Abstract

Microbial pathogens have evolved diverse strategies to modulate the host cell cytoskeleton to achieve a productive infection and have proven instrumental for unraveling the molecular machinery that regulates actin polymerization. Here we uncover a mechanism for Shigella flexneri-induced actin comet tail elongation that links Abl family kinases to N-WASP-dependent actin polymerization. We show that the Abl kinases are required for Shigella actin comet tail formation, maximal intracellular motility, and cell-to-cell spread. Abl phosphorylates N-WASP, a host cell protein required for actin comet tail formation, and mutation of the Abl phosphorylation sites on N-WASP impairs comet tail elongation. Furthermore, we show that defective comet tail formation in cells lacking Abl kinases is rescued by activated forms of N-WASP. These data demonstrate for the first time that the Abl kinases play a role in the intracellular motility and intercellular dissemination of Shigella and uncover a new role for Abl kinases in the regulation of pathogen motility.

Pathogens such as Shigella flexneri have emerged as powerful tools for dissecting the mechanisms that regulate actin polymerization and cytoskeletal rearrangements in mammalian cells. Shigella is a gram-negative bacterium that is the infectious agent responsible for shigellosis, a diarrheal disease that afflicts over 150 million people worldwide each year (20). Shigella invades the epithelial cells lining the colon and establishes a persistent infection based on its unique ability to spread from cell to cell without reentering the lumen of the gut. The ability of Shigella to invade and disseminate throughout the colon depends on the subversion of host cell signaling pathways that regulate cytoskeletal dynamics. The initial entry of Shigella into the colonic epithelium is mediated by activation of the Rho family GTPases, which stimulate the formation of filopodia and lamellipodia which surround the bacterium and allow for its engulfment into the cell. Once the bacteria have been internalized, they are released from their entry vesicles and form long actin comet tails, which are used to propel the bacteria throughout the cytoplasm. The force generated by the Shigella-dependent actin comet tails facilitates the formation of membrane protrusions into neighboring cells, which allows for engulfment and intercellular dissemination of the bacteria (40).

Host cell tyrosine kinases play important roles during bacterial entry. The Src family kinases have been shown to have dual roles during internalization: they promote bacterial uptake by facilitating actin focus formation at the site of bacterial entry and also down-regulate the cytoskeletal machinery following engulfment through the activation of Rho (49). The Abl tyrosine kinases, comprising family members Abl and Arg, are also required for Shigella internalization (5). Cells doubly null for Abl and Arg are deficient in bacterial uptake, as are cells treated with the Abl kinase inhibitor STI571 (Gleevec). Abl and Arg are catalytically activated upon Shigella infection, and the active kinases phosphorylate a specific tyrosine residue on the adapter protein Crk. Phosphorylation of Crk by the Abl kinases is required in part for activation of the Rho GTPases Rac and Cdc42 and efficient Shigella uptake.

Following internalization into the colonic epithelium, Shigella lyses the vacuolar membrane and induces localized actin polymerization leading to the formation of actin comet tails that propel the bacteria and allow for intracellular motility. This process requires the Shigella IcsA protein and the host cell protein N-WASP (3). While N-WASP is not required for Shigella uptake into mammalian cells, formation of actin comet tails and intracellular movement of Shigella are absolutely dependent on N-WASP, as both processes are abrogated in fibroblasts derived from N-WASP knockout mice (24, 44). Direct binding of IcsA to N-WASP unfolds the inactive (closed) conformation of N-WASP, leading to the recruitment of the Arp2/3 complex to the VCA domain of N-WASP and the subsequent stimulation of actin nucleation by Arp2/3 (11). IcsA mimics activated Cdc42 in its ability to bind and activate N-WASP, and thus IcsA-mediated N-WASP activation bypasses the requirement for Cdc42 in N-WASP activation. Indeed, the Rho family GTPases are not required for Shigella intracellular motility, as comet tail formation is unaffected in Cdc42-deficient cells (42) and in cells treated with toxins that inactivate multiple Rho family GTPases (29). Little is known regarding the identity of host cell factors involved in the activation of N-WASP-dependent actin polymerization. Potential candidates are tyrosine kinases, as tyrosine phosphorylation has been shown to regulate the activity of WASP family proteins in vitro and during filopodium formation, neurite extension, and cell migration (8, 45, 54). WASP and N-WASP are phosphorylated by the Src family kinases, focal adhesion kinase and Btk, and phosphorylation of Y256 in N-WASP (Y291 in WASP) results in enhanced actin polymerization via the Arp2/3 complex in vitro (48). Tyrosine 256 lies within the GTPase-binding domain (GBD) of N-WASP, which is inaccessible to protein kinases in the N-WASP folded (inactive) conformation (22). Binding of activators such as Grb2 or activated Cdc42 opens up the N-WASP structure and allows for phosphorylation of Y256 by various tyrosine kinases. Phosphorylation of Y256 provides a site for recruiting SH2-containing proteins, which is believed to stabilize Arp2/3 binding and sustain actin polymerization (48). Thus, tyrosine phosphorylation has the potential to couple upstream signaling pathways to N-WASP activation and might regulate the duration and amplitude of N-WASP-dependent actin polymerization via Arp2/3.

Based on these findings and our previous observations that the Abl tyrosine kinases are required for bacterial uptake, we sought to determine whether they might also regulate Shigella intracellular motility and intercellular dissemination. Using cells lacking Abl kinase activity, we have shown for the first time that Abl and Arg are required for efficient comet tail formation, intracellular motility, and cell-to-cell spread of Shigella. Furthermore, we show that N-WASP is a substrate for the Abl kinases and that phosphorylation at tyrosine 256 of N-WASP regulates its ability to mediate comet tail formation. These findings uncover a novel role for Abl family kinases in the regulation of Shigella motility, which may be extended to other pathogens that subvert the host cell actin polymerization machinery to move inside and between cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and reagents.

The wild-type strain Shigella flexneri 2457T was a generous gift from Marcia Goldberg (Harvard University). The 2457T strain was transformed with a bacterial green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression plasmid, provided by Alejandro Aballay (Duke University). Shigella was grown on tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco) agar plates containing 0.5% Congo Red. Overnight cultures were grown in TSB, diluted 1:100, and grown to mid-logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm ∼ 0.3) for infection of cell monolayers, as previously described (5).

Cell cultures and reagents.

Abl/Arg-null mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) have been previously described (5, 34). Caco2 cells were obtained from the Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center Cell Culture Facility and were maintained in minimal essential medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen). 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS. Sf9 cells were maintained in Grace's media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated serum (Invitrogen). The N-WASP−/− (clone 1H51) and flox/flox (clone 1) cell lines were kindly provided by Juergen Wehland (German Research Centre for Biotechnology, Braunschweig, Germany) (24) and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% l-glutamine (Invitrogen). STI571 was a generous gift from Brian Druker (Oregon Health Sciences University). SU6656 was purchased from Calbiochem.

Plasmid DNA constructs.

The bovine N-WASP cDNA (pcDL-SRα-N-WASP) was a generous gift from Hiroaki Miki (University of Tokyo) (25). The N-WASP sequence was subcloned into the pFLAG-CMV2 vector (Sigma) and the pLEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech) to produce FLAG-N-WASP and GFP-N-WASP fusion constructs. Point mutations were created using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The N-WASP cDNA was also subcloned into the pFastBas-HTc vector for production of baculovirus using the Bac-to-Bac expression system (Invitrogen). The Cdc42 (pCan-Cdc42-V12) and FLAG-WASP (pyDF30-WASP) cDNAs were a generous gift from Arie Abo (Onyx Pharmaceuticals). The GFP-WAVE construct (pEGFP-WAVE) was kindly provided by John Scott (Oregon Health Sciences University) (53). The pcDNA-cAbl-1q2q3q, pcDNA-cAbl-1q2q3q-K290M (52), and pcDNA-Abl-P131L (51) constructs were a generous gift from Richard Van Etten. pCGN-Grb2 was described previously (13).

Expression and purification of recombinant N-WASP.

The Fast-Bac-HTc-N-WASP construct was transformed into DH10Bac competent cells, and isolated bacmid DNA was used to transfect Sf9 insect cells for baculovirus production. Infected Sf9 cells were disrupted with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.5], 100 mM KCl, 1% NP-40, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and protease inhibitors), and the histidine-tagged N-WASP was purified using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid) agarose (QIAGEN). The bound proteins were incubated with wash buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8.5], 500 mM KCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol) to prevent nonspecific binding to the beads and released from the beads using elution buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The eluted proteins were dialyzed in storage buffer (20 mM MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; pH 7.0], 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol) and stored at −80°C in 50% glycerol.

Identification of N-WASP phosphorylation sites by mass spectrometry.

293T cells were transfected with FLAG-N-WASP, pCGN-Grb2, and pcDNA-c4-Abl-1q2q3q. N-WASP was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysate with anti-FLAG antisera, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and visualized by staining with Coomassie. The band corresponding to N-WASP was isolated and analyzed as previously described (34). Briefly, the sequence analysis was performed at the Harvard Microchemistry Facility by microcapillary reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography nanoelectrospray tandem mass spectrometry on a Finnegan (San Jose, CA) LCQ DECA quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer.

Plaque assay.

The plaque assay to quantify bacterial dissemination was performed as previously described (30). Briefly, cells were plated in a confluent monolayer in six-well dishes and infected with Shigella at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI; 0.01). Following a 90-minute invasion incubation, the infection medium was removed and replaced with complete medium containing 50 μg/ml gentamicin. In the Caco2 plaque assays, the gentamicin medium also contained 0, 10, or 30 μM STI571. The monolayers were cultured in a 37°C incubator for 24 to 48 h. To visualize the plaques, the cell monolayers were carefully washed with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with methanol, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Individual plaques were photographed using a 2.5× or 5× objective on a Zeiss Telaval 31 light microscope.

Visualization of Shigella comet tails.

Cell monolayers were infected with Shigella as previously described (24, 42). Following fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, the cells were permeabilized and stained with anti-Shigella antisera (Maine Biotechnology Services, Inc.), rhodamine phalloidin (Molecular Probes), and anti-GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), when necessary. Comet tails were visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy and quantified as previously described (5, 42). The comet tail lengths were quantified using Metamorph software, and the medians were calculated and plotted using GraphPad software. The comet tail lengths were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test, as previously described (42).

Quantification of bacterial velocity.

The protocol for time-lapse microscopy and quantification of bacterial velocity was designed based on previous reports (27, 28). Cells were plated on 35-mm cover glass bottom dishes (Mat-Tek), infected with GFP-expressing Shigella as previously described (24, 42), and maintained on the microscope in a 37°C chamber with humidified 5% CO2. Cells containing intracellular bacteria were observed from 3 to 8 h following infection, and dual differential interference contrast/fluorescence images were captured every 10 seconds, with 50-millisecond exposures, for 15 min, using the lowest possible illumination intensity in order to minimize photo damage, consistent with good imaging. The tracking feature within Metamorph software was used to calculate the velocity of motile bacteria (nonmotile bacteria were excluded from the analysis). The average velocity was calculated from sets of 10 or more consecutive time points during which bacteria displayed uninterrupted motility.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed as previously described (5) using the following antisera: anti-myc (9E10), anti-hemagglutinin (HA), anti-GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), antiphosphotyrosine (4G10; Upstate Biotechnology), anti-FLAG, anti-β-tubulin (Sigma), anti-Crk (BD Transduction Labs), anti-phospho-Crk-Y221 (Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Abl (8E9; Calbiochem).

RESULTS

Abl tyrosine kinases regulate actin comet tail elongation.

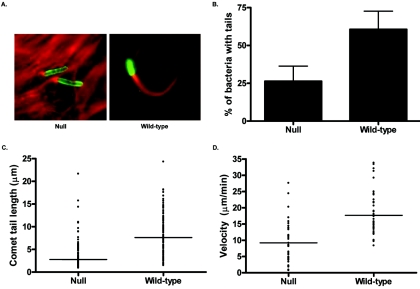

To examine whether Abl family kinases regulate actin polymerization during comet tail formation induced by intracellular Shigella, we employed fibroblasts derived from wild-type and Abl/Arg-null mice. As shown in Fig. 1, Shigella-induced comet tail formation is severely impaired in MEFs null for Abl/Arg compared to wild-type controls. Intracellular bacteria in MEFs lacking Abl and Arg had fewer comet tails (27%) compared to wild-type MEFs (61%) (Fig. 1B). Of those intracellular bacteria that displayed comet tails, Shigella actin tails were significantly shorter in the Abl/Arg-null cells (2.8 ± 0.5 μm) than those in the wild-type MEFs (7.7 ± 1.3 μm) (Fig. 1C). Reconstitution of Abl and Arg expression restores the ability of the Null cells to form comet tails comparable in length to those in the wild-type MEFs (8.3 ± 1.4 μm) (see Fig. 5B). To determine whether the observed decrease in comet tail length corresponded to decreased actin polymerization at the bacterial surface (47), we calculated the velocity of bacteria in cells either lacking (null) or expressing (wild type) Abl and Arg. Indeed, we observed a 48% decrease in bacterial velocity in the null cells (9.19 ± 0.97 μm/min) compared to the cells expressing the Abl kinases (17.66 ± 1.09 μm/min) (Fig. 1D). These observations suggest that Abl kinases mediate actin polymerization during Shigella comet tail elongation.

FIG. 1.

Abl kinases are required for efficient Shigella-induced actin comet tail formation. (A) Wild-type or Abl/Arg-null mouse embryo fibroblasts were infected with Shigella flexneri 2457T at 37°C for 1 hour and further incubated with medium containing gentamicin for 45 min to remove extracellular bacteria. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and immunostained with anti-Shigella antisera (green) and phalloidin (red) and visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. (B) Twenty 63× fields were analyzed, and the percentage of total intracellular bacteria with visible actin comet tails was quantified. Results shown are from three independent experiments. The difference was shown to be statistically significant (P = 0.0385). (C) Comet tail lengths were quantified using Metamorph software and plotted for each cell type. The lines denote the median comet tail length for each cell type. Results shown are from three independent experiments. The comet tail lengths were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test, and the differences were shown to be statistically significant (P < 0.0001). (D) Bacterial velocity was quantified using Metamorph software and plotted for each cell type. The lines denote the average velocity for each cell type. The velocities were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test and the differences were shown to be statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

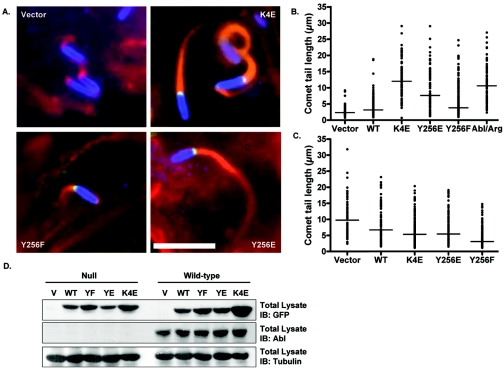

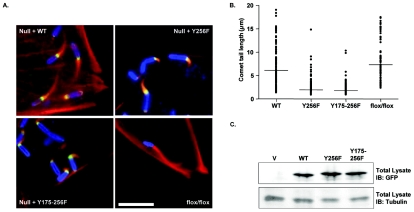

FIG. 5.

Activated N-WASP restores Shigella-induced actin comet tail formation in cells lacking Abl kinases. (A) Abl/Arg-null MEFs were reconstituted with either vector or GFP-tagged N-WASP (K4E, Y256E, or Y256F, as noted) and were infected with Shigella flexneri 2457T at 37°C for 1 hour and further incubated with medium containing gentamicin for 45 min to remove extracellular bacteria. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and immunostained with anti-Shigella antisera (blue), anti-GFP antisera (green), and phalloidin (red) and visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. (B) Quantification of comet tail lengths in Abl/Arg-null MEFs expressing vector, GFP-N-WASP (WT, K4E, Y256E, Y256F), or Abl and Arg. Comet tail lengths were quantified using Metamorph software and plotted for each cell type. The line denotes the median comet tail length for each cell type. Results shown are from three independent experiments. The comet tail lengths were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. (C) Vector or GFP-N-WASP (wild type, K4E, Y256E, or Y256F, as noted) was introduced into wild-type mouse embryo fibroblasts and analyzed as in panel B. (D) Equivalent amounts of cell lysate were examined by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-GFP (upper panel), anti-Abl (middle panel), or anti-β-tubulin (lower panel) antisera.

Abl kinases phosphorylate N-WASP.

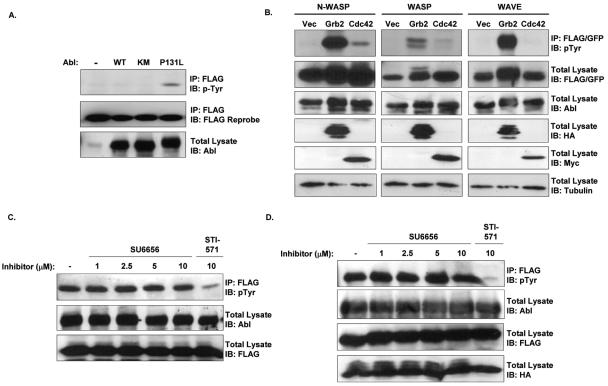

During Shigella uptake, the Abl kinases phosphorylate the adapter protein Crk, leading to activation of the Rho family GTPases Rac and Cdc42 (5). However, the Rho GTPases are not required for Shigella comet tail formation (29, 42), suggesting that the Abl kinases regulate a distinct signaling pathway during this process. Shigella intracellular motility is regulated by IcsA, an effector protein present on the surface of the bacteria at one polar end of the bacterial body (14). IcsA binds to and activates N-WASP, which is absolutely required for comet tail formation (11, 24, 44). N-WASP activity can be modulated by phosphorylation (7, 8). As Abl kinases are activated in response to Shigella infection, we hypothesized that Abl kinases might phosphorylate N-WASP, resulting in stabilization of N-WASP activity and formation of full-length actin comet tails. To examine this hypothesis, we coexpressed epitope-tagged N-WASP with wild-type, kinase-inactive, or constitutively active Abl (P131L) and examined the phosphorylation state of immunoprecipitated N-WASP by antiphosphotyrosine immunoblotting. N-WASP was tyrosine phosphorylated upon coexpression with constitutively active Abl, though not with wild-type or kinase-dead Abl (Fig. 2A). Previous analyses of WASP protein family phosphorylation suggested that access to phosphorylation sites might be enhanced when N-WASP is relieved from its autoinhibited conformation (8, 45, 48). To examine this possibility, we expressed wild-type Abl with WASP, N-WASP, or WAVE and one of two activators of N-WASP: activated Cdc42 (Cdc42-V12) or Grb2. Both Cdc42-V12 and Grb2 have been shown to activate N-WASP, allowing it to interact with the Arp2/3 complex and initiate actin polymerization (6, 26). Phosphorylation of N-WASP by wild-type Abl was greatly enhanced upon coexpression of either Cdc42-V12 or Grb2 (Fig. 2B), suggesting that Abl preferentially phosphorylates N-WASP in its active conformation. Phosphorylation of both WASP and WAVE was also markedly stimulated in the presence of Grb2 (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Abl phosphorylates the open conformation of N-WASP. (A) 293T cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding FLAG-N-WASP with either wild-type (WT), kinase-inactive (KM), or constitutively active (P131L) Abl. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG and immunoblotted for phosphotyrosine (upper panel) or the FLAG epitope (middle panel). Total lysates were immunoblotted with anti-Abl antisera (lower panel) (B) 293T cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding FLAG-N-WASP, FLAG-WASP, or GFP-WAVE, in the presence of wild-type Abl and either vector (Vec), HA-Grb2 (Grb2), or Myc-Cdc42-V12 (Cdc42). N-WASP, WASP, and WAVE were immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell lysates and analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine antisera (upper panels). Equivalent amounts of cell lysate were examined by immunoblotting (IB) for anti-FLAG (for N-WASP and WASP), anti-GFP (for WAVE), anti-Abl, anti-HA (for Grb2), anti-Myc (for Cdc42), or β-tubulin (lower panels, as noted). (C) 293T cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding FLAG-N-WASP and constitutively active Abl (Abl-PP). Prior to lysis, the cells were incubated with either SU6656 (1 to 10 μM, as noted) or STI571 (10 μM) for 16 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antisera and analyzed by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antisera. Equivalent amounts of cell lysate were immunoblotted with anti-Abl (middle panel) or anti-FLAG (lower panel) antisera. (D) 293T cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding FLAG-N-WASP, wild-type Abl, and HA-Grb2. Prior to lysis, the cells were incubated with either SU6656 (1 to 10 μM, as noted) or STI571 (10 μM) for 16 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antisera and analyzed by immunoblotting with antiphosphotyrosine antisera. Equivalent amounts of cell lysate were immunoblotted with anti-Abl, anti-FLAG, or anti-HA (lower panels, as noted).

WASP family proteins have previously been shown to be substrates for the Src family kinases (8, 45, 48). We considered that the Src family kinases might be activated downstream of Abl and that the N-WASP phosphorylation we observed could be Src mediated. To examine this possibility, we treated cells with the Src kinase inhibitor SU6656 at concentrations up to 10-fold higher than required for inhibition of Src kinase activity and examined N-WASP phosphorylation. Tyrosine phosphorylation of N-WASP in cells expressing activated Abl (Fig. 2C) or coexpressing wild-type Abl and Grb2 (Fig. 2D) remained constant in the presence of increasing concentrations of SU6656 but was ablated in cells treated with the Abl kinase inhibitor STI571. This finding demonstrates that the Abl kinases phosphorylate N-WASP independently of the Src kinases.

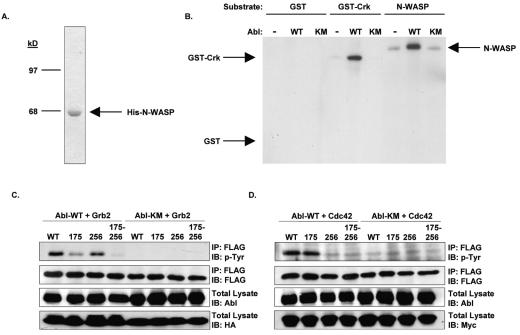

Next, we examined whether Abl could phosphorylate N-WASP in vitro. We generated a baculovirus encoding full-length N-WASP and purified the protein following infection of insect cells (Fig. 3A). The purified N-WASP protein was then used as a substrate in an in vitro kinase assay with immunoprecipitated endogenous Abl, or overexpressed wild-type or kinase-inactive Abl. Wild-type, but not kinase-inactive, Abl phosphorylated N-WASP in vitro (Fig. 3B). Thus, Abl can directly phosphorylate full-length N-WASP.

FIG. 3.

Abl phosphorylates N-WASP on tyrosines 175 and 256. (A) Histidine-tagged N-WASP was expressed in Sf9 insect cells and purified with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose. The purified protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie. (B) 293T cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding either vector (−), the wild-type Abl (WT) or a kinase-inactive Abl mutant (KM). Abl was immunoprecipitated and used in an in vitro kinase assay with 0.25 μg substrate (glutathione S-transferase [GST]-Crk or N-WASP). The reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. The arrows denote the mobility of each of the substrates, as determined by Coomassie staining of the gel. (C and D) 293T cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding either wild-type N-WASP (WT) or N-WASP mutant Y175F (175), Y256F (256), or Y175-256F (175-256) in the presence of wild-type Abl and either HA-Grb2 (C) or Myc-Cdc42-V12 (D). The cells were harvested 48 h after transfection by incubation in lysis buffer. Equal amounts of lysate were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antisera. The immune complexes and total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine antisera. The expression levels of N-WASP, Abl, Grb2, and Cdc42-V12 were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with FLAG, Abl, HA, or Myc antisera, respectively.

In order to examine the effect of Abl phosphorylation upon N-WASP function, we mapped the in vivo phosphorylation sites on N-WASP by mass spectrometry as previously described (34). Two tyrosine phosphorylation sites within the bovine N-WASP sequence were identified using this method: tyrosines 175 and 256. Phosphorylation of N-WASP on tyrosine 256 (tyrosine 291 in WASP) by Src kinases has been shown to stabilize the active conformation (8, 45, 48). The tyrosine residue at position 175 had not been previously identified as a phosphorylation site on WASP or N-WASP and thus is a novel site of tyrosine phosphorylation. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we generated single and double point mutations within N-WASP that replaced tyrosines 175 and 256 with phenylalanine. N-WASP mutants were coexpressed with wild-type Abl and either Cdc42-V12 or Grb2 and were analyzed by antiphosphotyrosine immunoblotting. Mutation of tyrosine 256 alone to phenylalanine abolished tyrosine phosphorylation of N-WASP by wild-type Abl in the presence of activated Cdc42 (Fig. 3D). In contrast, mutation of both tyrosines 175 and 256 to phenylalanine was required to abolish Abl-mediated phosphorylation of N-WASP in the presence of Grb2 (Fig. 3C). These observations suggest that the binding of different activators of N-WASP impacts the availability of distinct tyrosines for phosphorylation by Abl kinases and may have variable effects on N-WASP function.

Phosphorylation at tyrosine 256 of N-WASP is required for elongation of Shigella actin comet tails.

In order to determine the effect of Abl phosphorylation on N-WASP function, we examined the induction of Shigella comet tail formation by the N-WASP tyrosine-to-phenylalanine mutants. We took advantage of the finding that comet tail formation is completely abrogated in cells lacking N-WASP (24). Wild-type or tyrosine-to-phenylalanine mutants of N-WASP were introduced into the N-WASP−/− cells, and the corresponding proteins were expressed to equivalent levels (Fig. 4C). The cells were then infected with Shigella, and the lengths of the comet tails induced by the bacteria were measured (Fig. 4A and B). As expected, cells expressing GFP alone exhibited no comet tails (data not shown) (24). Expression of wild-type N-WASP fully restored the ability of the null cells to form comet tails, which were similar to those exhibited by N-WASP flox/flox MEFs (Fig. 4A). The N-WASP mutants Y256F or Y175-256F induced the formation of abnormal comet tails with significantly reduced lengths (1.9 ± 0.1 μm and 1.9 ± 0.2 μm, respectively) compared to cells expressing wild-type N-WASP (5.7 ± 1.2 μm) or N-WASP flox/flox MEFs (7.5 ± 0.2 μm) (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, mutation of tyrosine 175 to phenylalanine in the Y175-256F mutant did not further reduce the length of the comet tail compared to the Y256F single mutant, suggesting that phosphorylation at tyrosine 175 is not critical for comet tail formation by Shigella. Thus, these findings suggest that phosphorylation at tyrosine 256 is critical for efficient comet tail elongation by intracellular Shigella.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation of N-WASP at tyrosine 256 is required for efficient Shigella-induced actin comet tail formation. (A) N-WASP−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts reconstituted with either wild-type GFP-N-WASP (upper left panel), GFP-N-WASP-Y256F (upper right panel), or GFP-N-WASP-Y175-256F (lower left panel) were infected with Shigella flexneri 2457T at 37°C for 1 hour and further incubated with media containing gentamicin for 45 min to remove extracellular bacteria. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and immunostained with anti-Shigella antisera (blue) and phalloidin (red) and visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. N-WASP flox/flox cells were analyzed for comparison (lower right panel). Bar, 10 μM. (B) Comet tail lengths were quantified using Metamorph software and plotted for each cell type. The line denotes the median comet tail length for each cell type. Results shown are from three independent experiments. The comet tail lengths were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test, and the differences in comet tail length were shown to be statistically significant (P < 0.0001 for the Y256F and Y175-256F mutants, compared to the wild type [WT]). (C) Equivalent amounts of cell lysate were examined by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-GFP (upper panel) or anti-β-tubulin (lower panel) antisera.

Next, we examined whether activated forms of N-WASP could restore comet tail formation in the MEFs lacking Abl and Arg. Upon Shigella infection, these cells exhibit shorter comet tails, compared to wild-type MEFs (Fig. 1). If N-WASP is a downstream target of the Abl kinases, a constitutively active form of N-WASP should allow for the formation of full-length comet tails in these cells. To test this prediction, we introduced two activated mutants of N-WASP into the Abl/Arg-null MEFs: K4E and Y256E. The K4E mutant contains point mutations within the basic region, changing four lysine residues to glutamic acid. This mutant has been previously shown to activate the Arp2/3 complex in the absence of activators such as GTP-bound Cdc42 (18). The Y256E mutant contains a point mutation changing the tyrosine at position 256 to a glutamic acid. This mutation creates a positive charge at this site, mimicking tyrosine phosphorylation at position 256 (8, 45). We introduced these mutants, as well as wild-type N-WASP and the Y256F mutant, into either wild-type MEFs or the Abl/Arg-null MEFs (Fig. 5D). The cells were then infected with Shigella, and the intracellular bacteria were analyzed for comet tail formation. Both the K4E and the Y256E mutants of N-WASP markedly increased the lengths of comet tails formed in Abl/Arg-null MEFs (Fig. 5A and B). The wild-type N-WASP and the Y256F mutant slightly increased comet tail length in the Abl/Arg-null MEFs, possibly due to an increase of N-WASP protein at the surface of the bacteria, as both proteins can bind to the Shigella IcsA protein to induce actin nucleation (Fig. 5B). However, the increase produced by the wild-type and Y256F mutant proteins was substantially less than that caused by the expression of the activated N-WASP proteins. As expected, neither the wild-type N-WASP nor the activated mutants increased comet tail length in wild-type MEFs (Fig. 5C). Indeed, expression of wild-type, K4E, and Y256E N-WASP proteins in wild-type cells caused a slight decrease in actin comet tail length, which may result from sequestration of the actin polymerization machinery by N-WASP proteins that accumulate at cytoplasmic sites other than the bacterial surface. The Y256F N-WASP mutant protein caused a further decrease in comet tail length in wild-type MEFs, suggesting it may function as a dominant negative in these cells. These data demonstrate that activated N-WASP can compensate for the loss of Abl and Arg with regard to comet tail formation and demonstrate that N-WASP is a downstream target of the Abl kinases during Shigella infection.

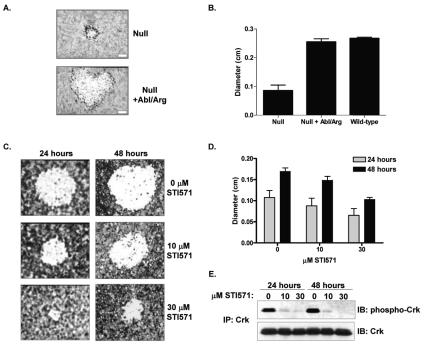

Abl kinases are required for Shigella cell-to-cell spread.

Because Abl family kinases are implicated in both bacterial uptake and Shigella-induced actin comet tail elongation, we next examined whether the Abl kinases were required for Shigella intercellular dissemination. Little is known regarding the mechanisms that regulate cell-to-cell spread of Shigella. Many of the Shigella effectors required for bacterial entry are also required for intercellular dissemination, suggesting that many of the same host cell signaling pathways are also involved (33, 38). Indeed, vinculin has been shown to regulate Shigella uptake and is also present at sites of membranous protrusions observed at the initiation of cell-to-cell spread (4, 21). Both myosin II and myosin light-chain kinase are required for formation of these protrusions into neighboring cells (37). Cadherins and connexin 26 are required for bacterial spread, suggesting that Shigella interacts with the proteins mediating cell-to-cell contacts (41, 50). Host cell proteins regulating actin polymerization are also required, including N-WASP and profilin (27). The requirement of these proteins for cell-to-cell spread has been linked to their role in actin comet tail formation, which is required for the generation of membrane protrusions into neighboring cells. We employed the MEFs from mice doubly null for Abl and Arg in the plaque assay to quantify cell-to-cell spread. The plaques produced by cells doubly null for Abl and Arg were on average 68% smaller (0.085 ± 0.014 cm) than wild-type MEFs (0.267 ± 0.005 cm) (Fig. 6B). Reintroduction of Abl and Arg into the null cells reconstituted plaque formation to wild-type levels (0.255 ± 0.008 cm) (Fig. 6A and B). Since the level of cell-to-cell spread might depend on the efficiency of bacterial uptake, we also examined Shigella dissemination in the presence of the Abl kinase inhibitor STI571. The advantage of using a pharmacological inhibitor to study cell-to-cell spread is that Shigella can be allowed to enter the cell monolayer in the absence of the Abl kinase inhibitor, so that addition of STI571 after bacterial uptake allows for analysis of Abl kinase inhibition only on cell-to-cell spread. To this end, we infected the human intestinal epithelial cell line Caco2 with Shigella for 90 min to allow for bacterial uptake and then incubated the cells in the absence or presence of STI571 for 24 to 48 h (Fig. 6C). Caco2 cells incubated with either 10 or 30 μM STI571 exhibited significantly smaller plaques than those produced in the absence of the inhibitor. Notably, cells cultured in the presence of 30 μM STI571 exhibited plaques that were 40% smaller than plaques produced by untreated cells (Fig. 6D). The decrease in plaque diameter correlated with the decreased level of Abl kinase activity in the presence of increasing concentrations of STI571 (Fig. 6E). It is notable that complete inactivation of endogenous Abl family kinases in Caco2 epithelial cells required treatment with 30 μM STI571 (Fig. 6E). Together, these data demonstrate that Abl kinase activity is required for efficient intercellular spread of Shigella.

FIG. 6.

Abl kinases are required for intercellular spread. (A) Cells either lacking (null) or reexpressing Abl and Arg (null +Abl/Arg) were infected with Shigella flexneri 2457T at a low MOI for 90 min and further incubated with medium containing gentamicin for 48 h. Plaques were visualized by staining with crystal violet. (B) The diameter of each plaque was quantified and is shown for each cell type. Quantified results are from three independent experiments. (C) Caco2 cells were infected with Shigella flexneri 2457T at a low MOI for 90 min and further incubated with medium containing gentamicin for either 24 or 48 h in the absence or presence of STI571 as indicated. Plaques were visualized by staining with crystal violet. (D) The diameter of each plaque was quantified and is shown for the 24-h (gray bars) and 48-h (black bars) time points. Results are from three independent experiments. (E) Cells infected as above were analyzed for Abl kinase activity by immunoprecipitation (IP) of Crk and immunoblotting (IB) with anti-phospho-Crk antisera (upper panel). The Western blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-Crk antisera (lower panel) to demonstrate equivalent Crk levels in the immunoprecipitates.

DISCUSSION

Shigella employs diverse strategies to subvert the host cell actin cytoskeleton in order to support distinct phases of its infection cycle. Entry of Shigella into nonphagocytic cells such as intestinal epithelial cells is mediated by induction of actin polymerization at the site of bacterial entry and formation of actin-driven membrane protrusions that engulf the bacteria by a macropinocytic process (3, 9). Our previous work had defined a role for the Abl tyrosine kinases in Shigella uptake. Here, we uncover a novel role for Abl kinases during Shigella intracellular motility and intercellular dissemination. We have shown that Abl/Arg-null MEFs are deficient in Shigella comet tail elongation and exhibit altered intracellular motility. This defect in comet tail formation is due to impaired phosphorylation of N-WASP in the Abl/Arg-null MEFs, resulting in submaximal activation of N-WASP. Reintroduction of constitutively active N-WASP into these cells restores their ability to form full-length comet tails, suggesting that the phosphorylation required for maximal N-WASP activity is mediated by the Abl tyrosine kinases. Several tyrosine kinases have been shown to phosphorylate WASP proteins, including Btk and the Src family kinases Lyn, Lck, and Fyn (2, 8, 17, 31, 32, 45). In addition, Abl was shown to phosphorylate an isolated GBD of WASP containing tyrosine 291 in vitro (48). However, these studies did not identify the tyrosine kinases that phosphorylate N-WASP in vivo. Treatment of cells with the Src-selective inhibitor PP2 produced inhibition of N-WASP tyrosine phosphorylation (45). However, PP2 also inhibits Abl and other tyrosine kinases (1, 46). Moreover, Src kinases have been shown to function both upstream and downstream of Abl kinases (19, 35, 36). Our findings that Abl kinases phosphorylate N-WASP directly in vitro and in vivo and that activated N-WASP-Y256E restores Shigella-induced comet tail formation in cells lacking Abl kinases support a model whereby the Abl kinases regulate N-WASP activity during comet tail formation. We propose that, following N-WASP activation by IcsA at the surface of the bacteria, tyrosine 256 is phosphorylated by the Abl kinases. Phosphorylation at this site stabilizes the active conformation of N-WASP, resulting in comet tail elongation. While the initiation of Shigella comet tail formation by IcsA and N-WASP has been firmly established, the role of host cell signaling proteins in comet tail elongation is poorly understood. Efficient comet tail formation and intracellular motility are mediated by a balance of branched actin polymerization mediated by N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex and capping of actin filament barbed ends (23). In this regard, cells lacking Eps8 exhibit fewer and shorter actin tails induced by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-phosphate (PIP2) production, which is attributed to the lack of Eps8-mediated capping of the barbed-ends of actin filaments (10). Based on our findings, it is possible that Abl family kinases similarly regulate PIP2-dependent actin comet tail formation, which is important for vesicular movement (39).

Detection of N-WASP tyrosine phosphorylation during comet tail formation in vivo has proven to be difficult. This is consistent with previous observations that phosphorylation of WASP following cell surface receptor stimulation was detectable only following pervanadate treatment (2) and that there was a lack of detectable phosphotyrosine on motile Shigella (unpublished observations; 12). These observations suggest that N-WASP phosphorylation may be transient, due to the activity of cellular protein tyrosine phosphatases. Alternatively, the phosphorylation of N-WASP at tyrosine 256 may be masked in vivo by binding to SH2 domain-containing proteins. Indeed, the Src SH2 domain interacts with WASP that has been phosphorylated at tyrosine 291. This binding may serve to inhibit the intramolecular interaction between the GBD and the VCA domain of WASP, stabilizing the active conformation (48).

Intracellular motility of Shigella is required for the formation of protrusions into neighboring cells and subsequent cell-to-cell spread. This notion is supported by the requirement of N-WASP for Shigella intercellular dissemination (27). The Abl kinases are clearly required for Shigella cell-to-cell spread, though the mechanism of their action during this process is unclear. Reduced formation of Shigella-induced actin comet tails in cells lacking Abl kinase activity suggests that the ability of Shigella to protrude into neighboring cells might also be reduced. Abl may also have effects on other host cell proteins required for intercellular spread. Previous work has shown that cells lacking cadherin expression are defective in cell-to-cell spread and that this can be rescued by expression of either L-CAM (the chicken homologue of E-cadherin) or N-cadherin (41). Genetic studies have shown an interaction between Drosophila Abl kinases and DE-cadherin and have suggested a role for Abl in adherens junction stability (15, 16). It is possible that Abl interacts functionally with the cadherins during Shigella infection and facilitates the localization of the bacteria at the adherens junction or promotes the formation of the bacterial protrusion at these sites. During bacterial uptake, the Abl kinases regulate the activation of the Rho GTPases Cdc42 and Rac (5). The Rho GTPases have been shown to be dispensable for intracellular motility (29, 42), but their role in intercellular spread has not been examined. Cadherin engagement leads to activation of Rac, and Rac has been shown to be activated downstream of Abl kinases (5, 43). These findings suggest that Rac and Cdc42 may function downstream of Abl kinases during cell-to-cell spread.

Our findings have uncovered a role for Abl family kinases in three distinct stages of Shigella infection: uptake, intracellular motility, and cell-to-cell spread. These data provide further support to the notion that inhibition of host cell signaling proteins represents a novel strategy to treat antibiotic-resistant Shigella infections. Inhibition of the Abl kinases by a pharmacological inhibitor, such as STI571, would inhibit both bacterial uptake and the dissemination of the infection throughout the gut. This exciting possibility remains to be tested. Notably, our findings have revealed a novel role for Abl kinases in the modulation of actin comet tail formation by Shigella that may be shared with other pathogens and cellular processes that employ WASP/Scar/WAVE family proteins to facilitate intracellular motility.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jürgen Wehland, Theresia Stradal, and Klemens Rottner for the gift of reagents and comments on the manuscript; Julie Theriot for technical advice regarding the bacterial velocity experiments; Alejandro Aballay for reagents; William S. Lane and the Harvard Microchemistry Facility for the phosphopeptide analysis; and Wendy Salmon for technical assistance with the microscopy studies.

This work was supported by NIH grants CA70940 and GM62375 (A.M.P.) and NIH Training Grant CA009111-27 (E.A.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnaud, L., B. A. Ballif, and J. A. Cooper. 2003. Regulation of protein tyrosine kinase signaling by substrate degradation during brain development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:9293-9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, Y., S. Nonoyama, M. Matsushita, T. Yamadori, S. Hashimoto, K. Imai, S. Arai, T. Kunikata, M. Kurimoto, T. Kurosaki, H. D. Ochs, J. Yata, T. Kishimoto, and S. Tsukada. 1999. Involvement of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein in B-cell cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase pathway. Blood 93:2003-2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourdet-Sicard, R., C. Egile, P. J. Sansonetti, and G. Tran Van Nhieu. 2000. Diversion of cytoskeletal processes by Shigella during invasion of epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 2:813-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourdet-Sicard, R., M. Rudiger, B. M. Jockusch, P. Gounon, P. J. Sansonetti, and G. T. Nhieu. 1999. Binding of the Shigella protein IpaA to vinculin induces F-actin depolymerization. EMBO J. 18:5853-5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton, E. A., R. Plattner, and A. M. Pendergast. 2003. Abl tyrosine kinases are required for infection by Shigella flexneri. EMBO J. 22:5471-5479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlier, M. F., P. Nioche, I. Broutin-L'Hermite, R. Boujemaa, C. Le Clainche, C. Egile, C. Garbay, A. Ducruix, P. Sansonetti, and D. Pantaloni. 2000. GRB2 links signaling to actin assembly by enhancing interaction of neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASp) with actin-related protein (ARP2/3) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275:21946-21952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cory, G. O., R. Cramer, L. Blanchoin, and A. J. Ridley. 2003. Phosphorylation of the WASP-VCA domain increases its affinity for the Arp2/3 complex and enhances actin polymerization by WASP. Mol. Cell 11:1229-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cory, G. O., R. Garg, R. Cramer, and A. J. Ridley. 2002. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 291 enhances the ability of WASp to stimulate actin polymerization and filopodium formation. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45115-45121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cossart, P., and P. J. Sansonetti. 2004. Bacterial invasion: the paradigms of enteroinvasive pathogens. Science 304:242-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disanza, A., M. F. Carlier, T. E. Stradal, D. Didry, E. Frittoli, S. Confalonieri, A. Croce, J. Wehland, P. P. Di Fiore, and G. Scita. 2004. Eps8 controls actin-based motility by capping the barbed ends of actin filaments. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:1180-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egile, C., T. P. Loisel, V. Laurent, R. Li, D. Pantaloni, P. J. Sansonetti, and M. F. Carlier. 1999. Activation of the CDC42 effector N-WASP by the Shigella flexneri IcsA protein promotes actin nucleation by Arp2/3 complex and bacterial actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 146:1319-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frischknecht, F., S. Cudmore, V. Moreau, I. Reckmann, S. Rottger, and M. Way. 1999. Tyrosine phosphorylation is required for actin-based motility of vaccinia but not Listeria or Shigella. Curr. Biol. 9:89-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gishizky, M. L., D. Cortez, and A. M. Pendergast. 1995. Mutant forms of growth factor-binding protein-2 reverse BCR-ABL-induced transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:10889-10893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg, M. B., O. Barzu, C. Parsot, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1993. Unipolar localization and ATPase activity of IcsA, a Shigella flexneri protein involved in intracellular movement. J. Bacteriol. 175:2189-2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grevengoed, E. E., D. T. Fox, J. Gates, and M. Peifer. 2003. Balancing different types of actin polymerization at distinct sites: roles for Abelson kinase and Enabled. J. Cell Biol. 163:1267-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grevengoed, E. E., J. J. Loureiro, T. L. Jesse, and M. Peifer. 2001. Abelson kinase regulates epithelial morphogenesis in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 155:1185-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guinamard, R., P. Aspenstrom, M. Fougereau, P. Chavrier, and J. C. Guillemot. 1998. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein by Lyn and Btk is regulated by CDC42. FEBS Lett. 434:431-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho, H. Y., R. Rohatgi, A. M. Lebensohn, L. Ma, J. Li, S. P. Gygi, and M. W. Kirschner. 2004. Toca-1 mediates Cdc42-dependent actin nucleation by activating the N-WASP-WIP complex. Cell. 118:203-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu, Y., Y. Liu, S. Pelletier, E. Buchdunger, M. Warmuth, D. Fabbro, M. Hallek, R. A. Van Etten, and S. Li. 2004. Requirement of Src kinases Lyn, Hck and Fgr for BCR-ABL1-induced B-lymphoblastic leukemia but not chronic myeloid leukemia. Nat. Genet. 36:453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennison, A. V., and N. K. Verma. 2004. Shigella flexneri infection: pathogenesis and vaccine development. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:43-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadurugamuwa, J. L., M. Rohde, J. Wehland, and K. N. Timmis. 1991. Intercellular spread of Shigella flexneri through a monolayer mediated by membranous protrusions and associated with reorganization of the cytoskeletal protein vinculin. Infect. Immun. 59:3463-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, A. S., L. T. Kakalis, N. Abdul-Manan, G. A. Liu, and M. K. Rosen. 2000. Autoinhibition and activation mechanisms of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Nature. 404:151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loisel, T. P., R. Boujemaa, D. Pantaloni, and M. F. Carlier. 1999. Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins. Nature 401:613-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lommel, S., S. Benesch, K. Rottner, T. Franz, J. Wehland, and R. Kuhn. 2001. Actin pedestal formation by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and intracellular motility of Shigella flexneri are abolished in N-WASP-defective cells. EMBO Rep. 2:850-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miki, H., K. Miura, and T. Takenawa. 1996. N-WASP, a novel actin-depolymerizing protein, regulates the cortical cytoskeletal rearrangement in a PIP2-dependent manner downstream of tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 15:5326-5335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miki, H., T. Sasaki, Y. Takai, and T. Takenawa. 1998. Induction of filopodium formation by a WASP-related actin-depolymerizing protein N-WASP. Nature 391:93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mimuro, H., T. Suzuki, S. Suetsugu, H. Miki, T. Takenawa, and C. Sasakawa. 2000. Profilin is required for sustaining efficient intra- and intercellular spreading of Shigella flexneri. J. Biol. Chem. 275:28893-28901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monack, D. M., and J. A. Theriot. 2001. Actin-based motility is sufficient for bacterial membrane protrusion formation and host cell uptake. Cell. Microbiol. 3:633-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mounier, J., V. Laurent, A. Hall, P. Fort, M. F. Carlier, P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Egile. 1999. Rho family GTPases control entry of Shigella flexneri into epithelial cells but not intracellular motility. J. Cell Sci. 112:2069-2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oaks, E. V., M. E. Wingfield, and S. B. Formal. 1985. Plaque formation by virulent Shigella flexneri. Infect. Immun. 48:124-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oda, A., H. D. Ochs, B. J. Druker, K. Ozaki, C. Watanabe, M. Handa, Y. Miyakawa, and Y. Ikeda. 1998. Collagen induces tyrosine phosphorylation of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein in human platelets. Blood 92:1852-1858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okabe, S., S. Fukuda, and H. E. Broxmeyer. 2002. Activation of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein and its association with other proteins by stromal cell-derived factor-1α is associated with cell migration in a T-lymphocyte line. Exp. Hematol. 30:761-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page, A. L., H. Ohayon, P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1999. The secreted IpaB and IpaC invasins and their cytoplasmic chaperone IpgC are required for intercellular dissemination of Shigella flexneri. Cell. Microbiol. 1:183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plattner, R., B. J. Irvin, S. Guo, K. Blackburn, A. Kazlauskas, R. T. Abraham, J. D. York, and A. M. Pendergast. 2003. A new link between the c-Abl tyrosine kinase and phosphoinositide signalling through PLC-γ1. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plattner, R., L. Kadlec, K. A. DeMali, A. Kazlauskas, and A. M. Pendergast. 1999. c-Abl is activated by growth factors and Src family kinases and has a role in the cellular response to PDGF. Genes Dev. 13:2400-2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ptasznik, R., and A. Ptasznik. 2002. Crosstalk between BCR/ABL oncoprotein and CXCR4 signaling through a Src family kinase in human leukemia cells. J. Exp. Med. 196:667-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rathman, M., P. de Lanerolle, H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, and P. Sansonetti. 2000. Myosin light chain kinase plays an essential role in S. flexneri dissemination. J. Cell Sci. 113:3375-3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rathman, M., N. Jouirhi, A. Allaoui, P. Sansonetti, C. Parsot, and G. Tran Van Nhieu. 2000. The development of a FACS-based strategy for the isolation of Shigella flexneri mutants that are deficient in intercellular spread. Mol. Microbiol. 35:974-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rozelle, A. L., L. M. Machesky, M. Yamamoto, M. H. Driessens, R. H. Insall, M. G. Roth, K. Luby-Phelps, G. Marriott, A. Hall, and H. L. Yin. 2000. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate induces actin-based movement of raft-enriched vesicles through WASP-Arp2/3. Curr. Biol. 10:311-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sansonetti, P. J. 2001. Microbes and microbial toxins: paradigms for microbial-mucosal interactions. III. Shigellosis: from symptoms to molecular pathogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280:G319-G323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sansonetti, P. J., J. Mounier, M. C. Prevost, and R. M. Mege. 1994. Cadherin expression is required for the spread of Shigella flexneri between epithelial cells. Cell 76:829-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shibata, T., F. Takeshima, F. Chen, F. W. Alt, and S. B. Snapper. 2002. Cdc42 facilitates invasion but not the actin-based motility of Shigella. Curr. Biol. 12:341-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sini, P., A. Cannas, A. J. Koleske, P. P. Di Fiore, and G. Scita. 2004. Abl-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Sos-1 mediates growth-factor-induced Rac activation. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:268-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snapper, S. B., F. Takeshima, I. Anton, C. H. Liu, S. M. Thomas, D. Nguyen, D. Dudley, H. Fraser, D. Purich, M. Lopez-Ilasaca, C. Klein, L. Davidson, R. Bronson, R. C. Mulligan, F. Southwick, R. Geha, M. B. Goldberg, F. S. Rosen, J. H. Hartwig, and F. W. Alt. 2001. N-WASP deficiency reveals distinct pathways for cell surface projections and microbial actin-based motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:897-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suetsugu, S., M. Hattori, H. Miki, T. Tezuka, T. Yamamoto, K. Mikoshiba, and T. Takenawa. 2002. Sustained activation of N-WASP through phosphorylation is essential for neurite extension. Dev. Cell 3:645-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tatton, L., G. M. Morley, R. Chopra, and A. Khwaja. 2003. The Src-selective kinase inhibitor PP1 also inhibits Kit and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 278:4847-4853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theriot, J. A., T. J. Mitchison, L. G. Tilney, and D. A. Portnoy. 1992. The rate of actin-based motility of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes equals the rate of actin polymerization. Nature 357:257-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres, E., and M. K. Rosen. 2003. Contingent phosphorylation/dephosphorylation provides a mechanism of molecular memory in WASP. Mol. Cell 11:1215-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tran Van Nhieu, G., R. Bourdet-Sicard, G. Dumenil, A. Blocker, and P. J. Sansonetti. 2000. Bacterial signals and cell responses during Shigella entry into epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tran Van Nhieu, G., C. Clair, R. Bruzzone, M. Mesnil, P. Sansonetti, and L. Combettes. 2003. Connexin-dependent inter-cellular communication increases invasion and dissemination of Shigella in epithelial cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:720-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Etten, R. A., J. Debnath, H. Zhou, and J. M. Casasnovas. 1995. Introduction of a loss-of-function point mutation from the SH3 region of the Caenorhabditis elegans sem-5 gene activates the transforming ability of c-abl in vivo and abolishes binding of proline-rich ligands in vitro. Oncogene 10:1977-1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wen, S. T., P. K. Jackson, and R. A. Van Etten. 1996. The cytostatic function of c-Abl is controlled by multiple nuclear localization signals and requires the p53 and Rb tumor suppressor gene products. EMBO J. 15:1583-1595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Westphal, R. S., S. H. Soderling, N. M. Alto, L. K. Langeberg, and J. D. Scott. 2000. Scar/WAVE-1, a Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein, assembles an actin-associated multikinase scaffold. EMBO J. 19:4589-4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu, X., S. Suetsugu, L. A. Cooper, T. Takenawa, and J. L. Guan. 2004. Focal adhesion kinase regulation of N-WASP subcellular localization and function. J. Biol. Chem. 279:9565-9576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]