Abstract

In this study, two pyrazole-based hydrazone derivatives, 5-methyl-1-phenyl-4-(1-(2-phenylhydrazineylidene)ethyl)-1H-pyrazole (PMPH) and 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-methyl-4-(1-(2-phenylhydrazineylidene)ethyl)-1H-pyrazole (4F-PMPH), were synthesized and the structures of the compounds were elucidated through FT-IR, 1H and 13C NMR, and mass spectral methods. The anti-inflammatory potential was evaluated using the bovine serum albumin denaturation assay, with PMPH and 4F-PMPH showing maximum inhibition at 0.5 mg/mL, respectively, suggesting that fluorine substitution enhances bioactivity. Molecular docking studies against COX-II (PDB: 3LN1) revealed favorable binding energies of − 7.21 kcal/mol (PMPH) and − 8.03 kcal/mol (4F-PMPH). Molecular dynamics simulation of the best docked compound 4F-PMPH with COX-II (PDB: 3LN1) revealed a stable complex over a 100 ns simulation, supporting its potential as a promising inhibitor. In silico ADME analyses revealed pharmacokinetic behavior and drug-likeness. A comparative Density functional theory-based spectroscopic and electronic investigation was conducted using the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. Vibrational frequency analysis showed strong correlation between theoretical and experimental IR spectra. Frontier molecular orbital analysis, molecular electrostatic surface potential maps, Mulliken charges, electronic and global reactivity parameters were also studied. Besides, reduced density gradient, non-covalent interaction, electron localization function, and localized orbital locator maps were analyzed for both the compounds.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-26088-9.

Keywords: Pyrazole, Hydrazone, Density functional theory, Anti-inflammatory, Drug design

Subject terms: Chemical biology, Chemistry, Drug discovery

Introduction

Inflammation is a fundamental physiological defence mechanism activated in response to tissue damage, pathogenic invasion, or other detrimental agents1,2. However, if inflammation lasts too long or does not work properly, it can cause diseases and serious health problems3,4. Therefore, synthesizing new anti-inflammatory candidates that work better is an important target in drug research and development5,6. Among many heterocyclic compounds used in medicine, pyrazole-based structures have become important because they are a key part of many drugs7–10. Pyrazoles are five-membered heterocycles featuring two neighboring nitrogen atoms and their derivatives are known for exhibiting diverse biological properties, such as anti-inflammatory11,12, analgesic12, antibacterial13, antifungal13,14, antioxidant14,15, anticancer16, and antiviral effects17. The structure of pyrazole ring provides better binding interactions, and small changes can improve scaffold’s activity18–20.

Hydrazones are organic compounds with an -NH-N = CH- group, known for diverse biological activities due to their binding interactions with biological receptors21–23. Hydrazone derivatives have been extensively explored for their anti-inflammatory24, antioxidant25, antibacterial26, antitubercular27, and anticancer activities28. Combining pyrazole and hydrazone structures can create hybrid molecules with better biological activity29,30. In this context, the design and synthesis of novel pyrazole-hydrazone derivatives represent a promising approach to discovering new anti-inflammatory agents31. The biologically active pyrazole and hydrazine/hydrazine based drug molecules are depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The biologically active pyrazole and hydrazine/hydrazone based drug molecules.

Computational chemistry offers valuable insights into molecular behavior, reactivity, and drug-likeness31–33. The DFT is one of the computational methods has emerged as a powerful quantum mechanical tool for exploring the electronic structure of molecules34–37. DFT helps to calculate various electronic and chemical properties38–40. Besides, molecular docking predicts the binding interaction of ligands with biological targets41–43. Along with this, ADME analysis complements by predicting pharmacokinetic profiles for further drug development44,45. In this study, two pyrazole hydrazone derivatives were synthesized, characterized, analyzed using DFT and their in vitro anti-inflammatory activity, molecular docking, and ADME properties were evaluated to identify promising candidates as anti-inflammatory agents.

Materials and methods

General remarks

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from local supplier (Make-BLD Pharma, and Avra Chemicals) and were used without further purification. Ethanol and glacial acetic acid of analytical grade and were used as received. Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) was performed on pre-coated silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck) and visualized under UV light at 254 and 365 nm. Melting points were determined using an open capillary method and are uncorrected. The FT-IR spectra were recorded on a JASCO FT-IR spectrophotometer in the range of 4000–400 cm− 1. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer using CDCl3 as solvent, with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard.

Synthesis of pyrazole hydrazones

A mixture of the appropriate pyrazole ketone derivative (1a-1b, 0.01 mol) and phenyl hydrazine (2, 0.01 mol) was dissolved in ethanol (20 mL) in a round-bottom flask. To this solution, 2–3 drops of glacial acetic acid were added to catalyze the reaction. The reaction mixture was refluxed until completion of the reaction. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC using hexane: ethyl acetate (7:3) as the mobile phase. After completion, the reaction mixture was concentrated, and the crude product was filtered, washed with cold ethanol, and dried under vacuum. The obtained solid was purified by recrystallization from ethanol to afford the desired pyrazole hydrazone derivatives (3a-3b) in good yields (Fig. 2). The structures of the synthesized compounds were confirmed by FT-IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and mass spectral methods.

Fig. 2.

Synthesis of pyrazole hydrazones (3a-3b).

Physicochemical and spectral data

5-methyl-1-phenyl-4-(1-(2-phenylhydrazineylidene)ethyl)−1H-pyrazole (3a/PMPH)

Cream colour; M.P.: 188–190 °C; FT-IR (cm− 1): 3278, 3100, 3063, 3005, 2919, 1598, 1557, 1511, 1309, 1226, 1119, 938, 847, 756, 698, 624, 1008, 1070, 541; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.50–7.45 (m, 4H), 7.46–7.41 (m, 2 H), 7.27–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.07 (m, 2H), 6.89–6.82 (m, 1H), 2.64 (s, 3 H), 2.25 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.59, 141.95, 138.89, 129.31, 129.28, 129.13, 128.83, 128.08, 125.56, 125.45, 119.75, 112.88, 13.86, 13.55; Mass (M + H)+ for C18H18N4: 291.1609 (calculated) and 291.1942 (observed).

1-(4-fluorophenyl)−5-methyl-4-(1-(2-phenylhydrazineylidene) ethyl)−1H-pyrazole (3b/4F-PMPH)

Cream colour; M.P.: 200–202 °C; FT-IR (cm− 1): 3269, 3059, 3005, 2915, 1602, 1491, 1404, 1309, 1259, 1193, 1127, 1074, 991, 933, 690, 748, 545; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.51–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.29–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 2H), 7.15–7.04 (m, 2H), 6.89–6.77 (m, 1H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 2.24 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.09 (d, J = 248.4 Hz), 145.54, 141.96, 138.94, 138.02, 136.90, 129.29, 127.29 (d, J = 8.6 Hz), 120.53, 119.80, 116.08 (d, J = 22.9 Hz). 112.88, 13.84, 13.42; Mass (M + H)+ for C18H17FN4: 309.1515 (calculated) and 309.1854 (observed).

In-vitro anti-inflammatory activity using bovine serum albumin assay

We followed earlier reported protocol for performing the BSA assay46. Inhibition of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) denaturation was assessed with slight modifications to the standard method. A stock solution was prepared by dissolving 1 mg of the sample in 1 mL of DMSO. In a 96-well plate, 100 µL of PBS + DMSO (1.5:1) with pH 6.4 (adjusted using 1 N HCl) was added to each well. Next, 100 µL of the stock solution was added to the first well, and two-fold dilutions were made in subsequent wells, creating concentrations ranging from 0.5 mg/mL to 0.0625 mg/mL. Then, 10 µL of 1% BSA solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. After incubation, the solution was heated at 70 °C for 5 min and then allowed to cool to ambient temperature. The turbidity of the samples was measured by absorbance at 660 nm using a Powerwave X2 Elisa Reader.

Docking simulations

The crystal structure of COX-II (PDB ID: 3LN1) was obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank for docking studies46. Protein preparation was performed using Chimera, which included removing all chains except the A-chain, along with heteroatoms and water molecules. Polar hydrogen atoms, partial charges, and solvation parameters were assigned using AutoDockTools46,47, and the protein was saved as a ‘.pdbqt’ file. Ligand 2D structures were drawn in ChemDraw V. 12. 0 and converted to 3D with Avogadro Software48. Ligand optimization was done using AutoDockTools, where no tautomers were considered, and Gasteiger charges were assigned. Docking simulations were performed with ‘AutoDock’ 4.2.6’, using a 0.500 Å grid point spacing and a grid centered at the active site. Parameters for Lamarckian genetic algorithm were set, and docking was run for 100 iterations46,49. Results were analyzed and the best complex conformation was saved. Protein-ligand interactions49 were visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download).

In-Silico ADME analysis

For calculations of theoretical pharmacokinetics analysis, we used ‘SwissADME’ tool50 (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php).

DFT calculations

DFT method is widely used to analyze the electronic properties, stability, and reactivity of many small organic molecules offering insights for applications in chemistry and pharmacology51–53. All DFT computations for the synthesized compounds were carried out in the gas phase using the Gaussian 03 software54. The calculations employed Becke’s three-parameter hybrid exchange functional (B3LYP)55,56 with the 6-31G(d,p) basis set. DFT calculations were performed using the B3LYP functional with the 6-31G(d,p) basis set, which provides a good balance between computational cost and accuracy for geometry optimization, vibrational frequencies, and electronic properties of organic molecules57–60. Molecular visualization was performed using the GaussView 4.1.2 program61.

Results and discussion

DFT study

Structural analysis

The bond length analysis for PMPH and 4F-PMPH was carried out using DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level are given in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. The optimized molecular structures of PMPH and 4F-PMPH are depicted in Fig. 3. The comparison of bond lengths reveals that the introduction of a fluorine atom at the para position of the phenyl ring in compound 4F-PMPH exerts localized structural changes without significantly altering the overall geometry of the molecule.In the pyrazole core (N1-N2-C3-C4-C5), the bond lengths remain relatively consistent between the two molecules. For instance, the N1-N2 bond length is exactly 1.3653 Å in both PMPH and 4F-PMPH, indicating that substitution at the distal phenyl ring does not disrupt the integrity of the pyrazole ring system. Similarly, the N1-C5 bond length shows only a minor difference, being 1.3772 Å in PMPH and 1.3770 Å in 4F-PMPH, while the N1-C16 bond is slightly shorter in 4F-PMPH (1.4206 Å) compared to PMPH (1.4214 Å). The N2-C3 bond, which links the pyrazole ring to the side chain, is virtually unchanged, measuring 1.3213 Å in PMPH and 1.3216 Å in 4F-PMPH. These consistent values indicate that the fluorine substituent does not perturb the conjugated system between the pyrazole ring and the hydrazone linkage. The hydrazone linkage, comprising the N8-N9 and N9-C10 bonds, also exhibits near-identical bond lengths between the two molecules. In PMPH, the N8-N9 bond measures 1.3485 Å, while in 4F-PMPH, it is slightly shorter at 1.3481 Å, a negligible difference of only 0.0004 Å. Similarly, the N9-C10 bond length is 1.3945 Å in PMPH and 1.3948 Å in 4F-PMPH. The most notable structural differences arise in the phenyl ring attached to the pyrazole core, particularly near the fluorine substitution site in 4F-PMPH. The C18-C19 bond, which is adjacent to the fluorine atom, is slightly shorter in 4F-PMPH (1.3913 Å) compared to PMPH (1.3972 Å), reflecting the electron-withdrawing inductive effect of fluorine. A similar trend is observed for the C19-C20 bond, which shortens from 1.3947 Å in PMPH to 1.3890 Å in 4F-PMPH. A key difference is seen in the C19-F40 bond in 4F-PMPH, which measures 1.349 Å, representing the characteristic bond length for an aromatic carbon-fluorine bond. In contrast, the equivalent position in PMPH is occupied by a hydrogen atom, with the C19-H40 bond length being 1.0971 Å. This 0.252 Å increase is expected due to the larger atomic radius of fluorine compared to hydrogen. The hydrazone-linked phenyl ring, which spans C10 to C15, shows no meaningful difference between the two molecules. The C10-C11 bond length is 1.4046 Å in PMPH and 1.4045 Å in 4F-PMPH, while the C11-C12 bond remains constant at 1.3922 Å in both cases.

Fig. 3.

Optimized molecular structures of PMPH and 4F- PMPH.

Mulliken charge study

The Mulliken charge analysis for PMPH and 4F-PMPH was performed using the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) computational method to understand the electronic distribution and the effect of fluorine substitution on the overall electron density of the molecules51,52. These values given in Tables S3 and S4 provide insight into how the electron density is distributed across different atoms, which influences the molecular reactivity, stability, and potential biological activity. In PMPH, the pyrazole nitrogen atoms (N1, N2) have significant negative charges (−0.43034, −0.31118), reflecting their electron-rich nature and contribution to the delocalized π-system. Hydrazone nitrogens (N8, N9) also show negative charges (−0.28935, −0.46398). Pyrazole carbons (C3–C6) display partial positive and negative charges, showing delocalization, while phenyl carbons (C12–C17) are slightly electron-rich (−0.09124 to −0.10297). Upon para-fluorine substitution in 4F-PMPH, the fluorine atom (F40, −0.29503) exerts a strong electron-withdrawing effect, polarizing adjacent carbons (C18: −0.15197; C19: 0.359955) and phenyl hydrogens (H37: 0.131705; H38: 0.13572). The pyrazole (N1, N2: −0.43141, −0.3126) and hydrazone nitrogens (N8, N9: −0.28894, −0.46373) remain largely unaffected.

Vibrational assignments study

A comprehensive vibrational spectroscopic analysis of PMPH and 4F-PMPH was carried out using DFT method at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level, and the theoretical vibrational frequencies were compared with experimental FT-IR data to validate the molecular structure and functional groups (Tables 1 and 2). The experimental and computed IR spectra of PMPH are given in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively while Figs. 6 and 7 depicts the experimental and computed IR spectra of 4F-PMPH. A close correlation between the scaled theoretical and experimental vibrational modes was observed, confirming the reliability of the computational method. The vibrational spectra of PMPH along with the detailed mode assignments are presented and discussed below. The NH stretching vibration appeared prominently at 3420 cm− 1 (theoretical) and 3278 cm− 1 (experimental), signifying strong hydrogen bonding or intermolecular interactions. The aromatic sp2 C–H stretching vibrations of the phenyl rings were observed at 3108 and 3062 cm− 1 theoretically, aligning well with the experimental peaks at 3100 and 3063 cm− 1, respectively. The asymmetric and symmetric stretching of the methylene group (C22–H2) was computed at 3017 and 2916 cm− 1, closely matching the experimental peaks at 3005 and 2919 cm− 1, respectively. The C = N stretching, characteristic of the hydrazone moiety, was found at 1585 cm− 1 (theoretical) and 1598 cm− 1 (experimental), while the C = C stretching vibrations of both phenyl rings were well represented around 1578 and 1502 cm− 1 theoretically, and matched by 1557 and 1511 cm− 1 experimentally. Deformation vibrations of the phenyl ring and characteristic stretching modes such as C–N and N–N were also in good agreement (e.g., 1308/1309 and 1128/1119 cm− 1 for theoretical/experimental values). Additionally, C–H in-plane and out-of-plane bending modes, as well as ring deformation frequencies, were accurately predicted and validated through experimental data. The vibrational assignments of the compound 4F-PMPH are discussed in detail below. The NH stretching mode was predicted at 3420 cm− 1 and experimentally observed at 3269 cm− 1, indicating potential involvement in hydrogen bonding interactions. The aromatic C–H stretching of the phenyl ring appeared at 3062 cm− 1 (theoretical) and 3059 cm− 1 (experimental), while the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the C22–H2 group were recorded at 3016 and 2915 cm− 1, closely matching the observed peaks at 3005 and 2915 cm− 1. The characteristic C = N stretching vibration, a marker of the hydrazone linkage, was evident at 1586 cm− 1 theoretically and 1602 cm− 1 experimentally. C = C stretching vibrations of both phenyl rings were consistently observed around 1496 cm− 1 (theoretical) and 1491 cm− 1 (experimental). Notably, the 4-fluorophenyl substitution influenced the vibrational profile, with distinct modes such as C = C (1404 cm− 1), deformation (1309 cm− 1), and in-plane C–H bending (1259 cm− 1) being clearly assigned and supported by calculated values. The N–N and N–C stretching modes, as well as CH3 and phenyl out-of-plane bending vibrations, were all confirmed further validating the computational predictions.

Table 1.

Comparative vibrational frequency data for PMPH showing theoretical (DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) scaled) and experimental wavenumbers along with vibrational mode assignments.

| Mode | Theoretical Wavenumber (scaled, cm−1) | Experimental Wavenumber (cm−1) |

Vibrational assignments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 114 | 3420 | 3278 | NH stretching |

| 112 | 3108 | 3100 | sp2 C-H of Ph rings stretching |

| 106 | 3062 | 3063 | sp2 C-H of Ph rings stretching |

| 101 | 3017 | 3005 | C22-H2 asymmetric stretching |

| 98 | 2916 | 2919 | C22-H2 symmetric stretching |

| 94 | 1585 | 1598 | C = N stretching |

| 92 | 1578 | 1557 | C = C stretching of both Ph rings |

| 90 | 1502 | 1511 | C = C stretching of both Ph rings |

| 75 | 1308 | 1309 | deformation Ph ring attached to pyrazole |

| 71 | 1243 | 1226 | C10-N9 stretching |

| 64 | 1128 | 1119 | N8-N9 stretching |

| 62 | 1064 | 1070 | C-H in plane bending Ph attached to hydrazone |

| 58 | 1016 | 1008 | C-H in plane bending Ph attached to pyrazole |

| 50 | 948 | 938 | C-H out of plane bending Ph attached to hydrazone |

| 44 | 853 | 847 | C3-H23 out of plane bending |

| 40 | 747 | 756 | C-H out of plane bending Ph attached to pyrazole |

| 37 | 696 | 698 | deformation of all rings |

Table 2.

Comparative vibrational frequency data for 4F-PMPH showing theoretical (DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) scaled) and experimental wavenumbers along with vibrational mode assignments.

| Mode | Theoretical Wavenumber (scaled, cm−1) | Experimental Wavenumber (cm−1) |

Vibrational assignments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 114 | 3420.125 | 3269 | NH stretching |

| 106 | 3062.266 | 3059 | CH stretching of phenyl ring |

| 102 | 3016.694 | 3005 | C22-H2 asymmetric stretching |

| 99 | 2915.405 | 2915 | C22-H2 symmetric stretching |

| 95 | 1586.045 | 1602 | C = N stretching |

| 90 | 1496.65 | 1491 | C = C stretching both Ph rings |

| 82 | 1403.645 | 1404 | C = C of 4-fluorophenyl stretching |

| 76 | 1300.56 | 1309 | Deformation of 4-fluorophenyl stretching |

| 74 | 1267.315 | 1259 | C-H in plane bending of 4-fluorophenyl ring |

| 69 | 1213.402 | 1193 | N8-N9 stretching |

| 67 | 1136.89 | 1127 | C-H in plane bending of phenyl ring |

| 63 | 1071.974 | 1074 | N1-N2 stretching |

| 57 | 997.8912 | 991 | CH3 out of plane bending |

| 53 | 947.9904 | 933 | CH out of plane bending of phenyl ring |

| 39 | 689.4336 | 690 | Deformation of 4-fluorophenyl ring |

Fig. 4.

Experimental IR spectrum of PMPH.

Fig. 5.

Computed IR spectrum of PMPH.

Fig. 6.

Experimental IR spectrum of 4F-PMPH.

Fig. 7.

Computed IR spectrum of 4F-PMPH.

Frontier molecular orbital study

Figure 8 illustrates the frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs), the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), for both PMPH and 4F-PMPH. The visualized FMOs reveal the distribution of electron densities and their influence on the electronic properties of the molecules53. PMPH exhibits HOMO energy of −4.946 eV and a LUMO energy of −0.783 eV, resulting in an energy gap (Eg) of 4.163 eV. In comparison, 4F-PMPH shows a slightly reduced HOMO-LUMO energy gap of 4.144 eV, with HOMO and LUMO energies of −4.899 eV and − 0.755 eV, respectively. The narrower energy gap in 4F-PMPH indicates slightly enhanced electronic delocalization due to the electron-withdrawing fluorine substituent. Table 3 shows the electronic and global reactivity descriptors for PMPH and 4F-PMPH. The global reactivity descriptors calculated from DFT data offer valuable insights into the chemical behavior of PMPH and 4F-PMPH. The ionization potential (I), calculated as the negative of the HOMO energy, is 4.946 eV for PMPH and 4.899 eV for 4F-PMPH. This indicates that PMPH requires slightly more energy to remove an electron, suggesting marginally greater electronic stability.The electron affinity (A), derived from the negative of the LUMO energy, is 0.783 eV for PMPH and 0.755 eV for4F-PMPH, indicating a similar tendency of both molecules to accept electrons. The electronegativity (χ), which reflects the tendency of an atom or molecule to attract electrons, is slightly higher in PMPH (2.864 eV) than in 4F-PMPH (2.827 eV). This suggests PMPH has a marginally stronger electron-withdrawing nature. The chemical hardness (η), representing resistance to change in electron distribution, is 2.081 eV for PMPH and 2.072 eV for 4 F-PMPH, showing both molecules are comparably hard, or resistant to charge transfer. The corresponding chemical softness (S) values are 0.240 eV− 1 for PMPH and 0.241 eV− 1 for 4F-PMPH, which further confirms this similarity in their polarizability. The chemical potential (µ), the negative of electronegativity, is − 2.864 eV for PMPH and − 2.827 eV for 4F-PMPH, indicating similar tendencies for electron release or escape. Finally, the electrophilicity index (ω), which measures the ability of a molecule to accept electrons, is 1.972 eV for PMPH and 1.927 eV for 4F-PMPH. This suggests that PMPH may behave as a slightly stronger electrophile compared to its fluorinated derivative. The inclusion of a fluorine atom in 4F-PMPH subtly reduces the values of ionization potential, electronegativity, and electrophilicity, indicating that fluorine substitution slightly increases electron-donating character and reactivity without significantly compromising stability.

Fig. 8.

Frontier molecular orbital pictures and bang gap of PMPH and 4F-PMPH.

Table 3.

Electronic and global reactivity descriptors for PMPH and 4F-PMPH.

| Descriptor | PMPH | 4F-PMPH |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO Energy (EHOMO) | −4.946 eV | −4.899 eV |

| LUMO Energy (ELUMO) | −0.783 eV | −0.755 eV |

| Energy Gap (Eg) | 4.163 eV | 4.144 eV |

| Ionization Potential (I) | 4.946 eV | 4.899 eV |

| Electron Affinity (A) | 0.783 eV | 0.755 eV |

| Electronegativity (χ) | 2.864 eV | 2.827 eV |

| Chemical Hardness (η) | 2.081 eV | 2.072 eV |

| Chemical Softness (S) | 0.240 eV− 1 | 0.241 eV− 1 |

| Chemical Potential (µ) | −2.864 eV | −2.827 |

| Electrophilicity Index (ω) | 1.972 eV | 1.927 eV |

Molecular electrostatic surface potential analysis

Figure 9 presents the Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MESP) surfaces of the compounds PMPH and 4F-PMPH, offering a visual representation of the charge distribution over the molecular surfaces. MESP is a powerful tool for identifying electrophilic and nucleophilic reactive sites within a molecule by mapping electrostatic potential values to color gradients51,52. In both structures, regions of high electron density (negative potential) appear in red, indicating sites favorable for electrophilic attack, while areas of positive potential appear in blue, indicating regions susceptible to nucleophilic attack. Intermediate regions range from yellow to green, representing neutral or weakly polarized zones. For PMPH, a prominent red region is observed over the carbonyl-linked hydrazone moiety and adjacent nitrogen atoms, indicating a strong electron-rich zone due to lone pair delocalization. The phenyl rings show moderately neutral electrostatic potential, with slight variations due to conjugation. In 4F-PMPH, the substitution of a fluorine atom at the para position of one phenyl ring introduces a significant shift in electron distribution. The nitrogen atoms in the hydrazone group and adjacent ring continue to exhibit electron-rich character, similar to PMPH. The blue zones, especially around the hydrogen atoms of the pyrazole and hydrazone units, suggest regions of positive potential and potential nucleophilic interaction sites. The MESP analysis reveals that both PMPH and 4F-PMPH possess well-defined electron-rich (electrophilic) and electron-poor (nucleophilic) regions. However, the fluorine substitution in 4F-PMPH enhances the asymmetry of charge distribution, potentially improving its binding affinity with biomolecular targets or affecting its solubility and reactivity profiles.

Fig. 9.

MESP pictures of PMPH and 4F-PMPH.

NCI and RDG analysis

Non-covalent interaction (NCI) analysis and reduced density gradient (RDG) for the compounds were analyzed62. These are given in Figs. 10 and 11. NCI analysis of PMPH and 4F-PMPH was performed to understand the nature and distribution of weak interactions within the molecules. The RDG vs. sign(λ2)ρ scatter plots and NCI isosurface maps revealed regions corresponding to attractive interactions (blue, primarily hydrogen bonding), van der Waals interactions (green), and steric repulsion (red). These analyses indicate that both molecules are stabilized by a combination of weak interactions, which may influence their molecular conformations and contribute to favorable binding affinities observed in molecular docking studies against COX-II.

Fig. 10.

NCI analysis of the PMPH molecule. Left: RDG vs. sign(λ2)ρ scatter plot showing blue (hydrogen bonding/attractive interactions), green (van der Waals interactions), and red (steric repulsion) regions. Right: NCI isosurface plot mapped on the molecular structure, with color coding corresponding to the type of interaction.

Fig. 11.

NCI analysis of the 4F-PMPH molecule. Left: RDG vs. sign(λ2)ρ scatter plot showing blue (hydrogen bonding/attractive interactions), green (van der Waals interactions), and red (steric repulsion) regions. Right: NCI isosurface plot mapped on the molecular structure, with color coding corresponding to the type of interaction.

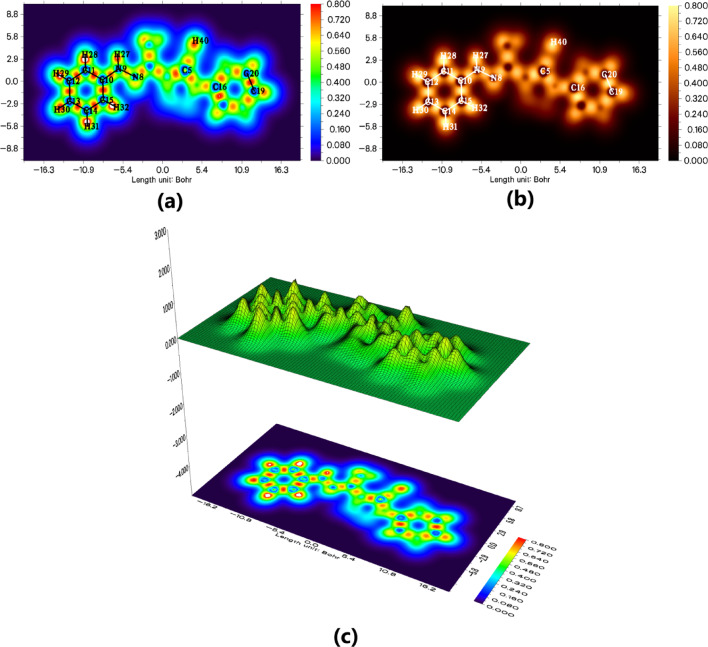

ELF and LOL study

Silvi and Savin63 comprehended the most important techniques used in this investigation, including the electron localization function (ELF) and localized orbital locator (LOL) analyses that were derived from the surface analysis that was reliant on the covalent bond. ELF and LOL analyses were performed for PMPH and 4F-PMPH to investigate the distribution and localization of electrons within the molecules (Figs. 12a and b and 13a and b). The 2D, 3D, and contour maps of ELF and LOL show the regions of high electron localization (red/yellow) and low localization (blue). These analyses indicate areas of strong covalent bonding and lone pair electron density, as well as delocalized regions, providing insight into the electronic structure and chemical reactivity of the compounds. ELF and LOL maps complement the frontier molecular orbital and NCI analyses, offering a comprehensive understanding of the electronic features governing molecular stability and reactivity.

Fig. 12.

Electron Localization Function (ELF) analysis of the PMPH molecule: (a) ELF 2D map, (b) ELF 3D surface plot, and (c) ELF contour map and Localized Orbital Locator (LOL) analysis of the PMPH molecule: (a) LOL 2D map, (b) LOL color-filled map, and (c) LOL 3D surface plot with contour representation.

Fig. 14.

In-vitro anti-inflammatory activity (% Inhibition) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) assay.

Fig. 13.

Electron Localization Function (ELF) analysis of the 4F-PMPH molecule: (a) ELF 2D map, (b) ELF 3D surface plot, and (c) ELF contour map and Localized Orbital Locator (LOL) analysis of the 4F-PMPH molecule: (a) LOL 2D map, (b) LOL color-filled map, and (c) LOL 3D surface plot with contour representation.

In-Vitro anti-inflammatory activity

The anti-inflammatory activity of synthesized pyrazoles was evaluated in vitro using the Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) assay (Fig. 14). This assay relies on the fact that external factors can cause protein denaturation, a key factor in inflammation, and the inhibition of this denaturation serves as the basis for the test. The anti-inflammatory activity of the compounds was evaluated at various concentrations (0.03125 mg/mL to 0.5 mg/mL), revealing a concentration-dependent increase in activity. Compound PMPH exhibited a moderate rise in activity, starting at 63.38% at 0.03125 mg/mL and reaching 76.38% at 0.5 mg/mL. Compound 4F-PMPH showed a stronger response, increasing from 65.87% at 0.03125 mg/mL to 81.15% at 0.5 mg/mL. However, Standard demonstrated the most significant improvement, starting at 14.95% at 0.03125 mg/mL and rapidly increasing to 82.39% at 0.5 mg/mL, indicating its potent anti-inflammatory effect at higher concentrations. The cytotoxicity study was not evaluated in the present study, but such studies are important for establishing the preliminary safety profile of PMPH and 4F-PMPH.

Molecular Docking analysis

To explore the binding properties of the synthesized compounds, PMPH and 4F-PMPH, we evaluated their interaction with the COX-II enzyme (PDB ID: 3LN1) using the Autodock V.2 tool. To ensure the docking protocol’s reliability, we re-docked the co-crystalized ligand into the binding site and confirmed that the RMSD value was below 2.0 Å.

The docking scores for compounds 4F-PMPH and PMPH were − 9.78 kcal/mol and − 9.56 kcal/mol, respectively, with 4F-PMPH exhibiting a slightly higher binding affinity. Compound PMPH interacted with amino acid residues including Ala513 (π-Sigma interaction), Val335 (π-Sigma interaction), Val102 (π-alkyl interaction), Leu345 (π-alkyl interaction), Leu338 (π-Amide stacking interaction), Val509, Ala502 (π-alkyl interaction), and Leu517 (π-Sigma interaction) (Figs. 15 and 16a and c). On the other hand, compound 4F-PMPH displayed interactions with Val102 (π-Sigma interaction), Tyr341 (π-π interaction), Leu78 (π-alkyl interaction), Val335 (π-Sigma interaction), Ala513 (π-alkyl interaction), and Leu338 (π-alkyl interaction). When compared to the standard Celecoxib, which had a binding energy of −9.27 kcal/mol, Celecoxib interacted with Tyr371, Leu370, Val509, Ser339, Arg499, Gln178, Leu338, His75, and others (Fig. 16 (c)). In conclusion, both compounds PMPH and 4F-PMPH showed higher binding affinity scores than the standard Celecoxib.

Fig. 15.

3D interaction diagrams for compounds PMPH (a), 4F-PMPH (b) and (c) celecoxib against the target COX-II enzyme.

Fig. 16.

2D interaction diagrams for compounds PMPH (a), 4F-PMPH (b) and (c) celecoxib against the target COX-II enzyme.

Molecular dynamics analysis

MD simulation analysis was carried out for the best docked compound, 4F-PMPH against the COX-II (PDB: 3LN1) using the ‘Desmond module’ (Academically Free Version, 2017) using the earlier reported protocols64 for standard simulation runs. Molecular dynamics analysis indicated good stability of docked complex ‘4F-PMPH: 3LN1’ under simulation period of 100 ns. The system was comprised of 25,945 atoms while, it had 5683 water molecules. The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) analysis indicated good protein RMSD value below 2.7 Å Fig. 17 (a). The RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) revealed that no significant changes were observed denoting local changes along the protein chain. Minor fluctuations around residue indexes ≈ 70, 100, 320 and 480–510 were noticed Fig. 17b). Protein secondary structure elements (SSE) analysis signified the involvement of 37.32% helixes, 4.25% beta-strands accounting total of 41.57 SSE. The protein-ligand interaction plot pointed out major involvement of hydrophobic interactions with amino acid residues such as His75, Met99, Val102, Leu103, Arg106, Ile331, Val335, Tyr341, and Met521, etc. Figure 17(c). We also noticed four H-bonding interactions with Arg106, Leu338, Tyr341, and Ser516. A timeline representation of the interactions indicated that amino acid residues such as Arg106, val509, Ala513, Leu517 had > 4 interactions during each ns runs Fig. 17 (e). A schematic of detailed ligand atom interactions with the protein residues. Interactions that occur more than 10.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 100.00 nsec), are shown in Fig. 17 (d).

Fig. 17.

(a-e) Molecular dynamics analysis for complex ‘4F-PMPH: 3LN1’; (a) RMSD analysis; (b) Protein RMSF; (c) Protein-ligand contact plot; (d) Interactions that occur more than 10.0% of the simulation time in the selected trajectory (0.00 through 100.00 nsec) and (e) A timeline representation of the number of interactions and contacts.

ADME analysis

In-silico ADME analysis of PMPH and 4F-PMPH reveals moderate solubility, high gastrointestinal absorption, and blood–brain barrier permeability, with both compounds adhering to Lipinski’s Rule of Five and showing favorable drug-likeness (Table 4). TPSA values are identical (42.21 Å2), while solubility predictions vary across models. Neither compound is a P-glycoprotein substrate, but both may inhibit multiple CYP450 enzymes. Bioavailability scores are moderate (0.55), with no PAINS or Brenk alerts, though synthetic accessibility is relatively low (2.8). In summary, both the molecules show promising pharmacokinetic properties, but solubility and CYP inhibition may require further optimization for therapeutic development.

Table 4.

In-Silico ADME analysis for compounds PMPH and 4F-PMPH.

| Molecule | #Heavy atoms | #Aromatic heavy atoms | Fraction Csp3 | #Rotatable bonds | #H-bond acceptors | #H-bond donors | MR | TPSA | iLOGP | XLOGP3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMPH | 22 | 17 | 0.11 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 90.81 | 42.21 | 2.92 | 4.13 |

| 4F-PMPH | 23 | 17 | 0.11 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 90.77 | 42.21 | 3.11 | 4.23 |

| WLOGP | MLOGP | Silicos-IT Log P | Consensus Log P | ESOL Log S | ESOL Solubility (mg/ml) | ESOL Solubility (mol/l) | ESOL Class | Ali Log S | Ali Solubility (mg/ml) | |

| PMPH | 3.83 | 3.17 | 3.3 | 3.47 | −4.55 | 8.18E-03 | 2.82E-05 | Moderately soluble | −4.72 | 5.49E-03 |

| 4F-PMPH | 4.39 | 3.55 | 3.71 | 3.8 | −4.7 | 6.16E-03 | 2.00E-05 | Moderately soluble | −4.83 | 4.59E-03 |

| Silicos-IT class | GI absorption | BBB permeant | Pgp substrate | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | CYP2C9 inhibitor | CYP2D6 inhibitor | CYP3A4 inhibitor | log Kp (cm/s) | |

| PMPH | Poorly soluble | High | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | −5.14 |

| 4F-FPMPH | Poorly soluble | High | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | −5.18 |

| Lipinski #violations | Ghose #violations | Veber #violations | Egan #violations | Muegge #violations | Bioavailability Score | PAINS #alerts | Brenk #alerts | Leadlikeness #violations | Synthetic Accessibility | |

| PMPH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.55 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2.8 |

| 4F-PMPH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.55 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2.8 |

Conclusion

In this study, two hydrazone-linked pyrazole derivatives, PMPH and 4F-PMPH, were comprehensively analyzed using experimental and computational methods. DFT calculations revealed that fluorine substitution at the para-position in 4F-PMPH induces localized structural and electronic changes without disrupting the core molecular geometry. Vibrational confirmed the preservation of key functional groups, Mulliken charge analyses provided in-depth analysis of charge density while frontier molecular orbital and MESP studies demonstrated slight enhancements in electronic delocalization and charge distribution due to fluorine incorporation. NCI, ELF, and LOL analyses highlighted stable intramolecular interactions and electron localization patterns, supporting the structural stability of both compounds. In vitro assays confirmed the anti-inflammatory potential of both PMPH and 4F-PMPH, with the latter showing slightly higher activity. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations further validated the strong and stable binding of 4F-PMPH with COX-II, supported by favorable interaction profiles and consistent RMSD values over a 100 ns. ADME predictions indicated good drug-likeness, oral bioavailability, and pharmacokinetic potential. In summary, 4F-PMPH emerges as a promising lead compound with enhanced biological activity and binding affinity, making it a suitable candidate for further optimization in anti-inflammatory drug development.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

H.K.A.Y. would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Research, Ajman University, UAE, for their support in providing assistance in article processing charges. The authors sincerely acknowledge CIF, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, for NMR analysis of the synthesized compounds. Gratitude is extended to the Research Centre in Chemistry, Loknete Vyankatrao Hiray Arts, Science, and Commerce College, Panchavati, Nashik for providing laboratory facilities.

Author contributions

H.S.D.: Synthesis and experimental work, manuscript preparation; V.A.A.: Conceptualization, supervision, manuscript preparation; A.A.P.F.: Computational studies; S.N.M.: Computational studies, Data analysis, manuscript preparation; H.K.A.Y.: Manuscript preparation; B.N.P.: Spectral characterization support; S.J.: Computational studies; B.S.J.: Supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vishnu A. Adole, Email: vishnuadole86@gmail.com

Haya Khader Ahmad Yasin, Email: Yasinh.yasin@ajman.ac.ae.

References

- 1.Gusev, E. & Zhuravleva, Y. Inflammation: A new look at an old problem. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(9), p.4596. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Medzhitov, R. The spectrum of inflammatory responses. Science374 (6571), 1070–1075 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapoor, G., Prakash, S., Jaiswal, V. & Singh, A. K. Chronic inflammation and cancer: key pathways and targeted therapies. Cancer Invest.43 (1), 1–23 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pezone, A. et al. Inflammation and DNA damage: cause, effect or both. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol.19 (4), 200–211 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahesh, G., Anil Kumar, K. & Reddanna, P. Overview on the discovery and development of anti-inflammatory drugs: should the focus be on synthesis or degradation of PGE2? J. Inflamm. Res.14, 253–263 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ju, Z. et al. Recent development on COX-2 inhibitors as promising anti-inflammatory agents: the past 10 years. Acta Pharm. Sinica B. 12 (6), 2790–2807 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam, M. A. Pyrazole: an emerging privileged scaffold in drug discovery. Future Med. Chem.15 (21), 2011–2023 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alam, M. J. et al. Recent advancement in drug design and discovery of pyrazole biomolecules as cancer and inflammation therapeutics. Molecules, 27(24), p.8708. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bendi, A. et al. Innovative pyrazole hybrids: A new era in drug discovery and synthesis. Chem. Biodivers.22 (4), e202402370 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ríos, M. C. & Portilla, J. Recent advances in synthesis and properties of pyrazoles. Chemistry4 (3), 940–968 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantzanidou, M., Pontiki, E. & Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. Pyrazoles and pyrazolines as anti-inflammatory agents. Molecules, 26(11), p.3439. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Bekhit, A. A. et al. K. and Investigation of the anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of promising pyrazole derivative. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 168, p.106080. (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Gangurde, K. B., More, R. A., Adole, V. A. & Ghotekar, D. S. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of new series of benzotriazole-pyrazole clubbed thiazole hybrids as bioactive heterocycles: Antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, cytotoxicity study. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1299, p.136760. (2024).

- 14.Pathade, S. S., Adole, V. A. & Jagdale, B. S. PEG-400 mediated synthesis, computational, antibacterial and antifungal studies of fluorinated pyrazolines. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 4, p.100172. (2021).

- 15.Dhonnar, S. L., Jagdale, B. S., Adole, V. A. & Sadgir, N. V. PEG-mediated synthesis, antibacterial, antifungal and antioxidant studies of some new 1, 3, 5-trisubstituted 2-pyrazolines. Mol. Diversity. 27 (6), 2441–2452 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan, S., Paliwal, S. & Chauhan, R. Anticancer activity of pyrazole via different biological mechanisms. Synth. Commun.44 (10), 1333–1374 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karati, D., Mahadik, K. R. & Kumar, D. Pyrazole scaffolds: centrality in anti-inflammatory and antiviral drug design. Med. Chem.18 (10), 1060–1072 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh, G., Chandra, P. & Sachan, N. Chemistry and Pharmacological activities of pyrazole and pyrazole derivatives: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res.65 (1), 201–214 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karrouchi, K. et al. Synthesis and pharmacological activities of pyrazole derivatives: A review. Molecules, 23(1), p.134. (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Faisal, M., Saeed, A., Hussain, S., Dar, P. & Larik, F. A. Recent developments in synthetic chemistry and biological activities of pyrazole derivatives. J. Chem. Sci.131, 1–30 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Brum, O. C., França, J., LaPlante, T. C., Villar, J. D. F. & S.R. and Synthesis and biological activity of hydrazones and derivatives: A review. Mini Rev. Med. Chem.20 (5), 342–368 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollas, S. & Güniz Küçükgüzel, Ş. Biological activities of hydrazone derivatives. Molecules12 (8), 1910–1939 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali, M. R. et al. Review of biological activities of hydrazones. Indonesian J. Pharm.23 (4), 193–202 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zlatanova-Tenisheva, H. & Vladimirova, S. Pharmacological Evaluation of Novel Hydrazide and Hydrazone Derivatives: Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Potential in Preclinical Models. Molecules, 30(7), p.1472. (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Tayade, K. et al. Exploration of Molecular Structure, DFT Calculations, and Antioxidant Activity of a Hydrazone Derivative. Antioxidants, 11(11), p.2138. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Sztanke, M., Wilk, A. & Sztanke, K. An Insight into Fluorinated Imines and Hydrazones as Antibacterial Agents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(6), p.3341. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Thorat, B. R. et al. Hydrazide-Hydrazone derivatives and their antitubercular activity. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem.51 (1), 35–52 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vahora, A. et al. Green synthesis of pyrazole linked thiazole derivatives with enhanced anti-breast cancer activity: WEB‐mediated protocol, anticancer screening, EGFR inhibition, in silico ADME and DFT calculations. Chem. Biodivers. pe202402791. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Sable, Y. R., Adole, V. A., Pithawala, E. A. & Amrutkar, R. D. Design, synthesis, and antitubercular evaluation of piperazinyl-pyrazolyl-2-hydrazinyl thiazole derivatives: Experimental, DFT and molecular Docking insights. J. Sulfur Chem.46, 1–26 (2025).

- 30.Gangurde, K. B., More, R. A., Adole, V. A. & Ghotekar, D. S. Synthesis, antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, cytotoxicity and molecular docking studies of thiazole derivatives. Results in Chemistry, 7, p.101380. (2024).

- 31.Abdelgawad, M. A., Labib, M. B. & Abdel-Latif, M. Pyrazole-hydrazone derivatives as anti-inflammatory agents: Design, synthesis, biological evaluation, COX-1, 2/5-LOX Inhibition and Docking study. Bioorg. Chem.74, 212–220 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavasotto, C. N., Aucar, M. G. & Adler, N. S. Computational chemistry in drug lead discovery and design. Int. J. Quantum Chem.119 (2), e25678 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussein, Y. T. & Azeez, Y. H. DFT analysis and in Silico exploration of drug-likeness, toxicity prediction, bioactivity score, and chemical reactivity properties of the urolithins. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynamics. 41 (4), 1168–1177 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tutone, M. & Almerico, A. M. Computational approaches: drug discovery and design in medicinal chemistry and bioinformatics. Molecules, 26(24), p.7500. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Sadgir, N. V., Dhonnar, S. L. & Jagdale, B. S. Synthesis, molecular structure, FMO, spectroscopic, antimicrobial and in-silico investigation of (E)-1-(benzo [d][1, 3] dioxol-5-yl)-3-(4-aryl) prop-2-en-1-one derivative: Experimental and computational study. Results in Chemistry, 5, p.100887. (2023).

- 36.Manjula, R. et al. A comprehensive investigation into the spectroscopic properties, solvent effects on electronic properties, structural characteristics, topological insights, reactive sites, and molecular docking of racecadotril: A potential antiviral and antiproliferative agent. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society, 102(5), p.101702. (2025).

- 37.Jayaprakash, P., Rajamanickam, R. & Selvaraj, S. Quantum computational investigation into the optoelectronic and NLO properties of C8H8O3. C3H7NO2 single crystal. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1319, p.139488. (2025).

- 38.Choudhary, V., Bhatt, A., Dash, D. & Sharma, N. DFT calculations on molecular structures, HOMO–LUMO study, reactivity descriptors and spectral analyses of newly synthesized Diorganotin (IV) 2-chloridophenylacetohydroxamate complexes. J. Comput. Chem.40 (27), 2354–2363 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Domingo, L. R. & Pérez, P. Global and local reactivity indices for electrophilic/nucleophilic free radicals. Org. Biomol. Chem.11 (26), 4350–4358 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang, Y., Rong, C., Zhang, R. & Liu, S. Evaluating frontier orbital energy and HOMO/LUMO gap with descriptors from density functional reactivity theory. J. Mol. Model.23, 1–12 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dunya, A. D., AL-Zubaidy, H. F., Al-Khafaji, K. & Al-Amiery, A. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory effects, molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies of 4-hydroxy coumarin derivatives as inhibitors of COX-II enzyme. Journal of Molecular Structure, 1247, p.131377. (2022).

- 42.Alaa, A. M. et al. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, COX-1/2 inhibitory activities and molecular Docking studies of substituted 2-mercapto-4 (3H)-quinazolinones. Eur. J. Med. Chem.121, 410–421 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chahal, S. et al. Design and development of COX-II inhibitors: current scenario and future perspective. ACS Omega. 8 (20), 17446–17498 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira, L. L. & Andricopulo, A. D. ADMET modeling approaches in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 24 (5), 1157–1165 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hantoush, A., Najim, Z. & Abachi, F. Density functional theory, ADME and Docking studies of some tetrahydropyrimidine-5-carboxylate derivatives. Eurasian Chem. Commun.4, 778–789 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sihag, M. et al. Synthesis of pyrazole and pyrazoline derivatives of β-ionone: Exploring anti-inflammatory potential, cytotoxicity, and molecular docking insights. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports, 12, p.100204. (2024).

- 47.Huey, R., Morris, G. M. & Forli, S. Using AutoDock 4 and AutoDock vina with AutoDockTools: a tutorial. The Scripps Research Institute Molecular Graphics Laboratory, 10550(92037), p.1000. (2012).

- 48.Snyder, H. D. & Kucukkal, T. G. Computational chemistry activities with avogadro and ORCA. J. Chem. Educ.98 (4), 1335–1341 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Basri, R. et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular modelling of 3-Formyl-6-isopropylchromone derived thiosemicarbazones as α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorganic Chemistry, 139, p.106739. (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Scientific reports, 7(1), p.42717. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Adole, V. A., Kumar, A., Misra, N., Shinde, R. A. & Jagdale, B. S. Synthesis, Computational, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and ADME Study of 2-(3, 4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-4 H-Chromen-4-One pp.1–15 (Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 2023).

- 52.Gangurde, K. B., Adole, V. A. & Ghotekar, D. S. Computational study: Synthesis, spectroscopic (UV–vis, IR, NMR), antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, molecular docking and ADME of new (E)-5-(1-(2-(4-(2, 4-dichlorophenyl) thiazol-2-yl) hydrazineylidene) ethyl)-2, 4-dimethylthiazole. Results in Chemistry, 6, p.101093. (2023).

- 53.Adole, V. A. Computational approach for the investigation of Structural, Electronic, chemical and quantum chemical facets of twelve Biginelli adducts. Organomet. Chem.1 (1), 29–40 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frish, M. J. et al. (2004). Gaussian 03, Revision C. 02, Gaussian. Inc., Wallingford, CT.

- 55.Becke, A. D. Densityfunctional Thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. Doi. 98 (7), 5648–5652 (1993). 10.1063/1.464913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Physical review B, 37(2), p.785. (1988). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Shinde, R. A., Adole, V. A., Shinde, R. S., Desale, B. S. & Jagdale, B. S. Synthesis, antibacterial, antifungal and computational study of (E)-4-(3-(2, 3-dihydrobenzo [b][1, 4] dioxin-6-yl)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl) benzonitrile. Results in Chemistry, 4, p.100553. (2022).

- 58.Raftani, M., Abram, T., Bennani, N. & Bouachrine, M. Theoretical study of new conjugated compounds with a low bandgap for bulk heterojunction solar cells: DFT and TD-DFT study. Results in Chemistry, 2, p.100040. (2020).

- 59.Sharma, D., Tiwari, G. & Tiwari, S. N. Electronic and electro-optical properties of 5CB and 5CT liquid crystal molecules: a comparative DFT study. Pramana, 95(2), p.71. (2021).

- 60.Shinde, R. A. & Adole, V. A. Experimental and theoretical insights into molecular Structure, electronic Properties, and chemical reactivity of (E)-2-((1H-indol-3-yl) methylene)-2, 3-dihydro. J. Appl. Organomet. Chem.1 (2), 48–58 (2021). -1H-inden-1-one. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dennington, R. D. I. I., Keith, T. & Millam, J. GaussView, Version 4.1. 2 (Semichem Inc., 2007).

- 62.Nkungli, N. K. & Ghogomu, J. N. Theoretical analysis of the binding of iron (III) protoporphyrin IX to 4-methoxyacetophenone thiosemicarbazone via DFT-D3, MEP, QTAIM, NCI, ELF, and LOL studies. J. Mol. Model.23, 1–20 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silvi, B. & Savin, A. Classification of chemical bonds based on topological analysis of electron localization functions. Nature371 (6499), 683–686 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Polo-Cuadrado, E. et al. Molecular modeling and structural analysis of some tetrahydroindazole and cyclopentanepyrazole derivatives as COX-2 inhibitors. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 15(2), p.103540. (2022).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.