Abstract

Background

Chronic and excessive alcohol consumption is a primary driver of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), a global health challenge with limited treatment options. Panax ginseng Meyer exhibits various pharmacological activities, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. However, its efficacy in preventing alcohol-induced liver injury remains limited, necessitating further optimization and investigation.

Methods

This study evaluated the hepatoprotective effects of Li-Ginseng Powder (LGP), a ginseng preparation enriched in rare ginsenosides, using a murine model of ALD and ethanol-exposed human hepatic L-02 cells. ALD was induced in C57BL/6 mice via daily oral ethanol administration (2400 mg/kg). Serum and liver biochemical markers were measured, and histological changes were assessed using H&E and Oil Red O staining. In vitro assays examined the effects of LGP on ethanol-metabolizing enzyme activity, oxidative stress, mitochondrial integrity, and autophagy.

Results

Ethanol exposure significantly elevated serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, low-density lipoprotein, and cholesterol, as well as hepatic triglycerides and malondialdehyde, while markedly decreasing hepatic levels of reduced glutathione and superoxide dismutase. LGP pre-treatment effectively reversed all these alterations, restored antioxidant capacity, and alleviated histological damage and lipid accumulation to near normal levels. In L-02 cells, LGP significantly enhanced alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase activities, facilitated ethanol and acetaldehyde detoxification, reduced reactive oxygen species levels, preserved mitochondrial membrane potential, and promoted autophagy.

Conclusion

LGP confers comprehensive hepatoprotection against alcohol-induced liver injury by significantly enhancing ethanol catabolism, enhancing antioxidant defenses, and activating autophagy. These findings suggest its therapeutic potential in the management of ALD.

Keywords: Li-Ginseng powder, Alcoholic liver injury, Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, Hepatoprotective effect, Autophagy

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), resulting from chronic and excessive alcohol consumption, remains a major global health challenge. It encompasses a pathological spectrum that progresses from simple steatosis to alcoholic hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ultimately hepatocellular carcinoma [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. ALD is responsible for over 25 % of liver-related mortality worldwide [1]. Epidemiological evidence indicates that alcohol intake increases the risk of liver-related death by approximately 260-fold, and also elevates the risks for cardiovascular disease and cancer by 3.2- and 5.1-fold, respectively [5]. The pathogenesis of ALD is multifactorial and intricately regulated, involving hepatocellular injury and regeneration, oxidative stress, inflammation, dysregulated lipid metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, and disturbances of the gut-liver axis [2,6,7]. Hepatic ethanol metabolism generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and toxic metabolites such as acetaldehyde, which induce mitochondrial damage and hepatocyte injury, thereby driving disease progression [8]. Despite advances in understanding the underlying mechanisms of ALD, there are currently no FDA-approved pharmacological therapies. Existing treatment strategies remain limited in efficacy and often carry significant adverse effects. For instance, corticosteroids offer little benefit in improving long-term outcomes in severe alcoholic hepatitis, while pentoxifylline has shown minimal efficacy in improving short-term survival [9].

In recent years, natural products and plant-derived extracts have attracted increasing attention for their potential therapeutic effects on liver diseases, particularly due to their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-steatotic properties [10]. P. ginseng, a traditional medicinal herb used for centuries in East Asia, has been shown to exhibit diverse pharmacological activities, including antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and cardioprotective effects [11]. Although several studies have shown that ginseng and its active components, ginsenosides, possess hepatoprotective effects against ALD, their efficacy and underlying mechanisms remain inadequately characterized [[12], [13], [14], [15]].

Li-Ginseng Powder (LGP) is a specially processed form of P. ginseng enriched in rare ginsenosides such as Rh4, Rg3, Rg5, Rk1, and Rk3, which collectively comprise about 60 % of its total saponin content—substantially higher than in Red Ginseng. Unlike individual ginsenosides, LGP retains the complete spectrum of ginseng bioactive components, including ginsenosides, polysaccharides, peptides, polyphenols, and flavonoids, thereby offering stronger efficacy without detectable adverse effects. This study aimed to evaluate the hepatoprotective effects of LGP against alcohol-induced liver injury using both in vivo and in vitro models. Our results demonstrated that LGP significantly attenuated alcohol-induced hepatic damage through multiple mechanisms, including upregulation of ethanol-metabolizing enzyme activity, enhancement of antioxidant defenses, improvement of mitochondrial function, and activation of autophagy. These findings suggest that LGP holds promise as a multi-targeted therapeutic agent for ALD, with favorable efficacy and safety profiles.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). RPMI 1640 medium and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco Company. LGP, a specially processed form of ginseng rich in rare ginsenosides, was provided by Yanbian Andi Kang Hua Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. Assay kits for Total Superoxide Dismutase (S0101S), ROS (S0033S) and enhanced mitochondrial membrane potential with JC-1 (C2006) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Assay kits for malondialdehyde (A003-1), triglyceride (A110-1-1) and reduced glutathione (A061-1) were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Assay kits for Alcohol Dehydrogenase (BC1080) and Acetaldehyde Dehydrogenase (BC0750) activity were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Acetaldehyde Content Assay Kit (BL1839A) was from Biosharp (Hefei, China). ADH1B (66939-1-Ig), ALDH2 (68237-1-Ig), GAPDH (60004-1-Ig), Beta Actin (66009-1-Ig), HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (SA00001-2) and HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (SA00001-1) antibodies were purchased from Proteintech (Rosemount, IL, United States). Antibodies for LC3A/B (F0144) and p62 (F0106) were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA). Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (4693124001) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (4906837001) were purchased from Roche (South San Francisco, CA, USA).

2.2. LGP and preparation of Li-ginseng ginsenoside fraction (LGG)

LGP provided by Yanbian Andi Kang Hua Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd. LGP was extracted with methanol, filtered, concentrated, and defatted with petroleum ether. The resulting aqueous solution was purified on an AB-8 macroporous resin column via water and 95 % ethanol elution, and the ethanol eluate was dried to obtain Li-Ginseng ginsenoside fraction (LGG).

2.3. HPLC analysis of LGG

High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis was performed on Waters 2695 Separation Module (Milford, MA) coupled with Waters 2489 UV/Vis detector HPLC systems running Empower Pro (Waters) software. The column, Acchrom Technologies Co., Ltd (Beijing, China) reversed phase Unitary C-18 column with 5 μm particle sizes, 4.6 × 250 mm internal diameter, was used. Column temperature was set at 35 °C and injection volume at 50 μL. The flow rate was set at 1 mL/min and detection wavelength at 203 nm. The mobile phases consisted of water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). HPLC solvent system was programmed as follows: 0 min, 20 % (B), 80 % (A); 20 min, 20 % (B), 80 % (A); 31 min, 32 % (B), 68 % (A); 40 min, 43 % (B), 57 % (A); 70 min, 100 % (B), 0 % (A).

2.4. Animal design

Male C57BL/6 mice (20 ± 2g, 4–6 week) were purchased from Changchun Yisi Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Changchun, China). All mice were housed at 20–25 °C and 50–60 % relative humidity with a 12 h light-dark cycle. All mice were randomly divided into four groups (6 mice/group), including control group (water for one month, daily, i.g.), alcohol model group (56 % Erguotou liquor from Day16 for 15 days, daily, i.g.), low-dose LGP group (12.5 mg/kg for one month, daily, i.g.) and high-dose LGP group (50 mg/kg for one month, daily, i.g.). 56 % Erguotou liquor was given after 4 h of LGP administration, once a day. All mice were weighed to adjust the injection volumes twice a week.

2.5. Cell culture and cell viability assay

L-02, the human normal hepatocyte, was cultured in 1640 supplemented with 10 % FBS, streptomycin (100 μg/mL) and penicillin (100 μg/mL) at 37 °C in humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2.

In vitro, cytotoxicity of alcohol against L-02 cells was measured using MTT assay. L-02 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate (1 × 104/well, 100 μL) and incubated for 24 h. L-02 cells were treated with different concentrations of 56 % Erguotou liquor (converted into ethanol as 0, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 500, 800, 1000 mM) for another 44 h and then incubated with MTT (5 mg/mL, 20 μL/well) for 4 h. Discarding the solution was followed by the addition of DMSO (150 μL/well). The absorbance was measured at 550 nm. Similarly, hepatoprotective effect of LGG against alcohol was measured. L-02 cells were treated with Erguotou liquor (200 mM) and LGG (0, 0.5, 1 μg/mL, respectively), while control group was treated with 1640 medium without FBS. Subsequent experiments were performed using above concentrations.

2.6. Biochemical analysis

After the last administration, all mice were fasted overnight and then anesthetized. The serum and liver of mice were collected at 24 h for detection of biochemical indexes. The serum was separated by centrifugation for 10 min (3000 rpm, 4 °C) and stored at −80 °C. The levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin (TBIL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and cholesterol (CHOL) in the serum were determined by CHINA-JAPAN UNION HOSPITAL OF JILIN UNIVERSITY. 10 % (w/v) homogenate of liver tissues was prepared with ice-cold 0.9 % NaCl solution. After centrifugation (3000 rpm, 4 °C for 10 min), supernatant was removed to another Eppendorf tube. The levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), triglyceride (TG), superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme activity and reduced glutathione (GSH) were measured by using assay kits according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the mixture was incubated for several minutes at a specific temperature after mixing the sample with the working solution, and then the absorbance was measured.

In addition, we analyzed the enzyme activities of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), acetaldehyde content, ROS and mitochondrial membrane potential levels at the cellular level according to the instructions. In brief, L-02 cells were seeded into a 6-well plate (30 × 104/well) and incubated for 24 h. Subsequently, L-02 cells were treated with Erguotou liquor (200 mM) and LGG (0, 0.5, 1 μg/mL, respectively) for another 24 h and then were collected for analysis.

2.7. Western blot

The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and solubilized in RIPA containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM of PMSF. After incubating on ice for 55 min, the lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, and then the protein concentration was quantified in the supernatant. 20–30 μg of total protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto PVDF membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5 % skim milk powder, and then were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h, followed by detection with an ECL revelation system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

2.8. Histopathological analysis

Left hepatic lobule samples were obtained and fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde. The frozen liver tissues were embedded by optimum cutting temperature compound (OCT) and sectioned at 8 μm for Oil-red O staining. In addition, liver tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 4 μm slices for H&E analysis. These sections were evaluated using a microscope (Olympus, Japan). Quantitative analysis of liver pathology was performed based on H&E and Oil Red O staining, with measurements obtained from three randomly selected microscopic fields.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data were displayed as mean ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test. Comparisons with P value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software, version 8.0.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of ginsenosides in LGP

Ginsenosides are the principal bioactive constituents of ginseng. To characterize the ginsenoside profile of LGP, we performed HPLC analysis on LGG. As shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1, the most prevalent ginsenosides, such as Rg1, Re, and Rb1, are transformed into the rare ginsenosides Rh4, Rk3, Rg3, Rg5, and Rk1, which account for about 60 % of the total ginsenosides. It was proven that these rare ginsenosides have a greater bioactivity and absorption rate than normal ginsenosides [16].

Fig. 1.

HPLC analysis of ginsenosides present in the LGG.

3.2. Serum biochemical evidence for the hepatoprotective effect of LGP against alcohol-induced liver injury

To assess the hepatoprotective effects of LGP against alcohol-induced liver injury, a subacute liver injury model was established in C57BL/6 mice via daily oral gavage of 56 % Erguotou liquor (equivalent to 2400 mg/kg ethanol) for 15 consecutive days. Compared to the control group, ethanol-treated mice exhibited significant elevations in serum TBIL, LDL, and CHOL, confirming successful induction of subacute liver injury (Supplementary Table 2).

ALT and AST, enzymes predominantly localized in hepatocytes and involved in amino acid metabolism, are widely recognized as sensitive indicators of hepatocellular injury [17]. Hepatic damage typically results in leakage of these enzymes into the bloodstream [18]. In the model group, serum ALT and AST levels were significantly elevated following ethanol exposure (Fig. 2A and B). Notably, high-dose LGP administration markedly attenuated these elevations, indicating a protective effect. Additionally, alcohol-induced liver damage can impair bile formation and excretion, leading to increased serum TBIL and ALP biomarkers commonly associated with cholestasis and hepatic dysfunction [19,20]. Ethanol exposure significantly elevated both ALP and TBIL levels (Fig. 2C and D). High-dose LGP significantly reduced both ALP and TBIL levels close to those of the normal control group, whereas low-dose LGP decreased ALP but did not significantly affect TBIL.

Fig. 2.

LGP markedly reversed alcohol-induced elevations in serum biomarkers of liver injury, including (A) ALT, (B) AST, (C) ALP, (D) TBIL, (E) LDL, and (F) CHOL in alcohol-treated C57BL/6 mice. Male C57BL/6 mice (20 ± 2 g, 4–6 weeks old) were orally administered either vehicle or 56 % Erguotou liquor (corresponding to 2400 mg/kg ethanol) once daily for 15 consecutive days. LGP was administered at doses of 12.5 or 50 mg/kg via oral gavage for 30 days prior to and during alcohol exposure. Twenty-four hours after the final administration, blood samples were collected for biochemical analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. alcohol model group.

Liver injury is frequently accompanied by lipid metabolism disorders, resulting in dyslipidemia characterized by increased levels of LDL and CHOL [21]. The model group showed marked increases in CHOL and LDL, which were reduced by 25 % and 14 %, respectively, in the high-dose LGP group (Fig. 2E and F).

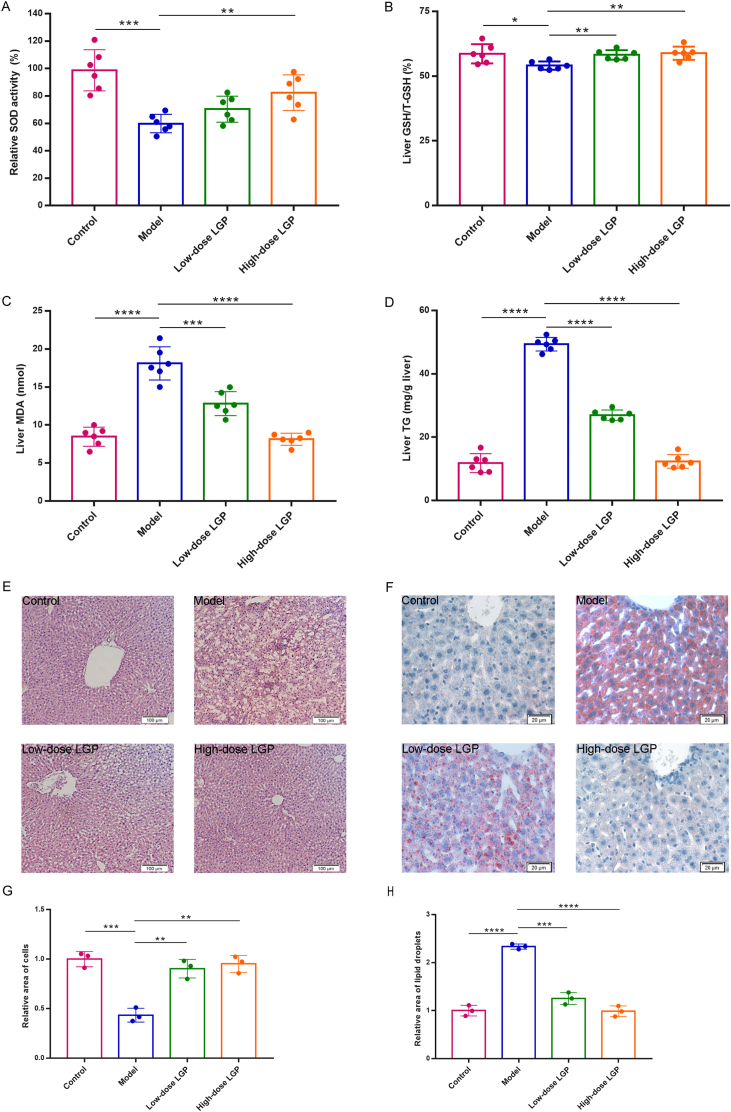

3.3. LGP alleviated alcohol-induced oxidative stress

Excessive alcohol consumption promotes the overproduction of ROS [22], leading to oxidative stress and depletion of critical endogenous antioxidants such as GSH. To assess oxidative damage and antioxidant defense, hepatic SOD activity and GSH content were measured. As anticipated, ethanol exposure significantly reduced SOD activity and GSH/T-GSH ratio in the model group (Fig. 3A and B). Notably, treatment with LGP at 50 mg/kg significantly restored SOD activity and GSH/T-GSH ratio to near normal control levels, suggesting that LGP mitigates alcohol-induced oxidative stress by enhancing the antioxidant defense system.

Fig. 3.

LGP significantly reversed alcohol-induced changes in hepatic (A) SOD, (B) GSH, (C) MDA, and (D) TG levels, and alleviated liver histological injury (E) and lipid accumulation (F). Quantitative analysis of H&E (G) and Oil Red O (H) assay was also performed, based on three randomly selected microscopic fields. Twenty-four hours after the final treatment (under the same experimental conditions described in Fig. 2), liver samples were collected for analysis. H&E staining (left, 40 × ) and Oil Red O staining (right, 200 × ) were performed. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 vs. alcohol model group.

Disruption of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and impaired fatty acid oxidation caused by alcohol further contribute to hepatic lipid metabolic dysfunction and lipid accumulation. MDA, a lipid peroxidation byproduct, serves as a key biomarker of oxidative damage to cell membranes [23]. In this study, MDA levels were markedly elevated in ethanol-treated mice, while LGP administration particularly at the high dose led to a notable reduction in MDA levels, bringing them close to those observed in the control group (Fig. 3C), indicating that LGP effectively attenuates lipid peroxidation and oxidative membrane damage in alcohol-induced liver injury.

3.4. LGP alleviated alcohol-induced histopathological damage and hepatic lipid accumulation

To assess hepatic tissue integrity and lipid deposition, histological analyses were conducted using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and Oil Red O staining. Liver sections from the control group displayed normal hepatic architecture, characterized by well-defined cell boundaries, uniform hepatocyte size, and distinct nuclei. In contrast, the alcohol-treated model group exhibited pronounced pathological changes, including hepatocellular edema, inflammatory infiltration, lipid droplet accumulation, and focal necrosis (Fig. 3E and G). Treatment with low-dose LGP markedly reduced necrotic lesions, whereas high-dose LGP (50 mg/kg) substantially restored hepatic architecture, closely resembling normal morphology (Fig. 3E and G). Oil Red O staining revealed severe steatosis in the model group (Fig. 3F and H). LGP treatment significantly reduced lipid droplet accumulation in a dose-dependent manner, demonstrating its effectiveness in alleviating alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis (Fig. 3F and H). Furthermore, hepatic TG content was significantly increased in ethanol-treated mice but was notably decreased by LGP administration; high-dose LGP (50 mg/kg) restored TG levels comparable to those of the control group (Fig. 3D).

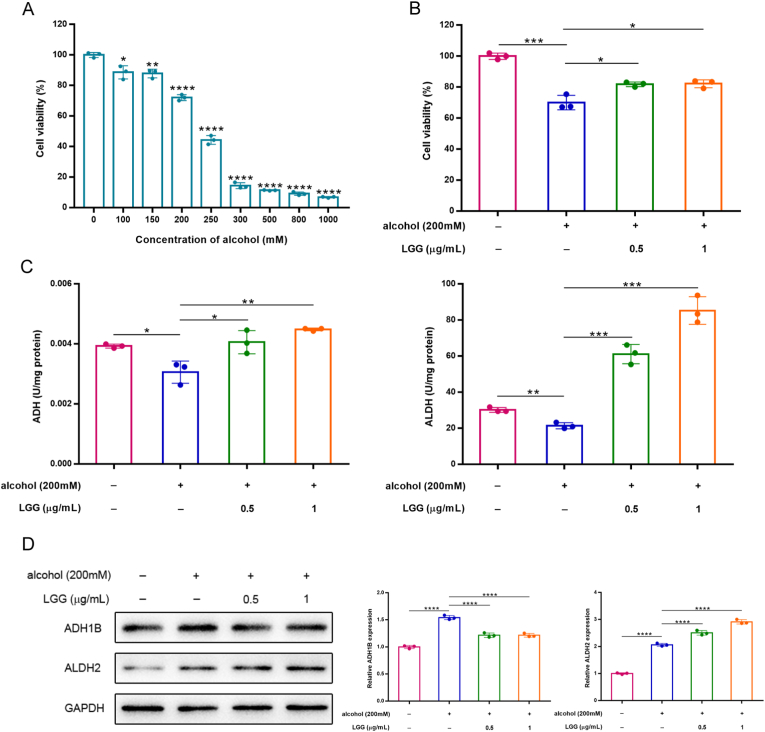

3.5. LGG enhanced alcohol metabolism by upregulating ADH and ALDH activities

Building upon the observed hepatoprotective effects of LGP in vivo, further mechanistic investigations were conducted using human hepatic L-02 cells. The MTT result showed ethanol inhibited L-02 cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner, with the IC50 of 238 mM (Fig. 4A). Therefore, a final ethanol concentration of 200 mM was selected for subsequent experiments. Co-treatment with LGG at concentrations of 0.5 and 1 μg/mL significantly improved cell viability compared to ethanol exposure alone, indicating a potential cytoprotective effect of LGG (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

LGG markedly eliminated cytotoxic effect of alcohol on human hepatic L-02 cells through up-regulating ADH and ALDH activities. (A) Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay in L-02 cells exposed to various concentrations of ethanol (0–1000 mM) for 48 h, showing dose-dependent cytotoxicity. (B) Cell viability was assessed exposed to different concentrations of LGG in the presence of ethanol (200 mM), demonstrating the protective effect of LGG. (C) Enzyme activity assays for ADH and ALDH were performed in L-02 cells. (D) Western blot analysis on the expression of ADH1B and ALDH2. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 vs. the alcohol model group.

Ethanol metabolism primarily occurs in the liver, where alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) catalyzes the conversion of ethanol to acetaldehyde in the cytosol, followed by the oxidation of acetaldehyde to acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in mitochondria [24]. To elucidate whether LGG modulates this metabolic pathway, we assessed the enzymatic activities of ADH and ALDH. Ethanol exposure significantly reduced the activities of both enzymes compared to untreated controls (Fig. 4C). However, LGG significantly enhanced the enzymatic activities of ADH and ALDH compared to the alcohol group, particularly at 1 μg/mL, suggesting its role in promoting alcohol clearance (Fig. 4C). Western blot analysis further demonstrated that ethanol treatment increased the protein expression levels of ADH1B and ALDH2, potentially as an adaptive response to elevated intracellular acetaldehyde. Interestingly, LGG intervention significantly upregulated ALDH2 protein levels relative to the alcohol group, while simultaneously downregulating ADH1B expression (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the regulation of the ADH family by ethanol may not be limited to ADH1B, but rather a more complex compensatory mechanism exists. These results suggested that LGG promotes alcohol metabolism by increasing enzymatic activities of ADH and ALDH, thereby contributing to its hepatoprotective effects.

3.6. LGG attenuated alcohol-induced cellular damage by reducing acetaldehyde and ROS, increasing mitochondrial membrane potential and promoting autophagy

Ethanol is primarily metabolized in the liver, where it is oxidized by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) into acetaldehyde, a highly toxic intermediate that induces hepatotoxicity by disrupting cellular membranes and organelles, forming adducts with proteins and DNA, and impairing normal physiological functions [25]. Measurement of acetaldehyde levels revealed that the LGG treated group exhibited significantly lower concentrations compared to the ethanol only group, and even lower than those in the normal control group (Fig. 5A), indicating that LGG possesses a strong ability to eliminate acetaldehyde derived from both ethanol metabolism and endogenous cellular processes. Ethanol metabolism also generates excessive ROS, contributing to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [26]. Our results showed that ethanol exposure led to a significant increase in total ROS and a marked reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential compared to the control group. As expected, LGG treatment effectively reversed these alterations (Fig. 5B and C).

Fig. 5.

LGG markedly attenuated alcohol-induced cellular damage in L-02 cells. (A) Intracellular acetaldehyde levels were quantified using an assay kit. (B) Total intracellular ROS levels were measured using an assay kit. (C) Representative images of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) were captured by JC-1 staining. Red fluorescence indicates high Δψm (aggregates), and green fluorescence indicates low Δψm (monomers). (D) Western blot analysis revealed the expression levels of key proteins (LC3 II and p62) associated with autophagy. expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 vs. the alcohol model group.

Emerging evidence indicates that autophagy plays a key cytoprotective role in alcohol-induced liver injury, with enhanced autophagic flux helping to alleviate hepatocellular damage [27,28]. We therefore examined the expression of key autophagy-related proteins. Western blot analysis revealed that ethanol treatment increased both LC3 I and LC3 II levels but reduced the LC3 II/LC3 I ratio, suggesting that while autophagy initiation was activated, oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage led to impaired autophagic flux (Fig. 5D). In contrast, LGG treatment reduced LC3 I expression and significantly increased the LC3 II/LC3 I ratio, indicating restoration of autophagic flux and improved autophagy efficiency. Additionally, the autophagy substrate p62, which was upregulated by ethanol, was markedly decreased by LGG, further supporting the activation of autophagy in LGG-treated cells (Fig. 5D).

Collectively, these findings suggest that LGG mitigates alcohol-induced cellular injury by promoting acetaldehyde clearance, reducing oxidative stress, restoring mitochondrial function, and enhancing autophagic activity.

4. Discussion

Excessive alcohol consumption is a major global health issue, contributing significantly to morbidity, mortality, and social burdens. This study systematically evaluated the hepatoprotective effects of LGP against alcohol-induced liver injury using both C57BL/6 mice and L-02 hepatic cell models. Chemical analysis revealed that LGP is enriched in rare ginsenosides (Rh4, Rg3, Rg5, Rk1, and Rk3), while conventional ginsenosides common in fresh or white ginseng (e.g., Rb1, Rb2, Rd, Re, Rg1) were nearly absent. This unique profile may underlie LGP's enhanced bioactivity.

In vivo, alcohol administration induced typical signs of liver injury in mice, including significant elevations in serum AST, ALT, ALP, TBIL, LDL, and CHOL levels (Fig. 2). LGP treatment effectively reversed these biochemical abnormalities, demonstrating its strong hepatoprotective potential. Additionally, alcohol suppressed hepatic antioxidant defenses, as evidenced by decreased SOD activity and GSH levels (Fig. 3B and C), both of which were significantly restored by LGP, indicating enhanced oxidative stress mitigation. Histological analyses further confirmed that LGP reduced hepatic lipid accumulation and alleviated steatosis, particularly in the high-dose group, where liver morphology closely resembled that of the normal control (Fig. 3E and F). Previous study has shown that Korean Red ginseng confers hepatoprotection against alcohol-induced liver damage; however, LGP appears more effective in reducing lipid droplet accumulation [29]. Importantly, LGP exhibited no signs of acute toxicity at doses up to 22.9 g/kg body weight, with no observed behavioral or physiological abnormalities (data not shown).

Mechanistic in vitro studies revealed for the first time that ginsenosides (LGG) significantly enhanced the activity of both ALDH and ADH in human hepatic L-02 cells (Fig. 4C). The reduction in acetaldehyde levels corresponded well with increased ALDH activity. Notably, LGG reduced acetaldehyde concentrations to below those of the healthy control, indicating potent acetaldehyde scavenging capacity and suggesting robust hepatoprotective efficacy. At the protein level, LGG upregulated ALDH2 while downregulating ADH1B (Fig. 4D), indicating a regulatory mechanism aimed at minimizing acetaldehyde accumulation, consistent with known ADH and ALDH polymorphisms that influence acetaldehyde metabolism [25]. Moreover, LGG significantly decreased ROS levels and improved mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 5A–C), reflecting preserved mitochondrial function. LGG also activated autophagy, as indicated by increased LC3 II conversion and reduced p62 expression (Fig. 5D), suggesting enhanced autophagic flux. This activation likely promotes the clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria and protein aggregates, enhancing cellular resilience under alcohol-induced stress.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that LGP exerts multifaceted hepatoprotective effects through modulation of liver function, oxidative stress, ethanol-metabolizing enzymes, mitochondrial integrity, and autophagy. Notably, this study is the first to reveal differential regulation of ADH1B and ALDH2 protein expression by LGP, highlighting autophagy activation as a novel mechanism underlying its protective action. The enriched rare ginsenosides with superior bioavailability may account for LGP's multi-targeted efficacy, supporting its potential as a therapeutic agent for ALD. Nonetheless, limitations include possible differences in translation from animal models to humans, and the contribution of individual rare ginsenosides in LGP requires further elucidation in future studies.

5. Conclusion

In summary, LGP significantly mitigated markers of alcohol-induced liver injury, reduced lipid accumulation, and enhanced antioxidant capacity in a murine model of ALD, demonstrating excellent liver-protective effects. Its liver-protective mechanism was first discovered: promoted ethanol metabolism, reduced oxidative stress, restored mitochondrial function, and activated autophagy. These findings provide a strong experimental basis for developing LGP as a safe, multi-targeted natural therapeutic for ALD and warrant further clinical investigation.

Institutional review board statement

The animal study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Jilin University (NO. SY0906, September 6, 2017), in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Statement: During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT to improve readability and language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Provincial Project for Industrial Innovation Special Fund of Jilin Province (2017) and Special Project for Province and University Construction Plan of Jilin Province (SXGJXX2017-13).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgr.2025.10.004.

Contributor Information

Yang Li, Email: liyang915@jlu.edu.cn.

Ying-Hua Jin, Email: yhjin@jlu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Asrani S.K., Devarbhavi H., Eaton J., Kamath P.S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70(1):151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackowiak B., Fu Y., Maccioni L., Gao B. Alcohol-associated liver disease. J Clin Investig. 2024;134(3) doi: 10.1172/JCI176345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seitz H.K., Bataller R., Cortez-Pinto H., Gao B., Gual A., Lackner C., et al. Alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):16. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teli M.R., Day C.P., Burt A.D., Bennett M.K., James O.F. Determinants of progression to cirrhosis or fibrosis in pure alcoholic fatty liver. Lancet. 1995;346(8981):987–990. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devarbhavi H., Asrani S.K., Arab J.P., Nartey Y.A., Pose E., Kamath P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. 2023;79(2):516–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao B., Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1572–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louvet A., Mathurin P. Alcoholic liver disease: mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(4):231–242. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S., Tan H.Y., Wang N., Zhang Z.J., Lao L., Wong C.W., et al. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in liver diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(11):26087–26124. doi: 10.3390/ijms161125942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song D.S. Medical treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2020;76(2):65–70. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2020.76.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu S., Li S.W., Yan Q., Hu X.P., Li L.Y., Zhou H., et al. Natural products, extracts and formulations comprehensive therapy for the improvement of motor function in alcoholic liver disease. Pharmacol Res. 2019;150 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratan Z.A., Haidere M.F., Hong Y.H., Park S.H., Lee J.O., Lee J., et al. Pharmacological potential of ginseng and its major component ginsenosides. J Ginseng Res. 2021;45(2):199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao Y., Chu S., Zhang Z., Chen N. Hepataprotective effects of ginsenoside Rg1 - a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;206:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qu L., Zhu Y., Liu Y., Yang H., Zhu C., Ma P., et al. Protective effects of ginsenoside Rk3 against chronic alcohol-induced liver injury in mice through inhibition of inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;126:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai Y., Tan Q., Xv S., Huang S., Wang Y. Li yet al. Ginsenoside Rb1 alleviates alcohol-induced liver injury by inhibiting steatosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.616409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang K., Ryu T., Chung B.S. A meta-analysis of preclinical studies to investigate the effect of Panax ginseng on alcohol-associated liver disease. Antioxidants. 2023;12(4) doi: 10.3390/antiox12040841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan W., Fan L., Wang Z., Mei Y., Liu L. Li let al. Rare ginsenosides: a unique perspective of ginseng research. J Adv Res. 2024;66:303–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2024.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun X., Wang J., Ge Q., Li C., Ma T., Fang Y., et al. Interactive effects of copper and functional substances in wine on alcoholic hepatic injury in mice. Foods. 2022;11(16) doi: 10.3390/foods11162383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y., Zhang Y., Fan J., Zhou H., Huang H., Cao Y., et al. Effects of different viscous guar gums on growth, apparent nutrient digestibility, intestinal development and morphology in juvenile largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides. Front Physiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.927819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L., Guo Z., Cui D., Ul Haq S., Guo W., Yang F., et al. Toxicological evaluation of the ultrasonic extract from dichroae radix in mice and wistar rats. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong X., Zhang F., Li Y., Peng C. Study on the mechanism of acute liver injury protection in Rhubarb anthraquinone by metabolomics based on UPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1141147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li S., Duan X., Zhang Y., Zhao C., Yu M., Li X., et al. Lipidomics reveals serum lipid metabolism disorders in CTD-induced liver injury. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;25(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40360-024-00732-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He Y.X., Liu M.N., Wang Y.Y., Wu H., Wei M., Xue J.Y., et al. Hovenia dulcis: a Chinese medicine that plays an essential role in alcohol-associated liver disease. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1337633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L., Li A., Zhang X., Iqbal M., Aabdin Z.U. Xu met al. Effect of Bacillus subtilis isolated from yaks on D-galactose-induced oxidative stress and hepatic damage in mice. Front Microbiol. 2025;16 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1550556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song X.Y., Liu P.C., Liu W.W., Hayashi T., Mizuno K., Hattori S., et al. Protective effects of silibinin against ethanol- or acetaldehyde-caused damage in liver cell lines involve the repression of mitochondrial fission. Toxicol Vitro. 2022;80 doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2022.105330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Setshedi M., Wands J.R., Monte S.M. Acetaldehyde adducts in alcoholic liver disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3(3):178–185. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu H.S., Oyama T., Isse T., Kitagawa K., Pham T.T. Tanaka met al. Formation of acetaldehyde-derived DNA adducts due to alcohol exposure. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;188(3):367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ni H.M., McGill M.R., Chao X., Du K., Williams J.A., Xie Y., et al. Removal of acetaminophen protein adducts by autophagy protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. J Hepatol. 2016;65(2):354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin G.S., Zhao M.M., Fu Q.C., Zhao S.Y., Ba T.T., Yu H.X. Palmatine attenuates hepatocyte injury by promoting autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR pathway after alcoholic liver disease. Drug Dev Res. 2022;83(7):1613–1622. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H.J., Ok H.M., Kwon O. Protective effects of Korean red ginseng against alcohol-induced fatty liver in rats. Molecules. 2015;20(6):11604–11616. doi: 10.3390/molecules200611604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.