Abstract

Neonatal respiratory monitoring is crucial for assessing breathing patterns, but the lack of real-time clinical data limits the development of machine learning (ML) models. This study provides a synthetic signal generation framework to replicate infant respiratory cycles with physiological fidelity. The dataset simulates normal and pathological breathing patterns such as apnea, hypoxia, and periodic breathing, including Gaussian noise and exponential functions, to maintain biological realism. A feature extraction pipeline was created to examine time- and frequency-domain characteristics, enabling the categorization of respiratory states using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), CNN - BiLSTM and Random Forests. The CNN-BiLSTM model achieved the highest classification accuracy of 96.16%, outperforming the standalone CNN and RF models. The results illustrate the possibility of synthetic neonatal data for ML-based respiratory distress assessment. This architecture can be further extended for hardware implementation using e-textile-based respiratory monitoring. Real neonatal dataset integration and clinical validation of ML-DL models will be the main goals of future research to improve their robustness and applicability.

Keywords: Neonatal respiratory monitoring, Machine learning in NICU, Synthetic biomedical signal generation, Apnea and hypoxia classification

Subject terms: Computational science, Medical research

Introduction

Neonatal respiratory monitoring plays a crucial role in assessing breathing patterns and identifying possible complications in newborns, especially preterm infants. Preterm birth, defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation, is a pressing global health issue, affecting over 10% of newborns worldwide and contributing significantly to neonatal morbidity and mortality1. These newborns are typically admitted to Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs) due to their immature respiratory systems, making constant monitoring, which is critical for early diagnosis of respiratory distress, apnea, and abnormal breathing patterns2.

Traditional neonatal monitoring techniques rely on contact-based physiological sensors, including pulse oximeters, electrocardiogram (ECG) electrodes, respiratory belt transducers, and nasal thermocouples. While effective, these strategies face several challenges, including the fragility of neonatal skin, where prolonged exposure to adhesive electrodes can lead to skin injuries and infections. Additionally, sensor displacement caused by movement artifacts in the NICU environment often results in signal degradation and inaccurate readings. The invasiveness of electrodes and belt-based sensors may also interfere with normal breathing and comfort, ultimately reducing the accuracy of long-term monitoring2.

To circumvent these constraints, recent research has examined non-contact respiratory monitoring techniques, including thermal imaging, radar-based tracking, and video-based photoplethysmography (PPG) analysis3,4. While promising, these approaches suffer from motion artefacts, noise sensitivity, and high computing costs5. Moreover, a fundamental difficulty in neonatal respiratory research remains the paucity of large-scale neonatal respiratory datasets, which inhibits the training and validation of ML models.

Study objective

To address these difficulties, this study provides a synthetic signal generation system to simulate neonatal respiratory cycles. The created dataset simulates normal and pathological breathing patterns, adding Gaussian noise and exponential functions to achieve biological realism6.

After producing the synthetic dataset, we extract time-domain and frequency-domain parameters, including mean respiratory amplitude, spectral entropy, peak frequency, and power spectral density (PSD). These features are then used to train machine learning classifiers, like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Random Forests, to discern between normal and pathological respiratory conditions. The primary contributions of this work include: (1) development of a physiologically accurate synthetic neonatal respiratory signal generation framework that addresses the scarcity of real-world datasets, (2) comprehensive feature extraction pipeline combining time-domain and frequency-domain characteristics for robust respiratory pattern analysis, and (3) comparative evaluation of machine learning approaches including CNN, CNN-BiLSTM, and Random Forest classifiers for automated respiratory distress detection. In addition, a suggested hardware pipeline is outlined to demonstrate how the proposed model could be aligned with real-time signal acquisition in clinical or wearable settings. This research establishes a foundation for scalable, non-invasive neonatal monitoring solutions that can potentially reduce dependency on contact-based sensors while maintaining high classification accuracy for critical respiratory conditions.

Related works

Neonatal health monitoring has seen significant advancements with the integration of smart textiles, IoT, and deep learning models for non-invasive sensing and predicting vital signs.

Cay et al.7 designed an e-textile-based respiratory sensing system specifically for neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) monitoring, leveraging smart textile pressure sensors to provide a non-invasive alternative to conventional monitoring methods. Deep learning approaches have also been explored for respiratory monitoring. Kumar et al.8 applied LSTM and Bi-LSTM models to predict respiratory rate from bio signals, achieving improved performance over traditional methods. Similarly, a breath-tracking system using Velostat was proposed by Hancılar and Ayten9, where a neoprene-based wearable system demonstrated high accuracy in detecting respiratory patterns. A study valuating neonatal respiratory rate estimation using pressure-sensitive mats compared time and frequency domain methods, showing that frequency-domain analysis provided higher accuracy6. Wearable sensor platforms are becoming a key solution for neonatal monitoring. Chen et al.3 designed an integrated sensor platform for NICU applications that combines ECG, SpO2, and temperature sensing. Similarly, a health monitoring vest using Velostat sensors was developed to track real-time vital signs and transmit them to cloud storage for remote analysis5.

Intelligent sensor systems have also been explored. Kciuk et al.10 introduced an artificial neural network-based Velostat pressure sensor mat, which enhances pressure mapping accuracy in neonatal and elderly patient monitoring. Shukla and Das11 proposed an IoT-based non-invasive NICU monitoring system using a Raspberry Pi camera for extracting iPPG signals to estimate heart rate and oxygen saturation. Neural network-based non-contact monitoring approaches were further advanced by Khanam et al.12, demonstrating a high correlation between digital camera-based measurements and ECG reference values. E-textile-based IoT solutions have been explored for neonatal healthcare. NeoWear, an IoT-connected wearable developed by Cay et al.13, integrated smart textile pressure sensors with an edge computing framework for continuous monitoring of neonatal respiration and apnea events. Predictive analysis of neonatal health parameters has also been a focus area, with Gee et al.1 proposing a point process-based prediction algorithm for bradycardia in preterm infants, achieving early detection with high accuracy.

Photoplethysmogram (PPG)-based real-time respiratory rate estimation has been another active research area. Park and Lee4 proposed an adaptive lattice notch filter (ALNF) for the real-time extraction of respiratory information from PPG signals, achieving enhanced tracking performance. In the domain of neonatal respiratory distress assessment, standardised definitions and monitoring guidelines have been outlined by Sweet et al.2 to ensure consistency in clinical trials and maternal immunisation safety studies. Advancements in multimodal sensor technology have also contributed to neonatal health monitoring. Martinez-Hernandez and Assaf14 introduced a soft tactile sensor with multimodal data processing, improving recognition accuracy for biomedical sensing applications. Another smart textile-based system, SolunumWear, was proposed by Cay et al.15, demonstrating real-world applicability for continuous respiration monitoring across different postures.

Recent studies have further enhanced neonatal monitoring using AI-driven and multimodal sensing technologies. Sitaula et al.16 explored artificial intelligence-based wearable systems for neonatal cardiorespiratory monitoring, demonstrating their potential for early disease detection. AI has also been applied to predict respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) in premature infants, as shown by Jang et al.17, where deep learning models improved early diagnosis and clinical decision-making. Paul et al.18 developed an energy-efficient wearable system for detecting respiratory anomalies in preterm newborns, optimising machine learning algorithms for low-power operation. Video-based respiration estimation has been another emerging area, with Manne et al.19 introducing a deep flow-based algorithm that accurately tracks infant respiration patterns from video footage. Ultrasound-based approaches have also gained interest, as highlighted by Gravina et al.20, who applied deep learn- ing to neonatal respiratory ultrasound for improved distress detection. Lastly, Grooby et al.21 demonstrated the feasibility of using AI-enhanced digital stethoscope recordings to predict neonatal respiratory distress, offering a non-invasive and cost-effective monitoring solution.

These studies highlight the rapid development of non-invasive neonatal monitoring solutions, integrating smart textiles, AI, and IoT-based frameworks to enhance early detection, reduce infant distress, and improve neonatal care in NICUs.

Materials and methods

Suggested hardware pipeline

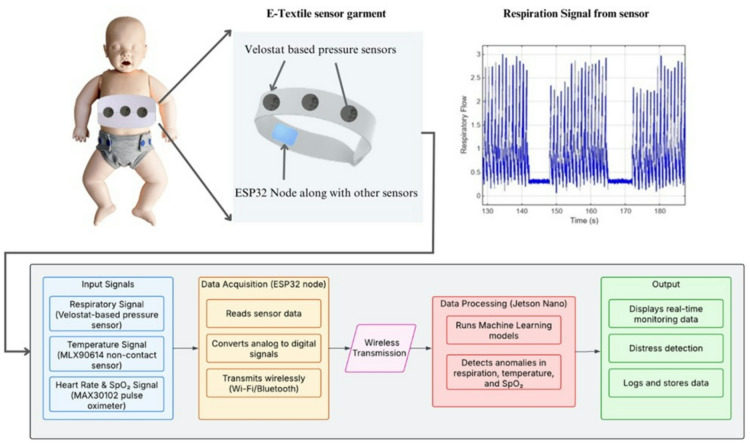

Alongside the model and synthetic data pipeline developed in this study, we present a suggested hardware setup that could collect relevant physiological signals in a real-world application. This pipeline, shown in Fig. 1, consists of three main components: sensing, processing, and transmission.

Fig. 1.

Block Diagram of the suggested hardware pipeline for collecting and processing signals compatible with the proposed classification model.

The sensing stage would involve non-invasive, fabric-based components capable of detecting respiratory movement and pulse activity, such as pressure-sensitive textiles or optoelectronic sensors. These types of sensors have been used in neonatal settings to minimise discomfort and improve long-term monitoring, as noted in recent studies16. The captured signals would then be preprocessed using a compact embedded system (e.g., microcontroller), which extracts and formats the relevant data before transmitting it wirelessly to an external monitoring interface or mobile device. This mirrors the input structure used in our model pipeline.

Given the limited availability of real neonatal data and constraints in acquiring long-term, high-quality signals, we developed a synthetic signal generator that produces respiratory and pulse-like waveforms aligned with the type of output expected from this pipeline. This helped ensure our model training and evaluation were based on realistic inputs, even in the absence of direct clinical data. While no physical hardware implementation is discussed in this work, the suggested pipeline provides a clear context for how the signal generation and classification approach presented here can be translated into a usable monitoring solution.

Synthetic data generation

The absence of real-time hardware data from pressure-based respiratory monitoring systems has constrained advancements in neonatal respiratory research. To address this, we developed a synthetic neonatal respiratory dataset that accurately mimics real-world physiological signals while incorporating clinically validated anomalies. The dataset was designed to simulate baseline respiratory cycles with physiological inhalation-exhalation asymmetry, natural variability, and pathological events such as apnea, and hypoxia. Tachypnea (RR > 60 bpm) and Bradypnea (RR < 30 bpm) are other clinically significant respiratory abnormalities.

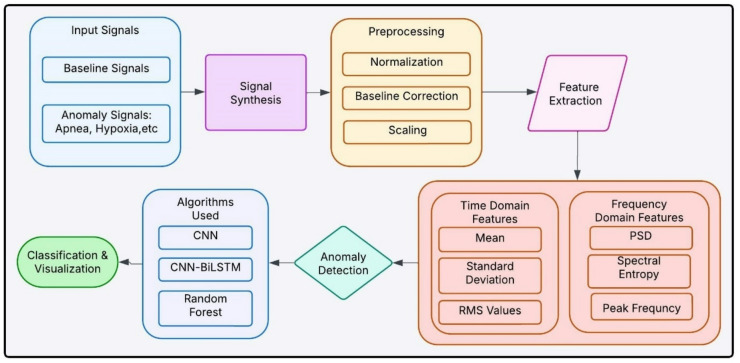

Figure 2 shows an overview of signal synthesis, preprocessing methods, feature extraction and machine learning models for anomaly detection and classification outputs for detecting respiratory anomalies in newborns. To ensure biological accuracy, exponential functions were employed to model inhale-exhale dynamics, as they more precisely represent neonatal airflow patterns compared to sinusoidal models. Exponential functions effectively capture the rapid inspiratory phase and the gradual decay of expiratory flow, consistent with neonatal breathing mechanics17. Gaussian noise was added to reflect natural respiratory variability, a well-documented feature of neonatal breathing signals18.

Fig. 2.

Block Diagram of synthetic data-based Neonatal Respiratory Monitoring.

To enhance dataset generalizability for machine learning applications, respiratory anomalies were introduced at randomised intervals, ensuring a diverse dataset capable of handling various clinical presentations of neonatal respiratory distress19. This randomised anomaly generation method improves model robustness in classifying respiratory anomalies, a key requirement for non-invasive NICU monitoring.

Baseline Respiratory Signal The baseline respiratory signal was modelled to replicate normal neonatal breathing patterns, incorporating physiologically accurate inhalation-exhalation asymmetry.

A sampling frequency of 100 Hz was used, consistent with neonatal respiratory signal acquisition standards, but remains adjustable based on sensor specifications16,19.

The respiratory rate was set between 30 and 60 breaths per minute (0.5–1 Hz), reflecting established neonatal respiration studies where preterm infants exhibit higher breathing rates than older children and adults.

Unlike sinusoidal breathing models, which assume symmetric airflow, neonatal respiration consists of rapid inhalation followed by a prolonged exhalation, which was accurately modelled using exponential functions instead of sinusoidal waves. This 40/60 inhalation-to-exhalation ratio aligns with research highlighting its role in effective gas exchange18. Equations (1)-(2) represents the mathematical form for inhale-exhale patterns.

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

The amplitude of the respiratory signal, representing relative airflow intensity, was set at 2.0 arbitrary units, consistent with clinical studies indicating peak amplitudes between 0.5 and 3.0 units, depending on sensor placement and individual variability.

The inhalation and exhalation cycles were concatenated to create a continuous respiratory waveform is presented in Eq. (4).

|

4 |

To introduce natural breath-to-breath variability, Gaussian noise was added and the resulting expression is presented in Eq. (5).

|

5 |

Studies confirm that neonatal respiratory signals exhibit small variability, primarily due to physiological and environmental influences9.

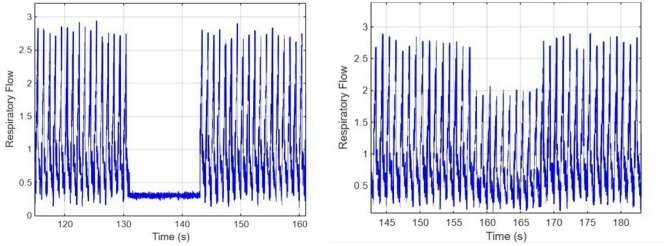

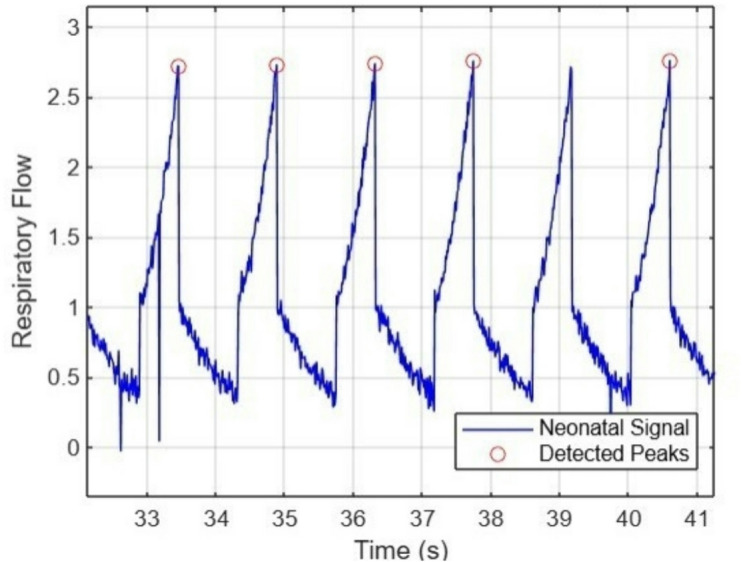

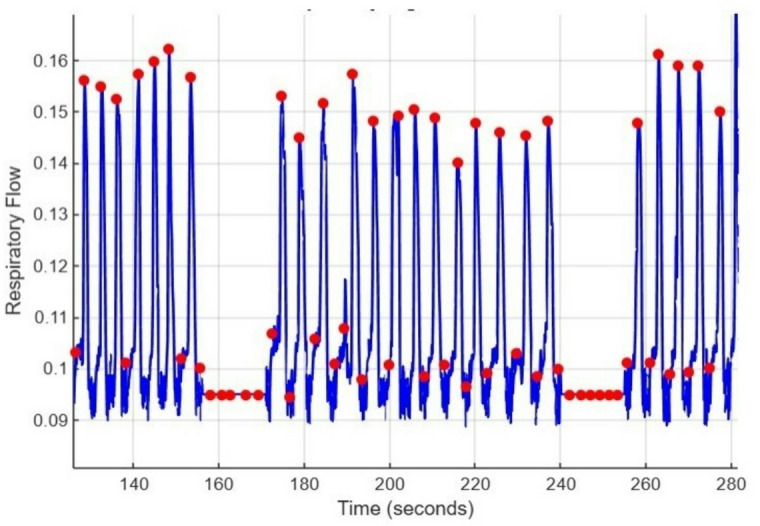

Peak detection is applied using findpeaks(), which estimates the respiratory rate (RR) in breaths per minute, a standard technique in neonatal respiratory analysis16. Figure 3 shows the normal respiratory pattern of neonates simulated using an exponential function for realistic inhale-exhale dynamics.

Fig. 3.

Baseline Respiratory signal with Detected peaks.

-

2.

Anomalous Respiratory Signal To replicate clinically relevant respiratory anomalies, we introduced pathological events into the baseline respiratory waveform, ensuring they closely mimic real neonatal respiratory distress conditions. The anomalies included apnea, hypoxia, and periodic breathing; each modelled using physiological justifications and mathematical representations.

Apnea Simulation: Apnea is defined as a complete cessation of breathing for at least 10 s, commonly observed in preterm neonates20. Apnea events were simulated by setting airflow to zero over randomized durations between 5 and 15 s to match neonatal apnea patterns. This event disrupts the baseline respiratory cycle, creating prolonged flat-line segments, a feature indicative of apnea in clinical recordings.

Hypoxia Simulation: Hypoxia is often a precursor to apnea, and its early detection is critical for neonatal intervention. The gradual amplitude reduction model aligns with pulse oximetry-based respiratory distress detection17.

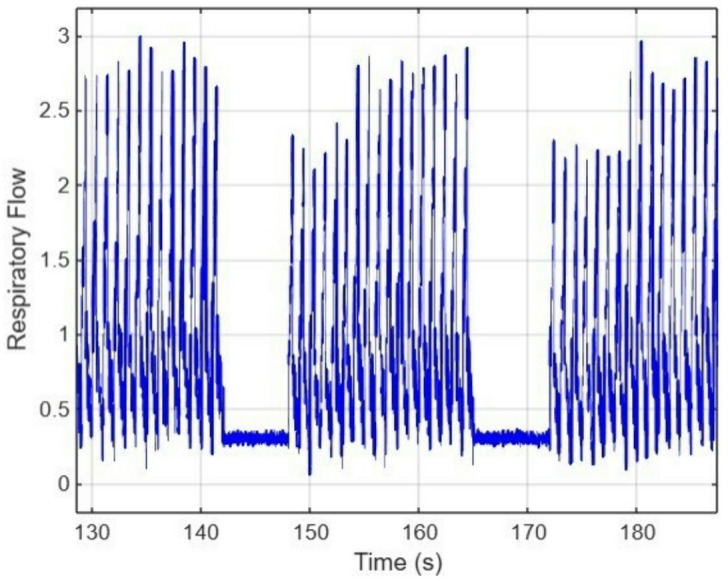

• Periodic Breathing Simulation: Periodic breathing consists of cycles of rapid breathing (hyperventilation) followed by short pauses (≤5 s), commonly occurring in preterm neonates20. The modelling approach included alternating high-amplitude oscillations (hyperventilation) and brief flat-line segments (pauses). The cycle length varied between 10 and 15 s, consistent with neonatal periodic breathing episodes21. The cycle length varied between 10 and 15 s, consistent with neonatal periodic breathing episodes21.

Figure 4 shows the neonatal respiratory signal during an Apnea event, which is characterized by a short pause in breathing, and the gradual reduction of the amplitude of the breathing signal as observed during the Hypoxia event. Figure 5 shows a combination of Apnea and Hypoxia events. To ensure dataset variability, all anomalies were embedded at random time intervals to avoid biasing ML models toward predefined event positions19. Event durations and severities were randomized within physiological constraints, ensuring alignment with NICU-recorded neonatal respiratory patterns21.

Fig. 4.

(a) Respiratory signal with Apnea cases (b) Respiratory signal with Hypoxia cases.

Fig. 5.

Respiratory signal with Apnea and Hypoxia cases

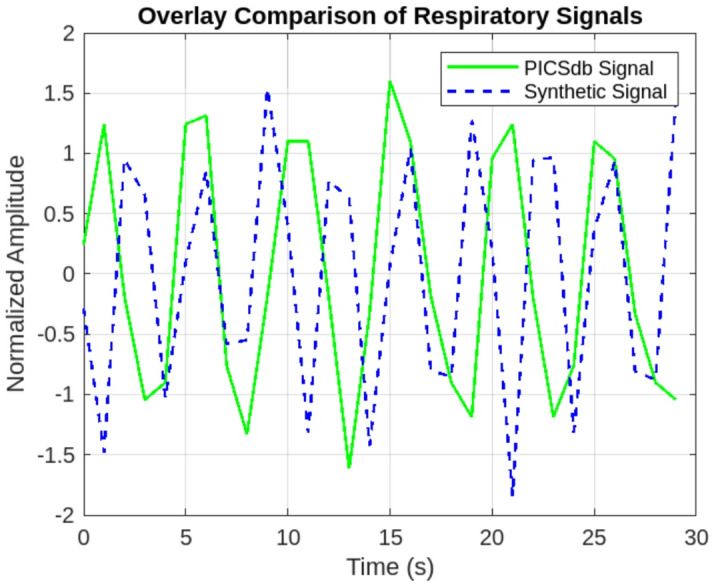

Validation Against Real NICU Respiratory Signals. To assess the realism of our synthetic respiratory signals, we compared them to real data from the PICSdb database1, which contains NICU recordings from premature infants. Specifically, we selected the abdominal respiratory channel from one infant (Infant 3) and extracted a 30-second window of data. We normalised and overlaid the synthetic and real signals using a matched sampling frequency of 50 Hz. As shown in Fig. 6, the synthetic waveform closely reproduces the characteristic frequency (0.5–1 Hz), amplitude variations (0.4–0.6 a.u.), and baseline drift observed in NICU recordings. This visual comparison supports the plausibility of the synthetic signal as a surrogate for neonatal respiration in model training.

Fig. 6.

Overlay of real NICU respiratory signals extracted from PICSdb database and synthetic respiratory signals generated by our model.

Data Preparation and Pre-Processing

For robust classification, the dataset was structured into segmented time-series windows that capture clinically relevant breathing patterns. The preprocessing steps included:

Segmentation: Each respiratory sequence was divided into 10-second windows with 50% overlap, ensuring sufficient temporal information while preventing loss of key breathing events.

Handling Missing Values: Any missing values were filled using Simple Imputer (strategy=’mean’), replacing them with the feature-wise mean to maintain consistency.

Train-Test Split: 70% of the data was allocated for training, while the remaining 30% was further split into validation (15%) and test (15%) sets. A stratified approach was used to preserve class distribution, ensuring a balanced representation of normal breathing, apnea, and hypoxia.

Data Reshaping for CNN-BiLSTM Input: Since deep learning models require specific input dimensions, the dataset was reshaped into 3D tensors following the format (samples, time steps, features). np.expand dims(X, axis=2) was used to ensure compatibility with Conv1D and BiLSTM layers.

Feature extraction

After preprocessing the neonatal respiratory signals, feature extraction was performed to transform raw waveforms into a structured dataset for machine learning. Both time-domain and frequency-domain features were extracted to capture key respiratory patterns and anomalies effectively.

Time-domain features

They capture morphological and statistical properties of the respiratory signal, providing insights into breathing irregularities. The extracted features include:

Mean Respiratory Amplitude: Represents the average airflow intensity.

Variance: Quantifies the spread of respiratory values over time.

Root Mean Square (RMS): Measures the energy content of the signal, useful for distinguishing normal breathing from hypoventilation states.

Peak-to-Peak Amplitude: Captures the difference between maximum and mini- mum amplitude within each time window.

Zero-Crossing Rate: Identifies changes in respiratory airflow direction, useful for detecting periodic breathing patterns.

Each of these features is commonly used in respiratory signal analysis to identify variations in breathing effort and airflow patterns21.

Frequency-domain features

Spectral analysis of respiratory signals provides a

deeper understanding of breathing rhythm and stability. We computed:

Power Spectral Density (PSD): Evaluated using Welch’s method to determine the dominant respiratory frequency.

Spectral Entropy: Measures signal complexity, useful in differentiating between periodic and chaotic breathing.

Peak Frequency: The most prominent frequency component, indicating respiratory rate19.

These frequency-domain features are essential for detecting hypoventilation, tachypnea, and apnea, as abnormal respiratory conditions often exhibit distinct spectral patterns18.

Feature Normalization and Scaling

To ensure uniform feature scaling across different signals, min-max normalization was applied to all extracted features, bringing values within the range (0,1). Equation (6) presents the normalized and scaled features.

|

6 |

This prevents any individual feature from dominating model training due to differing numerical scales16,19. Figure 7 shows how the smoothed respiratory signal looks with detected peaks.

Fig. 7.

Smoothed Respiratory signal with detected peaks.

Model implementation

To classify neonatal respiratory signals into normal breathing, apnea, and hypoxia, three different machine learning models were implemented: a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for temporal feature extraction, a CNN with Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (CNN-BiLSTM) to incorporate sequential learning for time-series analysis, and a Random Forest (RF) classifier using handcrafted features. Each model was trained and evaluated using the same dataset split.

All models were trained on 5-second input windows (500 samples at 100 Hz) with two channels: respiratory and PPG. The CNN-BiLSTM model began with two 1D convolutional layers: the first with 32 filters and the second with 64 filters (kernel size = 3), each followed by ReLU activation and max pooling (pool size = 2). A dropout layer (rate = 0.2) was added after the convolutional stack to reduce overfitting. The output was passed to a BiLSTM layer with 64 units, followed by a fully connected (dense) layer with 64 neurons and ReLU activation. Another dropout layer (rate = 0.3) was applied before the final dense output layer with 3 neurons and softmax activation, corresponding to the three predicted classes: normal breathing, apnea, and hypoxia. Figure 8 shows the model architecture diagram.

Fig. 8.

CNN-BiLSTM hybrid architecture.

The CNN model followed the same initial structure but excluded the BiLSTM layer. Hyperparameters were selected manually based on validation performance and overfitting trends observed during training.

The CNN model was designed to automatically extract local temporal patterns from respiratory signals. It consisted of two convolutional layers followed by fully connected layers, using ReLU activation and dropout regularisation to prevent overfitting. The model was optimised with the Adam optimiser and trained for 30 epochs with a batch size of 32. It achieved 93.0% accuracy, effectively learning discriminative features from respiratory waveforms.

While CNNs excel in capturing local temporal patterns, they cannot model temporal relationships in sequential data. To address this limitation, a CNN-BiLSTM model was implemented, integrating bidirectional LSTM layers after convolutional feature extraction. This hybrid approach allowed the model to process respiratory signals more effectively by considering both temporal and sequential patterns. The addition of BiLSTM layers significantly improved classification performance, achieving the highest accuracy of 94.7%. The model demonstrated superior detection of apnea and hypoxia by leveraging both local feature extraction and long-term temporal dependencies.

For comparison, a Random Forest (RF) classifier was trained using manually extracted time- and frequency-domain features. The model consisted of 100 decision trees, with key hyperparameters such as n_estimators, max_depth, and min_samples_split optimised using GridSearch with 5-fold cross-validation. Certain parameters, like random_state, were fixed to ensure reproducibility and reduce search complexity. While RF performed well in classifying apnea cases, it struggled with hypoxia detection due to its reliance on static features, frequently misclassifying it as normal breathing. Despite this limitation, RF achieved a 92.0% accuracy, making it a competitive yet less robust alternative to deep learning-based models.

In addition to the fixed train/validation/test split described above, we further evaluated the deep learning models using 5-fold stratified cross-validation to strengthen robustness. Each fold preserved the class distribution across Normal, Apnea, and Hypoxia. At the start of each fold, a fresh model was initialised and trained on four folds (80%) and validated on the held-out fold (20%). Early stopping (patience = 3 epochs) and Adam optimization were used in every fold.

We report the mean ± standard deviation across folds for accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and macro average precision (PR-AUC). Confusion matrices and PR curves were generated from the pooled out-of-fold predictions across all folds. This approach complements the single-split evaluation and provides an additional check that our findings are not artefacts of a particular partition. Calibration was assessed using reliability plots with 10-bin partitioning, comparing predicted probabilities with observed outcome frequencies for each class.

Results

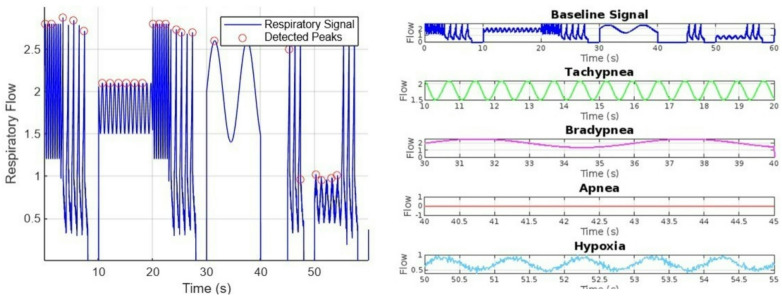

To evaluate neonatal respiratory classification, a synthetic dataset was generated, simulating various breathing conditions, including normal respiration, tachypnea, bradypnea, apnea, and hypoxia. These realistic neonatal respiratory signals were created, incorporating exponential functions and Gaussian noise to maintain biological accuracy. The dataset was used to train deep learning and machine learning models for automatic respiratory distress classification. Figure 9a illustrates the simulated neonatal respiratory waveforms, including the detection of respiratory peaks. The synthetic data was structured to capture distinct respiratory anomalies, ensuring the inclusion of clinically relevant patterns. Figure 9b shows different types of neonatal respiratory abnormalities, including tachypnea (rapid breathing), bradypnea (slow breathing), apnea (absence of breath), and hypoxia (low oxygen levels in respiration). These variations were further labelled and segmented for training AI models. The labelled dataset formed the basis for training and evaluating CNN, CNN-BiLSTM, and Random Forest models in subsequent sections.

Fig. 9.

(a) Respiratory signal with different anomalies, combined for comparative study (b) Waveforms of different respiratory conditions generated in the dataset, including normal breathing, tachypnea, bradypnea, apnea, and hypoxia, for comparison.

A performance comparison of the three models demonstrated the advantages of incorporating both convolutional and sequential learning mechanisms. The CNN-BiLSTM model outperformed the CNN and RF classifiers, achieving the highest classification accuracy. While the CNN model effectively extracted temporal features, its inability to model sequential dependencies limited its performance. In contrast, Random Forest (RF), which relied on handcrafted features, was computationally efficient but struggled to capture dynamic variations in respiratory patterns over time.

Figure 10 shows the confusion matrices of the two CNN models used. To validate the performance differences between models, statistical tests were conducted to assess their significance. The McNemar’s Test (p = 0.0001) confirmed that CNN-BiLSTM significantly outperformed CNN, demonstrating its superiority in handling sequential dependencies. Additionally, the Friedman Test (p = 0.0067) indicated a statistically significant difference in ranking across all models, further supporting the improved performance of CNN-BiLSTM over other architectures.

Fig. 10.

Confusion Matrix (a) CNN (b) CNN-BiLSTM.

A detailed evaluation of precision, recall, and F1-score metrics further highlighted the advantages of deep learning-based approaches, as tabulated in Table 1. CNN- BiLSTM demonstrated the highest precision for apnea (0.86) and hypoxia (0.90), whereas CNN achieved slightly lower scores. Random Forest showed a notable drop in precision for hypoxia detection, reinforcing the need for temporal modeling in respiratory classification.

Table 1.

Comparison of model performance for detection of hypoxia and Apnea.

| Model | Accuracy | Precision (Apnea) | Precision (Hypoxia) | F1- score (Overall) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 93% | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.92 |

| CNN-BiLSTM | 96.16% | 0.86 | 0.9 | 0.96 |

| Random Forest | 92.03% | 0.73 | 0.77 | 0.91 |

Cross-validated performance of deep models

Cross-validation confirmed the advantage of the sequence-aware CNN-BiLSTM. Table 2 compares 5-fold cross-validation performance across Random Forest, CNN, and CNN-BiLSTM models. The Random Forest achieved an accuracy of 92.6% ± 0.2% and macro PR-AUC of 0.79 ± 0.01. The CNN improved slightly to 93.1% ± 1.1% accuracy and 0.80 ± 0.06 PR-AUC. The CNN-BiLSTM outperformed both, with the highest accuracy (95.1% ± 0.2%) and macro PR-AUC (0.88 ± 0.01). These results confirm that incorporating temporal modelling provides a clear and consistent performance advantage.

Table 2.

Cross-validated performance of the models (5-fold stratified CV).

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1- score | Macro PR-AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 92.6% | 92% | 92.6% | 91.9% | 0.79 |

| CNN | 93.1% | 91.8% | 93.1% | 91.8% | 0.80 |

| CNN-BiLSTM | 95.1% | 94.9% | 95.1% | 94.7% | 0.88 |

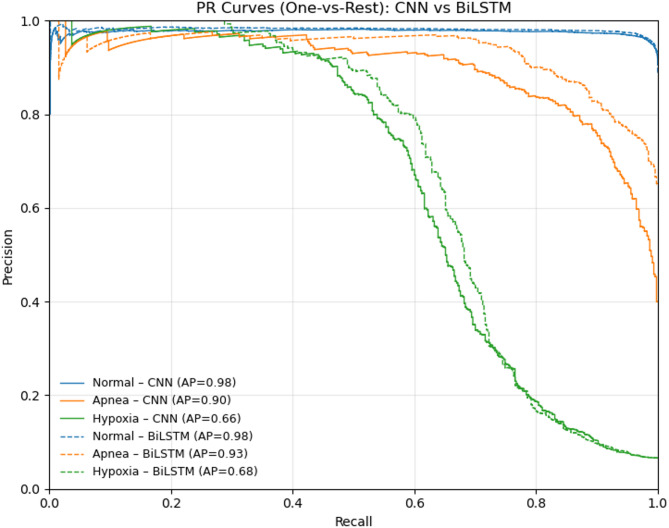

Figure 11 shows OvR ROC curves for each class. On the held-out test set, the CNN achieved AUCs of 0.91 (Normal), 0.99 (Apnea), and 0.96 (Hypoxia); the CNN–BiLSTM improved these to 0.93, 1.0, and 0.86, respectively. Corresponding OvR PR performance is reported in Fig. 12: average precision (AP) for CNN was 0.98 (Normal), 0.90 (Apnea), and 0.66 (Hypoxia), while CNN–BiLSTM reached 0.98, 0.93, and 0.68. Micro-averaged scores summarize overall performance (ROC-AUC: 0.986 → 0.988; AP: 0.966 → 0.972 from CNN to CNN–BiLSTM), confirming consistent gains with the hybrid model.

Fig. 11.

ROC -AUC Curves using a one-vs-rest (OvR) scheme for each class (Normal, Apnea, Hypoxia), comparing CNN (dashed) and CNN–BiLSTM (solid).

Fig. 12.

Precision-Recall (PR) curves using a one-vs-rest (OvR) scheme for each class (Normal, Apnea, Hypoxia), comparing CNN (dashed) and CNN–BiLSTM (solid).

The CNN-BiLSTM model significantly outperformed CNN, achieving AUC values of 0.93, 1.00, and 0.86 for Normal, Apnea, and Hypoxia classifications, respectively. The perfect AUC score (AUC = 1.00) for Apnea classification indicates that CNN-BiLSTM was able to completely separate Apnea cases from other classes. Similarly, the high AUC for Hypoxia (0.88) suggests strong classification performance.

Calibration analysis as presented in Fig. 13 confirmed that model probabilities closely reflected true outcome frequencies. CNN predictions were well calibrated for the Normal class but less consistent for Apnea and Hypoxia. CNN–BiLSTM improved calibration across all classes, particularly the minority ones, ensuring that predicted probabilities more accurately corresponded to observed event rates. This reliability is critical for clinical use, as it enables thresholds to be set with confidence, reducing both false alarms and missed detections.

Fig. 13.

Calibration curves for (a) CNN and (b) CNN–BiLSTM.

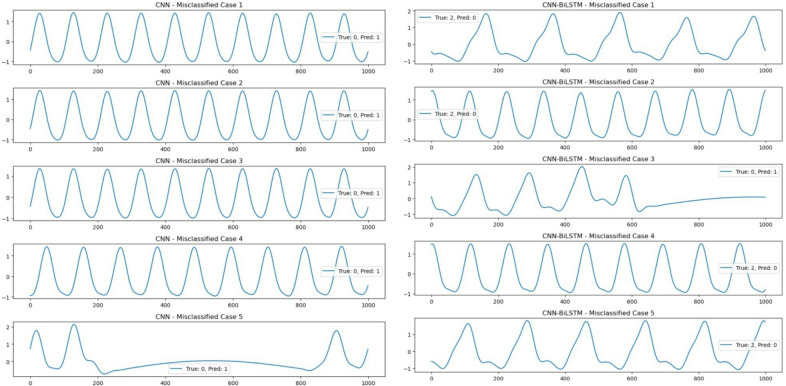

To gain further insights into model performance, we analysed misclassified cases from both the CNN and CNN-BiLSTM models. The misclassified instances, as shown in Fig. 14, highlight key patterns in erroneous predictions. The figures display misclassified signal segments from the test set for both CNN and CNN-BiLSTM models. Each subplot represents a single misclassified instance where the x-axis denotes time (sample points), the y-axis represents the amplitude of the respiratory signal, and the legend indicates the true class of the signal and the incorrectly predicted class by the model. The majority of errors in CNN-based classification were observed in signals that exhibit a high degree of periodicity, closely resembling class 0 (normal breathing). Many of these signals, despite belonging to abnormal classes (e.g., apnea or hypoxia), appear visually similar to normal patterns, which may have led to their misclassification. This suggests that the CNN model may be overfitting to periodic features, failing to distinguish subtle but critical abnormalities.

Fig. 14.

Misclassified signal segments from the CNN and CNN BiLSTM models, where each subplot represents a respiratory signal with true class and predicted class are indicated in the legend.

While CNN-BiLSTM demonstrated higher classification performance overall, its misclassifications were often associated with signals that exhibit transient irregularities. Many of these errors occur in cases where the signal transitions between two states, such as an apnea episode followed by normal breathing. This suggests that while the BiLSTM component effectively captures temporal dependencies, it may still struggle with borderline cases where signal features exhibit overlapping characteristics across different classes. These observations suggest that while the addition of temporal modelling in CNN-BiLSTM improves performance, further refinement of feature extraction techniques or the inclusion of additional physiological markers may enhance classification reliability.

The evaluation results demonstrate the effectiveness of deep learning models, particularly the CNN-BiLSTM architecture, in classifying neonatal respiratory signals. These findings highlight the importance of sequence-aware architectures in neonatal respiratory classification. While CNN and RF provided valuable insights, CNN-BiLSTM emerged as the most robust approach, demonstrating superior classification of apnea and hypoxia cases. The next section explores these results in greater depth, discussing model limitations, clinical implications, and future research directions.

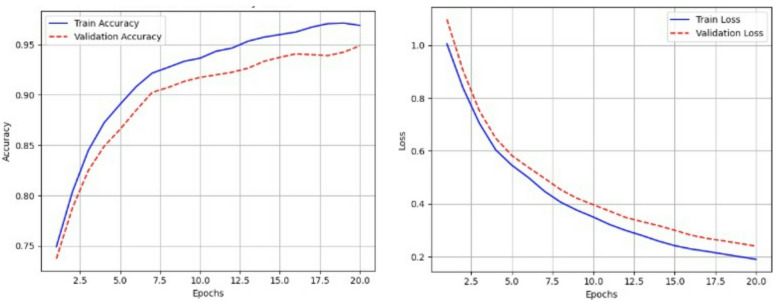

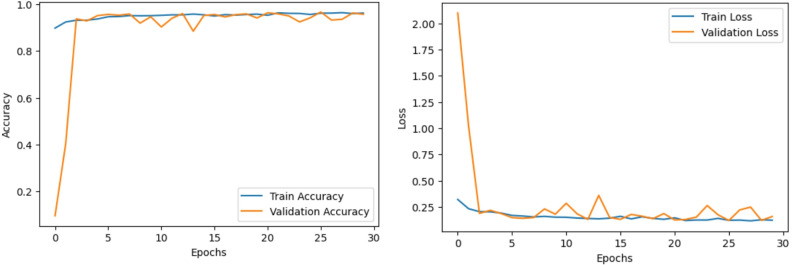

Figures 15 and 16 show the accuracy and loss curves of the CNN and CNN BiLSTM models, respectively. This study successfully validated synthetic neonatal respiratory signal modelling and ML-based classification. Moving forward, we are extending this work by developing hardware for real-time respiratory data collection, integrating additional physiological signals such as SpO2 and heart rate variability (HRV). The ML pipeline will be integrated with real-time sensor data processing for deployment in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). The goal is to develop a robust and reliable neonatal health monitoring system capable of automatically detecting respiratory distress conditions in preterm infants and enhancing early intervention in NICU settings.

Fig. 15.

Accuracy and Loss Curves while training and validating the CNN model.

Fig. 16.

Accuracy and Loss Curves while training and validating the CNN BiLSTM model.

Discussion

The results of this work illustrate the viability of synthetic neonatal respiratory signal creation for training deep learning and machine learning (ML) models in respiratory distress classification. Due to the restricted availability of true neonatal datasets, this work constructed a synthetic dataset that replicates normal and abnormal neonatal breathing patterns, including apnea, hypoxia, and periodic breathing. The synthetic dataset captures physiological variability by employing exponential functions and Gaussian noise modeling, making it well-suited for training AI-driven classification systems20,21.

Feature extraction strategies focused on both time-domain and frequency-domain parameters, collecting key respiratory markers such as mean respiratory amplitude, spectral entropy, power spectral density (PSD), and peak frequency22. These retrieved features enabled accurate categorization of respiratory diseases using deep learning-based classifiers, with CNNs achieving a classification accuracy of 93% and CNN- BiLSTM further improving performance to 96.16%. In comparison, Random Forest classifiers obtained an accuracy of 92.03%, illustrating the superior ability of CNN-based models to learn temporal correlations from respiratory data. The addition of BiLSTM layers to CNN significantly improved classification performance by enhancing the model’s ability to process sequential dependencies, particularly in detecting hypoxia cases, which often exhibit gradual amplitude changes rather than distinct pauses.

Table 3 presents the performance comparison of CNN and CNN-BiLSTM models, incorporating 95% confidence intervals (CI) to illustrate the reliability of each metric. CNN-BiLSTM outperforms CNN across all evaluation parameters, achieving higher accuracy and precision, with narrower confidence intervals indicating greater stability in predictions. The F1-score also reflects this trend, reinforcing CNN-BiLSTM’s superior balance between precision and recall. The inclusion of CIs highlights the robustness of the model performance, demonstrating that CNN-BiLSTM provides more consistent and reliable classification results.

Table 3.

Comparison of model performance with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

| Model | CNN | CNN BiLSTM |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 93% (91.6% − 94.4%) | 96.16% (94.8% − 97.52%) |

| Precision | 0.74 (0.727–0.753) | 0.86 (0.847–0.873) |

| F-1 Score (Overall) | 0.92 (0.908–0.932) | 0.96 (0.948–0.972) |

A fundamental advantage of this approach is its potential hardware implementation for real-time neonatal respiratory monitoring. Existing contact-based monitoring technologies such as pulse oximeters and ECG electrodes are sometimes intrusive, cause skin discomfort, and may introduce motion artifacts23. Non-invasive techniques such as thermal imaging, radar-based tracking, and video-based monitoring have been examined but suffer from motion artifacts, high processing costs, and environmental sensitivity24,25. Deep learning models such as CNN-BiLSTM, which demonstrate high classification accuracy, could be integrated into real-time monitoring systems to enhance neonatal respiratory assessment while reducing dependency on contact-based sensors.

Alongside better accuracy and PR-AUC, the calibration results highlight another important strength of our CNN–BiLSTM model: it produces probability estimates that can be trusted. In a clinical setting, it is not enough for a model to classify correctly; its confidence also needs to reflect reality. If a model is poorly calibrated, it may raise too many false alarms or, worse, fail to detect critical events. We found that CNN–BiLSTM not only improved the detection of apnea and hypoxia but also gave probability scores that matched the actual likelihood of these events. This combination of higher accuracy and reliable probabilities makes the model more suitable for neonatal monitoring, where clinicians must balance sensitivity with confidence in automated alerts.

A potential substitute is e-textile-based respiratory monitoring, specifically Velostat-based pressure sensors. Velostat, a conductive polymer substance, exhibits a change in resistance with the application of pressure, making it a good choice for real-time respiration tracking. By sandwiching the Velostat between two conductive electrode foils, a flexible, wearable breath rate sensor can be constructed to measure chest expansion and contraction during breathing14. This method provides a non-invasive, lightweight, and comfortable alternative to traditional NICU respiratory monitoring equipment, which could be further enhanced by integrating AI-based classification models for automated distress detection.

Error analysis revealed that CNN-BiLSTM had the lowest misclassification rate (3.84%), while CNN misclassified 13.22% of samples, suggesting that it struggled with false positives. Random Forest maintained a 7.97% misclassification rate, showing that handcrafted feature extraction still holds relevance for structured respiratory analysis. Table 4 gives a comparative analysis of the error (misclassification) of the models used in this study.

Table 4.

Error analysis comparison of the models.

| Model | Misclassification type | Common error class | Misclassification rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | False positives | Class 0 → 1 | 13.22% |

| CNN-BiLSTM | Lowest errors | Class 2 → 0 | 3.84% |

| Random Forest | Moderate errors | Class 2 → 0 | 7.97% |

Despite these promising results, some challenges and limitations must be addressed. First, synthetic data, while beneficial for model training, may not adequately replicate the physiological variability of real neonatal breathing patterns. Although Gaussian noise was included to imitate breath-to-breath changes, real newborn respiration is influenced by external factors such as movement, oxygenation fluctuations, and airway resistance, which are not fully reflected in the current dataset6. Additionally, while CNN-BiLSTM performed better in hypoxia classification than CNN and RF, some cases of hypoxia remained difficult to distinguish from normal breathing due to the gradual nature of the amplitude reduction. This suggests that multi-modal inputs, such as heart rate variability and oxygen saturation levels, could be incorporated to improve classification robustness.

Another challenge is that the synthetic dataset does not reflect long-term behavioural fluctuations that may affect genuine neonatal respiration. Conditions such as transient apnea, intermittent airway blockages, and periodic breathing abnormalities develop over extended durations. A potential enhancement would be to include longitudinal synthetic modelling to further replicate dynamic neonatal breathing trends8. Additionally, while deep learning models outperformed traditional classifiers, their performance in a real-world clinical scenario remains untested. Synthetic training alone is insufficient for real-time deployment, necessitating validation with real NICU respiratory data to bridge the gap between theoretical modelling and clinical implementation. Additionally, a single 15% test split was used for all evaluations to maintain consistency across experiments. While cross-validation was not implemented in this study, future works can include repeated runs or bootstrapping to better assess variability and generalizability.

Another future avenue is real-time hardware integration. By embedding Velostat-based respiration sensors into newborn clothes, an AI-driven wearable monitoring system could be developed, enabling continuous, real-time respiratory tracking without the need for intrusive electrodes or adhesive-based sensors15. This approach could significantly improve neonatal care by reducing discomfort, minimising sensor displacement issues, and lowering the risk of infection, addressing key challenges associated with conventional NICU respiratory monitoring technologies. Furthermore, optimising lightweight AI models for real-time processing is essential for NICU deployment, ensuring that deep learning solutions remain computationally efficient while maintaining high classification accuracy.

Building upon the limitations and challenges identified in this study, future research directions should prioritize: (1) validating ML models with real neonatal datasets to enhance generalization for clinical applications, (2) exploring e-textile-based applications, particularly Velostat-based breath rate sensors, which can be integrated into newborn monitoring garments for real-time tracking7, and (3) developing hybrid hardware-software models where synthetic data can be combined with real-world recordings to boost signal robustness and bridge the gap between theoretical modeling and clinical implementation.

Conclusion

This study presents a synthetic respiratory signal generation framework for neonatal health monitoring, addressing the limited availability of real neonatal respiratory datasets for deep learning and machine learning applications. The proposed dataset successfully replicates normal and pathological respiratory cycles, facilitating the training of AI-driven classification models for automatic respiratory distress detection. The CNN-BiLSTM model outperformed all architectures, achieving the highest accuracy of 96.16%. Statistical validation confirmed its significant superiority over CNN (p ¡ 0.0007, McNemar’s and Paired t-tests). Random Forest remained stable at 92.03%, making it a strong alternative for lower-complexity applications. Future work will focus on integrating real neonatal data and refining model generalisation through hybrid datasets. Random Forest classifiers, despite reaching 92.03% accuracy, were limited by their reliance on handcrafted features and struggled with hypoxia classification, reinforcing the superiority of deep learning models in bio-signal processing8.

Beyond software-based deep learning applications, this research also emphasises the potential for hardware-based respiratory monitoring using e-textile Velostat-based breath rate sensors. By integrating AI-driven models with flexible, wearable respiration sensors, a real-time, non-invasive monitoring system could be developed as an alternative to contact-based adhesive sensors in NICUs15. Such a system would enable continuous breathing tracking, enhance infant comfort, reduce motion artefacts, and minimise infection risks—critical improvements over conventional NICU monitoring technologies.

Abbreviations

- CNN

Convolutional Neural Network

- BiLSTM

Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- ML

Machine Learning

- DL

Deep Learning

- RF

Random Forest

- RR

Respiratory Rate

- CI

Confidence Interval

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- PPG

Photoplethysmography

- PSD

Power Spectral Density

- SpO2

Blood Oxygen Saturation

- HRV

Heart Rate Variability

Author contributions

A.J.D.K, B.C, S.K.S.A, S.A.A, V.B. and S.D wrote the main manuscript text, J.K and N.R prepared the figures S.D and V.B. reviewed entire manuscript and prepared the table and technical methodology sections. All the authors are contributed equally for the manuscript preparation, review and submission.

Funding

There was no financial support received from any organization for carrying out this work.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Viktoriia Bereznychenko, Email: vika.bereznichenko@i.ua.

Samiappan Dhanalakshmi, Email: dhanalas@srmist.edu.in.

References

- 1.Gee, A. H., Barbieri, R., Paydarfar, D. & Indic, P. Predicting bradycardia in preterm infants using point process analysis of heart rate. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng.64 (9), 2300–2308. 10.1109/TBME.2016.2632746 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweet, L. R. et al. Respiratory distress in the neonate: case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of maternal immunization safety data. Vaccine35, 6506–6517. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.01.046 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phiri, Y. V. et al. Neonatal intensive care admissions and exposure to satellite-derived air pollutants in the united States, 2018. Sci. Rep.15 (1), 420 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, W. et al. Design of an integrated sensor platform for vital sign monitoring of newborn infants at neonatal intensive care unit. J. Healthc. Eng.1 (4), 535–554. 10.1260/2040-2295.1.4.535 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park, C. & Lee, B. Real-time Estimation of respiratory rate from a photoplethys- mogram using an adaptive lattice Notch filter. Biomed. Eng. Online. 13 (170). 10.1186/1475-925X-13-170 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kanimozhi, M., Yamuna, I., Srimathi, B. & Kumaran, R. S. Development of Health Monitoring Vest Using Velostat (In: IFET College of Engineering, 2022).

- 7.Nizami, S., Bekele, A., Hozayen, M., Greenwood, K. & Harrold, J. Compar- Ing time and Frequency Domain Estimation of Neonatal Respiratory Rate Using pressure-sensitive Mats (Carleton University, 2022). 10.1109/TIPTEKNO52138.2021.9576205

- 8.Umeda, D. et al. Hypoxia drives the formation of lung micropapillary adenocarcinoma-like structure through hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Sci. Rep.14 (1), 31642 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cay, G. et al. An e-textile respiration sensing system for Nicu monitoring: design and valida- Tion. J. Signal. Process. Syst.94, 543–557. 10.1007/s11265-021-01669-9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupa, A. J. & Dhanalakshmi, S. Automatic Detection of Fetal QRS Complex using Time-Frequency Image Based Features and Deep Learning Architecture. In2022 3rd International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC) 778–782. (IEEE, 2022)

- 11.Krupa, A. J., Dhanalakshmi, S., Lai, K. W., Tan, Y. & Wu, X. An IoMT enabled deep learning framework for automatic detection of fetal QRS: A solution to remote prenatal care. J. King Saud University-Computer Inform. Sci.34 (9), 7200–7211 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kciuk, M., Kowalik, Z., Sciuto, G., Sl-awski, S. & Mastrostefano, S. Intelligent med- Ical velostat pressure sensor mat based on artificial neural network and arduino embedded system. Appl. Syst. Innov.6 (84). 10.3390/asi6050084 (2023).

- 13.Shukla, S. & Das, D. Iot based non-invasive vital signs monitoring in neona- tal intensive care unit (nicu). In: IEEE International Women in Engineering Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (WIECON-ECE) (2022). 10.1109/WIECON-ECE56128.2022.10061818

- 14.El Hadiri, A., Bahatti, L., El Magri, A. & Lajouad, R. Sleep stages detection based on analysis and optimisation of non-linear brain signal parameters. Results Eng.23, 102664 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanam, F. T. Z., Perera, A. G., Al-Naji, A., Gibson, K. & Chahl, J. Non-contact automatic vital signs monitoring of infants in a neonatal intensive care unit based on neural networks. J. Imaging. 7 (122). 10.3390/jimaging7080122 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Cay, G. et al. Neowear: an iot-connected e-textile wearable for neonatal medical monitoring. Pervasive Mob. Com- Puting. 86, 101679. 10.1016/j.pmcj.2022.101679 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Hernandez, U. & Assaf, T. Soft tactile sensor with multimodal data pro- cessing for texture recognition. IEEE Sens. Lett.10.1109/LSENS.2023.3300796 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ang, C. Y., Chiew, Y. S., Wang, X., Nor, M. B. & Chase, J. G. Stochasticity of the respiratory mechanics during mechanical ventilation treatment. Results Eng.19, 101257 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cay, G. et al. Solunumwear: A smart textile system for dynamic respiration monitoring across various postures. iScience27, 110223. 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110223 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sitaula, C. et al. Artificial intelligence-driven wearable technologies for neonatal cardiorespira- Tory monitoring: part 2: artificial intelligence. Pediatr. Res.93 (2), 426–436 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jang, W. et al. Artificial intelligence–driven respiratory distress syndrome prediction for very low birth weight infants: Korean multicenter prospective cohort study. J. Med. Internet. Res.25, e47612 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Jaba Deva Krupa, A. & Dhanalakshmi, S. An improved parallel sub-filter adaptive noise canceler for the extraction of fetal ECG. Biomedical Engineering/Biomedizinische Technik. 66 (5), 503–514 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manne, S. K. R., Zhu, S., Ostadabbas, S. & Wan, M. Automatic infant respiration estimation from video: A deep flow-based algorithm and a novel public benchmark. In International Workshop on Preterm, Perinatal and Paediatric Image Analysis. 111–120 (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023).

- 24.Gravina, M. et al. Deep learning in the ultrasound evaluation of neonatal respiratory status. In 2020 25th international conference on pattern recognition (ICPR). 10493–10499 (IEEE, 2021).

- 25.Grooby, E. et al. Prediction of neonatal respiratory distress in term babies at birth from digital stethoscope recorded chest sounds. In 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). 4996–4999 (IEEE, 2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.