Abstract

Xenorhabdus nematophila is a mutualist of entomopathogenic nematodes and a pathogen of insects. To begin to examine the role of pyrimidine salvage in nutrient exchange between X. nematophila and its hosts, we identified and mutated an X. nematophila tdk homologue. X. nematophila tdk mutant strains had reduced virulence toward Manduca sexta insects and a competitive defect for nematode colonization in plate-based assays. Provision of a wild-type tdk allele in trans corrected the defects of the mutant strain. As in Escherichia coli, X. nematophila tdk encodes a deoxythymidine kinase, which converts salvaged deoxythymidine and deoxyuridine nucleosides to their respective nucleotide forms. Thus, nucleoside salvage may confer a competitive advantage to X. nematophila in the nematode intestine and be important for normal entomopathogenicity.

The bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila has not been isolated as a free-living organism but is found associated with the nematode Steinernema carpocapsae and larval insects (8). X. nematophila has a mutualistic interaction with the nematode; between 30 and 200 X. nematophila cells reside extracellularly in an intestinal structure (vesicle) of a nonfeeding form of the nematode, termed the infective juvenile (IJ). This colonization state is initiated by one or two X. nematophila cells that multiply within the vesicle of a newly formed IJ to reach colony sizes typical of a mature IJ (16). The IJ nematode serves as a vector for X. nematophila to reach the hemocoel of its other host: larval insects, particularly of the order Lepidoptera. The bacterium remains extracellular during infection (30) and produces toxins that are lethal to the insect. X. nematophila and the nematode digest the insect and reproduce through multiple generations within the insect carcass. When nutrients are depleted in the insect, nematode progeny develop into the IJ stage and migrate away in search of a new host, taking along a vesicular clutch of X. nematophila bacteria (8).

In both the nematode and insect hosts, X. nematophila grows and divides (16, 34). However, we are only beginning to understand what specific nutrients X. nematophila uses for growth in the two host environments. While some components of insect hemolymph are known (e.g., proteins, inorganic ions, amino acids, and sugars [28]), the availability of these compounds as a source of nutrients to X. nematophila in the insect has not been determined. X. nematophila threonine, pyridoxine (vitamin B6), and p-aminobenzoate (PABA) auxotrophs are defective for IJ nematode colonization (17a). This suggests that the nematode vesicle is lacking these compounds or one or more of the products whose synthesis depends on these compounds.

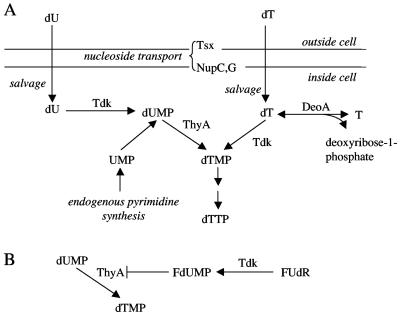

Pyrimidine and purine nucleotides are essential to living organisms for the synthesis of DNA and, in bacteria, can be combined with a sugar (e.g., deoxythymidine diphosphate-l-rhamnose) to participate in the synthesis of polysaccharide components of cell walls and capsules (11). Endogenous synthesis of deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP, a pyrimidine nucleotide) and purine nucleotides is dependent on PABA (18). In Escherichia coli, the pyrimidine nucleotide dTMP can additionally be synthesized from deoxythymidine (dT) nucleoside by the enzyme deoxythymidine kinase (Tdk) (Fig. 1A). dT is in turn salvaged from the environment using nucleoside uptake proteins or manufactured in the cell from imported thymine nucleobase and endogenous deoxyribose- 1-phosphate sugar by the enzyme deoxythymidine phosphorylase (DeoA), provided that there is a sufficient supply of the sugar. Tdk can also convert salvaged deoxyuridine (dU) nucleoside to deoxyuridine monophosphate, an intermediate of endogenous dTMP synthesis. Thus, Tdk has the potential to contribute to dTMP synthesis in two possible ways. However, little is known regarding how cells balance endogenous and salvage synthesis mechanisms (for a review of nucleotide synthesis, see reference 24).

FIG. 1.

dTMP synthesis (A) and mode of FdUMP toxicity (B) in E. coli. ThyA is thymidylate synthase, DeoA is deoxythymidine phosphorylase, T is thymine, dTTP is deoxythymidine triphosphate, dUMP is deoxyuridine monophosphate, and UMP is uridine monophosphate. NupC and NupG are nucleoside transporters in the inner membrane, and Tsx is a porin in the outer membrane.

Salvaged nucleosides can be used by bacteria as a carbon, energy, and nitrogen source (14) or can be used to supplement endogenous nucleotide pools for DNA and polysaccharide synthesis. In addition to their structural and nutritional use by organisms, nucleosides may also serve as environmental indicators sensed by signal transduction cascades. For example, planktonic Vibrio cholerae cells respond to the presence of nucleosides in their environment by joining a biofilm (12).

An uncorroborated study suggested the involvement of thymidine salvage in the host interactions of X. nematophila (see Results). Thus, we hypothesized that the ability to salvage dT or dU nucleosides could be important in the host interactions of X. nematophila. To test this possibility, we sought to define X. nematophila dT/dU salvage pathways and to construct and assay mutants defective in these pathways for their ability to maintain normal host interactions. Here, we report the identification of an X. nematophila tdk homologue, confirmation of the predicted activity of its product, and creation of an X. nematophila tdk mutant strain. Results of host interaction assays with the X. nematophila tdk mutant indicate that dT or dU salvage can be a beneficial bacterial function in both the nematode and insect host environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and standard growth conditions.

Table 1 shows a list of bacterial strains used in this study. Cultures were grown in a tube roller at 30°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (20) that had been stored in the dark (38), unless indicated otherwise. Agar (20 g liter−1) plates were supplemented with 1 g liter−1 sodium pyruvate (38), and all media were supplemented when appropriate with kanamycin (Kan; 20 mg liter−1), erythromycin (Ery; 150 mg liter−1) and chloramphenicol (Cam; 20 mg liter−1). Solid lipid agar (LA) medium was prepared as described elsewhere (34). 5-Fluorodeoxyuridine-containing semidefined medium (FUdR medium) was prepared as described elsewhere (33), except that 1 g liter−1 sodium pyruvate was added for the solid medium used with X. nematophila. Permanent stocks of cultures were stored at −80°C in LB broth supplemented with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Source of strain |

|---|---|---|

| X. nematophila | ||

| HGB007 | ATCC 19061, wild type, 1996 | American Type Culture Collection |

| HGB800 | ATCC 19061, wild type, 2003 | American Type Culture Collection |

| HGB820 | HGB800 tdk-1::Tn5 (Camr), isolate a | This study |

| HGB863 | HGB800 tdk-1::Tn5 (Camr), isolate b | This study |

| HGB864 | HGB800 tdk-1::Tn5 (Camr), isolate c | This study |

| HGB865 | HGB800 att::Tn7 (Eryr) | This study |

| HGB866 | HGB864 att::Tn7-tdk (Eryr) | This study |

| HGB867 | HGB820 att::Tn7-tdk (Eryr) | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| S17-1 λ pir | General cloning and conjugation donor strain | 31 |

| KY895 | λ−tdk-1 IN(rrnD-rrnE)1, ilv-276; tdk mutant strain | 13; E. coli Genetic Stock Center |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Novagen (Madison, WI) |

DNA manipulations, conjugations, and pR6Kan plasmid construction.

DNA manipulations and transformation of E. coli were performed using standard protocols (2; product literature). E. coli S17-1 λpir was used as the donor strain to conjugate plasmids into X. nematophila as described previously (9, 27). Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) or Sigma Genosys (The Woodlands, Texas) synthesized the oligonucleotides used in this study (Table 2). All compared sequences were obtained from the GenBank database (1) through the National Center for Biotechnology Information. To construct pR6Kan, the Kanr cassette from Tn903 (25) was PCR amplified with primers PstIkan1 and PstIkan2 (Table 2) and the amplified product cloned into plasmid pGP704 (21) using the engineered PstI restriction sites to create plasmid pR6Kan, with the removal of the first 478 bp of bla and the recreation of a BglII restriction site (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Target |

|---|---|---|

| BamHItdk | GGATCCCTTAGTGATTTTATACG | 3′ of tdk |

| KpnItdk | NNNNNNGGTACCTGAAGGTGCAAAAAACCCAG | 5′ of tdk |

| NcoItdkshort | CCATGGCTCAGCTTTATTTTTAT | tdk |

| PstIkan1b | GCTGCAGAGATCTCGTTGTGTCTCAAAATCTCT | Tn903 |

| PstIkan2 | GGCTGCAGTTAGAAAAACTCATCGAGCATC | Tn903 |

| SacItdk | NNNNNNGAGCTCCGCTTTACCGCTTAAAGCG | 3′ of tdk |

| SpeIugdxn5 | ACTAGTGGGCAGCACGTTTAGATTTAC | 5′ of tdk |

Underlined nucleotides indicate engineered restriction sites (also underlined in oligonucleotide name) used in cloning.

The BamHI restriction site of PstIkan1 is shown in boldface.

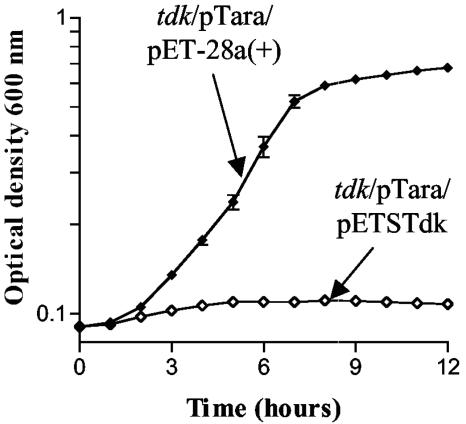

Complementation of the growth defect of an E. coli tdk mutant with X. nematophila tdk.

The X. nematophila tdk gene with 41 bp of 3′-flanking sequence was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA using primers NcoItdkshort and BamHItdk (Table 2). The amplified product was cloned into pET-28a(+) (Novagen, Madison, WI) using the engineered NcoI and BamHI restriction sites. The resulting plasmid, pETSTdk, was transformed along with pTara (a plasmid encoding an arabinose-inducible copy of T7 RNA polymerase [37]) into KY895. In addition, pET-28a(+) was transformed into KY895 with pTara to create a vector-only control strain. The resulting strains were grown overnight from isolated colonies, washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and subcultured 1:100 into FUdR/Kan/Cam medium (neither arabinose nor isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG] were required to achieve expression of tdk) (see Results). Samples (100-μl total volume) were placed in non-tissue-culture-treated, 96-well, flat-bottom polystyrene plates (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and incubated at 37°C with shaking in a Molecular Devices SPECTRAmax 190 plate reader. Absorbance data were collected using SOFTMax PRO 3.1.2 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Construction and complementation of X. nematophila tdk mutants.

To construct an X. nematophila tdk mutant strain, a 2.2-kb fragment of the X. nematophila genome was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA using primers SacItdk and KpnItdk (Table 2). The resulting product was cloned into pR6Kan using the engineered SacI and KpnI restriction sites to create plasmid pR6tdk. The GeneJumper primer insertion kit for sequencing (Camr; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to insert transposons into pR6tdk, and the pool of mutagenized plasmids was transformed into E. coli S17-1 λpir. Strains containing transposed pR6tdk were selected on the basis of Kanr and Camr. Plasmid pR6tdk::Tn5, chosen for a transposon location suitable for creating a tdk mutant strain, was conjugated into X. nematophila HGB800, and three strains that had undergone a double recombination event to incorporate the transposon-disrupted locus into the chromosome with concurrent loss of the plasmid (Camr Kans) were chosen for further study: X. nematophila tdk-1::Tn5 HGB820, HGB863, and HGB864. Three independent colonies were chosen for further study to minimize the chance of selecting a strain with a spontaneous reduced-virulence phenotype. The insertion in HGB820, HGB863, and HGB864 disrupts tdk at the predicted encoded amino acid 135 of 198. To complement the tdk mutation, a 2.2-kb fragment of the X. nematophila genome was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA using primers SpeIugdxn5 and KpnItdk (Table 2). The resulting product was cloned into pEVS107 (Eryr Kanr Tn7 donor oriR6K suicide plasmid [19]) using the engineered SpeI and KpnI restriction sites to create plasmid pTn7tdk. pTn7tdk was conjugated into X. nematophila tdk-1::Tn5 HGB820 and HGB864 (HGB863 was not tested for complementation) in a triparental mating with E. coli S17-1λ pir harboring plasmid pUX-BF13 (3), which encodes a transposase for transposition of Tn7 into the bacterial att site. Kans exconjugants HGB866 and HGB867 (from the transposition of HGB864 and -820, respectively) carrying the Tn7-tdk construct were FUdRs, indicating that they expressed an active Tdk protein (see Results for an explanation of FUdR assays). pEVS107 (vector only) was similarly conjugated into HGB800 (wild type) to create the control strain HGB865 (Table 1).

Nematode growth and noncompetitive cocultivations with bacteria.

Steinernema carpocapsae All (Weiser) was propagated by passage through Galleria mellonella larvae (Vanderhorst Wholesale, Inc., St. Marys, Ohio), harvested in White traps (36), and stored in water. In vitro culture of nematodes on bacterial lawns for colonization assays was performed on LA plates as described previously (34). Axenic nematode eggs were isolated from gravid adult females as described previously (35). Eggs were washed and resuspended in LB broth and incubated at room temperature for 1 to 2 days to assess sterility and to enable hatching into larval stage nematodes, which were used to inoculate coculture plates. IJ nematodes were harvested, surface sterilized, and sonicated as described previously (27). The sonicated nematode suspensions were serially diluted and plated on LB plates to determine average numbers of CFU per IJ.

Competitive bacterial colonization assays.

Competitiveness of mutant (and complemented mutant) strains for nematode colonization was measured in two assays, LA plate coculture and insect infection, both as described previously (27), except that the proportion of the mutant isolates in the bacterial lawn was calculated on both day 1 and day 9 and 500 IJ nematodes were used for all the insect infections. For the LA coculture assays, the proportion of colonization by the X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates in the output (IJ nematodes) was compared to the proportion of the mutant isolates in the input (lawn; either day 1 or day 9) to calculate a proportionplate output/proportionplate input index. For the insect-based infection assay, the proportionplate output for the LA colonization assay was used as the proportioninsect input. The proportioninsect output/proportioninsect input index was calculated to determine how well the mutant isolates competed with the wild-type strain for colonization of the nematode during insect infection. An index of 1 in either assay would indicate that the mutant isolates competed equally well as the wild-type strain for nematode colonization under the tested conditions, and an index of less than 1 would indicate that the mutant had a defect in competitive colonization. For the competitive colonization assays on plates in the presence of nematodes, 13 independent experiments were conducted for the mutant isolates, and 10 were conducted for the complemented mutant isolates. For the competitive colonization assays in insects, 10 independent experiments each were conducted for the mutant isolates and the complemented mutant isolates. Competitive indices were calculated for each experiment, and the values were averaged and used to calculate the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Manduca sexta insect rearing and injection assays.

M. sexta (tobacco hornworm) insect eggs were obtained from the North Carolina State University (NCSU) Entomology Insectary, and larvae were reared as described previously (34). Between 14,000 and 69,000 CFU in 10 μl phosphate-buffered saline were injected into fourth-instar M. sexta as previously described (27). CFU for each treatment was similar within each experiment but varied across experiments. The insects were fed and monitored until 96 h postinjection, and deaths in each set of 10 insects were recorded to provide percent mortality.

Statistical analysis.

A one-sample t test was used to analyze the nematode colonization data, and a one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett's posttest was used to analyze the pathogenesis data. The mutant isolate data were compared to the wild-type strain data for the noncompetitive nematode colonizationand pathogenesis assays or to a value of 1 for the competitive nematode colonization assays at the 95% confidence interval (Prism version 3.0a for Macintosh; GraphPad Software, San Diego, California).

RESULTS

X. nematophila tdk encodes a functional nucleoside kinase in vivo.

An X. nematophila strain was isolated with a transposon 6 bp 5′ of a putative tdk gene (GenBank accession no. AY363171 [27]), which is predicted to encode a protein with 70% identity to E. coli deoxythymidine kinase. This mutant was initially identified as having reduced levels of nematode colonization (data not shown), but the observed colonization defect of the tdk insertion mutant strain was not reproducibly obtained. However, we hypothesized that the ability to utilize host-derived pyrimidines might confer an advantage to X. nematophila within the nematode intestine or the insect hemolymph. To test this hypothesis, we first determined whether X. nematophila tdk encodes a functional nucleoside kinase. The X. nematophila tdk gene was tested for its ability to complement the resistance of an E. coli tdk mutant, KY895, to a nucleoside analogue, FUdR. Tdk from E. coli can phosphorylate FUdR to form 5′-fluorodeoxyuridine monophosphate (FdUMP). FdUMP blocks the endogenous dTMP pathway by inhibiting ThyA (Fig. 1B). Thus, in the absence of exogenous dT or thymine, FUdR is toxic to cells with a functional Tdk; strains lacking deoxythymidine kinase activity (e.g., KY895) can grow in this condition (33). KY895 carrying plasmids pTara and pET-28a(+) or pETSTdk was assayed for growth in FUdR medium. As expected, the pET-28a(+)-containing vector-only control strain was able to grow in the FUdR medium, indicating the lack of a functional Tdk. However, KY895 carrying the pETSTdk plasmid failed to grow in the FUdR medium, demonstrating that the X. nematophila tdk gene encoded a protein that conferred sensitivity to FUdR (i.e., it complemented the FUdR resistance phenotype of the E. coli tdk mutant strain) (Fig. 2). Thus, X. nematophila tdk likely encodes a functional deoxythymidine kinase in vivo. In vitro assays on purified Tdk protein support this conclusion (26).

FIG. 2.

Complementation of an E. coli tdk mutant with X. nematophila tdk. E. coli KY895 (tdk mutant) carrying plasmids pTara (supplies T7 RNA polymerase) and either pET-28a(+) [vector only; closed diamonds; tdk/pTara/pET-28a(+)] or pETSTdk (expresses X. nematophila tdk; open diamonds; tdk/pTara/pETSTdk) was grown in FUdR/Kan/Cam medium. Error bars representing standard error are present, but not necessarily visible, at all data points.

X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates colonize S. carpocapsae nematodes.

To determine whether X. nematophila relies on dT or thymine salvaging in the nematode host environment, we constructed defined X. nematophila tdk mutant (tdk-1) strains (HGB820, HGB863, and HGB864) and assayed these strains for their ability to colonize S. carpocapsae nematodes during growth on LA plates. Following a 2-week cocultivation, the mutant isolates colonized the nematode to a level similar to that of the wild-type strain (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Host interactions of X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates

| Strain | No. of CFU per IJ (± SEM)c | Colonization competitive index (± SEM)e

|

% Mortality (± SEM)g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-based input on:

|

Insect-based input | ||||

| Day 1 | Day 9 | ||||

| Wild type (HGB800) | 46.6 (± 7.3) | NAf | NA | NA | 70.0 (± 9.1) |

| tdk-1::Tn5a | 51.2 (± 4.2) | 0.46 (± 0.06)* | 0.65 (± 0.08)** | 0.95 (± 0.18) | 35.3 (± 5.4)**** |

| tdk-1::Tn5 att::Tn7-tdkb | NDd | 1.22 (± 0.26) | 0.98 (± 0.16) | 1.39 (± 0.15)*** | 65.0 (± 7.6) |

Average of HGB820, HGB863, and HGB864 results; competitive index versus HGB800.

Average of HGB866 and HGB867 results; competitive index versus HGB865 (HGB800 att::Tn7).

Average colonization level of S. carpocapsae nematodes.

ND, not determined.

Proportionoutput/proportioninput for competitive nematode colonization assays. Asterisks indicate significant difference from 1 (*, P < 0.0001; **, P = 0.0008; ***, P < 0.05).

NA, not applicable.

Average percent mortality of a group of 10 M. sexta larval insects at 96 h following injection of 14,000 to 69,000 CFU (similar CFU for each strain/isolate were injected in each experiment, but levels differed between experiments). Asterisks (****) indicate significant difference from HGB800 mortality (P < 0.01).

The X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates are less competitive than the wild-type strain for nematode colonization on LA plates.

We assayed the ability of three separate isolates of the X. nematophila tdk-1 mutant (strains HGB820, HGB863, and HGB864) to colonize the nematode host when in competition with the wild-type strain to determine if the presence of an intact tdk locus can confer a competitive advantage in this process (Table 3). Two types of assays, plate and insect based, were used to test the ability of the tdk mutant isolates to colonize the nematode in competition with the wild-type strain. These two assays measure competition under distinct nutrient conditions: the plate-based assays tested competitive growth of the tdk mutant isolates on LA medium, while the insect-based assays tested competitive growth of the tdk mutant isolates in the insect, an environment containing nutrient resources naturally available to X. nematophila. When mixed with wild-type X. nematophila bacteria in the plate-based colonization assay, the X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates demonstrated a competitive defect for nematode colonization: the calculated competitive index was 0.46 (SEM = 0.06) when the proportion colonization of the IJ nematode was compared to the proportion of the mutant isolates on the plate at day 1 and 0.65 (SEM = 0.08) when compared to the proportion of the mutant on the plate at day 9 of the assay. These values are significantly different from 1 (P of <0.0001 and P of 0.0008, respectively), the index that would indicate the mutant isolates compete as well as the wild-type strain. The complemented isolates had competitive indices of 1.22 (SEM = 0.26) and 0.98 (SEM = 0.16) for the day 1 and day 9 comparisons, respectively. These values are not significantly different from 1 (P of 0.43 and 0.9, respectively) and indicate that the observed defect of the X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates was due to the transposon inserted in the tdk locus.

Competitive colonization assays in G. mellonella insects revealed a competitive index of 0.86 (SEM = 0.17) for the mutant isolates and 1.39 (SEM = 0.14) for the complemented mutant isolates. The competitive index for the mutant isolates is not significantly different from 1 (P = 0.43), indicating that the mutant isolates did not have a competitive defect for nematode colonization during development in the G. mellonella insect environment. However, the competitive index for the complemented mutant isolates is significantly greater than 1 (P = 0.023), indicating that the complemented mutant isolates had a competitive advantage compared to the wild-type strain for nematode colonization under these conditions.

X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates are less virulent than the wild-type strain toward M. sexta insects.

The X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates killed fewer insects (Table 3) and on average took approximately three times longer to effect the death of insects (time to lethality for 30% of insects [LT30] ≈ 72 h) than the wild-type strain (LT30 ≈ 20 h) when injected directly into M. sexta insect larvae. The complemented strain showed normal (wild-type) virulence as measured both by the number of insects killed (Table 3) and the length of time the insects survived (LT30 ≈ 20 h).

DISCUSSION

While genes important in mutualism with nematodes (reviewed in reference 17) and pathogenicity toward insects (5, 10) have been identified in X. nematophila, it remains obscure what nutrients X. nematophila requires or utilizes in the nematode and insect host environments. In this study, we have provided evidence that X. nematophila dT and/or dU salvage is important in the nematode and insect host environments: X. nematophila tdk-1 mutant isolates showed a defect for nematode colonization when placed in competition with the wild-type strain in a plate-based assay and exhibited a defect in M. sexta insect killing. Each of these host interaction defects was alleviated when a wild-type copy of the tdk locus was introduced into the tdk-1 mutant isolates in trans, demonstrating the importance of tdk for successful host interactions.

Our findings raise the intriguing question of why, under certain conditions, endogenous dTMP synthesis is not sufficient to compensate for the lack of a salvaging mechanism. Our working hypothesis is that key metabolic intermediates are limiting during host interactions and that any process (such as dTMP salvage) that reduces the demand on such intermediates confers a competitive advantage to X. nematophila. Particularly relevant to this discussion is the intermediate compound tetrahydrofolate, which, in E. coli, is essential for the synthesis of several cellular metabolites including dTMP (18). X. nematophila pabA mutants are defective in tetrahydrofolate production and have a 90% reduction in nematode colonization levels compared to the wild-type strain. These findings suggest that the tetrahydrofolate-dependent endogenous synthesis of one or more metabolites is necessary for nematode colonization and therefore that intermediates of these metabolic pathways are not available to the bacterium in the nematode host environment (17a). In the absence of thymine salvage, endogenous dTMP synthesis may draw tetrahydrofolate pools away from these pathways, causing a host interaction defect. This hypothesis is consistent with early findings in which E. coli thyA mutants were selected in the presence of salvageable thymine. The frequency of such mutations increased when cells were grown in the absence of metabolites whose synthesis requires tetrahydrofolate (32). Thus, when cellular tetrahydrofolate pools are limiting, the ability to access exogenous sources of tetrahydrofolate-dependent products can confer a selective advantage to cells. If X. nematophila experiences a similar limitation of tetrahydrofolate pools in its host environments, this could account for the competitive advantage of cells able to synthesize dTMP by the salvaging pathway.

Alternatively or additionally, the competitive defect of the tdk-1 mutant isolates could be explained if dT were a signal molecule in the host environments. In E. coli, dT transport has been linked to Tdk activity (6), suggesting that tdk mutants fail to transport dT from the environment and thus would not be able to respond appropriately to its presence. If dT serves as a signaling cofactor, its absence in the cell could effect pleiotropic gene regulation changes, thus diminishing the ability of X. nematophila to interact appropriately with its hosts.

Observable host interaction defects of the tdk-1 mutant were condition dependent. In contrast to the results for competitive nematode colonization on LA plates, the X. nematophila tdk-1 mutant did not demonstrate a competitive defect for the colonization of nematodes developing in G. mellonella, suggesting that in this insect environment, dT and/or dU salvage is not a benefit to the wild-type bacterium. This conclusion was supported by the finding that the tdk mutant isolates did not exhibit a growth defect in hemolymph extracted from M. sexta insects (data not shown). The X. nematophila tdk mutant isolates with a wild-type copy of the tdk locus in Tn7 at the att site had a competitive advantage for nematode colonization in G. mellonella. This strain has the same number of copies of the wild-type tdk locus as the strain with which it was in competition (wild-type X. nematophila harboring an empty Tn7 at the att locus). Thus, the competitive advantage is likely due to variations in levels of tdk expression from the two loci; indeed, such differential transcription has previously been noted in X. nematophila for genes at the att site (5). However, the advantage of having altered levels of tdk expression is not immediately apparent in light of the finding that lack of a functional tdk locus did not confer a disadvantage to X. nematophila for nematode colonization in the G. mellonella insect environment.

Furthermore, while our data clearly demonstrate that the tdk locus is required for normal pathogenicity toward M. sexta insects, this phenomenon is not common to all insect hosts: a tdk missense point mutant (HGB977; tdk-2 R183C FUdRr) and a nonsense point mutant (HGB978; tdk-3 L20Z FUdRr) described elsewhere (26) were attenuated for virulence in insects from the source used in this study (NCSU Entomology Insectary) (E. E. Herbert and H. Goodrich-Blair, unpublished data) but not in M. sexta insects from a different supplier (W. Goodman, University of Wisconsin—Madison) (26). We hypothesize that the lack of tdk renders X. nematophila less efficient at killing insects but that this defect is apparent only under stringent conditions. Indeed, UW M. sexta insects were generally more susceptible to death by injection of X. nematophila bacteria than NCSU insects (S. S. Orchard, unpublished data). Possibly, insects bred by the NCSU Insectary have increased antibacterial activity or have altered levels of nutrients available to microbial invaders, allowing more subtle differences in virulence between bacterial strains to be detected.

To our knowledge, this study presents the first demonstration of the requirement for a nucleoside-salvaging enzyme in bacterium-host interactions, though previous studies have suggested the importance of nucleoside salvaging to intracellular microbes during host interactions (4, 7, 15, 22, 23, 29). Our data further suggest that, unless Tdk has an as-yet-unidentified alternative substrate, dT or dU is present in both the nematode and insect environments. This conclusion, coupled with the fact that salvaging mechanisms appear to be upregulated by pathogens in host environments (15, 29), supports the idea that nucleoside availability may be a widespread feature of host environments exploited by bacteria.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Eugenio Vivas for constructing the pR6Kan plasmid.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health RO1 grant GM59776, National Science Foundation grant IBN-0416783, USDA/CREES grant CRHF-0-6055 (awarded to H.G.B. and used to support S.S.O. in part), and the Investigators in Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Foundation. S.S.O. received additional support through the National Institutes of Health Predoctoral Training Grant T32 GM07215 in Molecular Biosciences and through the National Science Foundation Graduate Teaching Fellows in K-12 Education award DUE-9979628 to the K-Through-Infinity program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. A., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1998. Current protocols in molecular biology. Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bao, Y., D. P. Lies, H. Fu, and G. P. Roberts. 1991. An improved Tn7-based system for the single-copy insertion of cloned genes into chromosomes of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 109:167-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan, K., T. Knaak, L. Satkamp, O. Humbert, S. Falkow, and L. Ramakrishnan. 2002. Complex pattern of Mycobacterium marinum gene expression during long-term granulomatous infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3920-3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowles, K. N., and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2005. Expression and activity of a Xenorhabdus nematophila haemolysin required for full virulence towards Manduca sexta insects. Cell. Microbiol. 7:209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dube, D. K., M. S. Z. Horwitz, and L. A. Loeb. 1991. The association of thymidine kinase activity and thymidine transport in Escherichia coli. Gene 99:25-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fields, P. I., R. V. Swanson, C. G. Haidaris, and F. Heffron. 1986. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:5189-5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forst, S., and D. Clarke. 2002. Bacteria-nematode symbioses, p. 57-77. In R. Gaugler (ed.), Entomopathogenic nematology. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 9.Forst, S. A., and N. Tabatabai. 1997. Role of the histidine kinase, EnvZ, in the production of outer membrane proteins in the symbiotic-pathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:962-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Givaudan, A., and A. Lanois. 2000. flhDC, the flagellar master operon of Xenorhabdus nematophilus: requirement for motility, lipolysis, extracellular hemolysis, and full virulence. J. Bacteriol. 182:107-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser, L., and S. Kornfeld. 1961. The enzymatic synthesis of thymidine-linked sugars. II. Thymidine diphosphate l-rhamnose. J. Biol. Chem. 236:1795-1799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haugo, A. J., and P. I. Watnick. 2002. Vibrio cholerae CytR is a repressor of biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 45:471-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiraga, S., K. Igarashi, and T. Yura. 1967. A deoxythymidine kinase-deficient mutant of Escherichia coli. I. Isolation and some properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 145:41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin, E. C. C. 1996. Dissimilatory pathways for sugars, polyols, and carboxylates. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 15.Mahan, M. J., J. M. Slauch, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1993. Selection of bacterial virulence genes that are specifically induced in host tissues. Science 259: 686-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martens, E. C., K. Heungens, and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2003. Early colonization events in the mutualistic association between Steinernema carpocapsae nematodes and Xenorhabdus nematophila bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 185: 3147-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martens, E. C., E. I. Vivas, K. Heungens, C. E. Cowles, and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2004. Investigating mutualism between entomopathogenic bacteria and nematodes. Nematol. Monogr. Perspect. 2:447-462. [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Martens, E. C., F. M. Russell, and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2005. Analysis of Xenorhabdus nematophila metabolic mutants yields insights into stages of Steinernema carpocapsae nematode intestinal colonization. Mol. Microbiol. 10.1111/j. 1365-2958.2005.04742.X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Matthews, R. G. 1996. One-carbon metabolism. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 19.McCann, J., E. V. Stabb, D. S. Millikan, and E. G. Ruby. 2003. Population dynamics of Vibrio fischeri during infection of Euprymna scolopes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5928-5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minic, Z., S. Pastra-Landis, F. Gaill, and G. Hervé. 2002. Catabolism of pyrimidine nucleotides in the deep-sea tube worm Riftia pachyptila. J. Biol. Chem. 277:127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minic, Z., V. Simon, B. Penverne, F. Gaill, and G. Hervé. 2001. Contribution of the bacterial endosymbiont to the biosynthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides in the deep-sea tube worm Riftia pachyptila. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23777-23784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhard, J., and P. Nygaard. 1987. Purines and pyrimidines. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, B. Magasanik, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 25.Oka, A., H. Sugisaki, and M. Takanami. 1981. Nucleotide sequence of the kanamycin resistance transposon Tn903. J. Mol. Biol. 147:217-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orchard, S. S. 2005. Oligopeptide and nucleoside salvage by the bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Wisconsin, Madison.

- 27.Orchard, S. S., and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2004. Identification and functional characterization of a Xenorhabdus nematophila oligopeptide permease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5621-5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phalaraksh, C., E. M. Lenz, J. C. Lindon, J. K. Nicholson, R. D. Farrant, S. E. Reynolds, I. D. Wilson, D. Osborn, and J. M. Weeks. 1999. NMR spectroscopic studies on the haemolymph of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta: assignment of 1H and 13C NMR spectra. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 29:795-805. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramakrishnan, L., N. A. Federspiel, and S. Falkow. 2000. Granuloma-specific expression of mycobacterium virulence proteins from the glycine-rich PE-PGRS family. Science 288:1436-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sicard, M., K. Brugirard-Ricaud, S. Pagès, A. Lanois, N. E. Boemare, M. Brehélin, and A. Givaudan. 2004. Stages of infection during the tripartite interaction between Xenorhabdus nematophila, its nematode vector, and insect hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6473-6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stacey, K. A., and E. Simson. 1965. Improved method for isolation of thymine-requiring mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 90:554-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Summers, W. C., and P. Raksin. 1993. A method for selection of mutations at the tdk locus in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:6049-6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vivas, E. I., and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2001. Xenorhabdus nematophilus as a model for host-bacterium interactions: rpoS is necessary for mutualism with nematodes. J. Bacteriol. 183:4687-4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volgyi, A., A. Fodor, A. Szentirmai, and S. Forst. 1998. Phase variation in Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1188-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodring, J. L., and H. K. Kaya. 1988. Steinernematid and heterorhabditid nematodes: a handbook of biology and techniques. Southern cooperative series bulletin 331. Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, Fayetteville.

- 37.Wycuff, D. R., and K. S. Matthews. 2000. Generation of an AraC-araBAD promoter-regulated T7 expression system. Anal. Biochem. 277:67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu, J., and R. E. Hurlbert. 1990. Toxicity of irradiated media for Xenorhabdus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:815-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]