Abstract

Background

One of the earliest steps in synaptogenesis at the neuromuscular junction is the aggregation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at the postsynaptic membrane. This study presents quantitative analyses of receptor and α-Dystroglycan aggregation in response to agrin and laminin-1, alone or in combination.

Results

Both laminin and agrin increased overall expression of receptors on the plasma membrane. Following a 24 hour exposure, agrin increased the number of receptor aggregates but did not affect the number of α-Dystroglycan aggregates, while the reverse was true of laminin-1. Laminin also increased receptor concentration within aggregates, while agrin had no such effect. Finally, the spatial distribution of aggregates was indistinguishable from random in the case of laminin, while agrin induced aggregates were closer together than predicted by a random model.

Conclusions

Agrin and laminin-1 both increase acetylcholine receptor aggregate size after 24 hours, but several lines of evidence indicate that this is achieved via different mechanisms. Agrin and laminin had different effects on the number and density of receptor and α-Dystroglycan aggregates. Moreover the random distribution of laminin induced (as opposed to agrin induced) receptor aggregates suggests that the former may influence aggregate size by simple mass action effects due to increased receptor expression.

Background

Aggregation of acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) at the post-synaptic muscle membrane is the initial step in synaptogenesis at the neuromuscular junction, and is essential for reliable and rapid synaptic communication. Agrin is the only known in vivo stimulus for the initiation of receptor aggregation. However, several other researchers have reported that laminins including laminin-1 (LN1) also induce receptor aggregation in cultured mouse muscle cells [1-3]. At this time the LN1 stimulation pathway is not well understood, but it has been argued from several lines of evidence to be at least partially distinct from the agrin pathway. This is based on aggregation assays showing different time courses, additive dose response relationships, and differential co-localization of the dystrophin complex, and on biochemical observations indicating the lack of requirement for MuSK, and the lack of tyrosine-phosphorylation of receptors during LN1 but not agrin induced aggregation [1,2,4]. The very minimal receptor aggregation seen in agrin deficient mice certainly argues that laminins are not sufficient to trigger receptor aggregation [5]. More recently we have shown that agrin and LN1 induced aggregates can also be differentiated on the basis of the ultrastructural arrangement of receptors within aggregates[6].

Laminins are major components of the extracellular matrix and exist in many isoforms with varying functions including cell adhesion, neurite outgrowth, and cellular signaling [7-10]. Laminin binds agrin[11], and colocalizes with AChR aggregates [12-14]. It also binds with α-Dystroglycan (α-DG), an important part of the dystrophin/utrophin glycoprotein complex (Reviewed in [15,16]). The dystrophin complex is also found concentrated at the neuromuscular junction with AChRs and laminin, and for this and other reasons is thought to be involved in both formation and maintenance of the NMJ [2,17-23].

Taken together these observations have led to the hypothesis that LN1 serves as a secondary or supporting stimulus for agrin induced AChR aggregation[1,2,24]. The present study is directed at a quantitative examination of the interaction between the signal transduction pathways for agrin and LN1 induction of AChR aggregates and colocalized α-DG aggregates.

Results

Using stimulus protocols similar to other researchers [1-3], we identified a maximal AChR aggregation response to LN1 for 48 hours at a concentration of 30 nM in preliminary experiments. This produced a significant increase in receptor aggregate size and number as compared to the unstimulated controls. In order to probe possible interactions between agrin and LN1 aggregate induction, a separate set of protocols was devised in which agrin and laminin, alone or in combination, were applied for parts of this 48 hour period. These protocols are summarized in Table 2 and described more fully in Materials and Methods, and form the basis of the observations presented in this study.

Table 2.

Agrin and LN1 aggregation stimulus protocols. Note that the medium for all cultures was changed at t = 24 hrs, either to fresh medium or medium with stimulus.

| Treatment | Abbreviation | Stimulus |

| 1) Control | C | None |

| 2) Agrin alone | A | Agrin 24–48 hrs |

| 3) LN1 alone | L | LN1 24–48 hrs |

| 4) Agrin + LN1 | AL | Agrin+LN1 24–48 hrs |

| 5) Agrin then LN1 | A>L | Agrin 24–26 hrs: LN1 26–48 hrs |

| 6) LN1 then Agrin | L>A | LN1, 24–26 hrs: Agrin 26–48 hrs |

Acetylcholine receptor aggregation

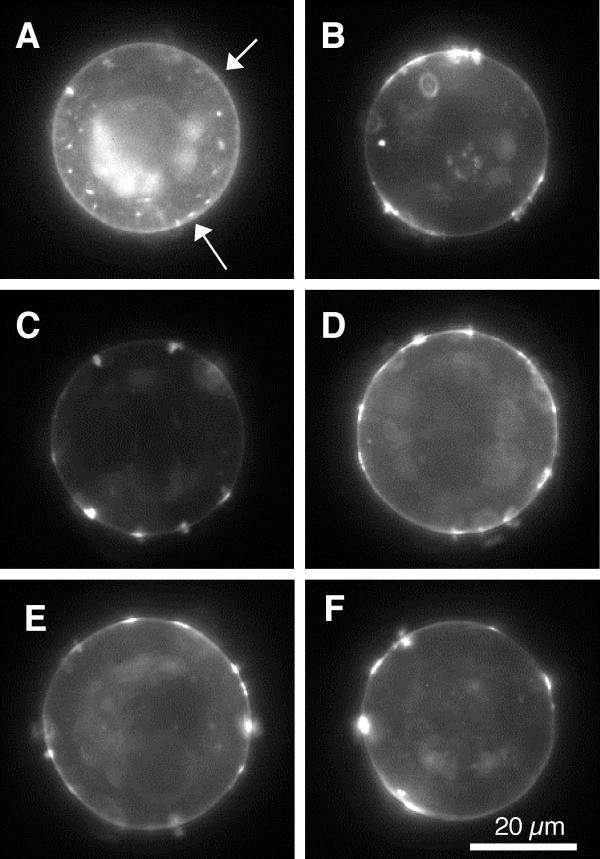

In order to examine the possible interactions between agrin and LN1, combination experiments were conducted in which the total exposure time to individual stimuli was less than or equal to 24 hours. Examples of the effects of agrin and LN1 alone or in combination using these protocols are shown in Figure 1. It is clear from visual inspection that either stimulus, or the stimuli together, increase the prominence of receptor aggregates (Figure 1A vs. 1B,1C,1D,1E,1F). To quantify these differences the quantitative analyses described in Materials and Methods were carried out, and the results are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Typical fluorescent micrographs of rhodamine labeled AChR distributions after stimulation with agrin or laminin-1 alone or in combination. See Table 2 for stimulus protocols. Note that the analysis is restricted to the perimeter of the images (Materials and Methods) A, no stimulus. There is a subtle presence of small aggregates about the cell perimeter (arrows). B, Agrin. C, laminin. D, Agrin and Laminin. E, Agrin followed by laminin. F, laminin followed by Agrin. All of these latter conditions consistently display larger, more intense receptor aggregates than the control cells in A.

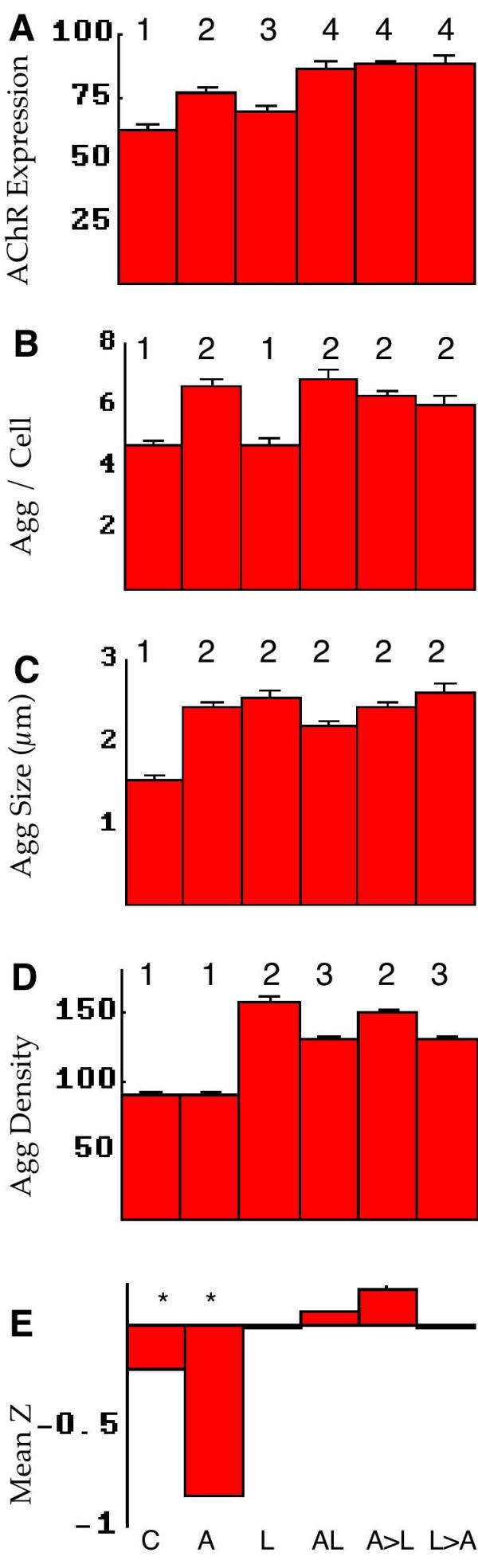

Figure 2.

Quantitative analysis of AChR aggregate parameters. The stimulus protocols for all panels are shown at the bottom: C control (no stimulus), A agrin, L laminin-1, AL agrin and laminin, A>L agrin followed by laminin, L>A laminin followed by agrin. See Table 2 for protocol details. A-D, numbers at the top indicate statistical groupings based on one factor ANOVA F tests, p < .05. A, expression of receptors (arbitrary units). Both agrin and LN1 increased the label intensity of AChRs significantly, and agrin clearly more so than LN1. In all combinations assayed the effects of agrin and LN1 on receptor expression were additive. B, number of aggregates detected per cell. On this basis LN1 alone was similar to control cells, while agrin alone or in combination gave similarly increased numbers of aggregates. C, aggregate size in micrometers. In this case both agrin and laminin, alone or in combination, produced similarly enhanced aggregate size compared to control cells. D, aggregate density (arbitrary units). With regard to this metric agrin alone was indistinguishable from control cells, while laminin alone or in combination showed a significant increase in density. E, the mean Z corresponding to the average separation between aggregates. For random distributions this metric has an expected value of 0. Significant deviations from random separation (p < .01) are marked with *. When significant, negative values indicate that aggregates are closer together than random distributions, and positive values would indicate aggregates farther apart than average (see Materials and Methods). In this set of experiments controls showed a small but significant deviation from randomness, and agrin alone showed a large deviation. In both cases the aggregates were found to be further apart than expected at random.

The present experimental system provides an important opportunity to estimate changes in the average AChR expression by sampling the fluorescence signal from the section of membrane representing the meridian of the spherical cell. Average receptor expression was found to be significantly increased following exposure to agrin, and less so although still significantly in response to LN1 (Figure 2A). Interestingly, the combination experiments seem to indicate that these effects are additive, suggesting that the two stimulation pathways do not share a common rate-limiting step. Moreover 24-hour exposure to LN1 did not bring about a significant increase in aggregate number, while agrin did (alone or in combination with LN1: Figure 2B). Both agrin, LN1, and combinations of the two significantly increased aggregate size (Figure 2C). In terms of aggregate density (the concentration of receptors within aggregates) the result was the mirror image of that for aggregate number: agrin alone was indistinguishable from controls, while laminin alone or in combination significantly increased density (Figure 2D). Figure 2E represents a novel analytical approach in which the distribution of aggregates on each cell is compared to that expected assuming random placing of the aggregates (i.e. spatial independence: neither cooperativity nor competition). The "mean Z" values, when significantly different from zero, indicate the direction of deviation from a random distribution; mean Z < 0 indicates aggregates are closer together than would be expected at random (cooperativity) while values > 0 indicate aggregates are further apart than expected (competition). The observed receptor aggregates were found to be significantly different from random only with agrin alone as the stimulus, in which case they were found closer together, indicating spatial cooperativity.

α-Dystroglycan aggregation

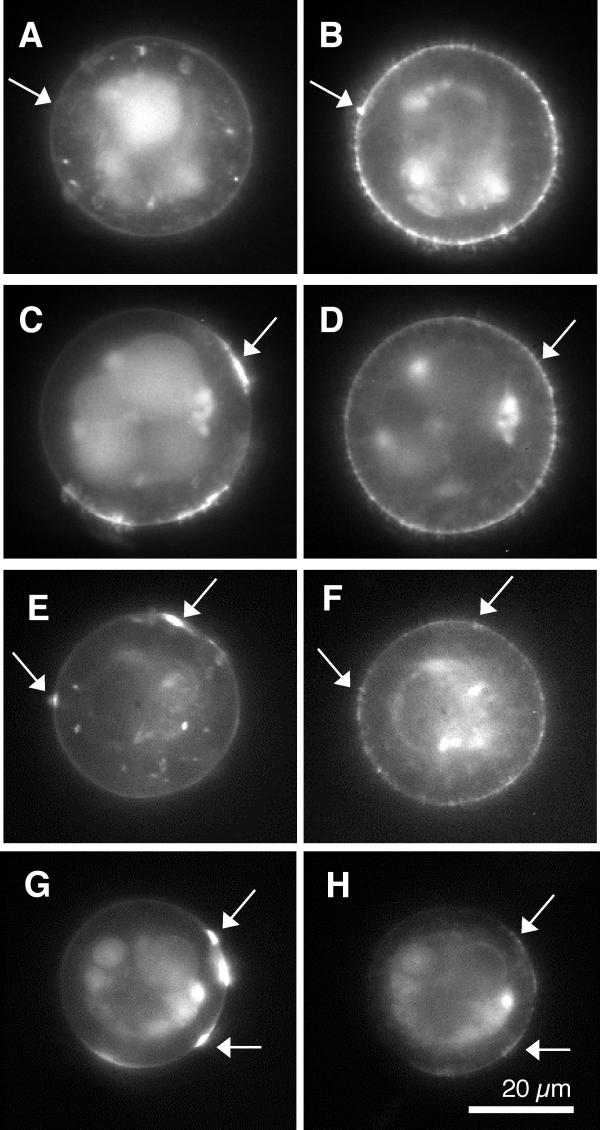

Because of various lines of evidence connecting α-DG to receptor aggregation and to differences in agrin and LN1 pathways of induction, we next examined the effects of the stimulus protocols on cells double labeled for AChRs (fluorescein) and α-DG (rhodamine) to examine the extent of correlation between the labels (see below) and the α-DG distributions. Typical results are shown in Figure 3, in which α-DG distributions are seen to be quite punctate with examples of both kinds of non-correlation (3AB, CD), demonstrating a lack of contamination of signals between the two filter sets. There are also examples in which the labels do appear to be somewhat correlated (3 EF, GH). Quantitative analyses of the α-DG distributions are summarized in Figure 4 (the observed AChR aggregates were consistent with the observations presented above but were not pooled with those data because they were not performed on matching sister cultures).

Figure 3.

Typical fluorescent micrographs of double labeled cell pairs following the stimulus protocols. Images on the left were fluorescein labeled for AChRs, while the corresponding images on the right were rhodamine labeled for α-DG . Note that the analysis is restricted to the perimeter of the images (Materials and Methods) A, B, no stimulus. The arrows illustrate a lack of contamination of the fluorescein (left) signal by the rhodamine (right) image. C, D, Agrin; arrows illustrate the absence of contamination of the rhodamine (right) image by the fluorescein label on the left. E, F, laminin; the arrows illustrate modest correlation between the two labels. G, H, Agrin and Laminin. The arrows indicate regions of substantial correlation between the two molecular distributions. The examples of correlation, and the lack thereof, are for purposes of illustration only and not representative of the respective stimulus conditions. See text for quantitative measures of correlation between the two molecular distributions.

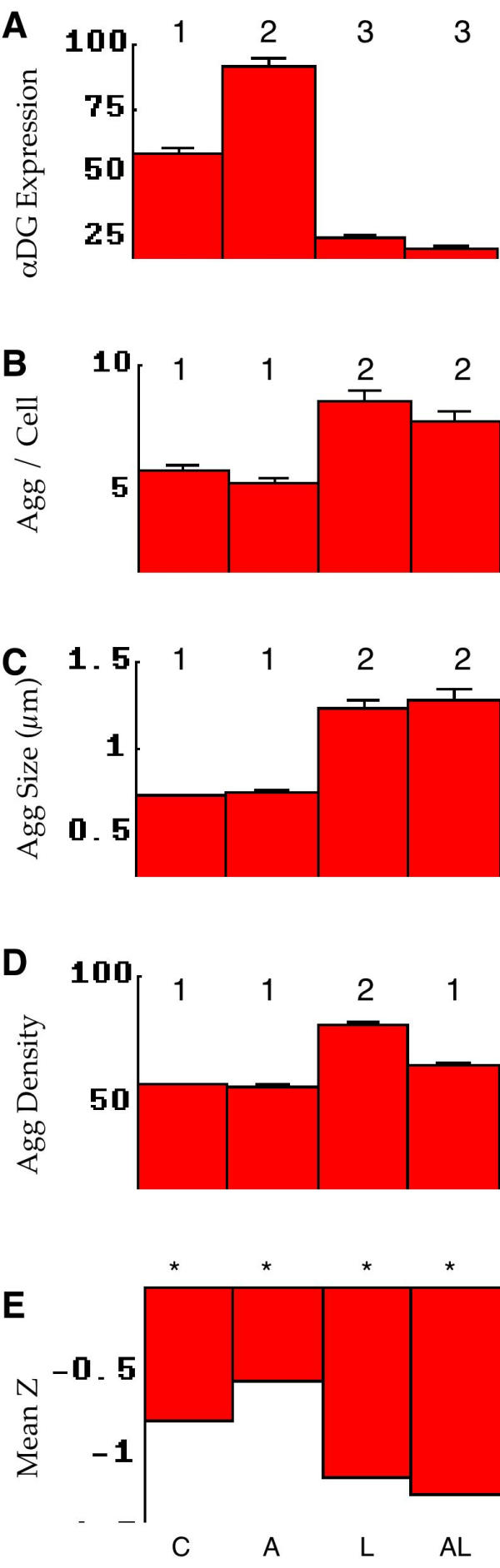

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of α-DG aggregate parameters. The stimulus protocols for all panels are shown at the bottom: C control (no stimulus), A agrin, L laminin-1, AL agrin and laminin. A-D, numbers at the top indicate statistical groupings based on one factor ANOVA F tests, p < .05. A, density of α-DG (arbitrary units). Agrin clearly increased the expression of α-DG on the cell surface. The effects of LN1 cannot be assessed, because it competes for the binding of the immunological probe for α-DG. B, number of aggregates detected per cell. On this basis LN1, alone or in combination with agrin, significantly increased the number of aggregates; agrin by itself had no effect on aggregate number. C, aggregate size in micrometers. These results parallel those for aggregate number; laminin alone or in combination increased aggregate size. D, aggregate density (arbitrary units). Here we find a deviation from the pattern in A and B: only LN1 by itself causes density increase, while in the presence of agrin this increase is largely blocked. E, the mean Z corresponding to the average separation between aggregates. Significant deviations from random separation (p < .01) are marked with *. Unlike the AChR distributions shown in Figure 2D, α-DG aggregate distributions are found closer together than random under all experimental conditions. This cooperativity is enhanced by LN1 alone or in combination with agrin.

Agrin clearly increased the expression of α-DG as judged by label intensity (Figure 4A), while the effects of LN1 (alone or in combination) could not be assessed because it competed with the immunological probe used in labeling. There are interesting similarities as well as differences in the effects of the two stimuli on the remaining measures of distribution. First, agrin showed no effect on the number of α-DG aggregates per cell, while LN1 (alone and in combination) induced an increase (Figure 4B). This is the reverse of the finding for AChR aggregates (Figure 2B). α-DG aggregate size follows a similar pattern of increase by LN1 (alone or in combination) but not agrin (Figure 4C), but in this case it is the same as the finding with AChRs (Figure 2C). Again in agreement with AChR observations, α-DG aggregate density is increased by LN1 but not agrin (Figure 4D) – however in this case it appears that this increase is prevented by agrin, while in the case of AChRs the combination follows the LN1 alone phenotype of increased aggregate density. Finally, the meanZ values (Figure 4E) clearly show that 1) α-DG aggregates are closer together than random (cooperativity) in all cases, and apparently more so after stimulated with LN1.

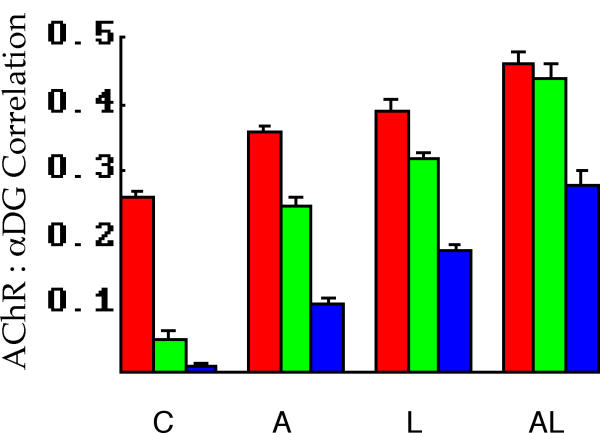

The last analysis performed was that of measuring the correlation between AChR and α-DG distributions in response to the stimulus protocols. As discussed in Materials and Methods each of the three measures used here has some advantages over the others. In the present experiments the trends are all quite similar, however, and are shown in Figure 5. All correlation measures show progressive and significant increases from control to agrin to LN1 to agrin/LN1. The more physiologically meaningful metrics (high frequency and above threshold correlation) are quite low in controls, indicating that aggregates of the two components are essentially independent in their distributions under these conditions. This independence is lost with the application of either of the two stimuli, and the effects of agrin and LN1 together are greater than either alone. It should be noted however that even under these conditions the high frequency correlation, for example, indicates that about 19% (0.442) of the variation in either distribution is predicted by the other. Thus although the aggregate distributions are not statistically independent, they are also not strictly colocalized.

Figure 5.

Analysis of AChR and α-DG label correlations for the stimulus protocols. The stimulus protocols for all panels are shown at the bottom: C control (no stimulus), A agrin, L laminin-1, AL agrin and laminin. Red bars, raw data correlation. Green bars, high frequency correlation (see Figure 7, Materials and Methods). Blue bars, above threshold correlation. The latter two metrics (green and blue) are the most relevant to the question of molecular aggregation, and show little if any correlation under control conditions. All metrics show progressive and significant increases as the stimulus protocol is changed to agrin, LN1, and agrin with LN1.

Discussion

A summary of the findings with respect to expression and standard aggregate statistics is shown in Table 1. Before examining the patterns presented a brief discussion of the analyses and their limitations is in order.

Table 1.

Summary of findings with respect to molecular aggregation in response to agrin, LN1, and combination stimuli. AL, agrin and laminin. Sequential administrations were similar to the AL combination and have been omitted for clarity. + indicates significant increase from controls, – indicates no increase, and ++ indicates an apparently additive effect of the combination of stimuli. The -(+) indicates that while LN1 did not increase receptor aggregate number during the 24 hour exposure in combination experiments, it did over the 48 hour exposures presented at the beginning of Results. na (not available) is used to indicate the lack of confidence in measurements of α-DG expression following LN1 application (see Results).

| Molecule | Stimulus | Expression | Ag/Cell | Ag Size | Ag Dens |

| AChR | agrin | + | + | + | - |

| AChR | LN1 | + | -(+) | + | + |

| AChR | AL | ++ | + | + | + |

| αDG | agrin | + | - | - | - |

| αDG | LN1 | na | + | + | + |

| αDG | AL | na | + | + | - |

With respect to average expression of AChRs and α-DG, the approach assumes these molecules are uniformly distributed along the z-axis (one sample of which – the cell meridian – is sampled). Confocal sections support this generalization (not shown) so that these samples of the cell surface can be taken as representative measures of overall expression.

There are additional subtleties involved in measuring aggregate size and number. The presented data represent aggregates detected or observed per cell image, so as to provide for ready comparison to other published work. These values are quite different from the best estimates of the number of aggregates actually present on a per cell basis. Assuming aggregates are uniformly distributed along the z axis, and that they are globular in shape (well approximated by circles on average), the probability of detecting an aggregate of diameter d on a cell of diameter D is

![]()

This means that estimates of the true aggregate number per cell are a larger multiple of the number observed when the aggregates are small. This can be grasped qualitatively by imagining optical sections near (along the z axis) to those presented. By uniformity these would appear on average quite similar in aggregates detected to the meridian samples, but a larger fraction of these would be new sections of previously detected aggregates as their size increased. Thus for example the data presented in Figure 2B (4.69 ± .21, controls; 6.65 ± .25, agrin) are corrected to 296 ± 16 (controls) and 357 ± 21 (agrin) estimated aggregates per cell. The trends presented (Results) are thus somewhat diminished (a 20% increase instead of a 42% increase), but the increases and their statistical significance remain.

As with aggregate number the observed size is not the best estimate of actual aggregate size; because many aggregates detected are actually slightly above or below the meridian their size in cross section will be underestimated. Geometrical considerations, given the assumptions outlined above, lead to the conclusion that observed aggregate size is reduced from actual size by about 21%. This estimate is not sensitive to aggregate size (it would be completely independent given perfect optical sectioning) and therefore has no effect on the trends reported.

The estimates presented for the increase in number of receptor aggregates induced by agrin are considerably smaller than those in previous studies (reviewed in [25]). This may in part be due to the algorithms used: previous studies have depended upon the human observer to count aggregates defined as fluorescent regions above some threshold in size, while the approach described here utilizes software which is equally sensitive to very small aggregates. Alternatively, it may be that spherical muscle cell cultures, attached to the substrate by a small percentage of the membrane area, are intrinsically different in their response to agrin due perhaps to less organized cytoskeleton.

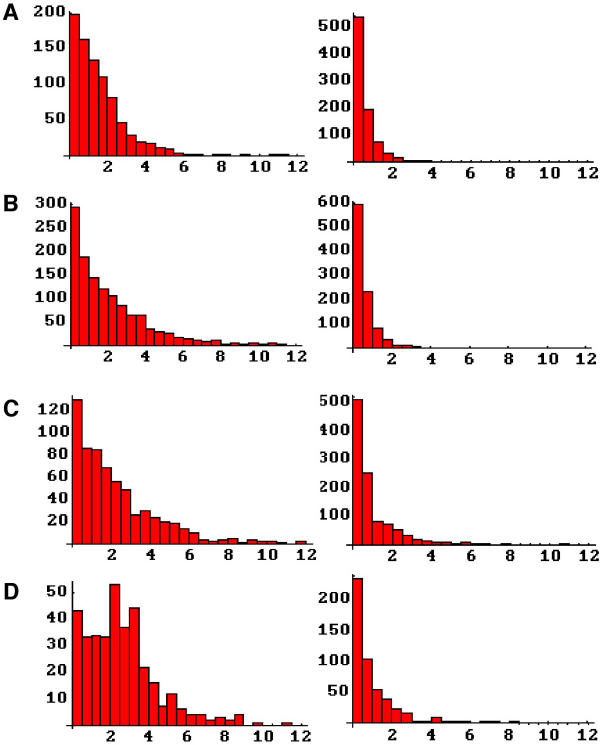

The distributions of aggregate sizes reveal additional information about the induction of aggregation (Figure 6). In the case of AChRs, we see that agrin actually reduces the population of intermediate size aggregates (1–2 μm) in favor of larger aggregates (Figure 6B left). Laminin similarly increases the frequency of large aggregates, but also increases the number of intermediate size aggregates (Figure 6C left). Together the two stimuli broaden out the distribution, further increasing both intermediate and larger sized aggregates (Figure 6D left). Amongst the α-DG aggregate distributions there is no difference between controls and cells stimulated with agrin while LN1 alone or with agrin increases both intermediate and larger αDG aggregates (Figure 6A,6B,6C,6D, right).

Figure 6.

Aggregate size distributions following the various stimulation protocols. Each left-right pair represents the frequency histograms of aggregate size for AChRs (left) and α-DG (right). A, controls (no stimulus). B, agrin. C, laminin. D, agrin and laminin. All abscissas are aggregate size in microns.

The significant patterns emerging from the data are as follows (see Table 1). First, receptor expression was increased by both agrin, laminin, and their combinations. This means that mass action effects of greater receptor expression could in principle account for some of the changes in aggregate parameters as discussed below. It is of further significance that the effects seem to be additive, suggesting that the mechanisms involved are independent. α-DG expression is also increased with agrin, while the expression in laminin stimulated cells could not be determined.

Second, there is a reversal in the roles of agrin and laminin induction with respect to the numbers of receptor and αDG aggregates per cell. Agrin increases the number of receptor aggregates but LN1 does not, while the reverse is true of α-DG aggregates.

Third, aggregate size is reversed for AChRs and αDG following stimulation by agrin. Agrin increases aggregate size for receptors, but decreases it for α-DG. This is consistent with a recent finding that receptor aggregate size increased in α-DG-deficient myotubes[23].

Finally, receptor aggregate size was increased by all stimulus combinations, but the number of aggregates per cell and the aggregate density is reversed for agrin and LN1; the former increases aggregate number but not density, while the latter increases aggregate density but not number in the standard protocols. This similarity in aggregate size (agrin vs. LN1) contradicts previous findings in C2 myotubes, while increase in aggregate density via LN1 stimulation is in agreement with this report[1]. We should also note however that these measures of density are averaged over the micron scale and are not inconsistent with lowered density on the nanometer scale as previously reported[6].

Correlation of aggregates

This is the first report in which entire slices of membrane have been compared in their entirety for correlation of AChR and α-DG distribution. Accordingly the question arises as to how this approach can be compared with previous studies which demonstrate a visible colocalization of AChRs and α-DG in muscle cells stimulated by nerve terminals [19] or agrin [4,20,26,27]. First we note that the present results do support a significant colocalization of the two molecules in agrin stimulated cells as compared to controls (Figure 5), in general agreement with previous findings. That the correlation coefficient never approaches unity is also consistent with the previous work – in general it has been found that AChR aggregates contain α-DG, but visible concentrations of α-DG can be found in the absence of AChRs. Thus there appears to be a "one way correlation"; whether the stimulus is agrin or laminin AChR aggregation is an excellent predictor of α-DG aggregation, but the converse is not found (see particularly [4]). This lack of reciprocity will of course reduce the label correlation as measured in the present study.

Nevertheless it is apparent from visual observations (e.g. Figure 3) that there is less perfect colocalization of α-DG within AChR aggregates in the present study than reported previously (see for example [4] Figure 9 for a comparable study using Xenopus muscle cell cultures). It seems likely that this is due to the more minimalist culture conditions used in the present study – younger cells, plated on clean glass coverslips, lacking in extensive adhesion plaques and presumably endowed with a less stratified cytoskeleton. This is supported by the finding that 48 hours of laminin stimulus is required for an increase in aggregate number, while in the 24-hour protocol reported at present only aggregate size is increased. It is to be expected that with greater stimulation time the colocalization would increase, which presents the prospect of studying the relative dynamics of AChR and α-DG colocalization.

Distribution of aggregates

The observation that receptor aggregates are distributed differently than would be expected at random deserves further comment. As a first approximation there are three ways that receptor aggregates on a given cell could be distributed: randomly, closer together, or further apart than random. A random distribution would imply that aggregate dynamics (initiation, development, and dispersal) are independent of that for neighboring aggregates. Aggregates distributed further apart than random would imply a local competition for the molecules required for aggregate formation or development or alternatively, regionally increased levels of components which cause aggregate dispersal. Conversely, a distribution of aggregates closer together than random could result from a local reduction in the rate of dispersal, or a regionally enhanced rate of initiation or development of new aggregates. Of course these effects need not be mutually exclusive – it could be that aggregate dynamics are cooperative in small regions of membrane while simultaneously competitive over larger scales.

We found that spontaneous receptor aggregates were distributed closer together than random (Figure 2E) although the deviation was small and only just significant statistically. However agrin and LN1 appear to have very different effects on aggregate distribution. Agrin dramatically increased the proximity of receptor aggregates, while laminin stimulation resulted in random distributions of aggregates. Interestingly, this latter effect was dominant, in the sense that agrin/LN1 combinations also resulted in random distributions. α-DG distributions were found to be closer together than random in all conditions examined.

Conclusions

The present data largely corroborate and extend previously published accounts. We did not find the substantially larger number of LN1 (as opposed to agrin) induced aggregates reported previously [1], perhaps because of the shortened application of laminin used in the presented experiments. Also, while laminin stimulation increased the colocalization of AChRs and αDG in our experiments, agrin also produced a similar increase (Figure 5). These effects on colocalization appear to be additive, as did the overall stimulation of AChR expression (Figure 2A). Both of these findings suggest distinct pathways for agrin and laminin induced receptor aggregation, and this conclusion is strengthened by the observation laminin, unlike agrin, dramatically increased the density of receptors within aggregates (Figure 2D), as reported previously [1]. The independence of pathways is also indicated by the profoundly different effects of the two stimuli on aggregate distribution.

This last observation, indicating the absence of cooperativity or competition amongst LN1 induced aggregates, invites the question of whether the results of laminin stimulation can be explained by simple mass action effects of increased receptor expression. At present we can produce no evidence to rule out this possibility. Increased expression of AChRs could decrease the dissolution of aggregates, thereby increasing aggregate size, density, and (over time) number. This would also explain the longer time required for LN1 induction of aggregates as well as the additivity seen here and in previous reports. Whether or not the effects of LN1 on aggregation dynamics can all be attributed to an increase in receptor expression, it seems clear from several lines of evidence that the mechanism is distinct from that of agrin induction, and that the physiological effects of laminin are permissive rather than instructive for receptor aggregation.

Materials and Methods

Xenopus culturing and fixation

Briefly, skeletal muscle somites are dissected from stage 20–22 Xenopus laevis embryos in collagenase/Steinberg's solution, dissociated for 8–10 minutes in Ca++Mg++ free solution, triturated, and cultured on clean 24 × 60 mm coverslips in 60 μl of culture medium (85% Steinberg's solution, 10% Leibovitz's L-15 medium, 5% fetal bovine serum, 50 μg/ml Gentamycin, pH7.8). Cultures were maintained in 100 × 15 mm plastic petri dishes in a humidified, darkened chamber (23°C) for 48 hours before fluorescent labeling and microscopy. Stimulus protocols involving laminin-1 (LN1, 30 nm, Sigma, L-2020), agrin (1:40, courtesy of Dr. Herman Gordon), or some combination/sequence are summarized in Table 2, Results. In all 48 hour experiments, the medium was changed at approximately 24 hours whether or not additional stimuli were applied. Note that the indicated incubations times for the two stimuli represent the times for which medium containing soluble stimulus was applied – it may well be that effective stimulation on the cell surface extends for a considerable period after the medium is changed.

Labeling and imaging

Labeling for fluorescent microscopy was performed on live cells at room temperature. AChRs were labeled with rhodamine (single label experiments) or fluorescein (double label experiments) conjugated αBGT (300 nM, Molecular Probes, T-1175/T-1176), and α-DG with a monoclonal antibody (1:1000, Upstate Biotechnology, 05–298, 45 minutes) followed by a secondary antibody (Rhodamine-Goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:100, Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, 115-025-003, 45 minutes). Label dilution and cell washing were carried out in culture medium.

Cell images were captured for analysis using a Zeiss Axiovert 10 microscope with Zeiss Plan Neofluor 40 × oil-immersion objective (n.a. = 1.3) and a 12-Bit Photometrics digital camera system (model CH250). To avoid observer bias, cells were first observed in bright field and randomly chosen from among the group of healthy spherical cells before observing them in fluorescence.

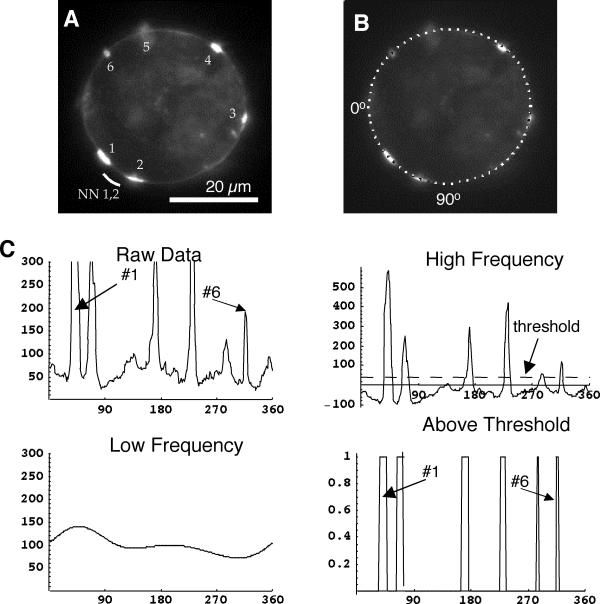

Analysis of fluorescence micrographs

Custom written software in C and Mathematica® was used to generate detailed, quantitative membrane fluorescence information from each cell image[28,29]. In the first phase, the intensity of membrane fluorescence as a function of position is tabulated (Figure 7B,7C, Raw Data). These measurements are then analyzed to provide statistics on the number, size, density, and position of each aggregate on each cell Figure 7C. The analysis is not perfect; in particular small aggregates close together may be scored as single larger aggregates. Nonetheless the analysis provides objective comparisons between the different conditions under examination.

Figure 7.

Quantitative analysis of fluorescent micrographs. A, fluorescent micrograph of rhodamine labeled AChRs at the meridian of the cell, showing six aggregates labeled 1–6. For each aggregate there is an associated nearest neighbor distance – the lesser of the distances to its two flanking neighbors. Aggregates #1 and #2 happen to have the same nearest neighbor distance, indicated by the white arc. B, the same cell as in A overlain to illustrate sector analysis. The software identifies the cell perimeter and represents it as a series of 256 sectors, starting at the left and proceeding counter-clockwise. In B every fourth sector is marked in white to illustrate its size and position. C, plots of sequential sector analysis. Raw Data is simply a plot of sector intensity vs. position in degrees, where the arrows indicate the corresponding aggregates identified in A. The data are processed to produce the High Frequency components, which can be thought of as the original data with the Low Frequency (gradually changing) components removed. A threshold is applied to the high frequency components (dashed line) to identify the Above Threshold aggregates, where again the arrows indicate aggregates corresponding to A.

New to this report, the positional information was used to quantify the distribution of aggregates about the cell surface. First, the nearest-neighbor distance is found for each aggregate on cells containing more than one aggregate (Figure 7B). For each cell, the mean of these nearest neighbor distances is calculated. Next the number and sizes of aggregates on a given cell are used to run repeated (1000) simulations assuming a random placement of the same sized aggregates. For each simulation run the mean nearest neighbor distance is calculated, so that together the runs provide an expected value and expected standard deviation for this parameter under the assumption of a random distribution. These values, corresponding to a given cell's aggregates, are then used to form a z-score from the observed mean nearest neighbor distance of the cell:

(observed-expected)/standard deviation.

Finally, the expected value for all z-scores from a given experimental condition is 0 given a random distribution, negative if the aggregates are closer together than random, and positive if the aggregates are further apart than random. The significance of any deviation from randomness is tested by summing the z-scores to form a χ2 statistic.

Also new to this report is testing of the correlation between label intensities in the double label experiments. Correlation is a statistical measure of the relationship between two variables based on the covariance of those variables normalized by their standard deviations. In these experiments, the two variables are the label intensities of two fluorescent labels representing the two proteins of interest in the experiment. Correlations are measured for raw data, high frequency data, and above threshold or aggregate data (see Figure 7). The raw data provide a baseline measurement without any manipulation of the data, but include low frequency (gradual) changes in fluorescence which are less interesting. The high frequency correlation eliminates this contamination and avoids the somewhat arbitrary imposition of a threshold, while the above threshold correlation is intuitively a better measure of what we mean by "colocalization of aggregates" but of necessity depends upon the threshold chosen. Fortunately in the present work all three measures show the same general trends.

List of abbreviations

AChR Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

αBGT α-Bungarotoxin

αDG α-Dystroglycan

LN1 Laminin-1, EHS Tumor Laminin, or α1, β1, γ1-Laminin

Author contributions

Author 1 (LKL) performed or supervised the experimental work and contributed to experimental design, interpretation, and manuscript drafting.

Author 2 (DDK) was responsible for microscopy training and made significant contributions to experimental design, execution, and interpretation.

Author 3 (JS) conceived of the study and contributed to experimental design, developed the computer analysis software, and had primary responsibility for manuscript drafting.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IBN97-24035, and American Heart Association – Hawaii Affiliate Grant HIGS-17-95. We gratefully acknowledge the gift of Agrin(4,8) from Dr. Herman Gordon.

Contributor Information

Lara K Lee, Email: laraklee@yahoo.com.

Dennis D Kunkel, Email: kunkel@hawaii.rr.com.

Jes Stollberg, Email: jesse@pbrc.hawaii.edu.

References

- Sugiyama JE, Glass DJ, Yancopoulos GD, Hall ZW. Laminin-induced acetylcholine receptor clustering: an alternative pathway. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:181–191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanaro F, Gee S, Jacobson C, Lindenbaum M, Froehner S, Carbonetto S. Laminin and alpha-dystroglycan mediate acetylcholine receptor aggregation via a MuSK-independent pathway. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1250–1260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01250.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel Z, Christian C, Vigny M, Bauer H, Sonderegger P, Daniels M. Laminin induces acetylcholine receptor aggregation on cultured myotubes and enhances the receptor aggregation activity of a neuronal factor. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1058–1068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-05-01058.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Jacobson C, Yurchenco P, Morris G, Carbonetto S. Laminin-induced clustering of dystroglycan on embryonic muscle cells: comparison with agrin-induced clustering. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1047–1058. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam M, Noakes PG, Moscoso L, Rupp F, Scheller RH, Merlie JP, Sanes JR. Defective Neuromuscular Synaptogenesis in Agrin-Deficient Mutant Mice. Cell. 1996;85:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel DD, Lee L, Stollberg J. Ultrastructure of Acetylcholine Receptor Aggregates Parallels Mechanisms of Aggregation. BMC Neuroscience. 2001;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R, Brown JC. The laminins. Matrix Biol. 1994;14:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0945-053X(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JR, Engvall E, Butkowski R, Hunter DD. Molecular heterogeneity of basal laminae: isoforms of laminin and collagen IV at the neuromuscular junction and elsewhere. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1685–1699. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckenbill-Edds L. Laminin and the mechanism of neuronal outgrowth. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;23:1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(96)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engvall E, Earwicker D, Haaparanta T, Ruoslahti E, Sanes JR. Distribution and isolation of four laminin variants; tissue restricted distribution of heterotrimers assembled from five different subunits. Cell Regul. 1990;1:731–740. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.10.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzer AJ, Brandenberger R, Gesemann M, Chiquet M, Ruegg MA. Agrin binds to the nerve-muscle basal lamina via laminin. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:671–683. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitkin RM, Rothschild TC. Agrin-induced reorganization of extracellular matrix components on cultured myotubes: relationship to AChR aggregation. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1161–1170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels MP, Vigny M, Sonderegger P, Bauer H-C, Vogel Z. Association of laminin and other basement membrane components with regions of high acetylcholine receptor density on cultured myotubes. Int J Devl Neuroscience. 1984;2:87–99. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(84)90063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayne EK, Anderson MJ, Fambrough DM. Extracellular matrix organization in developing muscle: correlation with acetylcholine receptor aggregates. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:1486–1501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.4.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemler ME. Dystroglycan versatility. Cell. 1999;97:543–546. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry MD, Campbell KP. Dystroglycan inside and out [In Process Citation]. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:602–607. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady RM, Zhou H, Cunningham JM, Henry MD, Campbell KP, Sanes JR. Maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular synapse: genetic evidence for roles of the dystrophin – glycoprotein complex. Neuron. 2000;25:279–293. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80894-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng HB, Ali AA, Daggett DF, Rauvala H, Hassell JR, Smalheiser NR. The relationship between perlecan and dystroglycan and its implication in the formation of the neuromuscular junction. Cell Adhes Commun. 1998;5:475–489. doi: 10.3109/15419069809005605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MW, Jacobson C, Godfrey EW, Campbell KP, Carbonetto S. Distribution of alpha-dystroglycan during embryonic nerve-muscle synaptogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1093–1101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.4.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee SH, Montanaro F, Lindenbaum MH, Carbonetto S. Dystroglycan-α, a Dystrophin-Associated Glycoprotein, is a Functional Agrin Receptor. Cell. 1994;77:675–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanaro F, Lindenbaum M, Carbonetto S. alpha-Dystroglycan is a laminin receptor involved in extracellular matrix assembly on myotubes and muscle cell viability. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1325–1340. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato H, Winkelmann DA, Yurchenco PD. Laminin polymerization induces a receptor-cytoskeleton network. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:619–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson C, Cote PD, Rossi SG, Rotundo RL, Carbonetto S. The dystroglycan complex is necessary for stabilization of acetylcholine receptor clusters at neuromuscular junctions and formation of the synaptic basement membrane. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:435–450. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin DJ, Kim JE, Gu M, Kaufman SJ. Laminin and alpha7beta1 integrin regulate agrin-induced clustering of acetylcholine receptors. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2877–2886. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.16.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowe MA, Fallon JRF. The Role of Agrin in Synapse formation. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1995; 18:443–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.18.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama J, Bowen DC, Hall ZW. Dystroglycan binds nerve and muscle agrin. Neuron. 1994;13:103–115. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanelli JT, Roberds SL, Campbell KP, Scheller RH. A role for dystrophin-associated glycoproteins and utrophin in agrin-induced AChR clustering. Cell. 1994;77:663–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollberg J, Fraser SE. Acetylcholine receptors and concanavalin A-binding sites on cultured Xenopus muscle cells: electrophoresis, diffusion, and aggregation. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1397–1408. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabrina F, Stollberg J. Common Molecular Mechanisms in Field- and Agrin-Induced Acetylcholine Receptor Clustering. Cell Molec Neurobiol. 1997;17:207–225. doi: 10.1023/A:1026365812496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]