Abstract

Background

Intermittent aspiration of subglottic secretions (IASS) is commonly used to alleviate retention on the cuff, but inappropriate subglottic secretion drainage may lead to adverse effects, and fewer studies have been conducted on active subglottic airway humidification to improve the safety and effectiveness of IASS.

Methods

A randomized controlled trial was conducted from August 2023 to July 2024, involving 90 patients with flushable tracheostomy tubes: 48 patients received 30-min pre-drainage active humidification (intervention group), while 42 patients received sterile water flush (control group). The outcomes included vital signs, secretion viscosity, cuff pressure, inspired and exhaled tidal volume, catheter blockage, occult blood positivity, and the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

Results

The control group demonstrated a higher incidence of occult blood positivity (23.81% vs. 8.33%), blockage rate of the drainage catheter (19.05% vs. 4.17%), and Δcuff pressure (2.90 ± 1.39 cmH2O vs. 1.48 ± 0.99 cmH2O), with all comparisons yielding p < 0.05. Furthermore, the reduction rate of the viscosity of subglottic secretion was lower in the control group than in the intervention group (9.52% vs. 64.58%, p < 0.01). Although ΔVTe and VTleak of the intervention group were significantly increased, no significant differences were observed in ΔSpO2, ΔPETCO2, or the incidence of VAP.

Conclusion

Active subglottic airway humidification prior to IASS significantly reduces the positive rate of occult blood (OB) tests, the incidence of drainage catheter blockage, and secretion viscosity, with the exception of the incidence of VAP. It also stabilizes cuff pressure with minimal fluctuation. Although the intervention is associated with a decrease in exhaled tidal volume, it has no significant impact on pulse oxygen saturation or end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure.

Keywords: Subglottic airway, Humidification, Subglottic secretion drainage, Tracheotomy

Introduction

Long-term indwelling artificial airways in patients with tracheostomy can lead to the accumulation of secretions in the space between the subglottic area and the cuff. If these secretions, which contain a significant number of bacteria, are aspirated into the lower respiratory tract, this may predispose patients to VAP [1]. Studies show that the majority of bacterial pathogens associated with VAP originate from the retrograde inhalation of oropharyngeal colonized bacteria [2]. Pathogenic bacteria responsible for VAP can be cultured and isolated from secretions between the subglottic area and the cuff [3]. Notably, 85.7% of pathogenic bacteria can be cultured and isolated from subglottic secretions [4]. Subglottic secretion drainage (SSD) is an effective and economical strategy for preventing VAP, as it reduces aspiration and facilitates the removal of supraglottic secretions [5]. Evidence indicates that SSD can reduce the incidence of VAP, shorten the duration of mechanical ventilation, and decrease hospital length of stay [6, 7]. Consequently, current guidelines and expert consensus recommend SSD for VAP prevention [8, 9].

Two common techniques for SSD include continuous aspiration of subglottic secretions (CASS) and IASS, both of which are effective in reducing VAP incidence [3, 10]. CASS offers advantages such as high clearance rates of secretions and effective prevention of microaspiration. However, it may cause adverse effects, including mucosal dryness, injury, bleeding, and ulceration [6]. In contrast, IASS mimics the natural “swallow-clearance” mechanism, thereby reducing mucosal injury and avoiding sustained airway dryness [11]. Nevertheless, the intermittent nature of IASS may permit secretion accumulation between aspiration cycles, potentially increasing aspiration risk. Studies such as those by Klompas M. [12] and the Chinese Society of Neurosurgery [13] have shown that IASS is associated with a lower risk of tracheal mucosal injury compared to CASS [14]. As a result, IASS is widely recommended in clinical practice to allow mucosal recovery, minimize fluctuations in temperature and humidity, and reduce adverse effects related to negative pressure.

Despite its widespread use, the implementation of IASS lacks standardization, leading to considerable variability in practice [15]. This inconsistency contributes to a high positive rate of OB tests, along with complications such as obstruction of the subglottic drainage catheter, formation of sputum crusts, and episodes of choking cough [16, 17]. Catheter blockage has been reported in up to 27.8% of cases [18], while a meta-analysis indicated an OB positivity rate of 10.8% [19] and visible airway bleeding in 7.1% of patients undergoing IASS [20]. To maintain catheter patency and reduce mucosal injury and bleeding, flushing with 5–10 ml of sterile purified water has been advocated [21, 22]. However, previous research indicates that this measure may not effectively reduce secretion viscosity, catheter blockage, or mucosal irritation. Additionally, it may cause coughing and variations in heart rate and oxygen saturation [23].

Therefore, to enhance the safety and efficacy of IASS and minimize procedure-related adverse reactions, this study introduced an active subglottic airway humidification strategy by connecting the drainage catheter to a heated humidifier delivering warm, humidified airflow at 37 °C with 100% relative humidity. The aim was to evaluate whether this approach reduces adverse reactions during IASS.

Methods

The aim

To assess the effect of active subglottic airway humidification on preventing adverse reactions during IASS in patients with tracheostomy.

Design and setting

This randomized controlled trial was conducted at a large academic hospital in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. Ethical approval was granted by the Tongji Hospital Ethics Research Committee prior to the commencement of the study (approval no. TJ-IRB20230794). The trial was retrospectively registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR) at http://www.chictr.org.cn/ (trial ID: ChiCTR2500106495). Both verbal and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. For those unable to provide consent due to diminished capacity, informed consent was secured from their legal representatives.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Patients who were mechanically ventilated and underwent tracheostomy in the ICU of our hospital

Mechanical ventilation for more than 48 h following tracheostomy

Age ≥ 18 years

Ventilator mode set to pressure controlled ventilation

Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale score ranging from 0 to −2.

Exclusion criteria

Airway mucosal injury or bleeding, unobstructed suction catheter, severe hypoxemia, and/or carbon dioxide retention prior to IASS

Sudden changes in condition during drainage (procedure termination under physician supervision)

Refusal to participate in this study

Using a randomized numerical table method (random numbers were extracted from a computerized random number table, which was generated via Python’s random module, v3.8), we analyzed 90 cases from 126 registered patients who were admitted to our ICU from August 2023 to July 2024 and subsequently underwent mechanical ventilation treatment with tracheotomy as the study subjects. The 90 patients were divided into 42 cases in the control group and 48 cases in the intervention group.

Materials and equipment

All patients underwent percutaneous dilational tracheostomy utilizing a flushable tracheostomy tube (sputum suction tracheostomy tube and accessories, Smiths Medical ASD Co., Ltd., USA).

The dorsal surface of this catheter features a dedicated additional lumen that opens into the subglottic region (above the cuff), facilitating the aspiration of subglottic secretions via a larger oval orifice situated proximal to the cuff. To minimize the impact of confounding factors, the following equipment was employed in this study: a single type of ventilator (SERVO-s, Maquet Critical Care AB, Sweden), a capnography sensor (EMMA, Masimo, Sweden), a suction device (7A-23D, electric suction device from Yuwell Medical, China), a humidifier (MR850 wetting tanks from Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, New Zealand), a tracheotomy tube size of 8.0 mm, and a bridge tube size of 30F (10.0 mm). The subglottic secretion drainage pressure was maintained at a constant negative pressure of 60 to 80 mmHg for IASS [19]. IASS was performed at 2-h intervals for 5 min [14, 17].

Randomization and blinding

This study was a double-blind randomized controlled trial; patients were randomly assigned to an intervention group or a control group, and two roles (investigator and supervisor) were blinded to group allocation to minimize bias, except for ICU registered nurses. All medical teams have received specific training in evaluating secretion viscosity and have passed inter-rater reliability assessments.

The investigator was tasked with assessing the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants, prescribing the IASS operation, conducting data analysis, and ensuring quality control throughout the study. The ICU registered nurses primarily managed the subglottic secretion drainage procedure, and they were specifically trained in the IASS procedure. The supervisor, who served as the quality control nurse, was chiefly responsible for evaluating the outcome measures.

Intervention procedures

All patients were followed up under the ventilator cluster intervention strategy to prevent the VAP occurrence [24, 25]. The primary measures included head-of-bed elevation to 30° when there are no contraindications, daily assessments of the tracheostomy tube and wake-up plans, pharmacological treatment to prevent gastrointestinal stress ulcers, the use of limb air pressure pumps to prevent deep vein thrombosis, and 2% chlorhexidine oral care, among others. Prior to the operation, oropharyngeal secretions were routinely cleared in both groups. The subglottic drainage catheter of the tracheostomy tube was disinfected using a 0.2% povidone-iodine cotton swab, and the cuff pressure was maintained at 25 to 30 cmH2O. The IASS technique was performed in strict adherence to aseptic principles.

Patients in the control group were treated as follows:

Prior to flushing, the negative pressure drainage catheter was clamped with hemostatic forceps.

The catheter was then disconnected from the central negative pressure suction system, and a 10-ml syringe was used to aspirate 5–10 ml of sterilized purified water.

This solution was slowly injected into the subglottic area above the cuff via the subglottic drainage catheter to maintain patency.

After 3–5 min, the distal end of the tracheotomy tube—which was connected to the suction lumen leading to the collection container—was reattached to the central negative pressure suction device.

A constant negative pressure of 60–80 mmHg was applied. The IASS procedure was performed every 2 h, each session lasting 5 min.

In the intervention group, patients underwent active subglottic airway humidification and IASS in a step-by-step manner:

The inlet of the bridge tube was connected to the Y-shaped air supply outlet of the inspiratory limb of the ventilator circuit. This method ensures optimal humidified airflow and higher airway pressure to meet gas delivery requirements.

The variable-diameter outlet of the bridge tube was attached to the outer end of the subglottic drainage catheter of the tracheostomy tube.

Continuously heated and humidified airflow (37 °C, 100% relative humidity) was then delivered to the subglottic airway for 30 min.

IASS was performed at a constant negative pressure of 60–80 mmHg.

Drainage was conducted at a frequency of once every 2 h, with each session lasting 5 min.

Of note, this procedure may be associated with adverse events, including low tidal volume, low pulse oxygen saturation, and high end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Positive rate of the OB test: It refers to the proportion of positive results obtained from the OB test of subglottic secretions [19]. These positive findings are not detectable by visual inspection and require laboratory confirmation through secretion analysis.

Blockage rate of the drainage catheter: As continued suction fails to yield any secretions. Additionally, significant resistance is encountered when slowly injecting 5–10 ml of sterile purified water, resulting in incomplete delivery.

Reduction rate of the viscosity of subglottic secretions: Calculated as the change in viscosity of subglottic secretions divided by the total number of observed cases, multiplied by 100%. The grades in this study were defined as follows: water sample (thin appearance resembling running water, with high fluidity), viscous sample (dense appearance similar to thick substances, with moderate fluidity), and gel sample (appearance: jelly-like in a gel state, with minimal to no fluidity) [26].

Incidence of VAP: Defined as the number of VAP cases divided by the total number of days of mechanical ventilation, multiplied by ‰. The clinical diagnostic criteria for VAP were based on literature and guidelines [12, 27].

Secondary outcomes

The change in pulse oxygen saturation (ΔSpO2 = pulse oxygen saturation before IASS — pulse oxygen saturation after IASS).

The change in end-tidal carbon dioxide (ΔPETCO2 = end-tidal carbon dioxide before IASS — end-tidal carbon dioxide after IASS). The capnography sensor is positioned between the external end of the tracheostomy tube and the ventilator circuit to measure end-tidal carbon dioxide directly from the airway.

The change in cuff pressure (Δcuff pressure = cuff pressure before IASS — cuff pressure after IASS).

The change in exhaled tidal volume (ΔVTe = exhaled tidal volume before flush or humidification — exhaled tidal volume after flush or humidification): It refers to the total volume of gas exhaled from the lungs with each exhalation as monitored by a ventilator, reflecting the effective pulmonary ventilation. The ventilator utilizes distal flow sensors located within the ventilator itself.

Tidal volume leak (VTleak = inspired volume — exhaled volume): Which reflects the amount of air leakage volume during the flushing or humidification process. For the control group, the reduction in VTe is equal to the VTleak. For the intervention group, it reflects the mean flows through the humidifier from the ventilator to the subglottic airway, primarily used for humidification of the subglottic airway.

Sample size calculation

The sample size for the study was calculated using the G*Power software (version 3.1.9.3).

A sample size ratio of 1:1 was established for the two groups. With a power of 80%, effect size (φ = 0.5), and a significance level of 0.05, it was determined that 52 patients need to be included in each group. Considering a 20% loss rate, a total of at least 120 patients across both groups was calculated.

Statistical analysis

The results were processed using SPSS version 24.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and the data conformed to the normal distribution. The normality of the data was assessed via the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (proportion). The comparison of measurement data between the two groups was conducted using the t-test, while enumeration data were analyzed using the chi-square test. A two-tailed analysis was performed, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05.

Results

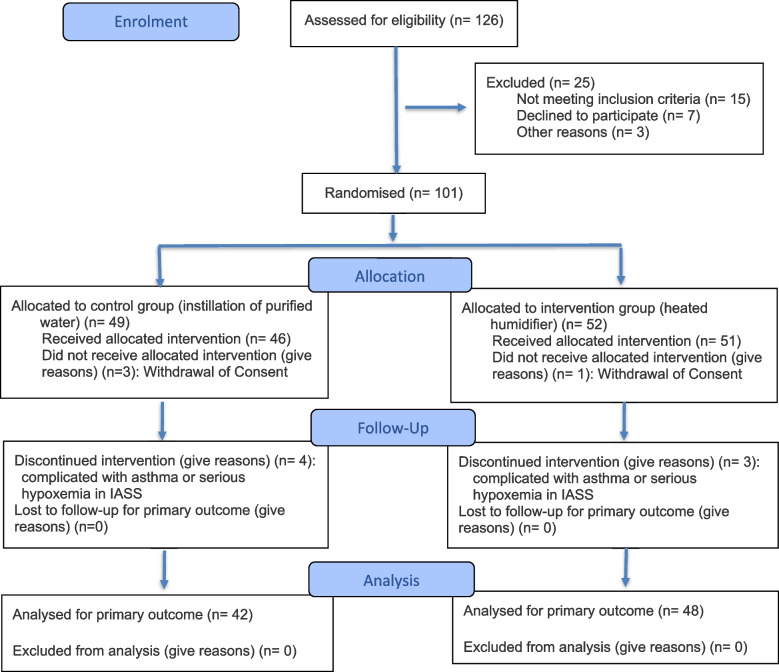

A total of 90 patients were ultimately analyzed in the study (Fig. 1), comprising 50 males and 40 females. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 89 years, with a mean age of 50.84 ± 18.32 years. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Status Score II (APACHE II) scores averaged 27.68 ± 4.20. In Table 1, the comparison of the two groups regarding demographics, disease severity, history, vital signs, and PETCO2 showed no statistically significant differences (all p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow chart

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics at baseline (n = 90)

| Demographics and clinical characteristics | Control group (n = 42) | Intervention group (n = 48) | Statistic test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Men | 23 (54.8) | 27 (56.3) | 0.020b | 0.887 |

| Age | 51.64 ± 19.07 | 50.15 ± 17.80 | 0.385a | 0.701 |

| Disease severity | ||||

| APACHE II | 28.36 ± 4.36 | 27.08 ± 4.00 | 1.455a | 0.152 |

| History (%) | ||||

| Respiratory | 11(26.2) | 9(18.8) | 0.717b | 0.397 |

| Cardiac | 6(14.3) | 7(14.6) | 0.002b | 0.968 |

| Digestive | 5(11.9) | 3(6.3) | 0.884b | 0.347 |

| Kidney | 6(14.3) | 9(18.8) | 0.321b | 0.571 |

| Neuro | 2(4.8) | 5(10.4) | 0.999b | 0.318 |

| Sepsis | 7(16.7) | 10(20.8) | 0.254b | 0.614 |

| Other | 5(11.9) | 5(10.4) | 0.050b | 0.823 |

| Vital signs | ||||

| HR, bpm | 86.33 ± 13.65 | 83.77 ± 17.18 | 0.776a | 0.440 |

| ABP, mmHg | 121.57 ± 17.31 | 120.77 ± 16.61 | 0.224a | 0.824 |

| SpO2, % | 96.62 ± 2.32 | 96.17 ± 2.85 | 0.817a | 0.416 |

| PETCO2, mmHg | 43.02 ± 7.70 | 42.19 ± 6.80 | 0.547a | 0.586 |

The values were conformed to the normal distribution

Abbreviations: APACHE II Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, PETCO2 end-tidal carbon dioxide, HR heart rate, ABP arterial blood pressure, SpO2 saturation of peripheral oxygen

aT-test

bChi-square test

Table 1 indicated that there are no significant differences in demographics, disease severity, history, vital signs, and PETCO2 between the two groups prior to IASS. Furthermore, Table 2 presented no significant differences in VAP (χ2 = 0.052, p = 0.820) between the two groups. However, significant differences were observed in the OB test (χ2 = 4.084, p = 0.043) and blockage rate of the drainage catheter (χ2 = 5.022, p = 0.025) between the two groups. These results indicated that the control group experienced greater damage to the airway mucosa and a higher blockage rate of the drainage catheter during the IASS procedure. Furthermore, the reduction rate of the viscosity of subglottic secretions in the intervention group was significantly higher than that in the control group (χ2 = 28.574, p = 0.000), with the difference being statistically significant.

Table 2.

Comparison of OB test, blockage rate of drainage catheter, reduction rate of the viscosity of subglottic secretions, and VAP. Number (proportion)

| Variable | Control group (n = 42) | Intervention group (n = 48) | χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive rate of the OB test | 10 (23.81%) | 4 (8.33%) | 4.084 | 0.043 |

| Blockage rate of the drainage catheter | 8 (19.05%) | 2 (4.17%) | 5.022 | 0.025 |

| Reduction rate of the viscosity of subglottic secretions | 4 (9.52%) | 31 (64.58%) | 28.574 | 0.000 |

| VAP | 3/304 (9.87 ‰)a | 4/341 (11.73‰)b | 0.052 | 0.820 |

The values were analyzed by chi-square test

Abbreviations: OB occult blood, VAP ventilator-associated pneumonia

a,bVAP case/the total number of days of mechanical ventilation

Table 3 revealed no significant differences in ΔSpO2 (t = 1.124, p = 0.264) and ΔPETCO2 (t = 0.01, p = 0.992) between the two groups. However, Δcuff pressure in the control group was significantly higher than that in the intervention group (2.90 ± 1.39 cmH2O vs. 1.48 ± 0.99 cmH2O), demonstrating a statistically significant difference (t = 5.648, p = 1.49 × 10−6). This suggests that the control group experienced a more pronounced decrease in cuff pressure after IASS. Additionally, the higher ΔVTe in the intervention group (t = 8.235, p = 1.07 × 10−11) poses the risk of altering minute ventilation and possibly even insufficient ventilation; the higher VTleak relative to ΔVTe ensures humidification of the subglottic airway (t = 32.397, p = 8.14 × 10−42).

Table 3.

Comparison of changers in SpO2, PETCO2, cuff pressure, VTe, and VTleak in two groups. Values are mean ± SD

| Variable | Control group (n = 42) | Intervention group (n = 48) | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔSpO2, % | 2.17 ± 0.93 | 2.42 ± 1.15 | 1.124 | 0.264 |

| ΔPETCO2, mmHg | 3.14 ± 1.41 | 3.15 ± 1.34 | 0.010 | 0.992 |

| ΔCuff pressure, cmH2O | 2.90 ± 1.39 | 1.48 ± 0.99 | 5.648 | 1.49 × 10−6 |

| ΔVTe, ml | 4.71 ± 2.51 | 13.52 ± 6.52 | 8.235 | 1.07 × 10−11 |

| VTleak, ml | 4.71 ± 2.51 | 49.17 ± 8.57 | 32.397 | 8.14 × 10−42 |

The values were analyzed by T-test

Abbreviations: VTe exhaled tidal volume, VTleak tidal volume leak

The results demonstrated that this approach not only effectively diminished fluctuations in the cuff pressure but also reduced the viscosity of subglottic secretions on the cuff, the positive rate of OB tests, and the blockage rate of the drainage catheter, thereby ensuring the safety and effectiveness of IASS.

Note: The values were conformed to the normal distribution. aT-test. bChi-square test. Abbreviations: APACHE II Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, PETCO2 end-tidal carbon dioxide, HR heart rate, ABP arterial blood pressure, SpO2 saturation of peripheral oxygen

Discussion

The implementation of active subglottic airway humidification prior to IASS significantly reduced the positive rate of OB tests. This finding suggests that the intervention mitigated the airway mucosal irritation and injury more effectively than standard IASS alone. Literature indicated that negative pressure suction alters pressure above the cuff, causing local humidity and temperature to deviate from the normal physiological state of the airway mucosa, thereby adversely affecting the mucosa [28]. This manifests specifically as sparse, disordered cilia arrangement or even detachment. Sustained high-pressure suction can also severely damage vascular walls and increase their permeability, causing blood to leak through dilated intercellular spaces in the vascular endothelium and damaged basement membranes, leading to hemorrhage in the tracheal mucosa [29]. In this study, active subglottic airway humidification above the cuff effectively prevented mucosal damage and bleeding attributable to dryness and fluid loss.

This study demonstrated that enhanced active humidification of the subglottic airway effectively decreased the viscosity of subglottic secretions on the cuff, thereby reducing the blockage rate of the drainage catheter. Literature reports have indicated that sustained negative pressure above the cuff lowers the vapor saturation pressure, impairing the ability of the airway mucosa to maintain a moisture-saturated state. The airflow generated by negative pressure suction further exacerbates this drying effect, promoting viscous sputum, difficult secretion clearance, and potential crust formation [30]. Although regular subglottic flush has been shown to reduce the viscosity of retained secretions [31], the present study found that active subglottic airway humidification was more effective in facilitating secretion drainage by reducing viscosity. Moreover, highly viscous secretions tend to accumulate above the cuff, increasing the blockage risk of the catheter port. The narrow lumen of the drainage catheter, along with potential blockage caused by tracheal mucosa or sputum crusts at its opening, may even lead to invagination of the tracheal mucosa into the catheter. This significantly impairs the effectiveness of subglottic secretion clearance [16].

In clinical practice, IASS is widely used to reduce secretion accumulation on the cuff. To facilitate effective drainage and prevent catheter occlusion, sterile purified water flushing or irrigation is typically performed prior to IASS. However, the Δcuff pressure in the control group was significantly higher than that in the intervention group. This indicates that mechanical flushing of retained secretions may aggravate airway discomfort, provoking irritative coughing and respiratory distress. These reactions may contribute to cuff displacement and a consequent decline in cuff pressure, as observed in the control group. In contrast, the intervention group received active warming and humidification of the subglottic airway, which better mimics the natural physiological conditions of the respiratory tract. This approach improved patient comfort and tolerance, supporting more stable cuff pressure management.

A bridge tube was used to transfer airflow from the Y-shaped expiratory end of the ventilator circuit to the subglottic drainage catheter of the tracheostomy tube. In the intervention group, this configuration resulted in a reduction of exhaled tidal volume, as part of the ventilator-delivered tidal volume was diverted into the subglottic drainage catheter, causing VTleak by 49.17 ± 8.57 ml. The mean subglottic airflow delivered via the humidifier corresponds to this VTleak, with an average flow rate of 49.17 ml per breath, ensuring adequate humidification. To avoid inadequate pulmonary ventilation, pressure-controlled ventilation was applied to compensate for the air leak. As a result, the actual reduction in pulmonary ventilation per respiratory cycle was only 13.52 ± 6.52 ml, thus maintaining sufficient oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide clearance. The findings showed no significant differences in end-tidal carbon dioxide or pulse oxygen saturation between the two groups.

To mitigate the risk of inadequate pulmonary ventilation caused by tidal volume shunting into the subglottic drainage catheter, strategies to ensure adequate alveolar ventilation and reduce dead space should be employed. Future research may explore the application of ventilator-independent humidification devices in clinical practice, such as high-flow humidified oxygen therapy systems and the Venturi humidification device. While these devices can prevent adverse effects on ventilator mechanics, which include patient–ventilator asynchrony, ventilator triggering, flow delivery, and bias flow, they may increase healthcare costs.

Unexpectedly, this study demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the incidence of VAP between the two groups. Firstly, this study concluded that both intervention approaches employed were effective in clearing subglottic secretions and reducing the risk of microaspiration. Secondly, the rigorous implementation of the ventilator cluster intervention strategy during the study period significantly lowered the baseline incidence of VAP, which may have masked any additional marginal benefit attributable to the study interventions. Finally, the small sample size may explain the lack of an observed difference in the incidence of VAP, as it limited the statistical power to detect a significant effect.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the data were collected exclusively from four intensive care units in a single center, which may restrict the generalizability of the results.

Second, the sample size may have been insufficient, particularly for detecting differences in outcomes with low incidence rates, such as VAP. Additionally, the assessment of secretion viscosity carries inherent subjectivity. Furthermore, the research lacks long-term follow-up data on outcomes such as tracheal stenosis.

Conclusion

The active management of warmth and humidity in the subglottic airway prior to the implementation of IASS not only significantly reduced fluctuations in the cuff pressure but also effectively decreased the viscosity of subglottic secretions, the positive rate of occult blood tests, and the blockage rate of drainage catheters. Although active humidification of the subglottic airway may lead to a decrease in exhaled tidal volume, it does not significantly affect the patient’s pulse oxygen saturation or end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure.

Acknowledgements

The authors express a special thanks to all patients, ICU registered nurses, and two teaching supervisors for their participation in the study and their clinical practice. Thanks to the four intensive care units of the hospital for providing resources and support for this study.

Authors’ contributions

**Weiquan Liu:** Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, and Project administration. **Chunling Guo:** Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. **Juan Deng:** Resources, Data curation. **Mengyao Jiang:** Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Supervision. **Jie Xiong:** Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This research was supported by the Scientific Research Fund of Tongji Hospital through two grants: TJ2022D04, which financed the project “Construction, Application, and Effect Evaluation of an Evidence-Based Practice Program for Postural Drainage of Airway Secretions in Critically Ill Patients,” and TJ2023C07, which supported the project “Effect of Infusion Device Replacement Interval on Central Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in ICU Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial.”

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chunling Guo, Email: guochunling5759@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

Jie Xiong, Email: 914808880@qq.com.

References

- 1.Wicky PH, Martin-Loeches I, Timsit JF (2022) HAP and VAP after guidelines. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 43(2):248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blakeman TC, Scott JB, Yoder MA, Capellari E, Strickland SL (2022) AARC clinical practice guidelines: artificial airway suctioning. Respir Care 67(2):258–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang XA, Du YP, Fu BB, Li LX (2018) Influence of subglottic secretion drainage on the microorganisms of ventilator associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis for subglottic secretion drainage. Medicine (Baltimore) 97(28):e11223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallés J, Artigas A, Rello J, Bonsoms N, Fontanals D, Blanch L, Fernández R, Baigorri F, Mestre J (1995) Continuous aspiration of subglottic secretions in preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 122(3):179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacherade JC, Azais MA, Pouplet C, Colin G (2018) Subglottic secretion drainage for ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention: an underused efficient measure. Ann Transl Med 6(21):422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacherade JC, De Jonghe B, Guezennec P, Debbat K, Hayon J, Monsel A et al (2010) Intermittent subglottic secretion drainage and ventilator-associated pneumonia: a multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182(7):910–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caroff DA, Li L, Muscedere J, Klompas M (2016) Subglottic secretion drainage and objective outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 44(4):830–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Álvarez Lerma F, Sánchez García M, Lorente L, Gordo F, Añón JM, Álvarez J et al (2014) Guidelines for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia and their implementation. The Spanish “Zero-VAP” bundle. Med Intensiva 38(4):226–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muscedere J, Rewa O, McKechnie K, Jiang X, Laporta D, Heyland DK (2011) Subglottic secretion drainage for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 39(8):1985–1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F, Bo L, Tang L, Lou J, Wu Y, Chen F et al (2012) Subglottic secretion drainage for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 72(5):1276–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmoodpoor A, Hamishehkar H, Hamidi M, Shadvar K, Sanaie S, Golzari SE et al (2017) A prospective randomized trial of tapered-cuff endotracheal tubes with intermittent subglottic suctioning in preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. J Crit Care 38:152–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klompas M, Branson R, Cawcutt K, Crist M, Eichenwald EC, Greene LR et al (2022) Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia, ventilator-associated events, and nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in acute-care hospitals: 2022 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 43(6):687–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chinese Society of Neurosurgery, Chinese Neurosurgery Intensive Management Collaborative Group. Consensus on airway management for critically ill neurosurgery patients in China (2016). Chinese Medical Journal 2016;6(21):1639–1642. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.021.004.

- 14.Wen Z, Zhang H, Ding J, Wang Z, Shen M (2017) Continuous versus intermittent subglottic secretion drainage to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Crit Care Nurse 37(5):e10–e17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang YP, Feng XQ, Tang JY, Hang XX, Mao Y, Guo ZY (2017) Best-evidence application of subglottic retention attraction in adult patients with mechanical ventilation. Chin J Emerg Med 29(6):845–850. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2020.06.021 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dragoumanis CK, Vretzakis GI, Papaioannou VE, Didilis VN, Vogiatzaki TD, Pneumatikos IA (2007) Investigating the failure to aspirate subglottic secretions with the evac endotracheal tube. Anesth Analg 105(4):1083–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang M, Ao X (2016) Research progress and implementation status of standards for artificial airway management. Chin J Nurs 51(12):1479–1482. 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2016.12.014 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Ma J, Hui CH, Song WJ (2013) The role of intermittent subglottic lavage combined with continuous subglottic suction in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with orotracheal intubation. Chin J Nurs 48(1):3. 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2013.01.006 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin’e W, Fangchen G, Zheng L. Effects of two different subglottic secretion drainaging methods on ventilator -associated pneumonia and tracheal mucosal injury in patients with mechanical ventilation: a meta-analysis. Journal of Nanjing Medical University (Natural Sciences) 2020;40(11):1645–1653. 10.7655/NYDXBNS20201113.

- 20.Wen XH, Sun H, Shao XP, Dong ZH, Ni SM, Tao IW (2007) Continuous subglottic suction to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chin J Emerg Med 16(2):202–206. 10.3760/j.issn:1671-0282.2007.02.023 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouza E, Pérez MJ, Muñoz P, Rincón C, Barrio JM, Hortal J (2008) Continuous aspiration of subglottic secretions in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the postoperative period of major heart surgery. Chest 134(5):938–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han ML, Wang F, Ma LL (2013) Evaluation of the effect of intermittent subglottic suction in patients undergoing tracheotomy. Chin J Mod Nurs 19(21):2585–2587. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2907.2013.21.038 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu WL, Zhang WY (2014) Research progress of continuous subglottic suction in patients with orotracheal intubation. Nurs J Chin PLA 31(1):43–45. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2014.01.013 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, Greene LR, Howell MD, Lee G et al (2014) Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 35(Suppl 2):S133–S154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muscedere J, Dodek P, Keenan S, Fowler R, Cook D, Heyland D, VAP Guidelines Committee and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (2008) Comprehensive evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for ventilator-associated pneumonia: prevention. J Crit Care 23(1):126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Neal PV, Munro CL, Grap MJ, Rausch SM (2007) Subglottic secretion viscosity and evacuation efficiency. Biol Res Nurs 8(3):202–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, Huang Y, Zhang TT, Cao B, Wang H, Zhuo C et al (2019) Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults (2018 edition). J Thorac Dis 11(6):2581–2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui H, Jia Yl (2016) Intermittent subglottic suction method compared with continuous subglottic suction method for airway secretion removal effect of 200 cases of control study. Chinese practical medicine 11(2):265–266 (https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:ZSSA.0.2016-02-199) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao XY, Shi XN, Yu ZP, Zou SE, Xu Y (2008) Experimental study on reducing airway suction on animal respiratory mucosal injury. Chin J Nurs 43(1):87–90. 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2008.01.035 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu WQ, Wang F (2018) Application of cough peak flow velocity reconstruction in the removal of air sac residue. Chin J Emerg Resusc Disaster Med 13(5):31–35. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-6966.2018.05.031 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouzé A, Jaillette E, Poissy J, Préau S, Nseir S (2017) Tracheal tube design and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir Care 62(10):1316–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.