Abstract

The Cdc25 dual-specificity phosphatases control progression through the eukaryotic cell division cycle by activating cyclin-dependent kinases. Cdc25 A regulates entry into S-phase by dephosphorylating Cdk2, it cooperates with activated oncogenes in inducing transformation and is overexpressed in several human tumors. DNA damage or DNA replication blocks induce phosphorylation of Cdc25 A and its subsequent degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Here we have investigated the regulation of Cdc25 A in the cell cycle. We found that Cdc25 A degradation during mitotic exit and in early G1 is mediated by the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C)Cdh1 ligase, and that a KEN-box motif in the N-terminus of the protein is required for its targeted degradation. Interestingly, the KEN-box mutated protein remains unstable in interphase and upon ionizing radiation exposure. Moreover, SCF (Skp1/Cullin/F-box) inactivation using an interfering Cul1 mutant accumulates and stabilizes Cdc25 A. The presence of Cul1 and Skp1 in Cdc25 A immunocomplexes suggests a direct involvement of SCF in Cdc25 A degradation during interphase. We propose that a dual mechanism of regulated degradation allows for fine tuning of Cdc25 A abundance in response to cell environment.

Keywords: APC/C/Cdc25 A/cell cycle/cyclosome/SCF

Introduction

Orderly progression through the cell division cycle in all eukaryotic cells requires the periodic activation of cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) (Miller and Cross, 2001). The activation state of Cdks is regulated by association with cyclin and CDK-inhibitor (Cki) subunits. Furthermore, phosphorylation within the so-called ‘activation loop’ controls enzyme activity, and reversible phosphorylation on residues located near the ATP-binding site of the protein provides a further mechanism for immediate inactivation/re-activation of Cdks (Sherr and Roberts, 1999). In mammalian cells, Cdc2/cyclin B1 is kept inactive by phosphorylation on Thr14 and Tyr15 during interphase, and is suddenly activated at the end of G2 to lead cells into mitosis (Krek and Nigg, 1991; Norbury et al., 1991). Moreover, inhibitory tyrosine phosphorylation of Cdc2 in response to DNA damage underlies the G2/M checkpoint (Blasina et al., 1997). A failure to dephosphorylate analogous residues in Cdk2 keeps the kinase inactive upon induction of DNA damage or inhibition of DNA replication (Mailand et al., 2000; Molinari et al., 2000). Dephosphorylation of these critical threonine and tyrosine residues is mediated by the Cdc25 dual-specificity protein phosphatases. In mammalian cells, Cdc25 C dephosphorylates Cdc2/cyclin B1 (Strausfeld et al., 1994) and is essential for progression through the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Sadhu et al., 1990; Heald et al., 1993). Two related enzymes, Cdc25 A and Cdc25 B, have been subsequently identified (Galaktionov and Beach, 1991) and shown to be deregulated in cancer (Galaktionov et al., 1995; Gasparotto et al., 1997; Hernandez et al., 1998; Wu et al., 1998). Cdc25 A is required for DNA replication and entry into S-phase, its primary substrate being Cdk2 (Hoffmann et al., 1994; Jinno et al., 1994; Blomberg and Hoffmann, 1999). Cdc25 A is a transcriptional target of c-Myc and E2F, and its RNA and protein levels increase as cells are stimulated to enter the cycle from quiescence (Galaktionov et al., 1996; Blomberg and Hoffmann, 1999; Vigo et al., 1999). On the contrary, Cdc25 B appears to play a role in mitosis with a different timing in respect to Cdc25 C (Karlsson et al., 1999).

Cdc25 A is activated by phosphorylation (Hoffmann et al., 1994) and its abundance is regulated by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Degradation of Cdc25 A via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway occurs in response to inhibition of DNA replication or induction of DNA damage (Mailand et al., 2000; Molinari et al., 2000). Ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation via the proteasome represent a fundamental mechanism for regulating protein abundance through an irreversible mechanism (Pickart, 2001; Harper, 2002). The system operates by transferring ubiquitin moieties to protein substrates via a series of enzymatic reactions catalyzed by E1, E2 and E3 enzymes, the latter being the determinant for target selectivity and timing of degradation (Hochstrasser, 1996; Hershko, 1997). The E3 family comprises HECT domain E3 enzymes and RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligases, among which are the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome (APC/C) and the Skp1/Cullin/F-box (SCF) protein complexes (for a review, see Jackson et al., 2000).

While APC is mainly involved in controlling the abundance of mitotic regulators (Zachariae and Nasmyth, 1999), SCF ligases have a broader function in many physiological processes by ubiquitylating proteins involved in cell cycle regulation and signal transduction (Peters, 1998; Koepp et al., 1999; Harper, 2002). Specific timing of substrate degradation by the APC/C complex depends upon the targeting subunit with which they interact. Two such adaptors have been identified, Cdc20 and Cdh1 (Visintin et al., 1997; Kramer et al., 2000). It is widely assumed that the destruction of APC/C targets in metaphase and anaphase is regulated by Cdc20, while in late mitosis and early G1 APC/C is associated to and activated by Cdh1 (Kramer et al., 2000). APC/CCdc20 recognizes destruction box (D-box)-containing proteins (King et al., 1996), while APC/CCdh1 recognizes proteins containing either a D-box or a KEN-box motif (Petersen et al., 2000; Pfleger and Kirschner, 2000; Pfleger et al., 2001).

Recruitment of substrates to the SCF complex occurs via a protein-binding domain within the F-box protein subunit. At least three classes of F-box proteins have been described, depending upon the presence of WD-40, leucine-rich repeats or other protein-binding domains (Cenciarelli et al., 1999; Winston et al., 1999). F-box proteins interact via the F-box motif with the Skp1 subunit, which can bridge the F-box to the cullin (Patton et al., 1998), which in turn serves as a scaffold to bring the RING finger protein to the substrate (Tan et al., 1999). Specificity of SCF interaction with substrates is due to F-box protein recruitment and is generally mediated by phosphorylation events on target proteins (Jackson et al., 2000; Harper, 2002).

We decided to investigate whether APC and SCF may play a role in the degradation of Cdc25 A. Here, we demonstrate that human Cdc25 A is a late mitotic target of the APC/CCdh1 and that its recognition by the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex relies upon the presence of a KEN-box motif. Nevertheless, Cdc25 A KEN mutant is still unstable throughout interphase and upon DNA damage. We demonstrate that the abundance of the protein can be affected by overexpressing a mutated Cul1 protein that fails to interact with Roc1 and UBC proteins. Moreover, we detected Cul1 and Skp1 in Cdc25 A immunocomplexes, thus providing evidence that SCF may be involved in Cdc25 A degradation. In addition to being an APC/C target, Cdc25 A might therefore either be a substrate of SCF or be degraded through a mechanism that itself depends on SCF.

Results

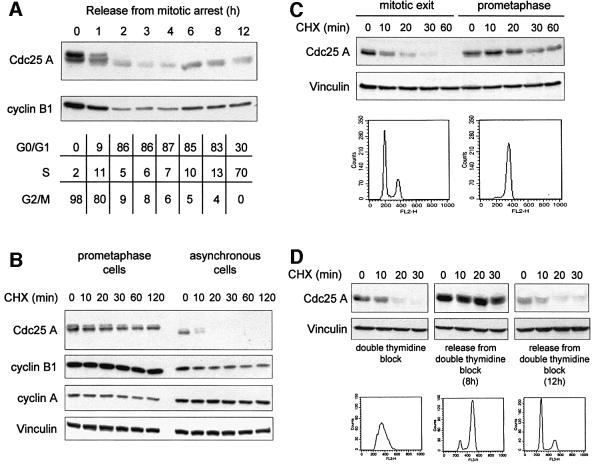

Cdc25 A stabilization in mitotic cells

We have previously shown that in human cells the levels of Cdc25 A are periodically regulated in the cell cycle with a continuous increase in abundance from late G1 until mitosis (Molinari et al., 2000). In Figure 1A, we show that Cdc25 A levels rapidly decreased as HeLa cells were released into the cell cycle from a nocodazole-induced metaphase arrest. The protein became rapidly undetectable, to be induced again as cells approached the next S-phase. Decrease in Cdc25 A is evident before completion of mitosis and cytokinesis as assessed by flow cytometry, and paralleled that of cyclin B1. To assess whether the accumulation of Cdc25 A in prometaphase cells was due to a stabilization of the protein, we tested whether its half-life was increased in nocodazole-arrested cells compared with an asynchronous cell population (Figure 1B). Prometaphase cells, obtained by a 16-h nocodazole treatment, were incubated further with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide and followed over a period of 120 min in parallel with an asynchronous cell population (Figure 1B). Furthermore, to address the question of whether the reduction in the quantity of Cdc25 A upon release from mitotic arrest was due to a decrease in protein stability, we compared the half-life of the protein in cells upon nocodazole arrest and upon mitotic exit (Figure 1C). A cell population enriched in early G1-phase was obtained by releasing prometaphase nocodazole-arrested cells in fresh medium for 1 h, and analyzed for protein stability by treatment with cycloheximide over a period of 60 min (Figure 1C). Both in asynchronously growing cells and in cells exiting mitosis, Cdc25 A was unstable, with an estimated half-life of <10 min. In prometaphase-arrested cells, on the other hand, the half-life of Cdc25 A was clearly prolonged (Figure 1B and C). Expression levels of cyclin B1 and cyclin A were followed in prometaphase and in asynchronous cells, and are shown in Figure 1B. Cyclin A levels were higher in asynchronous cells compared with prometaphase-arrested cells, while cyclin B1 behaved in the opposite way, thus suggesting that during mitosis Cdc25 A, like cyclin B1, is degraded later than cyclin A, and after the transition from metaphase to anaphase (see Clute and Pines, 1999; Geley et al., 2001).

Fig. 1. Cdc25 A is degraded in late mitosis and G1-phase. (A) Extracts were prepared from HeLa cells released from a metaphase arrest by nocodazole treatment and harvested at the indicated time points (h). Samples were analyzed to detect endogenous levels of Cdc25 A and cyclin B1 by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. The cell cycle profile of the different samples was determined by flow cytometry and reported in the table as percentage of cells in different phases. (B) The protein stability of Cdc25 A was analyzed in prometaphase cells (nocodazole-arrested) and in asynchronous cells by treatment with cycloheximide for the indicated time points (min). (C) Cells were synchronized by nocodazole treatment and then plated in fresh medium for 1 h or kept in nocodazole-containing medium. Protein stability of Cdc25 A was analyzed in cells synchronized in metaphase and upon mitotic exit by treatment with cycloheximide for the indicated time points (min). Cell cycle profiles were determined by flow cytometry analysis of DNA content. (D) Cells were synchronized in early S-phase by double thymidine treatment (left panel), and in G2/M (middle panel) and G1-phase (right panel) by releasing cells in fresh medium for 8 and 12 h, respectively. Protein stability was assessed by treatment with cycloheximide for the indicated time points (min). Extracts were analyzed by immunodetection of endogenous Cdc25 A, cyclin B1 and cyclin A using specific antibodies. Vinculin detection was used to normalize for equal gel loading.

Data obtained with nocodazole-arrested cells were confirmed by an alternative strategy of cell synchroniz ation (Figure 1D). HeLa cells were arrested in early S-phase by double thymidine treatment and released for 8 and 12 h into next G2- and G1-phases, respectively. Cells were analyzed further for Cdc25 A stability by treatment with cycloheximide for the indicated times (in minutes). A cell population enriched in G2-phase (Figure 1D, middle panel) showed an increased steady-state level of Cdc25 A compared with early S-phase (left panel) and G1-phase cells (right panel, compare ‘0’ time points). Moreover, no significant degradation of Cdc25 A was observed in G2, whereas a very rapid turnover of Cdc25 A was evident in early S- and G1-phases. Altogether, these observations suggest that degradation of Cdc25 A, in cells that exit mitosis and in early G1, is compatible with an involvement of the APC/C complex.

Cdc25 A degradation is APC/CCdh1 dependent

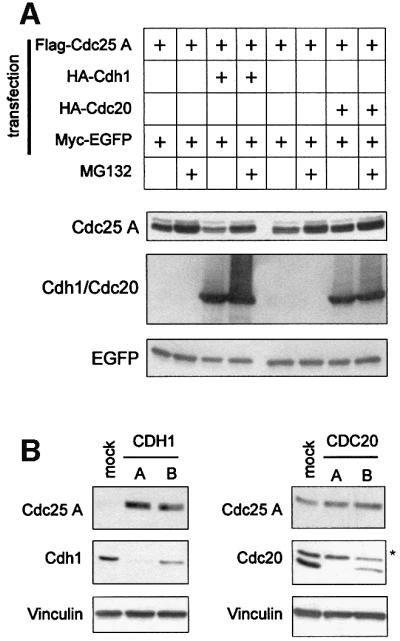

The fact that oscillations in Cdc25 A levels parallel those in cyclin B1 suggests that Cdc25 A, like cyclin B1, may be degraded by the APC. To assess which activator of the APC/C might be involved in Cdc25 A degradation, we transfected asynchronous cells with wild-type Cdc25 A, along with either Cdh1 or Cdc20, and tested whether this affected Cdc25 A accumulation (Figure 2A). We noticed that Cdh1, but not Cdc20 overexpression, resulted in a significant decrease in the steady-state level of the protein. The decrease in the amount of Cdc25 A induced by Cdh1 was prevented by the addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG132, suggesting that Cdh1-dependent degradation of Cdc25 A occurs through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway and that Cdh1 expression might be rate limiting for the degradation of Cdc25 A. It should be mentioned that this phenomenon does not reflect an indirect effect on cell cycle position, since neither Cdh1 nor Cdc20 overexpression caused major changes in cell cycle distribution over the course of transient transfection (not shown).

Fig. 2. Cdc25 A is targeted for degradation by Cdh1 in vivo. (A) Extracts were prepared from HeLa cells transfected with plasmids expressing Flag-Cdc25 A and either HA-Cdh1 or HA-Cdc20 together with Myc-tagged EGFP as a control for transfection efficiency and gel loading. Where indicated, cells were treated with MG132 for 6 h before harvesting. Flag-Cdc25 A, HA-Cdh1 or HA-Cdc20 and Myc-EGFP were detected by immunoblotting using anti-Flag, anti-HA and anti-Myc antibodies, respectively. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with CDH1- and CDC20-specific siRNAs as reported in Materials and methods. Mock lane corresponds to cells transfected with Oligofectamine alone, and A and B lanes refer to cells transfected with Oligofectamine along with dsRNAs corresponding to different regions of either CDH1 or CDC20 gene sequences. Extracts were analysed by immunodetection of endogenous Cdc25 A, Cdh1 and Cdc20 using specific antibodies. Vinculin immunodetection was shown to normalize for equal gel loading. The asterisk indicates an unspecific band.

To test further the hypothesis that Cdh1 is required for the degradation of Cdc25 A, we attempted to inhibit the endogenous expression of either Cdh1 or Cdc20 by transfecting HeLa cells with small interfering dsRNAs corresponding to different portions of either the CDH1 or the CDC20 gene (Elbashir et al., 2001). Transfection with two distinct siRNAs directed at CDH1 resulted in reduced amounts of the protein and increased levels of endogenous Cdc25 A (Figure 2B). Even a limited decrease of Cdh1 levels (oligo B) correlated with accumulation of Cdc25 A (Figure 2B). In contrast, inhibition of CDC20 expression did not correlate with Cdc25 A accumulation, thus confirming that Cdh1 is specifically required for Cdc25 A degradation.

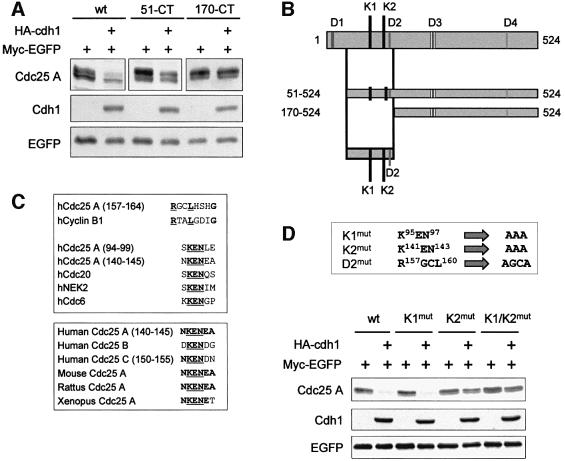

APC/CCdh1-mediated degradation of Cdc25 A requires an intact KEN-box motif

A preliminary analysis of the stability of Cdc25 A deletion mutants indicated that a region between amino acids 51 and 170 was required for the degradation of the protein induced by Cdh1 (Figure 3A). Given the high specificity of substrate recognition by APC/C complexes, we searched for the presence of sequence motifs known to target proteins to either Cdc20 or Cdh1: a nine amino acid D-box, first identified in cyclin B1 (Glotzer et al., 1991), and a KEN-box, responsible for the destruction of the APC/C regulator Cdc20 (Pfleger and Kirschner, 2000). By alignment with known destruction motifs of APC/C target proteins, we identified one putative D-box (RXXL motif) and two KEN-box motifs (Figure 3B and C, upper panel) in the region between amino acids 51 and 170. Interestingly, the region containing the KEN2 motif is conserved among Cdc25 family proteins of different species (Figure 3C, lower panel) and, most importantly, this same motif is involved in the degradation of Cdc25 C induced by arsenite (Chen et al., 2002). We mutated these motifs individually or in combination (Figure 3D) and assessed whether comparable amounts of recombinant proteins were equally sensitive to Cdh1 overexpression. Among the generated mutants, the KEN2-mutated Cdc25 A was less sensitive to the presence of overexpressed Cdh1 and this phenomenon was observed also for the double KEN1/KEN2 mutant (Figure 3D).

Fig. 3. APC/CCdh1 requires an intact KEN2-box motif to target Cdc25 A for in vivo degradation. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids encoding Flag-tagged version of the full-length and the indicated deletion mutants of Cdc25 A, together with plasmids expressing HA-Cdh1 and Myc-tagged EGFP as a control for transfection efficiency and gel loading. Expression of Flag-proteins, HA-Cdh1 and Myc-EGFP were detected by immunoblotting using anti-Flag, anti-HA and anti-Myc antibodies, respectively. (B) Schematic diagram of the full-length and the deletion mutant versions of Cdc25 A, indicating putative destruction D- and KEN-box sequences. (C) Alignment of human Cdc25 A amino acid regions corresponding to putative destruction D- and KEN-box sequences with destruction motifs identified in known target proteins (upper panel); alignment of human Cdc25 A KEN-box sequences among Cdc25 family proteins (lower panel); (D) Schematic representation of mutants in two KEN-boxes and one putative D-box motif of Cdc25 A generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Extracts were prepared from HeLa cells transfected with plasmids expressing either wild-type Flag-Cdc25 A or point mutants of Cdc25 A (K1mut, K2mut, K1/K2mut) with or without a plasmid encoding HA-tagged Cdh1. Flag-Cdc25 A proteins, HA-Cdh1 and Myc-EGFP were detected by immunoblotting using specific antibodies.

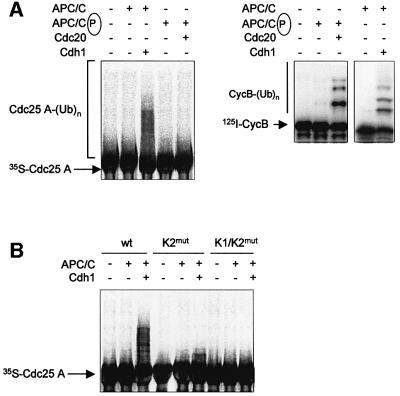

Cdc25 A is ubiquitylated by APC/CCdh1 in vitro

To assess whether Cdc25 A is a substrate of the APC/C ligase, in vitro ubiquitylation assays, using purified cyclosome from HeLa cells and recombinant Cdh1 or Cdc20 proteins, were performed (Golan et al., 2002). As shown in Figure 4A (left panel), Cdc25 A was polyubiquitylated by dephosphorylated APC/C in the presence of Cdh1, but not by phosphorylated APC/C activated by Cdc20. As a control, the cyclosome preparations were tested for ubiquitin ligase activity on a 125I-labeled N-terminal fragment of cyclin B and results are shown in Figure 4A (right panel). In line with the findings described in Figure 3, the KEN2 and the double KEN1/KEN2 mutants of Cdc25 A were not ubiquitylated in vitro, thus confirming that Cdc25 A is a specific substrate of the APC/CCdh1 ligase (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4. Cdc25 A is ubiquitylated by APC/CCdh1 in vitro. (A) Ubiquitin ligation was detected on in vitro-translated 35S-wild-type Cdc25 A in the presence of purified cyclosome as described in Materials and methods. Reactions were performed in the presence of recombinant purified His6-tagged Cdh1 or Cdc20. The ubiquitin ligase activities of the preparations used in the left panel were tested on a 125I-labeled N-terminal fragment of cyclin B and are shown in the right panel. (B) In vitro-translated wild-type, K2mut and K1/K2mut were tested for APC/CCdh1-dependent ubiquitylation as described in (A).

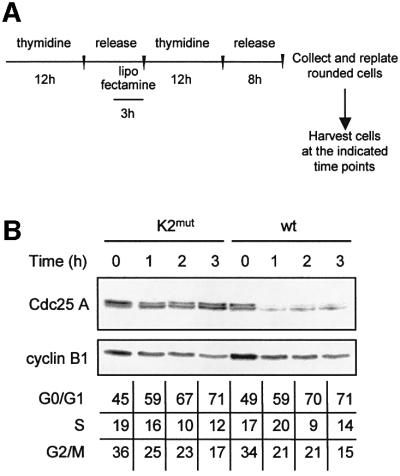

The KEN2 motif is required for APC/CCdh1-dependent degradation upon exit from mitosis

We next assayed the stability of wild-type and KEN2-mutated Cdc25 A during mitotic exit and in early G1-phase, stages of the cell cycle at which APC/CCdh1 is active. Cells transfected with constructs encoding the wild-type or the KEN2-mutated proteins were enriched in G2-phase according to the experimental scheme illustrated in Figure 5A. A fraction enriched in rounded, mitotic cells was released into the cell cycle and samples were collected at different time points. The levels of Cdc25 A were monitored by immunoblotting with an anti-Flag antibody. The KEN2 mutant was resistant to degradation under conditions in which both wild-type Cdc25 A and cyclin B1 were rapidly degraded (Figure 5B). These results confirmed that Cdc25 A is degraded upon exit from mitosis in an APC/CCdh1-dependent fashion.

Fig. 5. K2mut is resistant to degradation at the exit from mitosis. (A) Scheme of the protocol applied to HeLa cells to obtain a transfected population released into the cell cycle after a partial synchronization in G2/M. Cells were enriched in early S-phase by a thymidine-treatment (12 h). During the last 3 h of the release period in drug-free medium (8 h), cells were transfected with lipofectamine and treated further with thymidine for 12 h. An 8-h release period in drug-free medium followed S-phase synchronization. When most of the cells detached from the plate with a rounded phenotype, indicating a G2/M enrichment, they were harvested and re-plated to be collected at the indicated time points. (B) Extracts were prepared from cells transfected either with Flag-tagged wild-type or K2mut Cdc25 A proteins according to the scheme shown in (A). Flag-Cdc25 A and cyclin B1 were detected by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-cyclin B1 antibodies, respectively. Cell cycle profiles were determined by flow cytometry and reported in the table as percentages of cells in different phases.

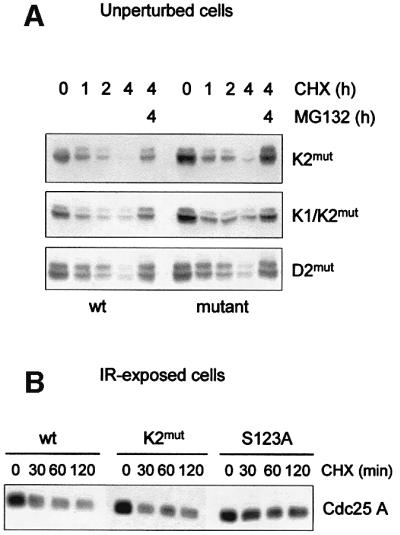

We noticed that while the KEN2-mutated Cdc25 A was stable in cells exiting mitosis, it remained intrinsically unstable in interphase cells. We transfected asynchronous cells with plasmids encoding wild-type, KEN2-, double KEN1/KEN2- and DEX2-mutated Cdc25 A to assess their protein stability. All recombinant proteins were rapidly degraded upon cycloheximide treatment and the addition of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 prevented this effect (Figure 6A). This observation suggests that a ubiquitin– proteasome pathway independent from the APC/CCdh1 may be responsible for the rapid turnover of Cdc25 A during interphase.

Fig. 6. K2mut remains intrinsically unstable in interphase cells and IR-exposed cells. (A) Cells were transfected with equal amounts of Flag-tagged Cdc25 A, K2mut, K1/K2mut or D2mut. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit protein synthesis and then harvested at the indicated time points. Where indicated, cells were treated with MG132 for the last hours of treatment. (B) Cells were transfected with Flag-tagged Cdc25 A, K2mut and S123A mutants. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were exposed to 10 Gy, and 1 h after irradiation were treated with cycloheximide for the indicated time points. Ectopic expression levels of wild-type and mutated proteins of Cdc25 A were detected by immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibody.

As demonstrated by Falck et al. (2001), wild-type Cdc25 A undergoes ionizing radiation (IR)-induced degradation that is partially rescued by substitution of Ser123 with Ala, thus indicating that phosphorylation of Cdc25 A on Ser123 may represent a signal for rapid destruction of the protein upon DNA damage. We reasoned that if the KEN motif is involved in IR-induced degradation of Cdc25 A, its mutation may result in increased protein stability upon IR exposure. We transfected asynchronous cells with plasmids encoding wild-type, KEN2- and S123A-mutated proteins, and assessed their stability upon IR-induced DNA damage. As shown in Figure 6B, both wild-type and KEN2-mutated proteins were affected in a comparable fashion by IR exposure, while the degradation of the control S123A-mutated protein was substantially delayed.

The SCF complex is involved in Cdc25 A degradation

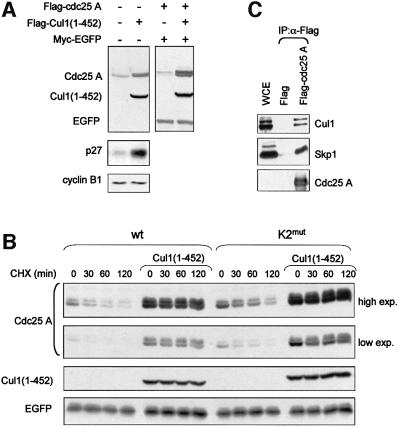

Degradation mechanisms other than those dependent upon the APC/C complex might therefore be responsible for the rapid turnover of Cdc25 A during interphase and IR-induced DNA damage. The SCF E3 ubiquitin ligases, which are also responsible for degradation of cell cycle regulators, are good candidates. To test the possible involvement of SCF in mediating Cdc25 A degradation in interphase, we made use of an N-terminal Cul1 mutant, Cul1(1–452) that interferes with the degradation of SCF substrates (Wu et al., 2000). The Cul1 mutant lacks the Roc1/UBC binding region, and whilst retaining its ability to bind to F-box proteins through Skp1 prevents substrates from being ubiquitylated and subsequently degraded. Upon Flag-Cul1(1–452) expression, both the endogenous Cdc25 A and the protein expressed upon transient transfection substantially increased in abundance (Figure 7A). The same was observed for p27, a known substrate of the SCFSkp2 complex (Carrano et al., 1999), but not for cyclin B1, a substrate of APC/C. These observations underlie the specificity of action of Cul1 and rule out the possibility that Cul1(1–452) interferes with the function of the APC/C complex.

Fig. 7. Cul1(1–452) induces accumulation and stabilization of Cdc25 A. (A) Extracts were prepared from cells transfected with Flag-tagged Cul1(1–452) with or without Flag-Cdc25 A, together with Myc-tagged EGFP as a control for transfection efficiency and gel loading. Flag-Cdc25 A, Flag-Cul1(1–452) and Myc-EGFP were detected with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. Endogenous Cdc25 A, p27 and cyclin B1 were detected by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. (B) Cells were transfected either with Flag-tagged wild-type Cdc25 A or K2mut with or without a plasmid encoding Flag-tagged Cul1(1–452), together with Myc-tagged EGFP as a control for transfection efficiency and gel loading. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide and harvested at the indicated time points. Flag-tagged wild-type and mutant Cdc25 A, Flag-Cul1(1–452) and Myc-EGFP were detected by immunoblotting using anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. Both a low and a high exposure of the film were included in the picture to allow comparison between different signals. (C) Cdc25 A interacts with components of the SCF complex in vivo. Extracts were prepared from HeLa cells transfected with Flag-Cdc25 A. Flag-tagged Cdc25 A was immunoprecipitated using the anti-Flag affinity gel (Sigma), subjected to SDS–PAGE, and immunoblotted using antibodies specific for Cul1 and Skp1. A cell extract aliquot (WCE) was included in the blot.

The accumulation of transfected Cdc25 A upon Cul1(1–452) overexpression was the result of protein stabilization as shown by cycloheximide addition (Figure 7B). The effect of Cul1(1–452) overexpression was observed even on the KEN2-mutated protein, thus allowing us to conclude that protein signatures other than the KEN-box motif are likely to be involved in the degradation of Cdc25 A during interphase. To substantiate this finding further, we assayed whether known members of SCF complexes could interact with Cdc25 A. Both Cul1 and Skp1 were identified in Cdc25 A immunoprecipitations, a result that demonstrated the existence of a physical interaction between members of the SCF complex and Cdc25 A (Figure 7C).

Discussion

In previous work we demonstrated that the Cdc25 A phosphatase is rapidly degraded when cells are treated with hydroxyurea or other DNA synthesis inhibitors. We could demonstrate that Cdc25 A is ubiquitylated and degraded via the proteasome pathway and that its half-life is severely shortened in response to a block in DNA synthesis (Molinari et al., 2000). Similar results were obtained by Mailand et al. (2000), who showed that Cdc25 A disappears in response to DNA damage and that failure to degrade Cdc25 A results in unscheduled DNA synthesis (Falck et al., 2001).

In this paper, we demonstrate that Cdc25 A is targeted for degradation by the APC/C ubiquitin ligase upon mitotic exit and that APC/C-dependent degradation of Cdc25 A requires a KEN-box motif. We also show that a KEN-box mutant of Cdc25 A remains unstable during interphase and upon DNA damage, and that interfering with SCF function appears to affect Cdc25 A degradation.

Cdc25 A is a late mitotic target of the APC/C complex

Cdc25 A protein accumulates from G1 until mitosis, to be degraded as cells enter the next cell cycle with similar kinetics to cyclin B1. The degradation of Cdc25 A is mediated by the APC/C complex. More specifically, Cdh1, an activator of APC/C (Pfleger and Kirschner, 2000), is rate limiting and is required for Cdc25 A regulation since its overexpression induces Cdc25 A degradation and its silencing results in Cdc25 A accumulation. The addition of a proteasome inhibitor to cells overexpressing Cdh1 prevents degradation of Cdc25 A, confirming that Cdc25 A is lost due to proteasome-dependent turnover rather than to inhibition of transcription or translation. Identification of a KEN-box motif in the N-terminal part of the protein provides confirmation that Cdc25 A is a substrate of the APC/CCdh1 complex both in vivo and in vitro. More specifically, we find that the KEN2-mutated protein is insensitive to degradation upon mitotic exit and in early G1, when the APC/CCdh1 complex is active (Kramer et al., 2000).

Biological role of Cdc25 A at mitosis

Until very recently it had been assumed that in mammalian cells, Cdc25 A was responsible solely for regulation of the cell cycle at the G1/S boundary, its primary substrate being the Cdk2 protein kinase (Hoffmann et al., 1994; Jinno et al., 1994; Blomberg and Hoffmann, 1999). Since these experiments were performed in serum-starved cells that were released into the cycle from quiescence, by design they did not address the possible role of Cdc25 A in cell-cycle transitions occurring beyond G1/S phase. Previous findings had indeed shown that microinjection of anti-Cdc25 A antibodies in HeLa cells blocked cell division and resulted in the accumulation of cells with a mitotic-like phenotype (Galaktionov and Beach, 1991). On the contrary, it is well proven that Cdc25 B and Cdc25 C cooperate with a concerted action at the G2/M phase transition, their main substrate being the mitotic kinase Cdc2/cyclin B (Gabrielli et al., 1996; Karlsson et al., 1999).

Previous observations reporting the nuclear accumulation of Cdc25 A, and recent findings of an increase in abundance of the protein in G2 and M (this paper and Molinari et al., 2000), raise the possibility that Cdc25 A may play a role in mitosis. These data should help our understanding of how mitosis could be triggered by a protein like Cdc25 C, whose localization is primarily cytoplasmic and that is poorly active unless phosphorylated by Cdc2/cyclin B (Heald et al., 1993). Recent findings demonstrate that Cdc25 C shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm in a cell cycle-dependent manner, and that this mechanism may be required for a correct timing of mitotic induction (Takizawa and Morgan, 2000). Yet, contrary to Cdc25 A and Cdc25 B, the Cdc25 C protein is detected at constant levels through the cell cycle (Gabrielli et al., 1996). Our hypothesis is that Cdc25 A could act in a concerted manner with Cdc25 C and Cdc25 B to induce mitosis (Karlsson et al., 1999). The existence of multiple control mechanisms that cooperate in preventing unscheduled mitosis is also suggested by the finding that overexpression of Cdc25 C does not completely override a DNA replication checkpoint (Karlsson et al., 1999). On the contrary, in our previous work we showed that Cdc25 A overexpression can induce chromosome condensation and activation of mitotic events even in the presence of a DNA replication block (Molinari et al., 2000). Work published by Heald et al. (1993) supported the notion that continued activation of the Wee1 protein kinase in interphase contributes to protect the nucleus from untimely initiation of mitotic events by Cdc25 phosphatase. While at that time it was thought that Cdc25 C was the only ‘mitotic phosphatase’, the model proposed is still fully valid. Accumulation of Cdc25 A over time and up to a threshold level could very well represent the critical event required for triggering mitosis. The additional contribution of Cdc25 B and C could be required for signal amplification or by the need to target specific subcellular loci.

Interphase degradation of Cdc25 A

The observation that Cdc25 A remains almost undetectable until cells enter S-phase, and evidence that Cdc25 A is a target of the DNA damage-dependent intra-S-phase checkpoint (Falck et al., 2002), suggest that in addition to the mitosis specific APC/C complex, other ubiquitin ligases may be responsible for its constitutive and induced degradation. Since the KEN2-mutated form of Cdc25 A is still unstable in interphase and in cells exposed to ionizing radiation, signal(s) other than the KEN2-box must be involved in these alternative pathways for Cdc25 A degradation. A good candidate E3 ubiquitin ligase is SCF, because of its involvement in multiple pathways (Koepp et al., 1999; Harper, 2002).

Here we show that a dominant-negative mutant version of the Cul1 subunit, lacking the Roc1/UBC binding region (Wu et al., 2000), is able to accumulate and stabilize Cdc25 A, possibly by sequestering the protein in a complex containing Skp1 and an unknown F-box protein. p27, a well known target of the SCF complex (Carrano et al., 1999), also accumulates upon Cul1 mutant transfection. On the contrary, cyclin B1, a typical target of the APC/C complex, remains unaffected, thus confirming the specificity of action of the Cul1 mutant. The existence of in vivo interactions between components of the SCF complex and Cdc25 A provides evidence that SCF is involved in Cdc25 A degradation, either directly or indirectly, perhaps through activation of a distinct ubiquitin ligase. We assume that the increase in Cdc25 A abundance upon transfection of the Cul1 mutant is due to the decreased rate of its degradation in interphase cells, and we have preliminary evidence that cells expressing the Cul1 mutant also fail to degrade Cdc25 A upon exposure to ionizing radiation. Yet, at present we cannot formally prove that a specific SCF ubiquitin ligase is responsible for Cdc25 A degradation, either in unperturbed or in perturbed cells.

Tight regulation of Cdc25 A abundance

We hypothesize that the intrinsic instability of Cdc25 A allows for tight regulation of cell progression through the cycle, by providing an emergency mechanism for immediate checkpoint activation. Mailand et al. (2000) demonstrated that DNA damaging events are able to immediately block cell cycle progression by inducing rapid degradation of Cdc25 A. Similarly, we have shown that a block in DNA replication will immediately trigger the inactivation of Cdc25 A with a rapid increase in Cdk2 tyrosine phosphorylation (Molinari et al., 2000). Induction of Cdc25 A degradation, and consequent inhibition of Cdk2 activity, are events required to prevent DNA replication in the presence of DNA strand breaks or stalled replication, and to allow efficient DNA repair. Interference with these pathways abolishes checkpoint activation and may lead to genome instability (Mailand et al., 2000; Molinari et al., 2000; Falck et al., 2001).

We have now demonstrated that two ubiquitin ligase complexes are involved in controlling the abundance of Cdc25 A. A failure to downregulate the levels of Cdc25 A may result in a delay in cell cycle checkpoint activation and could explain how Cdc25 A overexpression in cancer might contribute to genomic instability. The recent finding that cyclin E overexpression in human tumors is linked to a defect in an SCF-mediated degradation pathway is in line with this concept (Koepp et al., 2001).

Further work will be required to test whether SCF- or APC-dependent mechanisms are involved in inducing Cdc25 A degradation in response to checkpoint(s) activation. Falck et al. (2001) have shown that Cdc25 A-S123A, a mutant protein that cannot be phosphorylated at Ser123 by the Chk2 protein kinase, undergoes a delayed degradation in response to ionizing radiation. This finding might suggest the existence of an F-box protein that selectively recognizes and binds to phosphorylated Cdc25 A at Ser123 under DNA damage, thus accelerating protein ubiquitylation and degradation. Nevertheless, the possible involvement of APC/C ubiquitin ligase cannot be completely excluded. Sudo et al. (2001) demonstrated that APC/CCdh1 is activated in response to a G2-phase arrest induced by ionizing radiation. Moreover, recent findings reported that arsenite-induced G2/M-phase cell cycle arrest is mediated by degradation of Cdc25 C through activation of an APC/C-dependent mechanism (Chen et al., 2002). We are currently investigating the possibility that either APC/C, perhaps through a mechanism different from the one operating at mitotic exit, or SCF mediate the effects of checkpoint activation through induction of Cdc25 A degradation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, cell synchronizations and treatments

HeLa cells were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Euroclone) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (Hyclone) and 2 mM l-glutamine (Euroclone). The following protocols were used to obtain HeLa cells arrested at specific stages of the cell cycle. Cells were synchronized in metaphase by treatment with 0.05 µg/ml nocodazole for 16 h. Rounded cells were collected by gentle pipetting and released from drug-induced cell cycle block by washing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and replating in drug-free medium. Cells were collected at different time points up to 12 h. Cells were synchronized in early S-phase by double thymidine treatment (2 mM) for 12 h, and released in drug-free medium for 8 and 12 h. Cell cycle position was monitored by flow cytometry.

To inhibit protein synthesis, cells were cultured in the presence of 10 µg/ml cycloheximide for the indicated time points. Inhibition of protein synthesis in metaphase-arrested cells was achieved as follows: cells were treated with 0.05 µg/ml nocodazole for 16 h, and rounded cells were collected by gentle pipetting and cultured further with 0.05 µg/ml nocodazole and 10 µg/ml cycloheximide for up to 120 min. Inhibition of protein synthesis in cells exiting mitosis was achieved as follows: nocodazole-arrested cells were released in drug-free medium for 1 h and cultured further with 10 µg/ml cycloheximide for up to 60 min.

To obtain transfected metaphase HeLa cells, the cells were first cultured with 2 mM thymidine for 12 h, released from thymidine-induced early S-phase arrest by washing three times with PBS, and re-fed with fresh medium for up to 8 h. Cells were transfected with lipofectamine during the last 3 h of release before being further cultured with 2 mM thymidine for 12 h. Lipofectamine-transfected cells were released in drug-free medium until rounded cells detached from the plate. Exit from mitosis and entry into G1 was achieved by re-plating rounded cells and harvesting them at various time points up to 3 h. Changes in cell cycle profile were monitored by flow cytometry. Inhibition of the proteasome-mediated degradation was observed by culturing cells for up to 6 h in the presence of 5 µM MG132 (Biomol).

Plasmids and transfections

Flag-tagged constructs encoding full-length or truncated versions of Cdc25 A were generated as follows: the full-length cDNA for Cdc25 A was obtained as a PCR product from pRC-CMV-Cdc25 A and cloned into the EcoRV restriction site of pCDNA3.1-FlagA; the 51-CT mutant was generated by PvuII–XhoI digestion of the full-length flagged construct and the insertion of the fragment into EcoRV–XhoI-digested FlagB-plasmid; and the 170-CT was produced by BglII–XhoI digestion of the full-length flagged construct and the insertion of the fragment into BamHI–XhoI-digested FlagB-plasmid. pCDNA3.1-Flag-Cdc25 A point mutants were generated using the QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The following amino acid changes were made: the KEN motifs at positions 95–97 and 141–143 were mutated into AAA, producing K1mut and K2mut, respectively; both KEN motifs were mutated into AAA in K1/K2mut; and in D2mut, the D-box motif RGCL at position 157–160 was changed into AGCA. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

The constructs pCMV-HA-Cdh1, pCMV-HA-Cdc20 and pCMV-Myc-EGFP were described previously (Petersen et al., 2000) and were provided by K.Helin. PCR3.1-Flag-Cul1(1–452) has been provided by Z.-Q.Pan (Wu et al., 2000).

Cells were transiently transfected using calcium phosphate co-precipitation and harvested 24 h post-transfection. To monitor for transfection efficiency and protein loading, 1 µg of pCMV-Myc-EGFP was included in each transfection. Where indicated, cells were transfected with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA interference

RNA interference was performed essentially as described previously (Elbashir et al., 2001). Single-strand oligos (20 µM; Dharmacon research, Inc.) were incubated in annealing buffer for 1 min at 90°C followed by 1 h at 37°C. Transfection of siRNAs for targeting endogenous genes was carried out using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) and cell extracts assayed for gene silencing 24 h after transfection. For CDH1 siRNA, oligo A corresponded to nucleotide sequence 5′-AATGAGA AGTCTCCCAGTCAG-3′ and oligo B to sequence 5′-AATCTGGTG GACTGGTCGTCC-3′. For CDC20 siRNA, oligo A corresponded to nucleotide sequence 5′-AAACCTGGCGGTGACCGCTAT-3′ and oligo B to sequence 5′-AATGTGTGGCCTAGTGCTCCT-3′.

Cell extraction and immunoblot analysis

Samples harvested at various time points were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycolate, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol) supplemented with 1 µg/ml aprotinin, 1 µg/ml leupeptin and 10 mM PMSF, and incubated on ice for 15 min. Samples were assayed for protein concentration using the Bradford method. Equal amounts of samples were resolved by SDS–PAGE and proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% dry non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies and subsequently with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pharmacia) on autoradiography films. For co-immunoprecipitation analysis, cells were transfected with 10 µg of pCDNA-Flag-cdc25 A. Supernatants derived from lysed cells were incubated with the anti-Flag affinity gel (M2, Sigma) for 2 h at 4°C. The resin was washed five times with lysis buffer, resuspended with Laemli buffer, boiled, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting as described previously (Molinari et al., 2000).

The following antibodies were used: anti-Cdc25 A (F6; Santa Cruz); anti-Flag (M2; Sigma); anti-cyclin B1 (GNS1; Santa Cruz); anti-cyclin A (H-432; Santa Cruz); anti-Myc (9E10; Santa Cruz); anti-HA (12CA5; Babco); anti-vinculin (Sigma); anti-Cullin (Zymed); and anti-Skp1 (H-163; Santa Cruz). Anti-Cdh1 and anti-Cdc20 monoclonal antibodies were provided by K.Helin.

In vitro ubiquitylation assay

Ubiquitin ligation was determined essentially as reported by Golan et al. (2002), except that the 125I-labeled N-terminal fragment of cyclin B was replaced by 35S-labeled, in vitro-translated Cdc25 A. Preparations of APC/C that were either phosphorylated or not were obtained from HeLa cells as described previously, and 1 µl was used for the in vitro ubiquitylation reaction. His6-tagged Cdh1 and Cdc20 were produced by infection of Sf9 insect cells with baculovirus expressing the corresponding proteins, and purified by nickel–agarose chromatography. Where indicated, Cdh1 or Cdc20 was supplemented at 1 µM.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Kristian Helin for providing Cdh1 and Cdc20 encoding plasmids and antibodies, and Zhen-Qiang Pan for providing the pCR3.1-Flag-Cul1(1–452) plasmid. We acknowledge Simona Ronzoni for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. We gratefully acknowledge Marina Melixetian for helpful discussions and Andrea Musacchio for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01-CA76584 and R01-GM57587) to M.P. and by grants from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (FIRC) and Telethon to G.F.D. M.P. is a recipient of the Irma T.Hirschl Scholarship. M.D. and M.S. were supported by fellowships from the FIRC.

References

- Blasina A., Paegle,E.S. and McGowan,C.H. (1997) The role of inhibitory phosphorylation of CDC2 following DNA replication block and radiation-induced damage in human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 1013–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg I. and Hoffmann,I. (1999) Ectopic expression of Cdc25A accelerates the G1/S transition and leads to premature activation of cyclin E- and cyclin A-dependent kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 6183–6194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrano A.C., Eytan,E., Hershko,A. and Pagano,M. (1999) SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat. Cell Biol., 1, 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenciarelli C., Chiaur,D.S., Guardavaccaro,D., Parks,W., Vidal,M. and Pagano,M. (1999) Identification of a family of human F-box proteins. Curr. Biol., 9, 1177–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Zhang,Z., Bower,J., Lu,Y., Leonard,S.S., Ding,M., Castranova, V., Piwnica-Worms,H. and Shi,X. (2002) Arsenite-induced Cdc25C degradation is through the KEN-box and ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 1990–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clute P. and Pines,J. (1999) Temporal and spatial control of cyclin B1 destruction in metaphase. Nat. Cell Biol., 1, 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir S.M., Harborth,J., Lendeckel,W., Yalcin,A., Weber,K. and Tuschl,T. (2001) Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cell. Nature, 411, 494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falck J., Mailand,N., Syljuasen,R.G., Bartek,J. and Lukas,J. (2001) The ATM-Chk2-Cdc25A checkpoint pathway guards against radioresistant DNA synthesis. Nature, 410, 842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falck J., Petrini,J.H.J., Williams,B.R., Lukas,J. and Bartek,J. (2002) The DNA-damage-dependent intra S-phase checkpoint is regulated by parallel pathways. Nat. Genet., 30, 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli B.G., De Souza,C.P., Tonks,I.D., Clark,J.M., Hayward,N.K. and Ellem,K.A. (1996) Cytoplasmic accumulation of cdc25B phosphatase in mitosis triggers centrosomal microtubule nucleation in HeLa cells. J. Cell Sci., 109, 1081–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaktionov K. and Beach,D. (1991) Specific activation of cdc25 tyrosine phosphatases by B-type cyclins: evidence for multiple roles of mitotic cyclins. Cell, 67, 1181–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaktionov K., Lee,A.K., Eckstein,J., Draetta,G., Meckler,J., Loda,M. and Beach,D. (1995) CDC25 phosphatases as potential human oncogenes. Science, 269, 1575–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaktionov K., Chen,X. and Beach,D. (1996) Cdc25 cell-cycle phosphatase as a target of c-myc. Nature, 382, 511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparotto D., Maestro,R., Piccinin,S., Vukosavljevic,T., Barzan,L., Sulfaro,S. and Boiocchi,M. (1997) Overexpression of CDC25A and CDC25B in head and neck cancers. Cancer Res., 57, 2366–2368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geley S., Kramer,E., Gieffers,C., Gannon,J., Peters,J.M. and Hunt,T. (2001) Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome-dependent proteolysis of human cyclin A starts at the beginning of mitosis and is not subject to the spindle assembly checkpoint. J. Cell Biol., 153, 137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M., Murray,A.W. and Kirschner,M.W. (1991) Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature, 349, 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan A., Yudkovsky,Y. and Hershko,A. (2002) The cyclin-ubiquitin ligase activity of cyclosome/APC is jointly activated by protein kinases Cdk1–cyclin B and Plk. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 15552–15557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J.W. (2002) A phosphorylation-driven ubiquitination switch for cell-cycle control. Trends Cell Biol., 12, 104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald R., McLoughlin,M. and McKeon,F. (1993) Human wee1 maintains mitotic timing by protecting the nucleus from cytoplasmically activated Cdc2 kinase. Cell, 74, 463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez S. et al. (1998) cdc25 cell cycle-activating phosphatases and c-myc expression in human non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Cancer Res., 58, 1762–1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A. (1997) Roles of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis in cell cycle control. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 9, 788–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M. (1996) Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu. Rev. Genet., 30, 405–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann I., Draetta,G. and Karsenti,E. (1994) Activation of the phosphatase activity of human cdc25A by a cdk2–cyclin E dependent phosphorylation at the G1/S transition. EMBO J., 13, 4302–4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson P.K., Eldridge,A.G., Freed,E., Furstenthal,L., Hsu,J.Y., Kaiser,B.K. and Reimann,J.D. (2000) The lore of the RINGs: substrate recognition and catalysis by ubiquitin ligases. Trends Cell Biol., 10, 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinno S., Suto,K., Nagata,A., Igarashi,M., Kanaoka,Y., Nojima,H. and Okayama,H. (1994) Cdc25A is a novel phosphatase functioning early in the cell cycle. EMBO J., 13, 1549–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson C., Katich,S., Hagting,A., Hoffmann,I. and Pines,J. (1999) Cdc25B and Cdc25C differ markedly in their properties as initiators of mitosis. J. Cell Biol., 146, 573–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King R.W., Glotzer,M. and Kirschner,M.W. (1996) Mutagenic analysis of the destruction signal of mitotic cyclins and structural characterization of ubiquitinated intermediates. Mol. Biol. Cell, 7, 1343–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp D.M., Harper,J.W. and Elledge,S.J. (1999) How the cyclin became a cyclin: regulated proteolysis in the cell cycle. Cell, 97, 431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp D.M., Schaefer,L.K., Ye,X., Keyomarsi,K., Chu,C., Harper,J.W. and Elledge,S.J. (2001) Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin E by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Science, 294, 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer E.R., Scheuringer,N., Podtelejnikov,A.V., Mann,M. and Peters,J.M. (2000) Mitotic regulation of the APC activator proteins CDC20 and CDH1. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 1555–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek W. and Nigg,E.A. (1991) Differential phosphorylation of vertebrate p34cdc2 kinase at the G1/S and G2/M transitions of the cell cycle: identification of major phosphorylation sites. EMBO J., 10, 305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand N., Falck,J., Lukas,C., Syljuasen,R.G., Welcker,M., Bartek,J. and Lukas,J. (2000) Rapid destruction of human Cdc25A in response to DNA damage. Science, 288, 1425–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M.E. and Cross,F.R. (2001) Cyclin specificity: how many wheels do you need on a unicycle? J. Cell Sci., 114, 1811–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari M., Mercurio,C., Dominguez,J., Goubin,F. and Draetta,G.F. (2000) Human Cdc25 A inactivation in response to S phase inhibition and its role in preventing premature mitosis. EMBO rep., 1, 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbury C., Blow,J. and Nurse,P. (1991) Regulatory phosphorylation of the p34cdc2 protein kinase in vertebrates. EMBO J., 10, 3321–3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton E.E., Willems,A.R. and Tyers,M. (1998) Combinatorial control in ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis: don’t Skp the F-box hypothesis. Trends Genet., 14, 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J.M. (1998) SCF and APC: the Yin and Yang of cell cycle regulated proteolysis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 10, 759–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen B.O. et al. (2000) Cell cycle- and cell growth-regulated proteolysis of mammalian CDC6 is dependent on APC-CDH1. Genes Dev., 14, 2330–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleger C.M. and Kirschner,M.W. (2000) The KEN box: an APC recognition signal distinct from the D box targeted by Cdh1. Genes Dev., 14, 655–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleger C.M., Lee,E. and Kirschner,M.W. (2001) Substrate recognition by the Cdc20 and Cdh1 components of the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes Dev., 15, 2396–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart C.M. (2001) Ubiquitin enters the new millennium. Mol. Cell, 8, 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadhu K., Reed,S.I., Richardson,H. and Russell,P. (1990) Human homolog of fission yeast cdc25 mitotic inducer is predominantly expressed in G2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 5139–5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr C.J. and Roberts,J.M. (1999) CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev., 13, 1501–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld U., Fernandez,A., Capony,J.P., Girard,F., Lautredou,N., Derancourt,J., Labbe,J.C. and Lamb,N.J. (1994) Activation of p34cdc2 protein kinase by microinjection of human cdc25C into mammalian cells. Requirement for prior phosphorylation of cdc25C by p34cdc2 on sites phosphorylated at mitosis. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 5989–6000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo T., Ota,Y., Kotani,S., Nakao,M., Takami,Y., Takeda,S. and Saya,H. (2001) Activation of Cdh1-dependent APC is required for G1 cell cycle arrest and DNA damage-induced G2 checkpoint in vertebrate cells. EMBO J., 20, 6499–6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa C.G. and Morgan,D.O. (2000) Control of mitosis by changes in the subcellular location of cyclin-B1–Cdk1 and Cdc25C. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P., Fuchs,S.Y., Chen,A., Wu,K., Gomez,C., Ronai,Z. and Pan,Z.Q. (1999) Recruitment of a ROC1-CUL1 ubiquitin ligase by Skp1 and HOS to catalyze the ubiquitination of IκBα. Mol. Cell, 3, 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigo E., Muller,H., Prosperini,E., Hateboer,G., Cartwright,P., Moroni,M.C. and Helin,K. (1999) CDC25A phosphatase is a target of E2F and is required for efficient E2F-induced S phase. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 6379–6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R., Prinz,S. and Amon,A. (1997) CDC20 and CDH1: a family of substrate-specific activators of APC-dependent proteolysis. Science, 278, 460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston J.T., Koepp,D.M., Zhu,C., Elledge,S.J. and Harper,J.W. (1999) A family of mammalian F-box proteins. Curr. Biol., 9, 1180–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K., Fuchs,S.Y., Chen,A., Tan,P., Gomez,C., Ronai,Z. and Pan,Z.Q. (2000) The SCF(HOS/β-TRCP)-ROC1 E3 ubiquitin ligase utilizes two distinct domains within CUL1 for substrate targeting and ubiquitin ligation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 1382–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Fan,Y.H., Kemp,B.L., Walsh,G. and Mao,L. (1998) Overexpression of cdc25A and cdc25B is frequent in primary non-small cell lung cancer but is not associated with overexpression of c-myc. Cancer Res., 58, 4082–4085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae W. and Nasmyth,K. (1999) Whose end is destruction: cell division and the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes Dev., 13, 2039–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]