Abstract

OBJECTIVE

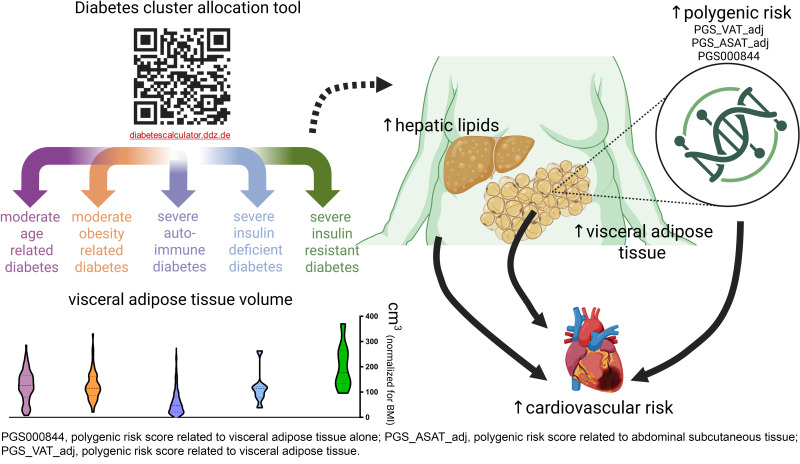

The severe insulin-resistant diabetes (SIRD) endotype is associated with metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease and higher cardiovascular risk. We investigated whether skeletal muscle or adipose tissue lipids are elevated in SIRD.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Participants (N = 420) of the German Diabetes Study (GDS) were assigned to diabetes clusters using a validated algorithm. 1H-magnetic resonance methods were used to quantify intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs), intrahepatic lipids (IHLs), and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) volumes.

RESULTS

Aside from elevated IHLs (P < 0.01), SIRD showed higher VAT and SAT than other endotypes after adjustment for BMI (all P < 0.05) but not for multiple comparisons. All endotypes featured comparable IMCLs. VAT volume and IHLs correlated with cardiovascular risk scores (Framingham r = 0.661 and 0.548, respectively, P < 0.05). Polygenic risk scores for VAT were associated with higher cardiovascular risk.

CONCLUSIONS

SIRD features higher IHLs and nominally higher VAT volume, which likely contribute to increased cardiovascular risk, highlighting implications for tailored prevention and treatment.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Dysfunctional adipose tissue favors lipotoxic insulin resistance, dysglycemia, and ultimately, diabetes (1). Although both subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) are established cardiometabolic risk factors (2), VAT is considered to exert stronger deleterious metabolic effects (3). Moreover, ectopic lipid accumulation in the liver leading to metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) increases the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (4,5).

Recent studies have indicated that diabetes comprises endotypes (clusters) with distinct clinical features and complication risks (6,7). Severe insulin-resistant diabetes (SIRD) carries a higher risk of MASLD (7,8), possibly modulated by genetic factors (9), suggesting also higher lipid deposition in skeletal muscle or adipose tissues. Consequently, the aim of this study was 1) to determine whether diabetes endotypes differ in volume and distribution of adipose tissue compartments and 2) to investigate possible relationships of adipose tissue compartments with CVD risk among diabetes endotypes.

Research Design and Methods

Participants

Humans with recent-onset diabetes (n = 281) or euglycemia (normal glucose tolerance [NGT]) (n = 139) were recruited from the prospective German Diabetes Study (GDS). The GDS was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (reference no. 4508), is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT01055093), and is performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (10). Euglycemia of the NGT control group was confirmed by a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test. Oral glucose-lowering medication was paused 3 days prior to all tests.

Participants with diabetes were categorized into endotypes based on a validated algorithm that included age, BMI, glycemia, HOMA2 of insulin resistance, and HOMA2 β-cell function (6,7). Positive GAD antibodies defined the severe autoimmune diabetes (SAID) endotype (7). The clustering tool is available online at https://diabetescalculator.ddz.de, allowing the assignment of participants to SAID, SIRD, severe insulin-deficient diabetes (SIDD), moderate obesity-related diabetes (MOD), or moderate age-related diabetes (MARD) (11).

Laboratory Analyses

Blood samples were analyzed in the center’s biomedical laboratory as previously described (10).

Metabolic Phenotyping

Modified Botnia clamps comprising an intravenous glucose tolerance test and a subsequent hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp were performed as previously described (10).

Genomics

Genotyping was performed using the Infinium Global Diversity Array with Polygenic Risk Score Content-8 version 1.0 (San Diego, CA), starting with 200 ng of genomic DNA. Polygenic risk scores (PGSs) related to VAT (PGS_VAT_adj) and abdominal SAT (PGS_ASAT_adj) (12), as well as VAT mass alone (PGS000844) (13), were computed from the weighted average of risk alleles, using effect sizes from publicly available summary statistics. Detailed genotyping is described in the Supplementary Material.

MRS and MRI

All MRS/MRI measurements were performed in a 3T whole-body magnetic resonance scanner (Achieva X-series, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands), as previously described (14). Single-voxel MRS was performed for quantification of intrahepatic lipids (IHLs) and intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs) in anterior tibial muscle. SAT and VAT volumes were quantified by whole-body MRI using T1-weighted fast spin-echo and postprocessing by a trained operator using SliceOmatic version 5.0 software (Tomovision, Montreal, Canada).

Cardiovascular Risk Assessment

The Framingham Risk Score for CVD, UK Prospective Diabetes Study risk score for nonfatal coronary heart disease (UKPDS CHD), and the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation 2 (SCORE2)-Diabetes were used to estimate cardiovascular risk (15) (Supplementary Material).

Statistical Analysis

P values <5% were considered to indicate statistically significant differences or correlations. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 4.0.1 (https://www.r-project.org). Correlation analyses were performed using the CORR procedure of SAS, and analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method and linear models with CVD risk score as the fixed effect and covariates VAT, SAT, IHLs, and IMCLs. Relative importance of each predictor was evaluated using the relaimpo package, with lmg metrics and bootstrapping applied to ensure robust results. These metrics were normalized to a sum of 100%, allowing for a comparison of each predictor’s contribution. Detailed statistical methods pertaining to cluster analyses and PGSs are described in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Study Cohort Characteristics

Anthropometric and clinical data of participants with NGT and those with recent-onset diabetes, stratified by cluster (7), are shown in Table 1. Nominally, Framingham CVD, SCORE2-Diabetes, and UKPDS CHD risk scores indicated the CVD risk to be highest for SIRD compared with other endotypes (Table 1). Differences in CVD scores between SIRD and MOD, SAID, SIDD, and NGT remained statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | NGT | SAID | SIDD | SIRD | MOD | MARD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | 139 | 115 | 7 | 8 | 69 | 82 |

| Age (years) | 44 ± 14 | 36 ± 11 | 40 ± 12 | 57 ± 5 | 44 ± 8 | 56 ± 7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 | 27 ± 3 | 33 ± 3 | 34 ± 5 | 26 ± 4 |

| Whole-body insulin sensitivity (mg/[kg · min]) | 11.1 ± 3.4 | 9.1 ± 3.6 | 5.6 ± 2.6 | 4.9 ± 2.1 | 5.6 ± 2.2 | 7.7 ± 2.8 |

| Insulin secretion (AUC of C-peptide in IVGTT) | 180 ± 73 | 31 ± 43 | 40 ± 30 | 230 ± 135 | 121 ± 79 | 93 ± 64 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 8.5 ± 0.9 | 6.7 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 6.3 ± 0.7 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 196 ± 39 | 180 ± 34 | 214 ± 32 | 202 ± 52 | 193 ± 51 | 193 ± 42 |

| Framingham CVD risk score (arbitrary units) | 8 ± 10 | 6 ± 7 | 18 ± 18 | 45 ± 17 | 16 ± 14 | 31 ± 19 |

| SCORE2-Diabetes (arbitrary units) | NA | NA | 11 ± 5 | 15 ± 4 | 5 ± 4 | 10 ± 4 |

| UKPDS CHD (%) | NA | 3 ± 3 | 12 ± 10 | 22 ± 13 | 7 ± 8 | 14 ± 11 |

Data are mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. AUC, area under the curve; IVGTT, intravenous glucose tolerance test; NA, not applicable.

Adipose Tissue Compartments

After adjusting for BMI and multiple comparisons, all diabetes endotypes but SAID and SIDD showed higher VAT than NGT. SAT was similar across NGT and diabetes endotypes. Mean IHLs ranged from 2 to 6% in all endotypes except SIRD, showing a significantly higher mean of 15%. SIRD presented with higher VAT than MOD, MARD, and SAID (6,089 ± 2,705 vs. 3,260 ± 2,310, 3,056 ± 1,963, 1,524 ± 1,401 cm3, respectively), even after accounting for BMI differences (all P < 0.05), but lost statistical significance upon adjustment for multiple comparisons. SAT was also higher in SIRD than MARD (27,879 ± 6,777 vs. 17,127 ± 6,218 cm3, P < 0.05), but not after adjustment for multiple comparisons. There were no differences in IMCLs among all endotypes.

Genetic Analyses

The PGS_VAT_adj and PGS_ASAT_adj for VAT and SAT, respectively, revealed higher scores in SIRD than in NGT and SAID (Fig. 1). However, VAT-related PGS000844 did not show statistically significant differences between SIRD and other clusters.

Figure 1.

Lipid content and adipose tissue volumes stratified by cluster. Violin plots showing minimum, maximum, median, and interquartile range. A: IHLs. B: IMCLs. C: VAT. D: SAT. E: PGS_VAT_adj. F: PGS_ASAT_adj. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.05 after adjustment for multiple comparisons. a.u., arbitrary units.

Correlation Analyses

Both SAT and VAT were associated with IHLs (r = 0.290 and 0.679, both P < 0.05) and IMCLs (r = 0.121 and 0.231, both P < 0.05) across the study population. VAT correlated with cardiovascular risk scores (Framingham CVD: r = 0.669, P < 0.05), whole-body insulin sensitivity (r = −0.485, P < 0.05) and β-cell function (r = 0.343, P < 0.05). Similarly, IHLs correlated with the Framingham CVD risk score (r = 0.573, P < 0.05). Within SIRD, higher VAT was associated with higher cardiovascular risk (r = 0.690, P = 0.05). The Framingham CVD risk score was also inversely associated with β-cell function (r = −0.821, P < 0.05) in SIRD.

Multivariate regression models addressing the relative roles of lipid compartments on CVD risk identified VAT as the strongest determinant with a 1-unit increase in VAT (cm3) raising the Framingham CVD risk score by 0.44 arbitrary units, while a 1-unit increase in IHLs (%) raised the Framingham risk score by 0.36 arbitrary units. Conversely, increases in SAT were associated with decreases in CVD risk, while changes in IMCLs did not affect CVD risk.

The multivariate regression model explained 44% of the variance in the Framingham CVD risk score, indicating a moderate level of explanatory power. Among the predictors, VAT emerged as the most poignant factor, contributing ∼58% to the model’s explanatory power according to relative importance metrics. IHLs accounted for 17% of the variance. In contrast, SAT and IMCLs had lower impacts, with contributions of <11% and <2%, respectively. PGS_VAT_adj, PGS_ASAT_adj, and PGS000844 correlated with the Framingham CVD (r = 0.43, 0.52, and −0.16, respectively, all P < 0.05), the UKPDS CHD (r = 0.46, 0.57, and −0.17, respectively, all P < 0.05), and SCORE2-Diabetes (r = 0.25, 0.33, and −0.18, respectively, all P < 0.05) risk scores (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Conclusions

This study shows that members of the SIRD endotype not only feature greater whole-body insulin resistance and IHLs but also a nominally higher VAT compartment. Additionally, VAT and IHLs were associated with increased cardiovascular risk across the spectrum of diabetes endotypes.

The risk for diabetes and CVD is increasing in parallel with progressing adiposity (1), particularly related to increased VAT (1). There is also evidence for a higher cardiovascular risk in the SIRD cluster in Swedish (6) and German (15) cohorts likely due to the presence of MASLD and dyslipidemia (16). This may result from release of proatherogenic lipids and proinflammatory mediators either from the steatotic liver or from the VAT compartment (1). Indeed, individuals with insulin resistance and MASLD feature local inflammation and abnormal mitochondrial capacity in VAT but not in SAT (17). Our findings thereby highlight that both MASLD and VAT may mutually contribute to increased CVD risk.

Several limitations affected the generalizability of the results. Aside from possible bias induced by the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the GDS cohort (10), restrictions by MRI decreased the sample size by excluding those with very high BMI. This led to a lower representation of MOD and SIRD in the current analysis and likely underestimates the results due to selection bias. IMCLs neither differed between endotypes nor affected CVD risk at diagnosis. In line with previous observations, IMCLs might not directly affect vascular risk at diagnosis but accelerate risk during the early course of type 2 diabetes (18).

Certain genetic variations appear to mediate CVD risk in the face of greater adiposity and ectopic lipid storage (12,13), which is supported by the endotype-independent association between CVD risk and PGS for VAT. Interestingly, the SIRD endotype exhibited an increased genetic risk for VAT, in line with observations from the imaging data. Combination of phenomic data with genomics (9) could help to further improve individual risk assessment and pave the way to precision diabetology (19). Targeting reduction of adipose tissue to decrease cardiovascular risk appears specifically important for people with SIRD (20). Collectively, these observations support the concept of targeted screening of persons at highest risk of CVD (i.e., the SIRD endotype) and intensified risk factor management in people with MASLD and type 2 diabetes.

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.29161247.

Article Information

The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Duality of Interest. O.-P.Z. reported receiving lecture fees from Sanofi and Chiesi. R.W. reported receiving lecture fees from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Eli Lilly and served on advisory boards for Akcea Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. M.R. reported receiving fees for lecturing and/or advisory board activities from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Echosens, Eli Lilly, Madrigal, MSD, Novo Nordisk, and Synlab and investigator-initiated studies from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. O.-P.Z. wrote the manuscript and researched data. Y.K. and V.S.-H. performed and analyzed the metabolic imaging data. P.B., C.B., and T.M. performed the statistical analyses. B.K. performed the genetic analyses. I.Y., D.M.M.C., T.K., N.T., M.S., K.B.B., R.W., and M.R. researched data, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. M.R. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 84th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, Orlando, FL, 21–24 June 2024, and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes 2024 Annual Meeting, Madrid, Spain, 9–13 September 2024.

Handling Editors. The journal editors responsible for overseeing the review of the manuscript were Elizabeth Selvin and Anna L. Gloyn.

Funding Statement

The German Diabetes Study was initiated and is financed by the German Diabetes Center (which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Culture and Science of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (to the German Center for Diabetes Research). Parts of the study are also supported by the Rising Star Award of the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes, the German Diabetes Association, the Schmutzler Stiftung, and the program Profilbildung 2020, an initiative of the Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of Northrhine Westphalia (grant PROFILNRW-2020-107-B).

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT01055093, clinicaltrials.gov

See accompanying article, p. 2000.

*A complete list of the GDS Group can be found in the supplementary material online.

Contributor Information

Michael Roden, Email: michael.roden@ddz.de.

GDS Group*:

Michael Roden, Hadi Al-Hasani, Bengt F. Belgardt, Gidon J. Bönhof, Gerd Geerling, Christian Herder, Andrea Icks, Karin Jandeleit-Dahm, Oliver Kuss, Eckhard Lammert, Sabrina Schlesinger, V. Schrauwen-Hinderling, Julia Szendroedi, Sandra Trenkamp, and Robert Wagner

Supporting information

References

- 1. Xourafa G, Korbmacher M, Roden M. Inter-organ crosstalk during development and progression of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2024;20:27–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bódis K, Jelenik T, Lundbom J, et al.; GDS Study Group . Expansion and impaired mitochondrial efficiency of deep subcutaneous adipose tissue in recent-onset type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:e1331–e1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2007;116:39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wong ND, Sattar N. Cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, assessment and prevention. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023;20:685–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Targher G, Corey KE, Byrne CD, Roden M. The complex link between NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus: mechanisms and treatments. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18:599–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahlqvist E, Storm P, Käräjämäki A, et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: a data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zaharia OP, Strassburger K, Strom A, et al.; German Diabetes Study Group . Risk of diabetes-associated diseases in subgroups of patients with recent-onset diabetes: a 5-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:684–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. European Association for the Study of Liver (EASL); European Association for the study of Diabetes (EASD) ; European Association for the Study of Obesity. EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol 2024;82:492–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zaharia OP, Strassburger K, Knebel B, et al.; GDS Group . Role of patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 gene for hepatic lipid content and insulin resistance in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2020;43:2161–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Szendroedi J, Saxena A, Weber KS, et al.; German Diabetes Study Group . Cohort profile: the German Diabetes Study (GDS). Cardiovasc Diabetol 2016;15:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mori T, Prystupa K, Straßburger K, et al. A web-based application for diabetes subtyping: the DDZ Diabetes-Cluster-Tool. Acta Diabetol 2025;62:281–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agrawal S, Wang M, Klarqvist MDR, et al. Inherited basis of visceral, abdominal subcutaneous and gluteofemoral fat depots. Nat Commun 2022;13:3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mansour Aly D, Dwivedi OP, Prasad RB, et al.; Regeneron Genetics Center . Genome-wide association analyses highlight etiological differences underlying newly defined subtypes of diabetes. Nat Genet 2021;53:1534–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kupriyanova Y, Zaharia OP, Bobrov P, et al.; GDS Group . Early changes in hepatic energy metabolism and lipid content in recent-onset type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. J Hepatol 2021;74:1028–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saatmann N, Zaharia O-P, Strassburger K, et al. Physical fitness and cardiovascular risk factors in novel diabetes subgroups. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022;107:1127–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pilz S, Scharnagl H, Tiran B, et al. Free fatty acids are independently associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in subjects with coronary artery disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:2542–2547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pafili K, Kahl S, Mastrototaro L, et al. Mitochondrial respiration is decreased in visceral but not subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese individuals with fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2022;77:1504–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schön M, Zaharia OP, Strassburger K, et al.; GDS Group . Intramyocellular triglyceride content during the early course of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2023;72:1483–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Misra S, Wagner R, Ozkan B, et al.; ADA/EASD PMDI . Precision subclassification of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Commun Med (Lond) 2023;3:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation 2022;146:1882–1894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.