Abstract

Global contractile heart failure was induced in turkey poults by furazolidone feeding (700 ppm). Abnormal calcium regulation appears to be a key factor in the pathophysiology of heart failure, but the cellular mechanisms contributing to changes in calcium fluxes have not been clearly defined. Isolated ventricular myocytes from non-failing and failing hearts were therefore used to determine whether the whole heart and ventricular muscle contractile dysfunctions were realized at the single cell level. Whole cell current- and voltage-clamp techniques were used to evaluate action potential configurations and L-type calcium currents, respectively. Intracellular calcium transients were evaluated in isolated myocytes with fura-2 and in isolated left ventricular muscles using aequorin. Action potential durations were prolonged in failing myocytes, which correspond to slowed cytosolic calcium clearing. Calcium current-voltage relationships were normal in failing myocytes; preliminary evidence suggests that depressed transient outward potassium currents contribute to prolonged action potential durations. The number of calcium channels (as measured by radioligand binding) were also similar in non-failing and failing hearts. Isolated ventricular muscles from failing hearts had enhanced inotropic responses, in a dose-dependent fashion, to a calcium channel agonist (Bay K 8644). These data suggest that changes in intracellular calcium mobilization kinetics and longer calcium-myofilament interaction may be able to compensate for contractile failure. We conclude that the relationship between calcium current density and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release is a dynamic process that may be altered in the setting of heart failure at higher contraction rates.

Keywords: Action potential, Calcium, Heart failure

Abbreviations: APD50(75) action potential duration at % repolarization, BW body weight; [Ca2+]o extracellular calcium concentration, [Ca2+]i intracellular calcium concentration, CON non-failing (control hearts), Fz furazolidone; HW heart weight, HW/BW heart weight/body weight ratio, ICa calcium current, I-V current-voltage, KA association constant, Kd dissociation constant, Lmax maximum peak force, OS overshoot, RMP resting membrane potential, SR sarcoplasmic reticulum, t80 time to 80% relaxation

Introduction

While previous work has established the presence of abnormalities in intracellular calcium handling and contractile response in heart failure, the cellular processes responsible for these abnormalities have not been identified and appear to vary among animal models and experimental conditions (Gwathmey et al. 1994). Numerous studies of two major determinants of systolic calcium levels [i.e., L-type calcium current and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium release] have resulted in discrepancies in the literature with regard to failing myocardium. In failing human myocardium, for example, calcium channel number as measured by dihydropyridine binding assays has been reported to be either decreased (Takahashi et al. 1992) or not changed (Gruver et al. 1994; Rasmussen et al. 1990). In animal models, calcium channel number has been reported to be either increased or decreased, depending on the “stage of disease” (Finkel et al. 1987; Gruver et al. 1993). Despite reported changes in calcium channel number in human heart failure, no changes in peak calcium currents have been reported (Beuckelmann et al. 1991,1992). Calcium currents have been reported to be normal in a model of hypertrophy, despite enhanced contractility (Shorofsky et al. 1996,1997). Therefore, the relationship of calcium channel number, as measured by dihydropyridine-binding assays, and or calcium current density to myocardial contractility remain controversial.

Peak systolic and diastolic calcium concentrations in models of heart failure have also varied (Gwathmey et al. 1994). In failing human myocardium, peak intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) has been reported to be either decreased (Beuckelmann et al. 1992) or not changed (D’Agnolo et al. 1992; Gwathmey et al. 1990). At higher frequencies of stimulation, a decrease in peak [Ca2+]i and an increase in diastolic calcium concentration have been reported (Pieske et al. 1995; Schmidt et al. 1998). Therefore, it would appear that measured peak calcium concentrations may vary depending on the physiological perturbation being studied.

Currently, the relationship of calcium current and the release of calcium by the SR, or “gain” of the system, have been implicated in the transition between normal contractility and increased contractility in the setting of compensated hypertrophy associated with hypertension (Shorofsky et al. 1996,1997). It is thought that early in hypertrophy, when contractility is increased, the gain is similarly increased (Gomez et al. 1997; Shorofsky et al. 1996,1997), Furthermore, it is hypothesized that with the transition to failure, the gain between these two cellular mediators of excitation-contraction is decreased (Gomez et al. 1997).

We have developed an animal model of heart failure that has been shown to reflect many of the functional as well as cellular changes observed in failing human myocardium (Hajjar et al. 1993). We define heart failure as reduced myocardial contractility with an increase in end-diastolic heart volume and biventricular dilatation. An advantage of this model is that development and subsequent outcome of heart failure is predictable and consistent. Our interest was to use this model to evaluate the relationship of Ca2+ regulation to that of contractile function and to compare our animal model to what has been reported in human heart-failure myocardium as well as mammalian animal models of heart failure. Therefore, we studied action potential configurations, calcium current, and intracellular calcium transients to better understand cellular mechanisms of heart failure and to further characterize our avian model of heart failure.

Materials and methods

Animal model

Twenty broad-breasted white turkey poults at 1 day of age were wing-banded for easy identification and were housed in heated brooders. Commercial starter mash and water were provided ad libitum. The investigation conformed to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996).

At 7 days of age, twenty poults were randomized into two groups. Furazolidone (Fz)-treated animals (n = 10) received 700 ppm Fz in their feed daily for 3 weeks in order to induce heart failure (Hajjar et al. 1993). Based on our experience with this model, by 4 weeks of age all of the animals given Fz develop heart enlargement with biventricular dilatation. At 4 weeks of age, the animals were euthanized and animal heart weights and body weights were obtained. Animals were randomly selected and the hearts harvested (five hearts per group) for isolated ventricular muscle studies and for cell isolation (n = 5 per group). The hearts were quickly excised and placed in ice-cold oxygenated physiologic salt solution for isolated myocytes or in oxygenated physiologic salt solution at 37 °C for isolated muscle studies. For isolated muscle studies, we used a Kreb’s solution with the following composition (mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 20 NaHCO3, 2 MgCl2, 11 glucose, 2.5 CaCl2, pH 7.4 (95% O2–% CO2). One muscle per heart (n = 5 per group) was studied and a second muscle per heart was loaded with aequorin (n = 5 per group). Portions of the left ventricle were freeze-clamped for later radioligand binding assays.

Myocyte isolation

We have tried without success to digest minced pieces of the heart in order to obtain viable cells (unpublished data). In this study for cell isolation, the heart was perfused retrograde through the aorta on a Langendorff perfusion apparatus at 41 °C and constant hydrostatic pressure of 100 mmHg as previously described (Gwathmey et al. 1991). Briefly, hearts were continuously perfused until stable (about 20 min) and then the perfusate was switched to a calcium-free Tyrode’s solution. After the heart ceased contracting (~5 min) it was then perfused with a calcium-free Tyrode’s solution containing type II collagenase for 20 min. The heart was then removed and the ventricles isolated and minced for further digestion with collagenase. Cells were spun at a low speed for 2 min, washed in collagenase free solution and the supernatant discarded. Isolated cells were stored in Tyrode’s solution containing 2 mM Ca2+ at room temperature. Cells were selected for study based on the appearance of normal striations, absence of spontaneous contraction, and elongated appearance in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+. The composition of the Tyrode’s solution used in these experiments was as follows (mM): 135 NaCl, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.33 Na2HPO4, 2 Ca2+. pH 73. Tyrode’s solution was not oxygenated for single cell studies because the oxygen content and tissue diffusion has been found to be sufficient for single cells and cell isolation. Cell length and width were measured with a linear ocular grid. Cell diameter was taken at the level of the centrally located nucleus in the mid-region of the myocyte.

Electrophysiological measurements

Whole cell calcium currents (ICa) were recorded from isolated myocytes from control and failing hearts using standard whole cell voltage clamp techniques, as previously described (Ellingsen et al. 1993). Pipettes were made from borosilicate glass (WP Instruments) with a filled tip resistance of 3–5 MΩ. Membrane voltages were computer software controlled (pClamp, Axon Instruments) and whole cell currents were amplified and then filtered at 5 kHz (Axopatch 1-C amplifier, Axon Instruments). Currents were then stored on the computer for later analysis. Whole cell currents were initially recorded during superfusion with a modified Tyrode’s solution containing (mM): 135 NaCl, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH at room temperature. No oxygenation was used because oxygen content and diffusion is sufficient for isolated myocyte studies. After establishing whole cell configuration and adjusting for series resistance, current stability was assessed by a double-pulse protocol, in which membrane voltage was stepped from a holding potential of −80 mV to −40 mV for 50 ms, and then to 0 mV for 50 ms. These voltages were chosen to selectively activate Na+ currents and ICa, respectively. When holding current and ionic currents were stable, a Na+-free/K+-free solution was applied through a multi-barrelled pipette placed within 300 μm of the cell, which permitted rapid changes of extracellular solution. Unless otherwise stated, this extracellular solution contained (mM): 135 choline-Cl, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, pH 7.4, adjusted with CsOH (Tseng and Boyden 1991). Cells were Internally dialyzed with a pipette solution designed to block outward K+-currents and to maintain low intracellular Cl− concentration (mM): 120 Cs-aspartate, 10 Cs2-EGTA, 4 MgATP, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2, adjusted with CsOH (Sen et al. 1990). It was determined that choline did not exert cholinergic effects since superfusing a subset of cells with 135 mM TEA (in lieu of choline) did not alter ICa.

Inward currents were activated by altering the membrane voltage, from an holding potential of −80 mV to +40 mV in 10 mV steps, with an interpulse interval of 10 s. It was determined that Ca2+ was the predominant charge carrier through the L-type Ca2+-channel based on the dependence of ICa on extracellular Ca2+, its sensitivity to both the L-type channel agonist Bay K 8644 (1 μM) and to cadmium (100 μM), and its insensitivity to tetrodotoxin (15 μM). To ascertain whether these cells possessed T-type Ca2+-currents, current-voltage (I-V) relationships were also recorded in some cells from an holding potential of −50 mV; the I-V curves were then subtracted from currents measured from an holding potential of −80 mV. No evidence for T-type currents was found. Measurements for leak current subtraction were routinely recorded with a small hyperpolarizing step (−10 mV from holding potential) following each voltage step protocol and leak subtraction was done post hoc. Data from cells with a holding current greater than 5% of the peak current amplitude were excluded from the analyses because leak subtraction would substantially alter peak amplitude values. Cell size was estimated in two ways: linear dimensions and cell capacitance. Cell capacitance (an index used to normalize current for cell size) was estimated by integrating the capacitance transient and dividing by the voltage step (−80 mV to −90 mV).

Intracellular calcium determination and cell shortening

A SPEX CM2 dual excitation spectrofluorometer (SPEX Industries, Edison, N.J.) was used to assess intracellular Ca2+ fluorescence in myocytes isolated from control animals (n = 5 hearts) and animals with heart failure (n = 5 hearts). Myocytes were loaded with fura-2/AM (molecular probes) by incubating cells plated on individual coverslips in a 3-μM fura-2 solution for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. The fura-2 loading solution was made from a 1-mM stock solution dissolved in DMSO and suspended by sonication in a superfusion buffer containing 0.2% BSA. Coverslips with myocytes attached were placed in a light-sealed, heated (37 °C) chamber mounted on a Nikon diaphot inverted microscope and superfused with a HEPES-buffered solution at a rate of 20 ml/h. Cells were washed with the modified Tyrode’s solution (see above) and allowed to equilibrate for at least 15 min prior to recording fluorescence emissions (505 nm) elicited from alternating excitation wavelengths (340 nm and 380 nm). Field stimulation was used to induce cells to contract. A single cell was illuminated with light through a red filter, and cell shortening/re-lengthening was assessed by video-optical detection. Photon counts were collected every 5 ms. One cell from each heart was studied after loading with fura-2 AM.

Action potential measurements

Action potentials were recorded from isolated ventricular myocytes (Ellingsen et al. 1993). The myocytes were placed in a 1-ml perfusion chamber and mounted on an inverted microscope. The chamber and superfusion solution (physiological Tyrode’s solution, see above) were maintained at room temperature. Action potentials were recorded in a whole cell configuration (current clamp mode) after internally dialyzing myocytes with a K+-asparate solution with the following composition (mM): 120 K+-asparate. 30 KCl, 5 NaCl, 4 MgATP, 10 HEPES, 0.2 EGTA, pH 7.2, adjusted with KOH. Initially, current injection was used to stabilize the membrane potential. After switching off the holding current, a brief (5 ms) depolarizing pulse (1 nA) was used to elicit an action potential at various frequencies. Membrane potentials were recorded with an Axopatch amplifier and digitized recordings were stored (pCLAMP) for later off-line analysis. Resting membrane potential (RMP), overshoot (OS), and action potential duration at 50% (APD50) and at 75% (APD75) repolarization were determined.

Isolated muscle

Isolated muscles were dissected free from the left ventricle of hearts from control animals (n = 5) and animals with heart failure (n = 5) (Hajjar et al. 1993). One muscle was studied using an organ bath technique and the second muscle was loaded with the intracellular calcium indicator aequorin. The muscles were attached at one end to a force transducer while the other end was attached to a small muscle clamp and placed in a muscle bath. The muscle was continuously superfused with oxygenated Kreb’s solution. The bath volume was 25 ml, which was replaced hourly. Muscles were stimulated to contract at 1 Hz via a punctate electrode located at the base of the muscle which delivered a square wave pulse of 5 ms duration at threshold voltage. The preparation was allowed to equilibrate for 1 h during which time the muscle was stretched in small increments with a micromanipulator until no further increase in peak twitch force was observed (Lmax). Experiments were performed at 37 °C using a standard Kreb’s solution (see above). Time course was measured from peak isometric twitch force to 80% relaxation, and the total time course was taken from initiation of contraction to the return to baseline. Bay K 8644 concentration-response relationships were determined by cumulatively adding increasing concentrations to a fixed bath volume. All force and time course measurements were made at steady-state. The means ± SEM were derived and the Student’s t-test applied. Parametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures was used to compare concentration response studies.

Intracellular calcium determination in multicellular preparations

Isolated muscle preparations were handled as previously described (Hajjar et al. 1993). The bioluminescence calcium indicator aequorin was loaded in isolated muscles from the left ventricle of control and failing hearts, as previously described (Pesaturo and Gwathmey 1990). Briefly, isolated muscles were placed in a calcium-free solution at 20 °C and then loaded by macro-injection with aequorin. Calcium was then slowly re-added to the bath and the temperature was slowly returned to 37 °C. Muscles used in aequorin experiments were from the same hearts as muscles used for isolated muscle organ bath studies (n = 5 per experimental group).

Radioligand binding

Dihydropyridine-DHP binding studies were carried out as described previously (Chapados et al. 1992; Davidoff et al. 1997; Gruver et al. 1993; Ogawa et al. 1992; Scatchard 1949). A crude ventricular homogenate was placed into ice-cold buffer containing (mM); 50 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 1 EDTA, pH 7.4. The buffer also contained protease inhibitors: 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.1 mM benzamidine, 1 μM iodoacetamide, 10 μg/ml trypsin inhibitor, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin. Cells were then disrupted with an ice-cold sonicator (2 × 30 s), resulting in an homogenate that was suspended in the same ice-cold buffer, and 3H-(+)PN200-110 (isradipine 8 concentrations in the range of 100–3500 pM) was carried out in the presence or absence of 10−6 M unlabeled nitrendipine at 37 °C for 30 min. Binding was terminated by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/B filters using a Brandell cell harvester. Bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry (LKB Wallac). The ligand-binding data were analyzed by a modification of LIGAND program with a Micro-VAX computer as previously described (Marsh and Smith 1985). Nonspecific biding was < 15% of total binding near the dihydropyridine dissociation constant (Kd) (Chapados et al. 1992; Gruver et al. 1993). Nonspecific binding was defined with unlabeled 1 × 10−6 M nitrendipine (Chapados et al. 1992; Graver et al. 1993). Protein determination was by the Lowry method (Lowry et al. 1991).

Chemicals

Type 2 collagenase (for myocyte isolation) was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Freehold, N.J.), and fura-2/AM from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Ore.). PN200-110 and nitrendipine were generously supplied by Dr. James Marsh, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan. Bay K 8644 and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, Mo.) and were of the highest analytical grade.

Statistical analysis

Ten animals were included in each group (control and Fz-treated). At the time of study five animals from each group were randomly selected for study using the isolated myocyte technique. Cell shortening and intracellular calcium transients were recorded in one cell from each heart. The remaining five animals in each group were used for isolated muscle studies and radioligand binding assays. Two muscles were dissected free from each heart. One muscle was studied using standard muscle bath techniques and the second muscle was studied using the aequorin technique. Data from five muscles in each group were pooled. Data from isolated myocyte studies were pooled by group (control vs. failing). A mean ± SEM was derived and the Student’s t-test applied. For small sample sizes comparisons between two groups were made using a non-parametric t-test (Wilcoxin Rank Sum). For the current voltage relationships only peak calcium currents were evaluated. The distributions of the continuous variables were checked for normality and ANOVA with repeated measures was applied to dose response relationships. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the heart weights (HW), body weights (BW), and heart weight/body weight (HW/BW) ratio for non-failing (n = 5) and failing hearts (n = 5) used for isolated myocyte studies. There was a significant increase in HW for animals with heart failure compared to control animals. There was a significant decrease in BW and an increase in the HW/BW ratio. Similar changes were seen in these parameters in hearts used for isolated muscle and radioligand binding studies (data not shown). The cell width was significantly greater in myocytes isolated from failing ventricular myocardium without changes in cell length (Table 2). There was a tendency toward increased cell capacitance and shortened length in myocytes from failing hearts, but these parameters did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.071).

Table 1.

Body weights and heart weights for control and failing myocardium. BW body weight, CON control, HF heart failure (turkeys fed furazolidone), HW heart weight, HW/BW heart weight/body weight ratio. Data are presented as mean ± SEM

| CON (n = 5) | HF (n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|

| HW (g) | 3.44 ±0.15 | 4.45 ± 0.20* |

| BW (g) | 620 ± 34 | 348 ± 23* |

| HW/BW | 0.005 ± 0.0004 | 0.013 ± 0.0009* |

P ≤ 0.005, significantly different from control

Table 2.

Cell dimensions from control and failing hearts. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n is number of cells studied

| n | Cell capacitance (pF) | Cell length (μm) | Cell width (μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 27 | 25.9 ± 0.6 | 136 ± 5 | 8.7 ± 0.3 |

| HF | 24 | 28.0 ± 1.0 | 124 ± 4 | 9.7 ± 0.3* |

P = 0.02

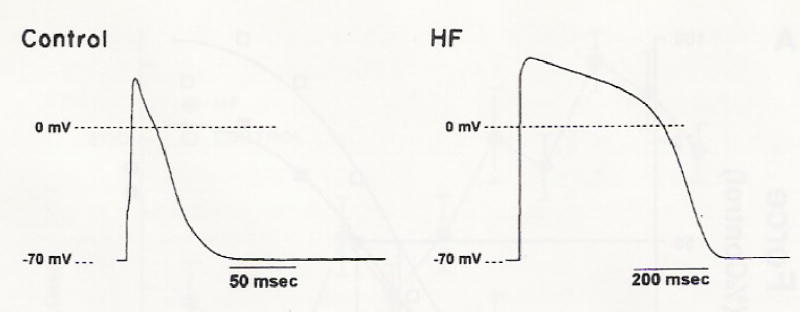

We first addressed the question whether ventricular myocytes from turkey myocardium demonstrated similar action potential configurations as seen in mammalian species. Figure 1 illustrates representative action potentials from control and failing turkey hearts. Similar to other reports in hypertrophied or failing mammalian myocardium, human and non-human, APD50 and APD75 were significantly longer in myocytes from failing ventricular myocardium compared to control myocardium, but the overshoot of the action potential was also significantly higher in myocytes from failing hearts (Table 3). There was no difference in resting membrane potential between myocytes from non-failing and failing hearts (Table 3). Preliminary data suggest that prolonged action potentials in myocytes from failing hearts may be related to depressed outward potassium currents because after recording action potentials, the whole cell configuration was switched to a voltage step protocol and the outward current was measured. With increasing frequency of stimulation, the action potential duration in myocytes from failed hearts became unstable and never reached steady-state (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Action potentials recorded from isolated ventricular myocytes from a control and failing heart (HF). Stimulation frequency 0.1 Hz at room temperature

Table 3.

Action potentials from control and failing ventricular myocardium. (APD50 action potential duration at 50% repolarization, APD75 action potential duration at 75% repolarization, OS overshoot, RMP resting membrane potential). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Control, n = 4; heart failure, n = 3

| RMP (mV) | OS (mV) | APD50 (ms) | APD75 (ms) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | −70.5 ± 1.55 | 28 ± 1 | 14 ± 4 | 21 ± 5 |

| HF | −70.33 ± 1.15 | 39 ± 2* | 461 ± 56* | 488 ± 54* |

P < 0.05, significantly different from control

Failing myocardium has been reported to have a longer duration of contraction and relaxation and a negative force-interval relationship in multicellular preparations (Gwathmey et al. 1990; Hajjar et al. 1993; Hasenfuss et al. 1994; Mulieri et al. 1992; Pieske et al. 1995; Schmidt et al. 1998; Schwinger et al. 1995). Peak twitch force in isolated muscle preparations was also not different between non-failing and failing muscle preparations at 1.0 Hz stimulation rate [1.8 ± 0.4 g/mm2 and 2.1 ± 0.7 g/mm2 for non-failing (n = 10; five aequorin loaded and five non-aequorin loaded) and failing muscles (n = 10; five aequorin loaded and five non-aequorin loaded), respectively; Glass et al. 1993]. Isolated myocytes afforded us the opportunity to study cell shortening and time course changes in the absence of diffusional constraints, core-hypoxia, and the presence of an extracellular matrix. We used cell shortening in isolated myocytes as a surrogate marker for force production as it has been previously shown to correlate with findings in multicellular preparations (Hajjar et al. 1997a,b).

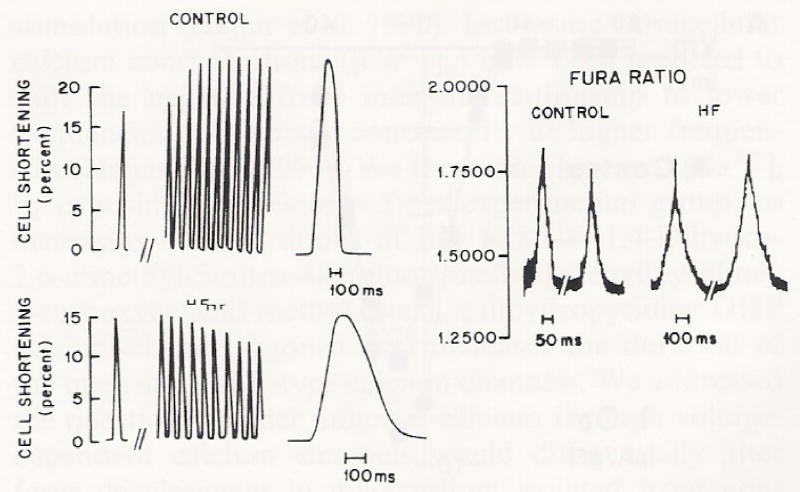

We increased the frequency of stimulation in isolated myocytes from non-failing and failing ventricular myocardium as demonstrated in Fig. 2. At lower stimulation rates, peak shortening was similar for myocytes isolated in non-failing (n = 5) and failing hearts (n = 5). Myocytes from non-failing ventricular myocardium (n = 5) demonstrated an increase in peak shortening with increased frequency of stimulation. Myocytes isolated from failing ventricular myocardium (n = 5) demonstrated a negative or blunted force-frequency relationship, in which higher frequencies of stimulation resulted in either a decreased peak shortening or no further increase in peak shortening. The time course of shortening and relaxation was prolonged in myocytes isolated from failing turkey hearts compared to myocytes isolated from non-failing myocardium (Fig. 2). The intracellular calcium transient was also prolonged in myocytes from failing hearts (Fig. 2). The effects of frequency perturbation on myocyte shortening were similar to our findings in multicellular preparations in our animal model of heart failure (Hajjar et al. 1993). We have previously reported that at higher stimulation rates, muscles from failing hearts demonstrated a negative force-interval relationship (Hajjar et al. 1993).

Fig. 2.

Cell shortening in isolated myocytes from control and failing avian hearts with increasing frequency of stimulation from 0.83 Hz to 1.0 Hz (left panel). Notice the positive force-frequency interval in the control myocyte as opposed to the negative force-frequency relationship seen from a myocyte from a failing heart. Right panel demonstrates two representative calcium transients from two myocytes from control and failing hearts stimulated at 1.0 Hz. Temperature = 37 °C. Figure produced by graphic artist

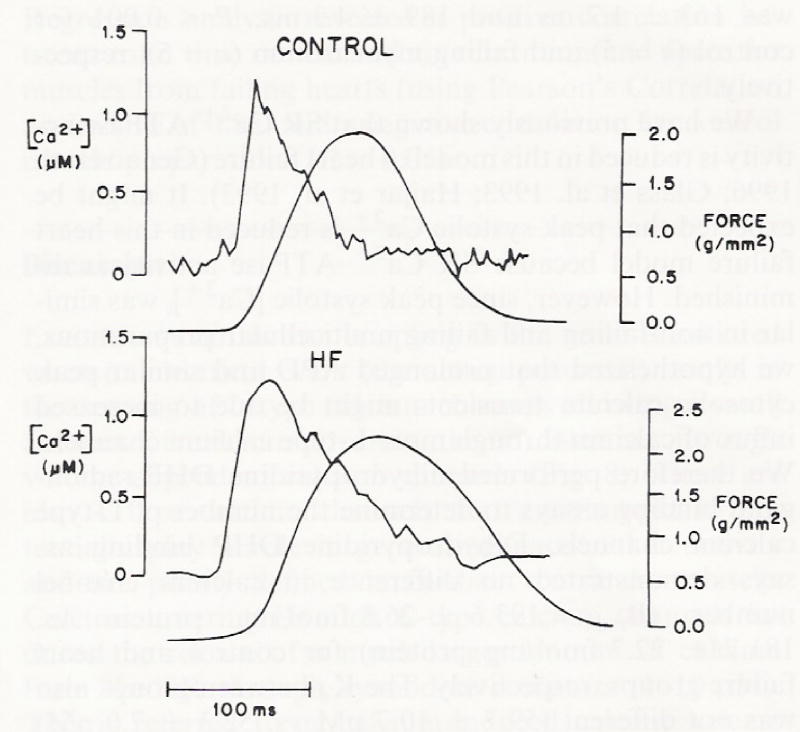

We next addressed whether there was a difference in peak [Ca2+]i as has been reported in several animal models of heart failure (Gwathmey et al. 1994). As illustrated in Fig. 3, peak [Ca2+]i (1.2 ± 0.1 μM) was similar in control and failing muscles (1.1 ± 0.2 μM) and within the normal ranges reported for other mammal species. Peak systolic Ca2+ appeared to be similar in non-failing and failing ventricular myocardium at 1.0 Hz stimulation rate, however, the time course of the calcium transient decay was prolonged in myocardium from failing hearts (Figs. 2,3). Time to 80% relaxation was 163 ± 1.7 ms and 189 ± 4.3 ms, P < 0.001 for control (n = 5) and failing myocardium (n = 5), respectively.

Fig. 3.

Intracellular calcium concentration measured with aequorin in multicellular preparations from a control and failing heart (figure produced by graphic artist). A representative calcium transient obtained with the intracellular bioluminescent calcium indicator aequorin. Upper noisy trace of each pair is the calcium transient; lower smooth trace is the isometric twitch. Temperature = 37 °C at 1.0 Hz stimulation rate

We have previously shown that SR Ca2+ ATPase activity is reduced in this model of heart failure (Genao et al. 1996; Glass et al. 1993; Hajjar et al. 1993). It might be expected that peak systolic Ca2+ is reduced in this heart failure model because SR Ca2+ ATPase activity is diminished. However, since peak systolic [Ca2+]i was similar in non-failing and failing multicellular preparations, we hypothesized that prolonged APD and similar peak cytosolic calcium transients might be due to increased influx of calcium through more L-type calcium channels. We therefore performed dihydropyridine DHP-radioligand binding assays to determine the number of L-type calcium channels. Dihydropyridine DHP binding assays demonstrated no difference in calcium channel number (Bmax = 193.6 ± 26.8 fmol/mg protein vs. 181.7 ± 22.7 fmol/mg protein) for control and heart failure groups, respectively. The Kd between groups also was not different (59.7 ± 10.7 pM vs. 52.3 ± 7.0 pM) for control and heart failure, respectively.

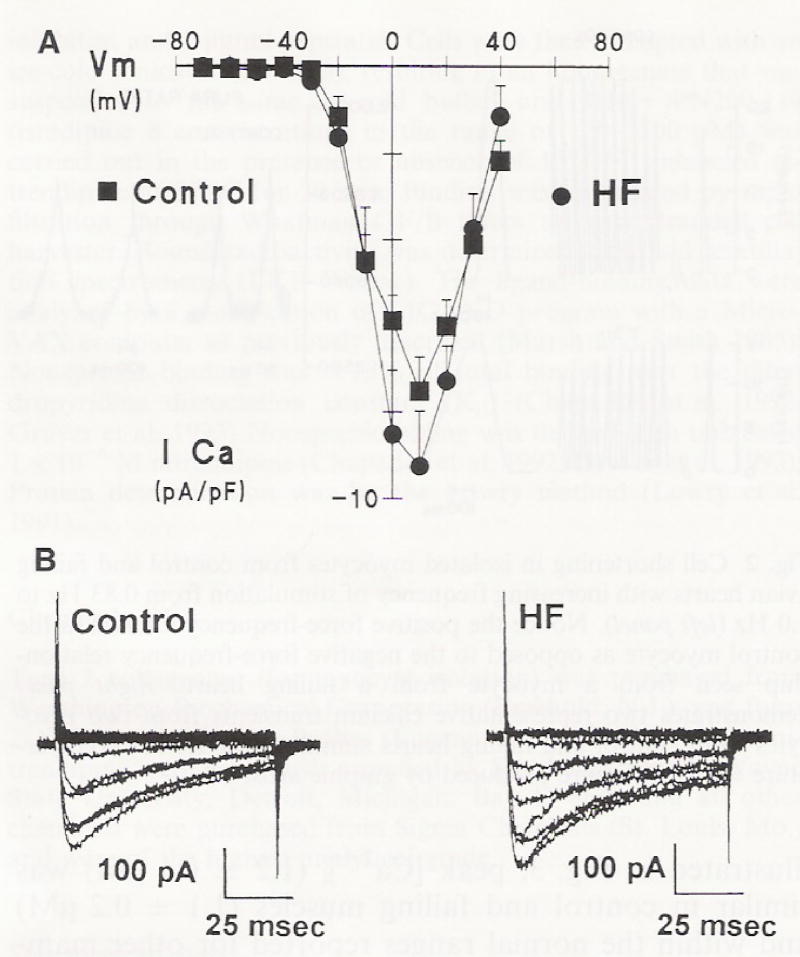

Although dihydropyridine DHP-binding is thought to reflect calcium channel density, it does not provide information on calcium channel function (Gruver et al. 1993). We therefore addressed whether the calcium current might be different between isolated myocytes from non-failing and failing ventricular myocardium and contribute to the larger action potential duration. As shown in Fig. 4A, the I-V relationship was not different for myocytes isolated from control and failing ventricular myocardium. Furthermore, the peak calcium current amplitude was not different between failing (−9.6 ± 1.4 pA/pF, n = 23) and non-failing (−7.52 ± 0.80 pA/pF, n = 27) myocytes (Fig 4B).

Fig. 4.

A The current-voltage relationship of whole cell calcium current (ICa) normalized to cell capacitance in myocytes isolated from control and failing hearts. B Traces of calcium currents from turkey myocytes. (Control myocytes isolated from non-failing hearts. HF heart failure). Data represent mean ± SEM from 23–27 cells/group

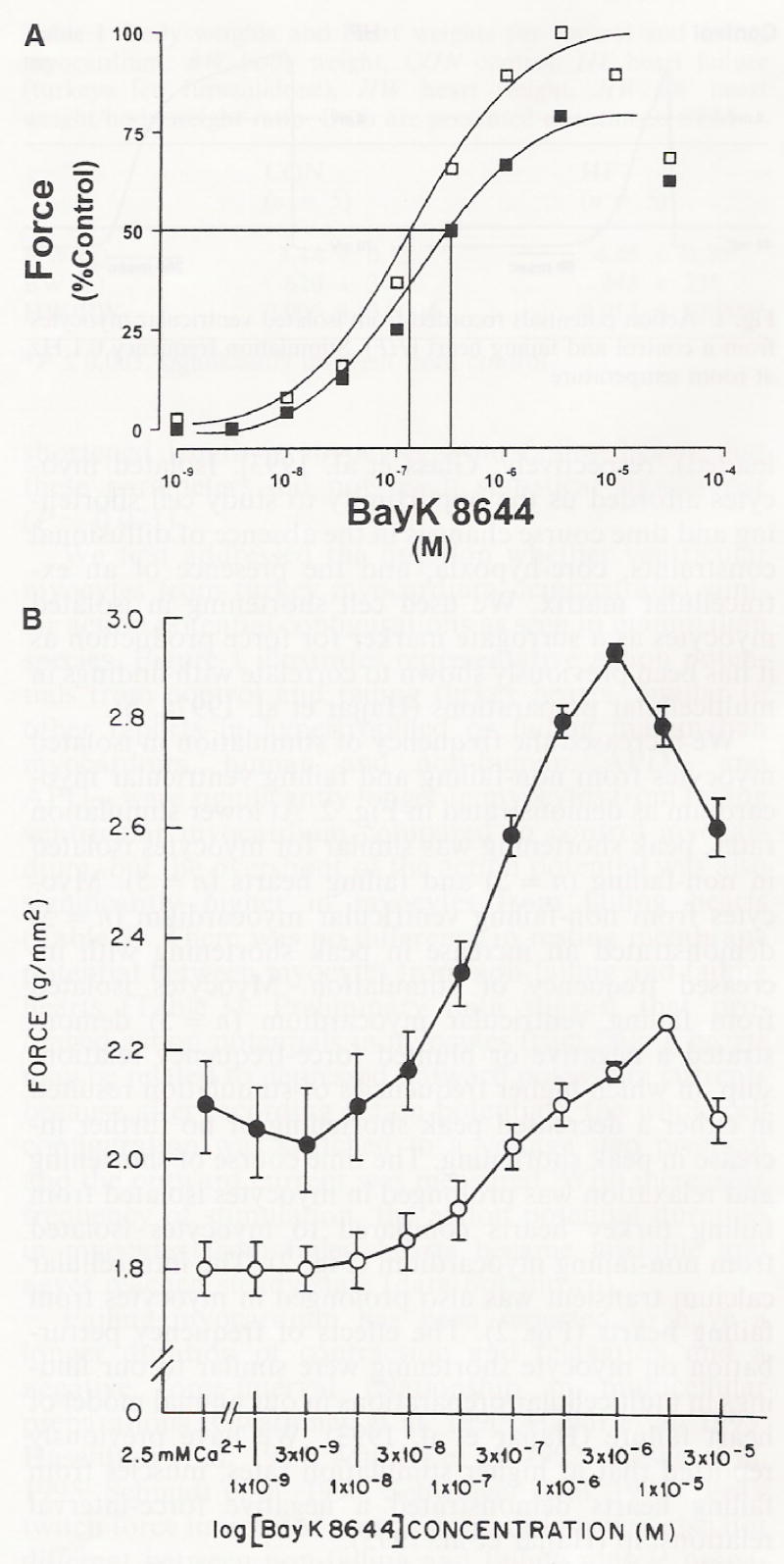

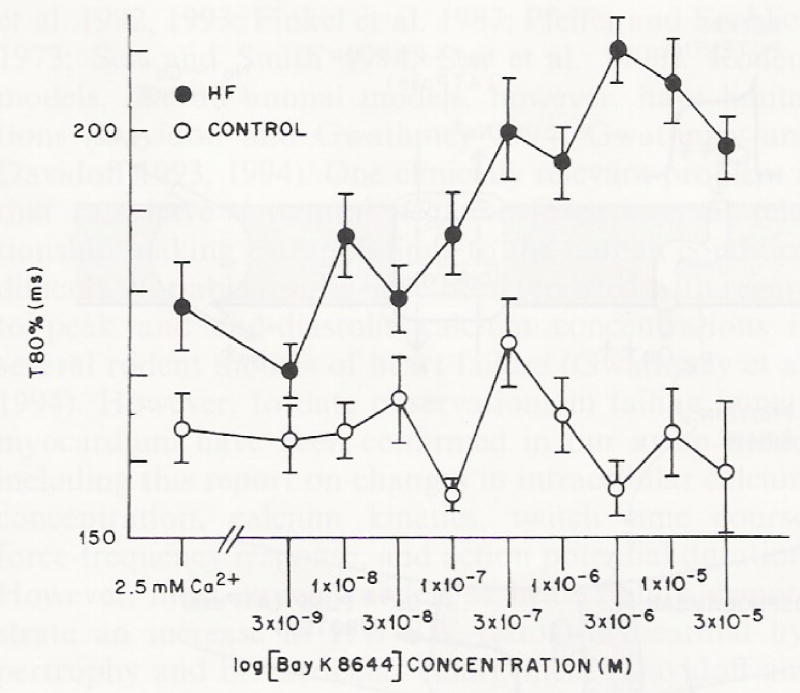

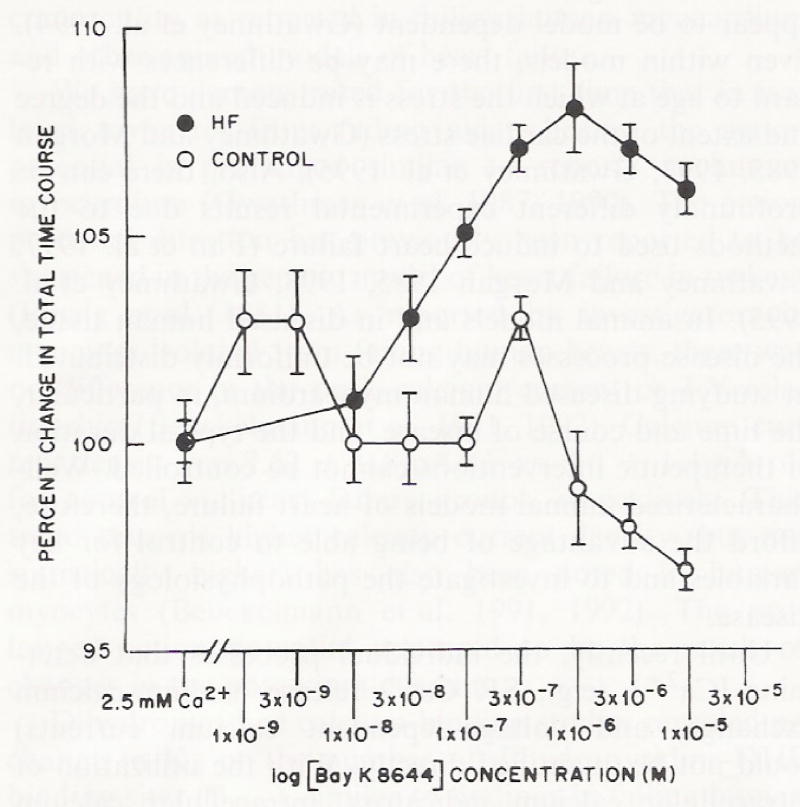

We have previously demonstrated that peak contractile force is similar for muscle preparations from non-failing and failing hearts at lower frequencies of stimulation (Hajjar et al. 1993). Increasing extracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]o) have been reported to shift the negative force interval relationship to lower frequencies and worsen contractility at higher frequencies (Hajjar et al. 1993). We therefore increased [Ca2+]i by exposing muscles (n = 5 per experimental group) to increasing concentrations of Bay K 8644 (1,4-Dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-4-[trifluoromethyl]phenyl]pyridine-3-carboxylic acid methyl ester), a dihydropyridine DHP calcium-channel agonist that increases the duration of the open state of L-type calcium channels. We addressed the question whether influx of calcium through voltage-dependent calcium channels would differentially alter force development in myocardium isolated from non-failing and failing hearts. As shown in Fig. 5, the concentration-response relationship was shifted to the left (i.e., lower Bay K 8644 concentration) for muscle strips isolated from failing ventricular myocardium. Bay K 8644 resulted in a 40 ± 2% increase in peak twitch force in myocardium from failing hearts and 25 ± 4% in control myocardium (P = 0.01).

Fig. 5.

A Dose response curve for the calcium channel agonist, Bay K 8644, as measured by percent change in force of contraction from control (no agonist). Open squares are muscles from failing hearts, closed squares are muscles from control hearts. B Bay K 8644 concentration-response relationship in muscles isolated from non-failing (n = 5) and failing hearts (n = 5)* Open circles are muscle strips from control non-failing hearts. Closed circles are muscle strips from failing hearts

In response to increasing concentrations of Bay K 8644, time to 80% relaxation (t80) did not change in muscle preparations isolated from non-failing ventricular myocardium (Fig. 6), nor did it affect the total time course of contraction in non-failing preparations (Fig. 7). In contrast to non-failing myocardium, t80 showed a dose-dependent increase with Bay K 8644 in failing ventricular myocardium (Fig. 6). As a result of a slowing of muscle relaxation, there was a significant increase in the total time course of contraction-relaxation in isolated muscles from failing hearts (Fig. 7). Regression analysis revealed a positive correlation between total time course and t80 relaxation and force for muscles from failing hearts (using Pearson’s Correlation an R value of 0.88) and a negative correlation for control muscle preparations (R = 0.05).

Fig. 6.

The effect of increasing concentrations of Bay K 8644 (starting at 3 × 10−9 M) on the time to 80% (t80) relaxation in multicellular preparations from control (n = 5) and failing hearts (n = 5). Open circles are multicellular preparations from control non-failing hearts; closed circles are multicellular preparations from failing hearts. Temperature = 37 °C, at 1.0 Hz stimulation rate

Fig. 7.

The effect of increasing concentrations of Bay K 8644 on the total time course in multicellular preparations from control (n = 5) mid failing hearts (n = 5). Open circles are multicellular preparations from control non-failing hearts; closed circles are multicellular preparations from failing hearts. Temperature = 37 °C, at 1.0 Hz stimulation rate

Discussion

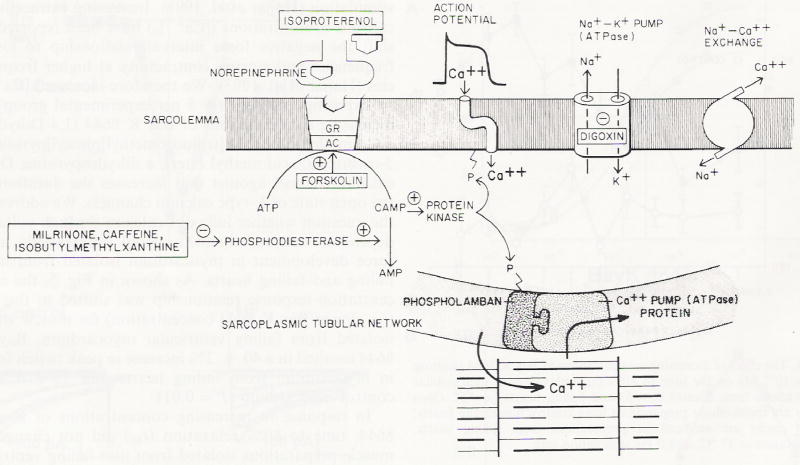

Excitation-contraction coupling in the heart is initiated when an electrical event (the action potential) results in the opening of L-type calcium channels allowing a small amount of calcium to cross the sarcolemma through voltage-dependent calcium channels (Fig. 8). There are also T type calcium channels that are thought to potentially play a role in generating pace-maker activity and are poorly defined in cardiac ventricular muscle. Calcium entering through L-type calcium channels induces the release of a much larger amount of calcium from the SR through ryanodine receptors (1–10 μM). This is referred to as calcium-induced calcium release and was first reported by Fabiato (1983). Although recently it has been demonstrated that ryanodine receptors may be clustered close to voltage-dependent calcium channels, calcium-induced calcium release is still thought to initiate muscle contraction (Gomez et al. 1997; Shorofsky et al. 1996,1997,1998a,b,1999). The large amount of calcium released from the SR quickly binds to troponin C, the calcium-binding regulatory protein on the thin myofilaments, inducing conformational changes in the regulatory thin filaments interacting with the thick myofilaments. This results in force production. Relaxation occurs when calcium dissociates from the myofilaments and is re-sequestered into the SR via the SR Ca2+ ATPase pump. The re-sequestered calcium is thought to require a restitution period before it is available for re-release (Gwathmey 1991). Resting levels of intracellular calcium are further restored by calcium extrusion via the sodium-calcium exchanger (low affinity but high capacity) and the sarcolemmal Ca2+ ATPase (high affinity but low capacity). An energy-requiring pump, the sodium-potassium ATPase, located in the sarcolemma maintains intracellular sodium homeostasis. Inhibition of the pump by digoxin, for example, results in sodium accumulation and activation of the sodium-calcium exchanger operating in a reverse mode with calcium being transported from the extracellular space into the cell. We studied the relationship of several key steps in the excitation-contraction coupling scheme (e.g., SR calcium release, SR Ca2+ ATPase activity, action potential duration, L-type calcium current) in order to better understand myocardial contractile activation in non-failing and failing avian myocardium.

Fig. 8.

Excitation-contraction coupling in the heart (see text for details). Receptor agonists shown are isoproterenol and norepinephrine (β-receptor agonists); forskolin which activates adenylate cyclase (AC); digoxin which inhibits sodium potassium ATPase; and Milrinone, caffeine, isobutylmethyxanthine which are phosphodiesterase inhibitors. (cAMP cyclic AMP). Reproduced with permission from Feldman et al. (1987)

Failing myocardium in many animal models and in human myocardium has been demonstrated to have changes in action potential durations, contraction/relaxation parameters, time courses of the calcium transient, and in the force-interval relationships (Gwathmey et al. 1994; Liao et al. 1996; Nascimben et al. 1996). However, changes in these characteristics of heart failure appear to be model dependent (Gwathmey et al. 1994). Even within models, there may be differences with regard to age at which the stress is induced and the degree and extent of the cardiac stress (Gwathmey and Morgan 1985,1993; Gwathmey et al. 1995). Also, there can be profoundly different experimental results due to the methods used to induce heart failure (Fan et al. 1997; Gwathmey and Morgan 1985,1993; Gwathmey et al. 1995). In animal models and in diseased human tissue, the disease processes may not be uniformly distributed. In studying diseased human myocardium, in particular, the time and course of disease, and the typical duration of therapeutic interventions cannot be controlled. Well-characterized animal models of heart failure, therefore, afford the advantage of being able to control for key variables and to investigate the pathophysiology of the disease.

Until recently, the individual processes that determine [Ca2+]i (e.g., SR Ca2+ release, sodium-calcium exchange, and voltage-dependent calcium currents) could not be quantified directly. With the utilization of intracellular calcium indicators, intracellular calcium transients can be recorded in multicellular preparations and in isolated myocytes. The spontaneously hypertensive rat model and Syrian hamster model have been extensively investigated with regard to [Ca2+]i handling (Bing et al. 1988; Brooks et al. 1994,1997; Brooksby et al. 1992, 1993; Finkel et al. 1987; Pfeffer and Frohlich 1973; Sen and Smith 1994; Sen et al. 1990). Rodent models, like all animal models, however, have limitations (Davidoff and Gwathmey 1994; Gwathmey and Davidoff 1993,1994). One clinically relevant problem is that rats have a natural negative force interval relationship making extrapolations to the human condition difficult. Variable results have been reported with regard to peak and end-diastolic calcium concentrations in several rodent models of heart failure (Gwathmey et al. 1994). However, to date observations in failing human myocardium have been confirmed in our avian model including this report on changes in intracellular calcium concentration, calcium kinetics, twitch time course, force-frequency response, and action potential duration. However, most animal models of heart failure demonstrate an increase in HW/BW ratios, myocardial hypertrophy and biventricular enlargement (Davidoff and Gwathmey 1994; Gwathmey and Davidoff 1993,1994).

We have developed an avian model of heart failure that appears to mimic the condition seen in human myocardium at the biochemical and functional levels (Hajjar et al. 1993). We have demonstrated in our model that there is biventricular dilatation, an increase in HW/BW ratio, and overt heart failure. There is also an increase in the circulating levels of catecholamines, and decreased myofibrillar ATPase activity, myocardial energetics, and SR Ca2+ ATPase activity (Glass et al. 1993; Gwathmey et al. 1999; Hajjar et al. 1993). We therefore wanted to know whether this model presented with changes in the action potential duration, calcium current, and peak [Ca2+]i that would impact myocardial contractility as reported in failing human myocardium and other animal models of heart failure.

We have demonstrated for the first time that in isolated myocytes from failing avian hearts, the action potential is prolonged similar to reports in human myocardium (Gwathmey et al. 1987,1990). The action potential duration has previously been reported to be shortened in the genetic model of heart failure in turkeys (Einzig et al. 1981). As reported by investigators in myocytes isolated from failing human hearts, there was no difference in the peak calcium current or I–V relationship (Beuckelmann et al. 1991,1992). Calcium current density was 7.52 ± 0.8 pA/pF vs. 9.6 ± 1.4 pA/pF for control vs. heart failure groups, respectively. This trend towards higher calcium current density (but not statistically higher) has also been noted in human myocytes (Beuckelmann et al. 1991,1992). The prolonged action potential appeared to be the result of changes in the potassium current.

Dihydropyridine calcium-binding studies revealed no change in Kd or the number of dihydropyridine-DHP binding sites (Bmax), similar to findings in failing human myocardium (Gruver et al. 1994; Rasmussen et al. 1990). In our study, the number of dihydropyridine-DHP binding sites has been taken as a surrogate measure of the number of functional calcium channels. It may identify nascent calcium channels as well as functional calcium channels in the sarcolemmal membrane (Marsh and Smith 1991). Therefore, differences in APD seen in this model of heart failure most likely reflect other cellular events such as changes in the outward K+ current or prolonged calcium influx through the sodium-calcium exchanger. Alternatively, there may be differences in intracellular regulation of calcium currents (e.g., extent of phosphorylation). We utilized a whole cell (dialyzed) configuration in order to ascertain maximal available calcium currents, however, using a perforated patch clamp method may reveal differences between non-failing and failing myocytes. We have previously shown that changes in the differences in contractile activation in an avian model of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy cannot be directly attributed to calcium channel number (Gruver et al. 1993). In this model, there appears to be a complex relationship between calcium channel number and contractile dysfunction (Gruver et al. 1993).

Differences in contractile activation, i.e., slower time courses, in failing ventricular myocardium seen in turkey poults were associated with prolonged action potential durations and a slower time course of the intracellular calcium transients. A slower rate of SR Ca2+ uptake and/or decrease in sodium-calcium exchange could explain the prolonged twitch and intracellular calcium transient. Furthermore, prolongation in action potential duration alone could account for longer twitches and calcium transients. We have previously shown that SR Ca2+ ATPase activity is significantly reduced in myocardium from animals with heart failure (Glass et al. 1993; Hajjar et al. 1993). We have not, to date, studied the sodium-calcium exchange activity in these hearts. In a recent report in human myocardium, sodium-calcium exchange activity has been implicated in the prolongation of the calcium transient seen in human heart failure (Dipla et al. 1999), as well as in other animal models (O’Rourke et al. 1999; Winslow et al. 1999).

A dissociation between calcium current and SR Ca2+ release has recently been suggested (Gomez et al. 1997). The current hypothesis by which excitation is coupled to contractility in the heart involves calcium-induced calcium release and the gain between calcium current density and ryanodine receptors (Fabiato 1983). The observation that calcium entry through L-type calcium channels appears to be a major trigger for SR calcium release invokes several important questions in the setting of heart failure. Recent data suggests that SR calcium release is controlled by events localized to the voltage-dependent calcium current and SR calcium-release channel (ryanodine receptors). It has been suggested that the whole-cell L-type calcium current and whole-cell calcium transient may be sensitive to calcium entry and [Ca2+]i at the clustering of L-type calcium channels and ryanodine receptors (Gomez et al. 1997; Shorofsky et al. 1996,1997,1998b).

We found that Bay K 8644 (which prolongs the open state of calcium channels) results in greater force development in ventricular strips from failing hearts (40 ± 2% increase in force in muscle from failing hearts as compared to 25 ± 4% increase in control myocardium). The leftward shift on the Bay K 8644 concentration axis would suggest an increase in calcium current density and/or increase in the number of calcium channels. However, the peak calcium current density was the same between failing and non-failing myocardium and the number of calcium channels (as determined by radioligand binding studies) was not changed. This leftward shift in response to Bay K 8644 most likely reflects enhanced contractile activation as a result of longer durations for calcium-myofilament interactions (Gwathmey and Hajjar 1990; Perez et al. 1999; Schmidt et al. 1998; Yue 1987; Yue and Wier 1985; Yue et al. 1986), perhaps resulting from prolonged SR Ca2+ release. This would be consistent with the observations that Bay K 8644 enhances contractile force and prolongs relaxation in avian failing myocardium. This hypothesis is supported by the slowed contraction–relaxation time courses seen only in the failing ventricular myocardium, as well as, prolonged t80 in a concentration-dependent manner to Bay K 8644.

We found that peak systolic [Ca2+]i is similar for non-failing and failing myocardium when peak twitch force is the same (i.e., at lower frequencies of stimulation). It is only at higher stimulus frequencies that depressed myocardial contractility is observed and peak intracellular calcium concentration is reduced in the presence of elevated diastolic calcium concentrations (Schmidt et al. 1998). We have also shown that at higher stimulus frequencies with failing human myocardium, there is progressive abbreviation in APD as opposed to the abbreviation seen in non-failing myocardium that stabilizes at a set frequency and APD (Gwathmey et al. 1988). Similarly, we found that APD was dynamically changed in response to stimulus frequency perturbation in failed avian myocardium, such that APD did not reach steady-state at higher frequencies. We therefore propose that the gain between calcium current and SR calcium release can be modified by physiological stresses, e.g., frequency perturbations, and therefore might be dynamically altered (Gwathmey et al. 1990,1995). Therefore, the hypothesis of changes in gain between the two parameters as being fixed and being involved in the transition to heart failure may have to be rethought in light of the observations in our animal model and human heart failure where contractile failure is a dynamic process.

In conclusion, as reported in failing human hearts and in several other mammalian models of heart failure, there is prolongation of the intracellular calcium transient and action potential duration due to depressed transient outward potassium currents in this avian model. Also similar to reports in failing human myocardium, there is no difference in the current-voltage relationship of the calcium current or peak [Ca2+]i at lower stimulation rates. Furthermore, the negative force-interval relationship reported in multicellular preparations can be demonstrated in isolated myocytes (Hajjar et al. 1993), again similar to studies in human myocardium.

Normal levels of peak calcium current in the setting of prolonged action potential durations in failing myocardium could potentiate SR Ca2+ release and generate greater contractile forces because of slowed [Ca2+]i mobilization. Whether there is a difference in the gain between calcium channels and the ryanodine receptors that dynamically alters SR Ca2+ release in the setting of heart failure, remains to be the determined.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere appreciation for the assistance and patience of Mr. Alvin Brass, a graphic artist, at Visual Communications, Brookline MA. We would also like to thank GwI, Cambridge, MA for assistance in animal housing and model development. This work was supported by grants 2RO1-HL49574, R43-H52249 and R44-H52249 to JKG. The experiments performed comply with current United States laws.

Contributor Information

J. K. Gwathmey, Whitaker Cardiovascular Research Institute, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02115

A. J. Davidoff, University of New England School of Osteopathic Medicine, Department of Pharmacology, Biddeford, ME 04005

T. M. Maki, Clinical Laboratory of Jorvi Hospital, Espoo, Finland

References

- Beuckelmann DJ, Nabauer M, Erdmann E. Characteristics of calcium-current in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23:926–937. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuckelmann DJ, Nabauer M, Erdmann E. Intracellular calcium handling in isolated ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circulation. 1992;85:1046–1055. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.3.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing OHL, Wiegner AW, Brooks WW, Fishbein MC, Pfeffer JM. Papillary muscle structure-function relations in the aging spontaneously hypertensive rat. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1988;10:37–58. doi: 10.3109/10641968809046798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks WW, Bing OHL, Litwin SE, Conrad CH, Morgan JP. Effects of treppe and calcium on intracellular calcium and function in the failing heart from the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 1994;24:347–356. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.24.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks WW, Bing OHL, Conrad CH, O’Neill L, Crow MT, Lakatta EG, Dostal DE, Baker KM, Boluyt MO. Captopril modifies gene expression in hypertrophied and failing hearts of ages spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1997;30:1362–1368. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooksby P, Levi AJ, Jones JV. Contractile properties of ventricular myocytes isolated from spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Hypertens. 1992;10:521–527. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooksby P, Levi AJ, Jones JV. Investigation of the mechanisms underlying the increased contraction of hypertrophied ventricular myocytes isolated from the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1268–1277. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.7.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapados RA, Gruver EJ, Ingwall JS, Marsh JD, Gwathmey JK. Chronic administration of cardiovascular drugs: altered energetics and transmembrane signaling. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1576–H1586. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.5.H1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agnolo A, Luciani GB, Mazzucco A, Gallucci V, Salviati G. Contractile properties and Ca2+ release activity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1992;85:518–525. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.2.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff AJ, Gwathmey JK. Pathophysiology of cardiomyopathies: part 1 animal models and humans. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1994;9:357–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff AJ, Maki TM, Ellingsen O, Marsh JD. Expression of calcium channels in the adult heart is regulated by calcium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1791–1803. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipla K, Mattiello JA, Margulies KB, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR. The sarcoplasmic reticulum and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger both contribute to the Ca2+ transient of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1999;84:435–444. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einzig S, Detloff BLS, Borgwardt BK, Staley NA, Noren GR, Benditt DG. Cellular electrophysiological changes in “round heart disease” of turkeys: a potential basis for dysrhythmias in myopathic ventricles. Cardiovasc Res. 1981;15:643–651. doi: 10.1093/cvr/15.11.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingsen O, Davidoff AJ, Prasad SK, Berger HJ, Springhorn JP, Marsh JD, Kelly RA, Smith TW. Adult rat ventricular myocytes cultured in defined medium: phenotype and electromechanical function. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H747–H754. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.2.H747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:C1–C14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan DS, Wannenburg T, de Tombe PP. Decreased myocyte tension development and calcium responsiveness in rat right ventricular pressure overload. Circulation. 1997;95:2312–2317. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.9.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman MD, Copelas L, Gwathmey JK, Phillips PJ, Schoen F, Grossman W, Morgan JP. Deficient production of cyclic AMP: pharmacologic evidence of an important cause of contractile dysfunction in patients with end-stage heart failure. Circulation. 1987;75:331–339. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel MS, Marks ES, Patterson RE, Speir EH, Staedman KA, Keiser HR. Correlation of changes in cardiac calcium channels with hemodynamics in Syrian hamster cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Life Sci. 1987;41:153–159. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genao A, Seth K, Schimdt U, Carles M, Gwathmey JK. Dilated cardiomyopathy in turkeys: an animal model for the study of human heart failure. Lab Anim Sci. 1996;46:399–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass MG, Fuleihan F, Liao R, Lincoff AM, Chapados R, Hamlin R, Apstein CS, Allen PD, Ingwall JS, Hajjar RJ, Cory CR, O’Brien P, Gwathmey J. Differences in cardioprotective efficacy of adrenergic receptor antagonists in an animal model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Effects on gross morphology, global cardiac function, and twitch force. Circ Res. 1993;73:1077–1089. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez AM, Vaaldivia HH, Chens H, Lederer MR, Santana LF, Cannell MB, McCune SA, Altschuld RA, Lederer WJ. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science. 1997;2276:800–806. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruver EJ, Glass MG, Marsh JD, Gwathmey JK. An animal model of dilated cardiomyopathy: characterization of dihydropyridine receptors and contractile performance. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H1704–H1711. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.5.H1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruver EJ, Morgan JP, Stambler BS, Gwathmey JK. Uniform of calcium channel number and isometric contraction in human right and left ventricular myocardium. Basic Res Cardiol. 1994;89:139–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00788733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK. Cellular mechanisms of paired electrical stimulation in ferret ventricular myocardium: relationship between myocardial force and stimulus interval change. J Comp Physiol B. 1991;162:401–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00258961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Davidoff AJ. Experimental aspects of cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1993;8:480–495. [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Davidoff AJ. Pathophysiology of cardiomyopathies. 2. Drug-induced and other interventions. Curr Opin Cardiol. 1994;9:369–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Hajjar RJ. Intracellular calcium related to force development in twitch contraction of mammalian myocardium. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:531–538. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90029-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Morgan JP. Altered calcium handling in experimental pressure-overload hypertrophy in the ferret. Circ Res. 1985;57:836–843. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.6.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Morgan JP. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium mobilization in the right ventricular pressure-overload hypertrophy in the ferret: relationships to diastolic dysfunction and a negative treppe. Pflugers Arch. 1993;422:599–608. doi: 10.1007/BF00374008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Copelas L, MacKinnon R, Schoen FJ, Feldman MD, Grossman W, Morgan JP. Abnormal intracellular calcium handling in myocardium from patients with end-stage heart failure. Circ Res. 1987;61:70–76. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Slawsky MT, Briggs GM, Morgan JP. Role of intracellular sodium in the regulation of intracellular calcium and contractility. Effect of DPI 201–106 on excitation-contraction coupling in human ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:1592–1605. doi: 10.1172/JCI113771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Slawsky MT, Hajjar RJ, Briggs GM, Morgan JP. Role of intracellular calcium handling in force-interval relationships of human ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1599–1613. doi: 10.1172/JCI114611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Hajjar RJ, Solaro RJ. Contractile deactivation and uncoupling of cross-bridges. Effects of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on mammalian myocardium. Circ Res. 1991;69:1280–1292. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.5.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Liao R, Hajjar RJ (1994) Intracellular free calcium in hypertrophy and failure. In: Lorell B, Grossman W (eds) Diastolic relaxation of the heart. Kluwer Academic. Norwell pp 55–64

- Gwathmey JK, Liao R, Ingwall JS. Comparison of twitch force and calcium handling in papillary muscles from right ventricular pressure overload hypertrophy in weanling and juvenile ferrets. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;29:475–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Kim CS, Hajjar RJ, Khan F, DiSalvo TG, Matsumori A, Bristow MR. Cellular and molecular remodeling in a heart failure model treated with the beta-blocker carteolol. Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;45:H1678–H1690. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar RJ, Liao R, Young JB, Fuleihan F, Glass MG, Gwathmey JK. Pathophysiological and biochemical characterization of an avian model of dilated cardiomyopathy: comparison to findings in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:2212–2221. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.12.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar RJ, Kang JX, Gwathmey JK, Rosenzweig A. Physiological effects of adenoviral gene transfer of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase in isolated rat myocytes. Circulation. 1997a;95:423–429. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar RJ, Schmidt U, Kang JX, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A. Adenoviral gene transfer of phospholamban in isolated rat cardiomyocytes: Rescue effects by concomitant gene transfer of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Circ Res. 1997b;81:145–153. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenfuss G, Reinecke H, Studer R, Meyer M, Pieske B, Holtz J, Holubarsch C, Posival H, Just D, Drexler H. Relation between myocardial function and expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in failing and non-failing human myocardium. Circ Res. 1994;75:434–442. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao R, Nascimben L, Friedrich J, Gwathmey JK, Ingwall JS. Decreased energy reserve in an animal model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 1996;78:893–902. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1991;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JD, Smith TW. Receptors for beta-adrenergic agonists in cultured chick ventricular cells: relationship between agonist binding and physiologic effect. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;27:10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JD, Smith TW. Calcium channels and cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23:105–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulieri LA, Hasenfuss G, Leavitt B, Allen PD, Aplert NR. Altered myocardial force-frequency relation in human heart failure. Circulation. 1992;86:2017–2018. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.5.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimben L, Ingwall JS, Paolo P, Friedrich J, Gwathmey JK, Saks V, Pessina AC, Allen PD. Creatine kinase system in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circulation. 1996;94:1894–1901. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.8.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Barnett V, Sen L, Galper JB, Smith TW, Marsh JD. Direct contact between sympathetic neurons and rat cardiac myocytes in vitro increases expression of functional calcium channels. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1085–1093. doi: 10.1172/JCI115688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke B, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF, Kaab S, Tunin R, Marban E. Mechanisms of altered excitation-contraction coupling in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. I: experimental studies. Circ Res. 1999;84:562–570. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez NG, Hashimoto K, McCune S, Altshuld RA, Marban E. Origin of contractile dysfunction in heart failure: calcium cycling versus myofilaments. Circulation. 1999;99:1077–1083. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.8.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesaturo JA, Gwathmey JK. The role of mitochondria and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium handling upon reoxygenation of hypoxic myocardium. Circ Res. 1990;66:696–709. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.3.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer JM, Frohlich ED. Hemodynamic and myocardial function in young and old normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res [Suppl 1] 1973;32:28–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieske B, Kretschmann B, Meyer M, Holubarsch C, Weirich J, Posival H, Minami K, Just H, Hasenfuss G. Alterations in intracellular calcium handling associated with the inverse force-frequency relation in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1995;92:1169–1178. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen RP, Minobe W, Bristow MR. Calcium antagonist binding sites in failing and nonfailing human ventricular myocardium. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:691–696. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90147-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatchard G. The attraction of proteins for small molecules and ions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1949;51:660–672. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt U, Hajjar RJ, Helm PA, Kim CS, Doye AA, Gwathmey JK. Contribution of abnormal sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase activity to systolic and diastolic dysfunction in human heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1929–1937. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwinger RH, Bohm M, Schmidt U, Karczewski P, Bavendiek U, Flesch M, Krause EG, Erdmann E. Unchanged protein levels of SERCA II and phospholamban but reduced Ca2+ uptake and Ca2+-ATPase activity of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum from dilated cardiomyopathy patients compared with patients with nonfailing hearts. Circulation. 1995;92:3320–3328. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.11.3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen L, Smith TW. T-type Ca2+ channels are abnormal in genetically determined cardiomyopathic hamster hearts. Circ Res. 1994;75:149–155. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen L, O’Neill M, Marsh JD, Smith Thomas W. Myocyte structure, function, and calcium kinetics in the cardiomyopathic hamster heart. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H1153–H143. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.5.H1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorofsky SR, Shacklock PS, Wier WG, Balke CW. Alteration in calcium sparks with cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 1996;94:1159. [Google Scholar]

- Shorofsky SR, Wier WG, Balke CW. Calcium sparks in spontaneously hypertensive rats with cardiac hypertrophy. Biophys J. 1997;72:A343. [Google Scholar]

- Shorofsky SR, Balke CW, Gwathmey JK. Calcium channels in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Heart Failure Rev. 1998a;2:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorofsky SR, Izu L, Wier WG, Balke CW. ca2+ sparks triggered by patch depolarization in rat heart cells. Circ Res. 1998b;82:424–429. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorofsky SR, Aggarwall R, Corretti M, Baffa JM, Strum JM, Al-Seikhan BA, Kobayashi YM, Jones LR, Wier WG, Balke CW. Cellular mechanisms of altered contractility in the hypertrophied heart: big hearts, big sparks. Circ Res. 1999;84:424–434. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Allen PD, Lacro RV, Marks AR, Dennis AR, Schoen FJ, Grossman W, Marsh JD, Izumo S. Expression of dihydropyridine receptor (Ca2+ channel) and calsequestrin genes in the myocardium of patients with end-stage heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:927–935. doi: 10.1172/JCI115969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng GN, Boyden PA. Different effects of intracellular Ca2+ and protein kinase C on cardiac T and L calcium currents. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H364–H379. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.2.H364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow RL, Rice J, Jafri S, Marban E, O’Rourke B. Mechanisms of altered excitation-contraction coupling in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. II: Model studies. Circ Res. 1999;84:571–586. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue DT. Intracellular [Ca2+] related to rate of force development in twitch contraction of heart. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:H760–H770. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.4.H760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue DT, Wier WG. Estimation of intracellular [Ca2+] by non-linear indicators: a quantitative analysis. Biophys J. 1985;48:533–537. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83810-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue DT, Marban E, Wier WG. Relationship between force and intracellular [Ca2+] in tetanized mammalian heart muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1986;87:223–242. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]