Abstract

The expression of five denitrification genes coding for two nitrate reductases (narG and napA), two nitrite reductases (nirS and nirK), and nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) was analyzed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR of mRNA extracted from two sediment samples obtained in the River Colne estuary (United Kingdom), which receives high nitrogen inputs and for which high denitrification rates have been observed. The presence of all five genes in both sediment samples was confirmed by PCR amplification from extracted DNA prior to analysis of gene expression. Only nirS and nosZ mRNAs were detected; nirS was detected directly as an RT-PCR amplification product, and nosZ was detected following Southern blot hybridization. This indicated that active expression of at least the nirS and nosZ genes was occurring in the sediments at the time of sampling. Amplified nirS RT-PCR products were cloned and analyzed by sequencing, and they were compared with amplified nirS gene sequences from isolates obtained from the same sediments. A high diversity of nirS sequences was observed. Most of the cloned nirS sequences retrieved were specific to one site or the other, which underlines differences in the compositions of the bacterial communities involved in denitrifrification in the two sediments analyzed.

Microorganisms play a critical role in the global nitrogen cycle, both in oxidative (nitrification) and reductive (denitrification, nitrate ammonification, and nitrogen fixation) processes (18). Denitrification involves the reduction of nitrate, via nitrite and nitric oxide, to nitrous oxide or dinitrogen gas by a respiratory process under oxygen-limiting conditions (48). This process results in a net loss of nitrogen from the ecosystem, since nitrate is reduced to gaseous forms (some of which are greenhouse gases) which escape into the atmosphere. In ecosystems with high inputs of nitrogen, such as estuaries, denitrification mediates nitrogen load reduction and therefore contributes to eutrophication control. One such ecosystem is the River Colne estuary on the east coast of the United Kingdom, a macrotidal, hypernutrified, muddy estuary, where strong gradients of nitrate and ammonium are found, mainly due to inputs from the river and a sewage treatment plant at the head of the estuary. Higher denitrification rates have been observed in the sediments at the head of this estuary, correlating with the higher concentration of nitrate in river water (the mean denitrification rates at the head, middle, and mouth of the estuary were 557.1, 291.1, and 78.4 μmol of N m−2 h−1, respectively [29]). The denitrification rates are higher during autumn and early winter, when higher concentrations of nitrate enter the system (10, 29, 34), by a factor of 2 to 4 (at the head of the estuary the rates of denitrification were around 500 μmol of N m−2 h−1 in the summer and more than 1,000 μmol of N m−2 h−1 in the early winter [29]).

The characteristics of the River Colne estuary and the considerable data on denitrification in the sediments in this estuary make it an excellent ecosystem for studying the diversity and functional ecology of denitrifying microbial communities. A number of recent studies have involved molecular investigation of bacterial denitrification in natural environments (4). Since denitrifying bacteria belong to different phylogenetic groups, efforts have been directed toward amplification from environmental samples of functional genes involved in denitrification, including periplasmic and membrane-bound nitrate reductase genes (napA and narG) (12, 14, 23), genes encoding cytochrome cd1 and copper-containing nitrite reductases (nirS and nirK, respectively) (5-7, 15, 16, 22-24, 39), and a gene encoding nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) (22, 23, 35-37). These studies have revealed a high diversity of denitrification genes in the environment which often are divergent from the genes of cultured denitrifiers (6, 12, 14, 36). Moreover, the abundance of denitrifiers in the environment has been determined to be higher than that detected by culture techniques alone (24).

In addition to PCR-based gene detection, analysis of mRNAs as an indicator of gene expression should significantly enhance our understanding of active functional groups in the environment. Detection of mRNAs, which typically have a short half-life (34), provides a strong indication of specific gene expression at the time of sampling which can be correlated with the physicochemical conditions. In the cultured denitrifying bacteria studied to date, expression of the denitrification genes is induced at low oxygen tensions in the presence of nitrogen oxides (1, 17, 32, 48). For example, expression of nirS, norCB (encoding the NO reductase), and nosZ in Pseudomonas stutzeri is maintained at a low oxygen tension, as long as nitrate or nitrite is present, while a decline in the number of transcripts of these three genes is observed within the time determined by their half-lives (approximately 13 min in cells growing at a doubling time of 2.5 h) once nitrite disappears (17).

Expression of denitrification genes (nitrate, nitrite, and nitrous oxide reductase genes) has been analyzed by hybridization in continuous cultures in activated sludge subjected to aerobic-anaerobic transient periods (2), while expression of several gene systems in environmental samples has similarly been investigated by hybridization (e.g., merA [19, 26] and the gene encoding the large subunit of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, rbcL [30, 33]) or by RNase protection assays (e.g., nahA [13]). More recently, in a number of studies workers have utilized reverse transcription (RT)-PCR approaches to investigate gene expression in a variety of environments, including expression of nahA (44) and pmoA (8) in groundwater, nifH expression in lake water and termite guts (27, 47), rbcL expression in lake water (46), merR expression in lake water sediment (25), and expression of the Desulfovibrio [NiFe] hydrogenase gene in an anaerobic bioreactor (42).

In this study a RT-PCR-based approach was used to investigate the expression and diversity of five key genes, narG, napA, nirS, nirK, and nosZ, involved in bacterial denitrification in sediments from the hypernutrified River Colne estuary in the United Kingdom in which active denitrification had previously been demonstrated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Four bacteria were used as controls to test and optimize the amplification of denitrification genes and their corresponding mRNAs. Three of these bacteria, Paracoccus pantotrophus DSM 65, P. stutzeri ATCC 14405, and Ochrobactrum anthropi LMG 2136, are known denitrifiers. The first two of these organisms have a nirS gene (for cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase), while O. anthropi LMG 2136 has a nirK gene (for a Cu-containing nitrite reductase). As denitrifiers, all three possess nosZ, as well as narG and napA. Escherichia coli AB2463 was also included in this study as a representative of the nitrate ammonifiers; this organism has the ability to reduce nitrate to nitrite and carries both narG and napA. Control bacteria were inoculated into nutrient broth containing 40 mM NaNO3 and incubated at 30°C (or 25°C for O. anthropi LMG 2136) without shaking. Cultures were sampled (10-ml aliquots) during exponential growth (for E. coli at an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of approximately 0.6 and for denitrifiers at the time that gas production inside Durham tubes was observed, at an OD600 of approximately 0.2 for P. stutzeri ATCC 14405, an OD600 of approximately 0.4 for P. denitrificans DSM 65, and an OD600 of approximately 0.8 for O. anthropi LMG 2136). For napA mRNA analyses, E. coli cells were grown in nutrient broth containing 3 mM NaNO3 at 37°C to an OD600 of approximately 0.3, and prior to processing the culture was checked for the presence of nitrite by using Quantofix nitrate/nitrite test strips (Mackerey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,800 × g for 10 min.

Environmental samples.

Sediment samples (approximately 50 to 100 g) were collected from the upper 1 cm at low tide around noon in January 2001 at two different locations in the River Colne estuary in the United Kingdom (the time between both samplings was less than 1 h): in the middle of the estuary at Alresford, where the nitrate concentrations are moderate (about 0.3 to 0.5 mM in the winter), and at the head of the estuary at Colchester Hythe, where the nitrate concentrations in the water are as high as 1 mM and the benthic denitrification rates are high (10, 29, 34). Both sediments are composed mainly of fine silt, although the percentage of the silt-clay fraction is slightly higher at the Hythe site (10) and hence the oxygen penetration is lower (1.5 mm in the winter in the Hythe sediment, compared to 2.5 mm in the Alresford sediment [29]). The organic carbon content is higher in the Hythe sediment (10). The sediment temperatures at the time of sampling were 2°C at the Alresford site and 3°C at the Hythe site. The samples of sediment were maintained on ice during transport to the laboratory, which is located about 1 mile away from the Hythe site. The sediment samples were divided into aliquots and frozen at −80°C immediately for further molecular analyses.

MPN series and isolation of denitrifiers.

On the day of sampling, sediment samples were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and 1-ml portions were inoculated into test tubes containing 15 ml of 10-fold-diluted nutrient broth supplemented with 30 mM NaNO3 and an inverted Durham tube (three-tube most-probable-number [MPN] series). Tenfold dilution series were prepared from these suspensions, and after 7 days of incubation at 12°C the tubes were checked for turbidity, gas production inside the Durham tube, and the presence of nitrate and nitrite by using Quantofix nitrate/nitrite test strips (Mackerey-Nagel). Serial dilutions from the MPN tubes in which growth, nitrate reduction, and gas production were observed were plated on 10-fold-diluted nutrient agar containing 30 mM NaNO3 and incubated at 12°C. Isolates were streaked to purity and subsequently checked for denitrification activity by inoculation into nutrient broth containing 10 mM NaNO3, incubation at 12°C for 1 week, and examination of cultures for growth, gas formation in Durham tubes, and nitrate reduction with Quantofix nitrate/nitrite test strips (Mackerey-Nagel).

Isolation of nucleic acids from bacteria.

DNA and RNA were extracted by using the protocol of Wilson (43), taking precautions to prevent RNA degradation. The deionized water used to prepare buffers and solutions was treated with diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) overnight and then autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min. All the glassware employed was treated with 2 N NaOH, rinsed thoroughly with DEPC-treated deionized water, and autoclaved. Aliquots of nucleic acid were treated with 0.6 U of RNase-free DNase I (Roche) per μl at 37°C for 90 min in 10 mM sodium acetate-0.5 mM MgSO4 (pH 5.0) to digest the DNA present in the samples.

Nucleic acid extraction from sediment samples.

Total nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) were extracted from sediment aliquots (5 g) by using a modification of a protocol described previously (28). Sediment samples were resuspended in extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM sodium EDTA [pH 8.0], 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer; pH 8.0) containing 83 μg of proteinase K per μl and 3 mg of lysozyme per ml and incubated at 37°C for 10 min with shaking. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (final concentration, 2% [wt/vol]) was then added, and samples were incubated at 37°C for an additional 15 min. NaCl and hexadecylmethylammonium bromide (CTAB) were added to final concentrations of 1.5 M and 1% (wt/vol), respectively, and the samples were incubated at 65°C for 15 min and then subjected to a freeze-thaw cycle by submerging them in liquid nitrogen and subsequently in a water bath at 65°C. The lysate was subsequently cleared by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min in a prechilled centrifuge and extracted twice with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol/vol). Nucleic acids were precipitated by adding 0.7 volume of isopropanol with 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 4.8) and 1 mM MgCl2 and were pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C at 16,000 × g for 30 min. The pellet containing nucleic acids was washed with 70% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in DEPC-treated deionized water. Aliquots of the nucleic acid extract were digested with RNase-free DNase I (Roche) at 37°C for 90 min. Extracted DNA and RNA were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide. All the reagents and materials used for the extraction procedure were treated to prevent RNase contamination as described above.

PCR amplification of denitrification genes from DNA.

Five genes involved in the denitrification process (narG, napA, nirS, nirK, and nosZ) and the gene for 16S rRNA (used here as a positive control to test for the presence of PCR inhibitors in the environmental samples) were amplified by PCR from DNAs isolated from the environmental samples, control cultures, and denitrifying isolates cultured in this study. For the latter only nirS, nirK, and 16S rRNA genes were amplified. The protocols and primers used in this study (Table1) were mainly those described previously, with slight modifications as indicated in Table 1. The sequences of the primers described by Scala and Kerkhof (35) for amplification of nosZ were modified in order to make these primers more degenerate (Table 1). Nested PCR protocols were used for amplification of the narG and napA genes, as described previously (12, 14). The enzyme Taq polymerase from Qiagen was used for PCR amplification.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer | Primer type | Target gene or mRNA | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Annealing temp (°C) | Approx product size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| narG T37b | Forward | narG | CAY GGN GTN AAY TGY ACN GG | 58 | 14 | |

| narG T39b | Reverse | narG | TAR TGN GGC CCA NCC NCC NCC | 58 | 1,690 | 14 |

| narG W9b | Forward | narG | MGN GGN TGY CCN MGN GGN GC | 55 | 14 | |

| narG T38b | Reverse | narG | ACR TCN GTY TGY TCN CCC CA | 55 | 500 | 14 |

| napA V16c | Forward | napA | GCN CCN TGY MGN TTY TGY GG | 50 | 12 | |

| napA V17c | Reverse | napA | RTG YTG RTT RAA NCC CAT NGT CCA | 50 | 1,040 | 12 |

| napA V66c | Forward | napA | TAY TTY YTN HSN AAR ATH ATG TAY GG | 50 | 12 | |

| napA V67c | Reverse | napA | DAT NGG RTG CAT YTC NGC CAT RTT | 50 | 385 | 12 |

| nirS 1Fd | Forward | nirS | CCT AYT GGC CGC CRC ART | 52d | 5 | |

| nirS 6Rd | Reverse | nirS | CGT TGA ACT TRC CGG T | 52d | 890 | 5 |

| nirK 1Fe | Forward | nirK | GGM ATG GTK CCS TGG CA | 54e | 5 | |

| nirK 5Re | Reverse | nirK | GCC TCG ATC AGR TTR TGG | 54e | 514 | 5 |

| nosZ661bf | Forward | nosZ | CGG YTG GGG SMW KAC CAA | 56 | This study | |

| nosZ1773bf | Reverse | nosZ | ATR TCG ATC ARY TGN TCR TT | 56 | 1,100 | This study |

| 16S F27 | Forward | 16S rRNA | AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG | 55 | 21 | |

| 16S R518 | Reverse | 16S rRNA | CGT ATT ACC GCG GCT GCT GG | 55 | 531 | 28 |

International Union for Bacteriology codes for bases: Y, C or T; R, A or G; M, A or C; K, G or T; S, G or C; W, A or T; H, A, C, or T; D, A, G, or T; and N, A, C, G, or T.

narG products were amplified by using a nested PCR protocol. Primers narG T37 and narG T39 were used in the first PCR, and primers narG W9 and narG T38 were used in the second (nested) PCR. Reverse primer narG T39 was used in RT reactions for narG. After the RT reaction, the nested PCR protocol was used as it was for DNA.

napA products were amplified by using a nested PCR protocol. Primers napA V16 and napA V17 were used in the first PCR, and primers napA V66 and napA V67 were used in the second (nested) PCR. Reverse primer napA V17 was used in RT reactions for napA. After the RT reaction, the nested PCR protocol was used as it was for DNA.

nirS products were amplified by using a touchdown PCR protocol, with the temperature starting at 54°C and decreasing 0.5°C each cycle until an annealing temperature of 49°C was reached, followed by 25 cycles at 52°C. Q-solution (Qiagen) was used as an additive in the PCR mixture according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

nirK products were amplified by using a touchdown PCR protocol, with the temperature starting at 56°C and decreasing 0.5°C each cycle until an annealing temperature of 51°C was reached, followed by 25 cycles at 54°C. Bovine serum albumin (final concentration, 400 ng μl−1) was used as additive in the PCR mixture.

Q-solution (Qiagen) was used as an additive in the PCR mixture as recommended by the manufacturer.

RT reactions.

RT reactions were carried out by using the enzyme Superscript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer. The RT reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 500 μM, 2 pmol of each of the appropriate reverse primers (Table 1), and 200 U of Superscript II reverse transcriptase. RT reactions were performed for 50 min at 42°C, followed by incubation at 70°C for 15 min to inactivate the reverse transcriptase. RT products were either used immediately in PCRs or kept frozen at −20°C until they were used. The suitability of the extracted RNA for RT-PCR amplification was checked by performing RT-PCR control experiments with 16S rRNA (25, 28). To avoid the possibility of contaminating DNA in the RNA extracts used for RT-PCR, control PCR mixtures that contained RNA and were not previously subjected to RT were prepared.

Southern blot hybridization.

Products resulting from PCR amplification of the narG, napA, nirS, nirK, and nosZ genes and RT-PCR amplification of mRNAs from environmental samples and control bacteria were electrophoresed on agarose gels and subsequently transferred onto positively charged nylon membranes (Roche) for Southern hybridization. DNA was fixed to the membranes by baking them at 120°C for 30 min. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes were obtained by PCR by using DIG-labeled dUTP (Roche). PCR products amplified from P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 were used to generate probes for narG, napA, nirS, and nosZ. An additional probe for narG was generated by using products amplified from E. coli AB2463. The nirK probe was amplified from O. anthropi LMG 2136. DIG-labeled probes were purified from agarose gels before use. The membranes were prehybridized for 2 h and hybridized overnight at 68°C in hybridization buffer containing 5× SSC, 0.1% (wt/vol) N-laurylsarcosine, 0.02% (wt/vol) SDS, and 1% (wt/vol) blocking reagent (Roche) (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). After hybridization, the membranes were washed twice for 5 min at 68°C with washing solutions containing, consecutively, 4× SSC and 1% (wt/vol) SDS, 2× SSC and 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS, and 0.1× SSC and 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS. Hybridized probes were detected by using a DIG luminescent detection kit (Roche) as specified by the manufacturer and exposure to X-ray film (Roche).

Cloning and sequencing of nirS RT-PCR products.

nirS RT-PCR products amplified from sediment samples were concentrated and purified by electrophoresis in a low-melting-point agarose (1%, wt/vol) gel. Bands at the expected molecular weights were cut out of the gel and were used directly for cloning by using a TOPO TA cloning kit for sequencing (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Transformants were selected on Luria agar plates containing ampicillin and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). White colonies were screened by PCR by using vector primers, and plasmids were isolated from the colonies containing inserts of the expected size by using a Qiaprep 8 miniprep kit (Qiagen). The DNA sequences of plasmid inserts were determined by using vector primers and a BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer's recommendations, followed by electrophoretic analysis with an ABI 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequences of nirS genes of denitrifying isolates were obtained from amplified nirS PCR products (purified with a PCR purification kit obtained from Qiagen) by using primers nirS 1F and nirS 6R. Partial sequences of 16S rRNA genes were determined from the corresponding purified PCR 16S ribosomal DNA products by using primer 16S R518 (Table 1). nirS nucleotide sequences were translated into amino acid sequences by using the program TRANSEQ from the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite (EMBOSS) package at the United Kingdom Human Genome Mapping Project Resource Centre (http://www.hgmp.mrc.ac.uk/Software/EMBOSS). DNA and protein sequences were compared with sequences in the EMBL database by using FASTA, version 3 (31). Nucleotide sequences were aligned by using ClustalX (40). Only homologous positions at which nucleotides were found in all sequences were included in the analysis. Evolutionary distances, derived from sequence pair dissimilarities by using the Jukes-Cantor algorithm (20), were calculated by using the DNADIST program from the Phylogeny Inference Package (PHYLIP), version 3.573c (11). Dendrograms were generated by using neighbor joining, the least-squares algorithm of Fitch-Margoliash of the FITCH program, and parsimony methods from the PHYLIP package. Consensus trees were calculated after bootstrapping (200 replicate trees). Multifurcations were introduced by using the tree-editing tools in the ARB package (http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de) into a dendrogram calculated by the neighbor-joining method for the clusters whose branching order varied with the treeing method used.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data generated in this study have been deposited in the EMBL database under accession numbers AJ440469 to AJ440510.

RESULTS

Amplification of denitrification genes and their corresponding mRNAs from control bacteria.

First, experiments with control bacteria were performed in order to develop and optimize the conditions for RT-PCR amplification of transcripts for the denitrification genes narG, napA, nirS, nirK, and nosZ. The presence of the gene or genes of interest in the different control bacteria was confirmed by PCR amplification from genomic DNA prior to the analysis of transcripts. The expected patterns of PCR products for the narG, napA, nirS, nirK, and nosZ genes from the control bacteria were obtained (Table 2). The nitrate reductase genes narG and napA were amplified from all four control bacteria. The nitrite and nitrous oxide reductase genes (nirS, nirK, and nosZ) were amplified only from the denitrifier nirS from P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 and P. pantotrophus DSM 65, while nirK was detected only in O. anthropi LMG 2136. The PCR products were the expected sizes (approximately 500 bp for narG, 385 bp for napA, 890 bp for nirS, 514 bp for nirK, and 1,100 bp for nosZ), and in most of the cases sequencing or Southern hybridization confirmed that they were indeed the expected products.

TABLE 2.

PCR and RT-PCR amplification of denitrification genes and their corresponding mRNAs from control bacteria

| Strain | Amplification of denitrification gene and mRNA

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

narG

|

napA

|

nirS

|

nirK

|

nosZ

|

||||||

| DNA | mRNA | DNA | mRNA | DNA | mRNA | DNA | mRNA | DNA | mRNA | |

| Escherichia coli AB2463 | +a | +b | +a | +a | − | NDc | − | ND | − | − |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri ATCC 14405 | +b | +b | +a | ND | +a | +b | − | − | +a | +a |

| Paracoccus pantotrophus DSM 65 | + | − | + | ND | +a | +a | − | − | +a | + |

| Ochrobactrum anthropi LMG 2136 | + | − | + | ND | − | − | +a | +b | +a | + |

Product was confirmed by sequencing.

Product was confirmed by hybridization only.

ND, not determined.

RT-PCR products corresponding to nirS or nirK and nosZ were obtained from RNAs isolated from all three control denitrifiers (Table 2); nirK mRNA was detected in O. anthropi, and nirS mRNA was detected in the other two denitrifiers, P. pantotrophus and P. stutzeri. RT-PCR amplification of nirS mRNA from P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 characteristically gave two products, the expected band at approximately 890 bp and a shorter product; the longer product was confirmed to be nirS by hybridization. RT-PCR amplification with the narG primers yielded a single product from E. coli AB2463 but several products from P. stutzeri ATCC 14405. Hybridization with specific narG probes derived from both E. coli and P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 confirmed that one of these products corresponded to narG, whereas the others were nonspecific. Amplification of napA from mRNA of E. coli AB2463 gave an RT-PCR product of the expected size which was confirmed to be napA by sequencing.

MPN counts and isolation of denitrifying bacteria from estuarine sediment samples.

MPN counts of denitrifying bacteria were obtained for the sediment samples used for mRNA and DNA analyses in order to confirm the presence of denitrifiers in the sediments at the time of sampling. The MPN counts of nitrate-reducing bacteria (as determined by reduction of nitrate to nitrite) obtained from sediment samples taken at the middle (Alresford) and at the head (Hythe) of the estuary were approximately 4 × 106 and 3.5 × 107 cells per g (dry weight) of sediment, respectively. The number of denitrifiers, as determined by gas production, was also higher in the Hythe samples (3.5 × 103 cells per g [dry weight] of sediment, compared with 4 × 102 cells per g [dry weight] of sediment in the Alresford samples).

Isolates were obtained from the highest-dilution MPN tubes in which growth, nitrate reduction, and gas production were observed. Four isolates from Alresford and six isolates from Hythe reduced nitrate to nitrite or further with concurrent gas production and were therefore considered to be denitrifiers. Thirteen isolates, seven from Alresford and six from Hythe, reduced nitrate to nitrite but did not produce gas and were therefore considered to be nitrate reducers only. Finally, five isolates, three from Alresford and two from Hythe, reduced nitrate, although neither nitrite nor gas production was detected; these isolates could therefore be nitrate ammonifiers.

Partial 16S rDNA sequences of the isolates characterized as denitrifiers were determined; eight of these isolates were Pseudomonas spp., whereas the other two were closely related to Flavobacterium columnare. None of the sequences determined was identical to another sequence or to previously described sequences. The genetic potential for denitrification of these isolates was demonstrated by amplification of genes encoding nitrite reductase (a key enzyme in the process). nirS genes were amplified from five of the isolates, four belonging to Pseudomonas spp. (isolates BA1.6, BA2.5, and BA3.1 from Alresford and isolate BH11.6 from Hythe) and one belonging to Flavobacterium sp. (isolate BH12.12 from Hythe). The products were confirmed to be nirS genes by Southern hybridization, and partial sequences were determined (see below for phylogenetic analysis of these sequences). PCR amplification with nirS primers from the other five denitrifying isolates gave multiple products. Attempts to amplify nirK genes from these isolates also gave inconclusive results, and multiple weak products were obtained.

Detection of denitrification genes in estuarine sediments.

Following demonstration of the suitability of the primers used for PCR and RT-PCR amplification of the five denitrification genes and their mRNAs from control bacteria, it was necessary to validate the efficacy of the procedures when they were applied to environmental samples. Primers were initially used to investigate the presence of denitrification genes in the total bacterial community DNAs extracted from the Alresford and Hythe sediments. PCR products of 16S rRNA genes (positive control) were obtained with total community DNA, which indicated that there was a lack of inhibitors of PCRs in the extracts. Subsequently, all five genes (narG, napA, nirS, nirK, and nosZ) were PCR amplified from DNA extracts from both sediments. All five types of amplicons were the expected sizes, and their identities were later confirmed by hybridization with DIG-labeled specific probes (see below for nirS and nosZ; data not shown for narG, napA, and nirK).

Detection of expression of denitrification genes in estuarine sediments.

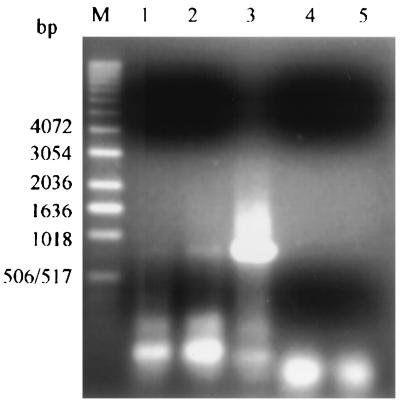

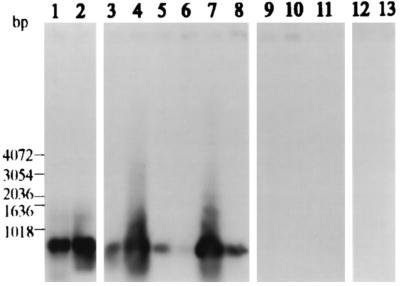

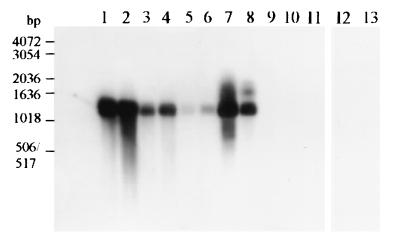

In order to assess expression of the narG, napA, nirS, nirK, and nosZ denitrification genes in the Alresford and Hythe sediments, RT-PCR amplification was carried by using RNA extracts from the sediments. Weak products that were ∼890 bp long were obtained with the nirS primers from RNA extracted from both sediments (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 2). Southern blot hybridization of these RT-PCR products with the nirS probe confirmed that they were nirS-related sequences (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4), as were the PCR-amplified nirS gene products (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 2). Amplification products were not detected, even after Southern blot hybridization, in control experiments in which the RT step was omitted (Fig. 2, lanes 12 and 13). RT-PCR products were not visible on agarose gels prepared from amplification reaction mixtures with napA, narG, nirK, and nosZ primers, although amplification products obtained from nosZ mRNAs from both sediment samples were detected by subsequent Southern hybridization with a nosZ-specific probe (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 6), which also hybridized with the corresponding amplified nosZ gene products (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 4). Hybridization with probes for napA, narG, and nirK did not detect the presence of amplified RT-PCR products from these three genes. Additional controls involving PCR amplification without a prior RT step of 16S rRNA, which is amplified more readily than mRNA, from DNase I-treated extracts failed to generate products and confirmed that amplification products which were generated by using the nirS and nosZ primers were derived from RNA and not from any contaminating DNA in the sample.

FIG. 1.

RT-PCR amplification of nirS mRNA from total RNA extracted from River Colne estuarine sediments. Lane M, marker; lane 1, Alresford sediment; lane 2, Hythe sediment; lane 3, P. denitrificans DSM 65 (positive control); lane 4, negative control for the RT reaction (the reaction mixture contained only RT reagents); lane 5, negative control for the PCR performed after the RT reaction (the reaction mixture contained only PCR reagents).

FIG. 2.

Detection of amplified nirS genes and nirS mRNAs in sediments from River Colne estuary by Southern blot hybridization. PCR and RT-PCR products were hybridized with a DIG-labeled nirS probe amplified from P. stutzeri ATCC 14405. Lane 1, PCR product from Alresford DNA; lane 2, PCR product from Hythe DNA; lane 3, RT-PCR product from Alresford RNA; lane 4, RT-PCR product from Hythe RNA; lanes 5 and 6, PCR and RT-PCR products obtained with P. denitrificans DSM 65, respectively (positive control); lanes 7 and 8, PCR and RT-PCR products obtained with P. stutzeri ATCC 14405, respectively (positive control); lane 9, negative control for PCRs with environmental DNA; lane 10, negative control for PCR amplification of the blank for the RT reaction (the reaction mixture contained only RT reagents); lane 11, negative control for the PCR performed after the RT reaction (the reaction mixture contained only reagents); lanes 12 and 13, PCRs without previous RT reactions for Alresford and Hythe RNAs, respectively (controls to ensure that contaminating DNA was not present in RNA extracts).

FIG. 3.

Detection of nosZ RT-PCR products obtained from RNAs extracted from River Colne estuarine sediments by Southern blot hybridization. RT-PCR products were hybridized with a DIG-labeled nosZ probe amplified from P. stutzeri ATCC 14405. Lanes 1 and 3, PCR products from Alresford DNA; lanes 2 and 4, PCR products from Hythe DNA; lane 5, RT-PCR product from Alresford RNA; lane 6, RT-PCR product from Hythe RNA; lane 7, PCR product obtained with P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 DNA (positive control); lane 8, RT-PCR product obtained with P. stutzeri ATCC 14405 RNA (positive control); lane 9, negative control for PCR amplification of the blank for the RT reaction (the reaction mixture contained only RT reagents); lane 10, negative control for the PCR performed after the RT reaction (the reaction mixture contained only reagents); lane 11, negative control for PCR with environmental DNA; lanes 12 and 13, PCRs without previous RT reactions for Alresford and Hythe RNAs, respectively (controls to ensure that contaminating DNA was not present in RNA extracts).

Diversity of amplified nirS mRNAs from sediments.

To obtain an overview of the diversity of amplified nirS mRNA sequences, the nirS mRNA RT-PCR products obtained from Alresford and Hythe sediments were cloned, and partial sequences (839 to 866 bp) of inserts were determined. Plasmids isolated from 12 of 79 clones obtained from the Alresford nirS RT-PCR product carried inserts of the expected size (approximately 890 bp); two of the sequences did not, however, correspond to nirS sequences and were discarded. Of the 95 clones obtained from the Hythe nirS RT-PCR product, 78 carried plasmids with inserts of the expected size. Fourteen clones selected at random for sequencing all had nirS-like sequences. Two of the cloned nirS RT-PCR products from the Alresford sediment (clones ANIS-21 and ANIS-80) were identical to one another, as were two of the sequences amplified from the Hythe sediment (clones HNIS-8 and HNIS-15). However, no sequences of clones obtained from the Alresford sediment were identical to sequences of clones obtained from the Hythe sediment. All of the sequenced nirS RT-PCR products showed the highest levels of identity with nirS sequences in the EMBL database (the FASTA values ranged from 68.8 to 96.6% identity for Alresford cloned sequences and from 64 to 88.6% identity for Hythe cloned sequences), and none of the sequences matched any nirS sequence from cultured denitrifiers. Comparison of the translated sequences with the SWISS-PROT database showed the highest levels of identity with cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase amino acid sequences, and the values were slightly higher than those obtained with nucleotide sequences (68.7 to 99.2% identity for Alresford cloned sequences and 71.6 to 94.8% identity for Hythe clones).

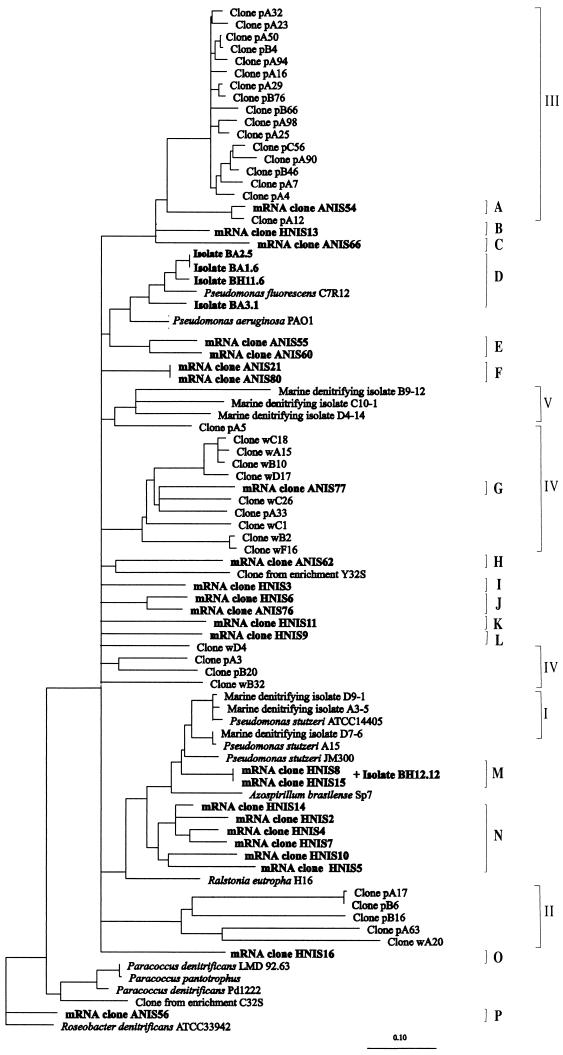

The broad diversity of nirS mRNA cloned sequences and nirS gene sequences from isolates obtained from the two River Colne sediments (see above) is shown in Fig. 4. The dendrogram also shows the relationships between the mRNA cloned sequences and the nirS gene sequences in the database, corresponding to cultured denitrifiers and clones obtained by Braker et al. in a recent study of amplified nirS genes from marine sediments (6) (the sequences reported in the latter study are considerably shorter than those that were determined in the present study, which resulted in some imprecision in the calculated affiliations). The nirS gene sequence of isolate BH12.12 was not included in the dendrogram due to its short overlap with the sequences of the marine sediment clones.

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram showing the relationships of partial nucleotide sequences from cloned nirS RT-PCR products and denitrifying isolates obtained from River Colne estuarine sediments with reference sequences in the databases. A neighbor-joining dendrogram with multifurcations introduced for the clusters whose branching order in the dendrogram varied with the treeing method used is shown. Clusters A to P define sequence types identified in this study, while clusters I to V represent clusters defined previously for marine sequences and isolates by Braker et al. (6). The clones from Alresford sediment were designated by using ANIS and a serial number (the designations for isolates begin with BA, which is followed by a number); the clones from Hythe were designated by using HNIS and a serial number (the designations for isolates begin with BH, which is followed by a number). All sequences obtained in this study are indicated by boldface type. The remaining clone sequences and isolates in the dendrogram were obtained from marine sediment samples in a previous study (6). The sequence of R. denitrificans ATCC 33942 was used as the outgroup.

Up to 15 sequence clusters were observed for the mRNA nirS sequences from the estuarine sediments, and an additional cluster contained exclusively nirS gene sequences from Pseudomonas spp. isolates (cluster D), which were closely related to the nirS gene sequence of Pseudomonas fluorescens. The branching of some of the clusters varied with the algorithm used for calculation of the dendrogram, and therefore the clusters are represented as multifurcations in the tree in Fig. 4. Other clusters grouped consistently with all the methods used for analysis. While no cloned mRNA nirS sequences were closely related to any of the Pseudomonas-like nirS sequences from the isolates (Fig. 4), a perfect match over the 492-nucleotide sequence was found between the nirS gene sequence of isolate BH12.12, identified as Flavobacterium sp., and the sequence of clones HNIS-8 and HNIS-15, the two redundant clones from Hythe sediment which constitute cluster M. Most of the sequence types were specific to one sampling site or the other, and only cluster J contained sequence types retrieved from both Alresford and Hythe sediments.

Some of the nirS mRNA cloned sequences were affiliated with previously described sequence types. Two cloned mRNA nirS sequences from Alresford grouped consistently with two nirS gene sequence clusters defined by Braker et al. in a previous study of marine sediment samples (6); clone ANIS-54 (cluster A in this study) and ANIS-77 (cluster G) were affiliated with clusters III and IV of Braker et al. (6), respectively, and clusters B and C also appeared to be related to cluster III of Braker et al. (6). The ANIS-62 clone sequence (cluster H) branched together with the nirS gene sequence of clone Y32S obtained from an enrichment from Puget Sound sediments (6) with all of the treeing methods employed, although it was rather distant and most probably represents a novel type of nirS sequence. The estuarine nirS mRNA sequences constituting cluster E were consistently related, albeit distantly, to the nirS gene sequences of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and P. fluorescens (Fig. 4). The sequences of clones constituting cluster M, which included two redundant cloned sequences and the nirS gene sequence of isolate BH12.12 (Flavobacterium sp.) from the Hythe sediment, were closely related to the nirS gene sequences of P. stutzeri and several isolates from marine sediments related to P. stutzeri as determined by 16S rRNA sequencing (6). Finally, the cloned sequence ANIS-56 (cluster P) was closely related to the nirS gene sequence from Roseobacter denitrificans.

Six of the remaining clusters defined for nirS mRNA sequences from River Colne estuarine sediments (clusters F, I to L, and O) did not group consistently with any of the known nirS gene sequences. A numerically dominant group of sequences, cluster N, from the Hythe sediment (6 of the 14 Hythe sequences) was related to the nirS gene of P. stutzeri but consistently branched as a separate group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, RT-PCR amplification was used to analyze expression of the bacterial denitrification genes narG, napA, nirS, nirK, and nosZ in two sediment samples from the River Colne estuary, where high denitrification rates have been reported (10, 29, 34). In preliminary experiments, all five denitrification genes were shown to be present in these sediments by PCR amplification from extracted DNA; these genes include both nitrite reductase genes, nirK and nirS, which have not been detected simultaneously in previous studies of denitrifying communities in marine environments (6). Subsequently, expression of the denitrification genes nirS and nosZ was demonstrated by RT-PCR in River Colne estuarine sediments; however, the nirS RT-PCR products were weak, and nosZ products were revealed only after hybridization with specific probes. Although the genetic experiments performed in this study were not quantitative, the product bands obtained from the Hythe sediment were consistently stronger than those generated from the Alresford sediment, suggesting that there was a higher concentration of template molecules (i.e., transcripts) in the Hythe sediments. This suggestion is consistent with the 10-fold-higher MPN counts for denitrifiers in the Hythe sediment determined in this study and with the higher denitrification rates measured previously (10, 29), although further testing is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Although detection of mRNAs in environmental samples by RT-PCR is potentially a powerful approach for analyzing gene expression in the environment, the technique suffers from inherent biases and limitations. Some of these are related to the RT-PCR itself, such as the suitability of primers to amplify a broad range of sequence types, the inhibition of reverse transcriptase or Taq polymerase (or both) by substances present in the RNA extracts, and the preferential amplification of certain templates during the PCR. Another critical factor is the quantity of template in the reaction mixture, which reflects in situ levels of gene expression and the stability of the transcripts within the cells. Previous studies of RT-PCR amplification of mRNAs from environmental samples have generally dealt with samples in which the activity of interest was high (8, 25, 27, 42, 44, 46), which indicates that the method can currently be successfully used only for transcripts expressed at a high level. Sample manipulation and processing may also affect results, and parameters such as the time of sampling, conservation of the environmental sample prior to RNA extraction, the efficiency of extraction and purification methods, and precautions taken to avoid degradation of the extracted mRNAs all influence the amount and quality of the RNA template and therefore the outcome of the RT-PCRs.

Although samples from sites exhibiting high denitrification rates were analyzed in this study, we were unable to detect transcripts for three of the five denitrification genes detected in the sediments (narG, napA, and nirK). Since the same RNA extracts were used in all RT-PCRs (which were carried out simultaneously), the failure to amplify these mRNAs was likely to be a consequence of the relative amounts of these transcripts in the total RNA extracts and/or methodological limitations in the amplification reactions, particularly the reactions for narG and napA that require nested PCR protocols. Expression of napA has been shown to respond to different regulating factors in the denitrifiers studied to date (3, 38). In E. coli it is suppressed at high nitrate concentrations (41), such as those typically found in the River Colne sediments. In the case of narG, it has previously been reported that mRNA for narG of P. fluorescens could not be detected once maximal expression of nirS and nosZ occurred (32). It is possible, therefore, that at the time of sampling transcription of narG genes in the sediments was not induced at a level detectable by the methods employed. This might also explain the failure to detect narG expression in two of the control denitrifiers used in this study, P. denitrificans DSM 65 and O. anthropii LMG 2136. Interestingly, narG expression was detected only in the two control denitrifiers that have similar mechanisms of sensing nitrate and regulating expression of the narG gene (17, 48). Finally, the failure to detect nirK mRNA may reflect the presence of low levels in the sediments studied, as suggested by the relatively weak amplification of nirK genes, and may indicate that denitrifiers possessing Cu-containing nitrite reductase genes are less abundant in the environment than denitrifiers possessing cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase (nirS) genes, as suggested by Braker et al. (6). Moreover, previously described primers for nirK have been shown to have a specificity restricted to well-conserved nirK sequences of the type which were used for their design (6) and therefore may not allow amplification of more divergent nirK sequences, which may be more abundant in environmental samples.

Cloning and sequencing of nirS RT-PCR products amplified from River Colne estuarine sediments revealed that the diversity of expressed nirS genes was high in both sediment samples. A total of 16 clusters of nirS genes were detected; 3 of these clusters overlapped with groups reported previously, but 13 seemed to be new (Fig. 4). Most of the sequence types were specific for one sampling site or the other, which indicates that different denitrifying populations were present in the two sediments. Only sequence types constituting cluster J were found in both Alresford and Hythe sediments. Cluster N, comprising six cloned sequence types, appeared to be predominant in the Hythe sediment. Variations in nirS gene sequences at different sampling sites have also been observed for marine sediments (6, 7), and variations in nosZ genes have been observed in marine environments (37).

The cloned nirS mRNA sequences from the River Colne estuary were only distantly related to nirS gene sequences of known cultured denitrifiers and to the nirS gene sequences of all the Pseudomonas spp. isolated from the same sediments. Conversely, the sequences constituting novel cluster M from Hythe, related to the nirS gene sequence of P. stutzeri, matched the nirS gene sequence of isolate BH12.12, which was identified as a member of the genus Flavobacterium, a genus for which no nirS gene sequence data are available in public databases. Since there is a lack of nirS gene sequence data for most of the denitrifying bacteria described thus far, which include members of a wide variety of phylogenetically and metabolically diverse bacterial and archaeal genera (48), it is not known whether new nirS sequences retrieved from environmental samples are sequences of unknown, uncultured bacteria or whether they are related to undetermined nirS gene sequences from known denitrifiers.

Although many cloned nirS mRNAs from River Colne sediments were more similar to clones isolated from marine sediments (6) than to mRNAs of cultured denitrifiers, they appeared to belong to phylogenetic clusters distinct from the marine sediment clones. This is not surprising, considering the geographical and hydrogeological differences between these two types of habitats (namely, estuarine sediments subjected to a tidal regimen in the case of the River Colne sediments and offshore marine sediments from depths ranging from 119 to 2,664 m in the case of Washington coast and Puget Sound marine sediments [6]). However, despite these differences two cloned sequences from Alresford sediment were affiliated with cluster III, formed exclusively by nirS sequences from Puget Sound sediments, and cluster IV, formed mainly by sequences retrieved from Washington coastal sediment (6). This indicates that there is wide distribution of the denitrifiers represented by these nirS sequences in marine and estuarine sediments of two different continents. Further analysis of nirS gene or mRNA sequences retrieved from denitrifying communities should demonstrate whether these sequence clusters represent ubiquitous denitrifiers in sediments.

This study demonstrated that both the presence and the expression of denitrification genes can be explored in complex environmental samples, such as sediments. Furthermore, the combination of the approaches used here and quantification of gene dosages, as recently demonstrated for nitrite reductase genes (9, 15, 45), should significantly enhance our understanding of bacterial denitrification in the environment.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the University of Essex.

We thank John Green for help during sampling, Junichi Takeuchi for collaboration during the final part of this study, and Konstantinos Damianakis for advice on Southern hybridization. We are also grateful to Steven Spiro for kindly providing the sequences of primers for narG amplification prior to publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumann, B., M. Snozzi, A. J. B. Zehnder, and J. R. Van der Meer. 1996. Dynamics of denitrification activity of Paracoccus denitrificans in continuous culture during aerobic-anaerobic changes. J. Bacteriol. 178:4367-4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann, B., M. Snozzi, J. R. VanderMeer, and A. J. B. Zehnder. 1997. Development of stable denitrifying cultures during repeated aerobic-anaerobic transient periods. Water Res. 31:1947-1954. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedzyk, L., T. Wang, and R. W. Ye. 1999. The periplasmic nitrate reductase in Pseudomonas sp. strain G-179 catalyzes the first step of denitrification. J. Bacteriol. 181:2802-2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bothe, H., G. Jost, M. Schloter, B. B. Ward, and K. P. Witzel. 2000. Molecular analysis of ammonia oxidation and denitrification in natural environments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:673-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braker, G., A. Fesefeldt, and K. P. Witzel. 1998. Development of PCR primer systems for amplification of nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) to detect denitrifying bacteria in environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3769-3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braker, G., J. Z. Zhou, L. Y. Wu, A. H. Devol, and J. M. Tiedje. 2000. Nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) as functional markers to investigate diversity of denitrifying bacteria in Pacific Northwest marine sediment communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2096-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braker, G., H. L. Ayala-del-Rio, A. H. Devol, A. Fesefeldt, and J. M. Tiedje. 2001. Community structure of denitrifiers, Bacteria, and Archaea along redox gradients in Pacific Northwest marine sediments by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of amplified nitrite reductase (nirS) and 16S rRNA genes Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1893-1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, Y. S., J. L. Halsey, K. A. Fode, C. C. Remsen, and M. L. P. Collins. 1999. Detection of methanotrophs in groundwater by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:648-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho, J.-C., and J. M. Tiedje. 2002. Quantitative detection of microbial genes by using DNA microarrays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1425-1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong, L. F., D. C. O. Thornton, D. B. Nedwell, and G. J. C. Underwood. 2000. Denitrification in sediments of the River Colne estuary, England. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 203:109-122. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP—Phylogeny Inference Package. Cladistics 5:164-166. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flanagan, D. A., L. G. Gregory, J. P. Carter, A. Karakas-Sen, D. J. Richardson, and S. Spiro. 1999. Detection of genes for periplasmic nitrate reductase in nitrate respiring bacteria and in community DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 177:263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming, J. T., J. Sanseverino, and G. S. Sayler. 1993. Quantitative relationship between naphthalene catabolic gene frequency and expression in predicting PAH degradation in soils at town gas manufacturing sites. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27:1068-1074. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregory, L. G., A. Karakas-Sen, D. J. Richardson, and S. Spiro. 2000. Detection of genes for membrane-bound nitrate reductase in nitrate-respiring bacteria and in community DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gruntzig, V., S. C. Nold, J. Z. Zhou, and J. M. Tiedje. 2001. Pseudomonas stutzeri nitrite reductase gene abundance in environmental samples measured by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:760-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallin, S., and P. E. Lindgren. 1999. PCR detection of genes encoding nitrite reductase in denitrifying bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1652-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Härtig, E., and W. G. Zumft. 1999. Kinetics of nirS expression (cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase) in Pseudomonas stutzeri during the transition from aerobic respiration to denitrification: evidence for a denitrification-specific nitrate- and nitrite-responsive regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 181:161-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbert, R. A. 1999. Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23:563-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeffrey, W. H., S. Nazaret, and T. Barkay. 1996. Detection of the merA gene and its expression in the environment. Microb. Ecol. 32:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jukes, T. H., and C. R. Cantor. 1969. Evolution of protein molecules, p. 21-132. In H. M. Munro (ed.), Mammalian protein metabolism. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 21.Lane, D. J. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p. 115-175. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 22.Linne von Berg, K.-H., and H. Bothe. 1992. The distribution of denitrifying bacteria in soils monitored by DNA-probing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 86:331-340. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mergel, A., O. Schmitz, T. Mallmann, and H. Bothe. 2001. Relative abundance of denitrifying and dinitrogen-fixing bacteria in layers of a forest soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 36:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michotey, V., V. Mejean, and P. Bonin. 2000. Comparison of methods for quantification of cytochrome cd1-denitrifying bacteria in environmental marine samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1564-1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miskin, I. P., P. Farrimond, and I. M. Head. 1999. Identification of novel bacterial lineages as active members of microbial populations in a freshwater sediment using a rapid RNA extraction procedure and RT-PCR. Microbiology 145:1977-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nazaret, S., W. H. Jeffrey, E. Saouter, R. Vonhaven, and T. Barkay. 1994. merA gene expression in aquatic environments measured by mRNA production and Hg(II) volatilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4059-4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noda, S., M. Ohkuma, R. Usami, K. Horikoshi, and T. Kudo. 1999. Culture-independent characterization of a gene responsible for nitrogen fixation in the symbiotic microbial community in the gut of the termite Neotermes koshunensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4935-4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nogales, B., E. R. B. Moore, W. R. Abraham, and K. N. Timmis. 1999. Identification of the metabolically active members of a bacterial community in a polychlorinated biphenyl polluted moorland soil. Environ. Microbiol. 1:199-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogilvie, B., D. B. Nedwell, R. M. Harrison, A. Robinson, and A. Sage. 1997. High nitrate, muddy estuaries as nitrogen sinks: the nitrogen budget of the River Colne estuary (United Kingdom). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 150:217-228. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul, J. H., A. Alfreider, J. B. Kang, R. A. Stokes, D. Griffin, L. Campbell, and E. Ornolfsdottir. 2000. Form IA rbcL transcripts associated with a low salinity/high chlorophyll plume ('Green River') in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 198:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson, W. R., and D. J. Lipman. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:2444-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philippot, L., P. Mirleau, S. Mazurier, S. Siblot, P. Hartmann, P. Lemanceau, and J. C. Germon. 2001. Characterization and transcriptional analysis of Pseudomonas fluorescens denitrifying clusters containing the nar, nir, nor and nos genes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1517:436-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pichard, S. L., and J. H. Paul. 1991. Detection of gene expression in genetically engineered microorganisms and natural phytoplankton populations in the marine environment by mRNA analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1721-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson, A. D., D. B. Nedwell, R. M. Harrison, and B. G. Ogilvie. 1998. Hypernutrified estuaries as sources of N2O emission to the atmosphere: the estuary of the River Colne, Essex, UK. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 164:59-71. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scala, D. J., and L. J. Kerkhof. 1998. Nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) gene-specific PCR primers for detection of denitrifiers and three nosZ genes from marine sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 162:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scala, D. J., and L. J. Kerkhof. 1999. Diversity of nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) genes in continental shelf sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1681-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scala, D. J., and L. J. Kerkhof. 2000. Horizontal heterogeneity of denitrifying bacterial communities in marine sediments by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1980-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sears, H. J., G. Sawers, B. C. Berks, S. J. Ferguson, and D. J. Richardson. 2000. Control of periplasmic nitrate reductase gene expression (napEDABC) from Paracoccus pantotrophus in response to oxygen and carbon substrates. Microbiology 146:2977-2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, G. B., and J. M. Tiedje. 1992. Isolation and characterization of a nitrite reductase gene and its use as a probe for denitrifying bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:376-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, H., C.-P. Tseng, and R. P. Gunsalus. 1999. The napF and narG nitrate reductase operons in Escherichia coli are differentially expressed in response to submicromolar concentrations of nitrate but not nitrite. J. Bacteriol. 181:5303-5308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wawer, C., M. S. M. Jetten, and G. Muyzer. 1997. Genetic diversity and expression of the [NiFe] hydrogenase large-subunit gene of Desulfovibrio spp. in environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4360-4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson, K. 1987. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria, p. 2.4.1-2.4.5. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Wilson, M. S., C. Bakermans, and E. L. Madsen. 1999. In situ, real-time catabolic gene expression: extraction and characterization of naphthalene dioxygenase mRNA transcripts from groundwater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:80-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, L., D. K. Thompson, G. Li, R. A. Hurt, J. M. Tiedje, and J. Zhou. 2001. Development and evaluation of functional gene arrays for detection of selected genes in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5780-5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, H. H., and F. R. Tabita. 1996. Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase gene expression and diversity of Lake Erie planktonic microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1913-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zani, S., M. T. Mellon, J. L. Collier, and J. P. Zehr. 2000. Expression of nifH genes in natural microbial assemblages in Lake George, New York, detected by reverse transcriptase PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3119-3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zumft, W. G. 1997. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:533-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]