Abstract

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), e.g. toll receptors (TLRs) that bind ligands within the microbiome have been implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer. LPS is a ligand for two TLR family members, TLR4 and RP105 which mediate LPS signaling in B cell proliferation and migration. Although LPS/TLR/RP105 signaling is well-studied; our understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms controlling these PRR signaling pathways remains incomplete. Previous studies have demonstrated a role for PTEN/PI-3K signaling in B cell selection and survival, however a role for PTEN/PI-3K in TLR4/RP105/LPS signaling in the B cell compartment has not been reported. Herein, we crossed a CD19cre and PTENfl/fl mouse to generate a conditional PTEN knockout mouse in the CD19+ B cell compartment. These mice were further crossed with an IL-14α transgenic mouse to study the combined effect of PTEN deletion, PI-3K inhibition and expression of IL-14α (a cytokine originally identified as a B cell growth factor) in CD19+ B cell lymphoproliferation and response to LPS stimulation. Targeted deletion of PTEN and directed expression of IL-14α in the CD19+ B cell compartment (IL-14+PTEN−/−) lead to marked splenomegaly and altered spleen morphology at baseline due to expansion of marginal zone B cells, a phenotype that was exaggerated by treatment with the B cell mitogen and TLR4/RP105 ligand, LPS. Moreover, LPS stimulation of CD19+ cells isolated from these mice display increased proliferation, augmented AKT and NFκB activation as well as increased expression of c-myc and cyclinD1. Interestingly, treatment of LPS treated IL-14+PTEN−/− mice with a pan PI-3K inhibitor, SF1126, reduced splenomegaly, cell proliferation, c-myc and cyclin D1 expression in the CD19+ B cell compartment and normalized the splenic histopathologic architecture. These findings provide the direct evidence that PTEN and PI-3K inhibitors control TLR4/RP105/LPS signaling in the CD19+ B cell compartment and that pan PI-3 kinase inhibitors reverse the lymphoproliferative phenotype in vivo.

Keywords: PTEN, AKT, TLR, CD19, NF-κB, PI-3 kinase, B cells, lymphoid

Introduction

B cells are central elements in the adaptive immune response to pathogens. Antigen (Ag) recognition through the BCR and CD19 drives B cell activation and differentiation. B cells also display elements of innate immunity; they express several proteins of the PRR/TLR family including the LPS receptors, TLR4 and RP105 (CD180) [1–3] through which these cells recognize and respond to pathogen-associated ligands [3, 4]. TLR stimulation of B cells enhances their Ag presentation capacity and promotes cytokine secretion, cell proliferation, and differentiation into Ab secreting cells. TLR4 and RP105, are two of the most extensively studied TLRs, which recognizes gram negative bacterial LPS as its prototype agonist, in the presence of MD-2 and this recognition is facilitated by CD14 and LPS-Binding Protein (LBP) [2, 5]. TLR4 signaling utilizes both “MyD88-dependent” and “MyD88-independent” signaling pathways which require receptor dimerization, adapter recruitment, and the activation of specific kinases and transcription factors and result in inflammatory gene expression. RP105 is selectively expressed in mature CD19+ B cells, signals separate from MyD88, and uses CD19 as a coreceptor to signal through lyn, Vav, PI-3K, AKT, IKKα and BAFF-R to activate LPS dependent B cell proliferation in mantle zone (MZ) B cells[1, 2]. The activation of either of these pathways allows NF-κB to diffuse into the cell nucleus and activate transcription and consequent induction of inflammatory cytokines. In addition to the expression of inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB also promotes cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of c-myc and cyclin D1 [6, 7]. The role of TLR4 signaling in enhancing B lymphocyte trafficking into lymph nodes, B cell proliferation, polarization, migration and directionality [8, 9] is well-known.

Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), a lipid phosphatase that dephosphorylates PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4,5)P2, is known to antagonize phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI-3K) [10, 11]. The balance between PTEN and PI-3K determines PI(3,4,5)P3 levels and opposing effects on growth and cell survival [12]. PI(3,4,5)P3 is thought to mediate these effects by inducing phosphorylation/activation of the PDK1 and AKT kinases, which enhances the PIP3-PI-3K/AKT survival pathway [13]. The role of PTEN/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI-3K) in mediating TLR4 signaling has been studied in endothelial cells, macrophages and liver [14–20]. Li et al, has suggested the connection between MyD88 and PI-3K signaling pathways and showed that MyD88 TIR domain blocked LPS induced AKT activation in endothelial cells [14]. On the same note, work from other labs, reported the role of PI-3K in TLR4-mediated activation of NF-κB and COX-2, as well as IL-6, MCP-1, IFN-inducible protein 10, IL-12, and IL-10 [14, 21]. Recently, Luyendyk et al. [22] used Pik3r1−/− mice and PTEN−/− mice to study the role of PI-3K in TLR4 signaling and concluded that PI-3K plays negative role in TLR4 signaling in macrophages. In agreement with these results, Cao et al has reported that PTEN supports TLR4 signaling in murine peritoneal macrophages [19]. Recently, Kamo et al has provided a novel regulatory link between the PTEN mediated AKT/-β catenin/Foxo1 and TLR4 pathway and provide a mechanism for β-catenin–mediated immunomodulation in IR-stressed livers [20].

PTEN/PI-3K is a central signal transduction axis controlling normal B cell homeostasis and influencing normal B cell functional responses including the development of B cell subsets, antigen presentation, immunoglobulin isotype switch, germinal center responses and maintenance of B cell anergy [23–28]. Recent studies reported the augmented activation of PI-3K signaling in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) [29, 30]. In contrast, studies conducted by Anzelon et al. suggest that loss of PTEN alone in the B cell compartment does not result in transformation of B cells [28]. The deletion of PTEN and SHIP in the CD19+ compartment resulted in the formation of malignant lymphomas mostly of the MZ phenotype [31]. The IL-14α-transgenic mice is an excellent model for human Sjogren’s disease, an autoimmune disease associated with mature B cell infiltration of the submandibular and parotid glands, hypergammaglobulinemia, pulmonary interstitial lung disease and, as with the CD19cre driven PTEN/SHIP−/− model, the development of mature B cell lymphomas in the mantle zone (MZ) compartment[32]. The IL14α transgenic mice were reported by Shen et al to develop CD5+, CD19+, SIgM+, monoclonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangements consistent with mature B cell lymphomas at age of 14–18 months, also a mantle cell phenotype. [32]. Although IL14α has been linked to human lymphoma and autoimmune disease, almost nothing is known about IL14α signaling in B cells. We hypothesized that combined deletion of PTEN and expression of IL-14α in CD19+ B cell compartment will augment B cell proliferation in mature CD19+ B cell compartment and lead to the development of a distinct B cell lymphoma. In the present study, we used a CD19Cre × PTENfl/fl cross in combination with IL-14 transgenesis to evaluate the role of IL-14, PTEN and PI-3K inhibitor therapeutics in LPS-induced lymphoproliferation in the CD19+ B cell compartment. Herein, we provide experimental evidence that the targeted deletion of PTEN combined with the directed expression of IL-14α in LPS stimulated CD19+ B cells leads to the activation of AKT, splenomegaly and highly altered spleen morphology with no distinct red and white pulp. Furthermore, CD19+ cells isolated from IL-14+; PTEN−/− mice show increased LPS induced AKT activation, which leads to increased levels of cyclinD1 and c-myc and augmented NF-κB activation. These findings establish a central role of PTEN and PI-3K in controlling LPS signaling in CD19+ B cells and suggest that PI-3K inhibitors may have therapeutic activity in the control of this phenotype where the microbiome and inflammation impact mature B cell-mediated lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity.

Methods

Mice and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment

IL-14α, PTENflox/flox (PTENfl/fl) and CD19-Cre mice were obtained from Dr. Ambrus and the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), respectively. All procedures involving animals were approved by the University of California San Diego Animal Care Committee, which serves to ensure that all federal guidelines concerning animal experimentation are met. The PTEN floxed homozygotes were generated in Balb/c FVB mice [33], and extensively backcrossed into the C57BL/J genetic background (>100 backcrosses). IL-14α transgenic mice were generated using pEμSR vector which promotes gene expression predominantly in the B cell compartment. The IL-14α transgenic mice [34] were mated to CD19-Cre mice [35] and PTENfl/fl mice, to produce a triple transgenic genotype targeting PTEN loss and IL-14α to CD19+ cells. Four genotypes and phenotypes used in this study were: PTENfl/fl (WT, control), IL-14α × PTENfl/fl (IL-14+), PTENfl/fl × CD19cre (PTEN−/−), IL-14+ × CD19cre (IL-14+PTEN−/−) (Fig. 1A). All mice used were between 10–20 wk of age and mice of different genotypes have been bred separately for littermate controlled experiments. For in vivo stimulation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), animals were injected subcutaneously with 50 μg of LPS (LPS from E. coli 055: B5, L-2880; Sigma, St Louis, MO) in 100 μl PBS or with 100 μl of PBS alone for 14 days.

Fig. 1.

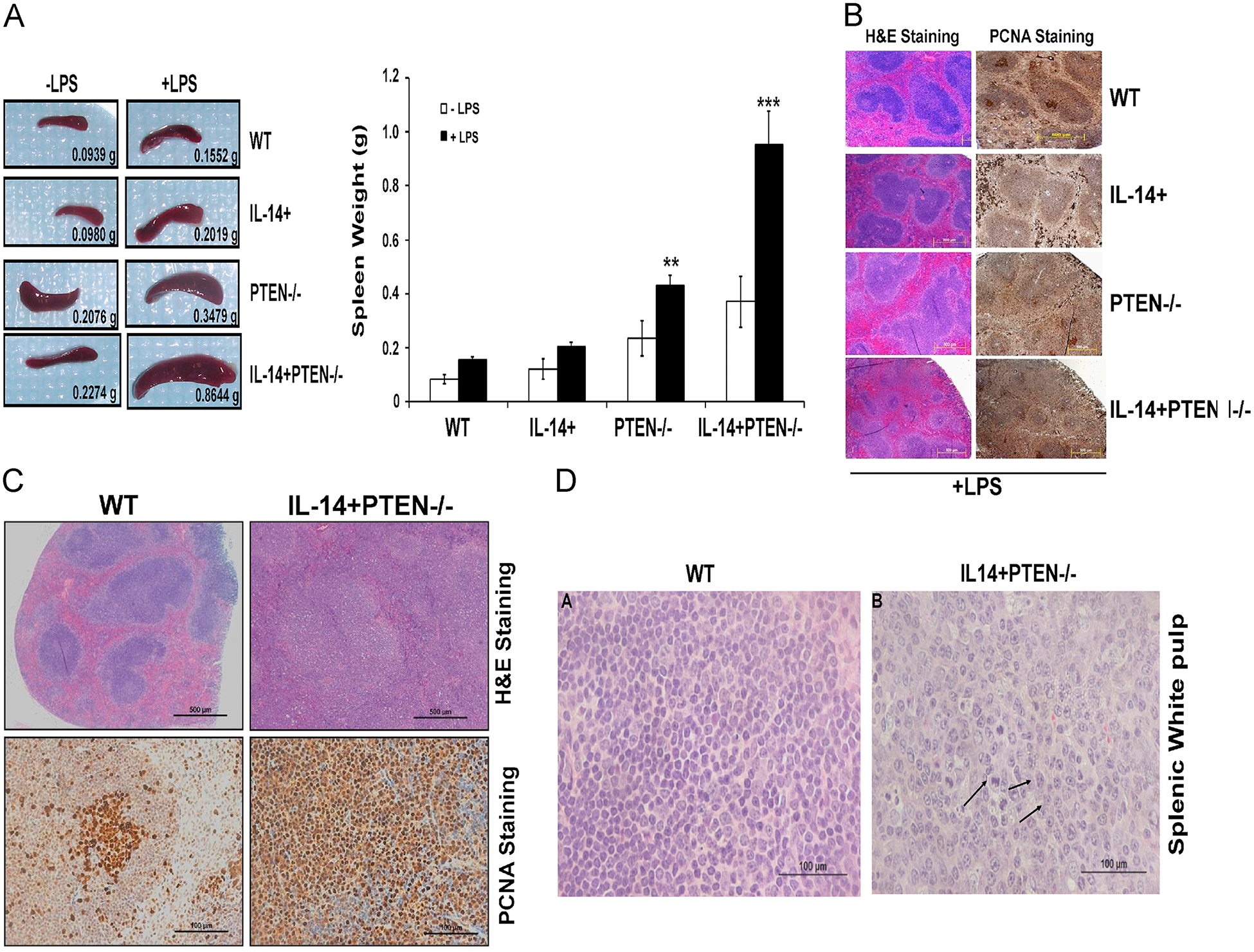

PTEN loss and directed expression of IL-14α leads to splenomegaly and altered spleen morphology. (A) Baseline and LPS stimulation effects on spleen weight in mice of all four genotypes. Mice of all four genotypes were injected with 50 μg of LPS in 100 μl PBS or with 100 μl of PBS alone, for 14 days. Both PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− spleens shows moderate splenomegaly even in absence of LPS while LPS injections lead to extreme splenomegaly in the triple transgenic mice. Left panel shows representative images of spleens isolated from different genotypes and right panel shows bar diagram for spleen weight isolated from mice of different genotypes. (B) Morphology of spleens from 12 week old transgenic mice, with or without LPS injections (50 μg for 14 days). Spleens from all the genotypes were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded and used for H & E staining (40x) and PCNA staining (200x). (C) Enlarged image shown in B highlighting H & E and PCNA staining for WT vs IL-14+PTEN−/− mice. WT mice shows well-defined zones of white and red pulp with distinct germinal centers (GCs) and marginal zones (MZs), while IL-14+PTEN−/− mice showed loss of normal spleen architecture; white pulp has irregular contours and is continuous with red pulp. GCs and MZs are indistinct and red pulp shows increased vascularity. (D) Histology of splenic white pulp from 12 week old IL-14+PTEN−/− transgenic mice following LPS injections. H & E staining of spleens isolated form WT showing normal morphology and histology of cells. While histology of spleens isolated from IL-14+PTEN−/− indicates lymphoproliferation, as indicated by larger-sized cells with many mitotic figures (arrows). Prominent nucleoli are seen in some cells. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments. Graphs present mean ±SEM of 6–8 mice. *P <0.05, **P <0.01 and ***P <0.001 vs. WT, as determined using t-test.

PCR analysis of IL-14α, Cre and PTEN genotypes

Total DNA was isolated from tail snips and genotypes were confirmed for each of the following by standard PCR methods, using the designated primers: PTENfl/fl: forward 5’ACT CAA GGC AGG GAT GAG C-3’, reverse 5’GCC CCG ATG CAA TAA ATA TG-3’; IL-14α: forward 5’AGG CTT GTA CGG AAG TGT TAC TTC-3’, reverse 5’CAG CCT GCA CCT GAG GAG TGA ATT-3’; CD19-Cre: forward 5’ GCG GTC TGG CAG TAA AAA CTA TC-3’, reverse 5’GTG AAA CAG CAT TGC TGT CAC TT; CD19-WT: forward 5’ CCT CTC CCT GTC TCC TTC CT-3’, reverse 5’ TGG TCT GAG ACA TTG ACA ATC A-3’ (all from IDT, Coralville IW).

Isolation of CD19+ splenic cells and flow cytometric analysis

CD19+ cells were isolated from total splenocytes of 10–20 week-old mice using CD19 MicroBeads and MACS Column Technology (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In order to determine the percentage of CD19+ cells in total splenocytes, flow cytometry was performed on CD19+ and CD19− cells labeled with FITC conjugated B220 and PE conjugated CD45 mAbs (BD Biosciences). For analysis of the percentage of IgM/IgD and CD21/CD23 positive cells of each of the four genotypes, total splenocytes were labeled with FITC-conjugated IgM, IgD, CD21 or CD23 mAbs and B220-PE-mAb (BD Biosciences), or with the isotype controls (IgG2a or IgG2b). Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a BD FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson).

Histological analysis of splenic sections

For formalin fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections, tissues were fixed immediately after harvest in 10% PBS buffered neutral formalin (Polysciences Inc.) for 24–48 h and stored in 95% ethanol. Paraffin embedding, sectioning, H&E and Ki67 staining were performed by the UCSD Cancer Center. H&E sections of spleens from all four groups were examined by a hematopathologist. For immunohistochemical detection of PCNA (Cell Signaling), cyclin D1 (Cell Signaling) and c-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), Vectastain ABC kit (Vector) was used. For heat-induced epitope retrieval, Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20 (pH 9.0) was used. Images were visualized using an Olympus AX70 microscope (Melville, NY) and captured with an Olympus DP70 camera.

Immunoblotting

For immunoblotting, total splenocytes, CD19+ and CD19− cells were cultured in RPMI containing 10% FBS and stimulated with or without LPS (50 μg/ml) for 30 min. Cells were collected, washed with PBS and lysed using cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technology. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated using NE-PER nuclear protein extraction kit (Pierce). Protein content of cleared lysates was measured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and equal protein amounts were resolved on 12.5% Criterion Precast Tris-HCl gels (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. . -The antibodies for PTEN, HDAC, Phospho-p44/42 MAPK, p44/42, , pIKKα/β (S176/180), pAKT- Ser 473 , and Akt were from Cell Signaling, Cre-recombinase was obtained from Millipore, β-actin from Sigma, pIKKα/β (T 23), IKKα/β, pIKBα, IKBα, p-NIK, NIK, p65, p52, p50, cyclin D1 and c-myc are from Santa Cruz.

Real time PCR.

CD19+ cells isolated from all four genotypes were stimulated with or without LPS (50 μg/ml) for 24 h and used for RNA extraction using the Qiagen RNAeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was prepared from 1 μg RNA sample using iscript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). cDNA (2 μL) was amplified by RT-PCR reactions with 1× SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in 96-well plates on an CFX96 Real time system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), using the program: 5 min at 95°C, and then 40 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 1 min at 58°C and 30 sec at 72°C. Validated primer sets for TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR6, c-Myc, Cyclin D1 and GADPH were used (Real Time Primers, Elkins Park, PA). Specificity of the produced amplification product was confirmed by examination of dissociation reaction plots. Relative expression levels were normalized to GAPDH expression according to the formula < 2^(Ct gene of interest-Ct Gapdh) > [36].

Splenocyte proliferation in culture and cell cycle analysis

CD19+, CD19− and total splenocytes were plated in triplicate at 105 cells/well in a 96 well plate in RPMI + 10% FBS containing 0, 1, 10 and 100 μg/ml of LPS (Sigma). After 24h, 1 μCi/well of [methyl]- 3H thymidine (Perkin Elmer) was added for four hours. Cells were lysed using a Skatron semi-automatic cell harvester (Sterling, VA) and membranes were counted on an LS6500 scintillation counter (Beckman). For cell cycle analysis, 2 × 106 CD19+ cells isolated from all four genotypes were cultured in RPMI containing 10% FBS and stimulated with 50 μg/ml of LPS (Sigma) for 24 hrs. Cells were collected and treated with RNase A followed by staining with propidium iodide (PI) (5 μg/ml). DNA content was analyzed with FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). FCS Express program was used for data analysis.

NF-kB luciferase activity

CD19+ cells from spleens of all genotypes were isolated using MACS magnetic separator. Cells were plated at a density of 6 × 106 in 10 cm dish and stimulated with 50 μg/ml LPS. After 24 hr of stimulation, cells were transiently transfected with 2 μg NF-kB-luciferase and β-galactosidase expression vectors using Amaxa mouse B cell Nucleofactor kit (Lonza). β-galactosidase assay was performed to correct for transfection efficiency. The luciferase activity was determined using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Treatment with SF1126

To study the effects of the PI-3K, SF1126 on PTEN and IL-14 dependent CD19+ B cell proliferation, biochemistry and biology in vivo, WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice were first treated with 50 μg/ml LPS for 14 days followed by random separation into two groups: Group 1 was given vehicle (untreated) and Group 2 was given 50 mg/kg SF1126 subcutaneously once daily for 21 days. SF1126 is a pan PI-3K inhibitor which has completed Phase I human clinical trials in solid tumors and B cell malignancy [37, 38].

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated from CD19+ cells from three mice of each of the four genotypes using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Whole Genome BeadChip method was used for microarray analysis by the Emory Biomarker Service Center of the Winship Cancer Institute. Mouse WG-6 v.2 Expression Bead Chips were used to analyze the twelve samples following Agilent BioAnalyzer quality control. An initial unsupervised grouping of array-clustering was applied to the gene expression data set, and an Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems) was used to analyze fold-change of statistically significant networks, setting the minimum fold change at 1.5. The False Discovery Rate (FDR) was < 1%.

Results

Generation of PTEN null IL-14α+ mouse model for the study of CD19+ B-cell biology

In order to generate a mouse model for the study of the role of PTEN in lymphoproliferation as well as in the regulation of LPS signaling in B cells, we generated a CD19 directed PTEN deficient mouse model. CD19cre × PTENfl/fl mice were crossed with IL-14α transgenic mice, which resulted in IL-14+/PTEN−/− genotype in the B cell compartment (Supplementary Fig. S1A). The genotypes used in this study WT, IL-14 +, PTEN−/−, and IL-14+PTEN−/− are represented in Fig. 1A. Using a CD19Cre transgenic model of directed PTEN deletion, we were able to demonstrate the loss of PTEN and the presence of CD19Cre at both the genomic DNA level (Supplementary Fig. S1B) as well as by Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. S1C). The IL-14α transgene is also demonstrable at the genomic level, as well as by mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. S1B & D). Thus, conditional deletion of PTEN and expression of IL-14 was achieved efficiently in IL-14+PTEN −/− mice, allowing for a comparative analysis of B cell function with PTENfl/fl mice as a normal control.

The targeted deletion of PTEN and directed expression of IL-14α in CD19+ B cells lead to splenomegaly and altered splenic cytohistomorphology

We first examined the effects of PTEN deletion and/or IL-14 transgenesis in the B cell compartment on baseline spleen weight and histopathology. Interestingly, we noticed that deletion of PTEN either alone (PTEN−/−) or combined with the expression of IL-14 (IL14+PTEN−/−) leads to increased spleen size. (Fig. 1A). In contrast, expression of IL14α was not associated with a baseline increase in spleen size or alteration in splenic architecture. In order to examine the role of PTEN and IL14α in B cell biology, we treated mice of all genotypes with LPS, a TLR4/RP105 ligand and noticed that loss of PTEN combined with the directed expression of IL-14α in CD19+ cells leads to marked splenomegaly (Fig. 1A). We evaluated the effect of LPS stimulation on the morphology of spleen and found that spleens of WT and IL-14+ mice, displayed well-defined zones of white and red pulp as evidenced by H&E staining (Fig. 1B). Under conditions of LPS stimulation splenic histology in WT mice is normal whereas the IL14α Tg mice display augmented proliferation in the red pulp region. Distinct germinal centers (GCs) and marginal zones (MZs) are evident (Fig. 1B) in both WT and IL14α Tg mice. In contrast, the spleens of PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice treated with LPS have marked splenomegaly and highly altered splenic morphology and loss of normal architecture of distinct red and white pulp due to expansion of marginal zone B cells (Fig. 1B). In order to explore the effects of LPS on proliferation of splenocytes in the different genotypes we performed IHC on spleens for the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Fig. 1B shows that PCNA primarily stains only the germinal center cells in WT mice while hyperproliferation is evident throughout the spleen in both red and white pulp in PTEN −/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice. Fig. 1C shows a higher power magnification of the H & E and PCNA stained slides for WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice. PCNA staining in IL-14+PTEN−/− demonstrates increased proliferation index in both red and white pulp regions (Fig. 1C). In order to gain further insight into the cellular structure of spleen, an examination of the white pulp of spleen was performed. The splenic white pulp of WT mice, treated with LPS, demonstrate normal cellular structure, with small lymphoid cells (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the splenic white pulp of the IL-14+PTEN−/− mice showed an expansion of marginal zone B cells and display classic features of lymphoproliferation, following LPS treatment (Fig. 1D) which included enlarged cells, many containing mitotic figures (arrows), expanded cytoplasm and the presence of prominent nucleoli.

Reversal of marginal zone B-cell proliferation in PTEN null mice by directed expression of IL-14

We used flow cytometry to investigate the number of marginal zone (MZ) and follicular mature (FM) B cell populations isolated from these four genotypesB220+ B cells were gated from total splenocyte population isolated from the four genotypes and analyzed by the proportion of IgM/IgD+ and CD21/CD23+ cells. Previous reports suggest that MZ cells are defined as IgMhi/IgDlo and CD21hi/CD23lo, while FM cells are defined as IgMhi/IgDhi and CD21hi/CD23hi [28]. Our results demonstrate that 79–90% of cells of all transgenic groups expressed IgM, while 80–87% of cells from three of the transgenic groups expressed IgD. In contrast, the expression of IgD was reduced to 46% in the PTEN−/− group. Similarly, CD23 was reduced to 29% in this group, while its expression ranged from 68–83% in the other transgenics (Supplementary Fig. S1). These results suggest that PTEN−/− spleens contain a larger proportion of IgMhi/IgDlo and CD21hi/CD23lo MZ B cells, while the IL-14+ PTEN null transgenics contain a larger number of FM B cells. It is interesting, that introduction of IL-14α transgene into the PTEN null B cell genetic background reversed the MZ phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S2).

LPS stimulation induced proliferation and cell growth of CD19+ cells isolated from IL14α Tg and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice

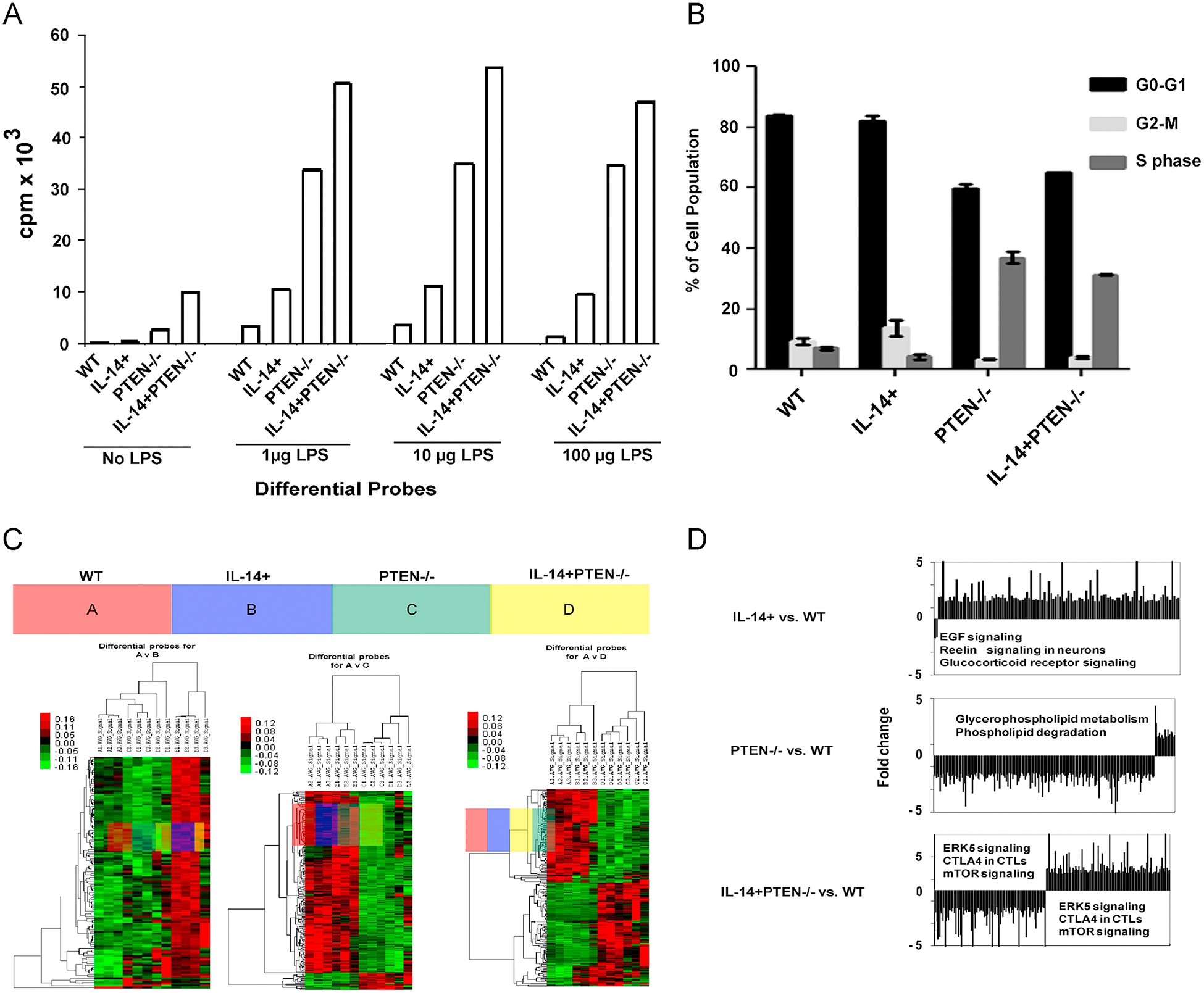

In order to examine, the effect of LPS on the proliferation of B cells, 12 to 15 wk old mice of all four genotypes were injected with either PBS or LPS, and the CD19+ cells were analyzed across the a range of LPS concentrations in vitro (0–100 μg/ml). The LPS-injected animals demonstrated about a two-fold increase level of proliferation in the CD19+ compartment over the untreated animals (Fig. 2A). PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− CD19+ B cells demonstrated a more robust response to 24h in vitro LPS stimulation, with a peak response at 10 μg/ml (Fig. 2A). The proliferative response of CD19+ B cells isolated from the IL-14+PTEN−/− mice was higher than that of the PTEN−/− (Fig. 2A). We next explored, if stimulating CD19+ cells with LPS, has any effect on cell cycle. We observed that CD19+ cells isolated from WT mouse spleens showed cell cycle arrest with a proportional increase in G0–G1 and a decrease in the number of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 2B). While cells isolated from PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice showed an increase percentage of cells in S phase and a decreased number of cells in G0 phase. From these combined data, we conclude that PTEN regulates the proliferative response of CD19+ B cells to LPS stimulation in vivo. These results support the increased proliferation of CD19+ cells B cells observed in PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice.

Fig. 2.

LPS stimulation induces proliferation and cell growth in IL-14+PTEN−/− mice (A) CD19+ cells isolated from 12–15 week old mice of all genotypes were stimulated with 0, 1, 10 and 100 μg/ml LPS. After 24h, 1 μCi/well of [methyl]- 3H thymidine (Perkin Elmer ) was added for four hours. Cells were lysed and membranes were counted on an LS 6500 scintillation counter (Beckman). The p-values for proliferation of PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice are significant (< 0.05) as compared to WT in 1, 10 and 100 μg/ml LPS stimulations. (B) Cell cycle analysis data on the CD19+ cells isolated from all four genotypes. CD19+ cells were cultured in RPMI containing 10% FBS and stimulated with 50 μg/ml of LPS for 24 hours. Cells were collected and DNA content was analyzed with FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). (C) Microarray data analysis of CD19+ cells isolated from the four genotypes. Heat maps were generated using hierarchical cluster analysis to show distinct expression patterns in splenic CD19 + lymphocytes between the WT (A), IL-14+ group (B), PTEN−/− group (C) and IL-14+PTEN−/− group (D). The intensity values were Log2 transformed, centered by the mean of individual genes across all 4 samples, and then subjected to cluster analysis for generating the heat map. The color bar was extracted to show the color contrast level of the heat map. Red and green indicate high expression level and low expression level, respectively. By comparison of differential probes for A, B, C and D, it can be seen that approximately half the genes expressed in (D) are upregulated and about half are downregulated, relative to those of (A). In contrast, virtually all the genes in (B) are upregulated, and virtually all the genes in (C) are downregulated, relative to those of (A). (D) Graphical representation of microarray data analysis. Top panel: The three most significantly altered canonical pathways in (B) relative to (A) are 1. EGF signaling (p = 1.45E-03), 2. reelin signaling in neurons (p = 5.5E-03) and 3. glucocorticoid receptor signaling (p = 6.76E-03). Middle panel: The two most significantly altered canonical pathways in (C) relative to (A) are 1. glycerophospholipid metabolism (p = 4.17E-03) and 2. phospholipid degradation (p = 5.25E-03). Bottom panel: The three most significantly altered canonical pathways in (D) relative to (A) are 1. ERK5 signaling (p = 3.55E-03), 2. CTLA4 signaling in CTLs (p = 9.33E-03) and 3. mTOR signaling (p = 1.07E-02). Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments. Graphs in Fig. 3 A present mean ±SEM of 3–4 mice.

In order to gain further insight into the signaling pathways altered by deleting PTEN and expressing IL-14 in the B cell compartment, microarray studies were performed on all the four genotypes and data was analyzed relative to mRNA levels in the WT control mice. Interestingly, the expression of IL-14 leads to increase in EGF signaling, reelin and glucorticoid receptor signaling (Fig. 2C & D). The deletion of PTEN alone was associated with increased glycerophospholipid metabolism and phospholipid degradation (Fig. 2C &D). Finally, the targeted deletion of PTEN and directed expression of IL-14 leads to increased expression of ERK and mTOR signaling and increased expression of CTLA4 in CD19+ B cells.

LPS stimulation increased AKT activation in PTEN null and IL-14 expressing CD19+ cells

We next explored the expression of TLR receptors in these different genotypes stimulated with LPS. CD19+ cells from 12 wk old mice were isolated, and levels of mRNA for TLR-1, 2, 3 and 4 were analyzed by real time PCR to ascertain if differences in these levels across genotypes could explain the range of responses +/− 50 μg/ml LPS stimulation. Levels for all four TLRs were found to be similar across the genotypes. Interestingly, we found that LPS stimulation induced an increase in TLR3 expression and a slight increase in TLR4 expression in the PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− CD19+ B cells (Fig. 3A). Previous reports show the activation of PI-3K in TLR4 signaling [16–18, 39]. Hence, we examined the effect of LPS stimulation on PI-3K-AKT signaling in the different genotypes. 50 μg/ml LPS stimulation of CD19+ cells from the IL-14+PTEN−/− mice leads to increased phosphorylation of AKT as compared to control CD19+ B cells (Fig.4B). Most notably, levels of pAKT were increased in both IL-14 transgene-derived and PTEN−/− CD19+ B cells as compared to controls (Fig. 3B), which raises the possibility that both the directed expression of IL-14α or PTEN deletion in B cells induces signaling through PI-3K-AKT signaling pathway. The results suggest a role for IL14α and PTEN/PI-3 kinase in LPS signaling in CD19+ B cell compartment.

Fig. 3.

LPS stimulation of TLR4/RP105 activates AKT in CD19+ cells. (A) Real time PCR analysis of TLR1, 2, 4 and 6 in LPS stimulated or unstimulated CD19+ cells isolated from all four genotypes. CD19+ cells isolated from all the genotypes were stimulated with 50 μg/ml LPS for-24hrs followed by RNA extraction and real time PCR analysis. Results represent the means +/− SD of two independent experiments. (B) Western blot analysis demonstrated the activation of AKT in IL14α Tg, PTEN −/− and IL-14+;PTEN−/− mice stimulated with LPS. Total splenocytes, CD19+ and CD19− cells cultured in RPMI containing 10% FBS and stimulated with LPS (50 μg/ml) for 30 min. Cells were lysed and used for Western blot using p-AKT- Ser 473 antibody.

Fig. 4.

LPS stimulated TLR4 signaling activates NF-κB via canonical pathway in B cell compartment. (A) NF-κB luciferase activity in CD19+ cells isolated from all the four genotypes. CD19+ cells isolated from all four genotypes were stimulated with 50 μg/ml LPS for-24 hrs, followed by transfection of 2μg of NF-κB luciferase plasmid using Amaxa mouse B cell Nucleofactor. Luciferase activity kit was taken using Promega dual luciferase reporter system according to manufacturer’s instructions. (B) Immunoblot showing expression of pIKKα/β (S176/180), IKKα/β, pIKβα, IKβα, pNIK, NIK, pAKT−Ser 473 and AKT in CD19+ cells isolated from all the genotypes. CD19+ cells isolated from all four genotypes were stimulated with 50 μg/ml LPS for-30 min, followed by cell lysate preparation and Western blot analysis. (C) Right panel shows Western blot analysis of the NF-κB dimer subunits, p50, p52 and p65 in CD19+ B cells isolated from all genotypes. Left panel shows densitometric analysis of p65 blot. The densitometry values obtained for PTEN−/− and IL14+PTEN−/− (*P <0.05) are significant compared to WT and IL14−/−. LPS stimulated CD19+ cells were used to prepare cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts using NU-PER kit, followed by Western blotting. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments. Graphs present mean ± SEM of 3–4 mice. *P <0.05, vs. WT, as determined using t-test.

LPS signaling activates NF-κB via canonical pathway in CD19+ cells isolated from IL-14+PTEN−/− transgenic mice

Evidence that AKT regulates NF-κB via IKKα [40] lead us to evaluate levels of NF-κB activation in our PTEN deficient CD19+ B cells by analyzing NF-κB luciferase activity. We found that targeted deletion of PTEN either alone or in combination with expression of IL-14 increased NF-κB activation (2-fold increase) (Fig. 4A). It is known that activation of IKK depends upon phosphorylation at Ser176 and Ser180 in the activation loop of IKKα by AKT which causes conformational changes, resulting in kinase activation (10–13). In order to gain insight into the mechanism for how PTEN regulates TLR4 induced NF-κB transcription, we performed immunoblot analysis of pIKKα/β (S176/S180), IKKα/β, pIKβα and IKβα in 50 μg/ml LPS stimulated CD19+ cells isolated from the different genotypes. Consistent with our luciferase data, we found that IKBα is degraded more in PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− group as evident by increased levels of pIKBα and lower expression of IKBα (Fig. 4B). Our results demonstrate increased phosphorylation of IKBα on pS176/S180 in PTEN−/− as well as in IL-14+PTEN−/− cells as compared to control WT CD19+ B cells (Fig. 4B). Existing literature provides evidence that activation of NF-κB is regulated by canonical and the non-canonical pathway [41, 42]. In canonical pathway, p50-p65 subunits translocate to nucleus to mediate transcription of genes while in non-canonical pathway, NF-κB/RelB: p52 dimer translocate to nucleus. Hence, we investigated if the TLR4-induced activation of NF-κB in PTEN deficient CD19+ B cells is via the canonical (or classical) or noncanonical pathway (or alternative pathway). We performed immunoblot analysis and found that CD19+ cells isolated from PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− cells display increased expression of p50 and p65 in the nucleus as compared to controls. Since p50 and p65 are known to enter in nucleus and activate transcription of genes when NF-κB is activated via canonical pathway (Fig. 4C), these data suggest that PTEN regulates TLR4-induced NF-κB activation via the canonical pathway. It is well known that in non-canonical pathway, activation of the NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK) upon receptor ligation led to the phosphorylation and subsequent proteasomal processing of the NF-κB2 precursor protein p100 into mature p52 subunit in an IKK1/IKKa dependent manner. We did not observe a change in phosphorylation of NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK) (Fig. 4C) as well as the expression of p52 subunit which is known to translocate to nucleus upon NF-κB activation via non-canonical pathway (Fig. 4C). Our results suggest that in LPS stimulated CD19+ B cells, NF-kB is activated mainly by canonical pathway and this activation is increased by the targeted deletion of PTEN and/or transgenic expression of IL-14 in B cell compartment.

c-Myc and cyclin D1 expression is up regulated in spleens and CD19+ cells isolated from IL-14+PTEN null/transgenics in response to LPS stimulation in vitro and in vivo

Next, we investigated the levels of cyclin D1 and c-myc on the WT vs. IL-14+PTEN−/− mice by using IHC on spleens isolated from LPS injected mice (50 μg injected for 14 days) of all genotypes (Fig. 5A). Most notably, we found that c-Myc is moderately expressed in IL-14+ and highly expressed in IL-14+PTEN−/− mice, suggesting that loss of PTEN promotes c-Myc expression in the splenic CD19+ B cell compartment under LPS stimulation (Fig. 5A). Similar pattern of augmented expression of cyclinD1 was observed in spleens isolated from IL-14+PTEN−/− mice as compared to controls (Fig. 5A). To confirm this observation, we performed real time PCR on LPS stimulated CD19+ cells isolated from four genotypes to determine the expression of Cyclin D1 and c-myc (Fig. 5B). Finally, these results were further verified by Western blotting of CD19+ cells isolated from these mice, which also demonstrate increase expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc within the PTEN deficient CD19+ B cells (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

c-Myc and cyclin D1 expression is upregulated in IL-14+PTEN−/− mice. (A) IHC analysis for expression of c-Myc (upper panel) and cyclin D1 (lower panel) in the spleens of all the four genotypes. Mice were treated with 50 μg LPS for 14 days. Spleens from all the genotypes were harvested, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded and used for IHC analysis of c-Myc using Vectastain ABC Kit. (B) Real time PCR analysis of cyclin D1 and c-myc mRNA from CD19+ cells isolated from mice treated with 50 μg/ LPS for 14 days. (C) Western blot analysis for the expression of c-myc and cyclin D1 in CD19+ cells isolated from mice treated with 50 μg/ml LPS for 14 days. These CD19+ cells were lysed and used for Western blot analysis for c-myc and cyclin D1. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments. Graphs present mean ±SEM of 6–8 mice. *P <0.05, **P <0.01 and ***P <0.001 vs. WT, as determined using t-test.

PI-3K inhibitor, SF1126, blocks LPS-induced splenomegaly, proliferation and expression of cyclinD1 and myc in IL-14+PTEN−/− mice

Our results suggest that deletion of PTEN alone or in combination with IL-14 expression in B cell compartment induces splenomegaly and B cell proliferation in response to TLR4 stimulation. Therefore, we hypothesized that a pan PI-3K inhibitor would be able to reverse the phenotype. Treatment of mice with 50 mg/kg SF1126 for 21days lead to a marked reduction in spleen weight (2 fold) in IL-14+PTEN−/− mice, while there is no effect of SF1126 in WT mice (Fig. 6A). These results suggest a lack of lymphoid toxicity for the SF1126 a result which was also noted in the preclinical toxicology evaluation and the Phase I clinical trial [37, 38]. We examined the effect of SF1126 on spleen architecture. H & E staining of spleens was performed and we observed that treatment of IL-14+PTEN−/− mice with SF1126, resulted in a normalization of the splenic architecture with clearly evident germinal centers (Fig. 6B). Ki67 staining of these spleens showed decreased proliferation in PTEN null IL-14+ mice as compared to vehicle treated controls (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, SF1126 selectively depleted the CD19+ population of IL-14+PTEN−/− splenocytes (50% inhibition) (Fig. 6D). SF1126 was observed to suppress both c-myc and cyclinD1 expression in the CD19+ B cell population. Finally, we noticed that treatment of WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice with SF1126 lead to marked reduction in the expression of cyclin D1 as well as c-Myc as revealed by Western blotting and real time PCR (Fig. 6E & F). These results suggest a preferential sensitivity of PTEN deficient CD19+ lymphoid cells to SF1126 treatment in vivo. These data confirm the activity of SF1126 in a well-defined PTEN deficient lymphoproliferative disease setting and suggest the use of this agent in the treatment of lymphoma and autoimmune disease.

Fig. 6.

Pan PI-3K inhibitor, SF1126 reverses splenomegaly in IL-14+PTEN−/− mice (A) SF1126 treatment reversed splenomegaly in IL-14+PTEN−/− mice. WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice were treated with 50 μg LPS for 14 days, followed by treatment with 50 mg/kg of SF1126 for 21 days. After 21 days spleens were isolated and weighed. (B) H & E staining of spleens isolated from WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− treated with or without SF1126. Spleens were fixed in formalin (10%) for 24 hours, embedded in paraffin and used for H & E staining. (C) Ki67 staining of spleens isolated from WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− treated with or without SF1126. (D) SF1126 treatment blocked the proliferation of CD19+ cells in IL-14+PTEN−/− mice. CD19+ cells isolated from SF1126 treated WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice and were analyzed by FACS. (E) SF1126 treatment blocked the expression of c-myc and cyclin D1 as revealed by Western blotting. CD19+ cells isolated from WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice treated with 50 mg/kg SF1126 for 21 days were used for Western blotting. (F) Real time PCR data showing down regulated expression of c-myc and cyclinD1 in the WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice treated with SF1126. RNA isolated from CD19+ cells isolated from WT and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice were used for checking expression of c-myc and cyclin D1 using Real time PCR. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments. Graphs present mean ±SEM of 8–10 mice. *P <0.05, **P <0.01 vs. WT, as determined using t-test.

Discussion

The role of LPS signaling in B cell proliferation, polarization and migration is well studied [8, 9]. However, molecular mechanisms controlling LPS signaling in B cells are unclear. In the present study, we established a central role of PTEN and PI-3K in regulating LPS signaling in the CD19+ B cell compartment.

IL-14 is a cytokine that was identified and cloned from a Burkitt lymphoma cell line [43] and shown to enhance B cell proliferation, especially of germinal center B cells and surface Ig (sIg)D low human tonsillar B cells, which includes B1 cells and activated B2 cells [43, 44]. These mice also develop mature CD19+ B cell lymphomas at the age of 14–18 months and autoimmune disease models for Sjogren’s disease and SLE [32]. The role of IL-14 in enhancing B cell proliferation is well established but there is no literature which shows the role of IL-14 in mediating LPS signaling. Previous studies suggest an important role of PTEN in B cell homeostasis and immunoglobulin class switch recombination [27, 28]. Anzelon et al has reported that conditional deletion of PTEN in B cells led to the preferential generation of marginal zone (MZ) B cells and B1 cells with no B cell malignancy. These reports lead us to hypothesize that the combined deletion of PTEN and directed expression of IL-14 might lead to B cell lymphoma. To study the role of PTEN and IL-14 in lymphoproliferation and B cell biology, we utilized CD19Cre × PTENfl/fl mice crossed with an IL-14α transgenic mouse to generate an IL-14+PTEN−/− transgenic mouse model. Our data suggest that conditional deletion of PTEN in the B cell compartment leads to baseline splenomegaly and altered spleen morphology, a phenotype that was exaggerated by directed expression of IL-14α in B cell compartment (Fig. 1) and this phenomenon increased two-fold upon in vivo stimulation with 50 μg/ml LPS (Fig. 1). The IL-14α mice display minimal baseline splenomegaly as compared to control mice and this effect was markedly exaggerated in IL-14+PTEN−/−mice.

To examine the role of PTEN in the regulation of TLR4/RP105 signaling, we used LPS (TLR4/RP105 ligand) to stimulate CD19+ cell proliferation in the different genotypes. We observed an almost 5 fold increase in B cell proliferation in CD19+ compartment in the PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− groups over the WT (Fig. 2) (p < .0001). The CD19+ cell proliferation was also significantly increased in IL-14+ group as compared to WT (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, we observed increased levels of pAKT in CD19+ B cells isolated from the IL-14α transgenic mice upon stimulation with 50 μg/ml LPS as compared to controls (Fig. 3C). There are no reports that that IL-14α contributes to LPS signaling in B cells via the activation of the PI-3K pathway. Hence, our results suggest that IL-14α somehow augments activation of AKT in CD19+ B cells in response to LPS. The role of PTEN and PI-3K in TLR4/RP105 signaling is well-documented in macrophages, endothelial cells [14, 16, 19, 20]. However there are no reports that PTEN controls TLR4/ RP105 signaling in B cell compartment or any studies relating to the mechanism by which PTEN regulates LPS signaling in the B cells. Our results provide evidence that LPS stimulated TLR4/RP105 signaling including increased p-AKT, expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc and the activated NF-κB in a canonical manner in the CD19+ B cell compartment. This response is regulated by PTEN and PI-3K in the B cell compartment. The role of NF-κB members in BCR-mediated proliferation, survival, and Ig class switching is well-established [45, 46]. Accordingly, individual NF-κB subsets play distinct roles in the maturation of the B cell compartment [45]. It is well established that LPS can activate NF-κB via both canonical as well as non canonical pathways [47, 48]. Our results demonstrate that LPS activation of NF-κB is regulated by the tumor suppressor phosphatase, PTEN in the CD19+ B cell compartment via canonical pathway as evident by accumulation of p50 and p65 subunits in the nuclear fraction of CD19+ B cells isolated from PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice (Fig. 4B). In contrast, there is no change in the expression of p52 subunit in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions isolated from CD19+ B cells isolated from PTEN−/− and IL-14+PTEN−/− mice. p52 subunit is known to dimerize with RelB and activate NF-κB via non-canonical pathway[47]. Moreover, we observed that the activation of NF-κB is drastically increased in the PTEN null as well as IL-14+PTEN null CD19+ B cells, which promotes transcription of c-myc and cyclin D1 leading to increased cell proliferation in CD19+ lacking expression of PTEN either alone or in combination with expression of IL-14 (Fig. 4 & 5). In future experiments, will determine the role of PTEN and PI-3K in TLR4 vs. RP105 signaling downstream of LPS stimulation in B cell proliferation.

Currently there is considerable interest in using PI-3K inhibitors to treat B cell nonhodgkin lymphoma [49, 50]. SF1126 is a vascular-targeted drug which showed considerable efficacy in B cell malignancies in Phase I clinical trials [37]. Hence, we tested the efficacy of this drug in our mouse lymphoproliferation model. We determined the effect of SF1126 treatment on splenomegaly and B cell proliferation of CD19+ B cells in PTEN null IL-14+ mice. SF1126 potently inhibited the proliferation as well as expression of cyclinD1 and c-myc in CD19 + B cell compartment and resulted in the depletion of 50 × 106 IL14α+; PTEN−/− CD19+ B cells from the spleen and normalized the splenic cytoarchitecture, thus providing evidence for the therapeutic potential of this drug in B cell malignancies.

In conclusion, our findings support the hypothesis that PTEN functions as a central nodal “intercept point” and regulator of B-cell pathogenesis in this murine model for lymphoproliferation in response to LPS stimulation. We continue to use this model to study the role of PTEN and associated signaling pathways and additional PI-3K inhibitors for therapeutic activity in lymphoproliferative and autoimmune diseases.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Generation of CD19 B cell specific IL-14+, PTEN−/− and IL14;PTEN−/− mice: (A) Transgenic breeding strategy for the generation of four genotypes (PTENfl/fl, IL-14α x PTENfl/fl, CD19Cre x PTENfl/fl, and IL-14α x PTENfl/fl x CD19Cre) and four genotypes (WT, IL-14+, PTEN−/−, IL-14+PTEN−/−) is shown, respectively. (B) Identification of PTENfl/fl, IL-14, CD19Cre and CD19 WT alleles by PCR of genomic DNA from all genotypes. The PTENfl/fl x CD19Cre genotype results in a genotype showing the absence of PTEN and expression of CD19 cre recombinase in the CD19+ splenocyte population (C). Immunoblot for PTEN and cre protein in CD19+ cells isolated from all four genotypes. Total splenocytes isolated from 10–20 week old mice of all four genotypes were used for the isolation of CD19+ and CD19− cell populations using anti-CD19 microbeads and MACS column technology (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn CA) following manufacturer’s instructions. These CD19+ and CD19− cells were used to prepare cell lysates followed by Western blotting. (D) RT-PCR evaluating the expression of IL-14α mRNA in all four genotypes. RNA was extracted from spleens of all four genotypes and used for RT-PCR.

Fig. S2. Flow cytometric analysis of total splenocytes for IgM/IgD, and CD21/CD23. Cells were analyzed from the B220+ gated populations. IgD and CD23 are reduced in the PTEN −/− transgenic, but are restored in the IL-14+PTEN −/− transgenic to levels of the WT mice.

Highlights:

First genetic evidence that PTEN controls LPS/TLR4 signaling in B lymphocytes

Evidence that PTEN regulates LPS induced lymphoproliferation in vivo

PI-3 kinase inhibitors block LPS induced lymphoproliferation in vivo

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grants CA94233 and HL091365 to Donald L. Durden.

Abbreviations:

- PI-3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COI statement: D. Durden discloses financial conflict of interest related to the development of SF1126. This aspect has been reviewed by the UCSD committee on conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Ogata H, Su I, Miyake K, Nagai Y, Akashi S, Mecklenbrauker I, Rajewsky K, Kimoto M, Tarakhovsky A, The toll-like receptor protein RP105 regulates lipopolysaccharide signaling in B cells, J Exp Med 192 (2000) 23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yazawa N, Fujimoto M, Sato S, Miyake K, Asano N, Nagai Y, Takeuchi O, Takeda K, Okochi H, Akira S, Tedder TF, Tamaki K, CD19 regulates innate immunity by the toll-like receptor RP105 signaling in B lymphocytes, Blood 102 (2003) 1374–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pasare C, Medzhitov R, Control of B-cell responses by Toll-like receptors, Nature 438 (2005) 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ha SA, Tsuji M, Suzuki K, Meek B, Yasuda N, Kaisho T, Fagarasan S, Regulation of B1 cell migration by signals through Toll-like receptors, J Exp Med 203 (2006) 2541–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O, Pathogen recognition and innate immunity, Cell 124 (2006) 783–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Guttridge DC, Albanese C, Reuther JY, Pestell RG, Baldwin AS Jr., NF-kappaB controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1, Mol Cell Biol 19 (1999) 5785–5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Duyao MP, Buckler AJ, Sonenshein GE, Interaction of an NF-kappa B-like factor with a site upstream of the c-myc promoter, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87 (1990) 4727–4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Barrio L, Saez de Guinoa J, Carrasco YR, TLR4 Signaling Shapes B Cell Dynamics via MyD88-Dependent Pathways and Rac GTPases, J Immunol (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hwang IY, Park C, Harrison K, Kehrl JH, TLR4 signaling augments B lymphocyte migration and overcomes the restriction that limits access to germinal center dark zones, J Exp Med 206 (2009) 2641–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lee JO, Yang H, Georgescu MM, Di Cristofano A, Maehama T, Shi Y, Dixon JE, Pandolfi P, Pavletich NP, Crystal structure of the PTEN tumor suppressor: implications for its phosphoinositide phosphatase activity and membrane association, Cell 99 (1999) 323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Maehama T, Dixon JE, The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, J Biol Chem 273 (1998) 13375–13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gunzl P, Schabbauer G, Recent advances in the genetic analysis of PTEN and PI3K innate immune properties, Immunobiology 213 (2008) 759–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stocker H, Andjelkovic M, Oldham S, Laffargue M, Wymann MP, Hemmings BA, Hafen E, Living with lethal PIP3 levels: viability of flies lacking PTEN restored by a PH domain mutation in Akt/PKB, Science 295 (2002) 2088–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li X, Tupper JC, Bannerman DD, Winn RK, Rhodes CJ, Harlan JM, Phosphoinositide 3 kinase mediates Toll-like receptor 4-induced activation of NF-kappa B in endothelial cells, Infect Immun 71 (2003) 4414–4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Laird MH, Rhee SH, Perkins DJ, Medvedev AE, Piao W, Fenton MJ, Vogel SN, TLR4/MyD88/PI3K interactions regulate TLR4 signaling, J Leukoc Biol 85 (2009) 966–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ojaniemi M, Glumoff V, Harju K, Liljeroos M, Vuori K, Hallman M, Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is involved in Toll-like receptor 4-mediated cytokine expression in mouse macrophages, Eur J Immunol 33 (2003) 597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jones BW, Heldwein KA, Means TK, Saukkonen JJ, Fenton MJ, Differential roles of Toll-like receptors in the elicitation of proinflammatory responses by macrophages, Ann Rheum Dis 60 Suppl 3 (2001) iii6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Akira S, Hoshino K, Myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent and -independent pathways in toll-like receptor signaling, J Infect Dis 187 Suppl 2 (2003) S356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cao X, Wei G, Fang H, Guo J, Weinstein M, Marsh CB, Ostrowski MC, Tridandapani S, The inositol 3-phosphatase PTEN negatively regulates Fc gamma receptor signaling, but supports Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in murine peritoneal macrophages, J Immunol 172 (2004) 4851–4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kamo N, Ke B, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW, PTEN-mediated Akt/beta-catenin/Foxo1 signaling regulates innate immune responses in mouse liver ischemia/reperfusion injury, Hepatology 57 (2013) 289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lee JY, Ye J, Gao Z, Youn HS, Lee WH, Zhao L, Sizemore N, Hwang DH, Reciprocal modulation of Toll-like receptor-4 signaling pathways involving MyD88 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT by saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, J Biol Chem 278 (2003) 37041–37051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Luyendyk JP, Schabbauer GA, Tencati M, Holscher T, Pawlinski R, Mackman N, Genetic analysis of the role of the PI3K-Akt pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine and tissue factor gene expression in monocytes/macrophages, J Immunol 180 (2008) 4218–4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fruman DA, Snapper SB, Yballe CM, Davidson L, Yu JY, Alt FW, Cantley LC, Impaired B cell development and proliferation in absence of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p85alpha, Science 283 (1999) 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Suzuki H, Terauchi Y, Fujiwara M, Aizawa S, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T, Koyasu S, Xid-like immunodeficiency in mice with disruption of the p85alpha subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Science 283 (1999) 390–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Clayton E, Bardi G, Bell SE, Chantry D, Downes CP, Gray A, Humphries LA, Rawlings D, Reynolds H, Vigorito E, Turner M, A crucial role for the p110delta subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in B cell development and activation, J Exp Med 196 (2002) 753–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Omori SA, Cato MH, Anzelon-Mills A, Puri KD, Shapiro-Shelef M, Calame K, Rickert RC, Regulation of class-switch recombination and plasma cell differentiation by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling, Immunity 25 (2006) 545–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Suzuki A, Kaisho T, Ohishi M, Tsukio-Yamaguchi M, Tsubata T, Koni PA, Sasaki T, Mak TW, Nakano T, Critical roles of Pten in B cell homeostasis and immunoglobulin class switch recombination, J Exp Med 197 (2003) 657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Anzelon AN, Wu H, Rickert RC, Pten inactivation alters peripheral B lymphocyte fate and reconstitutes CD19 function, Nat Immunol 4 (2003) 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rudelius M, Pittaluga S, Nishizuka S, Pham TH, Fend F, Jaffe ES, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Raffeld M, Constitutive activation of Akt contributes to the pathogenesis and survival of mantle cell lymphoma, Blood 108 (2006) 1668–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Uddin S, Hussain AR, Siraj AK, Manogaran PS, Al-Jomah NA, Moorji A, Atizado V, Al-Dayel F, Belgaumi A, El-Solh H, Ezzat A, Bavi P, Al-Kuraya KS, Role of phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase/AKT pathway in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma survival, Blood 108 (2006) 4178–4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Miletic AV, Anzelon-Mills AN, Mills DM, Omori SA, Pedersen IM, Shin DM, Ravetch JV, Bolland S, Morse HC 3rd, Rickert RC, Coordinate suppression of B cell lymphoma by PTEN and SHIP phosphatases, J Exp Med 207 (2010) 2407–2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shen L, Zhang C, Wang T, Brooks S, Ford RJ, Lin-Lee YC, Kasianowicz A, Kumar V, Martin L, Liang P, Cowell J, Ambrus JL Jr., Development of autoimmunity in IL-14alpha-transgenic mice, J Immunol 177 (2006) 5676–5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Suzuki A, Kaisho T, Ohishi M, Tsukio-Yamaguchi M, Tsubata T, Koni PA, Sasaki T, Mak TW, Nakano T, Critical Roles of Pten in B Cell Homeostasis and Immunoglobulin Class Switch Recombination, J. Exp. Med 197 (2003) 657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shen L, Zhang C, Wang T, Brooks S, Ford RJ, Lin-Lee YC, Kasianowicz A, Kumar V, Martin L, Liang P, Cowell J, Ambrus JL Jr., Development of Autoimmunity in IL-14{alpha}-Transgenic Mice, J Immunol 177 (2006) 5676–5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rickert RC, Roes J, Rajewsky K, B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice, Nucleic Acids Res 25 (1997) 1317–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ, Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method, Nat Protoc 3 (2008) 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mahadevan D, Chiorean EG, Harris WB, Von Hoff DD, Stejskal-Barnett A, Qi W, Anthony SP, Younger AE, Rensvold DM, Cordova F, Shelton CF, Becker MD, Garlich JR, Durden DL, Ramanathan RK, Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the pan-PI3K/mTORC vascular targeted pro-drug SF1126 in patients with advanced solid tumours and B-cell malignancies, Eur J Cancer 48 (2012) 3319–3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Garlich JR, De P, Dey N, Su JD, Peng X, Miller A, Murali R, Lu Y, Mills GB, Kundra V, Shu HK, Peng Q, Durden DL, A vascular targeted pan phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor prodrug, SF1126, with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity, Cancer Res 68 (2008) 206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Monick MM, Carter AB, Robeff PK, Flaherty DM, Peterson MW, Hunninghake GW, Lipopolysaccharide activates Akt in human alveolar macrophages resulting in nuclear accumulation and transcriptional activity of beta-catenin, J Immunol 166 (2001) 4713–4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gustin JA, Korgaonkar CK, Pincheira R, Li Q, Donner DB, Akt regulates basal and induced processing of NF-kappaB2 (p100) to p52, J Biol Chem 281 (2006) 16473–16481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tergaonkar V, NFkappaB pathway: a good signaling paradigm and therapeutic target, Int J Biochem Cell Biol 38 (2006) 1647–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Scheidereit C, IkappaB kinase complexes: gateways to NF-kappaB activation and transcription, Oncogene 25 (2006) 6685–6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ambrus JL Jr., Fauci AS, Human B lymphoma cell line producing B cell growth factor, J Clin Invest 75 (1985) 732–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ambrus JL Jr., Chesky L, Stephany D, McFarland P, Mostowski H, Fauci AS, Functional studies examining the subpopulation of human B lymphocytes responding to high molecular weight B cell growth factor, J Immunol 145 (1990) 3949–3955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Liou HC, Hsia CY, Distinctions between c-Rel and other NF-kappaB proteins in immunity and disease, Bioessays 25 (2003) 767–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Karin M, Lin A, NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death, Nat Immunol 3 (2002) 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bonizzi G, Karin M, The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity, Trends Immunol 25 (2004) 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hayden MS, Ghosh S, Signaling to NF-kappaB, Genes Dev 18 (2004) 2195–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zang C, Eucker J, Liu H, Coordes A, Lenarz M, Possinger K, Scholz CW, Inhibition of pan-class I PI3 kinase by NVP-BKM120 effectively blocks proliferation and induces cell death in diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Leuk Lymphoma (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Reeder CB, Ansell SM, Novel therapeutic agents for B-cell lymphoma: developing rational combinations, Blood 117 (2011) 1453–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Generation of CD19 B cell specific IL-14+, PTEN−/− and IL14;PTEN−/− mice: (A) Transgenic breeding strategy for the generation of four genotypes (PTENfl/fl, IL-14α x PTENfl/fl, CD19Cre x PTENfl/fl, and IL-14α x PTENfl/fl x CD19Cre) and four genotypes (WT, IL-14+, PTEN−/−, IL-14+PTEN−/−) is shown, respectively. (B) Identification of PTENfl/fl, IL-14, CD19Cre and CD19 WT alleles by PCR of genomic DNA from all genotypes. The PTENfl/fl x CD19Cre genotype results in a genotype showing the absence of PTEN and expression of CD19 cre recombinase in the CD19+ splenocyte population (C). Immunoblot for PTEN and cre protein in CD19+ cells isolated from all four genotypes. Total splenocytes isolated from 10–20 week old mice of all four genotypes were used for the isolation of CD19+ and CD19− cell populations using anti-CD19 microbeads and MACS column technology (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn CA) following manufacturer’s instructions. These CD19+ and CD19− cells were used to prepare cell lysates followed by Western blotting. (D) RT-PCR evaluating the expression of IL-14α mRNA in all four genotypes. RNA was extracted from spleens of all four genotypes and used for RT-PCR.

Fig. S2. Flow cytometric analysis of total splenocytes for IgM/IgD, and CD21/CD23. Cells were analyzed from the B220+ gated populations. IgD and CD23 are reduced in the PTEN −/− transgenic, but are restored in the IL-14+PTEN −/− transgenic to levels of the WT mice.