Abstract

Low-carbon steel freeze pipes, essential refrigerant conduits in artificial ground freezing, are thin-walled cylindrical structures susceptible to buckling and weld failure. This study examined their buckling behavior and critical loads under uniform freezing pressure and shaft sinking-induced displacement using numerical simulations and three-point bending tests at − 32 °C. Results showed that low temperature condition increases nonlinear buckling loads but accelerates post-buckling stiffness degradation. Buckling modes depended on joint type. The critical buckling pressure of jointless freeze pipes was at least 16.39 MPa, while the buckling load of welded-joint freeze pipes exceeded that of jointless pipe sections. Under bending loads, the bending instability of socket welded reinforcement joint freeze pipe (SWRJ) commenced predominantly with ovalization development at the external sleeve, progressing until global structural instability occurred. In contrast, ovalization of internal sleeve butt joint freeze pipe (ISBJ) initiated primarily at the weld seam in the mid-span region of the parent pipe. SWRJ and ISBJ specimens exhibited comparable critical bending moments at diameter-to-thickness ratios of 26–28, but SWRJ specimens exceeded ISBJ specimens outside this range. Based on bending instability analysis, a maximum allowable deflection of one-third of the pipe diameter is recommended for engineering safety.

Keywords: Freeze pipe, Low temperature, Buckling, Welded joint, Bending instability

Subject terms: Energy science and technology, Engineering, Materials science

Introduction

With the strategic shift of China’s coal mine construction focus towards the western regions, the adoption of artificial ground freezing (AGF) technology to mitigate water inrush risks during shaft sinking has become a preferred method for deep vertical shaft construction1–4. To date, China has successively overcome the key technologies for freezing shaft sinking through extra-thick soil layers (400 m to 800 m) and deep water-rich rock formations (500 m to 1000 m)5.

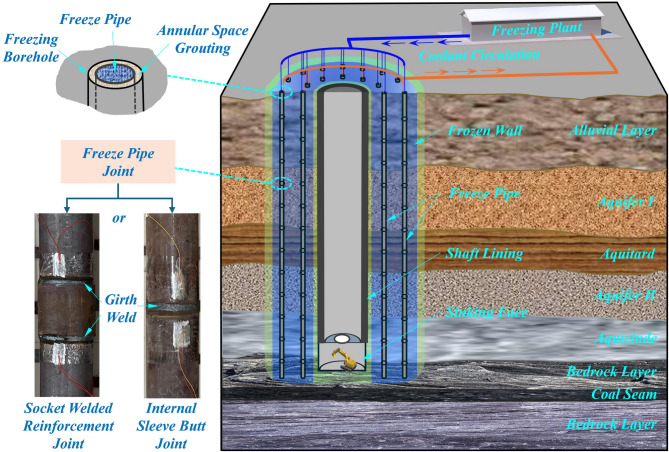

In coal mine freezing shaft sinking projects, AGF technology primarily utilizes low-carbon steel pipes (hereinafter referred to as freeze pipes) with diameters ranging from 140 mm to 159 mm as the circulation channels for the refrigerant. A schematic diagram of the main system components is shown in Fig. 1. Manufactured as seamless steel tubes in segments of 10 m to 20 m in length, these freeze pipes are lowered segmentally into the freeze holes and are joined into continuous strings using either socket-welded reinforcement joints or internal sleeve butt joints. Upon completion of the pipe string installation, the annular space between the freeze pipe and the borehole wall is grouted for stabilization. The properties of grouting materials, such as long-term strength, volume stability, and bonding strength with the shaft wall, directly affect the lateral support effectiveness to freeze pipes and consequently influence their overall stability. The application of some novel grouting materials is of significant importance for securing freeze pipes and sealing hydraulic connections between aquifers and impermeable layers6–8. Characterized by a diameter-to-thickness ratio typically between 20 and 40, the freeze pipes represent classic thin-walled structures. They must withstand significant loads, particularly during the construction of deep coal mine vertical shafts (exceeding 500 m depth). Furthermore, they are subjected to complex combined loading conditions, encompassing: high geostatic pressure (> 15 MPa), intense freezing pressure (> 10 MPa), extremely low ambient temperatures (below − 30℃), and shaft wall displacement near the excavation face. Under these demanding conditions, freeze pipes are susceptible to failures such as flattening, cracking at welded joints, or seal failure. Such failures can lead to critical incidents like brine leakage, ultimately determining the success or failure of the entire freezing project. Consequently, investigating the influence of connection joint type, ambient temperature, and stiffness discontinuity on the mechanical performance of freeze pipes is essential for their parametric design. This study focuses on these critical aspects, which are crucial for ensuring the safety of freezing projects.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the artificial ground freezing method for deep vertical shafts in coal mines.

Current research on the buckling instability of thin-walled tubular structures predominantly focuses on pressure vessel applications such as subsea and oil pipelines. Guo et al.9 reported that the global buckling response of buried subsea pipelines under temperature differentials is highly sensitive to initial imperfections, with both the buckling mode and triggering load being significantly affected. Through tests on large-diameter spiral-welded steel pipes, Van Es et al.10 demonstrated that pipes with a diameter-to-thickness ratio exceeding 100 are highly susceptible to local instability. This instability manifests as cross-sectional ovalization and wrinkling on the compression side, accompanied by stiffness degradation and a sudden drop in the moment-curvature response. Employing nonlinear finite element analysis (FEA), Vasilikis et al.11 further revealed that larger diameter-to-thickness ratios lead to more severe warping deformation (distortion) and local buckling. Additionally, they identified that welding residual stresses and geometric imperfections have an amplifying effect during the buckling failure process. Liu et al.12 established a nonlinear pipe-soil interaction model, investigated subsea pipeline buckling. Their study indicated that soil support stiffness and interface friction significantly influence the critical buckling behavior of thin-walled pipes and demonstrated that external boundary conditions exert a controlling effect on the instability process of thin-walled structures. Wang et al.13 experimentally investigated the buckling evolution of stiffened cylindrical shells under coupled non-uniform external pressure and axial compression. Their study revealed that the level of axial compression significantly influences the shell buckling mode and quantitatively characterized the triggering mechanism for mode-jumping behavior. Liu et al.14 analyzed the warping deformation characteristics of slender pipes induced by girth welded joints. Their study revealed that welding heat input and the non-uniform distribution of axial residual plastic strain are the primary drivers of local bending and cross-sectional distortion. Zhang et al.15 investigated the lateral buckling behavior of casing systems subjected to non-uniform buoyancy forces. They proposed that strategically deploying support structures can induce controlled buckling, demonstrating that the buckling of thin-walled pipes depends not only on intrinsic geometric parameters but is also governed by the distribution pattern of external support conditions. Su et al.16 emphasized that geometric imperfections such as initial ovality and local dents govern the ultimate bearing capacity of pipes susceptible to local buckling. Particularly under combined loading (external pressure + bending moment), these imperfections can induce buckling mode transformation and reduce the critical pressure. Tian et al.17 developed a predictive model based on Timoshenko beam theory to assess the influence of corrosion defects on collapse pressure. Their model elucidates how geometric defect factors—including defect shape coefficient and local thinning depth—degrade the stability of thin-walled cylinders, compromising their load-bearing integrity. Liu et al.18 employing eigenvalue buckling analysis, found that uniform erosion reduces the critical load of thin-walled pipes, whereas stochastic pitting corrosion in certain forms may paradoxically enhance local structural stability. This indicates that the buckling performance of thin-walled pipes exhibits nonlinear response characteristics under specific defect conditions.

Research related to the bending behavior of thin-walled tubular structures primarily focuses on aspects such as failure modes, energy absorption capacity, and load-bearing capacity optimization. Guo et al.19 through three-point bending experiments and numerical simulations, investigated the bending behavior of double cylindrical tubes filled with aluminum foam. They discovered that the double-tube structure exhibits more stable load-bearing capacity, higher bending resistance, and superior specific energy absorption (SEA) efficiency compared to empty tubes and single aluminum foam-filled tubes. Lai et al.20 systematically studied the defect sensitivity of medium-density polyethylene (MDPE) fusion-welded joints using tests including tensile, burst, and three-point bending. Their study findings indicate that defects with sizes smaller than 15% of the pipe wall thickness do not compromise joint integrity under static bending loads. However, under fatigue loading, even minute defects significantly accelerate failure initiation. Hu et al.21 conducted quasi-static lateral three-point bending tests on aluminum tubes, correlated with simulations. Their analysis revealed that the tube’s failure process evolves through three distinct stages: initial pure buckling, buckling-bending coupling, culminating in structural fracture. Additionally, tubes with short span lengths and high diameter-to-thickness ratios were found to possess high energy absorption characteristics. He et al.22 proposed four types of circular tubes reinforced with stiffening ribs. Employing three-point bending simulations and COPRAS evaluation, they demonstrated that the ribs significantly enhance the tubes’ bending resistance. Furthermore, a monotonic positive correlation was observed between bending resistance and both the rib-to-wall thickness ratio and the indenter size. Song et al.23 established an accurate mechanical model for the symmetric three-point bending straightening of large-diameter pipes by incorporating a bilinear hardening model and a die parameter correction theory. Their model revealed a linear mapping relationship between indenter stroke and springback deflection.

In summary, existing research has predominantly focused on the influence of factors such as initial imperfections, geometric defects, residual stresses, complex boundary conditions, and non-uniform loading on the instability of thin-walled pipes. This study addresses a critical gap by focusing on the two most adverse operational conditions for freeze pipes during coal mine freezing shaft construction: (1) high uniform external pressure during deep shaft freezing, and (2) bending stresses induced by sinking under the low-temperature condition. Corresponding mechanical models are established for these conditions, and numerical methods are employed to compute the critical buckling load under uniform external pressure. Furthermore, through extensive low-temperature bending tests on numerous welded joint specimens, the bending instability of freeze pipes is statistically analyzed. This integrated approach elucidates the stability characteristics of freeze pipes under the combined influence of multiple factors, including low-temperature material embrittlement, alterations in structural geometric parameters, and variations in joint connection types.

Mechanical model

Structural characteristics

Classical shell buckling theory24 indicates that the low-carbon steel freeze pipes employed in engineering practice represent typical long cylindrical thin-walled structures. Considering the critical length for establishing their mechanical model, a pipe segment of length 1000 mm can be reasonably approximated for mechanical analysis. The critical length  is defined as:

is defined as:

|

1 |

where  is the critical length; D is the diameter of the thin-walled cylindrical structure; and t is the effective wall thickness of the thin-walled cylindrical structure.

is the critical length; D is the diameter of the thin-walled cylindrical structure; and t is the effective wall thickness of the thin-walled cylindrical structure.

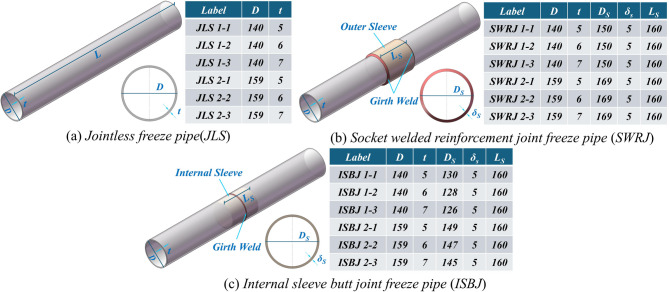

Figure 2 illustrates the geometric models of freeze pipes and their connection segments commonly used in deep vertical shaft freezing projects in China. These can be categorized into three structural types: Fig. 2a depicts a jointless freeze pipe (JLS); Fig. 2b shows a socket welded reinforcement joint freeze pipe (SWRJ), featuring an external sleeve; Fig. 2c presents an internal sleeve butt joint freeze pipe (ISBJ), featuring an internal sleeve. In the figure,  denotes the diameter of the external sleeve (for SWRJ) or the internal sleeve (for ISBJ);

denotes the diameter of the external sleeve (for SWRJ) or the internal sleeve (for ISBJ);  represents the thickness of the external sleeve or the internal sleeve; and

represents the thickness of the external sleeve or the internal sleeve; and  signifies the length of the external sleeve or the internal sleeve.

signifies the length of the external sleeve or the internal sleeve.

Fig. 2.

Structural characteristics of freeze pipes.

Model loading condition I: uniform freezing pressure

In coal mine freezing shaft sinking projects, after freeze pipes are lowered into the borehole and grouted for stabilization, the formation pressure acting on the pipe prior to freezing induces initial deformation. As freezing commences and before strata excavation begins, the dominant pressure acting on the freeze pipes gradually transitions to freezing pressure. This freezing pressure arises from the superposition of virgin in-situ stress and frost heave stress, where the latter is generated by constrained volumetric expansion during water-ice phase change in subsurface formations. Horizontally, the frozen stratum experiences strong confinement from adjacent unfrozen strata, restricting dilatational deformation. With increasing depth, the geostatic stress rises, intensifying the frost heave confinement effect. Consequently, the freezing pressure in the horizontal direction becomes the primary load sustained by the freeze pipes (see Fig. 3). This is particularly significant in silt and high-water-content cohesive strata, where the frost heave ratio can exceed 25%, and the frost heave pressure may reach approximately 1.5 times the virgin in-situ stress.

Fig. 3.

Mechanical model of freeze pipe under frost heave stress.

For the entire freezing curtain, the designed thickness of the frozen wall typically ranges from 1.5 to 3.5 m. Due to variations in formation conditions such as water content and lithology, the distribution of freezing pressure is inherently non-uniform. Its distribution characteristics are influenced by the coupling effects of multiple factors, including geological conditions, the layout of freeze holes, and the propagation efficiency of the freezing temperature field. However, at the scale of an individual freeze pipe segment—where pipe diameter and length are negligible relative to both curtain thickness and freezing system length—the geostatic stress field approximates uniform radial pressure. Similarly, the frost heave stress, distributed concentrically around the pipe axis, can also be treated as a uniform stress field.

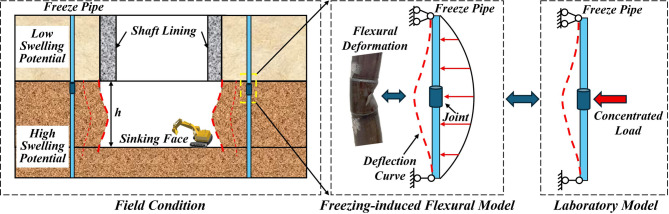

Model loading condition II: bending moment induced by shaft sinking

Following completion of the ground freezing process around the shaft, the construction phase progresses to the shaft sinking stage. During the sinking period, heat exchange occurs between the exposed frozen wall face (acting as the temporary shaft support prior to permanent lining installation) and the ventilation airflow. This heat transfer causes the temperature of the frozen wall to rise and its strength to decrease, resulting in displacement of the frozen wall face. This displacement, in turn, alters the stress field surrounding the freeze pipes. Typically, greater magnitudes of virgin in-situ stress and frost heave pressure lead to larger displacements of the frozen wall face induced by stress release during excavation. Concurrently, a larger designed excavation lift height and longer exposure time of the frozen wall face exacerbate this displacement.

When significant displacement of the frozen wall face occurs, the freeze pipes are subjected to corresponding bending loads. These loads readily induce cracking at welded joints and can even lead to pipe fracture, subsequently causing leakage of the refrigerant. Field experience25 confirms that clay strata with high swelling potential and the interfaces between these clay layers and the adjacent geotechnical strata are the horizons where weld cracking and pipe fracture in freeze pipes are most prevalent during shaft sinking operations (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of partial freeze pipes failure accidents.

| No. | Mine name | Accident situation | Failure stratum | Stratigraphic horizon/m |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | Zaporizhzhia Mine No.1 South Ventilation Shaft | Failure of 28 freeze pipes | Clay stratum | 143 ~ 265 |

| 2# | Yakovlev Iron Mine | Failure of 15 freeze pipes | Clay stratum | 308 ~ 407 |

| 3# | Xieqiao Coal Mine Gangue Shaft | Failure of 34 freeze pipes | Clay stratum | 224 ~ 238 |

| 4# | Xieqiao Coal Mine Auxiliary Shaft | Failure of 32 freeze pipes | Clay stratum | 230 ~ 239 |

| 5# | Panji No.3 Coal Mine East Ventilation Shaft | Failure of 22 freeze pipes | Clay-sandstone interface | 252 ~ 326 |

| 6# | Yangcun Coal Mine Auxiliary Shaft | Failure of 15 freeze pipes | Clay stratum | 404 ~ 412 |

| 7# | Panji No.2 Coal Mine South Ventilation Shaft | Failure of 14 freeze pipes | Clay-sandstone interface | 153 ~ 173 |

A simplified mechanical model representing the bending load on freeze pipes induced by shaft sinking is established, as illustrated in Fig. 4. In the figure, h denotes the excavation lift height. Therefore, the three-point bending test is adopted in the laboratory to evaluate the bending resistance performance of the freeze pipe structures.

Fig. 4.

Simplified mechanical model of freeze pipe under bending load.

Buckling characteristics under uniform external pressure

Numerical simulation method

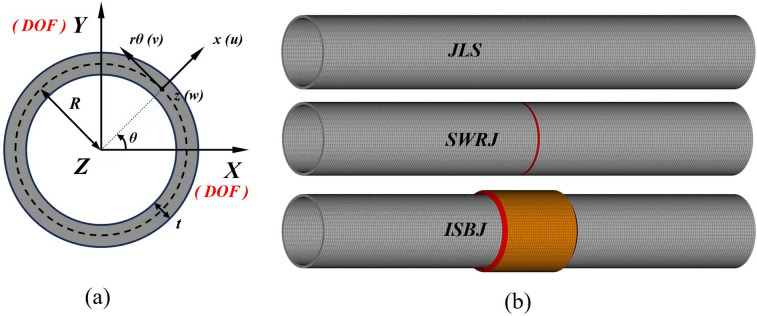

Numerical simulations of the buckling performance of thin-walled, long cylindrical freeze pipes were conducted using ANSYS Mechanical APDL. The 20-node hexahedral 3D solid element SOLID186 was selected for modeling. The element mesh size was set to half of the pipe wall thickness (see Fig. 5). Contact interfaces between the external sleeve/internal sleeve and the parent pipe were defined with CONTA174-TARGE170 pairs using MPC (Multi-point Constraint) bonded algorithm to simulate rigid connections.

Fig. 5.

Finite element model of freeze pipes: (a) constraint configuration, (b) mesh generation.

For the thin-walled steel pipes, the relatively small wall thickness of the freeze pipes results in an approximately uniform, steady-state temperature distribution. Consequently, the influence of temperature gradients can be neglected. Wang et al.26 demonstrated that 20# low-carbon steel exhibited significantly increased brittleness at low temperatures. Its elastic modulus showed a slight increase, and its yield strength had increased by about 15% to 30% compared to room temperature. However, due to the use of steel pipes that had been affected by adverse environments after service, the increase in yield strength at low temperature was taken as about 30%. Furthermore, due to the selection of welding seam materials in accordance with the principle of equal strength design, their material properties were superior to the base metal27, and considering the influence of impurities, the increase in yield strength of the welding seam was taken as 15%. The material parameter values used in the simulations are listed in Table 2. Simply supported constraints permitting rotation were applied at both ends of the model28. Uniform radial external pressure was applied to solve for both the linear and nonlinear buckling critical loads.

Table 2.

Main mechanical parameters for numerical simulation (25 °C/− 32 °C).

| Material | T (℃) | ρ (kg/m3) | α(C− 1) | E (GPa) | ν | ReL (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pipe metal (20#) | 25 | 7850 | 1.2e−5 | 200 | 0.3 | 245 |

| Deposited metal (J422) | 25 | 7850 | 1.2e−5 | 200 | 0.3 | 330 |

| Pipe metal (20#) | − 32 | 7850 | 1.18e−5 | 205 | 0.3 | 320 |

| Deposited metal (J422) | − 32 | 7850 | 1.18e−5 | 205 | 0.3 | 380 |

Eigenvalue buckling

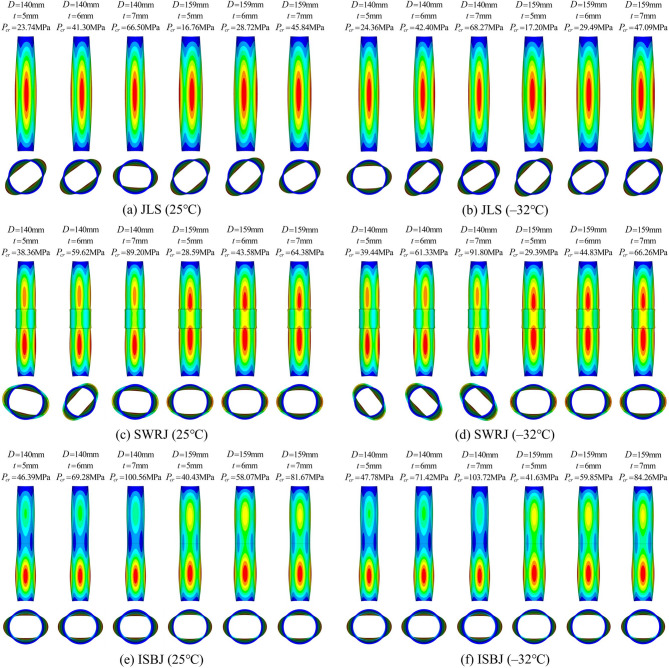

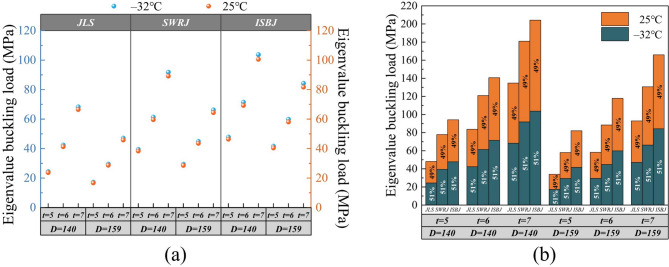

The first-order eigenvalue buckling modes and critical buckling loads for all three structural types of freeze pipe models at temperatures of 25 °C and − 32 °C were obtained through numerical simulations. These results are presented in Fig. 6 (display scale factor: × 20). A comparison of the critical buckling loads under various parametric conditions is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 6.

First-order eigenvalue buckling mode.

Fig. 7.

Eigenvalue buckling load: (a) at different temperatures, (b) under different joint types.

Analysis of the buckling modes in Fig. 6 reveals a consistent axisymmetric circumferential two-wave (n = 2) ovalization pattern across all models. This primary mode demonstrated remarkable robustness, remaining unchanged despite variations in temperature and wall thickness within the studied range. However, a key finding is the pronounced disturbance effect induced by the local stiffness discontinuity at the joints of the SWRJ and ISBJ structures. This disturbance caused the parent pipe segment adjacent to the joint to undergo buckling instability prior to other regions. Furthermore, comparative analysis indicates that an increase in pipe diameter significantly amplifies this detrimental effect of joint stiffness discontinuity.

The parametric influences on eigenvalue buckling loads, compared in Fig. 7, show several clear trends. The critical load increases monotonically with wall thickness but decreases significantly with increasing pipe diameter. In contrast, the effect of temperature variation within the studied range was marginal, with a maximum observed magnitude of only 2.6%. Most notably, the joint designs significantly enhanced buckling stability. Compared to the JLS baseline, the SWRJ structure improved the buckling load by 34.14–70.61%, while the ISBJ structure demonstrated a more substantial enhancement of 51.22–141.26%.

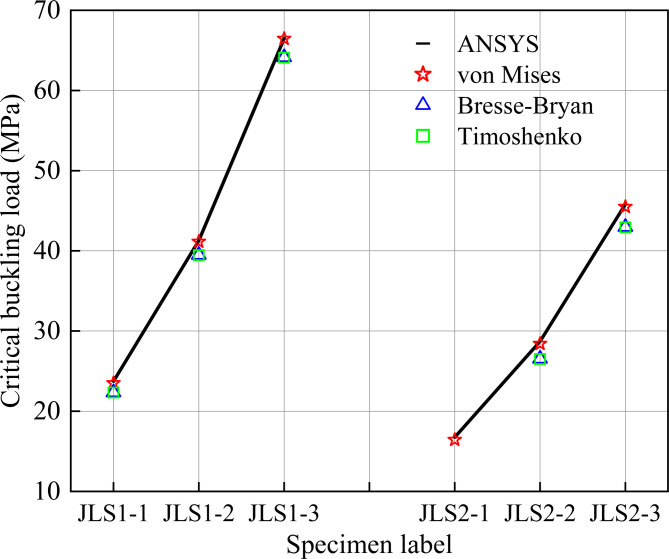

The classical theoretical analytical solution for the critical buckling load of cylindrical shells under external pressure (see Table 3)24,29,30 were adopted for comparative analysis with the numerical solutions. The graphical analysis of this comparative data is shown in Fig. 8.

Table 3.

Critical buckling load formula of classical buckling theory.

Fig. 8.

Error analysis of eigenvalue buckling predictions.

where E is the elastic modulus of the material; ν is the Poisson’s ratio of the material; L is the length of the cylindrical shell; t is the thickness of the cylindrical shell; R is the radius to the neutral surface of the cylindrical shell; D is the diameter of the cylindrical shell; n is the circumferential buckling wave number.

The computational results demonstrate that for ideal cylindrical shells, the maximum deviations between the numerical solutions and the three theoretical solutions are 1.06%, 6.04%, and 6.15%, respectively. This close agreement confirms the high reliability of the numerical simulation methodology. Consequently, the first-order eigenvalue buckling modes obtained from the simulations can be introduced as initial geometric imperfections in subsequent nonlinear buckling analyses.

Nonlinear buckling

Analysis method

Nonlinear buckling analysis captures the degradation trend of structural post-buckling stiffness, abrupt turning points in load-displacement paths, and the competition and transition phenomena among multiple instability modes. A critical step in this analysis involves introducing the buckling eigenmode as a geometric imperfection31–33, which enables the structure to trigger and trace the nonlinear post-buckling response path without the need for methods of perturbation to neighboring point or load disturbance34,35. For cylindrical shells, initial geometric imperfections are modeled by introducing a normalized buckling mode displacement vector expressed as:

|

5 |

where  is the initial geometric imperfection field;

is the initial geometric imperfection field;  is the normalized asymmetric buckling mode displacement vector obtained from eigenvalue analysis;

is the normalized asymmetric buckling mode displacement vector obtained from eigenvalue analysis;  is the imperfection amplitude factor controlling the deviation magnitude from the perfect geometry.

is the imperfection amplitude factor controlling the deviation magnitude from the perfect geometry.

After introducing geometry-imperfect initial defects with specific amplitudes based on the eigenvalue buckling mode, the post-buckling path characteristics exhibited during quasi-static loading are characterized by the morphology of the load-displacement response curve. The nonlinear buckling load is identified and extracted at the critical point where significant nonlinear stiffness attenuation occurs in this response curve. This critical point represents the instability threshold at which the structure transitions from a stable equilibrium state to a post-buckling state.

In the nonlinear buckling analysis, tracing complex equilibrium paths necessitates an incremental-iterative solution strategy. While the standard Newton-Raphson method is commonly employed, it faces significant convergence challenges near critical buckling points, often failing to stably traverse these critical regions and capture complete post-buckling response paths. To overcome these limitations and enhance the continuity of the solution results during nonlinear path tracing, this study implemented the arc-length method36,37 as the path-following control strategy. Furthermore, given the sensitivity of thin-walled cylindrical structures to material parameters—particularly hardening characteristics—a penalized adjustment was applied to the elastic modulus during the isotropic hardening phase within the pipe’s plastic constitutive model. This conservative adjustment enhances engineering safety margins in buckling load assessments and mitigates potential path drift phenomena induced by uncertainties in material hardening parameters.

Simulation results

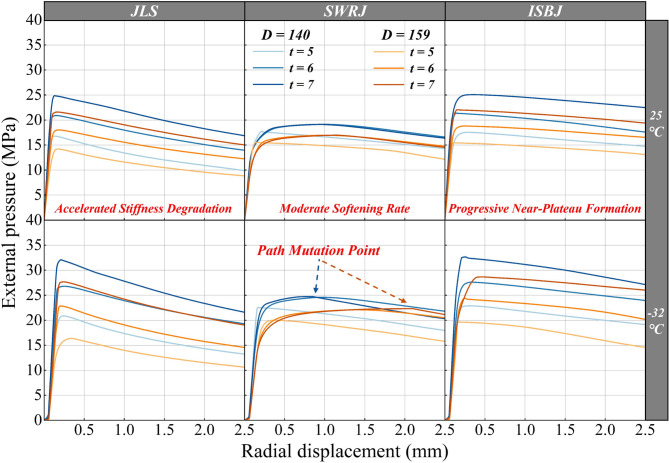

Nonlinear buckling modes of the freeze pipe models under various parametric conditions are presented in Fig. 9 (display scale factor: ×10). Corresponding nonlinear buckling paths are shown in Fig. 10, while comparative assessments of nonlinear buckling loads are shown in Fig. 11.

Fig. 9.

Nonlinear buckling mode.

Fig. 10.

Nonlinear buckling path.

Fig. 11.

Nonlinear buckling load: (a) at different temperatures, (b) under different joint types.

The buckling modes in Fig. 9 reveal distinct buckling mechanisms for each structure. The JLS structure exhibits classical circumferential two-wave ovalization. In contrast, the ISBJ structure manifests an asymmetric two-wave buckling pattern localized to one side, a tendency that intensifies with a decreasing diameter-to-thickness ratio. The buckling behavior of the SWRJ structure, however, is predominantly governed by the stiffness gradient discontinuity at its joint. For thin-walled conditions, buckling initiates in the parent pipe body as unilateral two-wave buckling. Under higher wall thickness conditions, the buckling locus shifts to the central zone of the external sleeve, triggering a transition to higher-order circumferential multi-lobe buckling modes (n = 4, 6).

Through parameter analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn: (1) The low-temperature environment significantly enhances nonlinear buckling loads of freeze pipes but accelerating their post-buckling stiffness degradation rate. Compared to ambient conditions (25℃), at − 32℃: The JLS structure exhibits 15.3–29.2% higher nonlinear buckling loads; the SWRJ structure shows 26.6–31.4% increase; the ISBJ structure demonstrates 27.1–30.3% elevation. (2) Nonlinear buckling loads increase with decreasing diameter-to-thickness ratio for all three structural types of freeze pipe models. (3) The SWRJ structure outperforms the JLS structure only at minimum wall thickness (t = 5 mm). Under other parametric conditions, SWRJ structure demonstrates lower nonlinear buckling loads than JLS structure, with this performance gap widening as wall thickness increases. This phenomenon is attributed to modal transition effects under increased wall thickness conditions, where stiffness discontinuity at the external sleeve alters the inherent load transfer path. This shifts buckling modes from circumferential two-wave buckling of parent pipe body to localized higher-order buckling modes dominated by the socket joint. (4) The nonlinear buckling instability point of the ISBJ structure occurs at an earlier stage, with the buckling initiation located at the parent pipe body. However, it exhibits a higher nonlinear buckling load and superior post-buckling residual load-carrying capacity.

Bending performance in three-point bending

Test method

Following completion of the ground freezing process around the shaft, bending instability of freeze pipes emerges as a primary risk during shaft sinking stage38. The critical bending moment ( )—defined as the maximum moment capacity before instability—serves as the fundamental basis for designing freeze pipe parameters and optimizing excavation lift heights. In engineering applications, freeze pipes exhibit substantial variability in critical bending moments due to differences in temperature conditions, pipe dimensions, joint types, and welding techniques. Therefore, sampling tests should be performed on freeze pipes prior to the initiation of freezing engineering projects to evaluate structural bending performance and weld quality. This testing protocol constitutes the primary quality control measure for freeze pipes in China’s artificial ground freezing construction practice.

)—defined as the maximum moment capacity before instability—serves as the fundamental basis for designing freeze pipe parameters and optimizing excavation lift heights. In engineering applications, freeze pipes exhibit substantial variability in critical bending moments due to differences in temperature conditions, pipe dimensions, joint types, and welding techniques. Therefore, sampling tests should be performed on freeze pipes prior to the initiation of freezing engineering projects to evaluate structural bending performance and weld quality. This testing protocol constitutes the primary quality control measure for freeze pipes in China’s artificial ground freezing construction practice.

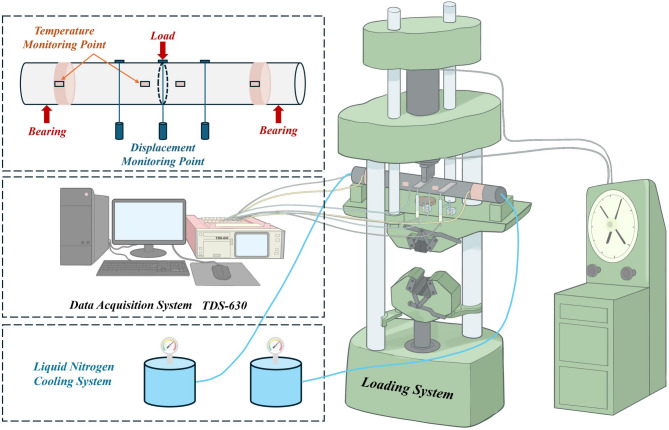

Three-point bending tests were conducted on 1000-mm-long thin-walled low-carbon steel pipe specimens under a low temperature condition. Concentrated loads were applied until fracture or bending instability occurred, followed by analysis of the bending capacity39 and deflection characteristics of the freeze pipes. The test system is shown in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Three-point bending test system of freeze pipes.

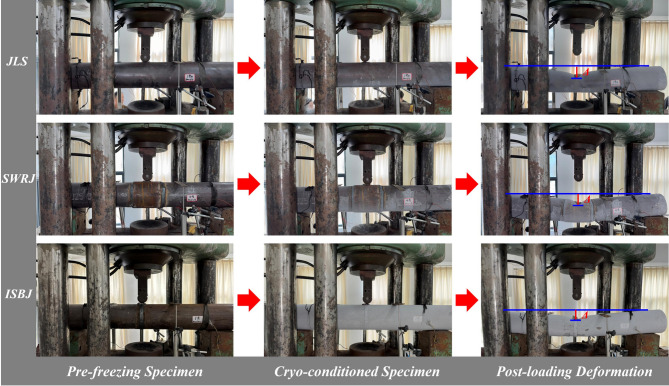

Prior to testing, deflection measurement aids were implemented by welding steel sheets at three locations: the specimen midspan and 200 mm offset from midspan. Both pipe ends were then sealed, and liquid nitrogen was uniformly injected through reserved ports to achieve target temperatures. During testing, temperature data from monitoring points were tracked in real-time. Loading commenced when primary thermocouples reached the low temperature condition of − 32 ± 2 °C, with loading rates controlled at 1–2 kN/s. Liquid nitrogen was periodically replenished based on thermal field evolution to maintain the low-temperature environment throughout loading. The test procedure is shown in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Three-point bending test procedure for freeze pipes.

Analysis of test results

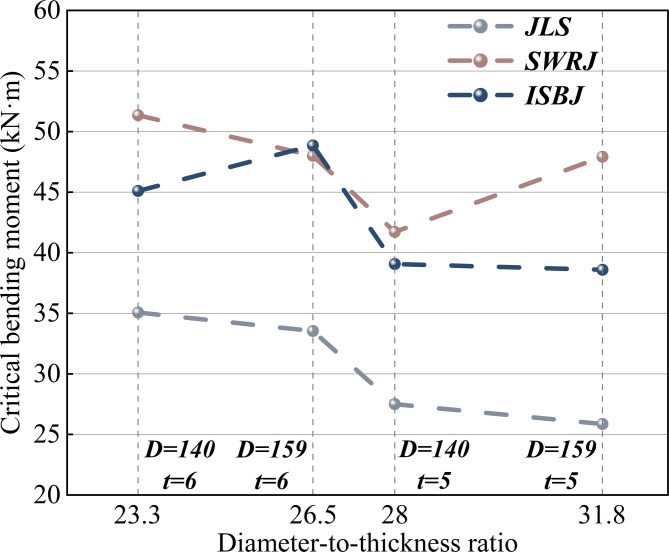

Three-point bending tests under the low temperature condition were conducted on 211 freeze pipes sampled from 37 vertical shaft freezing projects in China. Characteristic moment-midspan deflection curves were obtained for three types of structure: JLS, SWRJ, and ISBJ (see Fig. 14). The critical bending moments and mid-span deflections of all specimens were statistically analyzed, with mean values at a 95% confidence level presented in Fig. 15.

Fig. 14.

Representative schematic of bending moment vs. mid-span deflection.

Fig. 15.

Three-point bending performance of freeze pipes.

The bending failure of freeze pipes followed a nonlinear structural degradation process comprising four distinct phases: (1) Linear elastic stage: Moment-deflection relationship remained linear, with pipe cross-sections retaining circular geometry. (2) Initial ovalization stage: When the load reaches 35–45% of the peak load, indentation first occurred at the loading points, accompanied by initial ovalization of local pipe cross-sections. As the load increases, the pipe walls gradually concaved inward locally. (3) Large-deflection stage: Beyond 45% peak load, ovalized regions propagated rapidly. The structural deformation accelerated with increasing curvature rates. (4) Catastrophic instability stage: Upon exceeding critical deflection thresholds, abrupt bending capacity loss occurred and may be accompanied by the initiation of fracture cracks at pipe walls and weld seams.

The statistical analysis of the test data, presented in Fig. 15, yielded several key findings regarding the bending performance of the freeze pipe specimens: (1) The test data for the critical bending moment of the JLS specimens exhibited significantly less variability than that of the SWRJ and ISBJ specimens. Since the specimens with external sleeve and those with internal sleeve originated from different engineering projects and were manufactured using low-carbon steel pipes from different production batches, inevitable variations in their mechanical properties existed. These variations were also influenced by the on-site welding quality. Consequently, the confidence intervals for the mean values of their test data overlapped. Nevertheless, the data demonstrated unequivocally that the mean critical bending moment for both types of specimens with welded joints exceeded that of the JLS specimens. Specifically, the SWRJ specimens exhibited an increase of more than 46.4% compared to the JLS specimens, while the ISBJ specimens showed an increase of more than 28.6%. This is attributed to the fact that both types of welded joint specimens enhance their bending stiffness by increasing the bending section modulus. (2) The critical bending moment versus mid-span deflection relationship curves of the SWRJ and ISBJ structures displayed significant differences. The ISBJ structure demonstrated higher intermediate stiffness but exhibited poorer ductility compared to the SWRJ structure. In contrast, the SWRJ structure possessed greater bending stiffness in the linear elastic stage due to the presence of a larger-diameter additional stiffening ring. Furthermore, at the joint of the SWRJ structure, the external sleeve constrained the bending deformation of the parent pipe, and the weld restricted its axial slippage, creating a plastic hinge constraint effect39. This resulted in more pronounced plastic characteristics in the critical bending moment versus mid-span deflection curve of the SWRJ structure. (3) The mid-span deflection data for all three structures showed considerable variability. The confidence intervals for the mean mid-span deflection values of each structure overlapped. Therefore, quantitatively evaluating the differences in the experimentally obtained mid-span deflection results was challenging. However, three-point bending tests on freeze pipe specimens with welded joints indicated that fracture occurs only after the mid-span deflection exceeded one-third of the freeze pipe diameter. Consequently, it is recommended that D/3 be adopted as the allowable maximum deflection for freeze pipes in engineering practice.

Representative fractured specimens after low-temperature (− 32 °C) bending instability are displayed in Fig. 16. Unlike the weld-free JLS specimens, the low temperature environment specifically induced embrittlement at the welded joints of these specimens, with weld seams serving as the primary crack initiation sites following bending instability. Among 166 welded-joint freeze pipe specimens that reached instability, 34 fractured, constituting approximately 20.5% of the total specimens with welded joints. Combining this phenomenon with the data analysis in Fig. 17, it can be concluded that: (1) The critical bending moments of the JLS specimens gradually decreased with increasing diameter-to-thickness ratio. Structural bending instability typically occurred at the cross-section subjected to the maximum bending moment in the mid-span region. (2) Due to differences in structural configuration, the bending instability characteristics of freeze pipe specimens with welded joints differed from those of the JLS specimens. For SWRJ structure, bending instability commenced predominantly with ovalization development at the external sleeve, progressing until global structural instability occurred, with cracks generally initiating at welds and the external sleeve. In contrast, for ISBJ structure, ovalization initiated primarily at the weld seam in the mid-span region of the parent pipe, where cracks primarily originated from welds and the parent pipe body. (3) Within the diameter-to-thickness ratio range of 26.5–28, the critical bending moments of SWRJ and ISBJ specimens were comparable, exhibiting approximate bending performance. However, outside this specific range, the critical bending moments of the SWRJ specimens exceeded that of the ISBJ specimens.

Fig. 16.

Bending instability characteristics of freeze pipe specimens with welded joints.

Fig. 17.

Relationship between critical bending moment and diameter-to-thickness ratio.

Conclusions

Addressing the instability of freeze pipes in deep coal mine shafts influenced by low temperature and joint types, this study systematically analyzed the mechanical response characteristics of thin-walled steel pipe structures under two working conditions: uniform freezing pressure and three-point bending loads. The presented results allow the following conclusions to be drawn:

Under uniform freezing pressure, the low-temperature environment (–32℃) did not significantly alter the eigenvalue buckling modes of the freeze pipes. However, it elevated the nonlinear critical buckling load and accelerated post-buckling stiffness degradation. Excluding weld defects, the critical freezing pressure for buckling of jointless freeze pipes was no less than 16.39 MPa. Due to the reinforcement effect of the external sleeve and internal sleeve, the buckling load of welded-joint freeze pipes exceeded that of jointless pipe sections. Compared to room temperature (25℃), the nonlinear buckling load at − 32℃ increased by over 15.3%.

Different joint types significantly affected buckling characteristics and critical bending moments. Under uniform freezing pressure, ISBJ structure initiated buckling at the parent pipe body, whereas SWRJ structure transitioned from circumferential two-wave buckling under thin-wall conditions to localized higher-order modes under thicker wall conditions. When the freeze pipes were subjected to bending loads, the bending instability of SWRJ structure commenced predominantly with ovalization development at the external sleeve, progressing until global structural instability occurred. In contrast, ovalization of ISBJ structure initiated primarily at the weld seam in the mid-span region of the parent pipe. SWRJ and ISBJ specimens exhibited comparable critical bending moments at diameter-to-thickness ratios of 26–28, but SWRJ specimens exceeded ISBJ specimens outside this range.

Under bending loads simulating frozen wall displacement during shaft sinking, the SWRJ specimens exhibited preferential cracking at weld seams and external sleeve interfaces, whereas the ISBJ specimens primarily fractured at the weld seams and parent pipe. Based on the bending instability analysis, a maximum allowable deflection of one-third of the pipe diameter is recommended to ensure engineering safety.

Notwithstanding these findings, the current study has certain limitations that warrant further investigation. Specifically, the group piping effect during multi-circle freezing under practical engineering conditions requires particular attention. Moreover, experimental validation was constrained by the application of concentrated loads, which may affect the deflection curves of freeze pipes after bending and introduce deviations from actual engineering behavior. Additionally, the interaction between freeze pipes and frozen soil necessitates more sophisticated modeling approaches to accurately characterize interfacial stress transmission and mechanical behavior. These limitations highlight that the development of a thermo-mechanical coupling model incorporating the group piping effect represents a crucial direction for future research aimed at analyzing the complex interactions between freeze pipes and frozen soil.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Anhui Province (Natural and Science) (No. 2022AH050815) and Anhui Province New Era Education Quality Improvement Project (Postgraduate Education) (No.2024qygzz022). The authors also wish to acknowledge the organizations that have supported this basic research.

Author contributions

H.Z.: Writing-original draft preparation, visualization, software, data curation, investigation, formal analysis. M.L.: Writing-review and editing, data curation, methodology, conceptualization, visualization, supervision, funding acquisition. B.X.: Visualization, supervision. C.R.: Writing-review and editing, methodology, supervision. Y.Q.: Project administration, resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Anhui Province (Natural and Science) (No. 2022AH050815) and Anhui Province New Era Education Quality Improvement Project (Postgraduate Education) (No. 2024qygzz022).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pilecki, Z. et al. Temperature anomaly as an indicator of groundwater flow prior to the shaft sinking with the use of artificial ground freezing. Eng. Geol.34710.1016/j.enggeo.2025.107916 (2025).

- 2.Li, Z. et al. Determination of the hydrodynamic condition in artificial ground freezing based on multi-field coupling theory. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 5910.1016/j.tsep.2025.103307 (2025).

- 3.Jia, J., Zhang, X., Sun, P. & Zou, B. Unloading strength and damage properties of deep frozen clay subjected to long-term high-pressure K0 consolidation. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energ Geo-resour. 1110.1007/s40948-025-00984-w (2025).

- 4.Wang, Y., Cao, Y., Zhao, M. & Chen, E. The indoor experimental method for the microseismic issue of freezing pipe fracture and its effectiveness verification. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol.23910.1016/j.coldregions.2025.104573 (2025).

- 5.Yang, W. et al. Development and prospect of shaft freeze wall technology in China. J. China Coal Soc.50, 92–114. 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2024.1522 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu, J. et al. Microscopic mechanism of cellulose nanofibers modified cemented gangue backfill materials. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater.810.1007/s42114-025-01270-9 (2025).

- 7.Wu, J. et al. Effect of composite alkali activator proportion on macroscopic and microscopic properties of gangue cemented rockfill: experiments and molecular dynamic modelling. Int. J. Min. Metall. Mater.32, 1813–1825. 10.1007/s12613-025-3140-8 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu, J. et al. Improvement of cemented rockfill by premixing low-alkalinity activator and fly ash for recycling gangue and partially replacing cement. Cem. Concrete Compos.145, 105345. 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.105345 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo, L., Liu, R. & Yan, S. Global buckling behavior of submarine unburied pipelines under thermal stress. J. Cent. South. Univ.20, 2054–2065. 10.1007/s11771-013-1707-4 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Es, S. H. J., Gresnigt, A. M., Vasilikis, D. & Karamanos, S. A. Ultimate bending capacity of spiral-welded steel tubes—Part I: experiments. Thin-Walled Struct.102, 286–304. 10.1016/j.tws.2015.11.024 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasilikis, D., Karamanos, S. A., van Es, S. H. J. & Gresnigt, A. M. Ultimate bending capacity of spiral-welded steel tubes—Part II: predictions. Thin-Walled Struct.102, 305–319. 10.1016/j.tws.2015.11.025 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, R. & Wang, X. Lateral global buckling of submarine pipelines based on the model of nonlinear pipe-soil interaction. China Ocean. Eng.32, 312–322. 10.1007/s13344-018-0032-y (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, B. et al. Post-buckling behavior of stiffened cylindrical shell and experimental validation under non-uniform external pressure and axial compression. Thin-Walled Struct.16110.1016/j.tws.2021.107481 (2021).

- 14.Liu, Y. et al. Analysis and mitigation of the bending deformation in girth-welded slender pipes with numerical modelling and experimental measurement. J. Manuf. Process.78, 278–287. 10.1016/j.jmapro.2022.04.023 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, Z., Chen, Z. & Liu, H. Lateral buckling of pipe-in-pipe systems under sleeper-distributed buoyancy—a numerical investigation. Metals. 1210.3390/met12071094 (2022).

- 16.Su, W. & Ren, J. Numerical simulation of local buckling of submarine pipelines under combined loading conditions. Materials. 1510.3390/ma15186387 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Tian, H. et al. The effect of corrosion defects on the collapse pressure of submarine pipelines. Ocean. Eng.31010.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.118647 (2024).

- 18.Liu, Y. The influence of erosion manner on the buckling resistance of pipelines. Eng. Fail. Anal.15910.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108087 (2024).

- 19.Guo, L. & Yu, J. Bending behavior of aluminum foam-filled double cylindrical tubes. Acta Mech.222, 233–244. 10.1007/s00707-011-0537-4 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai, H., Tun, N., Yoon, K. & Kil, S. Effects of defects on failure of butt fusion welded polyethylene pipe. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip.139–140, 117–122. 10.1016/j.ijpvp.2016.03.010 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu, L., Zha, J. & Chen, Y. Comparative study on destructive performance and energy absorption of aluminum tube by simulation and experiment. Adv. Mech. Eng.1210.1177/1687814020924138 (2014).

- 22.He, Q., Wang, Y., Jiang, Y. & Shi, X. Crashworthiness behavior of reinforced circular tubes under lateral load impact. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng.4410.1007/s40430-021-03334-5 (2021).

- 23.Song, X., Zhao, J., Ma, R. & Li, J. Analysis of symmetrical three-point bending and springback process of pipes. Symmetry1710.3390/sym17010095 (2025).

- 24.Timoshenko, S. P. & Gere, J. M. Theory of Elastic Stability (McGraw-Hill Education, 1961).

- 25.Cao, Y. et al. Analysis of the evolution law of thermophysical properties of salinized calcareous clay in the low-temperature refrigerant leakage area of deeply buried strata. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf.22910.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.125723 (2024).

- 26.Wang, L. Mechanical properties of 20# steel after service under low temperature. Refrigeration33, 55–60. 10.3969/J.ISSN.1005-9180.2015.01.012 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen, Y., Hao, H., Chen, W., Cui, J. & Hao, Y. Dynamic tensile behaviors of welded steel joint material. J. Constr. Steel Res.18310.1016/j.jcsr.2021.106700 (2021).

- 28.Arbocz, J. & Starnes, J. H. On a high-fidelity hierarchical approach to buckling load calculations. In New Approaches To Structural Mechanics, Shells and Biological Structures (eds Drew, H. R. & Pellegrino, S.) 355–370, 10.1007/978-94-015-9930-6_22 (Springer, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Mises, R. Der kritische aussendruck Zylindrischer Rohre. Z. Ver. Dtsch. Ing.58, 750–755 (1914). [Google Scholar]

- 30.H Bryan, G. On the stability of elastic systems. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc.VI, 199–201 (1888). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brubak, L., Hellesland, J. & Steen, E. Semi-analytical buckling strength analysis of plates with arbitrary stiffener arrangements. J. Constr. Steel Res.63, 532–543. 10.1016/j.jcsr.2006.06.002 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacarbonara, W. Stability and bifurcation of structures. In Nonlinear Structural Mechanics (Springer) 10.1007/978-1-4419-1276-3_2.

- 33.Wong, W. & Pellegrino, S. Wrinkled membranes III: numerical simulations. J. Mech. Mater. Struct.1, 63–95. 10.2140/jomms.2006.1.63 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao, Y., Cao, Y., Feng, X. & Ma, K. Axial compression-induced wrinkles on a core-shell soft cylinder: theoretical analysis, simulations and experiments. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 73, 212–227. 10.1016/j.jmps.2014.09.005 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alijani, A., Darvizeh, M., Darvizeh, A. & Ansari, R. On nonlinear thermal buckling analysis of cylindrical shells. Thin-Walled Struct.95, 170–182. 10.1016/j.tws.2015.06.013 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor, M., Davidovitch, B., Qiu, Z. & Bertoldi, K. A comparative analysis of numerical approaches to the mechanics of elastic sheets. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 79, 92–107. 10.1016/j.jmps.2015.04.009 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavin, N. D. et al. On the implementation of a material point-based arc‐length method. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng.12510.1002/nme.7438 (2024).

- 38.Cheng, H. & Cai, H. Safety status and considerations of deep shaft freezing sinking technology in China. J. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci.33, 1–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1098.2013.02.001 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, M. et al. Research on multimodal damage monitoring of CFRP- steel pipe composite structures under three point bending loads. Constr. Build. Mater.48910.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.142304 (2025).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.