Abstract

Uptake hydrogenases allow rhizobia to recycle the hydrogen generated in the nitrogen fixation process within the legume nodule. Hydrogenase (hup) systems in Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae show highly conserved sequence and gene organization, but important differences exist in regulation and in the presence of specific genes. We have undertaken the characterization of hup gene clusters from Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus), Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna), and Rhizobium tropici and Azorhizobium caulinodans strains with the aim of defining the extent of diversity in hup gene composition and regulation in endosymbiotic bacteria. Genomic DNA hybridizations using hupS, hupE, hupUV, hypB, and hoxA probes showed a diversity of intraspecific hup profiles within Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) strains and homogeneous intraspecific patterns within R. tropici and A. caulinodans strains. The analysis also revealed differences regarding the possession of hydrogenase regulatory genes. Phylogenetic analyses using partial sequences of hupS and hupL clustered R. leguminosarum and R. tropici hup sequences together with those from B. japonicum and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strains, suggesting a common origin. In contrast, Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) hup sequences diverged from the rest of rhizobial sequences, which might indicate that those organisms have evolved independently and possibly have acquired the sequences by horizontal transfer from an unidentified source.

A large amount of hydrogen is released from legume root nodules during the nitrogen fixation process. This hydrogen production has been described as one of the major factors that affect the efficiency of symbiotic nitrogen fixation (39). Uptake hydrogenases allow endosymbiotic bacteria to oxidize the hydrogen produced by nitrogenase. This symbiotic hydrogen oxidation has been shown to reduce the energy losses associated with nitrogen fixation and to enhance productivity in certain legume hosts (1, 14).

A detailed characterization of the hydrogen uptake (hup) system has been carried out in Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae (for a review, see reference 35). In both genera, the first component of this system is a membrane-bound, dimeric [NiFe] hydrogenase composed by two polypeptides of 35 and 65 kDa. These polypeptides are synthesized as precursors, which are proteolytically processed after metal cluster insertion. The hup genetic determinants are clustered in large DNA regions (20, 21), whose sequence analysis has revealed the presence of at least 17 common genes (hupSLCDFGHIJKhypABFCDEX) arranged in at least three operons with conserved gene composition and organization (35). Hydrogenase structural subunits are encoded by the hupS and hupL genes, whereas the remaining hup and hyp gene products are involved in the recruitment and incorporation of nickel and other metallic groups into the hydrogenase active site (for reviews, see references 12 and 35). Although the R. leguminosarum and B. japonicum hydrogenase systems are highly homologous, they show important differences in regulation and in the presence of specific genes. The hupE gene is specific for the R. leguminosarum UPM791 hup gene cluster. The function of its predicted product is unknown, but it has been proposed that it might act as a nickel transporter (35). In contrast, this strain lacks the hupNOP genes, whose gene products are involved in nickel metabolism in B. japonicum (16). Two completely different regulatory circuits control hydrogenase gene expression in these bacteria (36). Bradyrhizobium japonicum expresses hup genes in symbiosis as well as in microaerobic free-living cells. Four proteins are involved in regulation in this latter condition: those of the regulatory hydrogenase formed by HupU and HupV, the HupT repressor, and the transcriptional activator HoxA (5, 44, 45). In contrast, R. leguminosarum hup genes are only induced in symbiotic conditions (29). Analysis of the hupSL promoter expression showed that hup gene transcription is activated by NifA, the key regulator of the nitrogen fixation process (11). No genes homologous to hupUV and hupT have been found in this bacterium (10), and genetic analysis has determined that the hoxA gene present in R. leguminosarum is truncated and inactive (11). This may explain why vegetative cells of R. leguminosarum express no hydrogenase activity in the same cultural conditions that induce hydrogen uptake in B. japonicum (29).

Analysis of legume nodules for the presence of hydrogenase-positive strains has been carried out for several rhizobia-legume systems (for a review, see 2). These studies revealed that hydrogen oxidation capability is not a common trait in endosymbiotic bacteria. Hydrogenases are common among Bradyrhizobium species but rare in Rhizobium, Sinorhizobium, and Mesorhizobium. In addition to Bradyrhizobium japonicum, hydrogenase systems have been described for Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) (25) and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) (7, 31, 38), the microsymbionts of lupines and cowpeas, respectively. The Hup trait is widely represented among strains of these two species. On the basis of their hybridization patterns, several groups of Hup+ strains have been identified in Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) (25, 31). In contrast, the presence of a hydrogenase system has been reported in a few strains of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae (33) and it has never been described for R. leguminosarum bv. phaseoli (7), R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii (34), and Mesorhizobium sp. (Cicer) (24). As an exception, a high number of Rhizobium tropici strains possess the Hup trait but the hydrogenase activity displayed is not sufficient to eliminate the hydrogen evolved from nodules (23, 26, 43). Also, hydrogenase activity has been described for free-living cultures under nitrogen fixation conditions for Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 as well as for Sesbania rostrata bacteroids (40, 41).

Besides the identification of Hup+ strains, little information is available on hup gene composition for rhizobia other than B. japonicum USDA110 or R. leguminosarum UPM791. It is possible that different organizations of hup gene clusters exist, since differences in gene composition and regulation have already been observed in the two systems analyzed. In this work, we have characterized hup genetic determinants from strains belonging to Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus), Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna), Azorhizobium caulinodans, and Rhizobium tropici to define the range of diversity and differential characteristics of hup gene clusters in endosymbiotic bacteria. In addition, the relatedness of hup genes in these genera has been estimated from phylogenetic analysis carried out with partial hupS and hupL sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Rhizobium leguminosarum, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus), Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna), and Rhizobium tropici strains were routinely grown in tryptone-yeast extract (4), yeast-mannitol (46), or Rhizobium minimal (27) medium at 28°C. The Azorhizobium sp. and A. caulinodans strains were cultivated in YEB medium (17).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this work

| Strain | UPM strain numbera | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| R. leguminosarum | ||

| UPM791 | 791 | 22 |

| PRE | 1025 | J. Hontelez (Wageningen, The Netherlands) |

| B. japonicum | ||

| 122DES | 804 | H.J. Evans (Corvallis, Oregon) |

| Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) | ||

| UPM860 | 860 | 25 |

| 624 | 873 | C. Rydin (DMAC, Uppsala, Sweden) |

| 466 | 878 | D.C. Jordan (DMG, Guelph, Canada) |

| Z89 | 1029 | N. Lissova (UAAN, Lvic-Obroshyn, Ukraine) |

| IM43B | 939 | M. Chamber (SIA, Sevilla, Spain) |

| A. caulinodans | ||

| ORS571 | 1143 | B. Dreyfus (Montpellier, France) |

| ORS591 | 1160 | 6 |

| Azorhizobium sp. | ||

| ORS552 | 1161 | 6 |

| SG05 | 1162 | 32 |

| SD02 | 1163 | 32 |

| Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) | ||

| M2 | 1166 | This laboratory |

| M5 | 1167 | This laboratory |

| M18 | 1168 | This laboratory |

| M21 | 1169 | This laboratory |

| M43 | 1170 | This laboratory |

| B78 | 1171 | This laboratory |

| B96 | 1172 | This laboratory |

| B97 | 1173 | This laboratory |

| 32HI | 938 | 39 |

| R. tropici | ||

| USDA 2738 | 1144 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2822 | 1145 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 9030 | 1146 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2801 | 1147 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2786 | 1148 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2840 | 1149 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2787 | 1150 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2813 | 1151 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2734 | 1152 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2793 | 1153 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

| USDA 2838 | 1154 | P. van Berkum (USDA, Beltsville, Md.) |

UPM, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

USDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

DNA manipulation techniques.

Genomic DNA of Rhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, and Azorhizobium strains was extracted as previously described (22). Restriction enzyme digestions, PCR amplifications, agarose gel electrophoresis, and Southern blot transfers were carried out by standard protocols (37). For Southern hybridizations, hupS, hupE, hupUV, hypB, and hoxA DNA probes (Fig. 1) were labeled by PCR with digoxigenin DIG-11-dUTP (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) at a 40 μM final concentration. The R. leguminosarum UPM791 gene probes were generated using plasmid pRL618 as the template (3), except in the case of hoxA, where genomic DNA was used as the template. Primers used were DH1-PHO1 for hupS, hupE1-hupE2 for hupE, U69-L588 for hypB, and PC1-PC2 for hoxA. The sequences of the primers are listed in Table 2. A 250-bp DNA fragment of the B. japonicum hypB gene was used as probe after PCR amplification and labeling with the degenerate primer pair hypB1-hypB2. These primers were also used to investigate the presence of the hypB gene in different strains by PCR amplification. Two B. japonicum hoxA probes of 436 and 994 bp were obtained using the AD1-AD2 and PC1-PC2 primers, respectively, and plasmid pHU52 as template (19). To generate the B. japonicum hupUV probe, we cloned a 1,555-bp PstI/HindIII DNA region, containing the 3′ end of hupU and the 5′ half of hupV from plasmid pRY12 (5), into the pBluescript SK vector (Stratagene). The hupUV region was amplified and labeled by PCR with the T7 and Reverse primers. The hybridizing bands were visualized using a chemiluminescent DIG detection kit as described by the manufacturer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). DNA sequencing was carried out using the BigDye Terminator Cycle-Sequencing Ready Reaction kit and an ABI377 automatic sequencer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

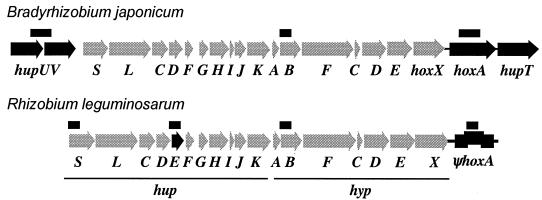

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of hydrogenase clusters in Bradyrhizobium japonicum 122DES and Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791. Grey arrows indicate hup and hyp genes common to both species. Black arrows show genes present and functional in only one microorganism. Thick lines above genes show the positions of DNA probes used in Southern hybridizations.

TABLE 2.

List of primers used in this work

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)b | Target gene and positiona |

|---|---|---|

| hupSL1 | GGNYTNGARTGYACNTGYTG | hupS 178-197 |

| hupSL2 | CCCCARTANCCRTTYTTRAA | hupL 559-540 |

| DH1 | CATATGGCAACTGCCGAGAC | hupS 1-17 |

| PHO1 | TCTAGAGTCGGGCCCTTGCAGCCC | hupS 813-795 |

| hupE1 | CTCGATCATATCCTGGCGAT | hupE 57-76 |

| hupE2 | CGATGCACATGACGCTCTAT | hupE 618-599 |

| hypB1 | ATHGARGGNGAYCARCARAC | hypB 408-430 |

| hypB2 | GCRAACATRTCNGGRTAYTT | hypB 691-672 |

| U69 | CCACGGCCATCATCATCACG | hypB 68-87 |

| L588 | AGGCGGCGGGACAGACGAGA | hypB 606-587 |

| PC1 | CGGCATCTACCAATATATCACC | hoxA 305-325 |

| PC2 | CGGTATAGGCGCCCTTCT | hoxA 741-723 |

| AD1 | ATYCTSTGCGAYCAGCGSATG | hoxA 150-170 |

| AD2 | TCSCGVAGRTTNCCSGGCCAA | hoxA 1144-1125 |

| nifHU1 | CACTACGTCCCAAAACACG | nifH 53-71 |

| nifHL2 | AGCATRTCYTCVAGYTCYTC | nifH 808-789 |

| Y1 | TGGCTCAGAACGAACGCTGCGGC | rm 20-43 |

| Y2 | CCCACTGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT | rm 361-338 |

Primer positions are given from the first nucleotide of the start codon in the corresponding gene.

Boldface letters correspond to bases added to create restriction sites in the amplified product.

Plasmid profiles were resolved by following the procedure of Eckhardt (13) with some modifications. Cultures of R. tropici were grown on HP medium (18) for 16 h, diluted in tryptone-yeast extract medium, and incubated until the optical density at 600 nm was 0.2. A volume of 1.5 ml was centrifuged, washed with 0.3% Sarkosyl, and resuspended in 10% Ficoll-1 mg of lysozyme liter−1-1 mg of RNase liter−1-0.1% bromophenol blue in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. Samples were loaded into a 0.6% agarose gel containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The gel was run at 10 mA for 2 h and 70 mA for 14 h at 4°C. For plasmid visualization, gels were stained with ethidium bromide. Plasmid DNA was transferred to nylon membranes by the Southern blotting technique. The R. leguminosarum nifH probe was generated and labeled by PCR, using primers nifHU1 and nifHL1 (Table 2) and UPM791 genomic DNA as the template.

Construction of hupS, hupL, and 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) phylogenetic trees from rhizobial sequences.

Partial hupS and hupL sequences were obtained by PCR amplification using genomic DNA from each strain and the degenerate primers hupSL1 and hupSL2, which amplify a ca. 1.5-kb DNA fragment containing the hupSL genes (Table 2). The temperature program was 180 s at 94°C; 35 cycles of 45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 48 or 51.7°C, and 90 s at 68°C; and 420 s at 72°C. Each PCR product was cloned in the PCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen BV, Groningen, The Netherlands) and sequenced using the T7 and Reverse primers. For the 16S rDNA sequences of rhizobial strains, a DNA region corresponding to nucleotides (nt) 20 to 338 of the Escherichia coli 16S rDNA was amplified from each strain using the Y1 and Y2 primers (Table 2) and the PCR amplification conditions described by Young et al. (51). The resulting fragments were cloned in PCR2.1-TOPO vector and sequenced. DNA sequences were optimally aligned using the CLUSTALX program (42) and visual refining. Neighbor-joining matrixes and trees were generated by CLUSTALX after bootstrapping (15) with 1,000 reiterations. Trees were drawn using TreeView software (28)

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank. Accession numbers for each strain are as follows: for the hupS region, AF466154 (Z89), AF466155 (UPM860), AF466156 (M2), AF466157 (M5), AF466158 (B78), AF466159 (B96), AF466160 (ORS571), AF466161 (ORS552), AF466162 (ORS591), AF466163 (USDA 2734), AF466164 (USDA 2838), and AF466165 (USDA 2787); for the hupL region, AF466753 (Z89), AF466754 (UPM860), AF466755 (466), AF466756 (M2), AF466757 (M5), AF466758 (B78), AF466759 (ORS571), AF466760 (ORS552), AF466761 (ORS591), AF466762 (USDA 2734), AF466763 (USDA 2838), and AF466764 (USDA 2787); and for the 16S rDNA region, AY072787 (UPM791), AF466166 (Z89), AF466167 (UPM860), AF466168 (IM43B), AF466169 (M5), AF466170 (B78), AF466171 (B96), AF4661672 (ORS552), AF466173 (ORS591), AF466174 (USDA 2734), AF466175 (USDA 2838), and AF466176 (USDA 2787).

RESULTS

Analysis of hup gene clusters in Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus), Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna), Azorhizobium caulinodans, and Rhizobium tropici.

In this work, we have characterized hup gene clusters of Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus), Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna), R. tropici, Azorhizobium caulinodans, and Azorhizobium sp. strains by DNA hybridization, using probes of the hupS, hupE, hypB, and hoxA genes from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 and the hypB, hupUV, and hoxA genes from B. japonicum 122DES. For these assays, we have used R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 (22) and B. japonicum 122DES (34) as positive control strains and R. leguminosarum bv. viciae PRE (3) as the negative control. The results obtained are separately described for each group and are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Summary of hydrogen oxidation gene composition in the rhizobial strains tested

| Strain | Detection of hybridization signala (PCR amplification)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hupS | hupE | hypB | hoxA | hupUV | |

| R. leguminosarum | |||||

| UPM791 | + | + | + | + | − |

| PRE | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. japonicum | |||||

| 122DES | + | − | + | + | + |

| Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) | |||||

| UPM860 | + | − | + | + | + |

| 624 | + | − | + | + | + |

| 466 | + | − | + | + | + |

| Z89 | + | − | + | + | + |

| IM43B | + | − | − (+) | + | − |

| A. caulinodans | |||||

| ORS571 | + | − | + | − | + |

| ORS591 | + | − | + | − | + |

| Azorhizobium sp. | − | ||||

| ORS552 | + | − | + | − | + |

| SG05 | − (−) | − | − | − | − |

| SD02 | − (−) | − | − | − | − |

| Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) | |||||

| M2 | + | − | + | + | − |

| M5 | + | − | + | + | − |

| M18 | + | − | + | + | − |

| M21 | + | − | + | + | − |

| M43 | + | − | + | + | − |

| B78 | + | − | + | + | − |

| B96 | + | − | + | + | − |

| B97 | + | − | + | + | − |

| 32H1 | + | − | − (+) | + | − |

| R. tropici | |||||

| USDA2738 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2822 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA9030 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2801 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2786 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2840 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2787 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2813 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2734 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2793 | + | − | + | − | − |

| USDA2838 | + | − | + | − | − |

The symbols + and − indicate presence and absence of hybridization signal in Southern blot experiments using the corresponding DNA probe. Symbols in parentheses indicate detection of the corresponding gene by PCR amplification and sequencing of the corresponding DNA fragment. PCR amplification were carried out using genomic DNA of the corresponding strains and primers hupSL1-hupSL2 and hypB1-hypB2 for hupS and hypB, respectively, as described in Materials and Methods.

Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus).

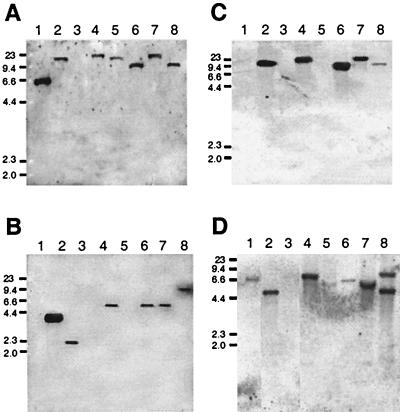

Southern blot experiments using a hupS gene probe from R. leguminosarum revealed hybridizing bands ranging from 10 to 23 kb in all Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strains (Fig. 2A). This experiment showed the presence of hup homologous DNA in strain Z89, which had never been subjected to this test before, and in strain IM43B, in which previous hybridization assays did not reveal hup homologous sequences (25). No hybridization signals were observed in any strain with the hupE gene probe (data not shown). In contrast, using the R. leguminosarum hypB probe, we detected a hybridizing band in all strains except for IM43B (Fig. 2B). In an attempt to improve DNA hybridization, we used a B. japonicum hypB probe but similar results were obtained (data not shown). As hypB is an essential constituent of all hup gene clusters characterized to date, we further investigated whether hypB was present in IM43B. This goal was addressed by PCR amplification using degenerate primers hypB1-hypB2 and genomic DNA from this strain. A 250-bp DNA fragment was obtained whose sequence revealed an 85% identity with B. japonicum hypB at the nucleotide level. This DNA fragment was used as probe in Southern experiments, and a hybridizing band of ca. 20 kb was observed for IM43B. For the remaining strains, we detected bands of sizes similar to those observed with the B. japonicum probe (data not shown). Using the hupUV probe, specific hybridization signals were identified in strains UPM860, 624, 466, and Z89 but not IM43B (Fig. 2C). In this filter, the hupUV-hybridizing bands had apparently the same size as those detected with the hupS probe (compare Fig. 2A and 2C), suggesting that hupUV and hupS might be adjacent genes in the genome of these strains, as is the case in the B. japonicum hup gene cluster (5). Finally, two hoxA gene probes constructed with primers PC1-PC2 and genomic DNA from either R. leguminosarum or B. japonicum were used to identify this gene in Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strains. The R. leguminosarum hoxA probe did not reveal any hybridization band (data not shown). In contrast, using the B. japonicum probe, signals corresponding to hoxA were detected in all strains (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Genomic DNA hybridizations of Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strains with hup, hyp, and hox DNA probes. Panels A and B and panels C and D show Southern hybridizations using hupS and hypB probes from R. leguminosarum and hupUV and hoxA probes from B. japonicum, respectively. Genomic DNA was restricted with EcoRI enzyme. Strains: R. leguminosarum UPM791 (lane 1), B. japonicum 122DES (lane 2), R. leguminosarum PRE (lane 3), Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) 624 (lane 4), IM43B (lane 5), Z89 (lane 6), 466 (lane 7), and UPM860 (lane 8). Numbers on the left indicate molecular sizes of markers (in kilobases).

The analysis of hybridizing bands obtained with the hup, hyp, and hox probes revealed four different profiles in Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strains, one apparently shared by strains 624 and 466 and three additional profiles corresponding to strains Z89, UPM860, and IM43B. In addition, the presence of hoxA and hupUV genes suggests that Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strains present a hup gene composition and regulation profile similar to that found in B. japonicum.

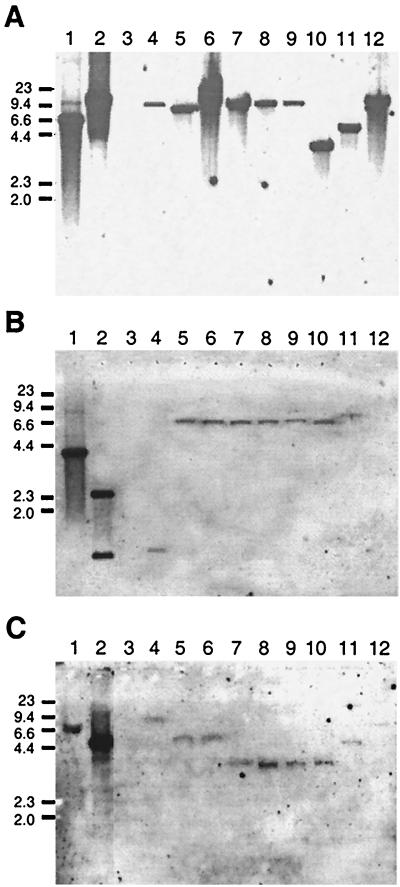

Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna).

DNA hybridization using the R. leguminosarum hupS probe showed different profiles of hup-specific bands among the Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) strains (Fig. 3A). Analysis of the hypB gene in these strains was carried out with R. leguminosarum and B. japonicum hypB gene probes. Similar results were obtained using both hypB gene probes. Hybridizing bands were detected in all strains except 32H1 (Fig. 3B). Following an approach similar to that used with Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus), we used degenerate primers to check for the presence of the hypB gene in this strain. PCR amplification and subsequent sequence analysis of the DNA fragment revealed a sequence 78% identical to that of the B. japonicum hypB gene, thus indicating the presence of hypB in this strain. No hybridization signals were obtained with the R. leguminosarum hupE gene probe (data not shown). In the search for the hoxA regulatory gene, we used two different B. japonicum probes constructed with PC1-PC2 and AD1-AD2 primers. Both hoxA probes showed similar results, which were visualized as faint hybridization bands in all strains (Fig. 3C). In contrast, hupUV genes were not detected using the corresponding B. japonicum probe (data not shown). Overall, our results show at least seven different EcoRI restriction patterns of hup hybridizing bands in the Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) strains tested and, more important, that these strains apparently differ from those of B. japonicum in the possession of hup regulatory genes.

FIG. 3.

Hybridization profiles of hup genes in Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) strains. EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs were hybridized with Rhizobium leguminosarum hupS (A) and hypB (B) probes and with a hoxA probe from B. japonicum (C). Strains: R. leguminosarum UPM791 (lane 1), B. japonicum 122DES (lane 2), R. leguminosarum PRE (lane 3), Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) M2 (lane 4), M5 (lane 5), M18 (lane 6), M21 (lane 7), M43 (lane 8), B78 (lane 9), B96 (lane 10), B97 (lane 11), and 32H1 (lane 12). Numbers on the left indicate molecular sizes of markers (in kilobases).

Azorhizobium sp. and Azorhizobium caulinodans.

Hybridization assays with the R. leguminosarum hupS probe revealed DNA bands of similar sizes (ca. 7 kb) in A. caulinodans strains ORS571 and ORS591 (Fig. 4A). An additional, upper band was observed in ORS591. In Azorhizobium sp. strain ORS552, a ca. 7-kb band was also observed, whereas no hybridizing signals were detected in strains SD02 and SG05. Since hupS is essential for hydrogenase activity and no studies in this regard had been carried out in these two strains, we further analyzed the presence of the hupS gene in these two latter strains by PCR amplification using genomic DNA and the degenerate primers hupSL1-hupSL2, designed to amplify an internal DNA region of the hupSL genes. No DNA product of the expected size (ca 1.5 kb) was obtained under any PCR condition tested (data not shown), suggesting that these strains are indeed Hup−. DNA bands hybridizing with the hupUV probe were also observed in strains ORS571, ORS552, and ORS591 (Fig. 4B). These bands had sizes similar to those hybridizing with the hupS gene probe, but an additional 6.6-kb band was also present that might have been due either to the presence of a second, less-conserved copy of the hupUV genes or of an EcoRI restriction site in the genomic DNA homologous to the probe. An extra upper band was again detected in ORS591, which may correspond to a second copy of the hupS and hupUV genes in the genome of this strain. Analysis with the R. leguminosarum hypB probe revealed a 9-kb band in strains ORS571, ORS552, and ORS591 (Fig. 4C). Finally, no hybridization signals were observed with either the R. leguminosarum hupE probe or the R. leguminosarum or B. japonicum hoxA gene probes for any strain tested (data not shown), suggesting that these genes are not present in Azorhizobium sp. and A. caulinodans Hup+ strains.

FIG. 4.

Southern hybridizations of genomic DNA from Azorhizobium sp. and A. caulinodans strains with hup and hyp DNA probes. Panels A and C show Southern hybridizations using R. leguminosarum hupS and hypB probes, respectively. Panel B shows the hybridization signals obtained with a hupUV probe from B. japonicum. In all cases, genomic DNAs were restricted with EcoRI enzyme. Strains: R. leguminosarum UPM791 (lane 1), B. japonicum 122DES (lane 2), R. leguminosarum PRE (lane 3), Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 (lane 4), Azorhizobium sp. ORS552 (lane 5), Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS591 (lane 6), Azorhizobium sp. SD02 (lane 7), and Azorhizobium sp. SG05 (lane 8). Numbers on the left indicate molecular size of markers (in kilobases).

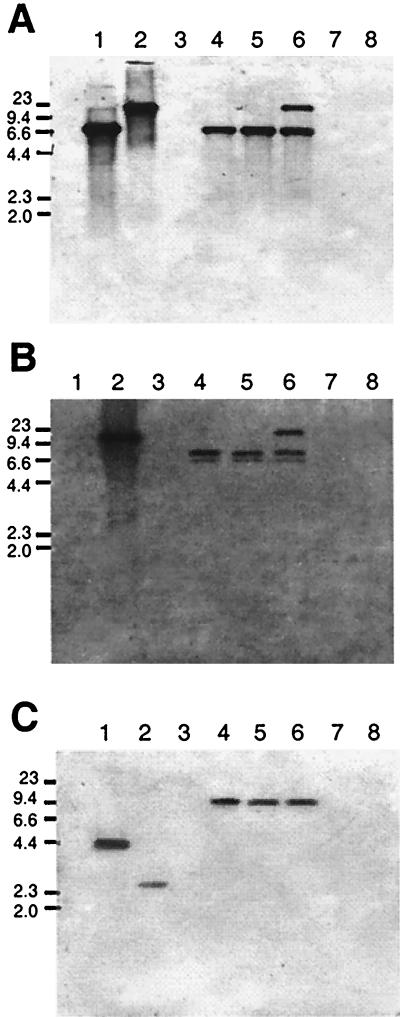

Rhizobium tropici.

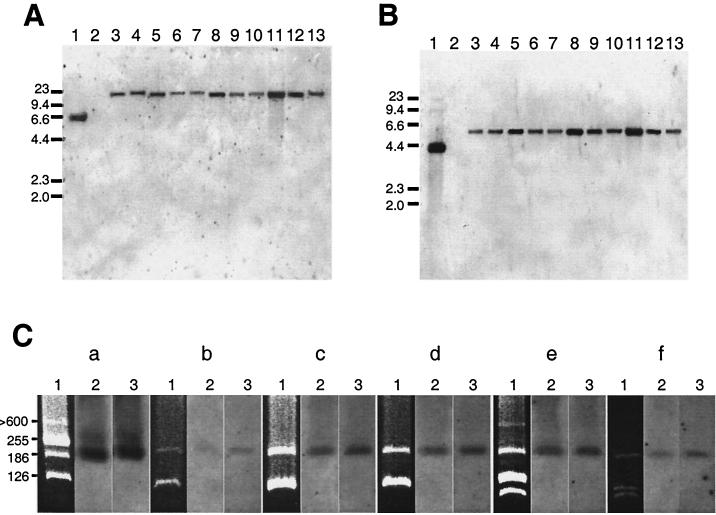

Previous studies on R. tropici using a B. japonicum structural gene probe showed a conserved hup hybridization pattern in all strains tested (26). To further investigate hup gene composition and variability within this species, we hybridized genomic DNA from those strains (USDA 2734, USDA 2786, USDA 2738, USDA 2793, USDA 9030, and USDA 2838), as well as that from strains USDA 2787, USDA 2801, USDA 2813, USDA 2822, and USDA 2840, with the hydrogen oxidation gene probes. All strains showed the same hybridization pattern with the R. leguminosarum hupS and hypB probes, containing 20- and 6-kb hybridizing bands, respectively (Fig. 5A and B), but no signal was detected with the hupE, hupUV, or hoxA gene probes. The conserved sizes of the hup hybridizing bands in all strains were further confirmed by analysis of genomic DNA digested with different restriction enzymes (HindIII, XhoI, PstI, and SalI), using a probe of the whole hup gene cluster of R. leguminosarum. This hybridization assay demonstrated that all R. tropici strains display the same hup hybridizing DNA bands, regardless of the enzyme used for DNA restriction (data not shown). The results described above show a remarkable conservation of the hup gene sequences in all R. tropici strains. Also, they reveal an apparent lack of homologues to the B. japonicum hydrogenase regulatory genes in this species.

FIG. 5.

DNA hybridization with hup and hyp probes and plasmid profiles of R. tropici Hup+ strains. (A and B) EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs were hybridized with the R. leguminosarum hupS (A) and hypB (B) probes. Strains for panels A and B: R. leguminosarum UPM791 (lane 1) and PRE (lane 2), Rhizobium tropici USDA 2734 (lane 3), USDA 2786 (lane 4), USDA 2738 (lane 5), USDA 2787 (lane 6), USDA 2793 (lane 7), USDA 9030 (lane 8), USDA 2801 (lane 9), USDA 2840 (lane 10), USDA 2838 (lane 11), USDA 2813 (lane 12), and USDA 2822 (lane 13). Numbers on the right indicate molecular sizes, in kilobases. (C) Plasmids were resolved by the Eckhardt procedure (see Materials and Methods) (lanes 1), transferred to a membrane, and hybridized to R. leguminosarum hupS (lanes 2) or nifH (lanes 3) gene probes. Subpanels: (a) R. leguminosarum UPM791 (control strain); (b to f) R. tropici strains USDA 9030 (b), USDA 2840 (c), USDA 2838 (d), USDA 2813 (e), and USDA 2822 (f). Numbers on the left indicate molecular sizes (in megadaltons) of R. leguminosarum UPM791 plasmids.

In addition, we studied the putative plasmid localization of hup genes in R. tropici strains by running Eckhardt gels and subsequent hybridization with R. leguminosarum hupS and nifH probes (Fig. 5C). For strain USDA 9030, hup genes have been previously localized in the symbiotic plasmid (26). In our study, at least three different plasmid profiles were observed by the Eckhardt method: profile a (strains USDA 9030, USDA 2840, and USDA 2838), profile b (strain USDA 2813), and profile c (strain USDA 2822) (Fig. 5C, lanes 1). The resolved plasmid DNA was transferred to filters and hybridized with the R. leguminosarum hup and nifH probes (Fig. 5C, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). In all strains, hup and nif hybridization signals were colocalized in the same plasmid, indicating that R. tropici hup genes are always located in the symbiotic plasmid.

Phylogenetic analysis of rhizobial hup sequences.

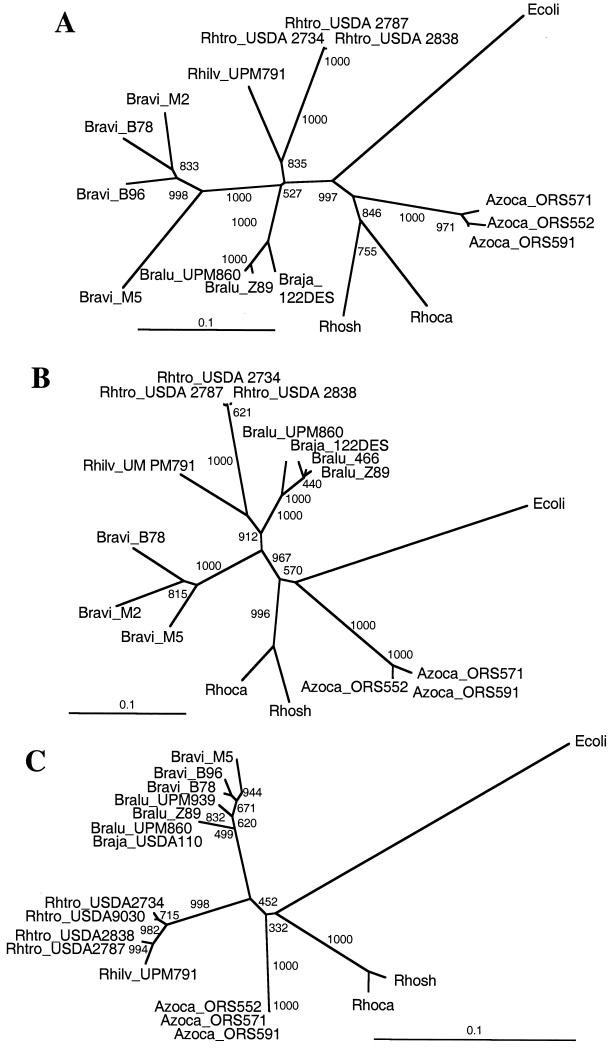

Partial hupS and hupL sequences were obtained from DNA fragments amplified from genomic DNA using the degenerate primer pair hupSL1-hupSL2. DNA sequences of 475 nt were obtained for hupS, covering 44% of the whole gene length. These DNA sequences encode 158 C-terminal amino acid residues of HupS, containing residues critical for hydrogenase activity (47). For hupL, DNA sequences were 453 nt long, spanning 25% of the hupL gene length. These sequences correspond to 151 N-terminal amino acid residues of HupL, including a conserved motif involved in metal center ligation (47). These hupS and hupL nucleotide sequences, along with corresponding data bank sequences from related α-proteobacteria (Rhodobacter capsulatus and R. sphaeroides) and from Escherichia coli hydrogenase 1, were optimally aligned, and phylogenetic trees were constructed by using the neighbor-joining method and the E. coli sequence as the outgroup (Fig. 6A and B). The hupS- and hupL-based trees were very similar, but a higher level of variability was observed for the hupS sequences. Azorhizobium sequences clustered together as a separate group, and they were closer to Rhodobacter than to rhizobial sequences. Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) sequences clustered together with Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and R. tropici, although showing some differences, appeared close to R. leguminosarum. Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) sequences clustered together as a highly heterogeneous group, especially those for hupS, and were clearly separated from the other rhizobia. These results were surprising, since a priori it was expected that Bradyrhizobium and Rhizobium sequences would form respectively homogeneous groups.

FIG. 6.

Phylogenetic trees derived from hup and 16S rDNA sequences of rhizobia. Partial hupS and hupL sequences from Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus), Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna), Rhizobium tropici, Azorhizobium sp., and Azorhizobium caulinodans strains were obtained and aligned with the corresponding sequences from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791, Bradyrhizobium japonicum 122DES, two other α-proteobacteria (Rhodobacter capsulatus and Rhodobacter sphaeroides), and hyaA and hyaB (hydrogenase 1 structural genes) from E. coli (used as the outgroup). Minimum-distance trees were generated for hupS (A) and hupL (B) by using CLUSTALX and TREEVIEW software. A similar tree was constructed from 16S rDNA sequences of the rhizobial strains mentioned above or database 16S rDNA sequences from strains belonging to the same taxa (C). Tree scales are indicated as per site substitutions. Figures at nodes indicate bootstrap values (per 1,000). The accession numbers of the sequences obtained from databases are as follows: R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 (hupS and hupL, gi:1167855; 16S rDNA, AY072787), B. japonicum USDA110 (16S rDNA, gi:534881), 122DES (hupS and hupL, gi:152100), E. coli (hyaA and hyaB, gi:146419; 16S rDNA, gi:174375), R. capsulatus (hupS and hupL, gi:46032; 16S rDNA, gi:1944502), R. sphaeroides (hupS and hupL, gi:4539150; 16S rDNA, gi:303817), R. tropici USDA9030 (16S rDNA, gi:1895079), A. caulinodans ORS571 (16S rDNA, gi:870816). Abbreviations: Azoca, Azorhizobium caulinodans; Braja, Bradyrhizobium japonicum; Bralu, Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus); Bravi, Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna); Ecoli, Escherichia coli; Rhilv, Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae; Rhtro, Rhizobium tropici; Rhoca, Rhodobacter capsulatus; Rhosh, Rhodobacter sphaeroides.

Since the taxonomical characteristics of species within the genus Bradyrhizobium are not well defined (48, 49, 50), it was possible that the observed discrepancies were the result of differences in the genomic backgrounds of the analyzed strains. For that reason, we obtained and compared partial 16S rDNA sequences. A fragment corresponding to the region between positions 20 and 338 in the E. coli 16S rDNA was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA with the primer pair Y1-Y2 (51), cloned, and sequenced. The DNA sequences were aligned, and the most likely phylogenetic tree was derived as described above (Fig. 6C). The results obtained in the comparison of the 16S rDNA sequences were consistent with the taxonomic placement of the different strains. Azorhizobium strains clustered together as a separate group, equally distant from the rhizobial and the Rhodobacter strains. Bradyrhizobium and Rhizobium strains clustered into two well-differentiated groups. Each group was quite homogeneous, especially the Bradyrhizobium group, which showed branches shared by strains nodulating Vigna and Lupinus.

DISCUSSION

This work represents the first attempt to study the genetic composition and organization of hup gene clusters in a wide range of rhizobia. It was promoted by three independent observations: (i) the Hup trait is rare among rhizobia; (ii) when present and functional, hup genes can contribute to an increase in the energy efficiency of rhizobia-legume symbiosis by recycling the hydrogen evolved from the nitrogenase reaction; and (iii) comparison of the sequenced hup clusters from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 and B. japonicum 122DES shows very high sequence and genetic organization conservation but also substantial differences in regulatory genes and in the presence or absence of specific ancillary genes. We reasoned that a comparative study of the different rhizobial hup systems might help clarify the evolution of such systems and also suggest reasons for the paucity of Hup+ strains. Furthermore, efforts from our laboratory to engineer rhizobia for high symbiotic energy efficiency by incorporating the R. leguminosarum hup cluster (3) might benefit from a better understanding of existing rhizobial Hup systems, especially in view of factors limiting symbiotic hydrogenase activity (8, 9) and of the regulatory requirements for expression (11).

In this work, three types of gene probes were used: (i) hupS and hypB, genes necessary for hydrogenase activity (the hupS gene must be present by definition, whereas for hypB, there is room for variability, especially regarding the long histidine-rich tract at the N terminus [30]); (ii) hupE, a gene presently believed to be characteristic of R. leguminosarum alone; and (iii) regulatory genes hoxA and hupUV. Of the two model systems, R. leguminosarum UPM791 lacks hupUV and its hoxA is a pseudogene (11), and B. japonicum 122DES lacks hupE. Genes hupS and hypB were present in all Hup+ strains, although in the case of some Bradyrhizobium strains, such as 32H1 and IM43B, evidence for the presence of a hypB gene could only be obtained by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing (Table 3). Sequence conservation of these hypB DNA fragments with the corresponding regions in B. japonicum ranged from 78 to 85% of identity. These values were significantly lower than the 94% of DNA sequence identity observed in strains that hybridized with the B. japonicum probe. These results emphasize the fact that bradyrhizobial strains very often exhibit high levels of heterogeneity at the nucleic acid level, even though they appear as closely related by most other taxonomic criteria (48, 49, 50), and question the reliability of negative results obtained in Southern blot hybridization experiments with Bradyrhizobium strains. Gene hupE could not be identified in any of the tested strains other than R. leguminosarum, not even in any of the eleven R. tropici Hup+ strains (Table 3). This fact emphasizes the specificity of hupE for the R. leguminosarum hup cluster and the function encoded by this gene for hydrogenase activity in this species. In contrast, different situations were found in the search for regulatory genes hoxA and hupUV (Table 3). Both were present in Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) but absent in R. tropici. In Azorhizobium, the Hup+ strains showed the hupUV genes, but not hoxA, whereas the opposite situation was found for Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna): hoxA could be identified in all strains but not hupUV. Since the hoxA and hupUV genes are involved in the same regulatory pathway, their presence may indicate a mechanism of hup gene activation like that of B. japonicum, whereas in their absence one might speculate that a mode of regulation exists that is similar to that of R. leguminosarum. For the intermediate situations, several circumstances must be considered. We have already discussed the reliability of negative results in the hybridization assays. On the other hand, faint hoxA hybridizing bands might also correspond to cross-hybridization with regulatory genes of the NtrC family to which the hoxA gene belongs (45). In addition, detection of hoxA and hupUV gene sequences does not mean that they are functional; they might correspond to nonfunctional genes, as it is the case for the R. leguminosarum hoxA pseudogene (11). At this point of the investigation, it is difficult to determine the actual explanation of these results and their biological significance. However, the different gene compositions might indicate the presence of hup regulatory pathways alternative to those described for B. japonicum and R. leguminosarum, which would imply a wide range of variation within Hup+ rhizobia with regard to the mechanism of hup gene regulation. The study of these different regulatory adaptations is presently under way in our laboratory and might represent a contribution to efforts aimed at spreading the Hup trait among rhizobial strains of agricultural significance.

It is interesting that the hup sequence divergence within the R. tropici strains was minimal and much lower than that of their 16S rDNAs, despite the fact that the hup genes are encoded in the symbiotic plasmid. This situation is very similar to that observed within R. leguminosarum bv. viciae Hup+ strains, where the hup genes are always present in the symbiotic plasmid (22) and where an extremely high conservation of hup cluster sequences has been documented (D. Fernández, A. Toffanin, J. M. Palacios, T. Ruiz-Argueso, and J. Imperial, submitted for publication). This contrasts sharply with the variability found for Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna), where hup sequences are probably encoded in the chromosome, since no plasmids could be detected in these strains (31). We know very little regarding the mechanisms for gene evolution in rhizobia, but these results suggest that hup genes evolved differently in Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium strains. In addition, Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) hup sequences clustered apart from those of Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) strains in the phylogenetic studies. This anomalous high divergence shown by Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna) hup sequences might reflect the occurrence of independent events of gene acquisition from other soil bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (AGL2001-2295) to T.R.A. and from Programa de Grupos Estrategicos (III PRICYT) of the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid. C. Baginsky is on leave from the Faculty of Agronomy, Universidad de Chile, Santiago. B. Brito was the recipient of a Contrato de Incorporación de Doctores y Tecnólogos del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht, S. L., R. J. Maier, F. J. Hanus, S. A. Russell, D. W. Emerich, and H. J. Evans. 1979. Hydrogenase in Rhizobium japonicum increases nitrogen fixation by nodulated soybeans. Science 203:1255-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arp, D. J. 1992. Hydrogen recycling in symbiotic bacteria, p. 432-460. In G. Stacey, R. H. Burris, and H. J. Evans (ed.), Biological nitrogen fixation. Chapman and Hall, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Báscones, E., J. Imperial, T. Ruiz-Argüeso, and J. M. Palacios. 2000. Generation of new hydrogen-recycling Rhizobiaceae strains by introduction of a novel hup minitransposon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4292-4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beringer, J. 1974. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 84:188-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black, L. K., C. Fu, and R. J. Maier. 1994. Sequences and characterization of hupU and hupV genes of Bradyrhizobium japonicum encoding a possible nickel-sensing complex involved in hydrogenase expression. J. Bacteriol. 176:7102-7106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boivin, C., I. Ndoye, G. Lortet, A. Ndiaye, P. De Lajudie, and B. Dreyfus. 1997. The Sesbania root symbionts Sinorhizobium saheli and S. teranga bv. sesbaniae can form stem nodules on Sesbania rostrata, although they are less adapted to stem nodulation than Azorhizobium caulinodans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1040-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewin, N. J. 1984. Hydrogenase and energy efficiency in the N2 fixing symbionts, p. 179-203. In D. P. S. Verma and T. H. Hohn (ed.), Plant gene research: genes involved in microbe-plant interactions. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 8.Brito, B., J. Monza, J. Imperial, T. Ruiz-Argüeso, and J. M. Palacios. 2000. Nickel availability and hupSL activation by heterologous regulators limit symbiotic expression of the Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae hydrogenase system in Hup− rhizobia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:937-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brito, B., J. M. Palacios, E. Hidalgo, J. Imperial, and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1994. Nickel availability to pea (Pisum sativum L.) plants limits hydrogenase activity of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae bacteroids by affecting the processing of the hydrogenase structural subunits. J. Bacteriol. 176:5297-5303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brito, B., J. M. Palacios, T. Ruiz-Argüeso, and J. Imperial. 1996. Identification of a gene for a chemoreceptor of the methyl-accepting type in the symbiotic plasmid of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1308:7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brito, B., M. Martínez, D. Fernández, L. Rey, E. Cabrera, J. M. Palacios, J. Imperial, and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1997. Hydrogenase genes from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae are controlled by the nitrogen fixation regulatory protein NifA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6019-6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casalot, L., and M. Rousset. 2001. Maturation of the [NiFe] hydrogenases. Trends Microbiol. 9:228-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckhardt, T. 1978. A rapid method for the identification of plasmid desoxyribonucleic acid in bacteria. Plasmid 1:584-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans, H. J., S. A. Russell, F. J. Hanus, and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1988. The importance of hydrogen recycling in nitrogen fixation by legumes, p. 777-791. In R. J. Summerfield (ed.), World crops: cool season food legumes. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, Mass.

- 15.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu, C., S. Javedan, F. Moshiri, and R. J. Maier. 1994. Bacterial genes involved in incorporation of nickel into a hydrogenase enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5099-5103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goormachtig, S., M. Valerio-Lepiniec, K. Szczyglowski, M. Van Montagu, M. Holsters, and F. J. de Bruijn. 1995. Use of differential display to identify novel Sesbania rostrata genes enhanced by Azorhizobium caulinodans infection. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 8:816-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hynes, M. F., R. Simon, and A. Pühler. 1985. The development of plasmid-free strains of Agrobacterium tumefaciens by using incompatibility with a Rhizobium meliloti plasmid to eliminate pAtC58. Plasmid 13:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert, G. R., M. A. Cantrell, F. J. Hanus, S. A. Russell, K. R. Haddad, and H. J. Evans. 1985. Intra- and interspecies transfer and expression of Rhizobium japonicum hydrogen uptake genes and autotrophic growth capability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:3232-3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert, G. R., A. R. Harker, M. A. Cantrell, F. J. Hanus, S. A. Russell, R. A. Haugland, and H. J. Evans. 1987. Symbiotic expression of cosmid-borne Bradyrhizobium japonicum hydrogenase genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:422-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyva, A., J. M. Palacios, J. Murillo, and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1990. Genetic organization of the hydrogen uptake (hup) cluster from Rhizobium leguminosarum. J. Bacteriol. 172:1647-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leyva, A., J. M. Palacios, and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1987. Conserved plasmid hydrogen-uptake (hup)-specific sequences within Hup+ Rhizobium leguminosarum strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:2539-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Romero, E., L. Segovia, F. M. Mercante, A. A. Franco, P. Graham, and M. A. Pardo. 1991. Rhizobium tropici, a novel species nodulating Phaseolus vulgaris L. beans and Leucaena sp. trees. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:417-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minguez, I., and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1980. Relative energy efficiency of nitrogen fixation by nodules of chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.) produced by different strains of Rhizobium. Cur. Microbiol. 4:169-171. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murillo, J., A. Villa, M. Chamber, and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1989. Occurrence of H2-uptake hydrogenases in Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) and their expression in nodules of Lupinus spp. and Ornithopus compressus. Plant Physiol. 89:78-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navarro, R. B., A. A. T. Vargas, E. C. Schröder, and P. van Berkum. 1993. Uptake hydrogenases (Hup) in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) symbioses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:4161-4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Gara, F., and K. T. Shanmugam. 1976. Regulation of nitrogen fixation by rhizobia: export of fixed nitrogen as NH4+. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 437:313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page, R. D. 1996. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palacios, J. M., J. Murillo, A. Leyva, G. Ditta, and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1990. Differential expression of hydrogen uptake (hup) genes in vegetative and symbiotic cells of Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 221:363-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rey, L., J. Murillo, Y. Hernando, E. Hidalgo, E. Cabrera, J. Imperial, and T. Ruiz-Argüeso. 1993. Molecular analysis of a microaerobically induced operon required for hydrogenase synthesis in Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae. Mol. Microbiol. 8:471-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reyes, P. 1990. Estudio de las actividades hidrogenasa en Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Bradyrhizobium sp. (Vigna). Ph.D. thesis. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

- 32.Rinaudo, G., M. P. Fernandez, A. Effosse, B. Picard, and R. Bardin. 1993. Enzyme polymorphism of Azorhizobium strains and other stem- and root-nodulating bacteria isolated from Sesbania rostrata. Res. Microbiol. 144:55-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruiz-Argüeso, T., F. J. Hanus, and H. J. Evans. 1978. Hydrogen production and uptake by pea nodules as affected by strains of Rhizobium leguminosarum. Arch. Microbiol. 116:113-118. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruiz-Argüeso, T., R. J. Maier, and H. J. Evans. 1979. Hydrogen evolution from alfalfa and clover nodules and hydrogen uptake by free-living R. meliloti. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 37:582-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruiz-Argüeso, T., J. M. Palacios, and J. Imperial. 2000. Uptake hydrogenases in root nodule bacteria, p. 489-507. In E. W. Triplett (ed.), Prokaryotic nitrogen fixation. A model system for the analysis of a biological process. Horizon Scientific Press, Norfolk, England.

- 36.Ruiz-Argüeso, T., J. M. Palacios, and J. Imperial. 2001. Regulation of the hydrogenase system in Rhizobium leguminosarum. Plant Soil 230:49-57. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Schubert, K. R., J. A. Engelke, S. A. Russell, and H. J. Evans. 1977. Hydrogen reactions of nodulated leguminous plants. I. Effects of rhizobial strains and plant age. Plant Physiol. 60:651-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schubert, K. R., and H. J. Evans. 1976. Hydrogen evolution: a major factor affecting the efficiency of nitrogen fixation in nodulated symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:1207-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stam, H., A. H. Stouthamer, and H. W. van Verseveld. 1987. Hydrogen metabolism and energy costs of nitrogen fixation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 46:73-92. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stam, H., H. W. van Verseveld, W. de Vries, and A. H. Stouthamer. 1984. Hydrogen oxidation and efficiency of nitrogen fixation in succinate-limited chemostat cultures of Rhizobium ORS571. Arch. Microbiol. 139:53-60. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL-X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Berkum, P., R. B. Navarro, and A. A. T. Vargas. 1994. Classification of the uptake hydrogenase-positive (Hup+) bean rhizobia as Rhizobium tropici. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:554-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Soom, C., I. Lerouge, J. Vanderleyden, T. Ruiz-Argueso, and J. M. Palacios. 1999. Identification and characterization of hupT, a gene involved in negative regulation of hydrogen oxidation in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J. Bacteriol. 181:5085-5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Soom, C., C. Verreth, M. J. Sampaio, and J. Vanderleyden. 1993. Identification of a potential transcriptional regulator of hydrogenase activity in free-living Bradyrhizobium japonicum strains. Mol. Gen. Genet. 239:235-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vincent, J. M. 1970. A manual for the practical study of root-nodule bacteria. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 47.Volbeda, A., M.-H. Charon, C. Piras, E. C. Hatchikian, M. Frey, and J. C. Fontecilla-Camps. 1995. Crystal structure of the nickel-iron hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas. Nature (London) 373:580-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willems, A., R. Coopman, and M. Gillis. 2001. Comparison of sequence analysis of 16S-23S rDNA spacer regions, AFLP analysis and DNA-DNA hybridizations in Bradyrhizobium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:623-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willems, A., R. Coopman, and M. Gillis. 2001. Phylogenetic and DNA-DNA hybridization analyses of Bradyrhizobium species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:111-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willems, A., F. Doignon-Bourcier, J. Goris, R. Coopman, P. de Lajudie, P. De Vos, and M. Gillis. 2001. DNA-DNA hybridization study of Bradyrhizobium strains. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1315-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young, J. P. W., H. L. Downer, and B. D. Eardly. 1991. Phylogeny of the phototrophic Rhizobium strain BTAi1 by polymerase chain reaction-based sequencing of a 16S rRNA gene segment. J. Bacteriol. 173:2271-2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]