoHCT, autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation; axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy; CNS, central nervous system; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; tisa-cel, tisagenlecleucel.

Over the study period (2018 to 2020), patient characteristics shifted (Table S1). The median age increased from 62.3 years in 2018 to 64.5 years in 2020 (P < .01). Bridging rates increased from 26.1% to 36.9% in 2020 (P < .01), alongside a rise in tisa-cel administration (15.3% to 31.3%, P < .01). Compared patients who received tisa-cel (Table S2), patients receiving axi-cel were younger (P < .01), had higher Karnofsky Performance Status scores (P < .01), exhibited higher LDH levels before lymphodepletion (P < .01), and were less likely to undergo bridging therapy (P < .01).

CRS and ICANS: Prevalence, Severity, and Temporal Patterns

CRS and ICANS were common following CAR-T cell therapy (Table S3). CRS occurred in 75.2% of patients, with the majority of cases being mild to moderate (grades 1 to 2, 88.7%). Severe CRS (grades 3 to 4) was observed in 11.3% of patients (Figure 1A,B). The incidence of CRS varied significantly between CAR-T products, with higher rates in patients treated with axi-cel (83%) compared to tisa-cel (51.8%, P < .01). Rates of severe CRS were also statistically higher with axi-cel (11.4% versus 10.8%, P = .01). The median time to CRS onset was 4 days (IQR 2 to 6), and the median duration was 6 days (IQR 2 to 6). Tocilizumab was administered to 63.4% of patients with CRS, with higher usage in the axi-cel group (67.4%) compared to the tisa-cel group (44.2%, P < .01). Similarly, corticosteroid use for CRS was also higher with axi-cel (P < .01, Table S3). Tocilizumab and corticosteroid treatment was used in the majority of patients who developed CRS grade ≥3 (Table S4).

Figure 1. Distribution of CRS and ICANS grades overall and across CAR-T products.

Stacked bar plots show the distribution of grades of (A and B) CRS and (C and D) ICANS across CAR-T products. Panels A and C reflect grades of CRS and ICANS in the complete cohort, while panels B and D show grades of CRS and ICANS among patients developing these conditions, respectively. CRS indicates cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity.

ICANS occurred in 43.5% of patients, with 47.7% of these cases classified as severe (Table S3). The incidence of ICANS also differed between CAR-T products (Figure 1C,D), with a higher rate in patients receiving axi-cel (51.8%) compared to tisa-cel (18.7%, P < .01). Among patients who developed ICANS, severe cases were more frequent (P < .01) in the axi-cel group (49.1%) compared to the tisa-cel group (36.7%). The median time to ICANS onset was 7 days (IQR 5 to 9), with a median duration of 14 days (IQR 11 to 20). Steroid therapy was administered to 73.7% of patients with ICANS, with significantly higher use in the axi-cel group (75.9%) compared to the tisa-cel group (55.6%, P < .01).

Given that CAR-T administration spanned 3 years, we assessed temporal trends in associated toxicities (Table S5). In an unadjusted analysis, CRS rates remained relatively consistent across the years: 78.7% in 2018, 73.8% in 2019, and 75.0% in 2020 (Figure 2A, P = .21). Among patients who developed CRS, the incidence of severe cases decreased from 14.0% in 2018 to 9.2% in 2020 (P < .01, Figure 2B). The frequency of ICANS also declined over time, from 50.8% in 2018 to 44.3% in 2019 and 38.1% in 2020 (P < .01, Figure 2C). However, in patients who experienced ICANS, the rate of severe ICANS remained stable, with rates of 41.5% in 2018, 47.1% in 2019, and 53.7% in 2020 (P = .10, Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Temporal distribution of CRS and ICANS grades over 3 years.

Stacked bar plots show the distribution of grades of (A and B) CRS and (C and D) ICANS across different years. Panels A and C reflect grades of CRS and ICANS in the complete cohort, while panels B and D show grades of CRS and ICANS among patients developing these conditions, respectively. CRS indicates cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity.

Notably, CRS and ICANS are correlated. Among patients who developed CRS, 57.1% also experienced ICANS, and 97.5% of patients who developed ICANS were previously diagnosed with CRS. Patients without CRS exhibited a low incidence of ICANS (5%), while among those with severe CRS, 81% experienced ICANS, with 50% of these cases categorized as severe (Figure 3, Table S6).

Figure 3. Relationship between CRS and ICANS.

Alluvial plots demonstrate the relationship between CRS and ICANS. The 2 sets of horizontal stacked bars represent the distribution of CRS and ICANS across the entire population. The shaded areas that connect the 2 horizontal stacked bars indicate the density of patients with the connected CRS/ICANS profile. The plot shows CRS and ICANS grades abbreviated, where grade ≥3 represents grades 3, 4, and 5. CRS indicates cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity.

Risk Factors for CRS and ICANS Following CAR-T Therapy

In a multivariable logistic regression analysis, several risk factors for adverse events following CAR-T cell therapy were identified. Axi-cel use was consistently linked to an increased risk of CRS, including overall CRS (OR, 4.6; 95% CI, 3.7 to 5.8), severe CRS (OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.4 to 3.3), and rapid onset of CRS (≤4 days postinfusion; OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2 to 1.8], Table 2). Independent of the CAR-T product, older age (≥65 years) and low Karnofsky Performance score also emerged as significant risk factors for severe CRS, while elevated preinfusion LDH levels predicted both overall and early CRS.

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis for Overall, CRS, Rapid Onset of CRS, and ICANS

| Variable | N | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRS (no versus yes) | |||

| Sex | .006 | ||

| Female | 688 | 1 | |

| Male | 1218 | 0.72 (0.57–0.91) | .006 |

| Elevated LDH prior to CAR-T | .002 | ||

| No | 722 | 1 | |

| Yes | 832 | 1.56 (1.23–2.00) | <.001 |

| Not reported | 352 | 1.23 (0.89–1.68) | .209 |

| CAR-T product | <.001 | ||

| Tisa-cel | 478 | 1 | |

| Axi-cel | 1428 | 4.61 (3.65–5.81) | <.001 |

| Severe CRS (≥3 grade versus <3 grade and no CRS) | |||

| Age | .005 | ||

| <65 years | 1061 | 1 | |

| ≥65 years | 841 | 1.60 (1.15–2.23) | .005 |

| KPS prior to CAR-T | <.001 | ||

| 90–100 | 738 | 1 | |

| 80 | 547 | 1.63 (1.05–2.54) | .031 |

| <80 | 370 | 3.32 (2.16–5.10) | <.001 |

| Not reported | 247 | 1.53 (0.87–2.72) | .143 |

| CAR-T product | .001 | ||

| Tisa-cel | 478 | 1 | |

| Axi-cel | 1424 | 2.11 (1.36–3.29) | .001 |

| Rapid Onset of CRS (≤4 days versus >4 days CRS or no CRS) | |||

| Elevated LDH prior to CAR-T | <.001 | ||

| No | 722 | 1 | |

| Yes | 832 | 1.67 (1.36–2.05) | <.001 |

| Not reported | 352 | 1.25 (0.96–1.63) | .095 |

| CAR-T product | .001 | ||

| Tisa-cel | 478 | 1 | |

| Axi-cel | 1428 | 1.46 (1.17–1.81) | .001 |

| ICANS (no versus yes) | |||

| Age | <.0001 | ||

| <65 years | 1057 | 1.00 | |

| ≥65 years | 835 | 1.83 (1.50–2.24) | <.0001 |

| KPS prior to CAR-T | <.0001 | ||

| 90–100 | 733 | 1.00 | |

| 80 | 542 | 1.17 (0.92–1.49) | .19 |

| <80 | 371 | 2.48 (1.88–3.27) | <.0001 |

| Not reported | 246 | 1.52 (1.11–2.09) | .01 |

| Disease status at infusion | |||

| Complete response | 72 | 1.00 | .0001 |

| Partial response | 434 | 1.30 (0.70–2.41) | .40 |

| Resistant | 1222 | 1.98 (1.10–3.58) | .02 |

| Untreated/not reported | 164 | 2.62 (1.35–5.10) | .004 |

| CAR-T product | <.0001 | ||

| Tisa-cel | 478 | 1.00 | |

| Axi-cel | 1414 | 5.85 (4.48–7.64) | <.0001 |

| Severe ICANS (≥3 grade versus <3 grade and no ICANS) | |||

| Age | .0003 | ||

| <65 years | 1029 | 1.00 | |

| ≥65 years | 810 | 1.56 (1.22–1.98) | .0003 |

| KPS prior to CAR-T | <.0001 | ||

| 90–100 | 713 | 1.00 | |

| 80 | 533 | 1.24 (0.90–1.70) | .18 |

| <80 | 356 | 2.85 (2.07–3.93) | <.0001 |

| Not reported | 237 | 2.76 (1.91–3.99) | <.0001 |

| Elevated LDH prior to CAR-T | .007 | ||

| No | 694 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 799 | 1.52 (1.15–2.00) | .003 |

| Not reported | 346 | 1.09 (0.77–1.55) | .62 |

| CAR-T product | <.0001 | ||

| Tisa-cel | 478 | 1.00 | |

| Axi-cel | 1361 | 5.65 (3.82–8.35) | <.0001 |

| Rapid Onset ICANS (≤7 days versus >7 days ICANS and no ICANS) | |||

| Age | <.0001 | ||

| <65 years | 1057 | 1.00 | |

| ≥65 years | 835 | 1.73 (1.40–2.15) | <.0001 |

| KPS prior to CAR-T | <.0001 | ||

| 90–100 | 733 | 1.00 | |

| 80 | 542 | 1.19 (0.91–1.55) | .21 |

| <80 | 371 | 2.07 (1.56–2.76) | <.0001 |

| Not reported | 246 | 1.45 (1.03–2.05) | .04 |

| Elevated LDH prior to CAR-T | .0055 | ||

| No | 718 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 821 | 1.40 (1.10–1.79) | .006 |

| Not reported | 353 | 0.97 (0.71–1.32) | .82 |

| CAR-T product | <.0001 | ||

| Tisa-cel | 478 | 1.00 | |

| Axi-cel | 1414 | 4.02 (2.95–5.49) | <.0001 |

axi-cel indicates axicabtagene ciloleucel; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; OR, odds ratio; tisa-cel, tisagenlecleucel.

Similar patterns were observed for ICANS. Axicel use was associated with a substantial increase in overall ICANS (OR, 5.9; 95% CI, 4.5 to 7.6), severe ICANS (OR, 5.7; 95% CI, 3.8 to 8.4), and rapid onset ICANS (≤7 days postinfusion; OR, 4.0; 95% CI, 3.0 to 5.5). Age ≥65 years and low Karnofsky Performance score were also identified as independent risk factors for ICANS (Table 2), while elevated LDH predicted both early and severe ICANS.

In summary, these analyses highlight axi-cel as a significant contributor to the increased risk of both CRS and ICANS, particularly in their severe and rapid onset forms. Additionally, older age, lower performance status, and elevated LDH were key factors associated with heightened toxicity risk.

Prognostic Implications of Severe CRS and ICANS in CAR-T Therapy

The best objective response rate was 68.6%, with a complete response rate of 52.4% and a partial response rate of 16.2%. Over a median follow-up of 14.2 months (range 0.7 to 39.1) from CAR-T infusion, the estimated 1-year OS probability was 61.6% (95% CI, 59.4 to 63.9), and the 1-year progression-free survival was 42.2% (95% CI, 39.9 to 44.5). The cumulative incidence of relapse or progression at 1 year was 54.9% (95% CI, 52.5 to 57.2), while TRM at 1 year was 4.3% (95% CI, 3.4 to 5.3). Notably, deaths directly attributed to CRS and ICANS, as reported by centers, accounted for approximately 2% of the total fatalities (Table S7).

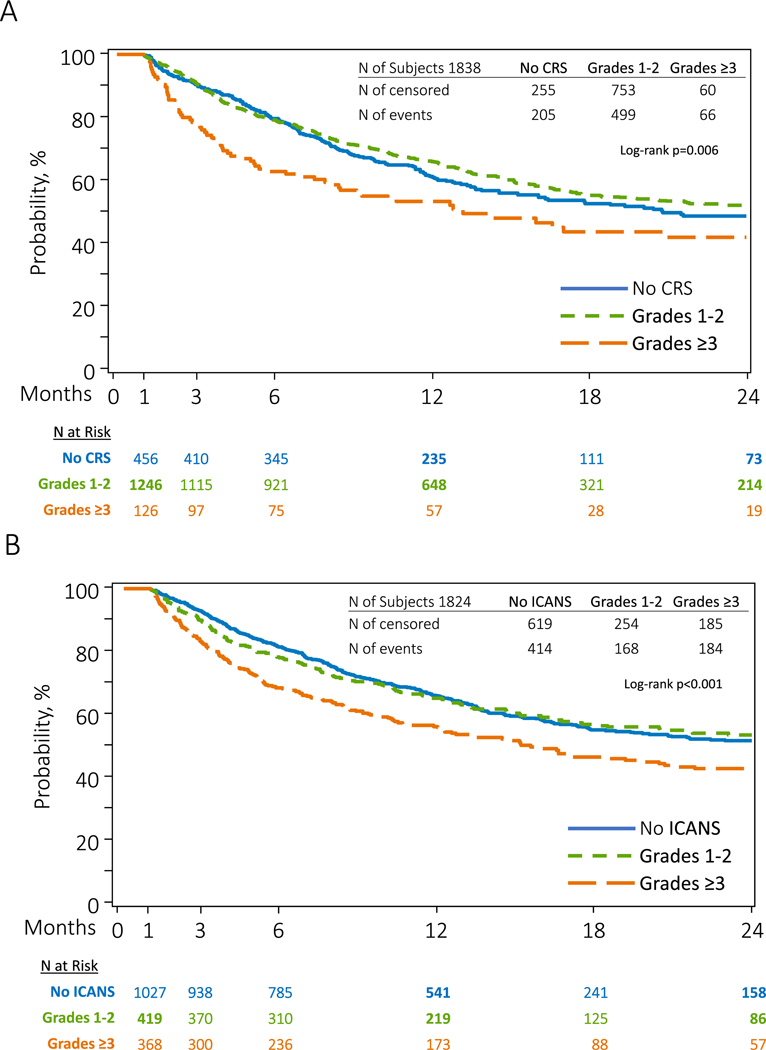

In a day-30 landmark analysis from CAR-T infusion, severe CRS was significantly associated with decreased OS in a multivariable Cox regression analysis (hazard ratio [HR], 1.44; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.87), Figure 4A; Table S8), whereas lower-grade CRS did not impact OS. Similarly, severe ICANS was linked to decreased OS compared to no ICANS (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.59), Figure 4B, Table S9). Additionally, early ICANS (≤7 days from infusion) was associated with decreased OS (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.44), whereas late-onset ICANS did not show a similar association.

Figure 4. Association between CRS and ICANS grades and overall survival.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival estimates by CRS (A) and ICANS (B) status. In this landmark analysis, follow-up days are measured from 30 days after CAR-T infusion. CRS indicates cytokine release syndrome; ICANS, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity.

DISCUSSION

In this large multicenter registry study, we found that CRS and ICANS remain significant toxicities following CD19 CAR-T therapy for LBCL, affecting up to 75% and 43% of patients, respectively. Notably, ICANS occurrence without CRS was rare (<3%), suggesting these 2 syndromes may represent a continuum. While the overall rates of these toxicities have declined over time, severe ICANS stands out as an exception, posing a formidable challenge. The risk of developing CRS and ICANS varies markedly based on patient and treatment characteristics. Axi-cel use, in particular, is strongly associated with a higher risk of both CRS and ICANS, including their severe and early manifestations. Additionally, older age, lower performance status, and elevated LDH levels emerged as independent risk factors for severe toxicities. Patients who developed severe forms of these toxicities had shorter OS, underscoring the need for preventive strategies. Despite differences in CRS and ICANS incidences by CAR-T product, the impact on survival of CRS and ICANS once they occurred were not different based on CAR-T product.

Context

In the ZUMA-1 study, the rates of CRS and severe CRS following axi-cel infusion were 93% and 13%, respectively, while the rates of ICANS and severe ICANS were 64% and 28%. In the JULIET study, tisa-cel was associated with CRS and severe CRS rates of 58% and 22%, and ICANS and severe ICANS rates of 21% and 12% [20,21]. Although direct comparisons between these pivotal trials and our observational cohort are complicated by differences in grading systems [22], the results in the CIBMTR appear comparable.

These observations underscore the significant clinical burden of these toxicities. Beyond their immediate life-threatening implications, CRS and ICANS severely compromise patients’ quality of life, often necessitating hospitalization and substantially increasing resource utilization [23]. Recognizing the gravity of these adverse events, there is a pressing need for effective strategies to prevent and manage them. These strategies include the judicious early use of tocilizumab and steroids, pre-emptive pharmacologic interventions, personalized dosing regimens, and careful monitoring of high-risk patients [12,14,24–27]. Ultimately, improving the management of CRS and ICANS is essential for enhancing patient outcomes and optimizing the effectiveness of CAR-T therapy.

In the absence of prospective randomized trials, the current analysis, together with other studies, provides valuable insights for tailoring CAR-T treatment strategies in LBCL. One key consideration is the choice of CAR-T product. Our findings are consistent with existing evidence, suggest that tisa-cel may be a less toxic option [28–30], particularly for older, frail, or comorbid patients, due to its lower rates of severe toxicity. However, reports of greater efficacy with axi-cel over tisacel [28,31] indicate that further research is needed to determine which patients would benefit most from tisa-cel. Additionally, recognizing disease burden as a modifiable risk factor for CRS and ICANS highlights the potential benefits of bridging therapy [11,32–34]. Effective cytoreduction with bridging may contribute to sustained disease control following CAR-T [35,36] and may improve CAR-T therapy toxicity profile. There is a need for multifaceted prediction models that consider patient, disease, and treatment characteristics. This would better equip clinicians to personalize treatment decisions.

We find that ICANS rarely occurs in the absence of CRS. Furthermore, severe ICANS is correlated with severe CRS, suggesting these 2 syndromes represent a continuum in CAR-T therapy. This hypothesis is supported by the shared underlying in vivo and peak CAR-T expansion and the subsequent inflammatory pathways that drive both CRS and ICANS [2,25,37]. Cytokine-mediated activation of endothelial cells and the subsequent disruption of the blood-brain barrier are instrumental factors in the pathophysiology of ICANS [38]. The overlap between these 2 toxicities also underscores the need for integrated management strategies [2,25]. Understanding this continuum not only aids in early identification and intervention but also opens avenues for targeted therapies that could mitigate both CRS and ICANS simultaneously, ultimately improving patient outcomes in CAR-T therapy. It is possible to hypothesize based on the presentation, temporal relationship, and response to treatment that these two clinical syndromes are associated with the kinetics of in vivo expansion. As CAR-T expansion results an inflammatory response causing CRS, it responds to cytokine blockade, it also results in crossing of the blood-brain barrier, which is related to peak expansion.

Limitations

Despite the valuable insights provided by this analysis, it has several notable limitations. The retrospective design of our study introduces inherent biases and limitations related to data availability and accuracy. Additionally, while our dataset includes patients treated with axi-cel and tisa-cel, it lacks data on lisocabtagene maraleucel, another approved CAR-T product for LBCL, limiting the comprehensiveness of our findings. Furthermore, our analysis only extends to 2020, potentially missing recent advances in CAR-T therapy, notably its approval as a second-line therapy. Nonetheless, this study remains one of the largest of its kind, offering a reflection of real-world experiences in standard-of-care settings, thereby avoiding the selection biases often present in clinical trials.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our findings highlight the intricate landscape of CAR-T therapy for LBCL, marked by a delicate balance between clinical efficacy and the significant risks of CRS and ICANS. CAR-T cell therapy has significant incidences of CRS and ICANS toxicities, with variations across different CAR-T products, and temporal trends highlighting changes in toxicity rates over time. Additionally, a notable correlation between CRS and ICANS occurrences underscores the interconnected nature of these adverse events raising, the possibility of resulting from in vivo CAR-T expansion kinetics. This comprehensive analysis serves as a benchmark in the field, identifying key factors that influence toxicity profiles and paving the way for personalized care strategies.

Our data suggest that outcomes may improve with a thorough preinfusion assessment, carefully selecting CAR-T product based on individual patient vulnerabilities and maintaining vigilant monitoring for early signs of CRS and ICANS. Ongoing research into the pathophysiology and management of these complex toxicities remains essential. As the field evolves, incorporating these insights with emerging data will refine therapeutic approaches, with the aim of further improving patient outcomes and optimizing the effectiveness of CAR-T therapy in LBCL.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2025.03.011.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jennifer Motl, RDN, Medical Writer, of Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) for providing editorial support, which was funded by MCW in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Financial Disclosure: CIBMTR is supported primarily by the Public Health Service U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); Cellular Immunotherapy Data Resource (CIDR) U24CA233032 from NCI; 75R60222C00011 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); and N00014–23-1–2057 and N00014–24-1–2057 from the Office of Naval Research. Support is also provided by the Medical College of Wisconsin, NMDP, Gateway for Cancer Research, Pediatric Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Consortium and from the following commercial entities: AbbVie; Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Adaptive Biotechnologies Corporation; ADC Therapeutics; Adienne SA; Alexion; AlloVir, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Atara Biotherapeutics; BeiGene; BioLineRX; Blue Spark Technologies; bluebird bio, inc.; Blueprint Medicines; Bristol Myers Squibb Co.; CareDx Inc.; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics, Inc.; DKMS; Editas Medicine; Elevance Health; Eurofins Viracor, DBA Eurofins Transplant Diagnostics; Gamida Cell, Ltd.; Gift of Life Biologics; Gift of Life Marrow Registry; GlaxoSmithKline; HistoGenetics; Incyte Corporation; Iovance; Janssen Research & Development, LLC; Janssen/Johnson & Johnson; Jasper Therapeutics; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Karius; Kashi Clinical Laboratories; Kiadis Pharma; Kite, a Gilead Company; Kyowa Kirin; Labcorp; Legend Biotech; Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals; Med Learning Group; Medac GmbH; Merck & Co.; Mesoblast; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; Miller Pharmacal Group, Inc.; Miltenyi Biomedicine; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; MorphoSys; MSA EDITLife; Neovii Pharmaceuticals AG; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; OptumHealth; Orca Biosystems, Inc.; OriGen Biomedical; Ossium Health, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; Pharmacyclics, LLC, An AbbVie Company; PPD Development, LP; REGiMMUNE; Registry Partners; Rigel Pharmaceuticals; Sanofi; Sarah Cannon; Seagen Inc.; Sobi, Inc.; Stemcell Technologies; Stemline Technologies; STEMSOFT; Takeda Pharmaceuticals; Talaris Therapeutics; Vertex Pharmaceuticals; Vor Biopharma Inc.; Xenikos BV. Roni Shouval reports grant support from the NIH/NCI (K08 CA282987 and P30 CA0087480).

Financial disclosure: See Acknowledgments on page XXX.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Strouse reports advisory board: Pfizer. Dr. Ahmed receives research support from Nektar, Merck, Xencor, Chimagen, Genmab, Kite/Gilead, Janssen, and Caribou. She is a member of the scientific advisory board for Chimagen, serves as a member of a data and safety monitoring board for Myeloid Therapeutics, and is a consultant for ADC Therapeutics and Kite/Gilead. Dr. Awan reports consultancy to: Loxo Oncology, BeiGene, Dava Oncology, AstraZeneca, Genmab, Adaptive Biotechnologies, BMS, AbbVie, Incyte, Kite Pharma, Caribou Biosciences, ADCT therapeutics, and received research funding from AbbVie/Pharmacyclics. Dr. Bachanova reports research funding from Citius, Incyte, and Gamida Cell; advisory board: ADC, Astra Zeneca, and CRIPSR, and DSMB Member: Miltenyi Biotech. Dr. Badar reports advisory board for MorphoSys, Takeda, and Pfizer. Dr. Bar is an employee of Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Barba reports advisory board and consultancy: Allogene, Amgen, Autolus, BMS/Celgene, Kite/Gilead, Incyte, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Novartis, Nektar, Pfizer, and Pierre Fabre. Dr. Beitinjaneh reports advisory board consultation: 2022–Kite Pharm and 2023 Autolus. Dr. Cashen reports being a member of an advisory board of Kite Pharma. Dr. Dholaria reports institutional research funding: Janssen, Angiocrine, Pfizer, Poseida, MEI, OrcaBio, Wugen, AlloVir, Adicet, BMS, Molecular template, Atara; Consultancy/Advisor: MJH BioScience, AriVan Research, Janssen, ADC Therapeutics, Gilead, GSK, Caribou, Roche, Autolus. Dr. Elsawy reports honoraria and Consultancy from Kite/Gilead, BMS, Novartis. Dr. Ganguly reports Ad Board: Pfizer, BMS, Sanofi Genzyme. Dr. Locke Frederick L. Locke reports scientific advisory roles/consulting fees from A2, Allogene, Amgen, Bluebird Bio, BMS, Calibr, Caribou, Cowen, EcoR1, Gerson Lehrman Group (GLG), Iovance, Kite Pharma, Janssen, Legend Biotech, Novartis, Sana, Umoja, and Pfizer. He serves on the data and safety monitoring board for the NCI Safety Oversight CAR-T-cell Therapies Committee. He has research contracts or grants to his institution for service from Kite Pharma, Allogene, CERo Therapeutics, Novartis, bluebird bio, 2seventy bio, BMS, and the National Cancer Institute (R01CA244328 MPI: Locke; P30CA076292 PI: Cleveland), as well as support from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (Scholar in Clinical Research PI: Locke). He holds several patents in the field of cellular immunotherapy. He has education or editorial activities with Aptitude Health, ASH, BioPharma Communications CARE Education, Clinical Care Options Oncology, Imedex, and the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer. Dr. Ramakrishnan Geethakumari reports consultancy services/served on advisory boards of Kite Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), ADC Therapeutics, Cellectar Biosciences, Ono Pharma, Ipsen Biopharma, and Regeneron Pharma. Dr. Greenbaum reports honoraria: Novartis; advisory board: Gilead. Dr. Hashmi reports advisory board: Janssen; honoraria: Amgen, Karyopharm. Dr. Hill reports advisory board–March Biosciences; Kite/Gilead–Speaker’s Bureau. Dr. Jain reports institutional research support from CTI Biopharma, Kartos Therapeutics, Incyte, Bristol Myers Squibb, Tscan; Advisory board participation with Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte, AbbVie, CTI, Kite, Cogent Biosciences, Blueprint Medicine, Telios Pharma, Protagonist Therapeutics, Galapagos, Tscan Therapeutics, Karyopharm, MorphoSys, In8Bio. Dr. Kittai reports research funding from AstraZeneca and BeiGene, has performed speaking engagements for AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and Eli-Lilly, and has participated in advisory boards for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and BMS. Dr. McGuirk reports consulting for the following: Kite, Novartis, BMS, AlloVir, Nektar, Sana, CRISPR Therapeutics. Dr. Mussetti reports honoraria for lectures: Takeda, BMS, Gilead, Sanofi; honoraria for advisory board activities: Merck, Jazz Pharma; Participation in clinical trials (PI): Atara, Takeda; research funding: Gilead. Dr. Mirza reports BMS, consultant, speakers bureau. Dr. Pasquini report research support from Novartis, Kite Pharma, a Gilead Company, BMS, Janssen. Consultant and honoraria: Novartis, BMS and Kite Pharma. Dr. Perales reports receiving honoraria from Adicet, Allogene, AlloVir, Caribou Biosciences, Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Equilium, ExeVir, ImmPACT Bio, Incyte, Karyopharm, Kite/Gilead, Merck, Miltenyi Biotec, MorphoSys, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis, Omeros, OrcaBio, Sanofi, Syncopation, VectivBio AG, and Vor Biopharma. He serves on DSMBs for Cidara Therapeutics and Sellas Life Sciences, and the scientific advisory board of NexImmune. He has ownership interests in NexImmune, Omeros, and OrcaBio. He has received institutional research support for clinical trials from Allogene, Incyte, Kite/Gilead, Miltenyi Biotec, Nektar Therapeutics, and Novartis. Dr. Shpall reports Scientific Advising: Axio Research, Zelluna Immunotherapy, FibroBiologics, and Adaptimmune Limited; License Agreement: Affimed, Takeda, and RegeNexus; Board of Directors/Management: NMDP. Mohamed Sorror reports consulting and receiving honoraria from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and research funding from MGH and BlueNote. Dr. Turtle reports research funding: Juno Therapeutics/BMS, Nektar Therapeutics, 10X Genomics; Scientific Advisory Boards: Caribou Biosciences, T-CURX, Myeloid Therapeutics, Arsenal Bio, Cargo Therapeutics, Celgene/BMS Cell Therapy, Differentia Bio, eGlint, Advesya; DSMB member: Kyverna; Ad hoc advisory roles/consulting (last 12 months): Prescient Therapeutics, Century Therapeutics, IGM Biosciences, AbbVie, Boxer Capital, Novartis, Merck; Stock options: Eureka Therapeutics, Caribou Biosciences, Myeloid Therapeutics, Arsenal Bio, Cargo Therapeutics, eGlint; Speaker engagement (last 12 months): Pfizer, Novartis; Patents: CJT is an inventor on patents related to CAR-T cell therapy. All other co-authors report no conflict of interest.

DATA SHARING

Data utilized in CIBMTR studies are accessible online: https://cibmtr.org/CIBMTR/Resources/Publicly-Available-Datasets#.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jain T, Bar M, Kansagra AJ, et al. Use of chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in clinical practice for relapsed/refractory aggressive B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: an expert panel opinion from the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(12):2305–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris EC, Neelapu SS, Giavridis T, Sadelain M. Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(2):85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, et al. ASTCT consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity associated with immune effector cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(4):625–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nastoupil LJ, Jain MD, Feng L, et al. Standard-of-care axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma: results from the US lymphoma CAR T consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(27):3119–3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iacoboni G, Villacampa G, Martinez-Cibrian N, et al. Real-world evidence of tisagenlecleucel for the treatment of relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Med. 2021;10(10):3214–3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernani R, Benzaquén A, Solano C. Toxicities following CAR-T therapy for hematological malignancies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;111:102479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennisi M, Sanchez-Escamilla M, Flynn JR, et al. Modified EASIX predicts severe cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity after chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood Adv. 2021;5(17):3397–3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay KA, Hanafi L-A, Li D, et al. Kinetics and biomarkers of severe cytokine release syndrome after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor–modified T-cell therapy. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2017;130(21):2295–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastos-Oreiro M, Gutierrez A, Reguera JL, et al. Best treatment option for patients with refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma in the CAR-T cell era: real-world evidence from GELTAMO/GETH Spanish groups. Front Immunol. 2022;13:855730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teachey DT, Lacey SF, Shaw PA, et al. Identification of predictive biomarkers for cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(6):664–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant SJ, Grimshaw AA, Silberstein J, et al. Clinical presentation, risk factors, and outcomes of immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome following chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy: a systematic review. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(6):294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oluwole OO, Forcade E, Munõz J, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with large B-cell lymphoma treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel and prophylactic corticosteroids. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2024;59(3):366–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Deng B, Yin Z, et al. Corticosteroids do not influence the efficacy and kinetics of CAR-T cells for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10 (2):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke FL, Neelapu SS, Bartlett NL, et al. Preliminary results of prophylactic tocilizumab after axicabtagene-ciloleucel (axi-cel; KTE-C19) treatment for patients with refractory, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Blood. 2017;130:1547. [Google Scholar]

- 15.CIBMTR. 2023 annual report; 2024. Available from; 2024. https://cibmtr.org/Files/Administrative-Reports/Annual-Reports/2023-Annual-Report.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2024.

- 16.CIBMTR. Data collection forms: CIBMTR; 2023. Available from; 2023. https://www.cibmtr.org/DataManagement/DataCollectionForms/Pages/index.aspx. Accessed October 31, 2024.

- 17.CIBMTR. Protocols and consent forms: CIBMTR; 2022. Available from; 2022. https://www.cibmtr.org/DataManagement/ProtocolConsent/Pages/index.aspx. Accessed October 31, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 18.CIBMTR. Protocol for a research database for hematopoietic cell transplantation, other cellular therapies and marrow toxic injuries, version 9.1 2022. Available from: https://cibmtr.org/Files/Protocols-and-Consent-Forms/Research-Database/Protocol.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2024.

- 19.CIBMTR. Protocol for a research sample repository for hematopoietic cell transplantation, other cellular therapies and marrow toxic injuries: CIBMTR; 2021. [Version 13.0]. Available from: https://cibmtr.org/Files/Protocols-and-Consent-Forms/Research-Sample-Repository/Protocol.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2024.

- 20.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2531–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pennisi M, Jain T, Santomasso BD, et al. Comparing CAR T-cell toxicity grading systems: application of the ASTCT grading system and implications for management. Blood Adv. 2020;4(4):676–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riedell PA, Hwang W-T, Nastoupil LJ, et al. Patterns of use, outcomes, and resource utilization among recipients of commercial axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel for relapsed/refractory aggressive B cell lymphomas. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(10):669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JH, Nath K, Devlin SM, et al. CD19 CAR T-cell therapy and prophylactic anakinra in relapsed or refractory lymphoma: phase 2 trial interim results. Nat Med. 2023;29(7):1710–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreri CJ, Bhutani M. Mechanisms and management of CAR T toxicity. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1396490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strati P, Jallouk A, Deng Q, et al. A phase 1 study of prophylactic anakinra to mitigate ICANS in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023;7(21):6785–6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frigault MJ, Maziarz RT, Park JH, et al. Itacitinib for the prevention of immune effector cell therapy-associated cytokine release syndrome: results from the phase 2 Incb 39110–211 placebo-controlled randomized cohort. Blood. 2023;142:356. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bachy E, Le Gouill S, Di Blasi R, et al. A real-world comparison of tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T cells in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 2022;28(10):2145–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gagelmann N, Bishop M, Ayuk F, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel versus tisagenlecleucel for relapsed or refractory large B cell lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplant Cell Ther. 2024;30(6):584.e1–584.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwon M, Iacoboni G, Reguera JL, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel compared to tisagenlecleucel for the treatment of aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2023;108(1):110–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stella F, Chiappella A, Casadei B, et al. A multicenter real-life prospective study of axicabtagene ciloleucel versus tisagenlecleucel toxicity and outcomes in large B-cell lymphomas. Blood Cancer Discov. 2024;5(5):318–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wudhikarn K, Tomas AA, Flynn JR, et al. Low toxicity and excellent outcomes in patients with DLBCL without residual lymphoma at the time of CD19 CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv. 2023;7(13):3192–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dean EA, Mhaskar RS, Lu H, et al. High metabolic tumor volume is associated with decreased efficacy of axicabtagene ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4(14):3268–3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Locke FL, Rossi JM, Neelapu SS, et al. Tumor burden, inflammation, and product attributes determine outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4(19):4898–4911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roddie C, Neill L, Osborne W, et al. Effective bridging therapy can improve CD19 CAR-T outcomes while maintaining safety in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023;7(12):2872–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keijzer K, de Boer JW, van Doesum JA, et al. Reducing and controlling metabolic active tumor volume prior to CAR T-cell infusion can improve survival outcomes in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey SR, Vatsa S, Larson RC, et al. Blockade or deletion of IFNγ reduces macrophage activation without compromising CAR T-cell function in hematologic malignancies. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022;3(2):136–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gust J, Hay KA, Hanafi L-A, et al. Endothelial activation and blood–brain barrier disruption in neurotoxicity after adoptive immunotherapy with CD19 CAR-T cells. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(12):1404–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data utilized in CIBMTR studies are accessible online: https://cibmtr.org/CIBMTR/Resources/Publicly-Available-Datasets#.