Abstract

Slow, rhythmic oscillations (<5 Hz) in the sleep electroencephalogram may be a sign of synaptic plasticity occurring during sleep. The oscillations, referred to as slow-wave activity (SWA), reflect sleep need and sleep intensity. The amount of SWA is homeostatically regulated. It is enhanced after sleep loss and declines during sleep. Animal studies suggested that sleep need is genetically controlled, yet the physiological mechanisms remain unknown. Here we show in humans that a genetic variant of adenosine deaminase, which is associated with the reduced metabolism of adenosine to inosine, specifically enhances deep sleep and SWA during sleep. In contrast, a distinct polymorphism of the adenosine A2A receptor gene, which was associated with interindividual differences in anxiety symptoms after caffeine intake in healthy volunteers, affects the electroencephalogram during sleep and wakefulness in a non-state-specific manner. Our findings indicate a direct role of adenosine in human sleep homeostasis. Moreover, our data suggest that genetic variability in the adenosinergic system contributes to the interindividual variability in brain electrical activity during sleep and wakefulness.

Keywords: electroencephalography, G protein-coupled receptor, synaptic transmission

The homeostatic regulation of rest and sleep is a common principle in invertebrates, fish, and mammals (1). Sleep homeostasis has been associated with local synaptic plasticity (2). Sleep homeostasis implies that increased sleep need associated with prolonged wakefulness results in compensatory changes in sleep duration and, particularly, in sleep intensity during subsequent sleep. It has long been observed in humans that the duration of deep, non-rapid-eye-movement (non-REM) sleep, i.e., slow-wave sleep, is homeostatically regulated (3, 4). Moreover, electroencephalogram (EEG) slow-wave activity (power within ≈0.5–5 Hz) during sleep and theta/low-alpha activity (≈5–9 Hz) during wakefulness are robust physiological markers of sleep need and sleep intensity (5–7). Although these regulatory characteristics are well established (8), the neurochemical and molecular mechanisms underlying sleep homeostasis are unknown.

The neuromodulator adenosine was proposed to provide a neurochemical substrate contributing to sleep homeostasis. Converging lines of evidence, primarily from electrophysiological, microdialysis, and pharmacological animal studies, accumulated in past decades to support an important role of adenosine, as well as adenosine A1 and A2A receptors, in sleep and sleep regulation (see refs. 9–12 for recent overviews). Moreover, quantitative trait loci analyses in mice revealed that a genomic region containing the genes of two adenosine-metabolizing enzymes, adenosine deaminase (ADA) and S-adenosyl-homocysteine hydrolase, modifies the rate at which sleep need accumulates during wakefulness (13). This mouse quantitative trait locus is homologue to a region on the human chromosome 20 that contains the gene that encodes ADA (14). More than 30 allelic variants of ADA are currently listed in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database (accession no. 608958). Most of these variants represent nonfunctional alleles, which give rise to severe combined immunodeficiency. The most frequent allele that is asymptomatic in heterozygous carriers is caused by a G-to-A transition at nucleotide 22 (coding DNA 22G→A). This transition leads to the substitution of asparagine for aspartic acid at codon 8 (protein Asp8Asn) of the ADA protein (15). The following genotype frequencies are expected to occur in a healthy Caucasian population: G/G, 88–92%; G/A, 8–12%; and A/A, <1% (16, 17). It was shown that individuals with the G/A genotype exhibit 20–30% lower enzymatic activity in erythrocytes and leucocytes than individuals with the G/G genotype (18) and may be at an elevated risk of developing autism (19). We hypothesized that the ADA 22G→A polymorphism affects sleep and EEG markers of sleep homeostasis.

It has long been suggested that certain aspects of sleep and EEG variables reflecting sleep homeostasis indicate heritable traits (see ref. 20 for review). For example, studies of human twins revealed that genetic effects account for a substantial proportion of the variance in subjective estimates of sleep quality and duration (21, 22). Moreover, sleep recordings in monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs disclosed significant genetic influences. It was found that primarily sleep variables, which reflect sleep need, are modulated by genetic components (23). In accordance with a role of ADA in sleep homeostasis, our data show that sleep in subjects with the G/A genotype is characterized by more slow-wave sleep and is more intense than in subjects with the G/G genotype. To examine whether these differences are specific for this polymorphism in the adenosinergic system, we also investigated the effects, shown by sleeping and waking EEG, caused by an adenosine A2A receptor coding DNA 1976T→C polymorphism. This polymorphism was recently associated with individual differences in the acute anxiogenic response to caffeine (24), suggesting that this genetic variability is functionally relevant. Moreover, adenosine A2A receptors are important for mediating central nervous effects of sleep- and wake-promoting substances such as adenosine, prostaglandin D2, GABA, histamine, and caffeine (25–27). Independent of sleep and wakefulness, we observed significant differences in brain oscillatory activity within the theta/low-alpha range in individuals with the T/T and C/C genotypes. This observation indicates that this polymorphism affects EEG-generating mechanisms rather than sleep homeostasis. Taken together, our findings suggest that certain aspects of the high interindividual variability in human sleep and EEG variables reflecting sleep need are associated with polymorphisms in the adenosinergic system.

Materials and Methods

The study protocol and all experimental procedures were approved by the cantonal and local ethics committees for research on human subjects. They were conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Caffeine is a competitive adenosine receptor antagonist (28). Because ADA is important in regulating central nervous adenosine levels (29), we predicted that the 22G→A polymorphism modulates the potency of caffeine and contributes to the high interindividual variability in subjective caffeine sensitivity. To optimize recruitment of subjects with G/A and G/G genotypes, we distributed an Internet questionnaire about subjective caffeine sensitivity and sleep to 20,343 university students. A total of 4,329 individuals (2,308 men and 2,021 women) responded (response rate: 21.3%). About one-third of the respondents rated themselves as being caffeine-sensitive (4.0% very sensitive), one-third as averagely caffeine-sensitive, and one-third as caffeine-insensitive (4.3% very insensitive). The 22G→A genotype was determined with allele-specific PCR typing (30) in 119 individuals who had no complaints about their health or sleep and either very high or very low caffeine sensitivity (87 men and 32 women; mean age: 25.3 ± 3.2 years).

Genomic DNA was extracted from 10-ml blood samples. The genotypes of the ADA 22G→A and A2A receptor (ADORA2A) 1976T→C polymorphisms (reference SNP ID no. rs5751876) were analyzed in 100 ng of DNA with allele-specific PCR (31). HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and allele-specific primers for each gene were used. ADA primers were as follows: forward-G, 5′-ccc aga cgc ccg cct tcg-3′; forward-A, 5′-ccc aga cgc ccg cct tca-3′; reverse, 5′-gaa ctc gcc tgc agg agc c-3′ (annealing temperature, 60°C; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 1× Q-solution). ADORA2A primers were as follows: forward-T, 5′-cgg agg ccc aat ggc tat-3′; forward-C, 5′-cgg agg ccc aat ggc tac-3′; reverse, 5′-gtg act ggt caa gcc aac ca-3′ (annealing temperatures: C allele, 66°C, and T allele, 68°C; 1.5 mM MgCl2).

Among the participants of the genetic study, healthy students with distinct genotypes were recruited for sleep studies (Table 1). Seven individuals with the ADA 22G→A G/A genotype [body mass index (BMI) = 22.8 ± 3.2 kg/m2] were pair-matched prior to the sleep recordings with seven individuals with the G/G genotype (BMI = 24.1 ± 1.2 kg/m2). In a separate study, nine individuals with the A2A receptor 1976T→C C/C genotype (seven men and two women; age = 24.6 ± 2.8 years; BMI = 21.9 ± 2.4 kg/m2) were pair-matched with nine individuals with the T/T genotype (age = 24.6 ± 2.6 years; BMI = 23.2 ± 3.4 kg/m2). During the 2 weeks before the study, the subjects were asked to abstain from all caffeine (coffee, tea, cola drinks, chocolate, and energy drinks), to wear a wrist activity monitor on their nondominant arm, and to keep a sleep–wake diary. Actigraphy-derived nocturnal sleep durations did not differ between the groups. The means (± SEM) were as follows: G/A, 474 ± 17 min; G/G, 457 ± 15 min; C/C, 465 ± 15 min; and T/T, 467 ± 16 min. During the 3 days before the study, the participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol and to maintain a regular sleep–wake cycle with the timing and duration of the sleep episodes matched to the sleep schedule of the laboratory nights. All subjects spent two consecutive nights in the sleep laboratory, where sleep was scheduled from 2300 to 0700 h or from 2400 to 0800 h. The first night was considered an adaptation night, and the data were not analyzed. All waking and sleep EEG recordings were performed as described in previous studies (32). The waking EEG was collected in two sessions, one before and one after the sleep episode. The data of the two waking EEG recordings were averaged.

Table 1. Demographics and all-night sleep variables.

| Variable | G/A | G/G | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 5/2 | 5/2 | — |

| Age | 26.4 ± 2.7 | 26.1 ± 2.9 | 0.45 |

| Sleep episode | 467.7 ± 2.2 | 461.3 ± 6.5 | 0.39 |

| Total sleep time | 453.9 ± 3.5 | 440.0 ± 7.4 | 0.17 |

| Sleep efficiency | 94.6 ± 0.7 | 91.7 ± 1.5 | 0.17 |

| Sleep latency | 12.0 ± 2.2 | 18.6 ± 6.4 | 0.37 |

| REM sleep latency | 72.5 ± 3.0 | 72.5 ± 5.6 | 0.99 |

| WASO | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 10.4 ± 5.4 | 0.18 |

| Stage 1 | 34.2 ± 3.9 | 47.5 ± 5.1 | 0.10 |

| Stage 2 | 238.4 ± 7.8 | 226.0 ± 8.5 | 0.33 |

| Stage 3 | 43.8 ± 2.9 | 36.5 ± 5.1 | 0.30 |

| Stage 4 | 48.7 ± 6.5 | 26.5 ± 8.5 | 0.02 |

| Slow-wave sleep | 92.5 ± 6.2 | 63.0 ± 9.3 | 0.006 |

| REM sleep | 88.7 ± 5.2 | 103.6 ± 5.4 | 0.14 |

| Movement time | 12.1 ± 2.0 | 10.8 ± 1.8 | 0.57 |

WASO, wakefulness after sleep onset. Slow-wave sleep, stages 3 and 4. Values are means ± SEM. P, two-tailed paired t tests.

The statistical analyses were performed with spss 11.5 (SPSS, Chicago) and sas 8.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) software. The significance level of all statistical tests was set at α < 0.05. To approximate a normal distribution, the EEG data were log-transformed before statistical tests.

Results

The distribution of the ADA genotypes was the same in the caffeine-sensitive and caffeine-insensitive groups. The prevalence of the G/A genotype was 11.3% (6/53) in the caffeine-sensitive group, 11.8% (6/51) in the caffeine-insensitive group, and 10.9% (13/119) in the entire group. No individual with an A/A genotype was identified. On the basis of the detailed subjective caffeine effects questionnaire, 15 individuals of the entire group could not be unambiguously classified as either caffeine-sensitive or caffeine-insensitive.

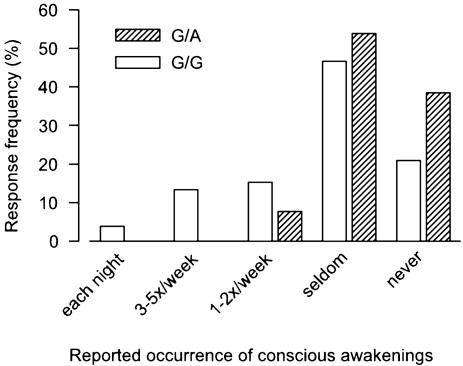

We then examined whether the 22G→A polymorphism affects sleep quality. In humans, as well as in animals, sleep is repeatedly interrupted by brief awakenings. Animal studies confirmed a high correlation between sleep continuity and EEG delta activity (33). Consistent with our hypothesis that reduced ADA enzymatic activity improves sleep, individuals with the G/A genotype (n = 13) reported fewer awakenings at night than individuals with the G/G genotype (n = 106) (Fig. 1). With one exception, all subjects with the G/A genotype stated that they either seldom or never consciously awaken during sleep. The frequency of perceived awakenings was more widely distributed in subjects with the G/G genotype.

Fig. 1.

Lower frequency of nocturnal awakenings in individuals with the ADA 22G→ AG/A genotype (n = 13) than in individuals with the G/G genotype (n = 106). The genotype was determined in 119 healthy subjects among 4,329 respondents to an Internet questionnaire about subjective caffeine sensitivity and sleep quality. The awakening frequency distributions differ significantly between the genotypes (χ2 = 4.1, df = 1, P = 0.04, Kruskall–Wallis test).

To verify that the 22G→A polymorphism also modulates objective measures of sleep, all-night polysomnograms were recorded in age- and sex-matched volunteers with the G/A (n = 7) and G/G (n = 7) genotypes. Sleep efficiency was equally high in both groups of good sleepers (Table 1). Nevertheless, individuals with the G/A genotype showed almost double the amount of deep, stage-4 sleep and roughly 30 min more slow-wave sleep within the 8-h sleep period when compared with the G/G genotype. The difference in the duration of slow-wave sleep represents about half of the difference between baseline and recovery nights after one night without sleep (32).

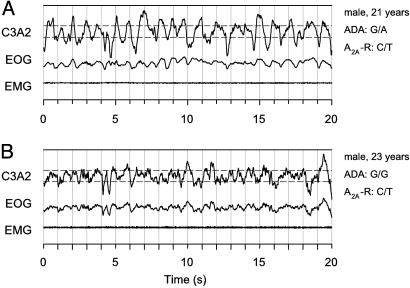

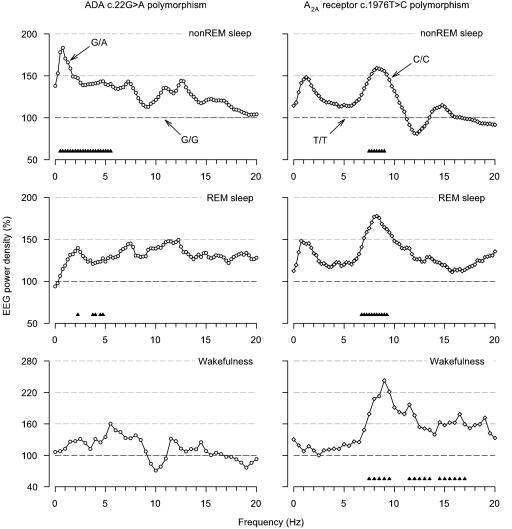

Typical brain electrical oscillations in slow-wave sleep are illustrated in representative 20-s epochs of stage 4 in two young men with distinct ADA genotypes (Fig. 2). It is clearly evident that the amplitude and prevalence of slow waves are higher in the man with the G/A genotype than in the man with the G/G genotype. This observation suggested that the ADA 22G→A polymorphism modulates not only the duration of slow-wave sleep but also the intensity of sleep. To examine this hypothesis, the EEG spectral power in sleep and wakefulness in subjects with the G/A genotype was expressed as a percentage of the corresponding values in subjects with the G/G genotype (Fig. 3 Left). Consistent with deeper sleep, power in non-REM sleep was higher in individuals with the G/A genotype in all frequency bins encompassing the delta and low-theta bands (0.5–5.75 Hz). The difference was particularly large for power <2 Hz. Also, in slow-wave sleep (0.5–1.75 and 3.0–5.25 Hz; data not shown in Fig. 3) and REM sleep (2.25–2.5, 3.75–4.25, and 4.5–5.0 Hz), EEG activity was higher in many bins within the slow-wave range. The difference in averaged absolute 0.5- to 5.0-Hz activity was highly significant in non-REM sleep (118.3 ± 12.9 vs. 74.3 ± 10.9 μV2/Hz, P < 0.001) and slow-wave sleep (247.8 ± 23.3 vs. 182.2 ± 32.0 μV2/Hz, P < 0.006) and tended to be significant in REM sleep (16.1 ± 1.8 vs. 13.5 ± 1.8 μV2/Hz, P < 0.09). No significant differences between the genotypes were found in the waking EEG.

Fig. 2.

Higher amplitude and prevalence of EEG delta oscillations in stage-4 sleep in an individual with the G/A genotype than in an individual with the G/G genotype. The two subjects are concordant with respect to the A2A receptor (A2A-R) 1976T→ C genotype. The representative 20-s sample of slow-wave sleep was recorded in both subjects 61 min after lights-out and within the first non-REM sleep episode. C3A2, EEG derivation; EOG, bipolar electrooculogram; EMG, submental electromyogram. Horizontal dashed lines below and above the EEG trace indicate 75 μV.

Fig. 3.

The ADA 22G→ A and A2A receptor 1976T→ C polymorphisms modulate the EEG in sleep and wakefulness in healthy individuals. Relative EEG power density spectra (C3A2 derivation) in non-REM sleep (stages 2–4), REM sleep, and wakefulness (average of two 5-min waking EEG recordings with eyes open before and after the sleep episode). (Left) For each frequency bin, power in subjects with the G/A genotype (n = 7, open circles) is expressed as a percentage of the corresponding value in individually matched subjects with the G/G genotype. (Right) For each frequency bin, power in subjects with the C/C genotype (n = 9, open diamonds) is expressed as a percentage of the corresponding value in individually matched subjects with the T/T genotype. Geometric mean values are plotted at the lower limit of the bins (0.25-Hz resolution in non-REM and REM sleep, 0.5-Hz resolution in wakefulness). Triangles at the bottom of the panels indicate frequency bins, which differed significantly from G/G and T/T genotypes, respectively (P < 0.05, two-tailed paired t tests).

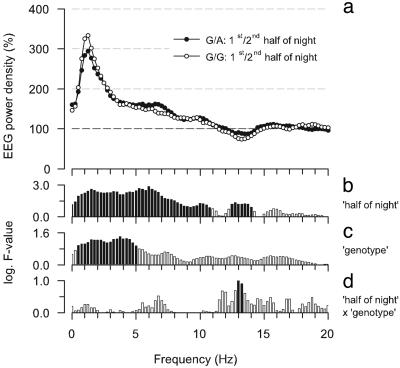

Sleep depth dissipates during the course of a sleep episode (8). Thus, sleep depth is high in the first half of the night and low in the second half of the night. If sleep is deeper in the G/A genotype compared with the G/G genotype, we hypothesized that the differences between the genotypes would resemble the differences between the first and second half of the night. The latter differences are illustrated in Fig. 4a. In accordance with previous studies, power was higher in the low EEG frequencies (0–10.75 Hz). Statistical analyses indicated that the effect of sleep depth (i.e., comparison of first and second “half of night”) on the EEG power spectrum in non-REM sleep is particularly strong in the delta/theta range (Fig. 4b; highest F-values in analysis of variance for repeated measures between ≈0.5–7 Hz). A very similar evolution of F-values as a function of frequency was also present for the factor “genotype” (Fig. 4c; comparison of G/A and G/G genotypes). This finding supports the conclusion that sleep depth is higher in the G/A genotype than in the G/G genotype. The statistics in the delta/theta range revealed no significant interaction between half of night and genotype (Fig. 4d). This result corroborates the findings of mouse studies that the rate at which sleep depth decreases during sleep does not vary with genotypes (13).

Fig. 4.

Effect of elevated sleep depth on EEG power density in non-REM sleep in individuals with the ADA 22G→ AG/A(n = 7) and G/G(n = 7) genotypes. (a) For each frequency bin, power in the first half of the night is expressed as a percentage of power in the second half (100%). Geometric mean values are plotted at the lower limit of the frequency bins (0.25-Hz resolution). (b–d) Bars represent logarithm F-values of a two-way variance analysis for repeated measures with the factors half of night (1st vs. 2nd, df = 1,6) and genotype (G/A vs. G/G, df = 1,6) and their interaction (df = 1,6). Significant F-values are black (P < 0.05), and insignificant F-values are white (P > 0.05).

To examine whether the differences between the G/A and G/G genotypes are specific for this polymorphism and related to sleep regulation, we investigated the sleep and waking EEG in healthy, age- and sex-matched volunteers with distinct genotypes of a 1976T→C polymorphism in the 3′ untranslated region of the adenosine A2A receptor gene. This polymorphism is linked to a 2592C→Tins polymorphism, which may change A2A receptor expression and was recently associated with individual differences in the acute anxiogenic response to caffeine (24). Sleep continuity and global sleep architecture did not differ between C/C(n = 9) and T/T(n = 9) genotypes (data not shown). Fig. 3 Right illustrates the EEG power spectra in the C/C genotype relative to the T/T genotype. However, statistical analyses revealed prominent differences distinct from those observed with the ADA 22G→A polymorphism, and the differences were not state-specific. Compared with individuals with the T/T genotype, power in the high-theta/low-alpha range was invariably enhanced in individuals with the C/C genotype in non-REM sleep (7.5–9.25 Hz), REM sleep (6.75–9.5 Hz), and wakefulness (7.5–10 Hz). Power in the waking EEG was also higher in some additional frequency bins between 11.5 and 17.5 Hz.

Discussion

This study shows that a functional polymorphism of the ADA gene is associated with interindividual variability in sleep architecture and the sleep EEG. Slow-wave sleep is longer and sleep is more intense in subjects with the G/A genotype than in subjects with the G/G genotype. Studies in rats have already suggested a role for ADA in sleep regulation. Thus, ADA was found to be expressed in sleep regulatory areas and to exhibit region-specific diurnal variation in enzymatic activity (34, 35). Moreover, microdialysis perfusion of the ADA inhibitor, coformycin, into the subarachnoid space of the rostral-basal forebrain increased the concentration of extracellular adenosine and the duration of slow-wave sleep (36). Interestingly, ADA is not only a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of adenosine to inosine, but it is also present on the surface of cell membranes (EctoADA) where it binds to the T cell activation marker, CD26, and adenosine A1 receptors (37, 38). Binding of EctoADA to A1 receptors appears to be important for efficient A1 receptor-mediated adenosinergic neurotransmission (37). It is possible, therefore, that local signal transduction via A1 receptors amplifies the putative difference in extracellular adenosine levels in individuals with the G/A and G/G genotypes. Both EctoADA and local changes in slow-wave activity during sleep were proposed to play a role in cellular processes related to neuronal plasticity (39, 40). It might, thus, be more than a coincidence that the differences between the G/A and G/G genotypes in the EEG power spectrum in non-REM sleep are remarkably similar to the sleep EEG changes observed after subjects learned a motor task and showed improvement in performance after sleep (2).

In accordance with a role of ADA in sleep homeostasis, individuals with the G/A genotype reported fewer awakenings at night, spent a longer time in slow-wave sleep, and showed higher delta power during sleep than individuals with the G/G genotype. Remarkably similar changes in sleep architecture and cerebral low-frequency activity are consistently found after the physiological increase of sleep depth after total and partial sleep deprivation (5, 41, 42). Moreover, the EEG differences between the genotypes in non-REM sleep mimicked the differences between states of high and low sleep intensity within a normal baseline night. These findings support a quantitative trait loci analysis in mice that suggested that the genomic region containing the gene encoding ADA modifies sleep need accumulated during wakefulness (13). Our results suggest that sleep is more intense in the G/A genotype than in the G/G genotype. Whether the ADA 22G→A polymorphism plays a role in the prevalence of insomnia needs to be determined in future studies.

Those frequencies in the EEG power spectrum in sleep and wakefulness, which show large interindividual variability and high intraindividual stability, include the theta and alpha bands (7, 43, 44). Waking EEG activity in this frequency range was even suggested to be among the most heritable traits in humans (45). We observed that power in the ≈7.5–10 Hz range is higher in subjects with the 1976C/C genotype of the A2A receptor gene than in subjects with the T/T genotype. This difference, however, was not restricted to the waking EEG, but also prominent in non-REM and REM sleep. The lack of state-specific differences indicates that this A2A receptor genotype plays a role in EEG generating mechanisms rather than in sleep-wake regulation. The 1976T→C polymorphism was recently associated with symptoms of anxiety after acute caffeine intake in healthy volunteers (24) and the susceptibility to panic disorder (46, 47). Nevertheless, the functional relevance of this polymorphism for A2A receptor function and protein expression is presently unclear. To elucidate whether the genetic variability alters A2A receptor signaling with sleep regulation repercussions, the effects of caffeine on EEG markers of sleep homeostasis (32) should be studied in individuals with C/C and T/T genotypes.

The adenosine receptor antagonist, caffeine, is the most popular psychostimulant substance in the world. In doses that are typically consumed in regular coffee preparations and with a common lifestyle, caffeine fights fatigue, prolongs the time to fall asleep, decreases the duration of slow-wave sleep, and attenuates the EEG correlates of sleep homeostasis (32, 48, 49). These effects of caffeine supported a role for adenosine and adenosine receptors in sleep regulation. The present study provides direct evidence in humans that the adenosinergic system indeed modulates sleep and EEG correlates of sleep homeostasis. This study shows that a frequent polymorphism in the gene encoding ADA contributes to the high interindividual variability in sleep intensity. Thus, the adenosinergic system may be an important target for the pharmacological improvement of disturbances of sleep and alertness, which are highly prevalent in the general population (50).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. J. M. Gottselig and D. Schmid for their help with the Internet questionnaire and blood drawings and Drs. A. A. Borbély, C. Kopp, and M. Tafti for helpful comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Grants 3100-067060.01 and 3100A0-107874 (to H.-P.L.).

Author contributions: H.-P.L. designed research; J.V.R., M.A., E.H., R.K., U.F.O.L., and H.-P.L. performed research; H.H.J. and W.B. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.V.R., M.A., E.H., and H.-P.L. analyzed data; and J.V.R., M.A., R.K., U.F.O.L., H.H.J., W.B., and H.-P.L. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: REM, rapid eye movement; EEG, electroencephalogram; ADA, adenosine deaminase; BMI, body mass index.

References

- 1.Tobler, I. (2005) in Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, eds. Kryger, M. H., Roth, T. & Dement, W. C. (Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia), pp. 77–90.

- 2.Huber, R., Ghilardi, M. F., Massimini, M. & Tononi, G. (2004) Nature 430, 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnew, H. W., Jr., Webb, W. B. & Williams, R. L. (1964) Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 17, 68–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webb, W. B. & Agnew, H. W., Jr. (1971) Science 174, 1354–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borbély, A. A., Baumann, F., Brandeis, D., Strauch, I. & Lehmann, D. (1981) Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 51, 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akerstedt, T. & Gillberg, M. (1986) Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 64, 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finelli, L. A., Baumann, H., Borbély, A. A. & Achermann, P. (2000) Neuroscience 101, 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borbély, A. A. & Achermann, P. (2005) in Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, eds. Kryger, M. H., Roth, T. & Dement, W. C. (Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia), pp. 405–417.

- 9.Radulovacki, M. (2005) Neurol. Res. 27, 137–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porkka-Heiskanen, T., Alanko, L., Kalinchuk, A. & Stenberg, D. (2002) Sleep Med. Rev. 6, 321–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basheer, R., Strecker, R. E., Thakkar, M. M. & McCarley, R. W. (2004) Prog. Neurobiol. 73, 379–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayaishi, O., Urade, Y., Eguchi, N. & Huang, Z.-L. (2004) Arch. Ital. Biol. 142, 533–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franken, P., Chollet, D. & Tafti, M. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 2610–2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohandas, T., Sparkes, R. S., Suh, E. J. & Hershfield, M. S. (1984) Hum. Genet. 66, 292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirschhorn, R., Yang, D. R. & Israni, A. (1994) Ann. Hum. Genet. 58, 1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer, N., Hopkinson, D. A. & Harris, H. (1968) Ann. Hum. Genet. 32, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persico, A. M., Militerni, R., Bravaccio, C., Schneider, C., Melmed, R., Trillo, S., Montecchi, F., Palermo, M. T., Pascucci, T., Puglisi-Allegra, S., et al. (2000) Am. J. Med. Genet. 96, 784–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Battistuzzi, G., Iudicone, P., Santolamazza, P. & Petrucci, R. (1981) Ann. Hum. Genet. 45, 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bottini, N., De Luca, D., Saccucci, P., Fiumara, A., Elia, M., Porfirio, M. C., Lucarelli, P. & Curatolo, P. (2001) Neurogenetics 3, 111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franken, P. & Tafti, M. (2003) Front. Biosci. 8, E381–E397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Partinen, M., Kaprio, J., Koskenvuo, M., Putkonen, P. & Langinvainio, H. (1983) Sleep 6, 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heath, A. C., Kendler, K. S., Eaves, L. J. & Martin, N. G. (1990) Sleep 13, 318–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linkowski, P. (1999) J. Sleep Res. 8, Suppl. 1, 11–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alsene, K., Deckert, J., Sand, P. & de Wit, H. (2003) Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 1694–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satoh, S., Matsumura, H., Suzuki, F. & Hayaishi, O. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 5980–5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong, Z. Y., Huang, Z. L., Qu, W. M., Eguchi, N., Urade, Y. & Hayaishi, O. (2005) J. Neurochem. 92, 1542–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, Z. L., Qu, W. M., Eguchi, N., Chen, J. F., Schwarzschild, M. A., Fredholm, B. B., Urade, Y. & Hayaishi, O. (2005) Nat. Neurosci. 8, 858–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fredholm, B. B., Bättig, K., Holmen, J., Nehlig, A. & Zvartau, E. E. (1999) Pharmacol. Rev. 51, 83–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagy, J. I., Geiger, J. D. & Staines, W. A. (1990) Neurochem. Int. 16, 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erlich, H. A., Gelfand, D. H. & Saiki, R. K. (1988) Nature 331, 461–462. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newton, C. R., Graham, A., Heptinstall, L. E., Powell, S. J., Summers, C., Kalsheker, N., Smith, J. C. & Markham, A. F. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 2503–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landolt, H. P., Rétey, J. V., Tönz, K., Gottselig, J. M., Khatami, R., Buckelmüller, I. & Achermann, P. (2004) Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1933–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franken, P., Dijk, D. J., Tobler, I. & Borbély, A. A. (1991) Am. J. Physiol. 261, R198–R208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackiewicz, M., Nikonova, E. V., Bell, C. C., Galante, R. J., Zhang, L., Geiger, J. D. & Pack, A. I. (2000) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 80, 252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mackiewicz, M., Nikonova, E. V., Zimmerman, J. E., Galante, R. J., Zhang, L., Cater, J. R., Geiger, J. D. & Pack, A. I. (2003) J. Neurochem. 85, 348–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okada, T., Mochizuki, T., Huang, Z. L., Eguchi, N., Sugita, Y., Urade, Y. & Hayaishi, O. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 312, 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciruela, F., Saura, C., Canela, E. I., Mallol, J., Lluis, C. & Franco, R. (1996) FEBS Lett. 380, 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torvinen, M., Gines, S., Hillion, J., Latini, S., Canals, M., Ciruela, F., Bordoni, F., Staines, W., Pedata, F., Agnati, L. F., et al. (2002) Neuroscience 113, 709–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franco, R., Casado, V., Ciruela, F., Saura, C., Mallol, J., Canela, E. I. & Lluis, C. (1997) Prog. Neurobiol. 52, 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. (2003) Brain Res. Bull. 62, 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knoblauch, V., Kräuchi, K., Renz, C., Wirz-Justice, A. & Cajochen, C. (2002) Cereb. Cortex 12, 1092–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunner, D. P., Dijk, D. J. & Borbély, A. A. (1993) Sleep 16, 100–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aeschbach, D., Postolache, T. T., Sher, L., Matthews, J. R., Jackson, M. A. & Wehr, T. A. (2001) Neuroscience 102, 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Gennaro, L., Ferrara, M., Vecchio, F., Curcio, G. & Bertini, M. (2005) NeuroImage 26, 114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Beijsterveldt, C. E., Molenaar, P. C., de Geus, E. J. & Boomsma, D. I. (1996) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 58, 562–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deckert, J., Nothen, M. M., Franke, P., Delmo, C., Fritze, J., Knapp, M., Maier, W., Beckmann, H. & Propping, P. (1998) Mol. Psychiatry 3, 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton, S. P., Slager, S. L., De Leon, A. B., Heiman, G. A., Klein, D. F., Hodge, S. E., Weissman, M. M., Fyer, A. J. & Knowles, J. A. (2004) Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landolt, H. P., Dijk, D. J., Gaus, S. E. & Borbély, A. A. (1995) Neuropsychopharmacology 12, 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landolt, H. P., Werth, E., Borbély, A. A. & Dijk, D. J. (1995) Brain Res. 675, 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foster, R. G. & Wulff, K. (2005) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]