Abstract

The routine production and storage of frozen doughs are still problematic. Although commercial baker's yeast is highly resistant to environmental stress conditions, it rapidly loses stress resistance during dough preparation due to the initiation of fermentation. As a result, the yeast loses gassing power significantly during storage of frozen doughs. We obtained freeze-tolerant mutants of polyploid industrial strains following screening for survival in doughs prepared with UV-mutagenized yeast and subjected to 200 freeze-thaw cycles. Two strains in the S47 background with a normal growth rate and the best freeze tolerance under laboratory conditions were selected for production in a 20-liter pilot fermentor. Before frozen storage, the AT25 mutant produced on the 20-liter pilot scale had a 10% higher gassing power capacity than the S47 strain, while the opposite was observed for cells produced under laboratory conditions. AT25 also retained more freeze tolerance during the initiation of fermentation in liquid cultures and more gassing power during storage of frozen doughs. Other industrially important properties (yield, growth rate, nitrogen assimilation, and phosphorus content) were very similar. AT25 had only half of the DNA content of S47, and its cell size was much smaller. Several diploid segregants of S47 had freeze tolerances similar to that of AT25 but inferior performance for other properties, while an AT25-derived tetraploid, TAT25, showed only slightly improved freeze tolerance compared to S47. When AT25 was cultured in a 20,000-liter fermentor under industrial conditions, it retained its superior performance and thus appears to be promising for use in frozen dough production. Our results also show that a diploid strain can perform at least as well as a tetraploid strain for commercial baker's yeast production and usage.

Frozen doughs are of increasing importance in the bakery sector (2, 18). These doughs permit the separation of the processes of dough production and baking and also permit large-scale production and distribution of doughs in frozen form independent of the subsequent baking process. Before freezing of the dough, a short (30-min to 1-h maximum) prefermentation period is required if the bread is to have proper texture (13, 14). The initiation of fermentation in baker's yeast, which occurs when yeast is mixed with dough, is associated with a rapid loss of stress resistance, including freeze resistance (17, 31, 32). Consequently, the dough-rising capacity of yeast drops considerably when the doughs are frozen after the initial prefermentation period. To overcome this problem, more yeast and/or additives are used in the preparation of frozen doughs, and special dough preparation methods have been developed (13, 17). These techniques may have negative consequences, e.g., a yeasty taste of the bread when more yeast is used; furthermore, the requirement of special dough preparation methods has restricted the spread of frozen dough usage.

The rapid drop of stress resistance during the initiation of fermentation in baker's yeast is due to activation of the cyclic AMP (cAMP)-protein kinase A (PKA) pathway (23, 28). A glucose-induced increase in cAMP causes activation of PKA, which results in activation of trehalase and mobilization of trehalose concomitant with a rapid loss in stress tolerance. Trehalose is a major determinant of stress resistance in yeast (33). Freeze tolerance and trehalose content are also correlated in yeast (8, 11, 15, 22). However, maintenance of a high trehalose level during the initiation of fermentation in strains in which trehalase activity has been eliminated is not sufficient to prevent the rapid loss of stress resistance after addition of glucose (31). This result supports the hypothesis that the initiation of fermentation causes the disappearance of other factors that are essential for stress resistance and without which trehalose cannot support a further improvement in stress resistance.

Screening for mutants which are deficient in fermentation-induced loss of stress resistance (fil mutants) resulted in a mutant, the fil1 mutant, with a better maintenance of stress resistance and with normal growth and fermentation rate (32). Although fil mutations by definition do not have to be located in the cAMP pathway, the fil1 mutant had a partially inactivating point mutation in adenylate cyclase. This fits with the known involvement of the cAMP pathway in determining yeast stress resistance (28, 29). The phenotype of the fil1 mutant demonstrated that high stress resistance and high metabolic activity are not mutually incompatible cellular properties, a possibility that has been considered previously (2). Since the cAMP-PKA pathway has many pleiotropic effects on yeast cells (19, 29) and transfer of the fil1 mutation into polyploid industrial strains proved to be technically very difficult, we decided to isolate fil-type mutants directly in industrial yeast strains. Moreover, we chose to use selection conditions for the mutants that resembled as closely as possible the conditions under which the industrial yeast has to display enhanced freeze resistance. We prepared small doughs with mutagenized cultures and subjected them, after a short prefermentation, to multiple rounds of freeze-thaw treatments.

The development of yeast strains with better freeze resistance, especially during active fermentation, would provide a more practical solution to the problems of frozen dough production. Freeze-tolerant yeast strains have been identified following mutagenesis (27) and from surveys of natural isolates (12, 22). However, there are no strains available that combine the optimal pleiotropic phenotype of the best commercial strains with a higher freeze resistance. Our objective in this study was to obtain and characterize such a strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

S47 and L13 are polyploid (tetraploid and aneuploid) industrial strains produced and commercialized by Lesaffre (Marcq-en-Barœul, France) and Algist Bruggeman NV (Ghent, Belgium). AT25 and AT28 are derived from S47, and AT2 is derived from L13.

Cultivation conditions.

Yeast cells were grown in Erlenmeyer flasks (50-ml cultures in 250-ml flasks) in a rotary shaker (200 rpm) using specific medium, as indicated below. On molasses plates, yeast cells were grown on solid medium and harvested by scraping as described previously (6). Production on pilot scale was performed in a 20-liter fermentor in fed-batch mode (31), and production on industrial scale was performed in a 20,000-liter fermentor in fed-batch mode (5). Compressed yeast was obtained as described by Reed and Nagodawithana (26).

Selection of freeze-tolerant mutants.

Strains were cultured in liquid yeast extract-molasses [5 g of yeast extract per liter, 5 g of molasses per liter, and 500 mg of (NH4)2HPO4 per liter, adjusted to pH 5.0 to 5.5 with H2SO4] medium to stationary phase. The cells were spread on yeast extract-molasses plates and mutagenized with 10 mJ of UV light (254 nm; GS Gene Linker from Bio-Rad) per cm2, resulting in about 25% survival. After a 65-h recovery period at 30°C, the mutagenized cells were washed from the plates with 6 ml of H2O per plate and used to prepare small doughs (7.5 g of white flour, 0.15 g of NaCl, and 5.5 ml of a yeast suspension at an optical density at 600 nm of 50 to 55). The doughs were divided into 0.5-g portions which, after incubation for 30 min at 30°C (prefermentation period), were frozen in microvial tubes placed in a freezer at −20°C. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles (up to 200) were performed manually with intervals of at least 3 h between freezing and thawing. Thawing was done at room temperature for 30 min, after which the doughs were frozen again. Samples were taken at regular time intervals to determine yeast viability. The viability was determined by extraction of the cells from the dough by mixing the dough for 1 min in the presence of glass beads (3-mm diameter) in 2 ml of TS medium (1 g of tryptone per liter and 9 g of NaCl per liter) supplemented with 20 μg of kanamycin per ml and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. Serial dilutions were plated out, and colonies were counted after 2 days of incubation at 30°C. The number of viable cells extracted from a fresh dough was taken as 100%.

Determination of freeze resistance in liquid medium by using a viability test.

Cells were grown to stationary phase in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 2% glucose). They were then diluted to about 1.1 × 107 cells/ml with YP (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone) and incubated for 30 min at 30°C. Thereafter, the cultures were diluted 1:25 with YPD and incubated in this medium at 30°C to initiate fermentation and induce the transition from stationary phase to log phase. Samples were taken at different time points, from 0 min to 120 min, to determine freeze resistance. After a 1:25 dilution with water, 1-ml samples were frozen for 1 h or 1 week at −30°C. Nonfrozen controls were diluted and plated immediately on YPD plates, and the number of colonies was counted after incubation at 30°C for 2 days. Frozen samples were thawed, diluted with H2O, and plated on YPD for colony counting, as appropriate.

Determination of heat resistance in liquid medium by using a viability test.

Heat resistance in liquid medium was assessed in the same way as freeze resistance, except that the cultures were heated to 49°C for 15 min instead of being frozen.

Determination of RGC after freezing.

Cells were grown to stationary phase in YPD, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in YP to a final optical density at 600 nm of 15. After preincubation for 30 min at 30°C, glucose was added to a final concentration of 100 mM. The cells were incubated at 30°C in the presence of glucose, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in cold YP. Nonfrozen controls were kept for 1 day at 4°C, and the other batches were frozen at −30°C for 1 day. Glucose consumption was determined in the nonfrozen controls and in the frozen batches that were first thawed and kept on ice. For that purpose, 400 μl of 10 mM glucose solution was added to 40 μl of cell suspension, giving a final glucose concentration of 9.1 mM. After 120 min of incubation, the amount of glucose that remained in the medium was measured with Trinder reagent (catalog no. 315-100; Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, Mo.). The residual glucose consumption (RGC) was expressed as the amount of glucose consumed by cells that had been frozen times 100 divided by the amount of glucose consumed by the nonfrozen cells.

Determination of gassing power.

The gassing power was determined in a fermentometer (4). The results are expressed as the volume in milliliters of gas produced in 2 h at 30°C from a dough made with 20 g of flour and 160 mg of yeast (dry mass) and 15 ml of H2O. Kneading was done by hand with a spatula for 45 s.

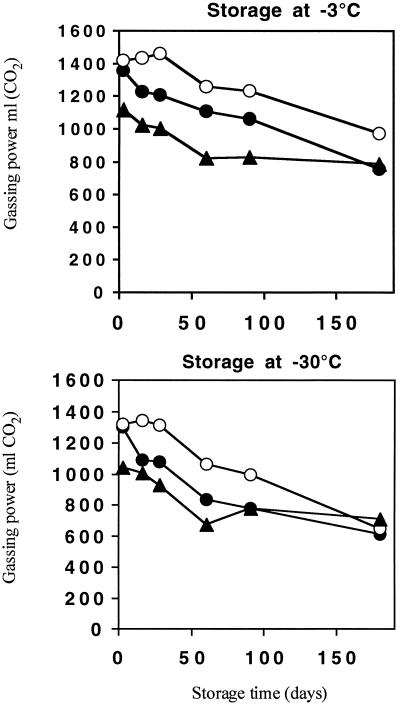

Gassing power in frozen dough experiments.

Dough was made with 100 g of flour, 2 g of salt, 62 g of water, and 6 g of compressed yeast. After 15 min of mechanical kneading in a spiral mixer (FPI 50; VMI, Montaigu, France), the dough was frozen at −3°C core temperature (moderate freezing) or −30°C core temperature (severe freezing). Subsequent storage was at −20°C. At different time intervals, doughs were thawed at 0°C. Gassing power was measured with a Zymotachigraph with 200 g of dough at 27°C for 2.5 h.

Determination of stability during microdrying.

The stability during microdrying was measured as described by Clément and Loïez (5). One gram (dry mass) of yeast was put in a glass tube (20-mm diameter, 400-mm height). The tube was vibrated and flushed with compressed air at 20 to 25°C for 10 min.

Biochemical analyses.

In general, analyses were done with yeast stored for 12 to 24 h at 4°C. Previous comparisons of material analyzed immediately and after 1 day of storage have shown that this short storage period has no influence on the results. Dry matter was determined following overnight desiccation in a ventilated oven at 105 ± 2°C. Total nitrogen content was determined by the Kjeldahl method (1) after mineralization with H2SO4. For phosphorus determination, yeast samples containing 2 to 5 mg of phosphorus were first mineralized with H2SO4 in the presence of a catalyst (TEC 9000.025; Tecator, Foss France, Nanterre, France) for 1 h. The mineralized samples were diluted with distilled water and added to ammonium molybdate [(NH4)6Mo7O24] (8 mM final concentration) and ammonium vanadate [NH4VO3] (2 mM final concentration). The optical density was measured at 400 nm. Lipids were extracted with chloroform-methanol (2:1) from glass microbead-disrupted cells (10). The total soluble carbohydrate content was determined by the sulfuric anthrone method (3). Trehalose was extracted from yeast using trichloroacetic acid, followed by measurement by the sulfuric anthrone method (30).

Determination of DNA content by flow cytometry.

The DNA content was determined by flow cytometry with propidium iodide as a DNA stain (25).

Tetraploidization of AT25.

The diploid AT25 (MATa/α) strain was transformed with pFL39kanMX-GAL1HO in order to induce mating type switch. This plasmid is derived from pFL39GAL1HO (a multicopy plasmid kindly provided by Patrick Linder), which was modified with a dominant marker gene for use in prototrophic strains by cloning the EcoRV/PvuII fragment containing the loxP-KanMX4-loxP cassette from pUG6 (9) in the EcoRV site. Single colonies were checked for mating type and ploidy. Fifteen MATa/a diploids and one MATα/α diploid were obtained. After plasmid loss, a MATa/a strain was crossed with the MATα/α strain, and zygotes were isolated with a micromanipulator. For several strains, the tetraploid DNA content was confirmed by flow cytometry and an a/a/α/α mating type was confirmed by PCR. Three strains, TAT25-1, -2, and -3, were selected for further characterization.

RESULTS

Selection of freeze-tolerant mutants.

Two polyploid and aneuploid industrial yeast strains, S47 and L13, were used for selection of freeze-resistant mutants by subjecting small doughs prepared with UV-mutagenized cells to repeated freeze-thaw cycles. An exponential decrease in the number of surviving cells was observed with increasing number of freeze-thaw cycles (results not shown). After about 200 freeze-thaw cycles, we recovered 21 viable cell lines in the S47 background and 36 in the L13 background. These cell lines were not necessarily independent, since the cells were allowed to grow for 65 h after the UV mutagenesis treatment. When tested individually in stationary phase and after 30 min of fermentation in liquid medium, these strains varied widely in freeze resistance. Many of the mutants in both backgrounds had a reduced-to-low growth rate. The most resistant (after 30 min of fermentation) strains with a normal growth rate were AT25 and AT28 for the S47 background and AT2 for the L13 background.

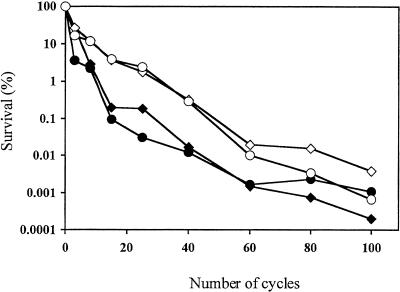

Small doughs (0.25 g) prepared with the AT25 and AT2 mutant strains and the S47 and L13 parent strains were subjected to multiple freeze-thaw treatments (Fig. 1). The survival percentage decreased more slowly for the two mutant strains than for their parents. Beyond 60 cycles, the difference between AT25 and S47 disappeared. Since S47 is better suited for the production of frozen doughs than L13, we concentrated on the S47-derived freeze-tolerant strains.

FIG. 1.

Yeast survival in small doughs as a function of the number of freeze-thaw cycles (−20°C and room temperature). L13 (♦) and S47 (•), wild-type industrial strains; AT2 (⋄) and AT25 (○), mutants derived from, respectively, L13 and S47. Standard errors are around 25% of the percent survival values for four independent measurements.

Stress resistance of AT25 and AT28 under laboratory conditions.

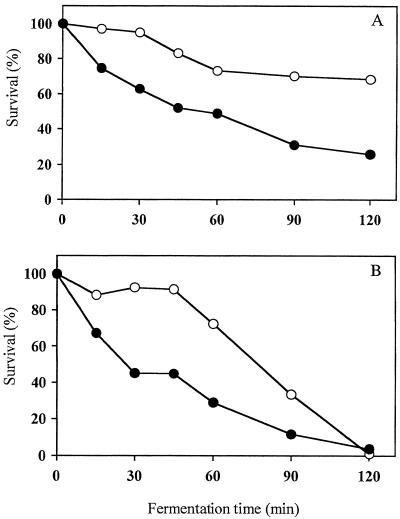

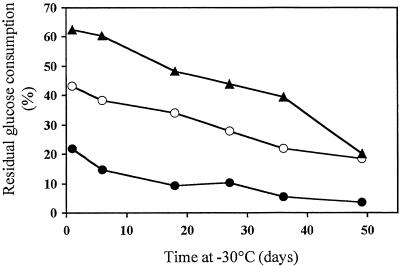

In YP-maltose medium the growth rates of S47, AT25, and AT28 were identical, while in YPD and YP-molasses, the lag phase for AT25 was slightly longer but the exponential growth rate was identical (results not shown). The fermentation-induced loss of freeze and heat resistance was clearly delayed in AT25 relative to S47 (Fig. 2). During long-term frozen storage at −30°C, AT25 and AT28 retained more activity than did S47 as determined by the RGC after freezing (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Loss of stress resistance during the initiation of fermentation in liquid medium. (A) Freeze stress (1 h at −30°C); (B) heat stress (15 min at 49°C). •, S47; ○, AT25. The standard error is usually between 1 and 10% and a maximum of 15% of the survival values for three independent measurements.

FIG. 3.

Effect of long-term frozen storage on RGC capacity. After 30 min of fermentation in liquid medium, samples were frozen for different time periods at −30°C. •, S47; ○, AT25; (▴) AT28. Standard errors for six independent measurements are around 3.5%.

Stress resistance of AT25 and AT28 after production on molasses plates and on pilot scale.

When grown on nutrient plates with molasses, AT25, AT28, and S47 had similar yields: 37 to 40 g (dry mass) of yeast per 100 g of sucrose for AT25, 35 to 41 g for AT28, and 39 to 41 g for S47. The fermentation power, measured as CO2 production (milliliters of CO2 produced in 2 h), was about 10 to 15% lower for AT25 and AT28 cells than for S47 cells. For AT25 the fermentation capacity was 112 to 125 ml of CO2, for AT28 it was 112 to 129 ml of CO2, and for S47 it was 129 to 145 ml of CO2.

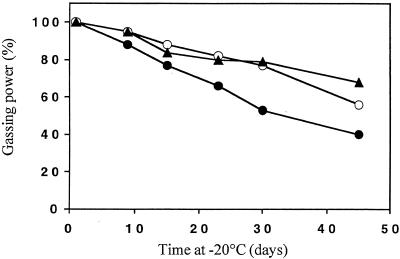

Small doughs (20 g of flour and 160 mg of yeast) were prepared with AT25, AT28, and S47 produced on molasses plates. The doughs were stored at −20°C, and the dough-rising capacity (gassing power) was measured after thawing of the doughs (Fig. 4). Both AT25 and AT28 maintained a better dough-rising capacity during frozen storage of the doughs for up to at least 45 days. The absolute gassing powers of AT28 and S47 after 1 day of frozen storage were similar, while that of AT25 was still 10% lower than that of S47 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Maintenance of gassing power in small doughs (20 g of flour and 160 mg of yeast) after freezing for different time periods at −20°C. The prefermentation time before freezing was 30 min. Gassing power after 1 day of frozen storage was taken as 100%. Absolute values for gassing power after 1 day of frozen storage (n = 3) were 120 ± 2.3 for S47, 106 ± 1.2 for AT25, and 107 ± 3.6 for AT28 (expressed in milliliters of CO2 produced in 2 h). •, S47; ○, AT25; ▴, AT28. The standard error never exceeds 10% of the absolute values.

AT25, AT28, and S47 were then produced on a pilot scale in a 20-liter fermentor. The yields for the three strains were comparable (results not shown), as were the phosphorus contents (Table 1). N assimilation was somewhat better for AT25 (Table 1). The gassing power of pilot-scale-produced AT25 cells was reproducibly about 10% higher than that of S47 (Table 2), in contrast to production in shake flasks or on molasses plates under laboratory conditions. The gassing power of pilot-scale-produced AT28 cells was 25 to 30% lower than that of S47, which made AT28 unsuitable for industrial use. These differences in gassing power between the strains were observed in both lean and sugar doughs (Table 2). Maintenance of gassing power during frozen storage was measured in doughs prepared with the three strains (Fig. 5). At both −3 and −30°C, the AT25 strain retained more fermentation capacity than S47, whereas AT28 was clearly worse than S47. The stability during microdrying was somewhat better for AT25 than for S47, whereas that for AT28 was somewhat worse (results not shown). Although resistance of AT25 against freeze and drought stress was enhanced, its shelf life was inferior to that of S47. AT28 showed a better retention of gassing power during storage, but its low fermentation activity in fresh doughs makes this result not very meaningful for commercial usage (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Dry mass and chemical composition of yeast produced on a pilot scale (20-liter fermentor)a

| Strain | Dry mass (%) | Nitrogen/dry mass (%) | Total phosphorus/dry mass (%) | Total carbohydrate/dry mass (%) | Trehalose/dry mass (%) | Total lipids/dry mass (%) | Phospholipids/dry mass (%) | Ergosterol/dry mass (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S47 | 31.7 | 7.3 | 2.6 | 39.8 | 15.3 | 2.87 | 1.40 | 0.44 |

| AT25 | 32.0 | 7.8 | 2.6 | 32.8 | 11.9 | 3.11 | 1.49 | 0.50 |

| AT28 | 33.4 | 6.7 | 2.6 | 45.3 | 17.9 | 3.51 | 1.16 | 0.41 |

The standard errors for four independent measurements are about 0.3 for percent dry mass, 0.1 for percent nitrogen, 0.09 for percent phosphorus, 1.0 for percent total carbohydrate, 0.5 for percent trehalose, 0.5 for percent total lipids, 0.15 for percent phospholipids, and 0.05 for percent ergosterol.

TABLE 2.

Gassing power in doughs (20 g of flour, 160 mg of yeast, and 15 ml of H2O) made with freshly produced yeast (20-liter fermentor) and with yeast that was stored on the shelf for 7 days

| Strain | Gassing power (ml of CO2)a in doughs made with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh yeast

|

Yeast stored at 26°C for 7 days

|

|||

| Lean doughs | Sugar doughsb | Lean doughs | Sugar doughs | |

| S47 | 137 | 84 | 90 | 29 |

| AT25 | 145 | 100 | 62 | 27 |

| AT28 | 96 | 71 | 71 | 40 |

The standard errors for four independent measurements are around 3.

Four grams of sucrose/dough.

FIG. 5.

Effect of long-term storage on gassing power of doughs made with yeast produced on a pilot scale (20-liter fermentor). Storage was at either −3 or −30°C. •, S47; ○, AT25; ▴, AT28. Standard errors (n = 3) vary between 7.5 and 37.5 ml of CO2.

The total carbohydrate content of the AT25 cells was about 20% less than that of S47 cells, which was for about 50% due to a reduction of the trehalose content from about 15% in S47 cells to about 12% in AT25 cells (Table 1). AT28 cells had about 15% more carbohydrate than S47 cells, which was almost entirely due to a higher trehalose content. Lipid analysis of the three strains revealed that the contents of total lipids, phospholipids, and ergosterol were very similar in the mutant and parental strains (Table 1). The phospholipid/ergosterol ratio was 10% higher in AT25 and AT28 than in S47. The compositions and saturation degrees of the fatty acids also were very similar in the three strains (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Fatty acid composition of yeast produced on a pilot scale (20-liter fermentor)

| Type of fatty acid | % of total fatty acid levela in strain:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S47 | AT25 | AT28 | |

| C12 | 0.24 | 0.18 | |

| C14 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| C16 | 8.71 | 9.06 | 10.66 |

| C16:1 | 29.60 | 30.85 | 27.41 |

| C18 | 3.62 | 5.02 | 5.50 |

| C18:1 | 46.58 | 46.26 | 45.35 |

| C18:2 | 7.60 | 5.27 | 6.86 |

| C18:3 | 2.61 | 1.81 | 2.47 |

| Unsaturated/total (%) | 86.4 | 84.3 | 82.2 |

| C16/C18 ratio | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.63 |

The standard errors are about 1.5% of the given values for four independent measurements.

Production on industrial scale.

For cells produced with the same rate of nitrogen feeding, the gassing power of industrial-scale-produced AT25 was consistently 10 to 15% higher than that of S47 (three batches were produced and tested). This difference also was maintained during frozen storage for up to 4 months (results not shown). All other industrially relevant parameters measured, i.e., yield, dry weight, nitrogen assimilation, and phosphorus content, were similar for AT25 and S47, and their performances in baking trials also were similar (results not shown).

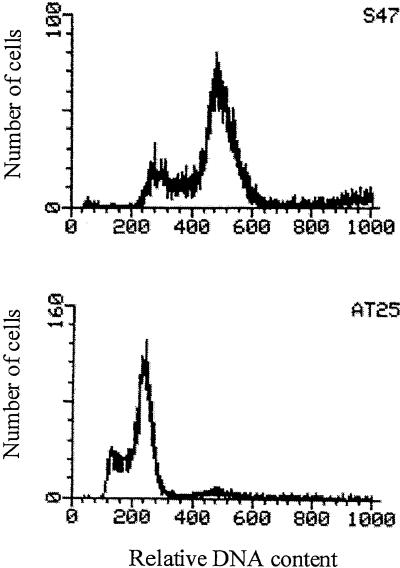

AT25 is a diploid strain.

Microscopic observations indicated a smaller cell size for AT25 than for S47 (results not shown). Subsequent determination of the DNA content by flow cytometry showed that the DNA content of AT25 was only about half of that of S47 (Fig. 6). Hence, AT25 appears to be a diploid derivative of the tetraploid S47 strain. The strain also showed relative good sporulation. AT28 also was diploid, but other stress-resistant mutants were tetraploid (results not shown).

FIG. 6.

Flow cytometric analysis of cellular DNA contents of S47 and AT25. The first peak represents cells in G1, and the second peak represents cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle.

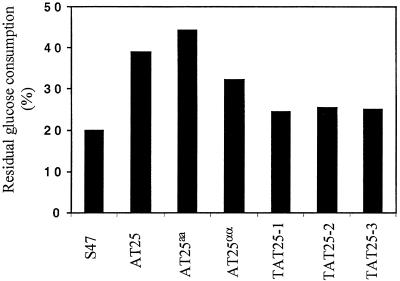

Tetraploidization of AT25.

The AT25 strain (MATa/α) was tetraploidized by using HO-induced mating type switch and mating of a MATa/a (AT25aa) and a MATα/α (AT25αα) strain (see Materials and Methods). The tetraploid strain was called TAT25 (a/a/α/α), and three independent isolates, TAT25-1, TAT25-2, and TAT25-3, were tested for freeze tolerance with the RGC test. The tetraploid strain S47 is a/a/a/α, since sporulation results in two MATa/a strains and two MATa/α strains per ascus (results not shown). The diploid strains AT25, AT25a/a, and AT25α/α were more freeze tolerant than S47. The freeze tolerances of the tetraploidized strains TAT25-1, -2, and -3 were lower than those of the diploid strains and only slightly higher than that of the tetraploid strain S47 (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Freeze stress resistance (determined as RGC after freezing) of tetraploidized AT25. After 30 min of fermentation in liquid medium, samples were frozen for 1 day at −30°C. The strains used were S47 (tetraploid parent, a/a/a/α); AT25 (diploid a/α derived from S47); AT25aa and AT25α/α (diploid strains derived from AT25 through mating type switch); TAT25-1, TAT25-2, and TAT25-3 (tetraploid strains [a/a/α/α] obtained by mating of AT25aa with AT25αα). A representative result is shown. Compared to S47, the RGC of AT25 is 1.85 ± 0.10 (n = 2) times higher, the RGC of AT25aa is 2.24 ± 0.02 (n = 2) times higher, the RGC of AT25α/α is 1.39 ± 0.23 (n = 2) times higher, and the RGCs of the three tetraploid strains together are 1.31 ± 0.07 (n = 5) times higher.

DISCUSSION

Selection of AT25.

In this work we have isolated fil-type mutants directly from commercial strains. This was achieved by combining UV mutagenesis with a selection procedure mimicking as closely as possible the industrial conditions under which the yeast has to show a better freeze resistance. In principle, selection of the mutants by long-term frozen storage of the doughs would have been more close to reality than the selection by multiple rounds of freeze-thawing, but the drop in viability of the yeast during frozen storage is too small to make this a practical screening protocol.

After about 200 rounds of freezing and thawing, just a few surviving cells were recovered. Many of these showed a low growth rate. It is known that in yeast low growth rates often result in cells with higher stress resistance (7, 20, 23, 24). Whether the higher freeze tolerance of these mutants is an indirect effect of their low growth rate or whether both are a direct consequence of the mutation is unknown. However, for industrial production of baker's yeast, rapid cell proliferation is an essential property, and therefore among the surviving mutants, only strains with a normal growth rate compared to the parent strain were selected for further characterization.

Origin of AT25.

For practical reasons the small doughs used for the selection of the mutants were not prepared under sterile conditions. Hence, AT25 might have been a natural yeast contaminant of the dough that was selected with the freeze-thaw procedure among the commercial nontolerant yeast cells. However, the chemical composition of AT25 and its behavior during and after production on pilot and industrial scales are so similar to those of S47 that it is very unlikely that AT25 would not be a derivative of the commercial strain S47 used in the mutagenesis procedure.

The parent strain S47 is a polyploid and aneuploid strain (approximately tetraploid), and there is no further information on its precise genetic composition. Analysis of the DNA content of AT25 by flow cytometry revealed that it was only half that of S47; this is approximately diploid. AT25 may have lost chromosomes during the UV mutagenesis procedure, resulting in a lower DNA content. A similar situation might be true for AT28. Control experiments indicated that UV mutagenesis of S47 resulted in many strains with a reduced DNA content (unpublished results). On the other hand, we also observed occasional spontaneous ascospore formation in normal cultures of the S47 strain. However, other resistant mutants isolated were tetraploid. AT25 and AT28 may have originated from a spontaneously formed spore of S47. Control experiments indicated that meiotic segregants derived from S47 showed a wide range of stress resistance; for some strains the stress resistance was even higher than that for AT25 (but the fermentation capacity was much lower). The diploid nature of AT25 and AT28 could have been a positive factor in the selection procedure, since the isogenic tetraploid TAT25 strain was significantly less resistant than AT25. In principle, it cannot be excluded that the chromosome loss and resulting different gene expression pattern is not the only genetic change responsible for the higher stress tolerance of AT25. One or more UV-induced mutations might still be present, irrespective of whether the strain originated from an ascospore or not.

Properties of AT25 and determinants of stress resistance.

The lipid contents and compositions of S47, AT25, and AT28 were very similar, indicating first that lipid content and composition are not responsible for the differences in freeze tolerance and second that a change in lipid content and composition is not required to enhance freeze tolerance, at least not to the extent observed in AT25. Murakami et al. (21) reported similar lipid contents and compositions for freeze-tolerant and freeze-sensitive industrial baker's yeast strains. However, they also mentioned that the molar ratio of sterol to phospholipid of freeze-sensitive strains was higher than that of freeze-tolerant strains. In our case this ratio was also somewhat elevated in the freeze-sensitive strain S47 compared to the two freeze-tolerant strains AT25 and AT28 (Table 1), but it appears rather unlikely that this relatively small change of 10% would be (solely) responsible for the higher stress resistance of the two strains.

The observation that the trehalose content of strain AT25 was about 20% lower than that of the parent strain S47 was highly unexpected. Several reports have shown a close correlation between trehalose content and resistance to various stress conditions in yeast (8, 11). On the other hand, our previous work on the rapid loss of heat resistance during the initiation of fermentation in yeast has shown that under these conditions, a high trehalose content is not sufficient to prevent or even to partially counteract the rapid loss of stress resistance (31). Hence, the lower trehalose content of the AT25 strain constitutes a new argument that other powerful determinants of stress tolerance in yeast besides the trehalose content must exist. This conclusion is further substantiated by the observation that AT28 had 17% more trehalose than S47, whereas its freeze tolerance was clearly lower. On the other hand, it is possible that the different strains mobilize trehalose at different rates and therefore that the trehalose content at the moment of freezing would still be important for freeze resistance.

A remarkable finding with respect to the phenotype of AT25 was the lower initial fermentation capacity (without freezing treatment) when the cells were produced under laboratory conditions compared to pilot-scale conditions. For cells produced under laboratory conditions the fermentation capacity of AT25 was consistently lower than that of S47, while for cells produced under pilot-scale and industrial-scale conditions it was consistently higher. By optimizing the feeding conditions, it might be possible to further improve the fermentation capacity of AT25. This observation shows that at least in some cases a yeast strain can show a better performance under industrial conditions than what would have been expected from its characterization under laboratory conditions. Apparently, sometimes the industrial growth conditions can improve the behavior of a strain dramatically so that it switches from promising to superior performance. On the other hand, production under pilot-scale conditions can be performed for only a very limited number of strains because of the expense involved.

Since some of the selected freeze-tolerant strains were diploid, lower ploidy might be associated with higher stress tolerance, at least during the initiation of fermentation. The tetraploid TAT25 strains derived from AT25 did not show the elevated freeze tolerance of AT25. Their freeze tolerance level was only slightly higher than that of the tetraploid S47 strain. This appears to confirm this inverse correlation.

Diploid industrial baker's yeast strains.

A remarkable outcome of the present work is that the strain with the best behavior for freeze tolerance and other commercially important properties had only a diploid DNA content compared to its parent tetraploid strain. This diploid strain had a better initial fermentation capacity than the parent strain after production under industrial conditions, and it behaved as well as the parent strain in industrial production and usage, clearly indicating that tetraploidy is not essential for optimal baker's yeast performance.

Genetic modification of tetraploid industrial yeast strains by recombinant DNA technology is very cumbersome. Complicated approaches have been devised to construct genetically modified tetraploid strains (16). The present finding that a diploid derivative of a tetraploid industrial baker's yeast strain can show at least the same performance in industrial production and usage as its tetraploid parent might greatly facilitate improvement of baker's yeast strains in the future by recombinant DNA methodology. Especially, the introduction of deletions and specific point mutations would become much easier than with the currently used tetraploid strains.

Production on pilot and industrial scales.

On a pilot scale, AT25 showed characteristics of yield, nitrogen assimilation, and other commercially important properties that were comparable to those of S47. After production on industrial scale in a fermentor of 20,000 liters, the AT25 yeast showed the same characteristics as when produced on pilot scale in a fermentor of 20 liters. Baking trials also gave satisfactory results. Hence, these results show that the sequence of mutagenesis of a commercial yeast strain, selection under conditions mimicking the industrial conditions, and characterization under laboratory and subsequently industrial conditions can result in novel strains with the desired superior property sought. In spite of its smaller size compared to the parent strain S47 and other commercial yeast strains, production and in particular filtration of the yeast during industrial production did not cause problems. Hence, the AT25 strain appears to be promising for use in the industrial production of frozen doughs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Renata Wicik and Willy Verheyden for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Institute for Scientific and Technological Research (IWT) to An Tanghe and by grants from the Flemish Ministry of Economy through the Institute for Scientific and Technological Research (EUREKA/1431-IWT/950170 and IWT990098), the Flemish Interuniversity Institute of Biotechnology (VIB/PRJ2), and the Research Fund of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Concerted Research Actions) to J.M.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society of Brewing Chemists. 1987. Methods of analysis of the American Society of Brewing Chemists. American Society of Brewing Chemists, St. Paul, Minn.

- 2.Attfield, P. V. 1997. Stress tolerance: the key to effective strains of industrial baker's yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:1351-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brin, M. 1966. Transketolase clinical aspects. Methods Enzymol. 9:506-514. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrows, S., and J. S. Harrison. 1959. Routine method for determination of the activity of baker's yeast. J. Inst. Brew. 65:39-45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clément, P., and A. Loïez. August1983. Strains of yeast for bread-making and novel strains of yeast thus prepared. U.S. patent 4,396,632.

- 6.Colavizza, D., F. Dumortier, M. F. Gorwa, K. Lemaire, A. Loïez, A. Teunissen, J. Thevelein, P. Van Dijck, and M. Versele. December1999. New stress resistant eukaryotic strains in fermentation and/or growth phase, useful for production of frozen dough and alcoholic drinks. European patent EP9940 1444.

- 7.Elliott, B., and B. Futcher. 1993. Stress resistance of yeast cells is largely independent of cell cycle phase. Yeast 9:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gélinas, P., G. Fiset, A. LeDuy, and J. Goulet. 1989. Effect of growth conditions and trehalose content on cryotolerance of baker's yeast in frozen doughs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:2453-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Güldener, U., S. Heck, T. Fiedler, J. Beinhauer, and J. H. Hegemann. 1996. A new efficient gene disruption cassette for repeated use in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:2519-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison, J. S., and W. E. Trevelyan. 1963. Phospholipid breakdown in baker's yeast during drying. Nature 200:1189-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hino, A., K. Mihara, K. Nakashima, and H. Takano. 1990. Trehalose levels and survival ratio of freeze-tolerant versus freeze-sensitive yeasts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1386-1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hino, A., H. Takano, and Y. Tanaka. 1987. New freeze-tolerant yeast for frozen dough preparations. Cereal Chem. 64:269-275. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu, K. H., R. C. Hoseney, and P. A. Seib. 1979. Frozen dough. I. Factors affecting stability of yeasted doughs. Cereal Chem. 56:419-424. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu, K. H., R. C. Hoseney, and P. A. Seib. 1979. Frozen dough. II. Effects of freezing and storing conditions on the stability of yeasted doughs. Cereal Chem. 56:424-426. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, J., P. Alizadeh, T. Harding, A. Hefnergravink, and D. J. Klionsky. 1996. Disruption of the yeast ATH1 gene confers better survival after dehydration, freezing, and ethanol shock: potential commercial applications. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1563-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein, C. J. L., L. Olsson, B. Ronnow, J. D. Mikkelsen, and J. Nielsen. 1996. Alleviation of glucose repression of maltose metabolism by MIG1 disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4441-4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kline, L., and T. F. Sugihara. 1968. Factors affecting the stability of frozen bread doughs. I. Prepared by the straight dough method. Bakers Digest 42:44-69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorenz, K. 1974. Frozen dough-present trend and future outlook. Bakers Digest 48:14-22,30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto, K., I. Uno, and T. Ishikawa. 1985. Genetic analysis of the role of cAMP in yeast. Yeast 1:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchel, R. E. J., and D. P. Morrison. 1982. Heat-shock induction of ionising radiation resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and correlation with stationary growth phase. Radiat. Res. 90:284-291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami, Y., K. Yokoigawa, F. Kawai, and H. Kawai. 1996. Lipid composition of commercial bakers' yeasts having different freeze-tolerance in frozen dough. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 60:1874-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oda, Y., K. Uno, and S. Ohta. 1986. Selection of yeasts for breadmaking by the frozen dough method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 52:941-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park, J. I., C. M. Grant, P. V. Attfield, and I. W. Dawes. 1997. The freeze-thaw stress response of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is growth phase specific and is controlled by nutritional state via the RAS-cyclic AMP signal. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3818-3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plesset, J., J. Ludwig, B. Cox, and C. McLaughlin. 1987. Effect of cell cycle position on thermotolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 169:779-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popolo, L., M. Vanoni, and L. Alberghina. 1982. Control of the yeast cell cycle by protein synthesis. Exp. Cell Res. 142:69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed, G., and T. W. Nagodawithana. 1991. Yeast technology, p. 292-295. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, N.Y.

- 27.Takagi, H., F. Iwamoto, and S. Nakamori. 1997. Isolation of freeze-tolerant laboratory strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae from proline-analogue-resistant mutants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47:405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thevelein, J. M., L. Cauwenberg, S. Colombo, J. H. de Winde, M. Donaton, F. Dumortier, L. Kraakman, K. Lemaire, P. Ma, D. Nauwelaers, F. Rolland, A. Teunissen, P. Van Dijck, M. Versele, S. Wera, and J. Winderickx. 2000. Nutrient-induced signal transduction through the protein kinase A pathway and its role in the control of metabolism, stress resistance and growth in yeast. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 26:819-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thevelein, J. M., and J. H. de Winde. 1999. Novel sensing mechanisms and targets for the cAMP-protein kinase A pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1002-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trevelyan, W. E., and J. S. Harrison. 1956. Studies on yeast metabolism. VII. Yeast carbohydrate fractions. Separation from nucleic acid, analysis and behaviour during anaerobic fermentation. Biochem. J. 63:23-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Dijck, P., D. Colavizza, P. Smet, and J. M. Thevelein. 1995. Differential importance of trehalose in stress resistance in fermenting and nonfermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:109-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dijck, P., P. Ma, M. Versele, M.-F. Gorwa, S. Colombo, K. Lemaire, D. Bossi, A. Loïez, and J. M. Thevelein. 2000. A baker's yeast mutant (fil1) with a specific, partially inactivating mutation in adenylate cyclase maintains a high stress resistance during active fermentation and growth. J. Mol. Microbiol Biotechnol. 2:521-530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiemken, A. 1990. Trehalose in yeast, stress protectant rather than reserve carbohydrate. Antonie Leeuwenhoek J. Microbiol. 58:209-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]