Abstract

Background

It has been speculated that the γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (ggt) gene is present only in Neisseria meningitidis and not among related species such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria lactamica, because N. meningitidis is the only bacterium with GGT activity. However, nucleotide sequences highly homologous to the meningococcal ggt gene were found in the genomes of N. gonorrhoeae isolates.

Results

The gonococcal homologue (ggt gonococcal homologue; ggh) was analyzed. The nucleotide sequence of the ggh gene was approximately 95 % identical to that of the meningococcal ggt gene. An open reading frame in the ggh gene was disrupted by an ochre mutation and frameshift mutations induced by a 7-base deletion, but the amino acid sequences deduced from the artificially corrected ggh nucleotide sequences were approximately 97 % identical to that of the meningococcal ggt gene. The analyses of the sequences flanking the ggt and ggh genes revealed that both genes were localized in a common DNA region containing the fbp-ggt (or ggh)-glyA-opcA-dedA-abcZ gene cluster. The expression of the ggh RNA could be detected by dot blot, RT-PCR and primer extension analyses. Moreover, the truncated form of ggh-translational product was also found in some of the gonococcal isolates.

Conclusion

This study has shown that the gonococcal ggh gene is a pseudogene of the meningococcal ggt gene, which can also be designated as Ψggt. The gonococcal ggh (Ψggt) gene is the first identified bacterial pseudogene that is transcriptionally active but phenotypically silent.

Background

Two members of the gram-negative diplococci, Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, are particularly associated with pathological infections. N. meningitidis is specialized for the mucosa of the nasopharynx and causes meningitis and septicemia. N. gonorrhoeae is adapted for the mucosa of the urogenital tract and causes gonorrhoea and pelvic inflammatory diseases. Both species colonize only humans and share a great deal of relatedness at the nucleotide level [1]. This high degree of relatedness is reflected in the many common genetic, biochemical and antigenic features of the two bacteria.

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (also called γ-glutamyl aminopeptidase) (EC2.3.2.2; GGT) catalyzes the hydrolysis of γ-glutamyl compounds, and is found in a variety of bacteria such as Escherichia coli [2] and Helicobacter pylori [3,4]. To distinguish N. meningitidis from N. gonorrhoeae, GGT activity is used as one of the identification markers for N. meningitidis because N. meningitidis is positive for this activity but N. gonorrhoeae and related species, e.g., Neisseria lactamica, are not [5]. In fact, the detection of GGT activity is applied for the identification of N. meningitidis in the Gonochek II enzymatic identification system (E-Y Laboratories Inc., U.S.A.) [6-9]. From these empirical facts, it was believed that the gene encoding for GGT should exist only in N. meningitidis, but this has not been proven yet [3].

Recent remarkable progress in the sequencing of various genomes has led to the detection of nucleotide sequences that appear to be phenotypically silent, termed pseudogenes. The pseudogenes are defined as DNA sequences of formerly functional genes rendered nonfunctional by mutations and usually identified by their disrupted open reading frames (ORFs). Pseudogenes have been identified in a variety of eukaryotes, including insects [10], plants [11], and particularly vertebrates [10,12], but are relatively few in the bacterial genomes. Notable exceptions are intracellular bacterial parasites such as Rickettsia prowazekii and Mycobacterium leprae [13], which seem to have lost many genes due to obtaining nutritional supplies from the host cells. Cryptic genes such as the cel operon in E. coli [14-16] and the flagellar master operon in the genus Shigella [17-19] seem to be a kind of pseudogenes, but are different from pseudogenes because the cryptic genes completely retain intact ORFs, which can be occasionally activated by rare genetic events such as mutation, recombination, insertion of elements. As a whole, compared to the pseudogenes in eukaryotes, relatively few pseudogenes have been reported in bacterial genomes [20].

In this study, a gonococcal ggh gene, which is highly homologous to the meningococcal ggt gene, was found to be pseudogene. Sequence analyses of the flanking regions of both the ggt and ggh genes suggest that both genes were derived from a gene in a common ancestor, and subsequently diversified.

Results

The gonococcal ggh gene was highly homologous to the meningococcal ggt gene

Since GGT activity was detected only in N. meningitidis among the related species, it was speculated that the corresponding gene also existed only in N. meningitidis. However, by BLAST search, the nucleotide sequences highly homologous to the meningococcal ggt gene were found in the genome of N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 [GenBank:NC_002946]. The overall nucleotide sequence of the meningococcal ggt homologue was approximately 95 % identical to that of the meningococcal ggt gene (data not shown and additional file). Eleven N. gonorrhoeae clinical strains were analyzed by PCR, and the corresponding DNA fragments were amplified in all of these strains (Figure 1B), indicating that this gene was generally present in N. gonorrhoeae. To analyze whether ggt homologues existed in the genomes of the other neisserial strains, Southern blotting was performed (Figure 1C). DNA fragments that hybridized with the meningococcal ggt gene were found in the meningococcal and gonococcal genomes (Figure 1C lanes 1–3) but not in the other neisserial genomes (Figure 1C lanes 4–11). These results suggested that the meningococcal ggt homologue was present only in N. gonorrhoeae among the neisserial species examined. The putative gene in N. gonorrhoeae was named ggh (ggt gonococcal homologue).

Figure 1.

The presence of a meningococcal ggt gene homologue in N. gonorrhoeae. A. A schematic diagram showing the position of the set of primers used for the detection of ggt gene homologues. The black bar shows the region of the DNA probe used for Southern blotting in panel C. B. Amplification of gonococcal ggh gene by PCR. The genomic DNAs of neisserial species used for PCR were as follows: lane 1, H44/76 (N. meningitidis ggt+); lane 2, NIID113 (N. meningitidis ggt::IS) [49]; lane 3–13, ATCC49226, NIID54, NIID102, NIID103, NIID104, NIID105, NIID106, NIID107, NIID108, NIID109, NIID111 (N. gonorrhoeae). C. Southern blotting using the meningococcal ggt gene as a probe. Two micrograms of purified chromosomal DNA digested with ClaI were subjected to this analysis. Lane 1, H44/76 (N. meningitidis ggt+); lane 2, NIID113 (N. meningitidis ggt::IS) [49]; lane 3, NIID54 (N. gonorrhoeae); lane 4, ATCC23970 (N. lactamica); lane 5, ATCC13120 (N. flavescens); lane 6, ATCC14686 (N. denitrificans); lane 7, ATCC25295 (N. elongata); lane 8, ATCC14687 (N. canis); lane 9, ATCC14685 (N. cinerea); lane 10, NIID16 (N. mucosa); lane 11, NIID17 (N. sicca).

Variations of the nucleotide sequences of ggh genes among clinical isolates

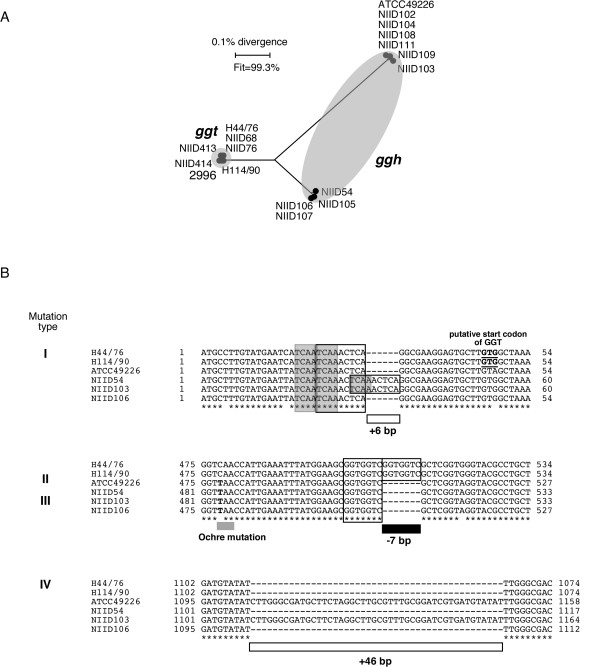

To characterize the gonococcal ggh gene, the ggh genes were amplified from the chromosomal DNA of 11 N. gonorrhoeae strains and sequenced. The nucleotide sequences of the ggt genes from 7 N. meningitidis strains and of the ggh genes from the 11 N. gonorrhoeae strains were aligned, and the distance matrix calculated from these data was displayed as a phylogenetic tree (Figure 2A). The results revealed that the nucleotide sequences of the gonococcal ggh genes were more divergent than those of the meningococcal ggt genes (Figure 2A). Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the 11 gonococcal ggh genes also showed that the mutations in the ggh gene consisted of the following four polymorphisms: 1) a 6-base insertion (named Type I), 2) an ochre mutation (Type II), 3) a 7-base deletion (Type III), 4) a 46-base insertion (Type IV) (Figure 2B and Table 2). In addition, all of the 11 ggh genes had one-nucleotide substitutions compared to the ggt genes in the same 25 sites (Figure 2B and additional file), with only 2 exceptions: a one-nucleotide variation in NIID109 (48th base A to G) and another in NIID105 (213th base G to A) (Table 2). The one-base substitutions in the common sites of the ggh genes strongly suggested that reconstruction of the ggh gene would have occurred at an early stage after speciation (See Discussion).

Figure 2.

A. Split graph showing the relationships among ggt genes in 7 meningococcal strains and ggh genes in 11 gonococcal strains. The sequence data have been submitted to the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank Databases under the following Accession Numbers:N. meningitidis strains H44/76 [DDBJ:AB089320], H114/90 [DDBJ:AB177989], 2996 [DDBJ:AB177990], NIID68 [DDBJ:AB177991], NIID76 [DDBJ:AB177992], NIID413 [DDBJ:AB177993] and NIID414 [DDBJ:AB177994]; N. gonorrhoeae strains ATCC49226 [DDBJ:AB175023], NIID54 [DDBJ:AB175024], NIID102 [DDBJ:AB193248], NIID103 [DDBJ:AB175025], NIID104 [DDBJ:AB175026], NIID105 [DDBJ:AB193249], NIID106 [DDBJ:AB175027], NIID107 [DDBJ:AB175028], NIID108 [DDBJ:AB193250], NIID109 [DDBJ:AB194328], NIID111 [DDBJ:AB193251]. The scale bar represents uncorrected distances, and a fit parameter is also shown. B. Alignment of the nucleotide sequences containing 4 kinds of differences in the ggt and ggh genes of N. meningitidis strains H44/76 and H114/90; N. gonorrhoeae strains ATCC49226, NIID54, NIID103 and NIID106, respectively. Sequence identity is represented as *, polymorphism among the sequences of the 6 strains is indicated by the appropriate letter, and the absence of a base is shown by a hyphen (-). The nucleotide substitution for an ochre (Type II) mutation is shown in bold. Boxes at the Type I and Type III mutations indicate the tandem repeat. The tetranucleotide repeat in type I is also shown as a gray box. The newly deduced start codon of the meningococcal GGT is shown in underlined bold.

Table 2.

Mutation types found in the ggh genes of 11 N. gonorrhoeae strains

| Mutation type* | ||||

| Strains | I (+6 bp) | II (ochre) | III (Δ7 bp) | IV (+46 bp) |

| ATCC49226 | ||||

| NIID102 | ||||

| NIID104 | - | + | + | + |

| NIID108 | ||||

| NIID111 | ||||

| NIID109 (48th A to G) | ||||

| NIID103 | + | + | + | + |

| NIID54 | + | + | + | - |

| NIID106 | ||||

| NIID107 | - | + | + | - |

| NIID105 (213th G to A) | ||||

"+" or "-" denotes the presence or absence of the mutation, respectively.

*Mutation type corresponds to the categories in Figure 2B.

Putative amino acid sequences in hypothetical coding region of the ggh genes

Due to the ochre (Type II) and 7-base deletion (Type III) mutations, the ORF in each ggh gene was completely disrupted by the formation of 8 or 20 stop codons (Figure 3A). In fact, none of the gonococcal isolates showed any GGT activity (data not shown and [5,9]), indicating that there was no expression of functional GGT-like protein in N. gonorrhoeae. All of these results showed that the gonococcal ggh gene was a pseudogene of the functional ggt gene in N. meningitidis. On the other hand, if the two types of mutations (Types II and III) in the ggh genes were artificially corrected, the hypothetical amino acid sequences were approximately 97 % identical to those of the meningococcal ggt genes and were highly conserved among the gonococcal ggh genes (Figure 3B). This result also supported the idea that the ggh and ggt genes were derived from a common ancestral gene and that the translational inactivation of the gonococcal ggh gene was solely due to the ochre (Type II) and the frame-shift mutations caused by the 7-base deletion (Type III).

Figure 3.

A. Positions of stop codons in the hypothetical ORF in the ggh gene. Black squares indicate the positions of stop codons and white squares indicate the ochre (Type II) mutation shown in Figure 2B. * indicates the position of the 7-bp deletion (Type III) mutation in the ggh gene. B. Putative translated products from the corrected nucleotide sequences of the ggh genes. The Type IV insertional mutation shown in Figure 2B is removed and the site of Type III deletion is replaced by the letter B. The site of the ochre (Type II) mutation is shown as X. The identical amino acid sequences between N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae are shown in a black box and amino acid sequences common to only N. gonorrhoeae are shown in a gray box.

The genetic organization of the ggt- and ggh-flanking regions in the genomes of N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae

By using the information in the database for N. meningitidis strain MC58 [21], N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 and N. lactamica (the neisserial species most closely related to the above two species) ST-640 strain, the flanking regions of the meningococcal ggt and the gonococcal ggh genes were further analyzed. The ggt and ggh genes were both localized in the identical gene cluster of fbp-ggt (or ggh)-glyA-opcA-dedA-abcZ in the genomes of N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, respectively (Figure 4). The fbp-glyA-dedA-abcZ locus was also found in the genome of N. lactamica but lacked the ggt and opcA homologues (Figure 4). This highly conserved genetic organization implied that a DNA island containing an original ggt gene was first incorporated into an ancestor's genome of the above three species and subsequently diversified after the speciation (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

Genetic organization of the genes around the ggt and ggh genes in N. meningitidis strain MC58 [21], N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090 [47] and N. lactamica strain ST-640 [48]. Black arrows and the open bar indicate coding and non-coding genes, respectively.

The expression of the ggh gene in N. gonorrhoeae

The hitherto identified bacterial pseudogenes are not expressed transcriptionally or translationally [20,22-24]. To examine the ggh transcriptional expression, dot blot analysis was first performed and RNA that hybridized with the ggt probe was detected in the total RNAs of 4 N. gonorrhoeae strains (Figure 5A). The transcriptional expression was also confirmed by RT-PCR, and the products were amplified with all 3 sets of primers from total RNA of all 4 N. gonorrhoeae strains tested (Figure 5B). These results strongly suggested that the full-length ggh gene transcript was expressed in N. gonorrhoeae. Primer extension analysis further revealed that the gonococcal ggh RNA was transcribed from the same starting point as the meningococcal ggt mRNA (Figure 5C and 5D). All of these results indicated that the gonococcal ggh gene was transcriptionally active though it was a pseudogene.

Figure 5.

Transcriptional expression of the ggh genes. A. Dot blot analysis using the meningococcal ggt gene as a probe. One to 16 micrograms of RNAs isolated from H44/76, HT1089 (H44/76 Δggt::spc) [39], ATCC49226, NIID54, NIID103 and NIID106 were subjected to this analysis. B. RT-PCR to detect the transcripts of the gonococcal ggh genes. The schematic figure in the box depicts the position of the primers used in this experiment (see Table 1). RT-PCR was performed without reverse transcriptase (RTase) (lanes 1 to 5) or with RTase (lanes 6 to 10). Lanes 1 and 6, H44/76 (N. meningitidis); lanes 2 and 7, ATCC49226 (N. gonorrhoeae); lanes 3 and 8, NIID54 (N. gonorrhoeae); lanes 4 and 9, NIID103 (N. gonorrhoeae); lanes 5 and 10, NIID106 (N. gonorrhoeae). The marker in the left-most lane is φ X174 DNA digested with HaeIII. Primer sets used for RT-PCR are shown on the left side, and the corresponding PCR products are indicated by arrows on the right side. C. Primer extension analysis to detect the transcriptional start point of the ggt and ggh genes. Total RNA extracted from H44/76 (N. meningitidis), ATCC49226 and NIID106 (N. gonorrhoeae) was used for the primer extension with AMV reverse transcriptase XL and biotin-labeled oligonucleotide ggt-ext-2. The arrow on the right side indicates the transcriptional start site. D. Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the upstream regions of the ggt and ggh genes. The sequence data have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank Databases under the following Accession Numbers:N. meningitidis strains H44/76 [DDBJ:AB193252], H114/90 [DDBJ:AB193253], N. gonorrhoeae strains ATCC49226 [DDBJ:AB193254], NIID54 [DDBJ:AB193255], NIID103 [DDBJ:AB193296], NIID106 [DDBJ:AB193256]. An identical nucleotide is represented as *. The transcriptional start site is shown in bold as +1. The putative -35, -10 elements and Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD) are depicted in the box, and the ideal -35 and -10 nucleotide sequences are shown above the boxes. The previously predicted start codon (ATG) [25] and newly predicted start codon (GTG) of the meningococcal {\it ggt} gene are underlined. The amino acid sequence deduced from the putative start codon GTG (shown in bold) in the meningococcal {\it ggt} gene is also shown under the corresponding nucleotide sequences.

To further study the translational expression of the truncated GGT-like protein in N. gonorrhoeae, Western blotting was performed with anti-meningococcal GGT rabbit antiserum [25]. When the same amounts of the whole cell extracts were analyzed (Figure 6B), approximately 15-kDa bands were detected in the extracts of NIID103 and NIID106 N. gonorrhoeae strains (Figure 6A lanes 5 and 7). Because the 15-kDa protein was not observed in the Δggh background of NIID103 and NIID106 (Figure 6A lanes 6 and 8), the 15-kDa protein was thought to be the ggh gene product whose translation was terminated at the 145th codon (Figure 3B). However, the 15-kDa protein was not found in the extracts of the ATCC49226 and NIID54 N. gonorrhoeae strains (Figure 6A, lanes 3 and 4) and seemed not to be expressed in any of the other gonococcal strains (see Discussion).

Figure 6.

Western blotting with anti-meningococcal GGT rabbit antiserum [25] (A) and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (B) of the whole cell extracts after SDS-PAGE. Bacterial whole cell extracts equivalent to 0.025 OD600 were analyzed. Lane 1, N. meningitidis strain H44/76; lane 2, HT1089 (H44/76 Δggt::spc); lane 3, ATCC49226 (N. gonorrhoeae); lane 4, NIID54 (N. gonorrhoeae); lane 5, NIID103 (N. gonorrhoeae); lane 6, HT1195 (NIID103 Δggh::spc); lane 7, NIID106 (N. gonorrhoeae); lane 8, HT1196 (NIID106 Δggh::spc). Black arrows show the bands corresponding to the processed small and large subunits of meningococcal GGT and the gray arrow indicates the 15-kDa band corresponding to the truncated protein product of the gonococcal ggh gene. M stands for molecular weight marker.

Discussion

In this study, it was shown that the gonococcal ggh gene is a member of bacterial pseudogenes, and is transcribed but not properly translated so that active ggh protein product is not produced. 11Fh-mtTFA [26], OsMu4-2 [27], NA88-A [28], Makorin1-p1 [29], Dnm3a2 [30] and pseudoNOS [31] genes are known to be transcriptionally active eukaryotic pseudogenes. In neisseriae, the gonococcal porA and ΨopcB genes have been reported as neisserial pseudogenes [1,32,33]. The porA pseudogene contains mutations in the promoter and the coding regions, and is not translated [24]. While some hypothetical bacterial pseudogenes with repetitive runs of A and T are speculated to be potentially expressed by transcriptional slippage [34], the expression, including the transcription, has not been proven yet. To our knowledge, the gonococcal ggh gene is the first identified bacterial pseudogene that is transcriptionally active.

The 15-kDa derivative of the putative ggh protein product is detected in the NIID103 and NIID106 N. gonorrhoeae strains but not in the ATCC49226 and NIID54 N. gonorrhoeae strains (Figure 6A). Since the predicted amino acid sequences of the putative 15-kDa proteins seem to be similar among the 4 gonococcal strains, the reason why the 15-kDa protein was not detected in ATCC49226 and NIID54 is not clear. The 15-kDa protein might be degraded in ATCC49226 and NIID54 backgrounds but not in NIID103 and NIID106 backgrounds. It seems unlikely that the 15-kDa protein encoded by the ggh gene has an essential function for N. gonorrhoeae because the 15-kDa protein is not always detected in any of gonococcal strains (Figure 6A).

Why does the gonococcal ggh gene still retain the transcriptional activity? There are some examples in which RNAs transcribed from pseudogenes have some biological functions: antisense RNA expressed from the pseudoNOS gene hybridizes with nNOS (nitric oxide synthase) mRNA, resulting in the suppression of the nNOS gene expression in the neurons of the snail Lymnaea stagnalis [31]. RNA of Makorin1-1p, a pseudogene of Makorin1, regulates the Makorin1 mRNA stability, which is important for the correct formation of the kidneys and bone in mice [29]. Some eukaryotic genes may be duplicated and one of the plural genes may be subsequently reconstructed due to its redundancy, resulting in a pseudogene. However, since a bacterial pseudogene generally does not have a functional counterpart (wild-type gene) in a single organism, the ggh RNA does not seem to have the same kind of biological function as the pseudoNOS and Makorin1-1p genes. In fact, we could not find any prominent phenotype for a Δggh gonococcal mutant (unpublished data). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the ggh RNA has some biological function(s) in other milieus such as the urogenital tract and further analyses will be required to address this possibility.

The ggt and ggh genes are located in the fbp-ggt (ggh)-glyA-opcA-dedA-abcZ common gene cluster in the genomes of both N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae (Figure 4) [23]. The genome of N. lactamica lacks ggt and opcA homologues in the fbp-glyA-dedA-abcZ locus (Figure 4 and [23]). It would not be the result of chance that the two ggt (or ggh) and opcA genes are located in the same respective sites of the fbp-glyA-dedA-abcZ gene locus of both N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae but not in that of N. lactamica. Moreover, it is also unlikely that a nonfunctional ggh gene was horizontally transferred into the gonococcal fbp-glyA-opcA-dedA-abcZ gene cluster since such a pseudogene could not have been sustained due to the lack of selection [23]. Therefore, it seems more probable that the fbp-ggt-glyA-opcA-dedA-abcZ gene cluster was present in an ancestor of the three neisserial species, and has been subsequently diversified independently among the three species, as shown for the opcA gene [23]. During the diversification, the meningococcal ggt gene has been maintained in an active state while the gonococcal ggh gene has been reconstructed by insertion, deletion and substitutions, resulting in the translational inactivation. In N. lactamica, the ggt and opcA homologues might have been lost because of their dispensability for N. lactamica (see below).

It is also interesting that the ggh gene has not been fully deleted from the gonococcal genome. The kinds and sites of mutations in the ggh genes are relatively few and highly conserved, respectively, among the gonococcal isolates (Figure 2B, Table 2 and additional file). It is also noted that, while in general the RNA polymerase-binding sites and SD regions of pseudogenes are highly degraded, there are also a few exceptions in species such as Y. pestis that could have emerged in recent evolutionary times [35]. Since the ribosome-binding sites (Shine-Dalgarno regions) of the gonococcal ggh gene are identical to those of the meningococcal ggt gene and the RNA polymerase-binding sites are almost completely conserved (with a one-nucleotide difference) (Figure 5D), it is speculated that the reconstruction of the ggh gene may have occurred in relatively recent evolutionary times. From the evolutional viewpoint, the drastic deletion of the approximately 2-kb DNA region containing the ggh gene in N. gonorrhoeae may not have been likely to occur in such a short period. Alternatively, deletion of the 2-kb DNA region may not be more advantageous for gonococcal evolution than reconstruction involving short deletions, insertions and substitutions.

The maintenance of a functional ggt gene in N. meningitidis would have some advantages for its survival. N. meningitidis causes meningitis, which is due to the meningococcal invasion into the human central nervous system, including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [36-38]. It has been shown that meningococcal GGT has a physiological function of acquiring cysteine from environmental γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl peptides under cysteine-limited environments such as the CSF [39]. Almost all (98.8 %) meningococcal isolates from humans are positive for GGT activity [40]. All of these results suggest that the GGT activity is important for N. meningitidis but not for N. gonorrhoeae. The dispensability of GGT activity for N. gonorrhoeae seems to be consistent with the fact that a cysteine-limited milieu such as the CSF in humans is not a natural gonococcal habitat. However, it is not very likely that the milieu of CSF exerts selective pressure for an active ggt gene because human CSF is not a relevant milieu for human-to-human spread of meningococcus [41]. We believe that the meningococcal GGT must have some unknown essential function(s) for N. meningitidis and further studies will elucidate the function(s).

Conclusion

Our data on the ggh gene indicate that the ggh gene in N. gonorrhoeae is a pseudogene of the functional ggt gene in N. meningitidis. To our knowledge, the ggh gene is the first reported bacterial pseudogene that is transcriptionally active but phenotypically silent. Our findings may also contribute to understanding the speciation of N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Seven N. meningitidis strains (H44/76, H114/90, 2996, NIID68, NIID76, NIID413 and NIID414) were described in our previous reports [42,43]. Ten N. gonorrhoeae strains (NIID54, NIID102, NIID103, NIID104, NIID105, NIID106, NIID107, NIID108, NIID109 and NIID111), one N. mucosa strain (NIID16) and one N. sicca strain (NIID17) were clinical isolates donated by T. Kuroki and Y. Watanabe. All of the clinical strains were mutually independent: they were isolated in different periods and from different persons who lived in different areas of Japan. The following 7 neisserial strains were obtained from ATCC (species / ATCC no.): N. gonorrhoeae / ATCC49226; N. lactamica / ATCC23970; N. flavescence / ATCC13120; N. denitrificans / ATCC14686; N. elongata / ATCC25295; N. canis / ATCC14687; N. cinerea / ATCC14685. All of the strains were stored by the gelatin disc method [42] and cultivated on GC agar (Becton-Dickinson) supplemented with 1 % IsovitaleX enrichment (Becton-Dickinson) at 37°C in 5 % CO2, or in GC broth (1.5 % proteose-peptone, 0.5 % NaCl, 0.05 % soluble starch, 0.1 % K2HPO4, 0.4 % KH2PO4, 1 % IsoVitaleX, 5 mM NaHCO3 10 mM MgCl2) at 37°C with shaking.

Isolation of chromosomal DNA, PCR, Southern blotting and dot blotting

Isolation of chromosomal DNA, PCR, Southern blotting and dot blotting were performed as described in our previous report [43].

Nucleotide sequence determination and analyses

The ggt and ggh genes were amplified with a set of primers (ggt-3 and ggt-4) by PCR, and the resulting products were purified using High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche) as templates for sequencing. The sequencing was performed as described previously [25]. Primers used for sequencing are listed in Table 1. Raw data from the ABI sequencer were assembled with the program DNASIS ver. 3.2 (HITACHI, Japan). The sequence alignment was performed with GENETYX-MAC ver.11 (GENETYX, Japan). Phylogenetic analyses were performed by constructing a distance matrix of nucleotide mismatches using the web site of the Belozersky Institute at Moscow State University [44] and visualized by Split decomposition analysis with the program SPLITSTREE, version 3.2 [45].

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primers for the sequencing of ggt and ggh genes, and RT-PCR (for ggt-9 and ggt-10) | ||||

| Oligonucleotide name | Position in sequence | Length (bp) | Sequence (5'-3') | Reference |

| ggt-3 | *1265–1286 | 21 | GACTGCTGATGACATTAGCGG | [49] |

| ggt-4 | *3250–3228 | 22 | GATTACTCACAATTTCCCCCTA | [49] |

| ggt-5 | *1791–1811 | 20 | CGATGCGTGCGACGCCGGAA | [25] |

| ggt-6 | *2676–2654 | 23 | ATAGCACATTGCCCGCCTTATCC | [25] |

| ggt-7 | *2241–2262 | 22 | CAAGATTTATCTGATTATCAAG | [25] |

| ggt-9 | *2779–2800 | 21 | GGGCAAACAGGTCGCCAATCG | [25] |

| ggt-10 | *2089–2068 | 21 | TGTAGCGGCACACCATTCGGC | [25] |

| ggt-18 | *1554–1534 | 21 | CGGTCAGTCCCGTTGCATGTT | [25] |

| Primers for RT-PCR | ||||

| ggt-29 | *1452–1475 | 24 | GGATGTCAAGTCATCCATGCCAAT | This study |

| ggt-20 | *1682–1659 | 24 | TGTCGTCTGCACCGCCACCATCGC | This study |

| ggt-31 | *1878–1901 | 24 | GGTACGCCTGCTATCCCTAAACTG | This study |

| ggt-22 | *3079–3056 | 24 | CGCACATCAGTCTTATAGCCCAAA | This study |

| Primer for primer extension | ||||

| primer-ext-2 | *1492–1467 | 26 | GTATTAACCTTACCTTGATTGGCATG (Biotin-labeled at the 5'-terminus) | This study |

*Numbers of positions indicate the position from the 5'-nucleotide of the ggt locus in N. meningitidis strain H44/76 [DDBJ:AB175033].

Construction of Δggh::spc N. gonorrhoeae mutants

HT1195 (NIID103 Δggh::spc) and HT1196 (NIID106 Δggh::spc), in which a spectinomycin resistance gene (spc) was inserted into the ggh gene, were constructed as follows: A 2-kb fragment containing the ggh gene of NIID103 or NIID106 was amplified by PCR and cloned in the SmaI site of pUC18 (Takara Bio) to construct pHT412 or pHT413, respectively. A blunted 1-kb fragment containing the spc gene [25] was inserted into the EcoRV sites of pHT412 and pHT413, respectively. The EcoRV sites are located at 277 bp and 1642 bp (NIID103 [DDBJ:AB175025]) and at 271 bp and 1590 bp (NIID106 [DDBJ:AB175027]) downstream from the transcriptional start point of each ggh gene, respectively (see Figure 5D). The resulting plasmids were named pHT414 and pHT415, respectively. Five hundred nanograms of the plasmids linearized by digestion with EcoRI were transformed into NIID103 and NIID106, respectively, as described previously [43]. Spectinomycin-resistant clones were selected on GC agar plates containing 75 μg/ml spectinomycin. The resulting mutants were isolated as Δggh::spc NIID103 (HT1195), and Δggh::spc NIID106 (HT1196), respectively. The allelic exchange was confirmed by PCR and Southern blotting.

RT-PCR

Bacteria grown on GC agar plates were suspended in 20 ml of GC broth to an OD600 of 0.1 and continuously cultured to mid-log phase (OD600 of ~ 0.6) at 37°C with shaking. The total RNA was isolated from the harvested bacteria as previously described [46] with an additional treatment with DNase I. RT-PCR was performed using one step RT-PCR Kit Ver. 1.1 (Takara Bio, Japan) with approximately 2 μg of total RNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. The products were visualized by electrophoresis in a 2 % agarose gel followed by ethidium bromide staining.

Primer extension analysis

Fifty micrograms of total RNA and 5 pmol of biotin-labeled primer (ggt-ext-2) were hybridized in 20 μl of buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM KCl). The hybridized RNA-DNA probe was treated with 35 units of AMV reverse transcriptase (RTase) XL (Takara Bio) in a reaction mixture (250 μM dNTPs, 1 × AMV reverse transcriptase XL buffer) at 37°C for 30 min. The ethanol-precipitated DNA product was dissolved in 20 μl of formamide dye (80 % formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, 0.025 % bromophenol blue, 0.025 % xylene cyanol). Sequencing of the ggt and ggh genes with the ggt-ext-2 primer was performed by using ΔTh polymerase sequencing high -cycle- (TOYOBO, Japan). Aliquots of the reaction products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 8 % acrylamide-7 M urea gel followed by capillary blotting to Hybond-N+ (Amersham). The bands were visualized with Imaging high (TOYOBO) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting were performed as described previously [43] using 1 × 103-fold diluted anti-GGT polyclonal rabbit antiserum [25] and 2 × 103-fold diluted horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham)

Abbreviations

GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; IS, insertional sequence; ORF, open reading frame; RTase, reverse transcriptase

Authors' contributions

HT carried out all of the studies including molecular genetic studies, sequence determination, sequence analyses and drafting the manuscript. HW made a critical reading of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published.

Supplementary Material

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences within the ggt and ggh genes of N. meningitidis H44/76 [DDBJ:AB089320]; N. meningitidis H119/90 [DDBJ: AB211221]; N. gonorrhoeae ATCC49226 [DDBJ:AB175023]; N. gonorrhoeae NIID103 [DDBJ:AB175025] and N. gonorrhoeae NIID106 [DDBJ:AB175029] strains, respectively. Sequence identity is represented as *, polymorphism within the sequences of the 5 strains is indicated by the appropriate letter, and the absence of a base is shown with a hyphen (-).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Kuroki and Y. Watanabe for donating neisserial clinical isolates. The data from the gonococcal genome sequencing project at the University of Oklahoma [47] and the genome sequence of Neisseria lactamica at the Sanger Institute are gratefully acknowledged. The N. lactamica genome sequence was generated by the Sanger Institute Pathogen Sequencing Unit [48]. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Grant no. 13770142 and 16790265).

Contributor Information

Hideyuki Takahashi, Email: hideyuki@nih.go.jp.

Haruo Watanabe, Email: haruwata@nih.go.jp.

References

- Nassif X. Interaction mechanisms of encapsulated meningococci with eucaryotic cells: what does this tell us about the crossing of the blood-brain barrier by Neisseria meningitidis? Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:71–77. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Hashimoto W, Kumagai H. Glutathione metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Mol Catal B. 1999;6:175–184. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1177(98)00116-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier C, Thiberge JM, Ferrero RL, Labigne A. Essential role of Helicobacter pylori γ glutamyltranspeptidase for the colonization of the gastric mucosa of mice. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1359–1372. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern KJ, Blanchard TG, Gutierrez JA, Czinn SJ, Krakowka S, Youngman P. γ Glutamyltransferase is a Helicobacter pylori virulence factor but is not essential for colonization. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4168–4173. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.4168-4173.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amato RF, Eriquez LA, Tomfohrde KM, Singerman E. Rapid identification of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis by using enzymatic profiles. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;7:77–81. doi: 10.1128/jcm.7.1.77-81.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Thomas KR. Rapid enzyme system for the identification of pathogenic Neisseria spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:857–858. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.5.857-858.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda WM, Ulanday MG, Bohnhoff M, LeBeau LJ. Evaluation of the RIM-N, Gonochek II, and Phadebact systems for the identification of pathogenic Neisseria spp. and Branhamella catarrhalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:734–737. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.5.734-737.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip A, Garton GC. Comparative evaluation of five commercial systems for the rapid identification of pathogenic Neisseria species. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:101–104. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.1.101-104.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welborn PP, Uyeda CT, Ellison-Birang N. Evaluation of Gonochek-II as a rapid identification system for pathogenic Neisseria species. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:680–683. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.4.680-683.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Onsins S, Aguade M. Molecular evolution of the Cecropin multigene family in Drosophila. functional genes vs. pseudogenes. Genetics. 1998;150:157–171. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loguercio LL, Wilkins TA. Structural analysis of a hmg-coA-reductase pseudogene: insights into evolutionary processes affecting the hmgr gene family in allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Curr Genet. 1998;34:241–249. doi: 10.1007/s002940050393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mighell AJ, Smith NR, Robinson PA, Markham AF. Vertebrate pseudogenes. FEBS Lett. 2000;468:109–114. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JG, Hendrix RW, Casjens S. Where are the pseudogenes in bacterial genomes? Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:535–540. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BG, Yokoyama S, Calhoun DH. Role of cryptic genes in microbial evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1983;1:109–124. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnetz K, Rak B. Regulation of the bgl operon of Escherichia coli by transcriptional antitermination. EMBO J. 1988;7:3271–3277. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LL, Hall BG. Characterization and nucleotide sequence of the cryptic cel operon of Escherichia coli K12. Genetics. 1990;124:455–471. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.3.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun AA, Tominaga A, Enomoto M. Detection and characterization of the flagellar master operon in the four Shigella subgroups. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3722–3726. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3722-3726.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun AA, Tominaga A, Enomoto M. Cloning and characterization of the region III flagellar operons of the four Shigella subgroups: genetic defects that cause loss of flagella of Shigella boydii and Shigella sonnei. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4493–4500. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4493-4500.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga A, Mahmoud MA, Mukaihara T, Enomoto M. Molecular characterization of intact, but cryptic, flagellin genes in the genus Shigella. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JO, Andersson SG. Pseudogenes, junk DNA, and the dynamics of Rickettsia genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:829–839. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettelin H, Saunders NJ, Heidelberg J, Jeffries AC, Nelson KE, Eisen JA, Ketchum KA, Hood DW, Peden JF, Dodson RJ, Nelson WC, Gwinn ML, DeBoy R, Peterson JD, Hickey EK, Haft DH, Salzberg SL, White O, Fleischmann RD, Dougherty BA, Mason T, Ciecko A, Parksey DS, Blair E, Cittone H, Clark EB, Cotton MD, Utterback TR, Khouri H, Qin H, Vamathevan J, Gill J, Scarlato V, Masignani V, Pizza M, Grandi G, Sun L, Smith HO, Fraser CM, Moxon ER, Rappuoli R, Venter JC. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science. 2000;287:1809–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JO, Andersson SG. Genome degradation is an ongoing process in Rickettsia. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1178–1191. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P, Morelli G, Achtman M. The opcA and ψopcB regions in Neisseria: genes, pseudogenes, deletions, insertion elements and DNA islands. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:635–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feavers IM, Maiden MC. A gonococcal porA pseudogene: implications for understanding the evolution and pathogenicity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:647–656. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Watanabe H. Post-translational processing of Neisseria meningitidis γ-glutamyl aminopeptidase and its association with inner membrane facing to the cytoplasmic space. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;234:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A, Mezzina M, Gadaleta G. Human mitochondrial transcription factor A (mtTFA): gene structure and characterization of related pseudogenes. Gene. 2002;291:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00600-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura N, Nakamura C, Ishii T, Kasai Y, Yoshida S. A transcriptionally active maize MuDR-like transposable element in rice and its relatives. Mol Genet Genomics. 2002;268:321–330. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau-Aubry A, Le Guiner S, Labarriere N, Gesnel MC, Jotereau F, Breathnach R. A processed pseudogene codes for a new antigen recognized by a CD8(+) T cell clone on melanoma. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1617–1624. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsune S, Yoshida N, Chen A, Garrett L, Sugiyama F, Takahashi S, Yagami K, Wynshaw-Boris A, Yoshiki A. An expressed pseudogene regulates the messenger-RNA stability of its homologous coding gene. Nature. 2003;423:91–96. doi: 10.1038/nature01535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees-Murdock DJ, McLoughlin GA, McDaid JR, Quinn LM, O'Doherty A, Hiripi L, Hack CJ, Walsh CP. Identification of 11 pseudogenes in the DNA methyltransferase gene family in rodents and humans and implications for the functional loci. Genomics. 2004;84:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korneev SA, Park JH, O'Shea M. Neuronal expression of neural nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) protein is suppressed by an antisense RNA transcribed from an NOS pseudogene. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7711–7720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07711.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C, Gray-Owen SD, Meyer TF. The role of neisserial Opa proteins in interactions with host cells. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassif X, Pujol C, Morand P, Eugene E. Interactions of pathogenic Neisseria with host cells. Is it possible to assemble the puzzle? Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1124–1132. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranov PV, Hammer AW, Zhou J, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF. Transcriptional slippage in bacteria: distribution in sequenced genomes and utilization in IS element gene expression. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mira A, Pushker R. The Silencing of Pseudogenes. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;PIMD 16014873 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CA, Rogers TR. Meningococcal disease. J Med Microbiol. 1993;39:3–25. doi: 10.1099/00222615-39-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deuren M, Brandtzaeg P, van der Meer JW. Update on meningococcal disease with emphasis on pathogenesis and clinical management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:144–166. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.1.144-166.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunkel AR, Scheld WM. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:118–136. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Hirose K, Watanabe H. Necessity of meningococcal γ-glutamyl aminopeptidase for the Neisseria meningitidis growth in rat cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and CSF mimicking medium. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:244–247. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.1.244-247.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kuroki T, Watanabe Y, Dejsirilert S, Saengsuk L, Yamai S, Watanabe H. Reliability of the detection of meningococcal γ-glutamyl transpeptidase as an identification marker for Neisseria meningitidis. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48:485–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kuroki T, Watanabe Y, Tanaka H, Inouye H, Yamai S, Watanabe H. Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis isolates collected from 1974 to 2003 in Japan by multilocus sequence typing. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:657–662. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Watanabe H. A broad-host-range vector of incompatibility group Q can work as a plasmid vector in Neisseria meningitidis: a new genetical tool. Microbiology. 2002;148:229–236. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- phylogenic tree prediction http://www.genebee.msu.ru/services/phtree_reduced.html

- Huson DH. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:68–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Inada T, Postma P, Aiba H. CRP down-regulates adenylate cyclase activity by reducing the level of phosphorylated IIA(Glc), the glucose-specific phosphotransferase protein, in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;259:317–326. doi: 10.1007/s004380050818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae genome sequencing strain FA1090 http://www.genome.ou.edu/gono.html

- The Sanger Institute: Neisseria lactamica http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/N_lactamica/

- Takahashi H, Tanaka H, Inouye H, Kuroki T, Watanabe Y, Yamai S, Watanabe H. Isolation from a healthy carrier and characterization of a Neisseria meningitidis strain that is deficient in γ-glutamyl aminopeptidase activity. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3035–3037. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.3035-3037.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences within the ggt and ggh genes of N. meningitidis H44/76 [DDBJ:AB089320]; N. meningitidis H119/90 [DDBJ: AB211221]; N. gonorrhoeae ATCC49226 [DDBJ:AB175023]; N. gonorrhoeae NIID103 [DDBJ:AB175025] and N. gonorrhoeae NIID106 [DDBJ:AB175029] strains, respectively. Sequence identity is represented as *, polymorphism within the sequences of the 5 strains is indicated by the appropriate letter, and the absence of a base is shown with a hyphen (-).