Abstract

The most prevalent degenerative brain disease, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is characterized by cognitive function impairment. The ability to code new memories is lost in AD patients, and their lives are very challenging. Inhibitors of cholinesterase (ChE) and monoamine oxidase (MAO) have drawn interest as potential therapies for AD. To combat Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a new class of Coumarin-hydrazone hybrids has been synthesized 3(a-m). Compounds 3a, 3e, and 3l exhibited significant acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory activity with low IC50 values of 7.40 ± 0.14 µM, 8.01 ± 0.70 µM, and 8.54 ± 1.01 µM, respectively. Additionally, these compounds, along with 3k, demonstrated potent butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) inhibition, with IC50 values from 65.41 ± 4.55 µM to 74.98 ± 5.30 µM, highlighting their dual cholinesterase inhibitory potential. Compound like 3a (1.44 ± 0.03 µM), 3e (1.51 ± 0.13 µM), and 3l (1.65 ± 0.03 µM) display robust MAO-A inhibition, suggesting high potency. To see how the most potent inhibitor chemicals affected the substrate–enzyme relationship, enzyme kinetic tests were conducted in addition to enzyme inhibition investigations. Compound 3e may function as a dual binding site AChE inhibitor, according to docking studies in addition to in vitro testing.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-28665-4.

Keywords: Hydrazones, Coumarin, Thiosemicarbazones, Anti-Alzheimer, Cholinesterase, MAO, Molecular docking, DFT

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Chemical biology, Chemistry, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Drug discovery, Neuroscience

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a broad neurodegenerative illness characterized by a disorder of declining cognitive ability, memory loss, and behavioral problems. The primary characteristics of this disorder include β-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, synaptic dysfunction, and neuronal death. According to the World Alzheimer’s Report, there are currently 47 million people with Alzheimer’s disease worldwide, and by 2050, that figure is predicted to rise to 131 million1,2. Different treatment strategies need to focus on multiple disease development targets due to the multi-dimensional aspects of AD including inhibition of phosphorylation of IκBα and p383, ceramide induced neuronal senescence and expression profiles of AD-related lncRNAs4 and mRNAs5. According to the cholinergic hypothesis, one of the reasons for the cognitive deficits seen in AD is a marked decrease in acetylcholine levels. The breakdown of acetylcholine occurring in the synaptic cleft happens through enzyme activities of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE)6. The blocking of these enzymes has the potential to lengthen acetylcholine duration in the synaptic cleft and boost both cholinergic neurotransmission and cognitive abilities. Although AChE is the main enzyme involved in acetylcholine breakdown under normal settings, BChE activity rises in the AD brain and implies that dual inhibition of both AChE and BChE may provide a more efficient treatment strategy7.

Enzymes that catalyze the oxidative deamination of monoamine neurotransmitters including dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine are monoamine oxidases (MAOs), especially MAO-A and MAO-B. This reaction produces hydrogen peroxide, which fuels oxidative stress a major component of neurodegeneration. AD patients have shown higher MAO activity, which causes more oxidative damage and aggravation of disease pathogenesis8. Therefore, MAO inhibitors have been studied as possible therapeutic mediators to decrease oxidative stress and restore neurotransmitter balance in the AD brain. In the current therapeutic regimen, the FDA-approved anti-AD drugs containing the AChEIs donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, and memantine9 are applied to target these pathogenic pathways Fig. 1. Although tacrine was the first cholinesterase inhibitor (ChEI) proven effective for treating Alzheimer’s disease (AD), its use was discontinued due to liver toxicity. Unfortunately, these conventional drugs only provide symptomatic relief and do not prevent or delay the progression of the disease. The failure of anti-AD pharmaceutical research has raised worries about the previous paradigm of “one drug, one target, one illness” and the discovery of multi-target directed ligands (MTDLs) seems to be a promising paradigm for discovering novel small-molecule substances10.

Fig. 1.

Structure of FDA approved drugs and previously reported coumarin and hydrazine compounds for anti-Alzheimer.

Coumarin derivatives display a wide range of pharmacological effects, including antidepressant11, antimicrobial12, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory13, antinociceptive, anti-tumor, antiasthmatic14, photosensitizers for targeted cancer treatment strategy15and antiviral activities, in addition to their acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory properties10,16. The flexibility to insert chemical substitutions at different places of the coumarin core structure has made these molecules exceedingly desirable for drug discovery, notably in the creation of AChE inhibitors. Among these natural chemicals, derivatives like notopterol (III), esculetin (IV)17, and decursinol (V)10 have been studied for their possible application in Alzheimer’s disease therapy. 3-acetyl-8-methoxy-2 H-chromen-2-one, a coumarin derivative, is well-known for its extensive pharmacological activity. While some natural coumarins demonstrate poor MAO inhibitory efficacy, others, when suitably modified, have been found as powerful and selective MAO inhibitors18,19. The identification of critical structural characteristics within the coumarin framework has simplified the design and synthesis of new analogs with increased inhibition of MAO, AChE, and BChE, making them viable candidates for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Many synthetic coumarin derivatives have been investigated for the generation of novel medications exhibiting anti-neurodegenerative properties Fig. 1.

Hydrazide groups, including a hydrazine (-NH-NH2) connected to a carbonyl group, boost the biological activity of coumarins by enhancing inhibition of important Alzheimer’s disease enzymes such AChE, BChE, and MAOs20. This combination utilizes the enzyme-inhibiting capabilities of coumarins and the flexible binding of hydrazides, resulting in hybrid compounds with increased therapeutic benefits21,22. Hydrazone compounds, including an azomethine moiety, are crucial in drug discovery owing to their extensive pharmacological activity23,24. When connected to heterocyclic systems, they create hydrogen bonds with targets, boosting their efficacy. These compounds demonstrate considerable antibacterial25, anticancer26, antiviral27, and enzyme-inhibitory activity, including high inhibition of AChE and BChE21,28,29.

The creation of multifunctional drugs that may concurrently control numerous disease sites is a potential method in AD treatment. Building upon these ideas, the current work seeks to develop, synthesize, and biological evaluation of new 2 H-chromen-2-one–hydrazone hybrids as possible therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease. The main goal includes synthesizing various hybrid compounds through conjugation between different hydrazide derivatives with 2 H-chromen-2-one scaffolds. The researchers evaluated how well their synthesized hybrid compounds restrained AChE, BChE, and MAO-A enzymes for understanding AD-related enzyme modification effects. These hybrid compounds combining cholinergic deficiency and oxidative stress treatment possess excellent potential to enhance mental symptoms while delaying AD progression. The research utilizes molecular docking investigations to analyze the binding interactions between the hybrids and active sites from target enzymes which identify the molecular factors that drive inhibitory processes. The study implements a complete strategy to identify essential compounds that can effectively counteract various destructive AD pathways which could lead to valuable therapeutic treatment methods.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

The target compounds 3(a-m) were synthesized via a condensation reaction (Scheme 1). Coumarin derivative 1 (0.1 g, 0.45 mmol) was dissolved in absolute ethanol (EtOH) with acetic acid (3–4 drops) as a catalyst. After dissolution, the hydrazide derivative (0.1 g, 0.45 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was refluxed at 80 °C for 5–6 h. The reaction progress was monitored using TLC, and upon completion, the precipitate was collected by hot filtration, washed with hot ethanol, and dried at 50 °C overnight. The products were characterized by 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy. In the 1H NMR spectrum of 3a, the singlets at δ 11.76 ppm and δ 11.62 ppm correspond to the hydroxyl (-OH) and hydrazide (-NH) protons, respectively, indicating strong hydrogen bonding. Aromatic protons from the coumarin and naphthalene rings appear as singlets, doublets, and multiples in the range of δ 8.66–7.36 ppm, consistent with the expected structure. The singlet at δ 3.95 ppm is attributed to the methoxy (-OCH3) group, while the singlet at δ 2.34 ppm corresponds to the methyl group (-CH3) attached to the ethylidene moiety. In the 13C NMR spectrum (101 MHz, DMSO), the signals at δ 162.11, and 159.49 correspond to carbonyl carbons (C = O) of the coumarin and hydrazide groups. The aromatic carbons of the coumarin and naphthalene rings resonate between δ 146.79–111.20 ppm, while the methoxy carbon (-OCH3) appears at δ 56.61 ppm. The methyl carbon (-CH3) is observed at δ 16.21 ppm.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of targeted hydrazones 3 (a-m).

Structure-activity relationship (SAR)

The structure-activity relationship (SAR) study of new coumarin derivatives reveals important details about their inhibitory effects against acetylcholinesterase (AChE), butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), and monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) through IC50 values provided below.

The potent AChE inhibitor properties of compounds 3a (7.40 ± 0.14 µM), 3e (8.01 ± 0.70 µM) and 3l (8.54 ± 1.01 µM) result from their lower IC50 values. The presence of hydroxy naphthol groups, trifluoromethyl phenyl, and pyridine groups in these compounds respectively, seems to enhance their inhibitory actions. The most potent AChE inhibition is done with compound 3a containing a hydroxy group at position 2 and both 3e and 3l following closely behind. The compounds 3g and 3h display reduced inhibitory effects against AChE because their larger substituents create hinder which keeps the enzyme from achieving proper alignment or mobility required for successful binding events. AChE inhibition becomes more potent for two groups of replacement structures because they create strong interaction forces (hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking) alongside enhanced binding affinity to the enzyme active site. Binding and inhibitory efficiency towards AChE drops for the 4-chlorophenyl and indole groups because they experience both structural blocking effects and fewer beneficial molecular interactions within the enzyme complex. For BChE inhibition, similar results are found. Compounds 3a (74.35 ± 4.98 µM), 3e (65.41 ± 4.55 µM), 3k (71.45 ± 3.68 µM) and 3l (74.98 ± 5.30 µM) exhibit significant inhibition, whereas compounds like 3b (> 100 µM), 3c (> 100 µM) and 3j (> 100 µM) indicate weak or no inhibition. Again, the inclusion of hydroxy naphthol and trifluoromethyl phenyl groups at favorable places on the hydrazone seems to boost binding affinity for BChE. For MAO-A inhibition, substances like 3a (1.44 ± 0.03 µM), 3e (1.51 ± 0.13 µM), and 3l (1.65 ± 0.03 µM) display robust inhibition, with low IC50 values suggesting high potency. These compounds, notably 3a and 3e, contain hydroxy naphthol and trifluoromethyl phenyl, indicating that this substitution increases interaction with MAO-A. In contrast, substances like 3f (3.94 ± 0.43 µM) and 3j (2.50 ± 0.31 µM) exhibit lesser inhibition, confirming the hypothesis that hydroxy naphthol improves MAO-A inhibition Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Structure-activity relationship (SAR) study of new coumarin derivatives.

Molecular Docking simulations

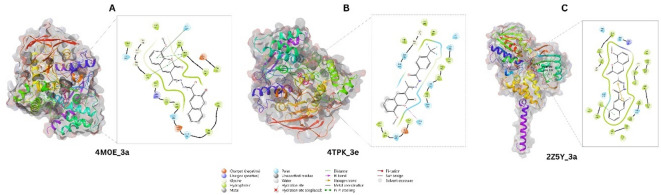

The docking study of hAChE, hBChE, and MAO-A was carried out for synthesized compounds using Autodock vina V. 1.2.6. The docking results were analyzed in terms of binding energy Fig. 3 affinity and the type of interactions at the active site of selected targets.

Fig. 3.

Molecular interactions of the ligands with proteins (a) 4M0E with 3a, (b) 4TPK with 3e, and (c) 2Z5Y with 3a.

The Table 1 provides detailed molecular interactions of synthesized compounds with proteins 4M0E, 4TPK, and 2Z5Y. It has been found that based on biological activity and docking scores, compound 3a shows the best binding affinity for hAChE (4M0E) and MAO-A (2Z5Y) through hydrophobic interactions. The aromatic ring and polar functional groups like hydroxyl and amine of 3a contribute significantly to these interactions, which enhances binding affinity. For hBChE, compound 3e shows better affinity due to the presence of the phenyl group, which interacts with hydrophobic residues (PHE, TYR) in the binding site. Additionally, it has hydrogen bonding and π-stacking interactions, which further stabilize the complex. Based on the docking study, it has been suggested that compounds with a blend of hydrophobic groups, aromatic rings, π-stacking interactions and polar groups for hydrogen bonding exhibit strong affinity and better inhibition of target enzymes.

Table 1.

Enzyme Inhibition activity of novel compounds 3 (a-m) against AChE, BChE, and MAO-A.

| Compounds | IC50 (µM) | Ki (µM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE | BChE | MAO-A | AChE | BChE | |

| 3a | 7.40 ± 0.14 | 74.35 ± 4.98 | 1.44 ± 0.03 | 6.03 ± 0.40 | 63.27 ± 5.38 |

| 3b | 26.53 ± 3.42 | > 100 | 1.97 ± 0.10 | 15.74 ± 1.37 | > 100 |

| 3c | 17.05 ± 1.90 | > 100 | 2.03 ± 0.08 | 11.35 ± 0.93 | > 100 |

| 3d | 20.16 ± 2.67 | 90.05 ± 3.78 | 1.73 ± 0.05 | 13.50 ± 1.24 | 69.94 ± 5.75 |

| 3e | 8.01 ± 0.70 | 65.41 ± 4.55 | 1.51 ± 0.13 | 7.38 ± 1.01 | 57.01 ± 3.95 |

| 3f | 23.84 ± 2.44 | 78.25 ± 5.80 | 3.94 ± 0.43 | 19.55 ± 2.44 | 68.47 ± 5.07 |

| 3g | 29.01 ± 4.30 | 81.53 ± 6.02 | 2.08 ± 0.15 | 21.05 ± 3.48 | 73.58 ± 4.66 |

| 3h | 41.06 ± 3.28 | 84.97 ± 3.48 | 1.80 ± 0.26 | 25.82 ± 1.97 | 77.05 ± 6.92 |

| 3i | 18.37 ± 1.98 | 79.30 ± 5.03 | 1.87 ± 0.07 | 15.43 ± 2.01 | 70.32 ± 3.57 |

| 3j | 21.90 ± 3.24 | > 100 | 2.50 ± 0.31 | 14.60 ± 1.05 | > 100 |

| 3k | 12.42 ± 0.98 | 71.45 ± 3.68 | 1.83 ± 0.17 | 7.95 ± 0.57 | 66.13 ± 4.62 |

| 3l | 8.54 ± 1.01 | 74.98 ± 5.30 | 1.65 ± 0.34 | 7.08 ± 0.64 | 69.04 ± 5.30 |

| 3m | 14.76 ± 1.40 | 82.34 ± 6.90 | 1.90 ± 0.30 | 10.36 ± 0.59 | 71.39 ± 7.01 |

| Galantamine1 | 22.53 ± 1.05 | 97.38 ± 5.74 | - | 14.24 ± 0.98 | 81.65 ± 7.33 |

| Clorgyline2 | - | - | 6.98 ± 0.15 | - | - |

Significant values are in [bold].

1 Standard for AChE and BChE.

2 Standard for MAO-A.

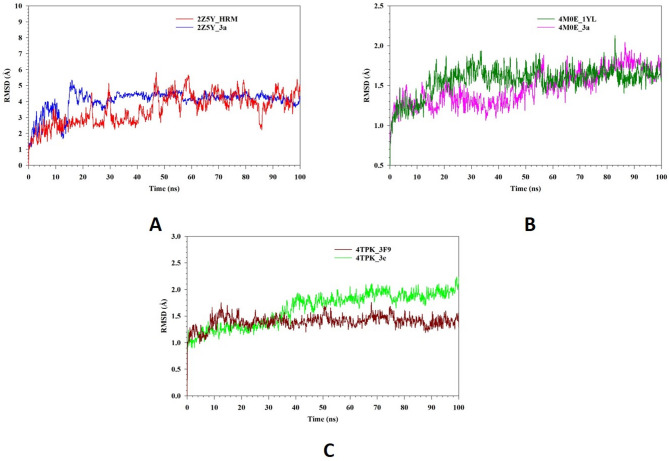

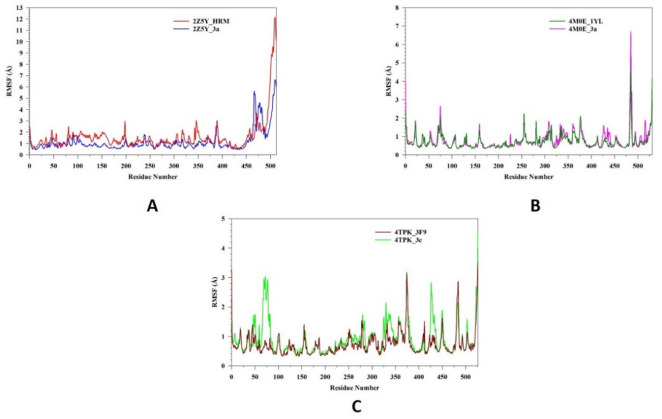

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics and simulation (MD) studies were carried out to determine the stability and convergence of 2Z5Y with 3a and HRM, 4M0E with 3a and 1YT, 4TPK with 3e and 3F9 represented as 2Z5Y_3a, 2Z5Y_HRM, 4M0E_3a, 4M0E_1YT, 4TPK_3e, 4TPK_3F9 respectively. Figure 4A represents a Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) analysis of 2Z5Y_3a (blue) and 2Z5Y_HRM (red). Initially both complexes undergo equilibrium state within 10–20 ns, where the RMSD gradually increases. 2Z5Y_3a (blue) exhibits a higher RMSD (⁓5 Å) in the early phase, indicating conformational adjustment before stabilizing around 30 ns. From 30 ns onwards, 2Z5Y_3a maintains a relatively stable RMSD, averaging RMSD 4.05 Å, indicating that the ligand binding stabilizes protein structure. In contrast, 2Z5Y_HRM maintain relatively lower RMSD (⁓4 Å) initially, but experiences higher fluctuations throughout simulation period, suggesting a more dynamic nature. The complex exhibits average RMSD up to 3.52 Å with higher fluctuations, which suggests more flexibility in the system. Figure 4B represents RMSD analysis of 4M0E_3a (pink) and 4M0E_1YL (DK. Green). The 4M0E_1YL (DK. Green) complex exhibits slightly higher fluctuations throughout simulation, with RMSD averaging up to 1.57 Å, indicating that the system experiences more flexibility. In contrast, 4M0E_3a (pink) maintains a lower RMSD 1.47 Å with minimal deviations and appease to reach stability. Both complexes remain within an acceptable RMSD (< 3 Å), confirming overall stability. Figure 4C represents RMSD analysis of 4TPK_3e (green) and 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red). Both complexes exhibit an initial equilibrium phase within 10–20 ns, where RMSD gradually increases. The complex 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red) shows a relatively stable RMSD averaging up to 1.39 Å with minimal fluctuations, suggesting strong binding and conformational stability. On other hand, the 4TPK_3e (green) displays higher fluctuations with average RMSD 1.64 Å, indicating less stable complex compared with 4TPK_3F9. Figure 5A represents the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of 2Z5Y_3a (blue) and 2Z5Y_HRM (red). Both complexes exhibit similar fluctuation patterns, with minor variations in flexibility. The 2Z5Y_3a (blue) demonstrates lower RMSF (average 1.14 Å) across majority of residues, indicating stability of protein. Other complex 2Z5Y_HRM (red) displays slightly higher fluctuations with average RMSF (1.60 Å), particularly loop regions and terminal residues at 471–473, 494–512, suggesting a more dynamic behavior. Figure 5B represents the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of 4M0E_3a (pink) and 4M0E_1YL (DK. Green). Both complexes exhibit a similar RMSF profile, values remain relatively low almost all protein residues, indicating structural stability.M0E_3a (pink) exhibits slightly higher fluctuations (0.78 Å) compared to 4M0E_1YL with RMSF 0.71 Å (DK Green) suggesting minor conformational changes upon ligand binding. Figure 5C represents the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of 4TPK_3e (green) and 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red). The overall RMSF profiles of both complexes follow a similar trend, with relatively low fluctuations in most regions of the protein. However, certain residues in the 4TPK_3e complex exhibit higher fluctuations with RMSF 0.89 Å compared to 4TPK_3F9 with RMSF 0.73 Å, particularly in the 1, 72, 526 regions. Both complexes suggest that ligand binding induce localized flexibility.

Fig. 4.

MD simulation analysis of 100 ns trajectories of RMSD of Cα backbone of (A) 2Z5Y_3a (blue) and 2Z5Y_HRM (red) (B) 4M0E_3a (pink) and 4M0E_1YL (DK. Green) (C) 4TPK_3e (green) and 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red).

Fig. 5.

MD simulation analysis of 100 ns trajectories of RMSF of Cα backbone of (A) 2Z5Y_3a (blue) and 2Z5Y_HRM (red) (B) 4M0E_3a (pink) and 4M0E_1YL (DK. Green) (C) 4TPK_3e (green) and 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red).

Figure 6A depicts the Radius of Gyration (Rg) analysis of 2Z5Y_3a (blue) and 2Z5Y_HRM (red). Initially, both complexes exhibit similar Rg values around 25–26 Å, indicating compactness. The 2Z5Y_HRM (red) maintains a relatively stable Rg fluctuating between 23.98 Å and 29.86 Å, suggesting that the protein retains a more compact structure. The 2Z5Y_3a (blue) complex shows higher fluctuations, Rg values between 23.74 Å and 29.52 Å, suggests a conformational flexibility. Figure 6B depicts the Radius of Gyration (Rg) analysis of 4M0E_3a (pink) and 4M0E_1YL (DK. Green). The 4M0E_1YL (DK Green) complex exhibits a stable Rg fluctuate between 22.78 Å and 23.14 Å with minimal deviations. This suggests that the protein maintains its compact structure. The 4M0E_3a (pink) shows high fluctuations in Rg values between 22.68 Å and 27.72 Å, indicating increased flexibility and potential structural instability. Figure 6C depicts the Radius of Gyration (Rg) analysis of 4TPK_3e (green) and 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red). The 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red) maintains Rg between 22.76 Å and 23.17 Å with minimal fluctuations. This suggests that the protein remains structurally stable and compact. The 4TPK_3e (green) shows slightly higher Rg from 22.95 Å to 23.37 Å that induces minor structural flexibility in the protein. Figure S27 illustrates the number of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) formed over time in 2Z5Y_3a (blue) and 2Z5Y_HRM (red). The complex 2Z5Y_3a (blue) exhibits stronger hydrogen bond interactions with protein. The complex maintains a higher number of hydrogen bonds, around 0–6, with occasional spikes. The complex 2Z5Y_HRM (red) exhibits lower number of hydrogen bonds 0–2, indicating weaker hydrogen bonding. Figure 6B illustrates the number of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) formed in 4M0E_3a (pink) and 4M0E_1YL (DK. Green). Both complexes exhibit near about same number of hydrogen bonds 0–4, suggesting stable interactions with protein. Figure 6C illustrates the number of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) formed in 4TPK_3e (green) and 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red). 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red) displays intermittent hydrogen bonds mostly between 0 and 3 whereas 4TPK_3e (green) exhibits a more stable hydrogen bonding maintaining around 2–3 with occasional peaks up to 4. Figure 6D represents the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) analysis, highlighting the conformational changes and stability of ligand when bound to proteins: 2Z5Y_3a (blue), 2Z5Y_HRM (red), 4M0E_3a (pink), 4M0E_1YL (DK. Green), 4TPK_3e (green) and 4TPK_3F9 (DK Red). All complexes show lower SASA in bound receptor state compared to unbound receptor state, suggesting that ligand binding effectively reduces the receptor’s solvent exposure. This reduction in SASA upon binding further implies a stable interaction between ligand and protein.

Fig. 6.

MD simulation analysis of 100 ns trajectories of radius of Gyration (Rg) of Cα backbone of (A) 2Z5Y_3a (blue) and 2Z5Y_HRM (red) (B) 4M0E_3a (pink) and 4M0E_1YL DK).

Protein ligand interactions between the complexes were monitored by simulation studies over the course of 100 ns summarized by stacked colored bars, normalized over the course of trajectories which are categorizes as H-bonds, hydrophobic interactions, Ionic interactions and water bridges. If protein ligand complex has multiple contacts for particular type of interactions, then value remains ≥ 1. Figure 7A–F represents various bar graphs of various types of interaction fractions against residues present over the period of 100 ns. It reveals that high interaction fractions for protein-ligand complex 2Z5Y_3a, 2Z5Y_HRM, 4M0E_3a, 4M0E_1YL, 4TPK_3e and 4TPK_3F9 were made by hydrogen bonding, ionic interaction and water bridges.

Fig. 7.

Bar graph of Protein-ligand contacts of (A) 2Z5Y_3a, (B) 2Z5Y_HRM, (C) 4M0E_3a, (D) 4M0E_1YL, (E) 4TPK_3e and (F) 4TPK_3F9 showing interaction fraction of amino acid residues over the period of simulation.

Figure 8 illustrates the percentage of protein-ligand interactions for the 2Z5Y_3a, ILE180, LYS305, GLY67 interacts 64%, 212% and 134% respectively by forming water bridges. MET445 (14%), TYR69 (52%), LYS305 interacts via hydrogen bonding. TYR444 (16%), TYR69 (17%) interacts via hydrophobic interactions. In 2Z5Y_HRM, GLN215 (88%), ASP338 (48%) PHE208 (36%) and ASN92 (58%) interacts by forming water bridges. PHE208 also interacts 11% by ionic interactions. In 4M0E_3a, PHE338, TYR124, TYR337 interacts 26%, 40% and 34% respectively via hydrophobic interactions. PHE295 (30%), ARG296 (30%), SER293 (124%), TYR341 (66%), TYR72 (24%) interacts by forming water bridges. In 4M0E_1YL, ARG296 (84%) and PHE295 (96%) interacts by hydrogen bonding. TRP286 (86%) interacts via hydrophobic interactions. In 4TPK_3e, ASN289 (39%), ASP70 (46%), TYR332 (17%) SER287 (15%) interacts through hydrogen bonding. ASP70 (24%), PRO285 (26%) interacts via water bridges. In 4TPK_3F9, TRP82 interacts via hydrophobic (12%) as well as ionic interactions (106%). PHE329 (85%), TRP231 (13%) interacts via hydrophobic interactions. Ser287 (24%) and THR120 (72%) interacts via hydrogen bonding.

Fig. 8.

Protein-ligand percent interactions of (A) 2Z5Y_3a, (B) 2Z5Y_HRM, (C) 4M0E_3a, (D) 4M0E_1YL, (E) 4TPK_3e and (F) 4TPK_3F9.

Molecular mechanics generalized born surface area (MM-GBSA) calculations

Utilizing the MD simulation trajectory, the binding free energy along with other contributing energy in form of MM-GBSA were determined for 2Z5Y_3a, 2Z5Y_HRM, 4M0E_3a, 4M0E_1YL, 4TPK_3e and 4TPK_3F9. The results in Table 2 indicate that among all complexes analysed, 4TPK_3F9 exhibits lowest binding free energy (ΔGbind − 79.88 kcal/mol), suggesting strongest binding affinity, while 2Z5Y_HRM (-35.53 kcal/mol) exhibits the weakest binding affinity. The complex 2Z5Y_3a shows highly favourable electrostatic interactions whereas, 2Z5Y_HRM exhibits a repulsive effect, potentially weakening its binding affinity. The covalent interactions remain relatively low across all complexes, with 4TPK_3F9 having the highest value, indicating stabilizing effect. Hydrogen contributions are also minimal. 4M0E_1YL and 2Z5Y_3a exhibits higher hydrogen interactions suggesting that hydrogen bonding plays a secondary role in stabilizing these complexes. The lipophilic contributions are significant, particularly for 4TPK_3F9 and 4M0E_3a, reinforcing their strong binding affinity. The packing contributions are low in all complexes. Solvation effects significantly impact binding. The 2Z5Y_HRM benefits from favourable solvation. Vander Wals interactions play crucible role with 4TPK_3F9, 2Z5Y_3a and 4M0E_3a demonstrating strong stabilizing contribution.

Table 2.

Binding free energy components for the 2Z5Y_3a, 2Z5Y_HRM, 4M0E_3a, 4M0E_1YL, 4TPK_3e and 4TPK_3F9 calculated by MM-GBSA.

| Energies (kcal/mol) |

2Z5Y_3a | 2Z5Y_HRM | 4M0E_3a | 4M0E_1YL | 4TPK_3e | 4TPK_3F9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGbind | -47.39 ± 2.97 | -35.53 ± 1.26 | -61.79 ± 3.95 | -69.18 ± 4.46 | -42.18 ± 2.87 | -79.88 ± 5.14 |

| ΔGbindCoulomb | -81.88 ± 3.71 | 27.15 ± 5.89 | 25.22 ± 4.91 | -17.76 ± 1.34 | -7.08 ± 2.01 | -30.81 ± 5.16 |

| ΔGbindCovalent | -0.27 ± 0.48 | 0.17 ± 0.19 | 1.66 ± 1.18 | 0.70 ± 0.36 | 0.79 ± 0.73 | 2.38 ± 0.75 |

| ΔGbindHbond | -1.02 ± 0.12 | -0.11 ± 0.17 | -0.67 ± 0.14 | -1.05 ± 0.16 | -0.75 ± 0.25 | -0.43 ± 0.10 |

| ΔGbindLipo | -22.39 ± 0.80 | -10.69 ± 0.59 | -28.18 ± 0.88 | -21.28 ± 0.92 | -13.93 ± 0.99 | -31.08 ± 1.47 |

| ΔGbindPacking | -5.40 ± 0.52 | -0.08 ± 0.09 | -3.85 ± 0.56 | -6.63 ± 0.80 | -0.05 ± 0.05 | -4.79 ± 0.50 |

| ΔGbindSolvGB | 121.29 ± 4.55 | -20.44 ± 4.89 | -5.96 ± 6.69 | 22.65 ± 1.38 | 21.61 ± 1.34 | 47.24 ± 4.74 |

| ΔGbindVdW | -57.72 ± 1.41 | -31.53 ± 0.95 | -50.03 ± 2.60 | -45.80 ± 1.84 | -42.78 ± 2.23 | -62.40 ± 2.29 |

DFT study of 3 (a-m)

Frontier molecular orbitals (FMO’s) of synthesized compounds

Utilizing DFT with the B3LYP/6–31 G (d, p) basis set, the optimal geometries of the synthesized molecules 3(a-m) were calculated as shown in Fig. 9. The most significant orbitals in molecules are the FMOs, which have the lowest occupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO). The atoms’ molecular interactions are described by the FMOs.

Fig. 9.

The Optimized structures of compounds 3(a-m).

Additionally, use the frontier orbital gap to assess the molecules’ kinetic stability and chemical reactivity. The molecule is referred to as a soft molecule because it is highly polarized, has a tiny frontier orbital gap, and exhibits strong chemical reactivity and low stability. The HOMO and LUMO energies are used to compute the energy gap (ΔE) between the FMOs. Using the previous reported equations30, the values of the different chemical parameters, including electronegativity (χ), chemical potential (µ), global hardness (η), and electrostatic potential, were computed from the energy gap value. The outcomes were compiled in Table 3. The energy of the HOMO and the LUMO are closely correlated with the ionization potential (I) and electron affinity (A), respectively.

Table 3.

The various quantum chemical parameters of the synthesized compounds 3(a-m).

| Comp. | HOMO | LUMO | ΔE = ELUMO-EHOMO |

(µ) | (ƞ) | χ | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | -5.7113 | -2.9686 | 2.7427 | -7.1956 | -5.8243 | 4.3399 | 4.4449 |

| 3b | -6.2120 | -2.1332 | 4.0787 | -7.2786 | -5.2392 | 4.1726 | 5.0559 |

| 3c | -6.2800 | -2.4761 | 3.8039 | -7.5181 | -5.6161 | 4.3780 | 5.0321 |

| 3d | -6.6555 | -2.6701 | 3.9854 | -7.9906 | -5.9979 | 4.6628 | 5.3227 |

| 3e | -6.3072 | -2.2997 | 4.0074 | -7.4571 | -5.4534 | 4.3035 | 5.0985 |

| 3f | -6.2855 | -2.4872 | 3.7982 | -7.5291 | -5.6300 | 4.3863 | 5.03443 |

| 3g | -5.9617 | -2.3653 | 3.5963 | -7.1443 | -5.3462 | 4.1635 | 4.7736 |

| 3h | -6.6065 | -2.7073 | 3.8991 | -7.9602 | -6.0106 | 4.6569 | 5.2711 |

| 3i | -6.4542 | -2.7101 | 3.7440 | -7.8092 | -5.9372 | 4.5821 | 5.1357 |

| 3j | -6.6827 | -2.6801 | 4.0025 | -8.0228 | -6.0215 | 4.6814 | 5.3446 |

| 3k | -6.7861 | -2.7563 | 4.0298 | -8.1643 | -6.1494 | 4.7712 | 5.4197 |

| 3l | -6.6011 | -2.5631 | 4.0379 | -7.8827 | -5.8637 | 4.5821 | 5.2984 |

| 3m | -6.3344 | -2.3313 | 4.0031 | -7.5001 | -5.4985 | 4.3329 | 5.1151 |

The 3a molecule has the lowest energy gap (ΔE), according to Table 3’s results. This suggests that it is highly reactive chemically and that intramolecular charge transfer from an electron donor (HOMO) to an electron acceptor (LUMO) is greater than that of the other compounds. As a result, compound 3a has lower kinetic stability and functions as a soft molecule.

Due to the presence of the indole moiety in (electron-donating group), compound 3d, 3g and 3k has the highest electronegativity value among synthesized compounds 3k has more electronegative F atom on it. Due to the lower energy gap in 3a other molecules have higher electrophilic index values than the 3a compound. In Fig. 10, the energy gaps between the synthesized molecules are displayed.

Fig. 10.

Molecular orbitals and energies for the HOMO and LUMO of isolated compounds 3(a-m).

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP)

Molecular electrostatic potential diagrams make it simple to identify the molecules’ electrophilic and nucleophilic areas. Consequently, the charge distribution and associated electrostatic potential value are revealed. The red and blue portions of the MEP map indicate the atoms’ electron densities31. Red/yellow coloration denotes the electron ring centers with a negative potential value, green denotes the neutral potential value, and blue denotes the electron-poor regions with a positive potential value32. The MEP diagrams of the synthesized molecules 3(a-p) are displayed in Fig. 11. The MEP surfaces of the synthesized molecules 3(a-p) were computed at DFT/B3LYP using the basis set of 6–31 G (d, p) level. The oxygen atoms have the largest negative potential region, while the nitrogen atoms have the least negative potential, as seen in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Molecular electrostatic potential surface of compounds 3(a-m).

The hydrogen atom connected to the six-membered rings achieved the positive potential. The various hues served as a representation of the synthesized molecules’ electrostatic potential values. Table 3 provided a summary of the 3(a-p) electrostatic potential.

Electron density analysis/RDG

The non-covalent interactions found in the synthesized compounds (3a-m) were investigated using the Multiwfn software, and the pictures produced were shown using VMD. The RDG v/s sign of (λ2)*ρ was plotted in Fig. 12 to show the 2D and 3D iso surfaces of the synthesized molecules. The weak intramolecular and intermolecular interactions in molecules resulting from the quantum-mechanical electron density have been studied using Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) analysis33. A key dimensionless quantity in RDG, the electron density value tells us how strong the interactions are. RDG is described as

Fig. 12.

A 3D and 2D RDG isosurface plots of the synthesized compounds 3 (a-m).

|

1 |

where the eigenvalue is a sign of (λ2), the electron density is represented by ρ(r), and the electron density norm is represented by Δρ(r)34. The Vander Waals interaction is shown in green in Fig. 12, whereas red denotes a high repulsion and blue denotes a strong attractive interaction. In addition to the 2D plots of RDG that show hydrogen bonding from 0.05 to 0.02 a.u., the peaks from 0.02 to + 0.01 a.u. indicate the presence of non-covalent contact and 0.02 to 0.05 a.u. indicate high repulsion between the molecules’ atoms. The 3D graph shows that the phenyl, indole, thiophene and furan nuclei of the synthesized compounds 3(a-m) exhibit significant repulsive interactions.

Experimental

Materials and methods

All the chemicals were purchased from Fluka Chemie AG Buchs and Sigma Aldrich and used without further purification. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel 60 F254 aluminum sheets. The mobile phase was ethyl acetate: petroleum ether (1:1) and detection was made using UV light. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were registered in DMSO on Bruker NMR instrument with Topspin software (400 MHz and 101 MHZ) respectively. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) spectra were obtained using the electrospray ionization (ESI) technique on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Q Exactive™ Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ instrument. HPLC chromatograms were recorded using a Waters e2695 HPLC instrument controlled by Empower 3 software. The analysis was performed with a 1:4 water: MeCN mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, and peaks were detected using a PDA detector (model 2998) at 363 nm.

Synthesis of compound 3 (a-m)

The target compounds 3(a-m) were synthesized by the condensation reaction Scheme 1. Coumarin derivative 1 (0.1 g,0.45mmol) was dissolved in Abs. EtOH with the help of a catalyst CH3COOH (3–4 drops). After completely dissolving 1 hydrazide derivative (0.1 g, 0.45 mmol) was added. The reaction is reflux at 80 °C for 5–6 h. The progress of reaction is checked through TLC and after consumptions of starting material, formed precipitate were hot filtered and washed with hot EtOH. The precipitates were dried in oven at 50 °C overnight and then characterized by 1HNMR and 13CNMR, HRMS and HPLC (SI).

(E)-3-Hydroxy-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)-2-naphthohydrazide (3a)

Yield 89%, Orange color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.76 (s, 1H), 11.62 (s, 1H), 8.66 (s, 1H), 8.27 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (dd, J = 6.5, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.33 (m, 4 H), 3.95 (s, 3 H), 2.34 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 162.1, 159.5, 153.1, 150.9, 146.8, 143.3, 142.4, 136.3, 133.0, 129.4, 128.8, 127.7, 127.1, 126.2, 125.2, 124.4, 121.1, 120.8, 119.8, 115.2, 111.2, 56.6, 16.2. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C23H18N2O5, calculated [M + H]+: 403.413, found [M + H]+: 403.126. HPLC: rt: 5.33 min, 97.76%.

(E)-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)-2-(1 H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridin-1-yl)acetohydrazide (3b)

Yield 91%, white color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 11.01 (s, 1H), 8.35 (s, 1H), 8.23–8.19 (m, 1H), 8.00–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 6.6, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.31 (m, 2 H), 7.12–7.08 (m, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 5.51 (s, 2 H), 3.93 (s, 3 H), 2.25 (s, 3 H).13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.64, 159.33, 148.09, 147.29, 146.79, 143.23, 142.57, 142.17, 131.03, 128.83, 127.14, 125.18, 120.77, 120.50, 119.93, 116.11, 115.13, 99.53, 56.63, 46.16, 16.13. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula C21H18N4O4, calculated [M + H]+: 391.406, found [M + H]+: 391.138. HPLC: rt: 0.54 min, 99.72%.

(E)-2-bromo-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)benzohydrazide (3c)

Yield 88%, white color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.89 (s, 1H), 8.23 (s, 1H), 7.43 (q, J = 10.4 Hz, 3 H), 7.33–7.23 (m, 6 H), 3.93 (s, 3 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.03, 163.72, 159.41, 153.17, 146.78, 143.30, 142.47, 141.49, 135.94, 131.72, 130.96, 130.08, 127.31, 125.22, 120.85, 119.48, 115.21, 56.62, 17.00. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C19H15BrN2O4, calculated [M + H]+: 417.028, found [M + H]+: 417.025. HPLC: rt: 4.47 min, 100%.

(E)-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)-2-methylbenzohydrazide (3d)

Yield 92%, light-yellow color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) (s, 1H), 8.08–8.06 (m, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.82 (s, 1H), 7.34 (td, J = 6.2, 2.5 Hz, 3 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.51 (q, J = 1.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.35 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.50, 146.79, 143.26, 142.22, 136.93, 127.56, 127.37, 126.61, 126.02, 125.20, 124.89, 120.74, 120.71, 120.09, 119.87, 115.10, 101.86, 56.62, 24.01, 16.60. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C20H18N2O4, calculated [M + H]+: 351.381, found [M + H]+: 351.132. HPLC: rt: 4.46 min, 99.99%.

(E)-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)-4-(trifluoromethyl) benzohydrazide (3e)

Yield 90%, yellow color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.68 (s, 1H), 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.50–7.35 (m, 2 H), 7.44–7.29 (m, 3 H), 6.69 (dd, J = 3.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.32 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 159.0, 146.3, 142.7, 141.7, 136.4, 127.0, 126.9, 126.1, 125.5, 124.7, 124.4, 120.2, 119.6, 119.4, 114.6, 101.3, 56.1, 16.1. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C20H15F3N2O4, calculated [M + H]+: 405.352, found [M + H]+: 405.104. HPLC: rt: 4.52 min, 100%.

(E)-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)furan-2-carbohydrazide (3f)

Yield 89%, off-white color, Yield 80%, greenish color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.68 (s, 1H), 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.48–7.29 (m, 4 H), 6.69 (dd, J = 3.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.32 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 177.49, 159.16, 147.39, 146.78, 143.01, 138.88, 131.47, 131.30, 127.59, 126.19, 125.18, 120.78, 119.89, 117.94, 115.18, 56.63, 16.66. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C17H14N2O5, calculated [M + H]+: 327.315, found [M + H] + 327.096. HPLC: rt: 4.44 min, 100%.

(E)-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)-1 H-indole-4-carbohydrazide (3g)

Yield 92%, yellow color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.76 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 10.31 (s, 1H), 8.46 (s, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2 H), 7.50–7.46 (m, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 6.0, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.22–7.14 (m, 2 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.34 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.55, 159.42, 153.20, 146.77, 143.30, 142.45, 138.08, 133.18, 132.51, 131.82, 131.01, 130.02, 128.07, 127.31, 125.21, 120.86, 120.02, 119.81, 119.47, 115.20, 56.63, 17.03. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C21H17N3O4, calculated [M + H]+: 376.391, found [M + H]+: 376.127. HPLC: rt: 4.48 min, 99.90%.

(E)-3-chloro-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)benzohydrazide (3h)

Yield 87%, brown color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.92 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.58–7.53 (m, 1H), 7.41–7.30 (m, 3 H), 3.94 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.35 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 177.54, 159.16, 146.93, 146.77, 144.27, 143.18, 142.94, 139.45, 128.66, 128.51, 126.19, 125.81, 125.68, 125.16, 120.77, 119.93, 115.14, 56.63, 16.59. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C19H15ClN2O4, calculated [M + H]+: 371.796, found [M + H]+: 371.078. HPLC: rt: 4.78 min, 98.61%.

(E)-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)-2-phenylacetohydrazide (3i)

Yield 85%, white color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.67 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.29 (m, 6 H), 7.30–7.21 (m, 3 H), 3.92 (s, 3 H), 3.32 (s, 2 H), 2.22 (d, J = 25.0 Hz, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 177.91, 159.23, 157.47, 146.77, 146.74, 143.19, 142.86, 132.37, 127.56, 127.51, 126.28, 125.15, 120.76, 119.94, 115.11, 113.86, 113.74, 56.63, 55.74, 16.59. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C20H18N2O4, calculated [M + H]+: 351.381, found [M + H]+: 351.132. HPLC: rt: 4.67 min, 95.61%.

(E)-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)thiophene-2-carbohydrazide (3j)

Yield 90%, yellow color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.08 (s, 1H), 9.22 (d, J = 50.3 Hz, 1H), 8.89 (d, J = 54.8 Hz, 2 H), 8.24 (d, J = 21.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50–7.27 (m, 3 H), 3.94 (s, 3 H), 2.35 (d, J = 18.2 Hz, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 177.54, 159.16, 146.93, 146.77, 143.18, 142.94, 139.45, 128.66, 128.51, 126.19, 125.81, 125.68, 125.16, 120.77, 119.93, 115.14, 56.63, 16.59. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C17H14N2O4S, calculated [M + H]+: 343.376, found [M + H]+: 343.073. HPLC: rt: 4.56 min, 97.05%.

(E)-4-fluoro-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)benzohydrazide (3k)

Yield 95%, yellow color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.13 (s, 1H), 8.74 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.21–8.04 (m, 2 H), 7.71 (dd, J = 7.5, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.48–7.41 (m, 1H), 7.39–7.32 (m, 2 H), 3.95 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 3 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 179.94, 160.65, 159.39, 158.17, 148.17, 146.81, 143.27, 142.91, 129.54, 126.35, 125.20, 120.76, 119.86, 117.31, 115.20, 112.34, 112.11, 56.63, 16.96. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C19H15FN2O4, calculated [M + H]+: 355.344, found [M + H]+: 355.107. HPLC: rt: 4.91 min, 99.90%.

(E)-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)picolinohydrazide (3l)

Yield 89%, white color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.04 (s, 1H), 8.24 (s, 1H), 8.10–8.02 (m, 1H), 7.91–7.85 (m, 1H), 7.41 (dd, J = 6.9, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.30 (m, 2 H), 7.28 (dd, J = 7.5, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 3 H), 2.30 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 177.59, 159.20, 148.19, 147.82, 146.79, 143.23, 143.15, 140.69, 131.76, 129.83, 126.24, 125.22, 120.81, 120.14, 119.57, 115.23, 56.63, 16.79. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C18H15N3O4, calculated [M + H]+: 338.342, found [M + H]+: 338.112. HPLC: rt: 4.86 min, 99.79%.

(E)-2-chloro-N’-(1-(8-methoxy-2-oxo-2 H-chromen-3-yl)ethylidene)benzohydrazide (3m)

Yield 88%, yellow color, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.94 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.58–7.53 (m, 1H), 7.44–7.36 (m, 1H), 7.34–7.31 (m, 2 H), 3.94 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.35 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 178.45, 159.21, 147.68, 146.80, 143.25, 142.92, 139.03, 132.15, 129.85, 129.03, 128.75, 128.10, 126.25, 125.21, 120.74, 119.87, 115.23, 56.64, 16.87. ESI-HRMS: m/z Formula: C19H15ClN2O4, calculated [M + H]+: 371.796, found [M + H]+: 371.078. HPLC: rt: 4.87 min, 100%.

Molecular docking

In this study, we have selected X-ray crystallographic structures of target proteins Human Acetylcholinesterase (hAChE), Human Butyrylcholinesterase (hBChE) and Human Monoamine oxidase-A (MAO-A), having PDB IDs 7XN1, 6QAA, and 2Z5Y respectively which were retrieved from RCSB protein data bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). While selecting a set of proteins for docking study, each PDB was validated for X-ray crystallographic method for resolution, resolution below 2 Å, wwPDB validation should be better, presence of native ligand and Ramachandran plot Fig. 3.

The target protein refinement was performed using CHIMERA V1.16 to ensure high-quality input for docking study, where standard residues present in the protein were minimized using AMBER force field, while non-standard residues were minimized using AM1-BCC semi-empirical charges to maintain proper electrostatic interactions. Non-essential residues like water, co-crystal ligands and unnecessary chains were removed, which may interfere in the docking procedure. The structures of the ligands were drawn in Marvin Sketch, hydrogens were added, opt for 2D and 3d clean, possible conformers were generated from which the lowest energy conformer was selected and saved in mol2 format. Then structures were optimized through CHIMERA using the AM1-BCC force field. Proteins and ligands were converted to PDBQT format using AutoDockTools, which can be readable by Vina tool. In AutoDockTools, the rotatable bonds in the ligands were identified and made flexible during the docking study for conformational variability. The protein was kept rigid, while the ligand’s flexibility was explicitly considered through flexible rotatable bonds. It is important to note that docking was performed without explicit solvent conditions. Active site amino acids were identified for selected targets based on the presence of the cocrystal ligand. The amino acid present in the active site of 4M0E are PHE295A, TYR72A, ASP74A, TYR124A, TRP286A, SER293A, VAL294A, PHE295A, PHE297A, TYR337A, PHE338A, TYR341A, while in 4TPK are ASN68A, ILE69A, ASP70A, TRP82A, GLY116A, GLY117A, THR120A, GLU197A, SER198A, TRP231A, PHE329A, TYR332A, PHE398A, GLY439A and in 2Z5Y are ILE180A, ASN181A, PHE208A, GLN215A, CYS323A, ILE335A, LEU337A, PHE352A, TYR407A, TYR444A. Then the Grid box was defined around the active site and the grid dimensions were optimized to encompass the protein ligand interactions. According to the active site, grid centers were defined around the native ligand, which were found for 4M0E, were X= -17.32, Y= -42.32, Z = 25.95, for 4TPK are X = 4.32, Y = 10.54, Z = 13.87, and for 2Z5Y are X= -40.58, Y= -26.77, Z= -14.68. and grid size was set to X = Y = Z = 20 for all proteins. The docking protocol was meticulously designed to reflect insights into interactions between protein-ligand complexes. We used Autodock Vina V. 1.2.6 for molecular docking. The docking parameters were optimized by multiple docking runs using various grid sizes and based on different tools to identify the best binding pose and replicable results like spacing (0.375 Å), num_modes (9), energy range (3), exhaustiveness (16) and other default configurations. Docking results were visualized through Biovia Discovery Studio visualization tool and Maestro 12.3 (Academic Edition) for structural analysis, and binding interactions were noted in the table.

Molecular dynamics simulation (MDs)

The Desmond 2023 from Schrödinger, LLC, 2023 was used to run MD simulations on dock complexes 2Z5Y with 3a and HRM, 4M0E with 3a and 1YT, 4TPK with 3e and 3F9 represented as 2Z5Y_3a, 2Z5Y_HRM, 4M0E_3a, 4M0E_1YT, 4TPK_3e, 4TPK_3F9 respectively. The OPLS-2005 force field and explicit solvent model with the TIP3P water molecules were used in this system in period boundary salvation box of 10 Å x 10 Å x 10 Å dimensions. Na + ions were added to neutralize the charge 0.15 M, and NaCl solutions were added to the system to simulate the physiological environment. Initially, the system was equilibrated using an NVT ensemble for 10 ns to retrain over the protein-ligand complexes. Following the previous step, a short run of equilibration and minimization was carried out using an NPT ensemble for 12 ns. The NPT ensemble was set up using the Nose-Hoover chain coupling scheme with varying temperatures, relaxation time of 1.0 ps, and pressure of 1 bar maintained in all the simulations. A time step of 2 fs was used. The Martyna-Tuckerman–Klein chain coupling scheme barostat method was used for pressure control with a relaxation time of 2 ps. The particle mesh Ewald method was used for calculating long-range electrostatic interactions, and the radius for the coulomb interactions was fixed at 9Å. The final production run was carried out for 100 ns. The root means square deviation (RMSD), the radius of gyration (Rg), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and a number of hydrogen (H-bonds), salt bridges and SASA are calculated to monitor the stability of the MD simulations.

Binding free energy analysis

The molecular mechanics combined with the generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA) approach was used to compute the binding free energies of the ligand-protein complexes. The Prime MM-GBSA binding free energy was calculated using the Python script thermal mmgbsa.py in the simulation trajectory for last 50 frames with a 1-step sampling size. The binding free energy of Prime MM-GBSA (kcal/mol) was estimated using the principle of additivity, in which individual energy modules such as columbic, covalent, hydrogen bond, vander Waals, self-contact, lipophilic, solvation of protein and ligand were collectively added. The equation used to calculate ΔGbind is the following:

|

Where

ΔGbind designates the binding free energy,

ΔGMM designates the difference between the free energies of ligand-protein complexes and the total energies of protein and ligand in isolated form,

ΔGSolv designates the difference in the GSA solvation energies of the ligand-receptor complex and the sum of the solvation energies of the receptor and the ligand in the unbound state,

ΔGSA designates the difference in the surface area energies for the protein and the ligand.

DFT study

DFT is often used to investigate the electronic characteristics of therapeutic compounds that have been synthesized. The Gaussian 09 software35 was used to optimize the geometry of all the compounds under investigation in the gaseous phase by incorporating the Becke, Lee-Yang-Parr (B3LYP) exchange-correlation functional36, and 6-311 + G(d, p) basis set. To forecast the chemical reactivity of each of these compounds, the dipole moment, polarizability, and energy gap (ΔE) of FMO-Frontier Molecular Orbitals—which include the HOMO (highest occupied molecular orbital) and the LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital)—were calculated. Koopman’s theorem37 was used to derive the other significant electronic properties, such as the electrophilicity index (ω), chemical potential (µ), softness (S), and hardness (η). GaussView 6 software was used to visualize the geometry of every compound under investigation38.

Enzymes assays

In bioactivity investigations, enzyme inhibition was examined using a slightly altered colorimetric Ellman method39. Acetylthiocholine iodide (AChI) and butyrylthiocholine iodide (BChI) were used as substrates in the reaction. Utilizing 5,5’-Dithio-bis(2-nitro-benzoic)acid (DTNB), the activity of AChE and BChE were measured. The activity involved adding 10 mL of sample solution at different concentrations to deionized water together with 1.0 mL of Tris/HCl buffer (1.0 M, pH 8.0). After mixing 50 mL of AChE or BChE solution, the final solution was incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. After incubation, 50 mL of DTNB (0.5 mM) was added. The reaction was allowed to start when 50 mL of AChI or BChI was introduced40–42. A spectrophotometric indicator of the hydrolysis of these substrates was the formation of the yellow 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoate anion, which is the result of the interaction between DTNB and thiocholine generated by the enzymatic hydrolysis of AChI or BChI. This anion has a maximum absorbance at 412 nm. To calculate IC50 values, activity (%) vs. chemical plots were employed. However, Ki values were calculated using the Lineweaver-Burk graph43. Acetylcholinesterase from Electrophorus electricus (electric eel) and Butyrylcholinesterase from equine serum were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Additionally, the inhibitory activity of each freshly synthesized compound against hMAO-A was assessed using the in vitro fluorometric technique. The oxired reagent (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine), which is used as an MAO substrate in a horseradish peroxidase coupling reaction, detects H2O2, which is the product of tyramine’s oxidative deamination. First, the 10–3 and 10–4 M concentrations of each chemical were examined. In order to determine the IC50 value for the hMAO-A isoform as reported in earlier research, compounds that showed inhibitory activity at a concentration of 10− 5-10− 9 M greater than 50% were subjected to further study in the second phase44. The supplier of the enzymes was Sigma Aldrich. (M7441: Human Monoamine Oxidase A and M7316: Human Monoamine Oxidase A).

Conclusion

In this study, we reported coumarin substituted hydrazone 3(a-m) with good yield. Using spectroscopic methods, the structures of every synthesized compound were verified. These synthetic compounds have been subjected to computational investigations using the DFT/B3LYP level with a 6–31 G (d, p) basis set in order to get optimal geometries, FMOs, MEP, and characteristics. The capacity of synthesized compounds to inhibit cholinesterase enzymes was examined. The acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme was significantly inhibited by compounds 3a, 3e, and 3l. Moreover, the butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) enzyme was also significantly inhibited by these substances. To see how the most potent inhibitor chemicals affected the substrate–enzyme relationship, enzyme kinetic tests were conducted in addition to enzyme inhibition investigations. Compound 3a exhibits the strongest binding affinity toward hAChE (PDB ID: 4M0E) and MAO-A (PDB ID: 2Z5Y), primarily through hydrophobic interactions. Studies suggest that molecules combining hydrophobic moieties, aromatic rings, π-π stacking interactions, and polar functional groups capable of hydrogen bonding tend to show enhanced enzyme affinity and inhibitory activity. The 2Z5Y_HRM complex, in particular, benefits from favorable solvation effects. Additionally, van der Waals interactions play a critical role in stabilization, as seen in the strong contributions observed in the 4TPK_3F9, 2Z5Y_3a, and 4M0E_3a complexes. Compound 3e may function as a dual binding site AChE inhibitor, according to docking studies in addition to in vitro testing.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia, through Large Research Project under grant number RGP-2/694/46.

Author contributions

Wajeeha Zareen: Investigation, Formal analysis. Nadeem Ahmed, Mostafa A. Ismail: Formal analysis, Validation, Data curation. Maham Rafique, Ajmal Khan : Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation. Nastaran Sadeghian, Parham Taslimi: Biological Activity, Data curation, Software. Muhammad Tahir : DFT Study. Suraj N. Mali, Somdatta Y. Chaudhari: Docking, MD simulation. Halil Şenol: Data curation, Software, Writing- review & editing. Zahid Shafiq, Ali Muhammad Khan : Writing –original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia, through Large Research Project under grant number RGP-2/694/46.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ajmal Khan, Email: ajmalkhan@unizwa.edu.om.

Zahid Shafiq, Email: zahidshafiq@bzu.edu.pk.

References

- 1.Landau, S. M. et al. Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann. Neurol.72 (4), 578–586 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francis, P. T., Palmer, A. M., Snape, M. & Wilcock, G. K. The cholinergic hypothesis of alzheimer’s disease: a review of progress. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 66 (2), 137–147 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang, L., Xiang, Q., Xiang, J., Zhang, Y. & Li, J. Tripterygium glycoside ameliorates neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Aβ25-35-induced alzheimer’s disease by inhibiting the phosphorylation of IκBα and p38. Bioengineered12 (1), 8540–8554 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu, B., Xiao, Q., Zhu, L., Tang, H. & Peng, W. Icariin targets p53 to protect against ceramide-induced neuronal senescence: implication in alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med.224, 204–219 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang, L. et al. Expression profiles of long noncoding RNAs in intranasal LPS-Mediated alzheimer’s disease model in mice. Biomed. Res. Int.2019 (1), 9642589 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Islam, B. & Tabrez, S. Management of alzheimer’s disease—an insight of the enzymatic and other novel potential targets. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.97, 700–709 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaweska, H. & Fitzpatrick, P. F. Structures and mechanism of the monoamine oxidase family. Biomol. Concepts. 2 (5), 365–377 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behl, T. et al. Role of monoamine oxidase activity in alzheimer’s disease: an insight into the therapeutic potential of inhibitors. Molecules26, 12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Tok, F. Recent studies on heterocyclic cholinesterase inhibitors against Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Biodivers.2024, e202402837 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Abd El-Mageed, M. M., Ezzat, M. A. F., Moussa, S. A., Abdel-Aziz, H. A. & Elmasry, G. F. Rational design, synthesis and computational studies of multi-targeted anti-Alzheimer’s agents integrating coumarin scaffold. Bioorg. Chem.154, 108024 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogawa, K., Shima, K., Korogi, S., Korematsu, N. & Morinaga, O. Locomotor-reducing, sedative, and antidepressant-like effects of confectionery flavours coumarin and Vanillin. Biol. Pharm. Bull.47 (10), 1768–1773 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayed, E. A. et al. Pyrano-coumarin hybrids as potential antimicrobial agents against MRSA strains: design, synthesis, ADMET, molecular docking studies, as DNA gyrase inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct.1295, 136663 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mustafa, Y. F. Combretastatin A4-based coumarins: synthesis, anticancer, oxidative stress-relieving, anti-inflammatory, biosafety, and in Silico analysis. Chem. Pap.78 (6), 3705–3720 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeki, N. M. & Mustafa, Y. F. Coumarin hybrids for targeted therapies: a promising approach for potential drug candidates. Phytochem. Lett.60, 117–133 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao, X. et al. Coumarin-Quinazolinone based photosensitizers: mitochondria and Endoplasmic reticulum targeting for enhanced phototherapy via different cell death pathways. Eur. J. Med. Chem.280, 116990 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh, A. et al. Development of coumarin-inspired bifunctional hybrids as a new class of anti-Alzheimer’s agents with potent in vivo efficacy. RSC Med. Chem. (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Orioli, R., Belluti, F., Gobbi, S., Rampa, A. & Bisi, A. Naturally inspired coumarin derivatives in alzheimer’s disease drug discovery: latest advances and current challenges. Molecules29 (15), 3514 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Damasy, A. K. et al. Novel coumarin benzamides as potent and reversible monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors: Design, synthesis, and neuroprotective effects. Bioorg. Chem.142, 106939 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovannuzzi, S. et al. Dual inhibitors of brain carbonic anhydrases and monoamine oxidase-B efficiently protect against amyloid-β-induced neuronal toxicity, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Med. Chem.67 (5), 4170–4193 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Çakmak, R., Başaran, E., Sahin, K., Şentürk, M. & Durdağı, S. Synthesis of novel hydrazide–hydrazone compounds and in vitro and in Silico investigation of their biological activities against AChE, BChE, and hCA I and II. ACS Omega9 (18), 20030–20041 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim, M. et al. Synthesis, in-vitro evaluation and in-silico analysis of new anticholinesterase inhibitors based on Sulfinylbis (acylhydrazones) scaffolds. J. Mol. Struct.2025, 141796 (2025).

- 22.Frias, C. C., Antoniolli, G., Barros, W. P. & Almeida, W. P. Acylhydrazones derived from Isonicotinic acid: synthesis, characterization, and evaluation against alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. J. Mol. Struct.1313, 138631 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Younis, A., Kassem, A. F., Aboulthana, W. M. & Sediek, A. A. Green synthesis, molecular docking and in vitro biological evaluation of novel hydrazones, pyrazoles, 1, 2, 4-triazoles and 1, 3, 4-oxadiazoles. Synth. Commun.54 (22), 1984–2002 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahvecioglu, D. et al. Synthesis and molecular docking analysis of novel hydrazone and Thiosemicarbazide derivatives incorporating a pyrimidine ring: exploring neuroprotective activity. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.2024, 1–15. (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sztanke, M., Wilk, A. & Sztanke, K. An insight into fluorinated Imines and hydrazones as antibacterial agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25 (6), 3341 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parameshwaraiah, S. M. et al. Development of novel Indazolyl-Acyl hydrazones as antioxidant and anticancer agents that target VEGFR‐2 in human breast cancer cells. Chem. Biodivers.21 (3), e202301950 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geetha, D. et al. Novel series of hydrazones carrying pyrazole and Triazole moiety: Synthesis, structural elucidation, quantum computational studies and antiviral activity against SARS-Cov-2. J. Mol. Struct.1317, 139016 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang, F. et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of hydrazones as dual inhibitors of Ryanodine receptors and acetylcholinesterases for alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Chem.133, 106432 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dincel, E. D. et al. Discovery of Dual‐Inhibitor acyl hydrazones for acetylcholinesterase and carbonic anhydrase I/II: A mechanistic insight into alzheimer’s disease. ChemistrySelect10 (9), e202405876 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalid, M. et al. O-4-Acetylamino-benzenesulfonylated pyrimidine derivatives: synthesis, SC-XRD, DFT analysis and electronic behaviour investigation. J. Mol. Struct.1224, 129308 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sezgin, B., Tilki, T., Karabacak Atay, Ç. & Dede, B. Comparative in vitro and DFT antioxidant studies of phenolic group substituted pyridine-based Azo derivatives. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.40 (11), 4921–4932 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahilu, R., Eswaramoorthy, R., Mulugeta, E. & Dekebo, A. Synthesis, DFT analysis, dyeing potential and evaluation of antibacterial activities of Azo dye derivatives combined with in-silico molecular docking and ADMET predictions. J. Mol. Struct.1265, 133279 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng, X., Song, L., Han, H., Zhao, J. & Zheng, D. Solvent Polarity dependent ESIPT behavior for the novel flavonoid-based solvatofluorochromic chemosensors. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.265, 120383 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kara, Y. S., Eşme, A. & Sagdinc, S. TDOS/PDOS/OPDOS, reduced density gradient (RDG) and molecular Docking studies of [3-(3-bromophenyl)-cis-4,5-dihydroisoxazole-4,5-diyl]bis(methylene) diacetate, Balıkesir Üniversitesi. Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi. 24 (1), 100–110 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chai, J. D. & Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.10 (44), 6615–6620 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys.98 (7), 5648–5652 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuneda, T., Song, J. W., Suzuki, S. & Hirao, K. On koopmans’ theorem in density functional theory. J. Chem. Phys.133, 17 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Basha, F., Khan, F. L. A., Muthu, S. & Raja, M. Computational evaluation on molecular structure (Monomer, Dimer), RDG, ELF, electronic (HOMO-LUMO, MEP) properties, and spectroscopic profiling of 8-Quinolinesulfonamide with molecular Docking studies. Comput. Theor. Chem.1198, 113169 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellman, G. L., Courtney, K. D., Andres, V. Jr. & Feather-Stone, R. M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol.7, 88–95 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aktas, A. et al. A novel Ag-N-heterocyclic carbene complex bearing the hydroxyethyl ligand: synthesis, characterization, crystal and spectral structures and bioactivity properties. Crystals10 (3), 171 (2020).

- 41.Mamedova, G. et al. Novel Tribenzylaminobenzolsulphonylimine based on their pyrazine and pyridazines: Synthesis, characterization, antidiabetic, anticancer, anticholinergic, and molecular Docking studies. Bioorg. Chem.93, 103313 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zareen, W. et al. Synthesis, antidiabetic evaluation, and computational modeling of 3-acetyl-8-ethoxy coumarin derived hydrazones and thiosemicarbazones. RSC Adv.15 (46), 39043–39058 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ekiz, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and SAR of arylated indenoquinoline-based cholinesterase and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim). 351 (9), e1800167 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Egger, K., Aicher, H. D., Cumming, P. & Scheidegger, M. Neurobiological research on N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and its potentiation by monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibition: from Ayahuasca to synthetic combinations of DMT and MAO inhibitors, cellular and molecular life sciences. CMLS81 (1), 395 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files.