Abstract

Background

Cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) is becoming more common. Current prognostic markers—TNM stage, BRAF mutation status, and tumor mutational burden (TMB)—do not offer precise predictions. Recent studies point to a key role for the tumor microenvironment. To date, we do not know how SIGLEC8 (a sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin‑like lectin) affects immune regulation or prognosis in SKCM.

Methods

We used logistic regression to link SIGLEC8 expression with clinical and pathological features. We then applied Cox regression and Kaplan‑Meier survival analysis to assess how these features relate to overall survival (OS). For differential genes, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG enrichment tests by combining fold‑change thresholds with hypergeometric statistics. Finally, we ran Pearson and Spearman correlations to study the relationship between SIGLEC8 and immune‑infiltration markers.

Results

From TCGA, we selected SKCM cases that had both complete clinical records and transcriptome data. We excluded 8.2% of samples due to missing information; this did not introduce any bias in age or sex. Patients with low SIGLEC8 levels tended to have T4 tumors, Breslow depth over 3 mm, ulceration, and more advanced disease (p < 0.05). High SIGLEC8 expression was linked to better OS (p < 0.001) in Cox analysis. This prognostic value held true across subgroups defined by age, gender, BMI, and stage (all p < 0.05). Differential expression analysis highlighted three immune genes—FCER2, CR2, and MS4A1—as strongly correlated with SIGLEC8. These findings point to a role in B‑cell and CD8⁺ T‑cell pathways within the hematopoietic lineage.

Conclusions

High SIGLEC8 expression predicts longer survival in SKCM. We propose that SIGLEC8 boosts antitumor immunity by influencing B‑cell and T‑cell pathways (including FCER2, CR2, MS4A1, and CD8A/B) in the tumor microenvironment. SIGLEC8 thus shows promise as a low‑cost prognostic biomarker and a potential therapeutic target. Table S1 shows cancer-type-specific prognostic effects for SIGLEC8: in SKCM higher SIGLEC8 expression associates with improved survival, whereas prognostic directionality varies across other tumor types. A pan-cancer comparison revealed cancer-type-specific prognostic effects for SIGLEC8: in SKCM higher SIGLEC8 expression associates with improved survival, whereas prognostic directionality varies across other tumor types.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-03935-9.

Keywords: SIGLEC8, SKCM, Prognostic biomarker, TCGA, Tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Skin Cutaneous Melanoma (SKCM) is a malignant tumor arising from melanocytes, primarily affecting the skin [1]. In recent years, due to increased UV exposure caused by ozone layer depletion and changes in lifestyle, its global incidence has been steadily rising. In Europe, this disease has ranked among the top ten most common malignancies [2, 3]. Epidemiological data shows that melanoma accounts for over 90% of skin cancer-related deaths, with geographical variations: the incidence rate in Europe is approximately 10–25 cases per 100,000 residents, 20–30 cases in the United States, and as high as 50–60 cases in Australia, ranking first in the world. It’s worth noting that the incidence rate among European men over 60 years old is sharply increasing, and the incidence rate across all age groups is generally rising, suggesting a further increase in the disease burden in the future [4]. Studies have indicated that approximately 20–30% of melanoma patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage (Stage III-IV), with a 5-year survival rate of less than 20% for patients with distant metastasis (Stage IV), highlighting its high aggressiveness and treatment difficulties [3, 5]. Currently, clinical prognosis assessment mainly relies on indicators such as TNM staging, Breslow thickness, and ulceration status, but the existing system provides limited guidance for individualized treatment [6]. Despite the description of several promising biomarkers, such as the expression of immune-related genes or mutations in the IFN signaling pathway, besides BRAF and KIT mutations and tumor mutation load, there are currently no clinically validated predictive markers in melanoma [5]. Therefore, exploring new molecular markers to optimize risk stratification and treatment strategies is of great significance. SIGLEC8 (Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 8) is a glycoprotein belonging to the CD33-related family, widely expressed on immune cells, particularly at higher levels in eosinophils. Studies have shown that altered SIGLEC8 expression in various cancers may be closely related to tumorigenesis, progression, and immune evasion mechanisms [7]. Currently, SIGLEC8 is being explored as a potential therapeutic target in multiple cancer studies; however, its role in cutaneous melanoma remains unclear. Recent progress in computational oncology has emphasized the value of analyzing the tumor microenvironment (TME) to gain insight into cancer development and responses to treatment. For example, Fang et al. introduced the Immuno-Oncology Biological Research (IOBR) toolkit. This platform integrates multi-omics datasets to comprehensively characterize TME components, ligand–receptor pairs, and genome–TME interactions. They demonstrated that IOBR can effectively predict immunotherapy outcomes across several tumor types [8]. Similarly, Zhang et al. applied an optimized dynamic network biomarker (DNB) strategy to differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Their work revealed detailed heterogeneity in molecular subtypes and identified distinct immune microenvironments [9].In addition, the gut microbiome has been recognized as an important regulator of antitumor immunity. In melanoma patients treated with anti–PD-1 antibodies, those who responded to therapy showed significantly higher microbial diversity and enrichment of specific bacterial taxa. These features were associated with increased infiltration of cytotoxic T cells [10, 11]. Taken together, these findings illustrate the major impact of both intrinsic factors within tumors and extrinsic influences, such as the microbiome, on TME behavior. This understanding provided the rationale for our examination of SIGLEC8 in cutaneous melanoma. Based on these considerations, our study uses transcriptomic and clinical information from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to assess how SIGLEC8 expression relates to clinicopathological variables and patient prognosis. In addition, we investigate its potential functional pathways using gene set enrichment analysis. The results are expected to offer new prognostic markers for cutaneous melanoma and provide theoretical support for therapies targeting the immune microenvironment.

Materials and methods

Data source and preprocessing

In this study, we downloaded and organized the RNA-seq data from the TCGA-SKCM project’s STAR pipeline from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). We extracted data in TPM format along with clinical data. To ensure comparability across different samples, all data were normalized for expression levels through log2(TPM + 1) transformation. During the data cleaning process, samples with normal or missing clinical information were excluded to ensure the accuracy of the analysis results.

Date of RNA-sequencing patient and bioinformatics analysis

The gene expression data (463 cases, Workflow Type: HTSeq-Counts) and corresponding clinical information were downloaded from TCGA official website for SKCM. The RNA-Seq gene expression level 3 HTSeq-Counts data of 463 patients with Skin Cutaneous Melanoma and clinic data were retained and further analyzed.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis

Survival analyses were conducted using R (v 4.2.1) with the survival (3.3.1) and rms (6.3-0) packages. The proportional hazards assumption was validated through Schoenfeld residual tests. univariate Cox proportional hazards regression was first applied to evaluate associations between individual variables and overall survival (OS), with variables meeting a predefined significance threshold (p < 0.05) subsequently included in a multivariate Cox model to assess independent prognostic effects. The rms package supported model diagnostics and visualization of survival curves. All analyses adhered to the assumptions of Cox regression, including independence of observations and time-invariant hazard ratios. This two-step approach—univariate screening followed by multivariate modeling—ensured rigorous identification of clinical predictors while maintaining compliance with proportional hazards requirements.

Single-gene differential expression analysis

Differential expression analysis of SIGLEC8 (ENSEMBL ID: ENSG00000105366.15) was performed using DESeq2 (v1.36.0) in R (v4.2.1) by stratifying 225 SKCM samples into low-expression (0–50th percentile, reference) and high-expression (50–100th percentile) groups based on normalized counts; a DESeqDataSet object was constructed from raw counts, followed by median-of-ratios normalization, shrinkage-based dispersion estimation, and differential testing via Wald test, with genes meeting |log₂(fold change)| >1 and Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value < 0.05 defined as significant differentially expressed genes. DESeq2 employs a generalized linear model with shrinkage estimators for dispersion and fold changes, improving robustness in datasets with moderate sample sizes and low-count genes; results were visualized through volcano plots and heatmaps adhering to RNA-seq best practices [12, 13]. The volcano plot was generated to visualize genome-wide differential expression: the x-axis shows log2(fold change) and the y-axis shows − log10(adjusted p-value). Thresholds for significance (|log2FC| = 1 and adjusted p = 0.05) are indicated by dashed vertical and horizontal lines, respectively.

Differential gene correlation analysis

Data analysis was performed using the R (v 4.2.1) and the ggplot2[3.4.4] package for data visualization. Pairwise correlations between variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, a nonparametric method suitable for measuring monotonic relationships between variables, which does not assume linearity or normality in the data distribution. The analytical process involved calculating Spearman correlation coefficients for all variable pairs, followed by visualizing the results using a heatmap. The heatmap was generated in ggplot2 to illustrate the strength and direction of correlations, with color gradients representing correlation values (e.g., warmer colors for positive correlations and cooler colors for negative correlations). This approach facilitated the interpretation of pairwise associations across the dataset, allowing for the identification of strong relationships or potential multicollinearity among variables.

Survival, time-dependent ROC and prognostic analysis

To evaluate the relationship between SIGLEC8 expression and patient survival prognosis, we conducted an analysis using R (v 4.2.1). The survival package [3.3.1] was employed to test the proportional hazards assumption and fit survival regression models. The results were visualized using the survminer package [0.4.9] and the ggplot2 package [3.4.4]. Cox regression was utilized to generate survival curves and analyze differences in Overall Survival (OS) between high and low expression groups. Prognostic data were supplemented from a 2018 Cell publication [14]. The significance of survival differences between the two groups was tested using the Log-rank test. Additionally, a Cox regression model was used to assess SIGLEC8 as an independent prognostic factor, performing both univariate and multivariate regression analyses to adjust for the influence of other potential confounding variables (such as age, pathological stage, tumor ulceration, lymph node metastasis, etc.) on survival outcomes. Data analysis was conducted using R (v 4.2.1), with the time ROC [0.4] package for survival analysis and ggplot2 [3.4.4] for data visualization. Prognostic data were supplemented from a 2018 Cell publication [14]. The time ROC package was then employed to perform survival-related analyses, and results were visualized using ggplot2 to generate informative plots for interpreting associations between variables and survival outcomes.

SIGLEC8 expression associated with clinical pathological characteristics (logistic regression)

Statistical analyses were performed using the stats package (4.2.1) in R (v4.2.1). To evaluate the association between SIGLEC8 expression and clinical-pathological characteristics, univariate logistic regression models were independently constructed for each variable. In these models, SIGLEC8 expression presumed as the outcome variable, dichotomous based on a predefined threshold) was regressed against individual clinical features (e.g., age, gender, pathological stage) as predictors.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG combine with logFC)

To investigate the potential biological functions of SIGLEC8 in cutaneous melanoma, we integrated fold change (FC) analysis with gene enrichment approaches. First, differential gene screening was performed by dividing the samples into high-expression and low-expression groups based on SIGLEC8 expression levels. The FC values for all genes between the two groups were calculated as the ratio of the mean expression in the high-expression group to that in the low-expression group (FC = mean of high-expression group mean of low-expression group). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were then identified by combining FC thresholds (e.g., FC ≥ 2) with statistical significance criteria (e.g., p-value < 0.05 or adjusted q-value). A list of DEGs was subsequently constructed. Next, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, encompassing biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF), along with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis, was conducted on the DEGs using appropriate bioinformatics tools. Enrichment significance was calculated to quantify the degree of gene enrichment within specific functional categories or pathways. Finally, the results were visualized to facilitate interpretation and presentation of the findings.

Immune infiltration analysis

Statistical analyses and data visualization were performed using R (v 4.2.1). The ggplot2 [3.4.4], stats [4.2.1], and car [3.1-0] packages were employed for data handling, statistical testing, and graphical representation. After grouping the primary variable, SIGLEC8, appropriate statistical tests were selected based on data distribution and format. Specifically, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied for non-parametric comparisons between groups. In cases where statistical assumptions were not met, analyses were not conducted. Immune infiltration analysis was carried out using the single-sample Gene Set Variation Analysis (ssGSEA) algorithm implemented in the GSVA package (v1.46.0) [15]. Gene signatures for 24 immune cell types were adopted from the Immunity study by Bindea et al. to estimate immune cell enrichment scores across TCGA-UCEC samples [16]. Of particular interest, the relationship between SIGLEC8 expression and activated dendritic cells (aDCs) was examined. To cross-validate ssGSEA results, we applied CIBERSORT to estimate the relative abundances of 22 immune cell types (LM22 signature) in the TCGA-SKCM samples. Input data were normalized transcriptome values in log2 (TPM + 1) format (the same normalization used for other analyses). The CIBERSORT R script (LM22 signature matrix) was run with 1000 permutations and default parameters. Only samples with CIBERSORT p < 0.05 were considered to have reliable deconvolution and were included in subsequent correlation analyses. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess the association between SIGLEC8 expression and each deconvoluted immune cell fraction; p-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, and adjusted p < 0.05 was considered significant [17].

Pan-cancer prognostic comparison of SIGLEC8

Pan-cancer comparative analysis was performed by systematically reviewing literature from PubMed and GEO datasets (2000–2024). Key findings were synthesized in Table S1 following PRISMA-ScR guidelines.

Hematopoietic cell lineage pathway analysis

To explore the biological pathways associated with SIGLEC8-related differential gene expression, we performed pathway enrichment analysis using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified based on predefined thresholds for fold change and statistical significance, and were subsequently input into KEGG enrichment analysis to identify significantly enriched pathways. Particular attention was given to the Hematopoietic Cell Lineage pathway to investigate its potential role in immune regulation and lineage-specific differentiation. Enrichment was considered statistically significant at an adjusted p value < 0.05.

Statistical analysis and methods-immunotherapy biomarker correlations

All statistical analyses of the data were performed using R (v 4.2.1). In all statistical tests, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. When comparing differences between groups, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Mann-Whitney U test were utilized. The Cox regression model was employed to evaluate the relationship between SIGLEC8 expression and clinical characteristics, and to calculate hazard ratios (HR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) to assess its independent role in survival prognosis. Spearman correlation analyses between SIGLEC8 expression and established immunotherapy biomarkers (PD-L1/CD274, tumor mutational burden [TMB], and IFN-γ [IFNG]) were conducted in the TCGA-SKCM cohort.

Result

Patient characteristics

As shown in Table 1 and 463 cases with both clinical and gene expression data were downloaded from TCGA data. The age distribution (≤ 60 years) accounted for 54.5% and > 60 years for 45.5%. The cohort was predominantly male (61.9%), with females comprising 38.1%. Racial composition showed 97.2% White, 2.6% Asian and 0.2% Black or African American. Weight (> 70 kg) in 70.4% and height (> 170 cm) in 46.3%. BMI distribution (≤ 25) was found in 84 patients (31.1%), BMI distribution (> 25) was found in 186 patients (68.9%). Our study cohort, the pathologic staging T stage of SKCM included T1 (11.5%), T2 (21.6%), T3 (24.9%) and T4 (41.9%). The pathologic N stage of SKCM included Lymph node-negative (N0) in 57.3%, with nodal metastases N1 (17.9%), N2 (11.9%), and N3 (13.6%), the pathologic M stage of SKCM included distant metastasis-free (M0) in 94.4% versus metastatic (M1) in 5.6%, the pathologic stage of SKCM included Stage I (18.6%), Stage II (33.4%), Stage III (40.8%) and Stage IV (5.7%).The Melanoma Clark level included level I (1.4%), II (4.2%), III (18.2%), IV (39.3%) and V (12.4%). Extremities (42.8%) and trunk (37.1%) were primary locations, while head/neck accounted for 8.2%; 51.4% lacked site-specific documentation; Breslow depth (≤ 3 mm) was found in 186 patients (51.5%), Breslow depth (> 3 mm) was found in 175 patients (48.5%). Ulceration was found in 166 patients (53.0%), Breslow depth (absent) was found in 147 patients (47.0%). Received by Radiation therapy included 17.4%, untreated included 82.6%. In Overall survival (OS) events, alive was 53.2% and dead was 46.8%; Disease-specific survival (DSS) events occurred in 41.7%; Progression events observed in 67.0%, with 33.0% remaining progression-free. Of the initial 463 SKCM cases, 38 samples (8.2%) were excluded due to missing or incomplete clinical information (stage, ulceration status, or survival data). The excluded group had a mean age of 58.7 ± 12.3 years compared to 59.4 ± 13.1 years in the included cohort (p = 0.68) and a male female ratio of 1.5:1 versus 1.6:1 (p = 0.82), indicating no significant demographic differences. These exclusions were unlikely to introduce substantial bias in our prognostic analyses.

Table 1.

TCGA melanoma patient characterristics

| Clinical characteristics | Total (463) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <= 60 | 253 | 54.5 |

| > 60 | 211 | 45.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 292 | 61.9 |

| Female | 180 | 38.1 |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 12 | 2.6 |

| Black or African American | 1 | 0.2 |

| White | 450 | 97.2 |

| Weight | ||

| <= 70 | 77 | 29.6 |

| > 70 | 183 | 70.4 |

| Height | ||

| <= 170 | 137 | 53.7 |

| > 170 | 118 | 46.3 |

| BMI | ||

| <= 25 | 84 | 31.1 |

| > 25 | 186 | 68.9 |

| Pathologic T stage | ||

| T1 | 42 | 11.5 |

| T2 | 79 | 21.6 |

| T3 | 91 | 24.9 |

| T4 | 153 | 41.9 |

| Pathologic N stage | ||

| N0 | 236 | 57.3 |

| N1 | 74 | 17.9 |

| N2 | 49 | 11.9 |

| N3 | 56 | 13.6 |

| Pathologic M stage | ||

| M0 | 419 | 94.4 |

| M1 | 25 | 5.6 |

| Pathologic stage | ||

| Stage I | 78 | 18.6 |

| Stage II | 140 | 33.4 |

| Stage III | 171 | 40.8 |

| Stage IV | 24 | 5.7 |

| Melanoma Clark level | ||

| I | 6 | 1.4 |

| II | 18 | 4.2 |

| III | 78 | 18.2 |

| IV | 168 | 39.3 |

| V | 53 | 12.4 |

| Tumor tissue site | ||

| Head and Neck | 38 | 5.1 |

| Trunk | 172 | 23.0 |

| Extremities | 198 | 26.5 |

| Other | 13 | 1.7 |

| No | 385 | 51.4 |

| Breslow depth | ||

| <= 3 | 186 | 51.5 |

| > 3 | 175 | 48.5 |

| Melanoma ulceration | ||

| Yes | 166 | 53.0 |

| No | 147 | 47.0 |

| Radiation therapy | ||

| Yes | 81 | 17.4 |

| No | 385 | 82.6 |

| OS event | ||

| Alive | 248 | 53.2 |

| Dead | 218 | 46.8 |

| DSS event | ||

| Yes | 192 | 41.7 |

| No | 268 | 58.3 |

| PFI event | ||

| Yes | 312 | 67.0 |

| No | 154 | 33.0 |

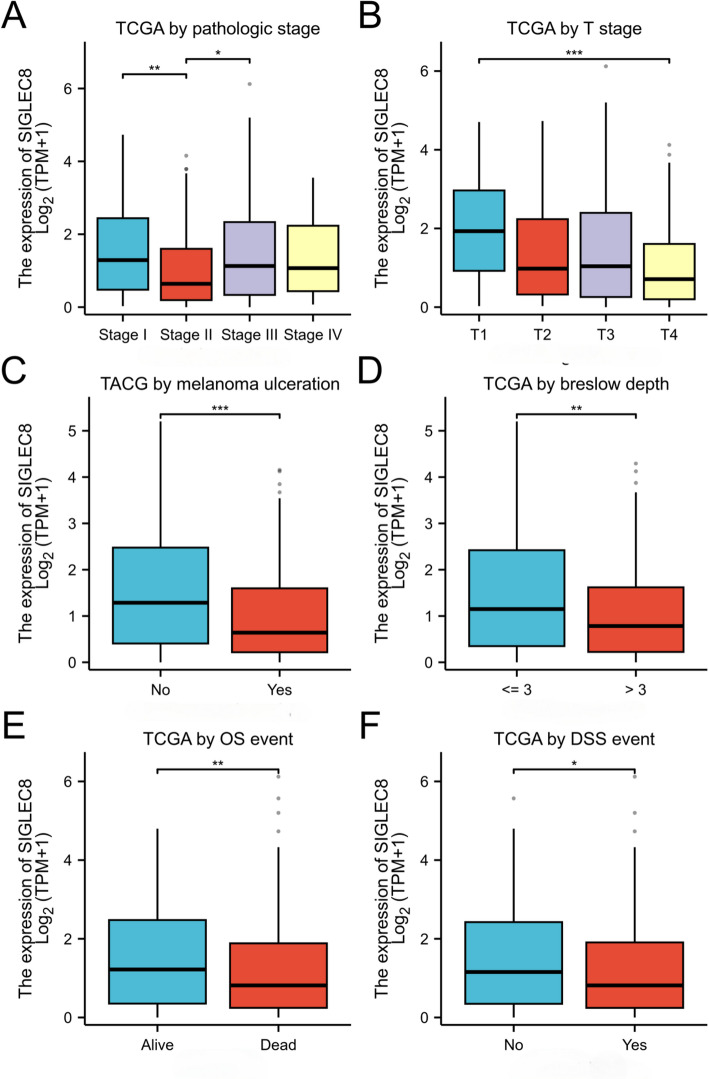

Association with SIGLEC8 expression and clinicopathologic variables

A total of 225 SKCM samples with SIGLEC8 expression data across all patient characteristics were analyzed from TCGA. As shown in Fig. 1A–F, SIGLEC8 expression was significantly decreased in Stage II tumors compared to Stage I and also downregulated in Stage II compared to Stage III, Compared with pathologic T stage T1, gene expression was downregulated in T4 (p = 0.0001 < 0.001). Compared with non-ulcerated melanoma, gene expression was downregulated in ulcerated melanoma (p = 0.0003 < 0.001). Compared with Breslow depth ≤ 3, gene expression was downregulated in Breslow depth > 3 (p = 0.0062 < 0.01). Compared with alive patients, gene expression was downregulated in deceased patients (p = 0.0036 < 0.01). Compared with patients without DSS events, gene expression was downregulated in those with DSS events (p = 0.0152 < 0.1).

Fig. 1.

Differential expression of SIGLEC8 in SKCM clinicopathologic subgroups. A, Comparison of SIGLEC8 expression across pathologic stages; B, comparison across pathologic T stages; C, comparison based on ulceration status; D, comparison by breslow depth; E, comparison between alive and deceased patients; F, comparison between patients with and without disease-specific survival (DSS) events. Statistical significance is indicated (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

Univariate analysis using logistic regression revealed that SIGLEC8 expression as a categorical dependent variable was associated with poor prognostic clinicopathologic characteristics (Table 2). Reduced SIGLEC8 expression in SKCM as significantly associated with Weight (p = 0.014, OR = 2.0 for > 70), Pathologic T stage (p < 0.001, OR = 0.251 for T4), Pathologic stage (p = 0.001, OR = 0.392 for Stage Ⅱ), Melanoma Clark level (p = 0.016,OR = 0.558 for Ⅳ & Ⅴ), Breslow depth (p = 0.009, OR = 0.575 for > 3), Melanoma ulceration (p < 0.001, OR = 0.449 for Yes). Compared with Weight ( < = 70), Pathologic T stage (T1), Pathologic stage (Stage l), Melanoma Clark level (I&II&III), Breslow depth ( < = 3), Melanoma ulceration (No). These results suggested that SKCMs with low SIGLEC8 expression are prone to progress to a more advanced stage and distant metastasis than those with high SIGLEC8 expression.

Table 2.

SIGLEC8 expression associated with clinical pathological characteristics (logistic regression)

| Characteristics | Total (N) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (> 60 vs. <= 60) | 464 | 0.949 (0.584–1.315) | 0.78 |

| Gender (Male vs. Female) | 472 | 0.898 (0.526–1.269) | 0.57 |

| Race (White vs. Asian) | 461 | 3.068 (1.748–4.387) | 0.096 |

| Weight (> 70 vs. <= 70) | 259 | 2.005 (1.451–2.560) | 0.014 |

| Height ( > = 170 vs. < 170) | 254 | 1.032 (0.536–1.529) | 0.9 |

| BMI (> 25 vs. <= 25) | 251 | 1.572 (1.035–2.109) | 0.099 |

| Pathologic T stage (T4 vs. T1) | 195 | 0.251 (-0.493–0.995) | < 0.001 |

| Pathologic N stage (N1&N2&N3 vs. N0) | 415 | 1.113 (0.724–1.501) | 0.59 |

| Pathologic M stage (M1 vs. M0) | 444 | 1.110 (0.302–1.917) | 0.801 |

| Pathologic stage (Stage II vs. Stage I) | 218 | 0.392 (-0.177–0.962) | 0.001 |

| Melanoma Clark level (IV&V vs. I&II&III) | 323 | 0.558 (0.082–1.033) | 0.016 |

| Tumor tissue site (Trunk vs. Extremities) | 369 | 1.097 (0.688–1.506) | 0.658 |

| Breslow depth (> 3 vs. <= 3) | 361 | 0.575 (0.157–0.992) | 0.009 |

| Melanoma ulceration (Yes vs. No) | 315 | 0.449 (-0.003–0.901) | < 0.001 |

| Radiation therapy (Yes vs. No) | 465 | 1.385 (0.902–1.868) | 0.187 |

Associations with overall survival and clinicopathologic characteristics

A total of 225 SKCM samples with corresponding clinicopathologic characteristics were analyzed to explore associations with overall survival using Cox regression analysis. As shown in Table 3, univariate analysis revealed that several variables were significantly associated with overall survival. Notably, Tumor tissue site Other had better survival compared to Extremities (HR = 2.113, 95% CI: 1.097–4.067) and patients age more than 60 years had better survival compared to those ≤ 60 years (HR = 1.663, 95% CI: 1.256–2.201) A higher pathologic T stage was associated with worse survival outcomes, with T3 patients showing a markedly increased risk compared to T1 (HR = 2.135, 95% CI: (1.179–3.867)) and with T4 patients showing a markedly increased risk compared to T1 (HR = 3.780, 95% CI: 1.692–8.443). Similarly, advanced pathologic N and M stage were also linked to poorer survival, with N1 vs. N0 showing a significant hazard ratio (HR = 1.503, 95% CI: 1.018–2.220), with N3 vs. N0 showing a significant hazard ratio (HR = 2.744, 95% CI: 1.177–6.402) and with M1 vs. M0 showing a significant hazard ratio (HR = 1.902, 95% CI: 1.032–3.506).Furthermore, increased Breslow depth was strongly associated with reduced survival, with patients having depth > 3 mm facing higher risk compared to those with ≤ 3 mm (HR = 2.665, 95% CI: 1.084–6.548, p = 0.033). Melanoma ulceration was also significantly associated with worse prognosis (HR = 2.099, 95% CI: 1.506–2.927, p < 0.001). In multivariate Cox analysis following variable selection, pathologic T stage (T4 vs. T1, HR = 2.994, 95% CI: 1.094–8.192) and pathologic N stage (N1 vs. N0, HR = 1.619, 95% CI: 1.007–2.603; N2 vs. N0, HR = 2.424, 95% CI: 1.349–4.358; N3 vs. N0, HR = 3.952, 95% CI: 2.201–7.097) remained independent prognostic factors. We tested the proportional hazards (PH) assumption for all variables in the Cox regression analyses using Schoenfeld residuals (cox.zph function, survival R package). In both univariate and multivariate models, all variables met the PH assumption (all p > 0.05). The global PH test for the multivariate model was also non-significant (χ² = 5.05, df = 12, p = 0.282), indicating that the hazard ratios for these covariates were constant over time. The PH test results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Associations with overall survival and clinicopathologic characteristics in TCGA patients using Cox regression, and results of proportional hazards (PH) assumption testing

| Characteristics | Total (N) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | PH test p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | PH test p-value | ||

| Gender | Male vs Female | 1.180 (0.885–1.574) | 0.261 | 0.695 | – | – | 0.695 |

| Weight | > 70 vs < = 70 | 0.649 (0.389–1.083) | 0.098 | 0.769 | – | – | 0.769 |

| Height | >= 170 vs < 170 | 0.855 (0.556–1.316) | 0.477 | 0.161 | – | – | 0.161 |

| BMI | > 25 vs < = 25 | 0.827 (0.513–1.333) | 0.436 | 0.346 | – | – | 0.346 |

| Tumor tissue site | Trunk vs Extremities | 0.945 (0.697–1.283) | 0.719 | 0.068 | – | – | 0.068 |

| Head and Neck vs Extremities | 1.276 (0.760–2.143) | 0.357 | – | – | |||

| Other vs Extremities | 2.113 (1.097–4.067) | 0.025 | – | – | |||

| Radiation therapy | Yes vs No | 0.980 (0.696–1.381) | 0.909 | 0.055 | – | – | 0.055 |

| Age | > 60 vs < = 60 | 1.663 (1.256–2.201) | < 0.001 | 0.854 | 1.088 (0.751–1.576) | 0.654 | 0.854 |

| Pathologic T stage | T2 vs T1 | 1.523 (0.826–2.806) | 0.178 | 0.695 | 2.079 (0.933–4.630) | 0.073 | 0.695 |

| T3 vs T1 | 2.135 (1.179–3.867) | 0.012 | 1.704 (0.745–3.897) | 0.207 | |||

| T4 vs T1 | 3.780 (2.109–6.776) | < 0.001 | 2.994 (1.094–8.192) | 0.033 | |||

| Pathologic N stage | N1 vs N0 | 1.503 (1.018–2.220) | 0.04 | 0.769 | 1.619 (1.007–2.603) | 0.047 | 0.769 |

| N2 vs N0 | 1.540 (0.977–2.429) | 0.063 | 2.424 (1.349–4.358) | 0.003 | |||

| N3 vs N0 | 2.744 (1.777–4.236) | < 0.001 | 3.952 (2.201–7.097) | < 0.001 | |||

| Pathologic M stage | M1 vs M0 | 1.902 (1.032–3.506) | 0.039 | 0.161 | 1.362 (0.521–3.560) | 0.528 | 0.161 |

| Breslow depth | > 3 vs < = 3 | 2.665 (1.948–3.644) | < 0.001 | 0.346 | 1.333 (0.688–2.584) | 0.394 | 0.346 |

| Melanoma ulceration | Yes vs No | 2.099 (1.506–2.927) | < 0.001 | 0.591 | 1.316 (0.883–1.963) | 0.178 | 0.591 |

| Global PH test | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.282 |

SIGLEC8-differential analysis

A total of 225 SKCM samples were analyzed to identify genes differentially expressed in association with SIGLEC8 expression. As shown in Table 4; Fig. 2, differential expression analysis revealed a panel of genes significantly correlated with SIGLEC8 expression. In the groups with high and low SIGLEC8 expression, we presented 20 up - regulated and 20 down - regulated differentially expressed genes. Notably, SIGLEC8 itself showed significantly elevated expression (log2FC = 4.2907, p = 2.91E-245), confirming the robustness of the grouping. Conversely, a subset of genes were markedly downregulated in the SIGLEC8 high-expression group, including OTOR, WFDC12, HTN3, and LCE3C (all the p < 0.001).

Table 4.

SIGLEC8-Differential analysis by DESeq2 (high VS low)

| gene_name | log2FoldChange | p-value | gene_name | log2FoldChange | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGLV1-41 | 4.346 | 1.49E-49 | OTOR | − 5.3065 | 1.94E-15 |

| SIGLEC8 | 4.2907 | 2.91E-245 | WFDC12 | − 5.0755 | 6.59E-23 |

| FCER2 | 4.2849 | 2.8E-72 | HTN3 | − 4.2661 | 1.17E-16 |

| IGHV7-4-1 | 4.2757 | 2.31E-38 | LCE3C | − 4.0756 | 0.000000927 |

| IGLV4-60 | 4.2117 | 4.09E-48 | SMR3B | − 3.9012 | 0.0000632 |

| AL139020.1 | 4.1793 | 1.58E-39 | KPRP | − 3.7121 | 1.14E-13 |

| IGKV1-13 | 4.1202 | 2.49E-36 | LCE2C | − 3.7035 | 0.00000246 |

| IGKV6-21 | 4.1169 | 1.02E-45 | RNASE7 | − 3.5523 | 4.67E-40 |

| IGHV3-64 | 4.0869 | 5.5E-52 | SPRR2G | − 3.5274 | 1.8E-11 |

| IGKV2-24 | 3.9949 | 2.54E-52 | AC073143.1 | − 3.441 | 0.0000451 |

| IGHV3-13 | 3.9905 | 4.48E-55 | LCE2D | − 3.3299 | 0.0000649 |

| CR2 | 3.9823 | 4.11E-40 | LINC01029 | − 3.2988 | 0.000000013 |

| PLA2G2D | 3.9491 | 8.69E-84 | DSC1 | − 3.1231 | 1E-15 |

| IGKV2-30 | 3.8816 | 2.12E-53 | PRB4 | − 3.0578 | 7.94E-09 |

| TCL1A | 3.8806 | 5.82E-62 | LCE1F | − 2.9935 | 0.000000908 |

| AL161781.2 | 3.8725 | 6.16E-24 | LCE3D | − 2.9861 | 0.000000219 |

| CXCR5 | 3.8301 | 4.56E-55 | KRT75 | − 2.9609 | 1.25E-10 |

| MS4A1 | 3.826 | 1.57E-57 | RBMY2QP | − 2.9541 | 0.000055 |

| CYP11B1 | 3.8237 | 4.94E-18 | LCE1C | − 2.9092 | 3.75E-08 |

| IGKV2D-30 | 3.8173 | 2.67E-35 | LCE6A | − 2.896 | 0.0003 |

Fig. 2.

Volcano plot of differential gene expression between SIGLEC8 high and low expression groups. The x-axis represents log2 fold change (high vs. low SIGLEC8) and the y-axis represents − log10(Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value). Each point corresponds to one gene. Red points indicate significantly up-regulated genes in the SIGLEC8 high group (|log2FC| ≥ 1, adjusted p < 0.05). Purple points indicate significantly down-regulated genes (|log2FC| ≥ 1, adjusted p < 0.05). Grey points indicate genes that did not meet significance thresholds. Vertical dashed lines denote ± 1 log2 fold change (i.e., 2-fold up/down), and the horizontal dashed line denotes adjusted p = 0.05 (− log10(0.05) ≈ 1.301). The top 20 up- and top 20 down-regulated genes are listed in Table 4

Univariate and multivariate analysis of high vs. low expression of SIGLEC8

A total of 225 SKCM samples with SIGLEC8 expression data across all patient characteristics were analyzed from TCGA. As shown in Table 5, survival analysis revealed that higher SIGLEC8 expression was significantly associated with improved overall survival. In both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, high SIGLEC8 expression was identified as a protective factor. Specifically, in univariate analysis, patients with high SIGLEC8 expression showed a significantly lower risk of death compared to those with low expression (HR = 0.594, 95% CI: 0.453–0.780, p < 0.001). This finding remained consistent in multivariate analysis after adjusting for other prognostic variables (HR = 0.594, 95% CI: 0.453–0.780, p < 0.001). These results suggest that SIGLEC8 may serve as an independent favorable prognostic biomarker in SKCM.

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of SIGLEC8 expression and overall survival

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR(95% CI) | p value | HR(95% CI) | p value | |

| SIGLEC8 (High vs Low) | 0.594 (0.453–0.780) | < 0.001 | 0.594 (0.453–0.780) | < 0.001 |

Survival and prognostic analysis

A total of 225 SKCM samples with complete SIGLEC8 expression profiles and clinicopathologic data were analyzed using TCGA datasets. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that low SIGLEC8 expression was significantly linked to poor prognosis in relation to several tumor-specific clinical parameters (Fig. 3A–I). A, Time-dependent ROC curve evaluating the predictive accuracy of SIGLEC8 expression for 1-year survival in SKCM patients. The area under the curve (AUC) is 0.339, suggesting limited prognostic utility. B, Kaplan–Meier overall survival (OS) analysis based on SIGLEC8 expression levels (high vs. low). Lower SIGLEC8 expression is associated with significantly poorer survival (HR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.45–0.78, p < 0.001). C, Subgroup survival analysis for patients with pathologic M0 stage. High SIGLEC8 expression correlates with better survival outcomes (HR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.40–0.71, p < 0.001). D, Survival comparison in patients who did not receive radiation therapy. Higher SIGLEC8 expression is associated with improved survival (HR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.41–0.75, P < 0.001). E-F, Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with pathologic N stage N2 (E) and N3 (F), respectively. High SIGLEC8 expression confers a survival advantage in both subgroups (N2: HR = 0.37, p = 0.025; N3: HR = 0.42, p = 0.029). G-H, Survival analysis in pathologic stage II (G) and stage III (H). Elevated SIGLEC8 expression is significantly linked to improved survival in both stages (Stage II: HR = 0.40, p < 0.001; Stage III: HR = 0.45, p < 0.001).I, Patients with T4 tumors exhibit better survival with higher SIGLEC8 expression (HR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.35–0.93, p = 0.026).These findings suggest that elevated SIGLEC8 expression is broadly associated with favorable survival across various clinical subgroups of SKCM patients. Further survival curves comparing overall survival between high and low SIGLEC8 expression groups stratified by clinical and demographic characteristics (Fig. 4A–I). Red curves represent the high SIGLEC8 expression group, and blue curves represent the low expression group. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and log-rank p-values are shown for each subgroup. A, Age > 60: High SIGLEC8 expression is associated with better survival (HR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.38–0.86, p = 0.007). B, Age ≤ 60: Elevated SIGLEC8 correlates with improved survival (HR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.43–0.89, p = 0.011). C, Height < 170 cm: High expression shows favorable prognosis (HR = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.21–0.82, p = 0.011). D, Gender (Male): Increased SIGLEC8 levels predict improved survival (HR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.48–0.93, p = 0.018). E, Gender (Female): High SIGLEC8 is associated with longer survival (HR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.36–0.92, p = 0.022). F, Weight ≤ 70 kg: Survival advantage observed in high expression group (HR = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.06–0.55, p = 0.003). G, Weight > 70 kg: High SIGLEC8 linked to better prognosis (HR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.31–0.83, P = 0.007). H, BMI ≤ 25: Elevated expression predicts better survival (HR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.13–0.78, p = 0.012). I, BMI > 25: High SIGLEC8 expression associated with improved outcome (HR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.35–0.98, p = 0.042). Collectively, these findings indicate that higher SIGLEC8 expression is a consistent favorable prognostic factor across various clinical and demographic subgroups.

Fig. 3.

Differential gene correlation analysis heat map dependent on SIGLEC8. Each cell represents the pairwise correlation between two genes. Color gradient indicates correlation strength and direction (red indicates positive correlations, blue indicates negative correlations; color saturation corresponds to the absolute value of the correlation coefficient) (*p < 0.05)

Fig. 4.

Prognostic significance of SIGLEC8 expression in SKCM patients based on survival analysis and clinical subgroups. A Time-dependent ROC curve for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival prediction; B Kaplan–Meier survival curve for all patients stratified by SIGLEC8 expression; C survival analysis for pathologic M0 stage; D, M1 stage; E, N0 stage; F, N1–N3 stage; G, pathologic stage I–II; H, stage III–IV; I, T4 stage. Survival differences were assessed using log-rank test and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown (All the p – values < 0.05). Blue indicates low SIGLEC8 expression, and red indicates high expression

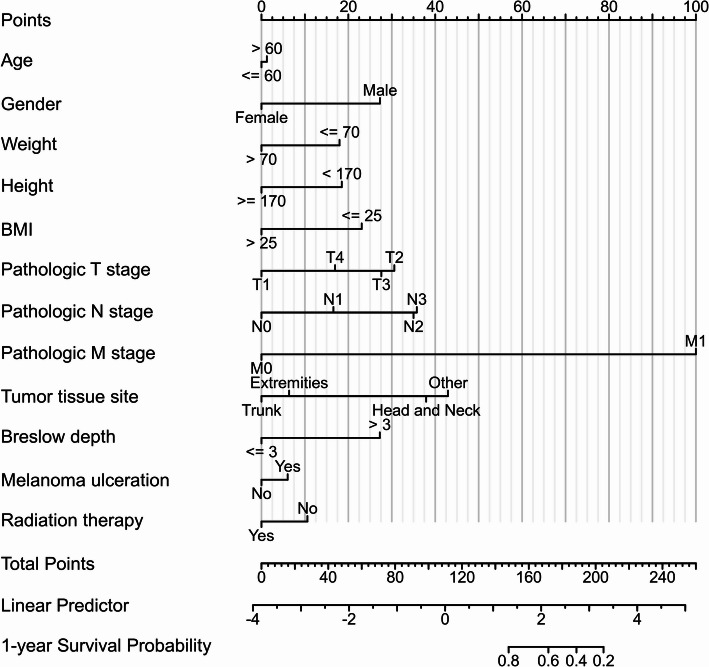

Prognostic line chart analysis

To further assess prognostic value, a nomogram (Fig. 5) was constructed to estimate the 1-year survival probability of patients with skin cutaneous melanoma. Variables included are Age (> 60 vs. ≤60), Gender (Male vs. Female), Weight (≤ 70 vs. >70), Height (< 170 vs. ≥170), BMI (≤ 25 vs. >25), Pathologic T stage (T1, T2, T3, T4), Pathologic N stage (N0, N1, N2, N3), Pathologic M stage (M0 vs. M1), Tumor tissue site (Extremities, Trunk, Head and Neck, Other), Breslow depth (≤ 3 vs. >3), Melanoma ulceration (Yes vs. No), and Radiation therapy (Yes vs. No). Each variable corresponds to a specific number of points, which are summed to generate a Total Points score. This score is then mapped to a Linear Predictor and ultimately used to estimate the 1-year Survival Probability. The nomogram provides a comprehensive and visual tool for clinicians to assess individual patient prognosis by combining multiple clinical features into a quantitative prediction model.

Fig. 5.

Survival analysis of SIGLEC8 expression stratified by demographic and clinical factors. A Patients aged > 60; B patients aged ≤ 60; C patients with height ≥ 170 cm; D male patients; E female patients; F patients weighing ≤ 70 kg; G patients weighing > 70 kg; H patients with BMI ≤ 25; I patients with BMI > 25. Kaplan–Meier curves are shown with corresponding HR, 95% CI, and all the p-values < 0.05. Blue indicates low SIGLEC8 expression, and red indicates high expression

Pan-cancer comparison of SIGLEC8 prognostic effects

Systematic analysis of SIGLEC8’s prognostic significance across major cancer types revealed distinct tissue-specific patterns (summarized in Table S1). Adverse prognosis with high expression: In clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), elevated SIGLEC8 expression correlated with poor overall survival (OS) and promoted metastasis via HIF-1α signaling. Adverse prognosis with low expression: Gastric cancer (STAD) showed significantly worse OS with reduced SIGLEC8 levels, where it served as an independent surgical prognosticator. Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) exhibited poor survival outcomes associated with SIGLEC8 downregulation, correlating with immune evasion mechanisms. Variable prognostic associations: Breast cancer (BRCA) demonstrated subtype-dependent effects. Ovarian cancer (OV) prognostic value varied across risk models but was validated in independent GEO cohorts. Protective role in melanoma: In skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), high SIGLEC8 expression predicted improved prognosis (this study), showing significant associations with B-cell/T-cell pathway activity.

Differential gene correlation heatmap depend on SIGLEC8

In the presented gene correlation heat map (Fig. 6), a group of genes—including IGLV1-41, SIGLEC8, FCER2, IGHV7-4-1, IGLV4-60, AL139201.1, IGKV1-13, IGKV1-21, IGHV3-64, IGKV2-24, IGHV2-13, CR2, PLA2G2D, IGKV2-30, TCL1A, AL161781.2, CXCR5, MS4A1, CYP11B1, IGKV2D-30, FCRL1, IGLV6-61, AC109206.1, IGHV2-70, IGKV1-9, PAX5, IGHV3-21, FCRL4, IGKV7-3, and IGLV4-69—demonstrate statistically significant positive correlations (indicated by star-marked red squares) with one another. Conversely, these same genes exhibit significant negative correlations (marked in blue with asterisks) with another distinct gene cluster, including OTOR, WFDC12, KPRP, LEC2C, RNASE7, AC073143.1, LCE2D, LINC01029, LCE1F, LCE3D, KRT75, RBMY2QP, LCE1C, and LCE6A (*p < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Nomogram predicting 1-year survival probability in SKCM patients. The nomogram integrates clinical variables (e.g. age, gender, weight, height, BMI, pathologic stage, tumor site, Breslow depth, ulceration status, radiation therapy) to estimate 1-year survival. Each variable contributes to a point score which maps to a linear predictor and final survival probability

Gene set enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG combine with logFC)

Further integrative analysis of gene expression profiles, as illustrated in Fig. 7A–D, revealed significant enrichment of genes involved in key biological processes, notably epidermal cell differentiation, keratinization, and immunoglobulin-related immune responses. As shown in Fig. 6A, BP includes epidermal cell differentiation, keratinocyte differentiation, keratinization, etc. (all Padj ≈ 0, Counts ≈ 12). CC involves pathways such as immunoglobulin complex (Padj ≈ 0, Counts ≈ 12.), immunoglobulin complex, circulating (Padj ≈ 0, Counts ≈ 6) and cornified envelope (Padj ≈ 0, Counts ≈ 6). MF contains pathways like antigen binding (Padj ≈ 0, Counts ≈ 6.), immunoglobulin receptor binding (Padj ≈ 0, Counts ≈ 6), and endopeptidase inhibitor activity (Padj ≈ 0.015, Counts ≈ 5). KEGG shows the Hematopoietic cell lineage pathway (Padj ≈ 0.015, Counts ≈ 3). Dots of different colors represent different Padj (corrected p-values), reflecting the significance of the enrichment results. The closer the color is to red, the smaller the Padj value, and the more significant the enrichment. The size of the dots corresponds to the Counts value, that is, the number of genes in the pathway. The larger the Counts value, the bigger the dot. In Fig. 6B, Network analysis of enriched Gene Ontology terms and associated genes based on SIGLEC8 expression in SKCM samples. The Molecular Function term GO:0003823 (antigen binding) exhibits the strongest correlation, with the gene IGHV7-4-1, IGHV3–64, IGHV3–13, IGHV2–30, IGHV2–70, IGHV3–21, demonstrating significant upregulation (log fold change ≈ 2.0) and in Fig. 6C, Distribution analysis of enriched Gene Ontology terms with log fold change and Z-scores related to SIGLEC8 expression in SKCM samples. The Cellular Component term GO:0019814 (immunoglobulin complex) displays the highest enrichment, with a Z-score of approximately 4.0(Blue circles indicate upregulated genes, while red circles indicate downregulated genes.)

Fig. 7.

Gene ontology (GO), KEGG combine with logFC analysis. A Dot plot of enriched GO terms (BP, CC, MF) and KEGG pathway, with dot size indicating gene count and color indicating adjusted p-value; B circular plot showing gene-to-GO term connections, colored by log₂ fold change; C circular plot of gene distribution across GO terms, colored by log₂ fold change (red for CC, blue for BP, grey for MF); D scatter plot showing GO term enrichment with Z-score and –log₁₀(P adj). (blue represents upregulated genes, red represents downregulated genes)

The relationship between SIGLEC8 and immune cell infiltration

As shown in Fig. 8A, SIGLEC8 expression exhibited significant positive correlations with the infiltration of various immune cell types, including T cells, cytotoxic cells, and activated dendritic cells (aDCs), based on Spearman correlation analysis. Notably, the correlation coefficient between SIGLEC8 and T cells was 0.767, between SIGLEC8 and Cytotoxic cells was 0.724, between SIGLEC8 and aDCs was 0.700 (***p < 0.001), indicating a strong association with T-cell, Cytotoxic cells and aDCs enrichment. Further analyses, as presented in Fig. 8B, a significant positive correlation between the expression level of SIGLEC8 and the enrichment score of aDCs. That is, as the expression level of SIGLEC8 increases, the enrichment score of aDCs also tends to increase. (Spearman R = 0.700, p < 0.001) and Fig. 8C illustrates the enrichment scores of aDCs (Enrichment score of aDCs) categorized by the expression levels of SIGLEC8 (two groups: Low and High). The data distribution is presented through box - and - whisker plots. It can be seen that the overall enrichment scores of aDCs in the High group are higher than those in the Low group. There is a significant difference between the two groups (marked as ***, which typically indicates p < 0.001). so confirmed a consistent positive relationship between SIGLEC8 expression and aDCs infiltration. These findings suggest that SIGLEC8 may contribute to shaping the tumor immune microenvironment by promoting immune cell recruitment, thereby potentially enhancing anti-tumor immune responses.To validate the immune-infiltration patterns inferred by ssGSEA, we performed CIBERSORT deconvolution (LM22) on the same TCGA-SKCM expression dataset (Fig. S1). Among samples meeting the CIBERSORT p < 0.05 reliability threshold, SIGLEC8 expression showed significant positive correlations with multiple T-cell subsets, mast-cell subsets, and NK-cell subsets (Spearman’s rank correlation, adjusted p < 0.05). These results are concordant with the ssGSEA findings (Fig. 7) and strengthen the evidence that SIGLEC8 expression is associated with increased adaptive and innate immune infiltration in SKCM.

Fig. 8.

Correlation between SIGLEC8 expression and immune cell infiltration. A Correlation between SIGLEC8 expression and infiltration of various immune cell types (e.g., T cells, NK cells and so on), with dot color representing p-value and size indicating correlation strength; B scatter plot of dendritic cell (aDC) enrichment scores versus SIGLEC8 expression with Spearman correlation coefficient; C box plot comparing aDC infiltration between high and low SIGLEC8 expression groups. (***p < 0.001)

Results-association of SIGLEC8 with immunotherapy biomarkers

Spearman analysis revealed significant positive correlations between SIGLEC8 and PD-L1 (R = 0.47, p = 2.0 × 10− 5), TMB (R = 0.55, p = 4.7 × 10− 7) and IFN-γ (R = 0.55, p = 5.1 × 10− 7) in the TCGA-SKCM cohort (Fig. 9A-C).

Fig. 9.

Spearman correlation analyses between SIGLEC8 expression and established immunotherapy biomarkers in TCGA-SKCM cohort. A Correlation between SIGLEC8 and PD-L1 (CD274) expression levels. B Correlation between SIGLEC8 and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ/IFNG) expression levels. C Correlation between SIGLEC8 and tumor mutational burden (TMB). Each scatter plot shows individual patient samples with correlation coefficient (r) and statistical significance (p-value) indicated. All correlations demonstrate statistically significant positive associations, suggesting potential relationships between SIGLEC8 expression and immunotherapy response biomarkers

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that SIGLEC8 expression is strongly correlated with prognosis in SKCM. High SIGLEC8 levels were associated with improved overall survival. This finding underscores the potential of SIGLEC8 as a prognostic biomarker. Our results build upon prior work showing that members of the Siglec family can modulate antitumor immunity [18, 19]. They also contribute to a growing body of literature that applies system-level analyses to explore the complexity of the tumor microenvironment (TME). For example, the IOBR framework integrates transcriptomic data and ligand–receptor interactions. This approach has been used to identify immune signatures that predict responses to immunotherapy across cancer types [8]. In a related area, dynamic network biomarker methods have been applied to thyroid carcinoma. These approaches help capture molecular transitions and shifts in immune landscapes [9]. In addition to these intrinsic tumor analyses, gut microbiome profiling has revealed important extrinsic influences. In melanoma patients treated with anti–PD-1 therapy, higher microbial diversity and enrichment of Ruminococcaceae taxa have been observed. These microbial features are linked to better responses to therapy, likely by enhancing T-cell activity [10, 11].

Regarding the 1-year ROC curve (Fig. 3A), the AUC value of 0.339 is notably below 0.5, indicating discrimination worse than random chance [20, 21]. Such a low value can arise from methodological factors—such as inverted outcome coding or suboptimal model specification—or reflect a true inverse association between the biomarker and the outcome [22]. In the latter scenario, the complementary value (1 − AUC = 0.661) may better represent the discriminative capacity, which in this case falls within the “fair-to-moderate” range [23]. However, this is still below the AUC ≥ 0.8 threshold generally considered necessary for strong standalone clinical utility [24].

These findings highlight several implications. First, the predictive capacity of SIGLEC8 alone is limited, and it should not be used as an independent clinical decision-making tool without further validation. Second, confidence intervals for the AUC and statistical testing against the null hypothesis (AUC = 0.5) should be included to rigorously evaluate the robustness of this finding. Third, combining SIGLEC8 expression with established prognostic markers (e.g., TNM stage, BRAF mutation status) or integrating it into multi-omics models may enhance predictive performance. Finally, validation in independent melanoma cohorts and prospective studies is essential to determine real-world clinical applicability [25].

We acknowledge recent reports on SIGLEC8’s immunomodulatory roles in other cancers and have expanded our analysis to contextualize the novelty of our findings. As systematically compared in Table S1, SIGLEC8 exhibits cancer-type-specific prognostic effects: First, our study reveals that elevated SIGLEC8 expression serves as a favorable prognostic marker in cutaneous melanoma—a finding that contrasts starkly with its established roles in other malignancies. Specifically, high SIGLEC8 predicts adverse outcomes in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) [26], low expression correlates with poor survival in gastric cancer [27], downregulation associates with aggressive phenotypes in lung adenocarcinoma [28], and variable impacts are observed in ovarian cancer models [29, 30]. This divergence underscores the tissue-specific functionality of SIGLEC8 within tumor microenvironments. Second, our work provides novel mechanistic insights beyond SIGLEC8’s canonical roles in eosinophil/mast cell biology [26, 27]. We demonstrate its specific involvement in B-cell lineage pathways (via strong co-expression with FCER2, CR2, and MS4A1) and CD8 + T-cell modulation within melanoma—representing the first evidence of SIGLEC8-hematopoietic crosstalk in skin cancer. Third, this study provides the most comprehensive evaluation of SIGLEC8 in melanoma to date, integrating clinical outcome analysis (OS/DSS/PFI), immune infiltration profiling (CIBERSORT), and pathway enrichment (ssGSEA) across 463 TCGA-SKCM patients. The systematic pan-cancer comparison in Table S1 highlights the unique protective role of SIGLEC8 in SKCM.

Mechanistically, we illustrate in Fig. 10 that SIGLEC8 may influence lymphoid lineage differentiation. This effect could occur through interactions with FCER2, CR2, and MS4A1. FCER2 (CD23) regulates IgE production and B-cell activation [31, 32]. CR2 (CD21) modulates complement-mediated B-cell responses [33]. MS4A1 encodes CD20, which is a well-known B-cell target [34]. CD8A and CD8B encode the CD8 co-receptor that is essential for cytotoxic T-cell function [35]. Moreover, SIGLEC8 is selectively expressed on eosinophils, mast cells, and basophils. It functions as an inhibitory receptor containing ITIM motifs. When engaged by sialylated ligands or antibodies, SIGLEC8 recruits SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatases. This recruitment triggers inhibitory signaling cascades, promotes apoptosis, or reduces cytokine release [18, 36]. In the TME, such mechanisms could suppress pro-tumorigenic mast cell activity. Paradoxically, they may also promote antitumor eosinophil infiltration [37]. These effects are consistent with our observation that patients with high SIGLEC8 expression had better survival outcomes [38–41].

Fig. 10.

The involvement of the SIGLEC8 gene in the ‘Hematopoietic Cell Lineage’ pathway within the pathophysiological context of SKCM. This is the part of ‘Hematopoietic Cell Lineage’ pathway from KEGG

SIGLEC8 recognizes glycans terminating in 6′-sulfo-sialyl Lewis^X and sialylated GalNAc structures, with the sialyl-Tn (STn) antigen being among the most studied ligands [42]. STn, generated through premature termination of O-glycosylation by ST6GalNAc-I, is frequently overexpressed in epithelial tumors and has been implicated in dampening antitumor immunity by engaging inhibitory Siglec receptors on immune cells [43]. Although comprehensive STn profiling in SKCM is lacking, glycoproteomic and glycan-microarray studies in melanoma cell lines and tissues have revealed aberrant sialylation signatures consistent with the presence of SIGLEC8-binding motifs [44, 45]. Such alterations may facilitate immune evasion by attenuating B-cell receptor signaling and modulating T-cell activation thresholds [46]. In our analysis, the strong co-expression of SIGLEC8 with B-cell–associated markers (FCER2, CR2, MS4A1) aligns with its reported enrichment in humoral immune compartments, while the correlation with T-cell–related pathways suggests potential cross-talk via antigen-presenting cells or cytokine networks [47]. Taken together, these findings support a model in which SIGLEC8 contributes to melanoma immune regulation through ligand-mediated engagement on specific immune subsets, ultimately influencing both B- and T-cell–driven responses. Further validation using independent datasets and single-cell resolution approaches will be critical to confirm this mechanism.

To place SIGLEC8 findings in context with established prognostic markers, we compared it with the BRAF V600E mutation. This mutation is present in approximately 40–60% of melanomas and is known to affect prognosis and therapy response [48, 49]. Unlike tumor mutational burden (TMB), which requires whole-exome sequencing, SIGLEC8 can be assessed using transcriptomic profiling or immunohistochemistry. This makes it a cost-effective alternative biomarker.

The significant correlations between SIGLEC8 and PD-L1, TMB, and IFN-γ suggest its role in immunotherapy-sensitive microenvironments. The association with TMB is particularly notable, as high TMB is a validated predictor of immune checkpoint inhibitor response.

Our analysis leveraged a large TCGA cohort but has several limitations. About 8% of samples were excluded due to missing data. However, demographic comparisons suggest that this exclusion introduced minimal selection bias. The TCGA cohort also consists mainly of individuals of European ancestry, which limits generalizability. Treatment metadata, such as immunotherapy usage, are incomplete. Additionally, melanoma histologic subtypes—including superficial spreading and nodular melanoma—might influence SIGLEC8’s role. Unfortunately, TCGA does not provide comprehensive subtype annotations [50]. This limitation precluded any subtype-specific analyses. Future studies should validate SIGLEC8 as a biomarker in diverse and well-annotated cohorts. They should also integrate detailed treatment information. Multi-omics deconvolution of the TME and microbiome sequencing will be needed to clarify how SIGLEC8 pathways interact with host–microbial crosstalk and immune regulation in melanoma.

Collectively, our data suggest a model in which SIGLEC8 acts as an important modulator within the immune microenvironment of SKCM. Elevated SIGLEC8 expression is linked to a favorable prognosis. This effect may occur through enhanced immune surveillance, mediated by FCER2, CR2, MS4A1, CD8A, and CD8B pathways that regulate B-cell and T-cell functions. These findings not only highlight the prognostic significance of SIGLEC8 but also provide mechanistic insight into its role in tumor–immune interactions.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the TCGA Research Network for making their data publicly accessible.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: [Na Lin], [Zhi Yang] Methodology: [Feng Li], [Na Lin] Formal Analysis: [Feng Li], [Na Lin]Investigation: [Feng Li], [Na Lin]Resources: [Feng Li], [Na Lin]Data Curation: [Feng Li]Writing – Original Draft: [Feng Li]Writing – Review & Editing: [Na Lin], [Zhi Yang], [Feng Li]Visualization: [Na Lin], [Feng Li] Supervision: [Zhi Yang] Funding Acquisition: [Zhi Yang]

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82371567): “Mechanism of YAP1-TEAD-mediated skin photoaging via transcriptional regulation of homologous recombination repair", the First-Class Discipline Team of Skin & Mucosal Regenerative Medicine of Kunming Medical University (2024XKTDTS10), and the “Xingdian Talent Support Program”.

Data availability

In this study, we downloaded and organized the RNA-seq data from the TCGA-SKCM project’s STAR pipeline from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) to ensure the reliability of the data.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This study utilized publicly available, de-identified data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Since no new human participants were recruited and no identifiable private information was accessed or generated, ethical approval for this specific retrospective analysis was not required. The original TCGA study protocols received approval from the relevant Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the original TCGA study. Given the exclusive use of de-identified, publicly available data from TCGA in this secondary analysis, obtaining new consent to participate was not required.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants during their enrollment in the original TCGA study. Given the exclusive use of de-identified, aggregated data in this analysis, separate consent for publication is not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhi Yang, Email: vipyz@126.com.

Na Lin, Email: ynlinna@163.com.

References

- 1.Eggermont AM, Spatz A, Robert C. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2014;383(9919):816–827. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karimkhani C, Green AC, Nijsten T, Weinstock MA, Dellavalle RP, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C. The global burden of melanoma: results from the global burden of disease study 2015. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(1):134–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiteman DC, Green AC, Olsen CM. The growing burden of invasive melanoma: projections of incidence rates and numbers of new cases in six susceptible populations through 2031. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(6):1161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tímár J, Ladányi A. Molecular pathology of skin melanoma: Epidemiology, differential Diagnostics, prognosis and therapy prediction. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10):5384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garbe C, Peris K, Hauschild A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - Update 2016. Eur J Cancer. 2016;63:201–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youngblood BA, Leung J, Falahati R, et al. Discovery, Function, and therapeutic targeting of Siglec-8. Cells. 2020;10(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang Y, Kong Y, Rong G, Luo Q, Liao W, Zeng D. Systematic investigation of tumor microenvironment and antitumor immunity with IOBR. Med Res. 2025;1:136–40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Zhang G, Xu P, Yu F, Li L, Huang R, Zhang P, Kadier K, Wang Y, Gu Q, Ding Y, Gu T, Chi H, Zhang S, Wu R, Xu Y, Zhu S, Zheng H, Zhao T, He Q, Qiu X. Optimized dynamic network biomarker Deciphers a High-Resolution heterogeneity within thyroid cancer molecular subtypes. Med Res. 2025;1:10–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye B, Fan J, Xue L, Zhuang Y, Luo P, Jiang A, Xie J, Li Q, Liang X, Tan J, Zhao S, Zhou W, Ren C, Lin H, Zhang P. iMLGAM: integrated machine learning and genetic Algorithm-driven multiomics analysis for pan-cancer immunotherapy response prediction. iMeta. 2025;4(2):e70011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, Reuben A, Andrews MC, Karpinets TV, Prieto PA, Vicente D, Hoffman K, Wei SC, Cogdill AP. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2018;359(6371):97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Lichtenberg T, Hoadley KA, et al. An Integrated TCGA Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource to Drive High-Quality Survival Outcome Analytics. Cell. 2018;173(2):400–e41611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hänzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39(4):782–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12(5):453–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duan S, Paulson JC. Siglecs as immune cell checkpoints in disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020;38:365–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murugesan G, Weigle B, Crocker PR. Siglec and anti-Siglec therapies. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2021;62:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models: A practical approach to development, validation, and updating. Springer; 2019.

- 21.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. Springer; 2015.

- 22.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. Wiley; 2013.

- 24.Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115(7):928–935. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, Sondak VK, Long GV, Ross MI, Lazar AJ, Faries MB, Kirkwood JM, McArthur GA, Haydu LE, Eggermont AM, Flaherty KT, Balch CM, Thompson JF. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American joint committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(6):472–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, et al. SIGLEC8 overexpression promotes CcRCC progression via HIF-1α signaling. Cancer Sci. 2023;114(5):2142–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, et al. First evidence for a role of Siglec-8 in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, et al. Decreased Siglec-8 predicts poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(9):10367–76. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu F, et al. SIGLEC family genes in tumor immunity. Front Oncol. 2020;10:586820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonome T, et al. Gene expression signature of aggressive serous ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(10):3185–94.18483387 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engeroff P, Vogel M. The role of CD23 in the regulation of allergic responses. Allergy. 2021;76(7):1981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engeroff P, Caviezel F, Mueller D, Thoms F, Bachmann MF, Vogel M. CD23 provides a noninflammatory pathway for IgE-allergen complexes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):301–e3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovács KG, Mácsik-Valent B, Matkó J, Bajtay Z, Erdei A. Revisiting the coreceptor function of complement receptor type 2 (CR2, CD21); coengagement with the B-Cell receptor inhibits the Activation, Proliferation, and antibody production of human B cells. Front Immunol. 2021;12:620427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pavlasova G, Mraz M. The regulation and function of CD20: an enigma of B-cell biology and targeted therapy. Haematologica. 2020;105(6):1494–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koh CH, Lee S, Kwak M, Kim BS, Chung Y. CD8 T-cell subsets: heterogeneity, functions, and therapeutic potential. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55(11):2287–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bochner BS. Siglecting the allergic response for therapeutic targeting. Glycobiology. 2016;26(6):546–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reinfeld BI, Madden MZ, Wolf MM, Chytil A, Bader JE, Patterson AR, Sugiura A, Cohen AS, Ali A, Do BT, Muir A, Lewis CA, Hongo RA, Young KL, Brown RE, Todd VM, Huffstater T, Abraham A, O’Neil RT, Wilson MH, Rathmell WK. Cell-programmed nutrient partitioning in the tumour microenvironment. Nature. 2021;593(7858):282–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He C. Research progress in the role of eosinophils in tumor immunotherapy. Chin J Cancer Biotherapy. 2023;30.2.

- 39.Shan-Shan Y, Feng-Hou G. Molecular mechanism of tumor cell immune escape mediated by CD24/Siglec-10, Front Immunol. 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Wei YQ, Lyu LH, Li M. Research progress on eosinophils in lung cancer. Chin J Prev Med. 2023;5711:1895–900. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Limei S, Alison M, Karthik S, Whitney T, W., Samuel K, L. Siglec15/TGF-β bispecific antibody mediates synergistic Anti-tumor response against 4T1 triple negative breast cancer in mice. Bioeng Transl Med. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.O’Sullivan JA, Carroll DJ, Bochner BS, von Gunten S. Siglecs as immunomodulatory targets in human disease. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2022;21(6):451–69. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Julien S, Videira PA, Delannoy P. Sialyl-Tn antigen: A cancer-associated carbohydrate antigen with a short but sweet history. Cancers. 2021;13(5):1146.33800182 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuster MM, Esko JD. The sweet and sour of cancer: glycans as novel therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(10):597–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodrigues E, Macauley MS, Reis CA. Targeting cancer glycosylation for cancer immunotherapy: exploiting the glyco-code. Front Oncol. 2020;10:394.32292720 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pillai S, Netravali IA, Cariappa A, Mattoo H. Siglecs and immune regulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2022;40:289–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghosh S, Hosseini R, Liao H, Quirke P. Immune cell glycosylation in the tumor microenvironment: implications for immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1154765. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 Blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161(7):1681–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

In this study, we downloaded and organized the RNA-seq data from the TCGA-SKCM project’s STAR pipeline from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) to ensure the reliability of the data.