Abstract

Crisaborole, a distinctive boron-containing phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is used for the treatment of atopic dermatitis and eczema in adults and children. The development process for crisaborole involves organolithiation through a Br/Li exchange at −78 °C in batch mode. A continuous flow chemistry process was successfully developed for the synthesis of the key boronate intermediate of crisaborole, enabling efficient mixing, impurity control, and improved yield. The flow approach reduced the residence time dramatically from 1800 s in batch mode to just 1.5 s, and while elevating the temperature from −78 to −60 °C, it maintained precise control over impurity formation and achieved a significant improvement in overall yield. The boronate intermediate was subsequently subjected to one-pot THP deprotection and cyclization, resulting in the successful production of crisaborole in kilogram quantities. This approach allowed for effective control over product formation, optimized conditions for scalability, and careful management of the three impurities. The application of a quality by design (QbD) approach in the flow synthesis of crisaborole enabled systematic control and minimization of three critical impurities by establishing a thorough understanding of process parameters and their impact on product quality while also ensuring optimized conditions for scalability and effective control over product formation.

Introduction

Phosphodiesterases (PDE1–PDE11) play a key role in modulating inflammation and epithelial integrity present in immune cells, epithelial cells, and brain cells. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors act by blocking single or several subtypes (1–5) of enzyme phosphodiesterases (PDE) that lead to reducing the activity of the intracellular second messengers such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (CAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cyclic GMP). Representative examples include PDE3 inhibitor enoximone 1, used for the treatment of congestive heart failure; PDE4 inhibitors such as apremilast 2, used in the treatment of psoriasis, and roflumilast 3, used to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic bronchitis; and PDE5 inhibitors sildenafil 4 and tadalafil 5, used in the treatment of erectile dysfunction in men and pulmonary hypertension. Among the PDE4 inhibitors, crisaborole 6, a unique compound with a boron atom in the molecule, is used for the treatment of atopic dermatitis and eczema in adults and children. The ability of boron to create stable electron-deficient three-center, two-electron bonds and strong covalent two-center, two-electron bonds, along with its electrophilic nature, allows the formation of strong hydrogen bonds that contribute toward improved effective coordination of active sites in the drug delivery process. In recent times, there has been a growing interest in boron-containing small molecules as potential drug candidates. Notable examples include ixazomib 7, tavaborole 8, and vaborbactam 9 (Figure ).

1.

Structures of a few PDE inhibitors.

Crisaborole 6 was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in adults and children including infants aged three months and above. This drug is efficacious in improving disease severity, reducing the risk of infection, and reducing signs and symptoms in patients. It also reduces local inflammation in the skin and prevents further worsening of the disease. The boron atom present in the molecule also enables skin penetration and binding to the bimetal center of the phosphodiesterase 4 enzyme. Owing to its biological importance, several synthetic efforts have been directed toward the synthesis of crisaborole. ,

Recently, we have directed our research efforts toward the advancement of flow-based platforms aimed at establishing an integrated continuous process for the total synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), including daclatasvir, celecoxib, and the phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor sildenafil, along with its analogues. We herein present the development of the flow process for the synthesis of crisaborole and its associated impurities.

Although there are many synthetic schemes reported for the synthesis of crisaborole, few reports involve the use of an expensive boron coupling reagent, which significantly increases the production costs and limits commercial viability. , The conventional method for the large-scale preparation of boronates typically involves the batch process of lithiation of haloarenes at lower temperatures by using n-butyllithium followed by treatment with trialkyl borate, with better yields making the process more economical compared to the process involving boron coupling agents. However, the batch process presents several challenges: (1) the inherent instability of aryl lithium intermediates over extended periods, a phenomenon that is exacerbated with larger batch sizes and prolonged reaction times; (2) the potential for hotspot formation, which can result in the generation of undesired byproducts; (3) limitations regarding the compatibility with certain electrophilic functionalities, such as nitriles, that may be present in the target molecules; and (4) the necessity for low temperatures, which correlates with increased energy consumption, translating to higher operational costs during scale-up.

To address these issues, flow chemistry emerges as a viable alternative, as it offers enhanced control over reaction conditions owing to its superior regulation of process parameters, including residence time, pressure, temperature, mixing efficiency, concentration profiles, and stoichiometry. Notably, flow chemistry is characterized by improved heat transfer and mixing due to a higher surface-to-volume ratio, which facilitates better heat exchange. This enhanced mixing and heat transfer in shorter times mitigates the formation of byproducts linked to concentration and temperature inhomogeneity. The establishment of an efficient large-scale production method for crisaborole necessitates the meticulous management of n-butyllithium, alongside the optimization of reaction times and the lessening of waste generation. This endeavor presents a significant challenge that requires careful consideration of the reaction kinetics, reagent handling, and process scalability.

Over the past decade, numerous studies have successfully focused on the scale-up of lithiation reactions using continuous flow tube reactors. − The Yoshida group has illustrated the efficacy of lithiation reactions utilizing various electrophiles within micromixers and microtube reactors, demonstrating significant advantages over traditional batch methods. Both Newby et al. and Laue et al. have confirmed the practicality of scaling lithiation reactions in flow reactors for bulk production while also addressing the challenges associated with managing precipitation during the process.

The challenge of introducing electrophiles into substrates, combined with the capacity for rapid mixing characterized by a micromixing time on the order of seconds and the efficient transfer of mass and heat in an unobstructed flow of liquid without the risk of channel blockage, highlights the potential of employing process intensification (PI) methods for ortho-lithiation reactions within a continuous flow framework. Flow chemistry surpasses batch chemistry by providing greater efficiency, improved safety, enhanced control, reduced waste, easier scalability, real-time monitoring, and better energy efficiency, leading to more sustainable chemical processes. The primary aim of this study was to assess the benefits of conducting ortho-lithiation reactions in process intensification (PI) with flow reactors, particularly in comparison to traditional batch reactors, and access the boronate intermediate in an ultrafast reaction time.

Results and Discussion

The synthesis of crisaborole prominently features the boronation of the THP-protected bromoarene (compound 10) via lithiation, followed by a subsequent reaction with triisopropyl borate. This sequence further culminates in a one-pot process that includes THP deprotection and cyclization yielding the target compound. Initially, we conducted a batch synthesis of crisaborole by following established protocols to result in the boronated intermediate in 8100 s at −78 °C, which was further treated with 3 M HCl for 10 h to give crisaborole (40.2% isolated yield) with an HPLC purity of 50% (210 nm, area %), along with impurities 13 (4%), 14 (3.5%), and 15 (30.0%) (see Scheme S1 in the Supporting Information (SI)). Owing to the larger duration for chemical transformation and significant intermediate formation, we believed the flow process would be a better strategy for overcoming these challenges and thus initiated a flow process for crisaborole.

When the flow reaction was performed with 10 and n-butyllithium at −60 °C, the corresponding lithiated complex 11 was obtained within a residence time of 1.5 s. This complex was then subjected to treatment with 16, followed by a mixing period of 1.0 s to obtain the boronate 12, which was subsequently further quenched with the addition of 3 M HCl and stirred for 10 h to afford the cyclized product, crisaborole 6. The reaction ended up with an overall isolated crude yield of 50.0%, including impurities (Scheme ). The crude product was further assessed with HPLC (area %) to observe crisaborole 6 (65%) and the other impurities 13 (3.8%), 14 (3.0%), and 15 (20.0%).

1. Initial Approach of Crisaborole 6 Synthesis in Continuous Flow.

The advantages of conducting lithiation reactions in a continuous flow system at a mildly elevated temperature, as well as the significant reduction of the reaction duration from 8100 s (in the traditional batch, see SI) to just 2.5 s and the decrease in impurities from 50.0% to 35.0% in comparison to the batch process, prompted us to further optimize the process. The process analytical technology (PAT) tools and design of experiments (DoE) methodology were further used for optimization studies.

With the encouraging initial results using the flow process, when further attempts were made to scale-up by extending the reaction duration, complications associated with an increase in system pressure, subsequently leading to clogging issues within the flow reactor, were observed. To address this challenge and improve the process, subsequent optimization studies focused on mitigating the observed adverse effects by adopting Scheme , where the aryl halide 10 (0.1 M concentration) and triisopropyl borate 16 were taken together and treated with n-butyllithium (1.8 to 2.5 equiv), allowing lithiation at variable temperatures of 0 to −70 °C, followed by boronation to get 12 and then finally quenching 12 with aq. HCl (3 M) at 25 °C to get the crisaborole.

2. Improved Process for the Synthesis of Crisaborole 6 .

This modified flow approach provided noteworthy benefits. First, the in situ formation of the lithiated intermediate ensured a rapid reaction with the readily available electrophile (triisopropyl borate), promoting immediate conversion to the boronated product. Second, the combination of the bromoarene and triisopropyl borate led to an increased dilution of the reaction mixture, which also aided in mitigating the clogging issues encountered in previous longer-duration experiments (Scheme ). Also, the readily available triisopropyl borate effectively competed with the cyano group for nucleophilic attack by n-butyllithium, thereby reducing undesired side reactions and lowering the formation of impurity 15.

During the screening of reaction conditions, it was observed that approximately 15% of potential impurity 15 was generated. The formation of this impurity was attributed to an undesired side reaction, where excess n-butyllithium interacts with the nitrile group present in product 6. The isolation and characterization of other impurities revealed compounds 13 and 14, which are the debrominated arene products formed from the reaction of n-butyllithium with substrate 10. The lithiated species tend to undergo protonation instead of the desired boronation, potentially due to moisture present in the solvent. Furthermore, any unreacted lithiated intermediates may be protonated when exposed to 3 M HCl before undergoing boronation and cleavage of the tetrahydropyran (THP) group leading to 13 and 14, respectively. 13 could also be converted to 14 upon exposure to aq. HCl (3 M).

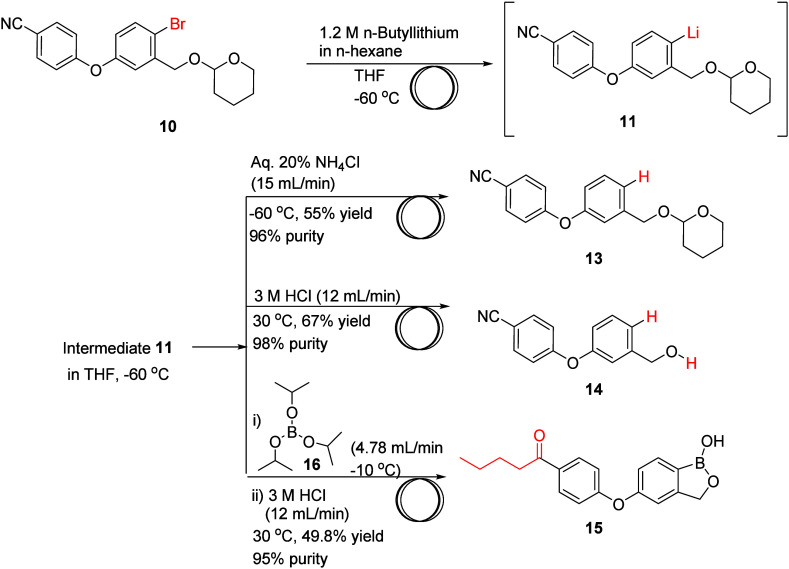

Our investigations have also enabled us to get the optimal conditions for accessing the impurities on the gram scale (Scheme ). Thus, based on the earlier experimental results, the appropriate optimal parameters (Schemes S2–S4 in the Supporting Information) were utilized for the gram-scale synthesis of impurities to provide 13 (4.4 g, 55% yield, and 96% HPLC purity), 14 (3.9 g, 67% yield, and 98% HPLC purity), and 15 (4.0 g, 49.8% yield, and 95% HPLC purity), respectively. Thus, the utilization of continuous flow chemistry allowed for efficient parameter selection toward optimization, contributing to the reproducibility and scalability of the impurities’ synthesis while maintaining high purity levels. This approach allowed for a systematic investigation of the conditions that can contribute to the generation of impurity generation. By managing these parameters, one could enhance the purity of the final product formation.

3. Synthesis of Major Crisaborole Impurities 13, 14, and 15 in Flow.

Monitoring of Process through the Implementation of Process Analytical Technology (PAT)

PAT methodologies utilizing online IR spectroscopy represent a significant advancement in the real-time monitoring and control of chemical processes. During the initial development phase, in-line infrared (IR) spectroscopy was employed to monitor the reaction progress and establish steady-state conditions, as a suitable HPLC method had not yet been developed; continuous monitoring of the reaction mixture via FTIR not only enabled real-time identification of reaction intermediates and product formation but also proved effective in ensuring reaction completion and minimizing exposure to hazardous intermediates in flow chemistry. METTLER TOLEDO iC IR software facilitated peak height analyses and evaluation of steady-state conditions, contributing to optimization of boronate intermediate 12 (in flow) and crisaborole 6 production processes (in batch). By selecting the peaks defined for a key functional group of the targets and monitoring their peak height, which is proportional to their concentration as a function of time and relative concentration, trends of raw material consumption (reduction in the peak height of C–Br stretching at 690 cm–1 due to replacement of Br with Li in flow mode), impurity formation, as well as product formation (increase in the signatory peak at 1424 cm–1 B–OH stretching in batch mode) were perceived (for details, see Figures S9–S11 in the Supporting Information) and proceeded further.

Critical Process Parameters in Flow by Quality by Design (QbD) Study

The identification of critical process parameters (CPPs) is a fundamental aspect of implementing the quality by design (QbD) framework. To establish these CPPs, initial screening experiments were conducted following Scheme . This approach emphasizes a systematic understanding of the factors influencing the quality of the final product, thereby facilitating optimization of the process. Through the screening experiments, key parameters were evaluated to determine their impact on the operational performance and product characteristics, ultimately guiding the development of a robust and reliable manufacturing process.

The one factor at a time (OFAT) methodology is a systematic experimental design approach employed for identifying critical factors influencing a specific outcome from a range of potential experimental variables. Employing this methodology, further experiments were designed and implemented following the parameters obtained from QbD experiments. A comprehensive experiment was conducted to evaluate the impact of various reaction conditions on the synthesis of crisaborole. Initially, the role of temperature was considered (Table ). At temperatures of 0 and −20 °C, though the reaction worked out, giving 72% and 81% of crisaborole 6, respectively, the formation of impurities 13 and 15 in high percentage (9.8% and 14.34%; 8.2% and 8.25%, respectively) was observed by HPLC area %. At −50 °C, the reaction yielded 87.45% crisaborole 6, along with impurities 13, 14, and 15 of 6.99%, 1.00%, and 3.24%, respectively, determined by HPLC (area %). Notably, upon decreasing the temperature further to −60 °C, a slight enhancement in the yield of crisaborole was observed, reaching 89.39% (area %) under the curve. Subsequent temperature reductions did not produce significant changes in the final yield of crisaborole. Following the thermal optimization, the study transitioned to assess the influence of n-butyllithium equivalents (Table ) on the reaction outcome. Lower concentrations of n-butyllithium resulted in an increased formation of impurity 13 and a decreased yield of crisaborole, which was approximately 82% (area %). Optimal results were achieved using 2 equiv of n-butyllithium, leading to a maximum productivity of 89.70% (area %) of crisaborole. However, an increase beyond this optimal concentration resulted in a rise in the formation of impurity 15, accompanied by a slight decline in the area percentage of crisaborole, which measured at 87.53%. Additionally, the evaluation of residence time revealed that a residence time of 1.5 s provided the most favorable conditions for achieving optimal yields, with crisaborole formation reaching approximately 89.5% (Table ). Lowering the residence time below 1.5 s led to a reduction in overall product purity by increasing the percentage of impurity 13 and impurity 14.

1. Effect of Temperature on Crisaborole Formation .

| Process

Parameter |

Area % in HPLC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 10 | 13 | 14 | 15 | Crisaborole (6) |

| 0 | 0.01 | 9.8 | 3.2 | 14.34 | 72.0 |

| –20 | 0.01 | 8.2 | 2.4 | 8.25 | 81.10 |

| –50 | 0.01 | 6.99 | 1.00 | 3.24 | 87.45 |

| –60 | 0.01 | 6.26 | 0.80 | 2.81 | 89.39 |

| –70 | 0.01 | 6.20 | 0.80 | 2.81 | 89.25 |

All reactions were conducted using 5.0 g (1.0 equiv) of compound 10, n-butyllithium (2.0 equiv), and triisopropyl borate (4.0 equiv), with a residence time of 1.5 s. The temperature was varied as detailed in the accompanying table for the coupling reaction. Following this, cyclization was carried out using 3 M HCl (7.0 equiv). The area percentage under the peak at 210 nm was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to assess the product formation and impurity levels.

2. Effect of n-Butyllithium on Crisaborole Formation .

| Process

Parameter |

Area % in HPLC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equivalents of n-Butyllithium | 10 | 13 | 14 | 15 | Crisaborole (6) |

| 1.8 | 0.70 | 10.81 | 1.80 | 2.20 | 82.01 |

| 2.0 | 0.10 | 6.30 | 0.80 | 2.78 | 89.70 |

| 2.5 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 4.38 | 5.97 | 87.53 |

All reactions were conducted utilizing 5.0 g (1.0 equiv) of compound 10, with triisopropyl borate at a stoichiometric ratio of 4.0 equiv under cryogenic conditions of −60 °C and a residence time of 1.5 s. The equivalents of n-butyllithium were varied, while 3 M HCl was employed at 7.0 equiv for the cyclization reaction. The analysis of reaction products was performed using HPLC, measuring the area percentage at a wavelength of 210 nm.

3. Effect of Residence Time on Crisaborole Formation .

| Process

Parameter |

Area % in HPLC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence Time (s) | 10 | 13 | 14 | 15 | Crisaborole (6) |

| 2.0 | 0.10 | 7.93 | 2.20 | 3.30 | 85.00 |

| 1.5 | 0.01 | 6.25 | 0.80 | 2.80 | 89.50 |

| 1.0 | 0.01 | 6.70 | 0.85 | 2.70 | 88.50 |

| 0.5 | 0.01 | 6.80 | 0.88 | 2.60 | 88.20 |

| 0.25 | 0.03 | 6.88 | 0.92 | 2.57 | 88.05 |

| 0.10 | 0.05 | 6.98 | 1.0 | 2.50 | 87.92 |

All reactions were conducted using 5.0 g (1.0 equiv) of compound 10, triisopropyl borate at 4.0 equiv, and n-butyllithium at 2.0 equiv under conditions of −60 °C. The residence time was varied as indicated in the accompanying table for the coupling reaction. For cyclization, 3 M HCl was employed at a stoichiometric ratio of 7.0 equiv. The area percentage was assessed at 210 nm using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Based on the domain knowledge, historical data, and pre-DoE/OFAT experimentation, the parameters of equivalents of n-butyllithium, reaction temperature, and residence time were considered for the DoE experimentation (Table ).

4. Three Process Parameters for Optimization (DoE).

| Range |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Parameter | Unit | Low | High | Justification |

| A | n-Butyllithium | Equivalents | 1.8 | 3.0 | Higher and lower equivalents have significant impact on the quality of the product |

| B | Reaction temperature | °C | –60 | –40 | Higher and lower reaction temperature has significant impact on the quality of the product |

| C | Res. time | Seconds | 0.5 | 2.0 | Residence time has impact on impurity formation, particularly for impurity 15 |

The process parameters such as the volume of THF solvent and equivalents of 3 M HCl are considered constant considering their predefined limit, as shown in Table .

5. List of Parameters That Were Held Constant during Optimization DoE Studies.

| Sr No | Parameter | Unit | Limit | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quantity of 16 | Equivalents | 4.0 | These are the minimum equiv required and studied during screening DoE |

| 2 | Quantity of 3 M HCl | Equivalents | 7.0 | |

| 3 | Volume of THF | Volume | 25 | No effect on responses, based on pre-DoE study |

Based on historical data and domain knowledge, three variables (base, temperature, and time) were considered for the design of experiments, which are captured in Table . Factorial design (reduced 2FI) was considered with two levels and three center runs (which is used to calculate error). No blocks were considered for the design. Eleven experiments were planned, including three center runs. Four responses were considered for the model, which are captured in Table .

6. DoE Experimental Results.

| Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

Response 1 |

Response 2 |

Response 3 |

Response 4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std | A: n-Butyllithium Lithium (equiv) | B: Reaction Temp (°C) | C: Res. Time (s) | 15 (%) | 13 (%) | 14 (%) | 10 (%) |

| 1 | 1.8 | –60 | 0.50 | 1.68 | 3.76 | 10.81 | 0.70 |

| 2 | 3.0 | –60 | 0.50 | 7.97 | 3.58 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| 3 | 1.8 | –40 | 0.50 | 2.43 | 3.26 | 9.33 | 0.47 |

| 4 | 3.0 | –40 | 0.50 | 11.30 | 2.15 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| 5 | 1.8 | –60 | 2.00 | 2.79 | 6.20 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| 6 | 3.0 | –60 | 2.00 | 14.43 | 4.76 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| 7 | 1.8 | –40 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 11.55 | 17.5 | 0.86 |

| 8 | 3.0 | –40 | 2.00 | 22.87 | 5.20 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| 9 | 2.4 | –50 | 1.25 | 5.97 | 4.38 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| 10 | 2.4 | –50 | 1.25 | 7.99 | 4.54 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| 11 | 2.4 | –50 | 1.25 | 7.61 | 3.70 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

Response of Impurity 15 (%)

Based on the individual effects plots (Figure ) and the ANOVA (analysis of variance) results (see SI, Table S6), n-butyllithium (A), reaction temperature (B), and residence time (C) were found to show a positive impact on the impurity 15. They clearly reveal that a higher content of impurity 15 is formed as the n-butyllithium concentration or reaction temperature is increased. The n-butyllithium equivalents were found to show a significant impact on response (refer to Figure ). Considering the interaction plot, it was observed that none of the factors show interactions. Based on the Pareto chart, A (n-butyllithium), B (reaction temperature), and C (residence time) were found to be significant model terms. Among them, A (n-butyllithium) had the highest significance (refer to Figure ).

2.

Pareto chart, effects plots, and contour plots for impurity 15.

Analysis of the contour plot indicates that the formation of impurity 15 is inversely correlated with the levels of n-butyllithium, suggesting that a reduction in its amount leads to diminished impurity concentrations. Considering the contour plot for the variation of impurity 15 with respect to n-butyllithium equivalents and reaction temperature, the blue region indicates impurity 15 content <6%, while progression toward the green/orange region indicates an increasing amount of impurity 15 content in proportion to increased equivalents of n-butyllithium. Here the contour plots are given varying C (residence time) at 0.5 and 2.0 s (refer to Figure ).

Conclusion from DoE Experiment

In conclusion, the design space experiment (refer to Figure ) enabled the identification of optimal conditions wherein the impurity formation is further minimized. Finally, the recommended operating parameters were obtained as a residence time of 0.5 to 2.0 s, a reaction temperature range of −60 to −40 °C, and an amount of n-butyllithium between 1.8 and 3.0 equiv (refer to Table ). Adhering to these parameters would anticipate product purity enhancement attributed to effectively reducing impurity formation, thereby aligning with the principles of QbD in the development of robust pharmaceutical processes.

3.

Design space diagram (criteria: impurity 15, <5.7%; impurity 14, 5.0%; impurity 13, <10%).

7. Point Prediction Based on DoE Study.

| Factor | Name | Level | Low Level | High Level | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | n-Butyllithium | 2.0 | 1.8 | 3 | 0 |

| B | Reaction temperature | –50 | –60 | –40 | 0 |

| C | Residence time | 1.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 0 |

| Response | Prediction | SE Mean | 95% CI Low | 95% CI High | SE Pred | 95% PI Low | 95% PI High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 8.55875 | 0.588801 | 7.04519 | 10.07231 | 2.039665 | 3.315624 | 13.8018757 |

| 13 | 5.0575 | 0.13448 | 4.47888 | 5.63612 | 0.465852 | 3.0531 | 7.061899822 |

| 14 | 4.71625 | 0.001741 | 4.70876 | 4.72374 | 0.00603 | 4.690304 | 4.742195972 |

| 10 | 0.31625 | 0 | 0.31625 | 0.31625 | 0 | 0.31625 | 0.31625 |

Overall, the application of the QbD and OFAT approach facilitated the optimization and identification of critical process parameters, including temperature (−60 °C, lower than set point would be good), equivalents of n-butyllithium (2.0 equiv), and residence time (1.5 s) as observed, promoting a systematic understanding of their impact on the reaction. In summary, the investigation of various process parameters demonstrates that flow chemistry substantially enhances the overall yield while concurrently decreasing the reaction time.

Process for Overall Production of Crisaborole 6 (Using DoE Design Space)

After scrutinizing the optimized parameters obtained from QbD experiments and the OFAT approach, we successfully applied the finalized optimal parameters for scaling up the crisaborole synthesis. Toward this, a 4 mL INNOSYN 3D-printed flow reactor (2.26 mm ID, 160 mL/min) was utilized in place of a 0.2 mL PFA coil flow reactor (1 mm ID, 8 mL/min). Effective mixing was crucial for optimal transformation, and this was achieved with this flow reactor through turbulence induced by high flow rates, enhancing shear forces and convective currents, which ensured homogeneity of the reactants at −60 °C during treatment of the 0.1 M reaction mixture (10 and triisopropyl borate, 16) with n-butyllithium (1.2 M in n-hexane, 2.0 equiv) for 1.5 s. This approach yielded intermediate 12, which, upon reaction with 3 M HCl and further stirring for 10 h, produced crisaborole 6 with an impressive yield of 92.73% (isolated) and 99.38% purity by HPLC (area %), demonstrating a productivity of 4591.2 g/day (Figure ). Since n-butyllithium was handled, appropriate safety measures were considered (see SI for details), and an integrated distributed control system (DCS) and alarm protocols for pressure and temperature monitoring were used.

4.

Process diagram for the overall production of crisaborole.

Experimental Procedures for Preparation of Crisaborole (Using DoE Design Space)

Procedure 1 for Crisaborole Synthesis in Continuous Flow (Scheme )

A solution of compound 10 (10 g, 25.8 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was prepared by dissolving it in tetrahydrofuran (THF) to make 258 mL of solution in a glass bottle. A separate bottle containing THF was connected to a solenoid valve linked to ceramic piston pump A, which was set to a flow rate of 6.86 mL/min. The outlet of this pump was connected to a prechilled (−60 °C) PFA coil (volume, 5.0 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 637.0 cm), which was used to maintain low temperatures. n-Butyllithium was contained in a reagent bottle under a nitrogen atmosphere, with n-hexane as the solvent, and also connected to a solenoid valve. The n-butyllithium solution was pumped using Vapourtec V-3 pump C, set to a flow rate of 1.14 mL/min, with the outlet equipped with a prechilled (−60 °C) PFA coil (volume, 5.0 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 637.0 cm). The mixture of compound 10 and n-butyllithium in the prechilled coil (−60 °C) was directed into a customized PFA coil reactor (volume, 0.2 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm, length 25.5 cm) via a T-mixer. The residence time within this reactor was set to 1.5 s, and the reactor jacket temperature was controlled at −60 °C using dry ice in a Dewar flask. Compound 12 was infused into the outflow of the reaction mixture via a prechilled (−60 °C) PFA loop (5 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 637.0 cm), which maintained a residence time of 5 s within another customized PFA reactor (volume, 0.15 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 19.1 cm), also set at −60 °C and operating at a flow rate of 0.64 mL/min through ceramic piston pump B. The boronate intermediate product 12 was then introduced into a subsequent T-mixer, where a 3 M HCl solution was added via pump D at a flow rate of 1.6 mL/min. This mixture was passed through a customized PFA coil (volume, 0.85 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 108 cm), maintained at 25 °C, with a residence time of 5 s for THP deprotection and cyclization to occur. The tube lengths for each reagent after and before the pump were 100 cm (1 mm bore diameter). The respective tube lengths, reactor volumes, and concentrations of each reagent, residence time, and temperature were input into the Vapourtec R-series software with the equivalence ratio for compound 10:n-butyllithium:compound 16:HCl solution (3 M) set at 1:2:4:7. An online infrared (IR) spectrometer was connected to the output of the flow reactor assembly for continuous monitoring, and a waste and production collection bottle was set up. The pressure cutoff limit for safety was established at 8 bar. Prior to initiating the reaction, all pumps were switched to the solvent side and maintained in this configuration for 10 min until the respective temperatures stabilized at −60 and 25 °C. The Vapourtec R-series auto recipe mode was activated, and an initial collection was directed to a waste bottle before switching to the product side after achieving steady state (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Steady state was concluded after observing the signatory spectral peak height, which starts and continues with similar height intensity over the reaction time. Following the complete consumption of compound 10, all pumps were switched to the solvent side after 37 min, with the collection switched back to the waste side. The collected product was stirred at 25 °C in a round-bottom flask equipped with an IR probe to monitor the completion of the reaction, which was further confirmed by HPLC analysis. The product profile indicated a purity of 55.0% (area %), with the presence of impurities: 10 (0.7%), 13 (7.4%), 14 (6.2%), and 15 (28.0%). The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (50 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with water (10 mL). The organic layer was then distilled under reduced pressure at 40–45 °C to obtain a crude oil, to which methanol (20 mL) was added. The mixture was gradually cooled to 10–15 °C and stirred for an additional 3 h. The reaction mixture was subsequently filtered, and the solid was washed with methanol (50 mL). The resulting wet solid was vacuum-dried at 40–45 °C for 6 h. The isolated solid was analyzed by HPLC, yielding crisaborole (3.2 g, isolated yield of 50.0%) as an off-white solid with a purity of 65.0% by HPLC analysis, along with impurities: 10 (0.01%), 13 (3.8%), 14 (3.0%), and 15 (20%).

Procedure 2 for Continuous Flow Synthesis of Crisaborole (Scheme )

To a 0.1 M solution of compound 10 (10.0 g, 25.8 mmol, 1.0 equiv) dissolved in THF (25.8 mL) in a bottle, triisopropyl borate 16 (19.5 g, 103.2 mmol) was added and further diluted with THF to make a 258 mL solution in a glass bottle. A separate bottle containing THF was connected to a solenoid valve linked to ceramic piston pump A, which was set to a flow rate of 6.86 mL/min. The outlet of this pump was connected to a prechilled (−60 °C) PFA loop (5 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 637.0 cm), which was used to maintain low temperatures. 1.2 M n-butyllithium was contained in a reagent bottle under a nitrogen atmosphere, with n-hexane as the solvent. This was also connected to a solenoid valve. The n-butyllithium was pumped using Vapourtec V-3 pump C, set to a flow rate of 1.14 mL/min, with the outlet equipped with a prechilled (−60 °C) PFA loop (5 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 637.0 cm). The mixture of compound 10 + 16 and n-butyllithium in the prechilled coil was directed into a customized PFA coil reactor (volume, 0.2 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 25.5 cm) via a T-mixer. The residence time within this reactor was set to 1.5 s, and the reactor jacket temperature was controlled at −60 °C using dry ice in a Dewar flask (see Figure S4 in the Supporting Information for an actual setup photo). The outgoing boronate intermediate product 12 was then introduced into a subsequent T-mixer, where a 3 M HCl solution was added via pump D at a flow rate of 1.6 mL/min. This mixture passed through a customized PFA coil (volume, 0.80 mL; bore diameter, 1.0 mm; length, 102 cm), maintained at 25 °C, with a residence time of 5 s. The tube lengths for each reagent before and after the pump were 100 cm (bore diameter of 1 mm). The data of the respective tube lengths, reactor volumes, and concentrations of each reagent, residence time, and temperature were input into the Vapourtec R-series software with the equivalence ratio for compound 10 + 16 mixture:n-butyllithium:HCl solution (3 M) set at 1:2:7. An online infrared (IR) spectrometer was connected to the output of the flow reactor assembly for continuous monitoring, and a waste and production collection bottle was set up. The pressure cutoff limit for safety was established at 8 bar. Prior to initiating the reaction, all pumps were switched to the solvent side and maintained in this configuration for 10 min until the respective temperatures stabilized at −60 and 25 °C. The Vapourtec R-series auto recipe mode was activated, and an initial collection for 1 min was directed to a waste bottle before switching to the product side after achieving steady state. Following the complete consumption of compound 10, all pumps were switched to the solvent side, with the collection switched back to the waste side after 50 s. The collected product was stirred at 25 °C in a round-bottom flask equipped with an IR probe to monitor the completion of the reaction, which was further confirmed by HPLC analysis. The product profile indicated a purity of 89.38% by HPLC area %, with the presence of impurities: 10 (0.1%), 13 (0.2%), 14 (0.5%), and 15 (2.0%). The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (50 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with water (10 mL). The organic layer was then distilled under reduced pressure at 40–45 °C to obtain a crude oil, to which methanol (20 mL) was added. The mixture was gradually cooled to 10–15 °C and stirred for an additional 3 h. The reaction mixture was subsequently filtered, and the solid was washed with chilled methanol (50 mL). The resulting wet solid was vacuum-dried at 40–45 °C for 6 h. The isolated solid was analyzed by HPLC, yielding crisaborole (5.9 g, 91.2% yield) as an off-white solid with a purity of 99% by HPLC analysis along with impurities 10 (0.01%), 13 (0.03%), 14 (0.03%), and 15 (0.04%), as determined by HPLC.

Scale-Up Procedure for Continuous Flow Synthesis of Crisaborole

A 0.1 M solution of a mixture of compound 10 (1.0 kg, 2576 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in 20.0 L of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and triisopropyl borate 16 (1.95 kg, 10304 mmol) was taken in a 50 L vessel and further diluted to a total volume of 25.76 L, maintaining an inert nitrogen atmosphere throughout the preparation. n-Butyllithium (1.2 M in hexane, 5152 mmol, 2.0 equiv) was contained in a separate 5 L cylinder with a nitrogen pressure of 0.1 bar. Prechilled (−60 °C) 5 mL SS coil loops were connected (bore diameter, 6.35 mm; length 31.6 cm) for the mixture of compound 10 + 16 and n-butyllithium after each pump connected through a mass flow controller and pressure release valve and nonreturnable valve and kept in a jacketed vessel and further connected with a Huber 815 Heater and Chiller (for instrumentation parts, see Figure S7 in the Supporting Information, and for actual flow setup, see Figure ). The reactor system included a 3D-printed Innosyn 4.0 mL SS-316 reactor with a 2.26 mm internal diameter, integrated with T-mixer, and was connected to a Huber 815 cooling system. A Hastelloy coil reactor (16.0 mL volume, 6.35 mm diameter, 50.5 cm length), maintaining a target temperature of 25 °C, was controlled by another Huber system. The stock solution of the compound 10 + 16 mixture was infused at a flow rate of 137.0 mL/min, while n-butyllithium was added at 23.0 mL/min, yielding a residence time of 1.5 s. The reaction temperature was maintained at −60 °C using a thermocouple and controlled by a Huber 815 instrument (set point of −70 °C). In-line quenching of the reaction was achieved by adding 3 M HCl (32.0 mL/min) from a third reactor port, also using a Fuji HYM Super Metering Pump, with precise monitoring via Endress+Hauser mass flow meters. The output from the continuous flow synthesis process was initially directed into a waste collection tank containing a 10% ammonium chloride solution. This strategy was employed to ensure safe quenching of the reactive n-butyllithium present in the reaction effluent. Prior to the reagent introduction, the system was flushed with THF and hexane through switch valves while ensuring the desired operating temperature of −60 °C was reached. After initially collecting waste for 30 s to stabilize operating conditions, the process transitioned to continuous product collection, maintaining the temperature at 25 °C using a heat exchanger. The reactor system was operated under nitrogen pressure (0.5 bar), with key parameters being monitored via a distributed control system (DCS), incorporating back pressure regulation at 1 bar for safety measures (see SI, Safety Considerations, p S18) included nitrogen inertization, pressure safety valves with pop-off thresholds of 15 bar, and nonreturn valves to prevent reagent back-mixing. The DCS also facilitated automatic switching to solvent mode if the pressure exceeded safe limits of 10 bar or the temperature exceeded the set point in the Huber system.

Quality control was performed every 30 min via HPLC, ensuring that the level of compound 10 remained below 1.0%. The output reaction mass was stirred for 10 h at 25 °C to promote cyclization. Postreaction, layer separation and extraction of the aqueous phase with ethyl acetate (5.0 L) were performed. The combined organic layer was washed with water (1.0 L) and subsequently evaporated at 40–45 °C under vacuum to yield a viscous oil. Methanol (2.0 L) was then added while cooling to 10–15 °C and stirred for 3 h, and the resulting precipitate was filtered and washed with chilled methanol (0.5 L). The dried final product yielded crisaborole (0.60 kg, 92.73% yield), characterized as an off-white solid with an HPLC purity of 99.38%, alongside low impurities of 10 (0.01%), 13 (0.003%), 14 (0.006%), and 15 (0.04%) as determined by HPLC (Figure S20; see Figure S18 for 1H NMR and Figure S19 for 13C NMR). The continuous setup as per Figure was operated for 5 days continuously without any noticeable increase in temperature or pressure, yielding 23 kg of crisaborole with similar purity of 99% HPLC purity.

Conclusion

We successfully developed a continuous flow process for the synthesis of crisaborole, leveraging flow chemistry to enhance efficiency, safety, and scalability compared with traditional batch methods by improving the yield by 50%. Our optimized flow conditions effectively control impurity formation and facilitate the safe handling of the pyrophoric reagent n-butyllithium (for performing the reaction and also quenching excess reagent after the reaction), thereby improving the reaction kinetics and thermal regulation in the lithiation step. We have addressed challenges such as clogging from lithiated intermediates through the strategic addition of electrophiles, validating the commercial applicability of our platform. These findings suggest a robust and scalable process supported by the potential to increase the flow reactor volume capable of producing 165 tons annually, thereby paving the way for the rapid scale-up of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in kilogram quantities. Our ongoing research aims to expand this innovative flow chemistry platform for the synthesis of additional APIs, positioning it as a transformative approach in pharmaceutical synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Director, CSIR-IICT for providing research infrastructure facilities. CSIR−IICT Communication No. IICT/Pubs./2024/298. C.S.B. thanks Cipla LTD, Mumbai, for supporting doctoral research as part of a collaborative project with CSIR-IICT, Hyderabad, and providing the facility for the flow process. The authors also thank Dr. Shiva K. K. Balaji for helping in the manuscript preparation.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PDE

phosphodiesterases

- CPPs

critical process parameters

- PAT

process analytical technology

- CAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- cyclic GMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- FTIR

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

- DoE

design of experiments

- THP

tetrahydropyran

- equiv

equivalent

- res. time

residence time

- QbD

quality by design

- OFAT

one factor at a time

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c07458.

General methods, flow setup (pictorial view), crisaborole impurity synthesis, IR instrumentation setup and spectra, and 1H and 13C NMR of products 6, 13, 14, and 15 (PDF)

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- a Boswell-Smith V., Spina D., Page C. P.. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006;147:S252–S257. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Halpin D.. ABCD of The Phosphodiesterase Family: Interaction and Differential Activity in COPD. Int. J. Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:543–561. doi: 10.2147/copd.s1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon M. W., Heel R. C., Brogden R. N.. Enoximone. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential. Drugs. 1991;42:997–1017. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer P. H., Parton A., Capone L., Cedzik D., Brady H., Evans J. F., Man H.-W., Muller G. W., Stirling D. I., Chopra R.. Apremilast is a Selective PDE4 Inhibitor with Regulatory Effects on Innate Immunity. Cell. Signal. 2014;26:2016–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hatzelmann A., Morcillo E. J., Lungarella G., Adnot S., Sanjar S., Beume R., Schudt C., Tenor H.. The preclinical pharmacology of roflumilast – a selective, oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor in development for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23:235–256. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rabe K. F.. Update on Roflumilast, a Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;163:53–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. A., Lie J. D.. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) Inhibitors in the Management of Erectile Dysfunction. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;38(7):407–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a FDA Approves Eucrisa for Eczema (Press release); U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2016. [Google Scholar]; b Downey K. Jr. FDA approves Eucrisa for Atopic Dermatitis in Infants. Infec. Dis. Child. 2020;33(4):7. [Google Scholar]; c Merchant, R. S. ; Merchant, A. S. ; Limbad, P. B. ; Pansuriya, A. M. ; Vavaiya, B. M. ; Faldu, J. M. . Process for the preparation of crisaborole and its intermediates. U.S. Patent US11014944B2, 2021.; d Peijie, L. ; Yuanchao, S. ; Muqun, Z. ; Heng, D. ; Suwan, G. ; Zhenyu, H. ; Krivonos, S. ; Khashper, A. ; Shteinman, V. ; Sery, Y. ; Ben-Daniel, R. . Crisaborole production process. Patent WO2018150327A1, 2018.

- a Staquis EPAR; European Medicines Agency (EMA), 2020. Retrieved 2020-04-28. [Google Scholar]; b PRODUCT MONOGRAPH; Government of Canada, 2018. Retrieved 2019-04-07. [Google Scholar]; c Baker, S. J. ; Sanders, V. ; Akama, T. ; Bellinger-Kawahara, C. ; Freund, Y. ; Maples, K. R. ; Plattner, J. J. ; Zhang, Y.-K. ; Zhou, H. ; Hernandez, V. S. . Boron-containing small molecules as anti-inflammatory agents. U.S. Patent US8501712B2, 2013.; d Coghi, P. Boron-containing small molecules as antiparasitic agents. Fundamentals and Applications of Boron Chemistry; Elsevier, 2022; pp 155–201. [Google Scholar]; e Shirley M.. Ixazomib: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2016;76:405–411. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Gupta A. K., Versteeg S. G.. Tavaborole–a Treatment for Onychomycosis of the Toenails. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016;9(9):1145–1152. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2016.1206467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Andrei S., Valeanu L., Chirvasuta R., Stefan M.-G.. New FDA Approved Antibacterial Drugs: 2015–2017. Discoveries. 2018;6(1):e81. doi: 10.15190/d.2018.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairnar P. V., Saathoff J. M., Cook D. W., Hochstetler S. R., Pandya U., Robinson S. J., Satam J., Donsbach K. O., Gupton B. F., Jin L.-M., Shanahan C. S.. Practical Synthesis of 6-Amino-1-hydroxy-2,1-benzoxaborolane: A Key Intermediate of DNDI-6148. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2024;28:1213–1223. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.4c00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A., Mahajan B., Ghosh S., Pabbaraja S., Singh A. K.. Integrated Multi-Step Continuous Flow Synthesis of Daclatasvir without Intermediate Purification and Solvent Exchange. React. Chem. Eng. 2020;5:2109–2114. doi: 10.1039/D0RE00323A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Mahajan B., Aand D., Purwa M., Mujawar T., Ghosh S., Pabbaraja S., Singh A. K.. Elements-Continuous-Flow Platform for Coupling Reactions and Anti-viral Daclatasvir API Synthesis. Synthesis. 2024;56:657. doi: 10.1055/a-2022-2063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Mahajan B., Mujawar T., Ghosh S., Pabbaraja S., Singh A. K.. Micro-Electro-Flow Reactor (μ-EFR) System for Ultra-Fast Arene Synthesis and Manufacture of Daclatasvir. Chem. Commun. 2019;55:11852–11855. doi: 10.1039/C9CC06127D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sthalam V. K., Singh A. K., Pabbaraja S.. An Integrated Continuous Flow Micro-Total Ultrafast Process System (m-TUFPS) for the Synthesis of Celecoxib and Other Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019;23:1892–1899. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.9b00212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sthalam V. K., Mahajan B., Karra P. R., Singh A. K., Pabbaraja S.. Sulphonated Graphene Oxide Catalyzed Continuous Flow Synthesis of Pyrazolo Pyrimidinones, Sildenafil and other PDE-5 Inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2021;12:326–330. doi: 10.1039/D1RA08220E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laue S., Haverkamp V., Mleczko L.. Experience with Scale-Up of Low-Temperature Organometallic Reactions in Continuous Flow. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016;20:480–486. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Nagaki A., Yamada S., Doi M., Tomida Y., Takabayashi N., Yoshida J.-i.. Flow Microreactor Synthesis of Disubstituted Pyridines from Dibromopyridines via Br/Li Exchange without Using Cryogenic Conditions. Green Chem. 2011;13:1110–1113. doi: 10.1039/c0gc00852d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Yoshida J.-i., Kim H., Nagaki A.. Green and Sustainable Chemical Synthesis Using Flow Microreactors. ChemSusChem. 2011;4:331–340. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Nagaki A., Ichinari D., Yoshida J.-i.. Three-Component Coupling based on Flash Chemistry. Carbolithiation of Benzyne with Functionalized Aryllithiums Followed by Reactions with Electrophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12245–12248. doi: 10.1021/ja5071762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Nagaki A., Imai K., Ishiuchi S., Yoshida J.-i.. Reactions of Difunctional Electrophiles with Functionalized Aryl Lithium Compounds: Remarkable Chemoselectivity by Flash Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. ed. 2015;54:1914–1918. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Nagaki A., Takahashi Y., Yoshida J.-i.. Extremely Fast Gas/Liquid Reactions in Flow Microreactors: Carboxylation of Short-Lived Organolithiums. Chem. A Eur. J. 2014;20:7931–7934. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Nagaki A., Imai K., Ishiuchi S., Yoshida J.-i.. Reactions of Difunctional Electrophiles with Functionalized Aryl Lithium Compounds: Remarkable Chemoselectivity by Flash Chemistry. Angew. Chem. 2015;127:1934–1938. doi: 10.1002/ange.201410717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references cited therein.

- Plutschack M. B., Pieber B., Gilmore K., Seeberger P. H.. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Flow Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017;117(18):11796–11893. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Newby J. A., Blaylock D. W., Witt P. M., Turner R. M., Heider P. L., Harji B. H., Browne D. L., Ley S. V.. Reconfiguration of a Continuous Flow Platform for Extended Operation: Application to a Cryogenic Fluorine-Directed ortho-Lithiation Reaction. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014;18:1221–1228. doi: 10.1021/op500221s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wietelmann U., Klosener J., Rittmeyer P., Schnippering S., Bats H., Stam W.. Continuous Processing of Concentrated Organolithiums in Flow Using Static and Dynamic Spinning Disc Reactor Technologies. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022;26:1422–1431. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.2c00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Clayden, J. Organolithiums: Selectivity for Synthesis; Tetrahedron Organic Chemistry Series, Vol. 23; Pergamon Elsevier Science, Oxford, 2002; pp 9–109. [Google Scholar]; d Wietelmann U., Klett J.. 200 Years of Lithium and 100 Years of Organolithium Chemistry. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2018;644:194–204. doi: 10.1002/zaac.201700394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Soutome H., Maekawa K., Ashikari Y., Nagaki A.. Highly Productive Flow Synthesis for Lithiation, Borylation, and/or Suzuki Coupling Reaction. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2024;28:2006–2012. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.4c00021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Capaldo L., Wen Z., Noël T.. A Field Guide to Flow Chemistry for Synthetic Organic Chemists. Chem. Sci. 2023;14:4230–4247. doi: 10.1039/D3SC00992K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Alfano A. I., Garcia-Lacuna J., Griffiths O. M., Ley S. V., Baumann M.. Continuous flow synthesis enabling reaction discovery. Chem. Sci. 2024;15:4618–4630. doi: 10.1039/D3SC06808K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z., Baxendale I. R., Ley S. V.. A Continuous Flow Process Using a Sequence of Microreactors with In-line IR Analysis for the Preparation of N,N-Diethyl-4-(3-fluorophenylpiperidin-4- ylidenemethyl)benzamide as a Potent and Highly Selective δ-Opioid Receptor Agonist. Chem. A Eur. J. 2010;16:12342–12348. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metil D. S., Sonawane S. P., Pachore S. S., Mohammad A., Dahanukar V. H., McCormack P. J., Reddy C. V., Bandichhor R.. Synthesis and Optimization of Canagliflozin by Employing Quality by Design (DbD) Principles. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018;22:27–39. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.