Abstract

Objective

To determine the efficacy, gastrointestinal safety, and tolerability of celecoxib (a cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX 2) inhibitor) used in the treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Design

Systematic review of randomised trials that compared at least 12 weeks' celecoxib treatment with another non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or placebo and reported efficacy, tolerability, or safety. Trials identified from manufacturer and by searching electronic databases and evaluated according to predefined inclusion and quality criteria. Data combined through meta-analysis.

Participants

15 187 patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis.

Main outcome measures

Efficacy: Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index; American College of Rheumatology responder index and joint scores for rheumatoid arthritis. Tolerability: withdrawal rates for adverse effects. Gastrointestinal safety: incidence of ulcers, bleeds, perforations, and obstructions.

Results

Nine randomised controlled trials were included. Celecoxib and NSAIDS were equally effective for all efficacy outcomes. Compared with those taking other NSAIDs, in patients taking celecoxib the rate of withdrawals due to adverse gastrointestinal events was 46% lower (95% confidence interval 29% to 58%; NNT 35 at three months), the incidence of ulcers detectable by endoscopy was 71% lower (59% to 79%; NNT 6 at three months), and the incidence of symptoms of ulcers, perforations, bleeds, and obstructions was 39% lower (4% to 61%; NNT 208 at six months). Subgroup analysis of patients taking aspirin showed that the incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy was reduced by 51% (14% to 72%) in those given celecoxib compared with other NSAIDs. The reduction was greater (73%, 52% to 84%) in those not taking aspirin.

Conclusion

Celecoxib is as effective as other NSAIDs for relief of symptoms of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis and has significantly improved gastrointestinal safety and tolerability.

What is already known on this topic

Long term NSAID use is associated with the development of peptic and duodenal ulcers

COX 2 specific inhibitors are claimed to cause fewer gastrointestinal complications

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence has recently recommended that COX 2 specific inhibitors are used in patients with arthritis who are at risk of gastrointestinal complications but not in those taking prophylactic aspirin

What this study adds

Systematic review of randomised trials shows that celecoxib is as effective as other NSAIDs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis

Celecoxib has significantly improved gastrointestinal safety and tolerability compared with standard NSAIDs

An improvement in gastrointestinal safety was still evident in patients who were also taking aspirin

Introduction

Arthritis is a widespread, potentially disabling disease. Of the two common forms, osteoarthritis is more prevalent than rheumatoid arthritis. The impact of arthritis on pain, disability, and quality of life results in a considerable burden to the individual, health services, and society.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are prescribed for the treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis and provide effective relief from symptoms. However, serious gastrointestinal complications occur with their use. NSAIDs cause peptic and duodenal ulcers, which may perforate and bleed and even lead to death.1 There are between 2000-2500 deaths annually in the United Kingdom due to use of NSAIDs.2,3

NSAIDs control pain and inflammation by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase 1 and 2 (COX 1 and COX 2) enzymes. Inhibition of the COX 1 enzyme is responsible for the associated gastrointestinal toxicity. Celecoxib was developed as a COX 2 specific inhibitor to provide relief without the associated gastrointestinal complications.

We conducted a systematic review of all published and unpublished trials to determine if celecoxib is as effective as other NSAIDs for the treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis and if there is evidence of greater gastrointestinal tolerability and safety.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

For the assessment of efficacy we included randomised controlled trials if they were double blind, compared celecoxib at a licensed therapeutic dose for at least 12 weeks with placebo or another NSAID at a standard dose (defined as being within the range recommended within the British National Formulary4) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, and reported efficacy, tolerability, or safety outcomes. In addition, to investigate safety we considered data on doses of celecoxib above those recommended for treatment. Placebo comparisons were included to demonstrate the sensitivity of efficacy outcomes and to investigate gastrointestinal toxicity.

Outcome measures

We present efficacy outcomes for results of the Western Ontario and McMaster universities (WOMAC) osteoarthritis index for pain (scored 0 to 20), stiffness (scored 0 to 8), and physical function (scored 0 to 68). We used the American College of Rheumatology (ACR-20) responder index and evaluations of improvement in the numbers of painful or tender and swollen joints for trials of rheumatoid arthritis.

Drug tolerability was assessed by considering rates of withdrawal due to any adverse event, any gastrointestinal adverse event, and specific gastrointestinal adverse events at 12 weeks. Gastrointestinal safety was assessed by comparing the incidence of ulcers detected by routine endoscopy at 12 and 24 weeks and the incidence of symptomatic ulcers, perforations, bleeds, and obstructions up to 24 weeks.

Study identification

We aimed to include all randomised trials of celecoxib, regardless of whether or not they had been published. We obtained from the manufacturer reports from all industry sponsored randomised controlled trials that were completed by 25 May 2000 and that compared celecoxib with placebo or other NSAID in people with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. We also searched Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane controlled trials register from 1998 to March 2001 using the search terms celecoxib, Celebrex, and SC-58635.

Appraisal of trial quality

The quality of the trials was assessed according to predefined criteria. To assess the potential for bias we considered the method of randomisation, concealment of allocation, blinding of trial investigators and patients, completeness of follow up, and analysis according to intention to treat.

Data extraction

Summary outcome data were extracted from the original company trial reports as these provided more comprehensive data than that given in the published peer reviewed literature. JJD abstracted data, which were checked by MDB. We combined multiple celecoxib treatment arms within trials that randomised to more than one dose.

Data synthesis

Separate meta-analyses were undertaken for each comparison and outcome. We analysed efficacy data separately for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis as the diseases manifest with different levels of pain, stiffness, and swelling and were assessed in the trials with different outcome measurements. Data on patients randomised to receive 800 mg celecoxib per day (above the recommended dose) were included in tolerability and safety analyses but excluded from efficacy analyses. We analysed tolerability and safety data for the two diseases combined as there is no evidence for a causal link between the nature of the disease and adverse events related to treatment, and the biological plausibility of such a relation is considered low.

Dichotomous data were summarised as relative risks and combined with the Mantel-Haenszel method; continuous data were summarised as differences in means and combined by using the inverse variance method.5 All results are given with 95% confidence intervals. We computed homogeneity statistics to test the agreement of the individual trial results with the overall meta-analytical summary.5 If we detected significant heterogeneity (P<0.1) we also calculated random effects estimates using DerSimonian and Laird method.5 Analyses were carried out in Stata V6.0 with the metan macro.

Results

We obtained reports of 17 trials, nine of which (15 187 patients) fulfilled the inclusion criteria.6–14 We excluded eight in which follow up was less than 12 weeks. All included trials compared celecoxib with at least one NSAID (diclofenac, naproxen, or ibuprofen); five trials also had a placebo control group. All nine trials reported efficacy and tolerability outcomes, but we excluded three from the efficacy analysis as the results were not available separately for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Four studies assessed upper gastrointestinal safety by endoscopy at 12 weeks,7–9,13 one study assessed the same outcome at 24 weeks.10 The largest study (n=7968) reported on symptomatic upper gastrointestinal disease after 26 weeks of treatment.11 The table gives full details of the studies.

Trial quality

All nine trials were of high quality. All were randomised with adequate concealment of treatment allocation and achieved double blinding with double dummy tablets. They described withdrawals and exclusions and used intention to treat analyses with missing data for efficacy analyses being estimated by carrying the last value forward.

After 12 weeks of treatment, 56% of patients in the placebo group had dropped out due to poor efficacy or adverse events. Dropout rates in celecoxib and other NSAID groups were lower (39% on celecoxib 200 mg per day; 32% on celecoxib 400 mg per day; 39% on naproxen 1000 mg per day; 26% on diclofenac 150 mg per day).

Effectiveness of celecoxib for treatment at 12 weeks

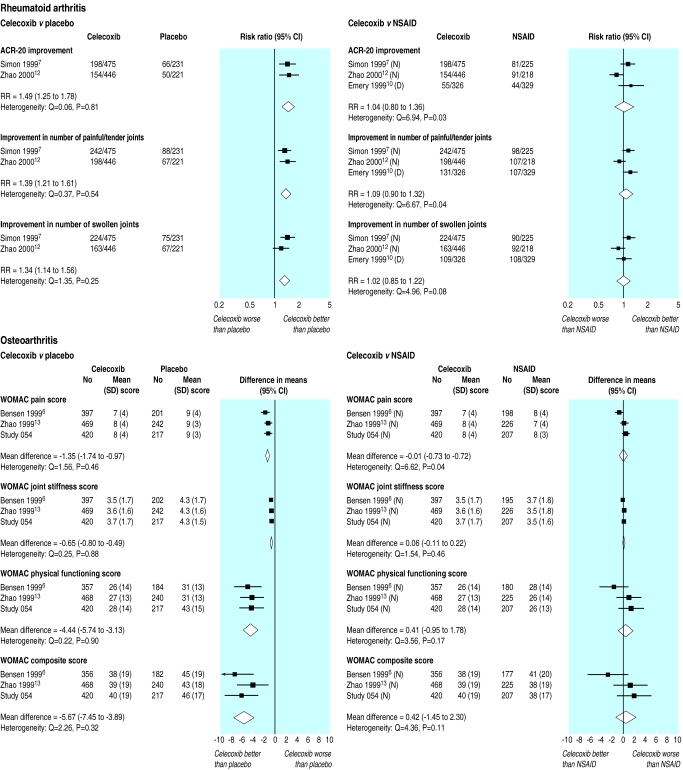

Rheumatoid arthritis—In two placebo controlled trials with 1373 patients celecoxib provided significant improvement in all outcomes compared with placebo: 49% more patients (95% confidence interval 25% to 78%) met the ACR-20 responder criteria, 39% more (21% to 61%) had reductions in the number of painful or tender joints, and 34% more (14% to 56%) had reductions in the number of swollen joints (fig 1).7,12 Three trials with 2019 patients compared celecoxib with other NSAIDS (naproxen 500 mg twice daily in two trials7,12 and diclofenac 75 mg twice daily in one10). There were no significant differences, with all drugs being equally effective for all outcomes. With celecoxib the ACR-20 responder rate was 4% higher (−20% to 36%), 9% more (−10% to 32%) showed improvement in the number of painful or tender joints, and 2% more (−15% to 22%) showed improvement in the number of swollen joints (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Efficacy outcomes at 12 weeks in randomised controlled trials of celecoxib versus placebo and NSAIDs. D=diclofenac 75 mg twice daily, I=ibuprofen 800 mg thrice daily, N=naproxen 500 mg twice daily

Osteoarthritis—In three placebo controlled trials with 1947 patients, compared with placebo celecoxib resulted in significant (P<0.0001) improvement in all components of the WOMAC scale—pain (mean difference −1.4, −1.7 to −1.0), stiffness (−0.7, −0.8 to −0.5), and physical function (−4.4, −5.7 to −3.3)—as well as the composite WOMAC score (−5.7, −7.5 to −3.9) (fig 1).6,13,14 The same three trials compared celecoxib with naproxen 500 mg twice daily in 1917 patients. There were no significant differences between celecoxib and naproxen, with both drugs being equally effective for all components of the WOMAC scale: pain (0.0, −0.7 to 0.7), stiffness (0.1, −0.1 to 0.2), and physical function (0.4, −1.0 to 1.8) and the composite WOMAC score (0.4, −1.5 to 2.3) (fig 1).

Tolerability

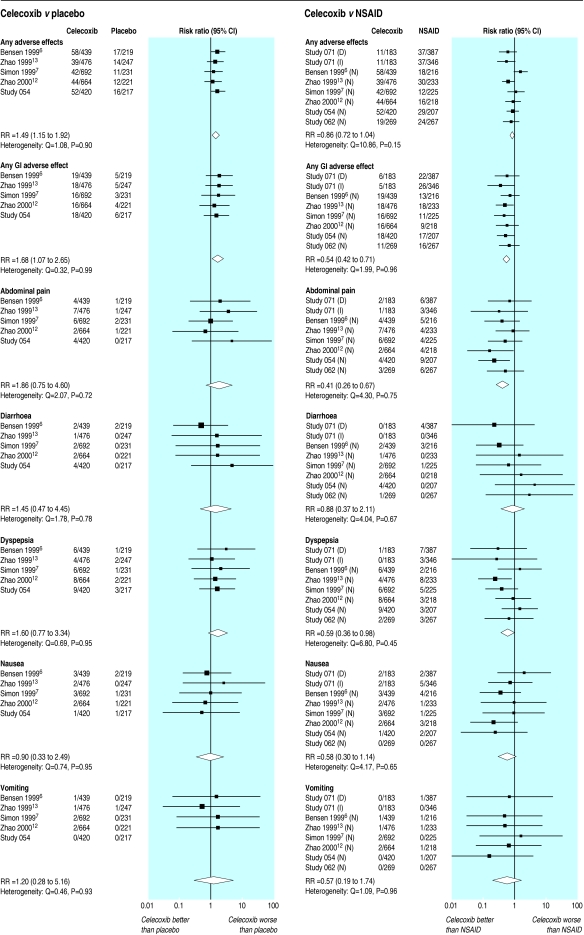

Celecoxib versus placebo—Five trials with 3826 patients reported drug related withdrawals after 12 weeks' treatment (fig 2).6,7,12–14 Withdrawal due to adverse events occurred more often on celecoxib than on placebo, both for any adverse event (relative risk 1.49, 1.15 to 1.92) and for all gastrointestinal adverse events (1.68, 1.07 to 2.65). However, withdrawals due to abdominal pain, diarrhoea, dyspepsia, nausea, or vomiting were not significantly increased with celecoxib compared with placebo.

Figure 2.

Rates of withdrawal from randomised controlled trials of celecoxib versus placebo and NSAIDs at 12 weeks attributed to adverse effects of treatment. D=diclofenac 75 mg twice daily, I=ibuprofen 800 mg thrice daily, N=naproxen 500 mg twice daily

Celecoxib versus NSAID—Seven trials with 5425 patients reported drug related withdrawals after 12 weeks' treatment (fig 2).6–9,12–14 In six trials the NSAID was naproxen 500 mg twice daily6–8,12–14 and in the other one it was diclofenac 75 mg twice daily and ibuprofen 800 mg three times daily.9 There was no significant difference between celecoxib and NSAID in the incidence of withdrawals for all adverse events. However, there was a significant decrease in the number of withdrawals due to gastrointestinal adverse events (0.54, 0.42 to 0.71), corresponding to a number needed to treat of 35 at three months. Of the specific gastrointestinal adverse events, there were significantly fewer withdrawals due to abdominal pain and dyspepsia in the celecoxib group compared with other NSAIDs (0.41, 0.26 to 0.67, and 0.59, 0.36 to 0.98, respectively). The incidence of withdrawals due to diarrhoea, nausea, or vomiting were not significantly different between celecoxib and other NSAIDs.

Ulcers detected by endoscopy

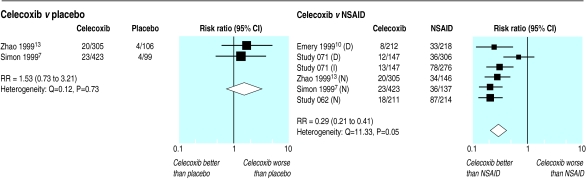

Celecoxib versus placebo—Two trials with 933 patients reported on ulcers detected by endoscopy after 12 weeks treatment.7,13 Although there was no significant difference in the number of ulcers detected between the groups, the results were compatible with up to a threefold increase in the incidence of ulcers (fig 3).

Figure 3.

Incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy in randomised trials of celecoxib versus placebo and NSAIDs that included routine endoscopy investigations at 12 weeks. D=diclofenac 75 mg twice daily, I=ibuprofen 800 mg thrice daily, N=naproxen 500 mg twice daily

Celecoxib versus NSAID—Five trials with 2742 patients reported on ulcers detected by endoscopy after 12 weeks treatment (fig 3).7–10,13 The incidence of ulcers was 71% (59% to 79%) lower in those taking celecoxib compared with other NSAIDs, corresponding to a number needed to treat of six at three months. The one study that reported ulcers detected by endoscopy at 24 weeks found a similar significant reduction, with incidence being 75% (47% to 88%) lower in those taking celecoxib.10

Ulcers, perforations, bleeds, and obstructions at 24 weeks

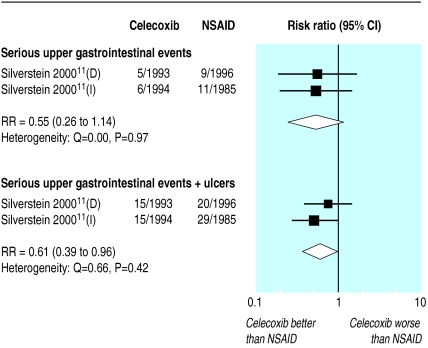

The CLASS study of 7968 patients investigated the incidence of serious upper gastrointestinal events (bleeds, perforations, obstructions) in those taking celecoxib (3987 given celecoxib 800 mg per day; above the recommended dose) compared with other NSAIDs (1985 took ibuprofen, 1996 took diclofenac).11 Patients were monitored and withdrawn from the trial due to adverse events, if endoscopy indicated a symptomatic ulcer, if prolonged use of an ulcer healing treatment was required, or if treatment did not control the symptoms of arthritis. At six months the overall rates of withdrawal were 40% for celecoxib, 42% for diclofenac, and 47% for ibuprofen. With celecoxib the incidence of serious adverse events, bleeds, perforations, or obstructions (n=11) was nearly half that with the other NSAIDs (n=20), but this difference was not significant (P=0.11, fig 4).

Figure 4.

Incidence of symptomatic ulcers, perforations, bleeds, and obstructions in CLASS randomised trial of 24 weeks' treatment with celecoxib 400 mg twice daily versus diclofenac 75 mg twice daily (D) or ibuprofen 800 mg thrice daily (I). Trial stratified into two parts: celecoxib versus diclofenac and celecoxib versus ibuprofen

Among the participants withdrawn from the trial for safety reasons, 19 patients taking celecoxib were found to have ulcers on endoscopy compared with 29 patients taking other NSAIDs. When ulcers were included within the definition of serious adverse events the reduction with celecoxib became significant (P=0.03, fig 4).

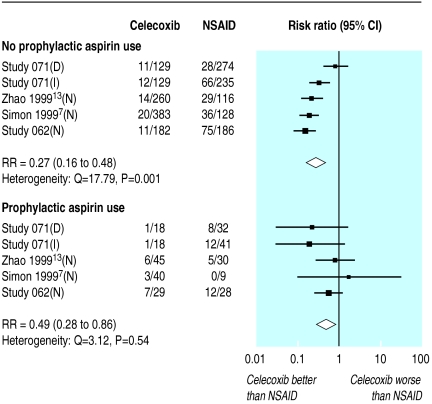

Benefits of celecoxib in patients receiving low dose aspirin

Four trials compared celecoxib with other NSAIDs and provided data on the incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy in patients according to whether or not the patients were taking aspirin (up to 325 mg/day).7–9,13 The benefit of celecoxib seemed greater in those not taking aspirin (73% reduction in incidence, 52% to 84%) compared with those taking aspirin (51% reduction in incidence, 14% to 72%), although the difference between subgroups was not significant (P=0.18, fig 5).

Figure 5.

Impact of prophylactic aspirin on incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy in randomised trials of celecoxib versus placebo and NSAIDs that included routine endoscopy investigations at 12 weeks. D=diclofenac 75 mg twice daily, I=ibuprofen 800 mg thrice daily, N=naproxen 500 mg twice daily

In the CLASS study 1739 patients were taking aspirin.11 The reduction in the incidence of clinical ulcers, perforation, bleeds, and obstructions was smaller in those taking aspirin (19% reduction, −63% to 60%) than in those not taking aspirin (50% reduction, 8% to 72%). This difference between the subgroups was not significant (P=0.44).

Discussion

In this review of randomised controlled trials we have shown that celecoxib is as effective as other NSAIDs for the relief from symptoms of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. The confidence intervals around the point estimates of efficacy were reasonably narrow, which mean that it is unlikely that there were clinically important differences. Compared with other NSAIDs, however, celecoxib showed increased upper gastrointestinal safety and tolerability. Rates of withdrawal due to gastrointestinal adverse event, dyspepsia, and abdominal pain were 40-60% lower, while the incidence of ulcers and serious upper gastrointestinal events was 40-75% lower.

Our conclusions are robust and unlikely to be influenced by bias. Beyond the stated involvement of MDB, the industrial sponsors had no involvement in the review process once the protocol had been agreed. We included published and unpublished studies, and we insisted that the companies involved provided a signed legal statement confirming that they had made available data from all celecoxib trials that were completed before our inclusion date. We evaluated the impact of including unpublished studies by sensitivity analyses for main outcomes (presented in figs 1–4); our findings and interpretation did not change. Results of further phase 4 trials (the Success trial) have recently been partially published in abstract form since we completed our search. We did not add these to our review as they are incomplete and could introduce bias.15

As we abstracted data directly from original trial reports we minimised the effects of missing data and errors in transcription. Access to individual patient data would have allowed us to investigate further any variation in treatment effect with patient characteristics.

All included trials were designed and executed to meet standards required for licensing. Although withdrawals were common, the potential biases due to unequal withdrawals act in a conservative direction.

For most analyses we did not detect any heterogeneity, which supports pooling of different doses of drugs and disease states. Each analysis comprised large numbers of patients, baseline characteristics were similar, all patients had active disease at the start of the study, and efficacy outcomes assessed were those routinely required for licensing of drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (WOMAC and ACR-20). Additional efficacy outcomes that we investigated but have not reported here showed similar patterns of benefit.

Tolerability

Withdrawals for adverse events have been used as a measure of tolerability because long term use of NSAIDs typically leads to gastrointestinal disturbances and discontinuation of the drug. Estimates of withdrawal rates with placebo are difficult to interpret as a measure of tolerability because placebo groups had high attrition rates because of poor control of symptoms. Withdrawal rates with active treatment were lower. Significantly fewer withdrawals due to gastrointestinal adverse events occurred with celecoxib (about 3%) than with other NSAIDs (about 6%); withdrawals due to abdominal pain and dyspepsia approximately halved.

Upper gastrointestinal safety

Long term treatment with NSAIDs is associated with gastrointestinal ulcer disease.1–3 There was no significant increase in ulcers detected endoscopically with celecoxib compared with placebo, despite the difference in withdrawal rates. The incidence of ulcers was 70% lower with celecoxib compared with other NSAIDs. For every 100 patients treated with NSAIDs for 12-24 weeks, 23 developed either a gastric or duodenal ulcer, 16 of which would have been prevented if the patients had received celecoxib, giving a number needed to treat of six.

Not all ulcers detected by endoscopy progress to a serious event as some heal spontaneously. A more informative outcome measure is the actual incidence of events. In a single trial the incidence of ulcers, bleeds perforations, or obstructions was determined in almost 8000 patients receiving celecoxib or another NSAID (diclofenac or ibuprofen). Although the power of the study was reduced by a high withdrawal rate and a resulting low incidence of events, there was a significant 40% reduction in ulcers, bleeds, perforations, or obstructions in the celecoxib group, corresponding to a number needed to treat of 208 at six months. The dose of celecoxib used in this trial was twice the recommended maximum dose, which indicates that celecoxib does not exhibit the increased gastrointestinal toxicity with higher doses typical of other NSAIDs.

The publication of the CLASS trial has been criticised for not reporting results beyond the six month follow up.16,17 The company trial report indicates that while all participants started treatment at least six months before the study ended, the average follow up was only seven months. Importantly, duration of treatment (medians of 273, 257, and 186 days), total withdrawal rates (55%, 53%, and 65% for celecoxib, diclofenac, and ibuprofen respectively), and reasons for withdrawal varied significantly between treatment groups. Although variable follow up can be properly accounted for by using time to event analyses, withdrawal related to treatment cannot. We therefore present results at the longest follow up to which all participants could contribute, which reduces but does not eradicate these problems. Upper gastrointestinal safety beyond six months cannot reliably be determined from this trial.

Other potential adverse events

This review was limited to assessing only upper gastrointestinal safety. Recently the VIGOR (Vioxx gastrointestinal outcomes research) trial of rofecoxib has raised concerns about serious cardiovascular effects with the use of COX 2 inhibitors.18 While it is important to evaluate this concern, this was not possible here as the celecoxib trials we included did not report outcomes comparable with those assessed in VIGOR (all trials started recruitment before publication of VIGOR). This issue should be a priority for a future systematic review when adequate data on both celecoxib and rofecoxib are available.

Prophylactic use of aspirin

Aspirin is commonly prescribed to prevent cardiovascular disease, and, like NSAIDs, it inhibits COX 1 thus increasing the risk of a gastrointestinal event. Subgroup analysis of patients taking aspirin still showed a significant reduction (51%) in the incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy in those taking celecoxib compared with other NSAIDs, though the reduction was greater (74%) in those not taking aspirin. While the CLASS study was not adequately powered to investigate subgroup analyses for serious upper gastrointestinal events, the same pattern of results was observed, suggesting benefit in users and non-users of aspirin. The dose of aspirin used for prophylaxis in the United Kingdom is typically 75 mg daily, considerably less than the 325 mg commonly prescribed in the United States, where most of these trials were conducted. The present weight of evidence does not suggest that celecoxib should be withheld from aspirin users as currently recommended by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), but further research should clarify the size of the possible reduction in efficacy in this group.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis provides strong evidence of the effectiveness of celecoxib for relief of pain and inflammatory symptoms of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, the level of effectiveness being equivalent to that of other NSAID. However, the tolerability and gastrointestinal safety of celecoxib is substantially superior.

Table.

Characteristics of randomised controlled trials included in review

| Study | Details of participants (disease, mean (range) age (years), % with previous gastrointestinal ulcer) | Drug, dose, and No randomised

|

Duration (weeks) | Efficacy | Upper gastrointestinal safety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celecoxib | Placebo | NSAID | |||||

| Bensen, 19996 | Osteoarthritis of knee (n=801) and hip (n=74); 62 (21-89) years; 10% with ulcer | 100 mg bid (n=217); 200 mg bid (n=222) |

n=220 | Naproxen 500 mg bid (n=216) | 12 | WOMAC index | Not assessed |

| Zhao, 199913 | Osteoarthritis of knee; 62 (19-89) years; 17% with ulcer | 100 mg bid (n=239); 200 mg bid (n=237) | n=247 | Naproxen 500 mg bid (n=233) | 12 | WOMAC index | Incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy |

| Simon, 19997 | Rheumatoid arthritis; 54 (20-90) years; 15% with ulcer | 100 mg bid (n=240); 200 mg bid (n=235); 400 mg bid (n=218) |

n=231 | Naproxen 500 mg bid (n=225) | 12 | ACR-20 responder index, changes in painful or tender and swollen joints | Incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy |

| Zhao, 200012 | Rheumatoid arthritis; 55 (21-84) years; 8% with ulcer | 100 mg bid (n=228); 200 mg bid (n=219); 400 mg bid (n=217) | n=221 | Naproxen 500 mg bid (n=218) | 12 | ACR-20 responder index, changes in painful or tender and swollen joints | Not assessed |

| Emery, 199910 | Rheumatoid arthritis; 55 (20-85) years; 8% with ulcer | 200 mg bid (n=326) | — | Diclofenac 75 mg bid (n=329) | 24 | ACR-20 responder index, changes in painful or tender and swollen joints | Incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy |

| Study 05414 | Osteoarthritis of hip; 63 (28-93) years; 12% with ulcer | 100 mg bid (n=207); 200 mg bid (n=213) | n=218 | Naproxen 500 mg bid (n=207) | 12 | WOMAC index | Not assessed |

| Study 0628 | 389 (72%) with osteoarthritis; 148 (28%) with rheumatoid arthritis; 57 (22-86) years; 21% with ulcer | 200 mg bid (n=270) | — | Naproxen 500 mg bid (n=267) | 12 | No disease specific efficacy outcome | Incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy |

| Study 0719 | 812 (74%) with osteoarthritis; 287 (26%) with rheumatoid arthritis; 57 (22-87) years; 12% with ulcer | 200 mg bid (n=366) | — | Diclofenac 75 mg bid (n=387); ibuprofen 800 mg tid (n=346) | 12 | No disease specific efficacy outcome | Incidence of ulcers detected by endoscopy |

| Silverstein, 200011 | 5746 (73%) with osteoarthritis; 2183 (28%) with rheumatoid arthritis; 61 (18-90) years; 8% with ulcer | 400 mg bid (n=3987) | — | Diclofenac 75 mg bid (n=1996); ibuprofen: 800 mg tid (n=1985) | 26-52 weeks | No disease specific efficacy outcome | Incidence of symptomatic ulcers, bleeds, perforations, and obstructions confirmed by endoscopy |

WOMAC=Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index; ACR-20=American College of Rheumatology; bid=twice daily; tid=three times daily.

Acknowledgments

Mark Layton (Pfizer) and Anne Hopkins (Searle) provided input into the review protocol and facilitated access to the full trial reports.

Editorial by Jones

See also p 624

Footnotes

Funding: Additional funding was provided to the Centre for Statistics in Medicine by Pfizer and Searle (now part of Pharmacia).

Competing interests: The review was undertaken independently at the Centre for Statistics in Medicine. LAS is employed on a fellowship funded by Pfizer. JJD has acted as a paid consultant to Pfizer and Pharmacia. MDB is an employee of Pfizer. The review was prepared as part of the submission to the UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence for appraisal of COX 2 selective inhibitors.

References

- 1.Hawkey CJ. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcers. BMJ. 1990;300:278–284. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6720.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blower AL, Brooks A, Fenn GC, Hill A, Pearce MY, Morant S, et al. Emergency admissions for upper gastrointestinal disease and their relation to NSAID use. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:283–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.d01-604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tramer MR, Moore RA, Reynolds DJ, McQuay HJ. Quantitative estimation of rare adverse events which follow a biological progression: a new model applied to chronic NSAID use. Pain. 2000;85:169–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.British Medical Association; Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British national formulary. London: BMA, RPS; 2000. pp. 447–455. (No 39). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care. London: BMJ Publishing; 2001. pp. 285–312. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bensen WG, Fiechtner JJ, McMillen JI, Zhao WW, Yu SS, Woods EM, et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis with celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:1095–1105. doi: 10.4065/74.11.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon LS, Weaver AL, Graham DY, Kivitz AJ, Lipsky PE, Hubbard RC, et al. Anti-inflammatory and upper gastrointestinal effects of celecoxib in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1921–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.20.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Study 62. Integrated clinical and statistical report for a multicenter, double blind, parallel group study comparing the incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer associated with SC-58635 200 mg with that of naproxen 500 mg BID taken for 12 weeks in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacia: Data on file. 1997.

- 9. Study 071. Integrated clinical and statistical report for a multicenter, double blind, parallel group study comparing the incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer associated with SC-58635 200 mg BID with that of diclofenac 75 mg BID and ibuprofen 800 mg TID, taken for 12 weeks in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacia: Data on file. 1998.

- 10.Emery P, Zeidler H, Kvien TK, Guslandi M, Naudin R, Stead H, et al. Celecoxib versus diclofenac in long-term management of rheumatoid arthritis: randomised double-blind comparison. Lancet. 1999;354:2106–2111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, Simon LS, Pincus T, Whelton A, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib long-term arthritis safety study. JAMA. 2000;284:1247–1255. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao SZ, Fiechtner JI, Tindall EA, Dedhiya SD, Zhao WW, Osterhaus JT, et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life of rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with celecoxib. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:112–121. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)13:2<112::aid-anr5>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao SZ, McMillen JI, Markenson JA, Dedhiya SD, Zhao WW, Osterhaus JT, et al. Evaluation of the functional status aspects of health-related quality of life of patients with osteoarthritis treated with celecoxib. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:1269–1278. doi: 10.1592/phco.19.16.1269.30879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Study 054. Integrated clinical and statistical report for a double-blind placebo controlled, randomised comparison study of the efficacy and safety of SC-58635 50 mg, 100 mg and 200 mg BID and naproxen 500 mg BID in treating the signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis of the hip. Pharmacia: Data on file. 1997.

- 15.Singh G, Goldstein J, Fort J, Bello A, Boots S. Success-I in osteoarthritis (OA) trial: celecoxib has similar efficacy to the conventional NSAIDS [abstract] J Rheumatol. 2001;28(suppl 6.3):6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottlieb S. Researchers deny any attempt to mislead the public over JAMA article on arthritis drug. BMJ. 2001;323:301. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jüni P, Rutjes AWS, Dieppe PA. Are selective COX 2 inhibitors superior to traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs? BMJ. 2002;324:1287–1288. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7349.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR study group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]