Abstract

Long COVID has emerged as a major global health concern, yet the long-term trajectory of immune recovery and its contribution to persistent symptoms remain to be elucidated. Here, we conducted a three-year longitudinal follow-up of the 47 COVID-19 patients and applied single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and multiplex cytokine profiling to comprehensively characterize the peripheral immune landscape during convalescence. We observed persistent immune dysregulation up to three years post-infection, characterized by chronic inflammation and impaired restoration of naïve CD4⁺ T cells, naïve CD8⁺ T cells, and SLC4A10⁺ MAIT cells—features reminiscent of immunosenescence. Notably, Th17 cells, rather than monocytes, emerged as key drivers of chronic inflammation beyond one year. We identified two distinct Th17 subsets: RORC⁺ Th17 cells and LTB⁺ Th17 cells. While RORC⁺ Th17 cells were negatively correlated with inflammatory cytokine levels, LTB⁺ Th17 cells showed proinflammatory features and were positively associated with long COVID symptoms. Sustained elevation of S100A8 and IL-16 in follow-up patients may contribute to the persistent presence of LTB⁺ Th17 cells. Together, our study provides an in-depth longitudinal map of immune remodeling in COVID-19 convalescents, revealing key cellular and molecular drivers of sustained inflammation up to three years post-infection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s44466-025-00012-2.

Keywords: CD4+ T cells, Immunosenescence, Long COVID, ScRNA-seq, Inflammation, Longitudinal prospective study

Main

The molecular and cellular mechanism underlying the post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is not fully understood. Our previous longitudinal study revealed persistently elevated levels of CDKN1C+ nonclassical monocytes in convalescent patients at one-year post-recovery, which showed significant positive correlations with specific clinical manifestations of PASC [1]. However, whether these aberrant immune cell profiles and associated inflammatory states normalize over extended time periods remains unknown.

Here we report a three-year prospective study of COVID-19 patients following acute infection. We recruited 47 COVID-19 patients and conducted single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) alongside cytokine profiling to comprehensively characterize the longitudinal immune alterations.

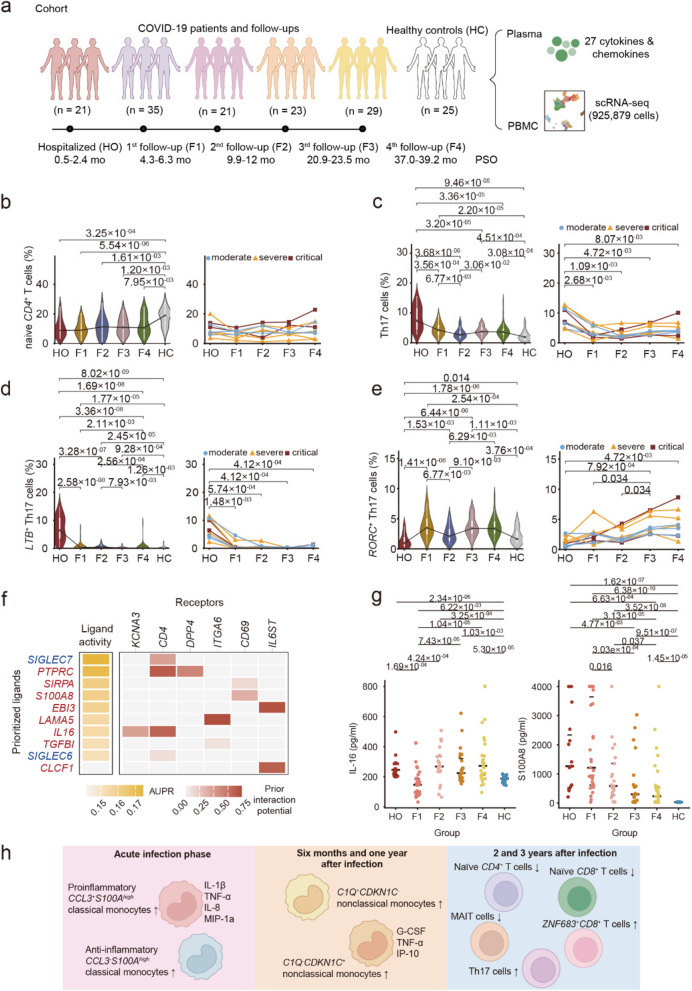

The cohort designed for scRNA-seq-based analysis consisted of 47 patients who underwent longitudinal immune profiling from hospitalization through a three-year follow-up period (Fig. 1a; Figure S1a). These patients were followed up at multiple time points, including hospitalization (HO) in March 2020, the first follow-up (F1) in July 2020, the second follow-up (F2) from December 2020 to January 2021, the third follow-up (F3) from November to December 2021, and the fourth follow-up (F4) from March to April 2023.The median age of the enrolled patients was 54.0 years (IQR: 44.0–61.5), with 48.9% (23/47) being male. Clinical severity and outcomes of these patients were documented (Table S1). There were finally 24 moderate, 14 severe and 9 critical infection cases, classified according to criteria described in our previous study [2]. Clinical progression during follow-up was also reviewed (Figure S1b; Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Study design and the characteristics of Th17 cells. a Flowchart of the experimental design. The number of COVID-19 patients enrolled during hospitalization (HO) and at subsequent follow-up stages (1st follow-up: F1, 2nd follow-up: F2, 3rd follow-up: F3, and 4th follow-up: F4) is depicted, along with the corresponding sampling times (in months) and time post symptom onset (PSO). b-e Temporal characteristics of naïve CD4+ T cells (c12), total Th17 cells, LTB+ Th17 cells (c11) and RORC+ Th17 cells (c06). Proportion of cells among the PBMCs in groups of all patients (left) and temporal changes in the 9 COVID-19 patients with follow-up data (right). f NicheNet analysis highlighted potential ligands regulating differential gene expression levels of LTB+ Th17 cells. Ligands coloured in red were specific in c11. g Comparison of IL-16 and S100A8 levels in all patients with long-term follow-up data. P values are shown (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test). h Overview of the changes of cell subsets and the secretion of related cytokines/chemokines at different stages of infection

In total, 136 peripheral blood samples were collected from the 47 COVID-19 patients across hospitalization and follow-up periods (Figure S1a). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from each blood sample were subjected to scRNA-seq and 925,879 cells were obtained after quality control (Table S3). The scRNA-seq analysis also included 25 healthy controls (HCs): 7 recruited in this study and 18 from published datasets [3, 4].

A total of 36 cell clusters with distinct transcriptional signatures were identified (Figure S2a, b; Table S4). We first investigated the longitudinal changes by an enrichment analysis based on RO/E. While NK cells, conventional dendritic cells and megakaryocytes showed progressive recovery, certain T cell subsets, monocytes, and plasma cells persisted with abnormalities throughout the three-year observation period (Figure S2c). The changes of these cell proportions were consistent with the RO/E results (Figure S3a–c). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to characterize the potential associations between different cell subtypes and temporal progression (Figure S3d). Plasma cytokines also demonstrated distinct longitudinal dynamics (Figure S4a; Table S5). Notably, the levels of IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-17, IL-4, IL-9 and MIP-1b remained elevated in convalescent patients compared to healthy controls even three years after infection (Figure S4b). These findings indicate a sustained inflammatory state, suggestive of persistent immune activation and unresolved immune perturbation in long-term COVID-19 convalescence.

Monocytes are key mediators of inflammation during both the acute phase and at one-year follow-up during convalescence, we therefore first investigated the temporal change in monocytes [1]. The CCL3+S100Ahigh classical monocytes (c30_Mono_CD14_CCL3+_S100Ahigh) were primarily enriched during hospitalization and are thought to play a proinflammatory role [1]. A rapid decline was observed in the proportion of CCL3+S100Ahigh classic monocytes following recovery, with levels dropping below those of healthy controls by the F1, F2, F3 and F4 time points (Figure S5a). In contrast, the CCL3¯S100Ahigh classical monocytes (c31_Mono_CD14_CCL3¯_S100Ahigh) exhibited a progressive increase in abundance post-acute infection. This subset continued to accumulate in the peripheral blood during convalescence and was suggested to exert anti-inflammatory functions (Figure S5b–d). We previously identified two subsets of nonclassical monocytes in COVID-19 convalescent patients: c34_Mono_FCGR3A_CDKN1C and c35_Mono_FCGR3A_C1QA [1]. CDKN1C+ nonclassical monocytes exhibited a proinflammatory cytokine profile and showed significant association with persistent PASC symptoms. By the third year of follow-up, the level of c34 cells were comparable to those in healthy controls (Figure S5e). The C1Q+ nonclassical monocytes (c35_Mono_FCGR3A_C1QA), which serve as precursors for CDKN1C+ nonclassical monocytes, along with intermediate monocytes (c33_Mono_CD14_FCGR3A), showed significantly decreased proportions by F1 (Figure S5f-g). Although their levels remained higher than those in healthy controls at F4, both c33 and c35 exhibited recovery trends over time. In addition, c29_Mono_CD14_ISG15 and c32_Mono_CD14low subsets also progressively normalized, reaching frequencies comparable to healthy reference ranges by 2 and 3 years of follow-up (Figure S5h-i), though c32 levels remained modestly higher than healthy controls at F4.

The restoration of proinflammatory monocyte levels to normal ranges suggests that sustained systemic inflammation during the 2–3 year of follow-up period is likely mediated by other immune cell population. Analysis of cell proportions changes across all patients and nine consecutive follow-up subsets revealed that naïve CD4+ T cells (c12_T_CD4_naive_CCR7), naïve CD8+ T cells (c14_T_CD4_naive_CCR7) and SLC4A10+ MAIT (c19_MAIT_SLC4A10) remained incompletely restored during the convalescent phase, maintaining levels significantly below those observed in healthy controls (Fig. 1b; Figure S6a, b). A decrease in the proportion of naïve CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells is associated with immunosenescence [5, 6]. We therefore adjusted the age difference between patients and heathy controls to explore the possibility of immunosenescence in these patients. The proportions of naïve CD4⁺ T cells (c12_T_CD4_naive_CCR7) in the follow-up group remained significantly lower than those in healthy controls after age difference adjustment (Figure S6c; Table S6), indicating a potential state of immunosenescence in these recovered patients. A lower proportion of SLC4A10+ MAIT cells (c19_MAIT_SLC4A10) was also observed in patients with severe and critical COVID-19 during the acute infection phase compared to healthy controls (Figure S6d), suggesting a potential association with disease severity, consistent with previous reports [4, 7]. In contrast to the subsets described above, ZNF683+CD8+ T cells (c17_T_CD8_ZNF683) remained at elevated levels compared to healthy controls throughout the follow-up period (Figure S6e).

Of note, the overall level of Th17 cell subsets were consistently higher in follow-up patients than in healthy controls (Fig. 1c; Figure S7a, b). Correspondingly, IL-17 levels, a cytokine secreted by Th17 cells [8], were also elevated in convalescent patients compared to controls. However, the two subsets of Th17 cells, c06 and c11, exhibited distinct properties. A higher proportion of LTB⁺ Th17 cells was found in COVID-19 patients during the acute infection phase compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1d), suggesting their involvement in the acute immune response. During follow-up, both the nine patients with longitudinal data and the entire cohort showed a decreasing trend in the proportion of LTB⁺ Th17 cells at F1. In contrast to this, the population of RORC+ Th17 cells exhibited increasing levels following recovery from acute infection (Fig. 1e). The abundance of c11 cells was positively correlated with plasma levels of IL-4, IL-9, IL-17, IL-1β, IFN-γ, and MIP-1b, suggesting that this subset may play regulatory roles in proinflammatory responses (Figure S7c, d). Conversely, the level of c06 cells was negatively correlated with the plasma concentration, indicating a potential anti-inflammatory role (Figure S7e, f). Moreover, differential gene expression analysis demonstrated that RORC+ Th17 cells were characterized by high expression of genes such as S100A4, S100A10, S100A11, LGALS3, and ANXA2, which are implicated in T cell migration, and regulation of T cell activation. While LTB⁺ Th17 cells were enriched in genes related to the activation of immune response and response to type I interferon, further confirmed its proinflammatory role (Figure S7g, h).

Integrative analysis revealed that the abundance of LTB⁺ Th17 cells in PBMCs was positively associated with several long COVID symptoms, including anxiety or depression, chest pain, pain or discomfort, and smell disorders (Figure S7i), which are frequently reported in COVID-19 convalescent patients [2, 9–11]. Meanwhile, the increasing abundance of anti-inflammatory RORC+ Th17 cells was negatively associated with the clinical symptom of muscle weakness (Figure S7j).

We applied NicheNet analysis to explore the molecular drivers of the LTB⁺ Th17 cells and RORC+ Th17 cells (Fig. 1f; Figure S7k). The results revealed that these two clusters shared several regulatory ligands, including SIGLEC7 and SIGLEC6. In addition, distinct ligands were predicted to selectively regulate each subset. LTB⁺ Th17 cells were more likely regulated by PTPRC, SIRPA, S100A8, EBI3, LAMA5, IL16, TGFBI and CLCF1, while RORC+ Th17 cells were potentially modulated by JAM3, CCL3, NAALADL1, COL18A1 and others. Calprotectin (S100A8/A9) acts as an alarmin that mediates host proinflammatory responses during infection and has been proposed as a potential biomarker for COVID-19 [12]. Similarly, IL-16 is a chemoattractant for CD4+ leukocytes, exerting proinflammatory effects via interactions with CD4 and CD9 [13]. Since both S100A8/9 and IL-16 are secreted into circulation, we quantified their plasma levels in follow-up patients. Both S100A8 and IL-16 were significantly elevated in the third year of follow-up groups, in accord with the persistent presence of the c11 cell subset (Fig. 1g; Table S7). Moreover, in vitro stimulation of PBMCs with S100A8/A9 and IL-16 increased the proportion of RORC+IFI44L+ Th17 cells, validating their role in inducing LTB+ Th17 cells (Figure S8).

In summary, our findings reveal persistent immune dysregulation lasting up to three years post-recovery, characterized by chronic inflammation and diminished naïve CD4+ T cell levels—features reminiscent of immunosenescence (Fig. 1h). Mechanistically, T cells, particularly Th17 cells, rather than monocytes, were identified as the key drivers of sustained inflammation beyond one year. Selective inhibition of pathogenic Th17 subsets might be a potential therapy for long COVID.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Biomedical High Performance Computing Platform of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences for providing computational support.

Authors’ contributions

Jianwei Wang, Bin Cao, and Lili Ren conceived the study. Yan Xiao, Chao Wu, and Li Guo generated the sequencing data. Jianwei Wang, Lili Ren, Bin Cao, Xianwen Ren, and Tian Zheng designed the data analysis strategies and approaches. Ru Gao, Yiwei Liu, and Chao Wu performed the data analysis and generated the figures. Bin Cao, Yeming Wang, and Rongling Zhang performed the clinical characterization of the patients. Li Guo, Xinming Wang, Jingchuan Zhong, Lan Chen, and Ying Wang processed and handled patient samples. Xianwen Ren, Tian Zheng, and Ru Gao drafted the manuscript. Jianwei Wang, Lili Ren, and Bin Cao finalized the manuscript with input from the other authors. Jianwei Wang supervised the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2022-I2M-CoV19-005, 2020-I2M-CoV19-011, 2023-I2M-2-001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81930063, 82221004), the Nonprofit Central Research Institute Fund of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2019PT310029) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3332021092).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text and the supplementary materials. The raw sequencing data have been deposited at the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB) under accession numbers HRA002003 and HRA012072, and are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Jin Yin-tan Hospital (KY-2020-02.01, KY-2020–80.01). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The corresponding author Jianwei Wang is a member of the Editorial Board of the journal Immunity & Inflammation. However, he was not involved in the peer-review or decision-making process for this manuscript. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tian Zheng and Ru Gao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xianwen Ren, Email: renxwise@cpl.ac.cn.

Bin Cao, Email: caobin_ben@163.com.

Lili Ren, Email: renliliipb@163.com.

Jianwei Wang, Email: wangjw28@163.com.

References

- 1.Ren L, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Longitudinal landscape of immune reconstitution after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection at single-cell resolution. Sci Bull. 2025;70:323–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:747–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang JY, Wang XM, Xing X, et al. Single-cell landscape of immunological responses in patients with COVID-19. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren X, Wen W, Fan X, et al. COVID-19 immune features revealed by a large-scale single-cell transcriptome atlas. Cell. 2021;184:1895–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mogilenko DA, Shchukina I, Artyomov MN. Immune ageing at single-cell resolution. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:484–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia T, Zhou Y, An J, et al. Benefit delayed immunosenescence by regulating CD4+ T cells: a promising therapeutic target for aging-related diseases. Aging Cell. 2024;23:e14317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson E, Reynolds G, Botting RA, et al. Single-cell multi-omics analysis of the immune response in COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021;27:904–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubberts E. The IL-23-IL-17 axis in inflammatory arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:415–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2128568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blomberg B, Mohn KG, Brokstad KA, et al. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med. 2021;27:1607–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Mellett L, Khader SA. S100A8/A9 in COVID-19 pathogenesis: impact on clinical outcomes. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2022;63:90–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Zhang J, Zhao W, Zhou Y, et al. Pyroptotic T cell-derived active IL-16 has a driving function in ovarian endometriosis development. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5:101476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text and the supplementary materials. The raw sequencing data have been deposited at the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB) under accession numbers HRA002003 and HRA012072, and are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/.