Abstract

Recombination enhancer (RE) is essential for regulating donor preference during yeast mating type switching. In this study, by using minichromosome affinity purification (MAP) and mass spectrometry, we found that yeast Ku80p is associated with RE in MATa cells. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays confirmed its occupancy in vivo. Deletion of YKU80 results in altered chromatin structure in the RE region and more importantly causes a dramatic decrease of HML usage in MATa cells. We also detect directional movement of yKu80p from the RE towards HML during switching. These results indicate a novel function of yeast Ku80p in regulating mating type switching.

The mating type of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is determined by two alleles of the mating type (MAT) loci which contain either a or α information (13, 21). Yeast can change mating type every other generation and during this process, two transcriptionally silent haploid mating (HM) loci, HMLα and HMRa, are required. Conversion of mating type begins with a site-specific cut of the HO endonuclease at the MAT locus. The resulting double-strand break (DSB) is then repaired by homologous recombination using either HML or HMR as the template (13). This event is highly directional. MATa recombines with HML 90% of the time, while MATα uses HMR as the donor with an efficiency of 85% (13).

A cis-acting element called the recombination enhancer (RE) has been identified as critical in regulating donor preference (34). It is an approximately 730-bp DNA sequence located ∼30 kb from the left end of chromosome III, ∼17 kb away from HML (33). RE contains no open reading frame. However, at least two noncoding RNAs were found to be transcribed from this region (27). RE has been shown to activate a ∼40-kb region of the left arm of chromosome III, including HMLα, for recombination in MATa cells (33). In the presence of a wild-type RE, MATa cells use HML ∼90% of the time. However, in an RE deletion strain, HML usage drops to ∼10% (33).

Sequence comparison of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces carlsbergensis revealed four conserved subdomains in the RE region, A, B, C, and D, which are indispensable for its function (32). Among these, region C contains a Matα2p/Mcm1p binding site and region D features unique TTT(A/G) repeats (32). Recent sequence alignment analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces bayanus identified a novel conserved E region which also contains TTT(A/G) repeats (26).

High-resolution micrococcal nuclease mapping of chromatin structure around the RE region demonstrated an inverse correlation of RE function and its organized nucleosome structure. In MATα cells, where RE is inactive, it is packaged as tightly positioned nucleosomes. In MATa cells, where RE is active, those positioned nucleosomes are replaced by a distinctive pattern of hypersensitive sites flanked by two footprints (31). This different chromatin structure in MATa and MATα cells strongly implies that trans-acting elements might bind to RE and regulate its function.

In α cells, repressor Matα2p and Tup1p are essential for repressing RE, probably by organizing the nucleosome arrays (31). On the other hand, in MATa cells, Mcm1p has been shown to be crucial for donor preference (32). In addition, Chl1p, a putative DNA helicase, has been suggested to play a minor role in switching (30). Recently, yeast forkhead proteins Fkh1p and Fkh2p have been shown to be recruited to RE and regulate mating type switching (26). However, deletion of the FKH1 and FHK2 genes does not completely abolish the donor preference in a cells, suggesting that other factors may also contribute to this process (26).

Here we use the minichromosome affinity purification (MAP) (9) combined with mass spectrometry to screen for proteins that bind to RE. We found that yeast Ku80p (yKu80p) is a protein that associates with RE in vivo. yKu80p is a yeast homolog of human Ku80p, which belongs to a conserved protein family that is critical for many DNA repair events (3, 17, 28). yKu80p has been implicated in nonhomologous end joining (5, 6), homologous recombination (4), maintenance of telomeres (14), and DNA replication (7). Here we demonstrate that deletion of YKU80 causes altered chromatin structure around the RE and defective donor preference in a cells, indicating a novel function of yKu80p in regulating yeast mating type switching. Moreover, the directional movement of yKu80p along the left arm of chromosome III during switching may shed light on the molecular mechanism of donor preference.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and minichromosome construction.

The yeast strains used in this study are isogenic (except the MAT locus) and are listed here. YCR101 (MATa ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 pALTRE); YCR102 (MATα ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 pALTRE); YCR103 (MATa ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 pALT); YCR201 (MATa ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 YKU80-myc KANMX6); YCR202 (MATa ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 YKU80-myc KANMX6); YCR300 (ho MATa ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 ade3::GAL HO YKU80::KANMX6); YCR501 (MATa ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 YKU80-myc KANMX6 pALTRE); YCR502 (MATα ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 YKU80-myc KANMX6 pALTRE); YCR503 (MATa ade 2-101 ura3-52 his3-200 leu2-1 trp1-63 lys2-1 YKU80-myc KANMX6 pALT); YCR601 (ho HMLα MATa hmrΔ::HMRα-B ade1,112 lys5 leu2-3 ura3-52 trp1::hisG ade3::GAL HO YKU80::KANMX6); YCR602 (ho HMLα MATa hmrΔ::HMRα-B ade1,112 lys5 leu2-3 ura3-52 trp1::hisG ade3::GAL HO YKU70::KANMX6); YCR603 (ho HMLα MATa hmrΔ::HMRα-B ade1,112 lys5 leu2-3 ura3-52 trp1::hisG ade3::GAL HO YKU80::KANMX6 FKH1::URA3-1); YCR604 (ho HMLα MATα hmrΔ::HMRα-B ade1,112 lys5 leu2-3 ura3-52 trp1::hisG ade3::GAL HO YKU80::KANMX6); KW-a (ho HMLα MATa HMRa ade1-112 lys5 leu2-3 ura3-52 trp1::hisG ade3::GAL HO); YCR701 (ho HMLα MATa HMRa ade1-112 lys5 leu2-3 ura3-52 trp1::hisG ade3::GAL HO); CWWT (ho HMLα MATa hmrΔ::HMRα-B ade1-100 ura3-53 leu2-3112); and CWWT-α (ho HMLα MATα hmrΔ::HMRα-B ade1-100 ura3-53 leu2-3,112) (S. Ercan, unpublished).

All strains used for the minichromosome purification and micrococcal nuclease mapping are derived from YPH499 and YPH500. Strains used for the mating type switching assay are derived from either KW-a or DBY745 (34). Synthetic medium containing the appropriate supplements was used to select and maintain the trp1 minichromosome.

For the pRE-ALT construction, a 1.4-kb RE fragment was amplified by PCR, cloned into an engineered AvaI site of the minichromosome backbone pALT (9). pRE-ALT was then digested with SphI to remove bacterial sequences. The resulting DNA was then religated (RE-ALT) and transformed into yeast. To ensure the correct transcription of TRP1 in α cells, a ∼200-bp insulator was cloned between Matα2p binding site and TRP1 (1). The deletion and epitope tagged strains were generated by the standard one-step PCR method (2, 16). yKu80p was tagged with a 13-myc epitope at its carboxyl termini in all strains applied. Tagging does not affect the normal functionality of yKu80p, since the resulting strains do not display any temperature sensitivity phenotype as in the yKu80 null mutant, and more importantly, mating type switching in these strains resembles that in wild-type cells (Fig. 5A).

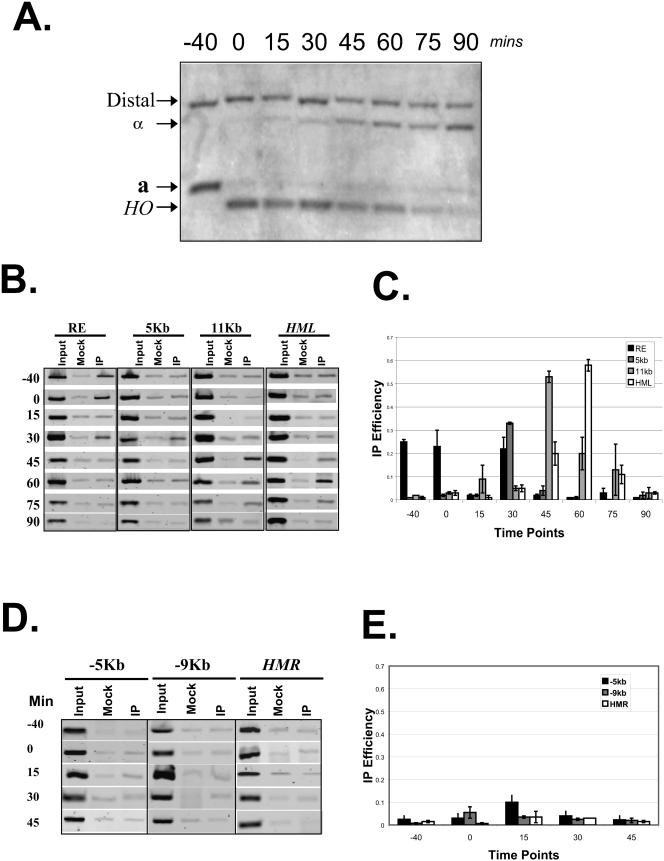

FIG.5.

Dynamic interaction of yKu80p and the left arm of chromosome III during switching. (A) Physical monitoring of the switching of the strain containing a myc-tagged yKu80p (YCR701). Mating type switching was initiated by galactose induction of HO expression. Samples were collected at eight time points: before HO induction (labeled −40), 40 min after induction (labeled 0, since it is the starting point of DSB repair), 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 min after transfer to YPD medium. DNA was extracted and digested with StyI before Southern blotting with the probe indicated in Fig. 4A. The a-, α-, and HO-specific bands generated by StyI digestion are indicated. (B) A yeast strain containing a Myc-tagged yKu80p (YCR701) was induced for mating type switching as described above. Cells were collected at −40, 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 min after the start of switching. DNA was extracted and subjected to ChIP analysis using primers designed to amplify regions of the RE, and 5 kb and 11 kb away from RE the proximal HML. (C) Quantification of ChIP assays from three independent experiments. The cross-linking efficiency is normalized to the mock immunoprecipitation for all primer sets. (D) YCR701 was induced for mating type switching as described above. Cells were collected at −40, 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90 min after the start of switching. DNA was extracted and subjected to ChIP analysis using primers designed to amplify regions 5 kb and 11 kb away from RE, the proximal HMR, and the HMR. (E) Quantification of the above experiments from two repetitions.

Minichromosome affinity purification and mass spectrometry.

Minichromosome affinity purification was carried out as previously described (9) with a few modifications. After zymolyase treatment and homogenization of the cells, minichromosomes were allowed to diffuse passively from the nuclei on ice then loaded onto LacI-Z affinity column. They were subsequently eluted with 300 mM NaCl and 1 mM isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Proteins from the minichromosome eluate were resolved using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and silver stained. Interesting bands were excised and subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI)-mass spectrometry (MS) analysis by the Mass Spectrometry facility at Penn State University.

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed as described (15). Cells were harvested at an optical density of about 1.0 and chromatin was sheared to ∼500 bp by sonication. Immunoprecipitation was performed using 9E10 anti-myc antibody (Upstate) and protein A beads (Promega). DNA was then purified and PCR was performed using primers that specific amplify the RE region (sequences available upon request, contact chr@stowers-institute.org).

Micrococcal nuclease mapping.

The micrococcal nuclease mapping assay was preformed as previously described (31). Nuclei isolated from cells grown to log phase were digested with increasing concentrations of micrococcal nuclease. The cleavage sites were determined by primer extension using Taq polymerase (24). The primer used in this study was a290 (5′-GCTGGAAGTGCAGAACAAAGAGG-3′) (31).

Mating type switching assay.

Cells were grown in YPL (yeast extract, peptone and lactic acid) to an optical density of ∼0.4 and then 2% galactose was added to the medium to induce HO expression (34). After 40 min, cells were washed and resuspended in YPD (yeast extract, peptone, and dextrose) to complete switching at 30°C. DNA was extracted from cells collected at different time points, cut with either StyI or BamHI and HindIII, and then analyzed by Southern blots.

RESULTS

Searching for proteins that bind to RE using MAP.

To understand the function of the recombination enhancer, we started to look for proteins that bind to the active form of RE in MATa cells using minichromosome affinity purification (9). A ∼1.4-kb RE segment (29192 to 30612) containing two Mcm1p/Matα2p binding sites as well as the conserved C and D and part of the E regions was cloned into the minichromosome backbone pALT at the hypersensitive region B site (9). The new construct, pRE-ALT, was digested with SphI to eliminate bacterial sequences. The remaining portion was then circularized and used to transform MATa and MATα cells.

Harvested yeast cells were treated with zymolyase and homogenized to release nuclei. Minichromosomes were then allowed to diffuse passively from the nuclei on ice and subsequently loaded onto a LacI-Z affinity column. After extensive washing, minichromosomes were eluted with 300 mM NaCl and 1 mM IPTG. Micrococcal nuclease mapping of MAP eluates revealed that the micrococcal nuclease digestion pattern of the RE region from purified minichromosomes was similar to that of the genomic locus (data not shown), suggesting that potential binding proteins remained associated. Proteins bound to the RE-containing minichromosomes from both a and α cells were then revealed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining (Fig. 1A).

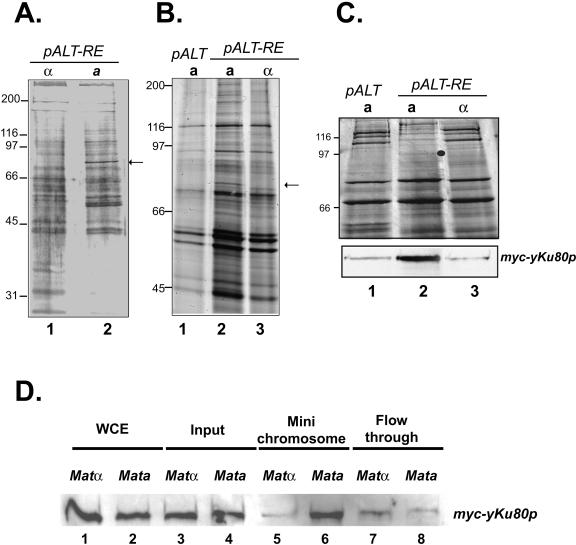

FIG. 1.

yKu80p specifically interacts with RE minichromosome isolated from a cells. (A) Proteins bound to the RE minichromosomes isolated from MATa cells (YCR101) (lane 2) or MATα cells (YCR102) (lane 1), were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and visualized with silver staining. The arrow indicates a ∼75-kDa band that is present only in the MATa cell eluate but not in that from MATα cells. This band was excised and subjected to mass spectrometry. We identified six peptide hits for the yKu80p protein (KFVKSLTLCR, LVEVLGIKKVDK, VEAFPATKAVSGLNRK, IPDLETLLKRGEQHSR, FVKSLTLCRLPFAEDER, and IYNMNELLVEITSPATSVVKPVR). (B) The above experiment was repeated with strain YCR101 (pALT-RE in MATa), YCR102 (pALT-RE in MATα) and YCR103 (pALT in MATa) The yKu80p band (arrow) was only observed on minichromosomes containing the RE when isolated from a cells. (C) Minichromosome bound proteins were isolated from YCR501, YCR502, and YCR503 which contained a myc-tagged copy of yKu80p, separated by 11% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. Both silver staining and Western blotting using anti-myc antibody were performed to the samples. From this strain the specific band (dot represent the correct size of Myc-tagged yKu80p) was shifted in size due to the tag and again found only to RE-containing minichromosomes when isolated from a cells. (D) RE minichromosomes were isolated using the MAP method from a (YCR501) and α (YCR502) cells containing myc-tagged yKu80p. The amount of minichromosomes loaded on the gel was normalized by DNA content measured both by ethidium bromide (EB) staining and Southern blotting. Western blotting was performed with an antibody against the Myc epitope tag.

A ∼75-kDa band which appeared only in a cells but not in α cells was excised, trypsinized, and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis. Six peptide hits of this band match to yKu80p, the yeast homolog of human DNA repair protein Ku80p (Fig. 1A). To further validate this result, we repeated the minichromosome isolation experiment in cells carrying only the vector pALT. The Ku80 band was only found on the RE containing minichromosomes isolated from a cells (Fig. 1B). This result was confirmed by Western blotting of minichromosomes isolated from Myc-tagged YKU80 strains using anti-Myc antibody (Fig. 1C, also see below).

yKu80p binds to RE in vivo.

To confirm that yKu80p indeed associates with RE in a cells, we sought to detect this protein in isolated minichromosomes. To this end, RE-ALT plasmid was introduced to both a and α cells bearing Myc-tagged yKu80p. Proteins bound to purified minichromosomes were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-myc antibody. The amount of minichromosome loaded on the gel was normalized based on DNA content in each fraction, measured by ethidium bromide staining and Southern blotting (data not shown). We found a significant amount of yKu80p in the minichromosome fraction isolated from a cells (Fig. 1D, lane 6, and 1C, lane2), whereas minichromosomes from α cells only contain trace amount of yKu80p (Fig. 1D, lane 5). Thus, yKu80p preferentially bound to the active form of RE, which is consistent with the fact that RE only functions in MATa cells (33). The faint yKu80p band observed in α cells may reflect the interaction of the protein and the ARS sequence in the minichromosome backbone (23).

To further address the interaction between yKu80p and RE in living cells, we took advantage of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. Yeast strains containing genomic epitope tagged yKu80p were cross-linked with formaldehyde. Whole cell extracts were then subjected to sonication to shear chromatin DNA into an average size of 500 bp. Immunoprecipitation was carried out with anti-myc antibody, and precipitated DNA was detected by quantitative PCR using the primer set covering D and part of the E region within RE (Fig. 2A). yKu80p cross-linked to the RE region only in a cells but not α cells (Fig. 2B and 2C). As a positive control we repeated the observation that yKu80p binds to the sequence 0.5 kb away from the right telomere of chromosome VI, but not to DNA 7 kb from that telomere (19). This is a good control since the occupancy of yKu80p at the telomeric region is indistinguishable between a cells and α cells in contrast to its binding at RE. Together these results strongly indicate that yKu80p associates with RE in a cells in vivo.

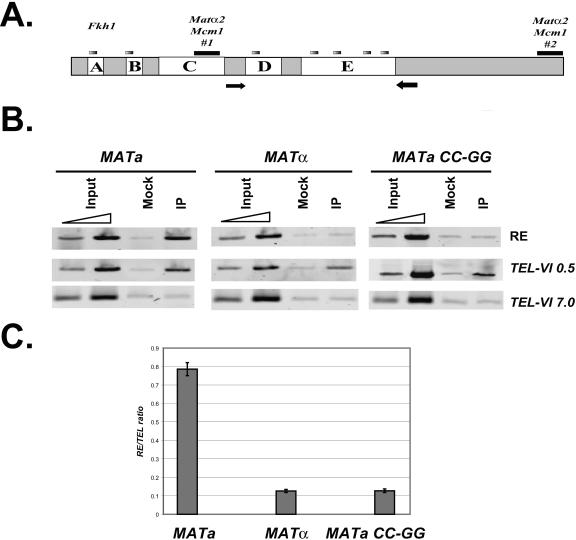

FIG. 2.

Binding of yKu80p to the RE in vivo requires an intact Mcm1p binding site. (A) Schematic diagram of the RE region. Five conserved regions are labeled A, B, C, D, and E. Gray bars indicate putative binding sites of Fhk1p and black bars represent the two Mcm1p binding sites. Arrows show the primer set (RE) used for ChIP analysis. (B) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from a (YCR201), α (YCR202) and a with GG-to-CC mutation (CW157) cells containing Myc-tagged yKu80p, sonicated to generate average DNA fragments of approximately 500 bp and subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc antibody. Quantitative PCR was performed in parallel on input DNA, mock (no antibody), and myc-yKu80p immunoprecipitated DNA (IP) with primers corresponding to the RE region. PCR with primer sets that amplify regions 0.5 kb and 7 kb from the right telomere of the chromosome VI were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (C) Quantification of the experiment in B and repeats. The results from three independent experiments are shown. RE/TEL ratio is defined as (IP − mock)RE/(IP − mock)TEL0.5.

We then tried to identify the cis element that is important for yKu80p recruitment. One of the most important features of the RE is the Mcm1p binding site. A mere two base pair mutation GG to CC completely abolished both the RE function and its unique chromatin structure (32). Thus, we wanted to test whether this DNA segment is also essential for the binding of yKu80p to the RE. Using the ChIP approach, we analyzed the interaction of yKu80p and the RE in both wild-type and an Mcm1p binding site mutation strain described above. As shown in Fig. 2B, the myc-yKu80p cross-linking signal was reduced to background level in the mutant. This indicates that an intact Mcm1p binding site is essential for the interaction of the yKu80p to this region.

Loss of yKu80p leads to altered nucleosome structure of RE in a cells.

In MATα cells, where RE is inactive, tightly positioned nucleosomes cover this region. In MATa cells, where RE is active, those positioned nucleosomes are disrupted and unique hypersensitive sites and footprints appear (31). Surprisingly, when RE's function is abolished in a MATa strain containing a GG-to-CC mutation of the Mcm1p binding site, the micrococcal nuclease digestion pattern at the RE resembles that of the α cells (32). This suggests that local chromatin structure may play a role in regulating RE's function.

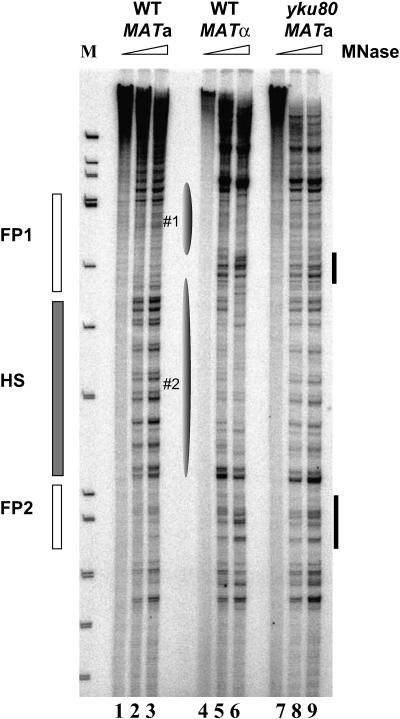

To investigate whether yKu80p affects RE chromatin structure, we mapped this region using micrococcal nuclease digestion in a MATa strain bearing a deletion of YKU80. The digestion patterns of the RE in wild-type a (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 3) and α (lanes 4 to 6) cells are consistent with previous observations (31). In Δyku80 a cells, chromatin structure around the RE has undergone significant changes compared to that of wild-type MATa cells (compare lanes 1 to 3 and 7 to 9), specifically, less intense hypersensitive bands and the loss of the footprints 1 and 2 flanking it. The overall digestion pattern in a Δyku80 deletion strain resembles that of wild-type α cells where RE is inactive and yKu80p does not bind to it (Fig. 1 and 2), suggesting that the association of yKu80p with RE contributes to the disruption of the nucleosomes positioned in this region. The remaining weak hypersensitive site signal may indicate yKu80p is not the only factor that affects the chromatin structure of this region. The chromatin pattern changes caused by deletion of YKU80 are similar to that found in the mcm1-5 mutant as previously reported (32). This is consistent with the idea that yKu80p acts through Mcm1p at the RE (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 3.

Chromatin structure of RE in MATa cells was altered upon deletion of the YKU80 gene. High-resolution chromatin structure of the Watson strand of the RE region in wild-type a (YPH499), α (YPH500), and yku80Δ a (YCR300) strains using primer c290 (31) is shown. Solid gray and blank rectangular boxes represent the location of the hypersensitive sites and footprints, respectively, in wild-type a cells; Ellipses correspond to tightly positioned nucleosomes in α cells. The black bars indicate altered digestion patterns upon deletion of YKU80 in a cells.

Donor preference is defective in Δyku80 deletion MATa strain.

We next asked whether yKu80p affects mating type switching upon binding to RE. First, we monitored the kinetics of the double strand break repair during a to α switching in the absence of yKu80p. YKU80 was deleted in a MATa strain containing an HO gene under the control of the GAL10 promoter. It is important to note that while the GAL10-HO inducible system has been a powerful tool in the study of double strand break repair and mating type switching in yeast, it is formally possible that some events in switching including the role of yKu80p may differ in a wild-type HO background. Cells were grown to an optical density of 0.4 to 0.6 in lactic acid medium before induction (with 2% galactose) of HO expression (see Materials and Methods). After 40 min of induction, cells were transferred to dextrose medium to shut down HO expression. At this point, the cells started to repair the double-strand break and complete the switching process. Genomic DNA was extracted from cells collected at different time points, digested with StyI, and subjected to Southern blotting using a probe adjacent to the MAT locus (Fig. 4A).

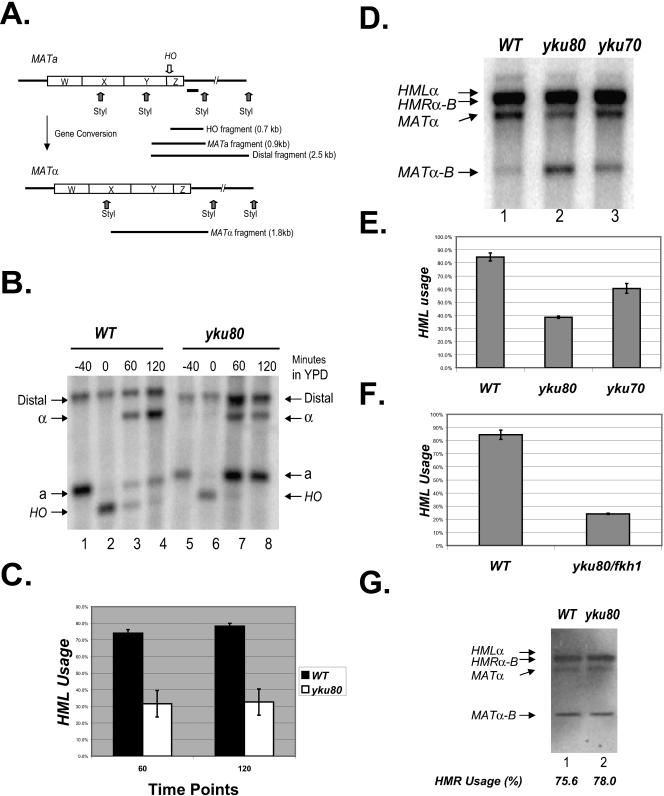

FIG. 4.

yKu80p affects yeast mating type switching and regulates donor preference. (A) Schematic illustration of the physical analysis of mating type switching. The HO cutting site and StyI cleavage sites are shown as the arrows. The location of the probe for Southern blotting is indicated as a black bar. (B) Mating type switching of wild-type (KW-a) and yku80Δ (YCR300) cells was initiated by galactose induction of HO expression. Samples were collected at four time points: before HO induction (lanes 1 and 5, labeled −40), 40 min after induction (lanes 2 and 6, labeled 0, since it is the starting point of DSB repair), 1 hour (lanes 3 and 7), and 2 hours (lanes 4 and 8) after transfer to YPD medium. DNA was extracted and digested with StyI before Southern blotting with the probe indicated in panel A. The a-, α-, and HO-specific bands generated by StyI digestion are indicated. The ratio of the intensity of a and α signals measured by ImageQuant software was used to determine the a-to-α switching efficiency. (C) Quantification of the above experiment from three independent repetitions. (D) DNA was extracted from wild-type (CWWT), yku80Δ (YCR601) and yku70Δ (YCR602) cells 2 h after the HO induction and digested with BamHI and HindIII before blotting with the Yα probe which can detect the four specific bands labeled above. Completion of switching generates MATα band when cell chooses HML or MATα-B band when HMR is used as the donor. (E) Donor preference was determined by comparing the intensity of the MATα and MATα-B bands using ImageQuant. Error bars reflect results from three independent experiments. (F) Switching assay was performed using wild-type (CWWT) and Δyku80/Δfkh1 (YCR603) strains. Donor preference was determined as above. (G) Switching assay was performed on CWWT-α and YCR604 to measure α to a switching. HMR usage is indicated beneath the lane number.

Forty minutes following HO induction (the zero time point), bands representing efficient cleavage of the HO site at the MATa locus were detected in both the wild-type and the Δyku80 strains (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 6, compare bands labeled a and HO). Complete switching to MATα generates a novel 1.8-kb DNA fragment (labeled α) which is visible one hour after the end of induction in the wild-type cells (Fig. 4B, lane 3) and by 2 hours, 85% of the wild-type a cells have successfully switched to MATα (Fig. 4B, lane 4). In the Δyku80 strain, the gene conversion event was abnormal: less than 40% of the a cells switched to MATα at 1 and 2 h as shown in Fig. 4B (lanes 7 and 8, compare bands a and α). The use of the wrong donor in yKu80 is reminiscent of the mating switching defect caused by the Mcm1 binding site mutation (32), which again reinforces the notion that yKu80p might function through Mcm1p at RE (Fig. 2B and Fig. 3).

It is worth noting that the yku80 deletion strain does not have a defect in general DNA repair during switching, since HO cleavage in both the wild-type and deletion cells were almost completely repaired after 1 to 2 h in dextrose medium (Fig. 4B, compare bands HO in lanes 2 to 4 and 6 to 8). This result strongly suggested that yKu80p is involved in yeast mating type switching by a means independent of its general DNA repair function. However, there are two possible interpretations for this observation: the deletion of YKU80 can specifically affect the donor preference or it may just impair the overall homologous recombination process.

To distinguish between these two possibilities, we tested the direct involvement of yKu80p in donor preference in an assay where YKU80 is deleted in a strain carrying a modified HMRα-B and wild-type HMLα (34). Following a similar switching assay procedure, DNA was extracted and digested with BamHI and HindIII. Subsequent Southern blotting was performed using a probe detecting the Yα-specific sequence. Since HMRα-B has an engineered BamHI site, it can be distinguished from HMLα by the different size of DNA fragments generated from restriction endonuclease cleavage (compare bands MATα-B and MATα). Donor preference is directly reflected by the ratio of these two bands.

Shown in Fig. 4D and 4E, about 85% of wild-type a cells chose HMLα as the donor during switching. In contrast, cells without yKu80p choose the correct donor, HMLα, only 40% of the time, while the usage of the wrong donor, HMRα-B, increased to 60%. Based on this result and that of the first switching assay (Fig. 4B), we conclude that yKu80p plays an important role in MATa cells to maintain correct donor preference during switching. This involvement is specific in a cells, where RE is active. Deletion of YKU80 does not alter the mating conversion from α to a (Fig. 4G), implying that the DNA repair and telomere silencing functions of yKu80p are not involved in donor preference.

The YKU70 deletion strain was also included in this assay since previous study has shown that yKu80p and yKu70p usually act as a heterodimer (4). Interestingly, we found that yKu70p moderately affects the donor preference (65% HML usage, see Fig. 4D and 4E). Moreover, we have myc tagged yKu70p and found by ChIP that it does bind to the RE in vivo (data not shown). This is somewhat different from a previous observation (17). Mages et al. have reported that after 6 h of HO induction, there was a more than 60% decrease in mating type switching in a yku70 deletion strain (from ∼30% of the wild-type level to ∼10% of that in Δyku70) (17). However, the overall low switching rate in both wild-type and Δyku70 deletion strains in their assay, possibly due to overexposure to the HO endonuclease, may cause the discrepancy between the two results. We use transient HO expression (<40 min) in our study, thinking this better mimics the in vivo switching process.

It has been shown that the forkhead proteins, especially Fkh1p, are essential in the process of donor preference (26). However, like yKu80p, cells deleted of this protein still maintain partial ability to choose the correct donor (26). Thus, it is possible that yKu80p and Fkh1p play redundant roles in donor preference. To address this possibility, we performed the switching assay using a strain deleted of both FKH1 and YKU80. As shown in Fig. 4F, the usage of HML in the double deletion cells drops to 22% which is significantly lower than that of either single deletion strain and close to the level of the Mcm1 binding site mutation or RE deletion cells (32). This result suggests that Fkh1p and yKu80p may act in concert to regulate the RE function during switching, supporting the notion proposed previously that RE has a redundant mechanism for activating the left arm of chromosome III (26).

Dynamic Interaction of yKu80p with the left arm of chromosome III during mating type switching.

One of the hypotheses regarding the function of the RE in donor preference is that the unique chromatin structure of the RE in a cells serves as an entry point for the DSB and the recombination machinery to start homology searching and DNA repair (31). If this is the case, it is possible that the DSB is brought to the vicinity of the RE and then tracks along the left arm of chromosome III and samples different regions before it reaches the final destination, HML. Since yKu80p is one of the known proteins that bind to both the DSB at the MAT locus (11) and RE, we speculate that yKu80p might play a leading role in such a searching process.

To monitor the kinetics of yKu80p occupancy on chromosome III during switching, we constructed a strain containing a Myc-tagged yKu80p in a GAL10 controlled HO background. Switching was induced by addition of galactose as previously described. First we tested the a to α conversion in the myc-YKU80 strain. Cell samples were collected with 15-min intervals and genomic DNA of each sample was prepared and subjected to the switching assay (Fig. 5A). The switching process of the myc-YKU80 strain resembles that of the wild-type and is largely completed within 90 min (Fig. 5A).

Then we monitored the interaction of yKu80p with the left arm of chromosome III by ChIP analysis (Fig. 5B to E) using primer sets designed to amplify regions from the RE towards either HML or HMR. As shown in Fig. 5B and consistent with previous experiment (Fig. 2), yKu80p was cross-linked to RE before the induction of HO cleavage (−40). The cross-linking signal remained after the generation of the DSB (Fig. 5B, zero time point). However, the signal suddenly dropped to background 15 min after the start of switching. Interestingly, 30 min after the beginning of switching, yKu80p was found to cross-linked to RE again. This phenomenon might be explained by masking of the Myc-yKu80p epitope by other proteins during the invasion of the DSB and the recombination machinery in the RE region. Alternatively, it is possible that yKu80p transiently leaves the RE but then returns by the 30 min time point.

Our data show that the recruitment of yKu80p to the RE peaks 30 min after the start of switching (Fig. 5B). This signal then gradually disappears. The association of yKu80p with the region at 5 kb from the RE HML proximal starts about the same time and the binding is weakened after 45 min. The strongest binding signal of the yKu80p to 11-kb HML proximal was detected 45 min after the start of DNA repair. By 60 min we saw significant association of the yKu80p and the donor sequence HML. At the 90 min time point, when the switching is largely completed, we did not observe significant cross-linking of yKu80p to the left arm of chromosome III (Fig. 5B, bottom panel). Notably, throughout the whole switching process, yKu80p does not seem to bind to HMR or a region 5kb right of the RE (Fig. 5D and 5E) at any point. This is consistent with the idea that yKu80p helps facilitate in donor selection of the HML. In summary, yKu80p appears to move form its initial binding site of the RE towards the HML along the left arm of chromosome III in a directional manner during switching.

DISCUSSION

Minichromosome affinity purification, initially developed by Dean and Simpson (8), has successfully addressed questions in several aspects of chromosome structure and gene regulation (9, 20, 22, 25). This report indicates that MAP, coupled with mass spectrometry, is a valuable screening technique to detect in vivo protein-DNA interactions and to recover trans-acting proteins. This strategy leads us to discover a novel player (yKu80p) in the regulation of RE and mating type switching. We confirmed this result by showing that yKu80p binds to RE in vivo and participates in the donor preference.

MATa and MATα cells employ different mechanisms in choosing the correct donor during switching: The HML in MATa cell requires activation of a large region of the left arm of chromosome III to “outcompete” HMR (33). On the other hand, in MATα cells, HMR serves as the “default” donor (34, 35) when the HML is not available for recombination. A study that combined immunofluorescence and in situ hybridization indeed revealed that the “cold” HML in α cells is located near the nuclear periphery and packed into heterochromatin (12). It is speculated that in a cells, a change of the higher-order chromatin architecture may reverse the inaccessibility of the left arm of chromosome III and make it open for recombination. The RE has been shown to be essential in this activating process (26, 32, 33).

Besides its conserved subdomains, protein factors are also required to help carry out RE function. In a cells, a MADS family protein, Mcm1p, regulates RE by possibly opening up the chromatin structure of this region and making it accessible for binding of other factors (26; S. Ercan and R. T. Simpson, unpublished data). Here, we demonstrate that deletion of YKU80 results in some very similar phenotypes as those in the Mcm1 binding site mutant and Mcm1p mutant (mcm1-5). These include donor preference defects and altered chromatin structure (Fig. 3 and 4). In addition, we found that the binding of yKu80p to the RE requires an intact Mcm1 binding site (Fig. 2). These lines of evidence collectively suggest that yKu80p may function through Mcm1p to regulate mating type switching in MATa cells.

RE has been shown to be regulated with a built-in redundancy. The requirement of the Mcm1p binding site in C domain can be compensated with tandem repeats of the A, D, and E regions (26). Since yKu80p's function at RE mostly depends on Mcm1p, we speculate that any combination of the RE conserved regions that can bypass the requirement of Mcm1p would also have the same effect on yKu80p.

yKu80p has been shown to be a DNA end binding protein (23). The ring-like crystal structure of the yKu80p/yKu70p heterodimer further supports its nonspecific end binding activity (29). However, it has also been shown to be able to bind double-stranded DNA, replication origins, and hairpin structures (10, 23). In this study, we showed that yKu80p is associated with an internal DNA sequence (RE). This distinguishes it from previous known character of yKu80p regulating end-DNA processes such as DNA repair and telomere silencing. The interaction could be via a sequence-specific transcription factor (Mcm1p). Also we cannot rule out the possible involvement of the unique RE sequence, the a-cell-specific chromatin structure of the region, or the noncoding RNAs being transcribed in RE (27, 31, 32).

One current hypothesis is that interactions of RE with proteins such as Mcm1p, yKu80p, and Fkh1,2p, may help to release the left arm of chromosome III including the HML from the heterochromatic nuclear periphery and make it accessible for recombination. Moreover, RE may also serve as an entry point for the DSB and regulate the donor preference by assisting homology searching and recombination. Thus, proteins that are associated with RE, such as yKu80p and the forkhead proteins, may promote this process by interacting with proteins that bind to the DSB and lead it to scan for the homologous sequence in the HML. The directional and transient interactions of the yKu80p and the left arm of chromosome III, as shown in Fig. 5, agreed with this model.

Future detailed mechanistic studies will not only help us understand RE functions during switching, but more importantly, also shed light on how a small cis-acting element can control homologous recombination and chromatin structure over a large chromosome segment. The implications of these results for similar situations in the genomes of other organisms, e.g., immunoglobulin switching in humans, are obvious (3, 18).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge J. Haber and S. Ercan for providing yeast strains. We are grateful to C. Ducker for initial help on the minichromosome purification procedure. All members of the Simpson lab, Workman lab, and the Penn State gene regulation group are thanked for instructive advice and discussion.

These studies were funded by grant R01 GM-52908 to R.T.S from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the Stowers Institute.

Footnotes

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Robert T. Simpson, a trusted colleague and thoughtful mentor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bi, X., and J. R. Broach. 1999. UASrpg can function as a heterochromatin boundary element in yeast. Genes Dev. 13:1089-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brachmann, R. K., K. Yu, Y. Eby, N. P. Pavletich, and J. D. Boeke. 1998. Genetic selection of intragenic suppressor mutations that reverse the effect of common p53 cancer mutations. EMBO J. 17:1847-1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casellas, R., A. Nussenzweig, R. Wuerffel, R. Pelanda, A. Reichlin, H. Suh, X. F. Qin, E. Besmer, A. Kenter, K. Rajewsky, and M. C. Nussenzweig. 1998. Ku80 is required for immunoglobulin isotype switching. EMBO J. 17:2404-2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cervelli, T., and A. Galli. 2000. Effects of HDF1 (Ku70) and HDF2 (Ku80) on spontaneous and DNA damage-induced intrachromosomal recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264:56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervelli, T., and A. Galli. 2000. Effects of HDF1 (Ku70) and HDF2 (Ku80) on spontaneous and DNA damage-induced intrachromosomal recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264:56-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clikeman, J. A., G. J. Khalsa, S. L. Barton, and J. A. Nickoloff. 2001. Homologous recombinational repair of double-strand breaks in yeast is enhanced by MAT heterozygosity through yKU-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Genetics 157:579-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosgrove, A. J., C. A. Nieduszynski, and A. D. Donaldson. 2002. Ku complex controls the replication time of DNA in telomere regions. Genes Dev. 16:2485-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean, A., D. S. Pederson, and R. T. Simpson. 1989. Isolation of yeast plasmid chromatin. Methods Enzymol. 170:26-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ducker, C. E., and R. T. Simpson. 2000. The organized chromatin domain of the repressed yeast a cell-specific gene STE6 contains two molecules of the corepressor Tup1p per nucleosome. EMBO J. 19:400-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldmann, H., L. Driller, B. Meier, G. Mages, J. Kellermann, and E. L. Winnacker. 1996. HDF2, the second subunit of the Ku homologue from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27765-27769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank-Vaillant, M., and S. Marcand. 2002. Transient stability of DNA ends allows nonhomologous end joining to precede homologous recombination. Mol. Cell 10:1189-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotta, M., and S. M. Gasser. 1996. Nuclear organization and transcriptional silencing in yeast. Experientia 52:1136-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haber, J. E. 1998. Mating-type gene switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32:561-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laroche, T., S. G. Martin, M. Gotta, H. C. Gorham, F. E. Pryde, E. J. Louis, and S. M. Gasser. 1998. Mutation of yeast Ku genes disrupts the subnuclear organization of telomeres. Curr. Biol. 8:653-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, B., and J. C. Reese. 2001. Ssn6-Tup1 regulates RNR3 by positioning nucleosomes and affecting the chromatin structure at the upstream repression sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 276:33788-33797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie 3rd, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mages, G. J., H. M. Feldmann, and E. L. Winnacker. 1996. Involvement of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae HDF1 gene in DNA double-strand break repair and recombination. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7910-7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manis, J. P., Y. Gu, R. Lansford, E. Sonoda, R. Ferrini, L. Davidson, K. Rajewsky, and F. W. Alt. 1998. Ku70 is required for late B cell development and immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching. J. Exp. Med. 187:2081-2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin, S. G., T. Laroche, N. Suka, M. Grunstein, and S. M. Gasser. 1999. Relocalization of telomeric Ku and SIR proteins in response to DNA strand breaks in yeast. Cell 97:621-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morse, R. H., D. S. Pederson, A. Dean, and R. T. Simpson. 1987. Yeast nucleosomes allow thermal untwisting of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:10311-10330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasmyth, K. 1983. Molecular analysis of a cell lineage. Nature 302:670-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth, S. Y., A. Dean, and R. T. Simpson. 1990. Yeast alpha 2 repressor positions nucleosomes in TRP1/ARS1 chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:2247-2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shakibai, N., V. Kumar, and S. Eisenberg. 1996. The Ku-like protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required in vitro for the assembly of a stable multiprotein complex at a eukaryotic origin of replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11569-11574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimizu, M., S. Y. Roth, C. Szent-Gyorgyi, and R. T. Simpson. 1991. Nucleosomes are positioned with base pair precision adjacent to the alpha 2 operator in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 10:3033-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson, R. T. 1990. Nucleosome positioning can affect the function of a cis-acting DNA element in vivo. Nature 343:387-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun, K., E. Coic, Z. Zhou, P. Durrens, and J. E. Haber. 2002. Saccharomyces forkhead protein Fkh1 regulates donor preference during mating-type switching through the recombination enhancer. Genes Dev. 16:2085-2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szeto, L., M. K. Fafalios, H. Zhong, A. K. Vershon, and J. R. Broach. 1997. Alpha2p controls donor preference during mating type interconversion in yeast by inactivating a recombinational enhancer of chromosome III. Genes Dev. 11:1899-1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura, K., Y. Adachi, K. Chiba, K. Oguchi, and H. Takahashi. 2002. Identification of Ku70 and Ku80 homologues in Arabidopsis thaliana: evidence for a role in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Plant J. 29:771-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker, J. R., R. A. Corpina, and J. Goldberg. 2001. Structure of the Ku heterodimer bound to DNA and its implications for double-strand break repair. Nature 412:607-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiler, K. S., L. Szeto, and J. R. Broach. 1995. Mutations affecting donor preference during mating type interconversion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 139:1495-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss, K., and R. T. Simpson. 1997. Cell type-specific chromatin organization of the region that governs directionality of yeast mating type switching. EMBO J. 16:4352-4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu, C., K. Weiss, C. Yang, M. A. Harris, B. K. Tye, C. S. Newlon, R. T. Simpson, and J. E. Haber. 1998. Mcm1 regulates donor preference controlled by the recombination enhancer in Saccharomyces mating-type switching. Genes Dev. 12:1726-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu, X., and J. E. Haber. 1996. A 700 bp cis-acting region controls mating-type dependent recombination along the entire left arm of yeast chromosome III. Cell 87:277-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu, X., and J. E. Haber. 1995. MATa donor preference in yeast mating-type switching: activation of a large chromosomal region for recombination. Genes Dev. 9:1922-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu, X., J. K. Moore, and J. E. Haber. 1996. Mechanism of MATα donor preference during mating type switching of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:657-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]