Abstract

Background

Protoplasts are a valuable tool for studying gene expression and applying genome editing techniques. Given the high medicinal and industrial potential of Cannabis sativa L., developing an efficient protoplast-to-plant regeneration protocol is highly desirable. Due to its recalcitrant nature, a complete plant regeneration from cannabis protoplasts has not yet been achieved.

Results

This study details a robust protocol for cannabis protoplast isolation, purification, transient transfection, and culture, additionally reporting somatic embryo-like structures derived from protoplast-derived callus. We demonstrated that the age of donor material, the composition of the enzyme solution, and the duration of enzymolysis are crucial for efficient protoplast isolation. Protoplast embedding, coupled with a rich culture medium and plant growth regulators, proved critical for initiating cell wall re-synthesis, cell division, and microcallus formation. Protoplasts isolated using the reported protocol were abundant (2.2 × 106 protoplasts/1 g of fresh weight), viable (78.8% viability) and able to undergo cell wall re-synthesis (56.1% of viable cells), followed by cell divisions (15.8% plating efficiency). Polyethylene glycol-mediated transfection yielded a 28% transfection efficiency and 17% plating efficiency in 10-day cultures. Protoplast-derived microcalli successfully proliferated on six regeneration media containing various concentrations of 6-benzylaminopurine and thidiazuron, exhibiting further proliferation and greening within two months.

Conclusions

This system provides a reliable protocol for isolation, transfection and culture of cannabis protoplasts. It also offers a framework for investigating gene function, as well as advancing protoplast fusion and genome editing technologies for this species.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-07686-1.

Keywords: Hemp, Protoplast embedding, Tissue cultures, Phytosulfokine, 2-aminoindane-2-phosphonic acid

Background

Cannabis sativa L., a dioecious annual herb of the Cannabaceae family, is an important medicinal and industrial crop, valued for its fibers in textiles, seeds for nutrition, and secondary metabolites for medicinal or recreational applications. Hemp offers a versatile, cost-effective, abundant, and renewable raw material with distinct chemical and physical properties. The global industrial hemp market, estimated at $5.49 billion in 2023 in Grand View Research Market Analysis Report [1], is expanding as more countries relax cultivation and sales restrictions, necessitating a deeper understanding of this crop.

The development of New Plant Breeding Technologies (NPBT), stemming from CRISPR/Cas9, can benefit cannabis by enabling targeted genetic modifications. These advancements can enhance desirable traits, introduce novel characteristics, and optimize this important industrial and medicinal crop. Applying NPBTs to cannabis may improve yield, modify cannabinoid profiles, increase stress resistance, and facilitate the creation of novel cultivars or lines for specific applications. As the regulatory environment for cannabis evolves, integrating these cutting-edge breeding techniques will be vital for realizing the full potential of this species [2].

Protoplasts are a valuable experimental system in plant biotechnology, facilitating genetic transformation, gene expression studies, and genome editing [3], including DNA-free CRISPR applications for targeted mutagenesis and whole plant regeneration without plasmid integration into the host genome [4–6]. Evaluating the effectiveness of CRISPR/Cas is a crucial step in leveraging this technology for crop trait improvement [7]. Transient transformation of protoplasts provides a rapid and efficient system to assess the rate of construct uptake and the performance and specificity of nucleases and sgRNAs.

Since the first report of protoplast isolation from cannabis mesophyll, published by Morimoto et al. [8], several other protocols for improved protoplast isolation were proposed [9–13]. Yet, most of them focus solely on protoplast isolation and transient transformation, with little effort placed on protoplast culture and plant regeneration. Thus, reports of long-term effects of PEG-mediated transformation on cannabis protoplast viability, ability to re-synthesize the cell wall, and to undergo first mitotic divisions are lacking. So far, only two reports of protoplast cultures have been provided [12, 14]. Monthony and Jones [12] made a fundamental step in establishing a protoplast-to-plant regeneration system, marking the first report of early cell division in cannabis protoplasts and the formation of microcallus in three-week-old cultures, but no further growth or development was observed. These results provide a valuable starting point for overcoming the challenges associated with cannabis regeneration, which still remains elusive. Given the highly heterozygous nature of cannabis, a genotype-dependent response to protoplast cultures is anticipated. In their study, Kral et al. [14] explored the genotype-dependency of protoplast cultures in greater depth, as they included two hemp cultivars in experiments focused on the effect of the composition of enzyme mixture, and the type and age of donor material on the efficiency of protoplastization. The yield of protoplasts obtained from 6-month-old in vitro cultured plants differed between tested cultivars. The authors reported the second successful cultivation of cannabis protoplasts exhibiting cell divisions within the first 14 days of culture. These preliminary results suggest the potential for developing a universal and robust protocol for protoplast-to-plant regeneration applicable across various genotypes.

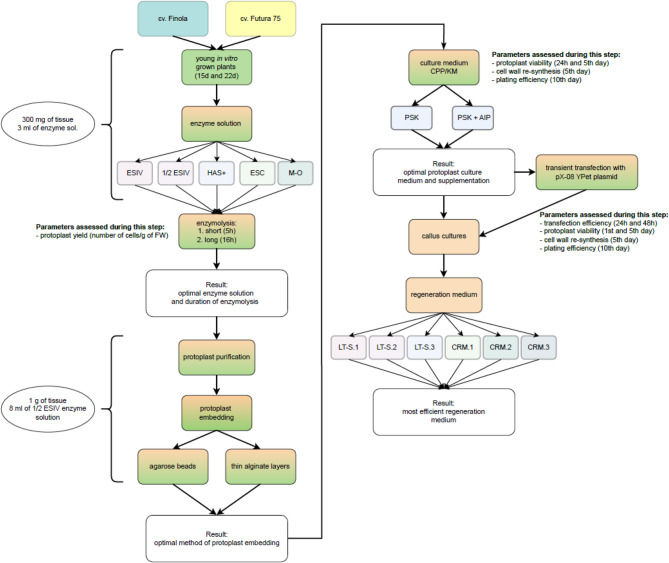

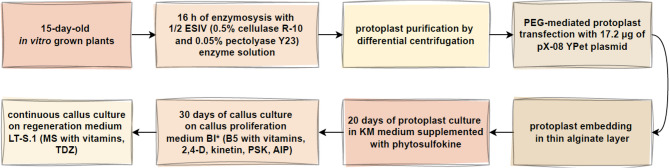

Here, key factors contributing to successful and efficient protoplast isolation and culture were optimized (Fig. 1). This involved the selection of an appropriate age of donor tissue, as well as adjustments to the composition of enzyme solution, duration of enzymolysis, the most efficient embedding technique, and protoplast culture medium. Additionally, an efficient protocol for transient transfection of cannabis protoplasts was developed, thereby offering a promising tool for gene function studies and genetic improvement.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart illustrating a step-by-step approach to develop a protocol for protoplast isolation, purification, culture and regeneration in Cannabis sativa L. Details and used abbreviations are explained in the Materials and methods section and Table 1

Materials and methods

Plant material

All research was performed under a hemp research permit (MKW/WPIS/PROD/KR/2024/00028) issued through the National Support Centre for Agriculture (KOWR), Poland for seed batches: 1108–22,168 and F1545 M147515. As a protoplast source, two cultivars of Cannabis sativa L., ‘Finola’ (seed batch: 1108–22168; The Hemp Company LLC, Radzymin, Poland, producer ID: 14/34/21375) and ‘Futura 75’ (seed batch: F1545 M147515; The Hemp Company LLC, Radzymin, Poland, producer ID: 14/34/21375), were used. Seeds were sterilized as follows: first, seeds were incubated in a distilled water bath at 40 °C for 30 min, then transferred to a 0.2% (v/v) solution of fungicide ‘Bravo’ (Syngenta, Waterford, Ireland) and placed on a gyratory shaker (180 rpm) for 30 min. Next, the seeds were immersed in a 20% (w/v) solution of chloramin T (Chempur, Poland) for 30 min. After each step, the seeds were rinsed in 70% ethanol for 30 s. After three washes with sterile distilled water (for 5 min each), the seeds were air-dried on a sterile filter paper in a laminar airflow cabinet (LHAC – H120, Alpina, Poland). Seeds were transferred into 9 cm Petri dishes with solid germination medium (MS30; Table 1) and maintained at 24 ± 2 °C in the dark. After three days, germinated seedlings were placed in sterile 500 ml plastic culture vessels (Pakler Lerka, Poland) containing approximately 60 ml of MS30 medium, and maintained at 24 ± 2 °C with a 18/6 h (light/dark) photoperiod and a light intensity of 200 µmol m− 2 s− 1 (LED FITO PANEL 90 DW + FR, Biogenet, Poland).

Table 1.

Solutions and media used for the preparation of donor material, protoplast isolation, transfection and culture, callus culture and plant regeneration of Cannabis sativa

| Solution/ medium name | Solution/ medium composition | Application | Storage conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| MS30 | MS micro- and macroelements including vitamins [15] (Duchefa Biochemie, The Netherlands), 30 g l− 1 sucrose (POCH, Poland), 0.6% (w/v) plant agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.8; autoclaved | seed germination and donor plant growth | room temperature (RT) |

| PSII [16] | 0.5 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.6; autoclaved | plasmolysis | RT |

| enzyme solution ESC [17] with modifications | 0.5% (w/v) cellulase Onozuka R-10 (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.1% (w/v) pectolyase Y-23 (Duchefa Biochemie), 5 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES; Sigma-Merck), 25 mM calcium chloride (POCH), 0.4 M mannitol (Sigma-Merck); pH 5.8; filtered (0.22 μm membrane; Millex®-GP, Millipore, Merck) | enzymolysis |

4 °C, dark stored up to one month |

| enzyme solution ESIV [16] with modifications | 1% (w/v) cellulase Onozuka R-10 (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.1% (w/v) pectolyase Y-23 (Duchefa Biochemie), 20 mM MES (Sigma - Merck), 5 mM magnesium chloride hexahydrate (POCH), 0.4 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.6; filtered (0.22 μm membrane; Millex®-GP, Millipore, Merck) | enzymolysis |

4 °C, dark stored up to one month |

|

enzyme solution ½ ESIV |

0.5% (w/v) cellulase Onozuka R-10 (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.05% (w/v) pectolyase Y-23 (Duchefa Biochemie), 20 mM MES (Sigma - Merck), 5 mM magnesium chloride hexahydrate (POCH), 0.5 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.6; filtered (0.22 μm membrane; Millex®-GP, Millipore, Merck) | enzymolysis |

4 °C, dark stored up to one month |

| enzyme solution HAS | 2% (w/v) cellulase Onozuka R-10 (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.2% (w/v) pectolyase Y-23 (Duchefa Biochemie), 5 mM MES (Sigma - Merck), 5 mM magnesium chloride hexahydrate (POCH), 0.01% (w/v) N-Z-amine (Sigma - Merck), 0.55 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.8; filtered (0.22 μm membrane; Millex®-GP, Millipore, Merck) | enzymolysis |

4 °C, dark stored up to one month |

| enzyme solution M-O [11] | 2.5% (w/v) cellulase Onozuka R-10 (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.3% (w/v) macerozyme R-10 (Duchefa Biochemie), 20 mM MES (Sigma - Merck), 10 mM calcium chloride (POCH), 20 mM potassium chloride (POCH); 0.7 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.7; filtered (0.22 μm membrane; Millex®-GP, Millipore, Merck) | enzymolysis |

4 °C, dark stored up to one month |

| sucrose/MES [16] | 0.5 M sucrose (POCH), 1 mM MES (Sigma-Merck); pH 5.8; autoclaved | protoplast separation and purification | RT |

| W5 [18] | 154 mM sodium chloride (POCH), 125 mM calcium chloride dihydrate (POCH), 5 mM potassium chloride (POCH), 5 mM glucose (POCH); pH 5.8; autoclaved | protoplast purification | RT |

| CPP [16] | macro- and microelements according to Kao and Michayluk [19] (Duchefa Biochemie), vitamins according to Gamborg B5 medium [20], 20 mg l− 1 sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Merck), 40 mg l− 1 citric acid (Sigma-Merck), 40 mg l− 1 malic acid (Sigma-Merck), 40 mg l− 1 fumaric acid (Sigma-Merck), 0.4 M glucose (POCH), 250 mg l− 1 N-Z-amine (Sigma - Merck), 0.1 mg l− 1 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D; Sigma - Merck), and 0.2 mg l− 1 zeatin (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.6; filtered (0.22 μm membrane; Sterivex-GP, Millipore, Merck) | protoplast culture | 4 °C, dark |

| KM [19] with modifications | macro- and microelements according to Kao and Michayluk [19] (Duchefa Biochemie), 100 mg l− 1 myo-inositol (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.01 mg l− 1 retinyl acetate (Sigma - Merck), 1 mg l− 1 thiamine (Sigma - Merck), 0.2 mg l− 1 riboflavin (Sigma - Merck), 1 mg l− 1 nicotinamide (Sigma - Merck), 1 mg l− 1 D-calcium pantothenate (Duchefa Biochemie), 1 mg l− 1 pyridoxine (Sigma - Merck), 0.01 mg l− 1 biotin (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.4 mg l− 1 folic acid (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.02 mg l− 1 cyanocobalamin (Sigma - Merck), 2 mg l− 1 ascorbic acid (Duchefa Biochemie), 0.01 mg l− 1 cholecalciferol, 20 mg l− 1 sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Merck), 40 mg l− 1 citric acid (Sigma-Merck), 40 mg l− 1 malic acid (Sigma-Merck), 40 mg l− 1 fumaric acid (Sigma-Merck), 1 mg l− 1 choline chloride (Sigma - Merck), 0.02 mg l− 1 p-aminobenzoic acid (Sigma - Merck), 68.4 g l− 1 glucose (POCH), 250 mg l− 1 sucrose (POCH), 250 mg l− 1 fructose (Duchefa Biochemie), 250 mg l− 1 ribose (Duchefa Biochemie), 250 mg l− 1 xylose (Duchefa Biochemie), 250 mg l− 1 mannose (Duchefa Biochemie), 250 mg l− 1 rhamnose (Duchefa Biochemie), 250 mg l− 1 cellobiose (Sigma - Merck), 250 mg l− 1 sorbitol (POCH), 250 mg l− 1 mannitol (Sigma - Merck), 0.6 mg l− 1 L-Alanine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Arginine-HCl, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Asparagine, 0.1 mg l− 1 Aspartic acid, 0.2 mg l− 1 L-Cysteine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Cystine, 0.6 mg l− 1 L-Glutamic acid, 5.6 mg l− 1 L-Glutamine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Glycine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Histidine hydrochloride, 0.1 mg l− 1 4-Hydroxyproline, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Isoleucine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Leucine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-lysine hydrochloride, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Methionine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Phenylalanine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Proline, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Serine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Threonine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Tryptophan, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Tyrosine, 0.1 mg l− 1 L-Valine (all amino acids provided by Sigma - Merck), 0.1 mg l− 1 adenine (Sigma - Merck), 0.3 mg l− 1 guanine (Sigma - Merck), 0.3 mg l− 1 thymine (Sigma - Merck), 0.3 mg l− 1 uracil (Sigma - Merck), 0.015 mg l− 1 hypoxanthine (Sigma - Merck), 0.03 mg l− 1 xanthine (Sigma - Merck), 0.1 mg l− 1 2,4-D (Sigma - Merck), 1 mg l− 1 NAA (Sigma - Merck), 0.2 mg l− 1 zeatin (Sigma - Merck), 250 mg l− 1 N-Z-amine (Sigma - Merck), 20 ml coconut water (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.6; filtered (0.22 μm membrane; Sterivex-GP, Millipore, Merck) | protoplast culture | 4 °C, dark |

| sodium alginate solution [16] | 0.4 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck), 2.8% (w/v) alginic acid sodium salt (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.8; filtered (0.22 μm membrane, Millex®-GP, Millipore, Merck) | protoplast embedding | RT |

| Ca-agar medium [16] | 40 mM calcium chloride (POCH), 0.4 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck), 0.6% (w/v) agar plant agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.8; autoclaved | alginate gelation | RT |

| agarose | 1.2% (w/v) agarose SeaPlaque (Duchefa Biochemie) dissolved in protoplast culture medium; pH 5.8; autoclaved | protoplast embedding | RT |

| MMG | 0.4 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck), 4 mM MES (Sigma – Merck), 15 mM MgCl2 (Sigma – Merck); pH 5.7; autoclaved | pre-transfection buffer | RT |

| PEG solution | 0.2 M mannitol (Sigma - Merck), 100 mM CaCl2∙ H2O (Sigma - Merck), 40% PEG 4000 (Sigma - Merck); pH 5.7; filtered (0.22 μm membrane, Millex®-GP, Millipore, Merck) | transfection solution | RT |

| BI* | Gamborg B5 micro- and macroelments with vitamins [20] (Duchefa Biochemie), 30 g l− 1 sucrose (POCH), 1 mg l− 1 2,4-D (Sigma - Merck), 0.022 mg l− 1 kinetin (Duchefa Biochemie), 100 nM phytosulfokine (PSK; NovoPro, PRC)*, 12.5 mg l− 1 2-aminoindane-2-phosphonic acid (AIP; AmBeed, USA)*, 0.6% (w/v) plant agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.8, autoclaved | protoplast-derived callus proliferation and culture | RT, *PSK and AIP added after sterilization |

| LT-S.1 [21] | MS micro- and macroelements including vitamins [15] (Duchefa Biochemie), 30 g l− 1 sucrose (POCH), 0.11 mg l− 1 thidiazuron (TDZ; Sigma - Merck)*, 0.6% (w/v) plant agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.7, autoclaved | callus culture and shoot regeneration | RT, *TDZ added after sterilization |

| LT-S.2 | MS micro- and macroelements including vitamins [15] (Duchefa Biochemie), 30 g l− 1 sucrose (POCH), 0.5 mg l− 1 TDZ (Sigma - Merck)*, 0.6% (w/v) plant agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.7, autoclaved | callus culture and shoot regeneration | RT, *TDZ added after sterilization |

| LT-S.3 | MS micro- and macroelements including vitamins [15] (Duchefa Biochemie), 20 g l− 1 sucrose (POCH), 15 g l− 1 banana powder (Sigma - Merck), 0.5 mg l− 1 TDZ (Sigma - Merck)*, 0.6% (w/v) plant agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.7, autoclaved | callus culture and shoot regeneration | RT, *TDZ added after sterilization |

| CRM.1 | MS micro- and macroelements including vitamins [15] (Duchefa Biochemie), 30 g l− 1 sucrose (POCH), 1 mg l− 1 6-(γ,γ-dimethylallylamino)purine (2iP; Sigma - Merck), 0.6% (w/v) plant agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.7, autoclaved | callus culture and shoot regeneration | RT |

| CRM.2 | MS micro- and macroelements including vitamins [15] (Duchefa Biochemie), 20 g l− 1 sucrose (POCH), 15 g l− 1 banana powder (Sigma - Merck), 1 mg l− 1 2iP (Sigma - Merck), 0.6% (w/v) plant agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.7, autoclaved | callus culture and shoot regeneration | RT |

| CRM.3 | MS micro- and macroelements including vitamins [15] (Duchefa Biochemie), 20 g l− 1 sucrose (POCH), 15 g l− 1 banana powder (Sigma - Merck), 0.1 mg l− 1 2,4-D (Sigma - Merck), 0.5 mg l− 1 2iP (Sigma - Merck), 0.11 mg l− 1 TDZ (Sigma - Merck)*, 0.6% (w/v) Plant Agar (Duchefa Biochemie); pH 5.7, autoclaved | callus culture and shoot regeneration | RT, *TDZ added after sterilization |

Protoplast isolation and culture

Optimization of protoplast isolation

The efficiency of enzymolysis was assessed on leaves from 15- and 22-day-old plants (Fig. 1; Additional file 1: Fig. S1) of two cannabis cultivars germinated from seeds in vitro. Four enzyme solutions containing different concentrations of cellulase Onozuka R-10 (from 0.5% to 2.5%) and pectolyase Y-23 (from 0.05% to 0.3%), i.e., ESIV, ½ ESIV, ESC, and HAS (Table 1), were tested. Additionally, we tested another enzyme solution containing cellulase Onozuka R-10 and macerozyme R-10 (M-O; Table 1), reported to yield high numbers of protoplasts from leaves of C. sativa [11]. The tested enzyme solutions were selected based on different concentrations of cellulase and pectolyase, as well as to compare the effectiveness of pectolyase Y-23 vs. macerozyme R-10. For each enzyme solution, two treatments were tested: (1) a short enzymolysis for 5 h with the last two hours using gentle shaking (35 rpm; Rotamax 120 Heidolph Instruments, Germany) at 26 °C; and (2) a long enzymolysis for 16 h with the last hour using gentle shaking (35 rpm; Rotamax 120 Heidolph Instruments) at 26 °C. For each digestion, 300 mg of plant material was used. Leaves and petioles were harvested and placed on a 60 × 15 mm glass Petri dish with 4 ml of PSII solution (Table 1), immediately cut with two scalpels into fine pieces (approximately 0.5 × 0.5 mm), and incubated for 1 h in the dark at 26 °C (40 rpm; Rotamax 120 Heidolph Instruments). Then, PSII was replaced with 3 ml of enzyme solution and subjected either to short or long enzymolysis. The released protoplasts were separated from undigested tissue by filtration through a 100 μm nylon sieve (Millipore, Merck, Germany) and centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min (MPW-223e, MPW Med Instruments, Poland; rotor type: MPW no 12,485). The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 7 ml of sucrose/MES solution (Table 1), slowly overlaid with 2 ml of W5 solution (Table 1), and centrifuged at 145 × g for 10 min. The protoplasts (Additional file 1: Fig. S4) were collected and suspended in 8 ml of W5 solution followed by centrifugation at 100 × g for 5 min. After the wash, protoplast yield was determined by cell counting using a Fuchs Rosenthal hemocytometer (Heinz Herenz, Germany).

Optimization of protoplast culture conditions

Isolation and purification of protoplasts was conducted as described above. Protoplasts were isolated from 15-day-old leaves and petioles of in vitro grown plants of ‘Finola’ and ‘Futura 75’. As yielding the highest number of protoplasts, ½ ESIV solution was used for long enzymolysis. The working density was adjusted to 8 × 105 protoplasts per ml of culture medium. For embedding the protoplasts in agarose, equal volumes of protoplast suspension and low melting agarose (Table 1) at 37 °C were mixed, and aliquots of 125 µl were immediately transferred into 60 × 15 mm Petri dishes (Falcon® 60 mm TC-treated Cell Culture Dish, Corning, NY, USA), forming three droplets per dish. After a 30-minute incubation at RT, solidified agarose droplets were covered by 4 ml of the CPP or KM culture medium (Table 1). Embedding in alginate was performed as described in Grzebelus et al. [16]. Briefly, an equal volume of filter-sterilized alginate solution (Table 1) and protoplast suspension at working density were gently mixed. Alginate layers were obtained by spreading 125 µl of protoplast-alginate suspension on the surface of the Petri dish containing Ca-agar medium (Table 1). After 1-hour incubation, thin alginate layers were gently transferred into 60 × 15 mm Petri dishes containing 4 ml of either the CPP or KM culture medium (Table 1). Additionally, four variants of CPP and KM media were used: (1) CPP supplemented with 100 nM phytosulfokine-α (PSK; NovoPro, PRC; CPP + PSK), (2) CPP supplemented with 100 nM of PSK and 0.04 mg of 2-aminoindane-2-phosphonic acid (AIP; Ambeed, USA; CPP + PSK + AIP), (3) KM supplemented with 100 nM PSK (KM + PSK), and (4) KM supplemented with 100 nM PSK and 0.04 mg of AIP (KM + PSK + AIP). AIP was added on the 5th day of protoplast culture. To maintain aseptic conditions of the cultures, 4 µl of cefotaxime (conc. 200 mg/ml; Duchefa Biochemie) was added to all media. Cultures were incubated at 26 °C in the dark. After 10 days of incubation, cultures were refreshed by removing the old medium and replacing it with 4 ml of either CPP or KM medium with reduced osmotic pressure (0.2 M of glucose). All supplements were added in the same concentrations.

Establishment and validation of a protocol for protoplast isolation and culture

Protoplasts were isolated from plantlets as described above, with some modifications: (1) one gram of tissue was subjected to plasmolysis in 8 ml of PSII solution in a 90 × 15 mm Petri dish; (2) 8 ml of ½ESIV enzyme solution was used for long enzymolysis; (3) the pellet of protoplasts was resuspended in 8 ml of sucrose/MES solution; (4) an additional wash (100 × g, 5 min) in 8 ml of the KM medium was performed immediately after the W5 wash, then protoplasts were counted. Protoplasts were then embedded in alginate as described in Grzebelus et al. [16]. Cultures were established as described above with one medium variant: 4 ml of the KM medium, supplemented with 100 nM of PSK and 4 µl of cefotaxime (conc. 200 mg/ml).

Plant regeneration

After 20 days of protoplast culture, the development of protoplast-derived microcallus was assessed, and embedded microcallus clusters were transferred directly into 90 × 25 mm Petri dish (Star™Dish, Phoenix Biomedical, Spain) with approximately 25 ml of BI* medium (Table 1). Cultures were maintained in the dark at 24 ± 2 °C and subcultured on the fresh BI* medium every 30 days to obtain long-term callus cultures. After 30 days of callus proliferation, 0.5 g (± 0.05 g) of callus was transferred onto 90 × 15 mm Petri dish containing approximately 25 ml of the regeneration medium, i.e., LT-S.1, LT-S.2, LT-S.3, CRM.1, CRM.2, or CRM.3 (Table 1). Plates were incubated at 24 ± 2 °C with a 18/6 h (light/dark) photoperiod with a light intensity of 55 µmol m− 2 s− 1. After 30 days of culture, the light intensity was increased to 200 µmol m− 2 s− 1 (LED FITO PANEL 90 DW + FR, Biogenet).

PEG-mediated transfection of cannabis protoplasts

The isolation and purification of ‘Finola’ protoplasts was conducted in accordance with the methodology outlined above. Following the W5 wash, protoplasts were resuspended in MMG buffer (Table 1) and counted. The final density was adjusted to 1 × 10⁶ cells per ml, after which the protoplasts were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, 200 µl of protoplast suspension was transferred into an 11 ml conical centrifuge tube containing 20–40 µl of pX-08 YPet plasmid in TE buffer (430 ng pDNA/µl conc.; expected expression of YPet yellow fluorescent (constitutive fluorescence) protein derived from Aequorea victoria driven by CaMV 35 S promoter; see Zaman et al. [22] for details of the plasmid or Nguyen and Daugherty [23] for protein characteristics). The protoplast suspension was gently mixed, and then 220 µl of freshly prepared and filter-sterilized PEG solution (Table 1) was added. The solution was gently mixed and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. A volume of 6 ml of W5 solution was added and mixed gently, then centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 6 ml of KM medium and washed twice (centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min). Then, the protoplast pellet was resuspended in 200 µl of KM medium, and the subsequent steps were carried out as in the section Optimization of protoplast culture conditions. Following a 30-day culture period, protoplast-derived microcallus clusters were transferred directly into 90 × 15 mm Petri dishes containing approximately 25 ml of BI* medium. Cultures were maintained in the dark at 24 ± 2 °C and subcultured on fresh BI* medium after 30 days.

Data collection and statistical analysis

The efficiency of protoplast isolation was determined using a hemocytometer and presented as the number of protoplasts per gram of fresh weight (FW). The quality of protoplasts was defined by their viability and expressed as a percentage of protoplasts with green fluorescence out of the total observed cells, was estimated as described in Stelmach-Wityk et al. [17] by staining with fluorescein diacetate (FDA) 24 h after initiation of the culture and in a 5-day-old culture in the optimization experiments. Cell wall re-synthesis was estimated on the 5th day of culture by staining protoplasts with 3 µl of 0.01% aqueous solution of calcofluor-white (Sigma-Merck). Cell wall re-synthesis was expressed as the number of cells emitting bright blue fluorescence per total number of viable cells emitting green fluorescence. Plating efficiency, expressed as the number of cell colonies per total number of observed objects (i.e. cell colonies and undivided cells), was assessed on the 10th day of culture. The intensity of microcallus formation was assessed by using ordinal ranking [+ (rank 1) poor growth, ++ (rank 2) medium growth, +++ (rank 3) intensive growth] (Additional file 1: Fig. S5), and the median and quartile deviation of the rank were calculated.

To assess the impact of PEG on cannabis protoplasts, a control culture without treatment (PEG-) and a PEG treatment without plasmid (PEG+) were established. The expression of the YPet fluorescent protein was evaluated 24 and 48 h after transfection. The transfection efficiency was expressed as a percentage, representing the proportion of cells expressing the YPet fluorescent protein out of the total number of cells. The evaluation process involved counting two dishes from each of the three transfection replicates, with five fields of view counted on each dish (amounting to 150–240 cells per dish). Cells exhibiting green-yellow fluorescence were considered transformed (Fig. 5a2, b2). To determine the impact of PEG treatment on the quality of protoplasts, cell viability (by staining with FDA) was assessed on the first and fifth day of culture. All microscopic observations were performed under an inverted Leica DMi8 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany) with a suitable filter set for visualization of fluorescein fluorescence and YPet (λEx = 460–500 nm, λEm = 512–542 nm), and calcofluor (λEx = 365 nm, λEm > 420 nm).

All experiments were set up with at least three biological replicates (independent protoplast isolations). Protoplast isolation efficiency was assessed for each combination of: age of source tissue × enzyme solution × enzymolysis length. For the assessment of protoplast viability, transfection efficiency, cell wall re-synthesis, and plating efficiency, each culture variant was represented by two to three Petri dishes (technical replicates). Microscopic observations were performed on at least 100 cells per Petri dish. The mean values and SE were calculated based on these.

The overall effects of treatments were assessed using an unpaired T-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with separation of means done using the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test (HSD) for equal sample size to determine differences between the means. Significant differences were expressed at a p-value of 0.05. If assumptions of normality (Shapiro-Wilk’s test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test) were not met, and for the assessment of microcallus formation, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparison test were used. The computations were performed using Statistica ver. 13.0 (StatSoft. Inc.).

Results

Optimizing cannabis protoplast isolation and culture: impact on yield and viability

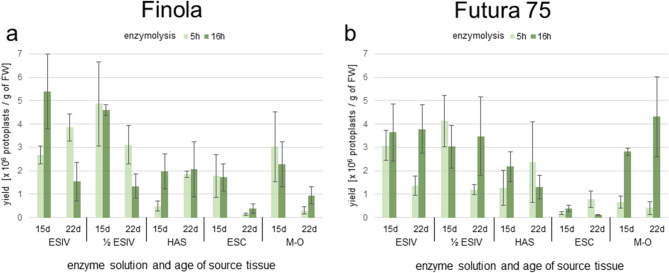

The leaves and petioles from in vitro grown plants (Fig. 2a, Additional file 1: Fig. S1) of both cultivars were an effective source of tissue for protoplast isolation, obtaining on average 2.12 × 106 protoplasts per 1 g of FW (Table 2). The mean protoplast yield for ‘Finola’ (2.2 × 106) was comparable to the yield obtained for ‘Futura 75’ (2.03 × 106). The composition of the enzyme solution and the age of the source tissue used for isolation had a significant impact on the protoplast yield (Table 2, Additional file 1: Fig. S2, Fig. S3). The highest protoplast yield was obtained with ½ ESIV and ESIV (3.22 × 106 and 3.17 × 106, respectively). On average, HAS solution yielded 1.69 × 106, and M-O 1.84 × 106 protoplasts per 1 g of FW. The average yield obtained with ESC solution did not exceed 0.7 × 106 (Table 2). For most of the tested enzyme solutions, 15-day-old leaves yielded more protoplasts (2.51 × 106) than 22-day-old leaves (1.73 × 106; Table 2, Fig. 3a, b). The duration of enzymolysis had a significant impact on the protoplast yield in ‘Futura 75’ (Table 2). On average, 1.54 × 106 of protoplasts per 1 g of FW were obtained after 5 hours of treatment, and 2.51 × 106 after 16 hours of treatment (Table 2). This effect was especially noticeable for M-O, with a 6-fold increase in the yield of protoplasts isolated from 22-day-old leaves and petioles with long compared to short enzymolysis. No such effect was observed for ‘Finola’ (Fig. 3a, b). Conversely, the enzyme solution ½ ESIV yielded a more uniform number of protoplasts from 15-day-old donors regardless of the duration of enzymolysis and cultivar, and could potentially be used for both short and long enzymolysis. No statistically significant interactions between the three tested variables (age of donor, enzyme solution used and duration of enzymolysis) were detected in either ‘Finola’ or ‘Futura 75’ (Fig. 3a, b).

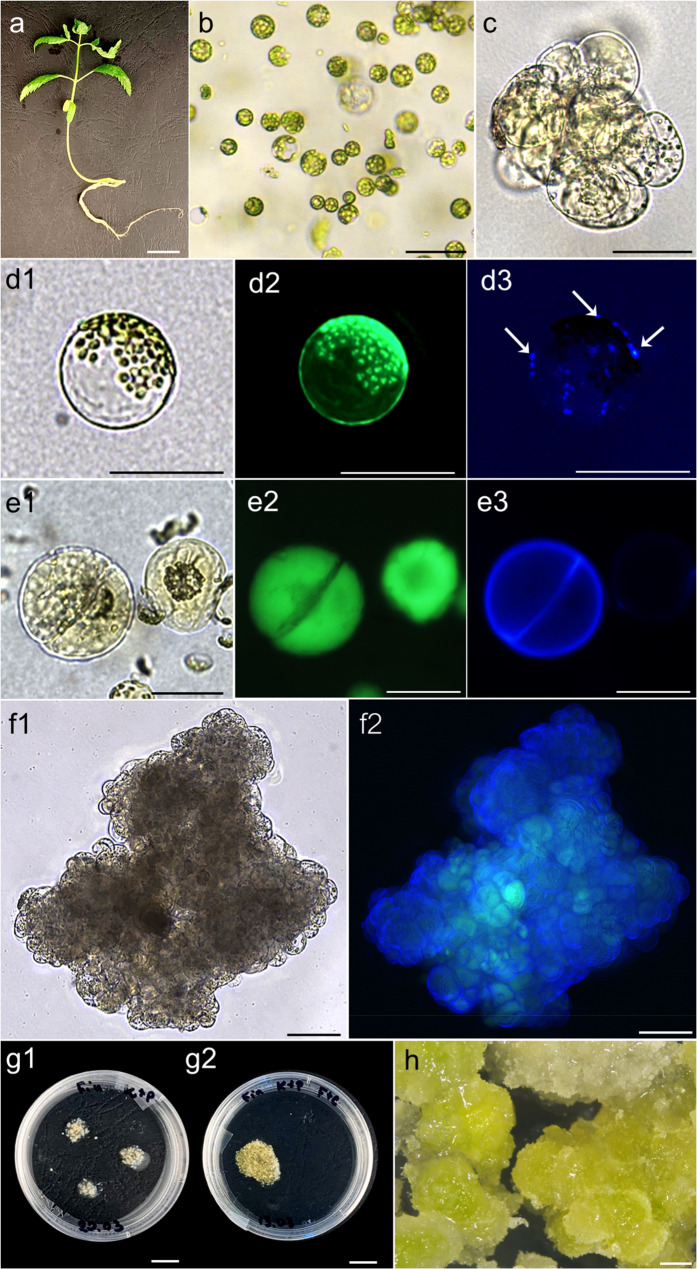

Fig. 2.

Isolation and culture of cannabis protoplasts. a a 15-day-old donor plant of ‘Finola’ germinated from seeds in vitro; b plant-derived intact protoplasts after long enzymolysis (16 h) in ½ESIV enzyme solution; c a multicellular protoplast-derived colony observed on the 10th day of culture in the KM medium; d1-3 a viable protoplast re-synthesizing cell wall stained with fluorescein diacetate (FDA; d2) and calcofluor white (CFW; d3) 24 h after embedding in alginate; d3 blue fluorescence signals marked with arrows indicate the presence of reconstituted cellulose on the cell surface; e1-3 first mitotic division of a viable (e2) protoplast-derived cell with a fully re-synthesized cell wall (e3) observed in the KM medium; f1-2 a viable multicellular protoplast-derived colony observed on the 15th day of culture in the KM medium (f1 – bright field, f2 – fluorescence: merged signals from FDA and CFW); g1 agarose droplets fully overgrown with protoplast-derived callus on the 20th day of culture; g2 alginate layer fully overgrown with protoplast-derived callus on the 20th day of culture; h protoplast-derived callus two weeks after transfer onto regeneration medium LT-S.1. Scale bar: 50 μm (b, c, d1-3, e1-3), 100 μm (f1-2), 1 mm (h), 1 cm (g1–2), 2 cm (a)

Table 2.

Mean yield of protoplasts isolated from leaves of two cultivars of cannabis with respect to the age of source tissue, composition of the enzyme solution and duration of enzymolysis

| Factor | n | Protoplast yield (x 106 per 1 g of FW) ± SE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Finola’ | ‘Futura 75’ | ||

| Age of source tissue | |||

| 15 days | 30 | 2.88 ± 0.39a | 2.14 ± 0.33a |

| 22 days | 30 | 1.56 ± 0.26b | 1.91 ± 0.37a |

| Enzyme solution | |||

| ESIV | 12 | 3.37 ± 0.60ab | 2.97 ± 0.54a |

| ½ ESIV | 12 | 3.48 ± 0.61a | 2.95 ± 0.57a |

| HAS | 12 | 1.60 ± 0.36bc | 1.78 ± 0.46ab |

| ESC | 12 | 1.00 ± 0.33c | 0.37 ± 0.11b |

| M-O | 12 | 1.64 ± 0.51bc | 2.05 ± 0.61ab |

| Enzymolysisa | |||

| short | 30 | 2.21 ± 0.36a | 1.54 ± 0.31b |

| long | 30 | 2.23 ± 0.35a | 2.51 ± 0.37a |

| Total/mean | 180 | 2.22 ± 0.25 | 2.02 ± 0.25 |

n number of independent protoplast isolations per cultivar, SE Standard error of the mean, FW Fresh weight;

ashort = 5 h, long = 16 h; statistical analyses were run separately for each section (factor) and column; in each section and column of the table means with the same letters were not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 (ANOVA with separation of means done using the Tukey post-hoc test (HSD) for equal sample size)

Fig. 3.

The effect of enzyme solutions on the protoplast yield of ‘Finola’ (a) and ‘Futura 75’ (b). The yield of protoplast isolations per 1 g of fresh weight (FW) with respect to the enzyme solution used (ESIV, 1/2ESIV, HAS, ESC and M-O), age of source tissue (15 and 22 days), and duration of enzymolysis (5 and 16 h). Each bar represent three replicates. No significant interactions between the age of donor, enzyme solution used and duration of enzymolysis were detected for either ‘Finola’ or ‘Futura 75’ (ANOVA)

The quality of protoplasts isolated from 15-day-old donors with ½ ESIV enzyme solution and long enzymolysis, determined by staining with FDA (Fig. 2d2) after 24 h of culture, was high for both cultivars. Viable cannabis protoplasts were round with no tendency to shrink and no visible membrane breakage (Fig. 2b, 2d1). 76.6% of ‘Finola’ and 81.1% of ‘Futura 75’ protoplasts were viable 24 h after isolation (Table 3). An 8% decrease in viability after five days of culture was observed for ‘Futura 75’, whereas the viability of ‘Finola’ protoplasts decreased by only 0.3%. Although the viability of protoplasts embedded in agarose and alginate did not differ significantly after 24 h of culture, a significant drop of quality (8.3%) was observed in the five-day-old protoplast cultures embedded in agarose (Table 3). Significant differences in protoplast viability on the 5th day of culture were observed for the tested culture media. On average, 77.5% of protoplasts cultured in the KM medium were viable, whereas the mean viability of protoplasts cultured in CPP was 72.7%. Supplementation of culture media with 100 nM of phytosulfokine (PSK) had various effects on protoplast viability. It led to a 3.3% decrease of cell viability in CPP medium and a 1.2% increase of viability in the KM medium (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of cultivar, protoplast embedding technique and culture medium on the viability of cannabis protoplasts and protoplast-derived cells

| Factor | Cell viability [% ± SE] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 24ha | 5db | ||

| Cultivarc | ||||

| Finola | 24 | 76.6 ± 1.1b | 76.3 ± 1.2a | |

| Futura 75 | 24 | 81.1 ± 1.9a | 72.9 ± 2.4a | |

| Protoplast embeddingd | ||||

| agarose | 24 | 78.1 ± 1.5a | 69.8 ± 2.1b | |

| alginate | 24 | 79.5 ± 1.7a | 79.4 ± 1.2a | |

| Medium variante | ||||

| CPP | 12 | 77.7 ± 2.3a | 72.7 ± 2.0b | |

| CPP + PSK | 12 | 80.6 ± 1.7a | 69.4 ± 3.5b | |

| KM | 12 | 77.0 ± 2.8a | 77.5 ± 1.3ab | |

| KM + PSK | 12 | 79.9 ± 2.1a | 78.8 ± 3.0a | |

| Total/mean | 144 | 78.8 ± 1.1 | 74.6 ± 1.4 | |

n number of analyzed protoplast cultures from at least three independent protoplast isolations, SE Standard error of the mean

aAssessed after 24h of the protoplast culture

bAssessed on the 5th day of the culture

cMeans represent averages of two embedding techniques and four medium variants

dMeans represent averages of two cultivars and four culture variants

eMeans represent averages of two cultivars and two embedding techniques; PSK = 100 nM of phytosulfokine; statistical analyses were run separately for each section (factor) and column; in each section and column of the table means with the same letters were not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 (ANOVA with separation of means done using the Tukey post-hoc test (HSD) for equal sample size)

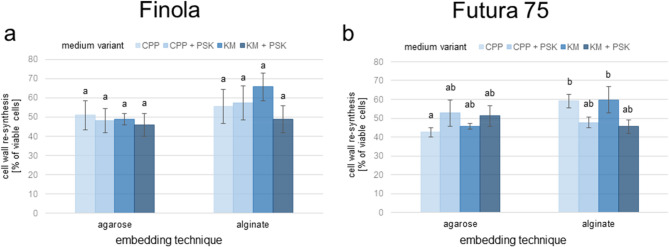

Influence of embedding technique and culture medium on cannabis protoplast cell wall re-synthesis and plating efficiency

Regardless of the embedding technique and culture medium used, cannabis protoplasts showed the ability to completely re-synthesize their cell walls. By the fifth day of culture, approximately half of the viable protoplasts underwent a complete (Fig. 2e3) or partial (Fig. 2d3) cell wall re-synthesis (Table 4). Generally, the efficiency of the cell wall re-synthesis was higher for protoplasts embedded in alginate (Fig. 4a, b). The effect of the culture medium on the efficiency of cell wall re-synthesis was more pronounced for ‘Futura 75’ than for ‘Finola’. Protoplasts embedded in alginate displayed lower re-synthesis efficiency when cultured in media supplemented with 100 nM of PSK, whereas the re-synthesis efficiency for protoplasts embedded in agarose did not change significantly in the presence of PSK.

Table 4.

Effect of cultivar, protoplast embedding technique and culture medium on the cell wall re-synthesis of cannabis protoplast-derived cells

| Factor | n | Cell wall re-synthesis [% ± SE]a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivarb | |||

| Finola | 24 | 52.6 ± 2.4a | |

| Futura 75 | 24 | 50.5 ± 1.8a | |

| Protoplast embeddingc | |||

| agarose | 24 | 48.2 ± 1.7b | |

| alginate | 24 | 54.9 ± 2.4a | |

| Medium variantd | |||

| CPP | 12 | 52.0 ± 3.3a | |

| CPP + PSK | 12 | 51.4 ± 3.0a | |

| KM | 12 | 55.0 ± 3.3a | |

| KM + PSK | 12 | 47.8 ± 2.5a | |

| Total/mean | 144 | 51.6 ± 1.5 | |

n number of analyzed protoplast cultures from at least three independent protoplast isolations, SE Standard error of the mean

aAssessed on the 5th day of culture

bMeans represent averages of two embedding techniques and four culture variants

cMeans represent averages of two cultivars and four medium variants

dMeans represent averages of two cultivars and two embedding agents; PSK = 100 nM of phytosulfokine; statistical analyses were run separately for each section (factor); in each section means with the same letters were not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 (ANOVA with separation of means done using the Tukey post-hoc test (HSD) for equal sample size)

Fig. 4.

The effect embedding technique on cell wall re-synthesis of cannabis protoplasts. The efficiency of cell wall re-synthesis in five-day-old protoplast cultures of ‘Finola’ (a) and ‘Futura 75’ (b) with respect to the embedding technique and culture medium. Each bar represent three replicates. Means with the same letters were not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 (ANOVA with separation of means done using the Tukey post-hoc test (HSD) for equal sample size)

On the 10th day of culture, multi-cell colonies were formed (Fig. 2c). At that time, on average 15.8% of protoplasts underwent cell divisions (Fig. 2e1-e3). Due to a lack of synchrony in development, the size of colonies varied considerably, but by the 15th day of culture were mostly compacted and comprised of hundreds of cells (Fig. 2f1, 2f2). The mean plating efficiency did not differ significantly between tested cultivars (15.88% and 15.76% for ‘Finola’ and ‘Futura 75’, respectively) and embedding agents (13.93% and 17.73% for agarose and alginate, respectively) but was medium-dependent (Fig. 5). On the 10th day of culture, only 5.2% of cells cultured on CPP medium formed cell colonies. Approximately a 6-fold increase in plating efficiency (28.8%) was observed in the KM medium supplemented with PSK (Fig. 5b). The addition of 2-aminoindane-2-phosphonic acid (AIP) did not increase plating efficiency in protoplast cultures.

Fig. 5.

Effect of protoplast embedding technique (a) and culture medium (b) on the plating efficiency in protoplast cultures of two cannabis cultivars. Plating efficiency is expressed as frequency of cell colonies formed assessed on the 10th day of the protoplast culture. Means with the same letters were not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05 (ANOVA with separation of means done using the Tukey post-hoc test (HSD) for equal sample size). Abbreviations: SE – standard error of the mean; PSK = 100 nM of phytosulfokine; AIP = 0.04 mg of 2-aminoindane2-phosphonic acid. Number of analyzed protoplast cultures (from at least three independent isolations) per cultivar: a n = 18; b n = 6

Cannabis protoplast-derived callus development: medium optimization, cultivar-specific responses, and regeneration limitations

Continuous mitotic divisions of the protoplast-derived cells led to the formation of microcallus visible to the naked eye (≥ 0.5 mm) between 15th and 20th day of culture (Fig. 2g1, 2g2). The intensity of microcallus formation varied considerably and was dependent on the embedding technique and the culture medium used (Table 5, Additional file 1: Fig. S5; Additional file 2: Table S1-S6). For both cultivars, the most intense formation of microcallus was observed in the KM + PSK medium variant. For ‘Finola’, a medium intensity of microcallus formation was observed in KM, KM + PSK + AIP, and CPP + PSK media, whereas a low formation intensity was observed in CPP and CPP + PSK + AIP media. For ‘Futura 75’, the intensity of microcallus formation was more dependent on the basal medium used, rather than on media supplementation. Culture variants with the KM medium were characterized by medium-to-high intensity of microcallus formation, whereas CPP medium led to a lower formation intensity (Table 5).

Table 5.

Intensity of callus formation from the protoplast-derived cells of two cannabis cultivars

| Factor/cultivar | n | Median rank of callus formation intensity [± QD]a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Finola’ | ‘Futura 75’ | ||

| Protoplast embedding | |||

| agarose | 36 | 1.0 ± 0.51 | 1.0 ± 0.75 |

| alginate | 36 | 2.0 ± 0.251 | 1.0 ± 0.5 |

| Protoplast culture medium | |||

| CPP | 24 | 1.5 ± 0.51 | 1.0 ± 0.251 |

| CPP + PSK | 24 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.5 |

| CPP + PSK + AIP | 24 | 1.0 ± 1.02 | 1.0 ± 0.252 |

| KM | 24 | 2.0 ± 0.53 | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

| KM + PSK | 24 | 3.0 ± 0.251, 2, 3 | 2.5 ± 0.51, 2 |

| KM + PSK + AIP | 24 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 |

| Total | 216 | ‒ | ‒ |

PSK = 100 nM of phytosulfokine; AIP = 0.04 mg of 2-aminoindane2-phosphonic acid; statistical analyses were run separately for each section (factor) and column; in each section and column the number in superscript shared by two entries indicates a significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference in the intensity of callus formation revealed by U Mann-Whitney test (for protoplast embedding section) or by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test (for protoplast culture medium section)

n number of analyzed callus cultures (individual Petri dish), QD Quartile deviation

afor the details on the ranking of the intensity of callus formation see section Data collection and statistical analysis

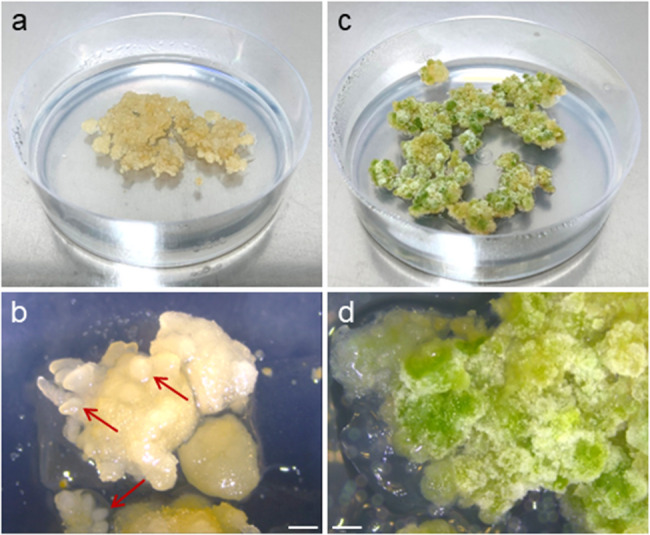

Microcallus of ‘Finola’ and ‘Futura 75’ characterized by the most intense growth (Fig. 2g2; alginate/KM + PSK medium) was transferred to a solid BI* proliferation medium. After 30 days of culture, robust growth was observed (Fig. 6a). The obtained callus was of good quality: friable and dry, ivory to yellowish. Formation of globular, embryo-like structures was observed within the first two months of culture (Fig. 6b). When transferred onto fresh BI* medium every four weeks, callus showed no signs of excessive production of phenolics, browning, or necrosis. When transferred onto regeneration media, callus appearance changed considerably (Figs. 2h and 6c and d; Additional file 1: Fig. S6). On LT-S.1, LT-S.2, LT-S.3, and CRM.3 media, intensive greening and a change of structure from proembryogenic to nodular were observed within the first month. Callus cultured on CRM.1 medium was more friable, still greening, but less intense. Within four weeks of culture on CRM.2 medium, callus began producing phenolics and showed signs of necrosis. Callus growth was much less intense, and only small clusters of callus turned green (Additional file 1: Fig. S6). None of the tested regeneration media induced shoot formation after 8 weeks of culture.

Fig. 6.

Cultures of protoplast-derived ‘Finola’ callus. a, b a 30-day-old callus culture on BI* proliferation medium with visible forming embryo-like structures (marked with arrows); c, d a 30-day-old green nodular callus cultured on LT-S.1 regeneration medium. Scale bar: 1 mm

Efficient cannabis protoplast transfection: overcoming PEG-induced stress and optimizing transformation efficiency

The developed method of protoplast isolation allowed for the generation of highly viable protoplasts capable of cell wall re-synthesis (Fig. 7c2) and able to undergo cell divisions even after polyethylene glycol (PEG) treatment (Fig. 7c1), which is a crucial step in developing an efficient transfection protocol. PEG treatment negatively affected protoplast viability, decreasing it from 81% for non-treated protoplasts to 72% for PEG-treated protoplasts (Fig. 8a). Subsequently, the frequency of cell wall re-synthesis was reduced from 82% (non-treated protoplasts) to 73% (PEG-treated protoplasts; Fig. 8b). As a result, on the 10th day of the culture, a 2.5-fold reduction of plating efficiency was observed in PEG-treated cultures (44% and 17% for non-treated and PEG-treated cultures, respectively; Fig. 8c). Although a significant decrease in cell division frequency was observed, PEG-treated protoplasts formed microcallus (Fig. 7d, e). The developed transfection protocol enabled the expression of the YPet fluorescent protein (Fig. 7a1, 7a2) localized in the nucleus of protoplasts (Fig. 7b1, 7b2), regardless of the tested amount of plasmid DNA (pDNA). Our study demonstrated that a two-fold increase in transformation efficiency (from 14% to 28%; Fig. 8d) could be achieved by doubling the amount (from 8.6 µg to 17.2 µg) of total pDNA used during transfection.

Fig. 7.

PEG-mediated transfection of cannabis protoplasts. a1, a2 protoplasts 24 h after PEG-treatment with visible transient expression of YPet fluorescent protein (transfected cells marked with arrows); b1, b2 transfected protoplast with visible nuclear localization of expressed YPet protein (strong green fluorescence on b2); c1, c2 PEG-treated protoplast with re-synthesized cell wall undergoing first asymmetric mitotic division; d cell colonies formed in 14-day-old PEG-treated culture; e formation of protoplast-derived microcallus in 4-week-old cultures: PEG(-) callus cultures derived from protoplasts not treated with PEG (control), YPet + callus cultures derived from protoplasts transfected with 17.2 µg of pX-08 YPet plasmid. Scale bar: 10 μm (c1, c2), 25 μm (b1, b2), 50 μm (a1, a2), 100 μm (d), 1 cm (e)

Fig. 8.

The effect of PEG treatment on culture parameters of cannabis protoplasts and transfection efficiency. a protoplast viability assessed on the 1 st and 5th day of culture; b cell wall re-synthesis expressed as percent of cells undergoing or with a complete re-synthesis in relation to viable cells on the 5th day of culture; c number of cell colonies (plating efficiency) on the 10th day of culture; d transfection efficiency observed 24 and 48 h after transfection. Number of replicates: an = 3, bn = 3, cn = 3, dn = 3. Statistically significant differences were calculated using an unpaired T-test and are marked by asterisks. Abbreviations: PEG - ‒ protoplasts not subjected to PEG treatment; PEG + ‒ protoplasts subjected to PEG treatment

Discussion

This study provides the first report of an efficient protocol for protoplast isolation, transient transfection, and callus culture in Cannabis sativa. There are no previous reports of a robust PEG-mediated protoplast transfection followed by an efficient culture and formation of microcallus in this species. Previous attempts have had limited success due to problems with inefficient protoplast isolation [12, 24], low protoplast viability [14], and consequently the failure of protoplasts to efficiently re-synthesize the cell wall, undergo mitotic divisions, and form microcallus. Moreover, many published reports focused only on protoplast isolation and transformation/transfection, without any attempt at establishing long-term protoplast cultures that could result in plant regeneration [9–11, 13, 14]. While whole plant regeneration from protoplasts remains elusive, this study reports the first steps toward this goal, including efficient isolation, PEG-mediated transfection, callus development, and early signs of differentiation. The key to achieving efficient microcallus formation from protoplasts lies in careful optimization of each step of protoplast isolation, purification, and culture.

Optimizing donor tissue age and enzyme concentrations for efficient cannabis protoplast isolation and yield

The efficiency of protoplast isolation and cell viability is determined by several factors, such as genotype, donor tissue (source and age), and the culture system or medium [3]. We used in vitro grown plants as a source of protoplasts, similarly to other studies carried out on this species [9–11, 14]. There are distinct advantages to sourcing protoplasts from organs, such as leaves or roots, rather than callus. Specifically, callus cultures are susceptible to somaclonal variation, potentially hindering the regenerative ability of protoplasts [25]. Somaclonal variation is regarded as undesirable in the commercial production of cannabis, as it can adversely influence crop yield, cannabinoid profiles, and general plant vigour [2]. On the other hand, when the regenerative ability of protoplasts obtained from somatic cells is low, the use of callus, especially of embryogenic nature, might improve regeneration success [12, 26]. The physiological and morphological changes in maturing plant tissues significantly impact protoplast isolation efficiency, as observed in our study. Similar to Král et al. [14], we successfully isolated protoplasts from young leaves and petioles of in vitro grown hemp plants, noting a substantial decrease in yield from 22-day-old explants compared to 15-day-old ones for cultivar Finola (Table 2). This highlights the critical role of tissue age as a protoplast donor.

The effectiveness of enzyme treatment and the duration of enzymolysis are key determinants for obtaining a high number of viable protoplasts [18]. Our research involved the use of four enzyme solutions with various concentrations of cellulolytic and pectinolytic enzymes routinely used for protoplast isolation from many species belonging to Allium, Apiaceae, and Brassicaceae [16, 17, 27, 28]. A concentration of 0.5 to 1.0% of cellulase R-10 and 0.05 to 0.1% of pectolyase Y-23 (as in ½ ESIV and ESIV enzyme solutions) yielded the highest numbers of viable protoplasts. The increase in the concentration of cellulase and pectolyase beyond these values, as in M-O enzyme solution, did not improve the yield (Table 2). In fact, the quality and quantity of the obtained protoplasts decreased substantially, as observed for HAS solution, most likely due to excessive enzymatic activity. Many previously published reports indicate either cellulase R-10 and macerozyme R-10, or a mix of cellulase R-10, macerozyme R-10, and pectolyase Y-23, as the most efficient enzymes for cannabis protoplast isolation [9–11, 14]. An enzyme solution consisting of 2.5% cellulase and 0.3% macerozyme (M-O) was reported by Matchett-Oates et al. and Král et al. to yield very high numbers of protoplasts, reaching as much as 7.8 × 106 cells/ml for an undisclosed high THC content genotype [11] and 9.9 × 106 cells/ml for ‘USO 31’ hemp variety [14]. The same enzyme solution, M-O, was tested in our study on two hemp cultivars, resulting in 51% and 31% lower yields for ‘Finola’ and ‘Futura 75’, respectively, when compared to the solution composed of only 0.5% cellulase R-10 and 0.05% pectolyase Y-23 (Table 2). Interestingly, Král et al. [14] reported failed protoplast isolations from ‘Finola’ and ‘Futura 75’ in vitro grown plants using M-O enzyme solution, while in our study a satisfactory, although inferior to ½ ESIV and ESIV enzymes, yield of protoplasts was obtained. These conflicting results highlight the well-known importance of environmental parameters or minor methodological differences in successful protoplast isolation. This includes careful attention to the quality of donor material, the solutions used, and the conditions of enzymolysis.

Alginate embedding and phytosulfokine-α enhance cannabis protoplast viability and plating efficiency

The method of protoplast culture is a critical factor influencing cell divisions and subsequent callus formation. Protoplast aggregation in liquid culture can negatively affect cell divisions, resulting in inconsistent callus formation and quality, and the build-up of toxic metabolites [29, 30]. A commonly adopted strategy to overcome this problem involves embedding protoplasts in a semi-solid matrix like calcium alginate [31], agarose [32], or agar [33]. By physically separating cells, protoplast embedding contributes to more uniform callus proliferation and diminishes the accumulation of potentially toxic by-products. As cannabis protoplast research is in its early phase, to date, there is only one available report of cannabis protoplast embedding. Monthony and Jones [12] embedded callus-derived protoplasts in 1.6% low-melting-point SeaPlaque agarose beads, resulting in mitotic divisions within the first three weeks of culture. In our study, cannabis protoplasts were characterized by slightly higher viability in alginate layers 24 h after embedding. More importantly, protoplast viability was maintained at the same level five days after alginate embedding, while protoplasts embedded in agarose suffered a 9% decrease in viability at the same time point (Table 3). The use of alginate has also consistently and significantly enhanced cell divisions and plating efficiency in ‘Finola’, when compared to agarose (Fig. 5), generally suggesting that alginate might be a better embedding agent for cannabis protoplasts. These findings are in line with other reports describing beneficial effects of alginate protoplast embedding, e.g. in carrot [34], cabbage [35], or sugar beet [36]. Another factor advocating for the use of alginate is that this embedding agent holds better optical properties (e.g. due to its transparency and thickness of the layer) after polymerization, facilitating microscopic observations.

Protoplast divisions and plant regeneration are highly dependent on the components of the culture medium. Effective protoplast cultures require the inclusion of suitable macro- and micronutrients, as well as additives, such as plant growth regulators, osmotic stabilizers, and various supplements [3]. Our research found that a rich KM medium [19] only slightly improved plating efficiency in cannabis protoplast cultures. Interestingly, we found that the continuous presence of phytosulfokine-α (PSK) in the protoplast culture medium has dramatically improved plating efficiency, and subsequently, microcallus formation in tested cultivars (Fig. 5). This plant-derived peptide is a signal molecule involved in many developmental processes, e.g., cell-to-cell communication [37] and cell growth and expansion [38]. A similar effect of exogenously applied PSK on the stimulation of cell division was observed in rice [37], sugar beet [39], carrot [34], cabbage [40], and parsnip [41]. Accumulation and oxidation of phenolics in rapidly developing protoplast cultures can affect plating efficiency and lead to the browning of the developing cell mass. 2-aminoindane-2-phosphonic acid (AIP), a specific competitive phenylalanine ammonia-lyase inhibitor [42], was reported to reduce flavonoid content and therefore reduce tissue browning and to enhance protoplast isolation from elm callus [43] and hemp [12]. In our study, supplementation of the protoplast culture medium with AIP did not improve plating efficiency and/or microcallus formation (Fig. 5; Table 5), although it reduced browning in long-term protoplast-derived callus cultures.

Challenges in cannabis shoot regeneration from callus cultures: genotype-dependent limitations and protocol reproducibility

Both tested cultivars displayed intense callusing on solid callus proliferation medium with PSK and AIP. Elevated levels of endogenous auxins most probably cause intensive callus development in cannabis, possibly impacting the auxin : cytokinin balance crucial for shoot regeneration [44]. Most published protocols of cannabis plant regeneration from non-meristematic tissues report very low regeneration efficiency [45–47]. One regeneration protocol developed by Lata et al. [48] resulted in 96.6% of callus cultures responding to MS medium with 0.5 µM TDZ, with an average of 12.3 shoots produced per culture. However, it is worth mentioning that authors included only one high-THC genotype (MX) in their research, not accounting for the genotype-dependent response expected in cannabis due to its high heterozygosity. Protoplast-derived callus obtained from ‘Finola’ and ‘Futura 75’ in the present study was transferred onto six different regeneration media, including the regeneration medium provided by Lata et al. [48], and its modified two variants. In 30-day-old cultures, changes in structure and greening of callus were apparent, though no shoot regeneration was observed, even after 90 days of culture. The lack of a positive response to regeneration medium might stem from genotype specificity, the origin of regenerated callus (leaf-derived vs. protoplast-derived), or could result from the difficulty to fully reproduce the regeneration protocol published by Lata et al. [48]. Monthony et al. [21] attempted to reproduce this protocol on ten genetically unique drug-type genotypes with successful induction of callogenesis in all of them, but were unable to achieve shoot regeneration in any of the tested genotypes. These results indicate a dire need for broader research on de novo regeneration in cannabis to establish a reliable regeneration system.

Optimizing PEG-mediated cannabis protoplast transfection: factors influencing efficiency

Producing transgene-free, gene-edited plants is a critical step in modern plant breeding. It enables the rapid generation of genetic variability and serves as a valuable tool for basic research focused on gene function. Protoplast transfection, either chemically or physically mediated, has been used for this application in a variety of species. During chemically mediated transfection, multiple factors such as the molecular weight of PEG, conditions of incubation, as well as plasmid concentration, size, and cell competence may influence the efficiency of this process [49–51]. The use of etiolated plants is possible and can yield favorable outcomes [52], yet green plants are also successfully employed in such experiments [9, 11, 53]. The rationale for utilizing green plants in this study was to compare the efficacy of our unmodified protoplast isolation protocol for transfection purposes, aligning with previous research that utilized the same type of plant material for transfection experiments in cannabis [9, 11]. PEG treatment can significantly decrease or even halt protoplast development in the culture [54]. To date, two molecular weights of PEG, i.e. 1500 and 4000, were successfully used for transfection of cannabis protoplasts. Beard et al. [9] used 40% w/v PEG 1500 solution, achieving a 27% transformation efficiency, whereas Matchett-Oates et al. [11] used 50% w/v PEG 4000 and reported a 23.4% transformation efficiency. In our study, a 40% w/v PEG 4000 solution was used, resulting in a 28% transfection efficiency observed 24 h after PEG-treatment (Fig. 8). These results are in correspondence with the above-mentioned reports.

The concentration of the plasmid can also impact transfection efficiency. We demonstrate that doubling the amount of pDNA (from 8.6 µg to 17.2 µg) results in a close to two-fold increase of transient protein expression in cannabis protoplasts. It is partially congruent with the general observation that increasing the concentration of pDNA results in higher transfection efficiency. Some earlier reports show that increasing pDNA concentration from 5 to 30 µg results in an over two-fold rise in transfection efficiency [11]. The transfection protocol developed in our study resulted in efficiency comparable to other studies carried out on cannabis, but with the use of substantially lower concentration of pDNA (17.2 µg in our study vs. 25 µg and 30 µg in Matchett-Oates et al. [11] and Beard et al. [9], respectively). It is important to stress that differences in the optimal concentration of pDNA might result from the size and conformation of the specific plasmid and should always be taken into account in the development of a transfection protocol [55, 56]. Our results are the first report showing that cannabis protoplasts are capable of sustained cell divisions and callus formation after PEG treatment.

Establishment of a method for efficient transfection of cannabis protoplasts provides an avenue for new strategies aimed at overcoming recalcitrance to plant regeneration. One such strategy involves overexpression of key transcription factors involved in regeneration, such as BABY BOOM, WUSCHEL or SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE, and Growth-Regulating Factors (GRFs) [57]. Arabidopsis GROWTH REGULATING FACTOR5 (AtGRF5) has been shown to effectively enhance genetic transformation and regeneration in several species such as sugar beet, rapeseed, soybean, and sunflower [58]. Moreover, GRF-GIF (GRF-Interacting Factor) chimeras can be fused with CRISPR/Cas9 to produce edited plants with higher regeneration efficiency [59]. Given a recent comprehensive insight into the transcriptome profiles of embryogenic and non-embryogenic cannabis callus [60], GRF-GIF strategy might prove a valuable tool in overcoming recalcitrance in this species.

Conclusions

This study successfully established a full and reproducible protocol for Cannabis sativa protoplast isolation, purification, and culture from leaves of in vitro grown young plants of two hemp cultivars: ‘Finola’ and ‘Futura 75’ (Fig. 9). We demonstrated that the application of exogenous peptide phytosulfokine together with protoplast embedding in alginate matrix significantly improved the division frequency of protoplast-derived cells and led to an efficient formation of callus. We also described the first attempt at de novo plant regeneration from protoplast-derived callus of cannabis. Additionally, an efficient protocol for protoplast transfection, followed by the formation of protoplast-derived callus, was presented for the first time, creating a tool for transient expression and gene editing studies in this valuable industrial crop. While a protoplast-to-plant regeneration system remains elusive for cannabis, this represents a significant step toward this goal and realizing the full potential of this technology.

Fig. 9.

Flow chart illustrating the developed protocol for protoplast isolation, purification, transfection, culture, and regeneration in Cannabis sativa L. Details and used abbreviations are explained in the Materials and methods section

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. This file provides six supplementary figures showing donor plants used for protoplast isolation (Fig. S1), protoplasts released with the use of five enzymes solutions with short and long enzymolysis (Fig. S2 and S3), rings of obtained viable protoplasts (Fig. S4), intensity of callus formation on agarose beads and alginate layers (Fig. S5), and callus cultures subjected to regeneration (Fig. S6).

Additional file 2. This file provides six supplementary tables presenting more detailed results of non-parametric statistical analyses (Table S1 to S6).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Patrick J. Krysan for generously providing the plasmid used in this study.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, KS-W; methodology, KS-W; validation, KS-W and KSz; formal analysis, KS‑W; investigation KS‑W and KSz; resources, EG; data curation, KS‑W; writing—original draft preparation, KS‑W and KSz; writing—review and editing, KS-W, AMP and EG; visualization, KS-W and KSz; funding acquisition, KS-W and EG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The subvention from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education for the University of Agriculture in Krakow in 2025 is acknowledged.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Grand View Research market analysis report. Industrial hemp market size, share & trends analysis report by application (animal care, textiles, food & beverages), by product (seeds, fiber, shivs), by region (North America, Asia Pacific), and segment forecasts, 2024–2030. www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/industrial-hemp-market. Assessed 23 July 2025.

- 2.Hesami M, Baiton A, Alizadeh M, Pepe M, Torkamaneh D, Jones AMP. Advances and perspectives in tissue culture and genetic engineering of cannabis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed KM, Bargmann BOR. Protoplast regeneration and its use in new plant breeding technologies. Front Genome Ed. 2021;3:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson M, Turesson H, Olsson N, Fält A-S, Ohlsson P, Gonzalez MN, et al. Genome editing in potato via CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein delivery. Physiol Plant. 2018;164:378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park J, Choi S, Park S, Yoon J, Park AY, Choe S. DNA-Free genome editing via ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery of CRISPR/Cas in lettuce. In: Qi Y, editor. Plant genome editing with CRISPR systems: methods and protocols. New York, NY: Springer; 2019. pp. 337–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subburaj S, Chung SJ, Lee C, Ryu S-M, Kim DH, Kim J-S, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis in Petunia × hybrida protoplast system using direct delivery of purified recombinant Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35:1535–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadakuduti SS, Starker CG, Ko DK, Jayakody TB, Buell CR, Voytas DF, et al. Evaluation of methods to assess in vivo activity of engineered genome-editing nucleases in protoplasts. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morimoto S, Tanaka Y, Sasaki K, Tanaka H, Fukamizu T, Shoyama Y, et al. Identification and characterization of cannabinoids that induce cell death through mitochondrial permeability transition in Cannabis leaf cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20739–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beard KM, Boling AWH, Bargmann BOR. Protoplast isolation, transient transformation, and flow-cytometric analysis of reporter-gene activation in Cannabis sativa L. Ind Crop Prod. 2021;164:113360. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim AL, Yun YJ, Choi HW, Hong C-H, Shim HJ, Lee JH, et al. Establishment of efficient Cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) protoplast isolation and transient expression condition. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2022;16:613–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matchett-Oates L, Mohamaden E, Spangenberg G, Cogan N. Development of a robust transient expression screening system in protoplasts of Cannabis. Vitro Cell Dev Biol - Plant. 2021;57:1040–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monthony AS, Jones AMP. Enhancing protoplast isolation and early cell division from Cannabis sativa callus cultures via phenylpropanoid inhibition. Plants. 2024;13:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu P, Zhao Y, You X, Zhang YJ, Vasseur L, Haughn G, et al. A versatile protoplast system and its application in Cannabis sativa L. Botany. 2023;101:291–300. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Král D, Šenkyřík JB, Ondřej V. Early protoplast culture and partial regeneration in Cannabis sativa: gene expression dynamics of proliferation and stress response. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1609413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grzebelus E, Szklarczyk M, Baranski R. An improved protocol for plant regeneration from leaf- and hypocotyl-derived protoplasts of carrot. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2012;109:101–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stelmach-Wityk K, Szymonik K, Grzebelus E, Kiełkowska A. Development of an optimized protocol for protoplast-to-plant regeneration of selected varieties of Brassica oleracea L. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24:1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menczel L, Nagy F, Kiss ZR, Maliga P. Streptomycin resistant and sensitive somatic hybrids of Nicotiana tabacum + Nicotiana knightiana: correlation of resistance to N. tabacum plastids. Theor Appl Genet. 1981;59:191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kao KN, Michayluk MR. Nutritional requirements for growth of Vicia Hajastana cells and protoplasts at a very low population density in liquid media. Planta. 1975;126:105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamborg OL, Miller RA, Ojima K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp Cell Res. 1968;50:151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monthony AS, Kyne ST, Grainger CM, Jones AMP. Recalcitrance of Cannabis sativa to de novo regeneration; a multi-genotype replication study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0235525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaman N, Seitz K, Kabir M, George-Schreder LSt, Shepstone I, Liu Y, et al. A Förster resonance energy transfer sensor for live-cell imaging of mitogen-activated protein kinase activity in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2019;97:970–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen AW, Daugherty PS. Evolutionary optimization of fluorescent proteins for intracellular FRET. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(3):355–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones R. Cell culture, protoplast isolation, and cell fusion of Cannabis sativa L.; Evaluation of chilling preventative chemicals and quality control of bananas in the tropics. 1979. 10.13140/RG.2.2.19104.43527.

- 25.Masani MYA, Noll G, Parveez GKA, Sambanthamurthi R, Prüfer D. Regeneration of viable oil palm plants from protoplasts by optimizing media components, growth regulators and cultivation procedures. Plant Sci. 2013;210:118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He X-Y, Xu L-J, Xu X-S, Yi D-D, Hou S-L, Yuan D-Y, et al. Embryogenic callus induction, proliferation, protoplast isolation, and PEG induced fusion in Camellia oleifera. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2024;157:75. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa H, Sato M, Suzuki M. Efficient plant regeneration from protoplasts isolated from long-term, shoot primordia-derived calluses of Garlic (Allium sativum). J Plant Physiol. 2002;159:449–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maćkowska K, Stelmach-Wityk K, Grzebelus E. Early selection of carrot somatic hybrids: a promising tool for species with high regenerative ability. Plant Methods. 2023;19:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davey MR, Anthony P, Power JB, Lowe KC. Plant protoplasts: status and biotechnological perspectives. Biotechnol Adv. 2005;23:131–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasil IK. The Progress. Problems and prospects of plant protoplast research. In: Brady NC, editor. Advances in Agronomy. Academic Press; 1976:119–60.

- 31.Brodelius P, Nilsson K. Permeabilization of immobilized plant cells, resulting in release of intracellularly stored products with preserved cell viability. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1983;17:275–80. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shillito RD, Paszkowski J, Potrykus I. Agarose plating and a bead type culture technique enable and stimulate development of protoplast-derived colonies in a number of plant species. Plant Cell Rep. 1983;2:244–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagata T, Takebe I. Plating of isolated tobacco mesophyll protoplasts on agar medium. Planta. 1971;99:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maćkowska K, Jarosz A, Grzebelus E. Plant regeneration from leaf-derived protoplasts within the Daucus genus: effect of different conditions in alginate embedding and phytosulfokine application. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2014;117:241–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiełkowska A, Adamus A. An alginate-layer technique for culture of Brassica Oleracea L. protoplasts. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 2012;48:265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall RD, Pedersen C, Krens FA. Improvement of protoplast culture protocols for Beta vulgaris L. (sugar beet). Plant Cell Rep. 1993;12:339–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsubayashi Y, Takagi L, Sakagami Y. Phytosulfokine-alpha, a sulfated pentapeptide, stimulates the proliferation of rice cells by means of specific high- and low-affinity binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13357–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kutschmar A, Rzewuski G, Stührwohldt N, Beemster GTS, Inzé D, Sauter M. PSK-α promotes root growth in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2009;181:820–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grzebelus E, Szklarczyk M, Greń J, Śniegowska K, Jopek M, Kacińska I, et al. Phytosulfokine stimulates cell divisions in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) mesophyll protoplast cultures. Plant Growth Regul. 2012;67:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiełkowska A, Adamus A. Peptide growth factor phytosulfokine-α stimulates cell divisions and enhances regeneration from B. oleracea var. Capitata L. protoplast culture. J Plant Growth Regul. 2019;38:931–44. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stelmach K, Grzebelus E. Plant regeneration from protoplasts of Pastinaca sativa L. via somatic embryogenesis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023;153:205–17. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones AMP, Saxena PK. Inhibition of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in Artemisia annua L.: A novel approach to reduce oxidative Browning in plant tissue culture. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e76802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones AMP, Shukla MR, Biswas GCG, Saxena PK. Protoplast-to-plant regeneration of American elm (Ulmus americana). Protoplasma. 2015;252:925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smykalova I, Vrbová M, Cvečková M, Plačková L, Žukauskaitė A, Zatloukal M, et al. The effects of novel synthetic cytokinin derivatives and endogenous cytokinins on the in vitro growth responses of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) explants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2019;139:381–94. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galán-Ávila A, García-Fortea E, Prohens J, Herraiz FJ. Development of a direct in vitro plant regeneration protocol from Cannabis sativa L. seedling explants: developmental morphology of shoot regeneration and ploidy level of regenerated plants. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hesami M, Jones AMP. Modeling and optimizing callus growth and development in Cannabis sativa using random forest and support vector machine in combination with a genetic algorithm. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;105:5201–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ślusarkiewicz-Jarzina A, Ponitka A, Kaczmarek Z. Influence of cultivar, explant source and plant growth regulator on callus induction and plant regeneration of Cannabis sativa L. Acta Biol Cracov Ser Bot. 2005;47:145–51. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lata H, Chandra S, Khan IA, Elsohly MA. High frequency plant regeneration from leaf derived callus of high ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol yielding Cannabis sativa L. Planta Med. 2010;76:1629–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Locatelli F, Vannini C, Magnani E, Coraggio I, Bracale M. Efficiency of transient transformation in tobacco protoplasts is independent of plasmid amount. Plant Cell Rep. 2003;21:865–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maas C, Werr W. Mechanism and optimized conditions for PEG mediated DNA transfection into plant protoplasts. Plant Cell Rep. 1989;8:148–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panda D, Karmakar S, Dash M, et al. Optimized protoplast isolation and transfection with a breakpoint: accelerating Cas9/sgRNA cleavage efficiency validation in monocot and dicot. aBIOTECH. 2024;5:151–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim Y, Lee E, Kang BC. Etiolation promotes protoplast transfection and genome editing efficiency. Physiol Plant. 2024;176:e14637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolasinliler G, Akkale C, Kaya HB. Establishing a reliable protoplast system for grapevine: isolation, transformation, and callus induction. Protoplasma. 2025. 10.1007/s00709-025-02069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hong K, Chen Z, Radani Y, Zheng R, Zheng X, Li Y, et al. Establishment of PEG-mediated transient gene expression in protoplasts isolated from the callus of Cunninghamia lanceolata. Forests. 2023;14:1168. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chong ZX, Yeap SK, Ho WY. Transfection types, methods and strategies: a technical review. PeerJ. 2021;9:e11165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lehner R, Wang X, Hunziker P. Plasmid linearization changes shape and efficiency of transfection complexes. Eur J Nanomed. 2013;5:205–12. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altpeter F, Springer NM, Bartley LE, et al. Advancing crop transformation in the era of genome editing. Plant Cell. 2016;28:1510–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]