Despite the overwhelming bacterial diversity present in the world's oceans, the majority of recognized marine bacteria fall into as few as nine major clades (36), many of which have yet to be cultivated in the laboratory. Molecular-based approaches targeting 16S rRNA genes demonstrate that the Roseobacter clade is one of these major marine groups, typically comprising upwards of 20% of coastal and 15% of mixed-layer ocean bacterioplankton communities (see, e.g., references 36, 37, 42, 98, and 109). Roseobacters are well represented across diverse marine habitats, from coastal to open oceans and from sea ice to sea floor (see, e.g., references 16, 28, 37, 42, 52, and 98). Members have been found to be free living, particle associated, or in commensal relationships with marine phytoplankton, invertebrates, and vertebrates (see, e.g., references 4, 6, 7, 44, 49, 115, and 119). Furthermore, representatives of the clade stand out as representing one of the most readily cultivated of the major marine lineages (36). These isolated representatives are serving as the foundation for an improved understanding of marine bacterial ecology and physiology.

DESCRIPTION OF THE GROUP

The Roseobacter clade falls within the α-3 subclass of the class Proteobacteria, with members sharing >89% identity of the 16S rRNA gene. The first strain descriptions appeared in 1991, about the time that 16S rRNA-based approaches for cataloging microbial diversity were revealing the immensity of prokaryotic diversity in the world's oceans. Interest in the clade has risen steadily since the initial discovery of these strains; at present the clade contains 36 described species, representing 17 genera, and literally hundreds of uncharacterized isolates and clone sequences. The first described members were Roseobacter litoralis and Roseobacter denitrificans, both pink-pigmented bacteriochlorophyll a-producing strains isolated from marine algae (99). Subsequent cultivation of clade members, however, revealed that many strains are neither pink nor bacteriochlorophyll a producers (see, e.g., references 20, 41, 43, and 61). With the exceptions of the described strains of the genus Ketogulonicigenium (113) and several clones from a South African gold mine (GenBank accession numbers AF546906, -13, -17, -22 to -24, and -26), the Roseobacter clade is exclusively marine or hypersaline, with characterized isolates demonstrating either a salt requirement or tolerance (see, e.g., references 60 and 62). The described strains demonstrate a diverse range of physiological and morphological features (e.g., gas vacuoles [43], holdfasts [41], poly-β-hydroxybutyrate granules [20, 118], rosette formation [60, 86], toga-like morphologies [39], sulfur metabolism [39, 104], secondary metabolite production [61], methylotrophy [51], and mixotrophy [73]) that suggest unique adaptations to various marine environments. However, few of these traits are representative of the entire clade.

ABUNDANCE AND DISTRIBUTION IN MARINE ENVIRONMENTS

Based on culture collections, 16S rRNA clone libraries, and single-cell analyses, roseobacters have been identified in most marine environments sampled. The group is prevalent in 16S rRNA gene inventories of seawater (Table 1) and marine sediments (Table 2) and is noticeably absent from analogous inventories of freshwater and terrestrial soil environments. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) studies quantifying Roseobacter populations in coastal waters of the southeastern United States and the North Sea indicate different relative population sizes (20% of all bacterial cells versus 8%), but similar seasonal trends (populations highest in summer months and dropping off during winter) (28, 82). Quantitative 16S rRNA gene inventories (Table 1) show that 20 to 30% Roseobacter representation is not uncommon in bacterial communities in the upper mixed layer of the ocean, but depth profiles suggest that populations fall off with depth (Fig. 1) (1, 42, 107). Roseobacters are often most abundant in bacterial communities associated with marine algae, including natural phytoplankton blooms and algal cultures (see, e.g., references 4, 42, 78, 90, and 125). Roseobacter sequences are also abundant in communities associated with polar sea ice (16, 17), diseased corals (21, 80), sponges (111, 119), hypersaline microbial mats (54), cephalopods (cuttlefish and squid) (9, 46), scallop larvae (93), sea grasses (120), and coastal biofilms (24, 25) (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Representation of Roseobacter sequences in quantitative 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from seawater

| Location | Depth (m) | No. of clone sequences | % Roseobacter sequences | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific Ocean | <10 | 16 | 6 | 96 |

| Sargasso Sea | 10 | 14 | 0 | 32 |

| Coastal Pacific Ocean (California) | 10 | 71 | 0 | 26 |

| Sargasso Sea | 2 | 42 | 24 | 77 |

| Coastal Pacific Ocean (Oregon) | 10 | 58 | 7 | 108 |

| Coastal North Atlantic Ocean (France) | <10 | 51 | 18 | 11 |

| Mediterranean Sea (France) | <10 | 50 | 12 | 11 |

| Coastal North Atlantic Ocean (North Carolina) | 10 | 112 | 21 | 88 |

| Coastal North Atlantic Ocean (Long Island Sound) | <10 | 17 | 18 | 33 |

| Coastal Pacific Ocean (California) | <10 | 16 | 25 | 33 |

| Western Mediterranean Sea; free living | Various | 120 | 2 | 1 |

| Coastal Pacific Ocean and Estuary (Washington) | 10 | 189 | 0.4 | 23 |

| Various | Various | 660 | 16 | 36 |

| Coastal North Sea (German Bay) | 1 | 54 | 1.9 | 27 |

| Coastal Pacific Ocean (Oregon) | 10 | 51 | 10 | 89 |

| Coastal North Atlantic Ocean (Long Island Sound) | <1 | 126 | 0 | 56 |

| Antarctic Polar Front | 3,000 | 15 | 0 | 65 |

| Changjiang Estuary (China) | Various | 241 | 19 | 97 |

| Coastal Caribbean Sea; coral reef tracts | <10 | 65 | 6 | 30 |

| Black Sea | Various | 38 | 11 | 116 |

| Coastal North Atlantic Ocean (Massachusetts) | <10 | 2,040 | 4 | 2 |

| Coastal North Atlantic (Portugal) | 0 | 198 | 25 | 48 |

| Coastal Pacific Ocean (California)a | Various | 27,840 | 27 | 107 |

| Sargasso Sea; seven librariesb | <10 | 2,328 | 1.7 | 115 |

| Coastal North Atlantic Ocean (Georgia) | <10 | 794 | 17 | W. B. Whitman et al., unpublished datac |

BAC libraries of coastal Pacific Ocean assemblages.

Shotgun clone libraries of the Sargasso Sea.

Sequences are available at http://simo.marsci.uga.edu.

TABLE 2.

Representation of Roseobacter sequences in bacterial communities from diverse marine environmentsa

| Environment | Approachb | nc | % Roseobacter contributiond | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Sea coastal biofilms | Culture collection | 463 | 1 | 6 |

| Southern U.S. salt marsh biofilms | Clone library | 43 | 67 | 24 |

| FISH | NA | ∼45 | 25 | |

| Dinoflagellate (Alexandrium sp. and Prorocentrum lima) cultures | Culture collection | 44 | 30 | 6 |

| Dinoflagellate (Alexandrium sp. and Scrippsiella trochoidea) cultures | Culture collection | 76 | 55 | 50 |

| Dinoflagellate (Gymnodinium catenatum) cultures | Culture collection | 61 | 31 | 45 |

| Dinoflagellate (Alexandrium sp.) cultures | Culture collection | 31 | 87 | 3 |

| Dinoflagellate (Gymnodinium catenatum) cultures | Culture collection | 61 | 30 | 45 |

| Marine red algae (Prionitis filiformis) | Clone library | 3 | 100 | 8 |

| FISH | NAe | 100 | 8 | |

| Marine green algae (Laminaria sp.) cultures | Culture collection | 17 | 35 | 81 |

| Green algae (Enteromorpha) | Culture collection | 99 | 1 | 81 |

| Diatom (Thalassiosira sp.) cultures | Culture collection | 12 | 8 | 6 |

| North Atlantic algal (Emiliania huxleyi) bloom | FISH | NA | 26 | 42 |

| T-RFLP | NA | 32 | 42 | |

| Clone library | 300 | 5 | 42 | |

| North Sea alga (Emiliania huxleyi) bloom | FISH | NA | 29.5 | 125 |

| Clone library | 50 | 24 | 125 | |

| Phytoplankton bloom off Plymouth, United Kingdom | Clone library | 160 | 9 | 78 |

| Halophila stipulacea (sea grass) | Clone library | 59 | 8 | 120 |

| North Sea bryozoan (Flustra foliacea) | Culture collection | 82 | 10 | 87 |

| Scleractinian corals with black band disease | Clone library | 200 | 24 | 21 |

| Diseased Caribbean coral (Montastrea annularis) | Clone library | 41 | 17 | 80 |

| Loligo pealei (squid) accessory nidamental gland | Clone library | 7 | 100 | 9 |

| Culture collection | 12 | 17 | 9 | |

| Loligo pealei (squid) egg capsules | Clone library | 12 | 17 | 9 |

| Culture collection | 6 | 0 | 9 | |

| Hong Kong soft corals (Dendronephthya sp.) | Culture collection | 11 | 27 | 47 |

| Diseased Eastern oyster (Crassotrea virginica) | Culture collection | 2 | 100 | 13 |

| Sepia officinalis (cuttlefish); accessory nidamental glands | Clone library | 33 | 64 | 46 |

| Antarctic hypersaline microbial mats | Culture collection | 746 | 3 | 114 |

| Hypersaline microbial mat | Culture collection | 3 | 100 | 54 |

| Sea ice, Arctic | Clone library | 192 | 11.5 | 16 |

| FISH | NA | 27 | 16 | |

| Culture collection | 115 | 32 | 16 | |

| Sea ice, Antarctic | Clone library | 198 | 5.5 | 16 |

| FISH | NA | 11.5 | 16 | |

| Culture collection | 87 | 24 | 16 | |

| Sea ice, Arctic | Culture collection | 28 | 7 | 55 |

| Nankai Trough, cold seep sediments, 0-15 cm | Clone library | 57 | 2 | 63 |

| San Franscisco Bay marsh surface sediments | Clone library | 100 | 4 | 110 |

| French Guiana “mobile”mud deposits, 10-30 cm | Clone library | 96 | 10 | 66 |

| Mud volcano sediments near Mt. Etna, Italy; 20 cm | Clone library | 140 | 3 | 121 |

| Antarctic continental shelf sediments, 0-21 cm | Clone library | 936 | 1 | 14 |

| Sea of Okhotsk subfloor sediments; ash layers, 0-58 m | Clone library | 322 | 4 | 52 |

| Mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vent surface sediments | Clone library | 82 | 1 | 64 |

| Gulf of Mexico gas hydrate surface sediments | Clone library | 126 | 4 | 70 |

| Anoxic sediments under microbial mat in coastal saltern (Mediterranean Sea) | Clone library | 92 | 3 | 76 |

| Antarctic coastal surface sediments; petroleum and heavy metal impacted | Clone library | 98 | 2 | 84 |

| Southeastern US coastal sediments, 0-16 cm | Clone library | 1,460 | 2 | W. B. Whitman et al., unpublished dataf |

| Decaying salt marsh grass (Spartina alterniflora) | Clone library | 210 | 15 | W. B. Whitman et al., unpublished dataf |

Excludes seawater samples, which are covered in Table 1.

Studies using the following approaches were included: quantitative 16S rRNA gene clone libraries (“clone library”), FISH, cultivation (“culture collection”), and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms (“T-RFLP”).

Number of total clones or isolates analyzed in 16S rRNA gene clone libraries or by cultivation, respectively.

Contribution of Roseobacter members to total bacterial community analyzed with the various approaches. Clone library and culture collection results are shown as percentage of roseobacters with respect to total clones or isolates analyzed. FISH results are provided as percentage of total community enumerated with a Bacteria-specific probe.

NA, not applicable.

Sequences are available at http://simo.marsci.uga.edu/.

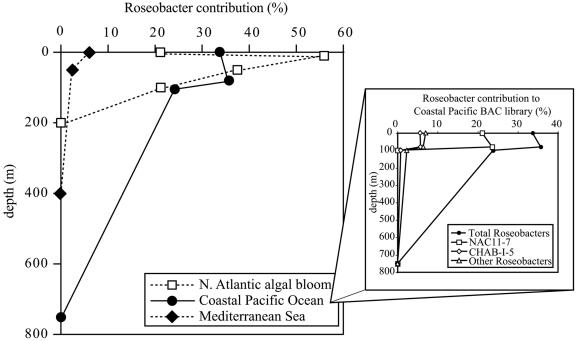

FIG. 1.

Contribution of roseobacters to the total bacterial community at different depths from three sites. Roseobacters associated with a North Atlantic algal bloom community were identified by group-specific 16S rRNA gene oligonucleotide probes (42). Roseobacters associated with western Mediterranean Sea waters were identified by PCR-generated 16S rRNA gene libraries (1). Roseobacters in coastal Pacific Ocean assemblages were identified by BAC libraries (107). The coastal Pacific BAC libraries revealed significant representation of two of the major sequence clusters described in the text (inset).

ARE ISOLATES REPRESENTATIVE OF NATURAL POPULATIONS?

While the culturability of roseobacters is well established, an unresolved question is whether these isolates are truly representative of the populations that are abundant in the environment. Representative strains have been isolated by Brinkmeyer et al. (16), who cultured an Octadecabacter-like strain that comprised ∼20% of an Arctic sea ice bacterial community; by Pinhassi et al. (83), who cultured two Roseobacter strains that by whole genome hybridization contributed 7 and 20% of North Sea and Baltic Sea bacterial communities; and by Fuhrman et al. (31), who cultivated the type strain of Roseovarius nubinhibens, which by whole genome hybridization contributed 20% of a Caribbean Sea bacterial community. In some of these cases, the criterion used to assess taxonomic similarity was not stringent, which is an important issue in light of findings that bacterioplankton with as much as 97% identity of the 16S rRNA gene can be functionally and genetically divergent (72, 91). Other studies have concluded that cultured members of the Roseobacter group are not representative of their environmentally abundant relatives; these studies include those of Eilers et al. (28), who found that specific Roseobacter strains constituted <1% of the bacterial community in the German Bight (even though the group as a whole comprised ∼10% of the community), and of Selje et al. (98), who found a Roseobacter phylotype with wide geographic distribution in the Arctic and Southern Oceans that is not well represented in culture. Thus, there is evidence for both sides of the debate on the ecological relevance of Roseobacter group members that have been gathered into culture collections, with methodology and environment as two potentially important variables.

An alternative approach to addressing the question of ecological relevance of isolates is to determine whether Roseobacter 16S rRNA gene sequences fall into phylogenetic clusters that contain only cultured members, only uncultured members, or both cultured and uncultured members. This approach uses the single criterion of 16S rRNA similarity to determine relatedness and integrates sequences across sites and dates into a single analysis. To this end, we compiled a data set of Roseobacter 16S rRNA gene sequences and identified clusters of sequences with ≥99% identity.

CLUSTERS WITHIN THE CLADE

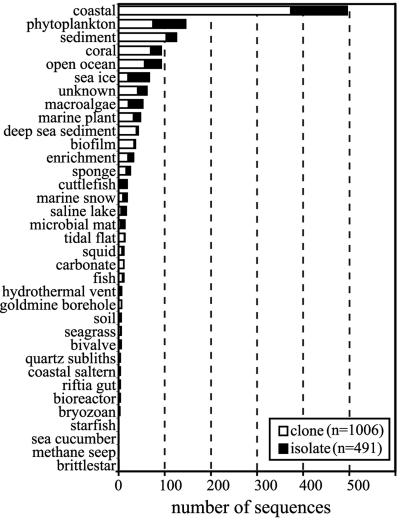

The Roseobacter 16S rRNA gene data set was established with 565 sequences from the Ribosomal Database Project II release 9.22 (RDP) that were assigned to any of the five Roseobacter genera used by the RDP Classifier (Antarctobacter, Roseivivax, Roseobacter, Roseovarius, and Sulfitobacter). An additional 1,251 RDP sequences that were listed as unclassified Rhodobacteraceae family members were screened for Roseobacter clade members based on ≥97% identity in pairwise Smith-Waterman alignments (103) to a reference set of 391 Roseobacter sequences (89 clones and 302 isolates). This reference set included all described strains and all clone and isolate sequences of ≥1,000 bp in length from the RDP-recognized Roseobacter genera. This screen identified 772 additional Roseobacter sequences (61% of the unclassified Rhodobacteraceae sequences). The 1,337 Roseobacter sequences obtained from the RDP accounted for 1% of all bacterial sequences and 9.5% of all α-proteobacterial sequences in RDP release 9.22. An additional 160 Roseobacter sequences were added to the data set because they represented described genera not in the RDP 9.22 release (n = 3), were identified in the Sargasso Sea metagenomic library (n = 35) (115), or were part of the Sapelo Island Microbial Observatory 16S rRNA sequence database (n = 122) (http://simo.marsci.uga.edu). The sequence data set (n = 1,497) represents clones and isolates from diverse origins, with the overwhelming majority originating in coastal seawater samples (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Type (clone or isolate) and origin (environment sampled) of 16S rRNA gene sequences in the Roseobacter data set. Definitions for environments are as follows: “coastal,” seawater samples collected from intertidal regions to edges of continental shelves; “open ocean,” seawater samples taken beyond continental shelves; “deep sea sediment,” samples collected from marine sediments at water depths of >1,000 m; “phytoplankton,” diatoms, dinoflagellates, and microalgae; “marine plant,” vascular coastal plant; “unknown,” insufficient information to determine source environment.

Sequences in the Roseobacter data set were then used to define phylogenetic clusters within the clade, based on a 1% consensus rule (≥99% sequence similarity). This criterion is more likely to group organisms with similar ecological niches and physiological adaptations than the 97% “species” criterion (2). Initial analyses suggested that two modifications were needed to obtain meaningful clusters from this diverse data set. First, to reduce biases in cluster identification due to differences in sampling efforts among studies, the Roseobacter sequence data set was culled to remove similar sequences derived from the same sample. Second, to reduce the influence of short sequences, the Roseobacter reference set (described above) was used to anchor clusters with nearly full-length sequences from acknowledged Roseobacter lineages. The nonredundant data set (n = 974) was subjected to pairwise Smith-Waterman alignments to sequences in the Roseobacter reference set, and sequences were placed in the same cluster if they had ≥99% identity to any member of that cluster.

Half (55%) of the Roseobacter sequences, representing 248 clones and 292 isolates, clustered into groups containing a reference sequence. These sequences formed 141 clusters that ranged in size from 1 to 56 members. Most of these sequences (79%) fell into 51 clusters of ≥3 nonredundant members (see Table S2 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The majority (80%) of these 51 clusters contained both clone and isolate representatives, 8 clusters (17%) were comprised solely of isolates, and 2 clusters contained only clone representatives. The remaining sequences fell into 90 clusters of one (n = 67) or two (n = 23) members. Most of these clusters (72%) contained only isolates, 19 contained only clones, and 6 contained both a clone and an isolate.

The other half of the sequences in the nonredundant data set (323 clones and 111 isolates) did not cluster with a Roseobacter reference sequence. In order to determine whether these sequences would form clusters among themselves, a separate series of pairwise alignments were run on solely these sequences. Of these sequences, 358 (82%) were <99% similar to any other sequence; most of these singleton sequences (80%) are partial sequences (<1,000 bp), and over half (73%) represent clones.

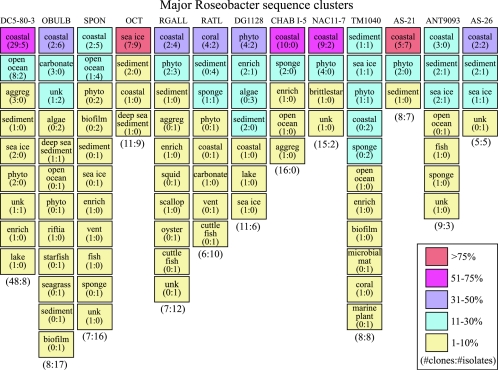

To specifically address the issue of whether the cultured strains are representative of environmental Roseobacter populations, we first focused on the large clusters containing ≥10 nonredundant members (Fig. 3). Together, these 13 major clusters contain 251 sequences (26% of the nonredundant Roseobacter data set). Three of the major clusters (DC5-80-3, NAC11-7, and ANT9093 [Fig. 3]) are comprised primarily of clones (≥75%), and one (CHAB-I-5) is composed exclusively of clones. Two major clusters (OBULB and SPON) contain mostly isolate sequences (≥68%), while the remaining major clusters (7 of 13) are fairly well represented by both clones and isolates (e.g., AS-26, AS-21, and TM1040 [Fig. 3]).

FIG. 3.

Type (clone or isolate) and origin (environment sampled) of 16S rRNA sequences in each of the major Roseobacter sequence clusters. The percentage of sequences from a given habitat for each sequence cluster is shown by color-coded boxes. The numbers of nonredundant clones and/or isolate sequences for a given habitat are shown in parenthesis (number of clones:number of isolates); at the bottom of each column are the total numbers of nonredundant sequences for each cluster. Abbreviations: aggreg, marine aggregates; phyto, phytoplankton; unk, unknown; enrich, seawater enrichments; vent, hydrothermal vents; and carbonate, deep-sea carbonate crusts. See the Fig. 2 legend for environment definitions.

Because the clusters were defined in an associative fashion (i.e., membership required ≥99% similarity to only one other member), sequences in the same cluster can have 16S rRNA sequences similarities of <99%. Therefore, we also addressed the issue of phylogenetic congruence between cultured and cloned Roseobacter members by determining whether individual clone sequences have ≥99% similarity to any isolated strain. Fifty percent of all nonredundant clone sequences (288 of 571) clustered with at least one other sequence. Of these, 64% (184 sequences) were ≥99% similar to an isolate sequence, while 36% were not (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). There were several instances of 100% identity in pairwise alignments between nonredundant sequences (n = 121). One-third of these identical pairs (34%) involved a clone and an isolate, one-third (30%) involved two isolates, and one-third (35%) involved two clones. When all of the nonredundant Roseobacter clones in the data set are considered, 68% did not cluster with ≥99% similarity to an isolate. These results are greatly influenced by sampling effort and available sequences up to the point of data set compilation. Nonetheless, this analysis estimates that for two-thirds (68%) of the Roseobacter diversity identified thus far, it is not yet possible to access relevant physiological information through studies of cultured organisms.

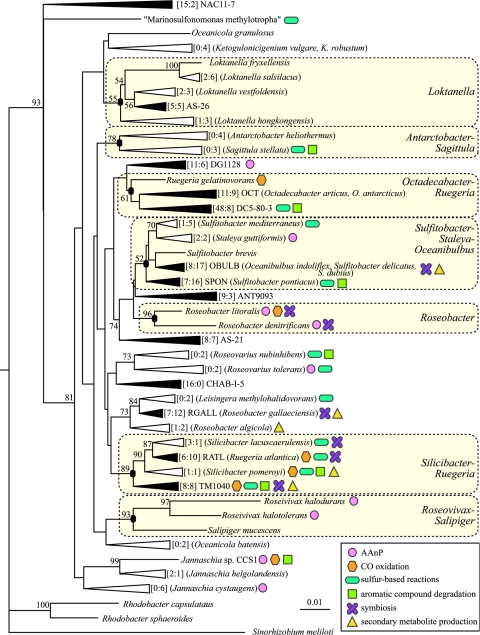

Phylogeny of the Roseobacter group is somewhat problematic. This is primarily due to the assignment of genus names to more than one monophyletic lineage (e.g., Roseobacter and Ruegeria) and instability in tree branching patterns. Nonetheless, it is possible to identify robust superlineages within the clade, including the Loktanella group, the Antarctobacter-Sagittula group, the Octadecabacter-Ruegeria group, the Sulfitobacter-Staleya-Oceanibulbus group, the Roseobacter group, the Silicibacter-Ruegeria group, and the Roseivivax-Salipiger group (74). Of these superlineages, only three (the Octadecabacter-Ruegeria group, the Sulfitobacter-Staleya-Oceanibulbus group, and the Silicibacter-Ruegeria group) are well represented by both clones and isolates (i.e., >30% of nonredundant members are clones) (Fig. 4). Both the Antarctobacter-Sagittula and Roseobacter groups are presently comprised solely of isolates.

FIG. 4.

The 41 major lineages of the Roseobacter clade. The tree includes all currently described genera and the 13 major clusters defined in the text. Filled triangles represent clusters of ≥10 nonredundant members, and unfilled triangles represent clusters with <10 members. Described strains within each cluster are shown in parentheses. Robust phylogenetic lineages are indicated with filled ovals at branch nodes and vertical black lines. Numbers of clone and isolate sequences representing each cluster are provided in brackets ([number of clones:number of isolates]). Colored symbols represent evidence for the indicated physiologies. The tree is based on the following sequences: NAC11-7 (GenBank accession number AF245635), “M. methylotropha” (U62894), O. granulosus (AY424896), K. robustum (AF136850), L. fryxellensis (AJ582225), L. salsilacus (AJ582228), L. vestfoldensis (AJ582226), L. hongkongensis (AY600301), AS-26 (AJ391187), S. mediterraneus (Y17387), S. guttiformis (Y16427), S. pontiacus (Y13155), S. brevis (Y16425), O. indoliflex (AY550939), R. litoralis (X78312), R. denitrificans (M96746), ANT9093 (AY167254), AS-21 (AJ391182), O. batensis (AY424898), DG1128 (AY258100), R. gelatinovorans (D88523), O. antarcticus (U14583), DC5-80-3 (AY145589), R. nubinhibens (AF098495), R. tolerans (Y11551), CHAB-I-5 (AJ240910), S. lacuscaerulensis (U77644), R. atlantica (D88526), S. pomeroyi (AF098491), TM1040 (AY332662), L. methylohalidovorans (AY005463), R. gallaeciensis (Y13244), R. algicola (X78313), R. halodurans (D85829), R. halotolerans (D85831), S. mucescens (AY527274), “C. thiooxidans” (AY639887), A. heliothermus (Y11552), S. stellata (U58356), Jannaschia sp. strain CCS1 (www.jgi.doe.gov), J. helgolandensis (AJ438157), J. cystaugens (AB121782), R. capsulatus (D16427), and R. sphaeroides (D16418). S. meliloti (D14509) served as the outgroup. The tree is based on positions 92 to 1443 of the 16S rRNA gene (E. coli numbering system). Prior to analysis, a filter was applied to the aligned sequences to exclude positions with <50% conservation. The tree was constructed using Phylip (29) and the neighbor-joining method. The bar represents Jukes-Cantor evolutionary distances. Bootstrap values of >50% are shown at branch nodes (100 iterations).

PATTERNS IN HABITAT AND DISTRIBUTION

We examined the source environment and geographical distribution of the nonredundant Roseobacter sequences in the data set to determine if characteristic habitats or ecological niches could be identified for specific phylogenetic clusters within the group. Source environments were inventoried using primary literature references and unpublished RDP entries (Fig. 3). To focus on larger groups for which patterns could be studied, we analyzed only the 13 major clusters (i.e., those consisting of ≥10 nonredundant members and containing at least one nearly full-length reference sequence), which represented 26% of the nonredundant data set. A similar analysis using the less stringent criterion of ≥3 nonredundant members per cluster is provided in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

DC5-80-3 cluster.

The DC5-80-3 group represents the largest of all the major clusters, with 56 nonredundant members that are primarily clone sequences (86%) from planktonic habitats (79%) (Fig. 3). This cluster is the only one for which a systematic global distribution has been determined. Selje et al. (98) identified members of this group in surface waters (to 40 m) of temperate to polar oceans of both hemispheres and to depths of 2,300 m and 1,000 m in the Arctic and Southern Oceans, respectively. Based on a quantitative PCR assay, this group was estimated to comprise ∼20% of all bacteria in the Southern Ocean (98), 5% of bacterioplankton 16S rRNA genes in a clone library from a Portuguese estuary (48), and ≥5% of bacterioplankton 16S rRNA genes in a clone library constructed from coastal North Carolina seawater (88). DC5-80-3 cluster members have yet to be detected in samples from tropical and subtropical waters (98).

OBULB and SPON clusters.

The OBULB and SPON clusters fall within the phylogenetically cohesive Sulfitobacter- Staleya-Oceanibulbus superlineage (Fig. 4) and are composed largely of isolate sequences, with ∼70% of the sequences derived from cultivated representatives. Nearly a third (32%) of the nonredundant OBULB sequences are from coastal seawater samples (Fig. 3). Roughly another third (29%) are from sea floor environments (52). The OBULB cluster contains three described strains: Oceanibulbus indoliflex, cultivated from coastal North Sea waters (118), and Sulfitobacter delicatus and Sulfitobacter dubius, isolated from sea grass and starfish, respectively (53).

The representative described strain of the SPON cluster, Sulfitobacter pontiacus, was retrieved from the oxic/anoxic interface in the Black Sea (105). Six additional sequences are derived from geographically distinct coastal environments. In addition, five open ocean isolates belong to this major cluster. The remaining nonredundant sequences are derived from diverse environments, ranging from deep-sea vents to marine sponges (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

OCT cluster.

The OCT cluster is well represented by both clone (55%) and isolate (45%) sequences, including two described strains isolated from sea ice, Octadecabacter antarcticus and Octadecabacter arcticus (43). All but two of the 20 nonredundant representatives were obtained from polar environments, suggesting that members may be adapted to cold environments and to sea ice in particular. In fact, members of the OCT cluster have been found to comprise over 20% of sea ice microbial communities (16). The other two OCT cluster members are clone sequences derived from temperate coastal waters and deep-sea sediments (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

RGALL cluster.

The RGALL cluster (Fig. 3) is well represented by cultivated strains (68% of all sequences), many of which are found in association with eukaryotic marine organisms. This includes the described strain Roseobacter gallaeciensis isolated from larval cultures of the scallop Pecten maximus (92), an isolate recovered from larval cultures of the oyster Ostrea edulis, an isolate from larval cultures of the marine fish Scophthalmus maximus (49), and a clone from the egg capsule of the squid Loligo pealei (9). Two additional strains were isolated from dinoflagellates, and two clones were obtained from marine phytoplankton. The remaining members derive from coastal seawater (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (Fig. 4).

CHAB-I-5 cluster.

The CHAB-I-5 cluster is currently represented only by clone sequences, more than half of which (56%) derive from coastal seawater (Fig. 3). Members are represented in shotgun clone libraries from coastal Pacific Ocean waters and Sargasso Sea surface waters (107, 115), two datasets that are largely free of the biases associated with PCR-based studies. Nearly 6% of all 16S rRNA gene-containing clones from libraries constructed from surface and 80-m-depth waters of Monterey Bay, Calif., were traced to this major Roseobacter cluster (107), but none were identified in libraries from greater depths (Fig. 1). In both the coastal California and Sargasso Sea metagenomic libraries, this cluster constituted ∼20% of the Roseobacter 16S rRNA gene-containing clones (73, 107, 115).

NAC11-7 cluster.

The NAC11-7 cluster (Fig. 3) is represented primarily by clone sequences (88%), several of which are associated with algae and algal blooms. The two isolated representatives were cultured from coastal seawater by using oligotrophic media (102). Four clones derive from bacterial communities associated with North Atlantic algal blooms (42, 78, 125). Several studies suggest that NAC11-7 representatives are often prevalent in such assemblages, making up nearly a quarter (12 of 50) of the bacterioplankton clones sequenced from a North Sea Emiliana huxleyi bloom (125) and 15 of 160 clones sequenced from a bloom-associated community off Plymouth, United Kingdom (78). Suzuki et al. (107) reported that this cluster comprises 22% of all 16S rRNA gene-containing bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones (and ∼65% of Roseobacter 16S rRNA gene-containing BACs) from surface and 80-m-depth libraries of coastal California waters that are typically characterized by phytoplankton blooms (107). Nine of the 15 nonredundant clone members were not specifically associated with algal cells or blooms but were obtained from near-shore seawater (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Other major clusters.

The DG1128 cluster is well represented by sequences derived from macroalgae and phytoplankton (95). Many members of the RATL cluster were obtained from corals. The ANT9093 cluster is comprised of members from diverse environments, including polar sea ice, sediments, and sponges. Members of the TM1040, AS-21, and AS-26 clusters are typically derived from coastal seawater or sediment (Fig. 3 and 4; see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

In short, a few of the major clusters show fairly predictable patterns in habitat (e.g., OCT cluster members are often found in cold environments, and AS-21 members are often coastal), while several more exhibit predominance of a single habitat type (e.g., DG1128 members are frequently associated with marine phytoplankton and RATL members with corals). However, the variability evident within these clusters suggests that 16S rRNA gene sequence data alone are not a reliable predictor of ecological niche.

EMERGING PHYSIOLOGIES

Despite the metabolic diversity harbored within the Roseobacter clade, several physiologies appear to be characteristic of the lineage. To look for patterns within the Roseobacter clusters of phenotypes of ecological interest, we examined the distribution of known physiological attributes among group members. For this analysis, we focused on clusters for which physiological information was available, including (i) major clusters that contained ≥10 nonredundant members (n = 13), (ii) clusters that contained a described strain (n = 33), and/or (iii) clusters that contained a strain for which a genome sequence is available (n = 3). Forty-one clusters representing 337 nonredundant sequences (174 clones and 163 isolates) met at least one of these criteria (Fig. 4).

Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophy.

The first described members of the Roseobacter clade, and the inspiration for the name, were among the earliest recognized aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs (AAnPs). These bacteriochlorophyll a-containing strains are able to derive energy from light without the generation of oxygen. R. denitrificans and R. litoralis (99, 101) are physiologically similar to their anaerobic relatives in the purple sulfur bacteria. However, in contrast to the case for purple sulfur bacteria, there is currently little evidence for CO2 fixation beyond what might be attributable to anaplerotic reactions (100). This suggests that Roseobacter AAnPs are photoheterotrophic, although this issue has not yet been conclusively resolved. Seven of the 41 Roseobacter lineages contain phototrophic members (Fig. 4). However, there is little indication that the trait segregates into distinct clusters within the clade (6).

Although AAnPs were initially considered atypical marine bacteria restricted to unusual habitats, the discovery of bacteriochlorophyll a in ocean surface waters (59) along with the subsequent retrieval of both photosynthetic reaction center (pufLM) and bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis (bch) genes from bacterioplankton (10, 79) established the ecological relevance of AAnPs in the ocean. One biogeochemical implication of Roseobacter-mediated phototrophy in surface seawater is an enhanced growth yield on available organic matter, which could provide an advantage to the organism in carbon-limited environments as well as affect the magnitude and dynamics of the organic carbon reservoir in the ocean.

Sulfur transformations.

Key transformations for the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur that involve both organic and inorganic compounds have been identified in Roseobacter clade members and recently reviewed by Moran et al. (74). Isolates of the clade were the first marine strains found to simultaneously possess two key pathways for the degradation of the sulfur-based algal osmolyte dimethylsulfoniopropionate (40). These competing pathways may play a role in determining the balance between the incorporation of sulfur into the marine microbial food web (the demethylation/demethiolation pathway) and the release of sulfur in the form of the climate-influencing gas dimethyl sulfide (the cleavage pathway) (57, 122). Field studies show that clade members are prevalent and active members of dimethylsulfoniopropionate-assimilating communities in the surface ocean (42, 67, 117). In addition, many Roseobacter strains are capable of transforming other organic sulfur compounds, including dimethyl sulfide, methanethiol, methanesulfonate, and dimethyl sulfoxide (39, 40, 51, 94).

Clade members also harbor abilities to transform inorganic forms of sulfur, including elemental sulfur, sulfide, sulfite, and thiosulfate (see, e.g., references 39, 73, and 104-106). These pathways facilitate sulfur-based lithoheterotrophy, which has been demonstrated in several Roseobacter strains (53, 73, 104). Inorganic sulfur oxidation is an important process in many coastal and benthic marine environments (e.g., sediments and sulfide-rich habitats), and the recent discovery of genes encoding sulfur oxidation enzymes (sox genes) in open ocean bacterioplankton (73, 115) suggests a previously unrecognized role for sulfur oxidation in these systems as well. Reactions involving sulfur (organic and inorganic) have been found in 12 of the 41 major Roseobacter lineages (Fig. 4).

Carbon monoxide oxidation.

Members of the Roseobacter clade have been implicated in the consumption of carbon monoxide (CO), an important greenhouse gas that forms in seawater when sunlight oxidizes marine dissolved organic matter (123). Evidence that clade members are participating in biological CO oxidation in the ocean includes the demonstration that strains can oxidize CO in culture (58, 112) and that the roseobacter Silicibacter pomeroyi harbors two CO oxidation (cox) operons in its genome (73). S. pomeroyi has been demonstrated to oxidize CO at concentrations typically measured in coastal and open ocean surface waters (10 nM and 2 nM, respectively). However, it differs from previously characterized CO oxidizers in that it does not grow autotrophically and instead uses CO as a supplementary energy source during heterotrophic growth (73). Evidence for CO oxidation has been found in six of the major Roseobacter lineages thus far (Fig. 4), and CO oxidation may prove to be a successful ecological strategy for planktonic roseobacters in sunlit surface waters.

Aromatic compound degradation.

Vascular plant-derived aromatic compounds are often a significant component of the carbon pool in coastal environments where roseobacters are abundant (75). Based on evidence that clade members might play a role in the transformation of lignin (38), a gene encoding a key ring-cleaving enzyme of the β-ketoadipate pathway (pcaH) was identified in 16 of 19 Roseobacter strains by a PCR assay (18, 19). Enrichments of a salt marsh bacterial community with fused ring and hydroxy-, methyl-, and amino-substituted ring structures showed that over half of the 120 pcaH genes sequenced could be traced to the Roseobacter clade (19). Those findings complemented phenotypic assays carried out on cultivated organisms and indicated that many roseobacters are capable of using aromatic compounds as primary growth substrates (18, 19). Evidence for aromatic compound degradation has been identified in 7 of the 41 major Roseobacter lineages (Fig. 4).

The genome sequence of S. pomeroyi has revealed that in addition to the widely distributed pca pathway, other catabolic routes for phenolics may be represented in the clade (73). These include the gentisate pathway, which is widespread in phylogenetically diverse soil bacteria (124), and a novel pathway for the aerobic degradation of benzoate (35) that may also be present in a limited number of α- and β-Proteobacteria from soil.

Symbiotic relationships.

Roseobacter strains form symbiotic relationships with diverse eukaryotic marine organisms. Ashen and Goff (8) identified Roseobacter phylotypes in three gall-bearing species of the marine red alga Prionitis. Clade members are also dominant components of bacterial assemblages associated with the reproductive accessory nidamental glands in the cephalopods Loligo pealei (squid) and Sepia officinialis (cuttlefish) (9, 46). Roseobacters have developed close associations with Pfiesteria and Pfiesteria-like species, where they are found within the nutrient-rich phycosphere of, or polarly attached to, these dinoflagellates (4). Alavi (5) recently identified a complex interaction between one such isolate (MA03), the dinoflagellate Pfiesteria piscicida, and the green alga Rhodomonas, in which MA03 positively affects the predation rate of the dinoflagellate on the alga. In addition, the Roseobacter strain Silicibacter strain TM1040 has been shown to exhibit chemotaxis toward compounds typically released from Pfiesteria (69).

Although not as commonly reported, pathogenic activities have also been attributed to clade members. Roseobacter strains and phylotypes have been implicated as causative agents of juvenile oyster disease in the Eastern oyster (12) and of black band disease in scleractinian corals (21, 80). While symbiotic interactions involving roseobacters are prevalent, the extents and bases of most of these relationships are not yet fully understood.

Secondary metabolite production.

In bacteria, secondary metabolite production is often the basis for chemical signaling and defense, as well as host-microbe interactions. Evidence suggests that many roseobacters, particularly those within the RGALL lineage, produce bioactive compounds. Hjelm et al. (49) identified RGALL lineage members that were antagonistic against fish larval bacterial pathogens. R. galleaeciensis was demonstrated to have similar probiotic effects on scallop larvae (92). Another RGALL isolate produces a novel antibiotic, tropodithietic acid, which is effective against marine bacteria and algae (15). Finally, a strain isolated from the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium affine produces a suite of paralytic shellfish toxins (34).

Other Roseobacter lineages also harbor secondary metabolite producers (Fig. 4). Roseobacter algicola, isolated from the toxin-producing dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima, produces the shellfish poison okadaic acid (61). Oceanibulbus indoliflex produces indole, indole derivatives, cyclic dipeptides, and the antimicrobial compound tryptanthrin (118).

Cell-density-dependent regulation via the LuxIR system is mediated by a specific class of secondary metabolites that have been identified in Roseobacter strains. Gram et al. (44) found that three of five Roseobacter isolates from marine snow produced LuxR-activating acylated homoserine lactones (AHLs). Mitova et al. (71) identified a sponge isolate (within the TM1040 cluster) capable of producing 10 distinct cyclic dipeptides structurally similar to the bioactive AHLs. Finally, evidence of the Lux system has also been found in S. pomeroyi, which has two luxI homologs that generate functional AHLs when expressed in Escherichia coli (73). Density-dependent signaling systems have been implicated in biofilm formation, exoenzyme production, and antibiotic production, all of which are activities exhibited by clade members (15, 22, 24, 25, 62, 118).

GENOMIC FEATURES

The roseobacters analyzed thus far have large genomes (averaging 4.4 Mb) and rRNA operon copy numbers ranging from 1 to 4 (average, 2.7) (73, 85; www.jgi.doe.gov). These traits are consistent with the metabolic diversity and ease of cultivation that are characteristic of the group. Plasmids are common among roseobacters and can exhibit a linear conformation (68, 73, 85, 113). In some strains, a significant amount of the genome content is plasmid borne (e.g., 5% in R. litoralis and 10% in S. pomeroyi), and ecologically relevant gene sets have been traced to plasmids in several strains (e.g., pca, puf, and nir [nitrite reduction] genes) (73, 85). While plasmid mobility has yet to be examined in Roseobacter strains, these extrachromosomal genetic elements may contribute to the physiological diversity evident within the clade.

The first genome sequence of Roseobacter clade member S. pomeroyi provided insight into the ecology and physiology of this successful marine clade (73). As the sequences of 2 additional isolates are near completion (www.jgi.doe.gov) and 13 more isolates are in the early stages of sequencing (www.moore.org/microgenome/), evidence for additional physiologies previously unsuspected in this lineage may emerge.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

As the physiology and ecology of cultured Roseobacter group members continue to be revealed, extrapolation of this information to uncultured relatives remains a central challenge. The extent of this challenge is best illustrated by the two-thirds of clade members that harbor a significant fraction of the group's phylogenetic diversity but presently have no close relatives in culture. Yet the opposite perspective is that with one-third of the known diversity represented by cultivated strains already in hand, this clade is one of the most accessible of the major marine taxa. For those major clusters that are currently well represented by cultured strains, considerable diversity is emerging with respect to habitat (Fig. 3) and physiology (Fig. 4). This makes extrapolation of ecological roles based on 16S rRNA gene sequences alone unlikely, at least given current levels of resolution of both physiology and phylogenetic diversity within the clade. Insights gained from cultured relatives will undoubtedly continue to serve as the basis of testable hypotheses for illuminating the ecological roles of this fundamentally important group of marine bacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Wade Sheldon and Chris Lasher for their assistance with the computational analysis of the 16S rRNA gene data.

This work was supported by funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and NSF grant MCB-0315200 (to M.A.M.). A.B. was supported by NSF Postdoctoral Research Fellowship DBI-0200164.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acinas, S. G., J. Antón, and F. Rodríguez-Valera. 1999. Diversity of free-living and attached bacteria in offshore western Mediterranean waters as depicted by analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:514-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acinas, S. G., V. Klepac-Ceraj, D. E. Hunt, C. Pharino, I. Ceraj, D. L. Distel, and M. F. Polz. 2004. Fine-scale phylogenetic architecture of a complex bacterial community. Nature 430:551-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi, M., T. Kanno, R. Okamoto, S. Itakura, M. Yamaguchi, and T. Nishijima. 2003. Population structure of Alexandrium (Dinophyceae) cyst formation-promoting bacteria in Hiroshima Bay, Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6560-6568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alavi, M., T. Miller, K. Erlandson, R. Schneider, and R. Belas. 2001. Bacterial community associated with Pfiesteria-like dinoflagellate cultures. Environ. Microbiol. 3:380-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alavi, M. R. 2004. Predator/prey interaction between Pfiesteria piscicida and Rhodomonas mediated by a marine alpha proteobacterium. Microb. Ecol. 47:48-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allgaier, M., H. Uphoff, A. Felske, and I. Wagner-Döbler. 2003. Aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis in Roseobacter clade bacteria from diverse marine habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5051-5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Althoff, K., R. Schütt, R. Steffen, R. Batel, and W. E. G. Müller. 1998. Evidence for a symbiosis between bacteria of the genus Rhodobacter and the bacteria of the marine sponge Halichondria panicea: harbor for putatively toxic bacteria? Mar. Biol. 130:529-536. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashen, J. B., and L. J. Goff. 2000. Molecular and ecological evidence for species specificity and coevolution in a group of marine algal-bacterial symbioses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3024-3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbieri, E., B. J. Paster, D. Hughes, L. Zurek, D. P. Moser, A. Teske, and M. L. Sogin. 2001. Phylogenetic characterization of epibiotic bacteria in the accessory nidamental gland and egg capsules of the squid Loligo pealei (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae). Environ. Microbiol. 3:151-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Béjà, O., E. V. Koonin, L. Aravind, L. T. Taylor, H. Seitz, J. L. Stein, D. C. Bensen, R. A. Feldman, R. V. Swanson, and E. F. DeLong. 2002. Comparative genomic analysis of archaeal genotypic variants in a single population and in two different oceanic provinces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:335-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benlloch, S., F. Rodríguez-Valera, and A. J. Martinez-Murcia. 1995. Bacterial diversity in two coastal lagoons deduced from 16S rDNA PCR amplification and partial sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 18:267-279. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boettcher, K. J., B. J. Barber, and J. T. Singer. 2000. Additional evidence that juvenile oyster disease is caused by a member of the Roseobacter group and colonization of nonaffected animals by Stappia stellulata-like strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3924-3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boettcher, K. J., B. J. Barber, and J. T. Singer. 1999. Use of antibacterial agents to elucidate the etiology of juvenile oyster disease (JOD) in Crassostrea virginica and numerical dominance of an α-Proteobacterium in JOD-affected animals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2534-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowman, J. P., and R. D. McCuaig. 2003. Biodiversity, community structural shifts, and biogeography of prokaryotes within Antarctic continental shelf sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2463-2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinkhoff, T., G. Bach, T. Heidorn, L. F. Liang, A. Schlingloff, and M. Simon. 2004. Antibiotic production by a Roseobacter clade-affiliated species from the German Wadden Sea and its antagonistic effects on indigenous isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2560-2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinkmeyer, R., K. Knittel, J. Jürgens, H. Weyland, R. Amann, and E. Helmke. 2003. Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in Arctic versus Antarctic pack ice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6610-6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown, M. V., and J. P. Bowman. 2001. A molecular phylogenetic survey of sea-ice microbial communities (SIMCO). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 35: 267-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchan, A., L. S. Collier, E. L. Neidle, and M. A. Moran. 2000. Key aromatic-ring-cleaving enzyme, protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase, in the ecologically important marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4662-4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchan, A., E. L. Neidle, and M. A. Moran. 2001. Diversity of the ring-cleaving dioxygenase gene pcaH in a salt marsh bacterial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5801-5809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho, J.-C., and S. J. Giovannoni. 2004. Oceanicola granulosus gen. nov., sp. nov. and Oceanicola batsensis sp. nov., poly-β-hydroxybutyrate-producing marine bacteria in the order ‘Rhodobacterales.’ Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooney, R. P., O. Pantos, M. D. A. L. Tissier, M. R. Barer, A. G. O'Donnell, and J. C. Bythell. 2002. Characterization of the bacterial consortium associated with black band disease in coral using molecular microbiological techniques. Environ. Microbiol. 4:401-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cottrell, M. T., D. N. Wood, L. Yu, and D. L. Kirchman. 2000. Selected chitinase genes in cultured and uncultured marine bacteria in the α- and γ-subclasses of the Proteobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1195-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crump, B. C., E. V. Armbrust, and J. A. Baross. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of particle-attached and free-living bacterial communities in the Columbia River, its estuary, and the adjacent coastal ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3192-3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dang, H. Y., and C. R. Lovell. 2000. Bacterial primary colonization and early succession on surfaces in marine waters as determined by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dang, H. Y., and C. R. Lovell. 2002. Seasonal dynamics of particle-associated and free-living marine Proteobacteria in a salt marsh tidal creek as determined using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Environ. Microbiol. 4:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delong, E. F., D. G. Franks, and A. L. Alldredge. 1993. Phylogenetic diversity of aggregate-attached vs free-living marine bacterial assemblages. Limnol. Oceanogr. 38:924-934. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eilers, H., J. Pernthaler, F. O. Glöckner, and R. Amann. 2000. Culturability and in situ abundance of pelagic bacteria from the North Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3044-3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eilers, H., J. Pernthaler, J. Peplies, F. O. Glöckner, G. Gerdts, and R. Amann. 2001. Isolation of novel pelagic bacteria from the German bight and their seasonal contributions to surface picoplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5134-5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5:164-166. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frias-Lopez, J., A. L. Zerkle, G. T. Bonheyo, and B. W. Fouke. 2002. Partitioning of bacterial communities between seawater and healthy, black band diseased, and dead coral surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2214-2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuhrman, J. A., S. H. Lee, Y. Masuchi, A. A. Davis, and R. M. Wilcox. 1994. Characterization of marine prokaryotic communities via DNA and RNA. Microb. Ecol. 28:133-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuhrman, J. A., K. McCallum, and A. A. Davis. 1993. Phylogenetic diversity of subsurface marine microbial communities from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1294-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuhrman, J. A., and C. C. Ouverney. 1998. Marine microbial diversity studied via rRNA sequences: cloning results from coastal waters and counting of native archaea with fluorescent single cell probes. Aquat. Ecol. 32:3-15. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallacher, S., K. Flynn, J. Franco, E. Brueggemann, and H. Hines. 1997. Evidence for production of paralytic shellfish toxins by bacteria associated with Alexandrium spp. (Dinophyta) in culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:239-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gescher, J., A. Zaar, M. Mohamed, H. Schägger, and G. Fuchs. 2002. Genes coding for a new pathway of aerobic benzoate metabolism in Azoarcus evansii. J. Bacteriol. 184:6301-6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giovannoni, S. J., and M. Rappé. 2000. Evolution, diversity, and molecular ecology of marine prokaryotes, p. 47-84. In D. L. Kirchman (ed.), Microbial ecology of the oceans. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 37.González, J., and M. Moran. 1997. Numerical dominance of a group of marine bacteria in the α-subclass of the class Proteobacteria in coastal seawater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4237-4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.González, J., W. Whitman, R. Hodson, and M. Moran. 1996. Identifying numerically abundant culturable bacteria from complex communities: an example from a lignin enrichment culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4433-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.González, J. M., J. S. Covert, W. B. Whitman, J. R. Henriksen, F. Mayer, B. Scharf, R. Schmitt, A. Buchan, J. A. Fuhrman, R. P. Kiene, and M. A. Moran. 2003. Silicibacter pomeroyi sp. nov. and Roseovarius nubinhibens sp. nov., dimethylsulfoniopropionate-demethylating bacteria from marine environments. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1261-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.González, J. M., R. P. Kiene, and M. A. Moran. 1999. Transformation of sulfur compounds by an abundant lineage of marine bacteria in the alpha-subclass of the class Proteobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65: 3810-3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.González, J. M., F. Mayer, M. A. Moran, R. E. Hodson, and W. B. Whitman. 1997. Sagittula stellata gen. nov. sp. nov., a lignin-transforming bacterium from a coastal environment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 47:773-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.González, J. M., R. Simó, R. Massana, J. S. Covert, E. O. Casamayor, C. Pedrós-Alió, and M. A. Moran. 2000. Bacterial community structure associated with a dimethylsulfoniopropionate-producing North Atlantic algal bloom. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4237-4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gosink, J. J., R. P. Herwig, and J. T. Staley. 1997. Octadecabacter arcticus gen. nov., sp. nov., and O. antarcticus, sp. nov., nonpigmented, psychrophilic gas vacuolate bacteria from polar sea ice and water. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 20:356-365. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gram, L., H. P. Grossart, A. Schlingloff, and T. Kiørboe. 2002. Possible quorum sensing in marine snow bacteria: production of acylated homoserine lactones by Roseobacter strains isolated from marine snow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4111-4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green, D. H., L. E. Llewellyn, A. P. Negri, S. I. Blackburn, and C. J. S. Bolch. 2004. Phylogenetic and functional diversity of the cultivable bacterial community associated with the paralytic shellfish poisoning dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47:345-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grigioni, S., R. Boucher-Rodoni, A. Demarta, M. Tonolla, and R. Peduzzi. 2000. Phylogenetic characterisation of bacterial symbionts in the accessory nidamental glands of the sepioid Sepia officinalis (Cephalopoda:Decapoda). Mar. Biol. 136:217-222. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harder, T., S. C. K. Lau, S. Dobretsov, T. K. Fang, and P.-Y. Qian. 2003. A distinctive epibiotic bacterial community on the soft coral Dendronephthya sp. and antibacterial activity of coral tissue extracts suggest a chemical mechanism against bacterial epibiosis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 43:337-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henriques, I. S., A. Almeida, A. Cunha, and A. Correia. 2004. Molecular sequence analysis of prokaryotic diversity in the middle and outer sections of the Portuguese estuary Ria de Aveiro. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hjelm, M., O. Bergh, A. Riaza, J. Nielsen, J. Melchiorsen, S. Jensen, H. Duncan, P. Ahrens, T. H. Birkbeck, and L. Gram. 2004. Selection and identification of autochthonous potential probiotic bacteria from turbot larvae (Scophthalmus maximus) rearing units. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27:360-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hold, G. L., E. A. Smith, M. S. Rappé, E. W. Maas, E. R. B. Moore, C. Stroempl, J. R. Stephen, J. I. Prosser, T. H. Birkbeck, and S. Gallacher. 2001. Characterisation of bacterial communities associated with toxic and non-toxic dinoflagellates: Alexandrium spp. and Scrippsiella trochoidea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:161-173. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmes, A. J., D. P. Kelly, S. C. Baker, A. S. Thompson, P. DeMarco, E. M. Kenna, and J. C. Murrell. 1997. Methylosulfonomonas methylovora gen. nov., sp. nov., and Marinosulfonomonas methylotropha gen. nov., sp. nov.: novel methylotrophs able to grow on methanesulfonic acid. Arch. Microbiol. 167:46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inagaki, F., M. Suzuki, K. Takai, H. Oida, T. Sakamoto, K. Aoki, K. H. Nealson, and K. Horikoshi. 2003. Microbial communities associated with geological horizons in coastal subseafloor sediments from the Sea of Okhotsk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7224-7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ivanova, E. P., N. M. Gorshkova, T. Sawabe, N. V. Zhukova, K. Hayashi, V. V. Kurilenko, Y. Alexeeva, V. Buljan, D. V. Nicolau, V. V. Mikhailov, and R. Christen. 2004. Sulfitobacter delicatus sp. nov. and Sulfitobacter dubius sp. nov., respectively from a starfish (Stellaster equestris) and sea grass (Zostera marina). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:475-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jonkers, H. M., and R. M. M. Abed. 2003. Identification of aerobic heterotrophic bacteria from the photic zone of a hypersaline microbial mat. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 30:127-133. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Junge, K., F. Imhoff, T. Staley, and J. W. Deming. 2002. Phylogenetic diversity of numerically important Arctic sea-ice bacteria cultured at subzero temperature. Microb. Ecol. 43:315-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly, K. M., and A. Y. Chistoserdov. 2001. Phylogenetic analysis of the succession of bacterial communities in the Great South Bay (Long Island). FEMS Microb. Ecol. 35:85-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiene, R. P., and L. J. Linn. 2000. Distribution and turnover of dissolved DMSP and its relationship with bacterial production and dimethylsulfide in the Gulf of Mexico. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45:849-861. [Google Scholar]

- 58.King, G. M. 2003. Molecular and culture-based analyses of aerobic carbon monoxide oxidizer diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7257-7265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kolber, M. K., C. L. Van Dover, R. A. Niederman, and P. G. Falkowski. 2000. Bacterial photosynthesis in surface waters of the open ocean. Nature 407:177-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Labrenz, M., M. D. Collins, P. A. Lawson, B. J. Tindall, G. Braker, and P. Hirsch. 1998. Antarctobacter heliothermus gen. nov., sp. nov., a budding bacterium from hypersaline and heliothermal Ekho Lake. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:1363-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lafay, B., R. Ruimy, C. R. Detraubenberg, V. Breittmayer, M. J. Gauthier, and R. Christen. 1995. Roseobacter algicola sp. nov., a new marine bacterium isolated from the phycosphere of the toxin-producing dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:290-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lau, S. C. K., M. M. Y. Tsoi, X. Li, I. Plakhotnikova, M. Wu, P.-K. Wong, and P.-Y. Qian. 2004. Loktanella hongkongensis sp. nov., a novel member of the α-Proteobacteria originating from marine biofilms in Hong Kong waters. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:2281-2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li, L., J. Guenzennec, P. Nichols, P. Henry, M. Yanagibayashi, and C. Kato. 1999. Microbial diversity in Nankai Trough sediments at a depth of 3,843 m. J. Oceanogr. 55:635-642. [Google Scholar]

- 64.López-Garcia, P., S. Duperron, P. Philippot, J. Foriel, J. Susini, and D. Moreira. 2003. Bacterial diversity in hydrothermal sediment and epsilon proteobacterial dominance in experimental microcolonizers at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Environ. Microbiol. 5:961-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.López-Garcia, P., A. López-López, D. Moreira, and F. Rodríguez-Valera. 2001. Diversity of free-living prokaryotes from a deep-sea site at the Antarctic Polar Front. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 36:193-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Madrid, V. M., J. Y. Aller, R. C. Aller, and A. Y. Chistoserdov. 2001. High prokaryote diversity and analysis of community structure in mobile mud deposits off French Guiana: identification of two new bacterial candidate divisions. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:197-209. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Malmstrom, R. R., R. P. Kiene, and D. L. Kirchman. 2004. Identification and enumeration of bacteria assimilating dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) in the North Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49:597-606. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martínez-Cánovas, M. J., E. Quesada, F. Martínez-Checa, A. del Moral, and V. Béjar. 2004. Salipiger mucescens gen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately halophilic, exopolysaccharide-producing bacterium isolated from hypersaline soil, belonging to the α-Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1735-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller, T. R., and R. Belas. 2004. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate metabolism by Pfiesteria-associated Roseobacter spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70: 3383-3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mills, H. J., C. Hodges, K. Wilson, I. R. MacDonald, and P. A. Sobecky. 2003. Microbial diversity in sediments associated with surface-breaching gas hydrate mounds in the Gulf of Mexico. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 46:39-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mitova, M., G. Tommonaro, U. Hentschel, W. E. G. Muller, and S. De Rosa. 2004. Exocellular cyclic cipeptides from a Ruegeria strain associated with cell cultures of Suberites domuncula. Mar. Biotech. 6:95-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moore, L. R., G. Rocap, and S. W. Chisholm. 1998. Physiology and molecular phylogeny of coexisting Prochlorococcus ecotypes. Nature 393:464-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moran, M. A., A. Buchan, J. M. González, J. F. Heidelberg, W. B. Whitman, R. P. Kiene, J. R. Henriksen, G. M. King, R. Belas, C. Fuqua, L. Brinkac, M. Lewis, S. Johri, B. Weaver, G. Pai, J. A. Eisen, E. Rahe, W. M. Sheldon, W. Ye, T. R. Miller, J. Carlton, D. A. Rasko, I. T. Paulsen, Q. Ren, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, S. A. Sullivan, M. J. Rosovitz, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, and N. Ward. 2004. Genome sequence of Silicibacter pomeroyi reveals adaptations to the marine environment. Nature 432:910-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moran, M. A., J. M. González, and R. P. Kiene. 2003. Linking a bacterial taxon to sulfur cycling in the sea: studies of the marine Roseobacter group. Geomicrobiol. J. 20:375-388. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moran, M. A., and R. E. Hodson. 1994. Dissolved humic substances of vascular plant-origin in a coastal marine-environment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39:762-771. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moune, S., P. Caumette, R. Matheron, and J. C. Willison. 2003. Molecular sequence analysis of prokaryotic diversity in the anoxic sediments underlying cyanobacterial mats of two hypersaline ponds in Mediterranean salterns. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 44:117-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mullins, T. D., T. B. Britschgi, R. L. Krest, and S. J. Giovannoni. 1995. Genetic comparisons reveal the same unknown bacterial lineages in Atlantic and Pacific bacterioplankton communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40:148-158. [Google Scholar]

- 78.O'Sullivan, L. A., K. E. Fuller, E. M. Thomas, C. M. Turley, J. C. Fry, and A. J. Weightman. 2004. Distribution and culturability of the uncultivated ‘AGG58 cluster’ of the Bacteroidetes phylum in aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47:359-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oz, A., G. Sabehi, M. Koblizek, R. Massana, and O. Béjà. 2005. Roseobacter-like bacteria in Red and Mediterranean Sea aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:344-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pantos, O., R. P. Cooney, M. D. A. Le Tissier, M. R. Barer, A. G. O'Donnell, and J. C. Bythell. 2003. The bacterial ecology of a plague-like disease affecting the Caribbean coral Montastrea annularis. Environ. Microbiol. 5:370-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patel, P., M. E. Callow, I. Joint, and J. A. Callow. 2003. Specificity in the settlement-modifying response of bacterial biofilms towards zoospores of the marine alga Enteromorpha. Environ. Microbiol. 5:338-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pernthaler, A., J. Pernthaler, M. Schattenhofer, and R. Amann. 2002. Identification of DNA-synthesizing bacterial cells in coastal North Sea plankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5728-5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pinhassi, J., U. Zweifel, and A. Hagström. 1997. Dominant marine bacterioplankton species found among colony-forming bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3359-3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Powell, S. M., J. P. Bowman, I. Snape, and J. S. Stark. 2003. Microbial community variation in pristine and polluted nearshore Antarctic sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45:135-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pradella, S., M. Allgaier, C. Hoch, O. Päuker, E. Stackebrandt, and I. Wagner-Döbler. 2004. Genome organization and localization of the pufLM genes of the photosynthesis reaction center in phylogenetically diverse marine alphaproteobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3360-3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pukall, R., D. Buntefuss, A. Frühling, M. Rohde, R. Kroppenstedt, J. Burghardt, P. Lebaron, L. Bernard, and E. Stackebrandt. 1999. Sulfitobacter mediterraneus sp. nov., a new sulfite-oxidizing member of the α-Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:513-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pukall, R., I. Kramer, M. Rohde, and E. Stackebrandt. 2002. Microbial diversity of cultivatable bacteria associated with the North Sea bryozoan Flustra foliacea. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 24:623-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rappé, M. S., P. F. Kemp, and S. J. Giovannoni. 1997. Phylogenetic diversity of marine coastal picoplankton 16S rRNA genes cloned from the continental shelf off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42:811-826. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rappé, M. S., K. Vergin, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2000. Phylogenetic comparisons of a coastal bacterioplankton community with its counterparts in open ocean and freshwater systems. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 33:219-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Riemann, L., G. F. Steward, and F. Azam. 2000. Dynamics of bacterial community composition and activity during a mesocosm diatom bloom. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:578-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rocap, G., F. W. Larimer, J. Lamerdin, S. Malfatti, P. Chain, N. A. Ahlgren, A. Arellano, M. Coleman, L. Hauser, W. R. Hess, Z. I. Johnson, M. Land, D. Lindell, A. F. Post, W. Regala, M. Shah, S. L. Shaw, C. Steglich, M. B. Sullivan, C. S. Ting, A. Tolonen, E. A. Webb, E. R. Zinser, and S. W. Chisholm. 2003. Genome divergence in two Prochlorococcus ecotypes reflects oceanic niche differentiation. Nature 424:1042-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ruiz-Ponte, C., V. Cilia, C. Lambert, and J. L. Nicolas. 1998. Roseobacter gallaeciensis sp. nov., a new marine bacterium isolated from rearings and collectors of the scallop Pecten maximus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:537-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sandaa, R.-A., T. Magnesen, L. Torkildsen, and Ø. Bergh. 2003. Characterisation of the bacterial community associated with early stages of great scallop (Pecten maximus), using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 26:302-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schaefer, J. K., K. D. Goodwin, I. R. McDonald, J. C. Murrell, and R. S. Oremland. 2002. Leisingera methylohatidivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., a marine methylotroph that grows on methyl bromide. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:851-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schäfer, H., B. Abbas, H. Witte, and G. Muyzer. 2002. Genetic diversity of ‘satellite’ bacteria present in cultures of marine diatoms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schmidt, T. M., E. F. Delong, and N. R. Pace. 1991. Analysis of a marine picoplankton community by 16S ribosomal RNA gene cloning and sequencing. J. Bacteriol. 173:4371-4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sekiguchi, H., H. Koshikawa, M. Hiroki, S. Murakami, K. Xu, M. Watanabe, M. Nakahara, M. Zhu, and H. Uchiyama. 2002. Bacterial distribution and phylogenetic diversity in the Changjiang Estuary before the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. Microb. Ecol. 43:82-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Selje, N., M. Simon, and T. Brinkhoff. 2004. A newly discovered Roseobacter cluster in temperate and polar oceans. Nature 427:445-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shiba, T. 1991. Roseobacter litoralis gen. nov., sp. nov., and Roseobacter denitrificans sp. nov., aerobic pink-pigmented bacteria which contain bacteriochlorophyll-a. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 14:140-145. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shiba, T. 1984. Utilization of light energy by the strictly aerobic bacterium Erythrobacter sp. OCh 114. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 30:239-244. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shiba, T., U. Shimidu, and N. Taga. 1979. Distribution of aerobic bacteria which contain bacteriochlorophyll-a. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 14:140-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Simu, K., and A. Hagström. 2004. Oligotrophic bacterioplankton with a novel single-cell life strategy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2445-2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smith, T. F., and M. S. Waterman. 1981. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 147:195-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sorokin, D. Y. 1994. Influence of thiosulfate on the growth of sulfate-producing sulfur-oxidizing heterotrophic bacteria from the Black Sea in continuous culture. Microbiology 63:255-259. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sorokin, D. Y. 1995. Sulfitobacter pontiacus gen. nov., sp. nov—a new heterotrophic bacterium from the Black Sea, specialized on sulfite oxidation. Microbiology 64:295-305. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sorokin, D. Y., and A. M. Lysenko. 1993. Heterotrophic bacteria from the Black Sea oxidizing reduced sulfur compounds to sulfate. Microbiology 62:594-602. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Suzuki, M., C. Preston, O. Béjà, J. de la Torre, G. Steward, and E. Delong. 2004. Phylogenetic screening of ribosomal RNA gene-containing clones in bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) libraries from different depths in Monterey Bay. Microb. Ecol. 48:473-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Suzuki, M., M. Rappé, Z. Haimberger, H. Winfield, N. Adair, J. Ströbel, and S. Giovannoni. 1997. Bacterial diversity among small-subunit rRNA gene clones and cellular isolates from the same seawater sample. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:983-989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Suzuki, M. T., C. M. Preston, F. P. Chavez, and E. F. DeLong. 2001. Quantitative mapping of bacterioplankton populations in seawater: field tests across an upwelling plume in Monterey Bay. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 24:117-127. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tanner, M. A., C. L. Everett, W. J. Coleman, M. M. Yang, and D. C. Youvan. 2000. Complex microbial communities inhabiting sulfide-rich black mud from marine coastal environments. Biotechnology et alia 8:1-16. [Online.] http://www.et-al.com. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Taylor, M. W., P. J. Schupp, I. Dahllöf, S. Kjelleberg, and P. D. Steinberg. 2004. Host specificity in marine sponge-associated bacteria, and potential implications for marine microbial diversity. Environ. Microbiol. 6:121-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tolli, J. 2003. Identity and dynamics of the microbial community responsible for carbon monoxide oxidation in marine environments. Ph.D. thesis. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution/Massachusetts Institute of Technology Joint Program, Woods Hole, Mass.

- 113.Urbance, J. W., B. J. Bratina, S. F. Stoddard, and T. M. Schmidt. 2001. Taxonomic characterization of Ketogulonigenium vulgare gen. nov., sp. nov. and Ketogulonigenium robustum sp. nov., which oxidize l-sorbose to 2-keto-l-gulonic acid. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1059-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.van Trappen, S., J. Mergaert, and J. Swings. 2004. Loktanella salsilacus gen. nov., sp. nov., Loktanella fryxellensis sp. nov. and Loktanella vestfoldensis sp. nov., new members of the Rhodobacter group, isolated from microbial mats in Antarctic lakes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1263-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Venter, J. C., K. Remington, J. F. Heidelberg, A. L. Halpern, D. Rusch, J. A. Eisen, D. Y. Wu, I. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, W. Nelson, D. E. Fouts, S. Levy, A. H. Knap, M. W. Lomas, K. Nealson, O. White, J. Peterson, J. Hoffman, R. Parsons, H. Baden-Tillson, C. Pfannkoch, Y. H. Rogers, and H. O. Smith. 2004. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 304:66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vetriani, C., H. V. Tran, and L. J. Kerkhof. 2003. Fingerprinting microbial assemblages from the oxic/anoxic chemocline of the Black Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6481-6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Vila, M., R. Simó, R. P. Kiene, J. Pinhassi, J. M. González, M. A. Moran, and C. Pedrós-Alió. 2004. Use of microautoradiography combined with fluorescence in situ hybridization to determine dimethylsulfoniopropionate incorporation by marine bacterioplankton taxa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4648-4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wagner-Döbler, I., H. Rheims, A. Felske, A. El-Ghezal, D. Flade-Schröder, H. Laatsch, S. Lang, R. Pukall, and B. J. Tindall. 2004. Oceanibulbus indolifex gen. nov., sp. nov., a North Sea α-proteobacterium that produces bioactive metabolites. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1177-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Webster, N. S., A. P. Negri, M. M. H. G. Munro, and C. N. Battershill. 2004. Diverse microbial communities inhabit Antarctic sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 6:288-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Weidner, S., W. Arnold, E. Stackebrandt, and A. Pühler. 2000. Phylogenetic analysis of bacterial communities associated with leaves of the seagrass Halophila stipulacea by a culture-independent small-subunit rRNA gene approach. Microb. Ecol. 39:22-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yakimov, M. M., L. Giuliano, E. Crisafi, T. N. Chernikova, K. N. Timmis, and P. N. Golyshin. 2002. Microbial community of a saline mud volcano at San Biagio-Belpasso, Mt. Etna (Italy). Environ. Microbiol. 4:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yoch, D. C. 2002. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate: its sources, role in the marine food web, and biological degradation to dimethylsulfide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5804-5815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zafiriou, O. C., S. S. Andrews, and W. Wang. 2003. Concordant estimates of oceanic carbon monoxide source and sink processes in the Pacific yield a balanced global “blue-water” CO budget. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycl. 17:1015-1029. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zhou, N.-Y., S. L. Fuenmayor, and P. A. Williams. 2001. nag genes of Ralstonia (formerly Pseudomonas) sp. strain U2 encoding enzymes for gentisate catabolism. J. Bacteriol. 183:700-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zubkov, M. V., B. M. Fuchs, S. D. Archer, R. P. Kiene, R. Amann, and P. H. Burkill. 2002. Rapid turnover of dissolved DMS and DMSP by defined bacterioplankton communities in the stratified euphotic zone of the North Sea. Deep-Sea Res. II 49:3017-3038. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.