Abstract

We used site-directed mutagenesis to probe the function of four alternating arginines located at amino acid positions 525, 527, 529, and 531 in a highly conserved region of domain III in the Cry1Ac toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis. We created 10 mutants: eight single mutants, with each arginine replaced by either glycine (G) or aspartic acid (D), and two double mutants (R525G/R527G and R529G/R531G). In lawn assays of the 10 mutants with a cultured Choristoneura fumiferana insect cell line (Cf1), replacement of a single arginine by either glycine or aspartic acid at position 525 or 529 decreased toxicity 4- to 12-fold relative to native Cry1Ac toxin, whereas replacement at position 527 or 531 decreased toxicity only 3-fold. The reduction in toxicity seen with double mutants was 8-fold for R525G/R527G and 25-fold for R529G/R531G. Five of the mutants (R525G, R525D, R527G, R529D, and R525G/R527G) were tested in bioassays with Plutella xylostella larvae and ion channel formation in planar lipid bilayers. In the bioassays, R525D, R529D, and R525G/R527G showed reduced toxicity. In planar lipid bilayers, the conductance and the selectivity of the mutants were similar to those of native Cry1Ac. Toxins with alteration at position 527 or 529 tended to remain in their subconducting states rather than the maximally conducting state. Our results suggest that the primary role of this conserved region is to maintain both the structural integrity of the native toxin and the full functionality of the formed membrane pore.

Bacillus thuringiensis is a gram-positive bacterium that produces one or more insecticidal crystal (Cry) proteins deposited in the form of an intracellular parasporal crystal during sporulation (20). Shortly after ingestion by a susceptible insect, most Cry proteins dissolve in the insect midgut, are activated by midgut proteases, and bind to a specific midgut epithelial cell receptor. After binding to specific docking proteins on the microvillous surface of susceptible epithelial cells in the larval midgut (12, 27), the toxin undergoes a conformational change in which the helix-rich domain I (DI) separates from the other two domains (23). A hairpin, composed of helices α4 and α5, subsequently inserts into the membrane with the other five helices spreading, in an umbrella-like fashion, over the membrane surface (8), with α4 lining the lumen of the pore to create a functional ion channel (19). The toxin-exposed midgut epithelial cells eventually die by a colloid-osmotic lysis mechanism (14).

The atomic structures of two activated Cry proteins, Cry1Aa and Cry3A, have been reported (11, 16). The two proteins have similar three-domain structures. DI is directly involved in ion channel formation (8, 23, 28). The second domain, DII, is involved in binding (9, 17, 21), whereas DIII is thought to play both a structural role and a toxin recognition role (2, 5, 15, 17).

A multiple sequence alignment of cry genes shows five conserved blocks (13), with the fourth conserved block (in DIII) consisting of an intriguing series of four alternating arginines in a conserved β17 strand. In an earlier study of this region in Cry1Aa (4), mutations of the second and third arginines in the series resulted in mutants that were either poorly expressed (second arginine) or not expressed at all (third arginine). The second arginine of Cry1Aa is involved in a complex network of hydrogen bonding to adjacent β-strands, whereas the third arginine is in a salt-bridge triad with two other residues in addition to hydrogen bonding to other residues. Thus, the results suggest that the second and third arginines are important for structural stability (11). Mutations in the first and fourth arginine resulted in mutant toxins with wild-type receptor binding affinities but slightly decreased toxicity to larvae of Bombyx mori, suggesting that a postbinding event was affected (4, 29). Voltage clamping of insect midguts and brush border membrane vesicle permeabilization studies as well as planar lipid bilayer studies of the two arginine mutants demonstrated a possible role in the ion channel function of the toxin (4, 24, 29).

We chose Cry1Ac as a target for mutagenesis in the present study because unlike Cry1Aa (17), Cry1Ac is extremely lethal to cultured Choristoneura fumiferana (Cf1) insect cells (10, 18). Therefore, toxicity levels can be determined even if mutant toxin production is severely inhibited. Further, because Cry1Ac and Cry1Aa have 76% identity between amino acids 29 and 630, we could use the known structure of Cry1Aa as a template to produce a structural model of Cry1Ac with the comparative protein modeling server, Swissmodel (http://www.expasy.ch/swissmod/SWISS-MODEL.html).

The objective of the present study was to elucidate the function of the four positively charged arginines in the conserved block 4 region of Cry1Ac at amino acid positions 525, 527, 529, and 531 in ion channel formation using planar lipid bilayers. Cultured insect cell lawn assays and larval bioassays were designed to determine if toxicity was severely affected in these mutants. To do this, we created eight single mutants and two double mutants of Cry1Ac with one or two arginines to either eliminate the positive charge (R-to-G replacement) or convert it to a negative charge (R-to-D replacement). Previous work with Cry1Aa examined only the first and last arginines, since mutations of the two middle arginines produced protoxins with altered solubility and proteolytic stability (4). The cultured insect cell lawn assay eliminates these problems by using only purified activated toxins, therefore bypassing in vivo solubilization and midgut protease activation. A subset of five mutants from those tested in the insect cell lawn bioassay were futher tested for toxicity in bioassays with Plutella xylostella larvae and for ion channel formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The double-stranded DNA plasmid pMP37 containing the Bacillus thuringiensis NRD-12 cry1Ac gene (GenBank accession no. U43606) (18) was used as a template for oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis using the Transformer mutagenesis kit from Clontech (Palo Alto, Calif.). Mutant clones were sequenced using an automated fluorescent sequencer from Applied Biosystems, model 370A. Oligonucleotides were synthesized using an Applied Biosystems oligonucleotide synthesizer, model 394/4.

Toxin activation and purification.

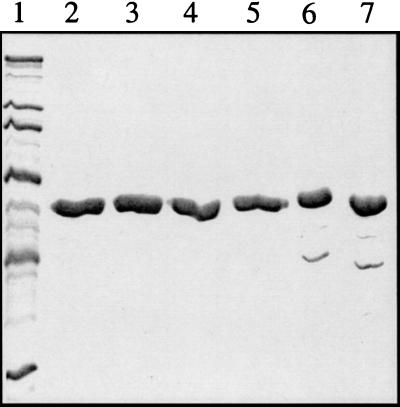

Purification of inclusion bodies expressed in Escherichia coli was done as previously described (18). Isolated inclusion bodies were solubilized and activated by incubating them at 28°C for 4 h in 0.04 M carbonate buffer, pH 10, with 1% trypsin (wt/vol), after which insoluble material was removed by centrifugation for 1 h at 200,000 × g. Activated toxins were purified by ion exchange fast-protein liquid chromatography by injecting the supernatant onto a Q-Sepharose column and subsequently eluting the bound toxin with a 0 to 500 mM NaCl gradient (18). A sample of the peak containing the purified toxin was stored at 4°C. For bilayer work, toxin stock solutions were prepared by resuspending water-precipitated toxin in 150 mM KCl buffered with 25 mM Tris-(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane (Tris) at pH 9.0 to approximately 0.8 to 1.5 mg/ml protein). Samples were also resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer to assess toxin integrity and purity on an acrylamide gel (Fig. 1). The concentration of purified toxins were determined by the method of Bradford (3) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

FIG. 1.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel of purified, trypsin-activated Cry toxins. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, Cry1Ac; lane 3, R525D; lane 4, R525G; lane 5, R527G; lane 6, R525G/R527G; lane 7, R529D. Approximately 2 μg of toxin was loaded per lane.

Insect cell lawn assays.

Cf1 cells from trypsinized larval tissue of C. fumiferana (spruce budworm) were cultured in Grace’s medium containing 0.25% tryptose and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were grown in spinner flasks at 28°C to a concentration of 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells/ml. In vitro toxicity assays were done on a lawn of agarose-suspended Cf1 cells (10). Activated toxins were diluted serially by half at each step, and 1 μl from each dilution was spotted onto a lawn of insect cells. After incubation at room temperature for 1 h, the plate was stained for 10 min with 20 ml of 0.2% (wt/vol) trypan blue in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (pH 10) and destained for 60 min in 0.1 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (pH 10) followed by several hours in 1.34% (wt/vol) KCl. We measured the threshold concentration, which is the lowest concentration of activated toxin in the dilution series producing a visible trypan blue-stained spot on the immobilized cell layer. The data represent the average toxicity value between three to nine replicates for each toxin examined.

Larval bioassays.

Larvae from the susceptible LAB-P strain of Plutella xylostella (diamondback moth) from Hawaii were used in leaf residue bioassays (25). Groups of 9 to 11 larvae ate cabbage leaf disks that had been dipped in distilled water dilutions of the protoxin form of each of five mutant Cry toxins. The concentration tested was 10 mg of protoxin per liter. In all tests, a surfactant (0.2% Triton AG98; Rohm and Haas) was added. Mortality was recorded after 5 days. Each test was replicated twice. The mean mortality of control larvae that ate leaf disks dipped in distilled water with surfactant only was 4% (range, 0 to 10%). Previous results in similar tests showed that 10 mg of native Cry1Ac protoxin per liter killed 94% of LAB-P larvae (26).

Planar lipid bilayers.

Planar lipid bilayers (22) were formed from a 7:2:1 lipid mixture (25-mg/ml final concentration in decane) of phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, and cholesterol (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, Ala.). The bilayer was painted, using disposable glass rods made from prepulled, sealed-tip Pasteur pipettes, across a 250-μm hole drilled in a Delrin cup (cis chamber) and pretreated with the above-described lipid mixture dissolved in chloroform. Membrane thinning was monitored by visual observation through a binocular dissection microscope and was assayed electrically. Typical membrane capacitance values ranged between 150 and 250 pF. Channel activity following addition of 5 to 10 μg (85 to 170 nM) of trypsin-activated toxin or its mutants/ml to the cis chamber was monitored by step changes in the current recorded while holding test voltages across the planar lipid bilayer. Toxin incorporation was helped by stirring the buffer in the cis chamber using a magnetic stir bar and by applying a holding voltage of −80 mV. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20 to 22°C) in buffer solutions containing either 150 or 450 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM Tris, pH 9.0. Single-channel currents were recorded with an Axopatch-1D patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, Calif.). The 5-kHz low-pass-filtered currents were pulse-code modulated (Instrutech Corp., Great Neck, N.Y.) and stored on VHF magnetic tape. For analysis, data were played back through an analog eight-pole, low-pass Bessel filter (Frequency Devices, Haverhill, Mass.) set at 600 Hz and digitized at a 2.5-kHz sampling frequency (Labmaster TL-125; Axon Instruments). Data analysis was performed on a personal computer using pClamp or Axotape software (Axon Instruments). For each applied voltage, current amplitudes were measured on the recorded traces.

Subconductance states were recognized as described previously (22) using the following criteria (6): (i) direct transitions from subconductance levels to main conductance levels were observed; (ii) subconductance states were never observed in the absence of the main conductance state; and (iii) the main conducting state did not result from the superposition of two or more independent channel openings. Conductance data are given as means ± standard errors of the means.

Applied voltages are defined with respect to the trans chamber, which was held at virtual ground. Positive currents (i.e., currents flowing through the planar lipid bilayer from the cis chamber to the trans chamber) are shown as upward deflections. The direction of current flow corresponds to positive charge movement.

RESULTS

Cry1Ac mutagenesis.

To assess the effect the alternating arginine region has on toxicity, individual arginines in Cry1Ac were replaced with a polar (glycine) or negatively charged (aspartic acid) amino acid (see Tables 1 and 2). In two clones, a pair of consecutive arginines was replaced with glycine to determine whether a greater decrease in the overall positive charge of this region would influence toxicity (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Bioassay of Cry1Ac arginine replacement mutants on P. xylostella larvae and cultured Cf1 cells

| Toxin | a.a. sequence (525–532)a | DNA sequence (bases 1573–1596)b | Threshold toxicity [ng/μl (SE)] | Relative toxicityc | % Mortality (SE)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cry1Ac | RYRVRVRY | aga tat cga gtt cgt gta cgg tat | 0.10 (0.03) | 1.00 | 94e |

| R525G | G | g-- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- | 0.54 (0.11) | 0.18 | 80 (10) |

| R525D | D | gac --- --- --- --- --- --- --- | 1.19 (0.40) | 0.08 | 70 (0) |

| R527G | G | --- --- g-- --- --- --- --- --- | 0.19 (0.10) | 0.53 | 100 (0) |

| R527D | D | --- --- gac --- --- --- --- --- | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.50 | NDf |

| R529G | G | --- --- --- --- g-- --- --- --- | 0.39 (0.07) | 0.26 | ND |

| R529D | D | --- --- --- --- gac --- --- --- | 0.57 (0.16) | 0.18 | 65 (5) |

| R531G | G | --- --- --- --- --- --- g-- --- | 0.14 (0.01) | 0.71 | ND |

| R531D | D | --- --- --- --- --- --- gac --- | 0.30 (0.01) | 0.33 | ND |

| R525G/R527G | G G | g-- --- g-- --- --- --- --- --- | 0.78 (0.16) | 0.13 | 45 (5) |

| R529G/R531G | G G | --- --- --- --- g-- --- g-- --- | 2.47 (0.16) | 0.04 | ND |

a.a., amino acid.

Hyphens represent wild-type cry1Ac DNA sequence.

Relative toxicity was calculated as the threshold concentration for native Cry1Ac divided by the threshold concentration for each toxin.

Each mortality estimate is based on two replicates with 9 to 11 P. xylostella larvae tested per replicate. Mortality was not adjusted for control mortality, which ranged from 0 to 10% (mean, 4%). SE, standard error.

Average Cry1Ac percent mortality as reported in prior assays (27).

ND, Not done.

TABLE 2.

Conserved block 4 arginine region

| Toxina | Protein sequenceb |

|---|---|

| Cry1Aa | R Y R V R I R Y A S |

| Cry1Ac | R Y R V R V R Y A S |

| Cry1B | R Y R I G F R Y A S |

| Cry1C | R Y R L R F R Y A S |

| Cry1D | S Y Y I R F R Y A S |

| Cry1E | R Y R L R F R Y A S |

| Cry1F | R Y R A R I R Y A S |

| Cry1G | Q Y R I R V R Y A S |

| Cry1H | Q Y R L R V R F A S |

| Cry1J | R Y R V R I R Y A S |

| Cry2Aa | S Y N L Y L R V S S |

| Cry2Ab | S Y N L Y L R V S S |

| Cry3A | K Y R A R I H Y A S |

| Cry3B | R Y R V R I R Y A S |

| Cry3C | K Y R V R V R Y A T |

| Cry3D | T Y K I R I R Y A S |

| Cry4A | S Y F I R I R Y A S |

| Cry4B | S Y G L R I R Y A A |

| Cry5A | E Y Q I R C R Y A S |

| Cry5B | Q Y T I R I R Y A S |

Sequences were obtained from the following Genbank nucleotide accession numbers (in order): U43605, U43606, X06711, X07518, X54160, X56144, M63897, X58534, Z37527, L32019, M31738, X55416, M22472, A07234, M64478, X59717, Y00423, X07423, L07025, L07027.

Shaded letters represent deviations from the alternating arginine sequence found in conserved block 4 (see reference 13).

Insect cell lawn assays.

Changes in the first (R525) or second (R527) arginine position resulted in either the largest decreases in toxicity by a single mutation (5.4- to 11.9-fold) (R525) or no overt decrease (R527) compared to the wild-type Cry1Ac threshold value (Table 1). Changes in the third (R529) position resulted in a 3.9- to 5.7-fold decrease in toxicity towards Cf1 cells, whereas mutations in the fourth arginine (R531) caused little (3-fold) (R531D) or no (R531G) decreases in toxicity. In general, mutation of the positively charged arginine to negatively charged aspartic acid had a greater effect on toxicity than the change to a neutral glycine. The creation of a double mutant by replacement of arginine with glycine in the first two arginine positions (R525G/R527G) resulted in decreased threshold toxicity levels, which appeared to be additive when compared to effects of the two individual positions. This additive effect suggests that the overall positive charge in the first part of the arginine region is only of moderate importance. In contrast, neutralizing the charge in the latter two positions produced a clone with the largest decrease in toxicity (more than 24-fold), which is much greater than the sum of the two individual mutations alone.

Larval bioassays.

Five mutant toxins (R525D, R525G, R527G, R529D, and R525G/R527G) that were 1.9- to 11-fold less toxic than Cry1Ac in lawn assays were tested further in larval bioassays as well as planar lipid bilayers (Table 1). Interestingly, this group included toxins from the two internal positions that previous Cry1Aa studies in the β17 strand region showed to have altered solubility or proteolytic stability (4). Since activated Cry toxins possess numerous internal trypsin cleavage sites, a good method of assessing deviations from wild-type toxin conformations is to monitor mutant protoxin solubility and proteolytic activation. The purified protoxins isolated from these mutants appeared similar to wild-type Cry1Ac in that they were highly soluble in alkaline buffer and showed normal activation by trypsin (Fig. 1). Although R527G had near-wild-type toxicity as did R531G in lawn assays, it was included for comparison purposes with the double mutant R525G/R527G. The double mutant R529G/R531G could not be included in further tests because its expression in E. coli was poor and sufficient amounts of the purified toxin could not be obtained.

Mean mortality (and standard error) caused by the mutant toxins in the larval bioassay was 100% (0) for R527G, 80% (10) for R525G, 70% (0) for R525D, 65% (5) for R529D, and 45% (5) for the double mutant R525G/R527G. In previously reported results with similar larval bioassays, mean mortality caused by native Cry1Ac was 94% (26). The three mutants that had the lowest toxicity in the larval bioassay (R525D, R529D, and R525G/R527G) also had greatly reduced toxicity in the lawn assay (relative toxicities, 0.08 to 0.18; see Table 1). However, R527G killed 100% in the larval bioassay, but its relative toxicity was 0.53 in the lawn assay. Similarly, R525G killed 80% in the larval bioassay, but its relative toxicity was only 0.18 in the lawn assay. Differences between the two assays could have been caused by interspecific differences (C. fumerifana in the lawn assay versus P. xylostella in the larval bioassay), differences in the assay technique (cultured cells versus live larvae), or both.

Planar lipid bilayers.

The wild-type Cry1Ac toxin and the products obtained from mutation of arginine in position 525, 527, or 529 of the toxin partitioned in phospholipid membranes after a few minutes and at similar concentrations (85 to 170 nM). Well-resolved current jumps were observed, as illustrated in Fig. 2 (upper panels). The number of active channels following protein incorporation into the planar lipid bilayer was variable. In some experiments, it increased from one to four or five during the first 5 to 10 min and remained stable thereafter for tens of minutes to hours.

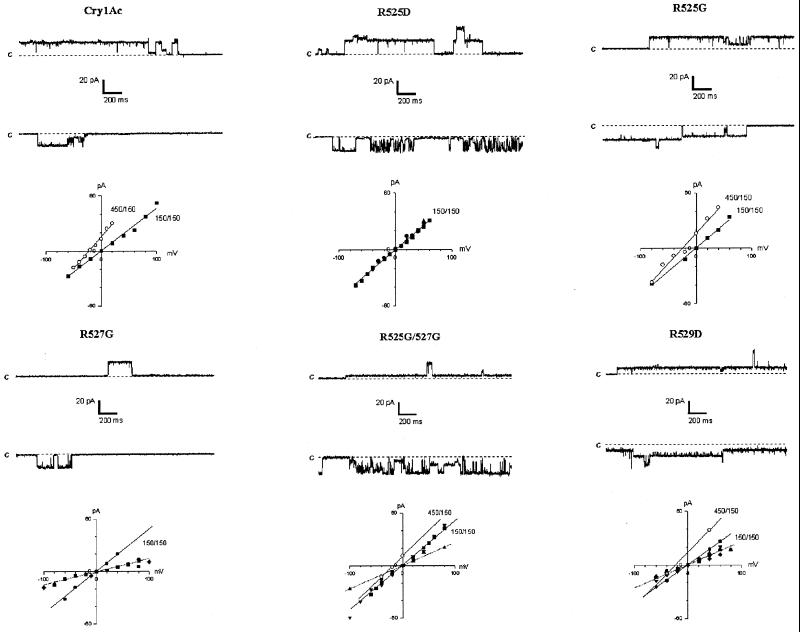

FIG. 2.

Single-channel current traces. Representative single-channel current traces, recorded after the partition of Cry1Ac and the five arginine mutants into planar lipid bilayers separating symmetrical (150 mM cis/150 mM trans) KCl buffer solutions at pH 9.0 are shown in the upper traces (applied voltage, +40 mV), and middle traces (−40 mV). The letter c on the left of the traces indicates the closed state of the channels. Current-voltage relations (I-V curves) of the channels are shown directly under the single-channel current traces. Data points were fitted by linear regression.

Single-channel conductances of Cry1Ac and its mutants were derived from the slopes of linear regression curves (I-V curves) of channel current data recorded for several voltages applied across the lipid bilayer (Fig. 2, lower panels). When current jumps of intermediate levels were rare or difficult to resolve, as was the case with Cry1Ac, R525D, and R525G, only the principal conducting states were considered for conductance determination, i.e., the largest detectable current steps for which direct transitions could be observed between the baseline and the conducting level. For the three other mutants, I-V curves were also obtained for the subconducting states in which the channel currents remained for significant periods of time. Such I-V curves were determined under 150/150 mM KCl (cis/trans) symmetrical ionic conditions for the wild-type toxin and all the mutants. Ion selectivities of Cry1Ac, R525G, R525G/R527G, and R529D were measured by conducting experiments under 450/150 mM KCl (cis/trans) nonsymmetrical conditions. In all cases, the I-V curves were rectilinear, which indicated that the channels did not rectify, i.e., that they passed current equally well in either direction.

In general, replacement of arginines by either a polar residue or a negatively charged residue did not significantly affect channel conductances (Table 3). Under asymmetrical ionic conditions, mutant conductances became larger compared to that of the same mutant under lower ionic conditions, and as with Cry1Ac, the channels were cation selective (Table 3). This was indicated by the fact that their current-voltage relations were shifted to the left, with zero-current voltages, i.e., reversal potentials, becoming more negative by approximately 21 to 27 mV (Fig. 2, lower panels). This shift was consistent with a Nernst equilibrium potential of −27.7 mV calculated for monovalent cations under these conditions (3:1 KCl concentration gradient).

TABLE 3.

Characterization of ion channels by arginine replacement mutants in planar lipid bilayers

| Toxin | Conductance ab (pS)

|

Subconductance ac (pS)

|

Selectivity (Vr)f | Activity level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150/150 mM KCl | 450/150 mM KCl | 150/150 mM KCl | |||

| Cry1Ac | 457 ± 13 (3) | 688 (1) | NDd | Cationic (22.5 mV) | Wild-type |

| R525D | 522 ± 20 (3) | ND | ND | ND | Similar to wild-type |

| R525G | 526 ± 52 (5) | 732 ± 31 (3) | ND | Cationic (26.5 mV) | Similar to wild-type, but difficult to incor-porate into PLBse |

| R527G | 500 (1) | ND | 148 ± 10 (4) | ND | Very low; mutant tends to stay in its sub-conducting state |

| R529D | 424 (1) | 637 ± 27 (2) | 213 ± 11 (4) | Cationic (24 mV) | Low; mutant tends to stay in one or more subconducting states |

| 302 (1) | |||||

| R525G/R527G | 492 ± 65 (4) | 590 (1) | 86 (1) | Cationic (21 mV) | Low |

Mean ± standard error of the mean.

Numbers in parentheses under conductance data indicate the number of experiments in which the principal conductance level could be observed and measured.

Numbers in parentheses under subconductance data indicate the number of experiments in which subconducting states could be observed and reliably determined according to Fox (6).

ND, not determined.

PLBs, planar lipid bilayers.

Vr is the reverse potential (zero-current potential) determined under 450/150 mM KCl (cis/trans) nonsymmetrical ionic conditions.

However, for most mutants, qualitative differences were apparent in their membrane integration capability and channel kinetics (Table 3, last column). Whereas R525D and R525G channel activity was similar to that of Cry1Ac, partition of R525G into the lipid bilayer was more difficult: at an equivalent dose, it took longer for channel activity to be observed. Contrary to the case with Cry1Ac and R525D, R525G did not display fast flickering of channel current when negative voltage was applied. The channels formed by R527G displayed very low activity. They tended to remain closed or in a state in which conductance was about one quarter of the maximum conductance seen for this protein. The double mutant R525G/R527G also displayed low activity at positive voltages. At negative voltages, the channel currents were less stable and displayed significant flickering like those observed with R525D under the same conditions. Finally, the 529D mutant was also less active than the wild-type toxin and remained essentially locked in one of its subconducting states.

DISCUSSION

Sequence alignments of various Cry toxin classes have shown that the most conserved arginine in the alternating arginine region (bloc 4 in DIII) is localized to the fourth or most C-terminal position, followed by the third position, with the first and second positions showing the most variability (Table 2). In Cry1Aa, the second and third arginines are involved in hydrogen bonding to two main chain carbonyl oxygen atoms (R523) or in a salt bridge triad with two other charged residues (R600 and E602), suggesting that these residues as well as the fourth arginine, which also forms a salt bridge, are very important for structural stability (11). The first arginine position in all toxin classes examined (Table 2) can generally form hydrogen bonds and is accessible, unlike the third and fourth positions, to the solvent. In Cry1Ac, structural modeling also predicts that as with Cry1Aa, salt bridges can occur at the third and fourth positions. Among the single-residue mutants, the greatest decrease in toxicity occurred for those in which the first or third arginine (positively charged) was replaced by aspartic acid (negatively charged) rather than glycine (neutral). Why the first arginine position is the one most affected by mutation in in vitro bioassays but not in vivo bioassays is uncertain, but it is presumably due to the inherent differences between the two interspecific assay sytems. Indeed, the immediate question arising from the results derived from this study is whether mutations in these arginines play a direct role in ion channel function or an indirect role due to minor structural alterations causing a secondary effect, such as altered oligomerization in pore creation. Recently our laboratory and another group have presented data supporting an umbrella-like model for DI insertion into membranes (7, 19, 23). One consequence of this mode of insertion would be the approach of the β17 strand, and consequently the alternating arginines, nearer to the mouth of the pore. An increase or decrease in the number of positive charges near the pore mouth would presumably affect pore conductance. In relation to the first arginine position, loss of toxicity may be related to the exposure of this position, unlike the others, to the solvent. Unlike the case with previous studies, we do not see such an alteration in the rate of ion flow through the channel but rather see an increase in the length of time for channel activity to appear. The lower activity level of R526G suggests that membrane permeation was difficult to achieve, presumably due to either a structurally altered toxin or possibly difficulty in properly forming the oligomeric pore structure in the membrane (1).

In an earlier study, Chen et al. (4) were unable to produce protoxins mutated at the second or third arginine position. Considering that the β17 strand is highly similar between the two Cry1A toxins, the ability to express Cry1Ac mutants in the present study was probably due to the different nature of the amino acids substituted in these positions. Mutant toxins at these positions resembled wild-type Cry1Ac both biochemically in their alkaline solubility and protease sensitivity and in bioassays using susceptible insect larvae or, with a few exceptions, in a highly sensitive in vitro lawn assay, on cultured insect cells. When the pore-forming characteristics of these exceptions (R525D, R525G, R527G, R529D, and R525G/R527G) showing slight toxicity differences were examined in planar lipid bilayers, it was determined that the two internal arginine mutants possessed a feature in addition to the low channel activity observed with R525G. Both R527G and R529D formed channels that displayed a tendency to remain in a subconducting state. These data support the notion that structural alterations in this region have an indirect affect on ion channel function, since different subconducting states are generally a reflection of the oligomerization of different pore subunits, or in this case toxin molecules. Either altered toxin oligomerization or more likely a slightly deformed pore may explain why the two internal arginine mutants are more often locked into a subconducting state.

Taken together, our results suggest that the primary role of this conserved β17-strand region is structural stability of the toxin. They also suggest that deviations in ion channel properties of mutant toxins in this region are an indirect consequence of structural alterations during or after membrane integration of the toxin, resulting in an improper pore architecture as manifested by slight differences in ion transport across the membrane.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. M. Mes-Masson for a critical reading of the manuscript and Luc Péloquin, Naomi Finson, and Yong-Biao Liu for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson, A. I., C. Geng, and L. Wu. 1999. Aggregation of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxins upon binding to target insect larval midgut vesicles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2503–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch, D., B. Schipper, H. van der Klei, R. De Maagd, and W. J. Stiekema. 1994. Domains of Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins involved in insecticidal activity. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 4:449. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, X. J., M. K. Lee, and D. H. Dean. 1993. Site-directed mutations in a highly conserved region of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin affect inhibition of short circuit current across Bombyx mori midguts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9041–9045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Maagd, R. A., H. van der Klei, P. L. Bakker, W. J. Stiekema, and D. Bosch. 1996. Different domains of Bacillus thuringiensis delta endotoxins can bind to insect midgut membrane proteins on ligand blots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2753–2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox, J. A. 1987. Ion channel subconductance states. J. Membr. Biol. 97:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gazit, E., N. Burshtein, D. J. Ellar, T. Sawyer, and Y. Shai. 1997. Bacillus thuringiensis cytolytic toxin associates specifically with its synthetic helices A and C in the membrane bound state. Implications for the assembly of oligomeric transmembrane pores. Biochemistry 36:15546–15554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazit, E., and Y. Shai. 1995. The assembly and organization of the alpha 5 and alpha 7 helices from the pore-forming domain of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin. Relevance to a functional model. J. Biol. Chem. 270:2571–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge, A. Z., N. I. Shivarova, and D. H. Dean. 1989. Location of the Bombyx mori specificity domain on a Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:4037–4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gringorten, J. L., D. P. Witt, R. E. Milne, P. G. Fast, S. S. Sohi, and K. Van Frankenhuyzen. 1990. An in vitro system for testing Bacillus thuringiensis toxins: the lawn assay. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 56:237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grochulski, P., L. Masson, S. Borisova, M. Pusztai-Carey, J. L. Schwartz, R. Brousseau, and M. Cygler. 1995. Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA(a) insecticidal toxin: crystal structure and channel formation. J. Mol. Biol. 254:447–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann, C., H. Vanderbruggen, H. Höfte, J. van Rie, S. Jansens, and H. van Mellaert. 1988. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins is correlated with the presence of high-affinity binding sites in the brush border membrane of target insect midguts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:7844–7848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Höfte, H., and H. R. Whiteley. 1989. Insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol. Rev. 53:242–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowles, B. H., and D. J. Ellar. 1987. Colloid-osmotic lysis is a general feature of the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxins with different insect specificity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 924:509–518. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, M. K., B. A. Young, and D. H. Dean. 1995. Domain III exchanges of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA toxins affect binding to different gypsy moth midgut receptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 216:306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, J. D., J. Carroll, and D. J. Ellar. 1991. Crystal structure of insecticidal delta-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.5 A resolution. Nature 353:815–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masson, L., A. Mazza, L. Gringorten, D. Baines, V. Aneliunas, and R. Brousseau. 1994. Specificity domain localization of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxins is highly dependent on the bioassay system. Mol. Microbiol. 14:851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masson, L., G. Préfontaine, L. Péloquin, P. C. K. Lau, and R. Brousseau. 1989. Comparative analysis of the individual protoxin components in P1 crystals of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki isolates NRD-12 and HD-1. Biochem. J. 269:507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masson, L., B. E. Tabashnik, Y. B. Liu, R. Brousseau, and J. L. Schwartz. 1999. Helix 4 of the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Aa toxin lines the lumen of the ion channel. J. Biol. Chem. 274:31996–32000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnepf, E., N. Crickmore, J. van Rie, D. Lereclus, J. Baum, J. Feitelson, D. R. Zeigler, and D. H. Dean. 1998. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:775–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnepf, H. E., K. Tomczak, J. P. Ortega, and H. R. Whiteley. 1990. Specificity determining regions of a lepidopteran-specific insecticidal protein produced by Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Biol. Chem. 265:20923–20930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz, J. L., L. Garneau, D. Savaria, L. Masson, R. Brousseau, and E. Rousseau. 1993. Lepidopteran-specific crystal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis form cation- and anion-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers. J. Membr. Biol. 132:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz, J. L., M. Juteau, P. Grochulski, M. Cygler, G. Préfontaine, R. Brousseau, and L. Masson. 1997. Restriction of intramolecular movements within the Cry1Aa toxin molecule of Bacillus thuringiensis through disulfide bond engineering. FEBS Lett. 410:397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz, J. L., L. Potvin, X. J. Chen, R. Brousseau, R. Laprade, and D. H. Dean. 1997. Single site mutations in the conserved alternating arginine region affect ionic channels formed by Cry1Aa, a Bacillus thuringiensis toxin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3978–3984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabashnik, B. E., N. Finson, M. W. Johnson, and W. J. Moar. 1993. Resistance to toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki causes minimal cross-resistance to B. thuringiensis subsp. aizawai in the diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1332–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabashnik, B. E., Y. B. Liu, N. Finson, L. Masson, and D. G. Heckel. 1997. One gene in diamondback moth confers resistance to four Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1640–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Rie, J., S. Jansens, H. Höfte, D. Degheele, and H. Van Mellaert. 1990. Receptors on the brush border membrane of the insect midgut as determinants of the specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1378–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walters, F. S., S. L. Slatin, C. A. Kulesza, and L. H. English. 1993. Ion channel activity of N-terminal fragments from CryIA(c) delta-endotoxin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 196:921–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfersberger, M. G., X. J. Chen, and D. H. Dean. 1996. Site-directed mutations in the third domain of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin CryIAa affect its ability to increase the permeability of Bombyx mori midgut brush border membrane vesicles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:279–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]