Abstract

Background

Drugs & used in anticancer chemotherapy have severe effects upon the cellular transcription and replication machinery. From in vitro studies it has become clear that these drugs can affect specific genes, as well as have an effect upon the total transcriptome.

Methods

Total mRNA from two skin lesions from a single AIDS-KS patient was analyzed with the SAGE (Serial Analysis of Gene Expression) technique to assess changes in the transcriptome induced by chemotherapy. SAGE libraries were constructed from material obtained 24 (KS-24) and 48 (KS-48) hrs after combination therapy with bleomycin, doxorubicin and vincristine. KS-24 and KS-48 were compared to SAGE libraries of untreated AIDS-KS, and to libraries generated from normal skin and from isolated CD4+ T-cells, using the programs USAGE and HTM. SAGE libraries were also compared with the SAGEmap database.

Results

In order to assess the primary response of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma (AIDS-KS) to chemotherapy in vivo, we analyzed the transcriptome of AIDS-KS skin lesions from a HIV-1 seropositive patient at two time points after therapy. The mRNA profile was found to have changed dramatically within 24 hours after drug treatment. There was an almost complete absence of transcripts highly expressed in AIDS-KS, probably due to a transcription block. Analysis of KS-24 suggested that mRNA pool used in its construction originated from poly(A) binding protein (PABP) mRNP complexes, which are probably located in nuclear structures known as interchromatin granule clusters (IGCs). IGCs are known to fuse after transcription inhibition, probably affecting poly(A)+RNA distribution.

Forty-eight hours after chemotherapy, mRNA isolated from the lesion was largely derived from infiltrating lymphocytes, confirming the transcriptional block in the AIDS-KS tissue.

Conclusions

These in vivo findings indicate that the effect of anti-cancer drugs is likely to be more global than up- or downregulation of specific genes, at least in this single patient with AIDS-KS. The SAGE results obtained 24 hrs after chemotherapy can be most plausibly explained by the isolation of a fraction of more stable poly(A)+RNA.

Background

Existing anti-cancer drugs are generally seen as non-specific anti-mitotic agents, inducing apoptosis in all rapidly dividing cells by interfering with DNA replication and the cell cycle. Distinct combinations of chemotherapeutic agents have been found empirically to be beneficial treating different types of cancer. E.g. bleomycin is used to treat squamous cell carcinoma, lymphomas, and testicular tumors, while doxorubicin (Adriamycin™) is used to combat acute lymphoblastic and myeloblastic leukemia, Wilms' tumor, soft tissue and osteogenic sarcomas, neuroblastoma, cancer of the breast, ovaries, lungs, bladder, and thyroid, lymphomas, bronchogenic and gastric carcinoma, and Kaposi's sarcoma. Vinca alkaloids (vinblastine, vincristine and vindesine) are used in the treatment a wide variety of tumors including lymphomas, breast cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, testicular cancer, leukemia and neuroblastoma. To treat AIDS-KS, a cocktail of doxorubicin, bleomycin and vincristine is at present a widely used chemotherapy.

Anti-cancer drugs have been shown to inhibit cell cycle progression by interfering with microtubule formation and DNA replication, and to induce apoptosis probably through DNA damage. In vitro studies have elucidated some aspects of how this is achieved. Micro-array analysis has indicated that anticancer drugs could be clustered according to the specific gene expression pattern they induced in cultured cells, with drugs with a same known mode of action generating a similar change in mRNA levels [1]. Vinca alkaloids are known to interfere with microtubule formation at the protein level, resulting in G2/M phase arrest, inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis [2]. Doxorubicin also induces cell-cycle arrest at the G2/M checkpoint [3] and induces apoptosis, probably by directly intercalating into double-stranded DNA [4], or by forming drug-DNA adducts, which also prevents DNA replication [5]. Doxorubicin can effectively chelate Fe3+, and subsequently cleave DNA through the production of hydroxyl radicals [6-9]. It was also shown that doxorubicin can inhibit RNA polymerase II [10], and the helicase activity of the RNA helicase II/Gu-protein complex, probably by binding to its RNA substrates [11]. However, all these effects were seen in vitro at relatively high concentrations of the drug. At plasma concentrations, the main action of doxorubicin is probably inhibition of topoisomerase II [12], although helicase inhibition could also be achieved with clinically relevant concentrations. Gene expression profiling clustered doxorubicin with the topoisomerase II inhibitors [1]. Bleomycin has been shown to induce G2 block [13], inhibit DNA [14] and RNA synthesis [15], and induce apoptosis [16]. In addition, bleomycin mediates the degradation of DNA [17,18], especially of active chromatin [19], and of all classes of cellular mRNAs [20]. In vitro, bleomycin upregulates alpha 1 (I) collagen, fibronectin and decorin mRNAs [21] and connective tissue growth factor mRNA [22], in line with its capability to induce pulmonary fibrosis as a side-effect.

Analysis of the complete transcriptome (all mRNAs present in a cell) has been shown to be a powerful way of detecting genes specifically expressed, or up/down-regulated under certain conditions. The most widely used methods used for large-scale gene expression analysis today are micro-arrays and SAGE [23]. One important difference between these methods is that on micro-arrays internal fragments of a transcript are essential for positive identification, while with SAGE only 3' ends of transcripts are captured, and a transcript is identified by a 14 nucleotide stretch at its 3' end. Both methods have been used already on a large variety of tissues, cells, and cell cultures. Cancer tissue from patients was used in several SAGE studies (see e.g. [24-26]), but the short-term effect of chemotherapy on overall gene expression has not been studied to date.

To examine the effect of chemotherapy on gene expression profiles in vivo, we performed SAGE on two AIDS-KS tissue samples taken from a single patient, 24 and 48 hrs after treatment with a cocktail of doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine. These two SAGE libraries were compared with SAGE libraries derived from tumor tissue from two untreated AIDS-KS patients, a SAGE library generated from normal skin, and with a SAGE library from isolated CD45+CD4+ T-cells.

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), a relatively rare disease, is now encountered more often in HIV-infected homosexual men. Characteristic for KS are proliferating spindle-shaped cells, inflammatory cell infiltration, and profound angiogenesis. Two viruses play a role in AIDS-KS: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8, also known as Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated Herpes Virus, KSHV). Immune suppression by HIV could be a mechanism facilitating HHV8 replication, with the HHV8 genome containing many genes able to deregulate the cell cycle such as chemokines, growth factors, a G-coupled receptor, cyclins and anti-apoptotic genes (for a review see: [27]). HHV8 can infect a variety of cells, including B cells, vascular endothelial cells, keratinocytes, monocytes, and macrophages [28-31]. It also is involved in two other types of cancer: primary effusion lymphoma (a B-cell lymphoma) [32], and multicentric Castleman's disease [33].

Results

SAGE library characteristics

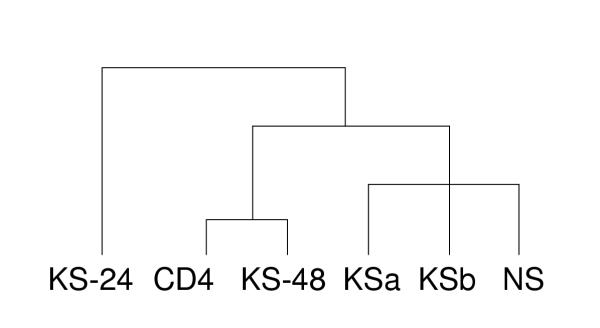

Two SAGE libraries were constructed from treated AIDS-KS tissue. A total of 47,298 tags were sequenced from the SAGE library obtained 24 hrs after the start of the first course of chemotherapy (library KS-24), while 46,671 tags were sequenced from the SAGE library derived from a tumor biopsy taken 48 hrs after treatment (KS-48). Library characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Characteristics for the control libraries from untreated AIDS-KS (KSa and KSb), normal skin (NS), and CD4+ T cells (CD4) are also presented in Table 1. Tag frequencies are very similar for all six SAGE libraries, but the libraries KS-24 and KS-48 generated from the drug-treated material show a higher number of tags that appear only once. Also, the amount of unique tags is higher in KS-24, KS-48 and CD4 compared to KSa, KSb and NS. More tags are differentially expressed tags between library KS-24 and the other three AIDS-KS libraries (Table 2). Statistical correlation analysis was performed using all six SAGE libraries in pair-wise comparisons. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for each comparison (Table 3). The two untreated KS libraries have a correlation coefficient of 0.83, indicating a high level of similarity. Surprisingly, the SAGE library obtained 48 hrs after chemotherapy, KS-48, shows a high correlation coefficient of 0.92 with SAGE library CD4, suggesting that mRNA isolated from this biopsy is mainly derived from infiltrating T-cells. Histological analysis of the paraffin embedded tissue of KS-24 and KS-48 with anti-CD3 antibodies showed at least a two-fold increase of the amount of T-cells in KS-48 compared with KS-24 (result not shown). Library KS-24 has the lowest correlation coefficients observed with both untreated AIDS-KS libraries (0.38 and 0.37, respectively), suggesting that the RNA pool isolated after chemotherapy is significantly different from that in untreated AIDS-KS. Hierarchical clustering performed with the program Cluster using the Average Linkage Clustering option, and all tag counts that appear at least twice in at least one of the SAGE libraries, confirmed that the expression pattern of KS-24 is greatly different from that of the other libraries (Fig. 2). KS-48 clusters with library CD4 in this tree, in line with the high correlation coefficient of the two libraries.

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of tag counts in the four KS and control SAGE libraries

| Librarya |

Tag count >75 |

Tag count = 25 – 75 |

Tag count = 5 – 24 |

Tag count = 2 – 4 |

Tag count = 1 |

Total tagsb | Unique tagsc |

| KS-24 | 45 | 124 | 1055 | 4484 | 15102 | 47298 | 20810 |

| KS-48 | 34 | 134 | 892 | 3926 | 16498 | 46671 | 21484 |

| KSa | 57 | 143 | 1317 | 3518 | 11326 | 49335 | 16361 |

| KSb | 67 | 151 | 1146 | 3444 | 12075 | 48814 | 16883 |

| CD4 | 39 | 135 | 999 | 4539 | 17956 | 51886 | 23668 |

| NS | 41 | 128 | 866 | 2908 | 11373 | 39492 | 15318 |

a Libraries are: KS-24, AIDS-KS tissue 24 hrs after chemotherapy; KS-48, AIDS-KS tissue 48 hrs after chemotherapy; KSa and KSb, AIDS-KS tissue from two untreated patients, CD4, isolated CD4+ T-cells from a single donor; NS, normal skin from three breast reductions. b Tag numbers after elimination of linker-based tags and duplicate ditags. c Number of unique tags identified in each library.

Table 2.

Transcripts differentially expressed between the four KS SAGE a

| KS-24 | KS-48 | KSa | |

| KS-48 | 306 | ||

| KSa | 367 | 234 | |

| KSb | 374 | 250 | 131 |

a Transcripts differentially expressed at a significance level of p < 0.01.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients obtained from variation analysis of the six SAGE libraries

| KS-24 | KS-48 | KSa | KSb | NS | CD4 | |

| KS-24 | 1.00 | |||||

| KS-48 | 0.55 | 1.00 | ||||

| KSa | 0.38 | 0.58 | 1.00 | |||

| KSb | 0.37 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 1.00 | ||

| NS | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 1.00 | |

| CD4 | 0.51 | 0.92 | 0.51 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 1.00 |

Figure 2.

Clustered display of SAGE gene expression data Cluster tree is based upon an average linkage analysis of the six SAGE libraries [56]. Only tags that appear at least twice in at least one of the libraries have been used.

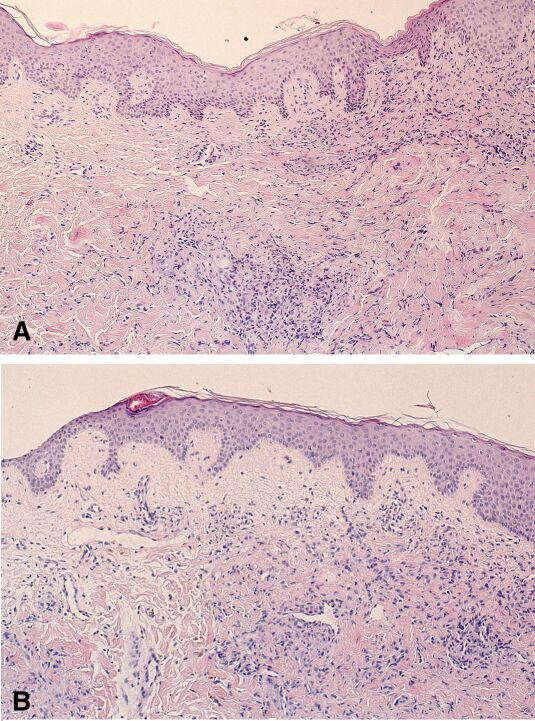

Apoptotic cells could be seen in the H&E stained paraffin sections of both time points (24 hr and 48 hr), whereby apoptosis was most pronounced in the epidermis of the 24 hrs biopsy (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining of the AIDS-KS lesions used for SAGE Two skin biopsies were taken from a single patient, respectively 24 hrs (top panel) and 48 hrs (lower panel) after start of chemotherapy with doxorubicin, bleomycin and vincristine. In both biopsies, endothelial cell proliferations are seen in the dermis consistent with plaque stage Kaposi's sarcoma. The elongated nuclei of these cells show moderate atypia. Within the spindle cell areas, narrow slits containing erythrocytes are visible. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that in both lesions the atypical spindle cells are CD31 and HHV8 positive (not shown). Additionally, in the upper panel, many apoptotic keratinocytes with nuclear dust are found scattered over the basal layer of the epidermis. This histologically visible therapy effect was not conspicuous any more after 48 hours. Both lesions contain sparse inflammatory cell infiltrates.

Highest tag counts in KS-24

The twenty-five highest tags counts found in library KS-24 have been summarized in Table 4. Six out of twenty-five highest tags in KS-24 do not identify single genes, but match over 20 transcripts. One tag matches three genes. Of the highest tags that do identify single genes, two tags identify mitochondrial transcripts, and 9 represent ribosomal protein (RP) mRNA's. RP S29 has the highest tag count of these RP tags. Doxorubicin has been reported to induce RP S29 mRNA [34].

Table 4.

Twenty-five most frequent tags from SAGE library KS-24

| Tag | Count | Percentage | Identification(s) | Unigene cluster |

| CTAAGACTTC | 588 | 1.24 | Mt 16S rRNA | - |

| CCTGTAATCC | 308 | 0.65 | Multiple (>20) | - |

| CTCATAAGGA | 281 | 0.59 | Mt 16S rRNA | - |

| ATAATTCTTT | 276 | 0.58 | RP S29 | Hs 539 |

| CCACTGCACT | 267 | 0.56 | Multiple (>20) | - |

| AAAAAAAAAA | 255 | 0.54 | Multiple (>20) | - |

| GTGAAACCCC | 227 | 0.48 | Multiple (>20) | - |

| TACCATCAAT | 222 | 0.47 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase | Hs 169476 |

| ATTCTCCAGT | 193 | 0.41 | RP L23 | Hs 234518 |

| TGCACGTTTT | 177 | 0.37 | RP L32 | Hs 169793 |

| TTCATACACC | 173 | 0.36 | Mt NADH-dehydrogenase subunit 4L | - |

| CACCTAATTG | 165 | 0.35 | Mt ATP-synthase 6 and 8 | - |

| TAGGTTGTCT | 153 | 0.32 | Tumor protein, translationally controlled 1 | Hs 279860 |

| CCTAGCTGGA | 152 | 0.32 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A (Cyclophilin A) | Hs 182937 |

| GGATTTGGCC | 149 | 0.32 | RP large P2 | Hs 119500 |

| TGTACCTGTA | 146 | 0.31 | Tubulin, alpha, ubiquitous | Hs 278242 |

| GTGAAACCCT | 140 | 0.30 | Multiple (>20) | - |

| TTGGTCCTCT | 140 | 0.30 | RP L41 | Hs 324406 |

| AACTAAAAAA | 130 | 0.28 | RP S27a | Hs 3297 |

| GAGGGAGTTT | 124 | 0.26 | RP L27a | Hs 76064 |

| CTGGGTTAAT | 121 | 0.26 | RP S19 | Hs 298262 |

| TTCAATAAAA | 116 | 0.25 | Multiple (3) | - |

| AAAACATTCT | 115 | 0.24 | Mt 16S rRNA | - |

| TTGGCCAGGC | 107 | 0.23 | Multiple (>20) | - |

| TAATAAAGGT | 106 | 0.23 | RP S8 | Hs 151604 |

Effect of chemotherapy after 24 hrs: disappearance of KS tags

In another study a SAGE gene expression profile of AIDS-KS is reported (Cornelissen et al., manuscript submitted). Here, 64 genes significantly overexpressed in AIDS-KS libraries KSa and KSb were tabulated. Comparing this AIDS-KS signature expression with library KS-24, only 6/64 tags were found to be expressed at approximately the same level, while for 56/64 tags their expression was reduced to very low or zero in KS-24. For the first twenty-one tags, the results are shown in Table 5. Two tags, one with no reliable matches, and the other corresponding to prothymosin-α, were expressed somewhat higher, but not more than twofold, after chemotherapy. Expression of the prothymosin-α gene is cell cycle regulated, and the protein is involved in proliferation checkpoints.

Table 5.

Transcription profile of untreated AIDS-KS compared with KS-24 and normal skin (NS) a

| Tag | Identification | KS-24 (treated) | KS (untreated) | NS |

| GACCGCAGGA | Collagen, type IV, α1 | 0 | 117 | 1 |

| GTGCGCTGAG | MHC, class I C | 1 | 93 | 1 |

| CGTGGGTGGG | Heme oxygenase (decyling) 1 | 0 | 171 | 5 |

| CTCTAAGAAG | Complement component 1q subcomponent α peptide | 0 | 40 | 1 |

| GAGAGTGTCT | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase, collagenase inhibitor (TIMP) | 1 | 31 | 1 |

| GCGGTTGTGG | Lysosomal-associated multispanning membrane protein 5 | 0 | 28 | 1 |

| CGGGGTGGCC | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein | 0 | 28 | 0 |

| GCAAGAAAGT | Hemoglobin β | 0 | 24 | 0 |

| ACCGCCGTGG | Cytochrome b-245, α polypeptide | 0 | 22 | 1 |

| CCGGGTGATG | ATX1 (antioxidant protein1) | 5 | 22 | 1 |

| GCTGCGGTCC | H2A histone family member | 0 | 19 | 1 |

| GTGTTAACCA | Ribosomal protein L15 | 13 | 19 | 1 |

| ACCATTCTGC | Interferon induced transmembrane protein 2 (1-8D) | 0 | 19 | 1 |

| GGCTCCCACT | Heat shock 90 kD protein1, beta | 8 | 18 | 0 |

| CGGGATTCCT | Phospholipid transfer protein | 0 | 18 | 1 |

| GCTGGTGCCT | Thy-1 cell surface antigen | 0 | 17 | 1 |

| TACAGTATGT | Glutamate-ammonia ligase, glutamine synthase | 11 | 17 | 1 |

| GAGCAGCGCC | S100 calcium binding protein A7 (Psoriasin) | 0 | 101 | 8 |

| ACTTTAGATG | Collagen type VI α3 | 0 | 33 | 3 |

| GTGGCCACGG | S100 calcium binding protein A9 (Calgranulin) | 1 | 96 | 8 |

| GCCCCTCCGG | 16,7 Kd protein | 3 | 16 | 1 |

| AGTAGCCGTG | No reliable matches | 13 | 16 | 1 |

| ACAGGGTGAC | Endothelial differentiation-related factor 1 | 3 | 15 | 1 |

| TGGAGAAGAG | Thioredoxin interacting protein | 0 | 15 | 1 |

| TGTCATCACA | Lysyl oxidase-like 2 | 0 | 15 | 1 |

| TCAGACGCAG | Prothymosin α | 91 | 56 | 6 |

a All libraries were normalized to tag number per 50.000

In general, classes of genes whose expression was absent or significantly decreased in KS-24 included cytokines, chemokines, collagens, keratins, S100 calcium-binding proteins, MHC components, and integrins (not shown). Elevated tag counts (> 3-fold increase) include those for seven ribosomal proteins (S25, large P1, L7, S29, L37, S27a, L23), glutaminyl tRNA-synthetase, transcription factors, translation initiation/elongation factors (including cyclin T), poly(A) binding proteins, cyclins (B1, B2, D3), and four tags representing parts of the T-cell receptor (β chain, CD3D antigen delta polypeptide, CD3G antigen gamma peptide, CD3Z antigen zeta polypeptide). No tags were detected for the α-chain of the T-cell receptor. In the CD4 library, tags for the α-chain were found, but not for the β chain, or any other component of the CD3 antigen.

Effect of chemotherapy: decrease of nuclear rRNA but not mitochondrial rRNA tags

For doxorubicin it is known that, probably through topoisomerase II inhibition, the drug has a dramatic negative effect upon 18S rRNA transcription in vitro[35]. Normally, rRNA tags are ignored as artifacts in SAGE libraries as ideally the SAGE procedure should start with only poly(A) mRNA. However, despite the mRNA purification step and the fact that rRNAs do not possess poly(A) tails, all SAGE libraries created to date contain fair amounts of rRNA derived tags. To investigate the effects of chemotherapy in vivo, tags derived from rRNA molecules were counted in the AIDS-KS and control libraries (Table 6). 18S and also 28S rRNA tag counts have dropped significantly 24 hrs after the start of chemotherapy (KS-24), compared with untreated AIDS-KS tissue and normal skin, in line with the in vitro findings. Mitochondrial rRNA tag counts are, however, in the normal range. Interestingly, the two libraries derived from untreated material at autopsy contain very low mitochondrial rRNA tag counts.

Table 6.

Tag counts derived from ribosomal RNAs in the six SAGE libraries a

| rRNA | KS-24 | KS-48 | KSa | KSb | NS | CD4 |

| Mt 12S (3 tags) | 189 | 474 | 69 | 24 | 78 | 879 |

| Mt 16S (4 tags) | 1025 | 573 | 33 | 44 | 164 | 1043 |

| Total mitochondrial | 1378 (2.91 %) | 1047 (2.24%) | 102 (0.21%) | 68 (0.14%) | 242 (0.61%) | 1922 (3.70%) |

| 18S (8 tags) | 50 | 931 | 401 | 883 | 134 | 1626 |

| 28S (8 tags) | 33 | 354 | 134 | 164 | 68 | 461 |

| Total nuclearb | 83 (0.18%) | 1285 (2.75%) | 535 (1.08%) | 1047 (2.15%) | 202 (0.51%) | 2087 (4.02%) |

a Libraries have not been normalized b No NlaIII sites are present in the 5S and the 5.8S rRNA genes

Increase in tags containing poly(A) sequences in KS-24

The SAGE technique detects the 3' ends of mRNAs through their poly(A) tails. As such, transcripts undergoing severe degradation of the poly(A) stretch, e.g. during apoptosis, will not be captured and thus not be detected. Poly(A)-tails represent the only general motif that can be analyzed using SAGE to check for eventual mRNA degradation. To investigate whether tags containing part of the poly(A) tail are differentially detected in library KS-24 versus the other libraries, all tags ending with poly(A)6–10 were counted in the AIDS-KS and control libraries. Manual checking of these tags within their mRNAs, showed that indeed >98% of them represent the start of the poly(A) stretch, and do thus not represent internal tags. From Table 7 it can be seen that tags ending with (A)6–10 are actually higher in KS-24, or lower in the other AIDS-KS libraries. NxAy (where x = 4–0 and y = 6–10) tags increase from 0.06–0.13 % in KSa/KSb/KS-48 to 2.04 % in KS-24, a 15–34 fold increase. Tag A10 is increased around 50× in KS-24 compared with the other AIDS-KS libraries (Table 7). Interestingly, Table 8 showed that at least two poly(A) binding protein mRNAs (PABP1 and -2), whose encoded proteins are involved in stabilization of mRNA, are also expressed at high levels in KS-24. This suggest that the observed increase in poly(A) tags could be due to increased protection of mRNA by PABP's. In normal skin, PABP1, but not PABP2, is expressed at the same level as in KS-24. Overall, these findings suggests that the mRNA pool which generated library KS-24 contained on an average longer poly(A)-tails than the other libraries.

Table 7.

Frequency of tags ending with multiple A-nucleotides in the AIDS-KS and control SAGE libraries a

| Tag |

KS-24 47298 tags |

KS-48 46671 tags |

KSa 49335 tags |

KSb 48814 tags |

NS 39492 tags |

CD4 51886 tags |

| AAAAAAAAAA | 255 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 45 | 15 |

| NAAAAAAAAA | 178 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 38 | 12 |

| NNAAAAAAAA | 184 | 5 | 23 | 23 | 136 | 39 |

| NNNAAAAAAA | 101 | 5 | 11 | 3 | 37 | 23 |

| NNNNAAAAAA | 245 | 10 | 18 | 20 | 32 | 56 |

| Total % | 2.04 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.73 | 0.28 |

a Libraries have not been normalized

Table 8.

Poly(A) binding protein tags in the AIDS-KS and control SAGE libraries a

| Identification | Tag |

KS-24 47298 tags |

KS-48 46671 tags |

KSa 49335 tags |

KSb 48814 tags |

NS 39492 tags |

CD4 51886 tags |

| Poly(A) binding protein, nuclear 1 (PABP2) Hs 117176 |

AATAAAGTTG | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| GTATTCCCCT | 28 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 6 | |

| Poly(A) binding protein, cytoplasmic 1 (PABP1) Hs 172182 |

AAAAGAAACT | 25 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 18 | 3 |

a Libraries have not been normalized

Discussion

SAGE is a widely used technique to analyze the transcriptome of cells and tissues. Here, we have studied mRNA populations expressed in AIDS-KS tissue of a single patient, 24 and 48 hrs after chemotherapy with a cocktail of doxorubicin, bleomycin and vincristine (libraries KS-24 and KS-48, respectively), and compared them with SAGE libraries generated from similar tissue of two untreated patients (libraries KSa and KSb). Resistance to the chemotherapy was not observed, as the patient already improved upon the first treatment, and all KS lesions finally resolved after five courses. All three anti-cancer drugs are able to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in proliferating cells through damage of the DNA. Inhibition of DNA replication and RNA transcription are other common effects. In vitro investigations show that the drugs are capable of up/down regulating specific genes [21,34,36-38].

The tag counts of the four libraries ranged from 46,671 – 49,335 tags. Libraries KS-24 and KS-48 had slightly higher unique tag counts than KSa and KSb (~20,000 versus ~16,500). Tag frequencies were similar between the four libraries, albeit that KS-24 and KS-48 contained more single tags than the other two libraries (~15,500 versus ~11,500). So, from the general characteristics of the SAGE libraries, chemotherapy does not seem to create significant problems when constructing a SAGE library. Comparing relationships based on gene expression profiles, libraries KS-48, KSa, and KSb were more closely related to each other than to KS-24. However, correlation analysis showed that library KS-48 was almost identical to a library generated from CD4 T-cells, suggesting that the RNA extracted from the KS-48 tissue is derived from tumor infiltrating T-cells, possibly because the AIDS-KS cells are still suffering from cell cycle arrest at this time-point. In paclitaxel-treated breast cancer patients, the attraction of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) after treatment, probably resulting from drug-induced apoptosis, was found to be an indicator of favorable outcome [39]. In the patient described in this paper, a good response to chemotherapy and a complete recovery from AIDS-KS was observed, suggesting that the development of TILs after chemotherapy is also a predictor of clinical response in AIDS-KS. Most likely, these infiltrating lymphocytes are CD8+ T-cells, allowing for the slight discrepancy between the KS-48 and CD4 SAGE libraries (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.92).

The significant divergence of library KS-24 suggests a major impact of chemotherapy on the cellular transcriptome, in line with earlier experiments [1]. In summary, the main results from SAGE analysis of anti-cancer drug-treated tissue were: 1. Transcripts found to be highly and specifically expressed in AIDS-KS were lacking or low, 2. Nuclear ribosomal RNA levels have declined, and 3. mRNAs with long(er) poly(A)-tails were abundant. Results 1 and 2 are likely to be due to inhibition of transcription, and subsequent degradation of RNA. Lam et al.[40], analyzing the transcriptional effect of several anti-cancer drugs on micro-arrays, found that transcriptionally inducible genes often have short half-lives of less than 4 hrs. The major classes of unstable transcripts include those encoding cytokines, chemokines, and apoptosis- and cell cycle regulators. Thus, 24 hrs after drug-treatment, resulting in repression of de novo transcription, most unstable transcripts likely have disappeared from the cells. Doxorubicin treatment of cells in vitro results in a complete shut down of transcription, possibly because doxorubicin inhibits the activity of RNA polymerase II [37]. Topoisomerase II inhibition by doxorubicin could explain the severe effects of this drug on RNA polymerase I and -III promoters [35]. Most likely, the transcripts found to be highly expressed in AIDS-KS, which include collagens, keratins, S100 calcium-binding proteins, MHC components, and integrins, have relatively short half-lives, and are thus no longer present in KS-24.

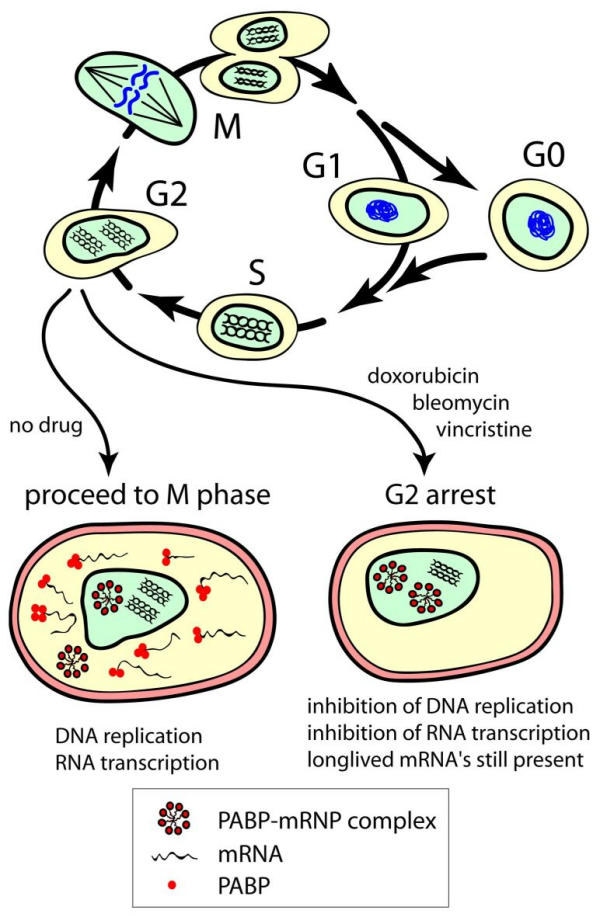

Another characteristic of KS-24 are the relatively longer poly(A)-tails and the increase of nuclear PABP2 tags, suggesting that a "better" protected and probably longer-lived mRNA pool has been isolated. PABP's bind to poly(A)-tails to protect mRNAs from ribonuclease attack and rapid decay (for a review on the regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells, see: [41]). Two classes of nuclear poly(A) RNA with different half-lives, 2.5 hrs and 8–12 hrs, respectively, have been described earlier in growing cell cultures [42]. A stable population of nuclear poly(A)+ RNA can be found in interchromatin granule clusters (IGCs), also known as speckles. IGCs contain components of the pre-mRNA splicing machinery, and are involved in mRNA processing (see: [43]). Inhibition of RNA polymerase II transcription in vitro results in the fusion of these IGCs [44]. At the same time, poly(A)+ RNA levels in the nucleoplasm decreased significantly. Brawerman and Diez [45] noted unusually long poly(A) segments in the nucleus after a transcription block in rodent cells, probably because poly(A) addition continues in the absence of de novo transcription. So, the cell nucleus apparently contains a population of long-lived poly(A)+ RNA in IGCs, which upon transcription inhibition reorganize into larger IGCs. At the same time, additional extension of the poly(A) tails takes place, and nucleoplasmic poly(A)+ RNA is lost. Nuclear PABP2 protein has been detected in isolated IGCs [46]. Recently, mRNA from messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes, mRNPs, has been analyzed on cDNA arrays [47]. Three types of mRNP complexes (HuB, eIF-4E, and PABP) were found to contain mRNA profiles significantly different from each other and from the total RNA pool. An interesting feature of the mRNA subset isolated from PABP-mRNP complexes was the high amount of RP S29 mRNA in these complexes compared with the total RNA profile, in line with the abundance of RP S29 tags seen in KS-24. PABP-mRNP complexes further contained higher levels of mRNAs for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and RP L32, for both of which tag numbers were also increased in KS-24 (ten-fold and two-fold, respectively, result not shown). So, it is likely that the RNA profile of KS-24 is mainly derived from mRNA contained in PABP-mRNP complexes (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of chemotherapy in cycling cells. Drug-induced DNA damage, results in G2/M checkpoint-arrest and inhibition of RNA transcription. Twenty-four hours after drug treatment only long-lived mRNA's can be isolated, most likely residing in PABP-mRNP complexes.

Another factor likely to distort the mRNA profile after anti-cancer drug-treatment is the ability of chemotherapeutic agents to inhibit cell cycle progression at a certain point. Analyzing the pattern of gene expression during the cell cycle, oscillation of many mRNAs, including genes known to be involved in cell cycle control, was detected [48]. Earlier reports indicated that the three drugs administered to the patient analyzed here all block cells in late G2, just before start of mitosis. Genes expressed at high levels during G2 in the mouse include cyclin B1, and cdc20 (see also [48]), both of which are elevated in KS-24. In line with this, doxorubicin was found to induce cyclin B1 accumulation in cell cultures [49,50]. Cyclin B1 tags are approximately 5-fold induced in KS-24, tags for cdc20 are absent from all libraries except KS-24, which contains 9 tags /50.000. Increased tags for cyclin B2 (4 tags/50.000 in KS-24, none in the other libraries) also point at inhibition at the G2/M boundary in KS-24. Cyclin D3 tags are elevated in KS-24, but cyclin D3 is not cell cycle regulated and its concentration depends upon the growth rate of the cell. During mitosis there is no significant transcription, resulting in a reduction of poly(A)+ RNA and protein synthesis. It is possible that a large number of mRNAs, including those for the PABP's themselves, are before this stage assembled into complexes, to have them ready for translation at the next phase of the cell cycle. If this is true, the observation of an increase in PABP-bound mRNAs in KS-24 could be directly associated to cancer cells being blocked at the G2/M transition. Poly(A) polymerase (PAP) activity is cell cycle regulated, with enzyme activity being low during mitosis [51].

Analysis of gene expression patterns in vivo after anticancer drug treatment in AIDS-KS suggest that the RNA profile is dramatically influenced by the extraction of subsets of mRNA present in mRNP complexes, as well as by a block in transcription, resulting in differences in stability of individual mRNAs becoming highly important. Cell cycle effects are also likely to be important, as the expression of many genes fluctuates with the phase of the cell cycle. The findings reported here oppose the common idea that the main effect of chemotherapy is found in the specific up- or downregulation of gene expression, whereby the genes found to be affected play an important role in the reaction of the cell upon the anti-cancer drug. This could be an effect at low concentrations, but is unlikely to be the main effect of chemotherapeutic agents at effective plasma levels.

Conclusions

Analysis of gene expression patterns in vivo after anticancer drug treatment in AIDS-KS suggest that the RNA profile is dramatically influenced by the extraction of subsets of mRNA present in mRNP complexes, as well as by a block in transcription, resulting in differences in stability of individual mRNAs becoming highly important. Cell cycle effects are also likely to be important, as the expression of many genes fluctuates with the phase of the cell cycle. The findings reported here, although be it in a single patient, oppose the common idea that the main effect of chemotherapy is found in the specific up- or downregulation of gene expression, whereby the genes found to be affected play an important role in the reaction of the cell upon the anti-cancer drug. This could be a possible effect at low concentrations, but is unlikely to be the main effect of chemotherapeutic agents at effective plasma levels.

Competing interests

None declared.

Methods

Patient

A 31-year old man was demonstrated to be HIV-1 seropositive in February 1997. The initial CD4 cell count was 25 × 106/ l. The patient presented within two months a mucocutaneous Herpes simplex infection and an extrapulmonary Cryptococcosis for which specific medication was given. The HIV-1 RNA load at presentation was 15,000 copies/ml and increased to 33,000 copies/ml in three months. Then antiretroviral therapy was started with zidovudine, lamivudine and indinavir. After 4 weeks of treatment his plasma HIV-1 copy number had declined to below the assay detection limit (1000 copies/ml). Six months later the patient presented with gradual appearance of an increasing number of violaceous skin lesions in the perianal region and on the face that clinically resembled KS. The diagnosis was confirmed by histological examination of one of the lesions. A serum sample taken earlier was found to be positive for HHV8 antibody. In view of the rapidly progressive and extensive nature of the disease, systemic chemotherapy with bleomycin (15 mg), vincristine (2 mg) and doxorubicin (10 mg/m2) was started. At this time KS had progressed to about 150 cutaneous lesions. Antiretroviral therapy was continued unchanged. The interval between the courses of chemotherapy was three weeks, and five courses were given. Following the first course of chemotherapy no new KS lesions appeared during the first month and about two thirds of the existing lesions had disappeared. Complete remission was gradually reached after one year. During chemotherapy several biopsies were taken. The first biopsy was obtained 24 hours after the start of the chemotherapy (named KS-24) and the second biopsy was taken after 48 hours (named KS-48). Two biopsies were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after neurosurgical removal and stored at -80°C. Another biopsy taken from the same lesion was used for histological analysis. Diagnosis of AIDS-KS was confirmed histopathologically (Fig. 1a, 1b). About 30–40% of the biopsies consisted of tumor specific spindle cells.

SAGE libraries KSa and KSb were made from frozen material taken at autopsy from two untreated AIDS-KS patients, both of which died in 1986 (Cornelissen et al., manuscript submitted). Additionally, a control SAGE libraries of 39,492 tags was generated from the pooled normal skin samples of three patients undergoing reduction mammoplasty (library NS), and another control library of 51,886 tags was made from isolated CD45+CD4+ T-cells from a healthy blood donor (library CD4). Control libraries KSa, KSb and NS have been described elsewhere (Cornelissen et al., manuscript submitted).

SAGE library construction

CD4+ T-cells were depleted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a single healthy donor by the use of CD4-coated immunomagnetic beads (miniMACS, CLB, The Netherlands). Total RNA was isolated from the two AIDS-KS biopsies and from 1.9 × 107 CD4+ T-cells using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, San Diego CA, USA). Poly(A)+ RNA was further isolated using the Micro-FastTrack 2.0 messenger RNA (mRNA) purification kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. SAGE was performed as described previously [23,52]. In short: synthesis of cDNA was performed using Superscript II RNAse H-reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, San Diego CA, USA) and a primer biotin-5'-T18-3'. The cDNA was then cleaved with NlaIII, and the 3' restriction fragments were isolated with magnetic streptavidin-coated beads (Dynabeads M280 from Dynal, Oslo, Norway). Oligonucleotides containing BsmF1 recognition sites were ligated to the fragments bound to the beads, and tags were released from the beads by BsmF1 digestion. Tags were ligated to create ditags, and amplified by 26–28 PCR cycles. NlaIII digested, amplified ditags were subsequently concatenated and cloned using the Zero Background cloning kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad CA, USA). Colonies were screened by PCR using M13 reverse or (-) 21M13 primers, and inserts were sequenced with the Bigdye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (ABI, Foster City CA, USA) and analyzed with an ABI 377 automated sequencer (ABI, Foster City CA, USA), following the manufacturer's protocols.

Analysis of SAGE libraries

Primary analysis of the SAGE libraries was performed with the program USAGE version2 [53]. This program is able to do initial analyses on raw sequence data, e.g. ditag and tag extraction, tag counting, and tag identification. Tags are identified with the tag-to-gene mapping of the SAGEmap database and a tag-to-gene mapping database established as part of the Human Transcriptome Map [54]. In this latter identification, the SAGEmap database from NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SAGE has been corrected for common errors, mostly due to sequencing errors in publicly available sequences.

Secondly, the USAGE program was used to compare SAGE libraries, and to do statistical analyses on tag count differences. For this, USAGE implements the method proposed by Kal et al[55].

The programs Cluster and TreeView ([56], http://www.microarrays.org/software.html were used to perform hierarchical clustering on the SAGE data, and to visualize the resulting tree, respectively.

Authors' contributions

ACvdK carried out the bioinformatical analysis and drafted the manuscript, RvdB constructed the SAGE libraries, FZ, JTD, JM sequenced the SAGE libraries, CJMvN performed the histological analysis, JG, MC conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. T. Halaby for access to the patient samples, W.van Est for generating the computer version of figure 3, and Dr. B. Berkhout for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Antoinette C van der Kuyl, Email: a.c.vanderkuyl@amc.uva.nl.

Remco van den Burg, Email: r.vandenburg@amc.uva.nl.

Fokla Zorgdrager, Email: f.zorgdrager@amc.uva.nl.

John T Dekker, Email: j.t.dekker@primagen.com.

Jolanda Maas, Email: j.maas@primagen.com.

Carel JM van Noesel, Email: c.j.vannoesel@amc.uva.nl.

Jaap Goudsmit, Email: j.goudsmit@crucell.com.

Marion Cornelissen, Email: m.i.cornelissen@amc.uva.nl.

References

- Scherf U, Ross DT, Waltham M, Smith LH, Lee JK, Tanabe L, Kohn KW, Reinhold WC, Myers TG, Andrews DT, et al. A gene expression database for the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Nat Genet. 2000;24:236–244. doi: 10.1038/73439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MA, Thrower D, Wilson L. Mechanism of inhibition of cell proliferation by Vinca alkaloids. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2212–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlogie B, Drewinko B, Johnston DA, Freireich EJ. The effect of adriamycin on the cell cycle traverse of a human lymphoid cell line. Cancer Res. 1976;36:1975–1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimnaugh EG, Trush MA, Bhatnagar M, Gram TE. Enhancement of reactive oxygen-dependent mitochondrial membrane lipid peroxidation by the anticancer drug adriamycin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;34:847–856. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90766-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinane C, Cutts SM, Panousis C, Phillips DR. Interstrand cross-linking by adriamycin in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA of MCF-7 cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1019–1025. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot H, Gianni L, Myers C. Oxidative destruction of DNA by the adriamycin-iron complex. Biochemistry. 1984;23:928–936. doi: 10.1021/bi00300a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muindi J, Sinha BK, Gianni L, Myers C. Thiol-dependent DNA damage produced by anthracycline-iron complexes. The structure-activity relationships and molecular mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;27:356–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muindi JR, Sinha BK, Gianni L, Myers CE. Hydroxyl radical production and DNA damage induced by anthracycline-iron complex. FEBS Lett. 1984;172:226–230. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C, Gianni L, Zweier J, Muindi J, Sinha BK, Eliot H. Role of iron in adriamycin biochemistry. Fed Proc. 1986;45:2792–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglia CA, Wilson RG. Two types of adriamycin inhibition of a homologous RNA synthesizing system from L1210 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 1981;33:319–327. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(81)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu K, Henning D, Iwakuma T, Valdez BC, Busch H. Adriamycin inhibits human RH II/Gu RNA helicase activity by binding to its substrate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266:361–365. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz DA. A critical evaluation of the mechanisms of action proposed for the antitumor effects of the anthracycline antibiotics adriamycin and daunorubicin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:727–741. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlogie B, Drewinko B, Schumann J, Freireich EJ. Pulse cytophotometric analysis of cell cycle perturbation with bleomycin in vitro. Cancer Res. 1976;36:1182–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda A. Gene expression in ataxia telangiectasia cells as perturbed by bleomycin treatment. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1992;18:113–122. doi: 10.1007/BF01233158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MT, Auger LT, Saunders GF, Haidle CW. Effect of bleomycin on the synthesis and function of RNA. Cancer Res. 1977;37:1345–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernole P, Tedeschi B, Caporossi D, Maccarrone M, Melino G, Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M. Induction of apoptosis by bleomycin in resting and cycling human lymphocytes. Mutagenesis. 1998;13:209–215. doi: 10.1093/mutage/13.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal ZM, Kohn KW, Ewig RA, Fornace AJ., Jr Single-strand scission and repair of DNA in mammalian cells by bleomycin. Cancer Res. 1976;36:3834–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea AD, Haseltine WA. Sequence specific cleavage of DNA by the antitumor antibiotics neocarzinostatin and bleomycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:3608–3612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MT. Preferential damage of active chromatin by bleomycin. Cancer Res. 1981;41:2439–2443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SM. Bleomycin: new perspectives on the mechanism of action. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:158–168. doi: 10.1021/np990549f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Eckes B, Krieg T. Bleomycin increases steady-state levels of type I collagen, fibronectin and decorin mRNAs in human skin fibroblasts. Arch Dermatol Res. 2000;292:556–561. doi: 10.1007/s004030000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasky JA, Ortiz LA, Tonthat B, Hoyle GW, Corti M, Athas G, Lungarella G, Brody A, Friedman M. Connective tissue growth factor mRNA expression is upregulated in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L365–L371. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.2.L365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velculescu VE, Zhang L, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Serial analysis of gene expression. Science. 1995;270:484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough CD, Sherman-Baust CA, Pizer ES, Montz FJ, Im DD, Rosenshein NB, Cho KR, Riggins GJ, Morin PJ. Large-scale serial analysis of gene expression reveals genes differentially expressed in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6281–6287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waghray A, Schober M, Feroze F, Yao F, Virgin J, Chen YQ. Identification of differentially expressed genes by serial analysis of gene expression in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4283–4286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu B, Jones J, Hollingsworth MA, Hruban RH, Kern SE. Invasion-specific genes in malignancy: serial analysis of gene expression comparisons of primary and passaged cancers. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1833–1838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PS, Chang Y. Antiviral activity of tumor-suppressor pathways: Clues from molecular piracy by KSHV. Trends in Genetics. 1998;14:144–150. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasig C, Zietz C, Haar B, Neipel F, Esser S, Brockmeyer NH, Tschachler E, Colombini S, Ensoli B, Sturzl M. Monocytes in Kaposi's sarcoma lesions are productively infected by human herpesvirus 8. Journal of Virology. 1997;71:7963–7968. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7963-7968.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerimele F, Curreli F, Ely S, Friedman-Kien AE, Cesarman E, Flore O. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus can productively infect primary human keratinocytes and alter their growth properties. J Virol. 2001;75:2435–2443. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2435-2443.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses AV, Fish KN, Ruhl R, Smith PP, Strussenberg JG, Zhu L, Chandran B, Nelson JA. Long-term infection and transformation of dermal microvascular endothelial cells by human herpesvirus 8. J Virol. 1999;73:6892–6902. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6892-6902.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Arvanitakis L, Rafii S, Moore MA, Posnett DN, Knowles DM, Asch AS. Human herpesvirus-8/Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a new transmissible virus that infects B cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2385–2390. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P, D'Agay M-F, Clauvel J-P, Raphael M, Degos L, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna N, Reddy VG, Tuteja N, Singh N. Differential gene expression in apoptosis: identification of ribosomal protein S29 as an apoptotic inducer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:476–486. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins I, Weber A, Levens D. Transcriptional consequences of topoisomerase inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8437–8451. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8437-8451.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski N, Allard JD, Pittet JF, Zuo F, Griffiths MJ, Morris D, Huang X, Sheppard D, Heller RA. Global analysis of gene expression in pulmonary fibrosis reveals distinct programs regulating lung inflammation and fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1778–1783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh K, Ramanna M, Ravatn R, Elkahloun AG, Bittner ML, Meltzer PS, Trent JM, Dalton WS, Chin KV. Monitoring the expression profiles of doxorubicin-induced and doxorubicin-resistant cancer cells by cDNA microarray. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4161–4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan S, Yamori T. Repression of cyclin B1 expression after treatment with adriamycin, but not cisplatin in human lung cancer A549 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:861–867. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demaria S, Volm MD, Shapiro RL, Yee HT, Oratz R, Formenti SC, Muggia F, Symmans WF. Development of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer after neoadjuvant paclitaxel chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3025–3030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam LT, Pickeral OK, Peng AC, Rosenwald A, Hurt EM, Giltnane JM, Averett LM, Zhao H, Davis RE, Sathyamoorthy M, et al. Genomic-scale measurement of mRNA turnover and the mechanisms of action of the anti-cancer drug flavopiridol. Genome Biol. 2001;2:RESEARCH0041. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-10-research0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhaniyogi J, Brewer G. Regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Gene. 2001;265:11–23. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00350-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson S, Johnson LF. Evidence for highly stable nuclear poly(A) in cultured mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;517:287–295. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(78)90195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector DL. Macromolecular domains within the cell nucleus. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:265–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.9.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Spector DL. The perinucleolar compartment and transcription. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:35–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawerman G, Diez J. Metabolism of the polyadenylate sequence of nuclear RNA and messenger RNA in mammalian cells. Cell. 1975;5:271–280. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz PJ, Patterson SD, Neuwald AF, Spahr CS, Spector DL. Purification and biochemical characterization of interchromatin granule clusters. EMBO J. 1999;18:4308–4320. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum SA, Carson CC, Lager PJ, Keene JD. Identifying mRNA subsets in messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes by using cDNA arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14085–14090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida S, Huang E, Zuzan H, Spang R, Leone G, West M, Nevins JR. Role for E2F in control of both DNA replication and mitotic functions as revealed from DNA microarray analysis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4684–4699. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4684-4699.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling YH, el Naggar AK, Priebe W, Perez-Soler R. Cell cycle-dependent cytotoxicity, G2/M phase arrest, and disruption of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 activity induced by doxorubicin in synchronized P388 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:832–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aytac U, Claret FX, Ho L, Sato K, Ohnuma K, Mills GB, Cabanillas F, Morimoto C, Dang NH. Expression of CD26 and its associated dipeptidyl peptidase IV enzyme activity enhances sensitivity to doxorubicin-induced cell cycle arrest at the G(2)/M checkpoint. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7204–7210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan DF, Murthy KG, Prives C, Manley JL. Cell-cycle related regulation of poly(A) polymerase by phosphorylation. Nature. 1996;384:282–285. doi: 10.1038/384282a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhou W, Velculescu VE, Kern SE, Hruban RH, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Gene expression profiles in normal and cancer cells. Science. 1997;276:1268–1272. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen AH, van Schaik BD, Pauws E, Michiels EM, Ruijter JM, Caron HN, Versteeg R, Heisterkamp SH, Leunissen JA, Baas F, et al. USAGE: a web-based approach towards the analysis of SAGE data. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:899–905. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron H, van Schaik B, van der Mee M, Baas F, Riggins G, van Sluis P, Hermus MC, van Asperen R, Boon K, Voute PA, et al. The human transcriptome map: clustering of highly expressed genes in chromosomal domains. Science. 2001;291:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1056794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kal AJ, van Zonneveld AJ, Benes V, van den Berg M, Koerkamp MG, Albermann K, Strack N, Ruijter JM, Richter A, Dujon B, et al. Dynamics of gene expression revealed by comparison of serial analysis of gene expression transcript profiles from yeast grown on two different carbon sources. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1859–1872. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.6.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci S U A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]