Abstract

Background

Blood-based biomarkers (BBBMs) could significantly facilitate the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and non-AD dementia by providing less invasive alternatives to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging.

Objective

This study investigated how well the BBBMs—amyloid-β (Aβ) 1-42/1-40 ratio, phosphorylated tau181 (pTau181), apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and neurofilament light chain (NfL)—reflect thorough clinical work-up validated by PET and CSF biomarkers in participants with AD (n = 27), Aβ-negative CBS (n = 26), and agematched healthy controls (HC) (n = 17).

Methods

Factor and correlation explored biomarker associations. Bayesian regression, backward selection regression, and ROC curve analysis were applied to identify optimal biomarker combinations and diagnostic cut-offs.

Results

In AD cases, pTau181 and ApoE4 levels were elevated, and the Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio was reduced. ROC analysis showed high accuracy for pTau181, ApoE4 and Aβ1-42/1-40 in discriminating AD from HC, with a combination significantly improving performance. However, limited fold change, and high variability reduced the diagnostic applicability of Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio. Elevated NfL levels were the most reliable biomarker for CBS-Aβ(–) cases. GFAP showed limited discriminatory power due to overlapping levels, suggesting that it may not serve as a disease-specific biomarker but may be indicative of general neurodegeneration.

Conclusions

This study highlights the diagnostic utility of pTau181, ApoE4 and the Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio for AD and NfL in the CBS-Aβ(–) cases and emphasizes the added value of combined biomarker models for group differentiation. Prospective studies will help validate these findings and refine clinical thresholds.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00406-025-02013-z.

Keywords: Non-Alzheimer's disease dementia; beta, Beta-amyloid 1-40 (Aβ1-40), Beta-amyloid 1-42 (Aβ1-42), Phosphorylated tau (pTau), Neurofilament light chain (NfL), Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), Apolipoprotein E (ApoE4)

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers and neuroimaging, particularly targeting amyloid and tau pathology, have advanced the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease (AD), particularly towards its early stages. However, these methods remain invasive, costly and largely inaccessible, highlighting the need for easy-to-use alternatives [1]. Blood-based biomarkers (BBBMs), including the Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio and phosphorylated tau181 (pTau181), have demonstrated significant diagnostic value in AD as indicators of underlying tau and amyloid pathology [2–6]. However, these biomarkers primarily target AD pathology and are less informative for other neurodegenerative conditions, such as corticobasal syndrome (CBS). Despite advances in AD diagnostics, there remains a significant unmet need for biomarkers that can reliably differentiate non-AD dementias and healthy controls from AD in routine clinical practice.

Indeed, CBS poses a unique diagnostic challenge, as it can mimic AD through overlapping symptoms like cognitive decline and apraxia [7]. CBS can arise from several non-AD pathologies, including corticobasal degeneration (CBD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), or TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) proteinopathy, or can occur as a coexisting pathology [7–10]. Mixed pathologies, such as coexisting AD and non-AD pathology, are known to have negative synergistic effects on disease progression and prognosis, underscoring the necessity of biomarkers to disentangle these complexities and refine differential diagnosis [11, 12].

To address this gap, we investigated biomarkers beyond amyloid and tau that reflect complementary aspects of neurodegeneration: apolipoprotein E (ApoE4), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and neurofilament light chain (NfL). ApoE4, the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, provides insights into genetic risk, aiding in the identification of individuals with elevated or reduced risk and complementing other biomarkers in stratifying amyloid pathology [13]. GFAP, a marker of astroglial activation, is valuable for identifying neuroinflammatory processes, while NfL is highly sensitive to neurodegeneration and shows promise in distinguishing AD from non-AD dementias like frontotemporal dementia and CBS [14–16].

This study aims to improve the diagnosis of CBS and other non-AD dementias using BBBMs, with a particular focus on discriminating between AD, CBS and healthy controls. A better understanding of these biomarkers will be a step towards more personalized and effective management of dementia, improving patient care and access to healthcare.

Methods and materials

Study design and participants

This study was designed as a prospective cohort study to evaluate the diagnostic value of Aβ1-42/1-40, pTau181, ApoE4, GFAP, and NfL. This study was conducted within the framework of the “Activity of Cerebral Networks, Amyloid, and Microglia Activity in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease” (ActiGliA) study.

The study, initiated in 2017, was approved by the local ethics committee of LMU Munich (project numbers 17-755 and 17-569) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06224920). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Recruitment took place between May 2018 and November 2021 through the outpatient clinics of the Departments of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy and Neurology (both at LMU Hospital Munich). The ability to give consent was systematically assessed [17]. Under the responsibility of specialists in neurology and/or psychiatry, participants underwent a comprehensive clinical evaluation, including examination of CSF, standardized neurological and psychiatric assessments, neuropsychological testing and brain imaging.

Participants with AD dementia and MCI due to AD

Participants with probable AD dementia and MCI due to AD were categorized to capture the spectrum of AD progression. Both groups, along with healthy controls (HC), underwent comprehensive cognitive testing, including CERAD (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease), CDR (Clinical Dementia Rating), MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination), ADAS-Cog (Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale), and FCRST (Free and Cued Recall Selective Reminding Test). Probable AD dementia was defined by cognitive decline affecting daily living, confirmed by standardized tests and structured interviews with informants [18, 19]. MCI due to AD was identified by objective cognitive decline and preserved independence in daily living [19]. MMSE was used to estimate global cognition across all groups, with detailed results available upon request [20].

Participants with corticobasal syndrome

Participants with CBS were diagnosed based on established criteria for presentations such as asymmetric parkinsonism, frontal-behavioral-spatial syndrome, and apraxia [7, 9, 21, 22]. CBS cases were classified as CBS-Aβ( +) or CBS-Aβ(–) based on the results of CSF Aβ1-42/1-40 ratios and/or amyloid PET findings [7, 8].

Healthy controls (HC)

Healthy age-matched controls (HCs) were defined by the absence of AD pathology (normal amyloid PET or CSF Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio), structural brain abnormalities, and normal neurological, psychiatric, and neuropsychological evaluations, with scores within one standard deviation below the mean [23].

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Participants were scanned with [18F]flutemetamol, an FDA and EMA approved amyloid PET tracer, at the Department of Nuclear Medicine, LMU Hospital [24]. Briefly, study participants were scanned on a Biograph 64 or a Siemens mCT PET/C scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), after a baseline CT scan, dynamic emission imaging was performed 0–60 min after injection of the radionuclide. PET data were reconstructed by recombining the baseline and the dynamic emission recordings. Standardized uptake value ratios (SUVr) of all 246 volumes of interest of the brainnetome atlas were extracted and used for data analysis.

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid

Immunoassays from Fujirebio® (Gent, Belgium) (phosphoTau 181), IBL International (Hamburg, Germany) (total tau, Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42) were used and their values were interpreted as indicative of AD according to the values established by the LMU laboratory: pTau181 > 61 pg/ml, Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio < 0.055 and total tau > 445 pg/ml [25].

Definition of amyloid positivity

Amyloid positivity was defined either as a CSF Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio below 0.055 according to LMU Hospital laboratory procedures or by assessment of [18F]flutemetamol amyloid PET tracer retention [26, 27].

Analysis of BBBM

Blood was collected and processed according to the standard procedures of the Munich Mental Health Biobank [28]. Samples from CBS-Aβ(–) and CBS-Aβ( +) cases underwent one freeze–thaw cycle prior to this analysis. The analysis of BBBM (Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, pTau181, ApoE4, NfL, GFAP) was performed using a Cobas® e601/e411 module/analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) based on the Elecsys electrochemiluminescence immunoassay technology (all Roche Diagnostics Internation Ltd, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The Elecsys assays used in this study are part of the NeuroToolKit, a panel of exploratory robust prototype assays (Roche Diagnostics Internation Ltd, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The analysis was performed in a single batch using a quantitative sandwich assay with a determination time of 18 min. Analyte-specific antibodies labelled with biotin or a ruthenium complex bind to streptavidin-coated microparticles, which are magnetically captured on an electrode. After washing with ProCell M solution, a voltage is applied to induce chemiluminescent emission, which is measured by a photomultiplier.

APOE4 ε4 genotyping

APOE4ε genotypes were determined using TaqMan SNP assays after automated DNA isolation from EDTA blood.

Statistical analyses

Extreme outliers were removed using the IQR method and data were z standardized. Due to non-normal distributions, non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis and pairwise Mann–Whitney U tests) were used, with adjustments for age, sex and FDR correction for multiple testing. Small sample size groups were excluded. Spearman and partial Spearman correlations (adjusted for age and sex) with FDR correction assessed clinical-biomarker relationships. Factor analysis with varimax rotation identified latent factors, and Bayesian regression addressed multicollinearity (via VIF) and selected significant biomarkers. ROC analysis (AUC, sensitivity, specificity, Youden index) determined optimal cut-offs, with cross-validation ensuring reliability. Combined models optimized AUC and biomarker contributions, quantified using posterior distributions and credible intervals. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used. All statistical tests and graphs were generated using R Studio version 2024 [29].

Results

Recruitment of participants

The final analysis included n = 77 participants with the following CSF- and amyloid-PET based clinical diagnoses (Fig. 1):

- Alzheimer´s disease (AD) (n = 26)

-

omild cognitive impairment due to AD (AD-MCI) (n = 14)

-

omild dementia due to AD (n = 12)

-

o

Aβ-positive corticobasal syndrome (CBS-Aβ( +)) (n = 8)

Aβ-negative corticobasal syndrome (CBS-Aβ(–)) (n = 26)

Healthy controls (HC) (n = 17)

Fig. 1.

Recruitment and Group Classification. Of 138 participants, n = 31 withdrew their consent, n = 21 were excluded from this analysis due to missing data, n = 4 due to a diagnosis of small vessel disease (SVD), n = 4 due to indeterminate disease. In n = 2 cases amyloid PET was available but not CSF, in n = 5 cases CSF was available but not amyloid PET. One amyloid PET-negative case had a CSF amyloid ratio below 0.055, presented clinically with CBS and was classified as a CBS-Aβ( +) case. N = 78 participants underwent magnet resonance imaging. 76% were right-handed, 9% left-handed, 5% indifferent and 10% missing data

Participants with AD were predominantly in the early stages of the disease, as reflected by the subdivision into mild cognitive impairment (AD-MCI) and mild dementia, and the relatively preserved mean MMSE score (Table 1). PET imaging confirmed amyloid positivity in 24/26 AD/MCI cases, while 25/26 CBS-Aβ(–) and 17/17 HC were amyloid PET negative, supporting the classification of these participants (Fig. 1). Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, this study faced a high drop-out rate, which significantly limited the availability of follow-up data. Of the 78 participants, only 43 completed the 18-month follow-up, making it impossible to reliably analyze changes in BBBM levels over time.

Table 1.

Demographic data (continuous variables) including age, duration of illness, Mini Mental Examination Status (MMSE) and education across diagnostic groups

| Demographics—Continuous Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | Mean | Median | SD | Pct25 | Pct75 | Shapiro (p value) | Kruskal (p value) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| AD | 26 | 70.05 | 71.00 | 6.90 | 66.50 | 74.00 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 74.89 | 75.00 | 9.10 | 72.00 | 83.00 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 26 | 71.23 | 72.00 | 6.71 | 67.00 | 76.00 | ||

| HC | 17 | 70.50 | 70.50 | 6.13 | 69.00 | 73.50 | ||

| All cases | 77 | 71.93 | 72.00 | 7.08 | 67.00 | 76.50 | 0.065 | 0.329 |

| Duration (months) | ||||||||

| AD | 26 | 37.95 | 28.00 | 23.89 | 17.50 | 56.50 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 33.89 | 25.00 | 20.60 | 17.00 | 51.00 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 26 | 30.12 | 25.00 | 17.39 | 17.25 | 36.00 | ||

| HC | 17 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| All cases | 77 | 32.90 | 27.50 | 19.42 | 17.00 | 45.00 | 0.000 | 0.556 |

| Education (years) | ||||||||

| AD | 26 | 15.11 | 14.00 | 3.40 | 13.00 | 17.00 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 12.89 | 12.00 | 3.26 | 11.00 | 14.00 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 26 | 13.15 | 13.00 | 2.75 | 11.00 | 14.00 | ||

| HC | 17 | 14.90 | 14.00 | 3.21 | 12.25 | 17.50 | ||

| All cases | 77 | 14.00 | 13.00 | 3.37 | 11.50 | 17.00 | 0.004 | 0.124 |

| MMSE (0 to 30 points) | ||||||||

| AD | 26 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 3.54 | 22.00 | 27.50 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 19.56 | 22.00 | 8.63 | 14.00 | 26.00 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 25 | 24.48 | 26.00 | 5.36 | 21.00 | 28.00 | ||

| HC | 17 | 29.35 | 30.00 | 1.11 | 29.00 | 30.00 | ||

| All cases | 78 | 25.49 | 27.00 | 4.94 | 24.00 | 29.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Participant characteristics and clinical data

Age, disease duration and education were not significantly different between the AD, CBS-Aβ(–) and HC groups, as indicated by the Kruskal–Wallis test (p > 0.05 each). Participants were generally in their early 70 s, with mean age ranging from 70.0 years (AD) to 74.9 years (CBS-Aβ( +)). Disease duration was longest in the AD group (mean = 37.9 months) and shortest in the CBS-Aβ(–) group (mean = 30.1 months). Educational attainment was relatively high in all groups, with a mean of 13.2 years (CBS-Aβ(–)) to 15.1 years (AD). However, MMSE scores were significantly higher in the HC group than in the AD and CBS-Aβ(–) groups (p < 0.001), reflecting preserved cognitive function in the healthy cohort (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Post-hoc analysis for demographic differences between groups using Mann–Whitney tests

| Post-hoc Analysis (Mann–Whitney-Test) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Duration | Education | MMSE | |

| AD vs. CBS-Aβ(–) | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 |

| AD vs. HC | p > 0.05 | p = 0.001 | p > 0.05 | p = 0.004 |

| CBS-Aβ(–) vs. HC | p > 0.05 | p = 0.001 | p > 0.05 | p = 0.004 |

| Ordinal variables (pairwise Fisher´s-exact-Test) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Amyloid PET | ApoEε4 carrier status | |

| AD vs. CBS-Aβ(–) | p > 0.05 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

| AD vs. HC | p > 0.05 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

| CBS-Aβ(–) vs. HC | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 |

FDR-corrected, CBS-Aβ(+) excluded by minimum size filtering

Categorial variables

Significant differences were observed in amyloid PET status (p = 0.001) and ApoEε4 carrier status (p < 0.001), whereas the sex distribution was balanced between groups with no significant differences (p > 0.05). Pairwise comparisons showed that AD was significantly different from CBS-Aβ(–) and HC in both amyloid PET status and ApoEε4 carrier status (p = 0.001 for each comparison) with the AD group largely consisting of ApoEε4 carriers. No significant differences were found between CBS-Aβ(–) and HC in either parameter (p > 0.05) (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Demographic data (categorical variables) including sex, amyloid PET results, and ApoEε4 carrier status across groups

| Demographics—Categorial Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Amyloid PET | ApoEε4 carrier status | ||||||

| Female | Male | Positive | Negative | Non-carrier | Hemizygous | Homozygous | ||

| AD | 26 | 17 | 10 | 24 | 0 | 6 | 15 | 6 |

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 26 | 15 | 11 | 0 | 25 | 15 | 4 | 4 |

| HC | 17 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 17 | 14 | 3 | 0 |

| all cases | 77 | 43 | 34 | 31 | 43 | 40 | 24 | 12 |

| Overall Fisher´s exact test | ||||||||

| p > 0.05 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.000 | ||||||

p values FDR-corrected for multiple testing

Table 4.

Post-hoc analysis for categorical demographic variables using Fisher’s exact test

| Post-Hoc Analysis (pairwise Fisher´s-exact-Test) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Amyloid PET | ApoEε4 carrier status | |

| AD vs. CBS-Aβ(–) | p > 0.05 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

| AD vs. HC | p > 0.05 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

| CBS-Aβ(–) vs. HC | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 |

FDR-corrected, CBS-Aβ( +) excluded by minimum size filtering

CBS-Aβ( +) group

The CBS-Aβ( +) group had a small sample size (n = 8), which limited the ability to perform statistical analyses. However, descriptive data suggest that participants in this group had a mean age of 74.9 years and a mean disease duration of 33.9 months, both slightly higher than in the other groups. Educational attainment in this group was slightly lower (mean = 12.9 years) than in the AD group (mean = 15.1 years), but comparable to the CBS-Aβ(–) group. MMSE scores (mean = 19.6 p.) indicated significant cognitive impairment in comparison to the CBS-Aβ(–) group (mean = 24.4 p.) (Tables 1 and 2). Amyloid PET positivity in the CBS-Aβ( +) group was observed in seven out of eight cases, with no clear pattern of ApoEε4 carrier status as the group included both carriers and non-carriers. Due to the small sample size, these findings should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the present approach cannot distinguish whether the CBS-Aβ( +) group represents cases of corticobasal syndrome with AD co-pathology or a variant of AD with a corticobasal syndrome phenotype.

Blood-based biomarkers

Mean levels of pTau181 were highest in the AD group (1.333 pg/ml) and the CBS-Aβ( +) group (1.222 pg/ml), with significantly lower levels observed in the CBS-Aβ(–) and HC groups (p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis) (Table 5). The post-hoc analysis revealed highly significant differences in pTau181 levels between AD and CBS-Aβ(–) (p < 0.001) as well as AD and HC (p = 0.000), with a moderate significance observed between CBS-Aβ(–) and HC (p = 0.004) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Blood-based biomarker levels for pTau181, Aβ1-42/1-40, ApoE4, GFAP, and NFL across groups (FDR-adjusted p-values)

| BBBM (p values corrected for multiple testing) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | Mean | Median | SD | Pct25 | Pct75 | Shapiro (p value) | Kruskal (p value) |

| pTau181 (pg/ml) | ||||||||

| AD | 25 | 1.333 | 1.250 | 0.604 | 0.842 | 1.480 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 1.222 | 1.210 | 0.465 | 0.891 | 1.605 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 21 | 0.715 | 0.728 | 0.148 | 0.627 | 0.823 | ||

| HC | 17 | 0.735 | 0.678 | 0.254 | 0.592 | 0.807 | ||

| All cases | 71 | 1.017 | 0.860 | 0.526 | 0.689 | 1.190 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio | ||||||||

| AD | 25 | 0.118 | 0.117 | 0.007 | 0.113 | 0.122 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 0.112 | 0.111 | 0.007 | 0.109 | 0.116 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 21 | 0.129 | 0.132 | 0.013 | 0.127 | 0.135 | ||

| HC | 17 | 0.135 | 0.133 | 0.019 | 0.129 | 0.141 | ||

| All cases | 71 | 0.124 | 0.123 | 0.016 | 0.114 | 0.133 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ApoE4 (UG/ml) | ||||||||

| AD | 25 | 9.920 | 9.780 | 7.759 | 7.330 | 11.620 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 2.530 | 0.000 | 3.503 | 0.000 | 6.348 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 21 | 2.342 | 0.000 | 5.145 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| HC | 17 | 1.578 | 0.000 | 3.525 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| All cases | 71 | 4.006 | 0.000 | 7.038 | 0.000 | 7.263 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| GFAP (ng/ml) | ||||||||

| AD | 25 | 0.147 | 0.134 | 0.066 | 0.099 | 0.189 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 0.146 | 0.165 | 0.053 | 0.139 | 0.179 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 21 | 0.105 | 0.099 | 0.049 | 0.071 | 0.143 | ||

| HC | 17 | 0.092 | 0.067 | 0.068 | 0.060 | 0.089 | ||

| All cases | 71 | 0.124 | 0.114 | 0.069 | 0.069 | 0.161 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| NfL (pg/ml) | ||||||||

| AD | 25 | 2.549 | 2.540 | 0.884 | 1.920 | 3.160 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 3.598 | 3.345 | 1.197 | 2.685 | 4.685 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 21 | 4.867 | 4.570 | 2.790 | 2.580 | 5.770 | ||

| HC | 17 | 2.069 | 1.900 | 0.899 | 1.390 | 2.620 | ||

| All cases | 71 | 3.457 | 2.720 | 2.387 | 1.930 | 4.080 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

Table 6.

Post-hoc analysis of blood-based biomarker differences between groups using Mann–Whitney tests

| Post-hoc Analysis (Mann–Whitney-Test) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pTau181 (pg/ml) | Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio | ApoE (UG/ml) | GFAP (ng/ml) | NfL (pg/ml) | |

| AD vs. CBS-Aβ(–) | p = 0.000 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.003 | p > 0.05 | p = 0.002 |

| AD vs. HC | p = 0.000 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.003 | p > 0.05 |

| CBS-Aβ(–) vs. HC | p = 0.004 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p = 0.001 |

Adjusted for age and sex, FDR-corrected, CBS-Aβ( +) excluded by minimum size filtering

Similarly, the Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio was lowest in the AD (0.118) and the CBS-Aβ( +) groups (0.112), reflecting pathological changes typical of AD. In contrast, higher amyloid ratios were observed in the HC and CBS-Aβ(–) groups (0.135 and 0.129, respectively), with significant group differences detected (p = 0.000). For the Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio, highly significant differences were found between AD and CBS-Aβ(–) (p = 0.002) and AD and HC (p = 0.002), whereas no significant differences were observed between CBS-Aβ(–) and HC (p > 0.05).

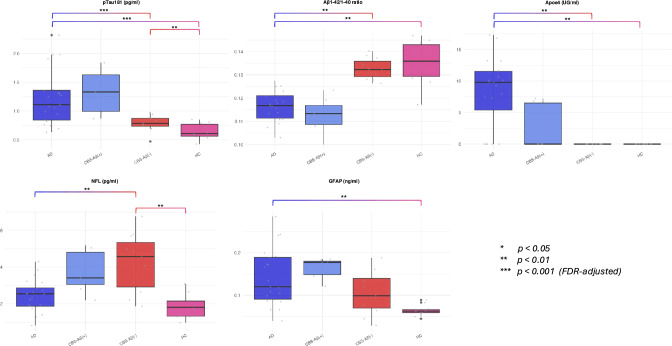

ApoE4 levels were highest in the AD group (9.920 UG/ml) and significantly lower in the HC group (1.578 UG/ml, p < 0.001). Intermediate levels were observed in the CBS-Aβ(–) group (2.342 UG/ml), while descriptive data for CBS-Aβ( +) indicated lower ApoE4 levels (2.530 UG/ml) like those of CBS-Aβ(–). In terms of ApoE4 levels, significant differences were detected between AD and CBS-Aβ(–) (p = 0.003) and AD and HC (p = 0.002), but CBS-Aβ(–) and HC showed no significant differences (p > 0.05). However, as shown in Table 3, a markedly higher proportion of ApoEε4 carriers was found in the AD group compared to CBS-Aβ( +) and CBS-Aβ(–), where the number of ApoEε4 carriers was notably lower. In fact, there were no ApoE4 carriers in the HC group. This suggests that rather than interpreting ApoE4 as a continuous biomarker, a dichotomous classification (ApoEε4 carrier vs. non-carrier) may be more appropriate for understanding its role in disease risk and biomarker distribution. The boxplot in Fig. 2 further illustrates these differences, emphasizing the categorical nature of ApoEε4 status.

Fig. 2.

Blood-based Biomarkers—Raw Data and Group Differences. Blood-based biomarkers showing raw data and group differences for pTau181, Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio, ApoE4, NFL, and GFAP. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (FDR-adjusted)

GFAP levels were highest in the AD and CBS-Aβ( +) groups (0.147 and 0.146 ng/ml, respectively) and lowest in the HC group (0.092 ng/ml), while intermediate GFAP levels were observed in the CBS-Aβ(–) group (0.105 ng/ml). GFAP levels showed no significant differences between AD and CBS-Aβ(–) (p > 0.05) or CBS-Aβ(–) and HC (p > 0.05), but a significant result was observed when comparing AD and HC (p = 0.003).

Finally, NfL levels were highest in the CBS-Aβ(–) group (4.867 pg/ml) and lowest in the HC group (2.069 pg/ml), with significant group differences observed (p < 0.002). Descriptive data for the CBS-Aβ( +) group showed intermediate NfL levels (3.598 pg/ml). Finally, NfL levels exhibited highly significant differences between AD and CBS-Aβ(–) (p = 0.002) as well as CBS-Aβ(–) and HC (p = 0.001), while no significant differences were observed between AD and HC (p > 0.05).

These results highlight distinct biomarker profiles among the AD, CBS-Aβ(–) and HC groups, while the CBS-Aβ( +) group shows a biomarker pattern like AD cases, although statistical analysis was precluded by limited sample size (Fig. 2 and Tables 5 + 6).

Cerebrospinal fluid markers

It is worth acknowledging that compared to their CSF counterpart, plasma amyloid ratios showed narrow interquartile ranges (e.g. AD 0.113–0.122, HC 0.129–0.141), small standard deviations (e.g. AD 0.007, HC 0.019) and substantial overlap in IQRs, e.g. between HC and CBS-Aβ(–) (0.127–0.135), which may limit their diagnostic utility by reducing the ability to clearly differentiate between groups. In contrast, CSF biomarkers showed wider interquartile ranges (e.g. AD 0.029–0.043, HC 0.068–0.084) with less overlap between groups, allowing clearer differentiation, especially between AD and HC.

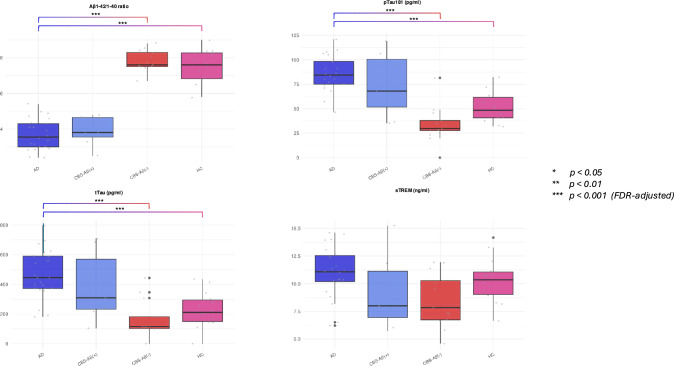

When comparing groups, the data for CSF biomarkers (Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio, pTau181, tTau and sTREM2) showed significant differences between groups for most biomarkers except sTREM2 (p > 0.05).

The CSF Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio was significantly lower in the AD and CBS-Aβ( +) groups (mean 0.036 and 0.040, respectively) compared to the HC and CBS-Aβ(–) groups (0.078 and 0.080, respectively; p < 0.001). For pTau181 levels, the AD group revealed the highest concentrations (mean 87.268 pg/ml), followed by the CBS-Aβ( +) group (70.116 pg/ml). CBS-Aβ(–) and HC had significantly lower levels (49.311 and 49.469 pg/ml, respectively; p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed that AD was significantly different from both HC and CBS-Aβ(–), while descriptive data for CBS-Aβ( +) indicated biomarker levels like those of AD. This supports the hypothesis of a shared pathology between AD and CBS-Aβ( +).

Similarly, tTau levels were elevated in AD (490.913 pg/ml) and CBS-Aβ( +) (362.868 pg/ml) compared to HC and CBS-Aβ(–) (223.588 and 261.885 pg/ml, respectively; p < 0.001). However, no obvious differences in tTau were observed between CBS-Aβ( +) and CBS-Aβ(–), suggesting some overlap in tau pathology within CBS subtypes. Due to the limited sample size, the CBS-Aβ( +) group was excluded from statistical comparisons according to the minimum group size filtering approach.

In contrast, sTREM2 levels were not significantly different between groups (p > 0,05), with similar levels observed in AD (11.305 ng/ml), CBS-Aβ( +) (9.316 ng/ml), CBS-Aβ(–) (9.930 ng/ml) and HC (10.477 ng/ml). These results suggest that sTREM2 had no discriminatory value in distinguishing between these disease groups (Fig. 3 and Tables 7 and 8).

Fig. 3.

CSF Markers—Raw Data and Group Differences. CSF markers illustrating raw data and group differences for Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio, pTau181, tTau, and sTREM. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (FDR-adjusted)

Table 7.

CSF biomarker levels (pTau181, Aβ1-42/1-40, tTau, sTREM2) across diagnostic groups with FDR-adjusted p-values.”

| CSF markers baseline (p-values corrected for multiple testing) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | Mean | Median | SD | Pct25 | Pct75 | Shapiro (p value) | Kruskal (p value) |

| pTau 181 (pg/ml) | ||||||||

| AD | 26 | 87.268 | 84.375 | 19.759 | 75.030 | 98.238 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 70.116 | 67.365 | 33.587 | 36.228 | 97.510 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 26 | 49.311 | 36.655 | 39.707 | 28.705 | 50.818 | ||

| HC | 17 | 49.469 | 50.190 | 19.380 | 40.650 | 58.780 | ||

| All cases | 77 | 64.258 | 58.780 | 33.300 | 37.670 | 82.140 | 0.004 | 0.000 |

| Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio | ||||||||

| AD | 26 | 0.036 | 0.033 | 0.009 | 0.029 | 0.043 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 0.040 | 0.040 | 0.008 | 0.037 | 0.046 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 26 | 0.080 | 0.077 | 0.012 | 0.074 | 0.085 | ||

| HC | 17 | 0.076 | 0.077 | 0.010 | 0.068 | 0.084 | ||

| All cases | 77 | 0.060 | 0.066 | 0.023 | 0.038 | 0.079 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| tTau (pg/ml) | ||||||||

| AD | 26 | 490.913 | 445.960 | 192.764 | 372.125 | 603.080 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 8 | 362.868 | 279.135 | 230.730 | 206.253 | 512.528 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 26 | 261.885 | 172.755 | 207.780 | 116.730 | 329.505 | ||

| HC | 17 | 223.588 | 221.970 | 125.145 | 146.320 | 300.690 | ||

| All cases | 77 | 344.766 | 315.485 | 218.064 | 175.955 | 445.653 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| sTREM2 (ng/ml) | ||||||||

| AD | 26 | 11.305 | 11.075 | 3.857 | 9.510 | 12.950 | ||

| CBS-Aβ( +) | 7 | 9.316 | 8.000 | 3.410 | 6.955 | 11.135 | ||

| CBS-Aβ(–) | 26 | 9.930 | 9.885 | 3.126 | 7.360 | 11.910 | ||

| HC | 17 | 10.477 | 10.355 | 3.079 | 8.775 | 11.365 | ||

| All cases | 77 | 10.743 | 10.455 | 3.544 | 8.178 | 12.493 | 0.181 | 0.374 |

Table 8.

Post-hoc analysis for CSF biomarkers between groups using Mann–Whitney tests

| Post-hoc Analysis (Mann–Whitney-Test) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio | pTau181 (pg/ml) | tTau (pg/ml) | sTREM (ng/ml) | |

| AD vs. CBS-Aβ(–) | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p > 0.05 |

| AD vs. HC | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p > 0.05 |

| CBS-Aβ(–) vs. HC | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 | p > 0.05 |

Adjusted for age and sex, FDR-corrected, CBS-Aβ( +) excluded by minimum size filtering

Factor analysis

Two main components were identified by factor analysis of the BBBM, explaining a total of 60.966% of the variance, an excellent result for factor analysis. The communalities for pTau181 (0.676) and NfL (0.743) suggested that these variables were well explained by the model, whereas the Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio (0.286) had a weaker representation. Component 1 was strongly associated with pTau181 (0.822) and GFAP (0.770), suggesting that these variables contribute most to this factor, possibly representing a neurodegenerative and inflammatory process. Component 2 was strongly associated with ApoE4 (– 0.703) and NfL (0.817), indicating that it may capture another biological mechanism, such as axonal degeneration or lipid metabolism. The Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio had moderate loadings on both components (– 0.491 and 0.213), meaning that it was not strongly associated with either component, but still had relevance.

Factor analysis of the CSF biomarkers revealed that two main components explained 85.2% of the variance in the data, indicating that these markers provide a robust and highly structured data set for differentiation. High communalities for CSF pTau181 (0.861) and CSF Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio (0.748) suggested that these markers explained a substantial proportion of the variance and were critical to the data structure. Component 1 was associated with pTau181 CSF (0.860), tTau CSF (0.850) and sTREM2 (0.953), reflecting their contribution to neurodegenerative and inflammatory processes. Although the absolute levels of sTREM2 may not be significantly different between groups, the high commonalities indicate that it is well aligned with other biomarkers involved in inflammation (e.g. tTau or pTau181), contributing to the latent neurodegenerative factor. Component 2 was predominantly characterized by the Aβ1-42/1-40 CSF ratio (– 0.855), consistent with its relevance in amyloid pathology. The high loadings for these markers suggest that they represent the most influential variables in differentiating the data structure (Table 9).

Table 9.

Factor analysis of blood and CSF biomarkers showing explained variance and factor loadings

| Factor Analysis BBBM | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance explained | Communalities | Rotated component matrix | Measure | Bartlett's Test | ||||||

| Component | Eigenvalue | % Variance | Cumulative variance | Variable | Initial | Extraction | Component_1 | Component_2 | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin | p value |

| 1 | 1.786 | 35.729 | 35.729 | Aß1-42/1-40 ratio | 1 | 0.286 | – 0.491 | 0.213 | 0.555 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 1.262 | 25.236 | 60.966 | ApoE4 (UG/ml) | 1 | 0.695 | – 0.448 | – 0.703 | ||

| 3 | 0.889 | 17.775 | 78.74 | GFAP (ng/ml) | 1 | 0.648 | 0.770 | 0.235 | ||

| 4 | 0.598 | 11.95 | 90.69 | NFL (pg/ml) | 1 | 0.743 | 0.275 | 0.817 | ||

| 5 | 0.465 | 9.31 | 100 | pTau181 (pg/ml) | 1 | 0.676 | 0.822 | 0.007 | ||

| CSF markers | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2.507 | 0.552 | 0.552 | pTau181 CSF (pg/ml) | 1 | 0.861 | 0.860 | 0.348 | 0.683 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 0.899 | 0.300 | 0.852 | Aß1-42/1-40 ratio | 1 | 0.748 | – 0.855 | 0.134 | ||

| 3 | 0.475 | 0.552 | 0.552 | tTau181 (pg/ml) | 1 | 0.875 | 0.850 | 0.390 | ||

| 4 | 0.118 | 0.300 | 0.852 | sTREM2 (ng/ml) | 1 | 0.922 | 0.116 | 0.953 | ||

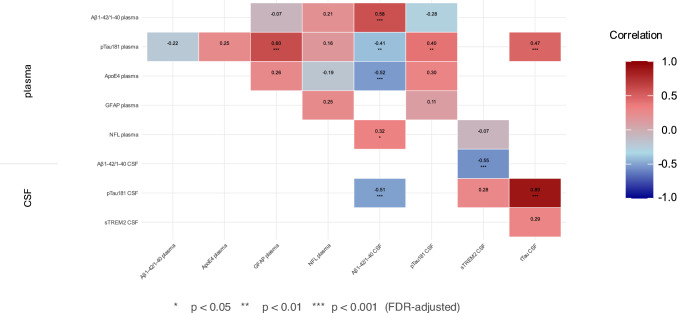

Correlation of BBBM and CSF biomarkers

Correlation analyses, adjusted for age and sex and corrected for multiple testing using FDR, revealed significant relationships between plasma and CSF biomarkers, highlighting the interplay between amyloid deposition, tau pathology and neurodegeneration (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of Blood-based Biomarkers and CSF Markers. Correlation analysis of blood-based biomarkers with CSF markers. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (FDR-adjusted)

Plasma and CSF pTau181 levels were moderately correlated (r = 0.398; p = 0.005), suggesting that plasma pTau181 may serve as a surrogate marker of central tau pathology. Plasma GFAP correlated strongly with plasma pTau181 (r = 0.601; p = 0.000), linking glial activation with tau processes. The CSF Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio was strongly negatively correlated with CSF pTau181 (r = – 0.505; p = 0.000) and CSF tTau (r = – 0.553; p = 0.000), reflecting the inverse relationship between amyloid deposition and tau accumulation. Plasma Aβ1-42/1-40 correlated weakly with plasma ApoE4 (r = – 0.322; p = 0.033) and CSF pTau181 (r = – 0.284; p = 0.0057) and moderately with its CSF counterpart (r = 0.578; p = 0.000), suggesting a partial overlap between peripheral and central amyloid markers. Given the strong association between ApoEε4 carrier status and AD pathology, it is important to consider whether these correlations are driven by the presence of ApoEε4 carriers rather than absolute protein levels.

CSF pTau181 and tTau showed a very strong correlation (r = 0.885; p = 0.000), suggesting their complementary reflection of tau-related neurodegeneration. Plasma NfL correlated moderately with CSF Aβ1-42/1-40 (r = 0.316; p = 0.035), reflecting the opposing pathological signatures of axonal damage and amyloid burden in the different groups. Finally, plasma GFAP showed a moderate correlation with plasma NfL, which was initially significant. However, this significance disappeared after adjustment for age, sex and multiple testing corrections (r = 0.253; p = 0.090).

The variance inflation factor (VIF) values for the analyzed biomarkers were below the commonly accepted threshold of 10 (ranging from 1.30 to 5.72), indicating no evidence of severe multicollinearity in the data. Taken together, these findings underscored the potential of plasma biomarkers to reflect central neurodegenerative processes, while highlighting important differences in peripheral and central biomarker dynamics or metabolism (Fig. 5 and Table 1, Supplementary Appendix).

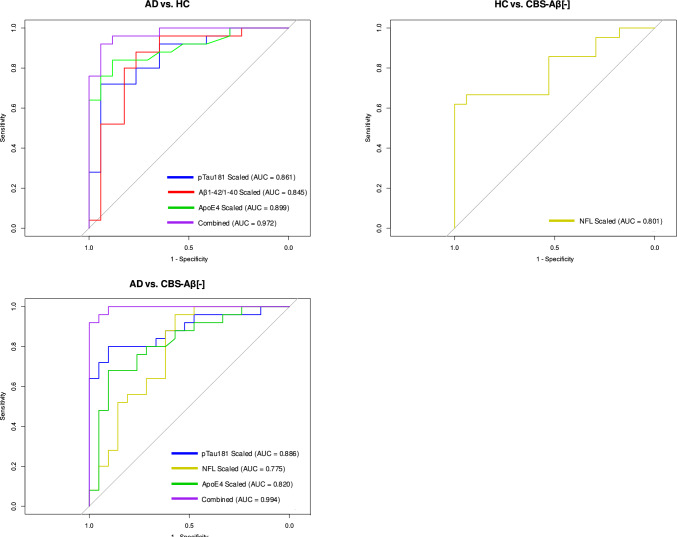

Fig. 5.

Blood biomarker-based Prediction versus CSF/PET-based Diagnosis. Comparison of blood biomarker-based predictions versus CSF/PET-based diagnoses. AUC values indicate the predictive power of scaled biomarkers and combined models

Diagnostic performance and utility of biomarkers

The diagnostic performance of the biomarkers varied significantly between disease groups, highlighting their strengths and limitations. Regression with backward selection identified pTau181, ApoE4 and NfL as important predictors of group differentiation, while the Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio presented specific limitations. Age was also significant in some comparisons, reflecting its role as a confounding factor. The inclusion of combined biomarker models further improved discrimination, as confirmed by ROC analyses (Table 10 and Fig. 5).

Table 10.

Predictors of disease group differentiation based on biomarker regression analysis

| Predictors of Disease Group Differentiation (Regression with backward selection) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Term | Estimate | Std.error | Statistic | P value | Conf.low | Conf.high | Adjusted p value (FDR) |

| AD | Intercept | 0.000 | 7.048 | – 2.512 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| pTau181 (pg/ml) | 5.81 E + 3 | 2.059 | 4.210 | 0.000 | 183.739 | 6.852 E + 5 | 0.000 | |

| Aß1-42/1-40 ratio | 0.000 | 23.364 | – 1.310 | 0.190 | 0.000 | 4.702 E + 4 | 0.166 | |

| GFAP (ng/ml) | 0.019 | 6.432 | – 0.616 | 0.538 | 0.000 | 2.487 E + 3 | 0.538 | |

| NFL (pg/ml) | 0.085 | 0.715 | – 3.447 | 0.001 | 0.016 | 0.279 | 0.000 | |

| ApoE4 (UG/ml) | 1.381 | 0.088 | 3.654 | 0.000 | 1.185 | 1.690 | 0.000 | |

| Sex | 0.355 | 0.748 | – 1.384 | 0.166 | 0.074 | 1.460 | 0.125 | |

| Age | 1.278 | 0.082 | 2.984 | 0.003 | 1.110 | 1.540 | 0.001 | |

| CBS-Aβ(–) | Intercept | 6.957 E + 3 | 4.294 | 2.060 | 0.039 | 2.120 | 5.537 E + 7 | 0.059 |

| pTau181 (pg/ml) | 0.002 | 1.467 | – 4.396 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | |

| Aß1-42/1-40 ratio | 0.002 | 15.335 | – 0.411 | 0.681 | 0.000 | 8.169 E + 9 | 0.681 | |

| NFL (pg/ml) | 5.657 | 0.380 | 4.555 | 0.000 | 2.968 | 13.328 | 0.000 | |

| Sex | 0.693 | 0.616 | – 0.595 | 0.552 | 0.200 | 2.318 | 0.662 | |

| Age | 0.886 | 0.050 | – 2.407 | 0.016 | 0.797 | 0.973 | 0.032 | |

| HC | Intercept | 0.000 | 4.707 | – 2.530 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.034 | 0.030 |

| pTau181 (pg/ml) | 0.677 | 0.995 | – 0.393 | 0.695 | 0.075 | 3.719 | 0.695 | |

| Aß1-42/1-40 ratio | 3.368 E + 41 | 24.199 | 3.951 | 0.000 | 5,222 E + 5 | 2.037 E + 11 | 0.001 | |

| GFAP (ng/ml) | 0.007 | 4.821 | – 1.020 | 0.308 | 0.000 | 82.816 | 0.410 | |

| NFL (pg/ml) | 0.317 | 0.364 | – 3.157 | 0.002 | 0.141 | 0.584 | 0.006 | |

| ApoE4 (UG/ml) | 0.889 | 0.066 | – 1.770 | 0.077 | 0.768 | 1.002 | 0.133 | |

| Sex | 2.753 | 0.585 | 1.732 | 0.083 | 0.898 | 9.135 | 0.133 | |

| Age | 1.032 | 0.042 | 0.759 | 0.448 | 0.951 | 1.124 | 0.512 | |

Adjusted for age and sex, FDR-corrected, CBS-Aβ( +) excluded by minimum size filtering

AD vs. HC

For discriminating AD from HC, the combined model of pTau181, ApoE4 and Aβ1-42/1-40 achieved the highest diagnostic accuracy (AUC = 0.972) with a sensitivity of 88.0% and specificity of 94.0%. On its own, ApoE4 (AUC = 0.832) showed excellent specificity (82.4%) at a cut-off of > 1.759 for AD cases. However, given the clear distinction in ApoE4 presence between AD and non-AD groups, a dichotomous classification (ApoEε4 carrier vs. non-carrier) may provide a more robust and clinically interpretable measure.

It was the most reliable biomarker in this comparison, reflecting its association with AD pathology. For pTau181 (AUC = 0.876) a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 94% was observed at a cut-off of > 1.349, highlighting its utility as a core biomarker. Regression analysis reinforced the importance of these biomarkers, with pTau181 showing the strongest effect size (estimate = 5.813, p < 0.001), followed by ApoE4 (estimate = 1.381, p < 0.001). Age also contributed significantly to group differentiation (Estimate = 1.278, p = 0.001), highlighting the importance of demographic factors in AD diagnosis.

High Aβ1-42/1-40 ratios were indicative of healthy controls (HC), as shown by regression analysis (Table 10; estimate = 3.368 E + 41, p = 0.001) and diagnostic performance metrics (Table 11; AUC = 0.836, sensitivity = 88.9%, specificity = 76.5%, Youden index = 0.645). Cut-off values of < 0.132 discriminated AD cases very well from HC (Fig. 2). However, modest differences between AD (mean 0.118) and HC (mean 0.135) with a ~ 17% reduction in AD and a small dynamic range (~ 0.833-fold change) reduced its reliability for differentiation. The high variability, wide confidence intervals and standard deviations, with lower confidence limits approaching zero, further indicated limited discriminatory power and substantial group overlap (Tables 10 and 11).

Table 11.

Diagnostic performance of biomarkers for disease differentiation using Bayesian regression

| Diagnostic Performance of Biomarkers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Biomarker | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden | Standardized cut-off | Original cut-off |

| AD vs. HC | pTau181 | 0.876 | 0.704 | 0.941 | 0.645 | 0.675 | 1.349 |

| Aβ1-42/1-40 | 0.836 | 0.889 | 0.765 | 0.654 | 0.518 | 0.132 | |

| ApoE4 | 0.832 | 0.778 | 0.824 | 0.601 | 0.478 | 1.759 | |

| AD vs. CBS-Aβ(–) | pTau181 | 0.892 | 0.704 | 0.963 | 0.665 | 0.665 | 1.394 |

| NfL | 0.738 | 0.960 | 0.571 | 0.531 | 0.318 | 4.189 | |

| ApoE4 | 0.819 | 0.741 | 0.923 | 0.664 | 0.613 | 2.179 | |

| CBS-Aβ(–) vs. HC | NfL | 0.786 | 0.577 | 0.941 | 0.518 | 0.717 | 1.997 |

Bayesian regression adjusted for age and sex

Initial model included pTau181, Aβ1-42/1-40, ApoE4, NfL and GFAP, non-significant predictive contribution not shown

AD vs. CBS-Aβ(–)

Discrimination between AD and CBS-Aβ(–) was most effective using pTau181, ApoE4 and NfL, with the combined model achieving an AUC of 0.994, coming close to the performance of an intensive clinical work-up. Individually, pTau181 (AUC = 0.892) showed sensitivity (70%) and specificity (96%) at a cut-off of > 1.394. Its strong performance highlights its role as a key biomarker for AD. ApoE4 (AUC = 0.819) showed a moderate sensitivity (74.1%) but a high specificity of 92.3% at a cut-off of > 2.179. NfL (AUC = 0.738) had a sensitivity of 96.0% but limited specificity (57.1%) at a cut-off of > 4.189 for CBS-Aβ(–) cases. Backward regression identified NfL (estimate = 5.657, p < 0.001) as the most influential biomarker, with age also contributed significantly (estimate = 0.886, p = 0.032). The strong AUC values highlight the complementary role of these markers in distinguishing AD from CBS-Aβ(–).

HC vs. CBS-Aβ(–)

Differentiating HC from CBS-Aβ(–) was more challenging, with NfL emerging as the most effective biomarker: NfL achieved an AUC of 0.786, with high specificity (94.1%) and low sensitivity (57.7%) at a cut-off of > 1.997 for CBS-Aβ(–) cases. Other biomarkers, including pTau181, Aβ1-42/1-40 and ApoE4, showed minimal discriminatory ability. Regression analysis supported the central role of high Aß1-42/1-40 ratio (estimate = 3.368 E + 41, p = 0.001) for the identification of HC and NfL (estimate = 0.317, p = 0.006) for CBS-Aβ(–) cases. The sensitivity issue with NfL in diagnosing CBS-Aβ(–) was likely due to the fact that only very high NfL levels (IQR: 2.580–5.770, Table 5) strongly indicated CBS-Aβ(–), while lower levels overlapped with other groups such as HC (IQR: 1.390–2.620) and AD (IQR: 1.920–3.160), highlighting the need for additional biomarkers or alternative diagnostic approaches (Fig. 5 and Tables 10, 11, 12).

Table 12.

Logistic regression improvement test comparing individual and combined biomarkers for predictive power

| Logistic Regression Improvement Test (K1 Logistic Regression) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD vs. HC | |||||

| Comparison | Residual Df | Residual Dev | Df | Deviance | P-value |

| AD vs. CBS-Aβ(–) | |||||

| pTau vs. Base | 40 | 38.892 | 1 | 17.8 | < 0.001 |

| Aβ vs. Base | 40 | 39.425 | 1 | 17.266 | < 0.001 |

| ApoE4 vs. Base | 40 | 31.863 | 1 | 24.828 | < 0.001 |

| pTau + Aβ vs. Base | 39 | 28.54 | 2 | 28.151 | < 0.001 |

| pTau + ApoE4 vs. Base | 39 | 20.111 | 2 | 36.58 | < 0.001 |

| HC vs. CBS-Aβ(–) | |||||

| pTau vs. Base | 44 | 36 | 1 | 27 | < 0.001 |

| NFL vs. Base | 44 | 47 | 1 | 16 | < 0.001 |

| ApoE4 vs. Base | 44 | 48 | 1 | 16 | < 0.001 |

| Combined vs. pTau | 42 | 7 | 2 | 29 | < 0.001 |

| Combined vs. NFL | 42 | 7 | 2 | 40 | < 0.001 |

| Combined vs. ApoE4 | 42 | 7 | 2 | 41 | < 0.001 |

Not applicable, only 1 biomarker in the model

Regression analyses highlighted the critical role of combined biomarker models, especially for comparisons involving AD cases. Individually, ApoE4, Aβ1-42/1-40 and pTau181 were the strongest performers for AD diagnosis, while NfL played a central role in CBS-Aβ(–) differentiation. For HC, the limited specificity of current biomarkers underlines the need for further research to refine diagnostic tools and improve differentiation from pathological cases.

Discussion

In this study, we gained valuable insights into the diagnostic utility of blood-based biomarkers (BBBMs) in Alzheimer's disease (AD) and corticobasal syndrome (CBS).

The excellent discriminatory power of pTau181 in distinguishing AD from HC is consistent with previous studies and suggests that plasma pTau181 represents a reliable plasma surrogate for AD pathology [6, 14, 30, 31]. While pTau217 has shown promising results in early-stage detection and stronger correlations with both amyloid and tau PET imaging, pTau181 remains a reliable and extensively validated marker, particularly in moderate to advanced disease stages. [4] Additionally, pTau181 offers distinct advantages, including greater robustness to confounding factors such as renal function [32]. Further longitudinal studies are necessary to fully elucidate the comparative trajectories of pTau181 and pTau217 across all stages of AD [33].

High Aβ1-42/Aβ1-40 ratio was a significant predictor of HC in this study, plasma levels correlated with CSF Aβ1-42/1-40, which is consistent with previous studies. The use of Aβ1-42/1-40 presented significant limitations [10, 14]: In particular, the ratio had a large confidence interval and the small dynamic range (fold change) between amyloid-positive and amyloid-negative cases, as reported in previous studies underlined the limited robustness of this biomarker [5, 34]. These results suggest that although the plasma Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio may theoretically contribute to disease modelling, its narrow fold change increases the risk that even minor fluctuations—such as those induced by metabolic influences—could distort results and compromise the biomarker's interpretability [35–37]. An additional challenge were the extremely low biomarker levels in plasma, typically in the picogram range, which may increase susceptibility to both analytical and pre-analytical variability and highlight the need for strict standardization of protocols [34, 38, 39].

In the present analysis, ApoE4 levels were elevated in AD cases but there are contradicting reports of reduced ApoE4 levels in AD [40]. As plasma ApoE4 levels remain relatively underexplored in the literature, our study offers a systematic contribution to this area of research. The increase in ApoE4 production may reflect a response to amyloid deposition, inflammatory processes, or lipid transport activity [13, 40–43]. Alternatively, it could be primarily related to ApoEε4 carrier status, rather than representing a continuous biomarker response. This distinction underscores the need for further investigation into whether a dichotomous classification (ApoEε4 carrier vs. non-carrier) provides a more informative clinical and biological interpretation. ApoE4 improved AD classification over and above the contributions of pTau181 and Aβ1-42/40, providing an independent diagnosis. Factor analysis grouped ApoE4 with NfL on a distinct component, suggesting a link to neurodegeneration and axonal damage. This indicated that ApoE4 captures complementary pathological processes beyond tau and amyloid, such as neuroinflammation or neuronal repair. The inclusion of ApoE4 in multi-biomarker panels in clinical practice remains questionable due to regulatory restrictions, such as those imposed by the Genetic Diagnostics Act, which may limit its widespread use.

NfL was found to be the most reliable biomarker for CBS-Aβ(–), reflecting its role as a marker of axonal damage and brain atrophy in neurodegenerative diseases, underlining its usefulness in identifying non-amyloid pathologies. These findings were consistent with previous studies reporting elevated NfL levels in frontotemporal dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other tauopathies [14–16]. The challenge with NfL lied in its limited sensitivity, as its diagnostic value for CBS-Aβ(–) relies on extreme elevations, highlighting the need for complementary markers to improve differentiation.

The limited contribution of GFAP to group differentiation was notable given its recognized role in AD as a marker of astroglial activation and early neuroinflammation, processes common to many neurodegenerative diseases [44, 45]. GFAP and pTau181 were grouped together by factor analysis, which provided an objective perspective. However, the overlaps of GFAP levels across the groups reduced its discriminatory power. While GFAP may be more relevant in preclinical stages or combined with other markers, its utility in this study was limited [44–48]. Based on the data, GFAP may serve more as a marker of general neurodegenerative processes rather than as a specific biomarker for distinguishing between diagnostic groups.

Strengths of the study

This study has several strengths, including biomarker-guided participant selection, a comprehensive diagnostic work-up, and standardized procedures for sample handling and analysis. The uniform protocols minimize inconsistencies in sample handling and assay conditions, increasing the validity of the results. Automated assays have demonstrated high accuracy in detecting brain amyloid compared to amyloid PET, further enhancing reliability [3, 5, 49, 50].

Limitations of the study

The small sample size, especially for CBS-Aβ(+) cases, limited the generalizability of the results and may have inflated AUC values, especially with multiple biomarkers. Smaller group sizes are likely to have increased the variance of AUC estimates, risking overfitting and overestimation of model performance. In addition, the clear clinical definitions in this highly selected population contributed to the high AUC values but limit the applicability of these findings to more heterogeneous cohorts. The Bayesian regression approach, including posterior distributions, provided robust uncertainty quantification to address potential overestimation of biomarker performance. Nevertheless, validation in larger, unselected cohorts will be essential to confirm these findings and refine biomarker applications in real-world settings.

Another limitation relates to the use of the MMSE as the primary cognitive assessment tool. Although it allows for standardized comparisons, its limited scope, particularly for assessing non-memory cognitive domains, reduces the granularity of subgroup differentiation. This is particularly relevant for CBS cases, as CBS often presents with heterogeneous cognitive and motor phenotypes that may be better captured by more detailed neuropsychological assessments [51]. Furthermore, grouping MCI due to AD and probable AD dementia into a single "Alzheimer's disease" group further limits stratification by disease stage, although it aligns with the continuum of disease progression observed in clinical practice [9, 22].

Diagnostic utility of biomarkers

However, when considering diagnostic utility, the larger variability observed in BBBMs might be attributed to peripheral influences, such as inflammation or metabolic factors [39]. While CSF biomarkers are more directly linked to central nervous system pathology, BBBMs offer comparable diagnostic potential and greater accessibility.

Conclusions

However, in this highly selected cohort, BBBMs showed remarkable potential to approach the discriminatory power of CSF and PET-based diagnostics, particularly in distinguishing AD from HC. This analysis highlights the strengths and limitations of BBBMs, demonstrating that while pTau181 and ApoE4 performed exceptionally well in discriminating AD from HC, the Aβ1-42/1-40 ratio exhibited some limitations and NfL emerged as a key marker in classifying CBS-Aβ(–), despite issues with sensitivity. These findings highlight the potential for BBBMs to serve as non-invasive alternatives to more invasive diagnostic modalities. The results emphasize tailored diagnostic strategies using multi-biomarker panels for specific group comparisons and the need for research to refine models and address confounding factors. Moving forward, validation in larger cohorts and unselected populations will be essential for the adoption of BBBMs to improve their reliability and applicability in different clinical contexts [52–54].

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants and their families for their participation and time. The authors would like to thank Sylvia de Jonge and Karin Neumeier for their excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer´s disease

- Aβ

Amyloid-β

- ApoE4

Apolipoprotein E protein (associated with lipid metabolism and AD risk)

- ApoEε4

APOE Genotype variant (ε4 allele of the APOE gene)

- BBBM

Blood-based biomarker

- CERAD

The extended Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease battery

- CBS

Corticobasal syndrome

- CBS-Aß(+)

Aß positive CBS cases

- CBS-Aß(–)

Aß negative CBS cases

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating Scale

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- FCSRT

Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test

- FDR

False Discovery Rate

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HC

Healthy control

- MMSE

Mini Mental Status Examination

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- n.a.

not applicable

- NfL

Neurofilament light chain

- p-tau181

Phosphorylated tau at threonine 181

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- TMT

Trail Making Test

- SD

Standard deviation

- SUVR

Standardized uptake value ratio

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Carolin Kurz, Alexander Jethwa, Johannes Levin, Günter Höglinger, Boris-Stephan Rauchmann, Robert Perneczky. Methodology: Carolin Kurz, Günter Höglinger, Boris-Stephan Rauchmann. Formal analysis: Carolin Kurz, Laura Carli, Sayuri Hortsch. Investigation: Carolin Kurz, Selim Üstün Gürsel, Daniel Keeser, Lena Burow, Jan Haeckert, Carolin A M Koriath, Maia Tatò, Julia Utecht, Boris Papazov, Estrella Morenas-Rodriguez, Carla Palleis, Endy Weidinger, Sophia Stoecklein, Johannes Levin, Günter Höglinger, Boris-Stephan Rauchmann, Robert Perneczky. Resources: Carolin Kurz, Isabelle Schrurs, Margherita Carboni, Daniel Keeser, Matthias Brendel, Carla Palleis, Johannes Levin, Günter Höglinger, Boris-Stephan Rauchmann, Robert Perneczky. Data Curation: Carolin Kurz, Laura Carli. Writing – Original Draft: Carolin Kurz, Laura Carli, Tobias Bittner, Robert Perneczky. Writing – Review & Editing: Carolin Kurz, Laura Carli, Selim Üstün Gürsel, Isabelle Schrurs, Alexander Jethwa, Margherita Carboni, Tobias Bittner, Sayuri Hortsch, Daniel Keeser, Matthias Brendel, Lena Burow, Jan Haeckert, Carolin A M Koriath, Maia Tatò, Julia Utecht, Boris Papazov, Estrella Morenas-Rodriguez, Oliver Pogarell, Carla Palleis, Endy Weidinger, Sophia Stoecklein, Johannes Levin, Günter Höglinger, Boris-Stephan Rauchmann, Robert Perneczky. Visualization: Carolin Kurz. Supervision: Matthias Brendel, Oliver Pogarell, Sophia Stoecklein, Johannes Levin, Günter Höglinger, Boris-Stephan Rauchmann, Robert Perneczky. Project Administration: Oliver Pogarell, Günter Höglinger, Robert Perneczky. Funding acquisition: Günter Höglinger, Boris-Stephan Rauchmann, Robert Perneczky.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy within the framework of the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology [grant numbers EXC 2145 SyNergy – ID 390857198] and Hirnliga (Manfred-Strohscheer Stiftung). The project 'ActiGlia' was funded within the framework of the “Impuls‐ und Vernetzungsfonds” supported by the Helmholtz Association. The authors thank Christian Haass, PhD for his support. R.P. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the framework of the German Excellence Initiative, the Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology, the Davos Alzheimer Collaborative, the VERUM Foundation, the Robert Vogel Foundation, the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR), the Sheffield Biomedical Research Center, the University of Cambridge, and the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), the Sheffield Biomedical Research Centre, the University of Cambridge, the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich, the Strategic Partnership within the German Excellence Initiative and the Excellence Strategy, and the European Commission within the Innovative Health Initiative program (project 101,132,356). Roche Diagnostics supported the measurement of the blood biomarker samples, the company had no role in the interpretation of the data. The NeuroToolKit is a panel of exploratory prototype assays designed to robustly evaluate biomarkers associated with key pathologic events characteristic of AD and other neurological disorders, used for research purposes only and not approved for clinical use (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). COBAS and ELECSYS are trademarks of Roche.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

S.H., A.J. are full-time employees of Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany, I.S. M.C. are full-time employee of Roche Diagnostics International Ltd, Rotkreuz, Switzerland and T.B. is full-time employee and stakeholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland, which manufactured the blood biomarkers that were investigated in this study. C.K. has received speaker honoraria from Roche Diagnostics International Ltd, Rotkreuz, Switzerland. R.P. has received consultancy fees and speaker honoraria from Roche. G. H. serves as a consultant for Abbvie, Alzprotect, Amylyx, Aprinoia, Asceneuron, Bayer, Bial, Biogen, Biohaven, Epidarex, Ferrer, Kyowa Kirin, Lundbeck, Novartis, Retrotope, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Takeda, Teva, UCB; received honoraria for scientific presentations from Abbvie, Bayer, Bial, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Kyowa Kirin, Pfizer, Roche, Teva, UCB, Zambon. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised due to Unstructured Abstract in the body text. Now, it has been Corrected to structured Abstract.

Change history

5/12/2025

The original online version of this article was revised due to Unstructured Abstract in the body text. Now, it has been Corrected to structured Abstract.

References

- 1.Leuzy A, Mattsson-Carlgren N, Palmqvist S, Janelidze S, Dage JL, Hansson O (2022) Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med 14(1):e14408. 10.15252/emmm.202114408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmqvist S et al (2024) Blood biomarkers to detect Alzheimer disease in primary care and secondary care. JAMA 332(15):1245–1257. 10.1001/jama.2024.13855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansson O et al (2018) CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-beta PET and predict clinical progression: a study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimers Dement 14(11):1470–1481. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janelidze S et al (2023) Head-to-head comparison of 10 plasma phospho-tau assays in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 146(4):1592–1601. 10.1093/brain/awac333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janelidze S et al (2021) Head-to-head comparison of 8 plasma amyloid-beta 42/40 assays in Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 78(11):1375–1382. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Meyer S et al (2020) Comparison of ELISA- and SIMOA-based quantification of plasma Abeta ratios for early detection of cerebral amyloidosis. Alzheimers Res Ther 12(1):162. 10.1186/s13195-020-00728-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koga S, Josephs KA, Aiba I, Yoshida M, Dickson DW (2022) Neuropathology and emerging biomarkers in corticobasal syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 93(9):919–929. 10.1136/jnnp-2021-328586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabbari E et al (2020) Diagnosis across the spectrum of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal syndrome. JAMA Neurol 77(3):377–387. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoglinger GU et al (2017) Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: the movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 32(6):853–864. 10.1002/mds.26987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashton NJ et al (2021) The validation status of blood biomarkers of amyloid and phospho-tau assessed with the 5-phase development framework for AD biomarkers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 48(7):2140–2156. 10.1007/s00259-021-05253-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samudra N, Lane-Donovan C, VandeVrede L, Boxer AL (2023) Tau pathology in neurodegenerative disease: disease mechanisms and therapeutic avenues. J Clin Invest. 10.1172/JCI168553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahimi J, Kovacs GG (2014) Prevalence of mixed pathologies in the aging brain. Alzheimers Res Ther 6(9):82. 10.1186/s13195-014-0082-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun YY, Wang Z, Huang HC (2023) Roles of ApoE4 on the pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease and the potential therapeutic approaches. Cell Mol Neurobiol 43(7):3115–3136. 10.1007/s10571-023-01365-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grothe MJ et al (2021) Associations of fully automated CSF and novel plasma biomarkers with Alzheimer disease neuropathology at autopsy. Neurology 97(12):e1229–e1242. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalil M et al (2018) Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 14(10):577–589. 10.1038/s41582-018-0058-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansson O et al (2017) Blood-based NfL: a biomarker for differential diagnosis of parkinsonian disorder. Neurology 88(10):930–937. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pucci E, Belardinelli N, Borsetti G, Rodriguez D, Signorino M (2001) Information and competency for consent to pharmacologic clinical trials in Alzheimer disease: an empirical analysis in patients and family caregivers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 15(3):146–154. 10.1097/00002093-200107000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKhann GM et al (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7(3):263–269. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert MS et al (2011) The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7(3):270–279. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong MJ et al (2013) Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology 80(5):496–503. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f0fd1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shir D et al (2023) Clinicoradiologic and neuropathologic evaluation of corticobasal syndrome. Neurology 101(3):e289–e299. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnham SC et al (2016) Clinical and cognitive trajectories in cognitively healthy elderly individuals with suspected non-Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology (SNAP) or Alzheimer’s disease pathology: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol 15(10):1044–1053. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30125-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis C et al (2015) Phase 3 trial of flutemetamol labeled with radioactive fluorine 18 imaging and neuritic plaque density. JAMA Neurol 72(3):287–294. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palleis C et al (2021) Cortical [(18) F]PI-2620 binding differentiates corticobasal syndrome subtypes. Mov Disord 36(9):2104–2115. 10.1002/mds.28624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spallazzi M et al (2019) CSF biomarkers and amyloid PET: concordance and diagnostic accuracy in a MCI cohort. Acta Neurol Belg 119(3):445–452. 10.1007/s13760-019-01112-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmqvist S et al (2015) Detailed comparison of amyloid PET and CSF biomarkers for identifying early Alzheimer disease. Neurology 85(14):1240–1249. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalman JL et al (2022) Biobanking in everyday clinical practice in psychiatry: the Munich mental health Biobank. Front Psychiatry 13:934640. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.934640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL (2020) [Online]. Available: http://www.rstudio.com

- 30.Janelidze S et al (2020) Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer’s dementia. Nat Med 26(3):379–386. 10.1038/s41591-020-0755-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verberk IMW et al (2020) Combination of plasma amyloid beta((1-42/1-40)) and glial fibrillary acidic protein strongly associates with cerebral amyloid pathology. Alzheimers Res Ther 12(1):118. 10.1186/s13195-020-00682-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehmann S et al (2024) Clinical value of plasma ALZpath pTau217 immunoassay for assessing mild cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 95(11):1046–1053. 10.1136/jnnp-2024-333467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karikari TK et al (2021) Head-to-head comparison of clinical performance of CSF phospho-tau T181 and T217 biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Alzheimers Dement 17(5):755–767. 10.1002/alz.12236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabe C et al (2023) Clinical performance and robustness evaluation of plasma amyloid-beta(42/40) prescreening. Alzheimers Dement 19(4):1393–1402. 10.1002/alz.12801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayden KM et al (2024) Association between modifiable risk factors and levels of blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s and related dementias in the look AHEAD cohort. JAR Life 13:1–21. 10.14283/jarlife.2024.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber H et al (2023) Levels of Alzheimer’s disease blood biomarkers are altered after food intake: a pilot intervention study in healthy adults. Alzheimers Dement 19(12):5531–5540. 10.1002/alz.13163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pichet Binette A et al (2023) Confounding factors of Alzheimer’s disease plasma biomarkers and their impact on clinical performance. Alzheimers Dement 19(4):1403–1414. 10.1002/alz.12787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurz C et al (2023) Impact of pre-analytical sample handling factors on plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 165(1):95–105. 10.1111/jnc.15757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholl M et al (2024) Challenges in the practical implementation of blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Healthy Longev 5(10):100630. 10.1016/j.lanhl.2024.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song F et al (2012) Plasma apolipoprotein levels are associated with cognitive status and decline in a community cohort of older individuals. PLoS ONE 7(6):e34078. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta VB et al (2015) Follow-up plasma apolipoprotein E levels in the Australian imaging, biomarkers and lifestyle flagship study of ageing (AIBL) cohort. Alzheimers Res Ther 7(1):16. 10.1186/s13195-015-0105-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taddei K, Clarnette R, Gandy SE, Martins RN (1997) Increased plasma apolipoprotein E (apoE) levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett 223(1):29–32. 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13394-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorey E, Chang N, Liu QY, Yang Z, Zhang W (2014) Apolipoprotein E, amyloid-beta, and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Bull 30(2):317–330. 10.1007/s12264-013-1422-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishiki A et al (2016) Glial fibrillar acidic protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurochem 136(2):258–261. 10.1111/jnc.13399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oeckl P et al (2019) Glial fibrillary acidic protein in serum is increased in Alzheimer’s disease and correlates with cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 67(2):481–488. 10.3233/JAD-180325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hol EM, Pekny M (2015) Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the astrocyte intermediate filament system in diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Cell Biol 32:121–130. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prins S, de Kam ML, Teunissen CE, Groeneveld GJ (2022) Inflammatory plasma biomarkers in subjects with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 14(1):106. 10.1186/s13195-022-01051-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perna L et al (2023) Subjective cognitive complaints and blood biomarkers of neurodegenerative diseases: a longitudinal cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther 15(1):198. 10.1186/s13195-023-01341-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmqvist S et al (2023) An accurate fully automated panel of plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 19(4):1204–1215. 10.1002/alz.12751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thijssen EH et al (2020) Diagnostic value of plasma phosphorylated tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat Med 26(3):387–397. 10.1038/s41591-020-0762-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Stefano F et al (2016) The phenotypical core of Alzheimer’s disease-related and nonrelated variants of the corticobasal syndrome: a systematic clinical, neuropsychological, imaging, and biomarker study. Alzheimers Dement 12(7):786–795. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lantero Rodriguez J et al (2020) Plasma p-tau181 accurately predicts Alzheimer’s disease pathology at least 8 years prior to post-mortem and improves the clinical characterisation of cognitive decline. Acta Neuropathol 140(3):267–278. 10.1007/s00401-020-02195-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karikari TK et al (2020) Blood phosphorylated tau 181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: a diagnostic performance and prediction modelling study using data from four prospective cohorts. The Lancet Neurology 19(5):422–433. 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30071-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pontecorvo MJ et al (2022) Association of donanemab treatment with exploratory plasma biomarkers in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: a secondary analysis of the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 79(12):1250–1259. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.3392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.