Abstract

Reverse genetics techniques to rescue influenza viruses have thus far been based on the use of a human polymerase I (PolI) promoter to direct the synthesis of the eight viral RNAs. They can only be used on cells from primate origin due to the species specificity of the PolI promoter. Here we report the cloning of the chicken PolI promoter sequence and the generation of recombinant influenza virus upon transfection of bidirectional PolI/PolII plasmids in avian cells. Potential contributions of this new reverse genetics system in the fields of influenza virus research and influenza vaccine production are discussed.

The genome of influenza A viruses consists of eight molecules of single-stranded RNA of negative polarity. The viral RNAs (vRNAs) are associated with the nucleoprotein (NP) and with the three subunits of the polymerase complex (PB1, PB2, and PA) to form ribonucleoproteins (RNPs). Because the minimal replication unit is formed by the RNPs, the generation of virus from cloned cDNAs requires all eight vRNAs, as well as the four viral proteins PB1, PB2, PA, and NP. This technical challenge was overcome when all eight segments of A/WSN/33 virus were cloned under the control of the human RNA polymerase I (RNApolI) promoter (9, 19). The RNApolI enzyme, which ensures transcription of rRNAs, can direct the synthesis of influenza vRNAs because it initiates and terminates transcription precisely at defined promoter and terminator sequences. The viral proteins essential for transcription and replication were initially provided by four expression constructs that were cotransfected into 293T or Vero cells together with the eight RNApolI constructs. Hoffman et al. reported a modification of the reverse genetics system, allowing virus to be generated from eight bidirectional RNApolI/II plasmids instead of 12 plasmids (12).

These reverse genetics systems proved extremely helpful to address a number of questions in the field of influenza virus research (see, for example, references 1, 3, 6-8, and 14). A limitation is that they can only be used on cells of primate origin due to species specificity of the human RNApolI promoter. Here we report the cloning of the chicken RNApolI promoter sequence. Based on that sequence, a plasmid-driven reverse genetics system for the generation of recombinant influenza virus A/PR/8/34 (NIBSC vaccine strain) in avian cells was developed. In the future, this system should allow thorough comparisons of the growth and antigenic properties of recombinant viruses produced in a mammalian versus an avian cell culture system. Ultimately, reverse genetics based on the chicken RNApolI promoter may represent a useful option for the production of recombinant influenza vaccine candidates.

Eukaryotic rRNA genes are organized in clusters of head-to-tail repeats. The rRNA coding sequences are separated by intergenic spacers (IGS), which contain the RNApolI promoter and other regulatory sequence elements. The RNApolI promoter primary sequences are not well conserved between species.

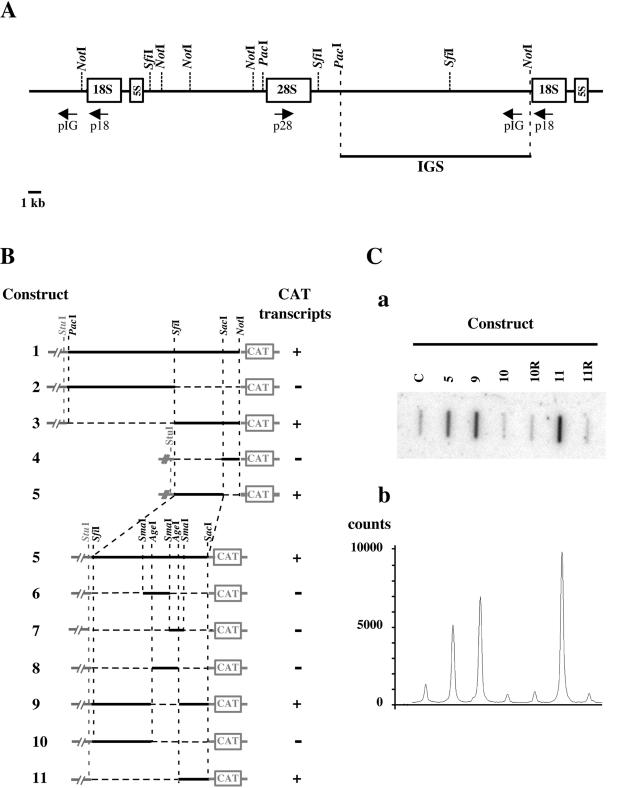

Guillemot et al. kindly provided us with cosmid C13-19 (11), which contains about 40 kb of chicken genomic DNA overlapping the rRNA gene locus and including at least one IGS. After digestion with the enzymes NotI, PacI, and SfiI, cosmid C13-19 was analyzed by Southern blot with oligonucleotide probes complementary to the 18S, 28S, and IGS sequences, respectively. An approximate restriction map of the cosmid was obtained (Fig. 1A). A PacI-NotI restriction fragment of about 16 kb was identified as corresponding to the major part of an IGS and was examined further for the presence of an RNApolI promoter sequence. To this end, we subcloned the 16-kb PacI-NotI DNA fragment into cosmid pTCF (10) and subsequently cloned a 500-bp EaeI fragment derived from the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene at the NotI site, in positive orientation (Fig. 1B, construct 1). The resulting cosmid was transfected into the quail fibrosarcoma-derived QT6 cells. Total RNAs were prepared at 24 h posttransfection and analyzed by slot blotting and hybridization by using a negative-sense CAT-specific 32P-labeled riboprobe. Hybridization signals were consistent with an initiation of transcription upstream of the CAT reporter sequence (data not shown). Iterative analysis of fragments derived from the PacI-NotI fragment by digestion with various restriction enzymes was performed using the same strategy (Fig. 1B). This procedure finally led to the observation of a strong transcription-promoting activity associated with an AgeI-SacI fragment of 1,260 nucleotides (nt) (Fig. 1B and C, construct 11). No signal was obtained when cells were transfected with an empty vector, or with a construct (11R) in which the AgeI-SacI fragment was inserted in the reverse orientation (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Mapping of the chicken RNApolI promoter. (A) Molecular map of the chicken genomic DNA fragment from cosmid C13.19. The restriction map of cosmid C13.19 was established for the indicated enzymes by single and double digestions. Vector DNA is not represented. The rRNA coding regions are indicated by open boxes. Oligonucleotides p18, p28, and pIG (arrows) were used as hybridization probes for Southern blot analysis of digested C13.19 DNA. The PacI-NotI restriction fragment, which was identified as corresponding to the major part of an IGS and was subsequently subcloned into the pTCF cosmid, is shown. (B) Iterative analysis of restriction fragments derived from the 16-kb PacI-NotI fragment of chicken genomic DNA for transcription promoting activity. Sequences derived from chicken genomic DNA are represented by a black solid line, and deleted sequences are represented by a black dotted line. Vector sequences (pTCF in constructs 1 and 2 and pGEM-5-zf+ [Promega] in constructs 3 to 11) are represented by a gray line. The 500-bp sequence derived from the CAT reporter gene is represented as an open box (not on scale). The detection of CAT transcripts by slot blot analysis in QT6 cells transfected with the various constructs is indicated. (C) Detection of CAT transcripts in QT6 cells transfected with the RNApolI promoter reporter constructs. QT6 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs (constructs 5, 9, 10, and 11: see Fig. 1B; constructs 10R and 11R contain the same fragments of genomic DNA as constructs 10 and 11, respectively, but cloned in the reverse orientation; C, empty pGEM-5-zf+ vector as a control). Total RNA was prepared 24 h after transfection and then analyzed by slot blotting and hybridization using a negative sense CAT-specific 32P-labeled riboprobe. The membrane was scanned using a phosphorimager (Amersham-Pharmacia-Biotech), and the resulting image is shown in subpanel a. Quantification was performed by using ImageQuant. software (Amersham-Pharmacia-Biotech). The graph shown in subpanel b represents signal intensity as determined along a line transversal to the slots shown in subpanel a.

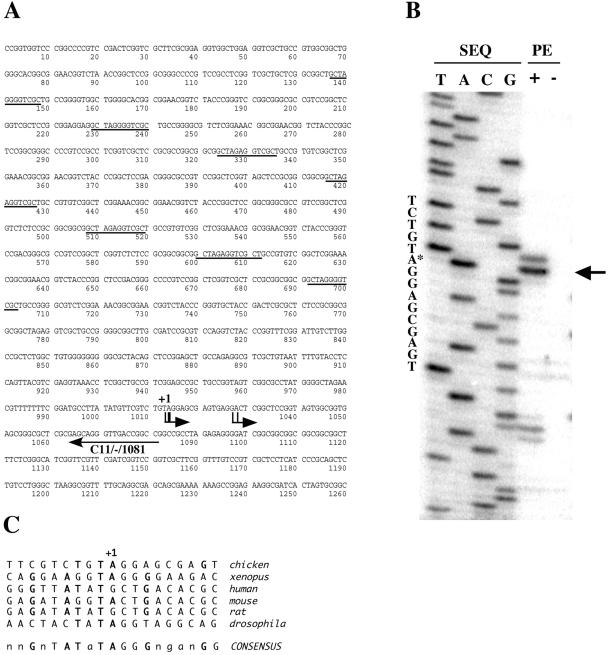

The 1,260 nt of the AgeI-SacI fragment of chicken genomic DNA were sequenced (Fig. 2A). Within the distal 800 nt, seven repeats of an ∼90-nt sequence were observed which were likely to correspond to activator sequences (21). In order to identify the transcription start point within the proximal 460 nt, primer extension was performed on total RNA extracted from QT6 cells transfected with construct 11. Oligonucleotide C11/−/1081 (Fig. 2A) was 32P labeled at its 5′ end with the T4 polynucleotide kinase and used as a primer for the extension assay and for parallel sequencing using construct 11 as a template. A major primer extension product was detected which defined nt +1 of the start of transcription (Fig. 2B). Three minor bands were observed, which indicated that initiation of transcription also occurred at nt −1, +14, and +15, although with a lower frequency (Fig. 2B). The sequences surrounding nt +1 of the RNApolI promoter sequence from chicken and from other species were aligned and showed homologies. Four of the seven most conserved nucleotides within the consensus sequence of the RNApolI transcription start point (as defined by Paule [21]) were represented in the chicken sequence (Fig. 2C, nucleotides in boldface).

FIG. 2.

Sequence analysis of the chicken RNApolI promoter. (A) Sequence of the 1,260 nt of chicken genomic DNA found to contain an RNApolI promoter. The 1,260 nt corresponding to the AgeI-SacI fragment of chicken genomic DNA subcloned in construct 11 (Fig. 1B) were sequenced. The sequence of the C11/−/1081 primer used for primer extension analysis is shown. The major and minor transcription start points, as determined by primer extension analysis (see Fig. 2B), are indicated by thick and thin arrows, respectively. The first residue of the major transcript is indicated as +1. Twelve nucleotides characteristic of each of the seven repeated sequences upstream from the transcription start point are underlined. The 1,260-nt sequence has been submitted to GenBank under accession number DQ112354. (B) Determination of the chicken RNApolI transcription start point by primer extension analysis. Primer C11/-/1081 (see panel A) was used for primer extension analysis on total RNA extracted from QT6 cells transfected with construct 11 (see Fig. 1B) in the presence (lane PE+) or in the absence (lane PE−) of T7 DNA polymerase. Primer C11/−/1081 was used in parallel for sequencing of construct 11 (SEQ). The sequence of the transcription start point expected from the major extended product in lane PE+ (indicated by an arrow) is shown. (C) Alignment of the sequences of the RNApolI transcription start points from chicken and other species. The RNApolI promoter sequences (nt −9 to +10) from the indicated species were aligned. The consensus sequence based on the alignment of 14 sequences, as defined by Paule (21), is shown at the bottom. The first residue of the major transcript is indicated as +1. The most conserved residues are indicated in boldface.

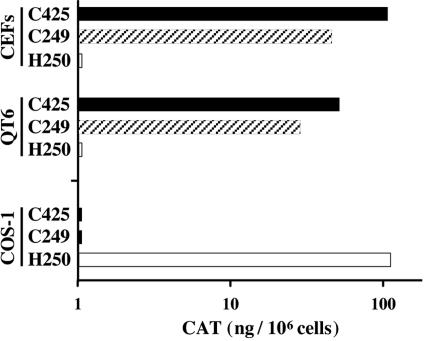

In order to determine whether the chicken RNApolI promoter sequence described above allowed efficient synthesis of influenza virus-like transcripts in avian cells, we constructed reporter plasmids similar to the human RNApolI promoter-based pPR7-FluA-CAT plasmid described earlier (4). The antisense CAT coding sequence, flanked by the 5′ and 3′ ends of the NS segment of WSN virus, was fused exactly between a sequence derived from the chicken RNApolI promoter (nt −1 to −425 or nt −1 to −249, starting directly upstream from the transcription initiation site referred to as +1 in Fig. 2A and C) and the hepatitis delta virus ribozyme sequence. The resulting constructs (pPRC425-FluA-CAT and pPRC249-FluA-CAT, respectively) were transfected into chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEFs), QT6, or COS-1 cells, together with plasmids allowing expression of PB1, PB2, PA, and NP cDNAs derived from the A/PR/8/34 influenza virus (described in reference 18). Plasmid pPR7-FluA-CAT was used as a control. As shown in Fig. 3, the levels of CAT in CEFs and QT6 transfected with pPRC425-FluA-CAT were in the same range as those measured in COS-1 cells transfected with pPR7-FluA-CAT. CAT levels were about twofold lower in avian cells transfected with pPRC249-FluA-CAT, suggesting that sequences present in pPRC425-FluA-CAT but not in pPRC249-FluA-CAT had an activator effect on transcription. Extracts prepared from avian cells transfected with pPR7-FluA-CAT or from COS-1 cells transfected with pPRC425-FluA-CAT or pPRC249-FluA-CAT contained no detectable levels of CAT, which was in agreement with the species specificity of RNApolI promoters. These observations demonstrated that the newly cloned chicken RNApolI promoter sequence allowed synthesis in avian cells of influenza virus-like transcripts that could undergo transcription and replication.

FIG. 3.

Synthesis of CAT protein as a result of the expression of virus-like CAT reporter RNAs under the control of the chicken RNApolI promoter in avian cells. CEFs, QT6 cells, and COS-1 cells were transfected with four plasmids encoding the PB1, PB2, PA, and NP proteins derived from influenza virus A/PR/8/34, together with plasmids that direct the expression of virus-like CAT reporter RNAs under the control of the chicken RNApolI promoter (pPRC425-FluA-CAT [C425] and pPRC249-FluA-CAT [C249]) or under the control of the human RNApolI promoter (pPR7-FluA-CAT [H250]). Cell extracts were prepared and tested for CAT levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at 24 h posttransfection.

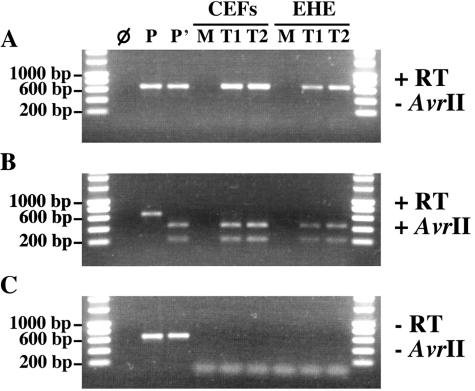

Based on these results, the reverse genetics system for the A/PR/8/34 NIBSC vaccine strain described by de Wit et al. (5) was modified. In each of the eight bidirectional transcription plasmids (kindly provided by R. A. M. Fouchier) the human RNApolI promoter sequence (nt −1 to −250) was replaced with nt −1 to −250 of the chicken RNApolI promoter. The murine RNAPolI terminator sequence was conserved, as it was found to be functional in avian cells (data not shown). The eight resulting plasmids were cotransfected into subconfluent monolayers of CEFs, which were then incubated with medium containing TPCK-trypsin (Worthington) at 0.1 U/ml. Infectious virus titers of about 102 to 103 PFU/ml were repeatedly detected in the supernatant at 72 h posttransfection, and the virus could be further amplified on CEFs up to titers of 107 PFU/ml. In order to ascertain that the virus was recovered from the plasmid transfection, a silent mutation was introduced into the HA gene sequence at nt 929, resulting in the presence of an additional AvrII site. As shown in Fig. 4, the identity of the recovered virus was verified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) amplification of the HA sequence around nt 929 and digestion of the amplified DNA with AvrII.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of the recovered viruses by RT-PCR. RNA was extracted from virions after three passages of the transfection supernatants on CEFs or after one round of amplification on embryonated hen's eggs (EHE). It was used as a template for RT-PCR with primers specific for the HA segment, positioned on each side of nt 929. Amplification was performed on samples derived from two independent transfections (T1 and T2). Amplification was performed in parallel on samples derived from the supernatant of mock-transfected cells (M) on the plasmids containing the sequence of the wild-type or mutant HA segment (P and P′, respectively), and on water (⊘). (A and B) The amplified DNA was subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel before (A) or after (B) digestion with AvrII. (C) A control reaction was performed in the absence of reverse transcriptase (−RT) in order to ensure that the amplification product was derived from vRNA and not from plasmid carried over from transfected cells.

Cloning of the chicken RNApolI promoter sequence thus allowed us to generate a bidirectional eight-plasmid system for reverse genetics of A/PR/8/34 influenza virus in avian cells. Recombinant virus was recovered with low titers (102 to 103 PFU/ml) compared to those obtained using reverse genetics in 293T cells (107 50% tissue culture infective doses/ml) (5). Optimization of the transfection protocol, as well as replacement of the cytomegalovirus promoter by an avian-specific promoter to direct expression of viral proteins from the bidirectional plasmids, might allow us to achieve higher titers.

Performing reverse genetics in avian cells will be of special interest in some fields of influenza virus research. Variants with a growth advantage may readily arise in tissue culture and a low proportion of such variants may be sufficient to modify the phenotype of the viral population, although they remain undetectable by sequencing analysis (17). Rapid selection of mutants upon two passages or even a single passage of human viruses in embryonated eggs has been documented (13, 22), and thus the reverse may also occur upon passage of avian viruses on mammalian cells. The reverse genetics system described here, avoiding any step of viral multiplication on mammalian cells, will be a useful tool for comparing antigenic properties of viruses produced in a mammalian versus an avian system or for studying molecular determinants that restrict the growth of avian influenza viruses in humans.

Reverse genetics systems offer the possibility to generate recombinant influenza virus strains, designed to be used either as inactivated or live attenuated vaccines (reviewed in references 23 and 24). Before such vaccines are licensed, a number of regulatory concerns will have to be addressed, including the cell substrate used for transfection. An MDCK and a Vero cell line meet the regulatory demands for production of inactivated influenza vaccine (2, 16, 20). However, the requirements for live vaccine are likely to be different, as potential adventitious agents produced by the cells are more of a concern (discussed in reference 15). Reverse genetics on a suitable avian cell line might represent an option for the production of recombinant live influenza vaccines in the future.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to R. Zoorob (Laboratoire de Génétique Moléculaire et Biologie du Développement, Villejuif, France) for providing cosmid C13-19, R. A. M. Fouchier (Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) for providing the human RNApolI-based bidirectional plasmids for A/PR/8/34 (NIBSC strain) reverse genetics, and J. Pavlovic (Institut für Medizinishe Virologie, Zurich, Switzerland) for providing the A/PR/8/34 expression plasmids. We thank Nicolas Escriou for helpful discussions.

This study was supported in part by the NOVAFLU 2001 (QLRT-2001-01034) program and by the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche, et de la Technologie (EA 302).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barman, S., L. Adhikary, A. K. Chakrabarti, C. Bernas, Y. Kawaoka, and D. P. Nayak. 2004. Role of transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail amino acid sequences of influenza A neuraminidase in raft association and virus budding. J. Virol. 78:5258-5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brands, R., J. Visser, J. Medema, A. M. Palache, and G. J. van Scharrenburg. 1999. Influvac: a safe Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cell culture-based influenza vaccine. Dev. Biol. Stand. 98:93-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burleigh, L. M., L. J. Calder, J. J. Skehel, and D. A. Steinhauer. 2005. Influenza A viruses with mutations in the m1 helix 6 domain display a wide variety of morphological phenotypes. J. Virol. 79:1262-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crescenzo-Chaigne, B., N. Naffakh, and S. van der Werf. 1999. Comparative analysis of the ability of the polymerase complexes of influenza viruses type A, B and C to assemble into functional RNPs that allow expression and replication of heterotypic model RNA templates in vivo. Virology 265:342-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Wit, E., M. I. J. Spronken, T. M. Bestebroer, G. F. Rimmelzwaan, A. D. M. E. Osterhaus, and R. A. M. Fouchier. 2004. Efficient generation and growth of influenza virus A/PR/8/34 from eight cDNA fragments. Virus Res. 103:155-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elleman, C. J., and W. S. Barclay. 2004. The M1 matrix protein controls the filamentous phenotype of influenza A virus. Virology 321:144-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flandorfer, A., A. Garcia-Sastre, C. F. Basler, and P. Palese. 2003. Chimeric influenza A viruses with a functional influenza B virus neuraminidase or hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 77:9116-9123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fodor, E., M. Crow, J. L. Mingay, T. Deng, J. Sharps, P. Fechter, and G. G. Brownlee. 2002. A single amino acid mutation in the PA subunit of the influenza virus RNA polymerase inhibits endonucleolytic cleavage of capped RNAs. J. Virol. 76:8989-9001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fodor, E., L. Devenish, O. G. Engelhardt, P. Palese, G. G. Brownlee, and A. Garcia-Sastre. 1999. Rescue of influenza A virus from recombinant DNA. J. Virol. 73:9679-9682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosveld, F. G., T. Lund, E. J. Murray, A. L. Mellor, H. H. Dahl, and R. A. Flavell. 1982. The construction of cosmid libraries which can be used to transform eukaryotic cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 10:6715-6732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guillemot, F., A. Billault, O. Pourquié, G. Béhar, A. M. Chaussé, R. Zoorob, G. Kreibich, and C. Auffray. 1988. A molecular map of the chicken major histocompatibility complex: the class II β genes are closely linked to the class I genes and the nucleolar organizer. EMBO J. 7:2775-2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman, E., G. Neumann, Y. Kawaoka, G. Hobom, and R. G. Webster. 2000. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6108-6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito, T., Y. Suzuki, A. Takada, A. Kawamoto, K. Otsuki, H. Masuda, M. Yamada, T. Suzuki, H. Kida, and Y. Kawaoka. 1997. Differences in sialic acid-galactose linkages in the chicken egg amnion and allantois influence human influenza virus receptor specificity and variant selection. J. Virol. 71:3357-3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K., T. Horimoto, Y. Fujii, and Y. Kawaoka. 2004. Generation of influenza A virus NS2 (NEP) mutants with an altered nuclear export signal sequence. J. Virol. 78:10149-10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemble, G., and H. Greenberg. 2003. Novel generations of influenza vaccines. Vaccine 21:1789-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kistner, O., P. N. Barrett, W. Mundt, M. Reiter, S. Schober-Bendixen, and F. Dorner. 1998. Development of a mammalian cell (Vero) derived candidate influenza virus vaccine. Vaccine 16:960-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medeiros, R., N. Escriou, N. Naffakh, J. C. Manuguerra, and S. van der Werf. 2001. Hemagglutinin residues of recent human A(H3N2) influenza viruses that contribute to the inability to agglutinate chicken erythrocytes. Virology 289:74-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naffakh, N., P. Massin, N. Escriou, B. Crescenzo-Chaigne, and S. van der Werf. 2000. Genetic analysis of the compatibility between polymerase proteins from human and avian strains of influenza A viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1283-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann, G., T. Watanabe, H. Ito, S. Watanabe, H. Goto, P. Gao, M. Hughes, D. R. Perez, R. Donis, E. Hoffmann, G. Hobom, and Y. Kawaoka. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9345-9350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palache, A. M., H. S. Scheepers, V. de Regt, P. van Ewijk, M. Baljet, R. Brands, and G. J. van Scharrenburg. 1999. Safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of Madin-Darby canine kidney cell-derived inactivated influenza subunit vaccine: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. Dev. Biol. Stand. 98:115-125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paule, M. R. 1998. Promoter Structure of class I Genes. In M. R. Paule (ed.), Transcription of ribosomal RNA genes by eukaryotic RNA polymerase I. Springer-Verlag/R. G. Landes Company, New York, N.Y.

- 22.Rogers, G. N., R. S. Daniels, J. J. Skehel, D. C. Wiley, X. Wang, H. H. Higa, and J. C. Paulson. 1985. Host-mediated selection of influenza receptor variants. Sialic acid α2,6Gal specific clones of A/duck/Ukraine/1/63 revert to sialic acid α2,3Gal-specific wild-type in ovo. J. Biol. Chem. 260:7362-7367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subbarao, K., and J. M. Katz. 2004. Influenza vaccines generated by reverse genetics. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 283:313-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood, J. M., and J. S. Robertson. 2004. From lethal virus to life-saving vaccine: developing inactivated vaccines for pandemic influenza. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:842-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]